1. Introduction

The skin is the body’s largest organ and serves as a physical, chemical, and immunological barrier between the internal and external environments. Its principal functions include protection against exogenous insults and regulation of insensible water loss [

1]. Structurally, the skin comprises the epidermis, the dermis—the thickest connective tissue layer—and the hypodermis. Collagen is the principal structural protein of the dermis, accounting for roughly 70–80% of the skin’s dry weight; within dermal collagen, type I predominates (~80–85%) and type III contributes ~8–11% [

2]. Collagen fibers form a scaffold that anchors elastic fibers (elastin and fibrillin; ~1–2% of dry weight) and glycosaminoglycans (GAGs; ~0.1–0.3%) [

3], together constituting the dermal extracellular matrix (ECM). The ECM supports resident cells, mainly fibroblasts, which are intimately associated with collagen fibers and synthesize most ECM components, as well as epidermal keratinocytes, which adhere to a specialized ECM (basement membrane) rich in type IV collagen. Beyond passive support, collagen dynamically modulates fibroblast and keratinocyte behavior, influencing proliferation, migration, and tissue repair, with downstream effects on skin, hair, and nails [

4].

Skin aging reflects the combined impact of intrinsic (chronological) factors and extrinsic exposures (ultraviolet radiation, pollution, smoking, nutrition, and lifestyle) [

5]. With age, dermal collagen synthesis declines and matrix architecture deteriorates, contributing to hallmark clinical changes, such as reduced hydration, impaired barrier function, loss of firmness, and wrinkle formation [

6]. Because collagen is both a structural determinant and a regulator of cutaneous cell physiology, strategies that support collagen homeostasis are of interest for slowing the visible manifestations of aging.

Hydrolyzed collagen (collagen peptides, CPs) is produced from collagen-rich animal tissues (e.g., bovine, porcine, avian, and marine by-products) by denaturation and enzymatic hydrolysis of native collagen, yielding low–molecular-weight peptides (typically ~3–6 kDa). Human studies indicate that CPs are digestible and bioavailable; in addition to free amino acids, oligopeptides have been detected in plasma following ingestion [

7]. CP supplementation is generally well tolerated in clinical settings [

8]. Over the past two decades, randomized and observational studies, including systematic reviews and meta-analyses, have reported benefits of CPs on aging-related skin outcomes, such as wrinkle appearance, elasticity, hydration, and dermal collagen content/density [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

In vitro work provides plausible mechanisms, showing that CPs can modulate fibroblast and keratinocyte activity, promoting anabolic ECM processes and attenuating photoaging-related pathways (e.g., oxidative stress) [

4,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18].

Based on this evidence, we evaluated two commercially relevant collagen peptide products, avveraTM and a comparative product named the active control, using a translational approach. First, we quantified pro-collagen I secretion by normal human dermal fibroblasts exposed to two concentrations of the corresponding to each product. We then conducted an 8-week clinical study to assess whether daily oral supplementation with avveraTM or the active control improves stratum corneum hydration (Corneometer), transepidermal water loss (TEWL) (Tewameter), and wrinkle metrics (area and length) derived from standardized 3D imaging. This design allows us to relate mechanistic, cell-based effects to clinical endpoints that are meaningful for skin appearance and barrier function.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Collagen Peptides

Both the investigational product, avvera™ (Italgel S.p.a.), and the active control product, Verisol® (Gelita AG), consist of collagen peptides (CPs) from bovine type I collagen with a mean molecular weight of approximately 2.0 kDa. CPs or collagen hydrolysates are classified by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as generally recognized as safe (GRAS) [

19] and no intolerances, incompatibilities or adverse effects have been reported.

2.2. Cell Culture and Cell Viability Assessment

Primary normal human dermal fibroblasts (NHDF) (obtained from PromoCell) were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, 1 g/L glucose; Gibco) supplemented with L-glutamine (Gibco) and penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco), in a humidified incubator at 37 °C, 5% CO₂. Cells were passaged with trypsin–EDTA (Gibco) and routine rinses used phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Gibco). Cell number and membrane integrity were assessed by trypan-blue exclusion (Bio-Rad) using a Bürker chamber under light microscopy. For the MTT assay, fibroblasts were seeded at 10,000 cells/well in 96-well plates and allowed to adhere overnight in the above growth medium. After 24 h, medium was replaced with fresh medium containing the product preparations at 0.1% or 0.01% (w/v) and cells were incubated for 72 h. Supernatants were removed, MTT solution was added to each well, and plates were incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. The MTT reagent was aspirated, formazan crystals were solubilized with 100% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Aldrich), and absorbance was read at 550 nm on a multi-well spectrophotometer. Viability was calculated from absorbance values and expressed as a percentage of the matched non-treated control.

2.3. ELISA Quantification of Pro-Collagen I Levels

Normal human dermal fibroblasts (NHDF) were counted by trypan-blue exclusion using a Bürker chamber and seeded at 1×10⁵ cells/well in DMEM (1 g/L glucose; Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), L-glutamine, and penicillin–streptomycin. Cells were maintained at 37 °C, 5% CO₂ for 24 h to establish a confluent monolayer. (~80%) Cultures were then switched to fresh medium containing 10% FBS and the test collagen peptide preparations at 0.1% or 0.01% (w/v) and incubated for 72 h. At the end of the exposure, culture supernatants were collected and analyzed for pro-collagen I using a commercially available ELISA (Abcam), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Each concentration was assessed in four replicates. In parallel, MTT described above was performed on matched wells; ELISA readouts were normalized to the corresponding MTT signal to account for differences in viable cell number, and data were expressed relative to the mean value of non-treated controls.

2.4. Hydration Assessment

Skin hydration was quantified with a Corneometer CM 825 (Courage + Khazaka, Cologne, Germany) [

20,

21]. The device is based on a capacitance principle, in which variations in the dielectric constant caused by changes in epidermal water content alter the capacitance of a precision capacitor. Measurements reflect hydration in the upper 10–20 μm of the stratum corneum and were obtained in arbitrary Corneometer units. All measurements were taken on the cheek of each volunteer at every study timepoint.

2.5. Transepidermal Water Loss (TEWL) Assessment

TEWL was assessed using a Tewameter TM 300 [

22,

23].The system is based on an open chamber method in which two pairs of temperature and humidity sensors measure the density gradient of water evaporation. Results were obtained as g/h/m². All measurements were taken on the cheek of each volunteer at every study timepoint.

2.6. Crows-Feet Wrinkles Assessment

Facial wrinkles, with emphasis on crow’s feet, were analyzed using the Visia-CRP-5 Primos system (Canfield Scientific, USA) [

24,

25]. Images were captured under standardized conditions (clean skin, closed eyes, neutral expression) with subjects positioned in a stabilization rig. Three photographs were taken per subject (left 45°, frontal, right 45°). 3D reconstructions were analyzed using Matrox Imaging Library software to quantify wrinkle parameters. All measurements were taken on the cheek of each volunteer at every study timepoint.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

For hydration and TEWL five replicate measurements per subject per timepoint were obtained, screened for outliers (ROUT method, Q=5%), and averaged. Wrinkle analysis yielded a single value per ROI. Day 28 and day 56 measurements were normalized to baseline values (day 0) and reported as percent change relative to day 0. Normality was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Parametric variables were analyzed by RM one-way ANOVA with Geisser–Greenhouse correction and post hoc Sidak’s test. Non-parametric variables were analyzed by the Friedman test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons. Between-group comparisons were performed using unpaired t-tests (parametric) or Mann–Whitney U tests (non-parametric). Data are presented as percentage change from baseline (D0), normalized to initial values, with error bars representing the standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. In Vitro Quantification of Pro-Collagen I in Human Dermal Fibroblasts

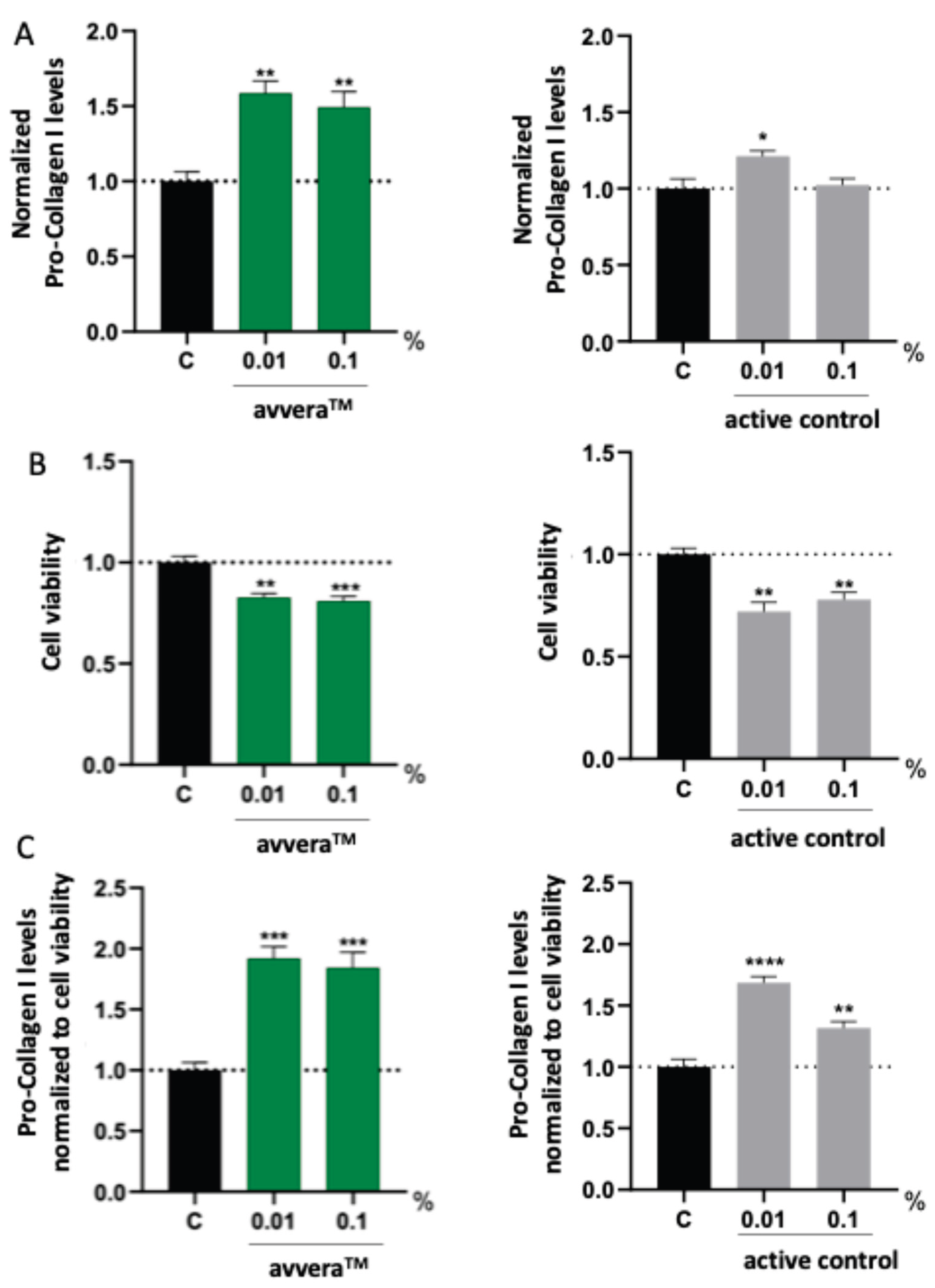

Normal human dermal fibroblasts (NHDF) were incubated for 72 hours with two collagen peptide preparations corresponding to avveraTM and to the active control. To account for potential cytotoxicity and differences in viable cell number, secreted pro-collagen I levels measured in cell culture supernatants were normalized to paired MTT viability assay results. This normalization ensured that the reported pro-collagen I values reflected per-cell secretory activity rather than changes due to reduced viability.

Both collagen preparations were evaluated at 0.1% and 0.01% (w/v).

Figure 1 shows three readouts: (i) secreted pro-collagen I normalized to the non-treated control (

Figure 1A), (ii) MTT-derived cell viability (

Figure 1B), and (iii) pro-collagen I values normalized to cell viability (

Figure 1C). The avvera

TM preparation increased normalized pro-collagen I levels by 92% when used at 0.01%, and by 84.3% when supplemented at 0.1% (

Figure 1C). When used at 0.01%, the active control increased normalized pro-collagen I secretion by 68.4% relative to non-treated control, while a concentration of 0.1% elicited a more modest but still significant increase of 31.6% (

Figure 1C). Taken together, under identical assay conditions avvera™ elicited larger increases in MTT-normalized pro-collagen I production than the active control at both concentrations, indicating a stronger pro-collagen-stimulating effect in human fibroblasts.

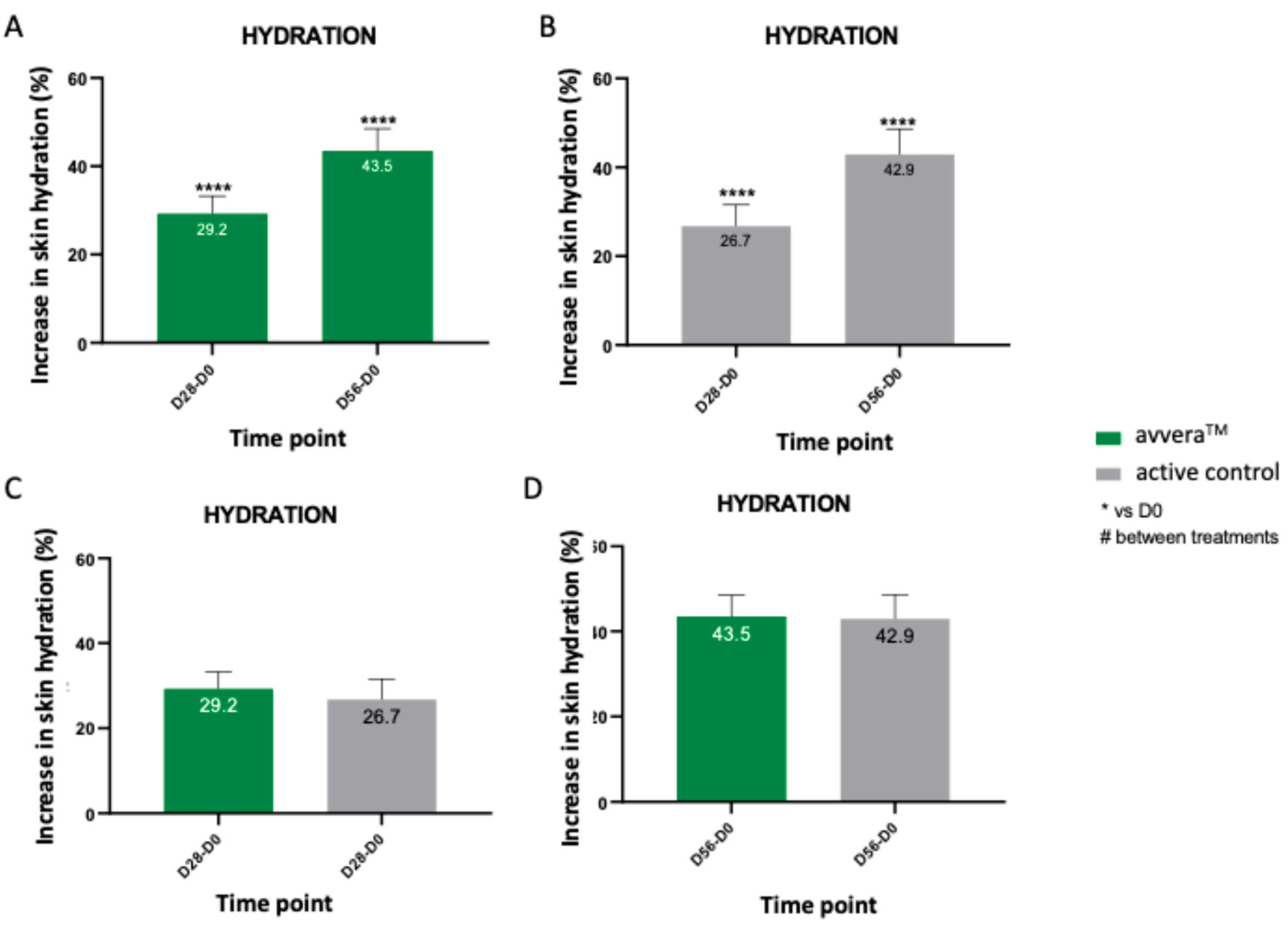

3.2. Evaluation of the Skin Hydration In Vivo

To complement the

in vitro findings on fibroblast stimulation, a clinical evaluation was conducted to investigate the efficacy of daily oral intake of collagen peptides on the skin parameters of volunteers. A total of 67 healthy female volunteers aged 35-65 years were enrolled and completed the 56-day study. Participants were assigned with either avvera

TM or the active control, and facial skin hydration was assessed at baseline, day 28 and day 56 using a Corneometer CM825. Both products produced a significant and progressive increase in hydration relative to baseline. After 28 days of supplementation, hydration levels increased by 29.2% in the avvera

TM group and 26.7% in the active control group (

Figure 2A and 2B), demonstrating that improvements were already evident within the first month of intake. By day 56, the increases on skin hydration reached 43.5% for avvera

TM and 42.9% for the active control (

Figure 2A, 2B). Our results also showed that in the best 90% of volunteers, avvera

TM significantly increased skin hydration by 32.2% and 46.9% after 28 and 56 days of treatment, respectively, compared with basal values (data not shown). However, no significant differences were detected when compared the increases on skin hydration of avvera

TM vs the active control (

Figure 2C, 2D). Overall, while between-group differences were not statistically significant, avvera™ showed numerically greater hydration increase at both time points, indicating a favorable trend for avvera™ over the active control under the study conditions.

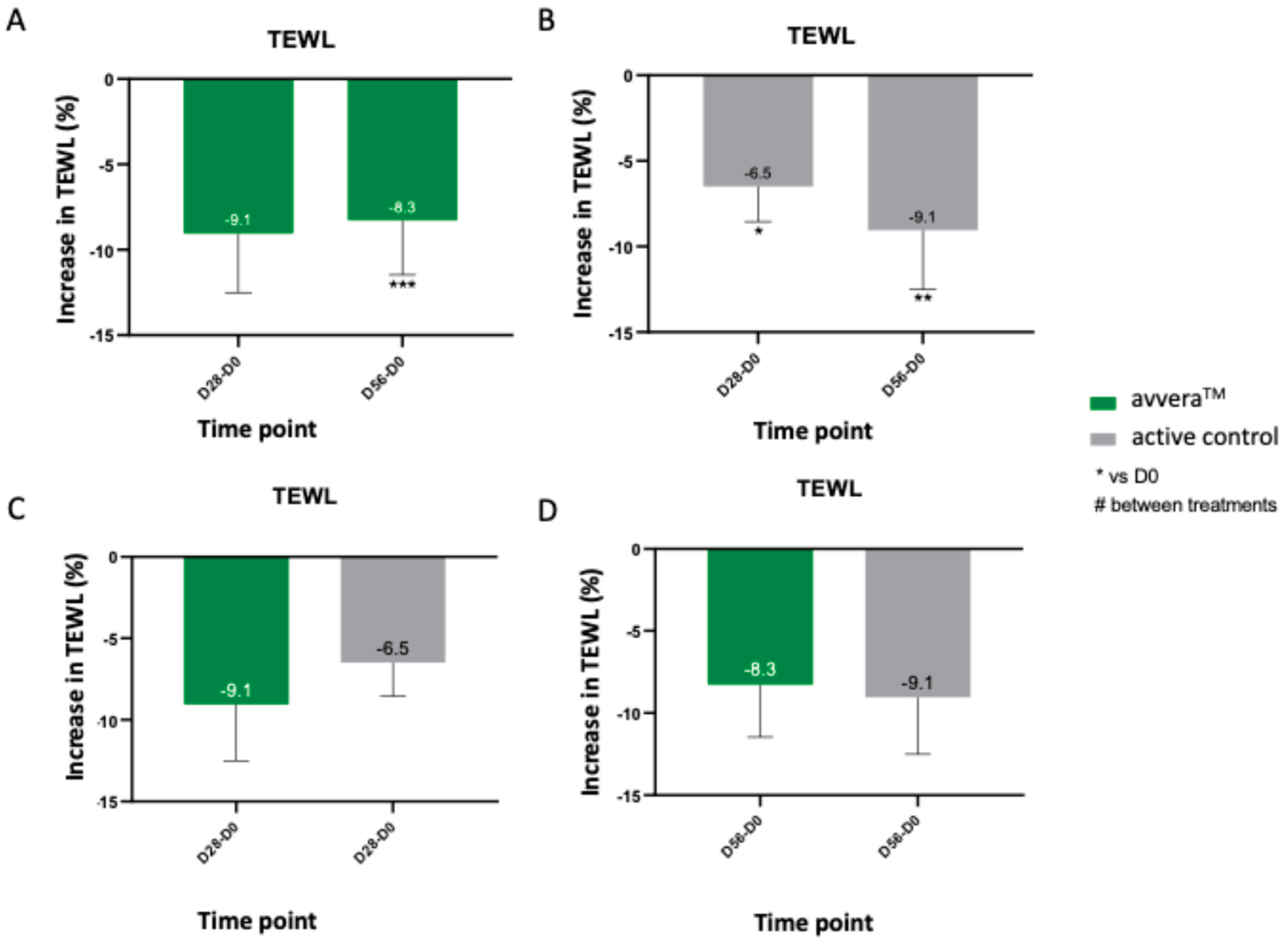

3.3. Evaluation of the Trans-Epidermal Water Loss (TEWL)

We then evaluated the epidermal barrier function at baseline, day 28, and day 56 by Tewameter (TEWL) measurements on the skin. Lower TEWL values indicate reduced water diffusion through the stratum corneum and, therefore, improved barrier integrity. avvera

TM showed a significant TEWL reduction at day 56 (8.3%)

, although changes at day 28 were not statistically significant (

Figure 3A). On the other side, the active control showed a progressive reduction of 6.5% at day 28 and 9.1% at day 56, reaching similar TEWL levels than avvera

TM after 8 weeks (

Figure 3B). In the best 90% of volunteers, avvera

TM significantly decreased TEWL by 12.3% after 56 days of treatment, compared with basal values (data not shown). Direct comparisons at matched time points revealed no significant between-group differences, indicating that the two collagen peptide preparations achieved similar improvements in epidermal water-retention capacity over 56 days of daily intake (

Figure 3C, 3D).

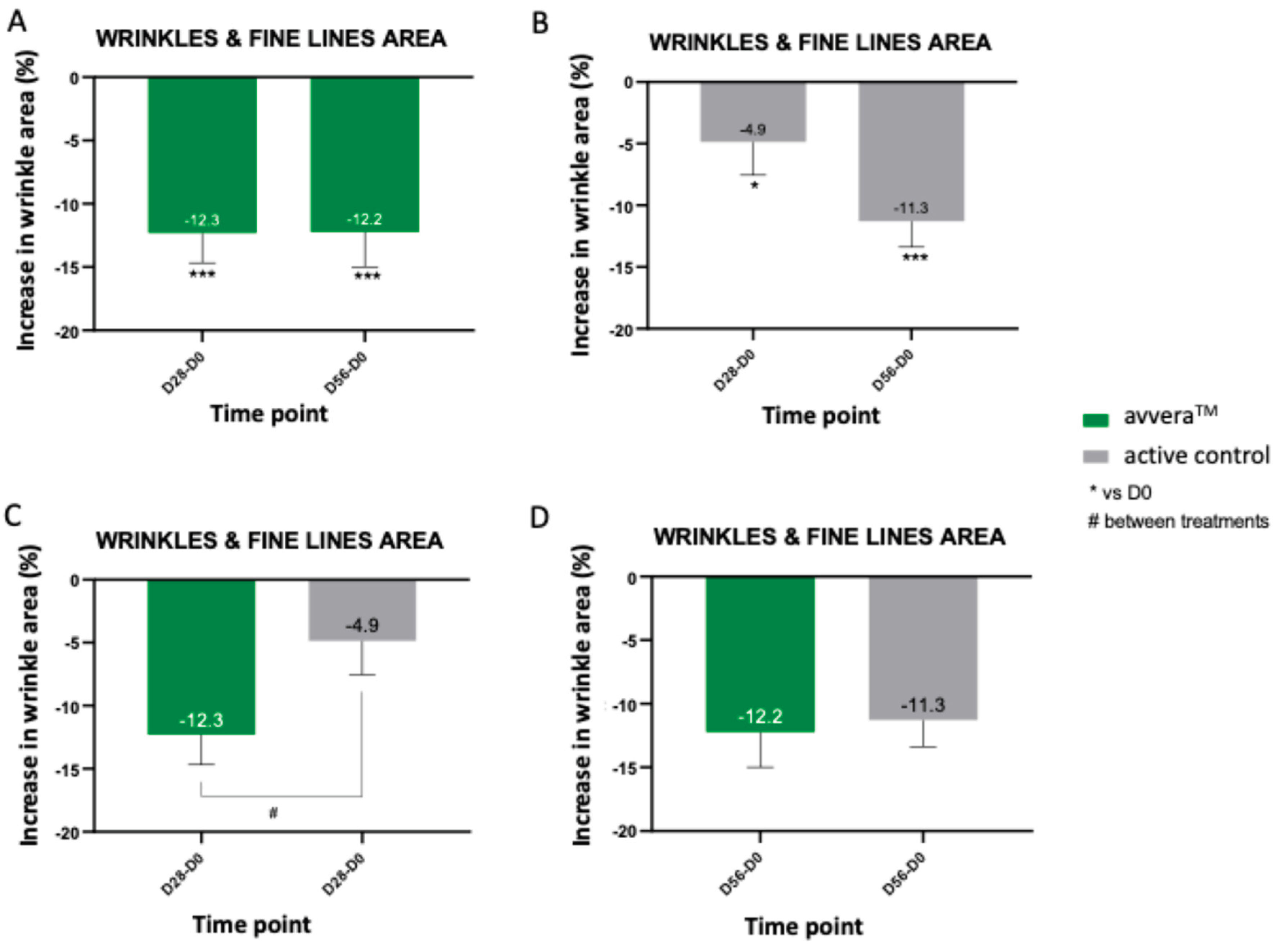

3.4. Evaluation of the Cross-Feet Wrinkles In Vivo

Crow’s-feet area was quantified from standardized 3D facial images at baseline, day 28 and day 56. Results showed that avvera

TM exhibited a strong early response, with a reduction of 12.3% already at day 28, which was maintained at day 56 (by 12.2%) (

Figure 4A). With the active control, the wrinkle area showed a modest but significant reduction at day 28 (by 4.9%) that became more pronounced by day 56 (by 11.3%), indicating a larger effect after eight weeks than after four (

Figure 4B). In the best 90% of volunteers, avvera

TM significantly decreased crow’s feet wrinkles and fine lines area by 14.5% and 14.3% after 28 and 56 days of treatment, respectively, compared with basal values (data not shown). Between-group analysis at day 28 favored avvera

TM (difference 7.5%), whereas at day 56 the treatments did not differ significantly because the active control group reached a comparable magnitude of reduction (

Figure 4C, 4D). Overall, avvera™ induced a larger, earlier reduction in crow’s-feet area, significantly greater at Day 28 (by 7.5%), indicating a clear advantage in onset of action versus the active control.

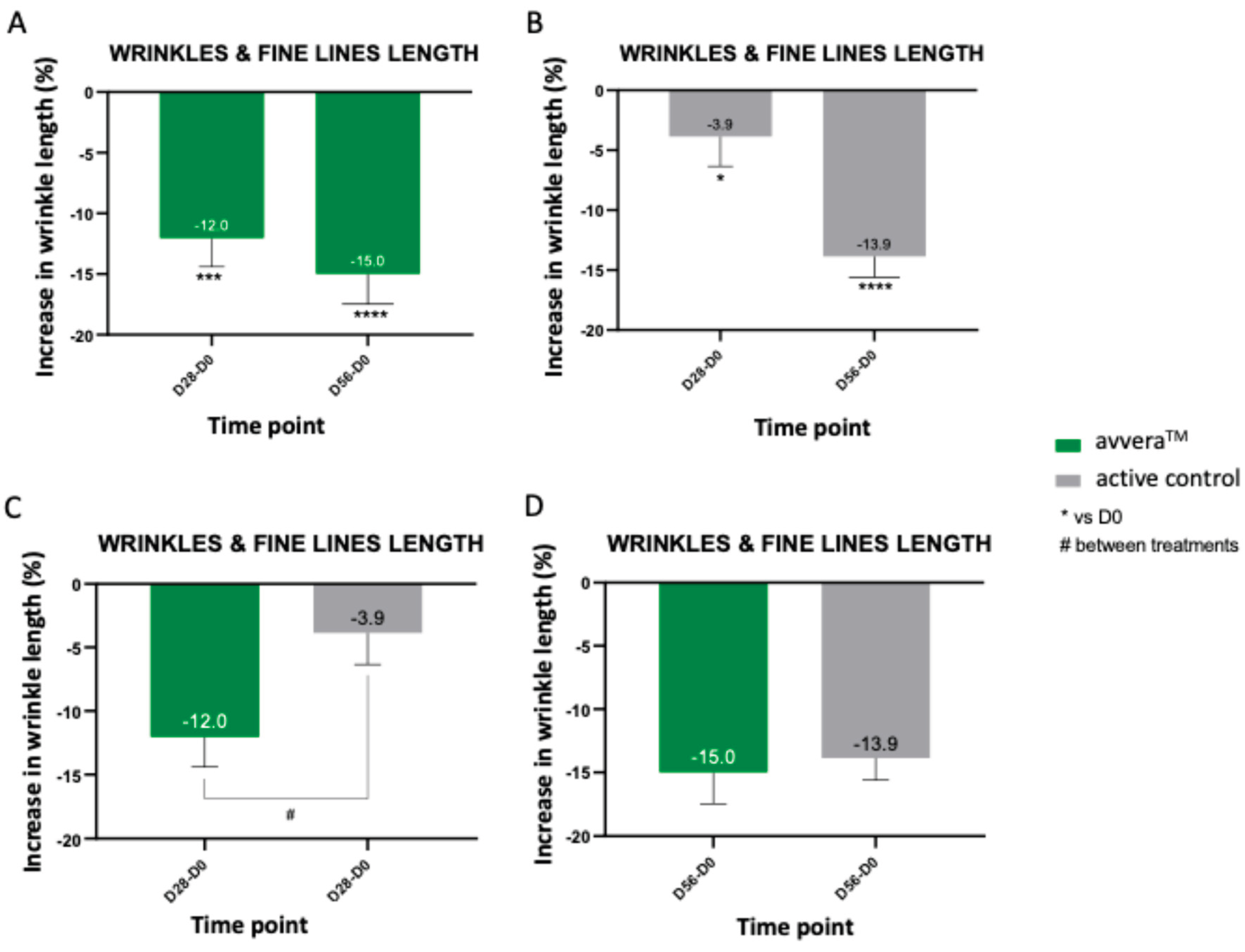

We then quantified wrinkle length from standardized 3D facial images. Treatment with avvera

TM decreased the wrinkle length at day 28 (by 12.0%) and at day 56 (by 15%) (

Figure 5A). In the active control treatment, length decrease was 3.9% (at day 28) and 13.9% (at day 56) (

Figure 5B). In the best 90% of volunteers, avvera

TM significantly decreased crow’s feet wrinkles and fine lines length by 14.2% and 17.1% after 28 and 56 days of treatment, respectively, compared with basal values (data not shown). We observed a significative difference in crow’s feet wrinkles and fine lines length by 8.2% favoring avvera

TM after 28 days of treatment, when comparing between groups (

Figure 5C, 5D). Taken together, avvera™ achieved greater reductions in wrinkle length than the active control, with a significant advantage at day 28, indicating a faster and stronger effect under the study conditions.

4. Discussion

Skin water balance is essential for its barrier function, regeneration process and healthy appearance [

26]. It depends primarily on stratum corneum (SC), the uppermost layer of the skin (outermost 10-20 microns of the epidermis). Skin ability to maintain its water balance is assessed by two parameters: skin hydration and transepidermal water loss (TEWL). The first refers to SC water content and the second refers to the SC ability to retain its water content. In healthy skin, skin hydration and TEWL are well-coordinated, but reduced skin hydration and elevated TEWL result in dry, flaky skin as seen in atopic dermatitis and keratinization disorders [

27].

Due to its importance, moisturizing of the skin is the first anti-aging skin care. Currently, it is considered a good option to combine traditional topical moisturizers with dietary supplements or functional foods [

28]. In fact, many foods such as fruits and vegetables can contribute to replenish skin water (hydration effect), but they cannot restore the SC water retention capacity (moisturization effect), which requires nutrients with specific bioactivity [

29].

CPs have been found to be one of the most effective functional supplements to enhance the moisturizing capacity of the skin by increasing skin hydration and reducing TEWL [

28,

29,

30], even in skin damaged by UVB exposure, improving skin barrier function in all cases [

31].

In this study we combined

in vitro assays in human dermal fibroblasts with an 8-week clinical study to assess the effect of avvera

TM in different skin parameters.

In vitro, the peptide preparations corresponding to avvera

TM and the active control increased normalized pro-collagen I secretion when used at 0.01% and 0.1% (w/v), indicating per-viable-cell stimulation of collagen biosynthesis when ELISA values were adjusted to MTT viability. The

in vitro data showing robust, normalized pro-collagen I responses with both products provide biological evidence for these clinical changes; small differences in peptide profiles (e.g., chain-length distributions and motif frequencies) could influence kinetics of extracellular matrix turnover and thus the speed of visible wrinkle responses [

32,

33,

34]. While our study was not designed to identify mechanistic drivers, this temporal pattern is consistent with the fact that specific peptide fingerprints can differentially modulate early fibroblast activity. Under identical assay conditions, avvera™ produced greater MTT-normalized increases in pro-collagen I than the active control at both 0.01% and 0.1%, indicating a stronger pro-collagen-stimulating effect in human dermal fibroblasts.

Clinically, both products improved skin hydration and reduced the trans-epidermal water loss after 56 days. Although between-group differences were not statistically significant, avvera™ exhibited numerically larger hydration increases at both time points, suggesting a favorable trend versus the active control under the study conditions. On the other hand, our results also showed that each product reduced crow’s-feet wrinkle area and length during the study period. In this regard, avvera™ induced a larger, earlier reduction in crow’s-feet area than the active control, with a statistically significant advantage at day 28 (difference of 7.5%). Importantly, this earlier-onset benefit was also observed for wrinkle length, where avvera™ outperformed the active control at day 28 (difference of 8.2%), evidencing a faster effect.

The results obtained with the avvera™ treatment align with the broader literature on oral collagen peptides (CPs). Recent meta-analyses of randomized trials report significant, albeit modest, benefits of CPs on hydration, elasticity and wrinkles compared with placebo, supporting the relevance of the endpoints assessed here [

35,

36,

37]. Mechanistically, absorbed collagen-derived di-/tripeptides (e.g., Pro-Hyp) have been detected in human blood after ingestion and can stimulate fibroblast proliferation and hyaluronic-acid synthesis

in vitro, pathways consistent with improved hydration and skin quality [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. Moreover, some clinical studies specifically document reduced trans-epidermal water loss following CP supplementation, consonant with the barrier improvements observed in our trial [

43,

44,

45]. In this context, avvera™ demonstrated a dual effect on cutaneous water balance, increasing skin hydration while reducing trans-epidermal water loss, a pattern consistent with enhanced epidermal water retention (“water capture”) and improved barrier function.

The main limitations of the present study were a short (8-week) endpoint measurement and a modest sample size. Further randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies with longer time-points and a higher number of subjects will shed more light.

In summary, avvera™ demonstrated a dual action on skin water homeostasis over 8 weeks, increasing hydration while lowering transepidermal water loss, with numerically greater increases than the active control; together, these trends suggest a potential advantage for avvera™ in water-retention under the study conditions. Beyond hydration and barrier outcomes, avvera™ delivered earlier visible wrinkle improvements, producing significantly greater reductions at day 28 in crow’s-feet area (by 7.5%) and length (by 8.2%) versus the active control. Collectively, the measured improvements in hydration, TEWL, and early wrinkle metrics position avvera™ as a promising and clinically effective oral collagen peptide formulation, delivering earlier-onset benefits than the active control under the conditions tested.

5. Conclusions

This translational study shows that oral collagen peptides improved key skin parameters over 8 weeks, with avvera™ consistently performing at least comparably to the active control and demonstrating a dual action on water homeostasis; higher hydration with lower transepidermal water loss. avvera™ also delivered earlier visible wrinkle benefits, producing significantly greater reductions in crow’s-feet area and length at Day 28, while in vitro it elicited stronger increases in MTT-normalized pro-collagen I secretion in human dermal fibroblasts compared to the active control. Taken together, these findings indicate that avvera™ is a promising and clinically effective collagen peptide formulation, with a faster onset of improvement in wrinkle metrics and a favorable profile for skin hydration and barrier support.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization; E.B., J.M.M. Methodology; E.B., J.M.M. Validation; E.B., J.M.M. Formal Analysis; E.B., J.M.M. Investigation; E.B., J.M.M. Resources; E.B.P., E.B., J.M.M. Data Curation; J.M.M., E.B. Writing—Original Draft Preparation; J.M.M. Writing—Review and Editing; E.B.P., J.M.M. Supervision; E.B., J.M.M. Project Administration; E.B., J.M.M. Funding acquisition; E.B.P.

Funding

The authors declare that this study was funded by Italgel, S.p.a. private funds, who kindly provided the products used in the study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of HOSPITAL UNIVERSITARIO Y POLITÉCNICO LA FE (protocol code 2025-0034-1; date of approval 26/02/2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions (e.g., privacy, legal or ethical reasons).

Acknowledgments

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

E.B. and J.M.M. were employed by Bionos Biotech SL. E.B.P. was employed by Protein, S.A., a subsidiary of Italgel, S.p.a. The authors declare that this study received funding from Italgel, S.p.a. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- E. Proksch, J. M. Brandner, and J. Jensen, “The skin: an indispensable barrier,” Exp. Dermatol., vol. 17, no. 12, pp. 1063–1072, Dec. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Oikarinen, “Aging of the skin connective tissue: how to measure the biochemical and mechanical properties of aging dermis,” Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed., vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 47–52, Apr. 1994.

- E. F. Bernstein and J. Uitto, “The effect of photodamage on dermal extracellular matrix,” Clin. Dermatol., vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 143–151, Mar. 1996. [CrossRef]

- M. A. R. Brandao-Rangel et al., “Hydrolyzed Collagen Induces an Anti-Inflammatory Response That Induces Proliferation of Skin Fibroblast and Keratinocytes,” Nutrients, vol. 14, no. 23, p. 4975, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Calleja-Agius, M. Brincat, and M. Borg, “Skin connective tissue and ageing,” Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol., vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 727–740, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- D. M. Reilly and J. Lozano, “Skin collagen through the lifestages: importance for skin health and beauty,” Plast. Aesthetic Res., vol. 8, p. 2, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Virgilio et al., “Absorption of bioactive peptides following collagen hydrolysate intake: a randomized, double-blind crossover study in healthy individuals,” Front. Nutr., vol. 11, p. 1416643, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. D. Choi, C. T. Sung, M. L. W. Juhasz, and N. A. Mesinkovsk, “Oral Collagen Supplementation: A Systematic Review of Dermatological Applications,” J. Drugs Dermatol. JDD, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 9–16, Jan. 2019.

- S. Sibilla, M. Godfrey, S. Brewer, A. Budh-Raja, and L. Genovese, “An Overview of the Beneficial Effects of Hydrolysed Collagen as a Nutraceutical on Skin Properties: Scientific Background and Clinical Studies,” Open Nutraceuticals J., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 29–42, Mar. 2015. [CrossRef]

- R. B. De Miranda, P. Weimer, and R. C. Rossi, “Effects of hydrolyzed collagen supplementation on skin aging: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” Int. J. Dermatol., vol. 60, no. 12, pp. 1449–1461, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. A. R. Dewi et al., “Exploring the Impact of Hydrolyzed Collagen Oral Supplementation on Skin Rejuvenation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Cureus, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S.-Y. Pu et al., “Effects of Oral Collagen for Skin Anti-Aging: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 9, p. 2080, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. Zague, V. De Freitas, M. D. C. Rosa, G. Á. De Castro, R. G. Jaeger, and G. M. Machado-Santelli, “Collagen Hydrolysate Intake Increases Skin Collagen Expression and Suppresses Matrix Metalloproteinase 2 Activity,” J. Med. Food, vol. 14, no. 6, pp. 618–624, June 2011. [CrossRef]

- N. Matsuda et al., “Effects of Ingestion of Collagen Peptide on Collagen Fibrils and Glycosaminoglycans in the Dermis,” J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. (Tokyo), vol. 52, no. 3, pp. 211–215, 2006. [CrossRef]

- H. Ohara et al., “Collagen-derived dipeptide, proline-hydroxyproline, stimulates cell proliferation and hyaluronic acid synthesis in cultured human dermal fibroblasts,” J. Dermatol., vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 330–338, Apr. 2010. [CrossRef]

- P. Le Vu et al., “Effects of Food-Derived Collagen Peptides on the Expression of Keratin and Keratin-Associated Protein Genes in the Mouse Skin,” Skin Pharmacol. Physiol., vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 227–235, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Fu, H. Dai, Q. Wang, R. Gao, and Y. Zhang, “Recent progress in preventive effect of collagen peptides on photoaging skin and action mechanism,” Food Sci. Hum. Wellness, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 218–229, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Choi, H. Joo, M. Kim, D.-U. Kim, H.-C. Chung, and J. G. Kim, “Low-Molecular-Weight Collagen Peptide Improves Skin Dehydration and Barrier Dysfunction in Human Dermal Fibrosis Cells and UVB-Exposed SKH-1 Hairless Mice,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 26, no. 13, p. 6427, July 2025. [CrossRef]

- Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, Bethesda, MD. Life Sciences Research Office.; Food and Drug Administration, Washington, D.C. Bureau of Foods., Evaluation of the Health Aspects of Gelatin as a Food Ingredient. 1975. [Online]. Available: https://ntrl.ntis.gov/NTRL/dashboard/searchResults/titleDetail/PB254527.xhtml.

- E. Berardesca and European Group for Efficacy Measurements on Cosmetics and Other Topical Products (EEMCO), “EEMCO guidance for the assessment of stratum corneum hydration: electrical methods,” Skin Res. Technol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Bioeng. Skin ISBS Int. Soc. Digit. Imaging Skin ISDIS Int. Soc. Skin Imaging ISSI, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 126–132, May 1997. [CrossRef]

- K.-I. O’goshi and J. Serup, “Inter-instrumental variation of skin capacitance measured with the Corneometer,” Skin Res. Technol. Off. J. Int. Soc. Bioeng. Skin ISBS Int. Soc. Digit. Imaging Skin ISDIS Int. Soc. Skin Imaging ISSI, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 107–109, May 2005. [CrossRef]

- V. Rogiers, “EEMCO Guidance for the Assessment of Transepidermal Water Loss in Cosmetic Sciences,” Skin Pharmacol. Physiol., vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 117–128, 2001. [CrossRef]

- M. O. de Melo and P. M. B. G. Maia Campos, “Application of biophysical and skin imaging techniques to evaluate the film-forming effect of cosmetic formulations,” Int. J. Cosmet. Sci., vol. 41, no. 6, pp. 579–584, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Q. Nguyen, A. S. Zahr, T. Kononov, and G. Ablon, “A Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Clinical Study Investigating the Efficacy and Tolerability of a Peptide Serum Targeting Expression Lines,” J. Clin. Aesthetic Dermatol., vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 14–21, May 2021.

- L. Goberdhan, K. Schneider, E. T. Makino, and R. C. Mehta, “Combining Diamond-Tip Dermabrasion Treatments and Topical Skincare in Participants with Dry, Hyperpigmented, Photodamaged or Acne-Prone/Oily Facial Skin: A Clinical Usage Study,” Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol., vol. Volume 16, pp. 2645–2657, Sept. 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Bonté, “Skin moisturization mechanisms: New data,” Ann. Pharm. Fr., vol. 69, no. 3, pp. 135–141, May 2011. [CrossRef]

- K. Maeda, “Skin-Moisturizing Effect of Collagen Peptides Taking Orally,” J. Nutr. Food Sci., vol. 08, no. 02, 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. M. B. G. Maia Campos, M. O. Melo, and F. C. Siqueira César, “Topical application and oral supplementation of peptides in the improvement of skin viscoelasticity and density,” J. Cosmet. Dermatol., vol. 18, no. 6, pp. 1693–1699, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Q. Sun, J. Wu, G. Qian, and H. Cheng, “Effectiveness of Dietary Supplement for Skin Moisturizing in Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials,” Front. Nutr., vol. 9, p. 895192, June 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Inoue, F. Sugihara, and X. Wang, “Ingestion of bioactive collagen hydrolysates enhance facial skin moisture and elasticity and reduce facial ageing signs in a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled clinical study: Collagen enhances skin properties,” J. Sci. Food Agric., vol. 96, no. 12, pp. 4077–4081, Sept. 2016. [CrossRef]

- E. Choi, H. Joo, M. Kim, D.-U. Kim, H.-C. Chung, and J. G. Kim, “Low-Molecular-Weight Collagen Peptide Improves Skin Dehydration and Barrier Dysfunction in Human Dermal Fibrosis Cells and UVB-Exposed SKH-1 Hairless Mice,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 26, no. 13, p. 6427, July 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Dierckx, M. Patrizi, M. Merino, S. González, J. L. Mullor, and R. Nergiz-Unal, “Collagen peptides affect collagen synthesis and the expression of collagen, elastin, and versican genes in cultured human dermal fibroblasts,” Front. Med., vol. 11, p. 1397517, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Edgar, B. Hopley, L. Genovese, S. Sibilla, D. Laight, and J. Shute, “Effects of collagen-derived bioactive peptides and natural antioxidant compounds on proliferation and matrix protein synthesis by cultured normal human dermal fibroblasts,” Sci. Rep., vol. 8, no. 1, p. 10474, July 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Blanco, N. Sanz, A. C. Sánzhez, B. Correa, R. I. Pérez-Martín, and C. G. Sotelo, “Molecular Weight Analysis of Blue Shark (Prionace glauca) Collagen Hydrolysates by GPC-LS; Effect of High Molecular Weight Hydrolysates on Fibroblast Cultures: mRNA Collagen Type I Expression and Synthesis,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 23, no. 1, p. 32, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S.-Y. Pu et al., “Effects of Oral Collagen for Skin Anti-Aging: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Nutrients, vol. 15, no. 9, p. 2080, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. B. de Miranda, P. Weimer, and R. C. Rossi, “Effects of hydrolyzed collagen supplementation on skin aging: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” Int. J. Dermatol., vol. 60, no. 12, pp. 1449–1461, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. D. Choi, C. T. Sung, M. L. W. Juhasz, and N. A. Mesinkovsk, “Oral Collagen Supplementation: A Systematic Review of Dermatological Applications,” J. Drugs Dermatol. JDD, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 9–16, Jan. 2019.

- K. Iwai et al., “Identification of food-derived collagen peptides in human blood after oral ingestion of gelatin hydrolysates,” J. Agric. Food Chem., vol. 53, no. 16, pp. 6531–6536, Aug. 2005. [CrossRef]

- Y. Shigemura, D. Kubomura, Y. Sato, and K. Sato, “Dose-dependent changes in the levels of free and peptide forms of hydroxyproline in human plasma after collagen hydrolysate ingestion,” Food Chem., vol. 159, pp. 328–332, Sept. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Y. Taga et al., “Identification of a highly stable bioactive 3-hydroxyproline-containing tripeptide in human blood after collagen hydrolysate ingestion,” NPJ Sci. Food, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 29, June 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Ohara et al., “Collagen-derived dipeptide, proline-hydroxyproline, stimulates cell proliferation and hyaluronic acid synthesis in cultured human dermal fibroblasts,” J. Dermatol., vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 330–338, Apr. 2010. [CrossRef]

- T. T. Asai, F. Oikawa, K. Yoshikawa, N. Inoue, and K. Sato, “Food-Derived Collagen Peptides, Prolyl-Hydroxyproline (Pro-Hyp), and Hydroxyprolyl-Glycine (Hyp-Gly) Enhance Growth of Primary Cultured Mouse Skin Fibroblast Using Fetal Bovine Serum Free from Hydroxyprolyl Peptide,” Int. J. Mol. Sci., vol. 21, no. 1, p. 229, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Miyanaga, T. Uchiyama, A. Motoyama, N. Ochiai, O. Ueda, and M. Ogo, “Oral Supplementation of Collagen Peptides Improves Skin Hydration by Increasing the Natural Moisturizing Factor Content in the Stratum Corneum: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial,” Skin Pharmacol. Physiol., vol. 34, no. 3, pp. 115–127, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. J. Tak et al., “Effect of Collagen Tripeptide and Adjusting for Climate Change on Skin Hydration in Middle-Aged Women: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial,” Front. Med., vol. 7, p. 608903, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Ito, S. Seki, and F. Ueda, “Effects of Composite Supplement Containing Collagen Peptide and Ornithine on Skin Conditions and Plasma IGF-1 Levels-A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial,” Mar. Drugs, vol. 16, no. 12, p. 482, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).