Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. State of the Art

2.1. Sustainable Building Approach

2.2. Sustainability Assessment Methods

2.3. Circular Economy in Construction Sector

2.4. Environmental Pollution of the Construction Sector and Related Risks

2.5. Off-Site Construction

2.6. Buildings' Response to Climate Change: Resilience and Adaptation

3. Materials and Methods

| Macro systems (ISO 15392) |

Objectives (Agenda 2030) | Milestones | Indicator Categories |

|---|---|---|---|

| ENVIRONMENTAL | Making cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable | Promote off-site construction | Modular design |

| Maintain or restore the functionality of a building after damage | Modular design | ||

| Minimization of waste from demolition operations | Conservative design/Existing recovery | ||

| Decarbonisation of construction processes | NZEB Design | ||

| Creating healthy and comfortable spaces | Multi-scale/integrated design | ||

| Ensuring sustainable consumption and production patterns | Sustainable management and efficient use of natural resources | NZEB Design | |

| Substantially reduce waste generation through prevention, reduction, recycling and reuse | Design using a circular BIM-LCA approach | ||

| Ensure water saving and system efficiency | Design of water recovery and reuse systems | ||

| Use of eco-friendly materials and recycled content | Eco-design (CAM) | ||

| Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts | Reduction of heat islands | Eco-friendly design / SMART plant design | |

| Improving ambient air quality | |||

| Protection from extreme temperatures | |||

| Drought and flood protection | Multi-scale/integrated design | ||

| Protection from sea level rise and storm surge | |||

| Protection from hurricanes and severe storms | Aerodynamic design | ||

| Fire protection | Fire safety design | ||

| Protection from seismic activity | Anti-seismic design | ||

| SOCIAL-POLITICAL | Making cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable | Ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services | Elimination of architectural barriers |

| Strengthen inclusive urbanization and the capacity to plan and manage participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlements | Participatory design | ||

| Guaranteeing a welcome for immigrants and asylum seekers | Inclusive/adaptive design | ||

| Creating safe, shared and inclusive public spaces | Inclusive/adaptive design | ||

| Ensuring sustainable consumption and production patterns | Adaptability and functional flexibility | Modular design | |

| Engage with neighborhood groups and help them develop a sustainable future vision for their community | Participatory design | ||

| Promote sustainable public procurement practices, in accordance with national policies and priorities | Sustainable Tenders (CAM - PAN GPP) | ||

| Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts | Integrate climate change measures into national policies, strategies and planning | Urban and Territorial Planning | |

| Map areas that need improvement, such as areas most exposed to natural disasters | Urban and Territorial Planning | ||

| Increase effective capacity for planning and management of climate change interventions | Urban and Territorial Planning | ||

| ECONOMIC | Making cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable | Reduction of direct economic losses caused by disasters | Modular design |

| Reduction of construction, use and end-of-life costs of buildings | Economic evaluation of interventions using the LCC approach | ||

| Ensuring sustainable consumption and production patterns | Rationalize inefficient fossil fuel subsidies that encourage waste | NZEB Design | |

| Promotion of the circular economy with consequent dematerialization of the economy | Design using a circular BIM-LCA approach | ||

| Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts | Promoting the economy based on renewable energy sources | Multi-scale/integrated design |

3.1. Assigning Weights to Indicators

3.2. Definition of the Questionnaire to Be Administered to the Interested Parties

| Score | Rating |

|---|---|

| 0 | None |

| 1 | Minimum |

| 2 | Good |

| 3 | Excellent |

| Indicator Category | Modular Design | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Indicator | Foundation Structure | |||||

| Impact on life cycle phases (EN 15978:2011) | Impact on the technical specifications of the minimum basic environmental criteria (DM 23/06/2022) | Weight assignment | ||||

| Production phase | Groups of buildings (art. 2.3) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Buildings (art. 2.4) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Building components (art. 2.5) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Construction site (art. 2.6) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Construction phase | Groups of buildings (art. 2.3) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Buildings (art. 2.4) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Building components (art. 2.5) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Construction site (art. 2.6) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Exercise phase | Groups of buildings (art. 2.3) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Buildings (art. 2.4) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Building components (art. 2.5) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Construction site (art. 2.6) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| End of life phase | Groups of buildings (art. 2.3) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Buildings (art. 2.4) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Building components (art. 2.5) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Construction site (art. 2.6) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Benefits beyond the system | Groups of buildings (art. 2.3) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Buildings (art. 2.4) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Building components (art. 2.5) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Construction site (art. 2.6) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

3.3. Data Processing and Determination of Indicator Weights

| Indicator Categories | Strategic approach | Indicators | Weights in relation to the areas of application of CAM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Building Group | Buildings | Building components | Worksite | |||

| 1. Modular design | Passive strategies | Foundation structures | 0.14 | 0.89 | 1.14 | 0.95 |

| Elevation structures | 0.19 | 0.88 | 1.16 | 1.03 | ||

| Vertical closures (opaque and transparent) | 0.19 | 0.85 | 1.13 | 0.94 | ||

| Horizontal closures | 0.18 | 0.84 | 1.08 | 0.91 | ||

| Internal partitions | 0.16 | 0.80 | 1.07 | 0.93 | ||

| Active strategies | Plant components | 0.19 | 0.94 | 1.20 | 0.99 | |

| 2. Conservative design/ Existing recovery | Passive strategies | Disassembly and selective demolition | 0.19 | 0.99 | 1.26 | 1.42 |

| Load-bearing structure (wet system) | 0.11 | 0.79 | 1.02 | 1.06 | ||

| Load-bearing structure (dry system) | 0.11 | 0.89 | 1.16 | 1.22 | ||

| Vertical closures (wet system) | 0.13 | 0.78 | 1.01 | 1.05 | ||

| Vertical closures (dry system) | 0.13 | 0.85 | 1.12 | 1.18 | ||

| Internal partitions (wet system) | 0.10 | 0.68 | 0.89 | 0.92 | ||

| Internal partitions (dry system) | 0.10 | 0.75 | 0.99 | 1.03 | ||

| Insulation of opaque closures | 0.11 | 0.92 | 1.20 | 1.22 | ||

| 3. Design using a circular BIM-LCA approach | Passive strategies | Secondary raw material recovered or recycled | 0.86 | 0.99 | 1.26 | 1.32 |

| Materials derived from renewable raw materials | 0.86 | 1.07 | 1.37 | 1.42 | ||

| Materials with DAP/EPD certification (Environmental Product Declaration) | 0.81 | 1.06 | 1.36 | 1.39 | ||

| Selective demolition and recycling of excavated materials and construction and demolition waste (C&D) | 0.28 | 1.12 | 1.42 | 1.52 | ||

| Predictive and scheduled maintenance plan for the work | 0.14 | 0.97 | 1.21 | 1.18 | ||

| External closures and internal dry partitions | 0.10 | 0.79 | 1.03 | 1.02 | ||

| 4. NZEB Design | Passive strategies | Solar orientation | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.97 | 0.74 |

| Shading with plant or architectural elements | 0.90 | 0.88 | 1.12 | 0.87 | ||

| Eco-friendly materials with low embodied carbon content | 0.86 | 1.02 | 1.27 | 1.16 | ||

| Insulation of opaque and transparent vertical closures | 0.76 | 0.90 | 1.14 | 0.89 | ||

| Sun protection devices | 0.74 | 0.97 | 1.21 | 1.00 | ||

| Natural ventilation systems | 0.76 | 0.97 | 1.21 | 0.91 | ||

| Active strategies | Heating and air conditioning systems | 0.64 | 0.82 | 1.02 | 0.82 | |

| Systems powered by renewable sources for the production of electricity and domestic hot water | 0.73 | 0.98 | 1.23 | 0.93 | ||

| Controlled mechanical ventilation systems | 0.61 | 0.82 | 1.02 | 0.79 | ||

| Flow reduction systems, flow control systems, water temperature control systems | 0.63 | 0.82 | 1.02 | 0.81 | ||

| Low water consumption sanitary appliances | 0.68 | 0.85 | 1.06 | 0.81 | ||

| High efficiency alternative systems (high efficiency co/trigeneration, centralized heat pumps) | 0.73 | 0.95 | 1.18 | 0.92 | ||

| Mixed strategies | Transparent vertical closures integrated with photovoltaic | 0.73 | 0.98 | 1.23 | 0.95 | |

| Integrated panels for external closures (BiPV) | 0.65 | 0.90 | 1.14 | 0.86 | ||

|

5. Eco-friendly design (CAM, SMART plant design) |

Passive strategies | Vehicles of the EEV (Improved Ecological Vehicle) category | 0.88 | 0.58 | 0.74 | 0.83 |

| Visual and noise shielding on construction sites | 0.25 | 0.62 | 0.76 | 1.12 | ||

| Green or cold upper and vertical closures | 0.25 | 0.93 | 1.17 | 0.67 | ||

| Highly reflective opaque external closures (for roofing and casings) | 0.20 | 0.88 | 1.08 | 0.62 | ||

| Low-emissivity transparent external closures | 0.20 | 0.92 | 1.14 | 0.65 | ||

| Ecological thermal and acoustic insulation of opaque vertical closures and internal partitions | 0.16 | 1.04 | 1.29 | 0.71 | ||

| Natural lighting | 0.31 | 0.96 | 1.17 | 0.63 | ||

| Flooring and coverings with low VOC (volatile organic compound) release | 0.20 | 0.95 | 1.18 | 0.67 | ||

| Pollutant protection systems | 0.24 | 1.00 | 1.25 | 0.68 | ||

| Storage system for vital energy self-sufficiency in the event of disasters | 0.25 | 0.87 | 1.06 | 0.58 | ||

| Active strategies | Air quality control systems (during construction, building and occupation phases) | 0.19 | 0.95 | 1.16 | 0.66 | |

| Lighting control and integration systems | 0.16 | 0.87 | 1.06 | 0.59 | ||

| Air flow and CO2 monitoring systems | 0.18 | 0.98 | 1.21 | 0.67 | ||

| Energy consumption monitoring system | 0.16 | 1.01 | 1.25 | 0.68 | ||

| Home automation systems | 0.18 | 0.86 | 1.06 | 0.60 | ||

| 6. Aerodynamic design | Passive strategies | Compact building shape (curved facades) | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.49 | 0.42 |

| Elevation structures | 0.43 | 0.78 | 0.99 | 0.96 | ||

| Coverings | 0.43 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 0.98 | ||

| Opaque vertical closures | 0.46 | 0.79 | 1.00 | 0.95 | ||

| Transparent vertical closures | 0.44 | 0.77 | 0.97 | 0.94 | ||

| 7. Design of water recovery and reuse systems | Passive strategies | Permeable flooring | 1.57 | 0.93 | 0.18 | 0.67 |

| Infiltration grates and channels | 1.40 | 0.84 | 0.19 | 0.58 | ||

| Arrangement of green areas | 1.38 | 0.82 | 0.17 | 0.54 | ||

| Rainwater collection tank | 1.72 | 1.02 | 0.19 | 0.68 | ||

| Wastewater storage tanks | 1.50 | 0.89 | 0.19 | 0.60 | ||

| Accumulation tanks for purified water | 1.67 | 0.99 | 0.20 | 0.68 | ||

| Toilet storage tanks | 1.40 | 0.84 | 0.21 | 0.61 | ||

| Active strategies | Rainwater filtration and purification system | 1.77 | 1.05 | 0.20 | 0.76 | |

| Irrigation systems for green areas | 1.45 | 0.87 | 0.18 | 0.59 | ||

| Wastewater treatment plant | 1.67 | 0.99 | 0.18 | 0.69 | ||

| 8. Fire safety design | Passive strategies | Fireproofing treatment for structural elements | 1.03 | 0.75 | 0.93 | 0.33 |

| Smoke-proof filter compartment | 0.97 | 0.70 | 0.88 | 0.32 | ||

| Insulation of internal closures and partitions | 0.92 | 0.67 | 0.83 | 0.32 | ||

| External vertical connections (fire escapes) | 1.19 | 0.88 | 1.10 | 0.40 | ||

| Compensatory water supply tank | 1.28 | 0.92 | 1.15 | 0.45 | ||

| Storage tank for waste water for auxiliary fire-fighting system supply | 1.24 | 0.91 | 1.14 | 0.45 | ||

| Active strategies | Detection and alarm systems | 0.93 | 0.67 | 0.84 | 0.28 | |

| Oxygen reduction systems | 0.94 | 0.67 | 0.84 | 0.31 | ||

| Fire water system | 1.03 | 0.75 | 0.93 | 0.39 | ||

| Automatic fire extinguishing systems | 0.99 | 0.73 | 0.91 | 0.38 | ||

| Auxiliary fire extinguishing system powered by recycled water | 1.07 | 0.76 | 0.95 | 0.39 | ||

| Smoke and heat evacuators | 1.04 | 0.73 | 0.91 | 0.34 | ||

| 9. Earthquake-proof design | Passive strategies | Foundation structures | 0.13 | 0.72 | 1.07 | 1.02 |

| Elevation structures | 0.13 | 0.73 | 1.08 | 1.02 | ||

| Vertical closures | 0.10 | 0.67 | 0.96 | 0.88 | ||

| Horizontal internal partitions | 0.08 | 0.57 | 0.84 | 0.78 | ||

| Structural reinforcement and consolidation systems | 0.14 | 0.75 | 1.08 | 1.02 | ||

| Seismic isolation systems for structures (insulators, dissipators) | 0.14 | 0.75 | 1.04 | 1.02 | ||

| Structural monitoring systems | 0.13 | 0.78 | 1.08 | 1.02 | ||

| 10. Multi-scale/integrated design | Passive strategies | Recovery of green areas and degraded sites | 1.58 | 0.92 | 0.16 | 1.11 |

| High reflectance covers | 1.35 | 0.79 | 0.17 | 0.88 | ||

| Flooring with high reflective power | 1.22 | 0.71 | 0.15 | 0.80 | ||

| Photocatalytic surfaces | 1.35 | 0.79 | 0.17 | 0.87 | ||

| Flood barriers/anti-flood barriers | 1.58 | 0.92 | 0.16 | 1.09 | ||

| Active strategies | Outdoor lighting systems powered by renewable sources | 1.60 | 0.94 | 0.18 | 1.08 | |

| Rainwater collection, purification and reuse plants | 1.73 | 1.01 | 0.19 | 1.19 | ||

| Irrigation systems powered by renewable sources | 1.76 | 1.03 | 0.18 | 1.21 | ||

| District heating and cooling networks | 1.45 | 0.85 | 0.17 | 0.99 | ||

| 11. Elimination of architectural barriers | Strategies | External and internal routes | 1.33 | 0.78 | 0.12 | 0.36 |

| Parking spaces | 1.38 | 0.81 | 0.11 | 0.36 | ||

| Rest and rest areas along the routes | 1.28 | 0.75 | 0.09 | 0.31 | ||

| Vertical and inclined connections | 1.40 | 0.82 | 0.06 | 0.31 | ||

| Dedicated toilet facilities | 1.44 | 0.85 | 0.11 | 0.39 | ||

| Acoustic warning devices | 1.25 | 0.74 | 0.06 | 0.31 | ||

| Environmental Sensors | 1.37 | 0.81 | 0.10 | 0.35 | ||

| 12. Participatory design | Strategies | Involvement and openness towards the community | 1.27 | 0.73 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| Participatory round tables (public debate) | 1.22 | 0.70 | 0.06 | 0.07 | ||

| Event organization | 1.17 | 0.67 | 0.06 | 0.07 | ||

| 13. Inclusive / adaptive design | Strategies | Modular design for emergency/reception | 1.49 | 0.88 | 1.22 | 1.23 |

| Co-housing | 1.37 | 0.81 | 1.16 | 1.19 | ||

| Designing accessible and shared spaces | 1.42 | 0.84 | 1.21 | 1.25 | ||

| 14. Sustainable Tenders (CAM - PAN GPP) | Strategies | Candidate selection | 0.93 | 0.55 | 0.68 | 0.87 |

| Technical specifications | 1.39 | 0.83 | 1.03 | 1.31 | ||

| Conditions of execution | 1.32 | 0.78 | 0.97 | 1.22 | ||

| OEPV Award (Most Economically Advantageous Offer) | 0.76 | 0.45 | 0.56 | 0.72 | ||

| Technical capabilities of designers | 1.20 | 0.71 | 0.89 | 1.13 | ||

| Project performance improvement | 1.79 | 1.06 | 1.32 | 1.67 | ||

| Supply distance of construction products | 1.30 | 0.77 | 0.96 | 1.22 | ||

| 15. Urban and Territorial Planning | Strategies | Climate Change Adaptation Plan | 0.95 | 0.56 | 0.67 | 0.83 |

| Urban redevelopment programs | 1.04 | 0.61 | 0.74 | 0.92 | ||

| Mapping Vulnerability to Climate Events | 0.93 | 0.55 | 0.66 | 0.81 | ||

| Monitoring stations for climatic and/or seismic events | 1.05 | 0.62 | 0.75 | 0.93 | ||

| Digital information platforms (GIS, SIT) | 0.99 | 0.58 | 0.70 | 0.87 | ||

| 16. Economic evaluation of interventions using the LCC approach | Strategies | Lean Production | 1.52 | 0.89 | 1.12 | 1.42 |

| Lean Construction | 1.58 | 0.93 | 1.16 | 1.48 | ||

| Eco-effectiveness | 1.93 | 1.14 | 1.42 | 1.81 | ||

| Summary | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

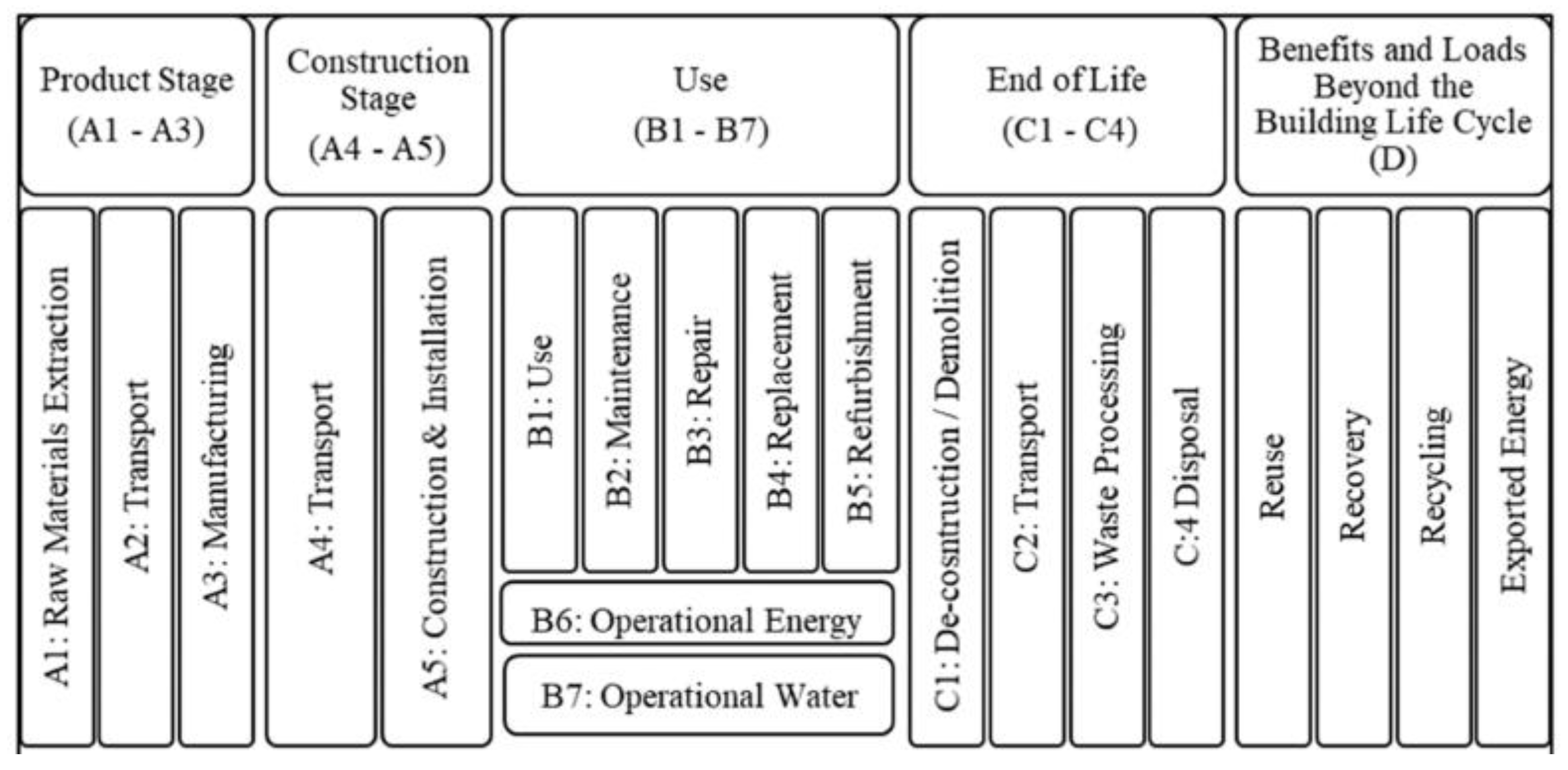

3.4. Building Life Cycle (BLC) Phase Model

| Indicator Categories | Strategic approach | Indicators | Weights versus Building Life Cycle (BLC) Phases | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1-A3 | A4-A5 | B1-B7 | C1-C4 | D | |||

| 1. Modular design | Passive strategies | Foundation structures | 1.04 | 0.75 | 0.52 | 1.16 | 0.70 |

| Elevation structures | 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.65 | 1.17 | 0.65 | ||

| Vertical closures (opaque and transparent) | 0.90 | 0.74 | 0.62 | 1.17 | 0.68 | ||

| Horizontal closures | 0.86 | 0.71 | 0.57 | 1.21 | 0.62 | ||

| Internal partitions | 0.93 | 0.75 | 0.60 | 1.05 | 0.57 | ||

| Active strategies | Plant components | 1.00 | 0.81 | 0.61 | 1.25 | 0.76 | |

| 2. Conservative design/ Existing recovery | Passive strategies | Disassembly and selective demolition | 1.02 | 0.94 | 0.51 | 1.17 | 1.44 |

| Load-bearing structure (wet system) | 0.89 | 0.64 | 0.57 | 0.96 | 0.89 | ||

| Load-bearing structure (dry system) | 1.09 | 0.75 | 0.59 | 1.04 | 1.02 | ||

| Vertical closures (wet system) | 0.93 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0.92 | 0.77 | ||

| Vertical closures (dry system) | 1.09 | 0.75 | 0.61 | 1.00 | 0.86 | ||

| Internal partitions (wet system) | 0.85 | 0.58 | 0.46 | 0.80 | 0.73 | ||

| Internal partitions (dry system) | 1.00 | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.88 | 0.78 | ||

| Insulation of opaque closures | 1.04 | 0.86 | 0.65 | 0.96 | 1.04 | ||

| 3. Design using a circular BIM-LCA approach | Passive strategies | Secondary raw material recovered or recycled | 1.45 | 1.00 | 0.78 | 1.20 | 1.21 |

| Materials derived from renewable raw materials | 1.53 | 1.07 | 0.87 | 1.21 | 1.33 | ||

| Materials with DAP/EPD certification (Environmental Product Declaration) | 1.45 | 0.99 | 0.91 | 1.29 | 1.28 | ||

| Selective demolition and recycling of excavated materials and construction and demolition waste (C&D) | 1.41 | 0.94 | 0.72 | 1.31 | 1.33 | ||

| Predictive and scheduled maintenance plan for the work | 0.70 | 0.81 | 1.21 | 1.04 | 1.15 | ||

| External closures and internal dry partitions | 1.00 | 0.76 | 1.02 | 0.80 | 1.39 | ||

| 4. NZEB Design | Passive strategies | Solar orientation | 0.81 | 0.94 | 1.12 | 0.47 | 0.76 |

| Shading with plant or architectural elements | 0.86 | 1.02 | 1.21 | 0.76 | 0.84 | ||

| Eco-friendly materials with low embodied carbon content | 1.20 | 0.98 | 1.09 | 1.12 | 1.09 | ||

| Insulation of opaque and transparent vertical closures | 0.70 | 1.03 | 1.21 | 0.87 | 0.81 | ||

| Sun protection devices | 0.67 | 0.91 | 1.14 | 1.01 | 1.24 | ||

| Natural ventilation systems | 0.86 | 1.06 | 1.16 | 0.80 | 0.96 | ||

| Active strategies | Heating and air conditioning systems | 0.56 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.79 | 1.02 | |

| Systems powered by renewable sources for the production of electricity and domestic hot water | 0.79 | 0.92 | 1.11 | 0.91 | 1.18 | ||

| Controlled mechanical ventilation systems | 0.58 | 0.81 | 0.90 | 0.89 | 0.94 | ||

| Flow reduction systems, flow control systems, water temperature control systems | 0.56 | 0.83 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 1.10 | ||

| Low water consumption sanitary appliances | 0.64 | 0.79 | 1.04 | 0.78 | 1.06 | ||

| High efficiency alternative systems (high efficiency cogeneration/trigeneration, centralized heat pumps) | 0.72 | 0.91 | 1.08 | 1.01 | 1.06 | ||

| Mixed strategies | Transparent vertical closures integrated with photovoltaic | 0.83 | 0.96 | 1.06 | 0.99 | 1.10 | |

| Integrated panels for external closures (BiPV) | 0.81 | 0.84 | 1.02 | 0.87 | 1.00 | ||

|

5. Eco-friendly design (CAM, SMART plant design) |

Passive strategies | Vehicles of the EEV (Improved Ecological Vehicle) category | 2.00 | 1.06 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.27 |

| Visual and noise shielding on construction sites | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.24 | 0.95 | 0.52 | ||

| Green or cold upper and vertical closures | 1.02 | 0.75 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.90 | ||

| Highly reflective opaque external closures (for roofing and casings) | 0.95 | 0.68 | 0.76 | 0.60 | 0.77 | ||

| Low-emissivity transparent external closures | 1.13 | 0.65 | 0.72 | 0.63 | 0.85 | ||

| Ecological thermal and acoustic insulation of opaque vertical closures and internal partitions | 1.21 | 0.81 | 0.88 | 0.74 | 0.72 | ||

| Natural lighting | 1.22 | 0.90 | 0.77 | 0.53 | 0.70 | ||

| Flooring and coverings with low VOC (volatile organic compound) release | 1.09 | 0.83 | 0.77 | 0.68 | 0.69 | ||

| Pollutant protection systems | 1.04 | 0.87 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.80 | ||

| Storage system for vital energy self-sufficiency in the event of disasters | 0.93 | 0.70 | 0.69 | 0.59 | 0.80 | ||

| Active strategies | Air quality control systems (during construction, building and occupation phases) | 1.06 | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.68 | 0.74 | |

| Lighting control and integration systems | 0.93 | 0.65 | 0.71 | 0.55 | 0.80 | ||

| Air flow and CO2 monitoring systems | 1.10 | 0.71 | 0.80 | 0.68 | 0.85 | ||

| Energy consumption monitoring system | 1.14 | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.71 | 0.88 | ||

| Home automation systems | 0.88 | 0.73 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.73 | ||

| 6. Aerodynamic design | Passive strategies | Compact building shape (curved facades) | 0.17 | 0.35 | 0.92 | 0.32 | 0.35 |

| Elevation structures | 0.88 | 0.74 | 0.80 | 0.87 | 0.76 | ||

| Coverings | 0.92 | 0.71 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.84 | ||

| Opaque vertical closures | 0.83 | 0.68 | 0.92 | 0.87 | 0.80 | ||

| Transparent vertical closures | 0.83 | 0.62 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.88 | ||

| 7. Design of water recovery and reuse systems | Passive strategies | Permeable flooring | 1.06 | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.74 |

| Infiltration grates and channels | 0.65 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.60 | 0.80 | ||

| Arrangement of green areas | 0.79 | 0.64 | 0.70 | 0.68 | 0.70 | ||

| Rainwater collection tank | 1.06 | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 1.01 | ||

| Wastewater storage tanks | 0.89 | 0.75 | 0.68 | 0.63 | 0.90 | ||

| Accumulation tanks for purified water | 1.02 | 0.85 | 0.79 | 0.68 | 0.93 | ||

| Toilet storage tanks | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.70 | 0.66 | 0.77 | ||

| Active strategies | Rainwater filtration and purification system | 1.18 | 0.94 | 0.84 | 0.71 | 0.88 | |

| Irrigation systems for green areas | 0.93 | 0.71 | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.93 | ||

| Wastewater treatment plant | 1.10 | 0.84 | 0.75 | 0.60 | 0.98 | ||

| 8. Fire safety design | Passive strategies | Fireproofing treatment for structural elements | 0.53 | 0.90 | 1.04 | 0.87 | 0.39 |

| Smoke-proof filter compartment | 0.50 | 0.82 | 0.93 | 0.62 | 0.66 | ||

| Insulation of internal closures and partitions | 0.42 | 0.86 | 1.01 | 0.64 | 0.39 | ||

| External vertical connections (fire escapes) | 0.45 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 0.88 | 1.08 | ||

| Compensatory water supply tank | 0.67 | 0.99 | 1.08 | 0.92 | 1.08 | ||

| Storage tank for waste water for auxiliary fire-fighting system supply | 0.75 | 0.96 | 1.03 | 0.92 | 1.00 | ||

| Active strategies | Detection and alarm systems | 0.42 | 0.65 | 0.93 | 0.59 | 0.80 | |

| Oxygen reduction systems | 0.50 | 0.65 | 0.90 | 0.67 | 0.72 | ||

| Fire water system | 0.53 | 0.94 | 1.01 | 0.71 | 0.60 | ||

| Automatic fire extinguishing systems | 0.61 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.67 | 0.60 | ||

| Auxiliary fire extinguishing system powered by recycled water | 0.67 | 0.82 | 0.98 | 0.79 | 0.68 | ||

| Smoke and heat evacuators | 0.45 | 0.82 | 0.96 | 0.83 | 0.68 | ||

| 9. Earthquake-proof design | Passive strategies | Foundation structures | 0.60 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.97 | 0.73 |

| Elevation structures | 0.60 | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.97 | 0.69 | ||

| Vertical closures | 0.46 | 0.65 | 0.70 | 0.81 | 0.77 | ||

| Horizontal internal partitions | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.78 | 0.57 | ||

| Structural reinforcement and consolidation systems | 0.50 | 0.79 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 0.82 | ||

| Seismic isolation systems for structures (insulators, dissipators) | 0.39 | 0.80 | 0.68 | 1.01 | 0.93 | ||

| Structural monitoring systems | 0.39 | 0.82 | 0.68 | 0.96 | 1.05 | ||

|

10. Multi-scale/integrated design |

Passive strategies |

Recovery of green areas and degraded sites | 0.95 | 0.66 | 0.73 | 1.01 | 1.17 |

| High reflectance covers | 0.81 | 0.63 | 0.75 | 0.81 | 0.81 | ||

| Flooring with high reflective power | 0.68 | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.76 | 0.77 | ||

| Photocatalytic surfaces | 0.77 | 0.63 | 0.77 | 0.93 | 0.69 | ||

| Flood barriers/anti-flood barriers | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.73 | 1.00 | 1.12 | ||

| Active strategies | Public lighting systems powered by renewable sources | 1.07 | 0.69 | 0.77 | 1.01 | 1.04 | |

| Rainwater collection, purification and reuse plants | 1.11 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 1.05 | 1.16 | ||

| Irrigation systems powered by renewable sources | 1.07 | 0.75 | 0.79 | 1.13 | 1.28 | ||

| District heating and cooling networks | 0.95 | 0.56 | 0.63 | 0.97 | 1.08 | ||

|

11. Eliminating barriers architectural |

Strategies | External and internal routes | 0.53 | 0.63 | 0.73 | 0.58 | 0.64 |

| Parking spaces | 0.50 | 0.66 | 0.73 | 0.63 | 0.66 | ||

| Rest and rest areas along the routes | 0.50 | 0.57 | 0.67 | 0.55 | 0.64 | ||

| Vertical and inclined connections | 0.47 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.58 | 0.72 | ||

| Dedicated toilet facilities | 0.53 | 0.68 | 0.76 | 0.63 | 0.74 | ||

| Acoustic warning devices | 0.45 | 0.58 | 0.62 | 0.50 | 0.69 | ||

| Environmental Sensors | 0.56 | 0.70 | 0.67 | 0.53 | 0.69 | ||

| 12. Participatory design | Strategies | Involvement and openness towards the community | 0.61 | 0.52 | 0.67 | 0.32 | 0.48 |

| Participated tables | 0.58 | 0.46 | 0.67 | 0.32 | 0.48 | ||

| Event organization | 0.61 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 0.32 | 0.51 | ||

| 13. Inclusive / adaptive design | Strategies | Modular design for emergency/reception | 0.67 | 1.25 | 1.05 | 1.50 | 0.94 |

| Co-housing | 0.61 | 1.13 | 1.05 | 1.29 | 0.90 | ||

| Designing accessible and shared spaces | 0.70 | 1.13 | 1.48 | 1.34 | 0.94 | ||

| 14. Sustainable Tenders (CAM - PAN GPP) | Strategies | Candidate selection | 0.22 | 1.18 | 0.73 | 1.10 | 0.21 |

| Technical specifications | 0.50 | 1.26 | 1.31 | 1.31 | 0.96 | ||

| Conditions of execution | 0.45 | 1.26 | 1.09 | 1.31 | 0.90 | ||

| OEPV Award (Most Economically Advantageous Offer) | 0.33 | 1.18 | 0.87 | 0.16 | 0.21 | ||

| Technical capabilities of designers | 0.45 | 1.31 | 1.19 | 1.26 | 0.32 | ||

| Project performance improvement | 1.89 | 1.31 | 1.42 | 1.21 | 1.21 | ||

| Supply distance of construction products | 1.84 | 1.14 | 0.28 | 1.05 | 0.90 | ||

|

15. Urban and Territorial Planning |

Strategies | Climate Change Adaptation Plan | 0.58 | 0.94 | 1.35 | 0.29 | 0.29 |

| Urban redevelopment programs | 0.64 | 1.10 | 1.17 | 0.50 | 0.40 | ||

| Mapping Vulnerability to Climate Events | 0.36 | 0.94 | 1.22 | 0.29 | 0.56 | ||

| Monitoring stations for climatic and/or seismic events | 0.31 | 1.14 | 1.45 | 0.29 | 0.61 | ||

| Digital information platforms (GIS, SIT) | 0.36 | 1.02 | 1.31 | 0.34 | 0.56 | ||

| 16. Economic evaluation of interventions using the LCC approach | Strategies | Lean Production | 1.78 | 0.98 | 0.87 | 1.16 | 1.28 |

| Lean Construction | 1.22 | 1.31 | 0.87 | 1.37 | 1.44 | ||

| Eco-effectiveness | 1.84 | 1.31 | 1.33 | 1.52 | 1.65 | ||

| Summary | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

3.5. Assessment of the Resilience Factor

4. Case Studies

4.1. Case Study Selection Criteria

4.2. Description of Case Studies

4.2.1. Multipurpose Building

4.2.2. Laboratory Building

4.3. Applying the Model to Case Studies

4.3.1. Application of the Model According to the CAM Areas (Table 7)

4.3.2. Application of the Model Based on the Life Cycle Phases of Buildings (Table 8)

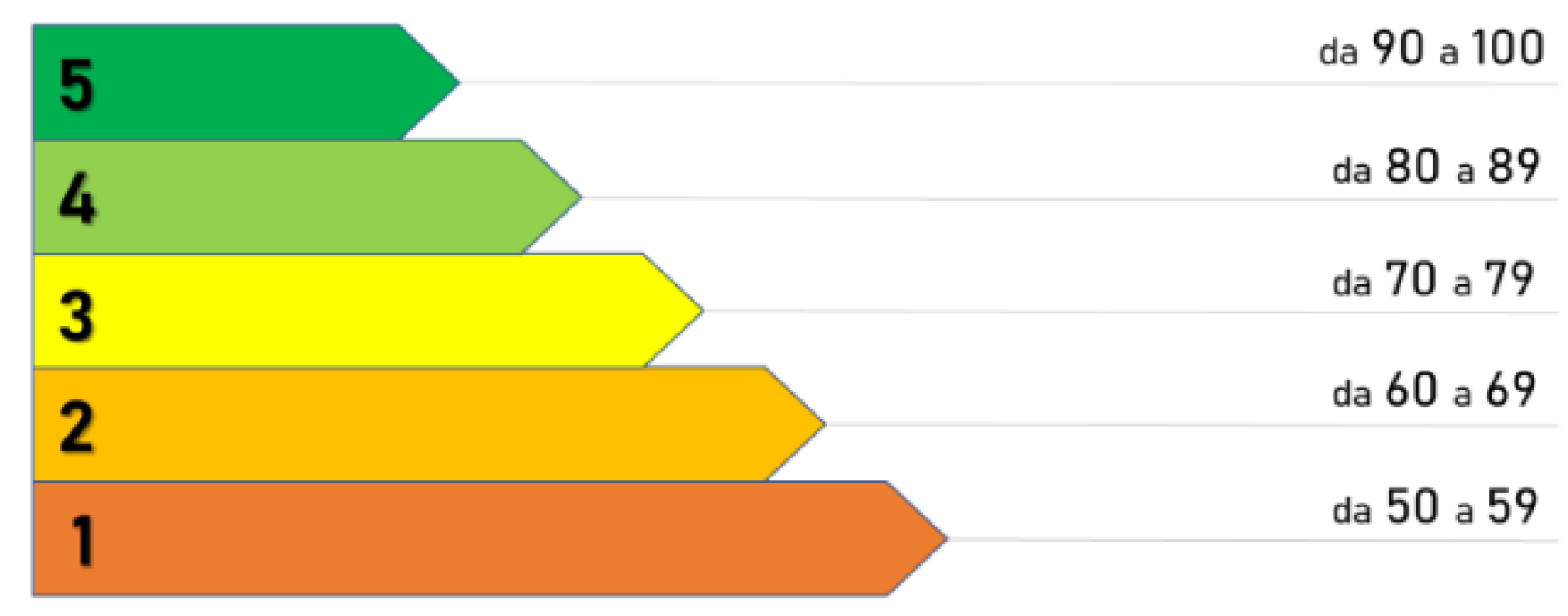

5. Results and Discussion

| Multipurpose Building | CAM Model | BLC Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Building System | Production Phase A1-A3 |

Construction Phase A4-A5 |

Exercise Phase B1-B7 |

End of life phase C1-C4 |

Benefits beyond the system D |

|

| Building Components System | ||||||

| Indicators Summary | 65.88 | 60.38 | 62.05 | 59.55 | 62.57 | 59.51 |

| Resilience Factor | 66 | 60 | 62 | 60 | 63 | 60 |

| Laboratory Building | CAM Model | BLC Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Building System | Production Phase A1-A3 |

Construction Phase A4-A5 |

Exercise Phase B1-B7 |

End of life phase C1-C4 |

Benefits beyond the system D |

|

| Building Components System | ||||||

| Indicators Summary | 39.92 | 36,18 | 39,32 | 38.64 | 39.68 | 34.82 |

| Resilience Factor | 40 | 36 | 39 | 39 | 40 | 35 |

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAM | Criteri Ambientali Minimi italiani (Minimum Environmental Criteria) |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| BLC | Building Life Cycle |

| EPD | Environmental Product Declaration |

References

- Dand Wilde, P., Coley, D. Editorial, Implications of a changing climate for buildings. Building and Environment, Vol.56. 2012.

- Lacasse MA; Gaur A.; Moore TV Durability and Climate Change—Implications for Service Life Prediction and the Maintainability of Buildings. Buildings 2020, 10(3), 53; [CrossRef]

- Mussi, G. “Resilient and sustainable architecture” The portal for construction and architecture Infobuild 2019 Source: https://www.infobuild.it/approfondimenti/architettura-resiliente-sostenibile-progettazione-urbana/.

- Mussi, G. “Five choices for a more sustainable construction” The portal for construction and architecture Infobuild 2020 Source: https://www.infobuild.it/approfondimenti/5-scelte-per-edilizia-sostenibile/.

- Saifudeen, A.; Mani , M. Adaptation of buildings to climate change: an overview, 16 Feb 2024 - Frontiers in Built Environment. [CrossRef]

- Kulsum, F. Sustainable and Resilient Architecture: Prioritizing Climate Change Adaptation, Civil Engineering and Architecture 12(1): 577-585. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D. Towards Resilient Urban Design: Revealing the Impacts of Built Environment on Physical Activity Amidst Climate Change. Buildings 2025, 15(19), 3470;. [CrossRef]

- Pallubinsky, H.; Kramer, R.P. & van Marken Lichtenbelt, W.D. Establishing resilience in times of climate change—a perspective on humans and buildings. Climatic Change 176, 135 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Ljubomir, J. Designing Resilience of the Built Environment to Extreme Weather Events, Sustainability 2018, 10(1), 141;. [CrossRef]

- Katunský, D.; Kabošová, L.; Dolníková, E.; Zozulák, M. Research of building structures in extreme climate conditions. Journal of Civil Engineering. Volume 14 (2019): Issue 2 (December 2019). [CrossRef]

- Pastori, S. and Mazzucchelli, E.S. Climate Change and Extreme Wind Events: Overview and Perspectives for a Resilient Built Environment, IntechOpen 01 June 2023. [CrossRef]

- Blandon, B.; Palmero, L.; Di Ruocco, G. The Revaluation of Uninhabited Popular Heritage under Environmental and Sus-tainability Parameters. Sustainability 2020, 12(14), 5629;. [CrossRef]

- Popowicz, M., Katzer, N.J., Kettele, M. et al. Digital technologies for life cycle assessment: a review and integrated combination framework. Int J Life Cycle Assess 30, 405–428 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Lima, S.; Duarte. S.; Exenberger, H.; Fröch, G.; Flora, M. Integrating BIM-LCA to Enhance Sustainability Assessments of Constructions. Sustainability 2024, 16(3), 1172;. [CrossRef]

- Bruno, A.; Menichini. T.; Silversti, L. Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA): A comprehensive overview of existing integrated approaches to LCA, S-LCA, and LCC. European Journal of Sustainable Development. Vol. 14 No. 3 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Cerchione, R.; Morelli, M.; Passaro, R.; Quinto, I. A critical analysis of the integration of life cycle methods and quantitative methods for sustainability assessment. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management. Volume 32, Issue 2. October 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bani, K.; Despoina, D.; Avgoustaki, D.; Bartzanas, T. Integrating life cycle assessment into green infrastructure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of urban sustainability strategies. Front. Sustain. Cities, 18 June 2025. Sec. Urban Greening. Volume 7 – 2025. [CrossRef]

- Backes, J.G.; Steinberg, L.S.; Weniger, A.; Traverso, M. Visualization and Interpretation of Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment—Existing Tools and Future Development. Sustainability 2023, 15(13), 10658; [CrossRef]

- Moutik, B.; Summerscales, J.; Graham-Jones, J.; Pemberton, R. Life Cycle Assessment Research Trends and Implications: A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15(18), 13408. [CrossRef]

- Rao, P.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Duraman, S.B. Adopting circular economy in construction: a review. Front. Built Environ., 20 January 2025. Volume 11 – 2025. [CrossRef]

- Gasparri, E.; Arasteh, S.; Stracchi, P.; Brambilla, A. Circular economy in construction: A systematic review of knowledge gaps towards a novel research framework. Front. Built Environ., 19 July 2023. Volume 9 – 2023. [CrossRef]

- Krajewska, A.; Siewczyńska, M. Circular Economy in the Construction Sector in Materials, Processes, and Case Studies: Research Review. Sustainability 2025, 17(15), 7029. [CrossRef]

- Idir, R.; Djerbi, A.; Tazi, N. Optimising the Circular Economy for Construction and Demolition Waste Management in Europe: Best Practices, Innovations and Regulatory Avenues. Sustainability 2025, 17(8), 3586. [CrossRef]

- Firoozi, A.A.; Firoozi, A.A. Circular Economy for Sustainable Construction Material Management. Journal of Civil Engineering and Urbanism. Volume 12, Issue 4: 70-81; December 2025. [CrossRef]

- Jayakodi, S.; Senaratne, S.; Perera, S. Circular Economy Business Model in the Construction Industry: A Systematic Review. Buildings 2024, 14(2), 379. [CrossRef]

- Otasowie, O.; Aigbavboa, C.; Oke, A.E.; Adekunle, P. Circular economy business model: an exploratory study on the key resources for construction organisations. Built Environment Project and Asset Management 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Keles, C.; Rios, F.C.; Hoque, S. Digital Technologies and Circular Economy in the Construction Sector: A Review of Lifecycle Applications, Integrations, Potential, and Limitations. Buildings 2025, 15(4), 553. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, N.; Omrany, H.; Chang, R.; Zuo, J. Leveraging digital technologies for circular economy in construction industry: a way forward. Smart and Sustainable Built Environment, vol. 13, issue 1, pp. 85-116. [CrossRef]

- Ibe, C.N.; Serbescu, A.; Hossain, M.; Ibe, I.I. Optimizing circular economy practices in construction: a systematic review of material management strategies. Built Environment Project and Asset Management. 15 (5), pp. 1020-1035. [CrossRef]

- Wieser, A.A.; Scherz, M.; Passer, A.; Kreiner, H. Challenges of a Healthy Built Environment: Air Pollution in Construction Industry. Sustainability 2021, 13(18), 10469;. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Luo, T.; Luo, H. et al. A comprehensive review of building lifecycle carbon emissions and reduction approaches. City Built Enviro 2, 12 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Wu, Z.; Yu, Z.; Wang, T.; Huang, S. Exploring Carbon Emissions in the Construction Industry: A Review of Accounting Scales, Boundaries, Trends, and Gaps. Buildings 2025, 15(11), 1900. [CrossRef]

- Building Materials And The Climate: Constructing A New Future, 12 September 2023 (UNEP, 2023). Available on: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/building-materials-and-climate-constructing-new-future.

- Aparna, K.; Baskar, K. Scientometric analysis and panoramic review on life cycle assessment in the construction industry, in Innovative Infrastructure Solutions, Volume 9, Issue 4, article id.96, April 2024. [CrossRef]

- Rathnasinghe, A.P.; Thurairajah, N.; Jones, P.; Goulding, J. The critique of sustainability discourse within the off-site construction (OSC): a systematic-scientometric review, in Architectural Engineering and Design Management. [CrossRef]

- Olayiwola, K.; Perera, S.; Kagioglou, M.; Jin, X.; Sharafi, P. A PESTEL Analysis of Problems Associated with the Adoption of Offsite Construction: A Systematic Literature Review. Buildings 2025, 15(13), 2146. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, C.C.; Sepasgozar, S.; Zlatanova, S. A Systematic Review of Digital Technology Adoption in Off-Site Construction: Current Status and Future Direction towards Industry 4.0. Buildings 2020, 10(11), 204. [CrossRef]

- Najafzadeh, M.; Yeganeh, A. AI-Driven Digital Twins in Industrialized Offsite Construction: A Systematic Review. Buildings 2025, 15(17), 2997. [CrossRef]

- Di Ruocco, G.; Melella, R. Evaluation of environmental sustainability threshold of “humid” and “dry” building systems, for reduction of embodied carbon (CO2). VITRUVIO - International Journal of Architectural Technology and Sustainability. [CrossRef]

- Sicignano, E.; Di Ruocco, G.; Melella, R. Mitigation Strategies for Reduction of Embodied Energy and Carbon, in the Construction Systems of Contemporary Quality Architecture. Sustainability 2019, 11(14), 3806;. [CrossRef]

- Broadhead, J. P.; Daniel E. I.; Oshodi, O.; Ahmed, S. (2023). Exploring offsite construction for the construction sector: a literature review. Proceedings of the 31st Annual Conference of the International Group for Lean Construction (IGLC31), 735–745. Modular & Offsite Construction 735. [CrossRef]

- Manouchehri, B.; Han, S.: Nasiri, F. Performance Evaluation Model to Enhance Life Cycle Productivity in Modular and Off-Site Construction: A Process-Oriented Approach, in 2025 Proceedings of the 42nd ISARC, Montreal, Canada, pp. 556-563. [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.; Ahn, S.; Cha, S.H.; Cho, K.; Koo, C.; Kim, T.W. Toward productivity in future construction: mapping knowledge and finding insights for achieving successful offsite construction projects Open Access, in Journal of Computational Design and Engineering, Volume 8, Issue 1, February 2021, pp. 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Tang, S.; Liu, H.; Lei, Z. Digital Technologies in Offsite and Prefabricated Construction: Theories and Applications. Buildings 2023, 13(1), 163. [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.; Mills, G.; Papadonikolaki, E.; Li, B.; Huang, J. Digital-enabled Design for Manufacture and Assembly (DfMA) in offsite construction: A modularity perspective for the product and process integration, in Architectural Engineering and Design Management, Volume 19, 2023 - Issue 3, pp. 267-282. [CrossRef]

- Parracho, D. et al. Modular Construction in the Digital Age: A Systematic Review on Smart and Sustainable Innovations. Buildings 2025, 15(5), 765. [CrossRef]

- Saifudeen, A.; Mani, M. Adaptation of buildings to climate change: an overview, in Front. Built Environ., 16 February 2024. Sec. Sustainable Design and Construction, Volume 10 – 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tajuddeen, I.; Sajjadian, S.M. Climate change and the built environment - a systematic review. Environ Dev Sustain (2024). [CrossRef]

- EU-LEVEL TECHNICAL GUIDANCE ON ADAPTING BUILDINGS TO CLIMATE CHANGE. Available on: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/7cca7ab9-cc5e-11ed-a05c-01aa75ed71a1/language-en.

- Bouramdane, A-A. Shaping resilient buildings and cities: Climate change impacts, metrics, and strategies for mitigation and adaptation. College of Engineering and Architecture, International University of Rabat (IUR), IUR Campus, Technopolis Park, Rocade Rabat-Salé, Sala Al Jadida 11103, Morocco. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ramakrishnan, S. Resilience and Adaptation in Buildings. In: Environmental Sustainability in Building Design and Construction. Springer, Cham, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Chamindi Malalgoda et al. Climate Change Adaptation in the Built Environment. Transdisciplinary and Innovative Learning, 2025. Available on: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-75826-3.

- Agency 2030 for Sustainable Development - Agency for Territorial Cohesion. Website:https://www.agenziacoesione.gov.it/comunicazione/agenda-2030-per-lo-sviluppo-sostenibile/.

- Moncaster, A.; Symons, K. A method and tool for 'cradle to grave' embodied energy and carbon impacts of UK buildings in compliance with the new TC350 standards. Energy and Buildings 66(11):514–523. 2013.

- Ministero dell'Ambiente e della Sicurezza Energetica. Sostenibilità dei prodotti e dei consumi - CAM e Certificazioni. Available on : https://gpp.mase.gov.it/sites/default/files/2024-08/allegato-tecnico-CAM-edilizia-07-06-2022-rev-correttivo.pdf.

- Cellura, T.; Cellura, L. The new manual of Minimum Environmental Criteria in Construction, Maggioli Editore. Italy, 2018.

| Satisfaction Coefficient | Assessment |

|---|---|

| 0 | Nothing |

| 0.33 | Rare |

| 0.66 | Good |

| 1.00 | Optimal |

| Intrinsic characteristics regarding the construction and technological system | Multipurpose Building | Laboratory Building |

|---|---|---|

| Modular elevation structures | 1 | 0.33 |

| Disassembly and selective demolition | 1 | 0 |

| Materials with DAP/EPD certification (Environmental Product Declaration) [UNI EN 15804 and ISO 14025] | 1 | 0 |

| Elevation structures for aerodynamic design | 1 | 0 |

| External vertical connections (fire escapes) | 1 | 0 |

| Structural monitoring systems | 1 | 0 |

| Intrinsic characteristics regarding the relationship between the building and the environment | Multipurpose Building | Laboratory Building |

| Predictive and scheduled maintenance plan of the work | 1 | 0 |

| Sun protection devices | 1 | 0 |

| Natural ventilation systems | 1 | 0 |

| Highly reflective opaque external closures (for roofing and casings) | 1 | 0 |

| Low-emissivity transparent external closures | 1 | 0 |

| Lean Construction | 1 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).