1. Introduction

In the United Kingdom, the rise in diet-related health issues has spurred extensive discussions on improving the population’s dietary quality. Data indicates that over half of dietary energy intake is derived from ultra-processed food consumption [

1,

2]. Indeed, the UK ranked third in per capita sales volume (140.7 kg/capita/year) in a 2019 assessment of worldwide trends in ultra-processed foods [

3]. The high reliance on these products contributes to population-level intakes of saturated fat, sodium, and free sugar far exceeds the recommended limits. The consumption of this food category is a significant factor in the sustained high prevalence of overweight and obesity, impacting over 60% of the UK population. These conditions are widely recognized as increasing the risk of cardiovascular disease and various forms of cancer [

4,

5].

Ready-to-eat meals (REM) represent one of the fastest-growing ultra-processed food categories, with a 90% penetration rate in the UK [

6]. REM are products cooked in advance and sold ready for consumption or with minimal preparation [

7,

8]. These products often present a more economical choice compared to home-cooked alternatives [

6,

9], and their consumption is also frequently driven by the convenience of saving time. Attributed to their perceived consumer benefits, REM meals has emerged as the second most frequently consumed ultra-processed food category in the UK for almost the past two decades [

2]. Currently, REM account for 7.8% of the total energy intake among the adult population, with approximately 18.75 kg of chilled and frozen ready meals consumed per capita annually [

1,

10].

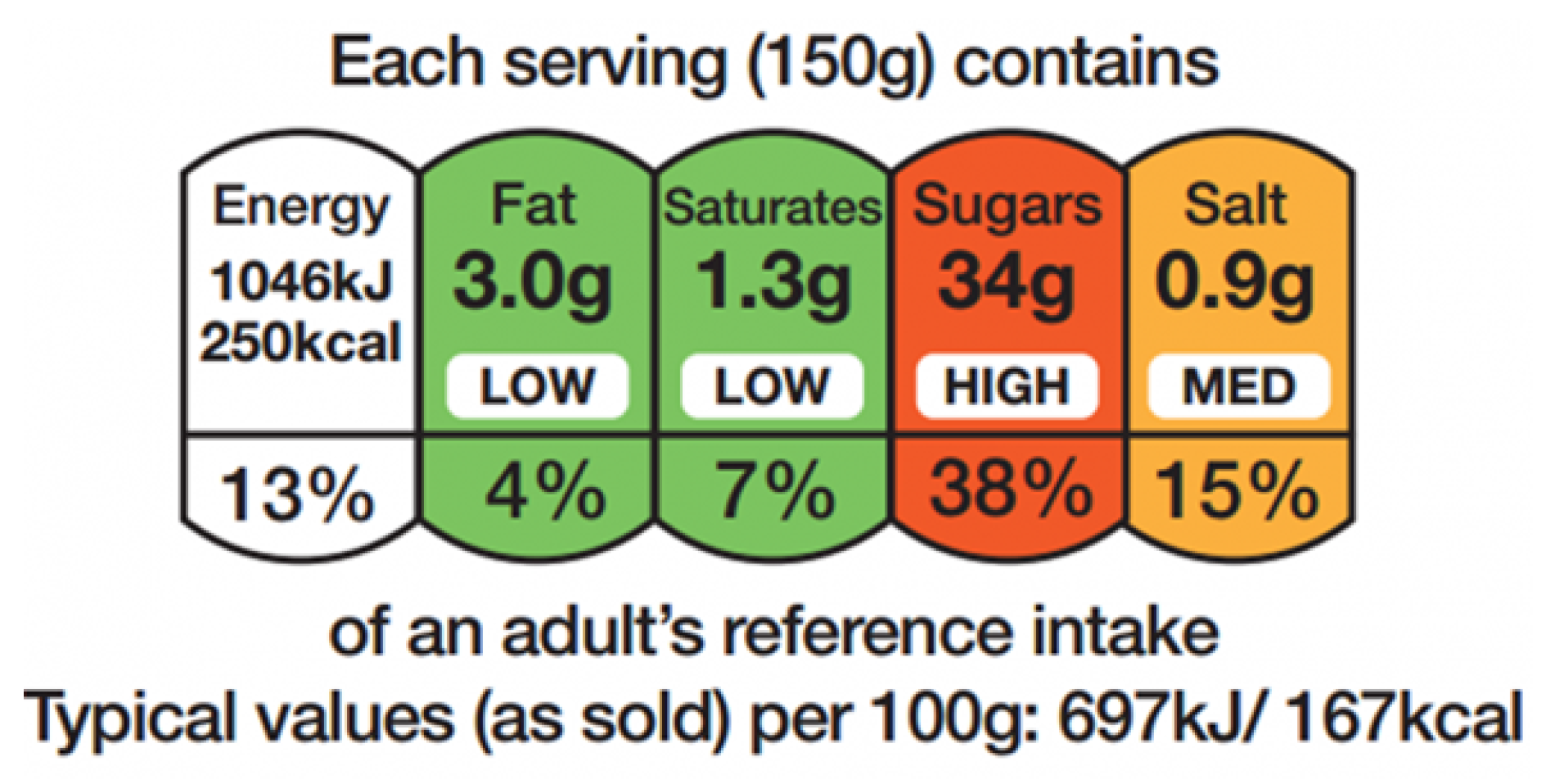

Public interventions have aimed to reduce the consumption of REM among the population. In particular, the UK government introduced the multiple traffic light (MTL) front-of-pack labelling policy in 2013 to signal the adverse nutrient profile of REM and similar convenience products [

11]. Compared to earlier versions, MTL is considered a larger, eye-catching, color-coded print label used by retailers on their food packages (see

Figure 1). This nutritional labelling aimed to provide consumers with a quick and easy way to assess the nutritional content of food and beverage products, thereby facilitating informed dietary choices. By specifically employing red as a warning color to indicate high levels of saturated fat, sugar, and salt, policymakers made the nutritional characteristics of this ultra-processed food category unmistakable to shoppers [

12]. Recent market-wide audits revealed that 94% of all REMs sold at retail outlets received a red and/or amber warning for one of the MTL nutrients, confirming the negative nutritional homogeneity of the category [

9,

13]. Despite this salient signaling, the percentage of total REM energy intake has paradoxically increased even after the implementation of the MTL system [

14].

Following the introduction of the MTL policy in the UK, the expectation was that this visual warning—coupled with voluntary industry uptake—would steer demand away from REM products [

15,

16,

17]. Nevertheless, while post-implementation surveys indicated that nine in ten shoppers reported them as a salient clue for healthy choices [

18], scanner data reveal only modest shifts in actual REM purchasing behavior [

16,

17,

19,

20,

21]. A plausible explanation for this ineffectiveness is that the red warning only affects choices when consumers can comfortably read the message it contains, considering both the surface area it occupies on the packaging and, specifically, the font size. Currently, the UK’s Food Standards Agency specifies a minimum font size of 1.2mm for MTL, which decreases to 0.9mm if the label’s surface area is under 80cm² [

22]. Given that the surface area of the MTL in proportion to the package size is minuscule, it is reasonable to assume that the warnings have been difficult for many consumers to discern, potentially leading to the MTL going unnoticed by a segment of the population.

Despite these observations, empirical research specifically investigating the salience of print size within the MTL system has been notably limited [

21,

23,

24]. While previous studies on MTL effectiveness have explored nutrient ranking and interpretive symbols, few have isolated print size as a distinct feature. Existing research often assumes typography is readable, focusing instead on whether shoppers decode the colour rules, leaving unanswered the question of whether print size itself limits or enables behavioural change [

25,

26,

27]. From a psychological perspective, the clarity and simplicity with which information is presented on a label significantly affect how people effectively use it. Individuals possess limited attentional and cognitive capacities, necessitating a careful balance between the time and effort required to interpret information [

28]. Consequently, appropriate print sizes can enhance consumers’ ability to make optimal purchasing decisions by improving attention and, subsequently, understanding [

29]. Indeed, the labelling literature frames the transition from label salience to label understanding as the pathway through which consumers develop subjective understanding—a personal confidence and feeling of being informed that predicts behavioral change [

30,

31,

32,

33]. This is distinct from objective understanding, emphasizing that a favorable perception of a label can positively influence choice, even without perfect factual recall [

33,

34].

Label understanding is not uniform; instead, it is often shaped and filtered by consumers’ pre-existing beliefs and health motivation [

29,

35,

36]. For instance, the clarity of visual presentations and the structure of patient consent texts influence how accurately patients decode and interpret information, with their impact often contingent on individuals’ preconceived notions and experiences [

37,

38,

39,

40]. Similarly, in the context of food choices, empirical research indicates that consumers concerned about food safety and actively seeking nutritional information may be influenced by their perceptions of threats and their assessment of the advantages of taking action, consistent with the health belief model [

41,

42,

43].

This research investigates the association between consumers’ perceived readability of MTL print size and food consumption frequency, specifically by testing the hypothesized salience-to-understanding pathway. However, examining this relationship presents a critical methodological challenge related to the label’s specific content. Isolating the effect of label readability necessitates distinguishing the text’s visual clarity from the nutritional message’s valence. Enhanced readability does not inherently deter consumption; instead, it amplifies the message encoded on the package. Consequently, a highly readable label could theoretically suppress consumption if it signals unhealthiness via red warnings, or conversely, promote it if green indicators signal healthiness [

44,

45]. Previous approaches that group heterogeneous food categories risk obscuring these opposing effects [

12,

16,

46], making it difficult to ascertain whether readability drives behavioral change through a specific warning signal or merely through broadly increased product visibility.

To mitigate potential threats to internal validity, this study employs a quasi-experimental design, specifically utilizing non-equivalent dependent variables (NEDVs) [

47,

48]. This approach enhances causal inference by comparing the target outcome with control outcomes that, while exposed to analogous environmental historical influences, are theoretically isolated from the specific causal warning mechanism under investigation [

49]. More precisely, the consumption frequency of red warning labeled products, namely pre-packaged sandwiches and pre-cooked meat, is contrasted against that of dairy products and fresh meat. Dairy products serve as a healthy-labeled control, characterized by green or amber nutritional signals [

1,

2,

13], whereas fresh meat functions as an unlabeled falsification test.

This study thus aims to achieve two objectives: 1) to investigate the association between the perceived readability of MTL print size and consumption frequency across specified product categories, and 2) to ascertain whether these associations exhibit heterogeneity among consumer subgroups characterized by their pre-existing health beliefs. We propose a content-dependent hypothesis, positing that a significant association between readability and consumption will be observed for REM-labeled products, where the salience-to-understanding pathway operates as a warning mechanism. Conversely, for healthy-labeled control products, where the label reinforces rather than warns, we anticipate a null or distinct association. Furthermore, a null association is hypothesized for the unlabeled control, given the complete absence of the warning mechanism. By analyzing population-level observational data collected from 2012 to 2018, this design allows for a rigorous examination of whether readability functions as a genuine warning mechanism, rather than merely contributing to increased general product salience.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

Table 1 details the sociodemographic characteristics of the 8,948 participants, stratified by their consumption frequency of pre-packaged sandwiches, pre-cooked meat, dairy, and fresh meat. The demographic profiles of these consumer segments illustrate distinct consumption patterns across product categories. For sandwiches, high-frequency consumption was notably more prevalent among women (62.4%) compared to non-consumers (45.8%). This segment of frequent consumers was also significantly younger, with individuals in the 18-24 (19.9%) and 25-34 (23.8%) age brackets being highly represented, whereas the 65+ age group predominantly comprised non-consumers (27. 8%). Furthermore, individuals without religious affiliation demonstrated a greater concentration among weekly consumers (41.9%) compared to those who never consumed these products (29.3%).

In contrast, the demographic profile of pre-cooked meat consumers presents distinct characteristics. Specifically, the gender distribution transitions from a predominantly male (55.0%) representation among non-consumers to a majority female (53.0%) composition among those who consume these products weekly. Contrary to sandwich consumption patterns, older age cohorts exhibit higher consumption rates, with individuals aged 65+ forming a significant proportion of both monthly (24.7%) and weekly (20.7%) consumers. Furthermore, religious affiliation demonstrates a divergent trend, as Christians constitute a substantial majority of weekly consumers (63.8%), whereas individuals identifying with other religions are disproportionately prevalent among non-consumers (22.8%). The consumption patterns for dairy and fresh meat also reveal unique demographic distributions. Dairy product consumption is nearly universal, with the predominant portion of the sample belonging to the weekly consumption category. This segment demonstrates a balanced gender representation (49.9% male) and comprises a considerable proportion of older consumers (21.0% aged 65+). The demographic profile for fresh meat consumption largely corresponds to that of pre-cooked meat, indicating a shift from a majority male (59.4%) non-consumer group to a majority female (53.1%) weekly consumer group, alongside a comparably high incidence of older adults (21.8%) within the weekly consumption cohort.

Across all four product categories, lower-income households consistently comprised a larger proportion of monthly and weekly consumer segments compared to non-consumers. Similarly, characteristics such as household size and marital status exhibited heterogeneous distributions across consumption levels, thereby highlighting the distinct demographic compositions of each consumer segment.

Table 2 indicates differentiated behavioral profiles across the product categories. Specifically, a discernible pattern regarding shopping responsibility is evident among sandwich consumers, where individuals with reduced responsibility (Sometimes/Never) exhibit a higher concentration within the frequent consumption segment (56.6%, weekly) compared to non-consumers (43.7%). This association, however, does not extend to other product categories. For pre-cooked meat, dairy, and fresh meat, the distribution of shopping responsibility demonstrates greater uniformity across all consumption frequencies.

Concerns pertaining to safe eating practices exhibited divergent relationships across the product categories. For pre-packaged sandwiches, a higher prevalence of individuals with significant safety concerns was observed among weekly (25.8%) consumers compared to monthly consumers (17.7%). Conversely, regarding pre-cooked meat, elevated safety concerns were most frequently noted among non-consumers (34.3%). This inverse correlation was even more pronounced for dairy products, where the highest level of concern was identified among individuals who never consumed the product (34.3%), while the lowest concern was evident among weekly consumers (20.8%). In contrast, for fresh meat, the degree of high concern remained notably consistent, at approximately 21%, across all consumption groups. Furthermore, information-seeking behavior emerged as a distinguishing factor exclusively for sandwich consumption, with active information seekers constituting a larger proportion of the weekly consumer segment (84.1%) relative to the non-consumer group (79.5%). However, for pre-cooked meat, dairy, and fresh meat, the proportion of information seekers remained stable at approximately 81-83% across all consumption levels, indicating that this behavior did not serve as a key differentiator for these particular products.

Temporal analysis of the survey year variable indicates shifts in the consumer base across all product categories. For sandwich consumption, the 2018 cohort demonstrated the highest proportion among monthly consumers (28.6%). A comparable trend was observed for pre-cooked meat, fresh meat, and dairy products, with the 2018 cohort also predominantly represented within their respective monthly consumption groups (30.2%, 33.7%, and 40.3%, respectively). Conversely, for these latter three categories, the 2018 cohort exhibited the lowest representation among weekly consumers, a pattern distinct from that seen for sandwiches.

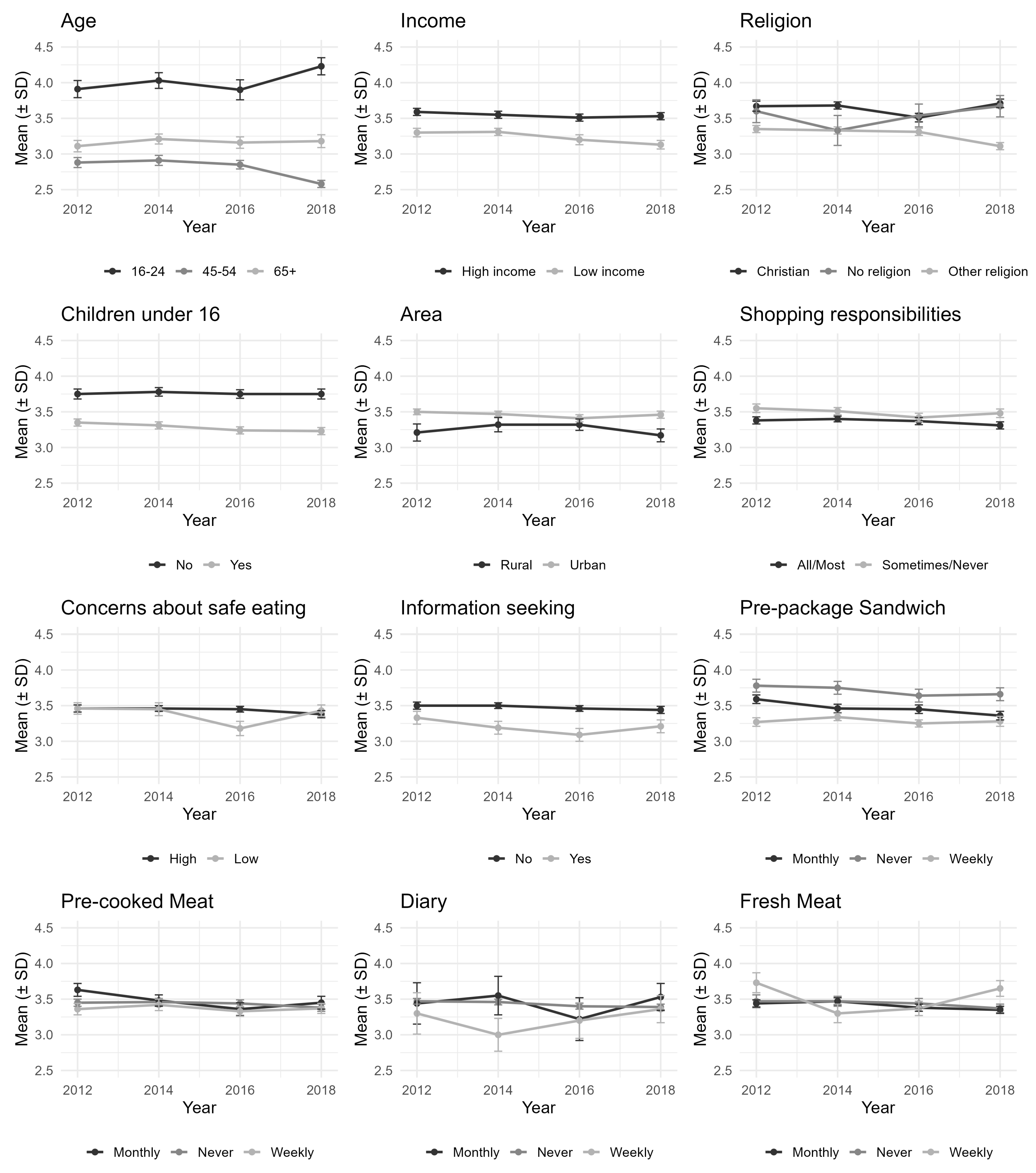

3.2. Perceived MTL Print Size Readability

Figure 2 illustrates the perceived readability of MTL print size among diverse demographic and behavioral subgroups from 2012 to 2018. Where higher scores denote enhanced readability, the findings delineate significant disparities in food label perception across distinct subgroups. A pronounced and consistent age-related pattern is observed. Specifically, younger respondents (16–24 years) consistently reported the greatest ease of label comprehension, with their mean scores demonstrating an upward trajectory from 3.91 in 2012 to a peak of 4.23 in 2018. In contrast, middle-aged cohorts (45–54) experienced the most significant challenges in readability, indicated by a decline in scores from 2.88 to 2.58 during the corresponding timeframe. Older adults (65+), however, reported a moderate level of reading ease, characterized by stable mean scores approximating 3.2.

Household and socioeconomic factors also reveal distinct patterns. Respondents from high-income households (means around 3.5-3.6) consistently found labels easier to read than those from low-income households (means around 3.1-3.3). Similarly, those with no children at home reported significantly greater ease of reading (mean 3.75) than those with children (mean approximately 3.3). Geographically, residents in Wales reported finding labels easiest to read in 2012 (mean = 3.92), though this level later converged with England and Northern Ireland. Behavioral characteristics were also associated with perceived readability. Individuals who do not actively seek food information (mean 3.50 in 2012) reported greater ease of reading than active information seekers (mean 3.33 in 2012). Likewise, those with less shopping responsibility (Sometimes/Never) reported finding labels easier to read (mean approximately 3.5) than those with primary responsibility (mean around 3.4). Differences based on food safety concerns were less pronounced, with both high- and low-concern groups reporting similar levels of readability.

Regarding pre-packaged sandwiches, a distinct and consistent hierarchical pattern in perceived readability is evident across various consumption subgroups. Specifically, individuals categorized as never consumers consistently reported the highest mean readability scores, fluctuating between 3.78 in 2012 and 3.66 in 2018. Conversely, weekly consumers consistently indicated the lowest mean readability. In the context of pre-cooked meat, the observed pattern is less clearly delineated. Although monthly consumers generally reported the greatest ease of reading (mean 3.63 in 2012), the readability values across all three consumption segments were considerably similar and exhibited convergence over the study period, thus precluding the establishment of an enduring hierarchy. Dairy products revealed a hierarchical structure akin to that observed for sandwiches, albeit less pronounced: never consumers (mean 3.47 in 2012) and monthly consumers (mean 3.44 in 2012) consistently reported higher readability levels compared to the predominant weekly consumer subgroup. For fresh meat, the pattern is again less distinct and more closely resembles pre-cooked meat.

3.3. Perceived MTL Print Size Readability and Food Consumption Associations

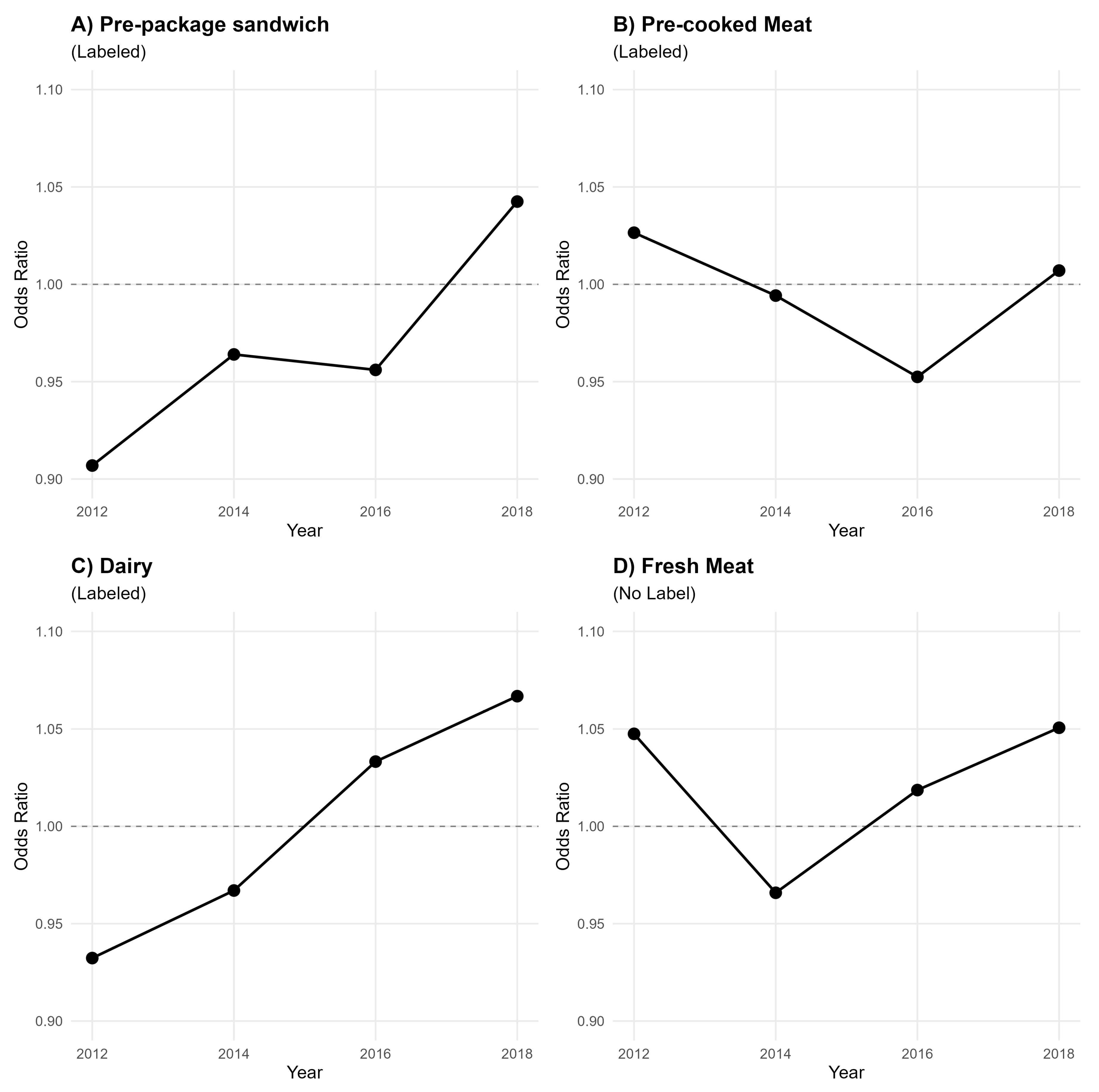

Table 3 and

Figure 3 present the findings derived from the ordinal logistic regressions conducted using non-equivalent dependent variables (NEDVs). Initial analysis revealed a statistically significant association exclusively concerning pre-packaged sandwiches (

). Estimations elucidate a more intricate relationship when considering the interaction between perceived readability and the survey year. Specifically for pre-packaged sandwiches (Panel A), a notable dynamic relationship was discerned. During the baseline year of 2012, a statistically significant inverse relationship was observed (OR = 0.91, 95% CI [0.83, 0.99]), where in each one-unit increment in perceived readability correlated with an approximate 9% reduction in the odds of more frequent consumption. This negative relationship, reflected in the interaction terms, persisted through 2014 (-4%) and 2016 (-5%). This association underwent a transformation over the study period, evidenced by a significant positive interaction term for 2018 (Readability × 2018: OR = 1.15, 95% CI [1.02, 1.29]). Consequently, by 2018, the overall impact of readability had inverted (combined OR = 1.04), manifesting as a 4% increase in the odds of frequent consumption for each one-unit rise in perceived readability.

This dynamic association was not observed across the control outcome categories. Specifically, the analysis for pre-cooked meat (Panel B), dairy (Panel C), and fresh meat (Panel D) revealed no comparable temporal dynamic; neither the main association with readability nor its interactions with the survey year achieved statistical significance. This consistent pattern robustly indicates that the observed dynamic association is not a generalised consequence of label salience but rather an effect specific to the pre-packaged sandwich category. While this dynamic interaction was specific to this category, other significant temporal trends were observed across all models. Specifically, for pre-packaged sandwiches, the odds of frequent consumption in 2018 were reduced by 62% compared to those in 2012. In contrast, the odds of frequent consumption for pre-cooked meat demonstrated a significant elevation in subsequent years, increasing by 87% in 2016 and 73% in 2018 relative to the 2012 baseline. Furthermore, fresh meat consumption exhibited an even more pronounced increase, with the odds of frequent consumption in 2018 exceeding a two-fold rise.

3.4. Health Belief Associations

Table 4 and

Table 5 show the findings from ordinal logistic regressions, stratified by health belief behavioral subgroups. The results confirms that the relationship between perceived MTL print size readability and consumption frequency is significantly influenced by product category, suggesting varied patterns of label engagement.

The analysis stratified by information-seeking behavior highlights a key divergence. Among non-information seekers, a significant negative correlation was observed between perceived readability and the frequency of pre-packaged sandwich consumption (OR = 0.81, 95% CI [0.69, 0.95]). In other words, each one-unit increment in perceived MTL print size readability correlated with an approximate 19% reduction in the odds of more frequent consumption. While the primary association did not achieve significance among information seekers, a statistically significant interaction with the year 2018 was exclusively observed within this group (OR = 1.15, 95% CI [1.01, 1.30]). This indicates that their relationship with readability has evolved, manifesting as a 7% increase in the odds of frequent consumption for each one-unit rise in perceived readability.

For the control pre-cooked meat, readability consistently showed no significant main or interaction effects in either group. This null finding is mirrored in the no-label falsification test, fresh meat. Notably, the dairy control analysis revealed a pattern analogous to that of sandwiches, where a significant main effect of readability was exclusively identified among non-information-seeking participants (OR = 0.65, 95% CI [0.46, 0.92]).

When stratifying by concerns regarding food safety, a comparable pattern was observed. Specifically for pre-packaged sandwiches, both the significant primary association with readability (OR = 0.90, 95% CI [0.82, 0.99]) and the notable interaction effect with the year 2018 (OR = 1.16, 95% CI [1.03, 1.31]) were observed solely among individuals expressing low levels of concern. In this subgroup, a one-unit increment in perceived MTL print size readability initially correlated with an approximate 10% reduction in the odds of more frequent consumption, a trend that subsequently evolved into a 4% increase by 2018. In the control categories of pre-cooked meat and dairy, readability did not emerge as a significant factor for either the high- or low-concern subgroups. Conversely, the no-label fresh meat model unexpectedly revealed a significant positive interaction with the year 2018 specifically within the high-concern group (OR = 1.40, 95% CI [1.08, 1.81]), despite the main effect of readability not reaching statistical significance for either subgroup.

3.5. Sensitivity Analysis

As a robustness check, we reframed the analysis using binary logistic regression, where consumption was classified as either Yes (any frequency) or No (never), while adjusting for the same control variables (see Appendix). The results from this binary approach reveal a consistent directional association for pre-package sandwiches compared to the ordinal model. For this product, a statistically significant negative association emerged suggesting that each one-unit increment in perceived MTL print size readability correlated with an approximate 16% reduction in the odds of being a consumer. The findings for the control outcome categories aligned with those obtained from the primary ordinal model, indicating an absence of a statistically significant association between perceived readability and the propensity for consumption. While this robustness check confirms the product-specific nature of the findings, it is important to note that the binary classification of consumption is a simplification. This approach may mask more subtle relationships by not distinguishing between different levels of consumption frequency, such as monthly versus weekly, which were considered in the primary ordinal analysis.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to address the possibility of reverse causality. Specifically, we modelled readability as the outcome and consumption frequency as the predictor, adjusting for the same covariates (see Appendix). The results indicate that the direct association between these two variables was statistically significant for both pre-packaged sandwiches and pre-cooked meat. This significant reverse association underscores the importance of carefully considering the directional implications within the primary model. While our findings support strong reverse causality, the cross-sectional nature of the data means we cannot definitively establish the direction of the relationship. Future longitudinal studies are needed to clarify these dynamics.

While ready meal constitutes a distinct category within the UK Food and You Survey, its data availability was limited to 2016, thereby precluding the analysis of cross-sectional associations central to this research. For transparency, the ordinal logistic regression model for this specific category was included in the appendix. The resulting positive, non-statistically significant estimates corroborate the findings of our primary model for pre-cooked meat, although caution is required due to the small sample size.

Transportability is part of the external validity checks [

67,

68]. This analysis adjusts study results from a sample to a target population by accounting for differences in baseline characteristic distributions [

69]. We accomplished this by generalizing the UK Food and You findings to the National Diet and Nutritional Survey (NDNS) target population, employing two generalized boosted models (GBM) with distinct sets of covariates. The first model included only demographic and socioeconomic covariates, while the second, which we refer to as the fully adjusted model in our main analysis, encompassed a broader set of variables. To examine the stability of our key findings, we recalculated the transportability weights and re-estimated the transported association for pre-packaged sandwiches under various specifications. This sensitivity analysis confirmed the robustness of the primary models. Specifically, for pre-packaged sandwiches, the significant association with readability remained stable and became more precise after full adjustment. Similarly, the null finding for pre-cooked meat was insensitive to the choice of adjustment variables.

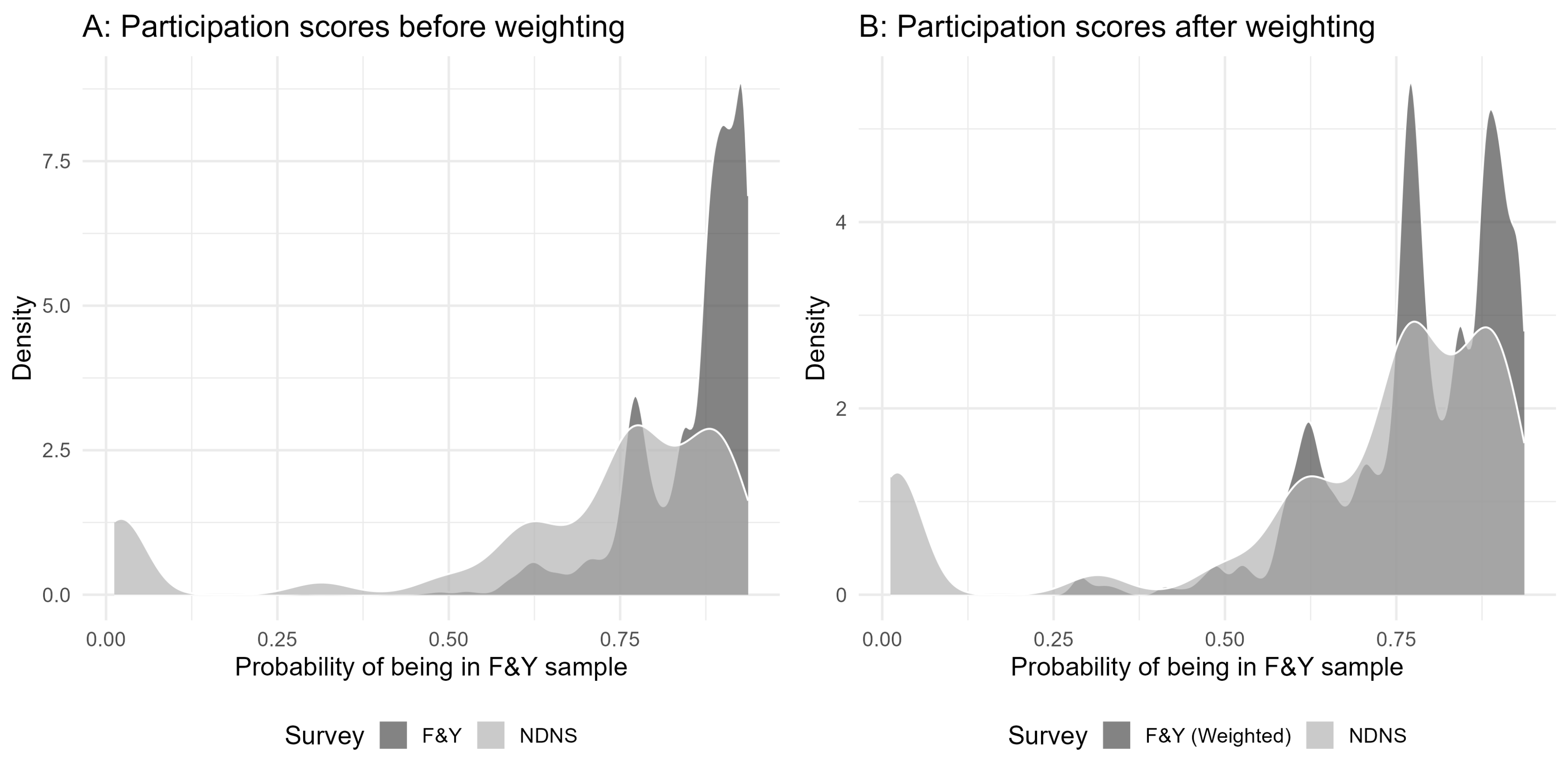

Furthermore, to evaluate how well the transportability weights from our fully adjusted model balanced the covariate distributions, we performed two diagnostic checks. First, we created a table comparing the distributions of the shared covariates between the Food and You and NDNS samples. Second, we plotted the density of the estimated participation scores for both survey samples to visually assess their overlap and the success of the weighting adjustment.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the association between consumers’ perceived readability of MTL print size and the frequency of food consumption within the United Kingdom, using self-reported readability as a proxy for the successful completion of the salience-to-understanding pathway. Strengthened by non-equivalent dependent variables (NEDVs), our findings move beyond a simple product-specific interpretation, revealing a content-specific association. Specifically, we observed a significant and dynamic association between readability and consumption that was exclusive to pre-packaged sandwiches. This effect was absent for our other REM labelled product (pre-cooked meat), our healthy-labelled control (dairy), and the no-label falsification test (fresh meat).

Pre-packaged sandwich consumption patterns strongly support the notion that the salience-to-understanding pathway for food labels is not a universal phenomenon, but is rather content-dependent[

70]. Specifically, in 2012, enhanced readability was linked to a 9% reduction in the odds of frequent consumption, consistent with the proposed warning mechanism. However, while the ongoing reduction persisted in 2014 and 2016, this relationship reversed by 2018, with the interaction term becoming positive and statistically significant. Practically, reducing consumption from weekly (52 sandwiches/year) to monthly (12 sandwiches/year) eliminate approximately 40 sandwiches from an individual’s annual diet. This reduction translates to roughly 16,000 fewer calories per year, a significant amount for both weight management and cardiovascular health [

71]. This central finding was also validated through transportability analysis, confirming its robustness. Moreover, the outcomes observed for the control categories offer crucial corroboration for our hypothesis concerning the absence of this effect in contexts where a warning signal is not implicated. The consistent absence of a significant association for both the healthy-labeled dairy control and the unlabeled fresh meat control lends support to the prediction that, in scenarios where a label serves as a reinforcer instead of a warning, or is entirely absent, perceived readability does not operate as a salient behavioral cue [

45,

72].

The statistically significant interaction between perceived MTL print size readability and survey year, exclusively observed for pre-packaged sandwiches, indicates an evolving association. This reversal in the relationship is interpreted as a reflection of broader transformations within the food environment, rather than being solely attributable to a straightforward consumer learning effect [

16,

24,

46]. As manufacturers adapted to MTL regulations, product reformulations and enhanced marketing strategies may have recontextualized the MTL, shifting its perception from an avoidable option to a marker of a standard convenience item [

73]. This aligns with recent research on REM consumption, which confirms the dominance of new ready meal varieties in the UK market, often featuring claims such as the absence of additives or preservatives, vegetarian/vegan suitability, environmentally friendly packaging, and microwave compatibility [

6,

73]. Consequently, by 2018, a product category already established for its convenience could plausibly be associated with increased consumption, notwithstanding the presence of health-related warnings. The increased consumption may also stem from the dilution of health warnings’ effectiveness due to their widespread presence and sophisticated marketing of convenience foods, potentially desensitizing consumers rather than leading to a complete disregard for health information [

74,

75]. This complex interplay warrants further investigation.

For pre-packaged sandwiches, the results showed that the main effect of readability was significant and negative exclusively for non-information seekers and those with low concern. This supports the hypothesis that content-specific readability acts as a primary behavioral cue for less-engaged consumer groups [

46,

76]. Specifically, each one-unit increment in perceived MTL print size readability was associated with an approximate 19% and 10% reduction in the odds of more frequent consumption for non-information seekers and those with low concern, respectively. Consistent with the primary finding, this association also reversed over time within these segments. For pre-cooked meat and dairy, no significant main or interaction effects were found in almost any subgroup, reinforcing their null status. The fresh meat model was also largely null, with the exception of an unexpected positive 2018 interaction for the high-concern group. Despite this anomaly, the overwhelming pattern across subgroups and NEDVs is one of null effects, reinforcing the uniqueness of the sandwich findings. This pattern observed suggests that the efficacy of the MTL is more dependent on consumer engagement and beliefs than on the mere dissemination of information, as postulated by nudging theories [

27,

72,

77,

78,

79].

The product-specific nature of our findings is further explained by the distinct demographic profiles of the consumer bases for each food category. The profile of the high-frequency pre-package sandwich consumer aligns with a convenience-driven mindset. This group is markedly female (62.4%), younger (with the 18-24 and 25-34 age brackets making up over 43.7% of weekly consumers), and has less shopping responsibility (56.6%). These consumer trends align with the broader trends in ultra-processed food consumption in the UK [

80,

81]. This contrasts with the consumer base for pre-cooked meat, which is older and more balanced. Our NEDVs fit this logic highlighting that the fresh meat consumer profile closely mirrors that of pre-cooked meat, suggesting a similar motivation. The dairy consumer base is nearly universal, representing a demographically balanced staple, unlike the specific, convenience-oriented profile of the sandwich consumer [

1].

The present study corroborates that consumers’ subjective understanding of labels is not uniform, but rather exhibits systematic variations across distinct consumer profiles. Descriptive analysis indicated that younger consumer subgroups (16–24 years) consistently reported the highest perceived ease of reading, whereas middle-aged (45–54 years) demographics encountered the greatest challenges. Concurrently, individuals from higher-income brackets and those without dependent children at home consistently reported superior readability perceptions. These systematic perceptual disparities underscore the inadequacy of a standardized, one-size-fits-all approach to food labelling, given that the foundational stage of the salience-to-understanding pathway is not uniformly experienced across the consumer populace. Although a significant portion of extant research on food labels presupposes a baseline level of readability [

25,

26], our findings emphasize that the perception of print size constitutes a critically heterogeneous factor. This observation aligns with evidence from other health-related contexts, wherein informational clarity serves as a fundamental prerequisite for comprehension [

37,

38].

This research significantly contributes to food policy by addressing the well-documented discrepancy between consumers’ reported engagement with and comprehension of MTL labels and the limited influence these labels have on purchasing behaviors [

17,

18,

19,

35]. Our findings indicate that the association between label readability and consumer choice is contingent not only on the product itself but also on the specific content of the label. For instance, an enlarged font size might exert a more pronounced effect on the purchasing decisions for an ambiguous convenience item featuring a red warning, yet it may have a negligible impact on products perceived as healthy or those constituting traditional meal components. Consequently, policy interventions should not presuppose a uniform effect across all contexts. While increasing print size could be an effective strategy, our results suggest that its efficacy is moderated by both the message’s content and the particular product category to which it is applied.

Limitations

This study’s primary strength lies in its use of a large, nationally representative dataset to examine the real-world association between label readability and consumer choice, a context that distinguishes our approach from research that relies predominantly on experimental designs. By analyzing observational data spanning the 2013 MTL redesign (2012-2018), we were able to capture cross-sectional trends. This temporal perspective was crucial for uncovering our key findings.

Methodologically, the study makes several contributions. The use of proportional odds ordinal logistic regression provided the flexibility to model the nuanced nature of consumption frequency without imposing restrictive assumptions. In addition, our study’s primary contribution is the formal transportability analysis, which moves beyond a simple qualitative statement of limitation to provide robust, model-based evidence for the external validity of our findings.

This investigation offers valuable insights into real-world phenomena; however, several limitations warrant consideration. Primarily, the data structure inherently constrains the ability to draw definitive causal inferences. Given the simultaneous nationwide implementation of the MTL policy in the UK, it was not feasible to distinguish distinct treatment groups, thereby impeding robust causal identification. While tests for reverse causality lent support to a reverse association, the study is confined to reporting statistical associations rather than establishing causal effects.

The observed reversal in the association for pre-package sandwiches may stem from concurrent, unmeasured events, such as broader public health campaigns or shifts in product marketing, instead of solely reflecting individual-level adaptation to the MTL. Consequently, while the repeated cross-sectional analysis offers a strength, population-level trends warrant cautious interpretation given the risk of an ecological fallacy.

Second, there are limitations related to our key measures. Our central variable, perceived readability, is a self-reported proxy for the salience-to-understanding pathway, not a direct objective measure of comprehension. Similarly, the consumption data is self-reported and may be subject to recall or social desirability biases. We sought to mitigate this by cross-validating our consumption trends against the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey, which showed comparable patterns and lends external validity to our findings. Finally, while our study highlights the crucial role of print size, a limitation is that our measure of perceived readability cannot be fully disentangled from other interacting design elements on a package, such as color contrast, layout, and font type, which also contribute to a label’s overall salience and ease of processing.

Third, the dataset presented statistical challenges, notably a significant portion of missing income data. As this exceeded 20% of the sample, imputation was not used, which consequently reduced the statistical power in our models. Furthermore, due to inconsistencies in how consumption frequency was measured across different food categories in the UK Food and You Survey, we could not extend this comparative analysis to other types of food products.