1. Introduction

Human schistosomiasis is a tropical parasitic disease caused by Schistosoma parasites, affecting 250 million people globally [

1]. Niclosamide is the only molluscicide approved by the World Health Organization (WHO) for controlling

Oncomelania snails in schistosomiasis prevention. Due to its lipophilic properties, niclosamide accumulates in aquatic organisms and causes toxicity to non-target freshwater species, particularly mollusks [

2,

3]. Research demonstrates that niclosamide disrupts endocrine function, leading to structural organ damage and metabolic dysregulation that impair growth and development in diverse species [

4,

5,

6]. Notable effects include embryonic developmental disorders in zebrafish due to disruptions in lipid and steroid metabolism [

7] and severe liver damage in turtles resulting from impaired immune and metabolic processes [

8]. In contrast, the mechanisms of niclosamide accumulation and its toxic effects on mollusks remain poorly understood.

The digestive gland is a multifunctional organ central for nutrient metabolism and absorption [

9] and plays a crucial role in stress responses in mollusks [

10]. It also serves as the primary site for the bioaccumulation and toxic effects of lipophilic pollutants [

11]. For instance, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) exhibit bioconcentration factors (BCFs) in the digestive glands of the bivalve

Scapharca subcrenata ranging from 4.16 to 254.2 mL/g [

12]. Such accumulation triggers histopathological changes, including vacuolization, secretory cell necrosis, and degeneration of digestive tubules [

13,

14]. These changes impair metabolic functions [

15] and induce structural damage in associated organs such as the foot [

16].

As the primary locomotory organ of mollusks, the foot is continuously exposed to environmental pollutants, making it a direct target for pollutant toxicity [

17]. Pollutant exposure further triggers metabolic dysfunctions, which exacerbate tissue damage in this organ [

18,

19]. For example, perfluorooctanoic acid disrupts muscle fiber structure in mussel feet by impairing myofibrillar protein metabolism, thereby reducing their adhesive function [

20].

We selected

Cipangopaludina cahayensis as the study organism due to its prevalence in schistosomiasis-endemic regions of East Asia [

21]. Considering the lipophilic enrichment propensity of niclosamide, its documented toxicity to mollusks, and the functional roles of the digestive glands (metabolic core) and foot (direct exposure site) in

C. cahayensis, we hypothesize that niclosamide exposure leads to tissue-specific bioaccumulation in these organs. This accumulation is expected to cause structural damage and metabolic dysfunction. The aim of this study is to investigate the effects of 60-day niclosamide exposure at the environmentally relevant concentrations on

C. cahayensis by (1) quantifying niclosamide bioaccumulation and nutritional component alterations in digestive glands and foot; (2) characterizing histopathological lesions and inflammatory responses; and (3) exploring the toxic cascade effect between the digestive glands and foot. These findings will address the research gap regarding niclosamide bioaccumulation and damage mechanisms in mollusks, providing foundational data for establishing environmental safety thresholds for niclosamide and guiding its science-based application.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mesocosm Setup

A mesocosm experiment was conducted at the Hsen-Hsu Garden, Nanchang University, from late July to late September 2023. Twenty-five cylindrical polyvinyl chloride (PVC) mesocosms (150 cm diameter × 160 cm depth) were established (

Figure S1), each containing 2,500 L of prefiltered (100-μm mesh) pond water sourced from an adjacent natural wetland. Benthic sediment conditions were simulated using twelve PVC flowerpots (22 cm diameter) per mesocosm, filled with 15 cm of homogenized sediment collected from Poyang Lake in May 2023. During the 30-day equilibration phase, mesocosms were hydraulically connected via PVC pipes, with one-third of the water volume exchanged between adjacent mesocosms weekly to ensure homogeneous water quality while maintaining independent exposure systems. The initial TN in water was 0.49 ± 0.11 mg/L; TP was 0.02 ± 0.01 mg/L.

Mesocosms were randomly allocated to five treatments: one control and four niclosamide exposure groups with target concentrations of 7.5, 15.0, 30.0, and 50.0 μg/L (n = 5 per treatment). These concentrations were chosen to represent and exceed environmentally relevant levels, based on reported niclosamide concentrations of 10–38 μg/L in surface waters of Poyang Lake [

22].

Niclosamide (≥98% purity; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used as the test compound. Given the photolytic degradation of niclosamide in aquatic systems, target concentrations in the mesocosms were maintained by replenishing niclosamide stock solutions every two days. The stock solutions were freshly prepared by dissolving niclosamide in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). An equal volume of DMSO added to the control group, and the final DMSO concentration was strictly controlled at ≤0.05% (v/v) across all control and treatment groups. Dosing solutions were gently poured onto the water surface of each mesocosm and immediately stirred to ensure homogeneous mixing. Water levels were monitored daily, and dechlorinated tap water was added when evaporation exceeded 5 cm to minimize concentration fluctuations.

Water samples were collected 4–10 hours pre-dosing and 1-hour post-dosing. Following collection, 100 mL aliquots were stored in HDPE bottles, with 1 mL subsamples transferred to amber HPLC vials and flash-frozen at −20°C. Sample processing included nitrogen-assisted drying at 45°C, reconstitution in acetonitrile/water (1:10, v/v), C18 solid-phase extraction purification, and 0.22-μm nylon membrane filtration. Niclosamide quantification was performed using a Waters HPLC system equipped with a C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) under the following conditions: column temperature 25°C, flow rate 1.0 mL/min, injection volume 10 μL, detection wavelength 236 nm, and a run time of 25 minutes. The limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ) for niclosamide were 1 ng/mL and 3 ng/mL, respectively. Values below LOD were designated as ND. Throughout the exposure period, water monitoring confirmed the following time-weighted mean niclosamide concentrations (±SD) in treatment groups, 7.5 μg/L target was 6.6 ± 1.31 μg/L; 15.0 μg/L target was 11.76 ± 3.59 μg/L; 30.0 μg/L target was 26.20 ± 5.21 μg/L; 50.0 μg/L target was 43.40 ± 7.81 μg/L (Complete temporal profiles in

Figure S2).

2.2. C. cahayensis Collection and Analysis

C. cahayensis were sourced from Jiangxi Agricultural Development Group Co., Ltd. (Jiangxi, China). Upon arrival at the laboratory, individuals were acclimatized in dechlorinated tap water for 14 days under controlled conditions (temperature: 22 ± 1°C; photoperiod: 12-h light/12-h dark). Specimens selected for experimentation exhibited mean morphological parameters of shell height 39.4 ± 0.4 mm, shell width 31.7 ± 0.4 mm, and body mass 15.5 ± 1.5 g (mean ± SD, n = 30). For the 60-day chronic exposure trial, thirty individuals were randomly introduced into each mesocosm.

Upon termination of the mesocosm exposure, 15 C. cahayensis individuals per treatment group were anesthetized with MS-222. Digestive glands and foot tissues were then aseptically dissected on ice-chilled trays. Samples from five individuals were allocated for niclosamide bioaccumulation analysis (flash-frozen in liquid N₂ and stored at −80°C), five for nutritional component analysis (similarly flash-frozen and cryopreserved), and five for histopathological analysis (fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin).

For niclosamide bioaccumulation analysis, digestive glands and foot tissues were weighed and homogenized in 10 mL of acetonitrile. Homogenates were subjected to ultrasonication (10 min), centrifuged (10,000 × g, 5 min, 4°C), and 500 μL of supernatant was analyzed for niclosamide via HPLC using the method described in the mesocosm setup.

For nutritional component analysis, protein content was determined by the Kjeldahl method, using a 6.25 nitrogen-to-protein conversion factor. Lipid content was measured using the chloroform-methanol solution method [

23], and glycogen content was assayed using a commercial detection kit (Cat. A048-2-1, Nanjing Jiancheng) following manufacturer specifications.

For histopathological analysis, foot and digestive glands tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 72h with daily fixative replacement. Fixed specimens underwent dehydration through a graded ethanol series (75%, 85%, 95%, 100%), clearing in xylene, and paraffin embedding. Serial sections with a thickness of 5 μm were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and mounted with neutral balsam. For each snail, five slides per tissue with six sections per slide were prepared, yielding 150 sections per tissue type per experimental group. All sections were imaged at 400× magnification using an Olympus CX41 microscope. A total of 150 images per group (30 images/snail) were acquired and analyzed.

Digestive tubules were categorized into three functional phases, holding, adsorption, and atrophy [

24]. The proportional distribution of these phases was quantified by counting 12 randomly selected digestive tubules per histological section. Hemocytic infiltration and hemocytic nodule frequencies in digestive glands were assessed through systematic visual counting across five non-overlapping fields per slide. Foot tissue morphometrics, including fold depth, vacuole number density, vacuole area fraction, muscle fiber diameter, and muscle fiber numerical density, were analyzed using ImageJ software (v.1.53a). All histomorphometric evaluations were conducted with 150 replicates per treatment group.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The bioconcentration factor (BCF) was calculated as:

where CT is niclosamide concentration in tissues (g/kg wet weight) and CW is dissolved-phase concentration in water (g/L), with the resulting unit being L/kg [

25].

Foot vacuole numerical density (FVN) was defined as:

where Nv is vacuole count within the measurement area and A is the standardized sampling area (mm²), expressed as counts/mm².

Foot vacuole area fraction (FVA) was calculated as:

where Av is the cumulative vacuole area (mm²) and A is the sampling area (mm²).

Muscle fiber density (MFN) was determined as:

where Nm is muscle fiber count and A is the sampling area (mm²), with units of fibers/mm².

Dose-response relationships between niclosamide exposure concentrations and histopathological indices were evaluated by constructing independent concentration-response regression models. To enable cross-metric comparisons, all data were standardized to the 0-1 range by (x-xmin)/(xmax-xmin). Pearson correlation analysis was used to examine relationships between niclosamide bioaccumulation, nutritional components, and histopathological parameters.

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Since the data failed the Shapiro-Wilk normality test (p < 0.05), non-parametric tests were employed. All statistical analyses were performed in R (v.4.3.1). Specifically, Pearson correlation analysis and dose-response relationship modeling were performed using the ‘Hmisc’ package [

26] and ‘stats’ package [

27] respectively, while data visualizations were generated using the ‘ggplot2’ package [

28].

3. Results

3.1. Niclosamide Bioaccumulation and Nutrient Content Changes in C. cahayensis

Following 60-day exposure, niclosamide accumulated in the digestive glands and foot of

C. cahayensis. At concentrations ≥15 µg/L, accumulation levels in digestive glands were significantly higher than in the foot (p < 0.05;

Figure 1A). Dose-dependent accumulation was observed, with niclosamide levels reaching 0.61 ± 0.02 µg/g in digestive glands and 0.38 ± 0.02 µg/g in foot tissues at a 50 µg/L exposure dose. Bioconcentration factors (BCFs) further highlighted tissue specificity, with BCFs ranging from 12.1 to 35.2 L/kg in the digestive glands and 7.6 to 21.6 L/kg in the foot tissues.

Glycogen, lipid, and protein contents were reduced in both the digestive glands and foot tissues across all niclosamide exposure groups (

Figure 1B-D). At the 50 μg/L exposure level, lipid concentrations in digestive glands were 28.22 ± 7.00 mg/g, a 60.56% reduction compared to controls; glycogen levels decreased to 8.88 ± 2.51 mg/g, a 59.25% reduction; and protein content dropped to 26.64 ± 5.20 mg/g, a 79.23% reduction. These changes collectively indicate metabolic disruption in digestive glands.

3.2. Structural and functional impairment of digestive glands induced by niclosamide

The control group exhibited intact histological architecture of digestive glands, characterized by discrete tubular structures separated by connective tissue and hemolymph sinuses (

Figure 2). The tubule epithelium was predominantly composed of digestive and secretory cells. Histopathological analysis revealed three distinct functional phases, each defined by characteristic histological changes. The holding phase displayed plump digestive cells; the absorptive phase showed irregular luminal contours with hypertrophied epithelial layers; and the atrophic phase demonstrated luminal dilation accompanied by cellular degeneration [

24].

Quantitative histology revealed that niclosamide treatment reduced the proportion of holding phases digestive tubules while increasing atrophic phases tubules (

Figure 2F). Control samples displayed minimal inflammatory activity, whereas niclosamide exposed groups exhibited elevated hemocyte infiltration and nodular formation (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

3.3. Structural and Metabolic Pathologies in Foot Induced by Niclosamide

In both control and niclosamide-exposed groups, the foot morphology of

C. cahayensis exhibited epithelial and muscular tissues. Control samples exhibited densely arranged tissues with shallow, smooth epithelial folds (

Figure 4A). Niclosamide treatment significantly increased the depth of epithelial folds (

Figure 4). The depth increased from 54.99 ± 17.36 µm in the control group to 114.45 ± 25.85 µm in the 50 µg/L group (

Figure 5A). Undifferentiated epithelial cells appeared in the 7.5 µg/L exposure group (

Figure 5B). Vacuolation was prominent in niclosamide-treated groups. The vacuolar area fraction also increased from 0.53 ± 0.17% in controls to 7.99 ± 2.39% in the 50 µg/L group (

Figure 5D).

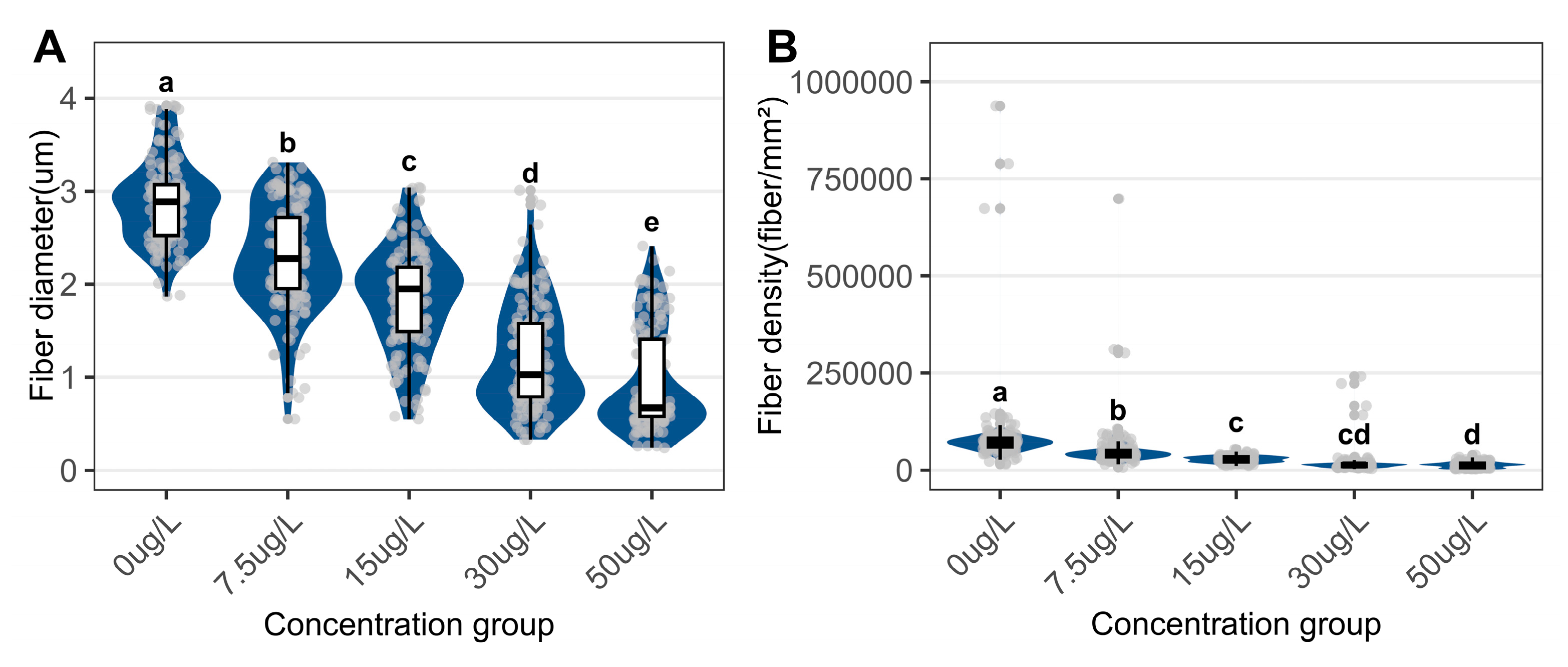

Muscle fibers exposed to niclosamide exhibited significant atrophy and structural distortion compared with controls (

Figure 6). In the control group, muscle fibers maintained a mean diameter of 2.88 ± 0.44 μm (

Figure 7A) and a density of 86,243.74 ± 10,539.49 fibers/mm² (

Figure 7B). Exposure to 50 μg/L niclosamide induced severe morphological changes, reducing diameters to 0.96 ± 0.55 μm and densities to 13,602.24 ± 7,222.81 fibers/mm².

3.4. Relationships Between Niclosamide Exposure, Bioaccumulation, Nutrient Components, and Pathological Changes in C. cahayensis

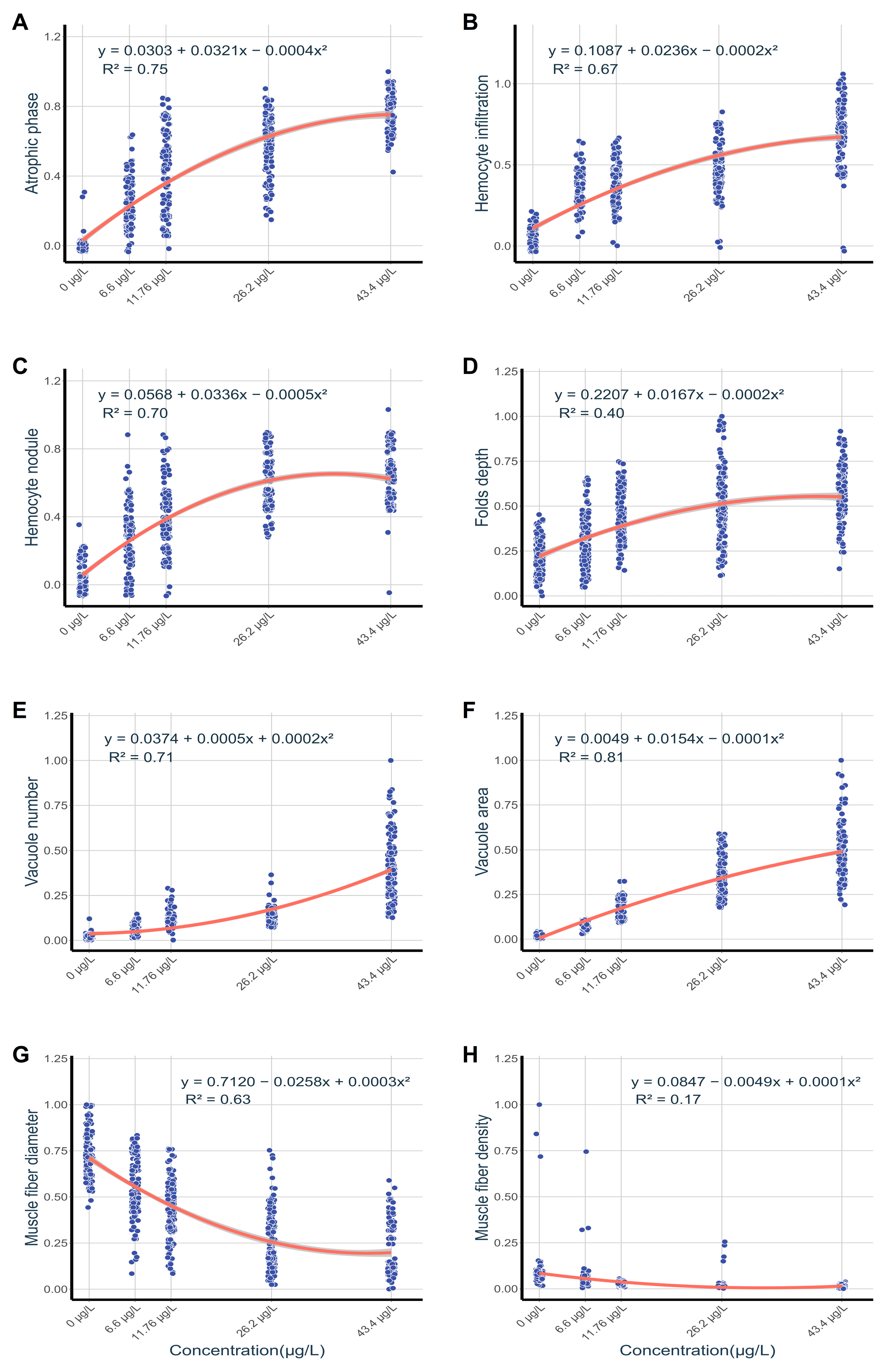

Normalized pathological indices exhibited concentration-dependent correlations as revealed by quadratic regression analysis (

Figure 8). Vacuolar area in foot tissues exhibited a strong predictive relationship with exposure concentrations (R² = 0.81;

Figure 8F), while muscle fiber density displayed negligible predictive value (R² = 0.17;

Figure 8H). Digestive gland lesions were strongly associated with exposure levels, particularly in atrophied digestive tubules (R² = 0.75;

Figure 8A) and hemocyte nodules (R² = 0.70;

Figure 8C).

Pearson correlation analysis revealed strong negative correlations between histopathological alterations and nutrient components in digestive glands (r = -0.71 to -0.85; Fig. 9). Nutrient compositions of digestive glands showed statistically significant positive associations with foot tissue components, most notably a strong correlation in protein content (r = 0.96). Foot tissue nutrient levels also showed strong positive correlations with histopathological indices (r = 0.72-0.89).

Figure 9.

Pearson correlation matrix of bioaccumulation, nutrient components, and histopathological parameters in digestive glands and foot tissues. Digestive gland parameters include niclosamide bioconcentration (HBI), glycogen (HGL), lipid (HLI), protein (HPR), atrophic phase proportion (HAP), hemocyte infiltration (HHI), and hemocyte nodules (HHN). Foot parameters include niclosamide bioconcentration (FBI), glycogen (FGL), lipid (FLI), protein (FPR), fold depth (FF), vacuole numerical density (FVN), vacuolar area fraction (FVA), muscle fiber diameter (MFD), and muscle fiber density (MFN).

Figure 9.

Pearson correlation matrix of bioaccumulation, nutrient components, and histopathological parameters in digestive glands and foot tissues. Digestive gland parameters include niclosamide bioconcentration (HBI), glycogen (HGL), lipid (HLI), protein (HPR), atrophic phase proportion (HAP), hemocyte infiltration (HHI), and hemocyte nodules (HHN). Foot parameters include niclosamide bioconcentration (FBI), glycogen (FGL), lipid (FLI), protein (FPR), fold depth (FF), vacuole numerical density (FVN), vacuolar area fraction (FVA), muscle fiber diameter (MFD), and muscle fiber density (MFN).

4. Discussion

Niclosamide is the only molluscicide approved by the WHO for controlling

Oncomelania snails in schistosomiasis prevention [

4]. However, its widespread use raises ecological concerns due to its accumulation in aquatic organisms and demonstrated toxicity toward non-target freshwater species [

2,

5]. Nevertheless, its accumulation patterns and toxic mechanisms in mollusks remain poorly understood. This study aimed to elucidate the toxicological mechanisms of niclosamide in the mud snail (

C. cathayensis) under environmentally relevant exposure levels through integrated biochemical and histopathological analyses.

4.1. Bioaccumulation of Niclosamide in C. cathayensis

In this study, we demonstrate that the digestive glands of

C. cathayensis serve as the primary reservoir for niclosamide accumulation. Niclosamide’s hydrophobicity, resulting from its benzene ring and alkyl chain structures, confers lipophilic properties critical for its uptake mechanisms [

29]. Lipophilic xenobiotics penetrate mollusk epidermal barriers via passive diffusion and undergo intestinal absorption, leading to preferential accumulation in lipid-rich tissues such as digestive glands [

3,

30]. This pattern is consistent with previous findings reporting primary niclosamide enrichment in the livers of amphibians and fish [

8,

31].

Under controlled exposure to 50 μg/L niclosamide, we determined that the BCF in digestive glands of

C. cathayensis was 35.2 L/kg. This value is higher than the 2.4 L/kg detected in the livers of

Pelodiscus sinensis (Chinese soft-shelled turtle) under the same exposure conditions [

8], but a little lower than the 37.2 L/kg reported in the liver tissues of

Mylopharyngodon piceus (black carp) [

31]. This discrepancy may reflect differences in exposure duration and metabolic efficiency between species, given that the amphibians in Xiang's study could temporarily escape the niclosamide-contaminated environment. This raises considerable ecological risks, particularly for species whose habitats overlap with polluted waterways over the long term. Notably, the large accumulation of niclosamide in the digestive glands of

C. cathayensis demonstrates their vulnerability to chronic exposure at environmentally relevant concentrations [

32].

4.2. Structural and Functional Impairment of Digestive Glands Induced by Niclosamide

Our findings reveal that niclosamide exposure induces severe pathological alterations in the digestive glands of

C. cathayensis, including atrophy of digestive tubules, hemocyte infiltration, and nodular formations. The salicylanilide structure of niclosamide promotes its binding to nitric oxide synthase (NOS) via hydrophobic interactions between its benzene ring and hydrogen bonding involving the amide group [

33]. This structural interaction suppresses NOS enzymatic activity, leading to excessive release of pro-inflammatory mediators from hemocytes [

34,

35]. The resultant inflammatory manifests as histologically observable hemocyte infiltration and nodular in digestive gland tissues (

Figure 2). These findings corroborate previous reports of inflammatory responses in the livers of

Pelodiscus sinensis and intestinal in the of nodulation

Mylopharyngodon piceus [

8,

31].

Histological analysis of niclosamide-treated specimens revealed features of tubular atrophy, including reduced digestive cell volume and disrupted epithelial architecture (

Figure 2). These morphological changes directly impair nutrient digestion and absorption efficiency [

24], as evidenced by decreased nutrient content in experimental data (

Figure 1B-D). As the primary metabolic organ in mollusks, digestive glands regulate glucose homeostasis through glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis to meet basal metabolic demands [

36]. Reduced nutrient processing capacity exacerbates the depletion of stored nutrients, making a vicious cycle in energy metabolism [

37]. Collectively, these findings indicate that niclosamide not only induces structural degeneration but also triggers functional failure in the digestive glands of

C. cathayensis.

4.3. Structural and Metabolic Pathologies in the Foot Induced by Niclosamide

Compared to the control group, specimens exposed to niclosamide exhibited marked pathological changes in foot tissue, including vacuolar expansion, deepening of epithelial folds, and muscle fiber atrophy. Vacuolar expansion is proposed to result from hypersecretory responses that disrupt intracellular metabolic homeostasis [

38]. This response serves as a protective mechanism conserved across mollusks exposed to pollutants [

39]. These findings are consistent with observations in

Monacha cartusiana following exposure to Bacillus thuringiensis, where similar vacuole enlargement was noted [

40]. Quadratic regression analysis revealed a significant positive correlation between niclosamide concentration and vacuolar area expansion in foot tissue (r² = 0.81;

Figure 8), further supporting the role of hypersecretion.

In addition to structural changes, niclosamide-induced oxidative stress promotes protein oxidation and muscle fiber denaturation in freshwater organisms [

41]. Nutritional coupling between foot tissue and digestive glands was evident through significant positive correlations (r ≥ 0.89) between nutrient levels in these tissues, alongside inverse relationships between foot nutrient concentrations and muscle atrophy severity (r ≤ -0.74; Fig. 9). Reduced digestive gland function impairs nutrient synthesis and transport, depleting nutrients in dependent tissues such as the foot [

37,

42]. Studies on terrestrial gastropods have shown that biopesticide-induced digestive gland damage disrupts protein supply to muscles, exacerbating atrophy [

40]. Niclosamide triggers proteolytic imbalance by disrupting the equilibrium between protein synthesis and degradation in muscle cells [

43]. Moreover, glycogen and lipid depletion reduces ATP production, further exacerbating locomotor dysfunction [

44]. Collectively, niclosamide disrupts foot structure and function by secretory dysregulation, oxidative damage, and proteolytic imbalance [

42,

45]. Simultaneous impairment of digestive gland metabolism exacerbates tissue damage by limiting nutrient availability.

4.4. Ecological Impacts of Niclosamide Exposure

Niclosamide induced structural damage and functional disorders in the digestive glands and foot muscles of

C. cathayensis, directly compromising their survival, growth, and reproductive capacities [

46]. These physiological disruptions increase vulnerability to predation and decrease foraging efficiency, ultimately destabilizing population dynamics across trophic levels [

47]. Beyond mollusks, niclosamide exhibits broad-spectrum ecotoxicity, inducing significant growth inhibition and acute lethality in non-target aquatic organisms such as fish, crustaceans, and amphibians [

8,

29]. Even at low concentrations, its bioaccumulation potential enables biomagnification through food webs [

17]. Chronic exposure exacerbates these effects by impairing ecosystem resilience and permanently damaging core functions like nutrient cycling and energy flow [

29,

48].

As the primary agent for schistosomiasis control, niclosamide remains indispensable in Asia, Latin America, and Africa [

17,

49]. Field data indicate that niclosamide contaminates 95% of surface water samples in the Yangtze River Basin [

50], and its chemical stability renders conventional drinking water treatment processes ineffective for its removal [

47]. Most nations currently lack enforceable regulations to control emissions, while only the United States enforces a surface water limit of 50 μg/L [

51]. To balance public health needs with environmental protection, elucidating niclosamide’s toxic mechanisms is crucial. This foundational research will inform evidence-based strategies for establishing ecologically sound safety thresholds and optimizing schistosomiasis vector-control protocols [

52].

5. Conclusions

Niclosamide bioaccumulation and its associated post-exposure effects were assessed in C. cathayensis, with a focus on histopathological damage and alterations in tissue nutrient levels. After 60 days of exposure, niclosamide accumulated in both the foot and digestive glands. Significant histopathological damage was induced in these organs, accompanied by reduced glycogen, lipid, and protein concentrations. The results also revealed impaired locomotor function in the foot and metabolic disruption in the digestive glands. Persistent niclosamide exposure destabilized molluscan trophic-level population dynamics, ultimately triggering multifaceted ecological disturbances, including a decline in ecosystem resilience and disruption of key ecological functions. These findings provide essential data for the ecological risk assessment of niclosamide in natural aquatic ecosystems. Future research should investigate niclosamide toxicity across additional native species to evaluate potential ecosystem-level cascading effects, thereby supporting the development of evidence-based environmental safety standards.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Experiment mesocosm; Figure S2: Temporal trends of measured NIC concentrations for mesocosm water across all treatment groups during the experimental period. Data are presented as means ± SD (n = 5).

Author Contributions

Y.Z., conceptualization, investigation, and writing—original draft; Y.L., review, editing and funding acquisition; Q.C., review and editing; J.Y., review and editing; T.W., review; S.X., review; G.G., funding acquisition, review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant numbers: 3 32360285 and 32260290.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All original data and materials presented in this study are included in the article and

supplementary files. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Qingxin Li, Tianhong Tu and Fumao Zhang for their valuable support in this research. The authors have reviewed and edited the manuscript and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tabo, Z.; Wangalwa, R.; Rwibutso, M.; Breuer, L.; Albrecht, C. Future climate and demographic changes will almost double the risk of schistosomiasis transmission in the Lake Victoria Basin. One Health. 2025, 21, 101148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.C.; Paumgartten, F.J.R. Toxicity of Euphorbia milli latex and niclosamide to snails and nontarget aquatic species. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2000, 46, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumagai, T.; Miyamoto, M.; Koseki, Y.; Imai, Y.; Ishino, T. Development of a spirulina feed effective only for the two larval stages of Schistosoma mansoni, not the intermediate host mollusc. Trop. Med. Health. 2025, 53, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckalew, A.R.; Wang, J.; Murr, A.S.; Deisenroth, C.; Stewart, W.M.; Stoker, T.E.; Laws, S.C. Evaluation of potential sodium-iodide symporter (NIS) inhibitors using a secondary Fischer rat thyroid follicular cell (FRTL-5) radioactive iodide uptake (RAIU) assay. Arch Toxicol. 2020, 94, 873–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.L.; Yang, S.Y.; Zhu, B.R.; Zhang, M.Y.; Zheng, N.; Hua, J.H.; Li, R.W.; Han, J.; Yang, L.H.; Zhu, B.S. Effects of environmentally relevant concentrations of niclosamide on lipid metabolism and steroid hormone synthesis in adult female zebrafish. Sci. Total. Environ. 2024, 910, 168737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waye, A.A.; Ticiani, E.; Sharmin, Z.; Silos, V.P.; Perera, T.; Tu, A.; Buhimschi, I.A.; Murga-Zamalloa, C.A.; Hu, Y.S.; Veiga-Lopez, A. Reduced bioenergetics and mitochondrial fragmentation in human primary cytotrophoblasts induced by an EGFR-targeting chemical mixture. Chemosphere. 2024, 364, 143301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.R.; He, W.; Yang, F.; Chen, L.G. High-throughput transcriptome sequencing reveals the developmental toxicity mechanisms of niclosamide in zebrafish embryo. Chemosphere. 2020, 244, 125468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, J.; Wu, H.; Gao, J.W.; Jiang, W.M.; Tian, X.; Xie, Z.G.; Zhang, T.; Feng, J.; Song, R. Niclosamide exposure disrupts antioxidant defense, histology, and the liver and gut transcriptome of Chinese soft-shelled turtle (Pelodiscus sinensis). Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2023, 260, 115081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo-da-Cunha, A. Structure and function of the digestive system in molluscs. Cell Tissue Res. 2019, 377, 475–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.P.; Huang, Y.T.; Lu, Z.H.; Ma, Y.Q.; Ran, X.; Yan, X.; Zhang, M.; Qiu, X.Y.; Luo, L.Y.; Yue, G.Z. Sublethal effects of niclosamide on the aquatic snail Pomacea canaliculata. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2023, 259, 115064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroudi, F.; Al Alam, J.; Fajloun, Z.; Millet, M. Snail as sentinel organism for monitoring the environmental pollution; a review. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 113, 106240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakhova, L.; Gostyukhina, O.; Andreeva, A.; Voitsekhovskaia, V. Accumulation of polychlorinated biphenyls and their effects on antioxidant enzyme activities in tissues of the Ark Shell (Anadara kagoshimensis). Int. J. Environ. Res. 2024, 18, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shenawy, N.S.; Moawad, T.I.S.; Mohallal, M.E.; Abdel-Nabi, I.M.; Taha, I.A. Histopathologic biomarker response of clam, Ruditapes decussates, to organophosphorous pesticides reldan and roundup: A Laboratory Study. Ocean Sci. J. 2009, 44, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stara, A.; Pagano, M.; Capillo, G.; Fabrello, J.; Sandova, M.; Albano, M.; Zuskova, E.; Velisek, J.; Matozzo, V.; Faggio, C. Acute effects of neonicotinoid insecticides on Mytilus galloprovincialis: A case study with the active compound thiacloprid and the commercial formulation calypso 480 SC. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2020, 203, 110980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uluturhan, E.; Darilmaz, E.; Kontas, A.; Bilgin, M.; Alyuruk, H.; Altay, O.; Sevgi, S. Seasonal variations of multi-biomarker responses to metals and pesticides pollution in M. galloprovincialis and T. decussatus from Homa Lagoon, Eastern Aegean Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 141, 176–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederick, A.R.; Heras, J.; Friedman, C.S.; German, D.P. Withering syndrome induced gene expression changes and a de-novo transcriptome for the Pinto abalone, Haliotis kamtschatkana. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D-Genomics. Proteomics. 2022, 41, 100930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yuan, XP.; He, Y.; Gao, J.W.; Xie, M.; Xie, Z.G.; Song, R.; Ou, D.S. Niclosamide subacute exposure alters the immune response and microbiota of the gill and gut in black carp larvae, Mylopharyngodon piceus. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2024, 279, 116512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd Elkader, H.T.A.; Al-Shami, A.S. Microanatomy and behaviour of the date mussel's adductor and foot muscles after chronic exposure to bisphenol A, with inhibition of ATPase enzyme activities and DNA damage. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C-Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 271, 109684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canli, E.G.; Baykose, A.; Uslu, L.H.; Canli, M. Changes in energy reserves and responses of some biomarkers in freshwater mussels exposed to metal-oxide nanoparticles. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 98, 104077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.Y.; Shang, Y.Y.; Chen, H.D.; Khadka, K.; Pan, Y.T.; Hu, M.H.; Wang, Y.J. Perfluorooctanoate and nano titanium dioxide impair the byssus performance of the mussel Mytilus coruscus. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 469, 134062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.F.; Du, L.N.; Li, Z.Q.; Chen, X.Y.; Yang, J.X. Morphological analysis of the Chinese Cipangopaludina species (Gastropoda; Caenogastropoda: Viviparidae). Zool. Res. 2014, 35, 510–27, (retrieved from Web of Science Core Collection). [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.G.; Zhen, J.H.; Quan, S.Q.; Liu, M.; Liu, L. Risk assessment for niclosamide residues in water and sediments from Nan Ji Shan island within Poyang Lake region, China. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 721, 608–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, M.C. Lipid extraction from channel catfish muscle-comparison of solvent systems. J. Food Sci. 1993, 58, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.C.; Caixeta, M.B.; Ribeiro, G.S.; Silva, L.D.; Araujo, O.A.; Rocha, T.L. Differential bioaccumulation and histopathological changes induced by iron oxide nanoparticles and ferric chloride in the neotropical snail Biomphalaria glabrata. Chemosphere. 2025, 371, 144065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koban, L.A.; King, T.; Huff, T.B.; Furst, K.E.; Nelson, T.R.; Pfluger, A.R.; Kuppa, M.M.; Fowler, A.E. Passive biomonitoring for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances using invasive clams, C. fluminea. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 472, 134463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, P.; Chen, X.M.; Xu, L.; Chen, J.T.; Nie, Q.Q.; Xu, M.J.; Feng, J.Y. LIMD2 is the signature of cell aging-immune/inflammation in acute myocardial infarction. Curr. Med. Chem. 2024, 31, 2400–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C.; Du, L.Q.; Johnson, M.; McCullough, B.D. Comparing programming languages for data analytics: Accuracy of estimation in Python and R. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Min. Knowl. Discov. 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-Y. L.; Kaufman, I.D.; Hsu, P.Y. A ggplot-based single-gene viewer reveals insights into the translatome and other nucleotide-resolution omics data. bioRxiv: Prepr. Serve. Bio. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, J.C.V.A.; dos-Santos, J.A.A. and Faria, R.X. Ecotoxicity assays in the evaluation of molluskicidal agents from natural products in freshwater mollusks of medical importance: Lack of information and the choice of tested organisms. Bol. Latinoam. Caribe Plantas Med. Aromat. 2025, 24, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sole, M.; Freitas, R.; Rivera-Ingraham, G. The use of an in vitro approach to assess marine invertebrate carboxylesterase responses to chemicals of environmental concern. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 82, 103561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Yuan, X.P.; Xie, M.; Gao, J.W.; Xiong, Z.Z.; Song, R.; Xie, Z.G.; Ou, D.S. The impact of niclosamide exposure on the activity of antioxidant enzymes and the expression of glucose and lipid metabolism genes in black carp (Mylopharyngodon piceus). Genes. 2023, 14, 2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xiao, R.; Guo, Y.T.; Wang, Q.; Cui, Y.; Xiu, Y.J.; Ma, Z.W.; Zhang, M.X. Changes in soil microbial community composition during Phragmites australis straw decomposition in salt marshes with freshwater pumping. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 762, 143996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juranic, I.O.; Drakulic, B.J.; Petrovic, S.D.; Mijin, D.Z.; Stankovic, M.V. QSAR study of acute toxicity of N-substituted fluoroacetamides to rats. Chemosphere. 2006, 62, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paul-Clark, M.J.; Gilroy, D.W.; Willis, D.; Willoughby, D.A.; Tomlinson, A. Nitric oxide synthase inhibitors have opposite effects on acute inflammation depending on their route of administration. J. Immunol. 2001, 166, 1169–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, C.Y.; Lee, J.D.; Park, C.; Choi, Y.H.; Kim, G.Y. Curcumin attenuates the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated BV2 microglia. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2007, 28, 1645–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Guo, Y.L.; Pan, M.Z.; Li, X.X.; Huang, D.; Liu, Y.; Wu, C.L.; Zhang, W.B.; Mai, K.S. Functions of forkhead box O on glucose metabolism in abalone Haliotis discus hannai and its responses to high levels of dietary lipid. Genes. 2021, 12, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagade, V.M.; Taware, S.S.; Muley, D.V. Seasonal variation in oxygen: nitrogen ratio of Soletellina diphos of Bhatye estuary, Ratnagiri coast, India. J. Immunol. 2013, 34, 123–126, (retrieved from Web of Science Core Collection). [Google Scholar]

- Malley, D.F.; Klaverkamp, J.F.; Brown, S.B.; Chang, P.S.S. Increase in metallothionein in freshwater mussels Anodonta grandis grandis exposed to cadmium in the laboratory and the field. Water Pollut. Res. J. Can. 1993, 28, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmi, M.V.; Mastrodonato, M.; Semeraro, D.; Mentino, D.; Capriello, T.; La Pietra, A.; Giarra, A.; Scillitani, G.; Ferrandino, I. Aluminum exposure alters the pedal mucous secretions of the chocolate-band snail, Eobania vermiculata (Gastropoda: Helicidae). Microsc. Res. Tech. 2024, 87, 1453–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaber, O.A.; Asran, A.A.; Khider, F.K.; El-Shahawy, G.; Abdel-Tawab, H.; Elfayoumi, H.M.K. Efficacy of biopesticide Protecto (Bacillus thuringiensis) (BT) on certain biochemical activities and histological structures of land snail Monacha cartusiana (Muller, 1774). Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control. 2022, 32, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.R.; Lei, L.; Sun, Y.M.; Shi, X.J.; Fu, K.Y.; Hua, J.H.; Martyniuk, C.J.; Han, J.; Yang, L.H.; Zhou, B.S. Niclosamide exposure at environmentally relevant concentrations efficaciously inhibited the growth and disturbed the liver-gut Axis of Adult Male Zebrafish. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 11516–11526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamri, A.A.; Ayyad, M.A.; Mohamedbakr, H.G.; Hossameldin, G.; Soliman, U.A.; Almashnowi, M.Y.; Pan, J.H.; Helmy, E.T. Green magnetically separable molluscicide Ba-Ce-Cu ferrite/TiO2 nanocomposite for controlling terrestrial gastropods Monacha Cartusiana. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiole, F.; Giachero, S.; Fossati, S.M.; Rocchi, A.; Zullo, L. mTOR as a marker of exercise and fatigue in Octopus vulgaris arm. Front Physiol. 2019, 10, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H. X.; Wei, S.S.; Tu, Z.H.; Hu, M.H.; Guo, B.Y.; Wang, Y.J. Polybrominated diphenyl ether-47 and food shortage impair the byssal attachment and health of marine mussels. Sci, Total, Environ. 2023, 891, 164415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.Y.; Li, C.; Su, Q.T.; Lin, Y.Y.; Zou, Z.R. Screening the Efficacy and Safety of Molluscicides from Three Leaf Extracts of Chimonanthus against the Invasive Apple Snail, Pomacea canaliculata. Molecules. 2024, 29, 2487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.G.; Yu, K.; Huang, C.J.; Yu, L.Q.; Zhu, B.Q.; Lam, P.K.S.; Lam, J.C.W.; Zhou, B.S. Prenatal Transfer of Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) Results in Developmental Neurotoxicity in Zebrafish Larvae. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 9727–9734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Q.; Xu, K.F.; Chou, L.B.; Cui, Q.; Hu, G.J.; Zhang, B.B.; Tu, K.; Luo, W.R.; Ma, L.Y.; Guo, J.; Tan, H.Y.; Wei, S.; Zhang, X.W.; Yu, H.X.; Shi, W. Mechanism Directed Toxicity Testing and Instrumental Analysis Make Key Toxicant Identification More Targeted and Efficient: A Case in the Yangtze River. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 11985–11994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Gendy, K.S.; Gad, A.F.; Radwan, M.A. Physiological and behavioral responses of land molluscs as biomarkers for pollution impact assessment: A review. Environ. Res. 2021, 193, 110558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vliet, S.M.F.; Dasgupta, S.; Sparks, N.R.L.; Kirkwood, J.S.; Vollaro, A.; Hur, M.; zur Nieden, N.I.; Volz, D.C. Maternal-to-zygotic transition as a potential target for niclosamide during early embryogenesis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2019, 380, 114699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.; Shen, Y.H.; Zhang, X.W.; Lin, D.; Xia, P.; Song, M.Y.; Yan, L.; Zhong, W.J.; Gou, X.; Wang, C.; Wei, S.; Yu, H.X.; Shi, W. Effect-Directed Analysis Based on the Reduced Human Transcriptome (RHT) to Identify Organic Contaminants in Source and Tap Waters along the Yangtze River. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 7840–7852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siefkes, M.J. Use of physiological knowledge to control the invasive sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) in the Laurentian Great Lakes. Conserv. Physiol. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, F.; Ame, S.M.; Tian-Bi, Y.N.T.; Hofkin, B.V.; Webster, B.L.; Diakité, N.R.; N’Goran, E.K.; Kabole, F.; Khamis, I.S.; Gouvras, A.N.; Emery, A.M.; Pennance, T.; Rabone, M.; Kinung’hi, S.; Hamidou, A.A.; Mkoji, G.M.; Mclaughlin, J.P.; Kuris, A.M.; Loker, E.S.; Knopp, S.; Rollinson, D. Snail-Related Contributions from the schistosomiasis consortium for operational research and evaluation program including xenomonitoring, focal mollusciciding, biological control, and modeling. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Bioaccumulation of niclosamide and nutrient concentrations in digestive glands and foot tissues of C. cahayensis following 60-day exposure. (A) Glycogen, (B) Lipid, (C) Protein. Capital letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between tissues at the same concentrations, while lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between concentrations within the same tissue. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5).

Figure 1.

Bioaccumulation of niclosamide and nutrient concentrations in digestive glands and foot tissues of C. cahayensis following 60-day exposure. (A) Glycogen, (B) Lipid, (C) Protein. Capital letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between tissues at the same concentrations, while lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between concentrations within the same tissue. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5).

Figure 2.

Histopathology of digestive glands (H&E, ×200) and digestive tubule phase distribution in C. cahayensis following 60-day exposure. (A) Control group showing holding phases with thickened digestive cells; (B) 7.5 μg/L group featuring absorptive phases (ABP) with hemocyte nodules (HA); (C) 15 μg/L group displaying atrophic phases (AP) and holding phases with hemocyte infiltration (HI) and nodules (HA); (D) 30 μg/L group demonstrating extensive hemocyte infiltration (HI); (E) 50 μg/L group exhibiting atrophic phases (AP) with hemocyte nodules (HA), (F) Quantitative phases distribution. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 150).

Figure 2.

Histopathology of digestive glands (H&E, ×200) and digestive tubule phase distribution in C. cahayensis following 60-day exposure. (A) Control group showing holding phases with thickened digestive cells; (B) 7.5 μg/L group featuring absorptive phases (ABP) with hemocyte nodules (HA); (C) 15 μg/L group displaying atrophic phases (AP) and holding phases with hemocyte infiltration (HI) and nodules (HA); (D) 30 μg/L group demonstrating extensive hemocyte infiltration (HI); (E) 50 μg/L group exhibiting atrophic phases (AP) with hemocyte nodules (HA), (F) Quantitative phases distribution. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 150).

Figure 3.

Quantitative assessment of digestive gland inflammatory parameters in C. cahayensis following 60-day exposure. (A) Proportion of hemocyte infiltration; (B) Proportion of hemocyte nodules. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 150).

Figure 3.

Quantitative assessment of digestive gland inflammatory parameters in C. cahayensis following 60-day exposure. (A) Proportion of hemocyte infiltration; (B) Proportion of hemocyte nodules. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 150).

Figure 4.

Epidermal histopathology in the foot of C. cahayensis following 60-day exposure (H&E, ×200). (A) Control group showing intact epidermis with shallow folds (42.64 μm); (B) 7.5 μg/L group exhibiting vacuolation (V), deepened folds (85.22 μm), and undifferentiated cells (U); (C) 15 μg/L group showing with vacuolation(V) and deepened folds (124.01 μm); (D) 30 μg/L group presenting vacuolation(V) and deepened folds (91.28 μm); (E) 50 μg/L group demonstrating vacuolation (V) and deepened folds (158.13 μm).

Figure 4.

Epidermal histopathology in the foot of C. cahayensis following 60-day exposure (H&E, ×200). (A) Control group showing intact epidermis with shallow folds (42.64 μm); (B) 7.5 μg/L group exhibiting vacuolation (V), deepened folds (85.22 μm), and undifferentiated cells (U); (C) 15 μg/L group showing with vacuolation(V) and deepened folds (124.01 μm); (D) 30 μg/L group presenting vacuolation(V) and deepened folds (91.28 μm); (E) 50 μg/L group demonstrating vacuolation (V) and deepened folds (158.13 μm).

Figure 5.

Quantitative assessment of epidermal parameters in the foot of C. cahayensis following 60-day exposure. (A) Fold depth, (B) Vacuole numerical density, and (C) Vacuolar area fraction. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 150).

Figure 5.

Quantitative assessment of epidermal parameters in the foot of C. cahayensis following 60-day exposure. (A) Fold depth, (B) Vacuole numerical density, and (C) Vacuolar area fraction. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 150).

Figure 6.

Muscle tissue histology in the foot of C. cahayensis following 60-day exposure (H&E, ×200). (A) Control group showing normal muscle fiber morphology; (B) 7.5 μg/L group exhibiting reduced fiber diameter; (C) 15 μg/L group displaying diminished fiber diameter and density; (D) 30 μg/L group presenting decreased fiber diameter and density with fiber curvature; (E) 50 μg/L group demonstrating severe reductions in diameter/density and pronounced curvature. Red arrows indicate curved fibers.

Figure 6.

Muscle tissue histology in the foot of C. cahayensis following 60-day exposure (H&E, ×200). (A) Control group showing normal muscle fiber morphology; (B) 7.5 μg/L group exhibiting reduced fiber diameter; (C) 15 μg/L group displaying diminished fiber diameter and density; (D) 30 μg/L group presenting decreased fiber diameter and density with fiber curvature; (E) 50 μg/L group demonstrating severe reductions in diameter/density and pronounced curvature. Red arrows indicate curved fibers.

Figure 7.

Quantitative assessment of myofiber parameters in the foot of C. cahayensis following 60-day exposure. (A) Muscle fiber diameter, and (B) Muscle fiber density. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 150).

Figure 7.

Quantitative assessment of myofiber parameters in the foot of C. cahayensis following 60-day exposure. (A) Muscle fiber diameter, and (B) Muscle fiber density. Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 150).

Figure 8.

Concentration-response regression models for normalized pathological indices in C. cahayensis following 60-day exposure. Digestive gland parameters (A) Atrophic phase proportion, (B) Hemocyte infiltration proportion, (C) Hemocyte nodule proportion; Foot parameters, (D) Fold depth, (E) Vacuole numerical density, (F) Vacuolar area fraction, (G) Muscle fiber diameter, (H) Muscle fiber density.

Figure 8.

Concentration-response regression models for normalized pathological indices in C. cahayensis following 60-day exposure. Digestive gland parameters (A) Atrophic phase proportion, (B) Hemocyte infiltration proportion, (C) Hemocyte nodule proportion; Foot parameters, (D) Fold depth, (E) Vacuole numerical density, (F) Vacuolar area fraction, (G) Muscle fiber diameter, (H) Muscle fiber density.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).