Submitted:

13 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

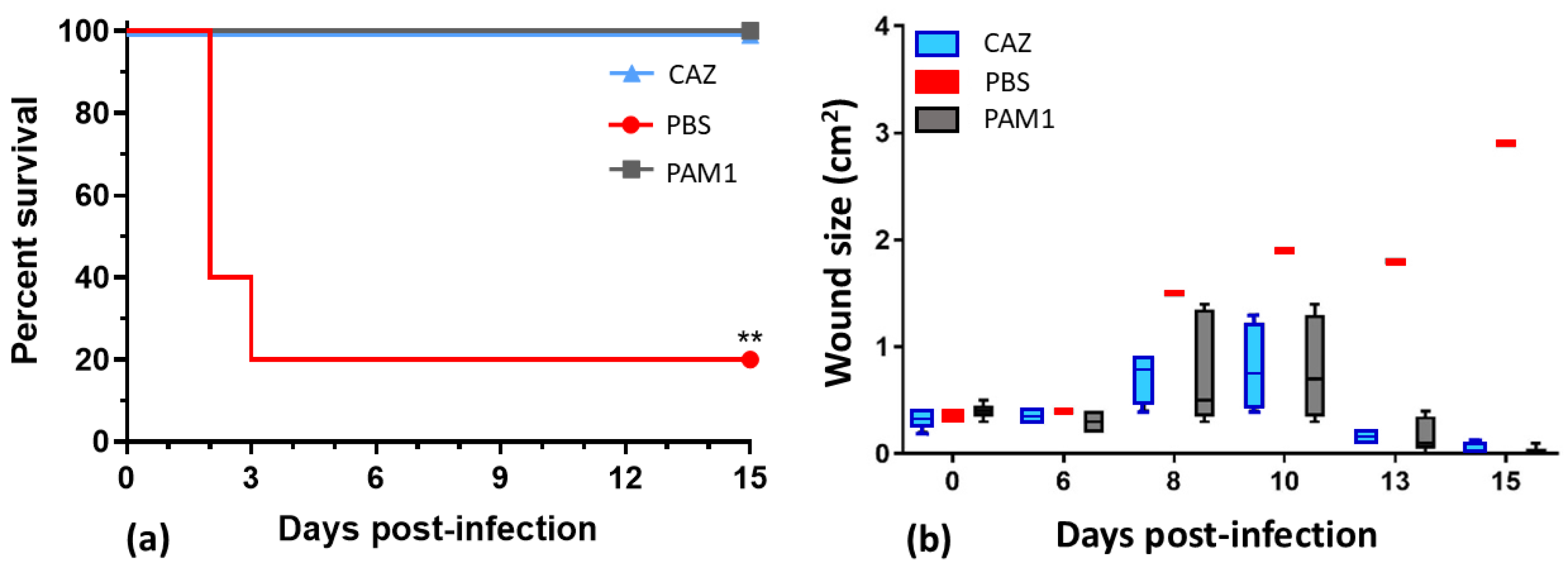

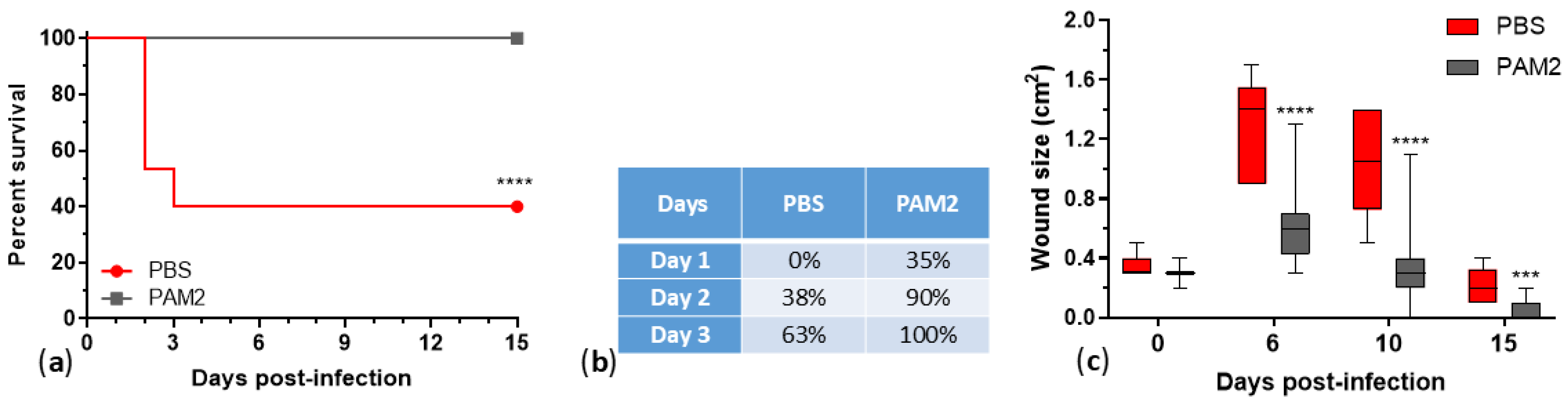

Phages show efficacy against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, but limited host ranges require combining them in cocktails. In this work, we characterized 25 P. aeruginosa phages, developed therapeutic cocktails active against diverse clinical isolates, and tested phage efficacy in a mouse incisional wound model. These phages represent seven genera, and genomic and phenotypic analyses indicate that 24/25 are lytic and suitable for phage therapy. Phage host ranges on a diversity panel of 156 P. aeruginosa strains that included 106 sequence types varied from 8% to 54%, and together the 24 lytic phages were active against 133 strains (85%). All of the phages reduced bacterial counts in biofilms. A cocktail of five lytic phages, WRAIR_PAM1, covered 56% of the strain panel, protected 100% of mice from lethal systemic infection (vs. 20% survival in the saline-treated group) and accelerated healing of infected wounds. An improved 5-phage cocktail, WRAIR_PAM2, was formulated by a rational design approach (using phages with broader host ranges, more complementing activity, relatively low resistance background, and compatibility in mixes). WRAIR_PAM2 covered 76% of highly diverse clinical isolates and demonstrated significant efficacy against topical and systemic P. aeruginosa infection, indicating that it is a promising therapeutic candidate.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

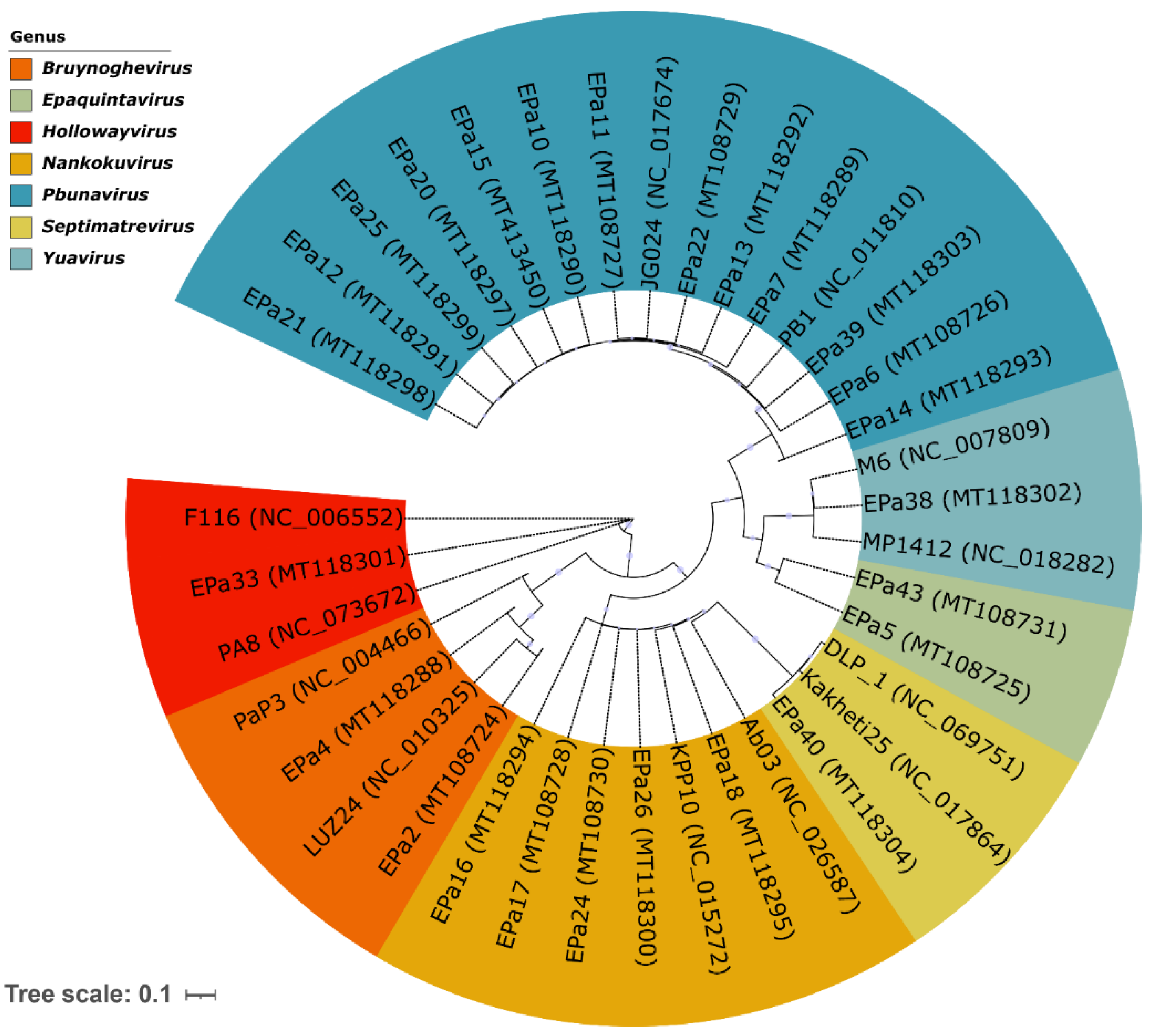

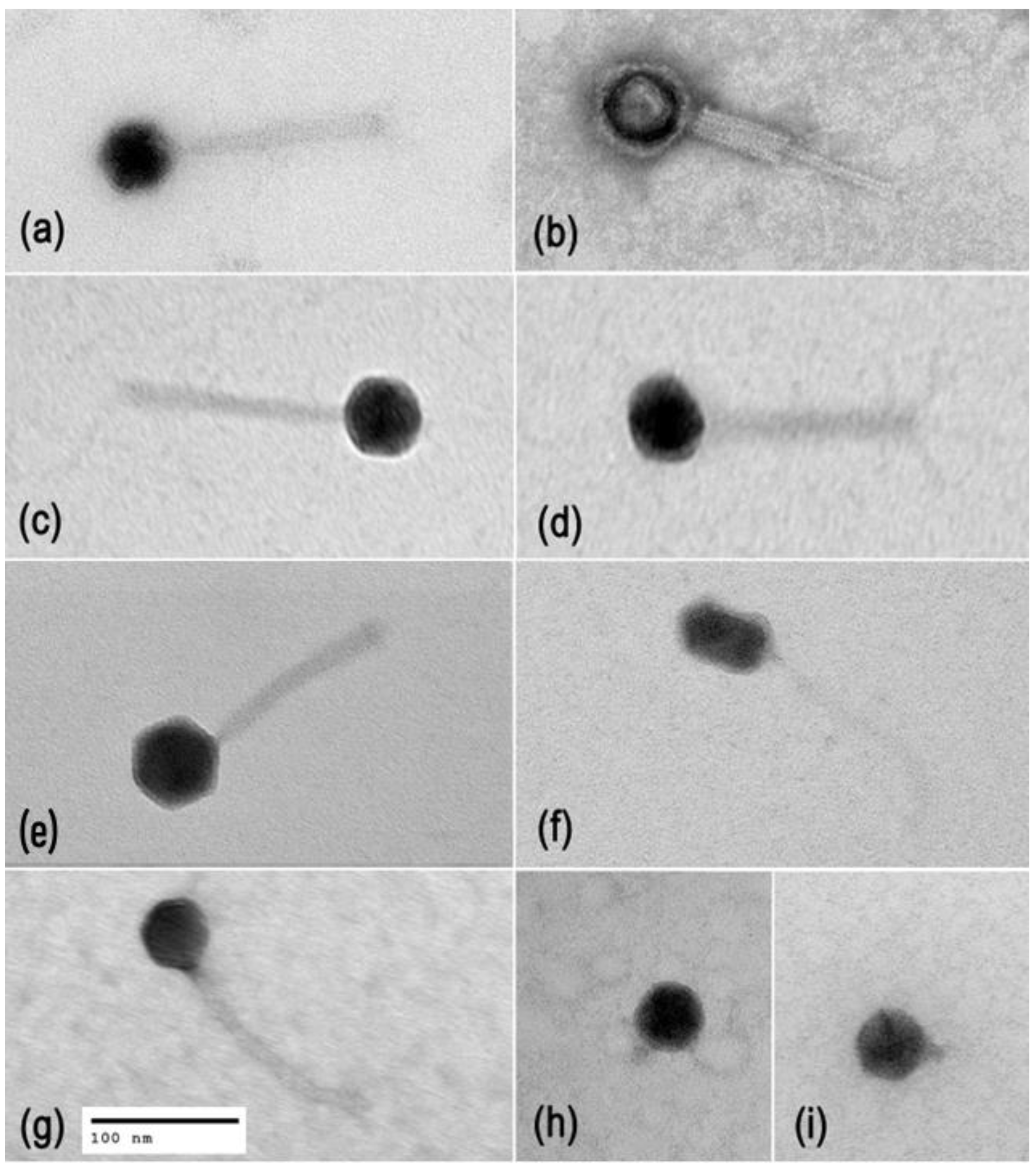

2.1. Phage Diversity, Lifestyles, and Morphology

2.2. Phage Host Range Testing against Highly Diverse P. aeruginosa Strains

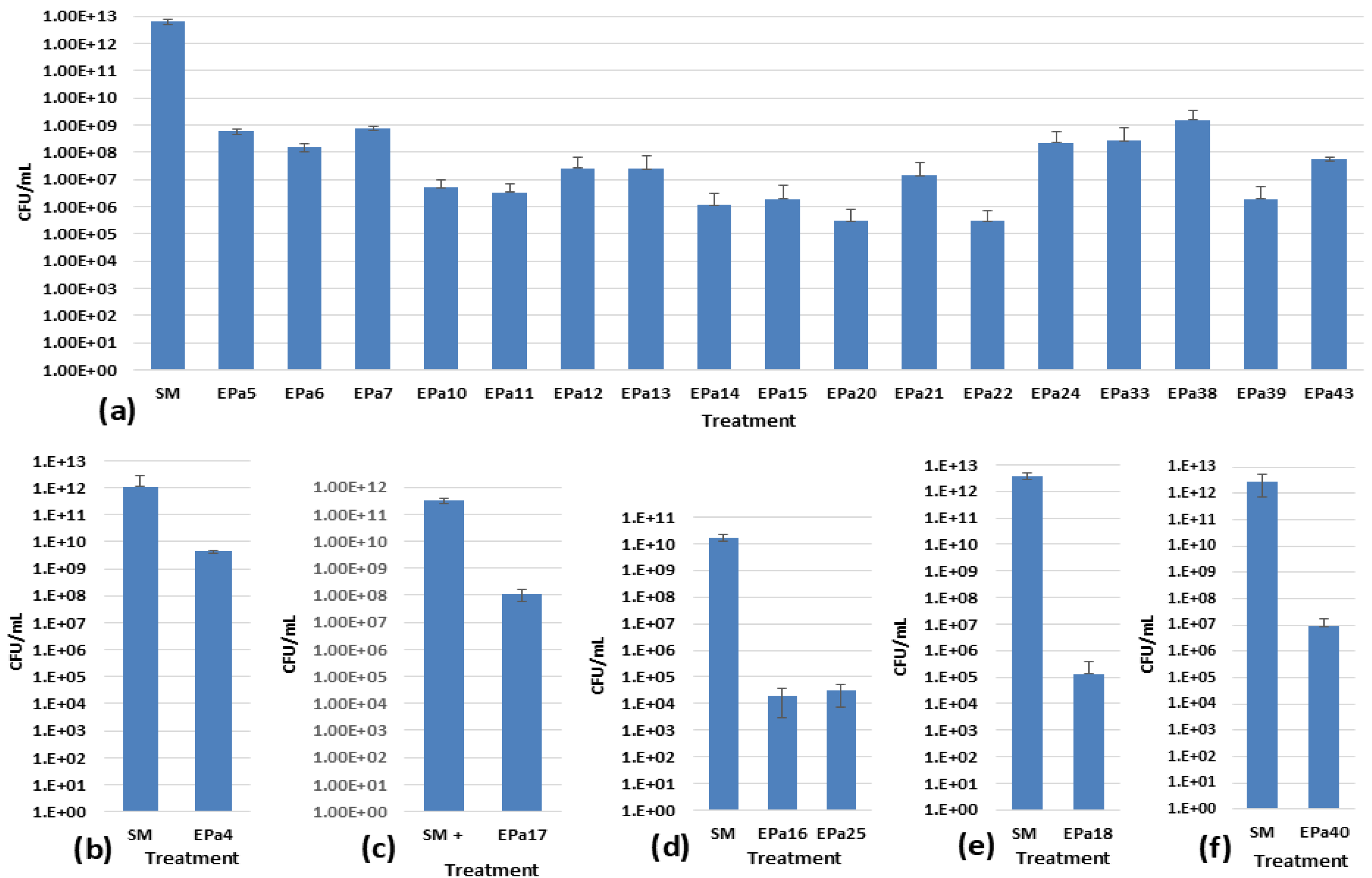

2.3. Phage Anti-biofilm Activity

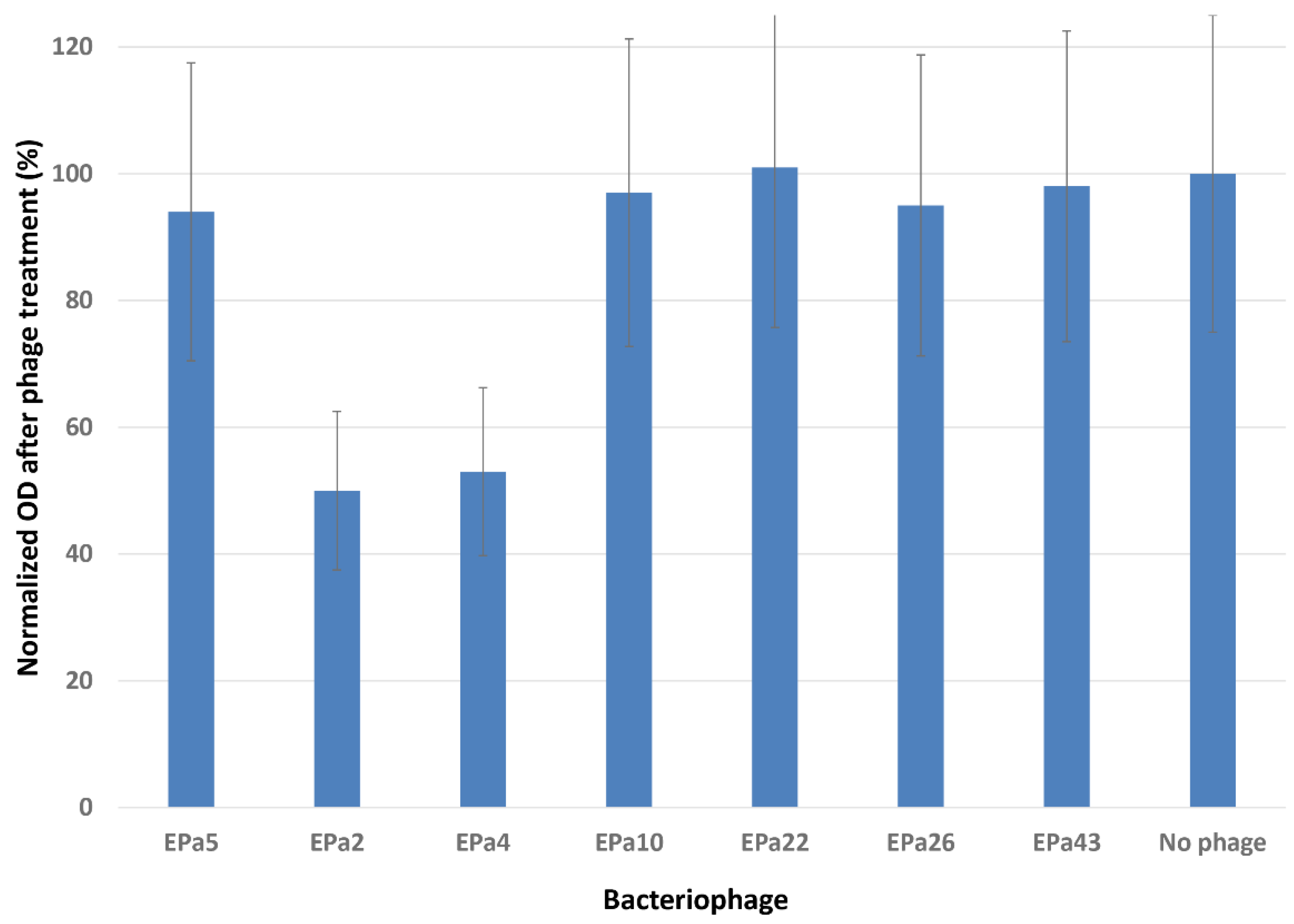

2.4. Phage Cocktail WRAIR_PAM1 and Its Efficacy in a Mouse Wound Model

2.5. Using Rational Design for Developing an Improved Phage Cocktail

2.6. Identification of Phage Receptors on Bacterial Cell Surface

2.7. Predicted Pairwise Host Ranges and Selection of Promising Phage Candidates

2.8. Testing Stability of Single Phages and Their Pairs.

2.9. Measuring Frequencies of Host Resistance Mutations

2.10. Improved Cocktail WRAIR_PAM2 and Its Efficacy against P. aeruginosa Infection in Mice

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains, Media, and Storage of P. aeruginosa and Phage Stocks

4.2. Phage Propagation, Purification, Titration and Plaque Assays

4.3. Phage Host Range Testing

4.4. Biofilm Degradation Assay Using an MBEC™ Biofilm Inoculator

4.5. Phage Bactericidal Activity in Biofilms

4.6. Transmission Electron Microscopy of Phage Particles

4.7. Phage Receptor Identification Using P. aeruginosa PAO1 Isogenic Mutants

4.8. Phage Genome Analysis

4.9. Testing Stability of Single Phages and Their Pairs

4.10. Determination of P. aeruginosa Resistance Mutation Frequencies to Single Phages and Phage Pairs

4.11. Testing of Phage Cocktail Efficacy in a Mouse Wound P. aeruginosa Infection Model

Ethics Approval Statement

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CAZ | Ceftazidime |

| CFU | Colony-forming unit |

| EOP | Efficiency of plating |

| HIB | Heart Infusion Broth |

| PAM | Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage mix |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| MLST | Multilocus sequence typing |

| MOI | Multiplicity of infection |

| MRSN | Multidrug-Resistant Organism Repository and Surveillance Network |

| PDR | Pandrug-resistant |

| PFU | Plaque-forming unit |

| ST | Sequence type |

| T4P | Type IV pili |

| WRAIR | Walter Reed Army Institute of Research |

| XDR | Extensively drug-resistant |

References

- Reynolds, D.; Kollef, M. The epidemiology and pathogenesis and treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections: an update. Drugs 2021, 81, 2117–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.J; Kuzel, T.M.; Shafikhani, S.H. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: infections, animal modeling, and therapeutics. Cells 2023, 12, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keen, E.F., 3rd; Murray, C.K.; Robinson, B.J.; Hospenthal, D.R.; Co, E.M.; Aldous, W.K. Changes in the incidences of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant organisms isolated in a military medical center. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010, 31, 728–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzopardi, E.A.; Azzopardi, E.; Camilleri, L.; Villapalos, J.; Boyce, D.E.; Dziewulski, P.; Dickson, W.A.; Whitaker, I.S. Gram negative wound infection in hospitalised adult burn patients – systematic review and metanalysis. PLoS One 2014, 9, e95042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norbury, W.; Herndon, D.N.; Tanksley, J.; Jeschke, M.G.; Finnerty, C.C. Infection in burns. Surg. Infect. (Larchmt) 2016, 17, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslova, E.; Eisaiankhongi, L.; Sjöberg, F.; McCarthy, R.R. Burns and biofilms: priority pathogens and in vivo models. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2021, 7, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemian, S.; Karami-Zarandi, M.; Heidari, H.; Khoshnood, S.; Kouhsari, E.; Ghafourian, S. Maleki, A.; Kazemian, H. Molecular characterizations of antibiotic resistance, biofilm formation, and virulence determinants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from burn wound infection. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2023, 37, e24850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, T.C.; Stinner, D.J.; Mack, A.W.; Potter, B.K.; Beer, R.; Eckel, T.T.; Possley, D.R.; Beltran, M.J.; Hayda, R.A.; Andersen, R.C.; et al. Microbiology and injury characteristics in severe open tibia fractures from combat. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012, 72, 1062–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akers, K.S.; Mende, K.; Cheatle, K.A.; Zera, W.C.; Yu, X.; Beckius, M.L.; Aggarwal, D.; Li, P.; Sanchez, C.J.; Wenke, J.C.; et al. Biofilms and persistent wound infections in United States military trauma patients: a case-control analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribble, D.R.; Krauss, M.R.; Murray, C.K.; Warkentien, T.E.; Lloyd, B.A.; Ganesan, A.; Greenberg, L.; Xu, J.; Li, P.; Carson, M.L.; et al. Epidemiology of trauma-related infections among a combat casualty cohort after initial hospitalization: the trauma infectious disease outcomes study. Surg. Infect. (Larchmt) 2018, 19, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mende, K.; Akers, K.S.; Tyner, S.D.; Bennett, J.W.; Simons, M.P.; Blyth, D.M.; Li, P.; Stewart, L.; Tribble, D.R. Multidrug-resistant and virulent organisms trauma infections: Trauma Infectious Disease Outcomes Study Initiative. Mil. Med. 2022, 187, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, R.; Grande, R.; Butrico, L.; Rossi, A.; Settimio, U.F.; Caroleo, B.; Amato, B.; Gallelli, L.; de Franciscis, S. Chronic wound infections: the role of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2015, 13, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffin, M.; Brochiero, E. Repair process impairment by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in epithelial tissues: major features and potential therapeutic avenues. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, C.; Satyamoorthy, K.; Murali, T.S. Microbial interplay in skin and chronic wounds. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2022, 9, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, S.; Feng, C.H.; Huang, R.; Lee, Z.X.; Moua, Y.; Phung, O.J.; Lenhard, J.R. Relative abundance and detection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from chronic wound infections globally. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langendonk, R.F.; Neill, D.R.; Fothergill, J.L. The building blocks of antimicrobial resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: implications for current resistance-breaking therapies. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 665759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciofu, O.; Tolker-Nielsen, T. Tolerance and resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms to antimicrobial agents – how P. aeruginosa can escape antibiotics. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi, M.T.T.; Wibowo, D.; Rehm, B.H.A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, S.; Varshney, K.; Uayan, D.J.; Tenorio, B.G.; Pillay, P.; Sava, S.T. Risk factors and clinical characteristics of pandrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Cureus 2024, 16, e58114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krylov, V.N. Bacteriophages of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: long-term prospects for use in phage therapy. Adv. Virus Res. 2014, 88, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolich, M.P.; Filippov, A.A. Bacteriophage therapy: developments and directions. Antibiotics (Basel) 2020, 9, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holger, D.; Kebriaei, R.; Morrisette, T.; Lev, K.; Alexander, J.; Rybak, M. Clinical pharmacology of bacteriophage therapy: a focus on multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021, 10, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strathdee, S.A.; Hatfull, G.F.; Mutalik, V.K.; Schooley, R.T. Phage therapy: from biological mechanisms to future directions. Cell 2023, 186, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Watanabe, S.; Miyanaga, K.; Kiga, K.; Sasahara, T.; Aiba, Y.; Tan, X.E.; Veeranarayanan, S.; Thitiananpakorn, K.; Nguyen, H.M.; et al. A comprehensive review on phage therapy and phage-based drug development. Antibiotics (Basel) 2024, 13, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour-Khezri, E.; Skurnik, M.; Zarrini, G. Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteriophages and their clinical applications. Viruses 2024, 16, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, D.R.; Perez-Esteban, P.; Kot, W.; Bean, J.E.; Arnot, T.; Hansen, L.H.; Enright, M.C.; Jenkins, A.T.A. A novel bacteriophage cocktail reduces and disperses Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms under static and flow conditions. Microb. Biotechnol. 2016, 9, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegini, Z.; Khoshbayan, A.; Moghadam, M.T.; Farahani, I.; Jazireian, P.; Shariati, A. Bacteriophage therapy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: a review. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2020, 19, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwah, S.; Adisu, M.; Gorems, K.; Abdella, K.; Kassa, T. Assessment of phage-mediated inhibition and removal of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm on medical implants. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 2797–2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saussereau, E.; Debarbieux, L. Bacteriophages in the experimental treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in mice. Adv. Virus Res. 2012, 83, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soothill, J. Use of bacteriophages in the treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2013, 11, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, D.P.; Vilas Boas, D.; Sillankorva, S.; Azeredo, J. Phage therapy: a step forward in the treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 7449–7456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melo, L.D.R.; Oliveira, H.; Pires, D.P.; Dabrowska, K.; Azeredo, J. Phage therapy efficacy: a review of the last 10 years of preclinical studies. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 46, 78–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.M.; Manohar, P.; Gondil, V.S.; Mehra, N.; Oyejobi, G.K.; Odiwuor, N.; Ahmad, T.; Huang, G. The applications of animal models in phage therapy: an update. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2023, 19, 2175519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Agarwal, M.; Kumar Bhartiya, S.; Nath, G.; Kumar Shukla, V. An in vivo wound model utilizing bacteriophage therapy of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2015, 61, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Engeman, E.; Freyberger, H.R.; Corey, B.W.; Ward, A.M.; He, Y.; Nikolich, M.P.; Filippov, A.A.; Tyner, S.D.; Jacobs, A.C. Synergistic killing and re-sensitization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to antibiotics by phage-antibiotic combination treatment. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021, 14, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVay, C.S.; Velásquez, M.; Fralick, J.A. Phage therapy of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in a mouse burn wound model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007, 51, 1934–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Harjai, K.; Chhibber, S. Bacteriophage treatment of burn wound infection caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO in BALB/c mice. Am. J. Biomed. Sci. 2009, 1, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holguín, A.V.; Rangel, G.; Clavijo, V.; Prada, C.; Mantilla, M.; Gomez, M.C.; Kutter, E.; Taylor, C.; Fineran, P.C.; González Barrios, A.F.; et al. Phage ΦPan70, a putative temperate phage, controls Pseudomonas aeruginosa in planktonic, biofilm and burn mouse model assays. Viruses 2015, 7, 4602–4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamer, A.M.A.; Abdelaziz, A.A.; Nosair, A.M.; Al-Madboly, L.A. Characterization of newly isolated bacteriophage to control multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonizing incision wounds in a rat model: in vitro and in vivo approach. Life Sci. 2022, 310, 121085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Meng, W.; Zhang, K.; Wang, J.; Lu, B.; Wang, R.; Jia, K. Topically applied bacteriophage to control multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa-infected wounds in a New Zealand rabbit model. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1031101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanaim, A.M.; Foaad, M.A.; Gomaa, E.Z.; El Dougdoug, K.A.; Mohamed, G.E.; Arisha, A.H.; Khamis, T. Bacteriophage therapy as an alternative technique for treatment of multidrug-resistant bacteria causing diabetic foot infection. Int. Microbiol. 2023, 26, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennes, S.; Merabishvili, M.; Soentjens, P.; Pang, K.W.; Rose, T.; Keersebilck, E.; Soete, O.; François, P.-M.; Teodorescu, S.; Verween, G.; et al. Use of bacteriophages in the treatment of colistin-only-sensitive Pseudomonas aeruginosa septicaemia in a patient with acute kidney injury – a case report. Crit. Care 2017, 21, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, B.K.; Turner, P.E.; Kim, S.; Mojibian, H.R.; Elefteriades, J.A.; Narayan, D. Phage treatment of an aortic graft infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Evol. Med. Public Health. 2018, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslam, S.; Lampley, E.; Wooten, D.; Karris, M.; Benson, C.; Strathdee, S.; Schooley, R.T. Lessons learned from the first 10 consecutive cases of intravenous bacteriophage therapy to treat multidrug-resistant bacterial infections at a single center in the United States. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020, 7, ofaa389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otava, U.E.; Tervo, L.; Havela, R.; Vuotari, L.; Ylänne, M.; Asplund, A.; Patpatia, S.; Kiljunen, S. Phage-antibiotic combination therapy against recurrent Pseudomonas septicaemia in a patient with an arterial stent. Antibiotics (Basel) 2024, 13, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, S.I.; Clark, J.R.; Santos, H.H.; Weesner, K.E.; Salazar, K.C.; Aslam, S.; Campbell, J.W.; Doernberg, S.B.; Blodget, E.; Morris, M.J.; et al. A retrospective, observational study of 12 cases of expanded-access customized phage therapy: production, characteristics, and clinical outcomes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 77, 1079–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onallah, H.; Hazan, R. ; Nir-Paz,R.; PASA16 study group,; Brownstein, M.L.; Fackler, J.R.; Horne, B.; Hopkins, R.; Basu, S.; Yerushalmy, O. et al. Refractory Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections treated with phage PASA16: a compassionate use case series. Med. [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.; Hawkins, C.H.; Anggård, E.E.; Harper, D.R. A controlled clinical trial of a therapeutic bacteriophage preparation in chronic otitis due to antibiotic-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa; a preliminary report of efficacy. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2009, 34, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jault, P.; Leclerc, T.; Jennes, S.; Pirnay, J.P.; Que, Y.A.; Resch, G.; Rousseau, A.F.; Ravat, F.; Carsin, H.; Le Floch, R.; et al. Efficacy and tolerability of a cocktail of bacteriophages to treat burn wounds infected by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PhagoBurn): a randomised, controlled, double-blind phase 1/2 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Le, S.; Zhu, T.; Wu, N. Regulations of phage therapy across the world. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1250848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceyssens, P.-J.; Lavigne, R.; Mattheus, W.; Chibeu, A.; Hertveldt, K.; Mast, J.; Robben, J.; Volckaert, G. Genomic analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phages LKD16 and LKA1: establishment of the ɸKMV subgroup within the T7 supergroup. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 6924–6931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceyssens, P.-J.; Hertveldt, K.; Ackermann, H.-W.; Noben, J.-P.; Demeke, M.; Volckaert, G.; Lavigne, R. The intron-containing genome of the lytic Pseudomonas phage LUZ24 resembles the temperate phage PaP3. Virology 2008, 377, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debarbieux, L.; Leduc, D.; Maura, D.; Morello, E.; Criscuolo, A.; Grossi, O.; Balloy, V.; Touqui, L. Bacteriophages can treat and prevent Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infections. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 201, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbe, J.; Bunk, B.; Rohde, M.; Schobert, M. Sequencing and characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage JG004. BMC Microbiol. 2011, 11, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Essoh, C.; Blouin, Y.; Loukou, G.; Cablanmian, A.; Lathro, S.; Kutter, E.; Thien, H.V.; Vergnaud, G.; Pourcel, C. The susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from cystic fibrosis patients to bacteriophages. PLoS One 2013, 8, e60575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiatek, M.; Mizak, L.; Parasion, S.; Gryko, R.; Olender, A.; Niemcewicz, M. Characterization of five newly isolated bacteriophages active against Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical strains. Folia Microbiol. (Praha) 2015, 60, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Deng, C.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, C.; Wang, J.; Rao, X.; Hu, F.; Lu, S. Characterization and genomic analyses of Pseudomonas aeruginosa podovirus TC6: establishment of genus Pa11virus. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszak, T.; Danis-Wlodarczyk, K.; Arabski, M.; Gula, G.; Maciejewska, B.; Wasik, S.; Lood, C.; Higgins, G.; Harvey, B.J.; Lavigne, R.; et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA5oct jumbo phage impacts planktonic and biofilm population and reduces its host virulence. Viruses 2019, 11, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knezevic, P.; Kostanjsek, R.; Obreht, D.; Petrovic, O. Isolation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa specific phages with broad activity spectra. Curr. Microbiol. 2009, 59, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbe, J.; Wesche, A.; Bunk, B.; Kazmierczak, M.; Selezska, K.; Rohde, C.; Sikorski, J.; Rohde, M.; Jahn, D.; Schobert, M. Characterization of JG024, a Pseudomonas aeruginosa PB1-like broad host range phage under simulated infection conditions. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essoh, C.; Latino, L.; Midoux, C.; Blouin, Y.; Loukou, G.; Nguetta, S.-P.A.; Lathro, S.; Cablanmian, A.; Kouassi, A.K.; Vergnaud, G.; et al. Investigation of a large collection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteriophages collected from a single environmental source in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0130548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, S.; Ruotsalainen, P.; Jalasvuori, M. On-demand isolation of bacteriophages against drug-resistant bacteria for personalized phage therapy. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latz, S.; Krüttgen, A.; Häfner, H.; Buhl, E.M.; Ritter, K.; Horz, H.-P. Differential effect of newly isolated phages belonging to PB1-like, ɸKZ-like and LUZ24-like viruses against multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa under varying growth conditions. Viruses 2017, 9, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karumidze, N.; Thomas, J.A.; Kvatadze, N.; Goderdzishvili, M.; Hakala, K.W.; Weintraub, S.T.; Alavidze, Z.; Hardies, S.C. Characterization of lytic Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteriophages via biological properties and genomic sequences. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2012, 94, 1609–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danis-Wlodarczyk, K.; Olszak, T.; Arabski, M.; Wasik, S.; Majkowska-Skrobek, G.; Augustyniak, D.; Gula, G.; Briers, Y.; Jang, H.B.; Vandenheuvel, D.; et al. Characterization of the newly isolated lytic bacteriophages KTN6 and KT28 and their efficacy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0127603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forti, F.; Roach, D.R.; Cafora, M.; Pasini, M.E.; Horner, D.S.; Fiscarelli, E.V.; Rossitto, M.; Cariani, L.; Briani, F.; Debarbieux, L.; et al. Design of a broad-range bacteriophage cocktail that reduces Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms and treats acute infections in two animal models. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e02573–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, A.R.; De Vos, D.; Friman, V.P.; Pirnay, J.-P.; Buckling, A. Effects of sequential and simultaneous applications of bacteriophages on populations of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in vitro and in wax moth larvae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 5646–5652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feary, T.W.; Fisher, E.Jr.; Fisher, T.N. Lysogeny and phage resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1963, 113, 426–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, S.; Yao, X.; Lu, S.; Tan, Y.; Rao, X.; Li, M.; Jin, X.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, N.C.; et al. Chromosomal DNA deletion confers phage resistance to Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friman, V.P.; Soanes-Brown, D.; Sierocinski, P.; Molin, S.; Johansen, H.K.; Merabishvili, M.; Pirnay, J.-P.; De Vos, D.; Buckling, A. Pre-adapting parasitic phages to a pathogen leads to increased pathogen clearance and lowered resistance evolution with Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis bacterial isolates. J. Evol. Biol. 2016, 29, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.M.; Faustino, A.; Pastrana, L.M.; Bañobre-López, M.; Sillankorva, S. Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 in vitro time-kill kinetics using single phages and phage formulations – modulating death, adaptation, and resistance. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021, 10, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.C.T.; Friman, V.-P.; Smith, M.C.M.; Brockhurst, M.A. Resistance evolution against phage combinations depends on the timing and order of exposure. mBio 2019, 10, e01652–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boon, M.; Holtappels, D.; Lood, C.; van Noort, V.; Lavigne, R. Host range expansion of Pseudomonas virus LUZ7 is driven by a conserved tail fiber mutation. Phage (New Rochelle) 2020, 1, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaitekenas, A.; Tai, A.S.; Ramsay, J.P.; Stick, S.M.; Kicic, A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistance to bacteriophages and its prevention by strategic therapeutic cocktail formulation. Antibiotics (Basel) 2021, 10, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Forster, T.; Mayer, O.; Curtin, J.J.; Lehman, S.M.; Donlan, R.M. Bacteriophage cocktail for the prevention of biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa on catheters in an in vitro model system. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, B.K.; Abedon, S.T.; Loc-Carrillo, C. Phage cocktails and the future of phage therapy. Future Microbiol. 2013, 8, 769–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merabishvili, M.; Pirnay, J.-P. , De Vos, D. Guidelines to compose an ideal bacteriophage cocktail. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1693, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, C.J.; Rapp, E.M.; Rankin, W.R.; McKenzie, S.M.; Brasko, B.K.; Hebert, K.E.; Bachert, B.A.; Kick, A.R.; Burpo, F.J.; Barnhill, J.C. Combinations of bacteriophage are efficacious against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and enhance sensitivity to carbapenem antibiotics. Viruses 2024, 16, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchi, J.; Minh, C.N.N.; Debarbieux, L.; Weitz, J.S. Multi-strain phage induced clearance of bacterial infections. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2025, 21, e1012793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farlow, J.; Freyberger, H.R.; He, Y.; Ward, A.M.; Rutvisuttinunt, W.; Li, T.; Campbell, R.; Jacobs, A.C.; Nikolich, M.P.; Filippov, A.A. Complete genome sequences of 10 phages lytic against multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 9. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, R.A.; Farlow, J.; Freyberger, H.R.; He, Y.; Ward, A.M.; Ellison, D.W.; Getnet, D.; Swierczewski, B.E.; Nikolich, M.P.; Filippov, A.A. Genome sequences of 17 diverse Pseudomonas aeruginosa phages. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2021, 10, e00031–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondov, B.D.; Treangen, T.J.; Melsted, P.; Mallonee, A.B.; Bergman, N.H.; Koren, S.; Phillippy, A.M. Mash: fast genome and metagenome distance estimation using MinHash. Genome Biol. 2016, 17, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, R.; Brown, N.; Redgwell, T.; Rihtman, B.; Barnes, M.; Clokie, M.; Stekel, D.J.; Hobman, J.; Jones, M.A.; Millard, A. INfrastructure for a PHAge REference Database: identification of large-scale biases in the current collection of cultured phage genomes. Phage (New Rochelle) 2021, 2, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Göker, M. VICTOR: genome-based phylogeny and classification of prokaryotic viruses. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3396–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockenberry, A.J.; Wilke, C.O. BACPHLIP: predicting bacteriophage lifestyle from conserved protein domains. PeerJ 2021, 9, 11396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, M.; Kropinski, A.M. The genome of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa generalized transducing bacteriophage F116. Gene 2005, 346, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcock BP, Raphenya AR, Lau TTY, Tsang KK, Bouchard M, Edalatmand A, Huynh W, Nguyen A-LV, Cheng AA, Liu S. et al. CARD 2020: antibiotic resistome surveillance with the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 48, D517–D525. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L. VFDB: a reference database for bacterial virulence factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 33, D325–D328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebreton, F.; Snesrud, E.; Hall, L.; Mills, E.; Galac, M.; Stam, J.; Ong, A.; Maybank, R.; Kwak, Y.I.; Johnson, S.; et al. A panel of diverse Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates for research and development. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 3, dlab179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treepong, P.; Kos, V.N.; Guyeux, C.; Blanc, D.S.; Bertrand, X.; Valot, B.; Hocquet, D. Global emergence of the widespread Pseudomonas aeruginosa ST235 clone. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 24, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horcajada, J.P.; Montero, M.; Oliver, A.; Sorlí, L.; Luque, S.; Gómez-Zorrilla, S.; Benito, N.; Grau, S. Epidemiology and treatment of multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 2019 32, e00031–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Barrio-Tofiño, E.; López-Causapé, C.; Oliver, A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa epidemic high-risk clones and their association with horizontally-acquired β-lactamases: 2020 update. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 56, 106196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stribling, W.; Hall, L.R.; Powell, A.; Harless, C.; Martin, M.J.; Corey, B.W.; Snesrud, E. ; Ong, A; Maybank, R; Stam, J. et al. Detecting, mapping, and suppressing the spread of a decade-long Pseudomonas aeruginosa nosocomial outbreak with genomics. eLife 2024, 1, 93181.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K.A.; Sutherland, I.W.; Jones, M.V. Biofilm susceptibility to bacteriophage attack: the role of phage-borne polysaccharide depolymerase. Microbiology 1998, 144, 3039–3047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Kim, J.-H.; Son, J.H; Seo, H.-J.; Park, S.-J.; Paek, N.-S.; Kim, S.-K. Characterization of bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus bulgaricus. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004, 14, 503–508. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, C.; Liu, X.; Shan, L. Optimization of liquid media and biosafety assessment for algae-lysing bacterium NP23. Can. J. Microbiol. 2014, 60, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, M.; Ariff, A.B.; Wasoh, H.; Kapri, M.R.; Halim, M. Strategies for improving production performance of probiotic Pediococcus acidilactici viable cell by overcoming lactic acid inhibition. AMB Express 2017, 7, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boukhris, I.; Smaoui, S.; Ennouri, K.; Morjene, N.; Farhat-Khemakhem, A.; Blibech, M.; Alghamdi, O.A.; Chouayekh, H. Towards understanding the antagonistic activity of phytic acid against common foodborne bacterial pathogens using a general linear model. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0231397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.W.; Abbasiliasi, S.; Murugan, P.; Tam, Y.J. Ng, H.S.; Tan J.S. Influence of freeze-drying and spray-drying preservation methods on survivability rate of different types of protectants encapsulated Lactobacillus acidophilus FTDC 3081. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2020, 84, 1913–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, A.S.; Sariwati, A.; Kamei, I. Synergistic interaction of a consortium of the brown-rot fungus Fomitopsis pinicola and the bacterium Ralstonia pickettii for DDT biodegradation. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freddi, L.; Djokic, V.; Petot-Bottin, F.; Girault, G.; Perrot, L.; Vicente, A.F.; Ponsart, C. The use of flocked swabs with a protective medium increases the recovery of live Brucella spp. and DNA detection. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e0072821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chau, J.; Yoon, J.; Hladky, J. Rapid, label-free pathogen identification system for multidrug-resistant bacterial wound infection detection on military members in the battlefield. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0267945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Shui, X.; Wang, H.; Qiu, H.; Tao, C.; Yin, H.; Wang, P. Effects of Bacillus halophilus on growth, intestinal flora and metabolism of Larimichthys crocea. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2023, 35, 101546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, M.G.; Al-Hindi, R.R.; Alotibi, I.A.; Azhari, S.A.; Farsi, R.M.; Teklemariam, A.D. Evaluation of phage-antibiotic combinations in the treatment of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Salmonella enteritidis strain PT1. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavigne, R.; Darius, P.; Summer, E.J.; Seto, D.; Mahadevan, P.; Nilsson, A.S.; Ackermann, H.W.; Kropinski, A.M. Classification of Myoviridae bacteriophages using protein sequence similarity. BMC Microbiol. 2009, 9, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchiyama, J.; Rashel, M.; Takemura, I.; Kato, S.-I.; Ujihara, T.; Muraoka, A.; Matsuzaki, S.; Daibata, M. Genetic characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteriophage KPP10. Arch. Virol. 2012, 157, 733–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohr, J.E.; Chen, F.; Hill, R.T. Genomic analysis of bacteriophage ɸJL001: insights into its interaction with a sponge-associated alpha-proteobacterium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 1598–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceyssens, P.-J.; Mesyanzhinov, V.; Sykilinda, N.; Briers, Y.; Roucourt, B.; Lavigne, R.; Robben, J.; Domashin, A.; Miroshnikov, K.; Volckaert, G.; et al. The genome and structural proteome of YuA, a new Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage resembling M6. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 190, 1429–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyson, Z.A.; Seviour, R.J.; Tucci, J.; Petrovski, S. Genome sequences of Pseudomonas oryzihabitans phage POR1 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage PAE1. Genome Announc. 2016, 4, e01515–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tang, J.; Dang, W.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, F.; Hao, X.; Sun, S.; Liu, X.; Luo, Y.; Li, M.; et al. Isolation and characterization of three Pseudomonas aeruginosa viruses with therapeutic potential. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0463622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evseev, P.V.; Gorshkova, A.S.; Sykilinda, N.N.; Drucker, V.V.; Miroshnikov, K.A. Pseudomonas bacteriophage AN14—a Baikal-borne representative of Yuavirus. Limnol. Freshw. Biol. 2020, 5, 1055–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troshin, K.; Sykilinda, N.; Shuraleva, S.; Tokmakova, A.; Tkachenko, N.; Kurochkina, L.; Miroshnikov, K.; Suzina, N.; Brzhozovskaya, E.; Petrova, K.; et al. Pseudomonas phage Lydia and the evolution of the Mesyanzhinovviridae family. Viruses 2025, 17, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evseev, P.; Lukianova, A.; Sykilinda, N.; Gorshkova, A.; Bondar, A.; Shneider, M.; Kabilov, M.; Drucker, V.; Miroshnikov, K. Pseudomonas phage MD8: genetic mosaicism and challenges of taxonomic classification of lambdoid bacteriophages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, K.A.; Urick, C.D.; Mzhavia, N.; Nikolich, M.P.; Filippov, A.A. Correlation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage resistance with the numbers and types of antiphage systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagemans, J.; Delattre, A.S.; Uytterhoeven, B.; De Smet, J.; Cenens, W.; Aertsen, A.; Ceyssens, P.J.; Lavigne, R. Antibacterial phage ORFans of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage LUZ24 reveal a novel MvaT inhibiting protein. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namonyo, S.; Weynberg, K.D.; Guo, J.; Carvalho, G. The effectiveness and role of phages in the disruption and inactivation of clinical P. aeruginosa biofilms. Environ. Res. 2023, 234, 116586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheljan, F.S.; Hesari, F.S.; Aminifazl, M.S.; Skurnik, M.; Goladze, S.; Zarrini, G. Design of phage-cocktail-containing hydrogel for the treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa-infected wounds. Viruses 2023, 15, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezk, N.; Abdelsattar, A.S.; Elzoghby, D.; Agwa, M.M.; Abdelmoteleb, M.; Aly, R.G.; Fayez, M.S.; Essam, K.; Zaki, B.M.; El-Shibiny, A. Bacteriophage as a potential therapy to control antibiotic-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection through topical application onto a full-thickness wound in a rat model. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2022, 20, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, D.E. The structure and infective process of a Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteriophage containing ribonucleic acid. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1966, 45, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrell, K.; Kropinski, A.M. Identification of the cell wall receptor for bacteriophage E79 in Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PAO. J. Virol. 1977, 23, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceyssens, P.-J.; Lavigne, R. Bacteriophages of Pseudomonas. Future Microbiol. 2010, 5, 1041–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forti, F.; Bertoli, C.; Cafora, M.; Gilardi, S.; Pistocchi, A.; Briani, F. Identification and impact on Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence of mutations conferring resistance to a phage cocktail for phage therapy. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e01477–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markwitz, P.; Lood, C.; Olszak, T.; van Noort, V.; Lavigne, R.; Drulis-Kawa, Z. Genome-driven elucidation of phage-host interplay and impact of phage resistance evolution on bacterial fitness. ISME J. 2022, 16, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cruz, J.C.; Rebollar-Juarez, X.; Limones-Martinez, A.; Santos-Lopez, C.S.; Toya, S.; Maeda, T.; Ceapă, C.D.; Blasco, L.; Tomás, M.; Díaz-Velásquez, C.E.; et al. Resistance against two lytic phage variants attenuates virulence and antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 13, 1280265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, B.J.; Davies, P.; Carstens, E.B.; Kropinski, A.M. Characterization of the genome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteriophage ɸPLS27 with particular reference to the ends of the DNA. J. Virol. 1989, 63, 1587–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Cui, X.; Zhang, F.; He, Y.; Li, L.; Yang, H. Genetic evidence for O-specific antigen as receptor of Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage K8 and its genomic analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceyssens, P.-J.; Brabban, A.; Rogge, L.; Lewis, M.S.; Pickard, D.; Goulding, D.; Dougan, G.; Noben, J.-P.; Kropinski, A.; Kutter, E.; et al. Molecular and physiological analysis of three Pseudomonas aeruginosa phages belonging to the “N4-like viruses”. Virology 2010, 405, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, K; Kanaya, S. ; Ohnishi, M.; Terawaki, Y.; Hayashi, T. The complete nucleotide sequence of ɸCTX, a cytotoxin-converting phage of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: implications for phage evolution and horizontal gene transfer via bacteriophages. Mol. Microbiol. 1999, 31, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibeu, A.; Ceyssens, P.J.; Hertveldt, K.; Volckaert, G.; Cornelis, P.; Matthijs, S.; Lavigne, R. The adsorption of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteriophage ɸKMV is dependent on expression regulation of type IV pili genes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2009, 296, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, T.; Li, L.; Zheng, C.; Tan, D.; Wu, N.; Wang, M.; Zhu, T. Characterization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteriophage L5 which requires type IV pili for infection. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 907958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danis-Wlodarczyk, K.; Vandenheuvel, D.; Jang, H.B.; Briers, Y.; Olszak, T.; Arabski, M.; Wasik, S.; Drabik, M.; Higgins, G.; Tyrrell, J.; et al. A proposed integrated approach for the preclinical evaluation of phage therapy in Pseudomonas infections. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, L.F.; Dos Santos Junior, A.P.; Nicastro, G.G.; Scheunemann, G.; Angeli, C.B.; Rossi, F.P.N.; Quaggio, R.B.; Palmisano, G.; Sgro, G.G.; Ishida, K.; et al. Phages ZC01 and ZC03 require type-IV pilus for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection and have a potential for therapeutic applications. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0152724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsthoorn, R.C.; Garde, G.; Dayhuff, T.; Atkins, J.F.; Van Duin, J. Nucleotide sequence of a single-stranded RNA phage from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: kinship to coliphages and conservation of regulatory RNA structures. Virology 1995, 206, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, S.J.; Sanz, C.; Perham, R.N. Identification and specificity of pilus adsorption proteins of filamentous bacteriophages infecting Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Virology 2006, 345, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roncero, C.; Darzins, A.; Casadaban, M.J. Pseudomonas aeruginosa transposable bacteriophages D3112 and B3 require pili and surface growth for adsorption. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 1899–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cryz, S.J.Jr.; Pitt, T.L.; Fürer, E.; Germanier, R. Role of lipopolysaccharide in virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect. Immun. 1984, 44, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comolli, J.C.; Hauser, A.R.; Waite, L.; Whitchurch, C.B.; Mattick, J.S.; Engel, J.N. Pseudomonas aeruginosa gene products PilT and PilU are required for cytotoxicity in vitro and virulence in a mouse model of acute pneumonia. Infect. Immun. 1999, 67, 3625–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jończyk-Matysiak, E.; Łodej, N.; Kula, D.; Owczarek, B.; Orwat, F.; Międzybrodzki, R.; Neuberg, J.; Bagińska, N.; Weber-Dąbrowska, B.; Górski, A. Factors determining phage stability/activity: challenges in practical phage application. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2019, 17, 583–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delbruck, M. Interference between bacterial viruses: III. The mutual exclusion effect and the depressor effect. J. Bacteriol. 1945, 50, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bürkle, M.; Korf, I.H.E.; Lippegaus, A.; Krautwurst, S.; Rohde, C.; Weissfuss, C.; Nouailles, G.; Tene, X.M.; Gaborieau, B.; Ghigo, G.-M. Phage-phage competition and biofilms affect interactions between two virulent bacteriophages and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. ISME J. 2025, 19, wraf065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippov, A.A.; Sergueev, K.V.; He, Y.; Huang, X.Z.; Gnade, B.T.; Mueller, A.J.; Fernandez-Prada, C.M.; Nikolich, M.P. Bacteriophage-resistant mutants in Yersinia pestis: identification of phage receptors and attenuation for mice. PLoS One 2011, 6, e25486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangalea, M.R.; Duerkop, B.A. Fitness trade-offs resulting from bacteriophage resistance potentiate synergistic antibacterial strategies. Infect. Immun. 2020, 88, e00926–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambrook, J.; Fritsch, E.F.; Maniatis, T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 2nd ed.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bichet, M.C.; Patwa, R.; Barr, J.J. Protocols for studying bacteriophage interactions with in vitro epithelial cell layers. STAR Protoc. 2021, 2, 100697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergueev, K.V.; Filippov, A.A.; Farlow, J.; Su, W.; Kvachadze, L.; Balarjishvili, N.; Kutateladze, M.; Nikolich, M.P. Correlation of host range expansion of therapeutic bacteriophage Sb-1 with allele state at a hypervariable repeat locus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 85, e01209–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sambanthamoorthy, K.; Gokhale, A.A.; Lao, W.; Parashar, V.; Neiditch, M.B.; Semmelhack, M.F.; Lee, I.; Waters, C.M. . Identification of a novel benzimidazole that inhibits bacterial biofilm formation in a broad-spectrum manner. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 4369–4378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, H.W. Basic phage electron microscopy. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009, 501, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouras, G.; Nepal, R.; Houtak, G.; Psaltis, A.J.; Wormald, P.-J.; Vreugde, S. Pharokka: a fast scalable bacteriophage annotation tool. Bioinformatics 2023, 39, btac776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Auch, A.F.; Klenk, H.-P.; Göker, M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinformatics 2013, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lefort, V.; Desper, R.; Gascue, O. FastME 2.0: a comprehensive, accurate, and fast distance-based phylogeny inference program. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 2798–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farris, J.S. Estimating phylogenetic trees from distance matrices. Am. Nat. 1972, 106, 645–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinegger, M.; Söding, J. MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 1026–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Söding, J.; Biegert, A.; Lupas, A.N. The HHpred interactive server for protein homology detection and structure prediction. Nucl. Acids Res. 2005, 33, W244–W248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Phage ID | Genome size, bp | Family* | Genus | Host range | Anti-biofilm effect | Phage receptor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dispersal | Killing | ||||||

| EPa2 | 43,299 | Unclassified | Bruynoghevirus | 32.7% | + | + | T4P, A band (1) |

| EPa4 | 45,439 | Unclassified | Bruynoghevirus | 31.4% | + | + | T4P, A band (1) |

| EPa5 | 64,096 | Mesyanzhinovviridae | Epaquintavirus | 18.6% | – | + | T4P, LPS core (2) |

| EPa6 | 66,031 | Lindbergviridae | Pbunavirus | 46.2% | – | + | T4P, LPS core (2) |

| EPa7 | 65,629 | Lindbergviridae | Pbunavirus | 44.2% | – | + | T4P, LPS core (2) |

| EPa10 | 66,774 | Lindbergviridae | Pbunavirus | 40.4% | – | + | T4P, L-B, VL-B (3) |

| EPa11 | 66,800 | Lindbergviridae | Pbunavirus | 51.3% | – | + | T4P, L-B, VL-B (3) |

| EPa12 | 66,520 | Lindbergviridae | Pbunavirus | 46.2% | – | + | T4P, L-B, VL-B (3) |

| EPa13 | 65,680 | Lindbergviridae | Pbunavirus | 42.3% | – | + | T4P, A, B, L-B, VL-B (4) |

| EPa14 | 65,797 | Lindbergviridae | Pbunavirus | 42.3% | – | + | T4P, A, B, L-B, VL-B (4) |

| EPa15 | 66,002 | Lindbergviridae | Pbunavirus | 54.5% | – | + | T4P, L-B, VL-B (3) |

| EPa16 | 88,727 | Vandenendeviridae | Nankokuvirus | 35.9% | – | + | Unknown** |

| EPa17 | 88,859 | Vandenendeviridae | Nankokuvirus | 30.8% | – | + | Unknown** |

| EPa18 | 88,109 | Vandenendeviridae | Nankokuvirus | 37.8% | – | + | Unknown** |

| EPa20 | 66,505 | Lindbergviridae | Pbunavirus | 42.3% | – | + | T4P, L-B, VL-B (3) |

| EPa21 | 66,764 | Lindbergviridae | Pbunavirus | 39.7% | – | + | T4P, L-B, VL-B (3) |

| EPa22 | 65,897 | Lindbergviridae | Pbunavirus | 51.9% | – | + | T4P, A, B, L-B, VL-B (4) |

| EPa24 | 88,728 | Vandenendeviridae | Nankokuvirus | 46.8% | – | + | T4P, LPS core (2) |

| EPa25 | 66,811 | Lindbergviridae | Pbunavirus | 28.2% | – | + | T4P, L-B, VL-B (3) |

| EPa26 | 88,805 | Vandenendeviridae | Nankokuvirus | 42.9% | – | + | T4P, LPS core (2) |

| EPa33 | 64,021 | Unclassified | Hollowayvirus | 30.1% | – | + | T4P, A, B (5) |

| EPa38 | 61,775 | Mesyanzhinovviridae | Yuavirus | 7.7% | – | + | T4P, LPS core (2) |

| EPa39 | 66,708 | Lindbergviridae | Pbunavirus | 45.5% | – | + | T4P, L-B, VL-B (3) |

| EPa40 | 42,788 | Unclassified | Septimatrevirus | 32.7% | – | + | T4P, A band (1) |

| EPa43 | 64,323 | Mesyanzhinoviridae | Epaquintavirus | 14.1% | – | + | T4P, LPS core (2) |

| Phage | Host range (%) | Phage | Host range (%) | Phage | Host range (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPa11 | 51.3 | EPa11+EPa24 | 59.0 | EPa17+EPa40 | 51.3 |

| EPa16 | 35.9 | EPa11+EPa40 | 53.8 | EPa17+EPa43 | 34.0 |

| EPa17 | 30.8 | EPa11+EPa43 | 55.8 | EPa22+EPa24 | 62.8 |

| EPa22 | 51.9 | EPa16+EPa17 | 51.3 | EPa22+EPa40 | 62.2 |

| EPa24 | 46.8 | EPa16+EPa22 | 60.9 | EPa22+EPa43 | 55.8 |

| EPa40 | 32.7 | EPa16+EPa24 | 51.3 | EPa24+EPa40 | 48.7 |

| EPa43 | 14.1 | EPa16+EPa40 | 44.2 | EPa24+EPa43 | 51.3 |

| EPa11+EPa16 | 57.1 | EPa16+EPa43 | 42.3 | EPa40+EPa43 | 37.2 |

| EPa11+EPa17 | 64.1 | EPa17+EPa22 | 69.2 | Mix-7* | 78.2 |

| EPa11+EPa22 | 62.2 | EPa17+EPa24 | 57.7 | Mix-5** | 76.3 |

| Phage | Resistance frequency | Phage | Resistance frequency | ||

| To single | To mix | To single | To mix | ||

| EPa11 | 7.54×10–6 | 5.70×10–6 | EPa11 | 7.54×10–6 | 2.63×10–8 |

| EPa16 | 1.33×10–6 | EPa17 | 2.19×10–7 | ||

| EPa11 | 7.54×10–6 | 6.40×10–6 | EPa11 | 7.54×10–6 | 8.07×10–6 |

| EPa22 | 3.42×10–6 | EPa24 | 9.39×10–6 | ||

| EPa11 | 7.54×10–6 | 1.58×10–6 | EPa11 | 7.54×10–6 | <8.77×10–9 |

| EPa40 | 2.53×10–7 | EPa43 | <8.77×10–9 | ||

| EPa16 | 1.33×10–6 | 1.67×10–7 | EPa16 | 1.33×10–6 | 2.98×10–6 |

| EPa17 | 2.19×10–7 | EPa22 | 3.42×10–6 | ||

| EPa16 | 1.33×10–6 | 5.35×10–6 | EPa16 | 1.33×10–6 | 1.01×10–6 |

| EPa24 | 9.39×10–6 | EPa40 | 2.53×10–7 | ||

| EPa16 | 1.33×10–6 | <8.77×10–9 | EPa17 | 2.19×10–7 | 4.39×10–8 |

| EPa43 | <8.77×10–9 | EPa22 | 3.42×10–6 | ||

| EPa17 | 2.19×10–7 | 3.51×10–8 | EPa17 | 2.19×10–7 | 8.77×10–8 |

| EPa24 | 9.39×10–6 | EPa40 | 2.53×10–7 | ||

| EPa17 | 2.19×10–7 | <8.77×10–9 | EPa22 | 3.42×10–6 | 6.93×10–6 |

| EPa43 | <8.77×10–9 | EPa24 | 9.39×10–6 | ||

| EPa22 | 3.42×10–6 | 1.19×10–5 | EPa22 | 3.42×10–6 | <8.77×10–9 |

| EPa40 | 2.53×10–7 | EPa43 | <8.77×10–9 | ||

| EPa24 | 9.39×10–6 | 1.19×10–5 | EPa24 | 9.39×10–6 | <8.77×10–9 |

| EPa40 | 2.53×10–7 | EPa43 | <8.77×10–9 | ||

| EPa40 | 2.53×10–7 | <8.77×10–9 | 11+16+17+22+24+40+43 | <8.77×10–9 | |

| EPa43 | <8.77×10–9 | ||||

| Cocktail | Phage | Family | Genus | Host range (%) |

Host receptor | Cocktail activity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAM1 | EPa2 | Unclassified | Bruynoghevirus | 32.7 | T4P, A band (1) | 55.8 |

| EPa4 | Unclassified | Bruynoghevirus | 31.4 | T4P, A band (1) | ||

| EPa5 | Mesyanzhinovviridae | Epaquintavirus | 18.6 | T4P, LPS core (2) | ||

| EPa6 | Lindbergviridae | Pbunavirus | 46.2 | T4P, LPS core (2) | ||

| EPa17 | Vandenendeviridae | Nankokuvirus | 30.8 | Unknown | ||

| PAM2 | EPa11 | Lindbergviridae | Pbunavirus | 51.3 | T4P, L-B, VL-B (3) | 76.3 |

| EPa17 | Vandenendeviridae | Nankokuvirus | 30.8 | Unknown | ||

| EPa22 | Lindbergviridae | Pbunavirus | 51.9 | T4P, A, B, L-B, VL-B (4) | ||

| EPa24 | Vandenendeviridae | Nankokuvirus | 46.8 | T4P, LPS core (2) | ||

| EPa43 | Mesyanzhinovviridae | Epaquintavirus | 14.1 | T4P, LPS core (2) |

| Mutant | Phenotype | Source | Mutant | Phenotype | Source |

| rmd | No A band LPS | Dr. Rob Lavigne (Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Leuven, Belgium) | wzz1 | No long B band | Dr. Karen Maxwell (University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada |

| wbpL | A/B band synthesis initiation defect | wzz2 | No very long B band | ||

| rmlC* | Truncated LPS core, no A, B bands | wzz1,2 | No long/very long B band | ||

| fliA | No flagella | wapQ | No phosphate in LPS inner core | ||

| pilA | No type IV pili | wbpM | No B band | ||

| fliA algC pilA | No flagella, A band, type IV pili | rmlC* | Truncated LPS core, no A, B bands |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).