Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

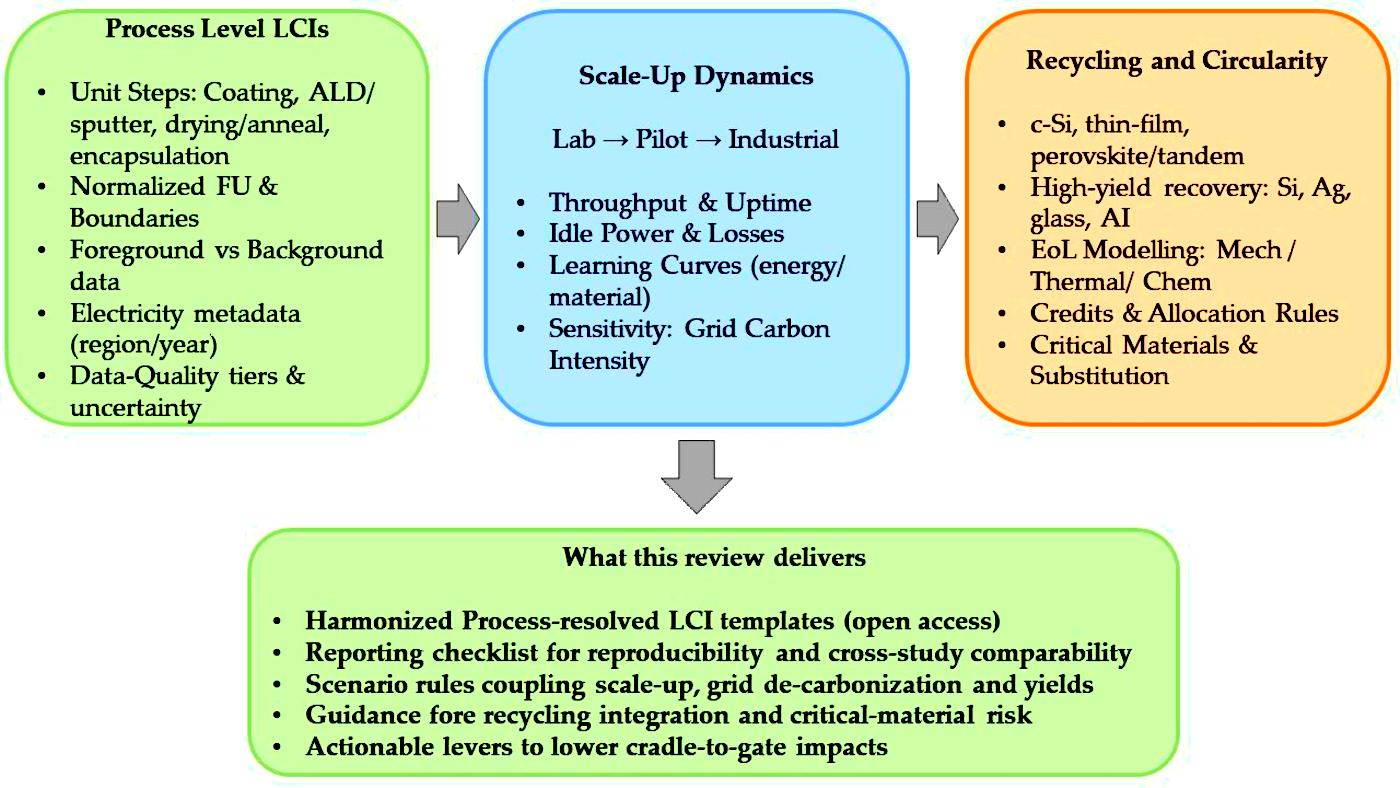

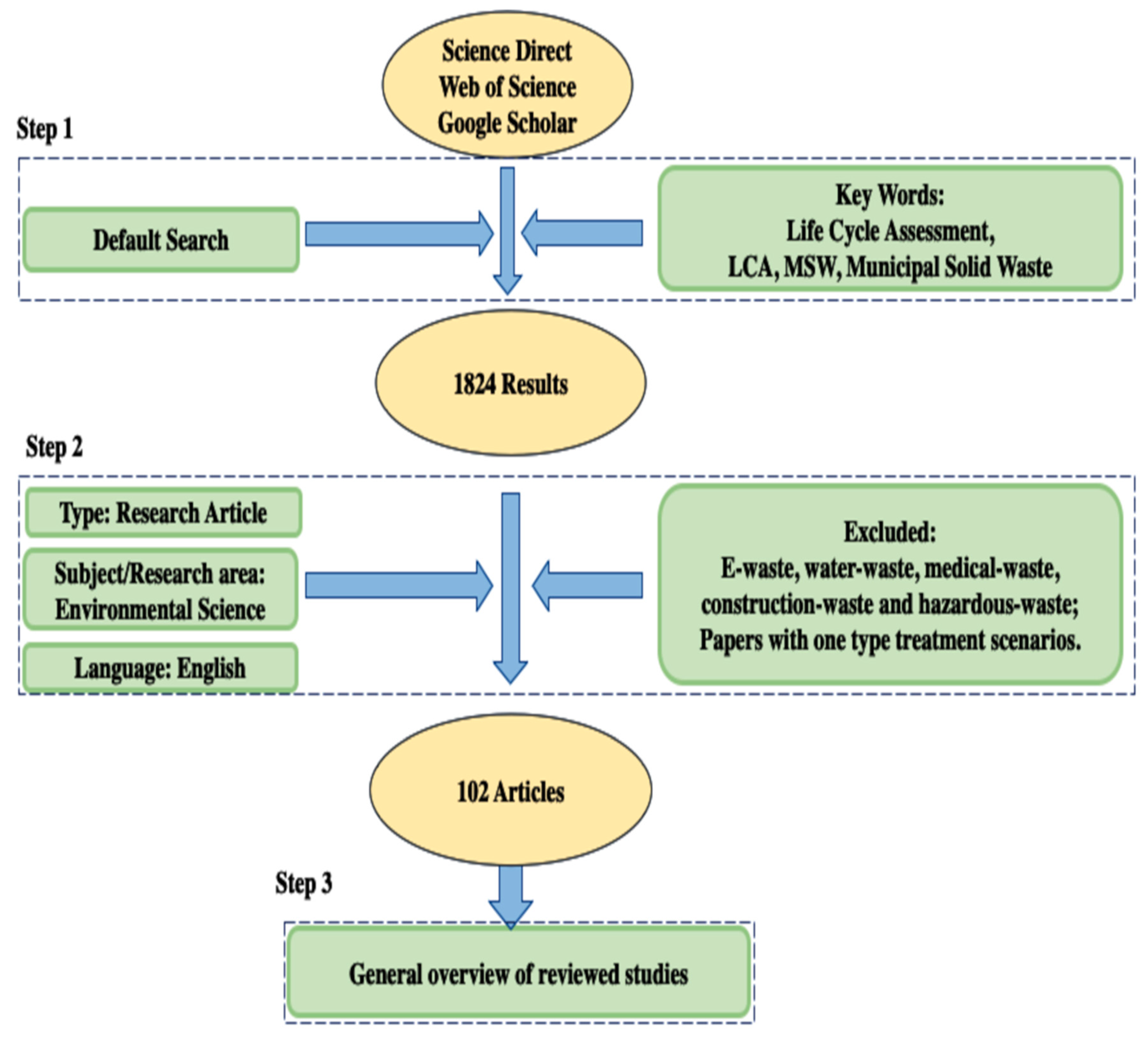

2. Methodology

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

- ‘life cycle assessment’,

- ‘LCA’,

- ‘photovoltaic’,

- ‘solar cell’,

- ‘perovskite’,

- ‘thin-film’,

- ‘roll-to-roll’,

- ‘tandem’,

- ‘manufacturing process’,

- ‘recycling’.

2.2. Selection Criteria

- Publication type: Review and Research article

- Research area: Environmental Science or directly related subfields

- Language: English

- E-waste

- Water-waste

- Medical-waste

- Construction-waste

- Hazardous-waste

2.3. Review Framework

- Technology focus: crystalline silicon, CdTe, CIGS, perovskite, tandem, or hybrid thin-film.;

- Manufacturing process coverage: deposition/coating, encapsulation, substrate preparation, metallization, and recycling;

- Scale and system boundary: laboratory, pilot, or industrial scale;

- Functional unit (FU) and impact categories (e.g., GWP, Cumulative Energy Demand (CED), Acidification Potential (AP), Eutrophication Potential (EP));

- The FU is the quantified reference that defines what exactly is being compared in an LCA. It provides a consistent basis for calculating and normalizing environmental impacts across different technologies, processes, or scales.

- Data source type: experimental, modeled, or hybrid;

- LCA methodology: attributional vs. consequential, LCI data transparency, and software tools used;

- Treatment of end-of-life (EoL) and circularity: recycling scenarios, recovery of critical materials, and reuse routes.

3. Technology and Process Landscape

3.1. Perovskite, Tandem, and Thin-Film Routes: Technical Primer

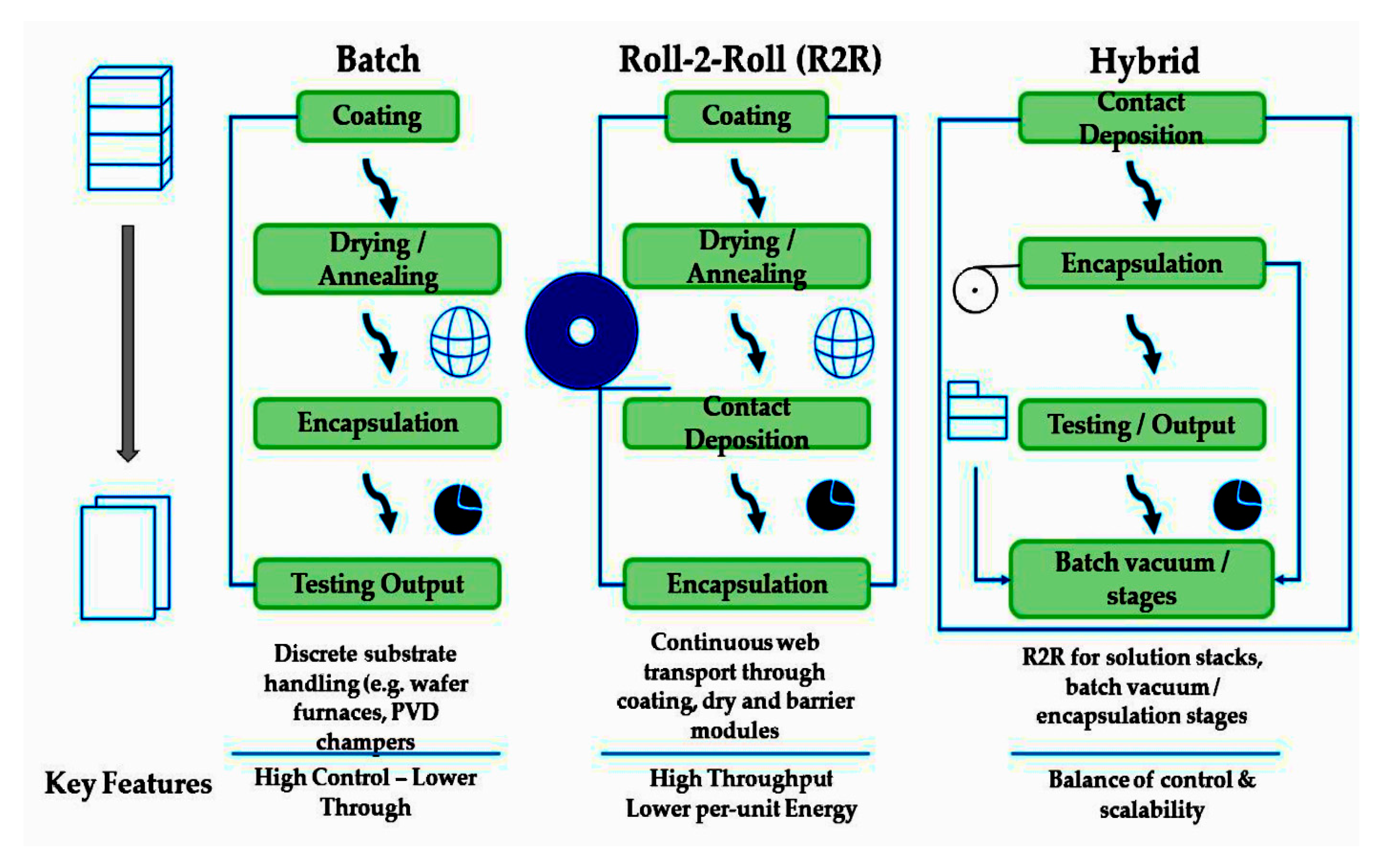

3.2. Unit Operations and Equipment Classes

3.3. Typical Line Configurations

4. Process-Level LCI Compilation and Harmonization

4.1. Normalization Rules (FU, Boundaries, Electricity)

4.2. LCIs by Process Family

4.3. Data-Quality Tiers and Uncertainty Characterization

5. Scale-Up Dynamics and Sensitivity Analysis

5.1. Scaling from Laboratory to Pilot and Industrial Production

5.2. Parameterized Scenarios

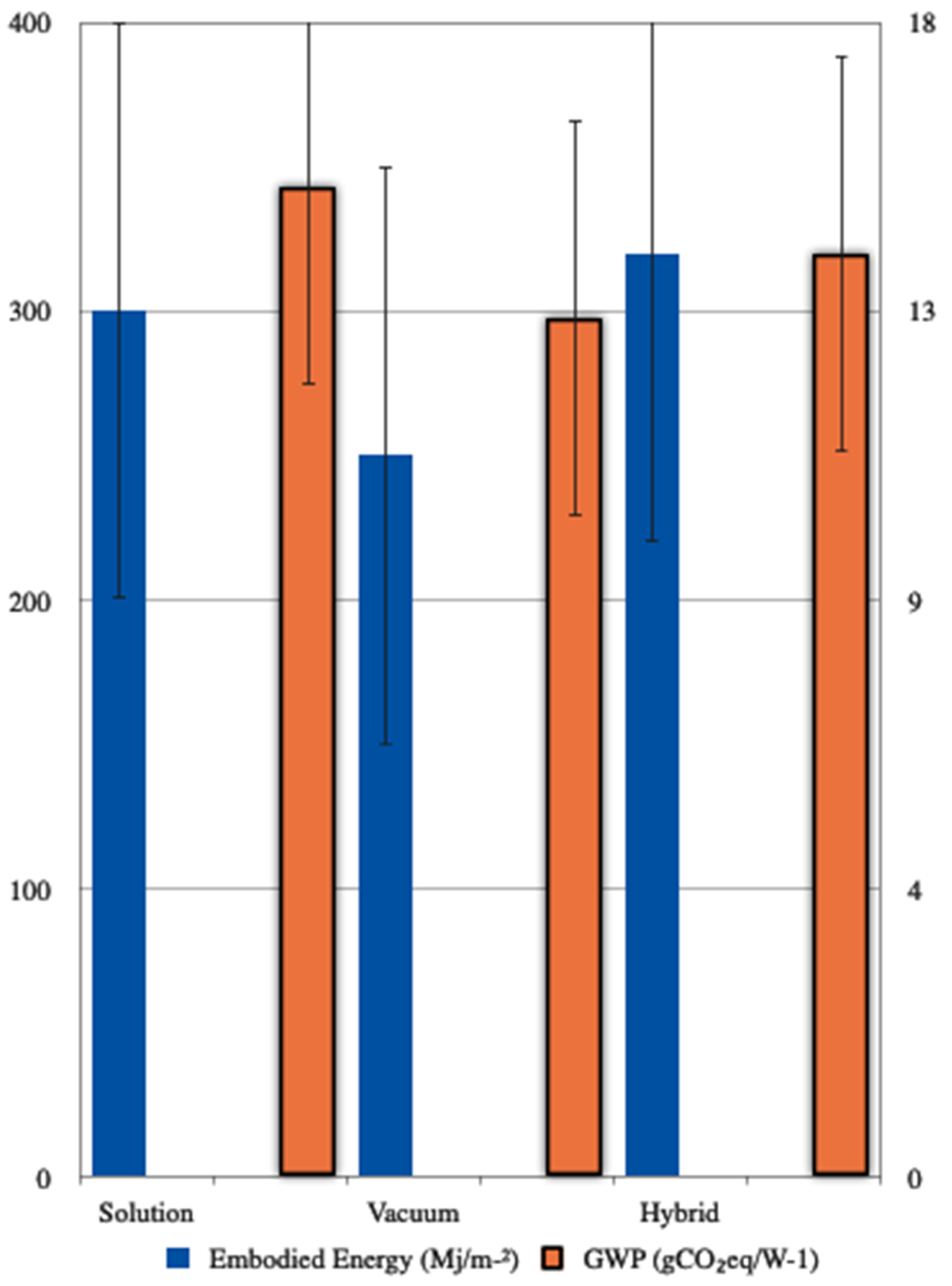

5.3. Comparative Cradle-to-Gate Results Across Routes

6. Recycling, Circularity, and Material Criticality

6.1. EoL Pathways, Recycling and Logistics

6.2. Allocation, Credits and EoL Accounting

6.3. Critical Materials, Scarcity and Substitution

7. Methodological Guidance for Transparent Process-Level LCAs

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALD | Atomic Layer Deposition |

| AP | Acidification Potential (acidifying emissions, e.g., SO₂-eq) |

| BIPV | Building-Integrated Photovoltaic |

| BOS | Balance of System |

| CdTe | Cadmium Telluride |

| CED | Cumulative Energy Demand (total primary energy required) |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CIGS | Copper Indium Gallium Selenide |

| CoV | Coefficients of Variation |

| Cradle-to-gate | Assessment boundary that includes all life-cycle stages from resource extraction (‘cradle’) up to the point where the product leaves the manufacturing facility (‘gate’), excluding use and end-of-life phases. |

| Cradle-to-grave | Assessment boundary that includes the full life cycle of a product, from resource extraction (‘cradle’) through manufacturing, use, and end-of-life treatment (‘grave’). |

| c-Si | Crystalline-silicon |

| EoL | End-of-life |

| EP | Eutrophication Potential (nutrient enrichment impacts, e.g., PO₄³⁻-eq) |

| EPBT | Energy Payback Time |

| FU | Functional Unit |

| GHG | Greenhouse-gas |

| GWP | Global Warming Potential |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| LCIA | Life Cycle Impact Assessment |

| LCI | Life Cycle Inventory |

| OSC | Organic Solar Cells |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| PVPS | Photovoltaic Power Systems Programme |

| PV/T | Photovoltaic/Thermal Hybrid System |

| R2R | Roll-to-Roll (R2R) |

| Si | Silicon |

| TCO | Transparent Conductive Oxide |

| TiO₂ | Titanium Dioxide |

| TRL | Technology Readiness Level |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1: Standardized LCI Data Templates (How to Use)

- VALIDATION: Automated checks for unit consistency, mass/energy balancing, solvent in-out consistency, and flagging of out-of-range values; includes a QA audit log for publication.

- Run consistency checks in VALIDATION, then export machine-readable CSV/JSON and archive the versioned dataset with a DOI.

- Fully versioned background datasets, grid datasets, and template versioning to ensure reproducibility.

- Built-in uncertainty structure using Tiers + stochastic ranges (mean/SD/min/max).

Appendix A.2: Priority Data Gaps and Measurement Needs

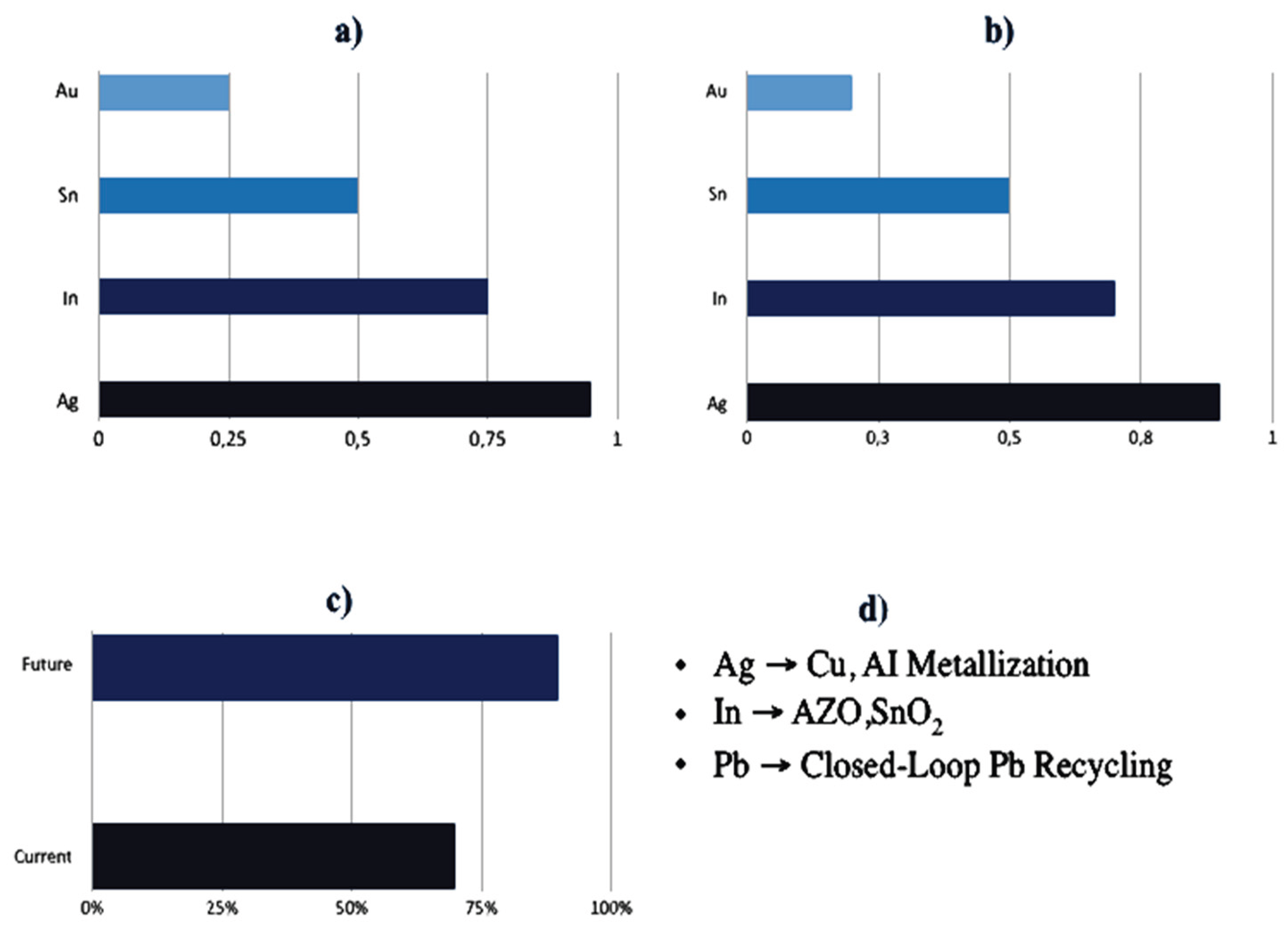

- Critical-materials trajectories and substitution: Ag, In/Sn, Pb, and rare materials require linked supply-risk + LCA modeling tied to realistic manufacturing and regional supply chains [5,19,20,21,22,32,48,70,77,78]. Emission and release-potential studies for third-generation PVs should inform parameterization [100].

Appendix A.3

| Field | Value |

|---|---|

| Project_Title | Perovskite (p-i-n) single-junction module - hybrid line (solution + vacuum) |

| Version | 1.0 (2025-11-10) |

| DOI_or_Repo_Link | |

| Authors | K. Kiskira; N. Gerolimos; G. Priniotakis; D. Nikolopoulos |

| Functional_Unit | 1 m² active area (default) and 1 kWp reported via conversion formulas |

| Active_to_Total_Area_Ratio | 0.9 |

| Module_Efficiency_STC_% | 20 |

| FU_Conversion_Notes | Conversions to kWp use user-specified efficiency (20%) and STC 1000 W/m². |

| System_Boundary | Cradle-to-gate (substrate → coating/deposition → anneal/dry → metallization → encapsulation). |

| Foreground_Included | Substrate cleaning; TCO sputter; ALD barrier; ETL coat; Perovskite coat; HTL coat; Metallization; Encapsulation; QA. |

| Background_Included | Electricity mix; gases; solvents; precursors; transport (default 200 km truck) mapped via BACKGROUND_LINKS. |

| Explicit_Exclusions | Clean-room HVAC (if site-wide), building works, spare parts outside scheduled maintenance, R&D scrap. |

| Baseline_Grid_Region | EU-27 |

| Baseline_Grid_Year | 2023 |

| Background_DB | Ecoinvent/GaBi (placeholder names) |

| DB_Version | v3.x/2024 equivalent |

| TRL | Pre-industrial/pilot (Tier 1-2 blend) |

| Geography_of_Manufacturing | EU (pilot line) |

| Citation_Primary | See manuscript bibliography IDs [12,15,16,17,33,41,43,49] |

| Notes | Numbers are representative within literature ranges; replace with site data when available. |

| HEAT_RECOVERY_FACTOR | 0.2 |

| GLASS_MASS_kg_per_m2 | 12 |

| ENCAPSULANT_kg_per_m2 | 0.6 |

| Unit_Operation | Equipment_Class | Tool_ID | Routing | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate wash and prep | wet | SUB-CLN-01 | batch | Glass soda-lime 3.2 mm; DI water; detergents |

| TCO sputter (ITO/AZO) | vacuum | TCO-SPT-01 | batch | DC sputter; Ar |

| ALD barrier (optional) | vacuum | ALD-BAR-01 | batch | Al₂O₃/HfO₂; H₂O |

| ETL slot-die coat | wet | ETL-SD-01 | R2R | SnO₂ dispersion; low-tox solvent |

| Perovskite slot-die coat | wet | PVK-SD-01 | R2R | p-i-n inks; greener solvent mix |

| Anneal/dry (IR/air) | thermal | ANN-OVN-01 | R2R | IR + air knife; heat recovery |

| HTL slot-die coat | wet | HTL-SD-01 | R2R | Polymer HTL ink |

| Metallization (screen/ink) | ambient | MET-PRT-01 | batch | Ag or Cu grid; low Ag route |

| Encapsulation and lamination | thermal | ENC-LAM-01 | batch | Glass-glass; POE/EVA |

| End-of-line test and QA | ambient | QA-VIS-01 | batch | EL test; visual |

| Process_Step | Substrate Wash & Prep | TCO Sputter (ITO/AZO) | ALD Barrier (Optional) | ETL Slot-die Coat | Perovskite Slot-die Coat | Anneal/Dry (IR/Air) | HTL Slot-die Coat | Metallization (Screen/Ink) | Encapsulation & Lamination | End-of-Line Test & QA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equipment_Class | wet | vacuum | vacuum | wet | wet | thermal | wet | ambient | thermal | ambient |

| TRL | Pilot | Pilot | Pilot | Pilot | Pilot | Pilot | Pilot | Pilot | Pilot | Pilot |

| Area_Pass_m2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Throughput_m2_h | 20 | 15 | 10 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 20 | 15 | 15 |

| Uptime_% | 90 | 92 | 92 | 90 | 90 | 92 | 92 | 93 | 95 | 95 |

| Yield_% | 95 | 95 | 95 | 97 | 95 | 96 | 97 | 98 | 99 | 99 |

| Active_Time_min | 6 | 12 | 10 | 5 | 8 | 15 | 5 | 4 | 12 | 3 |

| Idle_Power_kW | 1 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Active_Power_kW | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1.2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0.8 | 3.5 | 0.3 |

| Electricity_kWh | 0.2 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.083333333 | 0.053333333 | 0.7 | 0.016666667 |

| Electricity_GWP_Gco2 | 540 | 1350 | 810 | 324 | 810 | 1080 | 270 | 216 | 945 | 81 |

| Thermal_Energy_MJ | 0 | 0.648550725 | 0.251086957 | 0.389 | 0.948 | 1.229347826 | 0.318448068 | 0.168309677 | 0.505964912 | 0.046896199 |

| Solvent_kg | 0.18 | 0.94 | 0.47 | 0.10 | 0.41 | 0.97 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.66 | 0.02 |

| Recovery_Eff_% | 0.00 | 5.14 | 2.39 | 7.55 | 11.25 | 7.86 | 6.18 | 4.12 | 4.18 | 1.55 |

| Gases_kg | 1.096842105 | 4.553240643 | 2.628931501 | 0.869647508 | 2.880373614 | 9.87740078 | 0.861910737 | 0.706690932 | 7.954427786 | 0.485529374 |

| Substrate_kg | 0.003644662 | 2.560429861 | 1.43419999 | 3.762090367 | 4.444846327 | 2.98151514 | 3.081433262 | 1.543336947 | 1.234734021 | 0.515569574 |

| Encapsulant_kg | 10.96840995 | 22.59551223 | 15.72605532 | 10.79954858 | 21.89624214 | 38.60583249 | 10.57144961 | 10.65786226 | 39.30444687 | 8.740303549 |

| Waste_kg | #DIV/0! | 5.468334561 | 3.482187809 | 1.069120146 | 2.713238252 | 8.289876321 | 0.913962715 | 0.596399308 | 6.755294886 | 0.249786594 |

| Notes | DI water recirc; mild detergent | Ar purge ~0.05 kg/m² | Al2O3 ~30 nm equiv. | Low-tox carrier; recovery 80% | Greener solvent blend; 85% recovery | IR anneal; heat recovery factor ~0.2 | Polymer HTL; 80% recovery | Low-Ag formulation ~1.5 g/m² | Glass-glass; POE/EVA ~0.6 kg/m² | EL imaging; visual |

| Tier | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Dist_Type | lognormal | lognormal | lognormal | lognormal | lognormal | lognormal | lognormal | lognormal | lognormal | lognormal |

| Mean | ||||||||||

| SD | ||||||||||

| Min | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| Max | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Time_Check | CHECK ACTIVE TIME | CHECK ACTIVE TIME | CHECK ACTIVE TIME | CHECK ACTIVE TIME | CHECK ACTIVE TIME | CHECK ACTIVE TIME | CHECK ACTIVE TIME | CHECK ACTIVE TIME | CHECK ACTIVE TIME |

| Dataset_Name | Database | Region | Year | Dataset_ID | Transport | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity, medium voltage, EU-27, 2023 | ecoinvent | EU-27 | 2023 | elec_mv_eu27_2023 | 0 km | Used for all electricity entries |

| Argon, at plant | ecoinvent | GLO | 2020 | argon_at_plant | 500 km truck | Sputtering purge gas |

| Al₂O₃ ALD precursor, at plant | ecoinvent | GLO | 2020 | ald_alumina_precursor | 300 km truck | Placeholder; adjust to actual |

| Glass, soda-lime, 3.2 mm, at plant | ecoinvent | RER | 2020 | glass_32mm | 200 km truck | Front/back glass |

| Encapsulant, POE/EVA, at plant | ecoinvent | GLO | 2020 | encapsulant_poe_eva | 300 km truck | POE/EVA film |

| Silver paste, at plant | ecoinvent | GLO | 2020 | silver_paste_lowAg | 1000 km truck | Low-Ag paste |

| Detergent, industrial, at plant | ecoinvent | GLO | 2020 | detergent_industrial | 200 km truck | Substrate cleaning |

| DI water, at plant | ecoinvent | RER | 2020 | di_water | Onsite | Closed-loop recirculation |

| Scenario | gCO₂_per_kWh |

|---|---|

| EU-27 baseline 2023 | 270 |

| EU-27 2030 projection | 150 |

| EU-27 2050 net-zero projection | 50 |

| Custom_User | 0 |

| Process_Step | Tier | Source_Type | Vintage | Uncertainty_Band | Pedigree | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate wash & prep | 1 | Primary pilot logs | 2024–2025 | ±20% | Good | Measured power and duty cycles |

| TCO sputter (ITO/AZO) | 2 | Scaled from tool specs + literature | 2020–2025 | ±30% | Medium | Throughput-sensitive |

| ALD barrier | 2 | Literature + vendor models | 2020–2024 | ±35% | Medium | Optional step |

| ETL coat | 2 | Pilot measurements + model | 2023–2025 | ±25% | Good | Solvent balance checked |

| Perovskite coat | 2 | Pilot measurements + model | 2023–2025 | ±30% | Good | Recovery efficiency critical |

| Anneal/dry | 2 | Measured furnace/IR logs | 2024–2025 | ±25% | Good | Heat-recovery assumed 0.2 |

| HTL coat | 2 | Pilot + model | 2023–2025 | ±25% | Good | Solvent balance checked |

| Metallization | 2 | Vendor + line data | 2023–2025 | ±20% | Good | Low-Ag recipe |

| Encapsulation | 1 | Plant recipe + datasheets | 2024–2025 | ±15% | High | Glass & POE mass measured |

| QA | 1 | Plant logs | 2024–2025 | ±10% | High | Minor energy share |

| Scenario | Allocation | Si_Recovered | Pb_Recovered | Glass_Recovered | Al_Recovered | Ag_Recovered | Polymer_Recovered | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (mechanical+thermal) | mass | 0 | 0 | 0.9 | 0.85 | 0 | 0.95 | EU logistics; 200 km avg |

| Closed-loop enhanced (hydrometallurgical metals) | system_expansion | 0 | 0 | 0.95 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.97 | Credits for Ag; foil recovery if present |

| Landfill (counterfactual) | none | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | For sensitivity only |

| Unit_Operation | Equipment_Class | Tool_ID | Routing | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate wash and prep | wet | SUB-CLN-01 | batch | Glass soda-lime 3.2 mm; DI water; detergents |

| TCO sputter (ITO/AZO) | vacuum | TCO-SPT-01 | batch | DC sputter; Ar |

| ALD barrier (optional) | vacuum | ALD-BAR-01 | batch | Al₂O₃/HfO₂; H₂O |

| ETL slot-die coat | wet | ETL-SD-01 | R2R | SnO₂ dispersion; low-tox solvent |

| Perovskite slot-die coat | wet | PVK-SD-01 | R2R | p-i-n inks; greener solvent mix |

| Anneal/dry (IR/air) | thermal | ANN-OVN-01 | R2R | IR + air knife; heat recovery |

| HTL slot-die coat | wet | HTL-SD-01 | R2R | Polymer HTL ink |

| Metallization (screen/ink) | ambient | MET-PRT-01 | batch | Ag or Cu grid; low Ag route |

| Encapsulation and lamination | thermal | ENC-LAM-01 | batch | Glass-glass; POE/EVA |

| End-of-line test and QA | ambient | QA-VIS-01 | batch | EL test; visual |

| Check | Value | Status | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity total (kWh) | 4.05 | INFO | Sum over FOREGROUND_LCI |

| Thermal energy total (MJ) | 4.51 | INFO | Sum over FOREGROUND_LCI |

| Solvent in (kg) | 3.88 | INFO | Sum over coating steps |

| Solvent recovered (kg) | 22.44 | INFO | Recovery_Eff_% applied |

| Solvent loss (kg) | 3.66 | INFO | Should be >0 and reasonable |

| - | - | - | - |

| EU-27 baseline 2023 | - | - | - |

| Active_CO₂_Factor_(g_per_kWh) | 270 | - | - |

| Total_Electricity_GWP_(gCO₂) | 6426 | - | Electricity × factor |

| TOTAL GWP from electricity (kg CO₂) | 6.426 | INFO | =6426/1000 |

| Solvent recovery check (%) | 577.7 | INFO | =B5/B4 × 100 |

References

- Fraunhofer ISE; PSE Projects GmbH. Photovoltaics Report — updated: 31 October 2025. Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems ISE: Freiburg, Germany; PSE Projects GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2025; Available online: https://www.ise.fraunhofer.de/content/dam/ise/de/documents/publications/studies/Photovoltaics-Report.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Liu, J.; Shen, X. Global PV Supply Chains: Costs and Energy Savings, GHG Emissions Reductions. Energy Policy 2025, 205, 114716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frischknecht, R.; Stolz, P.; Krebs, L.; de Wild-Scholten, M.; Sinha, P.; Fthenakis, V.; Kim, H.C.; Raugei, M.; Stucki, M. Life Cycle Inventories and Life Cycle Assessment of Photovoltaic Systems. International Energy Agency (IEA) PVPS Task 12, Report T12-19:2020; IEA PVPS: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, R.; Sayer, M.; Ajanovic, A.; Auer, H. Technological Learning: Lessons Learned on Energy Technologies. WIREs Energy Environ. 2022, 11, e463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallam, B.; Kim, M.; Zhang, Y.; Dias, P.; Candelise, C.; Green, M.A. The Silver Learning Curve for Photovoltaics and Projected Silver Demand for Net-Zero Emissions by 2050. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2023, 31, 598–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldschmidt, J.C.; Wagner, L.; Pietzcker, R.; Friedrich, L. Technological Learning for Resource Efficient Terawatt Scale Photovoltaics. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 5147–5160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.-A.; Grand, P.-P. Diversifying the Solar Photovoltaic Supply Chain to Secure Europe’s Energy and Climate Roadmap and Sovereignty. iScience 2025, 33, 112751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, N.; Espinosa, N. Preparatory Study for Solar Photovoltaic Modules, Inverters and Systems - Task 4: Technical Analysis Including End-of-Life; European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC): Ispra, Italy, 2018. Available online: https://susproc.jrc.ec.europa.eu/product-bureau/sites/default/files/contentype/product_group_documents/1581689975/DraftReport_Task5.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Muteri, V.; Cellura, M.; Curto, D.; Franzitta, V.; Longo, S.; Mistretta, M.; Parisi, M.L. Review on Life Cycle Assessment of Solar Photovoltaic Panels. Energies 2020, 13, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milousi, M.; Souliotis, M.; Arampatzis, G.; Papaefthimiou, S. Evaluating the Environmental Performance of Solar Energy Systems through a Combined Life Cycle Assessment and Cost Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashedi, A.; Khanam, T. Life Cycle Assessment of Most Widely Adopted Solar Photovoltaic Energy Technologies by Mid-Point and End-Point Indicators of ReCiPe Method. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 29075–29090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberola-Borràs, J.-A.; Baker, J.A.; De Rossi, F.; Vidal, R.; Beynon, D.; Hooper, K.E.A.; Watson, T.M.; Mora-Seró, I. Perovskite Photovoltaic Modules: Life Cycle Assessment of Pre-Industrial Production Process. iScience 2018, 9, 542–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, H.K.R.; Gemechu, E.; Thakur, U.; Shankar, K.; Kumar, A. Techno-Economic Assessment of Titanium Dioxide Nanorod-Based Perovskite Solar Cells: From Lab-Scale to Large-Scale Manufacturing. Appl. Energy 2021, 298, 117251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Príncipe, J.; Andrade, L.; Mata, T.M.; Martins, A.A. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Perovskite Solar Cell Production: Mesoporous n-i-p versus Inverted p-i-n Architectures. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2025, 6, 2400368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, V.C.M.; Andrade, L. Recent Advancements on Slot-Die Coating of Perovskite Solar Cells: The Lab-to-Fab Optimisation Process. Energies 2024, 17, 3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Oluk, I.; Jung, M.; Tseng, S.; Byrne, D.M.; Harris, T.A.L.; Escobar, I.C. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment for the Fabrication of Polysulfone Membranes Using Slot Die Coating as a Scalable Fabrication Technique. Polymers 2025, 17, 2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, M.; Boysen, N.; Graniel, O.; Sekkat, A.; Dussarrat, C.; Wiff, P.; Devi, A.; Muñoz-Rojas, D. Assessing the Environmental Impact of Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD) Processes and Pathways to Lower It. ACS Mater. Au 2023, 3, 274–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Kajal, P.; Dhar, A.; Mathews, N.; Boix, P.P.; Powar, S. Reduced Global Warming Potential in Carbon-Based Perovskite Solar Modules: Cradle-to-Gate Life Cycle Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 426, 139136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, R.; Alberola-Borràs, J.-A.; Sánchez-Pantoja, N.; Mora-Seró, I. Comparison of Perovskite Solar Cells with Other Photovoltaic Technologies from the Point of View of Life Cycle Assessment. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2021, 2, 2000088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhati, N.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Maréchal, F. Environmental Impacts as the Key Objectives for Perovskite Solar Cells Optimization. Energy 2024, 299, 131492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leccisi, E.; Fthenakis, V. Life-Cycle Environmental Impacts of Single-Junction and Tandem Perovskite PVs: A Critical Review and Future Perspectives. Prog. Energy 2020, 2, 032002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, W.; Li, X.; Ahmed, S.; Ouyang, Z.; Li, G. A Review of Life Cycle Assessment and Sustainability Analysis of Perovskite/Si Tandem Solar Cells. RSC Sustain. 2025, 3, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marson, A.; Benozzi, A.; Manzardo, A. Looking to the Future: Prospective Life Cycle Assessment of Emerging Technologies. Chem. Eur. J. 2025, 31, e202500304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Hulst, M.K.; Hauck, M.; Hoeks, S.; van Zelm, R.; Huijbregts, M.A.J. Learning Curves in Prospective Life Cycle Assessment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 16501–16512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallam, B.; Kim, M.; Underwood, R.; Drury, S.; Wang, L.; Dias, P. A Polysilicon Learning Curve and the Material Requirements for Broad Electrification with Photovoltaics by 2050. Solar RRL 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erakca, M.; Baumann, M.; Helbig, C.; Weil, M. Systematic Review of Scale-Up Methods for Prospective Life Cycle Assessment of Emerging Technologies. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 451, 142161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latunussa, C.E.L.; Ardente, F.; Blengini, G.A.; Mancini, L. Life Cycle Assessment of an Innovative Recycling Process for Crystalline Silicon Photovoltaic Panels. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 156, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansanelli, G.; Fiorentino, G.; Tammaro, M.; Zucaro, A. A Life Cycle Assessment of a Recovery Process from End-of-Life Photovoltaic Panels. Appl. Energy 2021, 290, 116727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiandra, V.; Sannino, L.; Andreozzi, C.; Graditi, G. End-of-Life of Silicon PV Panels: A Sustainable Materials Recovery Process. Waste Manag. 2019, 84, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiho, A.; Suwa, I.; Dou, Y.; Lim, S.; Namihira, T.; Koita, T.; Mochidzuki, K.; Murakami, S.; Daigo, I.; Tokoro, C.; et al. Prospective Life Cycle Assessment of Recycling Systems for Spent Photovoltaic Panels by Combined Application of Physical Separation Technologies. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 192, 106922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klugmann-Radziemska, E.; Kuczyńska-Łażewska, A. The Use of Recycled Semiconductor Material in Crystalline Silicon Photovoltaic Modules Production—A Life Cycle Assessment of Environmental Impacts. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2020, 205, 110259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martulli, A.; Gota, F.; Rajagopalan, N.; Meyer, T.; Ramirez Quiroz, C.O.; Costa, D.; Paetzold, U.W.; Malina, R.; Vermang, B.; Lizin, S. Beyond Silicon: Thin-Film Tandem as an Opportunity for Photovoltaics Supply Chain Diversification and Faster Power System Decarbonization out to 2050. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2025, 279, 113212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psomopoulos, C.S.; Kalkanis, K.; Chatzistamou, E.D.; Kiskira, K.; Ioannidis, G.C.; Kaminaris, S.D. End-of-Life Treatment of Photovoltaic Panels: Expected Volumes up to 2045 in the E.U. AIP Conf. Proc. 2022, 2437, 020084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardente, F.; Latunussa, C.E.L.; Blengini, G.A. Resource Efficient Recovery of Critical and Precious Metals from Waste Silicon PV Panel Recycling. Waste Manag. 2019, 91, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaosukho, S.; Meeklinhom, S.; Rodbuntum, S.; Sukgorn, N.; Kaewprajak, A.; Kumnorkaew, P.; Varabuntoonvit, V. Life Cycle Assessment of Perovskite Solar Cells with Alternative Carbon Electrode. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 106, 107462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, M.; Yang, H. A Review of the Energy Performance and Life-Cycle Assessment of Building-Integrated Photovoltaic (BIPV) Systems. Energies 2018, 11, 3157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudais, B.; Ben Ahmed, H.; Jodin, G.; Degrenne, N.; Lefebvre, S. Life Cycle Assessment of a 150 kW Electronic Power Inverter. Energies 2023, 16, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourtsalas, A.C.; Papadatos, P.E.; Kiskira, K.; Kalkanis, K.; Psomopoulos, C.S. Ecodesign for Industrial Furnaces and Ovens: A Review of the Current Environmental Legislation. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkanis, K.; Kiskira, K.; Papageorgas, P.; Kaminaris, S.D.; Piromalis, D.; Banis, G.; Mpelesis, D.; Batagiannis, A. Advanced Manufacturing Design of an Emergency Mechanical Ventilator via 3D Printing—Effective Crisis Response. Sustainability 2023, 15(4), 2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs-Moberg, M.; Pitz, M.; Dorsette, T.L.; Gheewala, S.H. Third Generation of Photovoltaic Panels: A Life Cycle Assessment. Renew. Energy 2021, 164, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moein-Jahromi, M.; Rahmanian-Koushkaki, H.; Rahmanian, S.; Pilban Jahromi, S. Evaluation of Nanostructured GNP and CuO Compositions in PCM-Based Heat Sinks for Photovoltaic Systems. J. Energy Storage 2022, 53, 105240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.; Rotondi, L.; Stefanelli, M.; Parisi, M.L. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Different Fabrication Processes for Perovskite Solar Mini-Modules. EPJ Photovolt. 2024, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzisideris, M.D.; Ohms, P.K.; Espinosa, N.; Krebs, F.C.; Laurent, A. Economic and Environmental Performances of Organic Photovoltaics with Battery Storage for Residential Self-Consumption. Appl. Energy 2019, 256, 113977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souliotis, M.; Arnaoutakis, N.; Panaras, G.; Kavga, A.; Papaefthimiou, S. Experimental Study and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Hybrid Photovoltaic/Thermal (PV/T) Solar Systems for Domestic Applications. Renew. Energy 2018, 126, 708–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad Ludin, N. Economic and Life Cycle Analysis of Photovoltaic Systems in the APEC Region towards a Low-Carbon Society; Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC), Solar Energy Research Institute (SERI), National University of Malaysia (UKM): Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2019. APEC Project EWG 06 2017A; APEC Secretariat: Singapore. Available online: https://www.apec.org/docs/default-source/Publications/2019/4/Life-Cycle-Assessment-of-Photovoltaic-Systems-in-the-APEC-Region/219_EWG_Life-Cycle-Assessment-of-Photovoltaic-Systems-in-the-APEC-Region.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Jones, C.; Gilbert, P.; Raugei, M.; Mander, S.; Leccisi, E. An Approach to Prospective Consequential Life Cycle Assessment and Net Energy Analysis of Distributed Electricity Generation. Energy Policy 2017, 100, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maranghi, S.; Parisi, M.L.; Basosi, R.; Sinicropi, A. Environmental Profile of the Manufacturing Process of Perovskite Photovoltaics: Harmonization of Life Cycle Assessment Studies. Energies 2019, 12, 3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.L.; Sekar, A.; Mirletz, H.; Heath, G.; Margolis, R. An Updated Life Cycle Assessment of Utility-Scale Solar Photovoltaic Systems Installed in the United States; National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2024; NREL/TP-7A40-87372. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy24osti/87372.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Kiskira, K.; Kalkanis, K.; Coelho, F.; Plakantonaki, S.; D’onofrio, C.; Psomopoulos, C.S.; Priniotakis, G.; Ioannidis, G.C. Life Cycle Assessment of Organic Solar Cells: Structure, Analytical Framework, and Future Product Concepts. Electronics 2025, 14, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmati, M.; Bayati, N.; Ebel, T. Integrated Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment with Future Energy Mix: A Review of Methodologies for Evaluating the Sustainability of Multiple Power Generation Technologies Development. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 49, 100581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebian, S.H.; Balouchi, H.; Esazadeh, D.; Abbasi, M.; Azizi, H. An Environmental-Economic Analysis of a Case Solar Power Plant for Power Decarbonization. Energy Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 3541–3550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, X.; Yuan, Z. Life-Cycle Assessment of Multi-Crystalline Photovoltaic (PV) Systems in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 86, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa Guerrero, N.B.; Herrera Martínez, W.O.; Civit, B.; Perez, M.D. Energy Performance of Perovskite Solar Cell Fabrication in Argentina: A Life Cycle Assessment Approach. Sol. Energy 2021, 230, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Guo, F.; Gardy, J.; Xu, G.; Li, X.; Jiang, X. Life Cycle Assessment of Polysilicon Photovoltaic Modules with Green Recycling Based on the ReCiPe Method. Renew. Energy 2024, 236, 121407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, M.; Yu, Z.; Ma, W.; Li, L.; Zhang, J. Life Cycle Assessment of Crystalline Silicon Wafers for Photovoltaic Power Generation. Silicon 2021, 13, 3177–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.; Friedrich, L.; Reichel, C.; Herceg, S.; Mittag, M.; Neuhaus, D.H. A Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Silicon PV Modules: Impact of Module Design, Manufacturing Location and Inventory. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2021, 230, 111277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Y.; Wang, P.; Wang, Y.; Qiao, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Environmental Effects Evaluation of Photovoltaic Power Industry in China on Life Cycle Assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoyo-Castelazo, E.; Solano-Olivares, K.; Martínez, E.; García, E.O.; Santoyo, E. Life Cycle Assessment for a Grid-Connected Multi-Crystalline Silicon Photovoltaic System of 3 kWp: A Case Study for Mexico. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 316, 128314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarkos, N.; Menti, A.; Kalkanis, K.; Chronis, I.; Psomopoulos, C.S. Impact Assessment of Photovoltaic Panels with Life Cycle Analysis Techniques. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 101071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracquene, E.; Peeters, J.R.; Dewulf, W.; Duflou, J.R. Taking Evolution into Account in a Parametric LCA Model for PV Panels. Procedia CIRP 2018, 69, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Mitchell, C.R.; Mo, W. Dynamic Life Cycle Economic and Environmental Assessment of Residential Solar Photovoltaic Systems. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 722, 137932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alevizos, V.; Gerolimos, N.; Leligkou, E.A.; Hompis, G.; Priniotakis, G. Sustainable Swarm Intelligence: Assessing Carbon-Aware Optimization in High-Performance AI Systems. Technologies 2025, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alevizos, V.; Gerolimos, N.; Yue, Z.; Edralin, S.; Xu, C.; Papakostas, G.A. Advanced Graph–Physics Hybrid Framework (AGPHF) for Holistic Integration of AI-Driven Graph- and Physics-Methodologies to Promote Resilient Wastewater Management in Dynamic Real Environments. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badza, K.; Soro, Y.M.; Sawadogo, M. Life Cycle Assessment of a 33.7 MW Solar Photovoltaic Power Plant in the Context of a Developing Country. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2023, 33, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Xie, L.; Zeng, X.; Zhong, J.; Zhao, O.; Yang, K.; Li, Z.; Zou, R.; et al. Carbon Reduction Measures-Based Life Cycle Assessment of the Photovoltaic-Supported Sewage Treatment System. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 101, 105074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusenza, M.A.; Guarino, F.; Longo, S.; Mistretta, M.; Cellura, M. Environmental Assessment of 2030 Electricity Generation Scenarios in Sicily: An Integrated Approach. Renew. Energy 2020, 160, 1148–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, C.; Marmiroli, B.; Carvalho, M.L.; Girardi, P. Life Cycle Assessment of Photovoltaic Electricity Production in Italy: Current Scenario and Future Developments. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 852, 174846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores Cayuela, J.A.; Mérida García, A.; Fernández García, I.; Rodríguez Díaz, J.A. Life Cycle Assessment of Large-Scale Solar Photovoltaic Irrigation. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisi, M.L.; Maranghi, S.; Vesce, L.; Sinicropi, A.; Di Carlo, A.; Basosi, R. Prospective Life Cycle Assessment of Third-Generation Photovoltaics at the Pre-Industrial Scale: A Long-Term Scenario Approach. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 121, 109703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Hulst, M.K.; Magoss, D.; Massop, Y.; Veenstra, S.; van Loon, N.; Dogan, I.; Coletti, G.; Theelen, M.; Hoeks, S.; Huijbregts, M.A.J.; et al. Comparing Environmental Impacts of Single-Junction Silicon and Silicon/Perovskite Tandem Photovoltaics—A Prospective Life Cycle Assessment. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 8860–8870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celik, I.; Lunardi, M.; Frederickson, A.; Corkish, R. Sustainable End-of-Life Management of Crystalline Silicon and Thin Film Solar Photovoltaic Waste: The Impact of Transportation. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanailidis, V.I.; Rentoumis, G.M.; Katsigiannis, A.Y.; Bilalis, N. Integration and Assessment of Recycling into c-Si Photovoltaic Module’s Life Cycle. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2018, 11, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeumo, M.F.; Germana, C.; Ippolito, N.M.; Franco, M.; Piga, L.; Santilli, S. Photovoltaic Module Recycling: A Physical and a Chemical Recovery Process. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2019, 193, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Koch, T.W.; Volk, T.A.; Malmsheimer, R.W.; Eisenbies, M.H.; Kloster, D.; Brown, T.R.; Naim, N.; Therasme, O. The Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Electricity Production in New York State from Distributed Solar Photovoltaic Systems. Energies 2022, 15, 7278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevala, S.-M.; Hamuyuni, J.; Junnila, T.; Sirviö, T.; Eisert, S.; Wilson, B.P.; Serna-Guerrero, R.; Lundström, M. Electro-Hydraulic Fragmentation vs. Conventional Crushing of Photovoltaic Panels—Impact on Recycling. Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Bae, J.; Han, J. Economic and Environmental Feasibility Evaluation Study of Hydrometallurgical Recycling Methods for Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 489, 144651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Lonergan, K.E.; Sansavini, G. Policy-Driven Transformation of Global Solar PV Supply Chains and Resulting Impacts. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, D.; Yang, S.; Ma, L.; Ma, W.; Yu, Z.; Xi, F.; Yu, J. Overview of Life Cycle Assessment of Recycling End-of-Life Photovoltaic Panels: A Case Study of Crystalline Silicon Photovoltaic Panels. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plakantonaki, S.; Stergiou, M.; Panagiotatos, G.; Kiskira, K.; Priniotakis, G. Regenerated Cellulosic Fibers from Agricultural Waste. AIP Conf. Proc. 2022, 2430, 080006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plakantonaki, S.; Kiskira, K.; Zacharopoulos, N.; Belessi, V.; Sfyroera, E.; Priniotakis, G.; Athanasekou, C. Investigating the Routes to Produce Cellulose Fibers from Agro-Waste: An Upcycling Process. ChemEngineering 2024, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Elgowainy, A.; Lu, Z.; Kelly, J.C.; Wang, M.; Boardman, R.D.; Marcinkoski, J. Greenhouse Gas Emissions Embodied in the U. S. Solar Photovoltaic Supply Chain. Environ. Res. Lett. 2023, 18(10), 104012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; You, F. Reshoring Silicon Photovoltaics Manufacturing Contributes to Decarbonization and Climate Change Mitigation. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Navarro, T.; Stascheit, C.; Díaz-Bello, D.; Döll, J.; Neugebauer, S.; Sonnemann, G. An Agile Life Cycle Assessment for the Deployment of Photovoltaic Energy Systems in the Built Environment. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2024, 14, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, E.; Heidari, A. Development of an Integrated Tool Based on Life Cycle Assessment, Levelized Energy, and Life Cycle Cost Analysis to Choose Sustainable Façade Integrated Photovoltaic Systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Gallardo, J.R.; Azzaro-Pantel, C.; Astier, S. Combining Multi-Objective Optimization, Principal Component Analysis and Multiple Criteria Decision Making for Ecodesign of Photovoltaic Grid-Connected Systems. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2018, 27, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.H.; Bareschino, P.; Mancusi, E.; Pepe, F. Environmental Life Cycle Analysis and Energy Payback Period Evaluation of Solar PV Systems: The Case of Pakistan. Energies 2023, 16, 6400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Ma, L.; Yang, Y.; Fan, M.; Ma, W.; Fu, L.; Li, M. A Life Cycle Assessment of Hydropower-Silicon-Photovoltaic Industrial Chain in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunardi, M.M.; Alvarez-Gaitan, J.P.; Bilbao, J.I.; Corkish, R. A Review of Recycling Processes for Photovoltaic Modules. In Solar Panels and Photovoltaic Materials; Zaidi, B., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maani, T.; Celik, I.; Heben, M.J.; Ellingson, R.J.; Apul, D. Environmental Impacts of Recycling Crystalline Silicon (c-Si) and Cadmium Telluride (CdTe) Solar Panels. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 735, 138827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Stranks, S.D.; You, F. Life Cycle Assessment of Recycling Strategies for Perovskite Photovoltaic Modules. University of Cambridge, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Oberbeck, L.; Marchand Lasserre, M.; Perez-Lopez, P. Modelling Recycling for the Life Cycle Assessment of Perovskite/Silicon Tandem Modules. EPJ Photovolt. 2024, 15, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-López, D.-A.; Vega-De-Lille, M.I.; Sacramento-Rivero, J.C.; Ponce-Caballero, C.; El-Mekaoui, A.; Navarro-Pineda, F. Life Cycle Assessment of Photovoltaic Panels Including Transportation and Two End-of-Life Scenarios: Shaping a Sustainable Future for Renewable Energy. Renew. Energy Focus 2024, 51, 100649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutel, C. Brightway: An Open Source Framework for Life Cycle Assessment. J. Open Source Softw. 2017, 2, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, P.; Javimczik, S.; Benevit, M.; Veit, H. Recycling WEEE: Polymer Characterization and Pyrolysis Study for Waste of Crystalline Silicon Photovoltaic Modules. Waste Manag. 2017, 60, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waithaka, A.; Plakantonaki, S.; Kiskira, K.; Mburu, A.W.; Chronis, I.; Zakynthinos, G.; Githaiga, J.; Priniotakis, G. Cellulose-Based Biopolymers from Banana Pseudostem Waste: Innovations for Sustainable Bioplastics. Waste 2025, 3(4), 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duflou, J.R.; Peeters, J.R.; Altamirano, D.; Bracquene, E.; Dewulf, W. Demanufacturing Photovoltaic Panels: Comparison of End-of-Life Treatment Strategies for Improved Resource Recovery. CIRP Annals 2018, 67, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Guo, J.; Yan, G.; Zhu, G.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, B. A Novel and Efficient Method for Resources Recycling in Waste Photovoltaic Panels: High Voltage Pulse Crushing. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 257, 120442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.S.; Rahman, K.S.; Chowdhury, T.; Nuthammachot, N.; Techato, K.; Akhtaruzzaman, M.; Tiong, S.K.; Sopian, K.; Amin, N. An Overview of Solar Photovoltaic Panels’ End-of-Life Material Recycling. Energy Strategy Rev. 2020, 27, 100431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikucioniene, D.; Mínguez-García, D.; Repon, M.R.; Milašius, R.; Priniotakis, G.; Chronis, I.; Kiskira, K.; Hogeboom, R.; Belda-Anaya, R.; Díaz-García, P. Understanding and Addressing the Water Footprint in the Textile Sector: A Review. AUTEX Res. J. 2024, 24(1), 20240004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nain, P.; Kumar, A. Theoretical Evaluation of Metal Release Potential of Emerging Third Generation Solar Photovoltaics. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2021, 227, 111120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkanis, K.; Vokas, G.; Kiskira, K. Investigating the Sustainability of Wind Turbine Recycling: A Case Study—Greece. Mater. Circ. Econ. 2024, 6, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolahchian Tabrizi, M.; Famiglietti, J.; Bonalumi, D.; Campanari, S. The Carbon Footprint of Hydrogen Produced with State-of-the-Art Photovoltaic Electricity Using Life-Cycle Assessment Methodology. Energies 2023, 16, 5190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Process Family | Data-Quality Tier 1(Industrial/Pilot) | Tier 2(Lab→Pilot Scaled) | Tier 3(Literature/Model) | Dominant Uncertainty Drivers | Typical CoV (%) | Representative Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

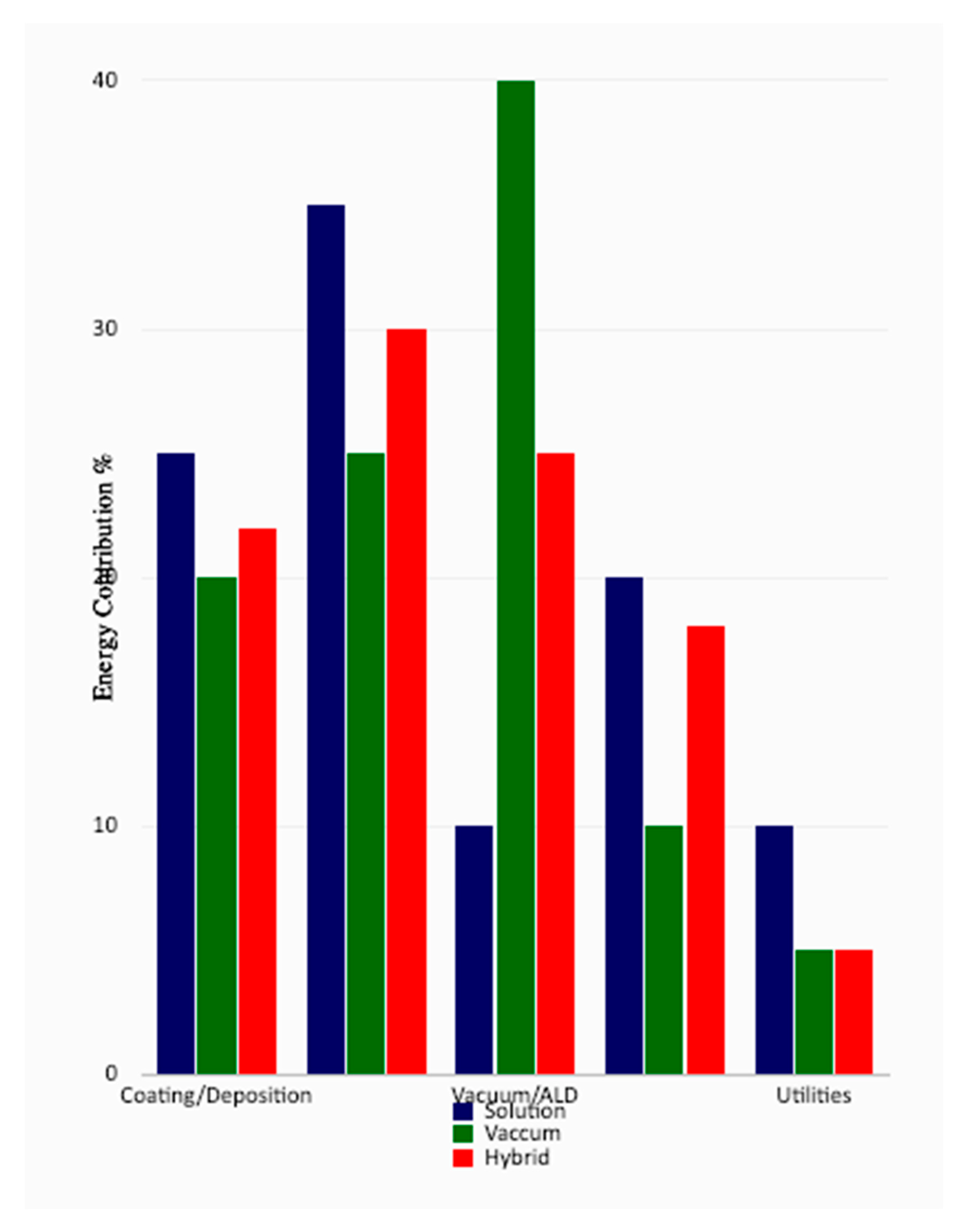

| Solution-processed(slot-die, blade, inkjet) | Measured energy ≈ 200-250 MJ m⁻² | 250-400 MJ m⁻² | 300-500 MJ m⁻² | Solvent recovery η, annealing temperature, substrate mass | 30-60% | [12,15,16,42,45,52] |

| Vacuum-processed(ALD, sputter, evaporation) | 150-200 MJ m⁻² | 200-350 MJ m⁻² | 250-400 MJ m⁻² | Chamber heating, pump idle power, throughput | 20-50% | [17,37,38,53,54] |

| Hybrid thin-film/tandem | 220-280 MJ m⁻² | 300-380 MJ m⁻² | 350-450 MJ m⁻² | Encapsulation mass, yield, interface recombination losses | 25-45% | [12,32,40,42,55] |

| Encapsulation/lamination | 40-70 MJ m⁻² | 60-100 MJ m⁻² | 80-120 MJ m⁻² | Curing route, barrier foil, curing temperature | 15-30% | [12,38,39,44] |

| Ancillary/utilities (HVAC, vacuum, power electronics) | 10-20% of total energy | 15-25% | 20-30% | Grid mix, duty cycle, maintenance schedule | 10-25% | [26,37,39,54,56,57] |

| Category | Required Reporting Items | Why It Matters | Applies to | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional unit (FU) | 1 m² active area and 1 kWp; module efficiency, active/total area ratio; yield to FU | Misaligned FUs can shift results by >×10; active-area normalization enables lab→pilot translation | All | [3,8,12,48] |

| System boundary | Foreground steps (substrate prep, deposition/coating, drying/anneal, metallization, encapsulation) vs. background (electricity mix, gases, solvents); explicit exclusions (HVAC, vacuum idle) | Boundary gaps drive hidden variance; explicit foreground/back-ground splits enable harmonization | All | [3,24,26] |

| Electricity | Grid mix (region, year), carbon intensity, on-site generation; tool idle vs. loaded power; duty cycles | Top driver of GWP; 2-4× swings across regions; idle time is a frequent hotspot | All | [2,24,48,66,67,81,82,86,87] |

| Process LCIs (per step) | Energy (MJ/m²), gases/solvents (kg/m²), consumables, rejects/yield, tool setpoints (T, t, P) | Enables step-wise attribution and meta-analysis | Solution, vacuum, hybrid lines | [12,17,42,85] |

| Solvent management | Solvent identity, recovery efficiency (%), losses, abatement | Major driver in wet lines; recovery is a first-order lever | Solution lines | [12,15,16,42] |

| Vacuum equipment | Pumping scheme, chamber volume, base pressure, cycle times, idle energy | Throughput-sensitive; chamber/pump energy dominates per m² | Vacuum lines | [17,56] |

| Annealing/drying | Heating method (furnace vs. photonic), setpoints, line speed, thermal losses | Often the single largest energy step; ecodesign is essential | All | [12,38] |

| Encapsulation & substrates | Glass/foil types, barrier performance, curing route (UV/thermal), mass per m² | Shifts GWP by double digits; constrains EoL options | All | [12,32,40,42] |

| Data tier & pedigree | Tier (1-3), measurement vs. model, TRL, vintage; uncertainty ranges | Enables uncertainty propagation and fair weighting | All | [24,26,60] |

| Scenario levers | Grid-carbon pathways, solvent recovery, Ag reduction, yield/throughput | Transparent sensitivity; supports prospective results | All | [24,48,69,70,81,82,86,87] |

| BOS and power electronics | Inverter rating, lifetime, replacement, efficiency | BOS can be non-trivial in system LCAs | Systems | [37,48,84] |

| EoL modeling | Collection, transport, process flows, recovery yields (Si, Ag, glass, Al), credits/allocation | Determines circularity benefits; can reduce GWP by ~40-60% | All | [30,32,71,72,73,74,75,88,89,90,91,92] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).