Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

27 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Familial cancers are caused by inherited mutations in specific genes that regulate cell growth, division, and repair. Approximately 5–10% of all cancer cases have a hereditary component, where germline mutations in certain genes increase an individual’s susceptibility to developing cancer. Two major categories of genes are involved in cancer development: tumour suppressor genes and oncogenes. Both play critical roles in regulating normal cell behaviour, and when mutated, they can contribute to uncontrolled cell proliferation and tumour formation. In addition to genetic mutations, epigenetic alterations also play a significant role in familial cancer. Epigenetics refers to changes in gene expression due to DNA methylation, histone modifications, and the dysregulation of non-coding RNAs without alter the underlying DNA sequence. Familial cancer syndromes follow various inheritance patterns, including autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, X-linked, and mitochondrial inheritance, each with distinct characteristics. Identifying genetic mutations associated with familial cancers is a cornerstone of genetic counselling, which helps individuals and families navigate the complex intersection of genetics, cancer risk, and prevention. Early identification of mutations enables personalized strategies for risk reduction, early detection, and, when applicable, targeted treatment options, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Key Genes Involved in Familial Cancer

2.1. Tumor Suppressor Genes

2.1.1. BRCA1 and BRCA2

2.1.2. RB1

2.1.3. APC (Adenomatous Polyposis Coli)

2.1.4. DNA Mismatch Repair Genes

2.1.5. PTEN

2.1.6. TP53 (p53)

2.2. Oncogenes

2.2.1. HER2/neu (ERBB2)

2.2.2. Ras

2.2.3. MYC

2.2.4. BCR-ABL

3. Epigenetic Inheritance in Familial Cancer

3.1. Mechanisms of Epigenetic Inheritance

3.2. DNA Methylation

3.3. Histone Modifications

3.4. Non-Coding RNAs

4. Inheritance Patterns

4.1. Autosomal Dominant

4.2. Autosomal Recessive

4.3. X-Linked Hereditary Cancer

4.4. Mitochondrial Inheritance (Maternal Inheritance)

5. General Recommendations for Cancer Genetic Testing in the Community

6. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Daly, M.B.; Pal, T.; Berry, M.P.; Buys, S.S.; Dickson, P.; Domchek, S.M.; et al. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic, Version 2.2021. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2021, 19, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RC, Selander, I; Connor, A.A.; Selvarajah, S.; Borgida, A.; Briollais, L. et al. Prevalence of Germline Mutations in Cancer Predisposition Genes in Patients With Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology 2015, 148, 556–564. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tung, N.; Lin, N.U.; Kidd, J.; Allen, B.A.; Singh, N.; Wenstrup, R.J.; et al. Frequency of Germline Mutations in 25 Cancer Susceptibility Genes in a Sequential Series of Patients With Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016, 34, 1460–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourmasoumi, P.; Ali Moradi, A.; Bayat, M. BRCA1/2 mutations and breast/ovarian cancer risk: A new insights review. Gynecol Onvol 2024, 31, 3624–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakeman, I.M.M.; Broek, A.J.; Vos, J.A.M.; Barnes, D.R.B.; Adlard, J.; Andrulis, I.L.; et al. The predictive ability of the 313 variant–based polygenic risk score for contralateral breast cancer risk prediction in women of European ancestry with a heterozygous BRCA1 or BRCA2 pathogenic variant. Genet Med 2021, 23, 1726–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Engel, C.; Hoya, M.; Peterlongo, P.; Yannoukakos, D.; Livragh, L.; et al. Risks of breast and ovarian cancer for women harboring pathogenic missense variants in BRCA1 and BRCA2 compared with those harboring protein truncating variants. Genet Med 2022, 24, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghallaigh, O.N.; Eeles, R. Genetic predisposition to prastate cancer: an update. Familial Cancer 2022, 21, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajwa, P.; Quhal, F.; Pradere, B.; Gandaglia, G.; Ploussard, G.; Leapman, M.S.; et al. Prostate cancer risk, screening and management in patients with germline BRCA1/2 mutations. Nature Reviews Urology 2023, 20, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Ding, P.-R. Update on Familial Adenomatous Polyposis-Associated Desmoid Tumors. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2023, 36, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, A.K.; Dowty, J.G.; Reece, J.C.; Lee, G.; Templeton, A.S.; Plazzer, J.-P.; et al. Variation in the Risk of Colorectal Cancer for Lynch Syndrome: A retrospective family cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2021, 22, 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephanie ACohen, S.A.; Leininger, A. The genetic basis of Lynch syndrome and its implications for clinical practice and risk management. The Application of Clinical Genetics 2014, 7, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Karapetyan, L.; Huang, Z.; Knight, A.D.; Rajendran, S.; Sander, C.; et al. Multiple primary melanoma in association with other personal and familial cancers. Cancer Med 2023, 12, 2474–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelina, T. Regua AT, Najjar M, Lo H-W. RET signaling pathway and RET inhibitors in human cancer. Front. Oncol 2022, 12, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, N.; Bar-Shalom, R.B.; Saab, A.; Fares, F. Germline Polymorphisms on RET Proto-oncogene involved in Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma in a Druze Family –A case study. European Journal of Cancer 2017, 82, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocci, E.; Milne, R.L.; Méndez-Villamil, E.Y.; Hopper, J.L.; John, E.M.; Andrulis, I.L.; et al. Risk of Pancreatic Cancer in Breast Cancer Families from the Breast Cancer Family Registry. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2013, 22, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasen, H.F.A.; Canto, M.I.; Goggins, M. Twenty-five years of surveillance for familial and hereditary pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Historical perspectives and introduction to the special issue. 21. Fam Cancer. 2024, 23, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, S.A.; Ruano, D.; Joruiz, S.M.; Stroosma, J.; Glavak, N.; Montali, A.; et al. Germline variant affecting p53β isoforms predisposes to familial cancer. Nat Commun 2024, 18, 15–8208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palles, C.; Cazier, J.B.; Howarth, K.M.; Domingo, E.; AJones, A.M.; Broderick, P.; et al. Germline mutations afecting the proofreading domains of POLE and POLD1 predispose to colorectal adenomas and carcinomas. Nat Genet 2013, 45, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.-H.; Dong, J.; Li, W.-L.; Kou, Z.-Y.; Yang, J. Genotype–Phenotype Correlations in Autosomal Dominant and Recessive APC Mutation-Negative Colorectal Adenomatous Polyposis. Dig Dis Sci 2023, 68, 2799–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renella, R.; Gagne, K.; Beauchamp, E.; Fogel, J.; Perlov, A.; Sola, M.; et al. Congenital X-linked Neutropenia with Myelodysplasia and Somatic Tetraploidy due to a Germline Mutation in SEPT6. Am J Hematol 2023, 97, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imyanitov, E.N.; Kuligina, E.S.; Sokolenko, A.P.; Suspitsin, E.N.; Yanus, G.A.; Iyevleva, A.G.; et al. World J Clin Oncol 2023, 14, 40–68. [CrossRef]

- Aryanti, C.; Uwuratuw, J.A.; Labeda, I.; Raharjo, W.; Lusikooy, R.E.; Rauf, M.A.; et al. The Mutation Portraits of Oncogenes and Tumor Supressor Genes in Predicting the Overall Survival in Pancreatic Cancer: A Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2023, 24, 2895–2902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Orazi, G. p53 Function and Dysfunction in Human Health and Diseases. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngeow, J.; Eng, C. PTEN in Hereditary and Sporadic Cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2020, 10, a036087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgson, S.V.; Foulkes, W.D.; Maher, E.R.; ClareTurnbull, C. Inherited Susceptibility to Cancer: Past, Present and Future. Annals of HumanGenetics, 2025, 89, 354–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, Y. Molecular pathological approach to cancer epigenomics and its clinical application. Pathol Int 2024, 74, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Ren, B.; Fang, Y.; Ren, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; et al. Epigenetic regulation in cancer. Med Comm 2024, e495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

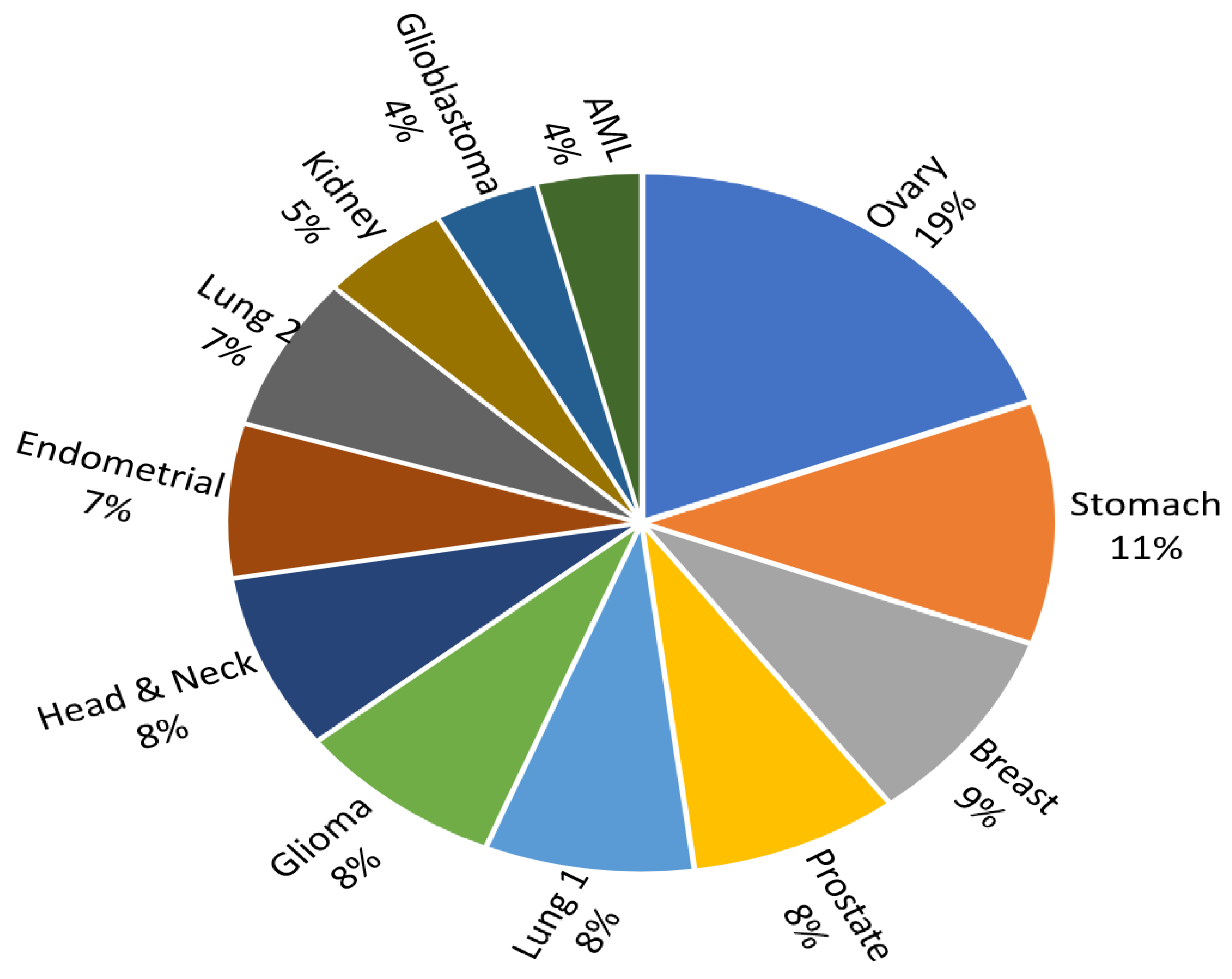

- Lu, C.; Xie, M.; Wendl, M.C.; Wang, J.; McLellan, M.D.; Leiserson, M.D.M.; et al. Patterns and functional implications of rare germline variants across 12 cancer types. Nature Communications 2015, 6, 10086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Silvestri, V.; Leslie, G.; Rebbeck, T.R.; Neuhausen, S.L.; Hopper, J.L.; et al. Cancer Risks Associated With BRCA1 and BRCA2 Pathogenic Variants. J Cilin Oncol 2022, 40, 1529–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narod, SA, Foulkes WD (2004). “BRCA1 and BRCA2: 1994 and beyond.” Nature Reviews Cancer 2004, 4, 814–819.

- Al-Shamsi, H.O.; Alwbari, A.; Azribi, F.; Calaud, F.; Thuruthel, S.; Tirmazy, S.H.H.; et al. RCA testing and management of BRCA-mutated early-stage breast cancer: a comprehensive statement by expert group from GCC region. Front Oncol 2024, 14, 1358982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miki, Y.; Swensen, J.; Shattuck-Eidens, D.; Futreal, P.A.; Harshman, K.; Tavtigian, S.; Liu, Q. A Strong Candidate for the Breast and Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility Gene BRCA1. Science 1994, 266, 66–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, A.; Pharoah, P.D.P.; Narod, S.; Risch, H.A.; Eyfjord, J.E.; Hopper, J.L.; et al. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 2003, 72, 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuchenbaecker, K.B.; Hopper, J.L.; Barnes, D.R.; et al. Risks of Breast, Ovarian, and Contralateral Breast Cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. JAMA. 2017, 317, 2402–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavaddat, N.; Peock, S.; Frost, D.; Ellis, S.; Platte, R.; Fineberg, E.; et al. Cancer Risks for BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers: Results From Prospective Analysis of EMBRACE. J Nat Can Inst 2013, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, Y.C.; Domchek, S.; Parmigiani, G.; Chen, S. Breast Cancer Risk Among Male BRCA1 and BRCA2 Mutation Carriers. J Nat Can Inst 2007, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastrodomenico, L.; Piombino, C.; Riccò, B.; Barbieri, E.; Venturelli, M.; Federico Piacentini, F.; Dominici, M.; Cortesi, L.; Toss, A. Personalized Systemic Therapies in Hereditary Cancer Syndromes. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odemis, D.A.; Kebudi, R.; Bayramova, J.; Erciyas, S.K.; Turkcan, G.K.; Tuncer, S.B.; et al. RB1 gene mutations and genetic spectrum in retinoblastoma cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2023, 102, e35068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Fu, J.; Huang, Y.; Fu, C. Mechanism of APC truncation involved in colorectal cancer tumorigenesis (Review) Oncol Lett. 2025, 29, 2. [CrossRef]

- Groden, J.; Thliveris, A.; Samowitz, W.; Carlson, M.; Gelbert, L.; Albertsen, H.; Joslyn, G.; JStevens, J.; et al. Cell1991, 66, 3589–3600. [CrossRef]

- Aelvoet, S.; Buttitta, F.; Ricciardiello, L.; Dekker, E. Management of familial adenomatous polyposis and MUTYH-associated polyposis; new insights. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 2022;58–59:101793. [CrossRef]

- Kayhanian, H.; Cross, W.; van der Horst, S.E.M.; Barmpoutis, P.; Lakatos, E.; Caravagna, G.; Zapata, L.; et al. Homopolymer switches mediate adaptive mutability in mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancer. Nat Genet, 2024, 56, 1420–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, A.K.; Schachtner, G.; Tulchiner, G.; Thurnher, M.; Untergasser, G.; Obrist et, a.l. Lynch Syndrome: Its Impact on Urothelial Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.M. Mechanisms and functions of DNA mismatch repair. Cell Res. 2008, 18, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiricny, J. The multifaceted mismatch-repair system. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, F.G.; Bustamante-Lopez, L.A.; D’Albuquerque, L.A.C.; Ribeiro Junior, U.; Herman, P.; Martinez, C.A.R. A review to honor the historical contribution of pauline gross, Aldred Warthin and Henry Lynch in the description and recognition of inheritance in colorectal cancer. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2024, 37, e1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, M.C.; Blumenthal, G.M.; Dennis, P.A. PTEN loss in the continuum of common cancers, rare syndromes and mouse models. Nat Rev Cancer 2011, 11, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, W.; Merlino, G.; Yu, Y. PTEN Dual Lipid- and Protein-Phosphatase Function in Tumor Progression. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 3666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Kitchen-Smith, I.; Xiong, L.; Stracquadanio, G.; Brown, K.; Richter, P.H.; et al. Germline and Somatic Genetic Variants in the p53 Pathway Interact to Affect Cancer Risk, Progression, and Drug Response. Cancer Res 2021, 81, 1667–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Su, Z.; Tavana, O.; Gu, W. Understanding the complexity of p53 in a new era of tumor suppression. Cancer Cell 2024, 42, 946–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghatak, D.; Ghosh, D.D.; Roychoudhury, S. Cancer Stemness: p53 at the Wheel Front Oncol 2021, 10, 604124. [CrossRef]

- Gabriella D’Orazi, G. p53 Function and Dysfunction in Human Health and Diseases. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumont, A.C.; Cadore, N.A.; Pedrotti, L.G.; Curzel, G.D.; Schuch, J.B.; Marina Bessel, M.; et al. Germline rare variants in HER2-positive breast cancer predisposition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol 2024, 14, 1395970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Kim, S.B. HER2-Low Breast Cancer: Now and in the Future. Cancer Res Treat 2024, 56, 700–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahar, F.; Haider, G.; Priyanka Zahoor, S. Correlation between grade of the tumour and HER2NEU status in breast cancer. The professional Medical Journal 2025;32. [CrossRef]

- Dunnett-Kane, V.; Burkitt-Wright, E.; Blackhall, F.H.; Malliri, A.; Evans, D.G.; Lindsay, C.R. Germline and sporadic cancers driven by the RAS pathway: parallels and contrasts. Ann Oncol 2020, 3, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Medarde, A.F.; Rivas, J.D.L.; Santos, E. 40 Years of RAS—A Historic Overview. Genes (Basel) 2021, 12, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, L.; Wang, P. Emerging strategies to target RAS signaling in human cancer therapy. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2021, 14, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafry, M.; Sidbury, R. RASopathies. Clin Dermatol 2020, 38, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunnett-Kane, V.; Burkitt-Wright, E.; Blackhall, F.H.; Malliri, A.; Evans, D.G.; Lindsay, C.R. Germline and sporadic cancers driven by the RAS pathway: parallels and contrasts. Ann Oncol 2020, 31, 873–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freie, B.; Carroll, P.A.; Varnum-Finney, B.J.; Ramsey, E.L.; Ramani, V.; Bernstein, I.; Eisenman, R.N. A germline point mutation in the MYC-FBW7 phosphodegron initiates hematopoietic malignancies. Genes Dev 2024, 38, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.V. MYC on the path to cancer. Cell 2012, 149, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadeu, F.; Garcia, N.; Wang, L.; Verdú-Amorós, J.; Andrés, M.; Conde, N.; et al. MYC-rearranged mature B-cell lymphomas in children and young adults are molecularly Burkitt Lymphoma. Blood Cancer Journal 2024, 14, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidaka, M.; Inokuchi, K.; Uoshima, N.; Takahashi, N.; Yoshida, N.; Ota, S.; et al. Development and evaluation of a rapid one-step high sensitivity real-time quantitative PCR system for minor BCR-ABL (e1a2) test in Philadelphia-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (Ph+ ALL). Jpn J Clin Oncol 2024, 54, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soverini, S.; Hochhaus, A.; Nicolini, F.E.; Gruber, F.; Lange, T.; Saglio, G.; et al. BCR-ABL kinase domain mutation analysis in chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of European LeukemiaNet. Blood 2011, 118, 1208–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolella, H.D.; de Assis, S. Epigenetic Inheritance: Intergenerational Effects of Pesticides and Other Endocrine Disruptors on Cancer Development. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonning, P.E.; Nikolaienko, O.; Pan, K.; Kurian, A.W.; Eikesdal, H.P.P.; Pettinger, M.; et al. Constitutional BRCA1 methylation and risk of incident triple-negative breast cancer and high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2025; 40;16 suppl. [CrossRef]

- Hitchins, M.P. Constitutional epimutation as a mechanism for cancer causality and heritability? Nature Reviews Cancer 2015, 15, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch A, Joosten SC, Feng Z, de Ruijter TC, Draht MX, Melotte V, etal. Analysis of DNA methylation in cancer: location revisited. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2018, 15, 459–466. [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.F. Epigenomics in cancer management. Cancer Manag Res 2010, 2, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherif, Z.A.; Ogunwobi, O.O.; Ressom, H.W. Mechanisms and technologies in cancer epigenetics. Front Oncol. 2024, 14, 1513654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helderman, N.C.; Andini, K.D.; van Leerdam, M.E.; van Wezel, T.; Morreau, H.; Nielsen, M.; et al. MLH1 Promotor Hypermethylation in Colorectal and Endometrial Carcinomas from Patients with Lynch Syndrome. J Mol Diagnosis 2024, 26, P106–P114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younesian, S.; Mohammadi, M.H.; Younesian, O.; Momeny, M.; Ghaffari, S.H.; Bashash, D. DNA methylation in human diseases. Heliyon 2024, 15, e32366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martisova, A.; Holcakova, J.; Izadi, N.; Sebuyoya, R.; Hrstka, R.; Martin Bartosik, M. DNA Methylation in Solid Tumors: Functions and Methods of Detection Int J Mol Sci 2021, 228, 4247. [CrossRef]

- Voss, T.C.; Hager, G.L. Dynamic regulation of transcriptional states by chromatin and transcription factors. Nat Rev Genet 2014, 152, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chris, P. Ponting, Peter L. Oliver, Wolf Reik. Evolution and Functions of Long Noncoding RNAs. Cell 2009, 136, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauria, F.; Iacomino, G. The landscape of circulating miRNAs in the post-genomic era. Genes 2021, 13, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Gregory, R.I. MicroRNA biogenesis pathways in cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer 2015, 15, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponting, C.P.; Oliver, P.L.; Reik, W. Evolution and functions of long noncoding RNAs. Cell 2009, 1364, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, R.A.; Shah, N.; Wang, K.C.; Kim, J.; Horlings, H.M.; Wong, D.J.; Tsai, M.C.; THung, T.; Argani, P.; et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature 464:1071–1076. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, H.; Lu, Y.; Cheng, L. Circular RNAs in human cancer. Frontiers in oncology 2021;10. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.B.; Jensen, T.I.; Clausen, B.H.; Bramsen, J.B.; Finsen, B.; Damgaard, C.K.; Kjems, J. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature 2013, 495, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, J.; Wen, J.; Huang, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, B.; Chu, L. Small Nucleolar RNAs: Insight Into Their Function in Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussen, B.M.; Hidayat, H.J.; Salihi, A.; Sabir, D.; Taheri, M.; Ghafouri-Fard, S. MicroRNA: A signature for cancer progression. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2021, 138, 111528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabbage, M.; Ben Aissa-Haj, J.; Othman, H.; Jaballah-Gabteni, A.; Laarayedh, S.; Elouej, S.; Medhioub, M.; et al. A Rare MSH2 Variant as a Candidate Marker for Lynch Syndrome II Screening in Tunisia: A Case of Diffuse Gastric Carcinoma. Genes (Basel) 2022, 13, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garutti, M.; Foffano, L.; Mazzeo, R.; Michelotti, A.; Da Ros, L.; Viel, A.; et al. Hereditary Cancer Syndromes: A Comprehensive Review with a Visual Tool. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.; Weedon, M.N.; Harrison, J.W.; Wood, A.R.; Ruth, K.S.; Tyrrell, J.; et al. Influence of family history on penetrance of hereditary cancers in a population setting. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 64, 102159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alter BP, Cancer in Fanconi anemia, 1927-2001. Cancer 2003, 97, 425–440. [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, M.; Muthupandian, S.; Dejene, T.A. Bloom syndrome: an oral potentially malignant disorders aiding in malignancy vigour. Int J Surg. 2023, 109, 529–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuge, K.; Shimamoto, A. Research on Werner Syndrome: Trends from Past to Present and Future Prospects. Genes (Basel). 2022, 13, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Paull, T.T. Cellular Functions of the Protein Kinase ATM and Their Relevance to Human Disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 796–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Song, X.; Pan, H.; Li, X.; Sun, L.; Song, L.; et al. Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome: A new synonym mutation in the WAS gene. Intractable Rare Dis Res 2024, 13, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, K.; Zhang, A.; Yan, X.; Liu, S.; Chen, D. Primary central nervous system Burkitt lymphoma in a 38-year-old immunocompetent woman: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2025, 104, e42321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alston, C.L.; Stenton, S.L.; Hudson, G.; Prokisch, H.; Taylor, R.W. The genetics of mitochondrial disease: dissecting mitochondrial pathology using multi-omic pipelines. Journal of Pathology 2021, 254, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.C. Mitochondria and cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer 2012, 12, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Reyes, I.; Chandel, N.S. Cancer metabolism: looking forward. Nature Reviews Cancer 2021, 21, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Mahmood, M.; Reznik, E.; Gammage, P.A. Mitochondrial DNA is a major source of driver mutations in cancer. Trends in Cancer 2022, 8, 1046–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Syndrome | miRNA Role |

|---|---|

| DICER1 syndrome | Germline mutations in DICER1 → impaired miRNA processing tumours in lung, ovary, thyroid, etc. |

| Li-Fraumeni syndrome | miR-34 family is regulated by TP53; dysfunction may amplify cancer risk in TP53 mutation carriers. |

| HBOC (Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer) | miR-182 and others regulate BRCA1 expression; dysregulation may affect DNA repair. |

| Familial colorectal cancer | miR-155 and others can target MMR genes (MLH1, MSH2), influencing Lynch syndrome pathogenesis. |

| Syndrome / Condition | Gene(s) Involved | Associated Cancers |

|---|---|---|

| Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer | BRCA1, BRCA2 | Breast, ovarian, prostate, pancreatic |

| Lynch Syndrome (HNPCC) |

MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, EPCAM |

Colorectal, endometrial, ovarian, gastric, urinary tract |

| Li-Fraumeni Syndrome | TP53 | Breast, brain, sarcomas, adrenal, leukemia |

| Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) | APC | Colorectal (almost 100% risk), small intestine, stomach |

| Cowden Syndrome | PTEN | Breast, thyroid (follicular), endometrial |

| Peutz-Jeghers Syndrome | STK11 (LKB1) | GI tract (colon, stomach, pancreas), breast, cervix, testes |

| Hereditary Retinoblastoma | RB1 | Retinoblastoma (eye), osteosarcoma |

| Von Hippel–Lindau Disease (VHL) | VHL | Kidney (RCC), pheochromocytoma, CNS hemangioblastomas |

| Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) | MEN1 | Parathyroid, pancreatic, pituitary tumours |

| Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type 2 (MEN2) | RET | Medullary thyroid carcinoma, pheochromocytoma |

| Syndrome | Common Genes | Associated Cancers |

|---|---|---|

| Hereditary Breast & Ovarian Cancer (HBOC) | BRCA1, BRCA2 | Breast, ovarian, prostate, pancreas |

| Lynch Syndrome | MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, EPCAM |

Colorectal, endometrial, ovarian, gastric |

| Li-Fraumeni Syndrome | TP53 | Sarcomas, brain, breast, adrenal |

| Cowden Syndrome | PTEN | Breast, thyroid, endometrial |

| Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) | APC | Colorectal (hundreds of polyps) |

| MUTYH-Associated Polyposis | MUTYH | Colorectal polyps/cancer |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).