1. Introduction

Over the last couple of decades, the global financial sector has undergone significant changes in the composition of financial products, service delivery methods, and client bases [

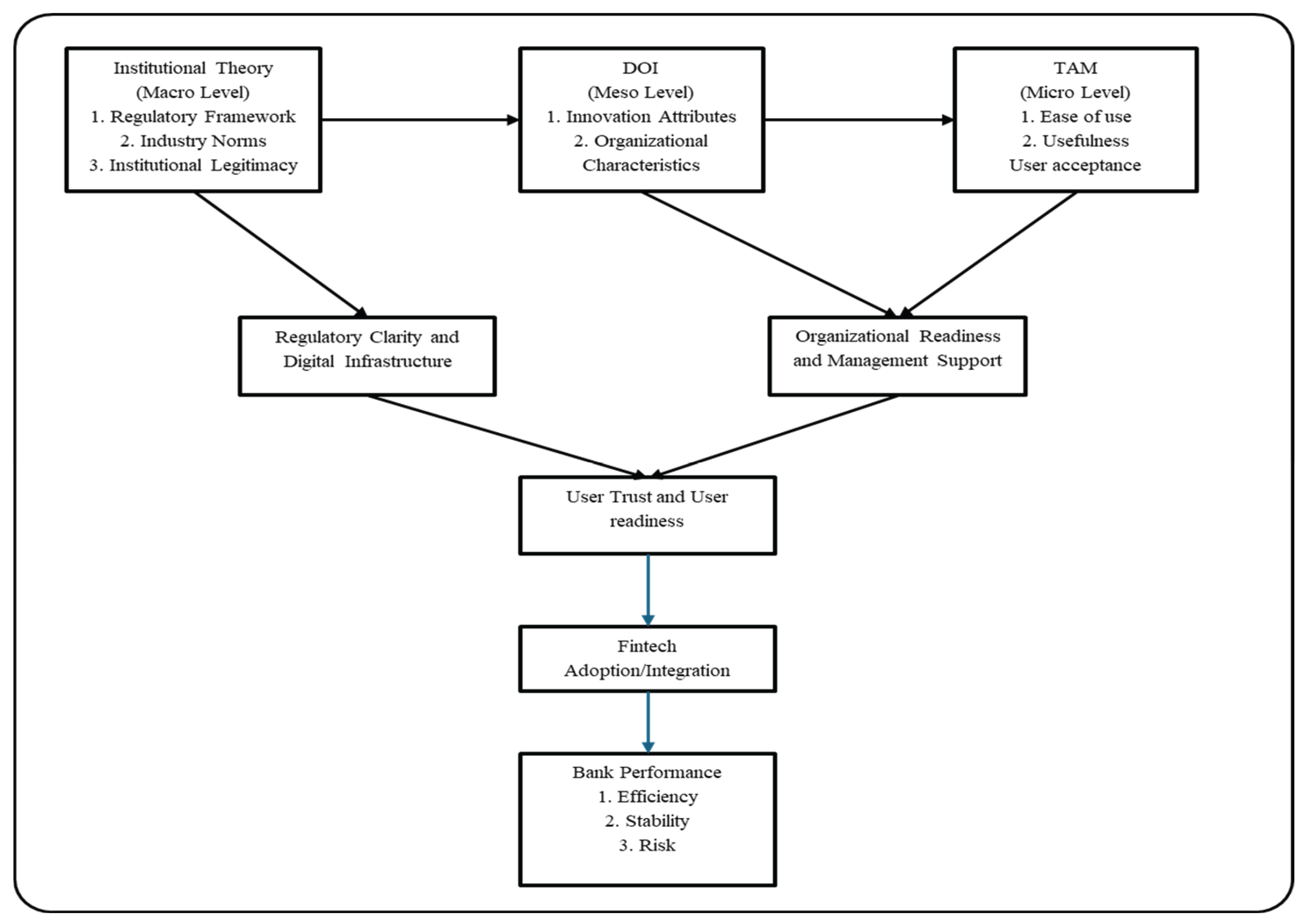

1]. Indeed, financial services have become technologically advanced through a diverse set of innovations, including mobile banking platforms, automated teller machines (ATMs), digital wallets, and online banking. Their introduction has significantly improved the financial accessibility, convenience, and operational efficiency [

2] of financial institutions, including banks. This has also helped overcome the geographical and infrastructural barriers, allowing individuals in remote or underserved regions to participate in the financial system. Although there remains a level of security concern, the digital transformation of the banking industry is considered one of the significant innovations of the 20th century. The introduction of advanced artificial intelligence (AI)- supported financial technology (Fintech) promises to take financial sector development far ahead.

Banks, especially commercial banks, which are at the center of the global financial landscape, have also undergone a digital transformation of their operations through fintech. This digitization, facilitated by numerous fintech innovations, has played a crucial role in expanding the service net to include many previously unbanked individuals [

3]. According to the World Bank, approximately 1.2 billion adults gained access to a formal banking institution, and among them, nearly 35 percent are connected through mobile banking [

4]. Also, digitalization has played a crucial role in enhancing transaction speed, expanding the range of services offered, and extending coverage to a broader geographical area. Gomber et al. [

5] argued that the adoption of digital banking technologies has enabled banks to serve a wide range of customers at a lower cost. Furthermore, fintech has enhanced the customer experience by offering personalized services, real-time analytics, and automated advisory solutions, thereby increasing customer satisfaction and loyalty [

6]. At the same time, Fintech has also helped to improve banks’ financial risk management through AI-driven fraud detection, encryption, and biometric authentication [

7]. Studies also found that fintech enhances innovation and competitiveness, allowing banks to develop new products such as peer-to-peer lending, robo-advisory services, and seamless cross-border payments, thereby increasing revenue streams and market share [

8,

9]

Recognizing the benefits of wider technology adoption, the banking industry has actively partnered with fintech companies through mergers, acquisitions, and integrations. For example, in October 2025, HSBC proposed a

$13.6 billion offer to acquire the remaining 36.5% of Hang Seng Bank, valuing it at

$37 billion and strengthening its presence in Hong Kong [

10]. In April 2025, Columbia Banking System acquired Pacific Premier Bank for

$2.92 billion to expand its Pacific Northwest footprint and enhance digital services [

11]. In 2024, UniCredit acquired digital bank Aion Bank to boost its digital offerings [

12], and Robinhood acquired fintech startup Pluto to improve personalized financial planning and AI-driven investment tools [

12]. That same year, Pagaya acquired Theorem, a provider of digital asset management solutions, to expand AI-driven investment capabilities [

12]. Additionally, Revolut announced a

$670 million investment in India in October 2025 to grow its local operations and fintech offerings [

13], while FIS acquired Amount, a Chicago-based digital account origination platform, further strengthening its banking technology solutions [

14].

However, there are examples of fintech failures. For instance, in 2022, HSBC launched an international payments app, Zing. By 2024, it had accumulated US

$87.5 million; unfortunately, HSBC closed it by the end of that year. It was called a “Huge Mistake” by JPMorgan’s CEO when it acquired fintech startup Frank for about

$175 million. Solid was a fintech startup in Palo Alto that raised nearly US

$81 million at one point. Despite reporting profitability in 2022, it filed for bankruptcy in April 2025 due to compliance costs and its inability to raise additional capital. Volt was the first full-fledged neo-bank in Australia. In June 2022, it announced it would shut down and return its license [

15].

The previous illustrations demonstrate that when some financial institutions earn substantial profits, others may lose their entire investment in a fintech project. This phenomenon affects customers, companies, financial institutions, regulatory frameworks, and societal dynamics, influencing various aspects of the banking sector [

16]. Therefore, a relevant question is: what is the impact of fintech on banks’ efficiency and stability? However, the literature offers somewhat contradictory evidence regarding the relationship between fintech adoption and bank performance. While studies [

17] found little difference between them, [

18] indicated that the banking industry is significantly affected by fintech, which may not impact profitability. A study [

19] evaluates the impact of fintech on banking performance and customer satisfaction in the US market. By sampling 100 banks, they found that fintech adoption increases customer satisfaction and improves cost efficiency. Another study [

20] investigates the effect of fintech adoption on bank financial performance, using regression analysis across 60 countries. They found a more notable positive impact in developed countries, with a weaker relationship in developing countries. Thesis [

21] explores the impact of fintech integration on Jordanian banks. Analyzing a sample of 13 commercial banks over 10 years, they concluded that fintech integration has a positive effect on the financial performance and stability of banks.

After identifying a gap in the literature, this research builds on and extends the existing body of work by providing new evidence on how fintech adoption and integration affect the efficiency and stability of selected Asian countries. The context of this study is important for several reasons. First, East and Southeast Asia are considered global fintech leaders; for example, China, Singapore, and Indonesia have become major fintech hubs. Alipay and WeChat Pay dominate the Chinese market, while GrabPay is prominent in Singapore. Meanwhile, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Thailand are recognized as the fastest-growing fintech economies [

22]. India is also emerging as a major player in fintech, with the foundation of digital payments being the Unified Payments Interface (UPI), valued for its speed and convenience. PhonePe and Google Pay are the two leading companies in the market. These rapid developments create a rich context for studying fintech. Second, this region has become a key area for venture capital investment. For instance, Southeast Asia recorded US

$8.9 billion in fintech investments in 2022 [

23] and US

$6.0 billion in 2023 [

24]. The fintech market in India is projected to grow from a valuation of USD 44.12 billion in 2025 to USD 95.30 billion by 2030, with a strong 16.65% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) [

25]. Third, the region’s diverse economic makeup, which includes China and India—two of the world’s second and fourth largest economies—as well as developed countries like Japan, South Korea, and Singapore, along with emerging economies such as Malaysia, Indonesia, and Vietnam, makes it a noteworthy area of research.

The authors of the research assess that this paper should contribute to the existing literature in the following ways:

Firstly, it offers a comprehensive analysis of the banking sectors in this region, along with the current state of fintech adoption among the area’s financial institutions. It will also deepen our understanding by examining fintech’s role in stabilizing and increasing the efficiency of banks in this region.

Secondly, the ongoing debates on the pace of fintech integration in emerging economies address whether these countries should align their fintech adoption strategies with global trends or take a more cautious, context-specific approach. The research will guide whether rapid adoption or a more gradual integration of fintech is appropriate, based on each country’s unique economic and institutional circumstances.

Finally, this study adds value by providing a comparative analysis of fintech adoption across different banking systems in East and Southeast Asia. By examining various regulatory environments, market conditions, and consumer behaviors, the research reveals regional differences in fintech implementation and its impact on banking practices. This comparative perspective will help policymakers and industry leaders craft more tailored strategies to boost fintech adoption and maximize its benefits in their respective countries.

The paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews the current literature relevant to fintech adoption, efficiency, and stability, and develops hypotheses based on this discussion.

Section 3 provides a detailed description of the data and methods used in this research.

Section 4 presents the results, followed by conclusions and recommendations in

Section 5.

3. Methodology

3.1. Model Selection and Variables

We propose the following empirical model to test three hypotheses:

Here, Risk, Profitability, and Efficiency are the dependent variables in Models 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The literature has shown that there is no perfect indicator of bank risk. Nevertheless, several proxies have been used in the current literature to measure bank risk, such as non-performing loans [

36,

37,

38], provision for loan loss (PLL) [

39,

40], Leverage Ratio [

41,

42], and Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR) [

43,

44]. For this research, we will use NPL and PLL as proxies for risk because NPL measures the proportion of loans that are not being collected from borrowers as agreed. A higher NPL ratio indicates greater credit risk. On the other hand, PLL measures the amount kept aside for expected loan losses as a proportion of total loans. High provisions can indicate greater perceived risk in the loan portfolio.

Efficiency is defined as the ratio of outputs to inputs within the firm. In the current literature, several proxies have been used as efficiency measures, for instance, the Cost to Income Ratio (CIR) [

36,

45,

46], the Operating Expense to Operating Income (ETI) [

47], and the Return on Equity (ROE) [

48]. Current research employed CIR and efficiency ratio; the rationale for using these two variables is that CIR measures operational efficiency. A lower ratio indicates that the banks are managing their operating costs effectively. On the other side, a higher CIR ratio indicates banks have failed to maintain their operating efficiency. In the same way, efficiency (EFF) measures the cost of generating each additional unit of income. A higher EFF ratio signals better cost management and operational efficiency, as the bank can control costs while generating revenue.

A firm’s stability is its ability to meet its financial obligations. The prior study attempted to identify the actual measurements that indicate a tendency toward bankruptcy. However, some researchers measure stability in different ways. For example, the Z-score is a measure of stability, which is considered one of the effective determinants of bankruptcy [

50]. Conversely, research also used the Solvency ratio as a proxy of stability [

49]. The solvency ratio indicates whether the firm can fulfill its current financial obligations. It can be calculated as the immediate cash available over the immediate cash obligation. Therefore, this research also uses the Z-score and the solvency ratio as proxies for stability.

On the right side of Equations (1)–(3), we used the fintech index as the independent variable. Several methods are commonly employed in recent fintech research, including text mining [

51,

52], text disclosure analysis [

53], and fintech component scoring [

54]. However, when these methods extract fintech-related keywords from news, corporate reports, or online sources, a significant limitation of text mining is media-driven bias: institutions mentioned more frequently in fintech-related news may appear highly fintech-active, even when their actual adoption level is limited. This can result in systematic measurement errors.

Similarly, text disclosure analysis, which counts fintech-related keywords in annual reports, faces challenges from selective disclosure bias. Firms vary widely in how much they voluntarily disclose, and fintech terminology may be used inconsistently across banks and countries. Meanwhile, component-based indices are more structured and conceptually sound, but they rely heavily on the availability of detailed fintech indicators. In practice, many banks do not fully disclose key digital metrics, such as mobile banking user numbers, transaction volumes, and channel-specific usage data. Cross-country differences in disclosure standards further restrict comparability.

Given these limitations, this study develops a Weighted Scoring-based Fintech Adoption Index that is transparent, reproducible, and applicable across different banking systems. The index is structured around three key dimensions of fintech adoption: Digital Access, Digital Transaction Options, and Customer Interface. Within these dimensions, eight observable, publicly verifiable indicators were developed (see

Table 1). Each indicator is assigned an equal weight. Based on the level of fintech adoption, each item is scored as 0.00 (no adoption), 0.50 (partial adoption), or 1.00 (full adoption).

The Fintech Adoption Index for banks is calculated using the following formula:

where FNT represents the fintech index of bank i at time t, Score refers to the score assigned to each indicator, and Weight is equally distributed across all indicators. Because all indicators are weighted equally, the relative weight remains constant over time.

3.1. Data Collection and Description

Initially, we planned to collect data from 104 local banks across nine Asian countries. However, due to data limitations, we could only obtain information for 92 banks. After addressing missing data for different banks across various years, our final sample included 85 banks, distributed as follows: China (16), South Korea (7), Japan (17), Malaysia (8), Vietnam (8), Thailand (6), Indonesia (8), Singapore (2), and India (13) over 11 years from 2014 to 2024. A list of the sample banks is included in the Appendix . All data were collected from the Bloomberg terminal.

In addition to the specific bank’s dataset, we included the natural logarithm of total assets and return on assets (ROA) as bank-specific control variables. At the country level, we used the percentage of internet users, domestic credit to the private sector by banks (as a percentage of GDP), and GDP growth as control variables.

For our analysis and comparison of selected Asian banks, we have divided all nine countries into three categories. Reg-1 included three developed countries: Japan, Korea, and Singapore. Next, we grouped Reg-2 across the three major Asian economies: China, India, and Indonesia. The remaining three emerging countries, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam, have been termed as Reg-3. To make a robust analysis we used bot OLS and Random effect regression analysis in this research. This research employed statistical software STATA to run the regression.

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics for all 89 banks across nine Asian countries. Throughout the research, we mainly used ratio analysis to compare banks across these countries; however, the values are reported in millions of local currencies. The fintech index has a mean of 0.837 and a standard deviation of 0.124, indicating moderate adoption among the sample banks. From the table, we also see that the NPL ratio is 2.230%, with a standard deviation of 2.622% and a minimum of 0.010%, while the average NPL is 1.024%. The standard deviation of 1.180% reflects banks’ expected loan losses. Efficiency ratios have a mean of 50.244 and a standard deviation of 14.055, suggesting significant variation in operational efficiency across banks. The mean cost-to-income ratio (CIR) is 1.418, with a standard deviation of 1.273, indicating heterogeneity in expense management.

The mean stability ratio (STB) is 2.484, with a standard deviation of 4.106, while the average Z-score is 4.931, with a standard deviation of 3.479, indicating variation in capitalization and risk-absorption capacity across banks. Total assets (log) have a mean of 4.177 and a standard deviation of 0.713. Return on assets (ROA) averages 0.808%, with a standard deviation of 0.743%, reflecting differences in profitability among banks. Digital infrastructure, measured as the percentage of internet users, has a mean of 68.85% and a standard deviation of 24.36, indicating moderate digital penetration across the sampled countries but significant differences among them. Domestic credit provided by private banks (DCPB) averages 105.718% of GDP (SD = 40.256), while GDP growth averages 3.923% (SD = 3.365), indicating that the banks in the countries examined are not homogeneous.

5. Conclusions and Policy Recommendation

Fintech is no longer just a buzzword; it has become a vital part of our everyday lives. The world is rapidly adopting fintech, a trend the banking industry closely follows. Driven by this change, this research aims to analyze how fintech adoption impacts banks’ risk, efficiency, and stability. To achieve this, the study gathered data from 85 local banks listed on major stock exchanges across nine Asian countries.

Bank risk was measured using Non-Performing Loans and Provision for Loan Losses. The results show that fintech adoption significantly reduces bank risk in certain Asian countries, particularly in larger economies such as China, India, and Indonesia, as well as in emerging markets such as Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam. However, in developed nations such as Japan, Korea, and Singapore, fintech adoption appears to increase bank risk. This indicates that in mature economies, fintech encourages greater competition, leading banks to lend more aggressively and, consequently, increasing NPLs, PLLs, and overall risk exposure.

Efficiency was assessed using both the efficiency ratio and the cost-to-income ratio. The regression results show mixed outcomes regarding the link between fintech adoption and bank efficiency. In Asia, fintech integration is positively associated with efficiency, suggesting that greater fintech adoption improves overall operational effectiveness, especially in developed countries where banks benefit from mature infrastructure. On the other hand, in large and emerging economies, fintech adoption negatively affects efficiency. This is likely due to the additional investments required for onboarding new clients and integrating fintech components, which increase operational costs. Additionally, lower financial literacy in these regions may further hinder bank efficiency.

Bank stability was evaluated using Z-scores and the Stability ratio. The link between fintech adoption and stability differs across countries. In Asia, stability ratios show a negative relationship, indicating that fintech adoption increases short-term cash obligations. Conversely, Z-scores in the same region indicate a positive relationship, suggesting improved overall stability. Similar trends appeared in both mature developed and emerging markets, although large economies showed the opposite effect. Overall, the results indicate that fintech integration improves risk management and stability but does not necessarily lead to efficiency gains.

Analyzing bank-specific variables, total assets show a negative link with risk and a positive link with both efficiency and stability. This suggests that larger banks tend to have lower risk while maintaining higher efficiency and stability. Similar patterns were observed with Return on Assets (ROA): banks with higher profitability exhibited lower financial risk, greater efficiency, and stability.

At the national level, internet penetration is linked to higher bank risk, while loans issued by private banks tend to have lower risk exposure. Both internet use and private bank lending positively influence efficiency and stability. Conversely, GDP growth does not seem to affect bank risk, efficiency, or stability directly.

Based on the findings of this study, several policy recommendations can be made to optimize the benefits of fintech adoption in the banking sector. First, regulators should encourage banks in large and emerging economies to adopt fintech gradually while ensuring robust risk management frameworks to prevent a rise in NPLs and PLLs. Second, central banks and financial authorities should implement guidelines that promote responsible lending practices in highly competitive, fintech-driven markets. Third, governments should invest in financial literacy programs, especially in emerging economies, to improve customer understanding and reduce inefficiencies associated with onboarding new fintech users. Fourth, policymakers should promote collaboration between fintech firms and traditional banks to foster innovation while sharing the associated risk. Seventh, internet infrastructure expansion and digital access policies should be aligned with banking regulations to maximize efficiency and stability gains without increasing risk exposure. Finally, governments and central banks should provide targeted support to smaller banks, enabling them to adopt fintech effectively and thereby enhance overall competitiveness and stability in the banking sector. This research covers only domestic banks; the results may not reflect those of foreign banks in the same region, which will be addressed in future research.