Submitted:

02 July 2025

Posted:

03 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction and Background

1.1. Research Questions

- Adoption: How does FinTech and AI uptake differ between Islamic and conventional banks?

- Efficiency: Does FinTech adoption reduce operating costs and improve profit margins, and is the effect bank-type specific?

- Stability: How does digital transformation influence financial-stability metrics particularly the Z-score and non-performing loans (NPLs) across banking models?

- Trade-off: Do Islamic banks experience a different efficiency–stability trade-off in the digital era compared with conventional banks?

1.2. Objectives

- To assess how Islamic and conventional banks have integrated AI and FinTech solutions into their business strategies.

- To compare efficiency metrics (e.g., cost-to-income, overhead ratios) in the digital era.

- To examine financial stability indicators post-AI and FinTech integration (e.g., z-score, NPLs, capital adequacy).

- To analyze and compare the relative magnitudes of FinTech's impact on efficiency and stability indicators across Islamic and conventional banks to identify potential differential efficiency-stability balances/trade-offs during.

1.3. Contribution

1.4. Structure of the Paper

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Financial Technology and Artificial Intelligence in Banking: A Paradigm Shift

-

- Operational Efficiency: Automation of the back office through artificial intelligence is reducing the cost and time of processing substantially. For instance, advanced analytics and Robotic Process Automation (RPA) have managed to reduce the cost by 20–30% in labor-intensive processes such as loan origination, fraud detection, and compliance surveillance (Vermann & Zwick, 2019; Bontadini et al., 2024). The efficiency advantage lowers the cost of operations of the banks, which in turn allows them to focus on value-added services.

- 5

- Financial Inclusion: Digital-exclusive banking products, mobile remittances, and micro-lending schemes through machine learning significantly improved access to financial services for previously unbanked or underserved parts of the population, primarily in the emerging markets (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2022; World Bank, 2022). Through the minimization of transaction costs and further reach, FinTech lowers geographic and socio-economical distances to achieve broader financial participation.

- 6

- Risk Modeling: Machine learning algorithms and big data analytics are continuously improving the precision of credit scoring, fraud detection, and risk evaluation in general (Fuster et al., 2019). The advanced approaches are able to process large datasets, recognize subtle patterns, and predict defaults 15–25% better than the traditional statistical models, enhancing prudential financial risk management.

2.2. Islamic vs. Conventional Banking: Divergent Paths to Digital Transformation

- Conventional Banks: Conventional banks primarily operate on the lines of neoclassical financial intermediation theory (Gulati, A., & Singh, 2024). Maximization of profit through the allocation of resources in an efficient manner, conversion of risk, and minimizing of the transaction cost is the main aim of conventional banks. Therefore, conventional banks aim for technology which is scalable in nature to offer operational leverage and direct bottom line improvement, embracing FinTech solutions as tools of competitive advantage and gain of market share (Lerner et al., 2024).

- Islamic Banks: Islamic Banks: For comparison, Islamic banks are grounded in the Maqasid al-Sharia (Islamic law principles), which extended beyond financial success alone to the attainment of broader ethical, social, and developmental goals (Bedoui & Mansour, 2015). The model places specific emphasis on risk-sharing, equitable wealth distribution, social justice, and strict avoidance of riba (interest), gharar, and maysir. This integrated theoretical and ethical gap profoundly reflects the adoptions criterion of FinTech solutions: they must be efficient but also transparently demonstrably Sharia-compatible and therefore there is greater questioning and oft times slower approvals process (Fianto et al., 2021).

Empirical Evidence

- Several specialists believe the Islamic banks have been sluggish in early adoption of the FinTech in the years 2020–2022 relative to the traditional counterparts (Aysan et al., 2022). The initial delay is generally the result of the necessary strict Sharia board approvals of new product and technology which could slow the product/technology development and roll-out cycles.

- Despite the initial setback, there is increasingly evidence of Islamic banks achieving greater rates of growth in some of the FinTech applications subsequent to 2023, particularly in sectors best suited to their very basics. Examples are the application of blockchain to the issuance and settlement of sukuk (Islamic bonds), which enhances efficiency and transparency, and biometric eKYC (electronic Know Your Customer) solutions to ease the onboarding of customers while fulfilling data privacy and security expectations (Rabbani et al., 2020).

- In comparison, the conventional banks have taken the central role in the use of Open Banking APIs enabling smooth data sharing and collaboration amongst third-party suppliers of FinTech (Buchak et al., 2023). Whilst the pathway exhibits vast innovation potential, the method also exhibits enhanced cybersecurity and data privacy risks, which in turn necessitate robust infrastructures of digital security. Such dynamic interplay of adoption patterns underscores subtle approaches driven by inherent variation in the institutional level.

2.3. Regulating Environments and Institutional Challenges

-

- Proactive Markets (i.e., UAE, Malaysia): Such markets have adopted forward-thinking approaches to regulation, often guided by whole-of-nation digital agendas and specialist FinTech sandboxes. For instance, the UAE’s National AI Strategy 2031 specifically accelerates the adoption of AI in the financial services, telecommunications, and public sectors (CBUAE, 2022). In proactive markets, Islamic banks benefit from an operating model of dual-layer oversight—independent central-bank oversight alongside Sharia-based advice by independent Sharia boards—when aligned, which can create clear avenues for ethical compliant FinTech innovation (IFSB, 2023). Such forward-thinking approach specifies the environment and reduces regulatory risk, therefore allowing fast and confident FinTech adoption.

- 7

- Cautious Markets (e.g., Egypt, Pakistan): Conversely, there are markets which are cautious and exhibit slow FinTech regulation or the lack of specialized regimes for new technology. Such regulatory slack can restrain innovation through elevated legal and operational risks for financial entities (Rabbani et al., 2020; SBP, 2023). Here, Islamic banks are inclined to rely even further on joint ventures with agile FinTech startups to navigate regulatory ambiguities and exploit novel solutions, in place of in-house competence building. It thus suggests that institutional forces, in particular the lack of definitive regulatory cues, compel the banks to seek external partnerships to meet the shifting demand of markets.

2.4. Knowledge Gaps and This Study’s Contribution

- Studies have explored FinTech’s impact on conventional bank profitability and efficiency (Thakor, 2020; Berisha & Rayfield, 2025).

- Significant research has delved into the inherent stability of Islamic finance compared to conventional finance (Abedifar et al., 2013; Beck et al., 2013).

- Some recent works have begun to address FinTech adoption patterns in Islamic banking (Aysan et al., 2022; Hamadou & Suleman, 2024).

-

- Quantitatively compared efficiency gains (e.g., through cost-to-income ratios and ROA) between Islamic and conventional bank types in the wake of FinTech adoption, providing a nuanced understanding of who benefits more or differently.

- 8

- Analyzed the differential influence of FinTech on financial stability (e.g., Z-score) across these two distinct banking models, moving beyond baseline stability comparisons to examine the moderating role of digital transformation.

- 9

- Empirically tested the efficiency-stability nexus within the context of FinTech adoption for both Islamic and conventional banks to ascertain if a unique trade-off or balance emerges.

- 10

- Integrated the dynamic nature of FinTech adoption through a comprehensive index while simultaneously controlling for institutional and macroeconomic factors.

- Introducing a 7-point FinTech Index Score developed to provide a standardized, robust, and empirically derived measure of FinTech and AI adoption within the banking sector, facilitating direct comparison.

- Conducting a rigorous panel data analysis that tests the interactions between bank type (Islamic/Conventional) and FinTech adoption to isolate differential impacts on efficiency and stability.

- Incorporating relevant macroeconomic controls (Inflation, GDP Growth) and bank-specific characteristics (Size, Equity/Assets, NPL Ratio) within a fixed-effects model to ensure robust findings.

- Providing quantitative insights into how FinTech influences the efficiency-stability balance for both banking models, contributing to the understanding of their distinct responses to digital transformation.

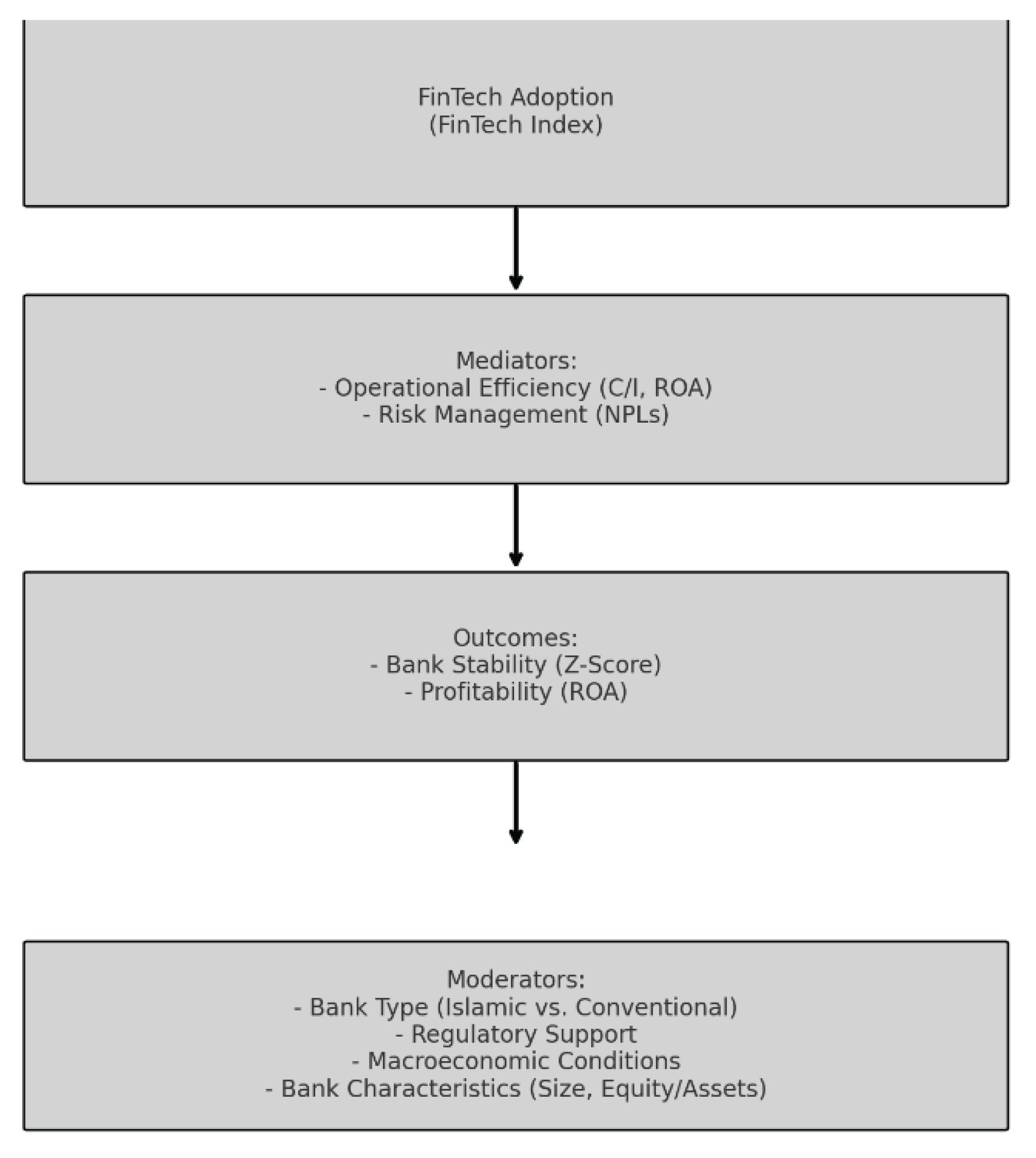

- 2.5. Theoretical Framework

2.5.1. Resource-Based View (RBV)

2.5.2. Financial Stability Theory

- Efficiency Channels: As demonstrated by our efficiency models, FinTech can lead to lower operational costs (reduced C/I) and increased profitability (higher ROA). More efficient and profitable banks are generally more stable, as they have greater buffers against unexpected losses and can absorb shocks more effectively (lower costs → higher Z-scores).

- Risk Channels: While FinTech, particularly AI-driven analytics, can significantly reduce traditional credit risks (e.g., by improving NPL predictions) and operational risks through automation, it simultaneously introduces new categories of risks. These include cybersecurity threats, data privacy breaches, algorithmic bias, and systemic risks arising from interconnectedness and concentration within FinTech platforms (BIS, 2021; Lerner et al., 2024).

- Business Model Transformation: FinTech allows banks to diversify revenue streams beyond traditional interest-based income, potentially reducing reliance on single income sources and thereby enhancing stability. This is particularly relevant for Islamic banks, whose existing emphasis on diversified, asset-backed financing aligns well with non-interest-based FinTech opportunities.

2.6. Research Hypotheses

- ●

- H1 (Adoption Differential): Islamic banks exhibit significantly lower FinTech Index scores than conventional banks, ceteris paribus.

- ○

- Rationale: Differences in operational models, the inherent cautiousness due to Sharia compliance requirements, and varying risk aversion levels may lead to disparate paces of technological adoption compared to their conventional counterparts.

- ●

- H2 (Efficiency Effect): FinTech adoption is negatively associated with the cost-to-income ratio, and this negative association is significantly stronger for conventional banks compared to Islamic banks.

- ○

- Rationale: Conventional banks, with their broader operational scope, less stringent compliance constraints (compared to Sharia boards for new technologies), and profit-driven optimization, may be positioned to leverage FinTech more extensively for rapid cost optimization and enhanced operational efficiency.

- ●

- H3 (Stability Effect): FinTech adoption is positively associated with bank stability (measured by Z-score), and this positive association is significantly stronger for Islamic banks compared to conventional banks.

- ○

- Rationale: Through the characteristics of risk-sharing norms, asset-backed finance, and ethical banking practices, Islamic banks would be able to leverage the potential of FinTech better for higher stability, possibly drawing greater resilience through advanced tools of risk management without unnecessarily increasing systemic risk.

- ●

- H4 (Efficiency–Stability Balance): While FinTech adoption positively impacts both profitability (e.g., Return on Assets - ROA) and stability (e.g., Z-score) across both bank types, Islamic banks will exhibit a comparatively stronger positive effect on stability relative to their profitability gains from FinTech adoption than conventional banks, signifying a distinct efficiency-stability balance.

- ○

- Rationale: Islamic banks' initial priority for true economic activity, mutual risk-sharing, and ethical issues could lead to the relative stability gains of adopting FinTech to be higher for the same level of efficiency improvement, in particular compared to conventional banks which are largely driven by pure profit maximization.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

-

- Descriptive Analysis: Compare trends in FinTech adoption (via the FinTech Index Score), efficiency metrics (cost-to-income ratios), and stability indicators (Z-scores) between Islamic and conventional banks.

- 11

- Inferential Analysis: Use panel regression models to isolate the effects of FinTech adoption on performance for bank type (Islamic = 1, conventional = 0) and country level controls.

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. FinTech Adoption Index

3.4. Variables

- o Cost-to-Income Ratio (Operational efficiency) (Beck et al., 2013).

- o Fee Income to Total Income (Revenue diversification) (Arjunwadkar, 2019).

- o Z-Score (Probability of insolvency) (Laeven & Levine, 2009).

- o NPL Ratio (Asset quality) (Berger & DeYoung, 1997).

- o FinTech Index Score (0-7 scale), validated by prior studies (Feyen et al., 2021).

- o FinTech Flag (1 = Adoption, 0 = None) for robustness checks.

- o Islamic (1) vs. conventional (0), following (Abedifar et al., 2013).

- Bank Size: Log of total assets.

- Macroeconomic: GDP growth, inflation (country-year level) (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2022).

3.5. Empirical Models

- Efficiency Model:

- 14.

- Stability Model:

3.6. Robustness Checks

-

- Alternative Specifications:

-

- o Replace FinTech Score with FinTech Flag.

-

- o Include country-year fixed effects.

- 15.

- Endogeneity Tests:

-

- o Lagged independent variables to mitigate reverse causality (Wintoki et al., 2012).

3.7. Ethical Considerations

4. Data and Descriptive Statistics

4.1. Sample Composition

4.2. Variable Overview

4.3. Comprehensive Analysis of Variables

4.4. FinTech Adoption Patterns

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. FinTech Adoption and Efficiency (RQ2 & H2)

5.2. FinTech Adoption and Stability (RQ3 & H3)

5.3. FinTech Adoption Differential (RQ1 & H1)

5.4. Efficiency-Stability Trade-off (RQ4)

6. Conclusion and Policy Implications

6.1. Summary of Key Findings

- FinTech Adoption Differential (RQ1 & H1): The descriptive analysis, robustly supported by trends over time, confirms Hypothesis 1, indicating a statistically significant and consistent lag in FinTech adoption by Islamic banks compared to their conventional counterparts. Conventional banks consistently maintain higher average FinTech Index scores throughout the observed period.

- FinTech and Efficiency (RQ2 & H2): We found strong evidence that increased FinTech adoption significantly enhances bank efficiency, leading to a reduction in the Cost-to-Income ratio and an increase in Return on Assets (ROA) for the banking sector as a whole. However, the hypothesized differential effect where the reduction in cost-to-income would be stronger for conventional banks was not supported. The benefits of FinTech on operational efficiency and profitability appear to be largely similar in magnitude for both Islamic and conventional banks. Interestingly, Islamic banks exhibited superior baseline efficiency (lower C/I, higher ROA) compared to conventional banks, even before considering FinTech's impact.

- FinTech and Stability (RQ3 & H3): Our results demonstrate that higher FinTech adoption is significantly associated with enhanced financial stability, as measured by the Z-score. This positive relationship holds for both bank types. However, Hypothesis 3, which predicted a stronger increase in Z-score for Islamic banks due to FinTech, was not supported by the data. The stability gains from FinTech adoption appear comparable across Islamic and conventional banking models. Moreover, Islamic banks showed a significantly higher baseline Z-score, confirming their inherent relative stability.

- Efficiency-Stability Trade-off (RQ4): Based on our findings, while FinTech generally improves both efficiency and stability, there is no statistically discernible evidence to suggest that Islamic banks experience a fundamentally different efficiency-stability trade-off in the digital era compared to conventional banks due to FinTech adoption. The marginal impacts of FinTech on these two dimensions are not significantly different across the bank types.

6.2. Policy Implications

- ●

- For Banks (Islamic and Conventional):

- ○

- Global imperative for adoption of FinTech: The continued positive impact of FinTech for efficiency and stability also creates the strategic justification for all the banks to continue to invest in and deliver digital transformation initiatives. FinTech is now increasingly a source of competitiveness but also becoming an imperative for sustained performance and resilience.

- ○

- Strategic priority for Islamic banks: Even with the natural efficiency and stability benefits inherent to Islamic banks, they need to catch up quickly in adopting FinTech (H1). Although the advantages of FinTech are the same, having to begin further down the adoption curve could in the long run undermine their competitive advantage. Specialized FinTech strategies for Shariah-compliant solutions and the further digitization of customer interfaces are needed to bridge the gap.

- ○

- Capitalizing on in-built strengths: Islamic banks can capitalize on having greater initial stability to potentially take on bolder FinTech initiatives, where they might possess a greater cushion for initial risks of new technology.

- ●

- For Regulators:

- ○

- Enabling regulatory environment: Regulators should continue to have an environment favorable to innovation to embrace the use of FinTech across the entire banking sector, valuing its established beneficial impact on efficiency and stability.

- ○

- Specialized support for Islamic finance: Policymakers can think of specialized incentives or guidance for Islamic financial institutions to promote the use of FinTech, enabling them to leverage digital possibilities without abandoning the fundamental principles of the organization. It can be the establishment of sandboxes for Sharia-compatible FinTech, the release of technical assistance, or the creation of alliances between Islamic banks and FinTech firms.

- ○

- S Balancing innovation and oversight: Whilst stability is promoted by FinTech, regulators also need to pay close attention and tailor supervisory regimes to emerging new digital risks (e.g., cyber security, data privacy, algorithmic bias) stemming from higher technology diffusion.

- ●

- For FinTech Innovators:

- ○

- Market potential: The research determines the potential open market and real value for the FinTech products in all the regions. Product designers are required to continually enhance products for improved operational efficiency and risk management.

- ○

- Niche in Islamic finance: Despite the gap in adoption of the Islamic banks, there is vast potential for FinTech companies aimed at Sharia-compliant solutions. Recognizing the unique requirements and regulatory conditions of Islamic finance could usher in the floodgates of an underserved sea to digital innovation.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

- FinTech Index Granularity: While the empirically derived FinTech Index provides a valuable macro-level measure of adoption, it may not capture the nuanced impacts of specific FinTech categories (e.g., AI in lending vs. blockchain in trade finance). Future research could explore the effects of disaggregated FinTech components.

- Causality: While panel fixed effects were employed to control for unobserved heterogeneity, establishing strict causality remains challenging in observational studies. Future studies could employ quasi-experimental designs or instrumental variables if suitable data become available to strengthen causal inferences.

- Data Scope: The study focuses on listed commercial banks in specific OIC countries. Expanding the sample to include a wider range of financial institutions (e.g., smaller banks, non-bank financial institutions) and more diverse geographies could provide broader generalizability.

- Dynamic Effects: The current models capture average effects over time. Future research could explore dynamic effects, such as time lags in FinTech impact, or examine non-linear relationships.

- Qualitative Insights: A qualitative approach involving interviews with banking executives and FinTech leaders could provide deeper insights into the specific drivers and barriers to FinTech adoption, particularly within the Islamic banking sector.

- Trade-off Complexity: The "efficiency-stability trade-off" was inferred from individual models. More advanced econometric techniques, such as simultaneous equation models, could provide a more direct and robust assessment of this complex relationship.

References

- Abedifar, P., Molyneux, P.,; Tarazi, A. Risk in Islamic banking. Journal of Banking & Finance 2013, 37, 433–447. [Google Scholar]

- AFI: Alliance for Financial Inclusion. (2024). Digital Identity: A primer on e-KYC and financial inclusion. AFI Policy Framework.

- Arjunwadkar, P. Y. (2018). FinTech: The technology driving disruption in the financial services industry.

- Arner, D. W., Buckley, R. P., Zetzsche, D. A.,; Veidt, R. Sustainability, FinTech and financial inclusion. European Business Organization Law Review 2020, 21, 7–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aysan, A. F., Belatik, A., Unal, I. M.,; Ettaai, R. Fintech strategies of Islamic Banks: A global empirical analysis. FinTech 2022, 1, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank for International Settlements (BIS). (2021). Annual Economic Report: FinTech and financial stability.

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120.

- Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A.,; Merrouche, O. Islamic vs. conventional banking: Business model, efficiency, and stability. Journal of Banking & Finance 2013, 37, 433–447. [Google Scholar]

- Bedoui, H. E., & Mansour, W. (2015). Performance and Maqasid al-Shari'ah's pentagon-shaped ethical measurement. Science and Engineering Ethics, 21(3), 555-576.

- Berg, T., Burg, V., Gombović, A., & Puri, M. (2020). On the rise of FinTechs: Credit scoring using digital footprints. Review of Financial Studies, 33(7), 2845-2897.

- Berger, A. N., & DeYoung, R. (1997). Problem loans and cost efficiency in commercial banks. Journal of Banking & Finance, 21(6), 849-870.

- Berisha, V.,; Rayfield, B. Impact of internal fintech on bank profitability. Investment Management & Financial Innovations 2025, 22, 384. [Google Scholar]

- Bontadini, F., Filippucci, F., Jona Lasinio, C. S., Nicoletti, G., & Saia, A. (2024). Digitalisation of financial services, access to finance and aggregate economic performance. OECD Economics Department Working Papers, 1818.

- Buchak, G., Matvos, G., Piskorski, T., & Seru, A. (2018). FinTech, regulatory arbitrage, and the rise of shadow banks. Journal of Financial Economics, 130(3), 453-483.

- Catalini, C., & Gans, J. S. (2020). Some simple economics of the blockchain. Communications of the ACM, 63(7), 80-90.

- Central Bank of the UAE (CBUAE). (2022). UAE National Artificial Intelligence Strategy 2031.

- Daud, S. N. M., Khalid, A., & Azman-Saini, W. N. W. (2022). FinTech and financial stability: Threat or opportunity. Finance Research Letters, 47, 102667.

- Deloitte. (2023). Global Islamic banking outlook: Growth, digitalization, and resilience.

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A. , Klapper, L., Singer, D., Ansar, S., & Hess, J. (2022). The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial inclusion, digital payments, and resilience in the age of COVID-19. World Bank.

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147-160.

- Fianto, B. A., Hendratmi, A., & Aziz, P. F. (2021). Factors determining behavioral intentions to use Islamic financial technology: Three competing models. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 12(4), 794-812.

- Fuster, A., Plosser, M., Schnabl, P., & Vickery, J. (2019). The role of technology in mortgage lending. Review of Financial Studies, 32(5), 1854-1899.

- Gomber, P., Kauffman, R. J., Parker, C., & Weber, B. W. (2018). On the FinTech revolution: Interpreting the forces of innovation, disruption, and transformation in financial services. Journal of Management Information Systems, 35(1), 220-265.

- Gulati, A., & Singh, S. (2024). The Changing Landscape of Financial Services in the Age of Digitalization: A Bibliometric Analysis. NMIMS Management Review, 32(1), 42-57.

- Hamadou, I., & Suleman, U. (2024). FinTech and Islamic Finance: Opportunities and Challenges. The Future of Islamic Finance, 175-188.

- Hassan, M. K., & Aliyu, S. (2018). A contemporary survey of Islamic banking literature. Journal of Financial Stability, 34, 12-43.

- Huang, M.-H., & Rust, R. T. (2021). Artificial intelligence in service. Journal of Service Research, 24(1), 6-23.

- Iqbal, M. S., Sukamto, F. A. M. S. B., Norizan, S. N. B., Mahmood, S., Fatima, A., & Hashmi, F. (2025). AI in Islamic finance: Global trends, ethical implications, and bibliometric insights. Review of Islamic Social Finance and Entrepreneurship, 70-85.

- Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB). (2023). Islamic FinTech: Growth and stability.

- Laeven, L., & Levine, R. (2009). Bank governance, regulation and risk taking. Journal of Financial Economics, 93(2), 259-275.

- Lasak, P. , & Williams, J. (Eds.). (2023). Digital transformation and the economics of banking: economic, institutional, and social dimensions. Taylor & Francis.

- Lerner, J., Seru, A., Short, N., & Sun, Y. (2024). Financial innovation in the twenty-first century: Evidence from US patents. Journal of Political Economy, 132(5), 1391-1449.

- OECD. (2021). The digital transformation of financial markets: Key policy issues. OECD Publishing.

- OMFIF (2020). Global Public Investor 2020 Report: FinTech Adoption and Strategic Collaboration.

- Pahari, S., Polisetty, A., Sharma, S., Jha, R., & Chakraborty, D. (2023). Adoption of AI in the banking industry: A case study on Indian banks. Indian Journal of Marketing, 53(3), 26-41.

- Philippon, T. (2020). The FinTech opportunity (NBER Working Paper No. 22476). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Rabbani, M. R. , Khan, S., & Thalassinos, E. I. (2020). FinTech, blockchain and Islamic finance: An extensive literature review.

- Scott, W. R. (2014). Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests, and identities (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- State Bank of Pakistan (SBP). (2023). Banking sector review: FinTech adoption and challenges.

- Thakor, A. V. (2020). FinTech and banking: What do we know? Journal of Financial Intermediation, 41, 100833.

- Todorof, M. (2018). Shariah-compliant FinTech in the banking industry. In Era Forum (Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 1-17). Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Vermann, K., & Zwick, T. (2019). Financial inclusion, consumption, and cost efficiency: Evidence from the EU. European Economic Review, 120, 101–120.

- Vives, X. (2019). Digital disruption in banking: A review. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 11, 243-272.

- Wintoki, M. B., Linck, J. S., & Netter, J. M. (2012). Endogeneity and the dynamics of internal corporate governance. Journal of Financial Economics, 105(3), 581-606.

- World Bank. (2023). Digital Identification for Development: Technology Landscape. Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

| Factor | Conventional Banks | Islamic Banks |

| Primary Objective | Profit optimization; Market expansion | Compliance with Sharia + profit; Social impact |

| Interest (Riba) | Core mechanism | Prohibited |

| Governance Layer | Standard corporate governance | Includes Sharia supervisory board |

| Regulatory Focus | Open banking APIs (e.g., PSD2, GDPR alignment) | Sharia-compliant FinTech sandboxes; Ethical AI frameworks |

| Risk Sharing | Limited to derivatives/insurance | Yes (e.g., Musharakah, Mudarabah) |

| AI Applications | Predictive analytics for risk pricing; Robo-advisory for wealth maximization. Broad AI/FinTech adoption | Ethical AI for halal product design; Sharia-audited credit scoring; Zakat management solutions. Adopted cautiously with Sharia filters |

| Variable | Measurement | Source |

|---|---|---|

| FinTech Index Score | Sum of 7 binary FinTech features (0-7) | Bank annual reports, press releases |

| Cost-to-Income | Operating expenses / Operating income | Bank financial statements |

| Z-Score | (ROA + Equity/Assets) / σ(ROA) | Calculated from bank data |

| criteria (1 point each) |

Short operational test | Key literature anchor |

|---|---|---|

| Digital-Only App | Standalone mobile app with full banking functionality (not just a web portal) | Digital channels cut cost/frontier (Ghosh, 2022). Demirgüç-Kunt et al. (2022) found digital-only services reduce costs by 30% and improve financial inclusion. |

| Open-Banking / Public APIs | Public developer portal or formal PSD2/Open-Banking certification. | Open APIs boost fee income & cross-sell (Lasak & Williams, 2023). Fuster et al. (2019) link open APIs to 15% higher innovation output in banking ecosystems. |

| AI in customer service | Deployed AI chatbot / assistant handling retail queries. | Pahari et al., (2023) finds that employing AI service increases loyalty and decreases cost. Huang & Rust (2021) show AI service tools boost satisfaction scores by 25% in financial services |

| AI in credit & risk | AI/ML for credit scoring or fraud detection. | AI risk models reduce NPLs (Berg et al. (2020). Berg et al. (2020) demonstrate ML risk models reduce NPLs by 1.2–2.5% in emerging markets |

| Biometric e-KYC | Live facial / fingerprint on-boarding that satisfies regulator e-KYC rules. | World Bank (2023) reports biometric ID cuts onboarding time by 70% and fraud by 45%. e-KYC lowers entry friction, widens outreach (AFI 2024 guide). |

| Blockchain Usage | | Live blockchain applications (payments, smart contracts, or tokenization | Catalini & Gans (2020) show blockchain reduces settlement costs by 60% in cross-border transactions. DLT improves settlement speed & transparency. |

| Strategic FinTech partnerships | Formal collaborations with ≥3 FinTechs (e.g., payments, robot-advisory…) | Partnerships accelerate capability adoption (OMFIF 2020). BIS (2021) finds partnerships increase digital revenue share by 18% vs. in-house development |

| Country | Islamic Banks | Conventional Banks | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saudi Arabia | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Bahrain | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| UAE | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Malaysia | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Indonesia | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Pakistan | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Qatar | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Kuwait | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Turkey | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Jordan | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Egypt | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 13 | 13 | 26 |

| Variable | Islamic Banks (n=65) | Conventional Banks (n=65) | Full Sample (n=130) | t-test (Islamic-Conv) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FinTech Index (0-7) | 3.38 (1.82) | 3.92 (1.91) | 3.65 (1.87) | -2.11 | 0.042* |

| Total Assets ($bn) | 85.2 (112.3) | 182.6 (245.1) | 133.9 (195.7) | -3.45 | 0.001*** |

| ROA (%) | 1.60 (0.60) | 1.40 (0.80) | 1.50 (0.70) | 1.34 | 0.184 |

| ROE (%) | 14.2 (5.8) | 12.8 (6.4) | 13.5 (6.1) | 1.56 | 0.122 |

| Cost-to-Income | 0.43 (0.12) | 0.47 (0.14) | 0.45 (0.13) | -2.11 | 0.038* |

| NPL Ratio (%) | 3.20 (2.50) | 4.00 (3.10) | 3.60 (2.80) | -1.92 | 0.058† |

| Z-Score | 30.12 (21.04) | 23.62 (16.98) | 26.87 (19.01) | 2.04 | 0.044* |

| Equity/Assets (%) | 12.5 (3.6) | 11.7 (4.0) | 12.1 (3.8) | 1.27 | 0.208 |

| Inflation (decimal) | n.a. | n.a. | |||

| GDP Growth (decimal) | n.a. | n.a. |

| Year | All Banks | Islamic | Conventional | Gap (Conv - Islamic) |

| 2020 | 1.46 | 1.08 | 1.85 | +0.77 |

| 2021 | 3.04 | 2.77 | 3.31 | +0.54 |

| 2022 | 3.62 | 3.31 | 3.92 | +0.61 |

| 2023 | 3.65 | 3.38 | 3.92 | +0.54 |

| 2024 | 3.65 | 3.38 | 3.92 | +0.54 |

| Dependent Variable | (1) Cost-to-Income | (2) ROA | (3) Z-Score |

| FinTech Index | -0.019*** | 0.001*** | 1.890*** |

| (0.003) | (0.000) | (0.342) | |

| Islamic | -0.016* | 0.003** | 7.973** |

| (0.007) | (0.001) | (2.879) | |

| FinTech Index * Islamic | 0.001 | -0.000 | -0.428 |

| (0.002) | (0.000) | (0.395) | |

| Size (log Assets) | 0.005** | -0.000 | -1.530*** |

| (0.002) | (0.000) | (0.320) | |

| Equity/Assets | 0.312*** | 0.004 | 124.083*** |

| (0.052) | (0.003) | (15.545) | |

| NPL Ratio | 0.505*** | -0.021*** | -10.970*** |

| (0.061) | (0.003) | (2.730) | |

| ROA | 30.500*** | ||

| (4.062) | |||

| Inflation | 0.003 | -0.000 | -0.735 |

| (0.005) | (0.000) | (0.755) | |

| GDP Growth | -0.016 | 0.001 | -0.169 |

| (0.016) | (0.000) | (0.640) | |

| Constant | 0.425*** | 0.020*** | 32.540*** |

| (0.033) | (0.002) | (2.894) | |

| R-squared | 0.531 | 0.485 | 0.540 |

| Adj. R-squared | 0.470 | 0.419 | 0.479 |

| N | 130 | 130 | 130 |

| Fixed Effects | Year and Bank | Year and Bank | Year and Bank |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).