1. Introduction

Persistent mucosal inflammation promotes epithelial damage, mutagenic stress, and an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) that fosters colitis-associated colorectal cancer (CRC). The cGAS–STING cascade is a nodal DNA-sensing pathway that governs type-I IFN and NF-κB signaling, dendritic-cell licensing, and T-cell priming within the inflamed gut [

1]. In CRC and colitis models, both hypo- and hyper-active STING can be pathogenic, underscoring the need for precise, context-aware modulation rather than blunt activation or blockade [

2]. Structurally, cGAMP binding closes the STING V-shaped dimer and primes oligomerization with TBK1/IRF3 recruitment; polymeric assemblies underlie robust signal propagation [

3].

Among human STING cysteines, Cys148 is repeatedly implicated in oxidation/disulfide chemistry that stabilizes (or, when over-oxidized, perturbs) higher-order oligomers required for signaling [

4]. Redox studies and peptide mapping show that covalent modification at Cys148 disrupts oligomerization and TBK1 recruitment [

5], while oxidative stress can rewire Cys148/Cys206 states to dampen signaling [

6]. Together, these data position Cys148 as a gatekeeper for assembly-competent STING and a chemically tractable hot spot for small-molecule intervention [

7].

In parallel with redox-sensitive control at Cys148, covalent chemistry at Cys91 has been reported for certain small-molecule modulators of human STING. Our focus here is distinct that we investigate a non-covalent, CDN-rim pocket (Site-2) and its buried continuation (Site-2’) that emerge from AF3-guided docking and MD. In our entrance-state models, the average ExcB–Cys91 separation is geometrically incompatible with covalency, reinforcing the premise that a His157-anchored, non-competitive pathway can coexist with previously described covalent regimes. This distinction frames the subsequent two-step model tested below.

ExcB, isolated from Briareum spp. , is a briarane diterpenoid developed by marine natural-products groups [

8]. Across macrophage, dendritic-cell, dermatitis, arthritis, and pain models, ExcB reduces COX-2/iNOS expression, osteoclastogenesis, and inflammatory cell infiltration [

9]; more recently, ExcB and derivatives were shown to antagonize the cGAS–STING axis in vivo to promote wound repair, suggesting a direct molecular link between ExcB and STING signaling [

10]. These pharmacology data motivate structure-guided hypotheses connecting ExcB’s phenotypes to residue-level STING modulation relevant to colitis/CRC.

Previous studies have repeatedly used immune-competent models to define T-cell and chemokine-axis control by marine-derived natural products, most recently showing that alternariol modulates T-cell activation/migration to resolve lung inflammation [

11]; earlier work reported new algal/fungal metabolites with potent anti-inflammatory activity [

12]. These studies reinforce a tractable natural-product to immune-pathway paradigm that we extend here to the cGAS–STING pathway in gut inflammation.

Crystal and cryo-EM structures define the CDN-binding cleft and highlight conformational control points proximal to Cys148/Tyr240 (Site-1) [

1,

2,

3]. Building on this foundation, we deploy AlphaFold3 (AF3, a diffusion-based model that jointly predicts protein–ligand complexes) to explore alternative, druggable pockets and to test whether ExcB engages STING beyond Site-1 [

13]. Our AI-driven docking & MD pipeline converges on a non-canonical “Site-2” near Tyr167/Thr263 at the CDN-rim, yielding stable, water-mediated networks consistent with allosteric antagonism [

3].

We therefore test a mechanistic hypothesis: ExcB modulates pathogenic STING signaling in CRC-relevant inflammation by engaging a pocket adjacent to the CDN cleft and functionally intersecting the Cys148-dependent oligomerization axis. We integrate AF3 complex prediction, AI docking, and explicit-solvent MD with literature-anchored residue prioritization to generate falsifiable, residue-level predictions that can guide mutagenesis and chemical optimization.

2. Results

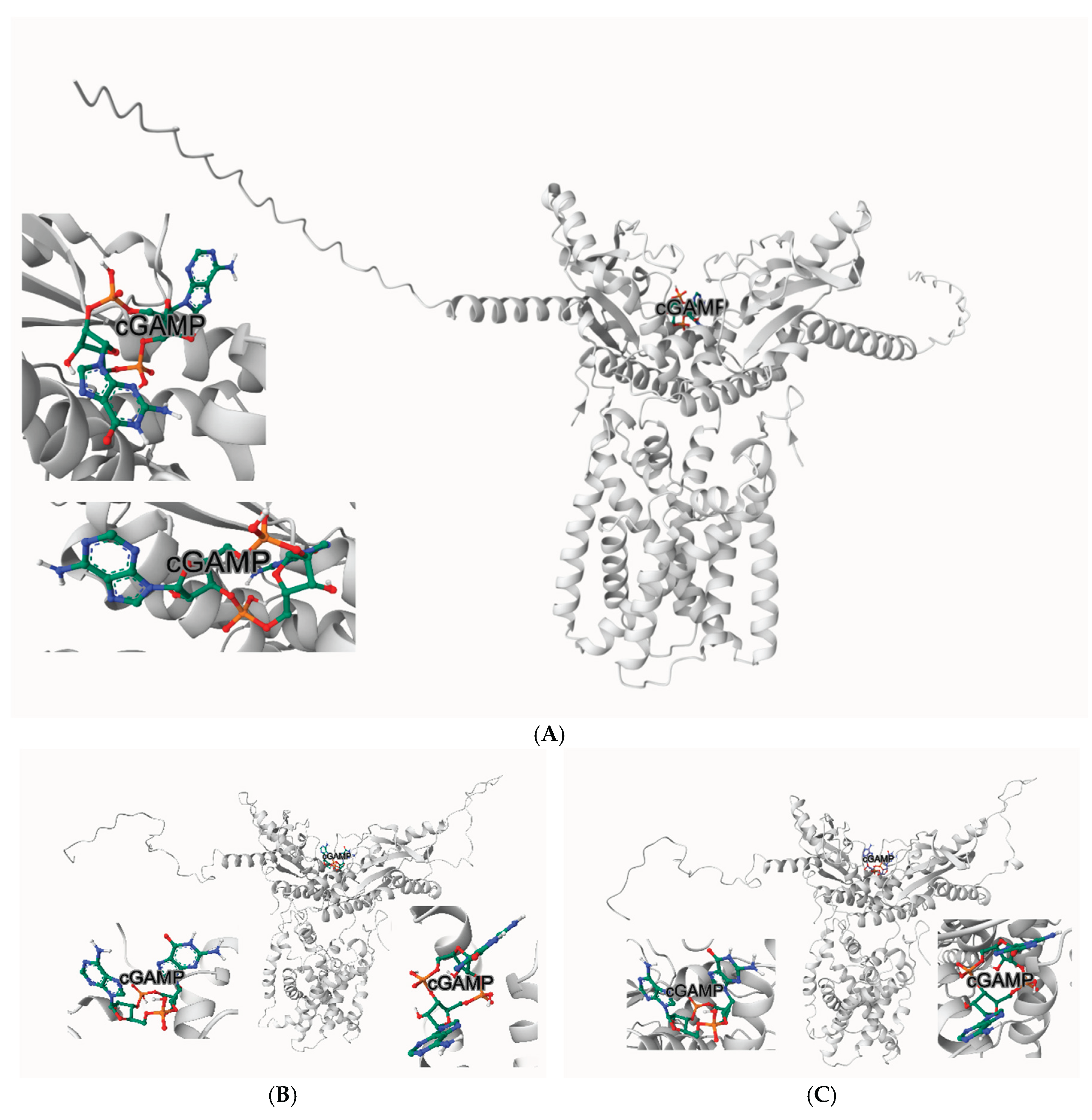

2.1. Novel Binding Pocket Near Tyr167/Thr263:

In our computational docking studies utilizing the DiffDock platform, we identified a previously unrecognized binding site for Excavatolide B (ExcB) and its derivatives on human STING (hSTING), highlighting a novel target at the cyclic dinucleotide (CDN)-binding domain (

Figure 1A). This site, located near residues

Tyr167 and Thr263, exhibits a significant predicted binding affinity of −9.3 kcal/mol, which we found to be particularly compelling in its interaction with the ExcB molecule(

Figure 1B). This newly discovered binding site is positioned in close proximity to the key residues of the CDN-binding domain, a region critical for the activation of hSTING by cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) [

3,

14]. The engagement of ExcB with this novel site suggests a mechanistic interference with productive cGAMP accommodation (see below), a pathway potentially capable of modulating STING activity and immune responses.

2.2. Visual Separation from Tyr167/Thr263

Zoom-in panels centered on Tyr167 and Thr263 demonstrate that ExcB sits at the cleft rim yet remains beyond H-bonding distance from both residues (

Figure 1C-D) (labels show minimum heavy-atom distances, Å; H-bond cutoff ≈ 3.5 Å / 0.35 nm). This visual check anticipates the MD outcome presented later: no Tyr167/Thr263 hydrogen bonds are sustained, and a single persistent polar anchor emerges instead—His157:NE2 → ExcB:O00—stabilizing the Site-2 pose without directly engaging Tyr167/Thr263.

The binding affinity at this site is further corroborated by AutoDock Vina GPU simulations, which predict values ranging from ΔG = −8.0 to −10.3 kcal/mol, demonstrating the robustness and consistency of these interactions. This finding underscores the potential of targeting this specific region of the CDN-binding domain as an innovative therapeutic approach. The spatial juxtaposition with residues implicated in cGAMP recognition, such as Tyr167 and Thr263, reinforces the relevance of this site in modulating (rather than mimicking) the conformational mechanics of STING activation.

While the previously well-characterized binding site involving residues Cys148 and Tyr240 (Site 1) has been recognized for its role in STING oligomerization and downstream signaling, the discovery of the Tyr167/Thr263 Site (Site-2) presents a fresh perspective. By focusing on this non-canonical rim pocket, our study provides new insights into how allosteric occupancy could bias cleft geometry and penalize CDN accommodation without direct competition. This opens up possibilities for the development of targeted therapeutic agents designed to fine-tune STING activity and its associated pathways.

2.3. Energy Minimization and Equilibration

Standard steepest-descents minimization and restrained NVT/NPT equilibration were applied to remove clashes and relax solvent density. No pocket-proximal distortions were observed; the complex proceeded to production MD under stable state points (details in Methods/SI).

The AF3 dimer was generated template-free and shows robust local and interface confidence: model-wide pLDDT ≈ 77 with gate residues high (His157 ≈ 90; Tyr167 ≈ 89; Thr263 ≈ 88), ipTM = 0.79, pTM = 0.80, and an inter-protomer PAE median ≈ 9.7 Å. We relaxed the model (short minimization + restrained equilibration) and observed no change around the gate/pocket. Full per-residue pLDDT and the PAE map are provided in the SI.

2.4. Production MD: Thermodynamic and Structural Stability

Over the 10-ns production trajectory, the system maintained stable thermodynamic state points (T = 300.0 ± 0.28 K, P = 1.07 ± 21.6 bar, ρ = 1002.6 ± 0.42 kg·m ⁻³; mean ± RMSD, from md.edr;

Figure 2A). Protein backbone RMSD rose during the initial relaxation then reached a plateau, consistent with a well- equilibrated fold, supporting the robustness of pocket readouts (

Figure 2B). The ligand RMSD (protein-aligned) similarly settled after the early frames, indicating a stable bound pose (

Figure 2C). Residue-wise RMSF showed a low baseline across most residues with peaks confined to termini/solvent-exposed loops, indicating moderate, localized flexibility consistent with a stable, well-folded protein. (

Figure 2D). The protein radius of gyration was essentially constant (≈3.56 ± 0.04 nm, 2–10 ns), supporting the absence of global compaction/expansion events and reflect local rearrangements rather than whole-protein collapse or swelling. (

Figure 2E), together indicating structural and thermodynamic stability that supports the single-anchor H-bond model and the subsequent cleft-mouth analysis.

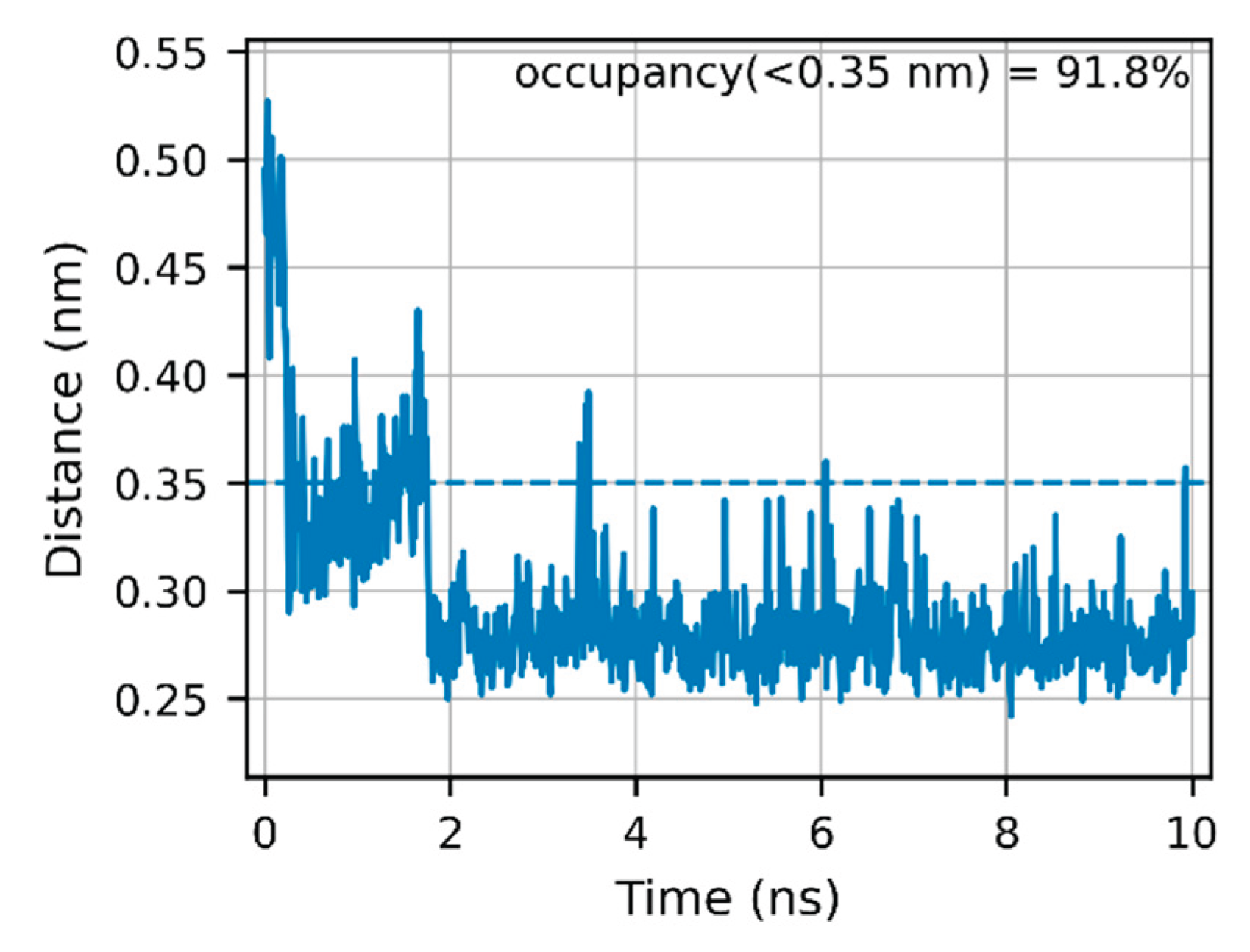

2.5. Protein–Ligand Hydrogen-Bonding Pattern

Over the full 0–10 ns window, the His157(NE2)–ExcB:O00 contact remains within hydrogen-bonding distance for 91.8% of frames; over the terminal 1 ns, the angle-qualified occupancy rises to ~97%. We therefore report both the conservative geometry-based contact fraction (0–10 ns) and the terminal-window occupancy to indicate stabilization after the brief ~0–2 ns relaxation (Fig. 3). Interactions to other ligand oxygens (e.g., O0G) occurred intermittently (<0.35 nm observed in subsets of frames), but no second persistent anchor was supported by our last-nanosecond analysis. Importantly, no water bridge was observed by either oxygen-only or hydrogen-resolved criteria (0.0% occupancy;

Figure 3). The His157–O00 anchor is thus the sole high-residency polar tether at Site 2 in our system (

Figure 3; Figure S1).

Note on prior assignment. Earlier exploratory mapping tentatively listed an Asn156 contact; re-indexing against the simulation topology revealed no Asn residue numbered 156 in this system (ASN resnr set: 61, 111, 131, 152, 154, 183, 187, 188, 211, 218, 242, 250, 307, 308). We therefore correct the anchor set to His157 only in the terminal window.

While anchored at Site-2, later frames indicate a gradual migration toward a buried variant of this pocket (Site-2’; defined below).

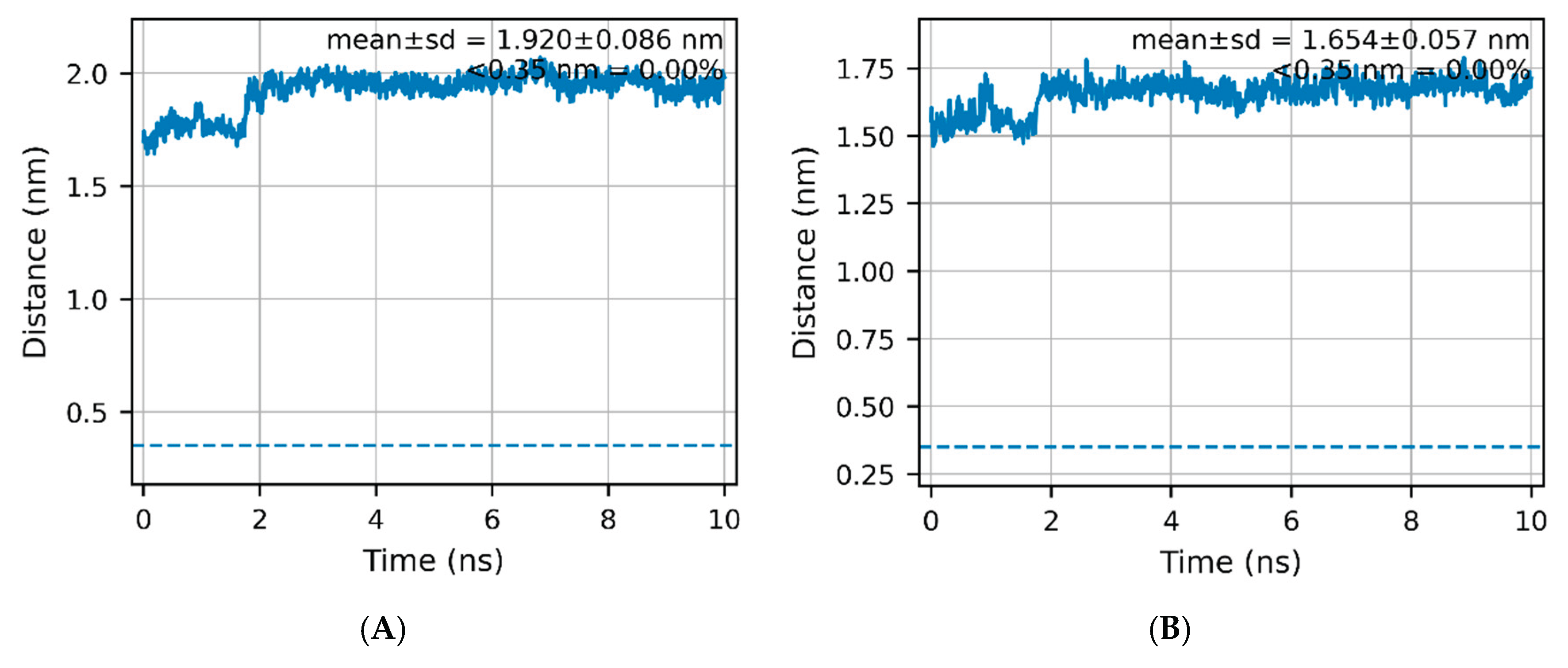

2.6. Targeted Assignment: Single Persistent H-Bond at His157; no Stable Asn156 Contact

In the last 1 ns, gmx hbond reported a single persistent protein–ligand H-bond, His157:NE2 → ExcB:O00, with ~97% occupancy and a mean donor–acceptor distance of 0.25 ± 0.04 nm. No water bridges were detected by either oxygen-only proximity (SOL:OW within 0.35 nm to both partners) or hydrogen-resolved donor criteria (0.0% occupancy). Asn156 did not meet the geometric cutoff (≤0.35 nm; ≥30°) for a persistent H-bond and is treated as a neighboring, non-persistent contact. Consistently, no direct Tyr167/Thr263 H-bonds were observed, and gmx mindist gave average minimal distances from the ligand to Tyr167 ≈ 1.86 nm and to Thr263 ≈ 1.67 nm—well beyond H-bond range (

Figure 4A-B).

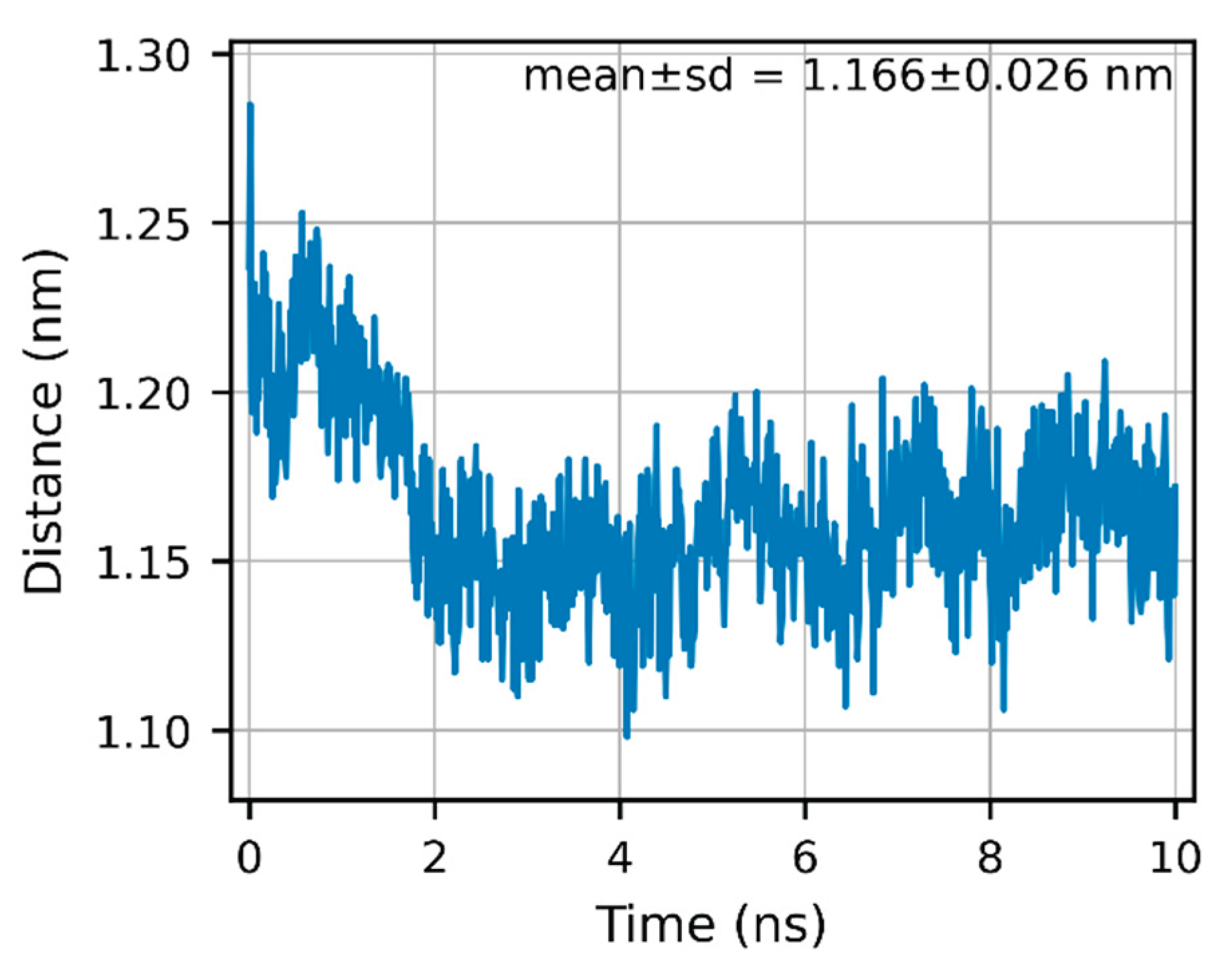

2.7. Local Conformational Readout: Ligand-Proximal Cleft “Mouth” Geometry

To avoid scale bias introduced by local atom subsets, we redefined the ligand-proximal cleft (“mouth”) geometry using a heavy-atom (non-hydrogen) center-of-mass to center-of-mass (COM–COM) metric: COMs were computed for all heavy atoms in residues 154–160 and 260–266, respectively, and evaluated on a de-periodized, centered trajectory over 0–10 ns. Under this stricter definition, the mouth distance averaged 1.166 ± 0.026 nm (n = 1001) and exhibited an “early compaction followed by a stable plateau” (

Figure 5; see SI: S-MD-2 and Data S4). Although this absolute value is larger than the previously reported 0.264 nm (derived from a local Cα-based metric with neighborhood filtering), the biological interpretation is unchanged: throughout 0–10 ns, we observe no progressive opening or relaxation; the mouth geometry remains stable and is consistent with our finding that minimum heavy-atom distances between the ligand and Tyr167/Thr263 remain well outside hydrogen-bonding range (

Figure 4A–B).

Across the full 0–10 ns window, the His157(NE2)–ligand O00 contact stayed within hydrogen-bonding distance for 91.8% of frames after a brief ~0–2 ns relaxation (Fig. 3). By contrast, the ligand’s minimum heavy-atom distances to Tyr167 and Thr263 were 1.920 ± 0.086 nm and 1.654 ± 0.057 nm, with 0.00% of frames below 0.35 nm (Fig. 4A–B). Together with the corrected mouth metric showing a stable cleft geometry (Fig. 5), these readouts support a His157-anchored accommodation without Tyr167/Thr263 engagement, consistent with the proposed two-step mechanism.

2.8. Competitive Docking Control with cGAMP (Baseline, Native AF3 Model)

On native hSTING (no ExcB), cGAMP achieved Vina scores of ~−10 to −11 kcal·mol⁻¹ and adopted the canonical CDN-like pose in the cleft, providing a baseline for productive accommodation and closure. (

Figure 6A)

2.8. Competitive Docking with cGAMP on ExcB-Stabilized Snapshots (9000/9160 ps)

We exported two MD snapshots (model_His157_O00_9000.000ps.pdb; model_His157_O00_9160.000ps.pdb) to probe cGAMP binding in the ExcB-preloaded cleft. Cavity-guided docking (detected cavities and predicted ligand-binding poses) still placed cGAMP near the CDN cleft for both snapshots but yielded lower Vina scores (~−8.6 kcal·mol ⁻¹) and displaced/flattened orientations versus canonical. In contrast, structure-based blind docking failed to recover the CDN site, favoring alternative surface grooves. Compared with the baseline, these results indicate that the His157-anchored Site-2 state penalizes cGAMP binding and perturbs the pose, consistent with allosteric occlusion (

Figure 6A–C; Table S1).

2.9. Functional Implications of Entrance (Site-2) and Buried (Site-2’) Poses

To separate direct competition from ExcB-conditioned conformational effects, we docked cGAMP and ExcB on the native receptor and on two MD snapshots (9000 ps, 9160 ps). Native docking supported an entrance-proximal Site-2 interaction (cGAMP −10.5; ExcB −9.3 kcal·mol ⁻¹). On both MD snapshots, cGAMP docking was uniformly weaker (−8.6/−8.8 kcal·mol ⁻¹) and unchanged by retaining the embedded, buried ExcB coordinates, consistent with a Site-2’ conformation that disfavors CDN binding independent of direct ligand–ligand overlap (pocket views in Fig. 6A–C; scores in Table S1). Taken together—stable thermodynamics, plateaued RMSD, constant Rg, and a small number of persistent hydrogen bonds in the terminal window—the 10 ns simulation supports continued ligand engagement accompanied by a transition from Site-2 to a buried Site-2’ rather than exclusive persistence at the entrance (Fig. 2A–D). Notably, the magnitude of the docking score decrease (~1.7–1.9 kcal·mol ⁻¹; ~18–25-fold, apparent) is similar at both Site-2 and Site-2’; the diagnostic difference is mechanistic —transient steric competition at Site-2 versus conformational gating at Site-2’, as the latter remains depressed whether the buried ExcB coordinates are retained or removed.

2.10. Docking-Workflow Benchmarking with SN-011 and Astin C

To verify that our AF3-based docking workflow reproduces canonical CDN-pocket pharmacology, we re-docked two reported antagonists—SN-011 and Astin C [

31,

32]—against the same receptor preparation used for ExcB. Top-ranked SN-011 poses recapitulated hallmark contacts within the CDN pocket (e.g., Ser162/Tyr167/His232/Arg238), aligning with published residue-level annotations. Astin C similarly reproduced its entrance-competitive placement and engagement of the Ser162/Tyr163/His232/Arg238 network. These checks support the credibility of our receptor model and pose-selection criteria; the identical workflow was then applied to ExcB to avoid method bias. Detailed benchmarking notes and overlays are summarized in Methods §4.8.

2.11. In-Silico ADMET and Developability

Aggregate in-silico readouts for Excavatolide B (ExcB) indicate encouraging developability with a few tractable liabilities. pkCSM predicts high GI absorption (~100%), moderate permeability (Caco-2 logPapp ≈ 0.411), low aqueous solubility (logS ≈ −4.883), limited CNS penetration (−logBB ≈ 1.698), and low dermal permeability (−logKp ≈ 0.14). Dose surrogates fall in mid ranges (LD50 ≈ 10^4.51 mg kg⁻¹; LOAEL ≈ 10^1.546 mg kg⁻¹ day⁻¹), with moderate predicted clearance (log ml min⁻¹ kg⁻¹ ≈ 0.372). These continuous endpoints are summarized in Fig. 7A and reported in Table S2.

Figure 7.

A. Concise developability readouts for Excavatolide B. Continuous ADMET endpoints are shown as min–max–scaled bars (0–1) for visualization; numeric labels are the raw predictor outputs. Metrics (left→right): GI Absorption (%), Caco-2 logPapp, Solubility (logS), CNS sparing (−logBB), Skin permeability (−logKp), LD50 (log mg/kg), LOAEL (log mg/kg/day), and Clearance (log ml/min/kg). 7B: Liability overview Top row repeats the continuous endpoints from Fig. 7A as a tile map; bottom row summarizes binary classifiers (P-gp inhibitor/substrate; CYP1A2/2C19/2C9/2D6/3A4 inhibitor/substrate; AMES, Hepatotoxicity, hERG I/II). Tiles aid readability only; interpretation should rely on the printed values/labels and the SI tables.

Figure 7.

A. Concise developability readouts for Excavatolide B. Continuous ADMET endpoints are shown as min–max–scaled bars (0–1) for visualization; numeric labels are the raw predictor outputs. Metrics (left→right): GI Absorption (%), Caco-2 logPapp, Solubility (logS), CNS sparing (−logBB), Skin permeability (−logKp), LD50 (log mg/kg), LOAEL (log mg/kg/day), and Clearance (log ml/min/kg). 7B: Liability overview Top row repeats the continuous endpoints from Fig. 7A as a tile map; bottom row summarizes binary classifiers (P-gp inhibitor/substrate; CYP1A2/2C19/2C9/2D6/3A4 inhibitor/substrate; AMES, Hepatotoxicity, hERG I/II). Tiles aid readability only; interpretation should rely on the printed values/labels and the SI tables.

Binary liabilities were not flagged by the models: predictions were negative for P-gp inhibition/substrate status and CYP liabilities (CYP1A2/2C19/2C9/2D6/3A4 inhibitor and CYP3A4 substrate). Safety classifiers were also negative for genotoxicity (AMES), hepatotoxicity (pkCSM probability ≈ 0.12 for the “non-hepatotoxic” class), and cardiac risk (hERG I/II inhibition). These no-liability calls are shown in Fig. 7B and detailed in Table S3.

Overall, the in-silico profile supports feasibility of oral exposure with solubility emerging as the principal optimization lever, minimal predicted transporter/CYP-mediated DDI risk, and no major toxicity alerts.

At time zero, ExcB samples an entrance-proximal Site-2 that can sterically compete with cGAMP. After relaxation, the receptor adopts a buried Site-2′ geometry that conformationally penalizes cGAMP docking even when ExcB coordinates are removed (Fig. 6).

3. Discussion

Our data support a two-step inhibitory model in which ExcB transitions from an entrance-proximal pose (Site-2) to a more stable buried pose (Site-2’) that conditions human STING into a CDN-averse conformation. In the native/open state (time 0), ExcB samples the CDN entrance where it partially overlaps the canonical CDN volume and can directly disfavor cGAMP binding (native docking: cGAMP −10.5 vs. ExcB −9.3 kcal·mol ⁻¹). Following MD, ExcB relocates toward a buried position (Site-2’), and cGAMP docking to these ExcB-conditioned snapshots becomes consistently weaker (−8.6 and −8.8 kcal·mol ⁻¹ for 9000 ps and 9160 ps, respectively). Importantly, the cGAMP scores do not decrease further when the embedded ExcB coordinates are explicitly retained during docking, indicating that the dominant penalty reflects receptor conformation rather than persistent steric clash at these time points.

Functionally, ExcB thus behaves as a conformational antagonist. In step one (Site-2), transient entrance engagement can sterically intrude into the CDN pocket and compete with cGAMP; in step two (Site-2’), ExcB stabilizes a partially closed/occluded pocket geometry that intrinsically weakens CDN recognition even in the absence of direct ExcB–cGAMP overlap. Using the heuristic K d∼eΔG/RT (RT≈0.593 kcal·mol ⁻¹), the 1.9 and 1.7 kcal·mol ⁻¹ losses from native imply ~24.6-fold and ~17.6-fold apparent affinity weakenings for cGAMP on the Site-2’–conditioned conformations, providing an intuitive magnitude for the conformational effect.

This framework reconciles three observations that, taken alone, could seem contradictory: (i) time-0 docking shows direct competition at the entrance (Site-2); (ii) MD snapshots show ExcB relocation into a buried position (Site-2’); and (iii) blind pocket-based redocking does not automatically reproduce the buried ExcB pose on later frames. The latter is expected because the entrance becomes narrower and the inner cavity is cryptic; a solvent-exposed pocket finder will prioritize the now-dominant surface grooves unless one uses a guided box or seeds the MD-observed ExcB coordinates before local refinement.

At a molecular level, our figures show polar contacts consistent with hydrogen bonding in both steps. We emphasize geometry-based contact fractions over per-residue angle-qualified occupancies except where explicitly stated (e.g., His157–O00 in Fig. 3), to avoid over-interpreting transient angle noise; the term “H-bonding” is used as a mechanistic placeholder based on visual inspection that the poses are stabilized by complementary polar interactions at the entrance (Site-2) and later within the inner pocket (Site-2’). Future work can quantify per-residue occupancies to convert this qualitative picture into a residue-resolved map of entrance-rim vs. inner-pocket interactions across time. Notably, all three metrics exhibit a brief initial relaxation phase (~0–2 ns), after which the system stabilizes; the conclusions reported above are based on the full 0–10 ns window rather than a late-segment snapshot, mitigating selection bias (Figs. 3–5; SI S-MD-1/S-MD-2; Data S1–S4).

The two-step Site-2 → Site-2’ model is experimentally testable. First, entrance-rim mutations (≈165–170/260–266) that reduce donor/acceptor capacity should diminish Site-2 sampling, lessen initial competition, and partially rescue cGAMP binding on the native/open receptor. Second, inner-pocket mutations predicted to stabilize Site-2’ (polar donors/acceptors or hydrophobic clamps) should exacerbate the conformational penalty to cGAMP, whereas mutations that disfavor Site-2’ should restore docking scores toward native. Third, pocket metrics (fpocket volume, water accessibility, or HDX-MS protection around the entrance loop) should report a smaller/less solvent-accessible CDN cavity on Site-2’-conditioned frames. Finally, cellular assays should show right-shifted cGAMP dose–responses after ExcB pre-exposure—even after washout—consistent with a lingering conformational latch.

For recent scope of 10-ns MD, our explicit-solvent trajectories were deliberately scoped to the early-time anchoring regime at the CDN rim. Backbone/Ligand RMSD plateauing, constant Rg, and near-unity occupancy of the His157:NE2→ExcB:O00 hydrogen bond over the terminal window collectively indicate a statistically converged local state sufficient to substantiate the Site-2→Site-2’ mechanism. Longer (≥100 ns) replicas will be pursued as future work to refine kinetics and rare transitions but are not required for the conceptual model established here.

Limitations are noted that docking scores are not ΔG; fold-change conversions are heuristic. The MD windows probed are finite and sensitive to protonation/ionic conditions. H-bond identification from static frames can miss water-mediated bridges. Nevertheless, the concordance between (a) entrance competition at time 0, (b) ExcB burial on MD, and (c) a stable, ExcB-independent reduction in cGAMP docking on two independent snapshots strongly supports the proposed Site-2 → Site-2’ inhibitory pathway.

Translational integration of ADMET with mechanism and indication. Interpreted through the lens of non-activating, gate-closing STING antagonism, our in-silico ADMET profile supports the intended peripheral, gut-localized pharmacology for intestinal inflammation/CRC. Predicted high intestinal absorption combined with low BBB penetration favors oral or colon-targeted delivery to achieve mucosal target engagement without CNS exposure. Tool-to-tool variability in CYP liabilities and efflux is treated as a risk register that we will resolve using microsomal stability, CYP inhibition/induction panels, and MDCK-MDR1 assays, selected specifically because polypharmacy is common in IBD/CRC. Preliminary hERG/AMES screens are reassuring but will be experimentally confirmed alongside mouse PK emphasizing colon tissue:plasma ratios and STING-pathway pharmacodynamic readouts. Collectively, these results position ExcB as a peripherally acting STING gate-closer with a development path tightly coupled to its mechanism and intended clinical context.

In summary, ExcB appears to inhibit human STING through a phase-dependent mechanism: initial competitive sampling at the CDN entrance followed by conformational locking in a buried pocket. This model provides a coherent explanation for our docking/MD observations and offers clear design levers for modulators that target either entrance sampling (to block activation acutely) or inner-pocket stabilization (to enforce a CDN-averse conformation chronically).

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. AlphaFold3 Structural Modeling

The amino acid sequence of human Stimulator of Interferon Genes (hSTING) was obtained from the NCBI Protein Database (accession: NP_079510.1) in FASTA format. Structure prediction was performed using AF3, either through a local installation or a cloud-based environment (e.g., Google Colab) [

13]. The resulting 3D structure was validated using predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT) scores to confirm model reliability.

4.2. Ligand Design and Optimization

The chemical structure of Excavatolide B (ExcB) was drawn using a chemical sketching tool (e.g., ChemDraw) and exported in SMILES format. RDKit was employed for 3D structure generation, followed by geometry optimization and energy minimization using Universal Force Field (UFF) or MMFF94 [

14] to yield the lowest energy conformation suitable for docking.

4.3. Ligand Preparation and DiffDock Docking

The optimized hSTING and ExcB structures set were processed using RDKit and Open Babel to convert ligand structures into 3D formats [

15]. High-throughput docking was conducted using DiffDock, an AI -guided blind docking tool capable of rapid pose generation and scoring [

16]. Output poses were evaluated based on spatial alignment and docking score, and top-ranked complexes were selected for further analysis.

4.4. GPU-Accelerated Docking Validation Using AutoDock Vina

Top docking poses from DiffDock were re -evaluated using AutoDock Vina (GPU-accelerated) for quantitative binding affinity scoring [ 17]. Ligands and hSTING were converted to the PDBQT format using AutoDockTools (ADT), with appropriate assignment of torsions, hydrogens, and atom types. Docking boxes were defined to encompass the predicted binding regions. GPU-accelerated docking simulations were executed to generate affinity values (kcal/mol) for each ligand-receptor pair. Post-docking visualization and qualitative interaction review were performed using PyMOL [

18] and UCSF Chimera [

19].

4.5. Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Hydrogen-Bond Analyses

Engine and force fields. Simulations were performed in GROMACS 2022.2 [

20] using OPLS-AA/OPLS-AA/L for the protein [

21,

22]. Ligand parameters were generated with LigParGen in OPLS format and harmonized to avoid duplicate atomtypes at topology assembly [

23].

System preparation. The top-ranked docked complex was solvated in a periodic triclinic box with ≥1.0 nm solute–edge padding using TIP4P water; Na⁺/Cl⁻ ions were added to neutralize net charge (physiological ionic strength where specified) [

24].

Equilibration and production. Energy minimization used steepest descents to F_max ≤ 1000 kJ mol⁻¹ nm⁻¹, followed by restrained NVT, then NVT at 300 K with the velocity-rescale thermostat (τ_T = 0.1 ps) [

25], and NPT at 300 K/1 bar with the Parrinello–Rahman barostat (τ_P = 2.0 ps, isotropic) [

26]. Production MD ran 10 ns with 2 fs time step. Long-range electrostatics employed PME (real-space cutoff 1.0–1.12 nm) with Verlet neighbor lists [

27,

28]; bonds to hydrogens were constrained with LINCS [

29]. Short-range nonbonded and PME kernels were GPU-accelerated [

30].

Trajectory processing and global metrics. Trajectories were de-periodized (-pbc mol), centered, and backbone-fitted before analysis. We report backbone RMSD, ligand heavy-atom RMSD, Cα RMSF, and R_g; thermodynamic observables were taken from md.edr.

Distance-based readouts. Minimum heavy-atom distances were computed for (i) His157(NE2) ↔ ligand O00 (anchor contact) and (ii) ligand ↔ Tyr167/Thr263 residue heavy atoms, over 0–10 ns. For stability summaries, we report the geometric contact fraction (fraction of frames with d < 0.35 nm) rather than angle-qualified occupancies to avoid method-specific sensitivity.

Hydrogen bonds. H-bonds between Protein and Ligand (resname UNK) were identified with gmx hbond using distance ≤ 0.35 nm and angle ≥ 30°. Where reported, occupancies were computed over 0–10 ns; for His157↔O00 we additionally report a terminal-window (last 1 ns) angle-qualified occupancy.

Water bridges. Bridges were counted under two criteria: (1) oxygen-only proximity (SOL:OW within 0.35 nm of both partners) and (2) donor-resolved (the same water’s hydrogens within 0.25 nm to each acceptor). Unless noted, occupancies were evaluated over 0–10 ns.

Cleft-mouth metric. We computed centers of mass (COMs) for all heavy (non-hydrogen) atoms in residues 154–160 and 260–266, respectively. Distances between these COMs were evaluated on the de-periodized, centered, and backbone-aligned trajectory to generate a 0–10 ns COM–COM time series (Data S4; corresponds to

Figure 5).

4.6. Competitive Docking on ExcB-Conditioned MD Snapshots

To test whether ExcB inhibits cGAMP binding by direct competition versus conformational occlusion, we performed docking on MD snapshots in which ExcB had migrated/buried and altered the CDN pocket geometry. Receptors were taken from the 9.0-ns and 9.16-ns frames (“9000 ps” and “9160 ps”; chains and protonation states as prepared for MD). For the ExcB-conditioned controls, receptors retained the ExcB coordinates observed in the MD frames (“buried ExcB”); cGAMP was then docked against these receptors without removing the ExcB atoms. Docking was done with AutoDock Vina GPU using default parameters.

For pose extraction and visualization, PDB bundles were loaded into PyMOL; any protein present in the docking bundle was first superposed onto the target receptor (CEalign), and the non-polymer ligand was isolated for display. The native STING + cGAMP view (

Section 4) served as the reference camera; the same camera was reused for all panels to ensure a consistent field of view around the CDN pocket. Top-ranked docking scores (kcal/mol) were recorded for: native + cGAMP; native + ExcB; 9000 ps + cGAMP; 9000 ps + ExcB(buried) + cGAMP; 9160 ps + cGAMP; 9160 ps + ExcB(buried) + cGAMP. Where noted, differences in scores were converted to intuitive fold -changes via the heuristic Kd∼eΔG/RT (RT ≈ 0.593–0.616 kcal·mol−1), used only for interpretation of relative trends.

4.7. ADMET Profiling

Complementing the mechanism, in-silico ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) was profiled to assess developability beyond target binding. Predictions were generated with ADMETlab [

33], pkCSM [

34], and ProTox-II [

35] for oral absorption (e.g., Caco-2 permeability, P-glycoprotein interaction), systemic bioavailability, blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration, plasma protein binding, CYP450 metabolism (CYP1A2, CYP2D6, CYP3A4), renal excretion, and toxicity endpoints (e.g., LD₅₀, hERG inhibition, carcinogenicity).

4.8. Benchmark Docking Controls

Using the AF3-prepared hSTING dimer and the identical preprocessing used for ExcB (protonation, PDBQT conversion, box definition), we docked SN-011 and Astin C [

31,

32] with DiffDock → Vina-GPU re-scoring. Poses were retained if they reproduced literature-reported orientations or residue contacts within the CDN cleft/entrance (Ser162/Tyr163/Tyr167/His232/Arg238). The same camera and superposition pipeline (PyMOL/CEalign) was used for all figures to ensure direct visual comparison with ExcB. No parameter tuning specific to any ligand was introduced between benchmarks and ExcB production runs.

5. Conclusions

Docking and explicit-solvent MD support a two-state, allosteric ExcB mechanism at the STING CDN cleft: an entrance Site-2 that can transiently compete with cGAMP, followed by a buried Site-2’ that locks a gate-closed, CDN-averse geometry. The complex is stable over 10 ns and features a single persistent H-bond (His157:NE2↔ExcB:O00, ~97% occupancy) with no Tyr167/Thr263 H-bonds. On ExcB-conditioned snapshots, cGAMP docking scores are ~1.7–1.9 kcal·mol⁻¹ poorer (~18–25× apparent) and unchanged by retaining/removing buried ExcB, indicating conformational occlusion rather than direct clash. Together, these data position ExcB and its analogs as tunable, non-activating STING antagonists and motivate His157/Tyr167/Thr263 mutagenesis and competition assays to dissect Site-2 vs Site-2’ contributions. As a result, our conclusions rest on a converged early-time conformational latch that is internally consistent across docking and MD, while extended-timescale sampling is reserved for hypothesis-refinement rather than as a prerequisite for mechanism establishment.

Complementing the mechanism, in-silico ADMET profiling supports a drug-like, orally viable and peripherally acting profile for ExcB and close analogs—high predicted GI absorption with adequate permeability, manageable solubility, low BBB penetration, and no dominant safety flags (Ames/hERG/hepatotoxicity). These model-based signals argue for advancing to focused ADME/Tox confirmation (permeability/efflux, microsomal stability/CYP, hERG/DILI) and rodent PK to verify exposure and peripheral restriction, aligning developability with the non-activating STING mechanism.

Supplementary Material

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Abbreviations

| ADMET |

Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity |

| AF3 |

AlphaFold3 |

| BBB |

Blood–brain barrier |

| CDN |

Cyclic dinucleotide |

| cGAMP |

2’,3’-cyclic GMP –AMP |

| cGAS |

Cyclic GMP–AMP synthase |

| CNS |

Central nervous system |

| COM |

Center of mass |

| CRC |

Colorectal cancer (in context, colitis-associated colorectal cancer) |

| DDI |

Drug–drug interaction |

| DiffDock |

SE(3)-equivariant diffusion-based docking model |

| GI |

Gastrointestinal |

| GROMACS |

Groningen Machine for Chemical Simulations |

| HDX-MS |

Hydrogen–deuterium exchange mass spectrometry |

| hERG |

Human ether-à-go-go–related gene (KCNH2) potassium channel |

| hSTING |

Human Stimulator of Interferon Genes |

| IFN-I |

Type I interferon |

| IRF3 |

Interferon regulatory factor 3 |

| LINCS |

Linear Constraint Solver |

| LigParGen |

Ligand Parameter Generator |

| LOAEL |

Lowest observed adverse effect level |

| MD |

Molecular dynamics |

| NF-κB |

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells |

| NPT |

Isothermal–isobaric ensemble (constant N, P, T) |

| NVT |

Canonical ensemble (constant N, V, T) |

| OPLS-AA |

Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations—All-Atom |

| OPLS-AA/L |

OPLS-AA protein force-field variant with updated torsions |

| PDB |

Protein Data Bank |

| PDBQT |

PDB format with partial charges and AutoDock atom types |

| PK |

Pharmacokinetics |

| PME |

Particle-mesh Ewald |

| PR (Parrinello–Rahman) |

Parrinello–Rahman barostat |

| ProTox-II |

In-silico toxicity prediction web server |

| PyMOL |

The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System |

| R_g |

Radius of gyration |

| RMSD |

Root-mean-square deviation |

| RMSF |

Root-mean-square fluctuation |

| STING |

Stimulator of Interferon Genes |

| TBK1 |

TANK-binding kinase 1 |

| TIP4P |

Transferable Intermolecular Potential with 4 Points (water model) |

| TME |

Tumor microenvironment |

| UCSF Chimera |

Molecular visualization system |

| Vina |

AutoDock Vina docking engine |

| v-rescale |

Velocity-rescale thermostat |

References

- Zhang, X.; Bai, X.-C.; Chen, Z.-J. Structures and Mechanisms in the cGAS–STING Innate Immune Pathway. Immunity 2020, 53(1), 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ergun, S. L.; Fernandez, D.; Weiss, T. M.; Li, L. STING Polymer Structure Reveals Mechanisms for Activation, Hyperactivation, and Inhibition. Cell 2019, 178(2), 290–301.e10. [CrossRef]

- Shang, G.; et al. Cryo-EM structures of STING reveal its activation by cyclic GMP–AMP. Nature 2019, 567, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, K.; et al. A non-nucleotide agonist that binds covalently to cysteine 91 of human STING. Communications Biology 2022, 5, 1164. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, L.; et al. Reactive oxygen species oxidize STING and suppress cGAS–STING signaling. eLife 2020, 9:e57837.

- Zamorano-Cuervo, N.; et al. Pinpointing cysteine oxidation sites by high-resolution proteomics reveals Cys148/Cys206 regulation in STING. Sci. Signal. 2021, 14(690):eaw4673.

- Humphries, F.; et al. Targeting STING oligomerization with small-molecule inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120(30):e2303648120.

- Lin, Y.-Y.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory and Analgesic Effects of the Marine-Derived Compound Excavatolide B. Mar. Drugs 2015, 13, 2550–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-Y.; et al. Excavatolide B Attenuates Rheumatoid Arthritis through the Inhibition of Osteoclastogenesis. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15(1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-K.; et al. Marine-derived STING inhibitors, excavatolide B promote wound repair in full-thickness-incision rats. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 155, 114593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.; Yang, X.-W.; et al. Marine-Derived Alternariol Suppresses Inflammation by Regulating T-Cell Activation and Migration. Mar. Drugs 2025, 23(3):339.

- Li, G.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, X.-W.; et al. New anti-inflammatory guaianes from an algal-derived Aspergillus sp. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1055. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Jumper, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RDKit: Landrum, G. RDKit: Open-source cheminformatics; (accessed 2025).

- O’Boyle, N.M.; et al. Open Babel: An open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminform. 2011, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, G.; et al. DiffDock: Diffusion steps, twist, and docking via SE(3)-equivariant diffusion. ICLR 2023 (and arXiv:2210.01776).

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PyMOL: The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.x; Schrödinger, LLC.

- Pettersen, E.F.; et al. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; et al. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 19–25.

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Maxwell, D.S.; Tirado-Rives, J. Development and testing of the OPLS all-atom force field. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 11225–11236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, G.A.; Friesner, R.A.; Tirado-Rives, J.; Jorgensen, W.L. Evaluation and Reparametrization of the OPLS-AA Force Field for Proteins via Comparison with Accurate Quantum Chemical Calculations on Peptides. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 6474–6487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodda, L.S.; et al. LigParGen: An automatic OPLS-AA parameter generator for organic ligands. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W331–W336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, W.L.; Chandrasekhar, J.; Madura, J.D.; Impey, R.W.; Klein, M.L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussi, G.; Donadio, D.; Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007, 126, 014101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrinello, M.; Rahman, A. Polymorphic transitions in single crystals: A new MD method. J. Appl. Phys. 1981, 52, 7182–7190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páll, S.; Hess, B. A flexible algorithm for calculating pair interactions on SIMD architectures. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2013, 184, 2641–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essmann, U.; et al. A smooth particle-mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995, 103, 8577–8593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, B.; Bekker, H.; Berendsen, H.J.; Fraaije, J.G. LINCS: A linear constraint solver. J. Comput. Chem. 1997, 18, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutzner, C.; Páll, S.; Fechner, M.; Esztermann, A.; de Groot, B.L.; Grubmüller, H. Best bang for your buck: GPU nodes for GROMACS biomolecular simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Z.; et al. STING inhibitors target the cyclic dinucleotide binding pocket. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118(24): e2105465118.

- Li, S.; et al. Astin C blocks the activation pocket of STING. Cell Reports 2018, 25(11): 2937–2950.

- Xiong, G.; et al. ADMETlab 2.0: An integrated online platform for ADMET prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W5–W14. 2021; 49, W5–W14.

- Pires, D.E.V.; Blundell, T.L.; Ascher, D.B. pkCSM: Predicting small-molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using graph-based signatures. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 4066–4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, P.; et al. ProTox-II: Prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W257–W263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).