Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Motivation

1.1.1. Challenges of Typhoon Track Forecasting over Complex Terrain

1.1.2. Topographic Steering Mechanisms and Track Uncertainty

1.1.3. PV-Based Dynamic Modeling and Motivation for This Study

1.2. Objectives and Contribution

1.2.1. Research Objectives

1.2.2. Paper Organization

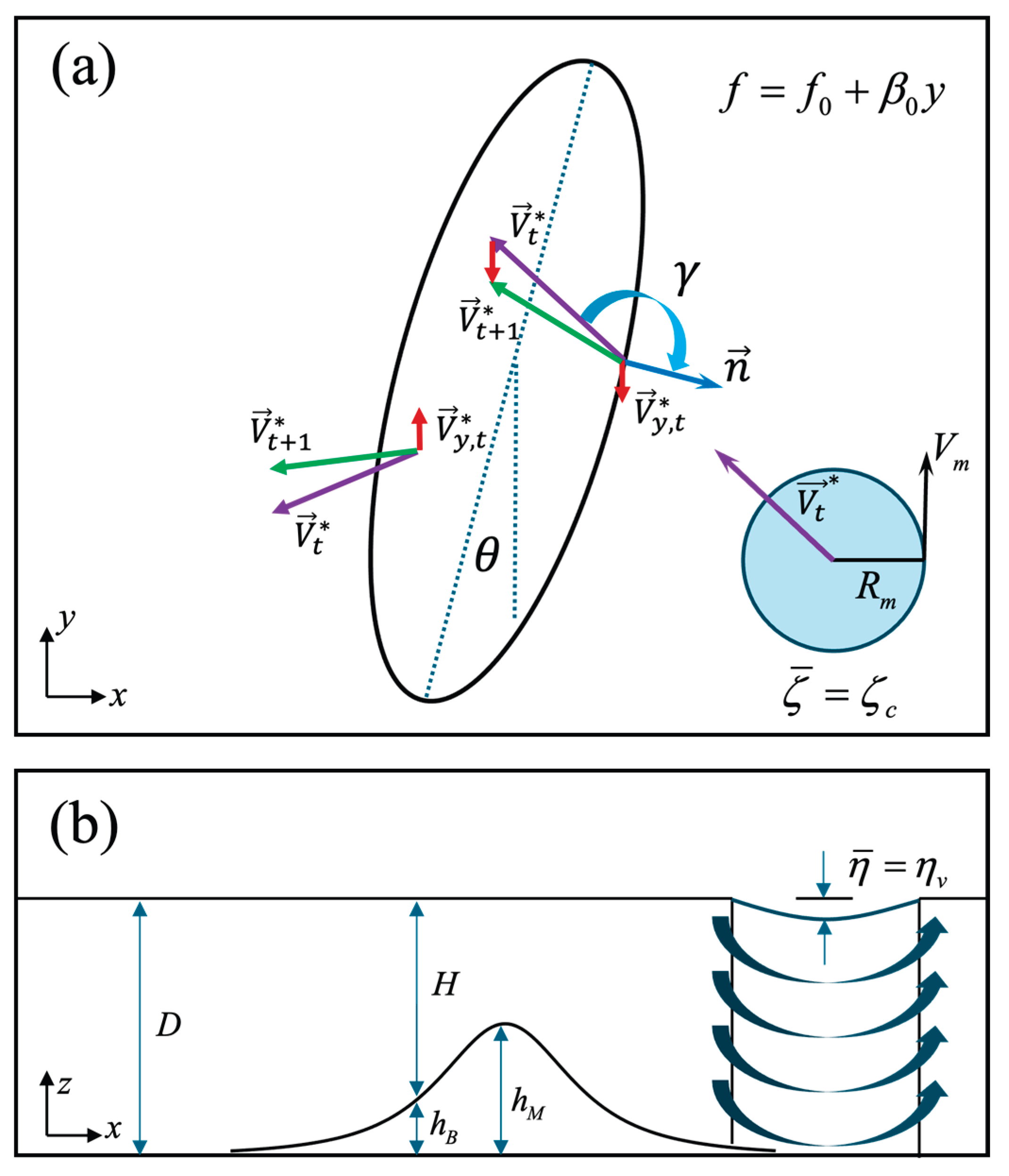

2. Theoretical Framework of the Dynamic Model

2.1. Governing Equations and Key Assumptions

2.2. Meridional Adjusting Velocity and Track Evolution

2.3. Physical Interpretation and Key Findings from Chen [35]

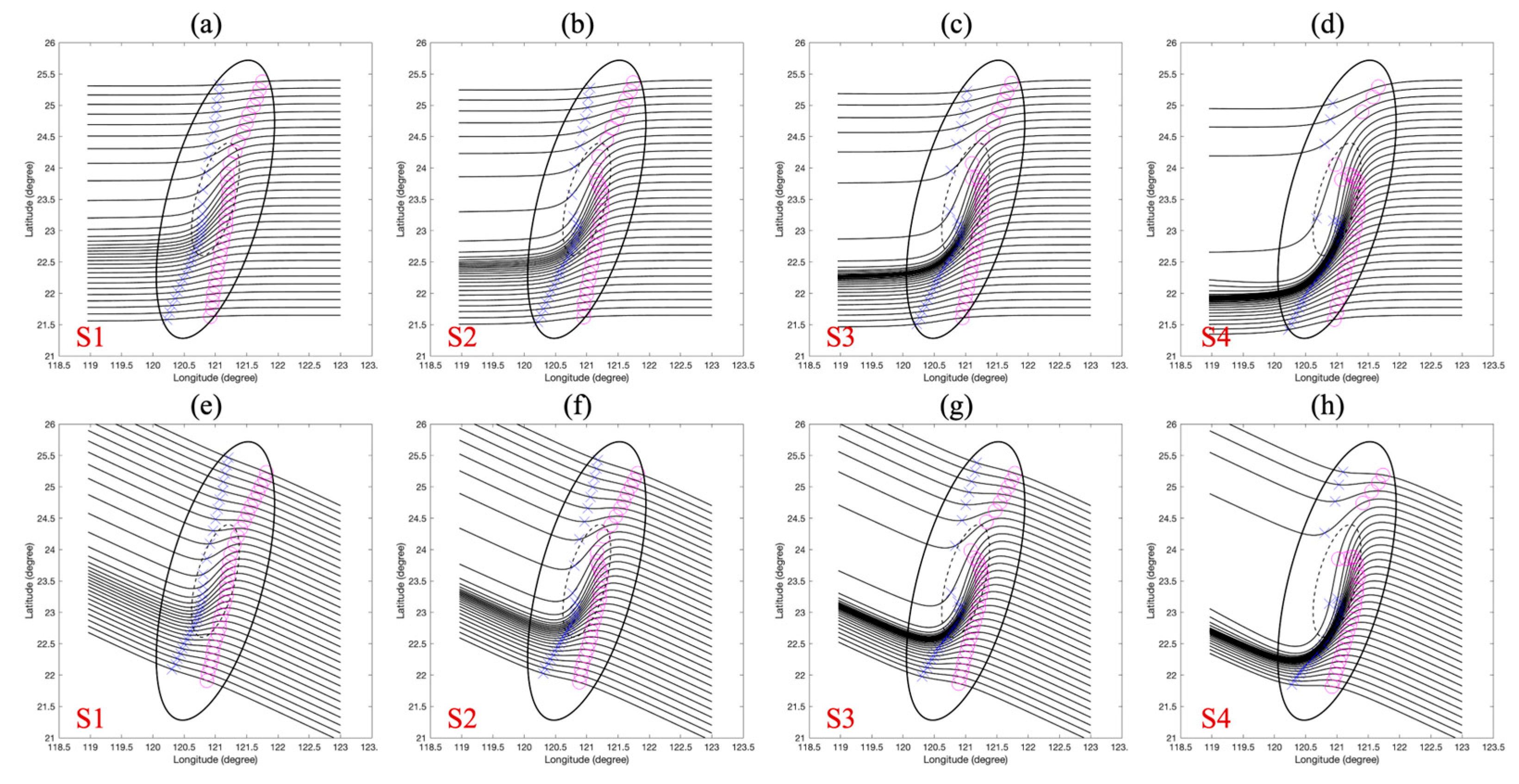

3. Fundamental Steering Mechanisms and Track Morphology over Idealized Terrain

3.1. Idealized Terrain Configuration and Experimental Design

3.1.1. Idealized Topography Settings

3.1.2. Typhoon-like Vortex Initialization

| Figure | Vortex | (deg) | (hrs) | (hrs) | ||||||||

| 3(a) | S1 | 40 | 200 | 0.0004 | 3.7 | 32.1 | 195 | 0.125 | 20.83 | 12.50 | 151 | -62 |

| 3(b) | S2 | 40 | 150 | 0.0005 | 4.9 | 55.3 | 195 | 0.125 | 20.83 | 13.00 | 347 | -84 |

| 3(c) | S3 | 30 | 100 | 0.0006 | 5.5 | 92.4 | 195 | 0.125 | 20.83 | 13.25 | 616 | -89 |

| 3(d) | S4 | 30 | 75 | 0.0008 | 7.3 | 160.9 | 195 | 0.125 | 20.83 | 13.58 | 1128 | -98 |

| 3(e) | S1 | 40 | 200 | 0.0004 | 3.7 | 32.1 | 170 | 0.125 | 22.92 | 12.62 | 140 | -61 |

| 3(f) | S2 | 40 | 150 | 0.0005 | 4.9 | 55.3 | 170 | 0.125 | 22.92 | 13.42 | 358 | -84 |

| 3(g) | S3 | 30 | 100 | 0.0006 | 5.5 | 92.4 | 170 | 0.125 | 22.92 | 13.88 | 738 | -92 |

| 3(h) | S4 | 30 | 75 | 0.0008 | 7.3 | 160.9 | 170 | 0.125 | 22.92 | 14.54 | 1410 | -100 |

| 4(a) | S1 | 40 | 200 | 0.0004 | 3.7 | 32.1 | 145 | 0.125 | 31.25 | 15.75 | 195 | -69 |

| 4(b) | S2 | 40 | 150 | 0.0005 | 4.9 | 55.3 | 145 | 0.125 | 31.25 | 17.42 | 667 | -92 |

| 4(c) | S3 | 30 | 100 | 0.0006 | 5.5 | 92.4 | 145 | 0.125 | 31.25 | 18.33 | 1180 | -99 |

| 4(d) | S4 | 30 | 75 | 0.0008 | 7.3 | 160.9 | 145 | 0.125 | 31.25 | 19.5 | 983 | -100 |

| 4(e) | S1 | 40 | 200 | 0.0004 | 3.7 | 32.1 | 125 | 0.125 | 50.00 | 24.58 | 462 | -87 |

| 4(f) | S2 | 40 | 150 | 0.0005 | 4.9 | 55.3 | 125 | 0.125 | 50.00 | 28.83 | 2029 | -100 |

| 4(g) | S3 | 30 | 100 | 0.0006 | 5.5 | 92.4 | 125 | 0.125 | 50.00 | 30.67 | 2770 | -100 |

| 4(h) | S4 | 30 | 75 | 0.0008 | 7.3 | 160.9 | 125 | 0.125 | 50.00 | 32.92 | 0 | -100 |

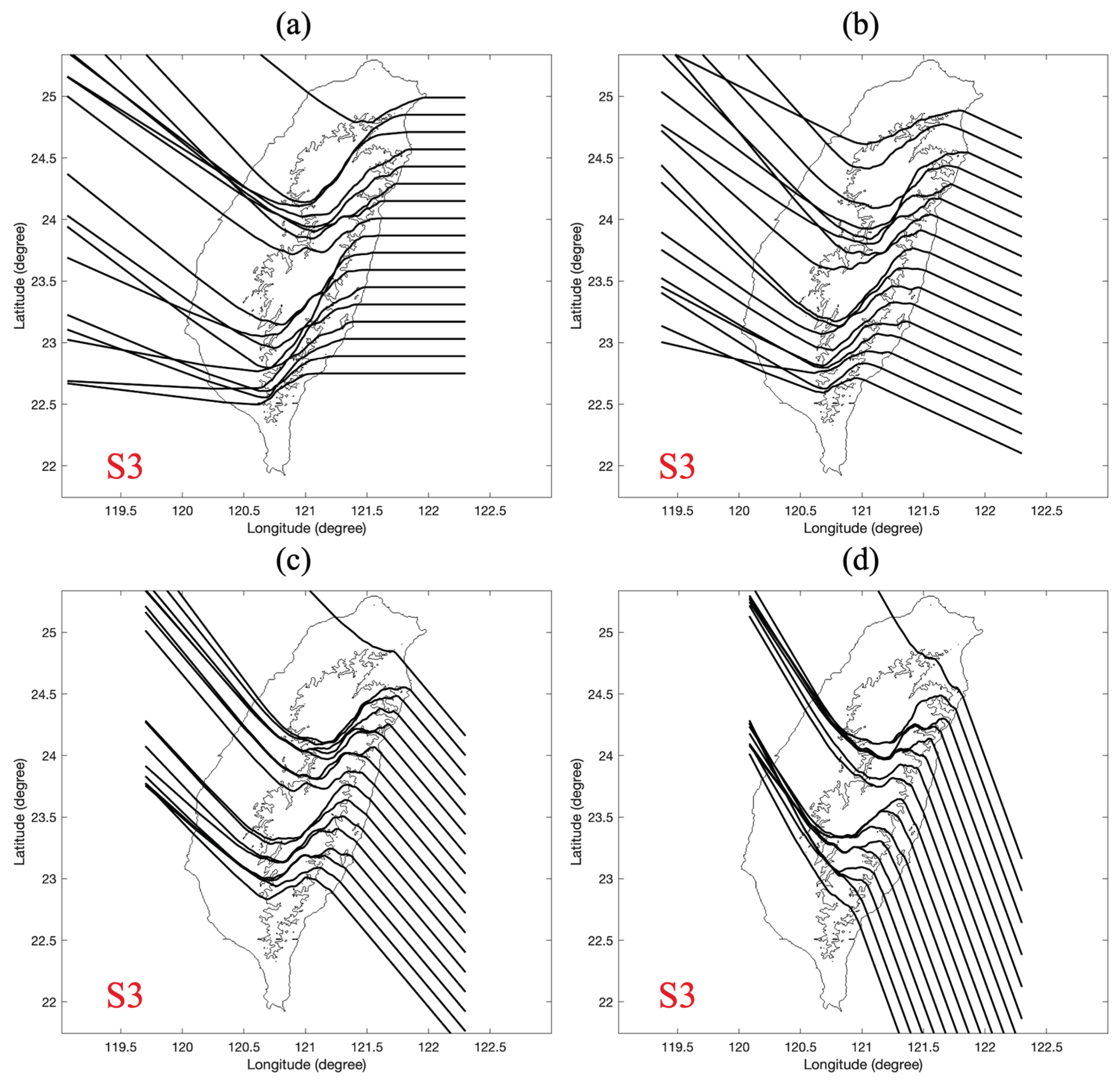

| 9(a) | S3 | 30 | 100 | 0.0006 | 5.5 | 92.4 | 195 | 0.120 | 16.67 | 6.38 | 2456 | -96 |

| 9(b) | S3 | 30 | 100 | 0.0006 | 5.5 | 92.4 | 170 | 0.160 | 16.67 | 7.08 | 7034 | -99 |

| 9(c) | S3 | 30 | 100 | 0.0006 | 5.5 | 92.4 | 145 | 0.160 | 20.83 | 9.46 | 637 | -89 |

| 9(d) | S3 | 30 | 100 | 0.0006 | 5.5 | 92.4 | 125 | 0.260 | 33.33 | 16.54 | 2057 | -96 |

| * For comparison, all parameters are calculated with reference to a latitude of 22°N. | ||||||||||||

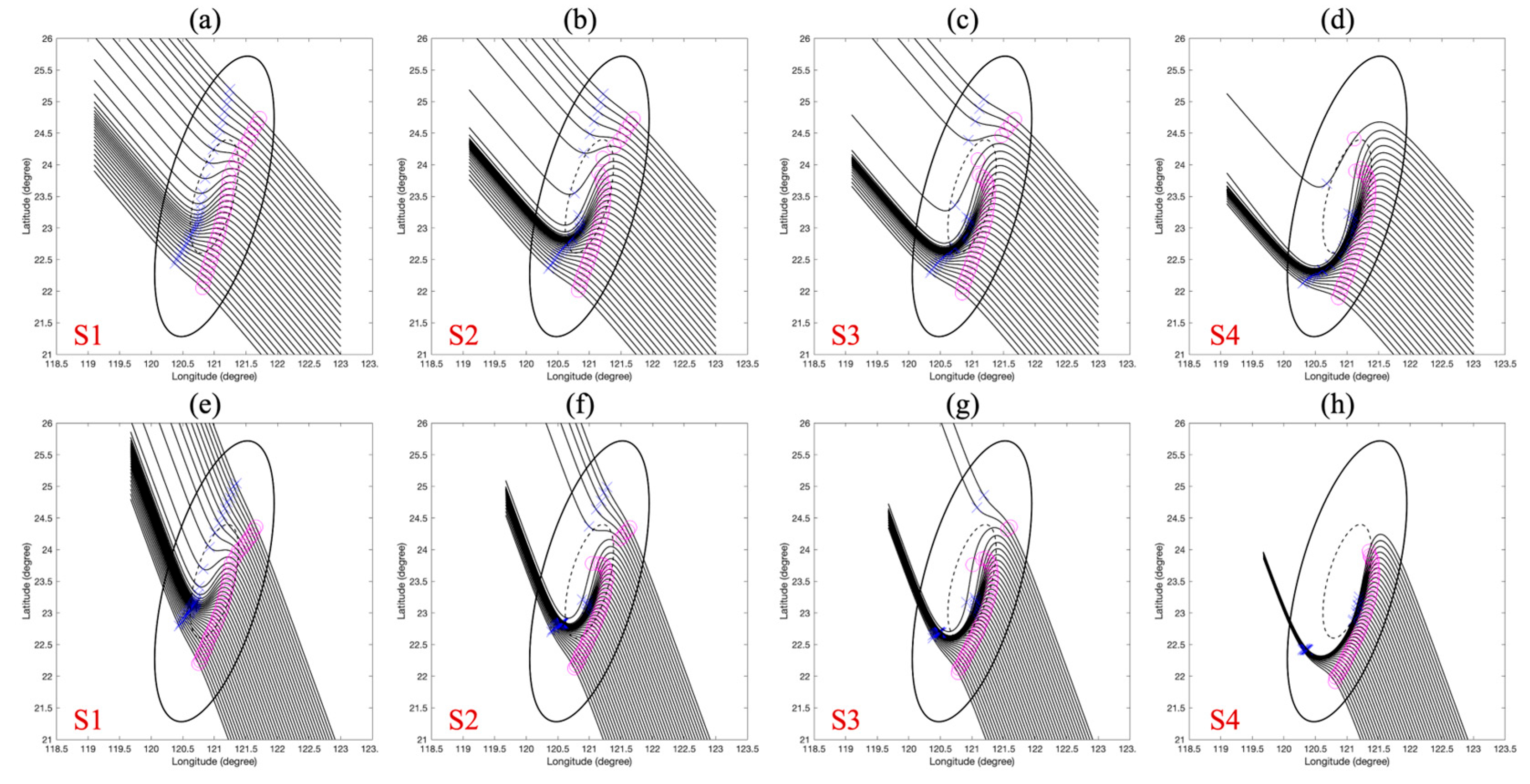

3.2. Analysis of Track Sensitivity to Vortex Intensity, Structure, and Landing Position

3.3. Extended Analysis of Track Sensitivity under Shallower Impinging Angles

3.4. Synthesis of Track Morphology Controls

3.4.1. Vortex Intensity Control (α-Modulation)

3.4.2. Terrain Geometry Control (

3.4.3. Temporal Integration Control (Residence Time Effect)

3.5. A Diagnostic Framework for Track Sensitivity: The Track Divergence Percentage

3.5.1. Track Sensitivity Zones Identification by Track Divergence Percentage

3.5.2. Control Parameters of Track Sensitivity: Impinging Angle Effects

3.6. The Kinematic Signature of Track Sensitivity: Vortex Drifting Speed

3.7. Conclusions: A Unified Framework for Track Predictability

3.7.1. Vortex Intensity Control (α-Modulation)

3.7.2. Terrain Geometry Control (

3.7.3. Temporal Integration Control (Residence Time Effect)

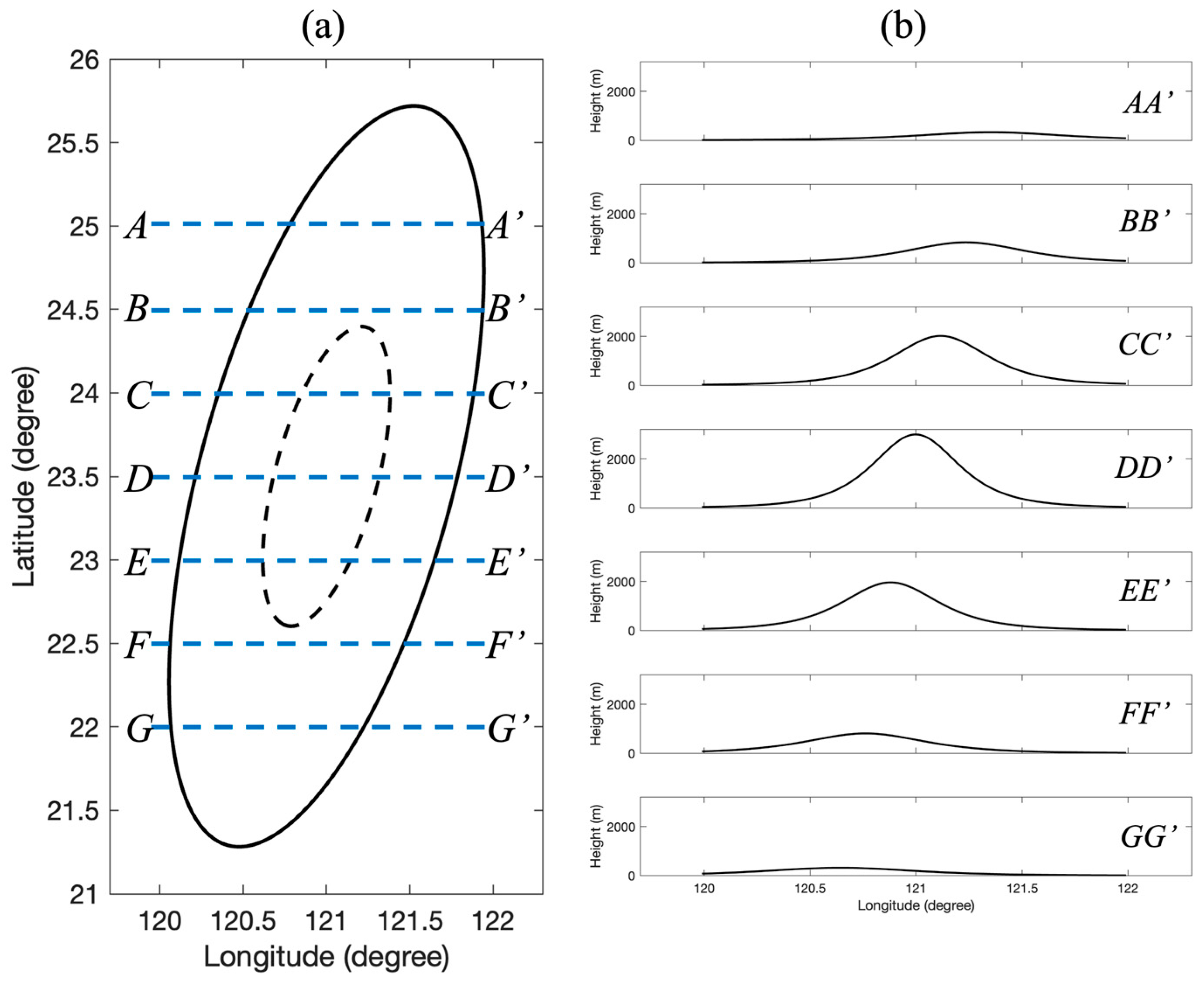

4. Application to Taiwan's Complex Topography: From Theory to Reality

4.1. Analysis of Taiwan Island Topography: Comprehensive Terrain Characteristics

4.1.1. Latitudinal Cross-Sectional Analysis

4.1.2. Longitudinal CMR Profile Analysis

4.1.3. Implications for Dynamic Model Application

4.2. Experimental Design for Dynamic Model Application to Taiwan

4.3. Track Morphology and Predictability over Taiwan: The 195° Case Study

4.4. Amplified Steering and Modulated Sensitivity: The 170° Case Study

4.5. Terrain Channeling and the Emergence of Hyper-Sensitivity: The 145° Case Study

4.6. Terrain Capture and the Breakdown of Predictability: The 125° Case Study

5. Conclusions

5.1. A Unified Framework for Topographic Steering: From Idealized Principles to Realistic Complexity

5.2. Evaluation of the Track Sensitivity Framework and Implications for Forecasting

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kepert, J.D. Tropical Cyclone Structure and Dynamics. In World Scientific Series on Asia-Pacific Weather and Climate; WORLD SCIENTIFIC, 2010; Vol. 4, pp. 3–53 ISBN 978-981-4293-47-1.

- Lin, Y.-L. Mesoscale Dynamics; 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2007; ISBN 978-0-521-00484-8.

- Chan, J.C.L.; Kepert, J.D. Global Perspectives on Tropical Cyclones: From Science to Mitigation; World Scientific Series on Asia-Pacific Weather and Climate; WORLD SCIENTIFIC, 2010; Vol. 4; ISBN 978-981-4293-47-1.

- Wu, C.-C.; Kuo, Y.-H. Typhoons Affecting Taiwan: Current Understanding and Future Challenges. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 1999, 80, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, S.L.; Wang, S.T.; Cheng, M.D.; Yeh, T.C. Tropical cyclone tracks over Taiwan and its vicinity for the one hundred years 1897 to 1996; Central Weather Bureau: Taipei, 1998; p. 497. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.T. An integrated study of the impact of the orography in Taiwan on the movement, intensity, structure, wind and rainfall distribution of invading typhoons; Chinese National Science Council: Taipei, 1992; p. 285.

- Brand, S.; Blelloch, J.W. Changes in the Characteristics of Typhoons Crossing the Island of Taiwan. Mon. Wea. Rev. 1974, 102, 708–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.-C.; Elsberry, R.L. Interaction of Typhoons with the Taiwan Orography. Part I: Upstream Track Deflections. Mon. Wea. Rev. 1993, 121, 3193–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.-C.; Elsberry, R.L. Interaction of Typhoons with the Taiwan Orography. Part II: Continuous and Discontinuous Tracks across the Island. Mon. Wea. Rev. 1993, 121, 3213–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-L.; Han, J.; Hamilton, D.W.; Huang, C.-Y. Orographic Influence on a Drifting Cyclone. J. Atmos. Sci. 1999, 56, 534–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-L.; Ensley, D.B.; Chiao, S.; Huang, C.-Y. Orographic Influences on Rainfall and Track Deflection Associated with the Passage of a Tropical Cyclone. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2002, 130, 2929–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-L.; Chen, S.-Y.; Hill, C.M.; Huang, C.-Y. Control Parameters for the Influence of a Mesoscale Mountain Range on Cyclone Track Continuity and Deflection. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 2005, 62, 1849–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.-C.; Hsiao, L.-F.; Chen, D.-S.; Huang, K.-N. A Study on Terrain-Induced Tropical Cyclone Looping in East Taiwan: Case Study of Typhoon Haitang in 2005. Nat Hazards 2012, 63, 1497–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Wang, S.-T.; Shieh, S.-L.; Cheng, M.-D.; Yeh, T.-C. Surface Track Discontinuity of Tropical Cyclones Crossing Taiwan: A Statistical Study. Monthly Weather Review 2012, 140, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D.-L. A Statistical Study of Unusual Tracks of Tropical Cyclones near Taiwan Island. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology 2018, 57, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.-C.; Wu, C.-C. The Impact of Idealized Terrain on Upstream Tropical Cyclone Track. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 2018, 75, 3887–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, G.-J.; Teng, J.-H.; Wang, S.-T.; Cheng, M.-D.; Cheng, C.-P.; Chen, J.-H.; Chu, Y.-J. An Overview of the Tropical Cyclone Database at the Central Weather Bureau of Taiwan. TAO 2022, 33, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-Y.; Chen, C.-A.; Chen, S.-H.; Nolan, D.S. On the Upstream Track Deflection of Tropical Cyclones Past a Mountain Range: Idealized Experiments. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 2016, 73, 3157–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-L.; Chen, S.-H.; Liu, L. Orographic Influence on Basic Flow and Cyclone Circulation and Their Impacts on Track Deflection of an Idealized Tropical Cyclone. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 2016, 73, 3951–3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.-H.; Su, S.-H.; Fovell, R.G.; Kuo, H.-C. On Typhoon Track Deflections near the East Coast of Taiwan. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2018, 146, 1495–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.-H.; Kuo, H.-C.; Fovell, R.G. On the Geographic Asymmetry of Typhoon Translation Speed across the Mountainous Island of Taiwan. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 2013, 70, 1006–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-C.; Li, T.-H.; Huang, Y.-H. Influence of Mesoscale Topography on Tropical Cyclone Tracks: Further Examination of the Channeling Effect. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 2015, 72, 3032–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.-J. The Orographic Effects Induced by an Island Mountain Range on Propagating Tropical Cyclones. Mon. Wea. Rev. 1982, 110, 1255–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, M.A.; Tuleya, R.E.; Kurihara, Y. A Numerical Study of the Effect of Island Terrain on Tropical Cyclones. Mon. Wea. Rev. 1987, 115, 130–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-H.; Wu, C.-C.; Wang, Y. The Influence of Island Topography on Typhoon Track Deflection. Monthly Weather Review 2011, 139, 1708–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adem, J. A Series Solution for the Barotropic Vorticity Equation and Its Application in the Study of Atmospheric Vortices. TellusA 1956, 8, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, G.F.; Kloosterziel, R.C.; Van Heijst, G.J.F. Propagation of Barotropic Vortices over Topography in a Rotating Tank. J. Fluid Mech. 1991, 233, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schär, C.; Smith, R.B. Shallow-Water Flow Past Isolated Topography. Part II: Transition to Vortex Shedding. J. Atmos. Sci. 1993, 50, 1401–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, A.; Marubayashi, K.; Ishibashi, M. A Laboratory Experiment and Numerical Simulation of an Isolated Barotropic Eddy in a Basin with Topographic β. J. Fluid Mech. 1990, 213, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, H.-C.; Williams, R.T.; Chen, J.-H.; Chen, Y.-L. Topographic Effects on Barotropic Vortex Motion: No Mean Flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 2001, 58, 1310–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.C.L. The Physics of Tropical Cyclone motion. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2005, 37, 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-C.; Leu, J.-H.; Lin, Y.-L.; Liu, H.-P.; Huang, C.-L.; Chen, H.-S.; Lan, T.-S. Cyclonic Motion and Structure in Rotating Tank: Experiment and Theoretical Analysis. Sensors and Materials 2021, 33, 2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-C. Interaction of Barotropic Vortices over Topography Based on Similarity Laws: Rotating Tank Experiment and Shallow-Water Simulation. Arab J Geosci 2022, 15, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-C. Sensitivity Analysis of Strong Cyclone Track Deflection over Isolated Topography: Exploring the Impact of Vortex Impinging Direction and Strength. In Proceedings of the ECAS 2023; MDPI, November 27 2023; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.-C. An Innovative Dynamic Model for Predicting Typhoon Track Deflections over Complex Terrain. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.B.; Smith, D.F. Pseudoinviscid wake formation by mountains in shallow-water flow with a drifting vortex. J. Atmos. Sci. 1995, 52, 436–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.K.; Chan, J.C.L. Idealized Simulations of the Effect of Taiwan and Philippines Topographies on Tropical Cyclone Tracks. Quart J Royal Meteoro Soc 2014, 140, 1578–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.K.; Chan, J.C.L. Idealized Simulations of the Effect of Taiwan Topography on the Tracks of Tropical Cyclones with Different Sizes. Quart J Royal Meteoro Soc 2016, 142, 793–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-F.; Wu, C.-C.; Yen, T.-H.; Huang, Y.-H. Typhoon Fanapi (2010) and Its Interaction with Taiwan Terrain—Evaluation of the Uncertainty in Track, Intensity and Rainfall Simulations. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 2020, 98, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-C.; Lien, G.-Y.; Chen, J.-H.; Zhang, F. Assimilation of Tropical Cyclone Track and Structure Based on the Ensemble Kalman Filter (EnKF). Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 2010, 67, 3806–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-L.; Savage, L.C. Effects of Landfall Location and the Approach Angle of a Cyclone Vortex Encountering a Mesoscale Mountain Range. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 2011, 68, 2095–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Lin, Y.-L.; Chen, S.-H. Effects of Landfall Location and Approach Angle of an Idealized Tropical Cyclone over a Long Mountain Range. Front. Earth Sci. 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, G.J. An Analytic Model of the Wind and Pressure Profiles in Hurricanes. Mon. Wea. Rev. 1980, 108, 1212–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.C.L.; Williams, R.T. Analytical and Numerical Studies of the Beta-Effect in Tropical Cyclone Motion. Part I: Zero Mean Flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 1987, 44, 1257–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wang, B. A Potential Vorticity Tendency Diagnostic Approach for Tropical Cyclone Motion. Mon. Wea. Rev. 2000, 128, 1899–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.C.L.; Ko, F.M.F.; Lei, Y.M. Relationship between Potential Vorticity Tendency and Tropical Cyclone Motion. J. Atmos. Sci. 2002, 59, 1317–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedlosky, J. Geophysical Fluid Dynamics; Springer New York: New York, NY, 1987; ISBN 978-0-387-96387-7. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, J.C.L. Physical Mechanisms Responsible for Track Changes and Rainfall Distributions Associated with Tropical Cyclone Landfall. In Oxford Handbook Topics in Physical Sciences; Oxford Handbooks Editorial Board, Ed.; Oxford University Press, 2017 ISBN 978-0-19-069942-0.

- Chen, H.-C.; Leu, J.-H.; Liu, Y.; Xie, H.-S.; Chen, Q. A Validated Study of a Modified Shallow Water Model for Strong Cyclonic Motions and Their Structures in a Rotating Tank. Mathematical Problems in Engineering 2021, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).