1. Introduction

Per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a diverse group of chemical compounds known as “forever chemicals.” These chemicals are used in microchips, jet engines, cars, batteries, medical devices, refrigeration systems, and many more everyday items. Their chemical makeup makes them ideal compounds for protection against heat, corrosion, water damage, and more, but the prominence of carbon-fluorine bonds imparts a bond strength that is not broken apart by natural processes, allowing them to exist indefinitely in our environment [

1,

2,

3].

Current environmental protection agency efforts note that there exist over 12,000 different PFAS compounds present in the environment, indicating that PFAS has extensively permeated our daily lives [

4]. With a multitude of different structures and properties, PFAS compounds likely act in combination with one another, as well as with other environmental contaminants. Multiple studies have started to explore chemical combinations through various toxicology assays and mixture-specific gene expression in zebrafish [

5,

6,

7,

8], but there remains a large gap in understanding the effects of combinatorial chemical exposures. With PFAS chemicals heavily suspected to be carcinogens, their ubiquitous presence in our environment leads to concerning questions about the impact on our health [

9,

10]. Alarmingly, with the buildup of PFAS in our environment, nearly every person today has registered PFAS levels in their blood, suggesting signs of significant bioaccumulation [

9,

10,

11]. From an extensive review of published literature, Steenland and Winquist found that there is an association between PFAS and cancer, particularly testicular and kidney cancers [

10].

One PFAS compound of concern is perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS). With a long estimated half-life of 3.4 years [

12], the average global levels of PFOS in blood samples are 20-30 ng/mL [

13]. Compelling evidence suggests that PFOS affects the urogenital system and promotes kidney cancer. Epigenetic, transcription factor, and kidney biomarker signatures, serum analyses, and epidemiologic studies link PFOS exposure to chronic kidney disease and cancer [

14,

15,

16].

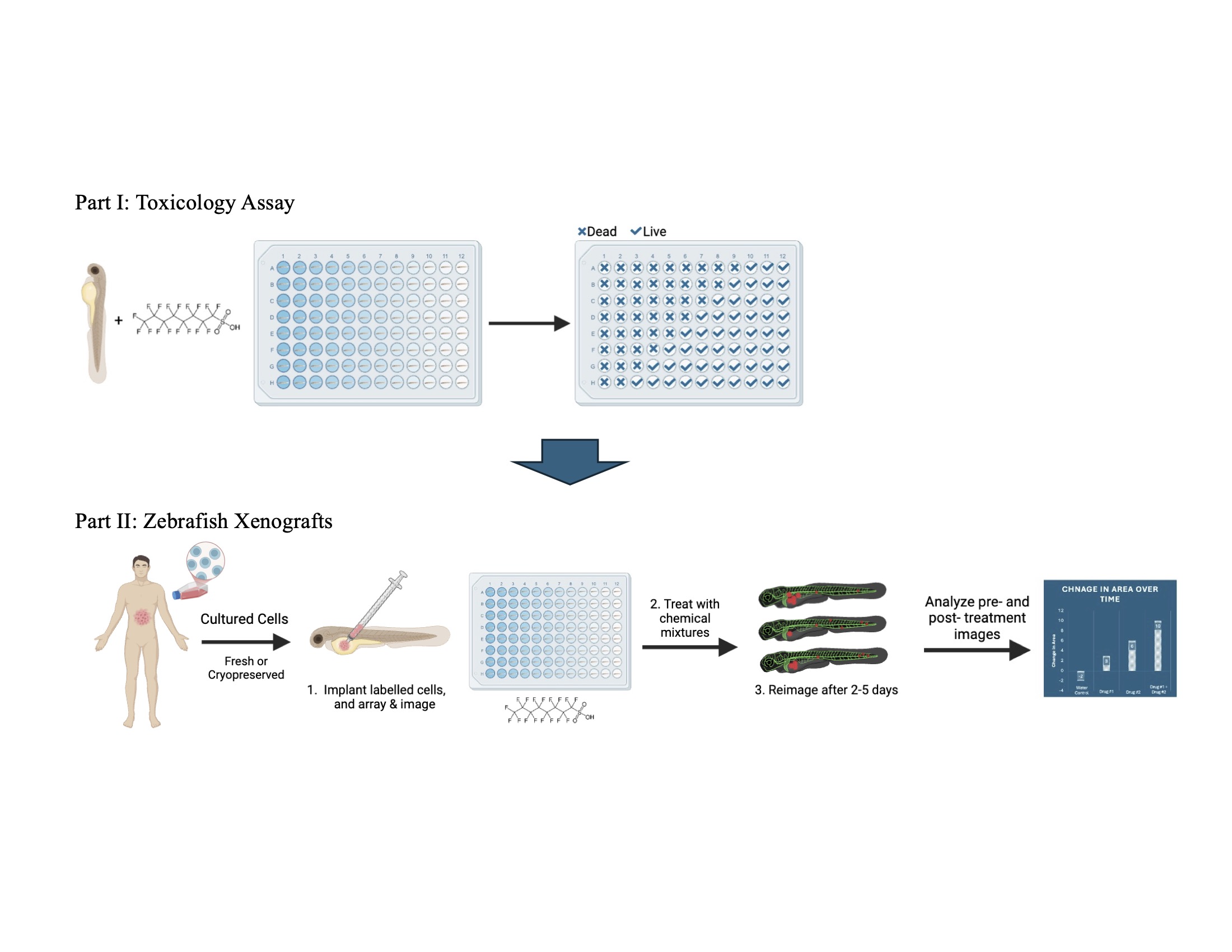

Here, we aim to develop a complementary approach for screening chemicals for potential carcinogenic properties, utilizing zebrafish xenograft assays. Zebrafish xenograft models have been extensively utilized for investigating cancer biology, developing and validating anti-cancer drugs, and as clinical diagnostics for guiding personalized cancer therapeutics [

17,

18].

Xenograft methods involve injecting human cells into a targeted region of the developing zebrafish embryo, placing the embryo in the compound of interest, and observing the tumor throughout the duration of chemical exposure. Zebrafish are an ideal model for translatable biomedical research, compared to other vertebrate models, because they have a fully sequenced genome, share over 70% of their genome with humans, and consist of transparent embryos which makes for easy observation of development [

19]. Our xenograft assay merits designation as a New Approach Methodology (NAM) as it is an animal xenograft that satisfies the desirable traits of human 3D culture while also allowing for systems analyses that are only possible in an animal model [

20].

Our approach, using PFOS as a test compound, was to systematically evaluate PFOS toxicity at the exposure times and temperature expected to be used for the xenograft assays. Using these toxicity values, we then predicted appropriate PFOS concentrations for carcinogenicity testing in our xenograft assays. Our first step was to do a range-finding toxicity assay followed by testing a refined concentration curve. To limit variability and minimize effort, we scored for viability at 24 hr post-treatment. From these experiments, we determined the Lethal Concentration 50 (LC50), defined as the median concentration resulting in 50% mortality and the Maximum Tolerated Concentration (MTC), defined as the highest concentration that reliably results in 100% survival [

21,

22]. Zebrafish xenografts were then exposed to PFOS concentrations of 5%, 10% and 20% of the MTC.

Because PFOS exposure is linked to chronic kidney disease and cancer, we tested two well-studied kidney cancer cell lines. A renal cell carcinoma line, ACHN, was chosen as they are known to proliferate in zebrafish xenografts, and a clear cell renal cell carcinoma line, Caki-1, was chosen as a model for this most common form of kidney cancer [

23].

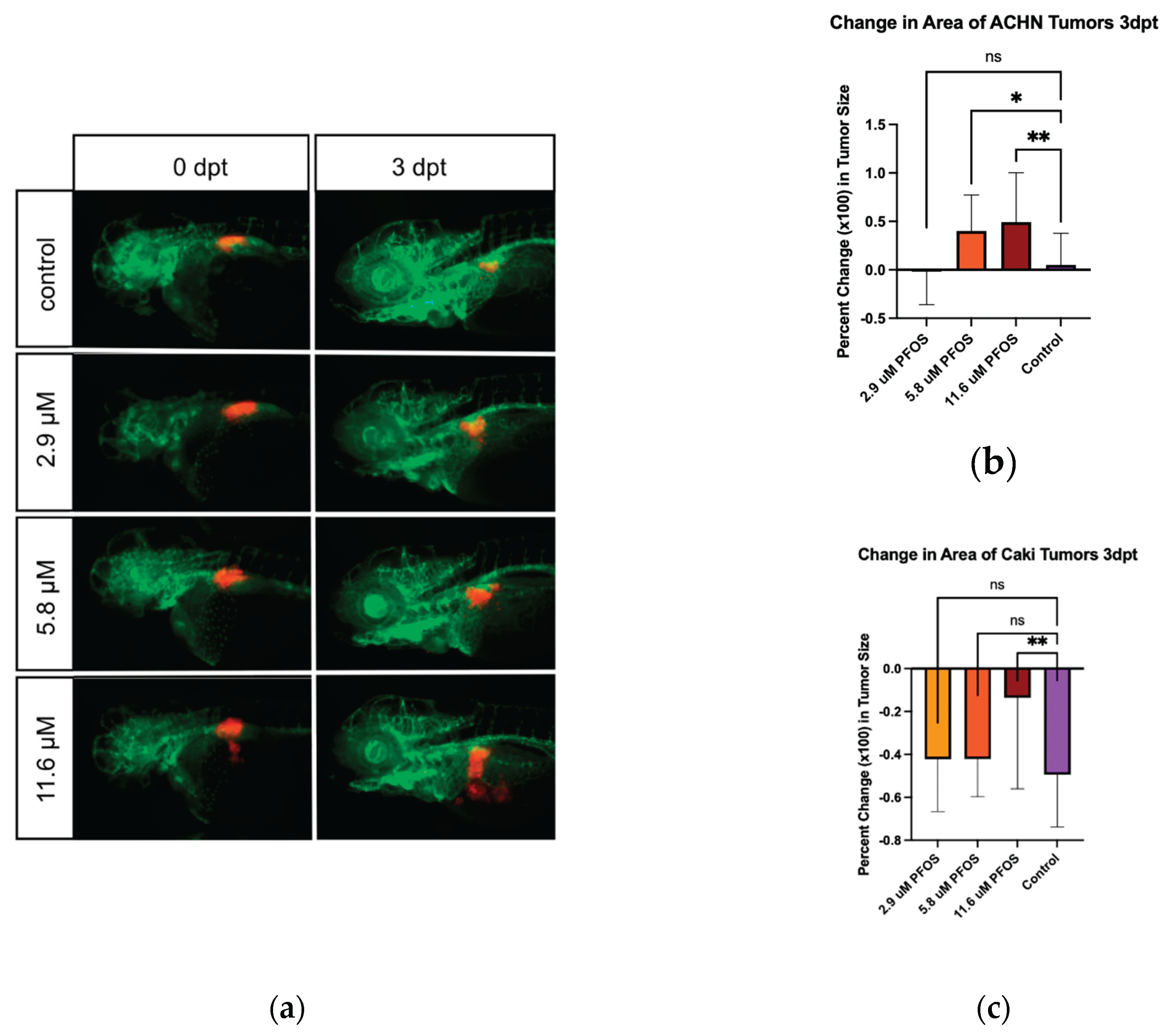

For our xenografts, we injected DiI-labeled ACHN or stably GFP expressing Caki-1 cancer cells into 2 dpf embryos near the developing kidney. The embryos were imaged following injection, and then treated with PFOS. After 3 days incubation at 33°C, the larvae were imaged a second time. Tumor size was determined using image analysis. When treated with PFOS, these kidney cancer cells show dose-dependent increases in tumor area compared to controls.

This study is the first to directly show cancer promoting activity of PFOS, using a rapid in vivo zebrafish xenograft assay. Considering the popularity of zebrafish as toxicology models and the prevalence of zebrafish xenograft assays for cancer studies, it is somewhat surprising that these models are not commonly utilized for carcinogenesis screening of chemical compounds. Our results demonstrate the utility of zebrafish xenograft assays for validation of predicted cancer promoting properties of environmental contaminants, such as PFAS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Zebrafish

Zebrafish husbandry, breeding, and injections were performed by the Georgetown-Lombardi Animal Shared Resource. Zebrafish studies were conducted in accordance with NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the Georgetown University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Protocol # 2017-0078.

Eggs were obtained with natural pairwise or group crosses in breeding chambers. The embryos were collected in the morning and transferred to fish water (.3 g/L sea salt, Instant Ocean, Blacksburg, VA) containing 200 μM phenylthiourea (PTU, Sigma-Aldrich) to inhibit pigment formation. The age of the embryos was determined using morphological staging criteria [

24]. At 1 day post fertilization (dpf), embryos were chemically dechorionated using 200 μg/mL pronase (CalBioChem, Sigma-Aldrich).

2.2. Toxicology Assays

Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (CAS# 1763-23-1). 200 mM PFOS stock solution in DMSO was made fresh on the day of the experiment, and then diluted to 2x final concentration in fish water containing PTU.

Dechorionated zebrafish embryos were arrayed into 96-well plates in 100 μL fish water containing PTU at 1dpf. At 2dpf, 100 μL of 2x PFOS solution was added and plates were incubated at 33°C for 24 hrs.

Embryo survival was assessed at 24 hours post-treatment. If the embryo had physically deteriorated and/or there was no heartbeat, the embryo was assigned a 0 value to denote death. If the embryo showed any movement and/or a discernible heartbeat, the embryo was assigned a 1 value to denote survival. Range finding experiments used 4 or 8 embryos per group, with two repeats performed on different days and with different breeding groups. Refined concentration experiments used a minimum of 8 embryos per group, with three independent repeats. Analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism Software (version 10). The number of embryos scoring as 0s and 1s were averaged for each experimental group. A “Sigmoidal, 4PL, X is concentration” plot was generated using the nonlinear fit analysis function, and graphical visualizations were created. From this fit, LC50s were calculated. MTCs were calculated from the nonlinear fit by taking 75% of the concentration where 90% percent survival would be reached.

2.3. Cell Culture

ACHN (CRL-1611) cell cultures were obtained from the Georgetown University Tissue Culture Shared Resource. ACHN cells were labeled with 5 μM Vibrant DiI cell-labeling solution (Invitrogen, Eugene Oregon, V22885) at 1x106 cells/mL, incubated 5 minutes at 37°C, and then 15 minutes on ice. Labeled cells were washed twice with PBS, once in 0.5 mM EDTA in PBS, and then resuspended in 10 μL 0.5 mM EDTA in PBS for loading the injection needle. Stably GFP-expressing Caki-1 (HTB-46) cells were purchased from Innoprot and cultured according to the manufacturer's protocol.

2.4. Zebrafish Xenografts

Zebrafish transgenic

Tg(kdrl:grcfp)zn1 or

Tg(mpeg1:mCherry)gl23 embryos at 2 dpf were anesthetized with 0.016% tricaine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in fish water (0.3g/L Sea Salt, Instant Ocean, Blacksburg, VA), loaded on to an agarose injection plate, and were injected with 100-200 cells into the body above the yolk sack just posterior to the pectoral fin, using an air driven Picospritzer II microinjector (General Valve Corp, Fairfield, NJ) under a Leica M165 stereoscope. Following injection, embryos were examined for proper injection size, location, and absence of cells in the tail. Correctly injected embryos were imaged on a Leica M165 stereomicroscope with a K5 CMOS camera, and arrayed into 96-well plates, one embryo per well in 100 μL PTU fish water. 100 μL of 2x PFOS solution at an appropriate concentration was added to the well for a final volume of 200 μL per embryo. The embryos were incubated at 33°C for three days and then re-imaged. The area of labeled cells was measured from the day 0 and day 3 images of each embryo using ImageJ [

25]. Graphs were made using GraphPad Prism (version 10) Software.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test with multiple comparisons of means was used as the primary statistical analysis for the xenograft experiments. Statistical analyses were performed with a confidence level of 95% (α = 0.05), assuming a normal Gaussian distribution. Multiple comparisons were performed using Dunnett’s test.

3. Results

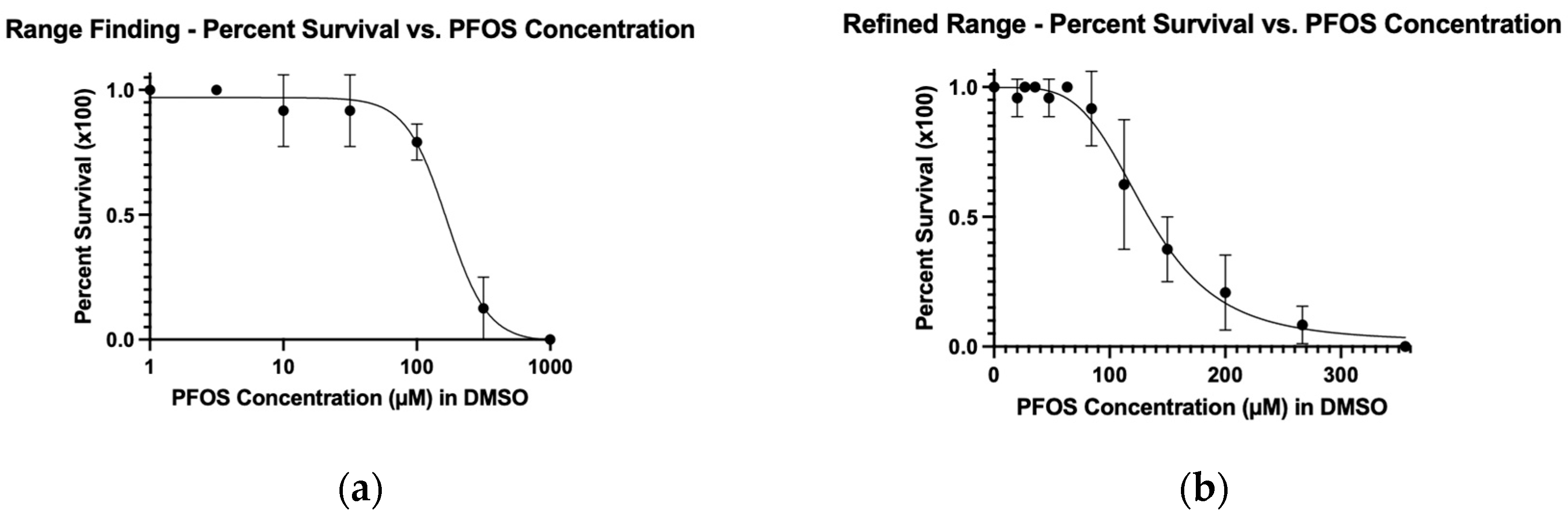

To determine the optimal dose for treating zebrafish xenografts with PFOS, we investigated acute dose-response toxicology under conditions that should be used for the xenograft assays. Initially, we performed a range-finding assay to determine the interval where the compound became lethal to the embryos. We then used that interval to inform our refined range experiment. We chose one day of treatment to mitigate variability in our results.

Figure 1.

The (a) range finding and (b) refined-range dose-response curves used to obtain LC50 and MTC data for PFOS. Embryos were treated at 2 dpf for 24 hours at 33°C and then assessed.

Figure 1.

The (a) range finding and (b) refined-range dose-response curves used to obtain LC50 and MTC data for PFOS. Embryos were treated at 2 dpf for 24 hours at 33°C and then assessed.

To determine the LC50, we used a nonlinear fit for both the range finding and refined range experiments. The LC50 from the range-finding assay was 167 μM, while the refined LC50 was 132 μM (

Table 1). The LC50 values were calculated for the range finding and refined experiments to evaluate how closely the values from these two experiments matched. While not wildly different, in our view, these values are different enough to warrant performing a refined range experiment in order to calculate appropriate concentrations for xenograft assays.

Although our conditions, 24 hr treatment at 2 dpf, incubated at 33°C, are different from those reported in the literature, our LC50 of 132 μM is within the range of consensus values (

Supplementary Table S1). This was somewhat surprising given that most assays begin treatment within hours of fertilization.

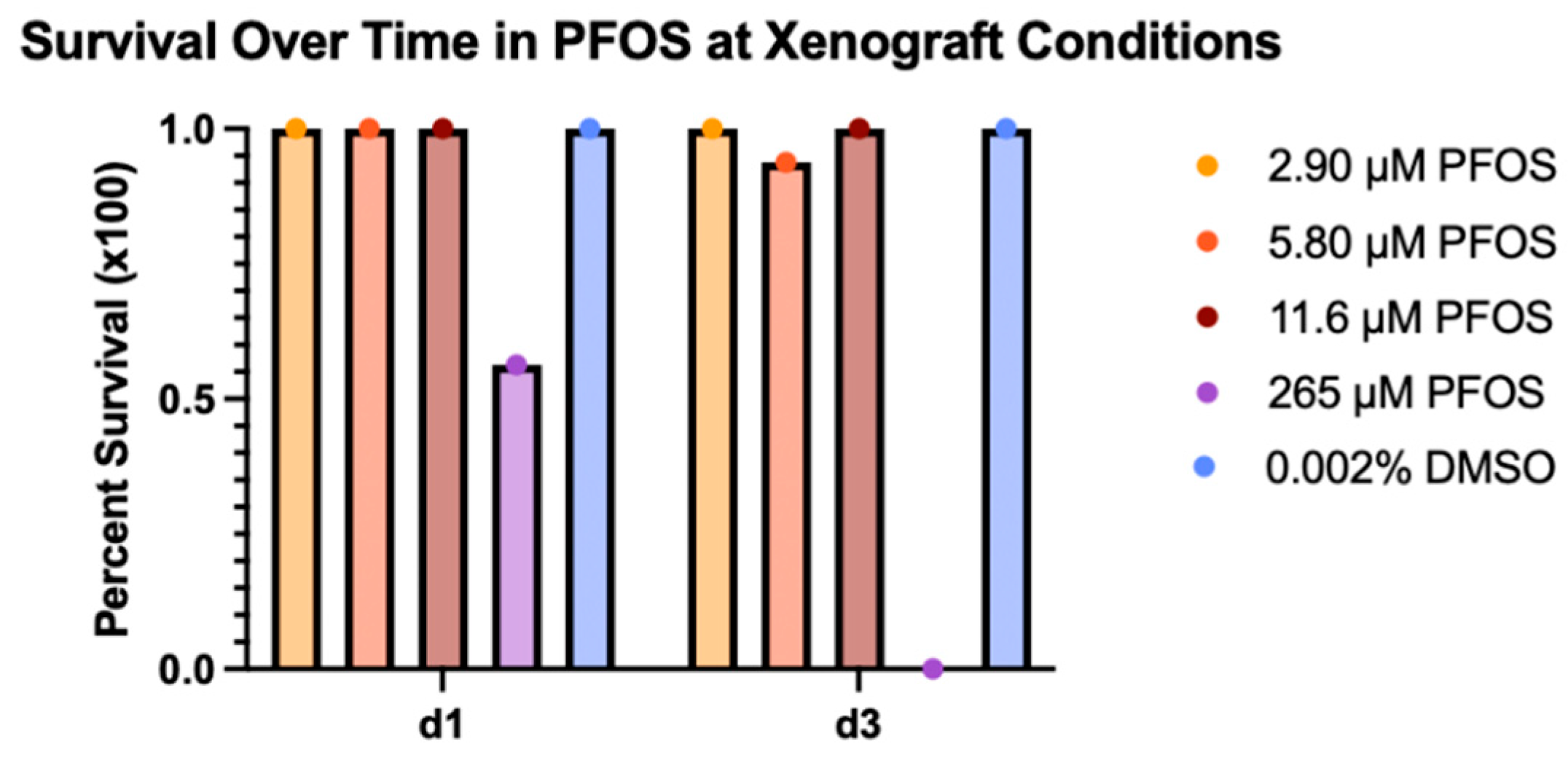

Once we determined the PFOS LC50 value, we established the corresponding MTC. We defined the MTC as 75% of the concentration that resulted in 90% survival. These calculations resulted in an MTC of 58 μM PFOS for the refined range experiment. Treatment concentrations based on 5, 10, and 20% of the PFOS MTC were chosen for the xenograft experiments (

Table 1). These concentrations were experimentally tested under xenograft conditions to confirm embryo survival of greater than 90% for 3 days of treatment (

Figure 2).

3.2. Xenograft Experiments

After confirming greater than 90% survival of each treatment group with 2.9, 5.8, and 11.6 µM PFOS, these concentrations were chosen for the xenograft assays. Zebrafish xenografts assays were used to determine acute carcinogenicity of PFOS for kidney cancer. ACHN cells were labelled with DiI and injected in the area of the developing kidney. The tumors were imaged on the day of injection (d0) and treated with PFOS. They were then re-imaged on day 3 post-injection.

Representative images of ACHN cell xenografts at 0 and 3 days post-treatment/injection are shown in

Figure 3a. Tumor areas measured using ImageJ were used to calculate percent change in tumor size. The percent change for the embryos of each treatment group was averaged and plotted as percent change in tumor size. The figure shows a dose-dependent acceleration of tumor growth in ACHN cells.

Caki-1 cells expressing GFP were injected in the area of the developing kidney. The tumors were imaged on the day of injection (d0) and treated with PFOS. They were then imaged on day 3 post-injection and treatment (Supplemental

Figure S1).

Tumor areas were measured using ImageJ and used to calculate percent change in tumor size. The percent change for the embryos of each treatment group was averaged and plotted as percent change in tumor size. The figure shows a dose-dependent protective effect for tumor growth in Caki-1 cells.

4. Discussion

There are multiple studies in zebrafish looking at the toxicology of PFOS, examining a wide range of effects such as survival, morphology, and behavior. PFOS and cancer have also been studied utilizing various techniques such as proteomics, cell culture, organoid studies, and more. We aimed to establish a protocol for testing environmental contaminants for cancer-promoting activity using zebrafish xenograft assays.

Given the large number of potential carcinogens present as environmental contaminants and their likely combinatorial action, we endeavored to develop an efficient approach for investigating the in vivo carcinogenic potential of chemical compounds that could be scaled for moderate throughput analyses. Our first step was to perform range-finding, concentration-dependent toxicology assays to identify tolerable toxin concentrations under conditions used for xenograft assays. We then used those results to refine the concentration range to more accurately determine LC50 and MTC values.

We calculated an LC50 of 167 μM from the range-finding assay and a refined LC50 of 132 μM after 24hr treatment at 33C, starting at 2dpf. Our refined value is a 0.8 factor of our range-finding value. LC50 values for similar acute toxicity assays reported in the literature lie in a consensus range from 102 to 136 uM at 72 hpf (see Supplemental

Table S1). These experiments generally start treatment soon after fertilization, use PFOS potassium salt or PFOS as a compound, and variably make stocks in DMSO or water. Variable LC50s may additionally be due to too wide a range of test concentrations, differences in solvents, low number of test subjects, differences in assessment timepoints, incubation temperature, and different compound formulations. Overall, though, compared to previous studies, the refined LC50 value obtained in this study falls within the expected range.

We chose to measure toxicology based on embryo survival because this is the fastest and most unambiguous method. Various other assays have measured PFOS toxicity in zebrafish utilizing more sensitive assays such as behavioral [

26,

27], gene expression signatures [

28,

29,

30], and developmental morphology [

31,

32,

33] (Supplemental

Table S1). Our toxicology experiments were assessed at 24 hours of treatment versus the 3 day mark used for our xenografts. The reasoning for this decision was based on our objective to establish an efficient process for evaluating environmental contaminants. The 24-hour treatment assessment period reduces variability and is faster despite requiring that the test concentrations be experimentally confirmed for the xenograft assays (see

Figure 2).

Background PFAS contamination from labware and a laboratory fish diet is a concern, particularly for evaluating LC50 and EC50 measurements among different laboratories [

34,

35]. However, these factors are unlikely to influence the results of the xenograft studies since those experiments utilize experimental vs control groups which are exposed to identical PFAS background levels.

While zebrafish are commonly utilized for toxicology studies, zebrafish xenograft assays to screen for carcinogenic activity of environmental toxins have not been utilized. Zebrafish xenograft assays are commonly used for evaluating cancer cell biology, chemosensitivity, radiosensitivity, angiogenesis, and immune cell - tumor interactions [

17,

18]. Zebrafish xenografts implanted with patient biopsies are being developed to test patient tumor specific chemosensitivity and immunotherapies. Importantly, several recent papers have demonstrated high predictive value of these xenograft assays for patient response to therapy [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. Given the demonstrated high predictive value of zebrafish xenografts for human tumor progression, our objective was to test if this assay could also identify potential carcinogenic environmental contaminants, using PFOS as a test case compound.

We focused our effort on kidney cancer because there is mounting evidence of an association of PFAS with cancer, particularly with testicular and kidney cancer [

10]. Additionally, the NIH Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics (DCEG) has used banked serum specimens to connect PFAS presence to kidney cancer development [

15]. Wen et al. saw in collected mouse kidney samples increased kidney injury markers Acta2 and Bcl2l1, upregulated transcription factors - Nef2l2, Hes1, Ppara, and Ppard - downregulated transcription factors - Smarca2 and Pparg - decreased global DNA methylation, and histone demethylase gene upregulation. In addition, they saw dose-dependent accumulation of PFOS in the mouse kidney [

14].

Our xenograft protocol utilized two kidney cancer cell lines. Xenografts with ACHN cells showed significant tumor growth when treated with PFOS. With Caki-1 cells, the xenograft assay showed a PFOS dependent protection from the decreased tumor size that was observed in the control group. Both visually viewing the zebrafish models and image analysis support the idea that while PFOS typically presents as toxic to cells, some characteristic of the compound is stimulating or protecting tumor growth. While this xenograft protocol uses acute exposure over a short time period, which is unlikely to reflect typical exposure conditions in humans, it does demonstrate that PFOS exposure can promote cancerous cell behavior. On average about 20-30ng/mL or 0.040-0.060 μM PFOS is detected in the human bloodstream. While only a twentieth of the maximum concentration used for our xenograft assay, the connection between the cancer-promoting abilities of PFOS and levels of PFOS identified in human blood is concerning. Bioaccumulation in the kidney could result in concentrations greater than those measured in blood. It should also be noted that our study focused solely on acute exposure. The results obtained in this study cannot be directly compared to chronic studies. However, our observation of the cancer-promoting properties of PFOS under these conditions propound concern with chronic exposures. Importantly, while the present studies do not investigate specific mechanisms for PFOS dependent cancer growth, our xenograft protocol provides a platform in which mechanistic investigation can be efficiently pursued.

The conclusions from our xenograft studies are supported by several in vitro studies. Cell proliferation, flow cytometry, immunocytochemistry, cell migration, and invasion assays demonstrate the potential tumorigenic activity of PFOS [

42]. In three-dimensional colorectal cancer spheroids treated with PFOS, molecular analysis showed downregulation of E-cadherin and upregulation of N-cadherin and vimentin [

43]. In contrast to spheroid cultures, a powerful aspect of our

in vivo zebrafish xenograft assay is that it encompasses the entire animal environment, integrating effects on cancer cells, the cancer microenvironment, innate immune cells, compound distribution and metabolism. Importantly, PFAS molecules induce comparable transcriptional changes and affect the same metabolic processes across inter-species borders [

44]. In mice, PFOS treatment resulted in an accumulation of the compound in the kidney, increased kidney injury markers, and global DNA hypomethylation, all of which support of a potentially cancerous effect of the compound [

14].

5. Conclusions

Overall, this study provides a new

in vivo model to efficiently identify potential carcinogenic properties of environmental contaminants, and specifically supports the proposal that PFOS promotes urogenital cancer. These results bolster the potential classification of PFOS as a carcinogen. With a pressing need to study the carcinogenic potential of environmental contaminants, zebrafish xenografts emerge as an extremely effective tool for analysis. This study focused on tumor growth of two cell lines resulting from exposure to one PFAS compound, further research can expand upon these findings by replicating them with cell lines from multiple different cancer types. Our zebrafish xenograft protocol is especially applicable for screening chemical combinations. There exist over 12 thousand toxic PFAS compounds whose mixtures, and their subsequent unknown effects, are endless. Computationalists have already begun developing models to identify such mixtures of concern [

45,

46]. Our xenograft protocol is ideally suited as an efficient method to validate computationally predicted mixtures and identify carcinogenic potential of environmental contaminants.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. Supplemental Figure S1 includes representative images of Caki-1 xenografts. Supplemental Table S1 summarizes literature concerning PFOS and zebrafish.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.B. and E.G.; methodology, T.B., J.R.D., L.S. and M.A.; validation, T.B., J.R.D., L.S. and E.G.; formal analysis, T.B.; investigation, T.B., L.S. and J.R.D.; resources, E.G.; data curation, T.B.; writing—original draft preparation, T.B., J.D.R. and E.G.; writing—review and editing, E.G.; visualization, T.B. and E.G.; supervision, E.G.; project administration, T.B. and E.G.; funding acquisition, E.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Zebrafish Shared Resource and the Tissue Culture Shared Resource are partially supported by NIH/NCI CCSG grant P30-CA051008.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Zebrafish studies were conducted in accordance with NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the Georgetown University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Protocol # 2017-0078. Date 8 March 2017.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The Zebrafish Shared Resource and the Tissue Culture Shared Resource are partially supported by NIH/NCI CCSG grant P30-CA051008. Thank you to the Center for PFAS and Cancer, Dr. Myakala from Dr. Levi’s Lab for providing the PFOS, and Dr. Brelidze’s Lab.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PFOS |

Perfluorooctanesulfonic Acid |

| PFAS |

Per- and Poly-fluoroalkyl substances |

| LC50 |

Lethal Concetration causing 50% death |

| MTC |

Maximum Tolerated Concentration |

| ACHN |

Renal cell carcinoma |

| Caki-1 |

Clear renal cell carcinoma cells |

| NAM |

New Approach Methodology |

| hpf |

Hours post fertilization |

| dpf |

Days post fertilization |

| dpt |

Days post treatment |

| PTU |

Phenylthiourea |

| ANOVA |

One-way analysis of variance |

References

- Zeng, Z.; Song, B.; Xiao, R.; Zeng, G.; Gong, J.; Chen, M.; Xu, P.; Zhang, P.; Shen, M.; Yi, H. Assessing the Human Health Risks of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate by in Vivo and in Vitro Studies. Environ Int 2019, 126, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, R.C.; Franklin, J.; Berger, U.; Conder, J.M.; Cousins, I.T.; de Voogt, P.; Jensen, A.A.; Kannan, K.; Mabury, S.A.; van Leeuwen, S.P. Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in the Environment: Terminology, Classification, and Origins. Integr Environ Assess Manag 2011, 7, 513–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, A.G.; Jones, K.C.; Sweetman, A.J. A First Global Production, Emission, and Environmental Inventory for Perfluorooctane Sulfonate. Environ Sci Technol 2009, 43, 386–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.J.; Gaines, L.G.T.; Grulke, C.M.; Lowe, C.N.; Sinclair, G.F.B.; Samano, V.; Thillainadarajah, I.; Meyer, B.; Patlewicz, G.; Richard, A.M. Assembly and Curation of Lists of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (Pfas) to Support Environmental Science Research. Front Environ Sci 2022, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, M.; Karrman, A.; Kukucka, P.; Scherbak, N.; Keiter, S. Mixture-Specific Gene Expression in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Embryos Exposed to Perfluorooctane Sulfonic Acid (Pfos), Perfluorohexanoic Acid (Pfhxa) and 3,3',4,4',5-Pentachlorobiphenyl (Pcb126). Sci Total Environ 2017, 590-591, 249-57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, M.; Xiong, D.; Sun, Y. Combined Effects of Pfos and Pfoa on Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Embryos. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 2013, 64, 668–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fey, M. E., P. E. Goodrum, N. R. Razavi, C. M. Whipps, S. Fernando, and J. K. Anderson. Is Mixtures' Additivity Supported by Empirical Data? A Case Study of Developmental Toxicity of Pfos and 6:2 Fts in Wildtype Zebrafish Embryos. Toxics 10, no. 8 (2022).

- Khezri, A., T. W. Fraser, R. Nourizadeh-Lillabadi, J. H. Kamstra, V. Berg, K. E. Zimmer, and E. Ropstad. A Mixture of Persistent Organic Pollutants and Perfluorooctanesulfonic Acid Induces Similar Behavioural Responses, but Different Gene Expression Profiles in Zebrafish Larvae. Int J Mol Sci 18, no. 2 (2017).

- Arrieta-Cortes, R.; Farias, P.; Hoyo-Vadillo, C.; Kleiche-Dray, M. Carcinogenic Risk of Emerging Persistent Organic Pollutant Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (Pfos): A Proposal of Classification. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2017, 83, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steenland, K.; Winquist, A. Pfas and Cancer, a Scoping Review of the Epidemiologic Evidence. Environ Res 2021, 194, 110690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingley, K. Forever Chemicals Are Everywhere. What Are They Doing to Us? New York Times, August 16, 2023 2023.

- Li, Y.; Fletcher, T.; Mucs, D.; Scott, K.; Lindh, C.H.; Tallving, P.; Jakobsson, K. Half-Lives of Pfos, Pfhxs and Pfoa after End of Exposure to Contaminated Drinking Water. Occup Environ Med 2018, 75, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S.; Cao, Y.; Chen, R.; Bedi, M.; Sanders, A.P.; Ducatman, A.; Ng, C. A State-of-the-Science Review of Interactions of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (Pfas) with Renal Transporters in Health and Disease: Implications for Population Variability in Pfas Toxicokinetics. Environ Health Perspect 2023, 131, 76002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Rashid, F.; Fazal, Z.; Singh, R.; Spinella, M.J.; Irudayaraj, J. Nephrotoxicity of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (Pfos)-Effect on Transcription and Epigenetic Factors. Environ Epigenet 2022, 8, dvac010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durham, J.; Tessmann, J.W.; Deng, P.; Hennig, B.; Zaytseva, Y.Y. The Role of Perfluorooctane Sulfonic Acid (Pfos) Exposure in Inflammation of Intestinal Tissues and Intestinal Carcinogenesis. Front Toxicol 2023, 5, 1244457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.; Tan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ma, L.; Hou, X.; Wang, W.; Sun, R.; Yin, L.; Pu, Y.; Zhang, J. Linking Pfos Exposure to Chronic Kidney Disease: A Multimodal Study Integrating Epidemiology, Network Toxicology, and Experimental Validation. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2025, 302, 118770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Glasgow, E.; Agarwal, S. Zebrafish Xenografts for Drug Discovery and Personalized Medicine. Trends Cancer 2020, 6, 569–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-López, M.F.; López-Gil, J.F. Small Fish, Big Answers: Zebrafish and the Molecular Drivers of Metastasis. Int J Mol Sci 26, no. 3 (2025).

- Siddiqui, S., H. Siddiqui, E. Riguene, and M. Nomikos. Zebrafish: A Versatile and Powerful Model for Biomedical Research. Bioessays (2025): e70080.

- Subcommittee, New Alternative Methods. Potential Approaches to Drive Future Integration of New Alternative Methods for Regulatory Decision-Making: A Report to the Science Board to the Food and Drug Administration from the New Alternative Methods Subcommittee. Food and Drug Administration, 2024.

- Morris-Schaffer, Keith, and Michael J. McCoy. A Review of the Ld50 and Its Current Role in Hazard Communication. ACS Chemical Health & Safety 2021, 28, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson, T.H.; Bögi, C.; Winter, M.J.; Owens, J.W. Benefits of the Maximum Tolerated Dose (Mtd) and Maximum Tolerated Concentration (Mtc) Concept in Aquatic Toxicology. Aquat Toxicol 2009, 91, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaidi, I., H. Cassidy, V. I. Gaspar, J. McCaul, M. Higgins, M. Halász, A. L. Reynolds, B. N. Kennedy, and T. McMorrow. Curcumin Sensitizes Kidney Cancer Cells to Trail-Induced Apoptosis Via Ros Mediated Activation of Jnk-Chop Pathway and Upregulation of Dr4. Biology (Basel) 9, no. 5 (2020).

- Kimmel, C.B.; Ballard, W.W.; Kimmel, S.R.; Ullmann, B.; Schilling, T.F. Stages of Embryonic-Development of the Zebrafish. Developmental Dynamics 1995, 203, 253–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindelin, Johannes, Ignacio Arganda-Carreras, Erwin Frise, Verena Kaynig, Mark Longair, Tobias Pietzsch, Stephan Preibisch, Curtis Rueden, Stephan Saalfeld, Benjamin Schmid, Jean-Yves Tinevez, Daniel James White, Volker Hartenstein, Kevin Eliceiri, Pavel Tomancak, and Albert Cardona. Fiji: An Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 676–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menger, F.; Pohl, J.; Ahrens, L.; Carlsson, G.; Orn, S. Behavioural Effects and Bioconcentration of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (Pfass) in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Embryos. Chemosphere 2020, 245, 125573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagenaars, A.; Vergauwen, L.; De Coen, W.; Knapen, D. Structure-Activity Relationship Assessment of Four Perfluorinated Chemicals Using a Prolonged Zebrafish Early Life Stage Test. Chemosphere 2011, 82, 764–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Yeung, L.W.; Lam, P.K.; Wu, R.S.; Zhou, B. Protein Profiles in Zebrafish (Danio Rerio) Embryos Exposed to Perfluorooctane Sulfonate. Toxicol Sci 2009, 110, 334–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhou, B. The Role of Nrf2 and Mapk Pathways in Pfos-Induced Oxidative Stress in Zebrafish Embryos. Toxicol Sci 2010, 115, 391–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jantzen, C.E.; Annunziato, K.A.; Bugel, S.M.; Cooper, K.R. Pfos, Pfna, and Pfoa Sub-Lethal Exposure to Embryonic Zebrafish Have Different Toxicity Profiles in Terms of Morphometrics, Behavior and Gene Expression. Aquat Toxicol 2016, 175, 160–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Dan, Xiaohui Li, Shasha Dong, Xiaohui Zhao, Xiaoying Li, Meng Zhang, Yawei Shi, and Guanghui Ding. Developmental Toxicity and Cardiotoxicity Induced by Pfos and Its Novel Alternative Obs in Early Life Stage of Zebrafish (Danio Rerio). Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 2023, 234, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Guang Hui, Jing Zhang, Yi Hong Chen, Guo Yi Luo, and Chao Hong Mao. Acute Toxicity Effect of Pfos on Zebrafish Embryo. Advanced Materials Research 2011, 356-360, 603-06.

- Zheng, Xin-Mei, Hong-Ling Liu, Wei Shi, Si Wei, John P. Giesy, and Hong-Xia Yu. Effects of Perfluorinated Compounds on Development of Zebrafish Embryos. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2012, 19, 2498–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.; Rericha, Y.; Powley, C.; Truong, L.; Tanguay, R.L.; Field, J.A. Background Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (Pfas) in Laboratory Fish Diet: Implications for Zebrafish Toxicological Studies. Sci Total Environ 2022, 842, 156831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushing, Rosie, Christopher Schmokel, Bryan W. Brooks, and Matt F. Simcik. Occurrence of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substance Contamination of Food Sources and Aquaculture Organisms Used in Aquatic Laboratory Experiments. Environ Toxicol Chem 2023, 42, 1463–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, G.; Fjellander, S.; Selvaraj, K.; Vildeval, M.; Ali, Z.; Almter, R.; Erkstam, A.; Rodriguez, G.V.; Abrahamsson, A.; Kersley Å, R.; Fahlgren, A.; Kjølhede, P.; Linder, S.; Dabrosin, C.; Jensen, L. Zebrafish Tumour Xenograft Models: A Prognostic Approach to Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. NPJ Precis Oncol 2024, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, R.V.; Ribeiro, J.M.; Gouveia, H.; de Almeida, C.R.; Castillo-Martin, M.; Brito, M.J.; Canas-Marques, R.; Batista, E.; Alves, C.; Sousa, B.; Gouveia, P.; Ferreira, M.G.; Cardoso, M.J.; Cardoso, F.; Fior, R. Zebrafish Avatar Testing Preclinical Study Predicts Chemotherapy Response in Breast Cancer. NPJ Precis Oncol 2025, 9, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Yi, X.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, L.; Shen, Y.; Zhi, Y.; Liu, T.; Liu, X.; Xu, T.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shou, H.; Huang, P. Zebrafish Patient-Derived Xenograft System for Predicting Carboplatin Resistance and Metastasis of Ovarian Cancer. Drug Resist Updat 2025, 78, 101162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, B.; Estrada, M.F.; Gomes, A.; Fernandez, L.M.; Azevedo, J.M.; Povoa, V.; Fontes, M.; Alves, A.; Galzerano, A.; Castillo-Martin, M.; Herrando, I.; Brandao, S.; Carneiro, C.; Nunes, V.; Carvalho, C.; Parvaiz, A.; Marreiros, A.; Fior, R. Zebrafish Avatar-Test Forecasts Clinical Response to Chemotherapy in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 4771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, X.; Wu, X.; Xu, K.; Zhan, P.; Liu, H.; Zhang, F.; Lv, T.; Song, Y. Zebrafish Patient-Derived Xenografts Accurately and Quickly Reproduce Treatment Outcomes in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2023, 248, 361–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, N.; Fletcher, J.I.; Melong, N.; Lau, L.M.S.; Dolman, E.M.; Mao, J.; Tax, G.; Cadiz, R.; Tuzi, L.; Kamili, A.; Dumevska, B.; Xie, J.; Chan, J.A.; Senger, D.L.; Grover, S.A.; Malkin, D.; Haber, M.; Berman, J.N. Modeling High-Risk Pediatric Cancers in Zebrafish to Inform Precision Therapy. Cancer Res Commun 2025, 5, 1215–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierozan, P.; Karlsson, O. Pfos Induces Proliferation, Cell-Cycle Progression, and Malignant Phenotype in Human Breast Epithelial Cells. Arch Toxicol 2018, 92, 705–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Sun, B.; Berardi, D.; Lu, L.; Yan, H.; Zheng, S.; Aladelokun, O.; Xie, Y.; Cai, Y.; Pollitt, K.J.G.; Khan, S.A.; Johnson, C.H. Perfluorooctanesulfonic Acid and Perfluorooctanoic Acid Promote Migration of Three-Dimensional Colorectal Cancer Spheroids. Environ Sci Technol 2023, 57, 21016–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beccacece, L., F. Costa, J. P. Pascali, and F. M. Giorgi. Cross-Species Transcriptomics Analysis Highlights Conserved Molecular Responses to Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances. Toxics 11, no. 7 (2023).

- Limbu, S., and S. Dakshanamurthy. Predicting Dose-Dependent Carcinogenicity of Chemical Mixtures Using a Novel Hybrid Neural Network Framework and Mathematical Approach. Toxics 11, no. 7 (2023).

- Limbu, S., E. Glasgow, T. Block, and S. Dakshanamurthy. A Machine-Learning-Driven Pathophysiology-Based New Approach Method for the Dose-Dependent Assessment of Hazardous Chemical Mixtures and Experimental Validations. Toxics 12, no. 7 (2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).