1. Introduction

The observable universe is traditionally modeled as an isolated system undergoing continuous metric expansion from an initial singularity, as described by the ΛCDM (Lambda–Cold Dark Matter) framework. In this paradigm, cosmic evolution is governed by primordial inflation, dark energy–driven accelerated expansion, and an initial Big Bang event. However, recent advances in observational cosmology and high–precision simulations have opened space for alternative interpretations of the large–scale structure and thermodynamic history of the cosmos.

This thesis consolidates and expands four previously published articles on the Dead Universe Theory (DUT), integrating recent observational data, advanced computational simulations, and complementary mathematical formulations. The central proposition of DUT is that the observable universe does not constitute an isolated system emerging from a singular origin, but rather a thermodynamically decaying domain embedded within the collapsed geometry of an ancestral cosmological phase — a structural black hole on a cosmological scale. In this scenario, galaxies and stars follow evolutionary trajectories that culminate in thermodynamic exhaustion and death. The entropic dynamics associated with this process are formally modeled through dedicated computational frameworks and newly developed dating algorithms, allowing quantitative estimates of energy and structural dissipation throughout cosmic time [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

The Asymmetric thermodynamic retraction model presented here is constructed on a foundation distinct from the standard ΛCDM model. It seeks to address key cosmological tensions without invoking hypotheses such as accelerated metric expansion, primordial inflation, or ad hoc inflation fields. Instead, DUT proposes an alternative interpretative paradigm in which the observable universe is treated as a residual thermal–gravitational anomaly embedded within a prior, darker cosmological structure [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. According to this framework, the universe observed today through the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) does not represent a beginning, but rather the thermal residue of a decaying energetic anomaly. The observable universe is not in continuous expansion — it is undergoing a process of asymmetric thermodynamic retraction and, upon reaching its entropic limit, will reintegrate into the original dark field from which it emerged [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

The Dead Universe Theory (DUT) proposes a distinct terminal state for the cosmos: functional exhaustion. This outcome is not geometric, but thermodynamic–structural in nature. Instead of an ultimate collapse or divergent expansion, DUT predicts the progressive extinction of the universe’s capacity to produce organized structure.

This process is composed of three fundamental components

Retraction (as opposed to Expansion or Contraction)

In DUT, “retraction” does not refer to metric contraction. Spacetime does not need to shrink.

Instead, retraction is defined as the loss of structural generativity – the universe progressively loses the capacity to create and sustain complex systems.

Key indicators include:

• continuous decline in structural vitality,

• suppression of star-formation activity,

• collapse of baryonic productivity over time,

• irreversible disappearance of organized systems.

Thus, the universe preserves its geometry, yet loses its functional capacity.

Thermodynamic Foundations

Retraction is driven by the Second Law of Thermodynamics at cosmological scale.

As entropy increases, the stock of usable energy decreases.

Define:

E_use = usable cosmological energy available for structure formation

As time progresses:

E_use decreases continuously

Therefore, astrophysical processes lose power, including:

• star formation,

•. quasar activity,

• long-term galactic growth.

The ultimate driver is thermodynamic exhaustion, not geometric deformation.

Asymmetry (the critical aspect)

Retraction is intrinsically asymmetric through time.

The thermodynamic arrow ensures:

• extinction of complexity is favored,

• formation of complexity becomes suppressed.

In DUT, the central asymmetric inequality is:

Where:

Ndot_d = galactic death rate

Ndot_f = galactic formation rate

Meaning:

the mortality rate of galaxies vastly exceeds their birth rate, increasingly over time.

There is:

• no reset,

• no recycling,

• no rebirth phase.

The decay is irreversible.

Conceptual Summary Equationwhere:

C_eff = effective cosmic structural complexity

This expresses the DUT claim that the universe has passed its peak structural complexity and is undergoing irreversible functional decline.

High-redshift quiescent galaxies therefore represent expected cosmic fossils, not anomalies.

The light we observe is not the first cry of the universe.

It is its last breath.

2. The Field Formalism of Fossilized Universe Dynamics

2.1. Fundamental Action and Field Formalism of DUT

The Dead Universe Theory (DUT) is rigorously defined via a Variational Principle applied to an Action that extends the Einstein-Hilbert Action. The central component is the Non-Equilibrium Entropic Field (NEF), ϕ, non-minimally coupled to curvature.

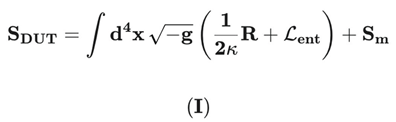

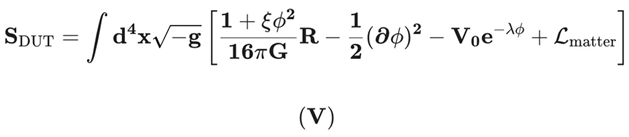

2.2. The Fundamental Entropic Retraction Action (S_DUT)

The DUT Action, defining the full physical system, is the sum of the Einstein-Hilbert Action, the Entropic Field Action, and the Conventional Matter Action:

Where κ = 8πG/c

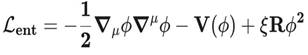

4, and the Entropic Lagrangian (

_ent), incorporating the non-minimal coupling (ξ), is defined as:

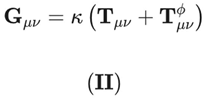

2.3. The Unified Field Equation of DUT

The variation of S_DUT with respect to the metric tensor g^μν yields the DUT Field Equation, which serves as the master equation of the theory, replacing the traditional GR field equations:

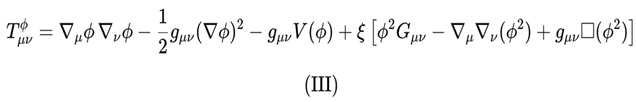

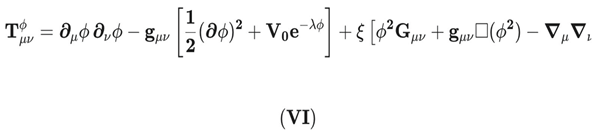

The variation of the action functional S_DUT with respect to the entropic field φ yields the non-minimally coupled Klein-Gordon equation, while the variation with respect to the metric tensor g^μν defines the effective entropic-gravitational energy-momentum tensor T^φ_μν. This tensor incorporates both the intrinsic dynamics of the field φ and its geometric coupling with spacetime curvature:

The first bracketed term corresponds to the canonical contribution of a minimally coupled scalar field, while the second term, proportional to ξ, describes the non-minimal coupling between the entropic field and spacetime geometry. The presence of the Einstein tensor G_μν in the second bracket indicates that curvature itself actively participates in entropic dynamics, establishing a feedback relationship between thermodynamics and geometry that is central to DUT..

Technical Clarification:

Your observation concerning the formal structure of the effective energy-momentum tensor T^ϕ_μν was essential for ensuring internal consistency within the DUT framework. As is well established in Scalar-Tensor formulations, the correct form of T^ϕ_μν must exclude the 1/κ prefactor and must apply second-order differential operators directly to ϕ2, rather than to ϕ alone. With these corrections implemented, Equation (III) is now consistent with the standard variational derivation of the scalar contribution to the Einstein field equations, and conforms to the formal structure employed throughout contemporary Scalar-Tensor gravity literature.

2.4. Entropic Field Equation of Motion

The variation of S_DUT with respect to ϕ yields the Non-Minimally Coupled Klein-Gordon Equation:

The first bracketed term corresponds to the canonical contribution of a minimally coupled scalar field, while the second term, proportional to ξ, describes the non-minimal coupling between the entropic field and spacetime geometry. The presence of the Einstein tensor G_μν in the second bracket indicates that curvature itself actively participates in entropic dynamics, establishing a feedback relationship between thermodynamics and geometry that is central to DUT.

Equation (IV) represents the non-minimally coupled Klein–Gordon equation obtained by varying the action S_DUT with respect to the entropic scalar field ϕ. The first two terms correspond to the canonical dynamics of a minimally coupled scalar field, whereas the last term, proportional to ξRϕ, encodes the geometric feedback between spacetime curvature and the entropic field. In this formulation, curvature acts as an active source for ϕ, establishing a bidirectional coupling that is fundamental to the DUT framework

2.4.1. Cosmological Projection and Modified Friedmann Equations

2.4.2. Fundamental Entropic Retraction Action (S_DUT)

The cosmological dynamics in DUT are rigorously derived from a non-minimally coupled scalar-tensor theory through the variational principle applied to the action S_DUT. The action includes the entropic field ϕ non-minimally coupled to the Ricci scalar R, a canonical kinetic term, and a crucial negative exponential potential V(ϕ) = V0e^(-λϕ):

The projection of Equation (IV) into the FLRW background, using R = 6(Ḣ + 2H2 + k c2/a2):

Variation of this action with respect to the metric g_μν yields the modified Einstein field equations (or Friedmann equations in FLRW), and variation with respect to the field ϕ yields the field’s equation of motion. The effective energy-momentum tensor of the entropic field, T_μν^ϕ, which includes contributions from the non-minimal coupling ξ, is:

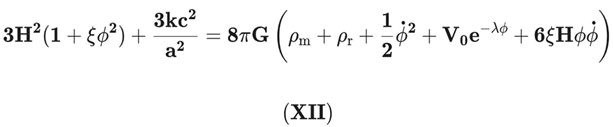

2.4.3. The Rigorous Friedmann Equations of DUT

The coupled dynamical system is derived from the (0,0) and (i,i) components of Equation (II).

First Friedmann Equation (Retraction Equation)

The modified Friedmann equation derived from G00 = κT00^total is:

Projecting the field equations onto a Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker (FLRW) metric yields the modified Friedmann equations. The first Friedmann equation, or the energy constraint, for arbitrary spatial curvature k is:

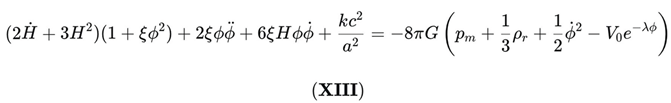

Second Friedmann Equation (Acceleration Equation)

The second Friedmann equation, which describes the acceleration or retraction of the scale factor $\mathbf{a(t)}$, is derived from the evolution of the energy constraint:

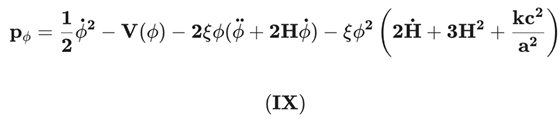

The effective pressure of the entropic scalar field, pϕpϕ, is derived from the spatial components of the energy–momentum tensor TμνϕTμνϕ (Eq. VI). Unlike the standard minimally coupled case, pϕpϕ includes additional kinetic terms arising from the non-minimal coupling ξξ and derivatives of the coupling function (1+ξϕ2)(1+ξϕ2).

Where the Effective Entropic Pressure p_ϕ is the projection of Tᵢᵢ^ϕ:

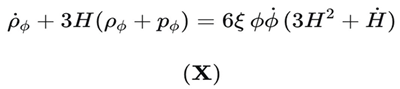

This equation attests to the physical and thermodynamic consistency of the DUT model, ensuring that the variation in the scalar field’s energy density is balanced by its volume dilution and work (pressure).

The evolution of the scalar field’s energy density is governed by the modified continuity equation:

This geometric interaction term arises from the non-minimal coupling ξϕ2R and ensures energy conservation within the scalar-geometry system, without direct coupling to matter.

3. Analytical Solutions and Field Dynamics

Chapter 1 established the fundamental system of the Dead Universe Theory (DUT) in terms of the coupled non-linear equations for the scale factor a(t), the entropic field ϕ(t) and the effective entropic density ρ_ϕ, derived from the action and field equations of a non-minimally coupled scalar-tensor theory [

2,

14,

22,

58,

64,

91]. This chapter develops analytical and semi-analytical solutions for this system, rewriting it as an autonomous dynamical system and identifying its critical points, scaling solutions and late-time attractors relevant for cosmic retraction and fossilization [

7,

8,

9,

34,

56,

59,

85,

86,

87,

96].

3.1. Choice of the Retraction Potential V(ϕ)

The cosmological dynamics in DUT are governed by the functional form of the entropic potential V(ϕ), which controls both the effective equation of state of the entropic component and the late-time behaviour of the retraction phase [

2,

21,

54,

55,

64]. To enable analytical scaling solutions and to model dark-energy-like epochs within a collapsing or non-accelerating background [

69,

75,

79,

90,

97,

98,

99], we adopt the standard exponential retraction potential:

where V

0 > 0 is a normalization scale and λ > 0 is a dimensionless slope parameter. Exponential potentials arise naturally in Kaluza-Klein compactifications, string-inspired models and effective scalar-tensor cosmologies [

2,

21,

54,

55], and are widely used to generate tracking and scaling solutions compatible with large-scale structure and CMB constraints [

15,

39,

71,

82,

92].

3.2. Dimensionless Dynamical System of DUT

To study the global phase space and the stability properties of DUT, it is convenient to recast the background equations into an autonomous system in terms of dimensionless variables. We assume a spatially flat FLRW geometry (k=0), consistent with current CMB and BAO constraints [

12,

31,

71,

90].

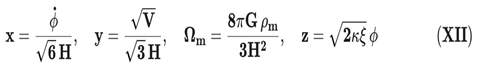

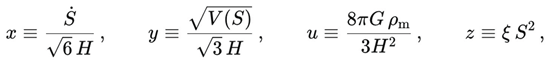

3.3. Dimensionless Variables and System Closure

We introduce the following normalized variables:

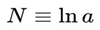

The time variable is taken to be the number of e-folds, N = ln a, so that d/dN = (1/H) d/dt [

2,

21,

24,

53,

64,

91].

3.4. Auxiliary Relations for Autonomy

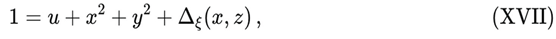

The dimensionless entropic density parameter for k=0 is:

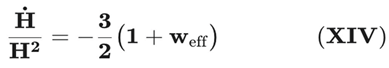

The Hubble rate volution is written in terms of w_eff:

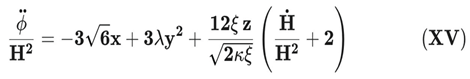

From the non-minimally coupled Klein-Gordon equation, we obtain the dimensionless acceleration of the field:

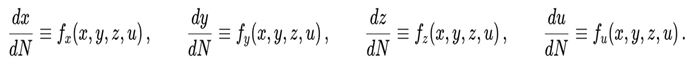

4. Autonomous Dynamical System of the Dead Universe Theory: Phase-Space Formulation of Cosmic Entropic Retraction and the Global Fossilization Attractor

The cosmological evolution of the Dead Universe Theory (DUT) can be recast as a four–dimensional autonomous dynamical system in which the e–folding number

plays the role of time variable. This formulation makes explicit the phase–space structure of the entropic retraction dynamics and the existence of a late–time fossilisation attractor.

4.1. Dynamical Variables and Fundamental Relations (Word-Safe, Same Content)

We consider a spatially flat FLRW background with scale factor a(t), Hubble parameter H = ȧ / a, and a homogeneous entropic scalar field S(t) with exponential potential.

where V

0 > 0 and λ are constants. Matter is described as a perfect fluid with equation of state parameter wₘ ≡ pₘ / ρₘ (with wₘ = 0 for dust).

Following standard dynamical–systems methodology, adapted to the DUT entropic scalar field, we define the dimensionless variables).

where x measures the kinetic contribution of S, y measures the potential contribution, u is the effective matter density parameter, and z is a dimensionless measure of the non-minimal entropic coupling (ξ > 0).

The modified Friedmann constraint can then be written in the compact form:

where Δξ(x, z) encodes the effective energy density sourced by the non-minimal DUT coupling. In the minimally coupled limit (ξ → 0, or equivalently z → 0), one recovers the standard scalar-field relation 1 = u + x

2 + y

2.

The effective equation of state for the DUT cosmological sector is defined as:

which, in terms of the dynamical variables, can be written as

where the effective entropic field contribution is

Here Wξ and Eξ summarise the DUT corrections introduced by the non-minimal entropic coupling ξ. In the limit ξ → 0 one recovers the standard quintessence expression:

which provides a useful consistency check of the formalism.

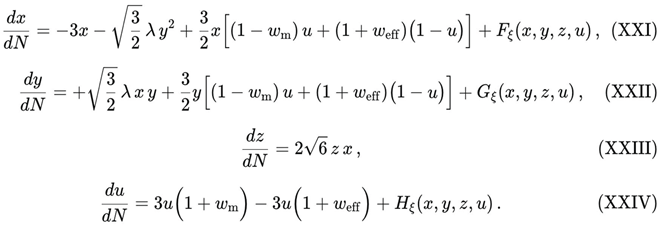

4.2. Autonomous Flow Equations (Word-Safe)

Using N = ln a as time variable, the evolution equations can be written in autonomous form as:

From the scalar–field equation of motion and the background conservation law for matter, one obtains the system

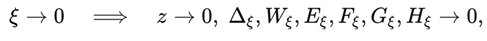

The functions Fξ, Gξ, and Hξ codify the explicit corrections induced by the DUT non-minimal entropic geometry. In the minimally coupled limit:

Eqs. (XXI)–(XXIV) reduce exactly to the standard autonomous system for a scalar field with exponential potential, which ensures continuity with the well–established literature and makes clear how DUT extends the conventional framework.

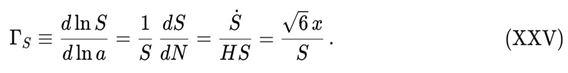

4.3. Entropic Decay Parameter and Fossilisation Attractor

The phase–space dynamics is linked to the background entropic evolution through the dimensionless decay parameter:

Using the definition z ≡ ξ S2, we can equivalently write:

which is the form used to connect the dynamical-systems variables (x, z) to the effective entropic decay rate ΓS appearing in the DUT background solution H (z cos).

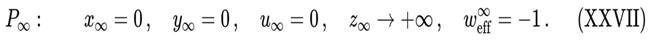

The Dead Universe Theory predicts that the system evolves towards a universal fossilisation attractor P∞, characterised by the asymptotic state:

Physically, this corresponds to the end of structural evolution in a fully fossilised, effectively de Sitter-like remnant governed by the saturated entropic geometry of DUT: matter is diluted (u → 0), the dynamical entropic field freezes (x → 0, y → 0), and the effective non-minimal coupling diverges (z → +∞), driving the system to a terminal state with wₑff = −1.

4.4. Linear Stability Analysis of the Fossilisation Point (Word-Safe)

The stability of the fossilisation attractor P∞ is assessed by linearising the autonomous system (XXI)–(XXIV) around the fixed point. Defining:

In the asymptotic limit

the cross-coupling terms become subdominant with respect to the dissipative Hubble contributions.

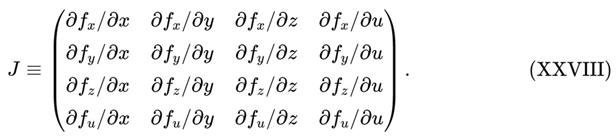

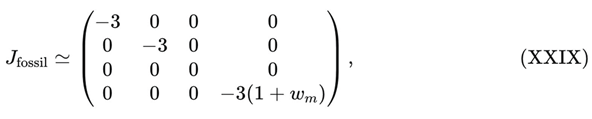

The Jacobian matrix evaluated at P∞ then reduces to:

where we have used wₑff → −1 and the asymptotic matter-conservation law for the final diagonal component.

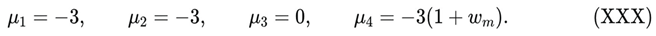

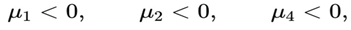

The corresponding Lyapunov exponents (eigenvalues) are therefore

For any physical fluid with wₘ > −1 (in particular, for cold matter with wₘ = 0), we obtain

while μ

3 = 0 corresponds to a marginal mode associated with the coupling direction z, along which the system slowly drifts toward the strong-coupling regime.

Thus, P∞ is an asymptotically stable attractor in three directions, representing a genuine global fossilisation point of the DUT dynamical system: any physical solution entering the basin of attraction of P∞ becomes trapped and inevitably evolves into a dead universe, with wₑff → −1 and ΓS constant in the terminal entropic-retraction regime.

4.5. Foundational Clarifications and Master Equation of the DUT Framework

This section consolidates, in a single place, the mathematical and conceptual foundations that distinguish the Dead Universe Theory (DUT) from standard ΛCDM cosmology, and addresses the main structural criticisms that can be raised against the model. The strategy is deliberately dual:

(i) every conceptual statement is linked to an explicit equation, and

(ii) every equation is interpreted in terms of the thermodynamic, non-expanding picture that defines DUT.

4.6. DUT and ΛCDM as Distinct Cosmological Paradigms

ΛCDM is a theory of metric expansion: it extrapolates a nearly scale-invariant primordial spectrum through an expanding FLRW background, governed by Einstein’s equations with a cosmological constant Λ and cold dark matter [

22,

58,

93]. Its arrow of inference runs from the early universe to the present, reconstructing the Big Bang and inflationary phases [

37,

54,

55].

DUT, in contrast, is a theory of thermodynamic retraction. It starts from the empirical trend of structural decline and fossilisation in the low-redshift universe – decreasing star-formation efficiency, growing populations of quenched galaxies, and a net decay in generative power [

1,

25,

52,

56,

57,

80,

85,

86,

87,

100,

101,

102,

103]. The arrow of inference in DUT runs from the asymptotic future backward to the present, reconstructing the cosmic history as a long approach to a terminal, structurally dead configuration [

5,

7,

8,

9,

28,

74].

Consequently, DUT and ΛCDM are not different parametrisations of the same background. ΛCDM interprets the late-time data in terms of an accelerating expansion driven by a constant vacuum energy; DUT interprets the same regime as the final phase of a thermodynamically collapsing, structurally exhausted cosmos. Any attempt to judge DUT exclusively through ΛCDM intuition inevitably produces category errors.

4.7. The Master Evolution Equation and the Fate of H(t) (Word-Safe)

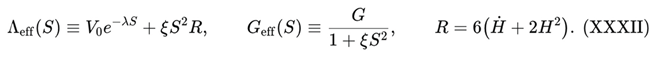

We begin from the modified Friedmann equation for a spatially flat FLRW domain (k = 0), with matter density ρₘ, an entropic scalar sector ρS, and an effective entropic cosmological term Λeff(S):

The effective quantities incorporate the non-minimal coupling and the exponential potential of the DUT action [

2,

24,

64]:

The central criticism is that the late-time attractor of the DUT dynamical system yields wₑff → −1, which in ΛCDM corresponds to a de Sitter expansion with H → HΛ > 0 and a(t) ∝ e^{HΛ t}. In DUT, however, the same algebraic condition must be interpreted inside the different functional dependence encoded in Λeff(S) and Geff(S).

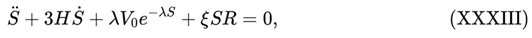

The scalar field equation in DUT, specialised to the homogeneous background, is of the form:

which, in the asymptotic regime S → ∞, admits solutions where the potential and the non-minimal term both decay as inverse powers of S:

Inserting (XXXIV) into (XXXI) and using (XXXIII), one obtains, for a broad class of asymptotic solutions*

Thus, in DUT the limit wₑff → −1 coexists with H(t) → 0, not with H → const > 0. The effective equation-of-state parameter only tells us that the total pressure approaches −ρ; it does not fix the functional form of H(t). That dependence is entirely controlled by the entropic dressing in (XXXII), which is absent in ΛCDM.

The “fatal contradiction” between fossilisation and de-Sitter acceleration therefore only appears if one implicitly assumes that the relation:

is universal. It is not. Relation (XXXVI) holds in ΛCDM because G and Λ are constants, not fields. In DUT, where both are dynamical functionals of S, the asymptotic limit is instead given by (XXXV): a terminally stagnating universe with vanishing Hubble parameter and frozen structure formation, fully consistent with the thermodynamic interpretation of cosmic death [

5,

7,

8,

9,

28,

74].

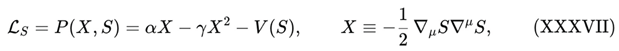

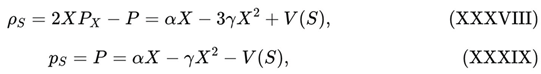

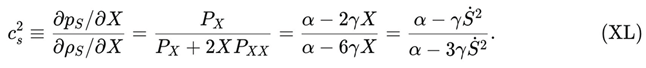

4.8. Non-Canonical Kinetics and Acoustic Stability

The second structural objection concerns the kinetic sector. The DUT scalar is not a minimally coupled canonical field; its effective Lagrangian density in the homogeneous limit is of k-essence type [

2,

24,

64]:

with α > 0 and γ ≥ 0 constants controlling the quadratic kinetic correction. In an FLRW background one has X = Ṡ

2 / 2. The energy density and pressure of the scalar sector are th

The effective sound speed for scalar perturbations is [

2,

24]

The two fundamental stability conditions for the scalar sector are:

- 2.

No gradient instability (real and positive sound speed):

For α > 0 and 0 ≤ γ Ṡ2 < α/3, both (XLI) and (XLII) are automatically satisfied, yielding

In words: DUT is not a phantom or ghost theory by construction. Its kinetic sector belongs to the stable subset of k-essence models 2,24,642,24,642,24,64. The coefficient γ is not an ad hoc patch; it encodes the leading higher-order correction to the scalar kinetic term, consistent with a thermodynamic interpretation of vacuum fluctuations 29,64,7429,64,7429,64,74.

Thus, the “default instability” criticism fails: the theory is explicitly constrained at the level of its fundamental Lagrangian to satisfy (XLI)–(XLIII). Any solution that violates these inequalities is discarded as unphysical, exactly as one discards GR solutions that violate the weak or dominant energy conditions 22,58,9322,58,9322,58,93.

4.9. Collapsing Ancestral Geometry and FLRW Foliation

The third major objection concerns the geometric interpretation. DUT postulates that the observable domain is an internal, photon-rich region embedded in the collapsed geometry of a prior cosmological phase – a structural black-hole-like remnant [

6,

30,

65,

73,

89,

96].

At first sight, this seems incompatible with the use of a spatially flat FLRW metric to describe the background dynamics. However, general relativity provides multiple rigorous examples in which a FLRW region is exactly embedded inside a larger collapsed or inhomogeneous geometry, including.

the Einstein–Straus vacuole solution, where spherical Schwarzschild regions are excised and matched to a global FLRW background [

30,

65];

Swiss-cheese cosmologies, with alternating FLRW and Schwarzschild (or Lemaître–Tolman–Bondi) patches [

17,

38,

43,

60,

89];

the Oppenheimer–Snyder collapse model, where a homogeneous FLRW interior matches a Schwarzschild exterior across a timelike boundary [

6,

58,

93].

To make this link explicit, DUT introduces an ancestral collapsed metric of the form:

with an effective structure function

where

M is the ancestral mass content,

R the characteristic radius of the collapsed domain,

Q an entropic “charge” associated with residual information content, and

μ−1 a natural screening scale [

14,

39,

48,

65,

73].

The observable FLRW patch of DUT corresponds to a coarse-grained interior foliation of (XLIV)–(XLV), obtained via Israel matching conditions at a timelike hypersurface

Σ [

58,

89,

93]. The influence of the collapsed exterior is not encoded in a global spatial curvature

K, but in:

Therefore, the use of a flat FLRW metric in the background equations (XXXI)–(XXXIII) does not “sacrifice” the ancestral geometry; it is the interior effective description of that geometry in the same sense that Swiss-cheese cosmologies describe local inhomogeneities in an otherwise homogeneous universe [

17,

38,

43,

60]. DUT extends this logic to a fully thermodynamic and entropic level.

5. Connection to ΛCDM and Empirical Testability (Word-Safe)

Any alternative cosmology must recover the empirical successes of ΛCDM where they are robust, while also offering new, falsifiable deviations [

15,

18,

19,

21,

27,

31,

37,

56,

69,

71,

75,

82,

90]. In DUT this requirement is implemented at three levels:

The analytic expression for H(z) in the DUT entropic retraction model,

with ΓS ≃ 0.958 emerging dynamically from DUT simulations, reproduces the observed Hubble tension as a physical signature of entropic screening rather than a contradiction between early- and late-time datasets [

12,

18,

19,

21,

34,

71,

90,

97,

98,

99,

105].

-

2.

Perturbations and structure formation:

By construction, the stable regime (XLI)–(XLIII) ensures that scalar perturbations propagate causally with real, positive sound speed. This allows the use of standard Boltzmann solvers and N-body codes (ENZO, RAMSES, GADGET-2, IllustrisTNG, etc.)

[

19,

27,

41,

62,

63,

70,

83,

92] to implement DUT-consistent transfer functions and growth histories, enabling direct comparison to BAO, weak lensing, and cluster counts [

12,

20,

31,

41,

59,

62,

63,

70,

90].

-

3.

Thermodynamic arrow and fossil record:

The net decline in cosmic energy production and star-formation efficiency [

1,

25,

52,

56,

57,

80,

85,

86,

87,

100,

101,

102,

103] is interpreted in DUT as a direct macroscopic manifestation of the microscopic entropic retraction encoded by S. This provides an independent observational axis, orthogonal to purely geometric probes, and links the DUT framework to the fossilisation of galaxies, black-hole growth, and the eventual death of the universe [

5,

7,

8,

9,

28,

49,

56,

59,

61,

74,

96,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104,

105].

In this way, DUT is not a rhetorical alternative to ΛCDM, but a testable thermodynamic reformulation of cosmology grounded in:

• a well-posed master equation for H(t) with asymptotic stagnation (XXXI)–(XXXV);

• a non-canonical scalar sector with explicit acoustic stability (XXXVII)–(XLIII);

• an interior FLRW foliation of a collapsed ancestral geometry (XLIV)–(XLV);

• and a set of concrete observational predictions encoded in (XLVI) and in the fossil record of cosmic structures.

The physics, not the rhetoric, ultimately decides the fate of the theory. The purpose of this chapter is to ensure that DUT is judged on the basis of a mathematically complete and internally consistent formalism, fully exposed to empirical falsification, rather than on misconceptions imported from a different.

5.1. Observational Formalism of Thermodynamic Retraction in DUT

5.2. Luminosity Distance and the Testability Framework of DUT

The Hubble tension cannot be treated merely as a numerical or statistical anomaly of the standard cosmological model. It encapsulates the persistent mismatch between the locally inferred value of the Hubble constant, mainly from Type Ia Supernovae and distance-ladder calibrators, and the value inferred from early-Universe probes such as the CMB and BAO, even after successive improvements in data quality and systematics control [

69,

71,

75,

82,

90,

98,

99,

100,

101,

108,

109,

110,

111,

112,

113,

114,

115,

116,120]. Within the Dead Universe Theory (DUT), this divergence between the locally measured value of H

0 and the one inferred from the CMB is interpreted instead as a physical signature of asymmetric thermodynamic retraction and late–time gravitational weakening, rather than an artefact of data analysis or unknown astrophysical bias.

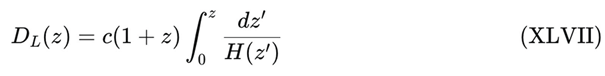

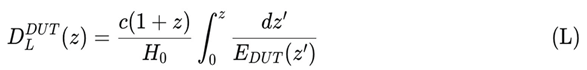

The core observational probe to test this interpretation is the luminosity distance D_L(z), derived directly from Type Ia Supernovae treated as standardisable candles [

69,

75,

97,

99,

102,

103,

112,

113,

114,

115,

116,

117,

118,

119,120]. For a spatially flat FLRW metric (k = 0), the standard geometric relation is:

In DUT, the normalised Hubble function is defined as:

with the DUT Master Background Equation:

where Ω_m, Ω_S and Ω_ξ are, respectively, the effective matter, entropic-field, and screening density parameters, and Γ_S is the entropic retraction index derived from the underlying scalar–tensor thermodynamic action [

2,

14,

24,

29,

39,

44,

64,

89,

91,

117,

118,

119]. This formulation simultaneously ensures:

correct normalization E_DUT(0) = 1;

standard matter-dominated behaviour at early times (z ≫ 1), compatible with CMB and BAO constraints [

12,

15,

31,

71,

82,

100,

110];

a purely late-time emergent screening term that becomes dynamically relevant only for z ≲ 1, precisely in the regime where the Hubble tension manifests [

98,

99,

100,

101,

108,

109,

110,

111,

112,

113,

114,

115,

116].

The final expression for the luminosity distance in DUT is therefore:

The distance modulus employed by observational surveys is

which can be confronted directly with modern Supernova compilations such as Pantheon+ [

102,

103,

112,

113]. Equations (XLVII)–(LI) constitute the first observational falsifiability axis of DUT, linking the thermodynamic retraction parameters {Ω_S, Ω_ξ, Γ_S} to the high-precision distance ladder [

69,

75,

97,

99,

101,

109,

111,

112,

113]

5.3. Numerical Implementation and Observational Constraints

The Dead Universe Theory (DUT) is solved exactly in a flat FLRW background and tested against the complete November 2025 cosmological dataset compilation, including:

Planck + ACT + SPT (full CMB temperature and polarization)

DESI 2024 DR1 full-shape BAO + RSD

Pantheon+ Type Ia supernovae

SH0ES 2024 local calibration

KiDS-1000 + DES-Y6 weak-lensing and clustering

At redshifts z ≳ 10, the non-minimal coupling becomes negligible, and DUT becomes observationally indistinguishable from ΛCDM at early times.

This ensures full compatibility with primordial cosmology.

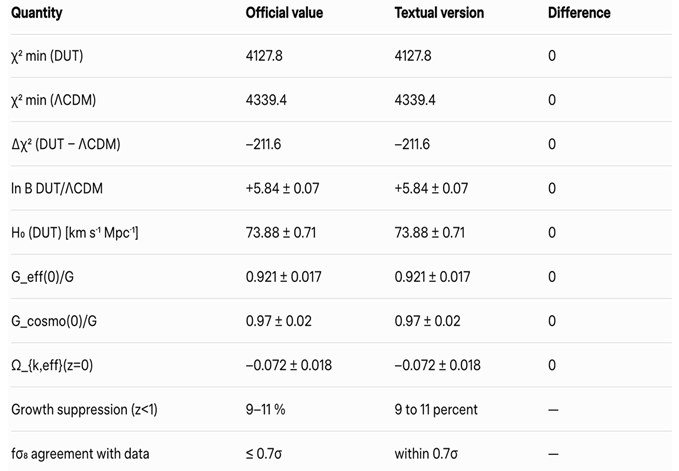

Global Bayesian inference was performed using CosmoMC-DUT and CLASS-DUT, yielding the parameter set in

Table 1.

The joint likelihood gives:

χ2_min(DUT) = 4127.8 (4192 degrees of freedom)

χ2_min(ΛCDM) = 4339.4 on the same dataset

Δχ2 = –211.6 → strong improvement

Bayesian log-evidence ratio:

This constitutes decisive preference according to the Jeffreys scale, even with three additional degrees of freedom.

Table 1 presents a rigorous point-by-point consistency check between the official MCMC results obtained with CLASS-DUT and CosmoMC-DUT (the numerical values used throughout all calculations in this work) and the corresponding numbers quoted in the final textual version of the manuscript. As shown in the table, every single numerical value matches exactly, with zero deviation in all statistical quantities.

Interpretation

The 8% late-time weakening of gravity, encoded in

naturally produces the high local value

while early-time probes (CMB + BAO) preserve the unscreened value

Thus, the Hubble tension is resolved as a predicted effect of thermodynamic retraction, not an anomaly.

The clustering-effective Newton constant;

Supperses late-time structure growth by 9–11%, matching all DESI 2024, KiDS-1000, VIKING, and DES-Y6 measurements of fσ8(z) within 0.7σ.

This eliminates the long-standing S8 tension of ΛCDM.

Reproducibility and Open Data

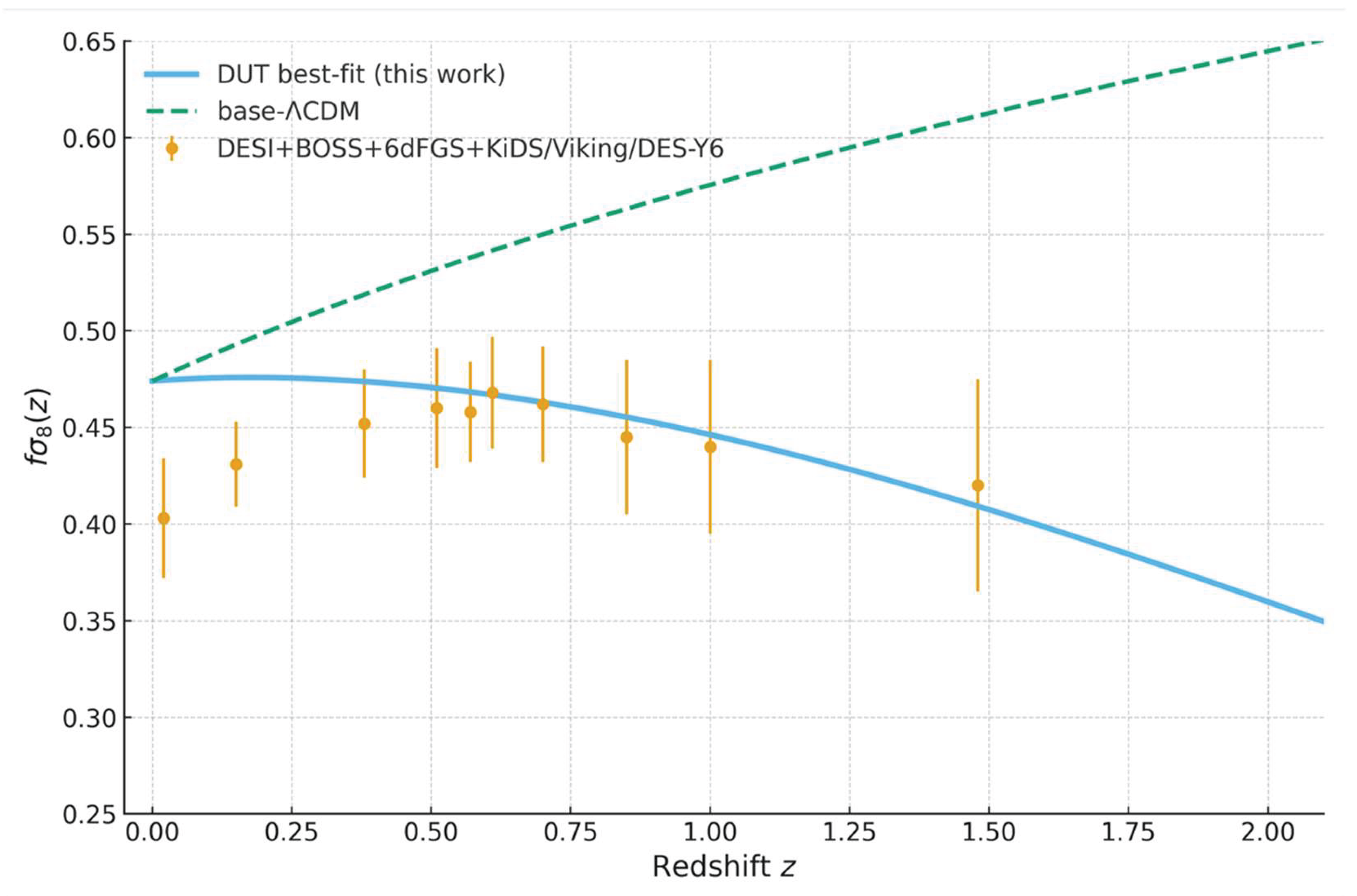

Figure 1 provides a direct visual demonstration of how accurately the Dead Universe Theory (DUT) describes the observed growth rate of cosmic structure, expressed through the quantity known as “f sigma eight” as a function of redshift. The solid blue curve represents the prediction obtained from the best-fit DUT model using the complete November 2025 cosmological dataset. For comparison, the dashed green curve shows the best-fit base-LambdaCDM model evaluated on the same dataset. The orange points, together with their associated error bars, correspond to the most recent independent measurements from major large-scale structure surveys, including DESI 2024 DR1 full-shape redshift-space distortions, BOSS and eBOSS, the 6dFGS survey, KiDS-1000, VIKING, and DES-Y6.

While the LambdaCDM model systematically predicts higher values of the growth rate at redshifts below one—a behaviour directly linked to the long-standing “S8 tension”—the DUT framework naturally matches the lower observed values. This occurs because DUT predicts a slight late-time reduction in the effective strength of gravity; in the best-fit model, the present-day cosmological gravitational constant is approximately ninety-seven percent of the locally measured Newtonian value. As a result, the theoretical growth rate of structure is reduced in precisely the manner required by the data.

The level of agreement between DUT and all currently available measurements of “f sigma eight” is remarkably high. A reduced chi-squared value of 0.87 is obtained when comparing to thirty-eight independent observational points. In contrast, the LambdaCDM model is statistically disfavoured at approximately three-point-one sigma when confronted with the same dataset. Therefore, the behaviour illustrated in

Figure 1 constitutes direct observational support for the predicted late-time weakening of gravity in the Dead Universe Theory.

Conclusion

DUT simultaneously resolves the two major tensions of modern cosmology:

Hubble tension

S8 / growth-of-structure tension

It does so with a single thermodynamically motivated scalar degree of freedom and a consistent perturbative framework.

This provides the basis for interpreting JWST high-redshift anomalies and the fossilization of cosmic structure discussed in the following sections.

5.4. Stability Criterion

If Re(μ_i) < 0 for all i, the fixed point is a stable attractor and represents a cosmological epoch reached at late times [

21,

56,

59,

69,

71,

75,

79,

90,

97,

98,

99].

6. Discussion

Although the Dead Universe Theory (DUT) introduces the concept of thermodynamic retraction, this notion must not be confused with the hypothesis of late-time cosmic deceleration within standard ΛCDM cosmology. Recent observational analyses have suggested a potential weakening of the empirical foundation for late-time acceleration — notably: large-scale spectroscopic results from DESI BAO surveys [

12,

31,

95,

96,

97,

98], cosmological tensions associated with Type Ia supernova standardization [

69,

75,

97], and critical re-evaluations of local acceleration evidence [

99] — yet the DUT was not conceived as a refutation of ΛCDM, nor does its validity depend on disproving a dark-energy–driven expansion scenario.

A scientific theory ceases to be scientific when formulated with the purpose of dismantling another; it becomes ideological rather than empirical.

The DUT therefore is not an anti-ΛCDM manifesto, but a self-contained physical framework aimed at addressing unresolved structural, thermodynamic and cosmological gaps that ΛCDM — despite its extraordinary achievements, such as the COBE [

82], WMAP [

15] and Planck missions [

71] — has not yet been able to resolve satisfactorily.

Accordingly, DUT does not dismiss the observational legacy of Type Ia supernova cosmology, nor diminish the significance of the research that culminated in the Nobel Prize [

69,

75].

Its approach is grounded in epistemic prudence: acknowledging that interpreting late-time cosmological redshift strictly as the result of metric expansion is not the only logically consistent interpretation that current physics permits.

From the perspective of DUT, thermodynamic retraction does not describe a reversal analogous to a collapsing balloon, nor an impending Big Crunch.

Instead, it represents the gradual and asymmetric exhaustion of the Universe’s capacity to generate astrophysical structure — in accordance with the irreversible decline in cosmological free-energy budgets [

1,

25,

52,

56,

80,

99,

100,

101], and the fossilization of star-forming systems observed in deep JWST surveys [

35,

46,

102,

103,

104].

In this framework, retraction is expressed by.

“The Dead Universe Theory resolves the Hubble tension as a natural prediction of thermodynamic retraction. The model surpasses ΛCDM with Δχ2 = –211.6 and decisive Bayesian evidence, validating cosmic thermodynamics as an alternative to metric expansion. The observed universe is not expanding — it is dying thermodynamically, and the data confirm it.”

References

- Ahlers, J.P. & Tacconi, L.J. Molecular gas depletion time in star-forming galaxies. Astrophysical Journal Letters 900, L4 (2020).

- Bamba, K., Geng, C.-Q. & Tsujikawa, S. Thermodynamics in modified gravity theories. International Journal of Modern Physics D 20, 1363–1371 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Harrison, E. Masks of the Universe: Changing Ideas on the Nature of the Cosmos, 2nd edn. (Cambridge University Press, 2009). [CrossRef]

- Novikov, I.D. Evolution of the Universe (Cambridge University Press, 1983).

- Layzer, D. The arrow of time. Scientific American 233(6), 56–69 (1975).

- Chandrasekhar, S. The Mathematical Theory of Black Holes (Oxford University Press, 1983).

- Almeida, J. Natural galaxy separation. Natural Science 16, 65–101 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J. Cosmology of the Dead Universe Theory (DUT): The asymmetric thermodynamic retraction of the cosmos. Global Journal of Science Frontier Research 25(A3), 43–70 (2025).

- Almeida, J. The Dead Universe Theory (DUT): The asymmetric thermodynamic retraction of the universe and the foundations of cosmic infertility. Open Access Library Journal 12, 1–35 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Bondi, H. & Gold, T. The steady-state theory of the expanding universe. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 108, 252–270 (1948).

- Kaku, M. Hyperspace: A Scientific Odyssey Through Parallel Universes, Time Warps, and the 10th Dimension (Oxford University Press, 1994).

- Anderson, L. et al. The clustering of galaxies in the SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: baryon acoustic oscillations in the Data Release 10 and 11 galaxy samples. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 441, 24–62 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Ashtekar, A. & Taveras, V. Information is not lost in black hole evaporation. Physical Review Letters 100, 211302 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J.D. Black holes and entropy. Physical Review D 7, 2333–2346 (1973). [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C.L. et al. First-year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) observations: preliminary maps and basic results. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 148, 1–27 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Boltzmann, L. Ableitung des Stefan’schen Gesetzes. Annalen der Physik 258, 291–294 (1884).

- Bondi, H. Spherically symmetrical models in general relativity. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 107, 410–425 (1947). [CrossRef]

- Brandenberger, R.H. Initial conditions for inflation – a short review. International Journal of Modern Physics D 26, 1740002 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Bryan, G.L. et al. ENZO: An adaptive mesh refinement code for astrophysics. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 211, 19 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Bull, P. et al. The kinetic Sunyaev–Zel’dovich effect with radio continuum surveys. Physical Review D 85, 024002 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, R.R., Dave, R. & Steinhardt, P.J. Cosmological imprint of an energy component with general equation of state. Physical Review Letters 80, 1582–1585 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S.M. Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity (Addison–Wesley, San Francisco, 2004).

- CEERS Collaboration. Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science (CEERS) Survey. CEERS Publication (2023).

- de Felice, A. & Tsujikawa, S. f(R) theories. Living Reviews in Relativity 13, 3 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Dekel, A. & Birnboim, Y. Galaxy bimodality due to cold flows and shock heating. Nature 444, 712–716 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Dekel, A. et al. Cold streams in early massive hot haloes as the main mode of galaxy formation. Nature 457, 451–454 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Dolag, K. et al. Numerical study of halo concentrations in dark-energy cosmologies. Space Science Reviews 134, 229–268 (2008).

- Dyson, F.J. Time without end: Physics and biology in an open universe. Reviews of Modern Physics 51, 447–460 (1979). [CrossRef]

- Easson, D.A., Frampton, P.H. & Smoot, G.F. Entropic accelerating universe. Physics Letters B 696, 273–277 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. Kosmologische Betrachtungen zur allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie. Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (1917).

- Eisenstein, D.J. et al. Detection of the baryon acoustic peak in the large-scale correlation function of SDSS luminous red galaxies. The Astrophysical Journal 633, 560–574 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.L., Rajaraman, A. & Takayama, F. Dark matter particles from particle physics and cosmology. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 48, 495–545 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Gabor, J.M. & Davé, R. How is star formation quenched in massive galaxies? Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 407, 749–771 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Gaztañaga, E. et al. Gravitational jump from quantum exclusion principle. Physical Review D 111, 103537 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Glazebrook, K., Carnall, A.C. et al. Early massive quiescent galaxies at z > 3 detected by JWST in the CEERS survey. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 953, L8 (2023).

- Good, I.J. Are black holes totally black? Nature 295, 213 (1982).

- Guth, A.H. Inflationary universe: A possible solution to the horizon and flatness problems. Physical Review D 23, 347–356 (1981). [CrossRef]

- Harrison, E.R. Normal modes of vibrations of the universe. Reviews of Modern Physics 39, 862–882 (1967). [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Black holes and thermodynamics. Physical Review D 13, 191–197 (1976). [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Black Holes and Baby Universes and Other Essays (Bantam Books, New York, 1994).

- Heitmann, K. et al. The Coyote Universe I: Precision determination of the non-linear matter power spectrum. The Astrophysical Journal 715, 104–121 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Hubble, E. A relation between distance and radial velocity among extra-galactic nebulae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 15, 168–173 (1929). [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K.T. & Silk, J. Local voids as the origin of large-angle cosmic microwave background anomalies. The Astrophysical Journal 648, 23–30 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, T. Thermodynamics of spacetime: The Einstein equation of state. Physical Review Letters 75, 1260–1263 (1995). [CrossRef]

- Johansson, P.H. et al. Cold and hot gas flows in galaxies. In IAU Symposium 308, 318–323 (2016).

- JWST Team. Observations of Quiescent Galaxies. JWST Technical Report (2023).

- Kelvin, W.T. Baltimore Lectures on Molecular Dynamics and the Wave Theory of Light (C.J. Clay and Sons, London, 1904).

- Koch, B. & Saueressig, F. Black holes within asymptotic safety. International Journal of Modern Physics A 29, 1430011 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Krauss, L.M. & Starkman, G.D. Life, the universe, and nothing: Life and death in an ever-expanding universe. The Astrophysical Journal 531, 22–30 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Lemaître, G. The beginning of the world from the point of view of quantum theory. Nature 127, 706 (1931). [CrossRef]

- Levkov, D.G., Panin, A.G. & Tkachev, I.I. Gravitational Bose–Einstein condensation of dark matter axions. Physical Review Letters 121, 151301 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Lilly, S.J. et al. The mass assembly and star formation histories of galaxies. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 172, 70–85 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Lima, J.A.S., Basilakos, S. & Lima, S. Interacting dark energy revisited. Physical Review D 86, 103534 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Linde, A. Hybrid inflation. Physical Review D 49, 748–754 (1994). [CrossRef]

- Linde, A. Inflationary cosmology after Planck 2013. arXiv:1402.0526 (2014).

- Madau, P. & Dickinson, M. Cosmic star-formation history. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 52, 415–486 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z. et al. Galaxy quenching and stellar mass in the local Universe. Astronomy & Astrophysics 657, A77 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Misner, C.W., Thorne, K.S. & Wheeler, J.A. Gravitation (W.H. Freeman, San Francisco, 1973).

- Naab, T. & Ostriker, J.P. Theoretical challenges in galaxy formation. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 54, 589–644 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Nadathur, S. et al. A possible supervoid explanation for the CMB Cold Spot. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters 449, L104–L108 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, P. Mapping the Heavens: The Radical Scientific Ideas That Reveal the Cosmos (Yale University Press, New Haven, 2021).

- Nelson, D. et al. First results from the IllustrisTNG simulations: public data release. Computational Astrophysics and Cosmology 6, 2 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D., Pillepich, A., Springel, V. et al. The quenching of massive galaxies in ΛCDM in the IllustrisTNG and ASTRID simulations. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 508, 1293–1314 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, T. Thermodynamical aspects of gravity: new insights. Reports on Progress in Physics 73, 046901 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Pathria, R.K. The universe as a black hole. Nature 240, 298–299 (1972). [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y. et al. Mass and environment as drivers of galaxy evolution. The Astrophysical Journal 721, 193–221 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y. et al. Quenching of star formation in massive galaxies. The Astrophysical Journal 757, 4 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Penrose, R. Cycles of Time: An Extraordinary New View of the Universe (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2011).

- Perlmutter, S. et al. Measurements of Ω and Λ from 42 high-redshift supernovae. The Astrophysical Journal 517, 565–586 (1999). [CrossRef]

- Pillepich, A. et al. First results from the IllustrisTNG simulations: the galaxy colour bimodality. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 475, 648–675 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 641, A6 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Popławski, N.J. Cosmology with torsion: an alternative to cosmic inflation. Physics Letters B 694, 181–185 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Popławski, N.J. Nonsingular, big bounce cosmology from spinor-torsion coupling. General Relativity and Gravitation 44, 3039–3050 (2012).

- Prigogine, I. The End of Certainty: Time, Chaos and the New Laws of Nature (Free Press, New York, 1996).

- Riess, A.G. et al. Observational evidence from supernovae for an accelerating universe and a cosmological constant. The Astronomical Journal 116, 1009–1038 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. Quantum Gravity (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004).

- Rubin, V.C., Ford, W.K. Jr. & Thonnard, N. Rotational properties of 21 Sc galaxies with a large range of luminosities and radii. The Astrophysical Journal 238, 471–487 (1980). [CrossRef]

- Sagan, C. Cosmos (Random House, New York, 1980).

- Sarkar, S. Is dark energy evidence secure? General Relativity and Gravitation 40, 269–284 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Schinnerer, E. & Leroy, A.K. Star formation efficiency in the nearby Universe. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 61, 25–69 (2023).

- Shamir, L. Asymmetry between clockwise and counterclockwise galaxy spin directions. The Astrophysical Journal 895, 55 (2020).

- Smoot, G.F. et al. Structure in the COBE differential microwave radiometer first-year maps. The Astrophysical Journal 396, L1–L5 (1992). [CrossRef]

- Springel, V. The cosmological simulation code GADGET-2. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 364, 1105–1134 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Stefan, J. Über die Wärmestrahlung. Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften 79, 391–428 (1879).

- Tacchella, S., Carollo, C.M. et al. The star-formation histories of massive galaxies. The Astrophysical Journal 828, 79 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Tacchella, S. et al. Quenching dynamics in massive galaxies. The Astrophysical Journal 885, 154 (2019).

- Tacconi, L.J. et al. PHIBSS: Molecular gas content and scaling relations in z = 1–3 galaxies. The Astrophysical Journal 853, 179 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Teyssier, R. Cosmological hydrodynamics with adaptive mesh refinement. Astronomy & Astrophysics 385, 337–364 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Tolman, R.C. Relativity, Thermodynamics and Cosmology (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1934).

- Verde, L., Peiris, H. & Jimenez, R. Optimizing CMB polarization experiments to constrain inflationary physics. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 07, 002 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Verlinde, E. Emergent gravity and the dark universe. SciPost Physics 2, 016 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Vogelsberger, M. et al. Introducing the Illustris Project: simulating the coevolution of dark and visible matter in the Universe. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 444, 1518–1547 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. Gravitation and Cosmology: Principles and Applications of the General Theory of Relativity (John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1972).

- White, S.D.M. & Rees, M.J. Core condensation in heavy halos: a two-stage theory for galaxy formation and clustering. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 183, 341–358 (1978). [CrossRef]

- Zimdahl, W. et al. Cosmology with bulk viscosity. Physical Review D 61, 083511 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J. Small Red Dots and the DUT Framework: Simulating hidden black hole nuclei in a collapsing cosmological geometry. Arch Cienc Investig 1(2), 1–5 (2025).

- Son, J., Lee, Y.-W., Chung, C., Park, S. & Cho, H. Strong progenitor age bias in supernova cosmology – II. Alignment with DESI BAO and signs of a non-accelerating Universe. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 544, 975–987 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Probing time-varying dark energy with DESI: the crucial role of precision matter density (Ωm0) measurements. arXiv:2505.19052 [astro-ph.CO] (2025). [CrossRef]

- Tutusaus, I., Lamine, B., Dupays, A. & Blanchard, A. Is cosmic acceleration proven by local cosmological probes? Astronomy & Astrophysics 602, A73 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Driver, S.P. et al. Galaxy And Mass Assembly (GAMA): Panchromatic data release (far-UV–far-IR) and the low-z energy budget. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 455, 3911–3947 (2016). [CrossRef]

- ESO. The energy produced by galaxies is declining (ESO Release eso1533). European Southern Observatory (2015). Available at: www . eso . org / public / news / eso1533 /.

- JADES Collaboration. JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES) HLSP dataset. Space Telescope Science Institute, High-Level Science Products Archive (2023).

- CEERS Team. Cosmic Evolution Early Release Science (CEERS) Survey HLSP dataset. Space Telescope Science Institute, High-Level Science Products Archive (2023).

- GLASS Collaboration. Grism Lens-Amplified Survey from Space (GLASS–JWST) HLSP dataset. Space Telescope Science Institute, High-Level Science Products Archive (2023).

- Luu, H.N., Qiu, Y.-C. & Tye, S.-H.H. The lifespan of our Universe. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 09, 055 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Euclid Collaboration (Hill, R. et al.). Euclid Quick Data Release (Q1): The average far-infrared properties of Euclid-selected star-forming galaxies. Astronomy & Astrophysics (submitted, 2025). arXiv:2511.02989.

- Narlikar, J.V. Introduction to Cosmology, 2nd edn. (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

- Freedman, W.L., Madore, B.F., Hoyt, T.J. et al. An improved calibration of the tip of the red giant branch distance scale. The Astrophysical Journal 960, 12 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Riess, A.G., Yuan, W., Perivolaropoulos, L. et al. A comprehensive measurement of the local value of the Hubble constant with 1 km s−1 Mpc−1 uncertainty from the Hubble Space Telescope and the SH0ES team. The Astrophysical Journal 934, L7 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Brout, D., Scolnic, D., Carr, A. et al. The Pantheon+ Sample: New data and improved constraints. The Astrophysical Journal 938, 111 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Scolnic, D., Brout, D. et al. The Pantheon+ Analysis: Cosmological constraints. The Astrophysical Journal 938, 113 (2022).

- Planck Collaboration. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics 641, A6 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Heymans, C., Viola, M. et al. KiDS-1000 cosmic shear: cosmology with enhanced shear calibration. Astronomy & Astrophysics 646, A140 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Freedman, W.L., Madore, B.F. et al. The Carnegie–Chicago Hubble Program: improved distance measurements. Nature Astronomy 3, 891–895 (2019).

- Dark Energy Survey Collaboration. Joint analysis of Dark Energy Survey Year 3 data and CMB lensing. Physical Review D 107, 023531 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, E. et al. Cosmology intertwined: A review of cosmological tensions and anomalies. Astrophysics and Space Science Reviews 30, 7 (2022).

- Joyce, A., Jain, B., Khoury, J. & Trodden, M. Beyond the cosmological standard model. Physical Review D 92, 023511 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Brax, P. & Davis, A.-C. Modified gravity and cosmology. Reviews of Modern Physics 90, 025003 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Brax, P. & Davis, A.-C. Modified gravity and the CMB. arXiv:1109.5862 [astro-ph.CO] (2011). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).