1. Introduction

A biomarker is generally defined as any quantifiable parameter that reflects a specific biological condition, process, or response. The World Health Organization characterizes biomarkers as “almost any measurement reflecting an interaction between a biological system and an environmental agent, which may be chemical, physical, or biological.” [

1]. Historically, biomarkers have been extensively applied in diverse research fields, including human health diagnostics, ecotoxicology, and environmental monitoring [

2,

3]. Over time, their development and refinement have allowed increasingly sensitive detection of physiological disturbances, early stress responses, and subclinical health alterations in organisms [

4,

5].

In aquaculture, the implementation of biomarkers has expanded considerably in the past two decades, driven by the need to improve health management, optimize production conditions, and enhance the sustainability of farming systems. Biomarkers are now routinely employed to assess oxidative stress (e.g., antioxidant enzymes, lipid peroxidation markers), immune function (e.g., lysozyme activity, cytokine expression), metabolic status (e.g., glucose, lactate, hepatic enzyme activity), and endocrine responses in cultured fish species [

6,

7,

8]. They also provide early indicators of exposure to pollutants, temperature stress, hypoxia, poor water quality, and pathogen challenges, allowing intervention before clinical disease manifests [

9,

10]. Additionally, biomarker-based approaches are integral to evaluating the impacts of nutrition, stocking density, and climate-related stressors—such as salinity and thermal fluctuations—on fish performance and welfare [

11,

12]. Consequently, biomarkers have become essential tools for advancing sustainable aquaculture, enabling more precise health monitoring, supporting selective breeding for resilience, and informing adaptive farm management practices. In addition, the use of biomarkers in aquaculture represents an effective approach for assessing the nutritional, immunological, oxidative, physiological, and overall health status of farmed fish [

1]. Biomarker-based evaluations allow the early detection of potential adverse effects arising from dietary modifications, operational stressors, and pathogenic challenges [

13,

14]. By providing timely and objective information, these tools enable producers to implement targeted management actions, mitigate health risks, and ultimately reduce losses in production [

1].

The application of biomarkers across European aquaculture has evolved from isolated research assays to integrated, operational tools for nutrition, health surveillance, welfare assessment, and environmental exposure monitoring. Large multinational initiatives and EU-funded programmes (e.g., ARRAINA and the AQUAEXCEL series) have developed standardized biomarker panels, methodological guidance, and data repositories for key species such as Atlantic salmon, rainbow trout, common carp, European sea bass and gilthead sea bream, thereby facilitating comparability among laboratories and farms across Mediterranean and Atlantic systems [

15,

16]. In Norway, the United Kingdom and other northern-European salmon-producing countries, proteomic and serum-based biomarker studies have produced candidate early-warning indicators for viral and bacterial diseases [

17,

18,

19,

20]—work that supports development of rapid immunoassays and on-farm diagnostics [

21]. In southern Europe (e.g., Spain, Greece, Italy) extensive research on gilthead sea bream and European sea bass has validated non-lethal biomarkers of nutritional status, oxidative stress and immune function, and generated physiological reference ranges useful for routine farm monitoring and feed evaluation [

22]. Finally, recent European studies have demonstrated the utility of minimally invasive matrices (e.g., blood, fin clips), novel oxidative biomarkers (e.g., 8-OHdG), and omics-driven discovery to operationalize biomarker monitoring in recirculating and open-sea systems—advances that are enabling more proactive, evidence-based interventions to improve welfare and reduce production losses across the continent [

23]. All these examples highlight the use of biomarkers in European aquaculture, which is increasingly recognized as an essential approach to monitor fish nutrition, stress response, and overall health, although no information exist about awareness, current practices, barriers, and potential for biomarker application among aquaculture professionals across Europe. Due to that a questionnaire-based survey was conducted in order to collect such data, while it was expected that the findings would have contributed to the objectives of the CA22160 COST Action BIOAQUA, fostering knowledge exchange, standardization, and stakeholder engagement. The objectives of this survey-based research were 1. To assess awareness and understanding of biomarkers in aquaculture, 2. Identify types of biomarkers currently in use, 3. Evaluate their influence on management decisions and 4. Explore barriers to adoption and potential support mechanisms

2. Materials and Methods

The used tool for conducting such survey was Google Forms, which was further improved after testing them with some colleagues and stakeholders (in total 3 of them). The participants were Management Committee members of the COST Action and related stakeholders (researchers, fish farm managers, veterinarians, feed manufacturers). They were invited 2 times by through emails while providing instructions and having appreciations by some of them. The response collection corresponds to the time period July–August 2025. The survey structure was represented by the following sections: Section 1: General information (country, institution, experience, and aquaculture systems); Section 2: Awareness and understanding; Section 3: Biomarkers in use; Section 4: Influence on decision-making; Section 5: Barriers and support needs and Section 6: Future potential and follow-up.

3. Results

3.1. General Description About the Survey Participants

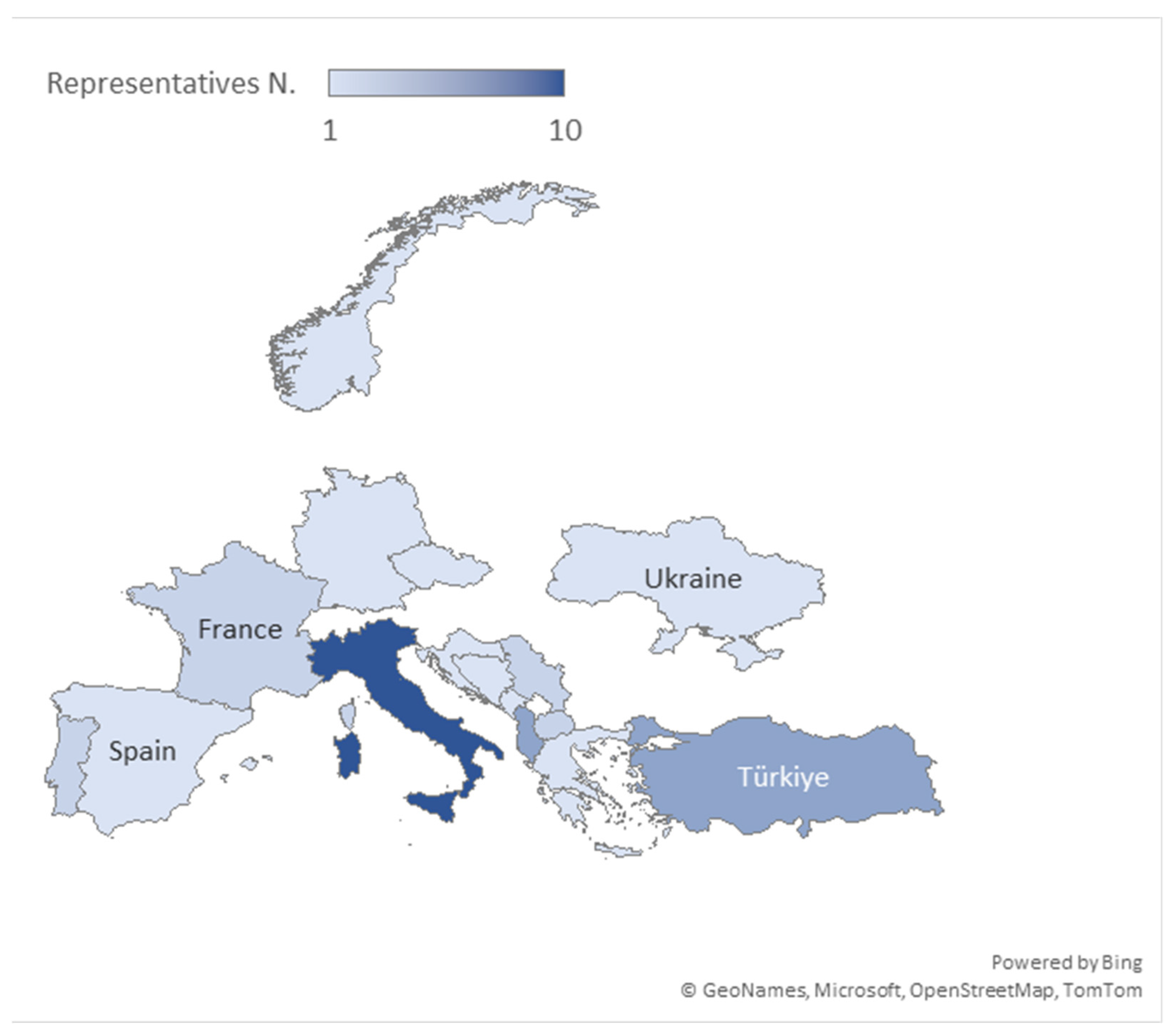

As, it is shown by the graphic of the

Figure 1, the online survey included the responses of 38 participants from 17 different countries of Europe, which were represented by Albania, Montenegro, Serbia, Ukraine, France, (including experienced researcher from Tunisia), Germany, North Macedonia, Portugal, Norway, Spain, Italy, Türkiye, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Czech Republic and Greece. The most represented countries are represented by Italy (with 10 participants), followed by Türkiye and Albania, with 5 participants, respectively, as shown by the intensity of blue color in the

Figure 1.

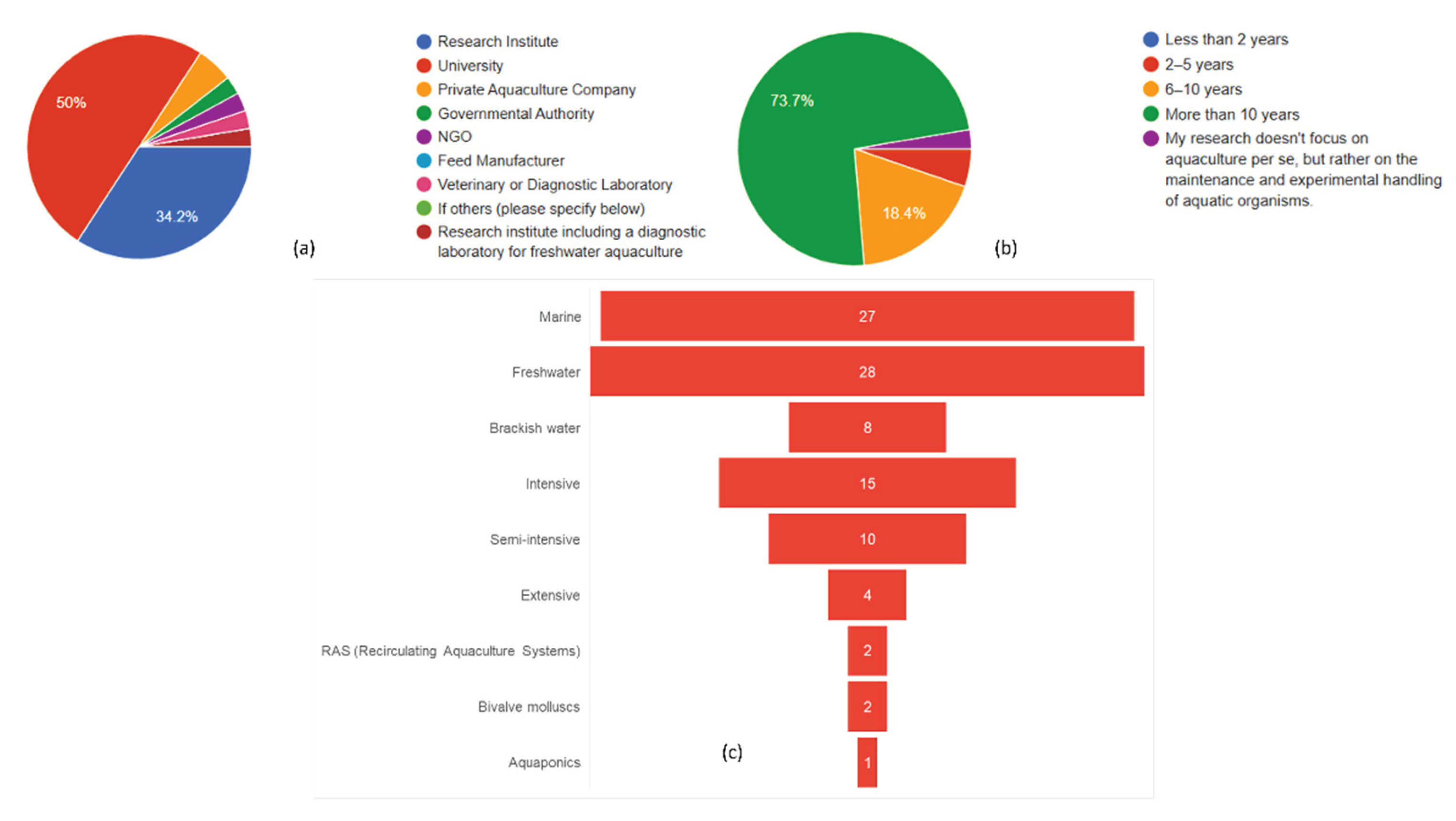

The respondents’ institutions (

Figure 2a) were dominated by universities (50%) and research in-stitutes (34.2%), followed by private aquaculture companies (5.3%). Regarding the years of expe-rience (

Figure 2b), the majority had more than 10 years in aquaculture (about 74%), while about 18% of them had an experience from 6 up to 10 years in aquaculture. It means that more than 90% of the respondents are experienced in the aquaculture sectors, according to the survey re-sults. The aquaculture systems used by the survey participants was mainly represented freshwater aquaculture systems (73.7%), followed by marine (71.1%) ones, while most of them are using in-tensive aquaculture systems (39.5%), including RAS systems, as it is shown in

Figure 2c.

3.2. Awareness and Understanding of Biomarkers by Aquaculture Stakeholders

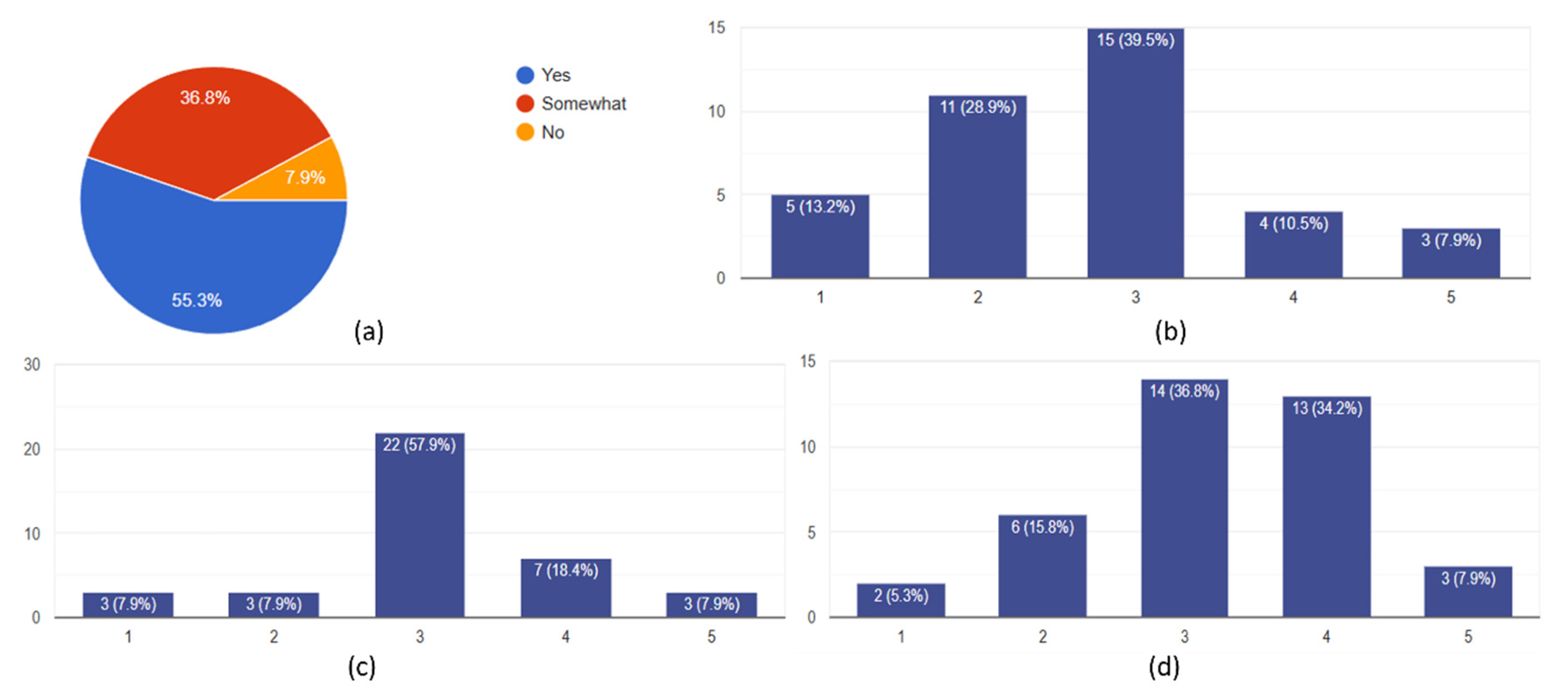

Most respondents were familiar with the concept of biomarkers, as it is shown in

Figure 3a, where it resulting that just about 8% of them were not familiar with this concept applied in aquaculture. Regarding the questions about the knowledge level about the fish nutrition biomarkers and other biomarkers used for stress assessment, health and disease, and environmental impact, below are shown the graphics corresponding to each of the biomarker’s categories.

As shown in

Figure 3b, most of the survey participants knowledge rate about biomarkers used for fish nutrition corresponds to level 3, which means that the level of knowledge is good, but not very good or excellent, corresponding to level 4 and 5, respectively. It is interesting to note that about 29% of the survey participants have sufficient knowledge about their use for fish nutrition. Regarding the other category of biomarkers (

Figure 3c), it is observed a decrease in percentage of the participants who have no knowledge or have sufficient knowledge on biomarkers used for stress assessment. It is also observed a higher rate in comparison to the previous Figure graphic of the participants who have good knowledge (about 58%). It is also interesting to note (

Figure 3d) that the survey participants have good (36.8%) and very good knowledge (34.2%) of biomarkers used for health status and disease detection, while the percentage of those who considered them-selves as experts for all these categories is about 8%.

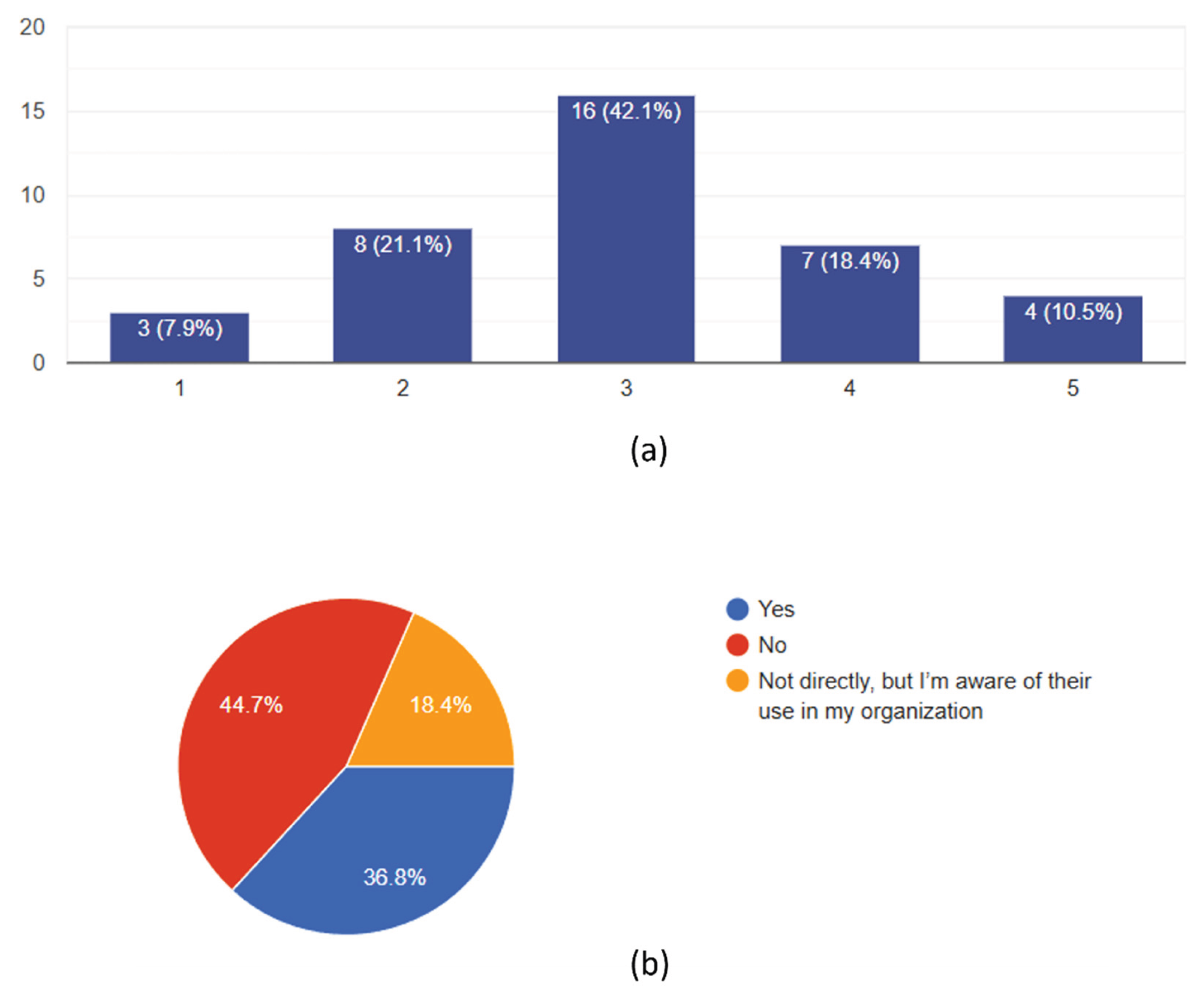

Regarding the biomarkers used for environmental impact evaluation (

Figure 4a), though most of the respondents have good knowledge on their use for such purpose, it is observed an increased percentage of those who consider themselves to have sufficient knowledge (about 21%) regarding their use for environmental impact evaluation. In addition, most of the survey participants an-swered negatively to the question “Have you ever used or been involved in a project using bi-omarkers in aquaculture (

Figure 4b; about 45%), though 37% of them declared to have used or been involved in a project using biomarkers in aquaculture, while others were indirectly aware (18.4%).

3.3. General Description About the Survey Participants

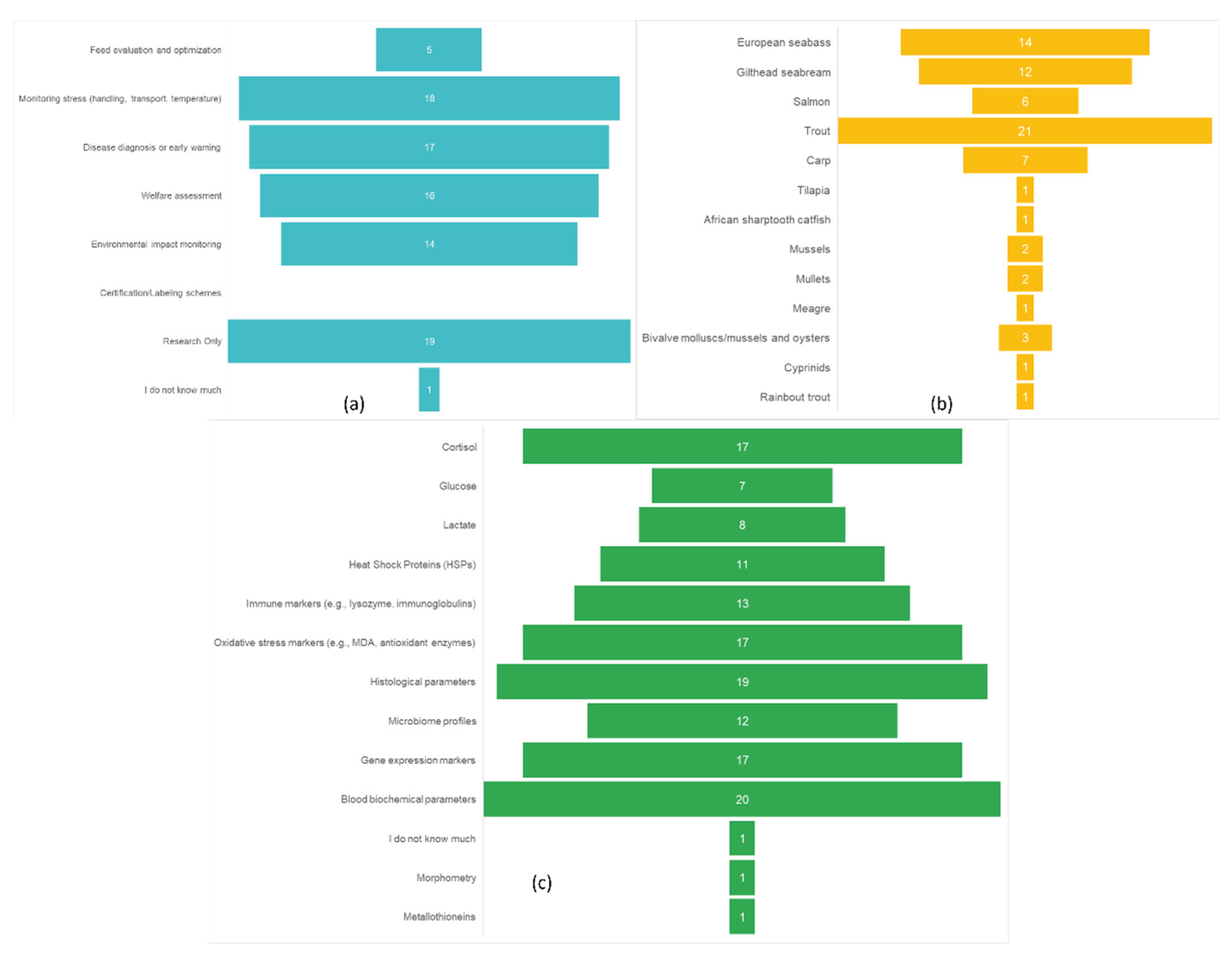

In order to know the applications, in the survey (

Figure 5a) it was included the multiple choices question “for which purpose are these biomarkers primarily used in your context?”. It resulted that the main purpose was exclusively for research, which is supported by 50% of the survey par-ticipants. More specifically, they are used primarily for stress monitoring, disease diagnosis, wel-fare assessment and environmental impact monitoring, while just about 13% of the participants are using them primarily for feed evaluation and optimization (13.2%).

To the question “in which species do you apply biomarker analyses?”, most of the participants answered (

Figure 5b; in a decreasing order), that the species were trout (55.3%), European seabass (36.8%), gilthead seabream (31.6%), carp (18.4%) and salmon (15.8%), while the remaining ones mostly declared to apply biomarker analyses on bivalve mollusks and mullet species. Based on the answers of the survey participants (

Figure 5c), it resulted that the most common biomarkers are blood biochemical parameters and histological parameters, while other common biomarkers are represented by cortisol, oxidative stress markers and gene expression markers. At a lesser use or aware in operations or research are those represented by glucose, lactate, heat shock proteins, immune markers and microbiome profiles.

3.4. Influence on Decision-Making

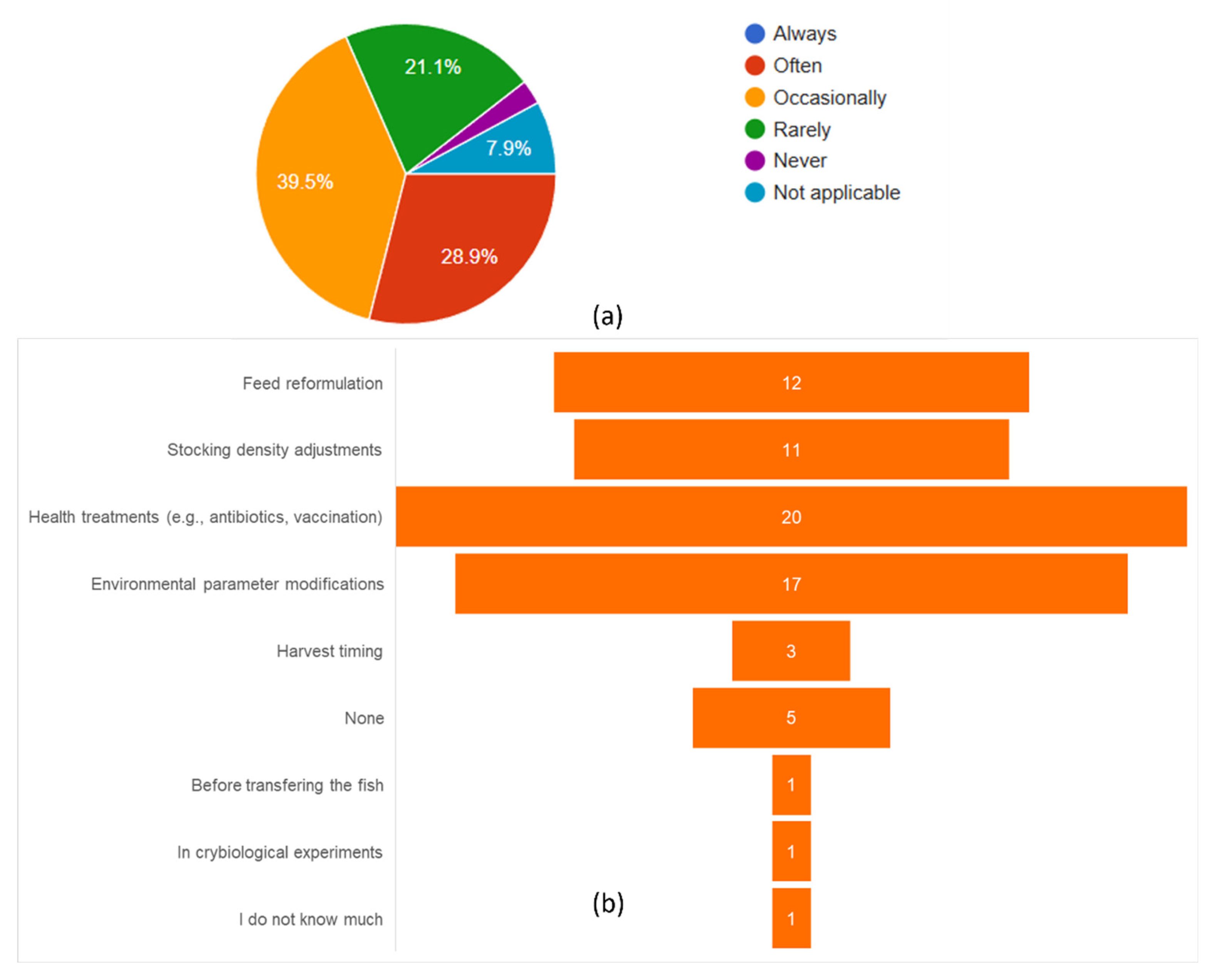

Based on the survey participants response to the question about the frequency in which bi-omarkers results influence management or operational decisions (e.g., feed formulation, treatment plans), it comes out that biomarker results influenced decisions occasionally for health treatments and feed reformulation (supported by a percentage of about 39.5% of survey respondents), while none of them selected the “Always” option, as it is shown in

Figure 6a. It is also critical to note that about 21% of the respondents declared that rarely, the biomarkers results influence manage-ment or operational decisions. The health treatments decisions are mainly influenced by bi-omarkers results according to the resulting responses in the graphic of

Figure 6b, while other im-portant decisions under the influence of biomarkers results are represented in a decreasing order by environmental parameter modifications, feed formulation and stocking density adjustments.

3.5. Barriers, Challenges and Support Needs

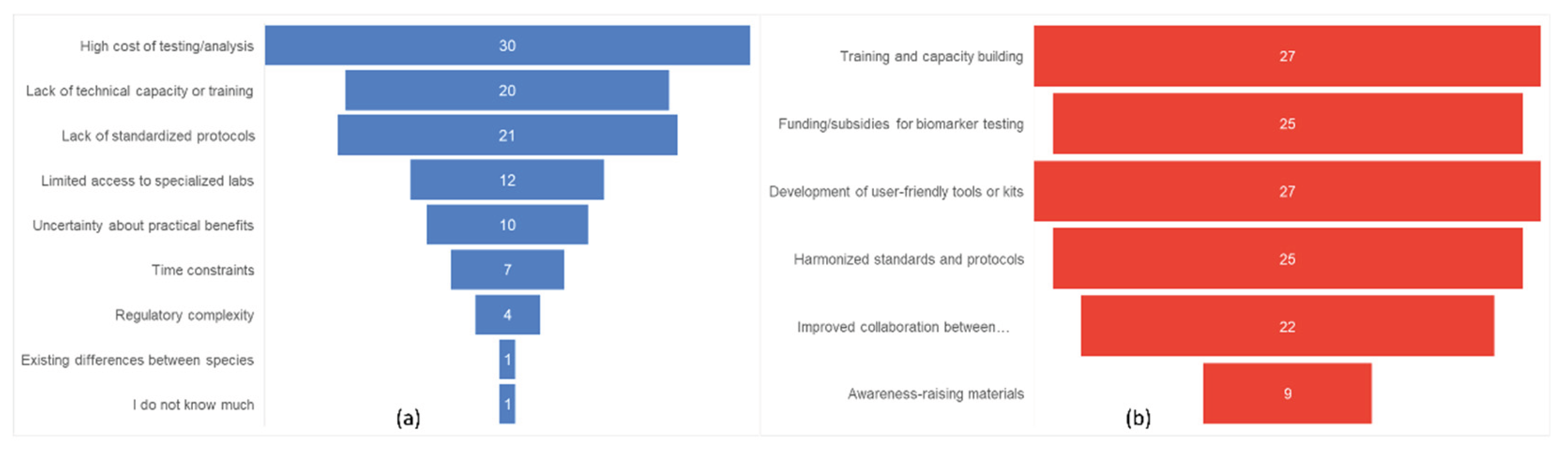

Key barriers preventing the wider use of biomarkers in the aquaculture context reported by most of the survey participants (

Figure 7a; more than 50% of respondents) are represented by high cost of testing/analyses (about 79% of the answers), lack of technical capacity or training (52.6%) and lack of standardized protocols (55.3%). However other barriers (in a decreasing order of supported respondents’ percentage) are represented by limited access to specialized laboratories, uncertainty about practical benefits, time constraints and regulatory complexity.

As it is shown in

Figure 7b, most of the support should be focused on training and capacity build-ing (according to about 71% of the survey respondents) and development of user-friendly tools and kits (about 71%), while in the second position are included the funding/subsides for bi-omarker testing and harmonized standards and protocols (65.8% each of them). It is interesting to note that improved collaboration between researchers and industry is positioned in the third place (57.9%).

3.6. Future Outlook

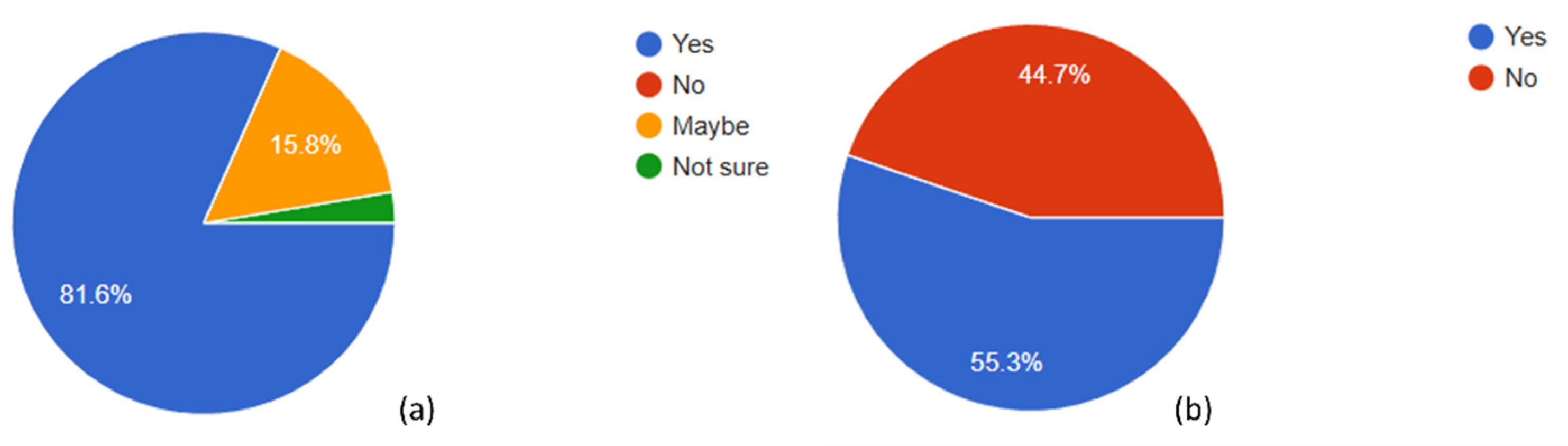

Based on the survey’s results shown in the pie chart of

Figure 8a, it is evident that there is poten-tial for greater use of biomarkers in aquaculture in the near future, because the majority of survey participants (about 82%) see strong potential for wider biomarker use in the near future. In addi-tion, about 55% of them expressed the will to participate in a follow-up interview or share further insights, while 28 respondents provided email addresses for further engagement (

Figure 8b).

4. Discussion

The survey findings provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of awareness, application, and perceived value of biomarkers in European aquaculture. The demographic distribution of respondents (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) demonstrates wide geographical participation, suggesting that interest in biomarker-based approaches extends across multiple regions and production systems. Such broad engagement aligns with recent European research efforts that have emphasized the growing relevance of biomarkers for advancing sustainable aquaculture practices [

7,

8,

24].

Levels of awareness and knowledge among stakeholders (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) varied substantially, highlighting a mixture of advanced expertise and limited familiarity. This heterogeneity reflects broader patterns described in recent reviews, which note that while biomarker research has developed rapidly, its transfer into routine aquaculture operations remains uneven across countries and species [

1,

13,

14]. These gaps emphasize the need for improved knowledge dissemination and training to support effective adoption.

The use of biomarkers in practice (

Figure 5) demonstrates that growth, stress response, immune function, reproduction, and disease resistance constitute the most commonly applied categories. This aligns with established literature identifying these physiological domains as central targets for biomarker development in farmed species such as Atlantic salmon, rainbow trout, gilthead sea bream, and European sea bass [

25,

26]. Moreover, the apparent emphasis on finfish rather than shellfish corresponds with the historical concentration of European aquaculture research funding toward finfish physiology, omics-based biomarker discovery, and disease management [

8,

9]. Nevertheless, growing interest in shellfish health indicators suggests that diversification of biomarker applications is emerging.

Figure 6 reveals that biomarker information influences decision-making to varying degrees. Many respondents reported that biomarker data have informed operational choices such as adjusting feeds, modifying husbandry practices, and managing disease outbreaks. These observations are consistent with studies showing that physiological and immunological biomarkers can provide early-warning indicators that support proactive health management and enhance welfare outcomes [

7,

10]. Other studies have demonstrated that biomarker-driven evaluations of nutrition and stress can improve feed formulation and reduce mortality under commercial conditions [

25,

26].

Despite these benefits, significant barriers to biomarker implementation persist (

Figure 7a). Cost of analyses, limited technical capacity, and absence of standardized protocols were the most frequently cited obstacles. These challenges mirror longstanding concerns in the literature, where authors have emphasized the need for harmonized methodologies, validated reference ranges, and standardized sampling protocols to enable consistent use across laboratories and production systems [

1,

13,

14]. In addition, the technical demands of certain biomarker assays—particularly omics-based approaches—remain prohibitive for smaller producers, reinforcing the need for cost-effective diagnostic tools and shared analytical infrastructures.

The additional reflections from respondents (

Figure 7b) further emphasize the sector’s priorities: expanded training opportunities, financial support for biomarker testing, and the development of harmonized standards. These needs have been highlighted in multiple European research assessments, which stress that capacity building and methodological alignment are critical for scaling biomarker applications across aquaculture systems [

7,

8].

Figure 8 also show that many respondents expressed interest in continued engagement, suggesting strong motivation to participate in collaborative initiatives aimed at improving biomarker use.

Overall, the survey results indicate a positive trajectory in biomarker adoption within European aquaculture. Awareness is growing, applications are diversifying, and biomarker-derived data are already contributing to health and management decisions. However, the full potential of these tools remains limited by financial, technical, and institutional constraints. To address these challenges, the following priorities emerge from both survey data and scientific literature:

Standardization of methodologies, including harmonized protocols for sampling, analysis, and data interpretation [

1,

7].

Investment in cost-reduction strategies, such as development of rapid assays, simplified diagnostic kits, and shared laboratory capacities [

1,

9].

Expansion of training and knowledge transfer, to bridge gaps in technical expertise and support evidence-based use of biomarkers [

8,

24].

Strengthening research on the operational value of biomarkers, with emphasis on quantifying economic and welfare benefits in commercial conditions [

25,

26].

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this survey results reinforce the growing momentum behind bi-omarker-based approaches in European aquaculture while clearly identifying the structural and methodological improvements needed to realize their full benefits. Co-ordinated research, investment, and standardization efforts will be crucial in enabling biomarkers to transition from experimental tools to routine components of sustainable aquaculture management.

Funding

This research was funded by Virtual Mobility (VM) grant of COST Action CA22160—Enhancing knowledge of BIOmolecular solutions for the well-being of European aquaculture sector (BIOAQUA). The VM was focused on the collection and analysis of data on biomarkers used in European aquaculture, with particular attention to their role in fish nutrition, stress response, and overall health. The APC was funded by Rigers Bakiu, based on the accumulated vouchers as reviewers for different MDPI journals.

Acknowledgments

My thanks go to COST Action CA22160 colleagues (in particular Anna Toffan and Konstantina Bitchava) and all the suggested stakeholders, who kindly contributed to the survey. We thank the anonymous reviewers for their careful reading of our manuscript and their many insightful comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Oliveira, J.; Oliva-Teles, A.; Couto, A. Tracking Biomarkers for the Health and Welfare of Aquaculture Fish. Fishes 2024, 9, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, D.; Brothers, M.C.; Slocik, J.M.; Islam, A.E.; Maruyama, B.; Grigsby, C.C.; Naik, R.R.; Kim, S.S. Biomarkers and Detection Platforms for Human Health and Performance Monitoring: A Review. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2104426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, P.K.S. Use of biomarkers in environmental monitoring. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2009, 52, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.P.; Calduch-Giner, J.; Sitjà-Bobadilla, A.; Nácher-Mesyre, J.; Waagbo, R.; Berntssen, M.H.G.; Skiba, S.; Sándor, Z.; Montero, D.; Terova, G. Understanding Biomarkers in Fish Nutrition—Technical Booklet. ARRAINA—Advanced Research Initiatives for Nutrition and Aquaculture 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Varó, I.; Navarro, J.C.; Nunes, B.; Guilhermino, L. Effects of dichlorvos aquaculture treatments on selected biomarkers of gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata L.) fingerlings. Aquaculture 2007, 266, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, S.M.; Muhammed, R.E.; Mohamed, R.E. Assessment of biochemical biomarkers and environmental stress indicators in some freshwater fish. Env. Geo. Health 2024, 46, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowden, T.J. Modulation of the immune system of fish by their environment. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2008, 25, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tort, L. Stress and immune modulation in fish. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2011, 35, 1366–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnie-Gauvin, K.; Costantini, D.; Cooke, S.J.; Willmore, W.G. A comparative and evolutionary approach to oxidative stress in fish: A review. Fish Fish. 2017, 18, 928–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grădinariu, L.; Crețu, M.; Vizireanu, C.; Dediu, L. Oxidative Stress Biomarkers in Fish Exposed to Environmental Concentrations of Pharmaceutical Pollutants: A Review. Biology (Basel). 2025, 14, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendelaar Bonga, S.E. The stress response in fish. Physiol Rev. 1997, 77, 591–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pörtner, H.O.; Peck, M.A. Climate change effects on fishes and fisheries: towards a cause-and-effect understanding. J. Fish Biol 2010, 77, 1745–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Oost, R.; Beyer, J.; Vermeulen, N.P. Fish bioaccumulation and biomarkers in environmental risk assessment: a review. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2003, 13, 57–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, J.A.; Jones, M.B.; Leonard, D.R.; Owen, R.; Galloway, T.S. Biomarkers and integrated environmental risk assessment: are there more questions than answers? Integr Environ Assess Manag. 2006, 2, 312–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terova, G.; Díaz, N.; Rimoldi, S.; Ceccotti, C.; Gliozheni, E.; Piferrer, F. Effects of sodium butyrate treatment on histone modifications and the expression of genes related to epigenetic regulatory mechanisms and immune response in European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) fed a plant-based diet. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sánchez, J.; Benedito-Palos, L.; Estensoro, I.; Petropoulos, Y.; Calduch-Giner, J.A.; Browdy, C.L.; Sitjà-Bobadilla, A. Effects of dietary NEXT ENHANCE®150 on growth performance and expression of immune and intestinal integrity related genes in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata L.). Fish Shell Immunol. 2015, 44, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimoldi, S.; Benedito-Palos, L.; Terova, G.; Pérez-Sánchez, J. Wide-targeted gene infers tissue-specific molecular signatures of lipid metabolism in fed and fasted fish. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2016, 26, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, P.A.J.; Schrama, J.W.; Kaushik, S.J. Mineral requirements of fish: a systematic review. Rev. Aqua. 2014, 6, 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Calduch-Giner, J.A.; Sitjà-Bobadilla, A.; Pérez-Sánchez, J. Gene expression profiling reveals functional specialization along the intestinal tract of a carnivorous teleostean fish (Dicentrarchus labrax). Front. Phys. 2016, 7, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estensoro, I.; Calduch-Giner, J.A.; Kaushik, S.; Pérez-Sánchez, J.; Sitjà-Bobadilla, A. Modulation of the IgM gene expression and IgM immunoreactivity cell distribution by the nutritional background in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) challenged with Enteromyxum leei (Myxozoa). Fish Shell Immunol. 2012, 33, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, F.; Black, L.E.; Thompson, K.D.; Sourd, P.; Bordeianu, A.; Chadwick, C.C.; Moghadam, H.; Del-Pozo, J.; Costa, J.; Burchmore, R.; Brady, N.; Moore, L.; McGill, S.; McLaughlin, M.; Eckersall, P.D. Serum Biomarkers in Atlantic Salmon for Differential Diagnosis of Cardiomyopathy Syndrome and Pancreas Disease: Proteomic Identification of Serum Fibrinogen to Enhance Troponin Immunoassay as Optimal Diagnostic Approach. J Fish Dis. 2025, 48, e14151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelakopoulos, R.; Tsipourlianos, A.; Fytsili, A.E.; Moutou, K.A. Establishing the Physiological Values of Minimally Invasive Biomarkers in Gilthead Sea Bream (Sparus aurata). Fishes 2025, 10, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sundfør, E.B.; Klokkerengen, R.; Gonzalez, S.V.; Mota, V.C.; Lazado, C.C.; Asimakopoulos, A.G. Determination of the Oxidative Stress Biomarkers of 8-Hydroxydeoxyguanosine and Dityrosine in the Gills, Skin, Dorsal Fin, and Liver Tissue of Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) Parr. Toxics 2022, 10, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiocchi, E.; Civettini, M.; Carbonara, P.; Zupa, W.; Lembo, G.; Manfrin, A. Development of molecular and histological methods to evaluate stress oxidative biomarkers in sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 46, 1577–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costas, B.; Aragão, C.; Mancera, J.M.; Dinis, M.T.; Conceição, L.E.C. Physiological responses of fish to stressors used in aquaculture, with particular reference to the gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata). Fish Physiol Biochem. 2011, 37, 283–296. [Google Scholar]

- Magnoni, L.J.; Martos-Sitcha, J.A.; Palstra, A.P. Energy homeostasis in teleosts: biomarker, regulatory pathways, and applications in aquaculture. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2017, 203, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).