Submitted:

25 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Cloud Platform Solutions for Network Slicing Orchestration

2.2. Kubernetes Network Virtualization Solutions

2.2.1. CNI Plugins

2.2.2. Kubernetes Service Meshes

2.2.3. Evolution of Kubernetes Virtual Networking

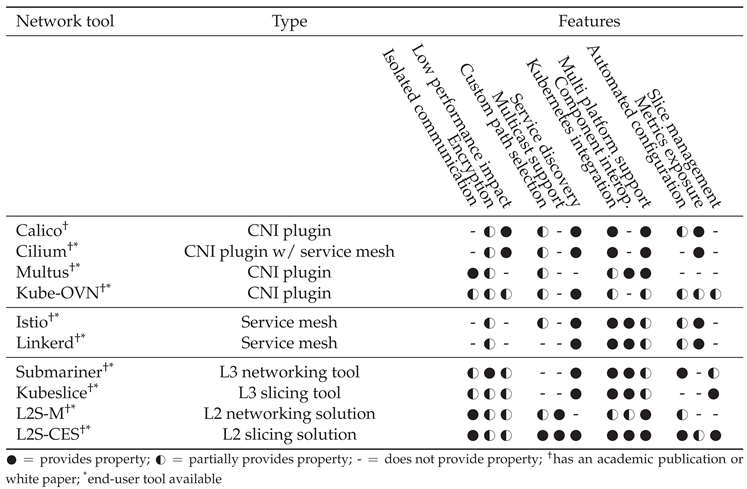

2.3. Features Comparison of Existing Solutions

- Isolated communication: Refers to the possibility to isolate traffic for security reasons, in such a way that a pod can be isolated from the rest of the network. L2S-M and L2S-CES support multiple isolated virtual networks, the core functionality provided. Kubeslice and Submariner have similar features through a virtualization of some services like using NSM in Kubeslice and route agents in Submariner, which have certain isolation but don’t contemplate scenarios with multiple micro-segments, kind of how L2S-CES allows multiple virtual networks at the same time. Using manual setup, Multus, and Kube-OVN can provide this kind of functionality, but it requires that the user changes the configuration inside the host.

- Encryption: Encrypted traffic thanks to technologies like IPSec. Submariner has an implementation with strongSwan [35]. L2S-CES inherently allows for the use of any encryption mechanism by supporting layer-2 communications. Other solutions, such as service meshes and CNI plugins provide certain encryption thanks to mutual TLS (mTLS), which authenticates using TLS from both ends, but this is limited to certain protocols and is derived from the user.

- Low-performance impact: low impact on the network performance. Standard in most solutions, and a key feature in Calico and Cilium, as they use eBPF which allows efficiency and high performance in the network. By contrast, service meshes don’t comply in general in terms of efficiency as they commonly use sidecars containers which act as middlemen in the communication, producing additional overhead. L2S-CES inherited tunnels from L2S-M does not negatively impact the inherent network performance [36].

- Traffic engineering: Unique feature in L2S-CES, as it allows custom path creation by specifying the desired path in the network topology for each virtual network. This can be used for multiple purposes, (e.g. quality of service, security).

- Multicast support: support for a variety of multicast and broadcast protocols. By being a layer-2 solution, both L2S-M and L2S-CES can provide scenarios with this type of traffic. The current alternative in other scenarios would be a complex set-up with Multus and a VPN in the cluster.

- Service Discovery: capability to expose microservices and make them accessible automatically without manual intervention. This is commonly integrated within the Kubernetes Service API, by CNI plugins and service meshes. L2S-CES has this feature through its custom multi-domain DNS implementation.

- Kubernetes integration: Degree to which the solution is Kubernetes-native. L2S-CES exposes slice lifecycle and policy as Kubernetes resources; Submariner and Kubeslice integrate via Kubernetes operators atop the primary CNI; CNI plugins (e.g., Calico, Cilium, Kube-OVN) are natively integrated as the cluster network layer.

- Component interoperability: how the component is compatible with other components. Submariner, Kubeslice and L2S-CES are agnostic in terms of the primary CNI plugin, so they integrate well while giving more characteristics. Service meshes are fully integrated with the base CNI plugin as well.

- Multiplatform support: support for multiple platforms to work together, i.e.; public and private cloud, k3s cluster with bare metal cluster, etc. L2S-CES allows the connection of one virtual or physical machine to a microservice if required, thanks to SDN.

- Automated configuration: refers to the automation in configuring the solution to start using it. One of the improvements of L2S-CES is its automation in slice management and configuration, whereas with Kubeslice it is required a deep understanding of the tool. Submariner has a CLI with many automated features. Other solutions require a much more complex setup as it is not natively built into the tool, Calico and Cilium for instance, which do not have much documentation available, and Kube-OVN requires you to set up ECMP Tunnels which is not an easy task.

- Metrics exposure: Common feature with service meshes, where performance metrics are exposed. L2S-CES has a built-in tool for latency, bandwidth and jitter measurements.

- Slice management: Ability to define, instantiate, modify, and delete slices dynamically at runtime. L2S-CES offers fully dynamic slice management with per-slice path selection; other solutions provide coarser or manual slice-like constructs with limited slice segmentation.

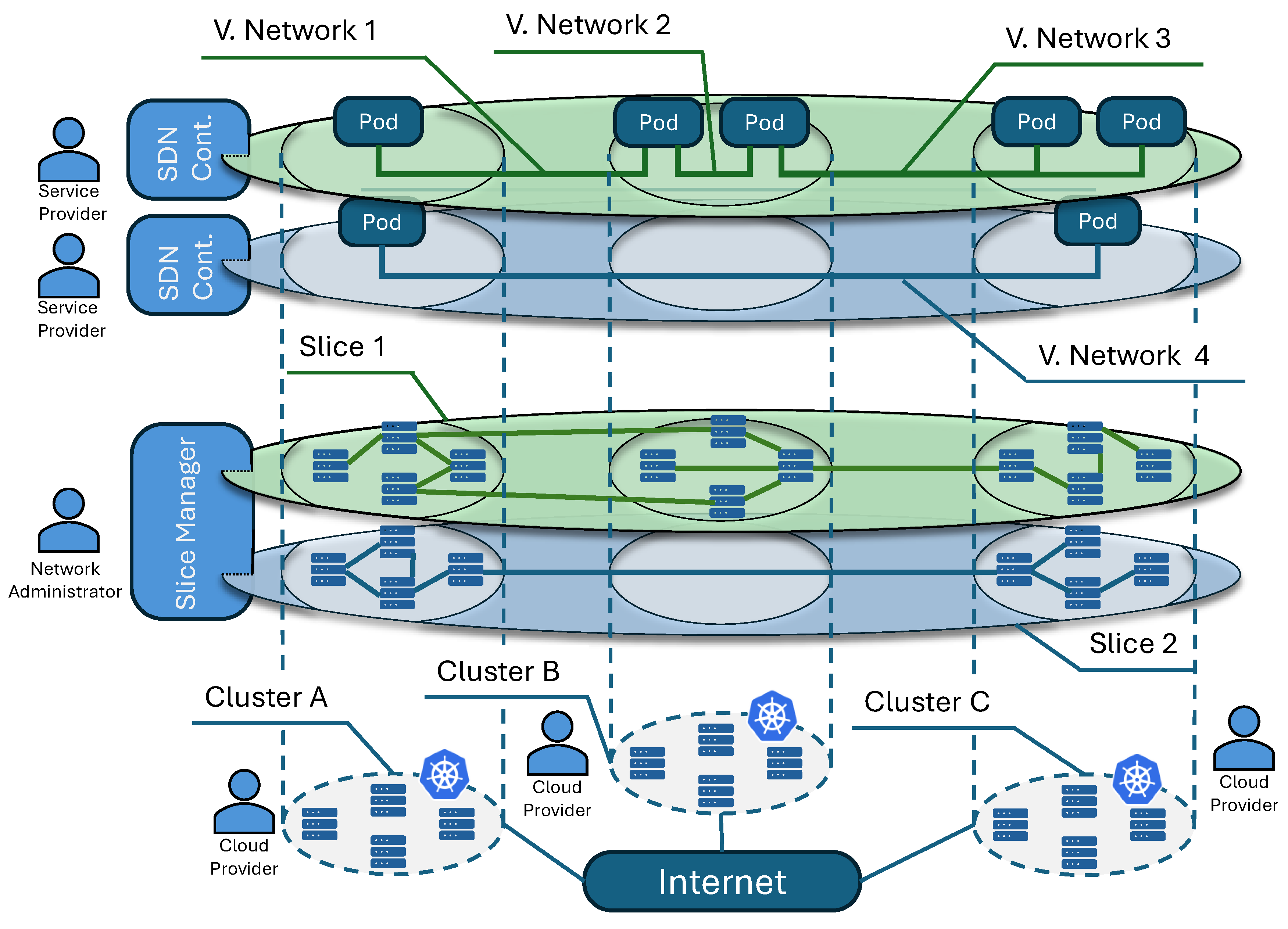

3. Design

3.1. Key Design Concepts

- Heterogeneous platform support: Provide a user-friendly API and command-line interface (CLI) to create isolated environments in Kubernetes clusters enabling users to easily establish network slices that host virtual networks. Multiple tenants can dynamically join these slices and communicate without concern for the heterogeneity of the underlying infrastructure.

- Isolated network communication: Ensure secure, isolated communication between containers within and across Kubernetes clusters, spanning multiple domains and cluster types. A single slice may contain one or multiple isolated networks, which are accessible on-demand.

- Platform-agnostic deployment: Provide scalability and adaptability as part of the solution.

- Flexible provisioning: Enable the provisioning of slices attending to underlying resources, like deciding the topology of interconnection between the multiple clusters and computing nodes.

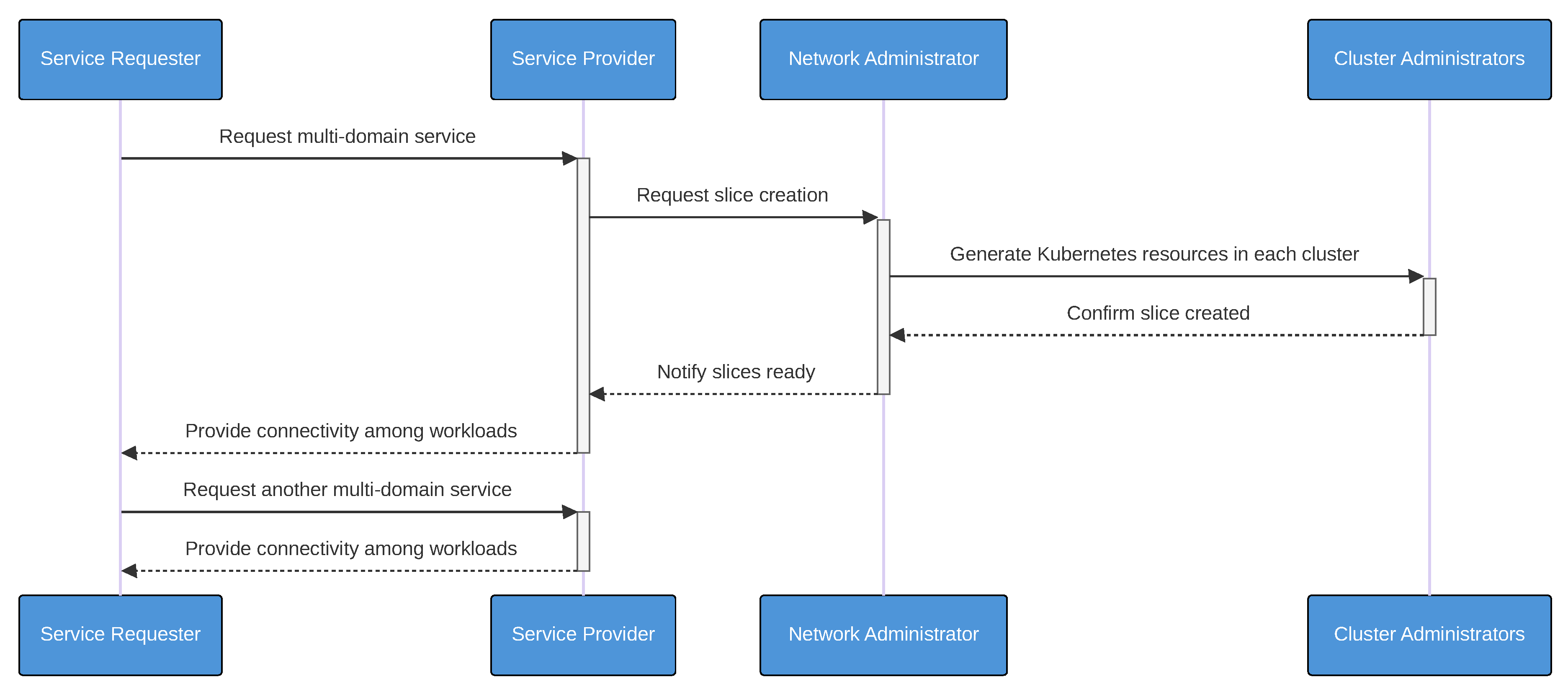

3.2. Actors

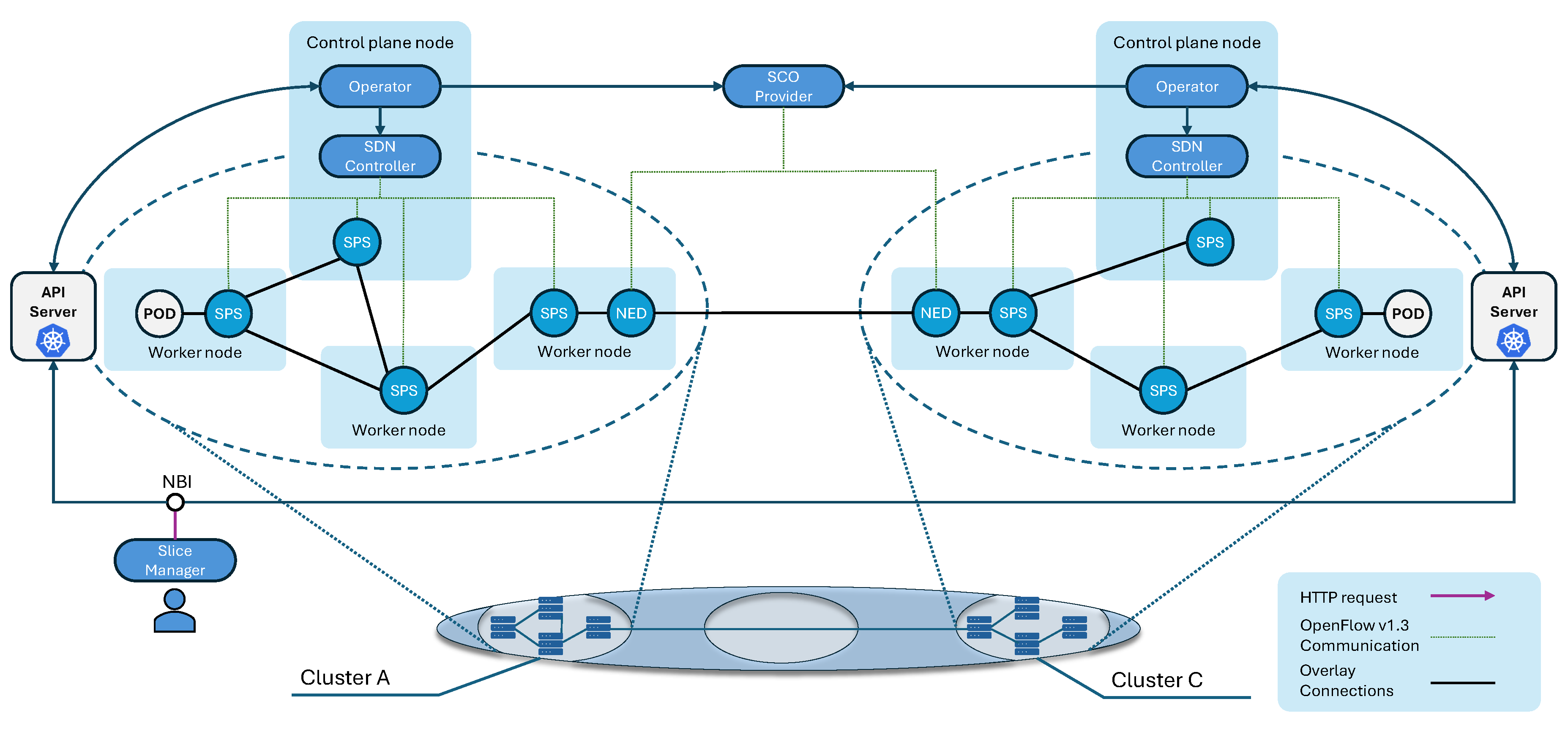

4. Implementation

4.1. Software Components

4.1.1. Operator

4.1.2. SDN Controller

- A unique Network ID for identifying the slice or network instance to be deployed.

- A list of devices (SPSs) and associated OpenFlow identifiers (DPIDs) to be attached.

- A specification of the ports (e.g., OpenFlow port numbers) that each device will use to exchange traffic within the network.

4.1.3. Slice Packet Switches (SPS)

4.1.4. NEDs

4.1.5. SCO Provider

4.1.6. Slice Manager

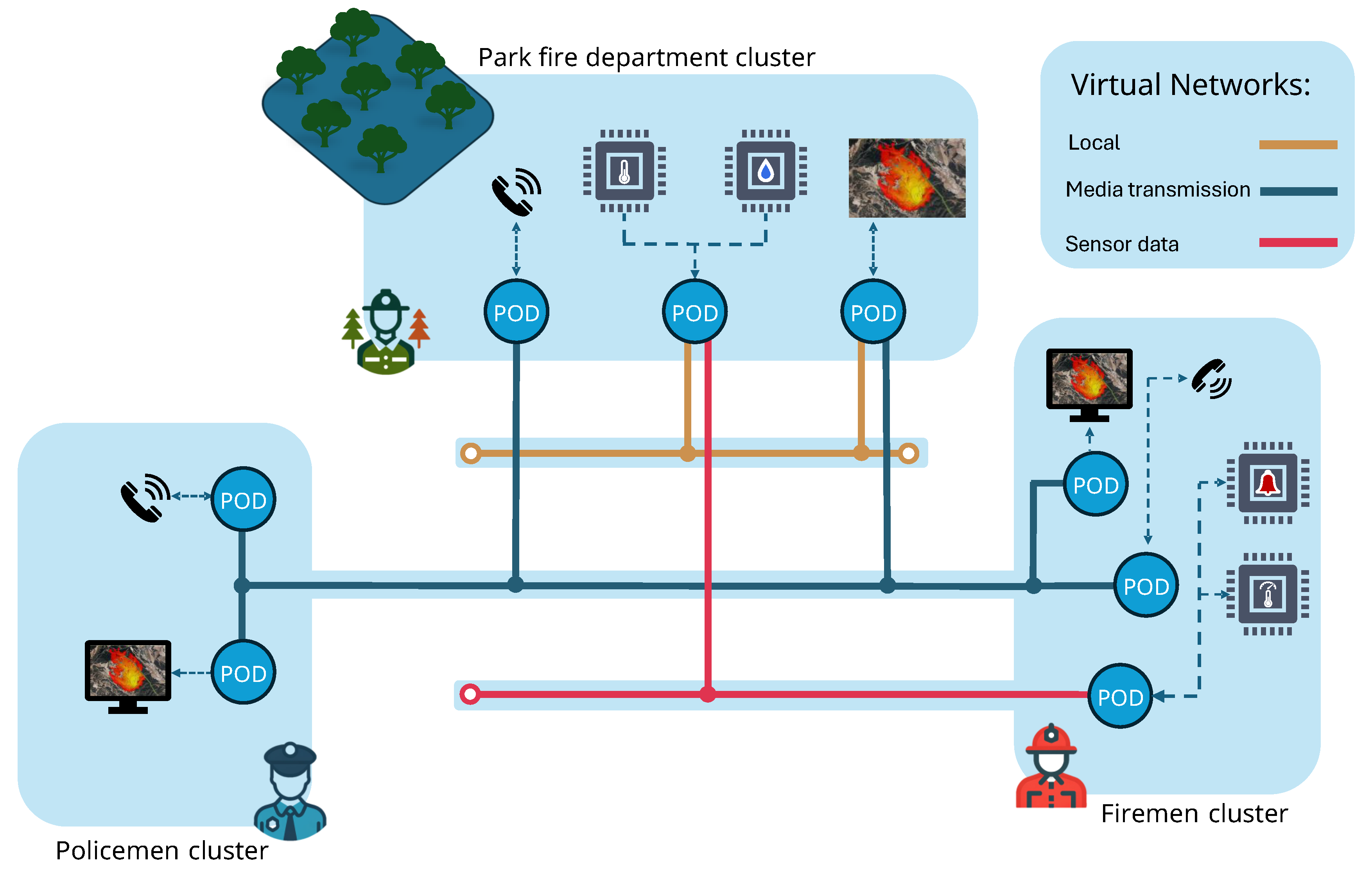

5. Use Case

- A call application using the Session Initiation Protocol (SIP) [43] among the three entities

- An RTP application for streaming real-time video data of the fire status

- A service that delivers sensor data to the firefighters and the private network

- Fire simulation and prevention software in the private network, with outputs shared dynamically

5.1. Hypotheses

- H1: L2S-CES achieves low slice instantiation time.

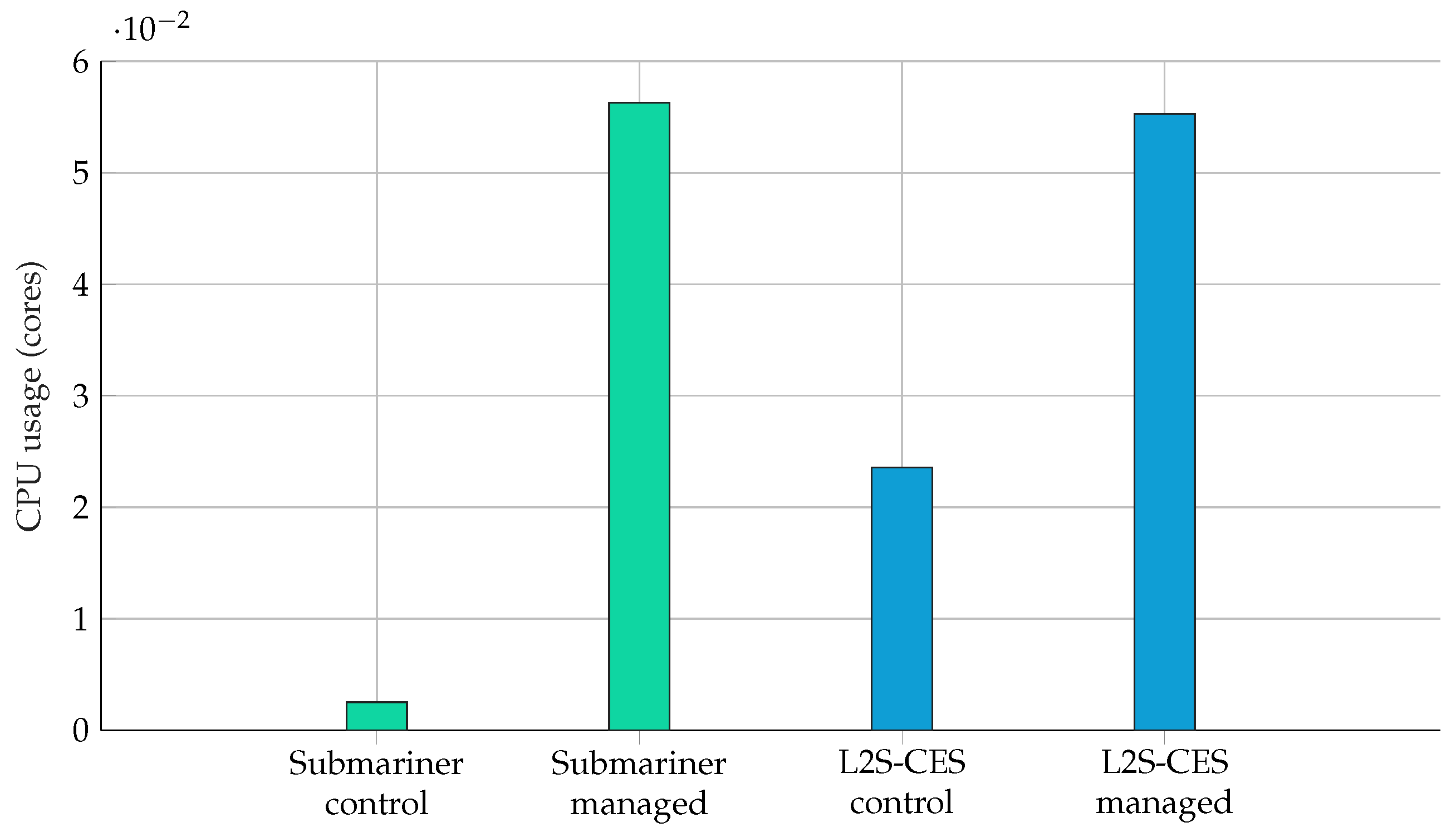

- H2: L2S-CES incurs no greater CPU overhead at steady state.

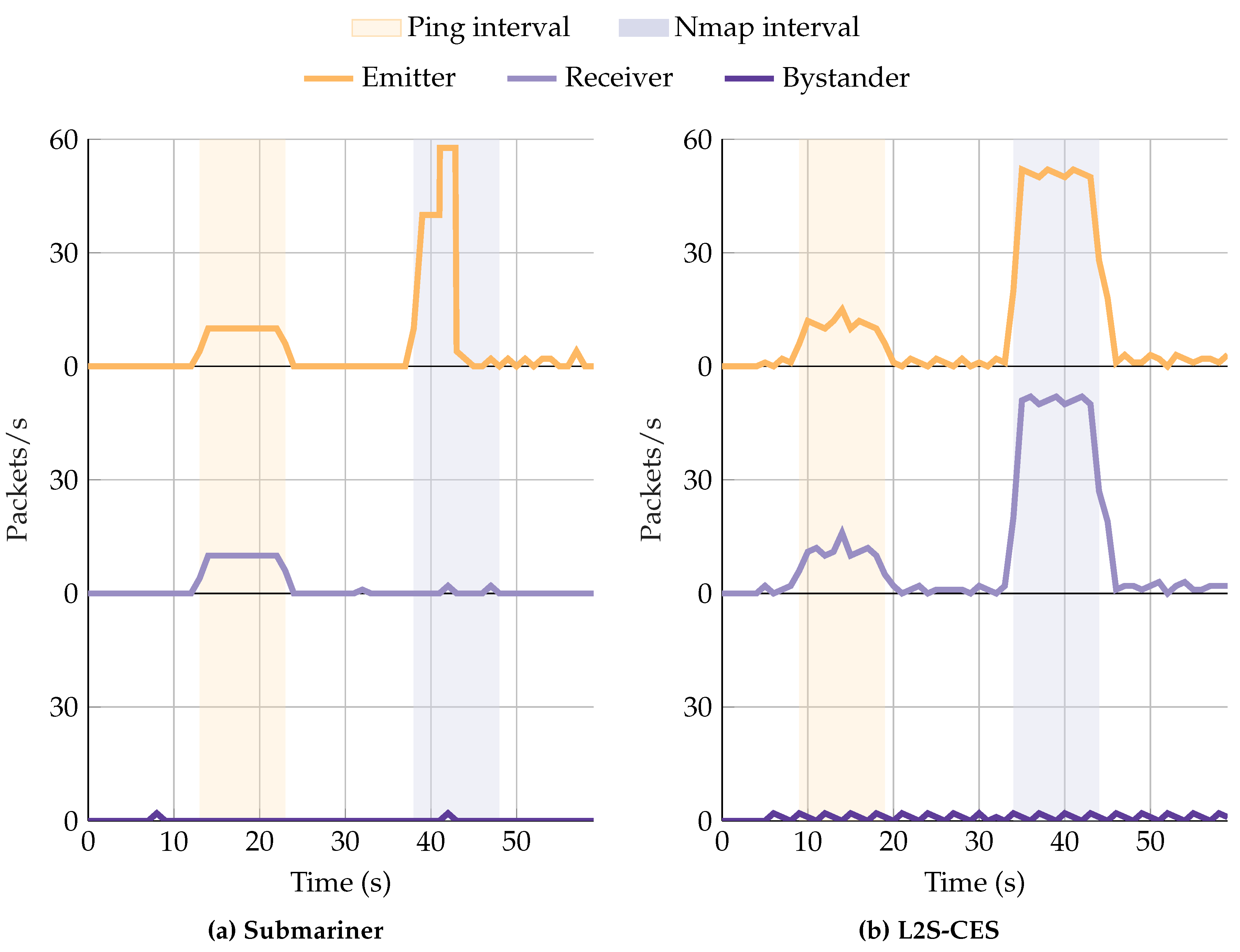

- H3: L2S-CES enforces stronger isolation under active probing.

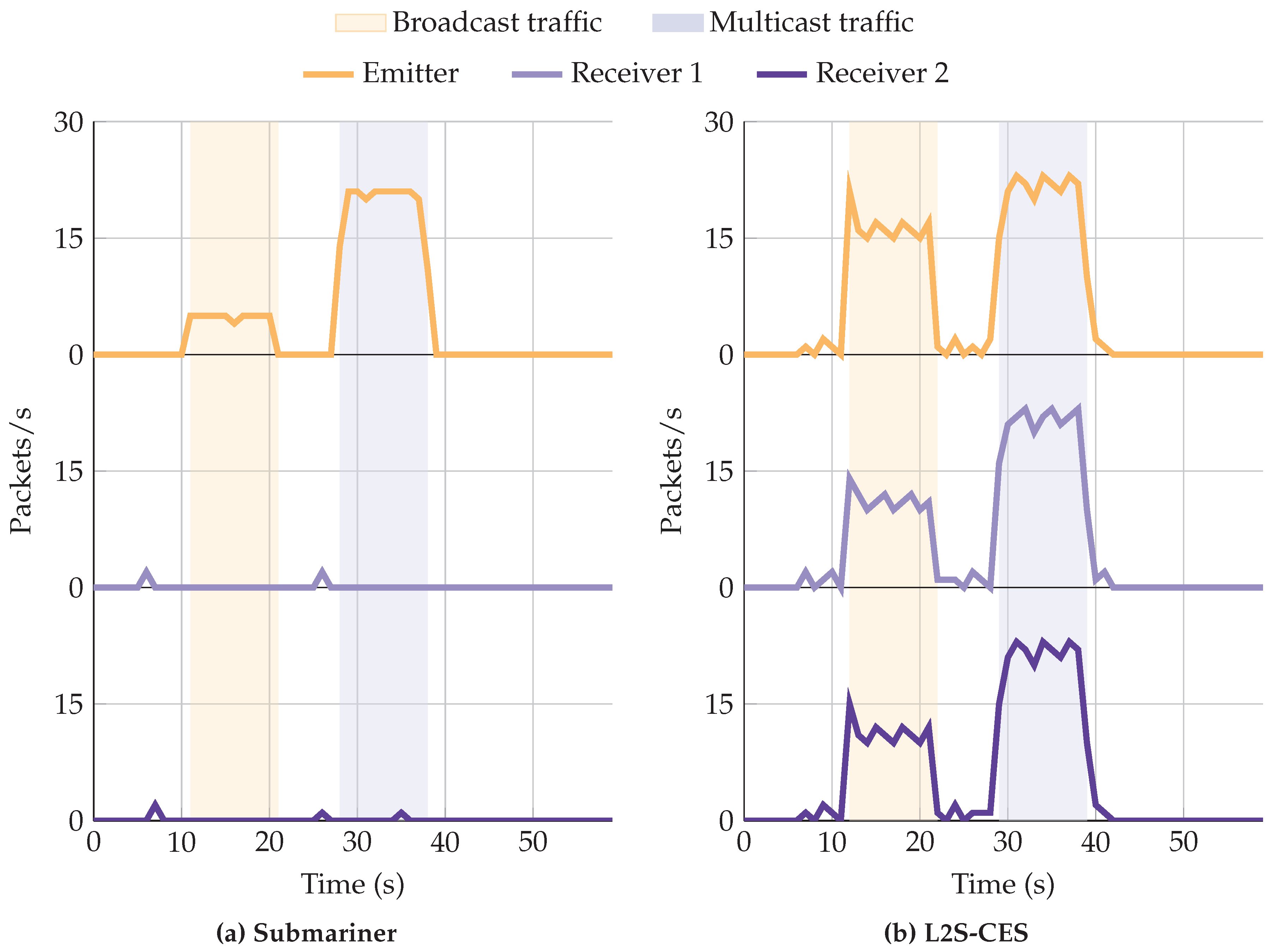

- H4: L2S-CES supports multicast traffic.

5.2. Experimental Setup

5.3. Evaluation and Results

5.3.1. H1—L2S-CES Achieves Low Slice Instantiation Time

5.3.2. H2—L2S-CES Incurs No Greater CPU Overhead at Steady State

5.3.3. H3—L2S-CES Enforces Stronger Isolation Under Active Probing

5.3.4. H4—L2S-CES Supports Multicast Traffic

5.4. Performance Summary

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| CIDR | Classless Inter-Domain Routing |

| CLI | Command-Line Interface |

| CNI | Container Network Interface |

| CRD | Custom Resource Definition |

| DNS | Domain Name System |

| EC2 | Elastic Compute Cloud |

| ECMP | Equal-Cost Multi-Path |

| eBPF | extended Berkeley Packet Filter |

| ETSI | European Telecommunications Standards Institute |

| gRPC | Remote Procedure Call framework |

| IaaS | Infrastructure as a Service |

| IDCO | Inter-Domain Connectivity Controller |

| IPAM | IP Address Management |

| LLDP | Link Layer Discovery Protocol |

| L2S-CES | Link Layer Secure ConnEctivity slicES |

| mTLS | mutual Transport Layer Security |

| NBI | Northbound Interface |

| NED | Network Edge Device |

| NFV | Network Functions Virtualisation |

| OvS | Open vSwitch |

| RTP | Real-time Transport Protocol |

| SCO | Slice Connectivity Orchestrator |

| SDN | Software-Defined Networking |

| SIP | Session Initiation Protocol |

| SPS | Slice Packet Switch |

| TTL | Time To Live |

| UDP | User Datagram Protocol |

| VIM | Virtualized Infrastructure Manager |

| VNF | Virtual Network Function |

| VPN | Virtual Private Network |

References

- Ammar, S.; Lau, C.P.; Shihada, B. An in-depth survey on virtualization technologies in 6G integrated terrestrial and non-terrestrial networks. IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society 2024, 5, 3690–3734.

- SubOptic Spectrum Sharing Working Group. Spectrum Sharing Working Group White Paper. White paper, SubOptic Association, 2021. Accessed: 2025-10-28.

- Bari, M.F.; Boutaba, R.; Esteves, R.; Granville, L.Z.; Podlesny, M.; Rabbani, M.G.; Zhang, Q.; Zhani, M.F. Data center network virtualization: A survey. IEEE communications surveys & tutorials 2012, 15, 909–928.

- Bentaleb, O.; Belloum, A.; Sebaa, A.; El-Maouhab, A. Containerization technologies: taxonomies, applications and challenges. The Journal of Supercomputing 2022, 78. [CrossRef]

- Velepucha, V.; Flores, P. A Survey on Microservices Architecture: Principles, Patterns and Migration Challenges. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 88339–88358. [CrossRef]

- Alshuqayran, N.; Ali, N.; Evans, R. A systematic mapping study in microservice architecture. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 9th international conference on service-oriented computing and applications (SOCA). IEEE, 2016, pp. 44–51.

- Authors, T.K. Kubernetes overview. https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/overview/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Deng, S.; Zhao, H.; Huang, B.; Zhang, C.; Chen, F.; Deng, Y.; Yin, J.; Dustdar, S.; Zomaya, A.Y. Cloud-native computing: A survey from the perspective of services. Proceedings of the IEEE 2024, 112, 12–46.

- McKeown, N. Software-defined Networking. INFOCOM Keynote Talk 2009, 17, 30–32.

- Chiosi, M.; Clarke, D.; Willis, P.; Reid, A.; et al. Network Functions Virtualisation - An Introduction, Benefits, Enablers, Challenges & Call for Action. White paper, 2012. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- NGMN Alliance. Description of Network Slicing Concept. Technical report, Next Generation Mobile Networks (NGMN) Alliance, 2016. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- it uc3m, N. L2S-M: Link-layer secure connectivity for microservice platforms. https://github.com/Networks-it-uc3m/L2S-M, 2023. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Martin, R.; Vidal, I.; Valera, F. A software-defined connectivity service for multi-cluster cloud native applications. Computer Networks 2024, 248, 110479. [CrossRef]

- it uc3m, N. L2S-M MD: L2S-M Multi Domain. https://github.com/Networks-it-uc3m/l2sm-md, 2024. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Peterson, L.; Cascone, C.; Davie, B. Software-defined networks a systems approach; Systems Approach, LLC, 2021.

- OSM, E. WHAT IS OSM? https://osm.etsi.org/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Authors, T.O. Openstack features, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Foundation, T.L. What is ovs?, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Amazon Web Services, I. Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud (EC2) Documentation. https://docs.aws.amazon.com/ec2/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Cloud, G. Compute Engine Documentation. https://cloud.google.com/compute/docs, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Hausenblas, M. Container Networking; O’Reilly Media, Incorporated, 2018.

- .

- Tigera, I. What is Calico. https://docs.tigera.io/calico/latest/about, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Tigera, I. About Calico Enterprise. https://docs.tigera.io/calico-enterprise/latest/about/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Cilium. Cilium Documentation, 2024. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Qi, S.; Kulkarni, S.G.; Ramakrishnan, K. Understanding container network interface plugins: design considerations and performance. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Symposium on Local and Metropolitan Area Networks (LANMAN). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–6.

- Liu, M. Kube-OVN: Bring OpenStack Network Infra into Kubernetes, 2019. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Kube-OVN Project. Cluster Inter-Connection with OVN-IC. https://kubeovn.github.io/docs/v1.13.x/en/advance/with-ovn-ic/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Authors, T.S. Submariner. https://submariner.io/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Li, W.; Lemieux, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhao, Z.; Han, Y. Service mesh: Challenges, state of the art, and future research opportunities. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Service-Oriented System Engineering (SOSE). IEEE, 2019, pp. 122–125.

- Authors, T.I. Istio. https://istio.io/latest/docs/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Buoyant. Linkerd. https://linkerd.io/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Avesha, I. Kubeslice. https://github.com/kubeslice, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Authors, T.N.S.M. Network Service Mesh. https://networkservicemesh.io/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Institute of Internet Technologies and Applications. Advanced Features of Linux strongSwan: the OpenSource VPN Solution, 2005. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Gonzalez, L.F.; Vidal, I.; Valera, F.; Lopez, D.R. Link layer connectivity as a service for ad-hoc microservice platforms. IEEE Network 2022, 36, 10–17.

- Amazon Web Services, I. Amazon Web Services, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- LLC, G. Google Cloud, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Authors, T.K. Kubernetes architecture. https://book.kubebuilder.io/architecture, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Inc., D. Docker docs. https://docs.docker.com/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- it uc3m, N. L2S-M Switch. https://github.com/Networks-it-uc3m/l2sm-switch, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Henning Schulzrinne, Stephen L. Casner, R.F.; Jacobson, V. RTP: A Transport Protocol for Real-Time Applications. Rfc, RFC Editor, 2003.

- Mark Handley, Henning Schulzrinne, E.S.; Rosenberg, J. SIP: Session Initiation Protocol. Rfc, RFC Editor, 1999.

- de Cock Buning, A.T. Architecting Multi-Cluster Layer 2 Connectivity for Cloud Native Network Slicing test repository. https://github.com/Tjaarda1/paper-slices-2025, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Hashicorp. Terraform. https://github.com/hashicorp/terraform, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Hat, R. Ansible. https://github.com/ansible/ansible, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Labs, G. Grafana: The open-source platform for monitoring and observability. https://github.com/grafana/grafana, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- LLC, G. cAdvisor. https://github.com/google/cadvisor, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Authors, P. Node exporter. https://github.com/prometheus/node_exporter, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Lyon, G. nmap: the network mapper. https://github.com/nmap/nmap, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- ETSI. Network Functions Virtualisation - White Paper. White paper, 2012. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Mishra, N.; Pandya, S. Internet of Things Applications, Security Challenges, Attacks, Intrusion Detection, and Future Visions: A Systematic Review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 59353–59377. [CrossRef]

- Nebbione, G.; Calzarossa, M.C. Security of IoT Application Layer Protocols: Challenges and Findings. Future Internet 2020, 12. [CrossRef]

- Ojo, M.; Adami, D.; Giordano, S. A SDN-IoT Architecture with NFV Implementation. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps), 2016, pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Flauzac, O.; González, C.; Hachani, A.; Nolot, F. SDN Based Architecture for IoT and Improvement of the Security. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 29th International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications Workshops, 2015, pp. 688–693. [CrossRef]

- Choo, K.K.R. Editorial: Blockchain in Industrial IoT Applications: Security and Privacy Advances, Challenges, and Opportunities. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2020, 16, 4119–4121. [CrossRef]

- Al Hayajneh, A.; Bhuiyan, M.Z.A.; McAndrew, I. Improving Internet of Things (IoT) Security with Software-Defined Networking (SDN). Computers 2020, 9. [CrossRef]

- Authors, T.K. Kubernetes networking. https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/cluster-administration/networking/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Del Piccolo, V.; Amamou, A.; Haddadou, K.; Pujolle, G. A Survey of Network Isolation Solutions for Multi-Tenant Data Centers. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2016, 18, 2787–2821. [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Tan, J.; Huang, J.; Chen, G.; Wang, S.; Jin, X.; Zeng, P.; Khan, M.; Das, S.K. Edge-computing-driven internet of things: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys 2022, 55, 1–41.

- Zeng, H.; Wang, B.; Deng, W.; Zhang, W. Measurement and Evaluation for Docker Container Networking. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Cyber-Enabled Distributed Computing and Knowledge Discovery (CyberC), 2017, pp. 105–108. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.; Hayashi, T. Tutorial: From CNI Zero to CNI Hero: A Kubernetes Networking Tutorial Using CNI. YouTube Video, 2024. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Feamster, N.; Rexford, J.; Zegura, E. The road to SDN: an intellectual history of programmable networks. SIGCOMM Comput. Commun. Rev. 2014, 44, 87–98. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, B.K.; Pappu, S.I.; Islam, M.J.; Acharjee, U.K. An SDN Based Distributed IoT Network with NFV Implementation for Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the Cyber Security and Computer Science; Bhuiyan, T.; Rahman, M.M.; Ali, M.A., Eds., Cham, 2020; pp. 539–552.

- Krishnan, P.; Jain, K.; Aldweesh, A.; et al. OpenStackDP: a scalable network security framework for SDN-based OpenStack cloud infrastructure. Journal of Cloud Computing 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Ermolenko, D.; Kilicheva, C.; Muthanna, A.; Khakimov, A. Internet of Things services orchestration framework based on Kubernetes and edge computing. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Conference of Russian Young Researchers in Electrical and Electronic Engineering (ElConRus). IEEE, 2021, pp. 12–17.

- Authors, T.K. Kubernetes Multitenancy. https://kubernetes.io/docs/concepts/security/multi-tenancy/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Labs, R. Kubernetes Lightweight. https://k3s.io/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Authors, T.K. Creating a cluster with kubeadm. https://kubernetes.io/docs/setup/production-environment/tools/kubeadm/create-cluster-kubeadm/. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Fortinet. Openstack fortinet. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- of the University of California, T.R. iperf: A TCP, UDP, and SCTP network bandwidth measurement tool. https://github.com/esnet/iperf, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- cert-manager Authors, T. Cloud native certificate management. https://cert-manager.io/, 2025. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- it uc3m, N. LPM: L2S-M Performance Measurements. https://github.com/Networks-it-uc3m/LPM, 2023. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- K8snetworkplumbingwg. multus-cni: A CNI plugin to allow Kubernetes to attach multiple network interfaces to pods. https://github.com/k8snetworkplumbingwg/multus-cni, 2023. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Fokus, F. Open Baton: an open source reference implementation of the ETSI Network Function Virtualization MANO specification, 2025.

- golang standards. Standard Go Project Layout. https://github.com/golang-standards/project-layout, 2023. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

- Tigera, I. How Calico enables a Kubernetes cluster mesh for security, observability, and networking in multi-cluster environments. White Paper, 2022. Accessed: 2025-10-30.

| Cluster | Nodes | Control plane components |

Per-node components |

Gateway-node components |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| l2sces-control | 1 | l2sces-client, sco-provider, l2sces-dns | — | — |

| l2sces-managed-1 | 3 | L2S-CES Operator, SDN controller | SPS per node | NED on 1 worker |

| l2sces-managed-2 | 3 | L2S-CES Operator, SDN controller | SPS per node | NED on 1 worker |

| sub-control | 1 | Submariner broker | — | — |

| sub-managed-1 | 3 | Lighthouse, Globalnet, Submariner operator | Route agent per node | Submariner gateway on 1 worker |

| sub-managed-2 | 3 | Lighthouse, Globalnet, Submariner operator | Route agent per node | Submariner gateway on 1 worker |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).