1. Introduction

Cloud computing has brought a major paradigm shift to the IT landscape [

1] and enabled the creation of large compute continuums. These continuums are often utilized for a variety of tasks [

2] including compute-intensive workloads as well as providing web services and are commonly operated through Kubernetes [

3]. While Kubernetes is capable of effectively scheduling container workloads, taking into account various constraints and policies [

4], the cloud landscape grows more and more complex through the addition of heterogeneous components such as Internet of Things (IoT) devices [

5].

Kubernetes scheduling is an ongoing area of research [

4,

6,

7] with different approaches focusing on metrics such as reliability, energy consumption, and resource utilization. However, scheduling becomes increasingly difficult when including heterogeneous components, which can be edge devices, data centers using heterogeneous hardware, or outdated hardware being replaced by newer components [

8].

Researchers working on scheduling algorithms for heterogeneous compute clusters may be unable to properly evaluate their work as access to heterogeneous components may be limited. Heterogeneous components include, often expensive, specialized hardware or IoT devices, which may be reserved by other users or not available at all. Moreover, available heterogeneous components may already be installed in production systems and a newly developed scheduling algorithm cannot be deployed in production without being evaluated first, however, for the evaluation the heterogeneous components would need to be moved into a test system and be missing from production.

One such research effort is the DECICE project [

9], which aims to develop an AI-based scheduler for Kubernetes that is suitable for heterogeneous Kubernetes clusters. To train machine learning models and to test frameworks, one or more heterogeneous Kubernetes clusters are required. As a possible solution we considered simulations such as CloudSim [

10], its extensions [

11,

12], EMUSIM [

13] and K8sSim [

14], however, we found the grade of detail available, especially for heterogeneous hardware, insufficient for our work. Instead we investigated virtualization techniques to emulate a heterogeneous Kubernetes cluster consisting of nodes with different emulated hardware architectures and operating systems on existing homogeneous OpenStack cloud infrastructure.

As the result of this we present Q8S, which allows users to automatically set up a Kubernetes cluster with heterogeneous nodes running on a homogeneous OpenStack cloud using QEMU [

15]. Q8S offers a greater level of detail than simulations and has been benchmarked using k8s-bench-suite [

16], showing that the emulated clusters work without significant changes in communication bandwidth, although CPU performance suffers from emulation overhead. Our Q8S implementation is open source and can be extended to further utilize the emulation capacities of QEMU and libvirt [

17]. The source code available at

https://github.com/gwdg/pub-2025-Q8S under the MIT license.

1.1. Background

Q8S depends on a complex stack of technologies including nested virtualization, hardware emulation and manipulation of Linux iptables. The following paragraphs explain these technologies as they are relevant for understanding the design of Q8S.

System Heterogeneity

For heterogeneous systems we derive our definition from [

18] such that a system is homogeneous if hardware, configuration, resources and operating systems are the same. Therefore, a node would be heterogeneous if it deviates in any of these areas.

Differences in hardware may be different CPU architectures such as x86 and ARM but can also be different CPUs of the same architecture, varying amounts of installed system memory or network cabling. Moreover, some nodes might include additional hardware components such as GPUs. All these differences lead to variations in the resources that a given node can contribute to a heterogeneous cluster.

Based on deployed operating systems and configurations as well as hardware variations, a given workload may perform better or worse on a specific node or even be incompatible. For a scheduler to determine the optimal placement may be NP-complete [

9]. In order to find near-optimal placements on a heterogeneous cluster all these factors should be considered.

Nested Virtualization

Virtualization includes operating a Hypervisor or Virtual Machine Manager (VMM) on a node that in turn controls one or more virtual machines (VMs) [

19]. The hypervisor has to handle the virtualization of CPU and memory as well as any Input/Output (IO) devices including disks and networking [

20], which results in additional overhead for operations carried out in a VM due to the VMM having to perform translations between the VM and the hardware. Optimization techniques such as para-virtualization exist [

21], which often require a VM to be aware that it is running on top of a hypervisor such that it can utilize hypercalls, requests directly going to the hypervisor without translation.

In nested virtualization, a VM is run within another VM by layering hypervisors [

22]. This creates a hierarchy of hypervisors with the outermost hypervisor operating on the actual hardware and hardware interactions from a VM running on an inner hypervisor are passed from inner hypervisor to outer hypervisor. For the inner hypervisor to work properly, certain operations that it would expect to be carried out directly on the underlying hardware, need to be trapped and emulated by the outer hypervisor. Due to the multiple layers of hypervisors, nested virtualization further adds to the performance overhead of virtualization.

Flannel and VXLAN

Flannel is a lightweight networking plugin for Kubernetes with decent performance [

23,

24]. It operates via a Layer 3 IPv4 network and routes packages based on target IP addresses to the respective ports of the Kubernetes containers. Its recommended backend is Virtual Extensible LAN (VXLAN), a networking virtualization, which employs encapsulation of Ethernet traffic to construct Layer 2, data link Layer, connections via Layer 3 networks. For inter-node communication, Flannel sets up a VXLAN Tunnel Endpoint (VTEP) that enables any two nodes to communicate on Layer 2 by sending UDP packages, which encapsulate a VXLAN header. The inter-node traffic uses Layer 3 IP addresses while node internal addressing happens on Layer 2 using MAC addresses.

Linux Firewall

Networking packages are processed by the Linux kernel based on routing tables and iptables in order to determine where a given package should be sent. If a package is not addressed to the local IP, its next hop is determined by the routing tables while iptables serve to apply further operations on incoming packages. These operations include filtering, network address translation (NAT) and package manipulation (mangle) applied at varying stages of package processing such as at arrival (prerouting), receiving locally (input), forwarding (forward) and before sending (postrouting) as well as for any locally created packages (output).

Simulation and Emulation

The behavior of a system can be replicated using emulation or simulation. The two techniques form distinct approaches with simulation utilizing a model to resemble a given system and its behavior through mathematical or logical abstractions [

25]. Emulation on the other hand attempts to replicate the exact behavior of the target system through mimicking its hardware and software environment.

Simulations can be highly flexibly but due to abstracting the actual system into a model, accuracy may be reduced. In emulations, the target system components are mimicked as close as possible, resulting in high accuracy at the cost of reduced flexibility and higher computational cost.

QEMU and Libvirt

Quick EMUlator (QEMU) is a generic open source emulator with support for a large range of hardware platforms and architectures such that a developer can test their software against multiple platforms without actual access to the hardware. QEMU can operate as an inner hypervisor to emulate a VM with a specified hardware configuration, for example, ARM, on top of an x86 node. However, when doing so, hardware acceleration features that would reduce the performance overhead of the virtualization, are not available as the hardware emulated in the VM and of the physical host have to be identical for hardware acceleration.

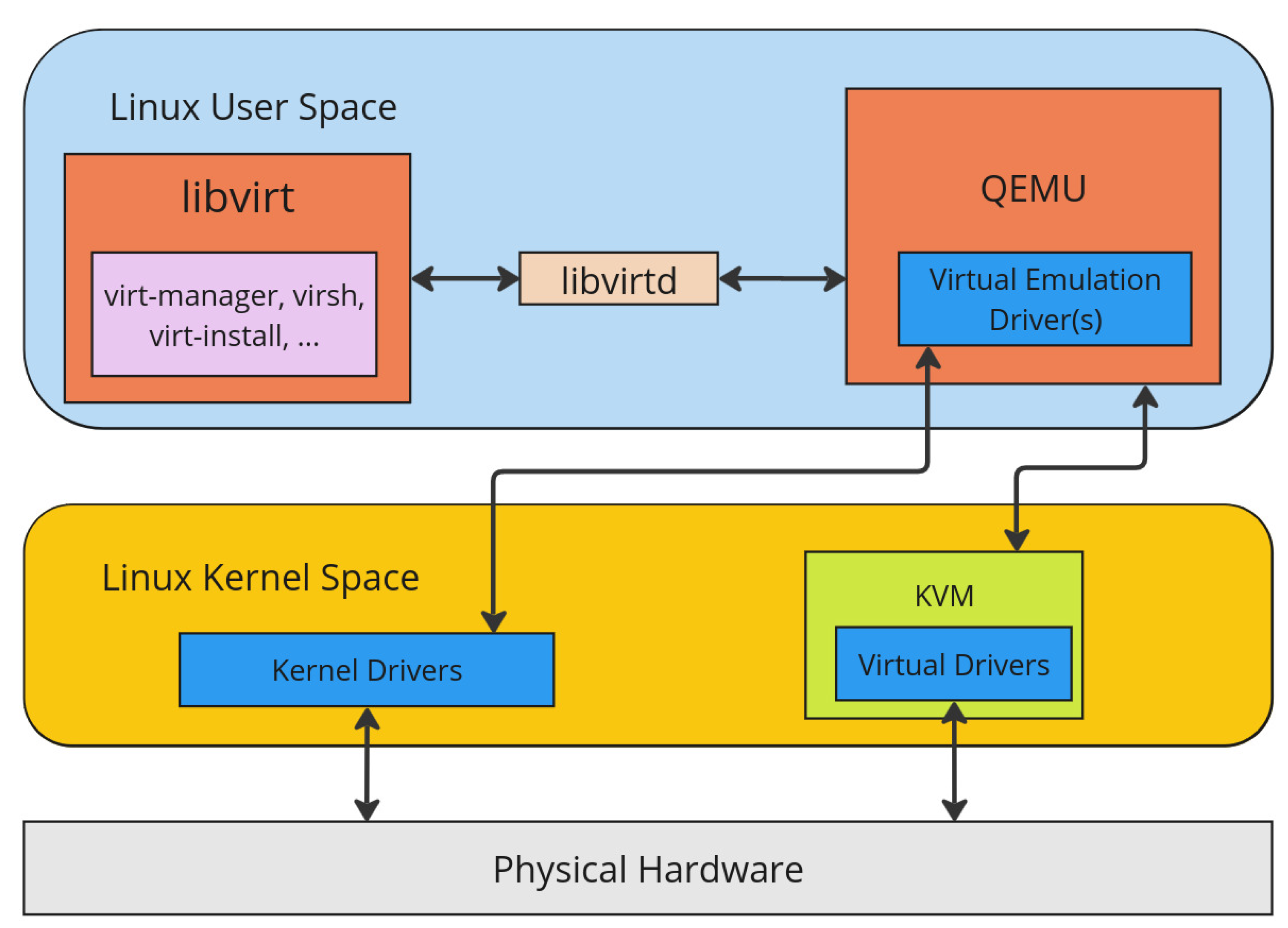

Libvirt provides an API, daemon and management tools for working with QEMU and other virtualization systems including command line tools

Virsh and

Virt-install. The interaction of libvirt and QEMU is shown in

Figure 1 with libvirt providing its tools in user space such that QEMU can be managed to create the requested VMs while interacting with the underlying system kernel. It should be noted that in

Figure 1, QEMU would be the only hypervisor and directly work with the hypervisor KVM to create VMs. For QEMU to be an inner hypervisor, the physical hardware would be an emulation of the outer hypervisor and KVM would not be used.

Ubuntu Cloud-Images and Cloud-Init

Ubuntu Cloud-Images are Ubuntu OS images that include a feature called cloud-init, which can be configured to apply settings and execute scripts on a fresh image during the first boot. These configurations consist of multiple parts including user-data and meta-data files. User-data contains user creation settings, ssh configurations as well as the packages to install and scripts to run. The meta-data file can add additional network configuration and set the hostname.

1.2. Related Work

CloudSim [

10] is an open source engine for simulating cloud computing environments. In CloudSim a data center may operate a number of hosts, which each run one or more VMs and tasks are executed in VMs. The compute capabilities of hosts can be specified in core numbers and MIPS per core as well as memory, bandwidth and storage. The simulation can then calculate for a set of tasks, which each require a number of compute instructions as well as memory and access to storage, what tasks would end up on which nodes and how long the execution of all tasks would take. CloudSim is an event based simulation and does not emulate any hardware. Moreover, heterogeneity of hosts is limited to CPU counts, speed, memory and storage size and bandwidth but does not include different system architectures.

DynamicCloudSim [

11] and Cloud2Sim [

12] provide further developments on top of CloudSim. DynamicCloudSim introduces performance variance through sampling CPU, IO and bandwidth speed from a normal distribution instead of using a static value. Cloud2Sim adds the option to run distributed simulations to CloudSim as CloudSim itself can only execute on a single host, which results in long compute times for large simulations.

EMUSIM [

13] is another extension of CloudSim, which utilizes emulated hardware to run applications to improve the accuracy of a simulation. By running the target application in a small scale emulated environment with varying input sizes, EMUSIM is able to collect metrics regarding the scalability of the application. These metrics are then used in CloudSim to perform a more detailed simulation. The same limitations for the support of heterogeneous clusters apply as for CloudSim.

K8sSim [

14] is a tool similar to CloudSim, which is capable of simulating Kubernetes clusters including specifying CPU capacity, memory and GPU count per node. Workloads can be configured with specific requirements and be scheduled with customizable scheduling algorithms. The simulation collects data on total execution time and wait times for workloads, which serve to evaluate a given scheduling algorithm. This can serve as a starting point for validating a new scheduling algorithm, however, it does not properly support heterogeneous clusters as it does not run any workloads or performs hardware emulation.

1.3. Contributions

This paper contributes the design, implementation and evaluation of a Q8S prototype with the following features:

Automatic deployment of a heterogeneous Kubernetes cluster on a homogeneous OpenStack cloud including nodes with emulated hardware via QEMU.

Configurable settings to specify the hardware to emulate as well as how many nodes should be deployed for a given specification.

Open source access to the Q8S Python code and Bash scripts, enabling extensibility to include additional features of QEMU and libvirt.

By utilizing Q8S, researchers can deploy emulated heterogeneous Kubernetes clusters to test, evaluate and train AI schedulers for heterogeneous environments without actual access to such hardware. The content of this paper is based on the master’s thesis of one of the authors [

26].

1.4. Outline

The rest of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents the design of Q8S as well as our methods for validating it.

Section 3 discusses the implementation details of Q8S and the results of our validation.

Section 4 covers limitations and implications of Q8S.

Section 5 summarizes our efforts and describes future work.

2. Materials and Methods

The goal of Q8S is to provide a tool for researchers and developers to test code, evaluate algorithms and train machine learning models on a heterogeneous Kubernetes cluster running on emulated hardware. Users of Q8S should be able to specify what hardware should be emulated and how many nodes should be deployed. Given all configurations, Q8S should be able to request the required nodes in an OpenStack environment, set up the emulation software and deploy Kubernetes such that users can start using the cluster as soon as Q8S is done.

We capture these goals as the following functional requirements:

- FR1

Required resources are requested from an existing OpenStack environment.

- FR2

-

The specifications of a node type on the to be emulated cluster can be set by the user, including:

- FR2.1

System architecture, e.g., x86 or ARM

- FR2.2

CPU speed and number

- FR2.3

Memory size

- FR2.4

Storage Size

- FR3

The user can specify the number of nodes per type.

- FR4

The hardware of every worker node is emulated. This also includes any nodes that might run the same architecture as the host system.

- FR5

After successful completion of Q8S, the user is provided with a working Kubernetes cluster, which meets the provided specifications and can execute real workloads.

- FR6

No additional privileges beyond regular user permission in the existing OpenStack environment are required.

Some components of a hetereogneous Kubernetes cluster might be installed outside of a data center, for example, IoT devices collecting or presenting data close to the user. The connectivity to such devices may be limited or even unstable, requiring specialized scheduling and autonomous actions from such nodes. Therefore, we consider the support for network bandwidth and latency as well as simulating failures in network connectivity as relevant features for an extensive emulation of a heterogeneous Kubernetes cluster. However, support for bandwidth, latency and network failures are not included in the version of Q8S presented here but will be added in a future release.

2.1. Q8S Design

Here we present and discuss the design considerations when creating Q8S. The problem of providing a tool for creating heterogeneous Kubernetes clusters on top of OpenStack can be split into three layers:

User interface

OpenStack instances

QEMU VMs

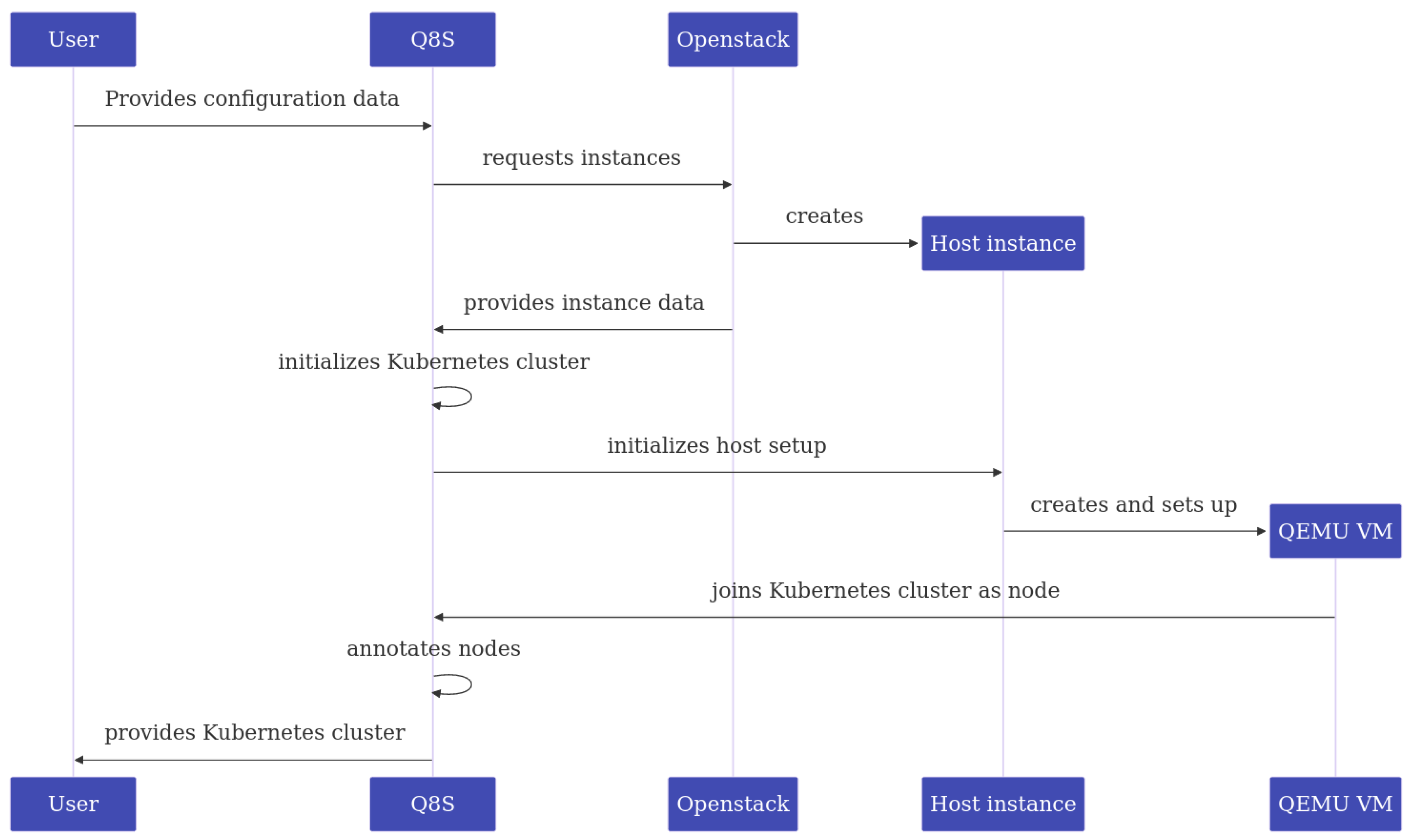

These layers are also partially reflected in

Figure 2 a sequence diagram depicting the workflow of Q8S.

As the user interface, Q8S provides a CLI tool, which reads from a YAML file. The user can specify the desired cluster by creating said YAML file as a human and machine readable record of the to be created cluster. Moreover the user is expected to provide credentials for OpenStack such that Q8S can request resources in the name of the user. This operation is reflected in the first step shown in fig:seq.

The next layer involves Q8S using the provided credentials to request instances via the OpenStack API. Each OpenStack VM serves as the host for a single Kubernetes node, which may be deployed directly on the host or as a nested VM via QEMU. Kubernetes nodes hosting control plane components are deployed without emulation while all worker nodes use QEMU VMs as emulated environments. The provisioning of the OpenStack VMs is depicted in the next three steps in fig:seq.

We considered operating multiple emulated Kubernetes worker from a single OpenStack VM by having QEMU run multiple VMs but decided on a one node per host solution to not add additional complexity to the network configuration.

The last layer consists of setting up the Kubernetes cluster, the QEMU VMs and joining the cluster together. When initializing the cluster, Q8S uses the node it is running on as the initial Kubernetes control plane member that generates the Kubernetes certificates and administrator configurations.

On all other control plane nodes, Q8S installs Kubernetes and joins it to the already initialized cluster. On the worker nodes, Q8S installs QEMU and libvirt and is then ready to fetch the OS images used for the respective emulated environments.

We considered multiple approaches for providing the OS images:

-

VM Snapshots

This approach involved preparing a VM with all the required dependencies and saving it as a snapshot, which is then provided to the QEMU hosts. However, we wanted Q8S to be flexible and this approach would require recreating said snapshots for every update to the images for every specified node type.

-

Autoinstall for Ubuntu Server

Ubuntu server has a feature to automatically set up a system when given an autoinstall configuration. We explored this option and it worked for our x86 images but we encountered problems for our ARM images.

-

Ubuntu Cloud-Images

Besides Ubuntu server images, Canonical also provides Ubuntu Cloud-Images, which are lightweight for Ubuntu OS images with around 600 MB and can be configured via cloud-init settings. Cloud-Images are available for different system architectures including x86 and ARM while utilizing identical setup instructions. While this decision locked Q8S into only supporting Ubuntu based hosts, we consider this a reasonable trade-off compared to specifying setup instructions for various Linux distributions.

Q8S provides the cloud-init settings to the QEMU hosts such that the Cloud-Images can be set up in the emulated environments.

Another major aspect of the design of Q8S is networking. Each machine is in two different networks, the Openstack provided network that connects all hosts and the local network for each host, which is generated by libvirt. For the Kubernetes cluster to properly work, each of the local networks needs to be connected to the inter-node network such that requests can be routed between the QEMU VMs while supporting the Kubernetes internal networking.

Besides opening the required ports in the OpenStack security groups, we configured Flannel to use the host’s network interfaces instead of the QEMU VM’s interfaces for VTEP by annotating the nodes with the respective public-ip setting for Flannel. Moreover, we set up NAT rules in iptables to route packets received by the host to the QEMU VM IP. This required both Source NAT (SNAT) and Destination NAT (DNAT) rules.

2.2. Design Validation

In order to evaluate Q8S, the functional requirements need to be checked. Furthermore, to understand the overheads introduced by the emulation layer, we employ k8s-bench-suite [

16] version 1.5.0 to measure network communication, CPU usage and RAM usage.

Specifically we measured pod-to-pod and pod-to-service communication throughput and latency as well as CPU and memory usage while the benchmark ran. All measurements were done using k8s-bench-suite except for latency, which was measured with the ping command.

To establish a baseline, the experiment was run with emulated worker nodes and worker nodes running directly on the OpenStack hosts. To ensure that the results are comparable, we configured QEMU to emulate the same CPU as was installed in the OpenStack nodes. In our OpenStack environment this was the AMD EPYC Processor with BPB. Moreover, to ensure that both the emulated node and the OpenStack node had the same amount of resources available, we set the QEMU VM to only use 2 CPUs and 2 GB RAM on host nodes with 8 CPUs and 8 GB RAM, while setting the OpenStack nodes to a flavor with 2 CPUs and 2 GB RAM.

3. Results

Based on the design discussed in the previous section we implemented Q8S. The resulting source code is available at

https://github.com/gwdg/pub-2025-Q8S. The prototype is implemented in Python 3.10 and was verified using Kubernetes version 1.28.0 and Flannel version 0.25.6 on Ubuntu 22.04.4 nodes, which were stable releases at the time of the experimental validation.

3.1. Implementation

In the following we discuss the implementation details of our Q8S prototype with examples taken from our OpenStack environment.

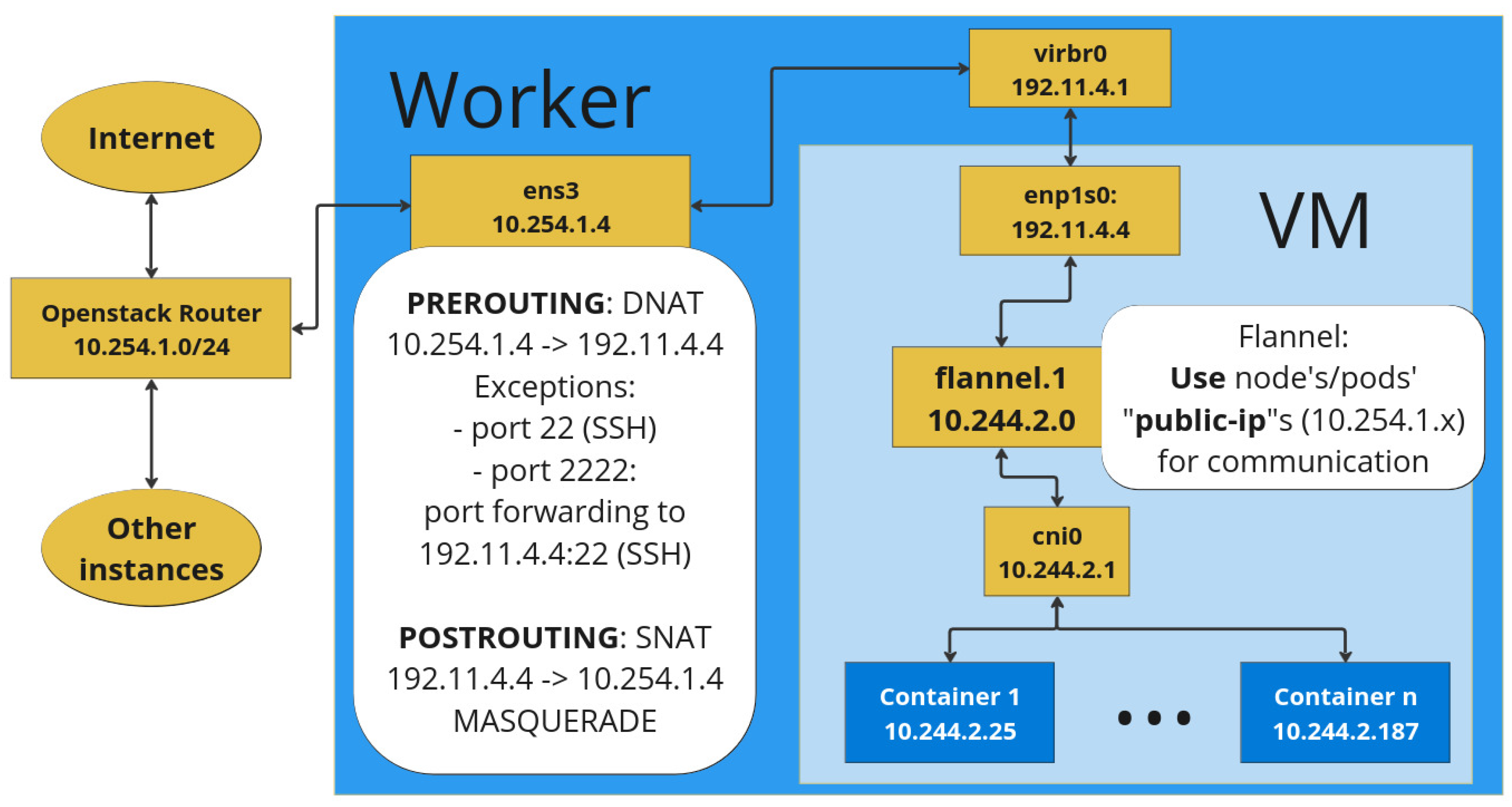

Networking

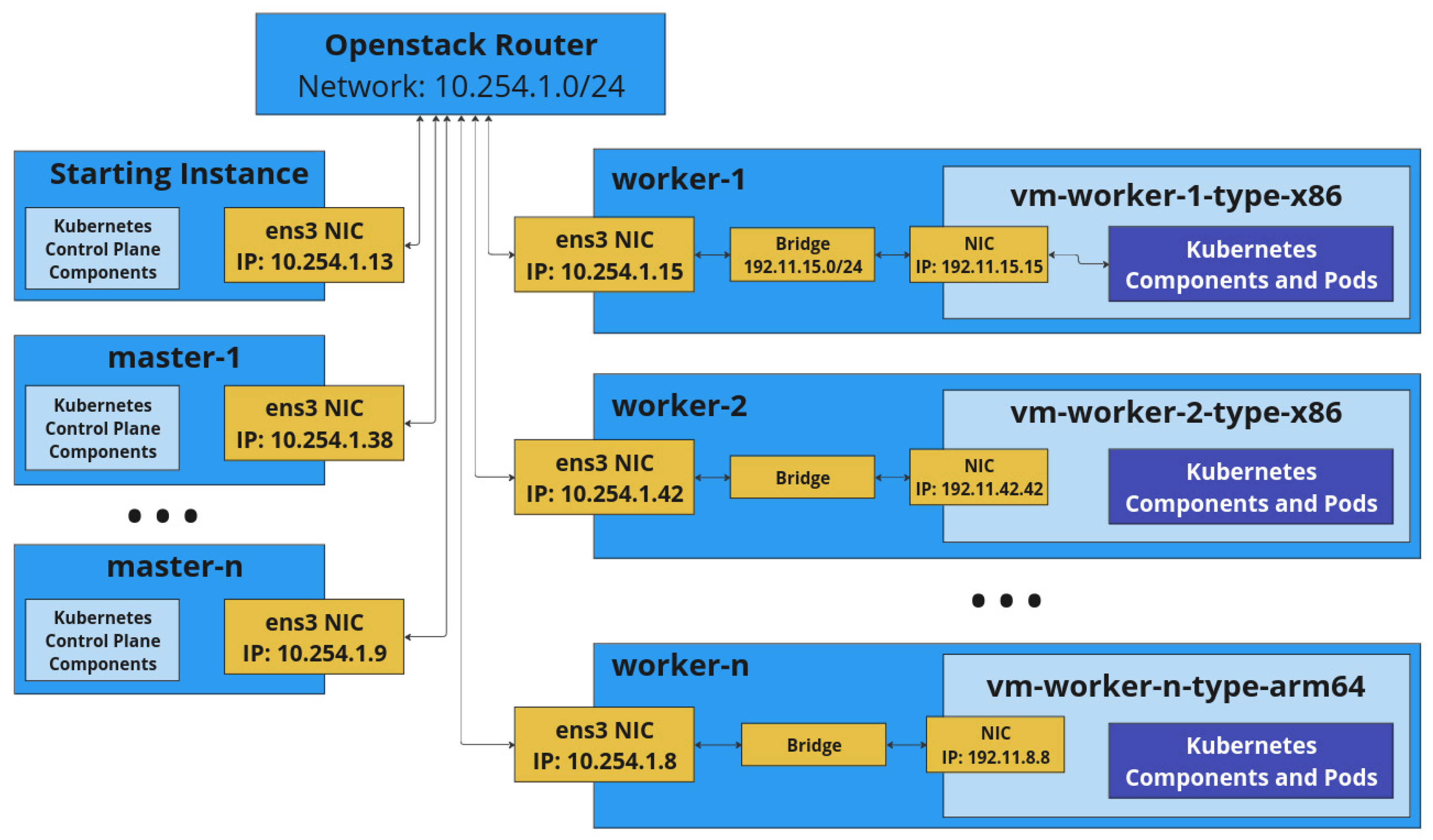

Depending on the configuration of a given OpenStack cloud, the default network masks may vary. In our OpenStack environment, all hosts are part of the 10.254.1.0/24 network range and the QEMU VMs used 192.11.3.0/24. When assigning the IPs of the QEMU VM, we configured Q8S to automatically match the host IP, e.g., the host with 10.254.1.3 would internally run 192.11.3.3. This also ensures that the QEMU VM IPs are unique across both networks.

Figure 3 provides an overview of a cluster created by Q8S with the 10.254.1.0/24 IP range used for the hosts. The name of the default network interface of the hosts in the OpenStack network is

ens3 but may be different in other OpenStack clouds.

The starting instance in the top left of

Figure 3 is the node on which the user has started Q8S and which initialized the cluster as its first control plane node. Below that are the other control plane nodes, which do not install an additional virtualization layer. On the right are workers depicted numbered from 1 to n. It should be noted that in

Figure 3, there are two worker types, x86 and arm64.

The worker nodes deploy QEMU and connect the internal network of it via a bridge to the host network. From the perspective of the other nodes, the additional virtualization layer provided by QEMU is not visible on the network layer as any requests send to a worker node get forwarded by the iptables rules to the internal VM via NAT.

The internal networking of a worker host are depicted in detail in

Figure 4 with the left white box listing out the iptables rules. These include prerouting DNAT rules to forward any traffic send to the host to the QEMU VM on the same port. The exception is port 22 of the host, which still provides regular SSH access to the host node and port 2222, which is redirected to port 22 of the QEMU VM for SSH access. For outgoing traffic SNAT is used to masquerade requests as the host node.

The right half of

Figure 4 shows the network bridge provided by libvirt labelled as

virbr0, which connects the host and QEMU VM networks. Inside the QEMU VM is the

enp1s0 interface, which holds the IP of the overall QEMU VM. Inside the VM is the local network created by Flannel, which is used to assign IPs to the individual containers. Flannel is shown in

Figure 4 to use the node’s public-ip for inter-node communication, which is necessary for it to accept the requests forwarded via the iptables rules.

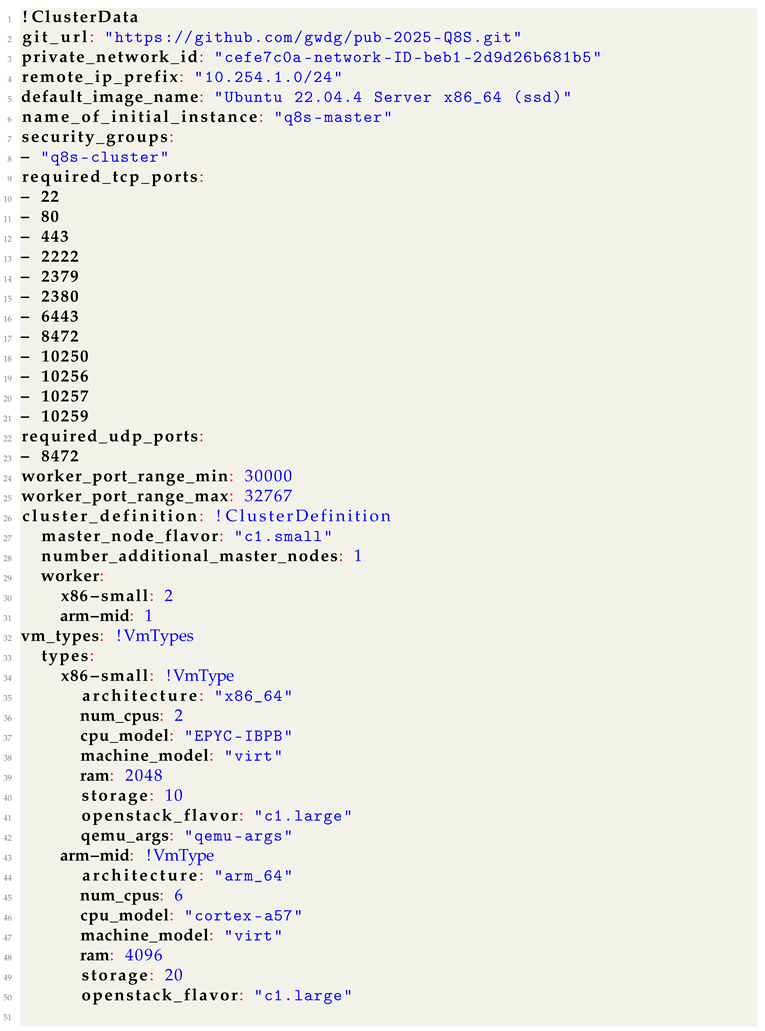

Configuration

Q8S requires two configuration files to get started, the YAML cluster configuration file and a file with credentials for the OpenStack cloud. The official Python OpenStack SDK used by Q8S is able to process clouds.yaml files, which can be downloaded through the OpenStack Horizon web interface under application credentials. With these application credentials, Q8S is able to query the OpenStack API for the OpenStack project for which the credentials were created.

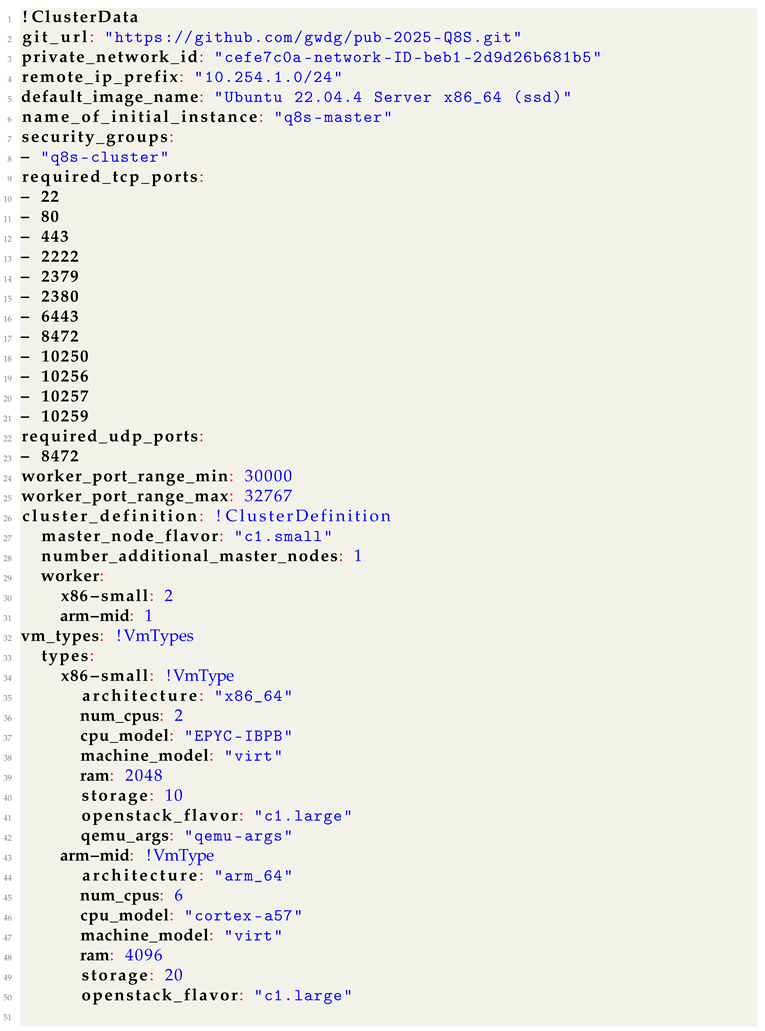

The cluster configuration file includes the user provided settings for the to be created cluster. An example for such a file is given in

Listing A1. The configuration includes the following fields, which the user is expected to adjust to their needs:

git_url: A URL pointing to a Q8S git repository, which is either public or accessible via embedded access tokens. This is required for the later installation stages to download the respective setup scripts on the new nodes.

private_network_id: The id of the internal network in which all hosts reside and can be found in the OpenStack Horizon web interface under networks as the id of the private subnet. This is required for requesting new VMs via the OpenStack API.

remote_ip_prefix: The IP mask of the OpenStack network. In our environment this is 10.254.1.0/24.

default_image_name: The name of the OS image that should be used for the OpenStack images. Q8S expects this to be an Ubuntu image.

name_of_initial_instance: The name of the starting instance in OpenStack. This is required for updating its security groups.

security_groups: The list of OpenStack security groups that should be added to each node. This list has to at least contain q8s-cluster, which is the group configured for internal communication of the Kubernetes cluster.

required_tcp_ports: The list of TCP ports that should be opened in the q8s-cluster security group for inter-node communication. The list given in the example in clusterYAML should be kept but further ports may be added.

required_udp_ports: The same as for TCP ports above but for UDP.

worker_port_range_min: This is the lower end of the port range that is to be opened in addition to the TCP ports specified above and used for Kubernetes container node ports.

worker_port_range_max: The high end for the port range as specified above.

master_node_flavor: Flavor to be used by additional control plane nodes. The flavor in OpenStack specifies the amount of CPUs and system memory OpenStack should allocate from a project quota to a specific VM.

number_additional_master_nodes: The number of control plane nodes that Q8S should deploy in addition to the starting instance. The control plane IP is always set to the IP of the node running Q8S and does not deploy fail over mechanisms. Therefore, even if the created cluster includes multiple control plane nodes, it is not a high-availability (HA) deployment.

worker: The vm_types specified in the next section can be used here to indicate how many instances of a given type should be deployed by Q8S.

The vm_types a user wishes to use should be each specified as a dictionary with the following fields:

architecture: System architecture of the emulated CPU. Our Q8S prototype supports x86_64 and arm_64.

num_cpus: The number of emulated CPUs that should be available in the QEMU VM.

cpu_model: Specific CPU model that should be emulated by QEMU, which also determines the available CPU speed. The list of supported CPU models depends on QEMU and can be found in its documentation.

machine_model: Machine model requested through QEMU. This should be kept as virt.

ram: The amount of system memory to allocate for the QEMU VM in MB.

storage: Amount of storage to allocate for the QEMU VM in GB.

openstack_flavor: Flavor to use in OpenStack for the host. The flavor should include at least if not more CPUs than the emulated node.

Deployment Process

fig:seq gives a high level overview of the Q8S workflow and the interactions between the components. To provide a more detailed insight to the involved steps for Q8S, the following presents the concrete operations that are executed in order:

Creation of the security group q8s-cluster if it does not exist and the configuration of the rules as specified in the settings file.

Creation of an SSH key pair, which is uploaded to OpenStack such that the new VMs get initialized with it and can later on be accessed.

Creation of the OpenStack VMs via its API for the control plane and worker nodes.

Waiting for all new OpenStack VMs to be reachable via SSH.

Installation of Kubernetes dependencies and system configurations required for Kubernetes on the instance running Q8S.

Initializing the Kubernetes cluster and installing Flannel.

Extracting the Kubernetes token for joining of worker nodes and uploading cluster certificates, required for joining control plane nodes.

Installation of Kubernetes dependencies and system configurations on the additional control plane nodes.

Joining of the additional control plane nodes to the cluster.

Installation of QEMU and libvirt on the worker hosts.

Configuring of the QEMU network to ensure the desired IP address that matches the host IP will be assigned to the QEMU VM.

Downloading of the Ubuntu Cloud-Images.

Preparation of the user-data and meta-data files for the Cloud-Image VM.

Preparation of the Cloud-Image for QEMU.

Creation of the QEMU VM from the Cloud-Image.

Installation of Kubernetes and dependencies and system configurations on the QEMU VMs as triggered by cloud-init.

Waiting for all worker nodes to join the Kubernetes cluster.

Once all these steps are completed, the cluster is ready to be used and Q8S is not required anymore. In the prototype implementation of Q8S, the above steps are executed sequentially and are still open to optimization through parallelization, for example, by letting the deployment process of the additional control plane nodes and the emulated worker nodes run in parallel.

3.2. Evaluation

Benchmark

In this section, we discuss the measurements that were acquired according to the methods described in

Section 2.2.

Table 1 shows the bandwidth measured through the benchmark for pod-to-pod and pod-to-service communication for emulated and non-emulated nodes via TCP and UDP. Except for UDP being slightly slower on the emulated nodes, the performance is identical despite the additional layer of networking that applies for the emulated nodes.

The difference in UDP speed could be related to the UDP packet size [

27] being not optimal for wrapping in the Flannel environment. As the difference is marginal we consider the networking performance to be effectively identical.

The network latencies measured are given in the following:

Worker-Node-to-Worker-Node round-trip latency:

Pod-to-Pod (different nodes) round-trip latency:

Pod-to-Pod (same node) round-trip latency:

Worker-Node-to-Control-Plane-Node round-trip latency:

Control-Plane-Node-to-Control-Plane-Node round-trip latency:

Between control plane nodes, no additional iptables rules are applied, between a worker node and a control plane node, one set of iptables rules are applied and between worker nodes, the iptables are applied both on being sent and on being received.

Going from no iptables rules to one pass adds about 1 ms of latency and adding another pass adds another 1.6 ms. Compared to pod-to-pod on two worker nodes this becomes even slower as it now also has to pass through the Kubernetes internal networking.

Considering the low latency for direct pings between two hosts, these latencies created by the additional iptables and network virtualization layers seem high but are overall still relatively low and acceptable for the majority of use cases.

The CPU usage of the nodes during the throughput benchmark as well as during idle is given in

Table 2. The benchmark consists of a client and server pairing, where the client sends requests to the server.

The CPU usage is significantly higher for the emulated nodes compared to the OpenStack nodes. Even during the benchmark, the benchmark, the CPU usage of the OpenStack node barely goes up except for the UDP communication where it is significantly increased for the client node but not the server node.

The reason for the increased CPU usage most probably lies in the virtualization as for each CPU instruction, the hypervisor has to perform additional operations to check and translate the instruction in addition to actually performing the instruction. This overhead factor even varies between client and server such that we can assume that sending and receiving requests requires different amounts of overhead operations by the hypervisor.

Regarding the increased client CPU usage for UDP, when comparing the measurements to other benchmarks created with k8s-bench-suite [

28], these also show an increase in CPU usage for UDP clients. As the test setup only features 2 CPU cores, these differences could have become even more pronounced compared to the external example.

The memory usage of the nodes is given in

Table 3 and shows no significant changes during the benchmark. Notably, the memory usage of the emulated server is even slightly lower than the OpenStack server. Overall the memory usage does not vary significantly such that it appears to be well handled by the emulation layer.

Requirements

In this part we discuss how the presented prototype for Q8S aligns with the functional requirements, which we defined in

Section 2.

As we were able to perform the benchmarking on a Kubernetes cluster deployed through Q8S we can consider

FR5 as completed. The benchmarking was performed on an OpenStack cluster for which we did not request any additional privileges, fulfilling

FR1 and

FR6. Specifying the node settings including system architecture, CPU speed, core count, memory and storage size also worked, which completes

FR2. Q8S was also able to deploy the desired amount of node types and set up a working emulation for them, which matches

FR3 and

FR4.

Table 4 provides an overview of the status of the requirements.

However, while Q8S completes the goals we set out for it, we still see further features and improvements that should be made. These include support for limiting bandwidth and latency along with simulating network failure rates to emulate edge nodes. Moreover, Q8S works slow and a full deployment can take over an hour, highlighting the need to parallelize and optimize the process. Nevertheless, once the deployment is complete, the created cluster can be used for multiple rounds of experiments without having to rerun Q8S, making Q8S a valuable tool for emulating instead of simulating heterogeneous Kubernetes clusters.

4. Discussion

While Q8S fulfills its initial requirements, there are still some limitations and considerations that should be mentioned.

4.1. Limitations

The current implementation of Q8S only supports up to 252 nodes in an emulated cluster as the /24 subnet in OpenStack is used and some IPs are already reserved for the starting instance and the OpenStack router. This could be expanded to a /16 subnet, however, this would require changing the implementation on how the matching of IPs between the hosts and QEMU Vms works as having an identical last section of the IP address does not work with subnets larger than /24.

It should also be noted that when running an emulation, the compute capabilities of the emulated node cannot exceed those of the host node. Moreover, as the hosts also consume some CPU time and memory in order to run their operating systems and QEMU, when setting the emulated nodes resources to close to those of the host, some of these are not guaranteed to be available to the emulated node.

Another limitation is that due to the usage of QEMU and libvirt, only hardware that is supported by these applications can be emulated via Q8S. The supported hardware is further restricted due to the reliance on Ubuntu Cloud-Images, which typically builds for 64-bit x86 and ARM systems. Supporting other architectures, such as 32-bit systems, would require building Cloud-Images with 32 bit support or significantly adjusting the installation process of Q8S to not rely on Ubuntu Cloud-Images.

4.2. Implications

With Q8S we provide a tool for emulating heterogeneous Kubernetes clusters. This enables researchers and developers of software for such clusters, for example, alternative scheduling systems, to perform tests and gather more detailed data compared to using simulated clusters if access to real heterogeneous hardware is not available. Furthermore, an emulated cluster can potentially be used to gather data to train machine learning models or have scheduling algorithm actively learn via reinforcement learning. Q8S, therefore, extends the selection of available tools to researchers beyond existing simulation tools such as CloudSim, K8sSim and EMUSIM.

5. Conclusions

In this work we have identified the need for emulated heterogeneous Kubernetes clusters in order to provide more accurate environments compared to utilizing simulation tools. To fill this need we have designed and implemented Q8S as a tool for automatically deploying such clusters on top of OpenStack clouds by using QEMU to emulate heterogeneous nodes, e.g., ARM nodes on top of x86 machines. Moreover, we have validated the functionality of Q8S and benchmarked the performance overhead imposed by the emulation layer and found it to be acceptable.

We provide our prototype implementation of Q8S under an open source license to enable its adaptation and further development.

5.1. Future Work

The prototype of Q8S is functional but could be further improved. Many other simulations support setting bandwidth and latency for connections, which is to be implemented in Q8S. Similarly, support for network and node failures, which may occur more frequently for heterogeneous clusters with components outside of a data center, are also not yet supported. Due to the multiple layers involved when deploying a cluster via Q8S, if any of the deployment scripts get stuck and fail to complete, it can be difficult to identify the issue or even to retrieve the logs of the failed script. For this, Q8S requires a proper error handling system, which observes the deployment logs across the all layers such that the user can immediately be pointed to the failing component.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D., V.F.H. and J.K.; methodology, J.D., V.F.H. and J.K.; software, J.D. and V.F.H.; validation, V.F.H.; formal analysis, V.F.H.; investigation, J.D. and V.F.H.; resources, J.D.; data curation, V.F.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.D.; writing—review and editing, J.D. and J.K.; visualization, V.F.H.; supervision, J.D. and J.K.; project administration, J.K.; funding acquisition, J.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) under the AI service center KISSKI (grant no. 01IS22093A and 01IS22093B).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The computing systems for developing and testing Q8S in this study were kindly made available by the GWDG (

https://gwdg.de).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| VM |

Virtual Machine |

| IO |

Input/Output |

| VMM |

Virtual Machine Manager |

| IP |

Internet Protocol |

| LAN |

Local Area Network |

| VXLAN |

Virtual Extensible LAN |

| NAT |

Network Adress Translation |

| QEMU |

Quick EMUlator |

| KVM |

Kernel-based Virtual Machine |

| MIPS |

Million Instructions Per Second |

| API |

Application Programming Interface |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| CLI |

Command Line Interface |

| YAML |

Yet Another Markup Language |

| OS |

Operating System |

| VTEP |

VXLAN Tunnel Endpoint |

| SNAT |

Source NAT |

| DNAT |

Destination NAT |

Appendix A

|

Listing 1. An Example File for a Cluster Definition. The notation using ’!’, e.g., !ClusterData and !VmType, is used by Q8S to map the respective sections of the configuration to Python data classes. |

|

References

- Kiswani, J.H.; Dascalu, S.M.; Harris, F.C. Cloud Computing and Its Applications: A Comprehensive Survey 2021. 28.

- Islam, R.; Patamsetti, V.; Gadhi, A.; Gondu, R.M.; Bandaru, C.M.; Kesani, S.C.; Abiona, O. The Future of Cloud Computing: Benefits and Challenges. International Journal of Communications, Network and System Sciences 2023, 16, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CNCF Annual Survey 2023, 2023.

- Senjab, K.; Abbas, S.; Ahmed, N.; Khan, A.u.R. A Survey of Kubernetes Scheduling Algorithms. Journal of Cloud Computing 2023, 12, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeeq, M.M.; Abdulkareem, N.M.; Zeebaree, S.R.M.; Ahmed, D.M.; Sami, A.S.; Zebari, R.R. IoT and Cloud Computing Issues, Challenges and Opportunities: A Review. Qubahan Academic Journal 2021, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión, C. Kubernetes Scheduling: Taxonomy, Ongoing Issues and Challenges. Acm Computing Surveys 2022, 55, 138–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.; AlFailakawi, M.G.; AlMutawa, A.; Alsalman, L. Container Scheduling Techniques: A Survey and Assessment. Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences 2022, 34, 3934–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mars, J.; Tang, L.; Hundt, R. Heterogeneity in “Homogeneous” Warehouse-Scale Computers: A Performance Opportunity.

- Kunkel, J.; Boehme, C.; Decker, J.; Magugliani, F.; Pleiter, D.; Koller, B.; Sivalingam, K.; Pllana, S.; Nikolov, A.; Soyturk, M.; et al. DECICE: Device-edge-cloud Intelligent Collaboration Framework. In Proceedings of the Computing Frontiers. ACM; 5 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calheiros, R.N.; Ranjan, R.; Beloglazov, A.; De Rose, C.A.F.; Buyya, R. CloudSim: A Toolkit for Modeling and Simulation of Cloud Computing Environments and Evaluation of Resource Provisioning Algorithms. Software: Practice and Experience 2011, 41, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bux, M.; Leser, U. DynamicCloudSim: Simulating Heterogeneity in Computational Clouds. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGMOD Workshop on Scalable Workflow Execution Engines and Technologies, New York, NY, USA, 6 2013. [CrossRef]

- Kathiravelu, P.; Veiga, L. Concurrent and Distributed CloudSim Simulations. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 22nd International Symposium on Modelling, Analysis & Simulation of Computer and Telecommunication Systems; 9 2014; pp. 490–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calheiros, R.N.; Netto, M.A.; De Rose, C.A.; Buyya, R. EMUSIM: An Integrated Emulation and Simulation Environment for Modeling, Evaluation, and Validation of Performance of Cloud Computing Applications. Software: Practice and Experience 2013, 43, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Han, R.; Qiu, K.; Ma, X.; Li, Z.; Deng, H.; Liu, C.H. K8sSim: A Simulation Tool for Kubernetes Schedulers and Its Applications in Scheduling Algorithm Optimization. Micromachines 2023, 14, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- QEMU.

- GitHub - InfraBuilder/K8s-Bench-Suite: Simple Scripts to Benchmark Kubernetes Cluster Features.

- Libvirt: The Virtualization API.

- Anthony, R.J. Chapter 5 - The Architecture View. In Systems Programming; Anthony, R.J., Ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: Boston, 2016; pp. 277–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Haro, F.; Freitag, F.; Navarro, L.; Hernánchez-sánchez, E.; Farías-Mendoza, N.; Guerrero-Ibáñez, J.A.; González-Potes, A. A Summary of Virtualization Techniques. Procedia Technology 2012, 3, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Wang, H.; Soyata, T. Hardware and Software Aspects of VM-Based Mobile-Cloud Offloading; 2015; pp. 247–271. [CrossRef]

- Tsetse, A.; Tweneboah-Koduah, S.; Rawal, B.; Zheng, Z.; Prattipati, M. A Comparative Study of System Virtualization Performance. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 20th International Conference on Information Reuse and Integration for Data Science (IRI); 7 2019; pp. 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.T.; Nieh, J. Optimizing Nested Virtualization Performance Using Direct Virtual Hardware. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, Lausanne Switzerland, 3 2020. [CrossRef]

- Kapočius, N. Overview of Kubernetes CNI Plugins Performance. Mokslas - Lietuvos ateitis 2020, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Trivedi, M.C. Networking Analysis and Performance Comparison of Kubernetes CNI Plugins. In Proceedings of the Advances in Computer, Communication and Computational Sciences; Bhatia, S.K.; Tiwari, S.; Ruidan, S.; Trivedi, M.C.; Mishra, K.K., Eds., Singapore; 2021; pp. 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, A. Introduction to Modeling and Simulation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 29th Conference on Winter Simulation, 1997, pp.

- Hasse, V.F. Emulation of Heterogeneous Kubernetes Clusters Using QEMU, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, M.J.; Richter, T. Achieving Reliable UDP Transmission at 10 Gb/s Using BSD Socket for Data Acquisition Systems. Journal of Instrumentation 2020, 15, T09005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://github.com/InfraBuilder/benchmark-k8s-cni-2020-08/blob/master/results/doc-flannel.u18.04-default/doc-flannel.u18.04-default-run1.knbdata.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).