Submitted:

25 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

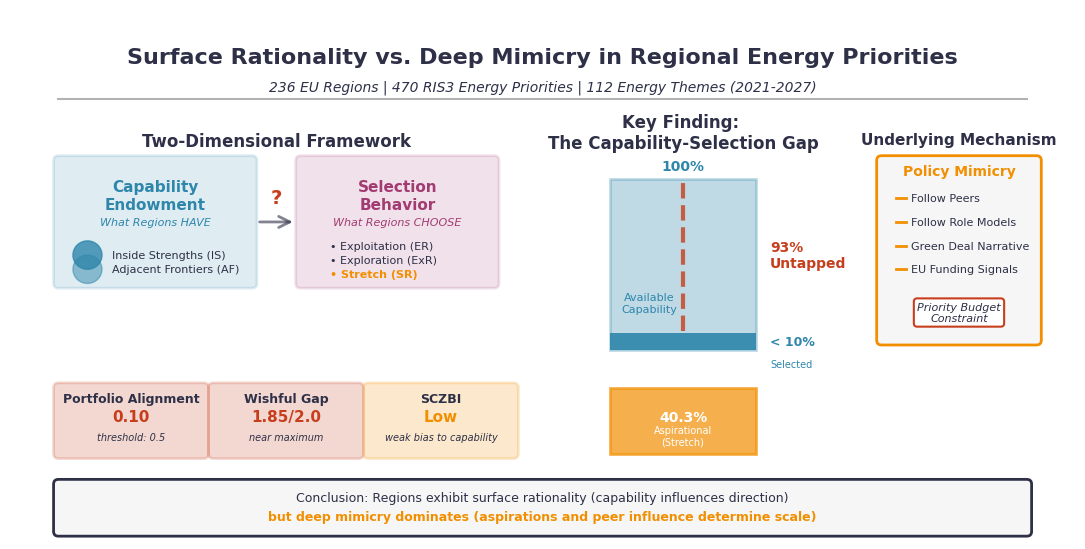

1.1. The Two-Dimensional Challenge: Endowment and Selection

1.2. Research Questions and Hypotheses

1.2.1. RQ1: What Energy Capability Endowments Do Regions Possess, and How Do These Evolve Over Time?

1.2.2. RQ2: How Do Regions' Capability Endowments Shape Their Priority Selection Behavior?

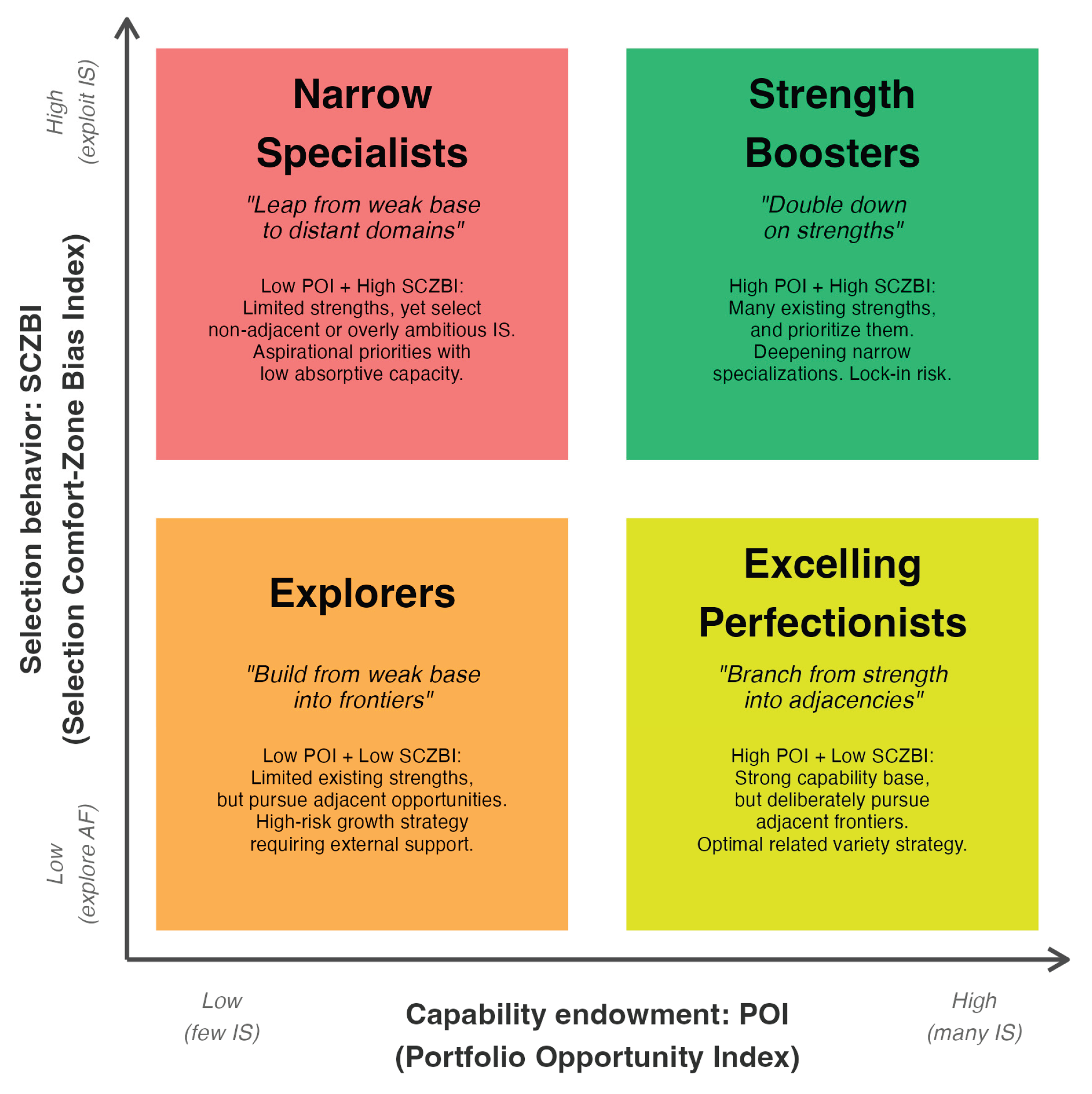

- H1 (Rational Selection Hypothesis): If regions engage in evidence-based entrepreneurial discovery [13,14,25,37], they should align priorities with capability endowments. Specifically, regions with more inside strengths (high POI) should exploit them by exhibiting higher SCZBI and higher ER (> 15%), while regions with abundant adjacent frontiers (low POI) should exhibit lower SCZBI and higher ExR (> 15%). This hypothesis predicts a positive correlation between POI and SCZBI among comfort-zone-biased regions (upper half of POI × SCZBI space) and positive correlation among exploration-biased regions (lower half), reflecting “following the indicators” logic [20]. Empirically, we test whether POI predicts selection intensity (ER and ExR) after controlling for regional characteristics (GDP per capita, R&D capacity, legacy of energy priorities in 2014–2020).

- H2 (Explorative Selection Hypothesis): Alternatively, regions may prioritize organizational learning and capability building [19,28] by systematically targeting AF to utilize related variety mechanisms [30,31,32]. High-POI regions with strong bases may branch into adjacencies (Excelling Perfectionists), while low-POI regions may build from abundant AF potential (Explorers). This hypothesis predicts high ExR (> 15%) among low-SCZBI regions, regardless of POI, and positive correlation between AF potential (number of adjacent frontier topics) and ExR. This would reflect forward-looking diversification strategies that stretch but respect relatedness constraints.

- H3 (Mimicry and Wishful Thinking Hypothesis): Despite normative aspirations for evidence-based selection, institutional isomorphism [19] and policy mimicry [20,35] may dominate. Regions may “follow peers” (selecting domains common in their reference group) or “follow role models” (emulating successful innovators like Germany’s hydrogen strategy or Denmark’s offshore wind) rather than “follow indicators” (grounding selection in capabilities). This hypothesis predicts: (1) low portfolio-priority alignment (cosine similarity < 0.3), indicating priorities are decoupled from pre-policy activity; (2) high wishful gaps (L1 distance > 1.5, approaching the maximum of 2.0), reflecting compositional mismatch; (3) high Stretch Rates (SR > 30%), indicating systematic targeting of domains outside both IS and AF; and critically, (4) substitution rather than addition—high SR should negatively predict ER and ExR in multivariate regressions (β < 0), revealing that regions face “priority budget” constraints and allocate slots to aspirational targets at the expense of capability-based choices. This would confirm that mimicry displaces, rather than complements, evidence-based selection.

1.3. Integrated Theoretical Framework and Contributions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data and Topic Space Construction

2.1.1. Data Sources and Spatial Harmonisation

2.1.2. Extracting Topics and Aligning Them to Regional Priorities

2.1.3. Regional Panel Construction

2.2. Mapping Regional Capability Endowments and Evolution (RQ1)

2.2.1. Pre-Policy Topic Shares

2.2.2. Topic Similarity Matrix

2.2.3. Relatedness Density

2.2.4. Definitions of Capability Endowment Tags

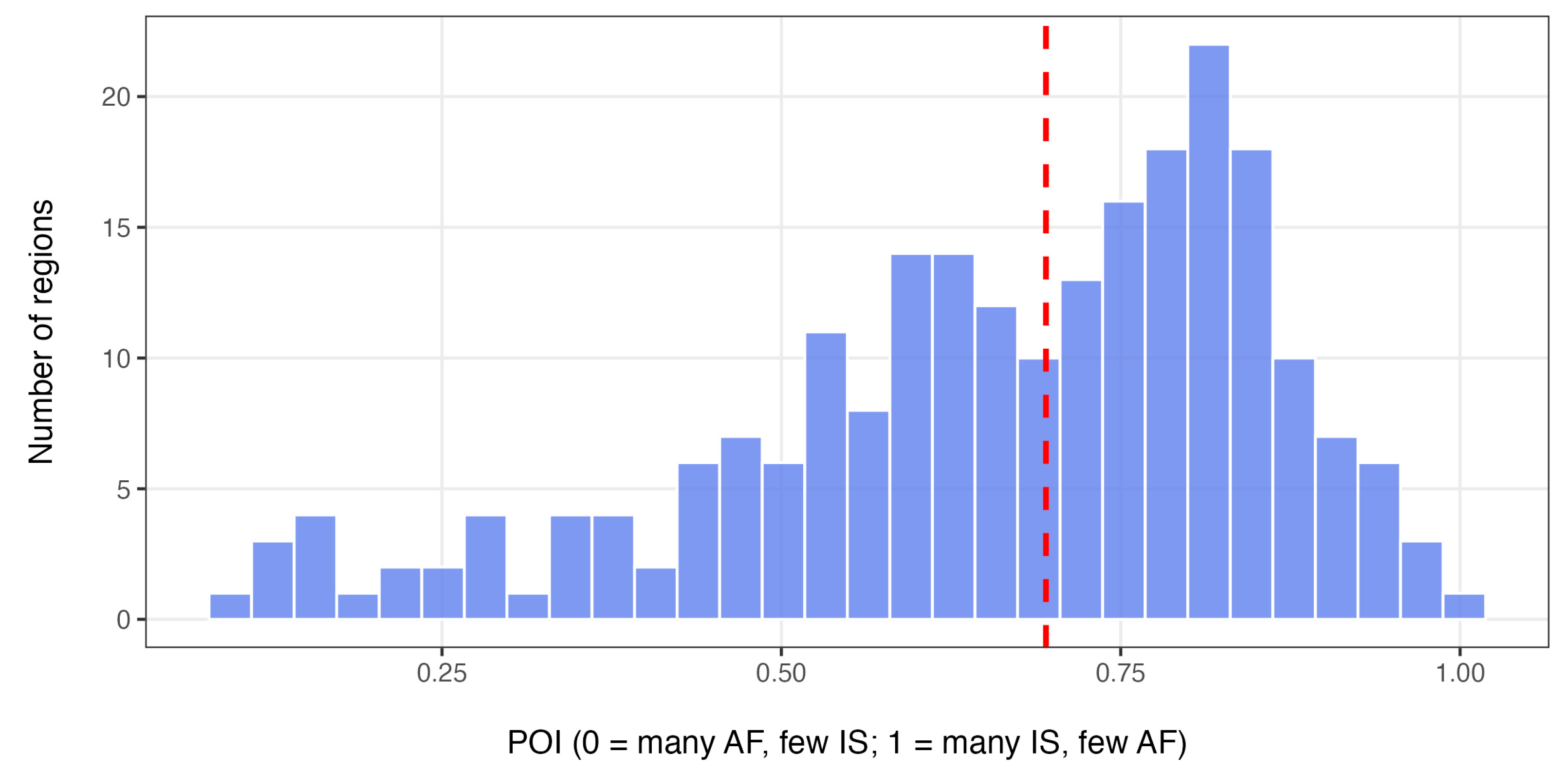

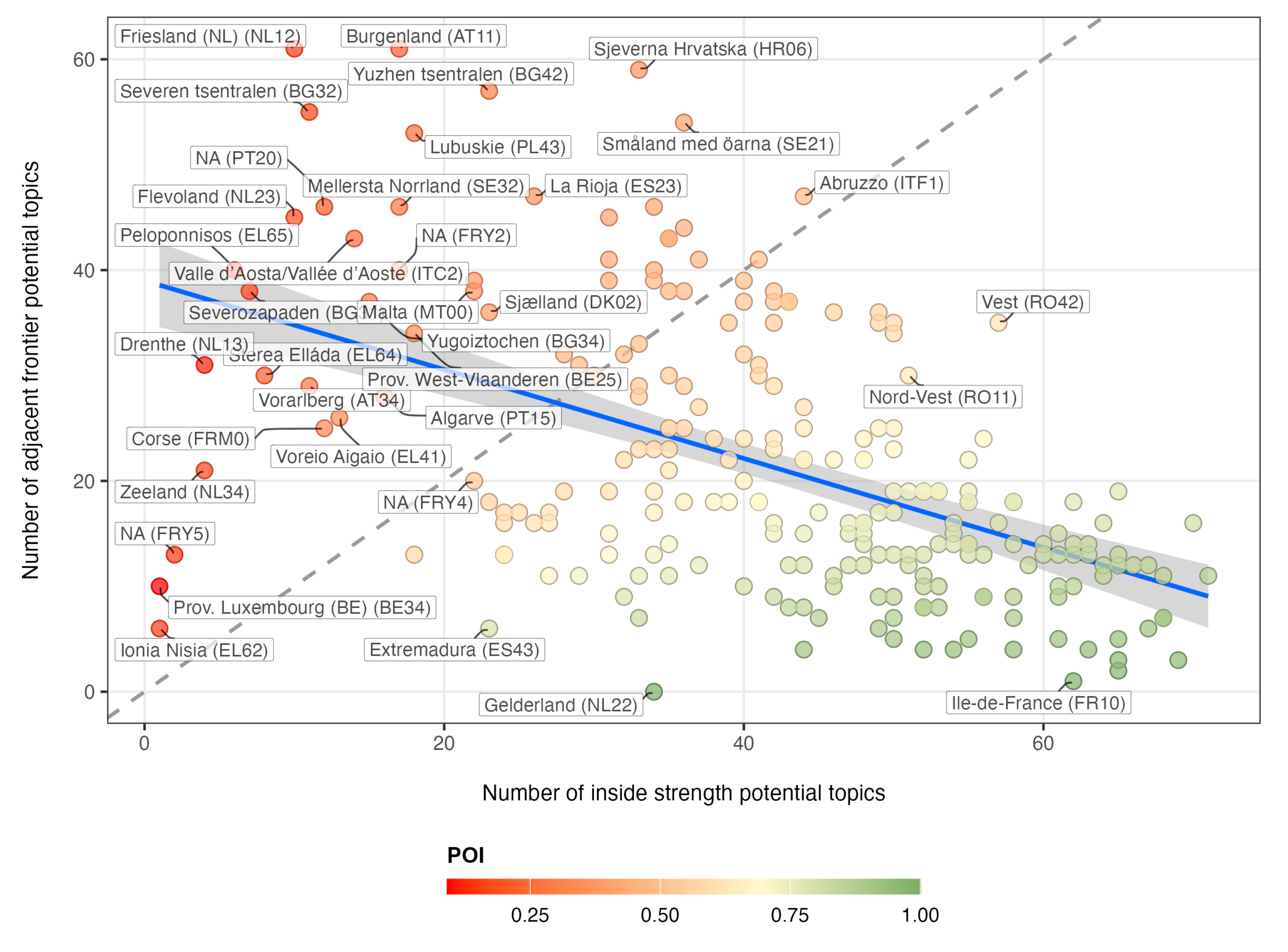

2.2.5. Portfolio Opportunity Index (POI)

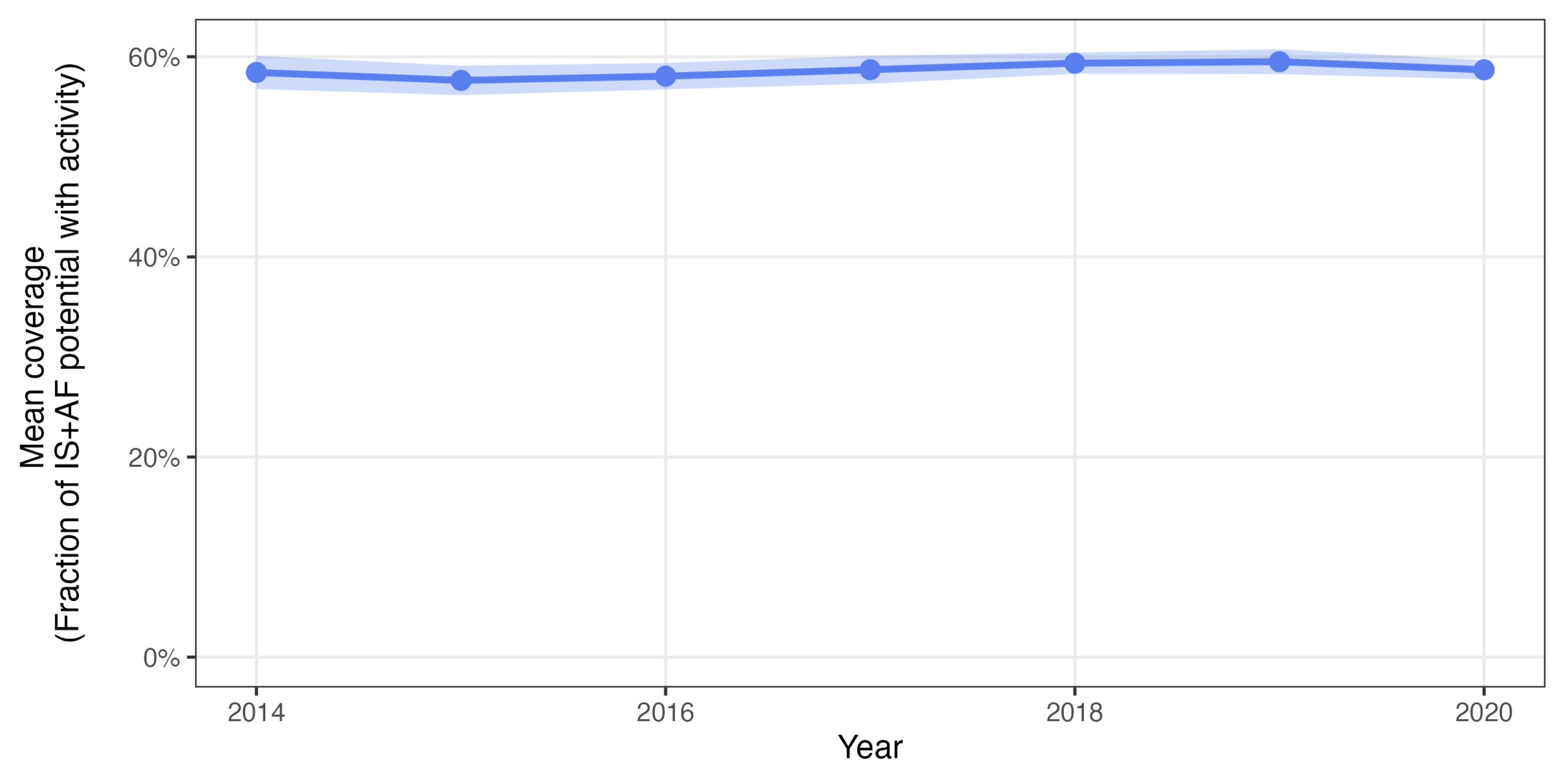

2.2.6. Coverage Dynamics: Temporal Evolution of Capability Portfolios

2.3. Characterizing Priority Selection Behavior (RQ2)

2.3.1. Treatment Assignment and Priority Flags

2.3.2. Priority Positioning Tags

2.3.3. Selection Comfort-Zone Bias Index (SCZBI)

2.3.4. Selection Rates: Exploitation, Exploration, and Stretch

2.3.5. Portfolio-Priority Concordance: Alignment and Wishful Gap

2.3.6. Opportunity Cost Index (OCI)

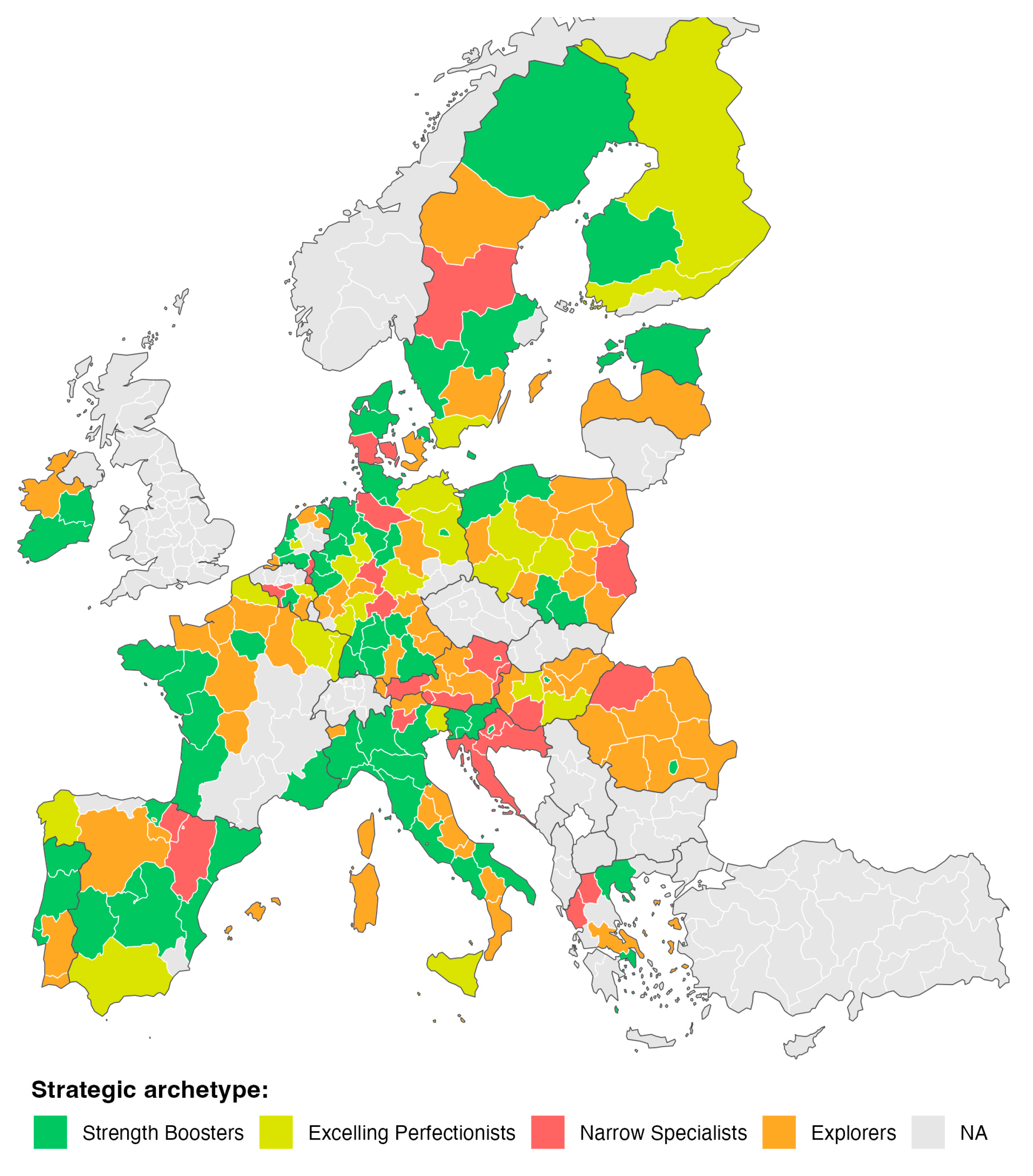

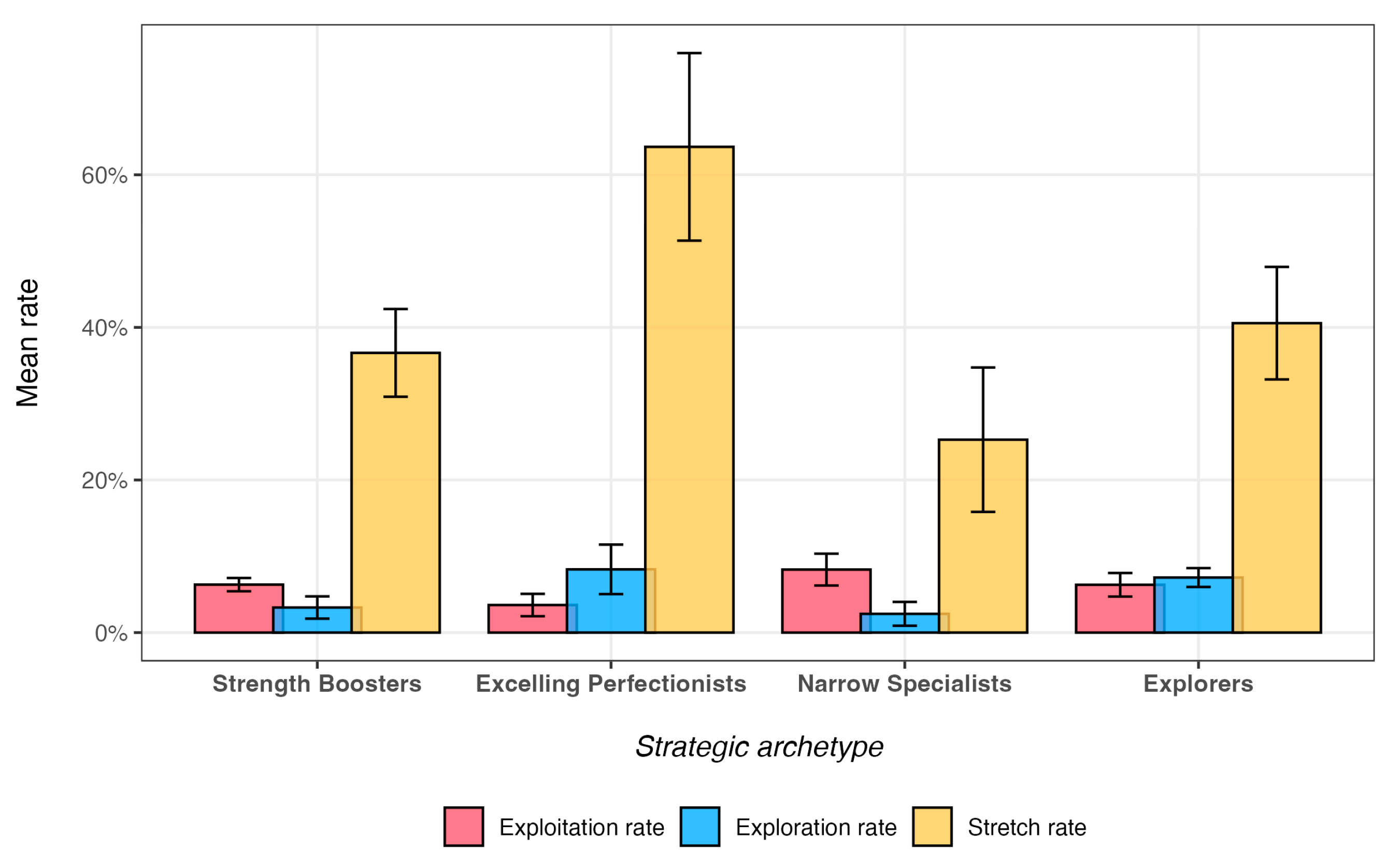

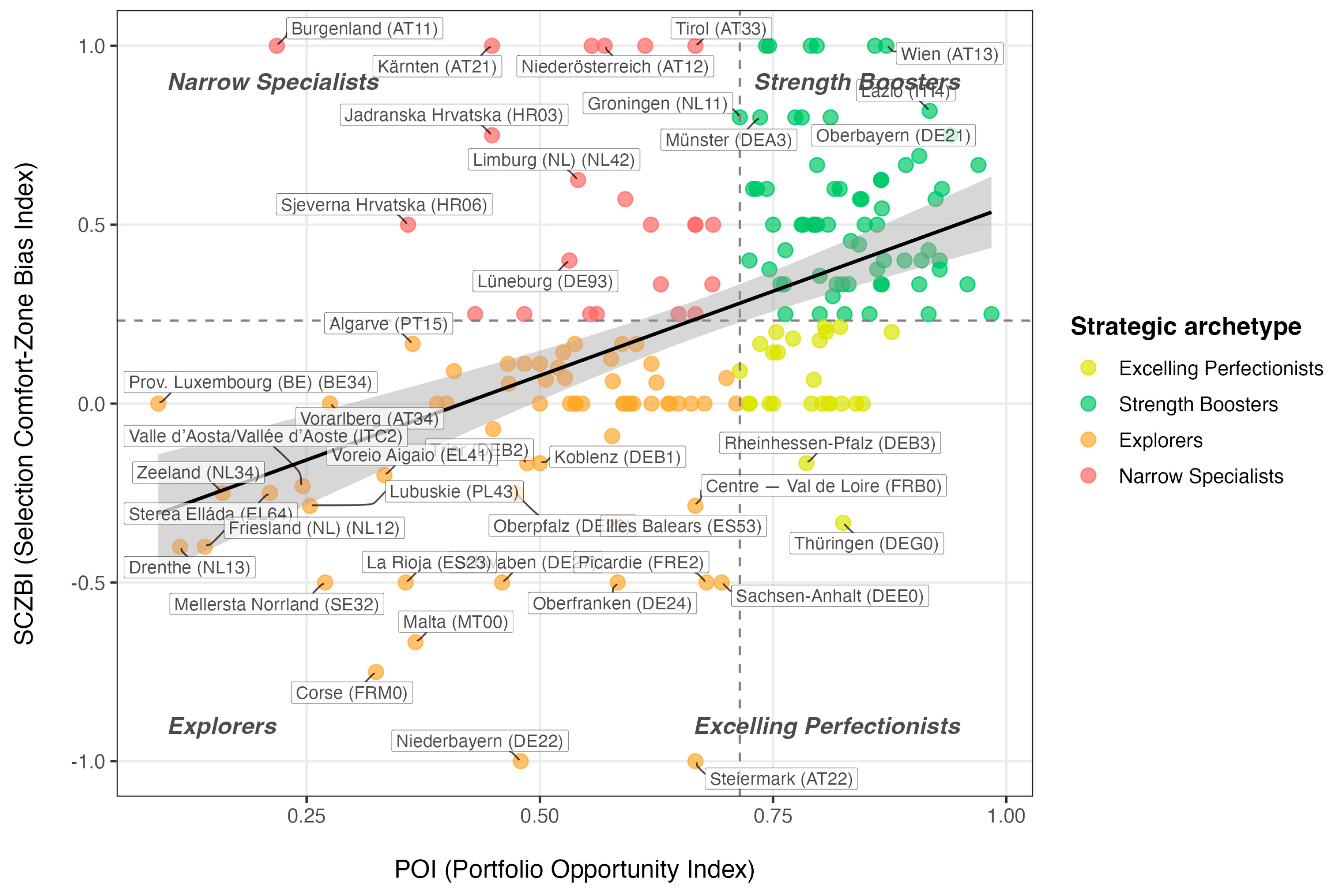

2.3.7. Strategic Archetype Classification

- High POI: (many inside strengths)

- Low POI: (few inside strengths, many adjacencies)

- High SCZBI: (comfort-zone bias)

- Low SCZBI: (frontier exploration)

- Strength Boosters (high POI, high SCZBI): Many existing strengths, and prioritize them. Deepening narrow specializations, lock-in risk.

- Excelling Perfectionists (high POI, low SCZBI): Strong capability base, but deliberately pursue adjacent frontiers. Optimal related variety strategy.

- Narrow Specialists (low POI, high SCZBI): Limited strengths, yet select non-adjacent or overly ambitious IS. Aspirational priorities with low absorptive capacity.

- Explorers (low POI, low SCZBI): Limited existing strengths, but pursue adjacent opportunities. High-risk growth strategy requiring external support.

3. Results

3.1. Regional Capability Endowments and Evolution (RQ1)

3.1.1. Topic Similarity and Relatedness Structure

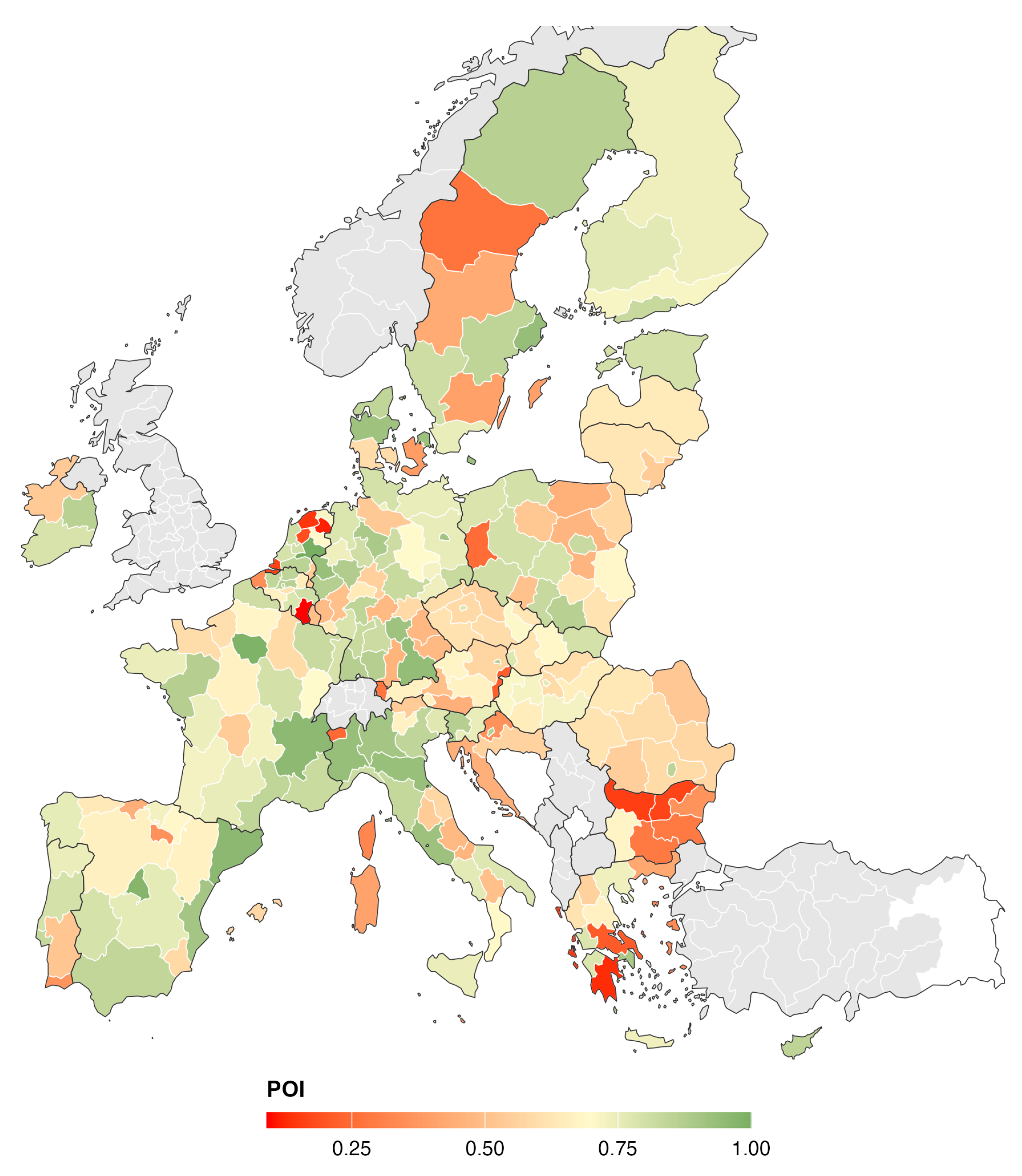

3.1.2. Distribution of Capability Endowments

3.1.3. Portfolio Dynamics in the Pre-Policy Period (2014–2020)

3.2. Priority Selection Behavior: Rational, Explorative, or Mimicry? (RQ2)

3.2.1. Descriptive Overview of Selection Behavior

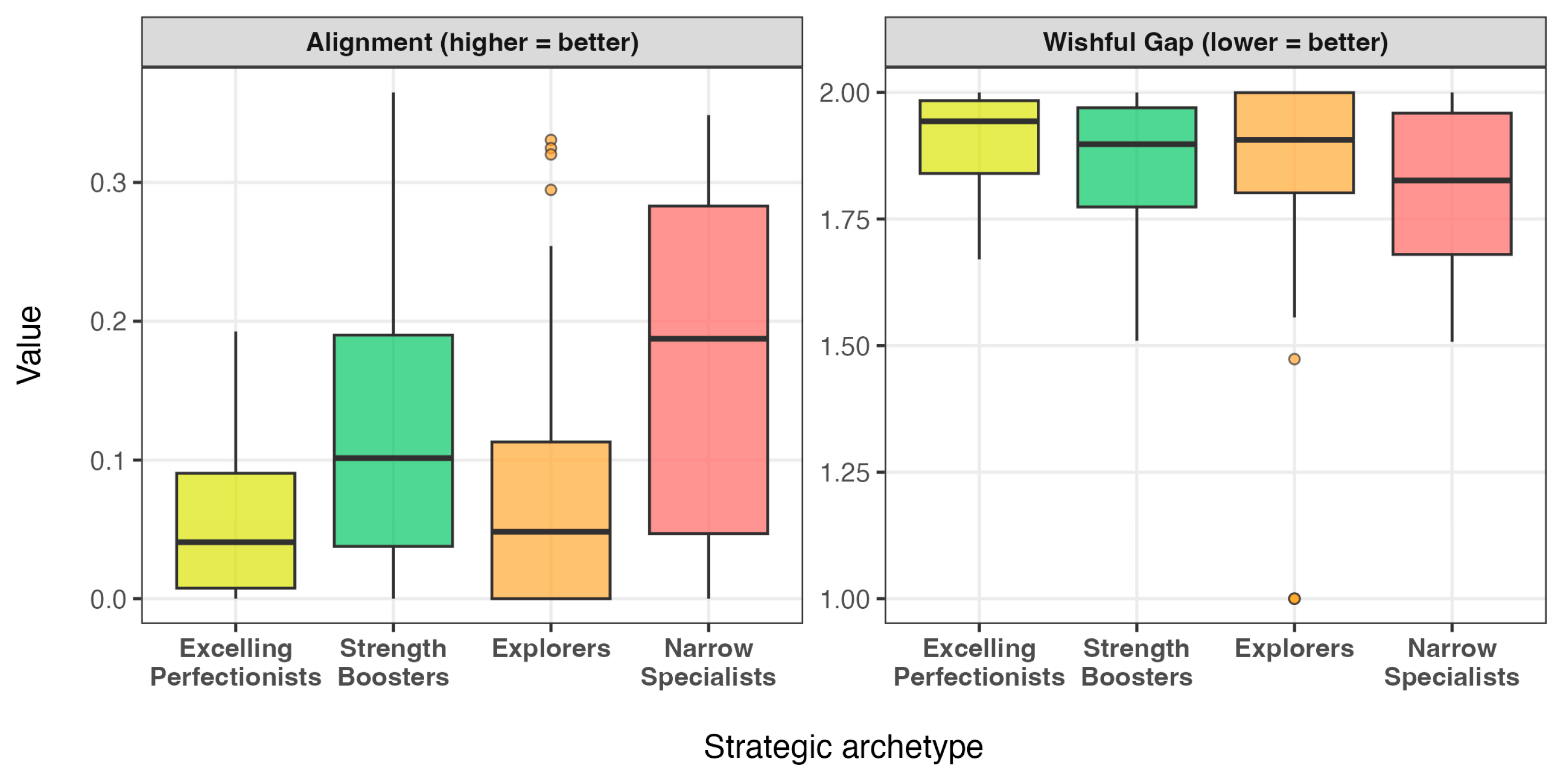

3.2.2. Strategic Archetype Classification

3.2.3. Testing Hypotheses on Selection Behavior

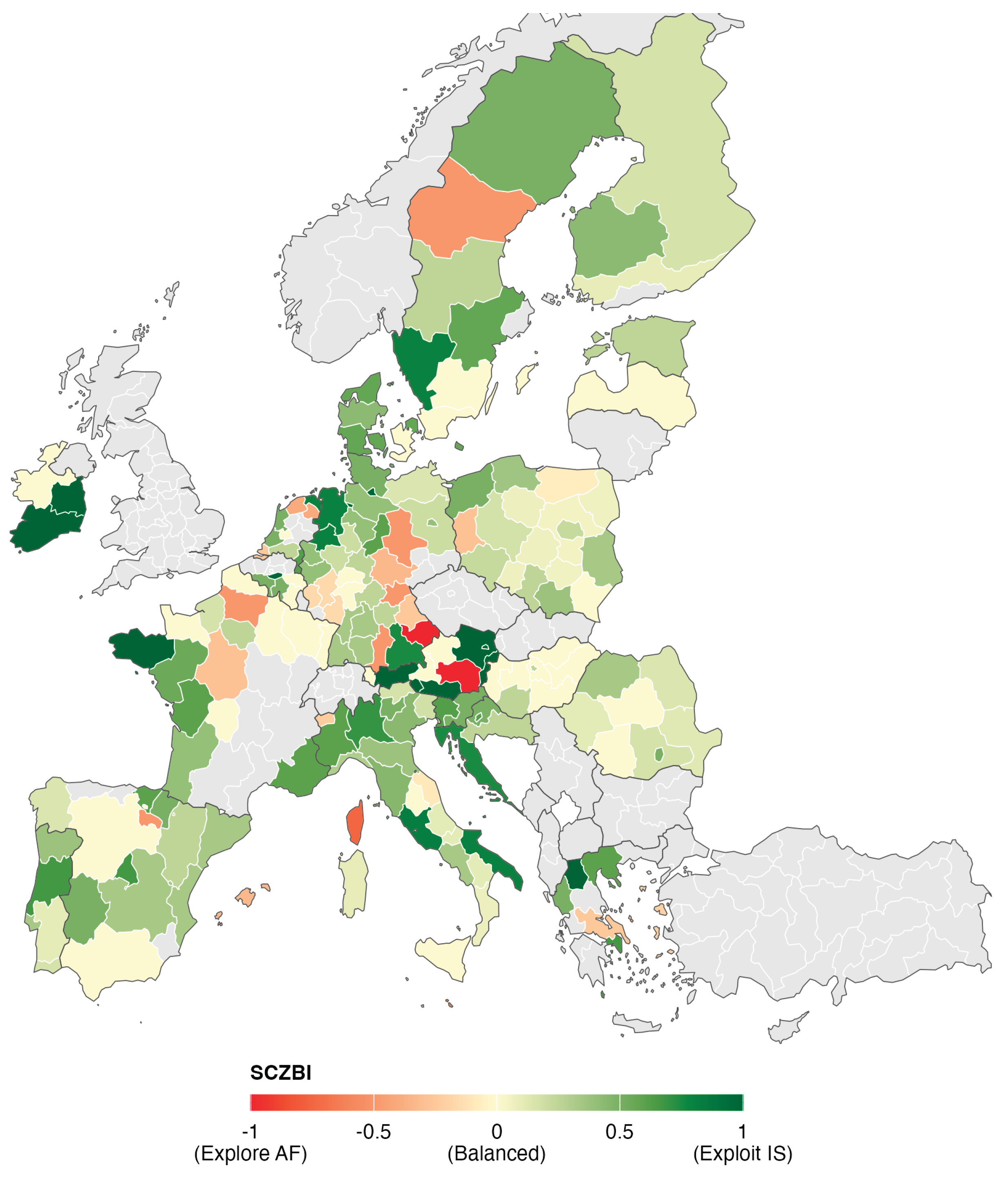

3.2.4. Spatial Patterns and Legacy Effects

4. Discussion and Conclusion

4.1. Key Findings and Contributions

4.2. Theoretical Implications: Reconceptualizing Smart Specialization

4.3. Policy Implications: Rethinking Smart Specialization Design

4.4. Limitations and Boundary Conditions

4.5. Future Research Directions

4.6. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schanes, K.; Jäger, J.; Drummond, P. Three Scenario Narratives for a Resource-Efficient and Low-Carbon Europe in 2050. Ecological Economics 2019, 155, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCotis, P.A.; Cartwright, E.D. The Transition to a Low-Carbon Economy. Climate and Energy 2022, 39, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labianca, M.; Faccilongo, N.; Monarca, U.; Lombardi, M. A Location Model for the Agro-Biomethane Plants in Supporting the REPowerEU Energy Policy Program. Sustainability 2023, 16, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farole, T.; Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Storper, M. Cohesion Policy in the European Union: Growth, Geography, Institutions. JCMS Journal of Common Market Studies 2011, 49, 1089–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Etzkowitz, H. Theorizing the Triple Helix Model: Past, Present, and Future. Triple Helix Journal 2020, 7, 189–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschma, R. Relatedness as Driver of Regional Diversification: A Research Agenda. Regional Studies 2017, 51, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Careri, F.; Efthimiadis, T.; Masera, M. 2020–2022: Pivotal Years for European Energy Infrastructure. Energies 2022, 15, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Di Cataldo, M. Quality of Government and Innovative Performance in the Regions of Europe. Journal of Economic Geography 2015, 15, 673–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charron, N.; Lapuente, V.; Annoni, P. Measuring Quality of Government in EU Regions across Space and Time. Papers in Regional Science 2019, 98, 1925–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. Innovation Prone and Innovation Averse Societies: Economic Performance in Europe. Growth and Change 1999, 30, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, P.; Ortega-Argilés, R. The Early Experience of Smart Specialization Implementation in EU Cohesion Policy. null 2016, 24, 1407–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianelle, C.; Kyriakou, D.; McCann, P.; Morgan, K. Smart Specialisation on the Move: Reflections on Six Years of Implementation and Prospects for the Future. null 2020, 54, 1323–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foray, D. From Smart Specialisation to Smart Specialisation Policy. European Journal of Innovation Management 2014, 17, 492–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foray, D.; David, P.A.; Hall, B. Smart Specialisation – the Concept. Knowledge Economists Policy Brief 2009, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- McCann, P.; Ortega-Argilés, R. Smart Specialization, Regional Growth and Applications to European Union Cohesion Policy. Regional Studies 2015, 49, 1291–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, H. Efforts to Implement Smart Specialization in Practice—Leading Unlike Horses to the Water. European Planning Studies 2015, 23, 2079–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capello, R.; Kroll, H. From Theory to Practice in Smart Specialization Strategy: Emerging Limits and Possible Future Trajectories. European Planning Studies 2016, 24, 1393–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cataldo, M.; Monastiriotis, V.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. How ‘Smart’ Are Smart Specialization Strategies? JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 2020, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. American Sociological Review 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pylak, K.; Deegan, J.; Broekel, T. Smart Specialisation or Smart Following? A Study of Policy Mimicry in Priority Domain Selection. Regional Studies 2025, 59, 2429626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo-Gallardo, E.; Arranz, N.; Arróyabe, J.C.F. de Contribution of the Horizon2020 Program to the Research and Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialization in Coal Regions in Transition: The Spanish Case. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. Technological Transitions as Evolutionary Reconfiguration Processes: A Multi-Level Perspective and a Case-Study. Research Policy 2002, 31, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. The Multi-Level Perspective on Sustainability Transitions: Responses to Seven Criticisms. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 2011, 1, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pylak, K.; Pizoń, J.; Łazuka, E. Evolution of Regional Innovation Strategies Towards the Transition to Green Energy in Europe 2014–2027. Energies 2024, 17, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassink, R.; Gong, H. Six Critical Questions about Smart Specialization. European Planning Studies 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neffke, F.; Henning, M.; Boschma, R. How Do Regions Diversify over Time? Industry Relatedness and the Development of New Growth Paths in Regions. Economic Geography 2011, 87, 237–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balland, P.-A.; Boschma, R.; Crespo, J.; Rigby, D. Smart Specialization Policy in the European Union: Relatedness, Knowledge Complexity and Regional Diversification. Regional Studies 2019, 53, 1252–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning. Organization Science 1991, 2, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschma, R.; Iammarino, S. Related Variety, Trade Linkages, and Regional Growth in Italy. Economic Geography 2009, 85, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenken, K.; Van Oort, F.; Verburg, T. Related Variety, Unrelated Variety and Regional Economic Growth. Regional Studies 2007, 41, 685–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschma, R.; Capone, G. Institutions and Diversification: Related versus Unrelated Diversification in a Varieties of Capitalism Framework. Research Policy 2015, 44, 1902–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, M.; Kublina, S. Related Variety, Unrelated Variety and Regional Growth: The Role of Absorptive Capacity and Entrepreneurship. Reg Stud 2017, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, F.L.; Hartmann, D.; Boschma, R.; Hidalgo, C.A. The Time and Frequency of Unrelated Diversification. Research Policy 2021, 104323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, W.M.; Levinthal, D.A. Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly 1990, 35, 128–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, J.; Broekel, T.; Fitjar, R.D. Searching through the Haystack: The Relatedness and Complexity of Priorities in Smart Specialization Strategies. null 2021, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. The Economy of Cities; A Vintage book, V-584; Random House: New York, 1969; ISBN 978-0-394-42296-1. [Google Scholar]

- Foray, D. Smart Specialisation: Opportunities and Challenges for Regional Innovation Policy; Routledge: Abingdon, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tödtling, F.; Asheim, B.; Boschma, R. Knowledge Sourcing, Innovation and Constructing Advantage in Regions of Europe. European Urban and Regional Studies 2013, 20, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asheim, B.; Smith, H.L.; Oughton, C. Regional Innovation Systems: Theory, Empirics and Policy. Regional Studies 2011, 45, 875–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschma, R.; Balland, P.-A.; Kogler, D.F. Relatedness and Technological Change in Cities: The Rise and Fall of Technological Knowledge in US Metropolitan Areas from 1981 to 2010. Industrial and Corporate Change 2015, 24, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Sunley, P. Path Dependence and Regional Economic Evolution. Journal of Economic Geography 2006, 6, 395–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillitsch, M.; Asheim, B.; Trippl, M. Unrelated Knowledge Combinations: The Unexplored Potential for Regional Industrial Path Development. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 2018, 11, 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillitsch, M.; Hansen, T. Green Industry Development in Different Types of Regions. European Planning Studies 2019, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| # regions | Mean | SD | Min | Q25 | Median | Q75 | Max | Gini | Mean # IS | Mean # AF |

| 236 | 0.655 | 0.204 | 0.091 | 0.538 | 0.695 | 0.809 | 1 | 0.172 | 42 | 21.3 |

| POI quartile | # regions | Mean POI | SD POI | Mean # IS | Mean # AF | Mean total |

| Q1 (Low POI) | 59 | 0.368 | 0.139 | 24.8 | 37.9 | 62.7 |

| Q2 | 60 | 0.620 | 0.044 | 38.2 | 23.4 | 61.6 |

| Q3 | 58 | 0.762 | 0.031 | 48.2 | 15.0 | 63.2 |

| Q4 (High POI) | 59 | 0.871 | 0.048 | 57.2 | 8.6 | 65.8 |

| Dependent Variable | Coverage (fraction of IS+AF potential with substantial activity) |

| Specification | Coverage ~ Year + Region FE, clustered SE (n=235 regions) |

| Observations | 1,608 region-year pairs |

| Year coefficient (β) | 0.00142 (SE: 0.00124) |

| t-statistic | 1.143 |

| p-value | 0.254 |

| Within R² | 0.0012 |

| Adjusted R² | 0.248 |

| # regions | Metric | Mean | SD | Min | Q25 | Median | Q75 | Max |

| 182 | SCZBI | 0.231 | 0.399 | –1.000 | 0.000 | 0.232 | 0.500 | 1.000 |

| 182 | ER | 0.062 | 0.051 | 0.000 | 0.022 | 0.055 | 0.091 | 0.250 |

| 182 | ExR | 0.053 | 0.063 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.039 | 0.083 | 0.308 |

| 182 | SR | 0.403 | 0.293 | 0.000 | 0.186 | 0.375 | 0.571 | 1.000 |

| 182 | alignment | 0.102 | 0.103 | 0.000 | 0.007 | 0.078 | 0.160 | 0.365 |

| 182 | gap | 1.851 | 0.175 | 1.000 | 1.778 | 1.904 | 1.985 | 2.000 |

| 182 | OCI | 0.927 | 0.092 | 0.491 | 0.884 | 0.957 | 0.999 | 1.000 |

| archetype | # regions | Mean POI | Mean SCZBI | Mean ER | Mean ExR | Mean SR | Mean alignment | Mean gap | Mean # priorities |

| Strength Boosters | 67 | 0.833 | 0.536 | 0.063 | 0.033 | 0.367 | 0.121 | 1.855 | 6.209 |

| Excelling Perfectionists | 25 | 0.787 | 0.060 | 0.036 | 0.083 | 0.637 | 0.060 | 1.904 | 6.680 |

| Narrow Specialists | 24 | 0.560 | 0.553 | 0.083 | 0.025 | 0.253 | 0.169 | 1.806 | 5.208 |

| Explorers | 66 | 0.480 | –0.131 | 0.063 | 0.072 | 0.406 | 0.074 | 1.844 | 6.667 |

| term |

Model 1 ER |

Model 2 ExR |

Model 3 SR |

| (Intercept) | 0.245. (0.128) |

0.238 (0.178) |

2.280** (0.851) |

| POI | 0.012 (0.022) |

0.018 (0.03) |

0.146 (0.145) |

| SR | –0.062*** (0.012) |

–0.054** (0.016) |

n.a. |

| Legacy | 0.016 (0.013) |

-0.004 (0.018) |

0.233** (0.086) |

| Logarithm of GDP per capita (in purchasing power standard) | –0.019 (0.013) |

–0.020 (0.018) |

–0.203* (0.085) |

| Logarithm of population density | –0.006 (0.004) |

–0.004 (0.005) |

0.043 (0.027) |

| GERD (as % of GDP) | -–0.005 (0.003) |

–0.01* (0.005) |

0.017 (0.022) |

| Share of fossil fuels (country level) | 0.001* (0.000) |

0.001** (0.000) |

–0.005** (0.002) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).