1. Introduction

The synthesis of REBa

2Cu

3O

7−δ (RE123) ceramic superconductors has attracted considerable interest due to their promising electrical and magnetic properties [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Various synthesis methods have been employed, including the conventional solid-state reaction (SSR) [

4], pulsed laser deposition (PLD) [

9], co-precipitation (COP) [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15], and chemically modified photosensitive techniques [

16,

17]. The SSR method typically uses high-purity oxides and carbonates as precursors, involving multiple grinding steps and extended heat treatments to ensure complete reaction. However, this approach can introduce contamination during processing [

18,

19,

20]. In contrast, the COP method offers advantages by employing nanoscale precursors, reducing the need for prolonged sintering and grinding [

21,

22,

23,

24].

Among rare-earth RE123 compounds, gadolinium-based GdBa

2Cu

3O

7−δ (Gd123) exhibits an orthorhombic crystal structure at low oxygen deficiency (δ < 0.6) and a critical temperature (TC) exceeding 90 K [

7]. The presence of secondary phases such as Gd

2BaCuO

5 (Gd211) has been reported to enhance transport properties by acting as flux pinning centers [

8].

Previous studies have established that sintering time affects Gd123 superconducting performance, with an optimal duration of 15 hours at 920 °C identified [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Nonetheless, how changes in sintering temperature affect the superconducting and transport properties of Gd123 produced by COP has not been thoroughly investigated.

This study examines how sintering temperature affects phase formation, microstructure, and transport properties in Gd123 ceramics made by coprecipitation. Analyses included XRD, TGA, DC electrical resistance tests, and SEM.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Materials

Gadolinium(III) acetate tetrahydrate {Gd(CH3COO)3. 4H2O}, barium acetate {Ba(CH3COO)2}, and Copper(II) acetate monohydrate {Cu(CH3COO)2.H2O}, were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, supplied with a purity greater than 98%, and used as received. Oxalic acid (C₂H₂O₄), isopropanol (C3H8O), and distilled water were used as required.

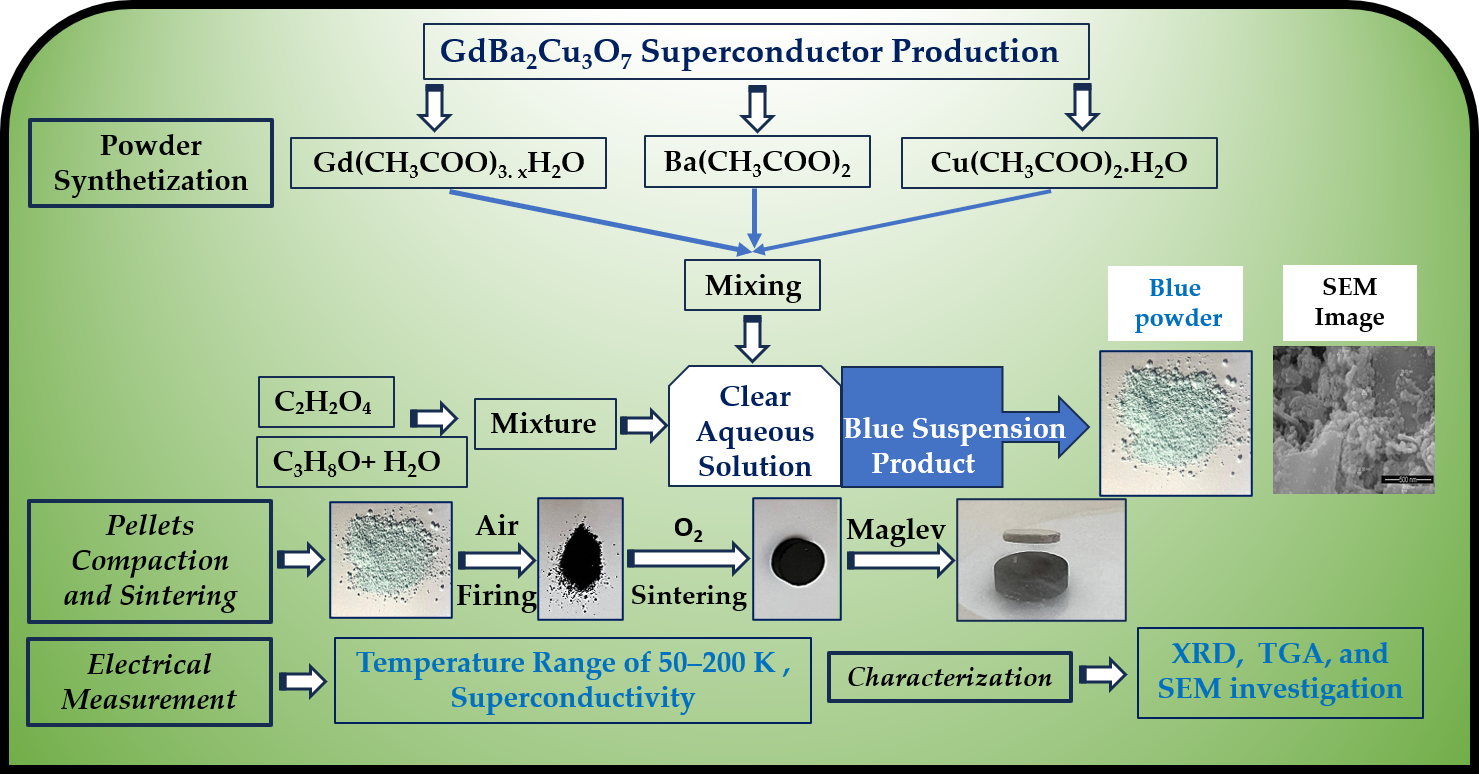

2.2. Superconductor Powder Synthetization

A clear aqueous solution of a mixture of 6.92 mmol Gd(CH

3COO)

3.4H

2O, 13.85 mmol Ba(CH

3COO)

2, and 20.78 mmol Cu(CH

3COO)

2.H

2O was prepared, and then 300 mL of 0.5 M oxalic acid and a 1.5 isopropanol: 1 water mixture were added for superconductor powder synthesis (

Figure 1). The result was a stable blue suspension product that was separated and dried overnight, gaining a blue powder, as reported in the ref. [

11]. The reaction equations are as follows:

2.3. Compaction and Sintering

The blue powder obtained was heated at 900 °C for 12 hours in a muffle furnace (Nabertherm, Germany), then cooled to room temperature at a rate of 2 °C per minute. After calcination, the powder was ground for 10 minutes using an agate mortar and pestle, then pressed into pellets about 1.25 cm in diameter with a Carver pressing machine (USA) at a compaction pressure of 300 MPa. These pellets were sintered at 920, 930, 940, and 950 °C under an oxygen flow of 5 mL/min for 15 hours in a tube furnace (Nabertherm, Germany), followed by slow cooling to room temperature at a rate of 1 °C per minute.

2.4. Electrical Resistance Measurement

Electrical resistance measurements for the sintered pellets were conducted over a temperature range of 50–200 K using a standard four-probe method. A direct current (DC) of 30 mA was applied, and the experiments were carried out in a closed-cycle refrigerator system model ARS-EA202A (USA).

2.5. Characterization

Some of the sintered pellets were milled, and their powders were examined using X-ray powder diffraction (Malvern Panalytical, Aeris, monochromatic Cu kα1, 1.5406 Å, 0.02 step angle, with 2θ ranging from 4° to 60°, Almelo, The Netherlands) for phase and unit cell investigation. TGA analysis of the synthesized blue powder was performed on a Netzsch STA 409 PG/PC thermal analyzer (Selb, Bavaria, Germany) to determine weight loss as a function of temperature. SEM (FEI QUANTA 200, Netherlands) and (Hitachi S 3400 N, Japan) were employed for microstructural investigations of the produced blue superconductor powder and sintered pellets.

3. Results and Discussion

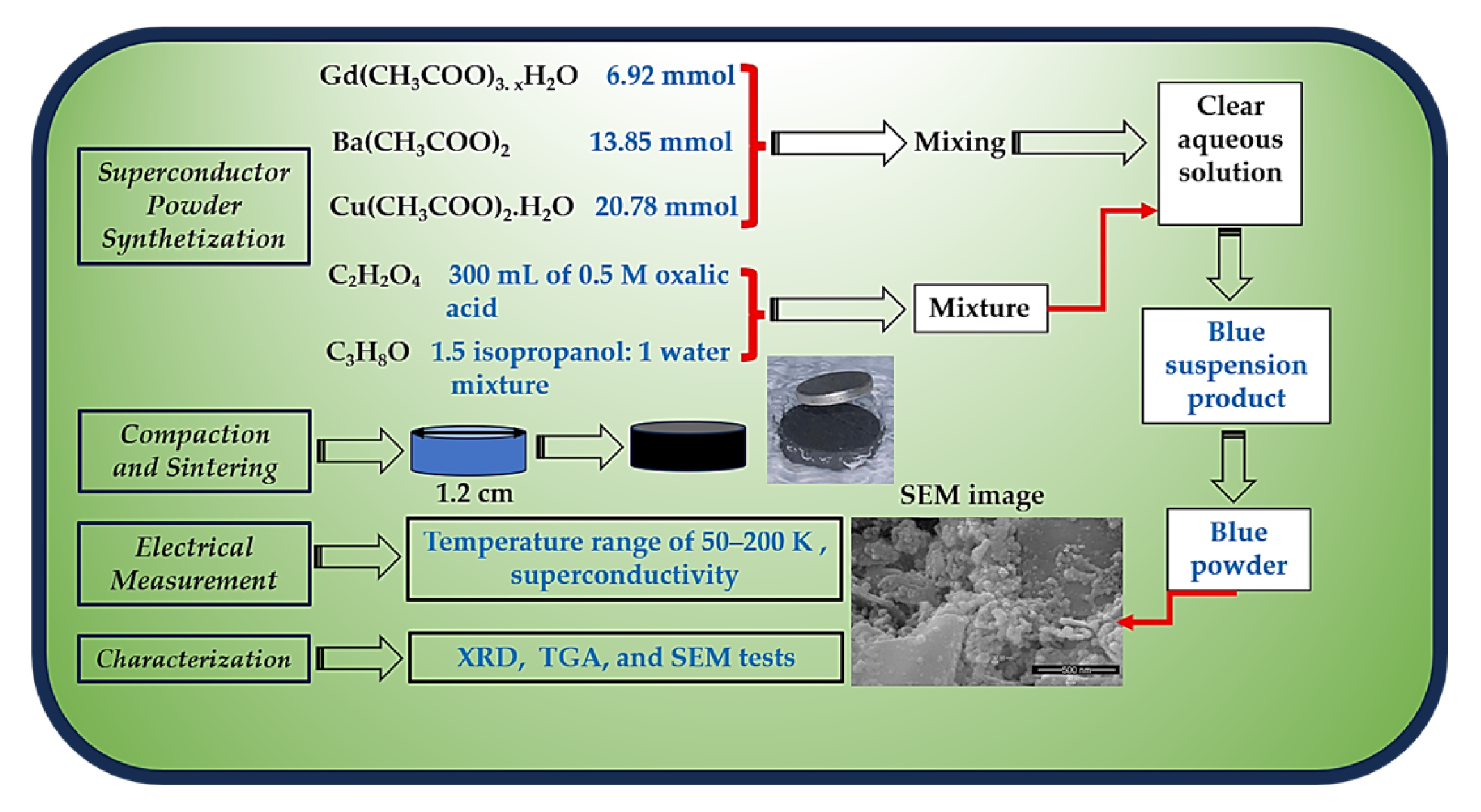

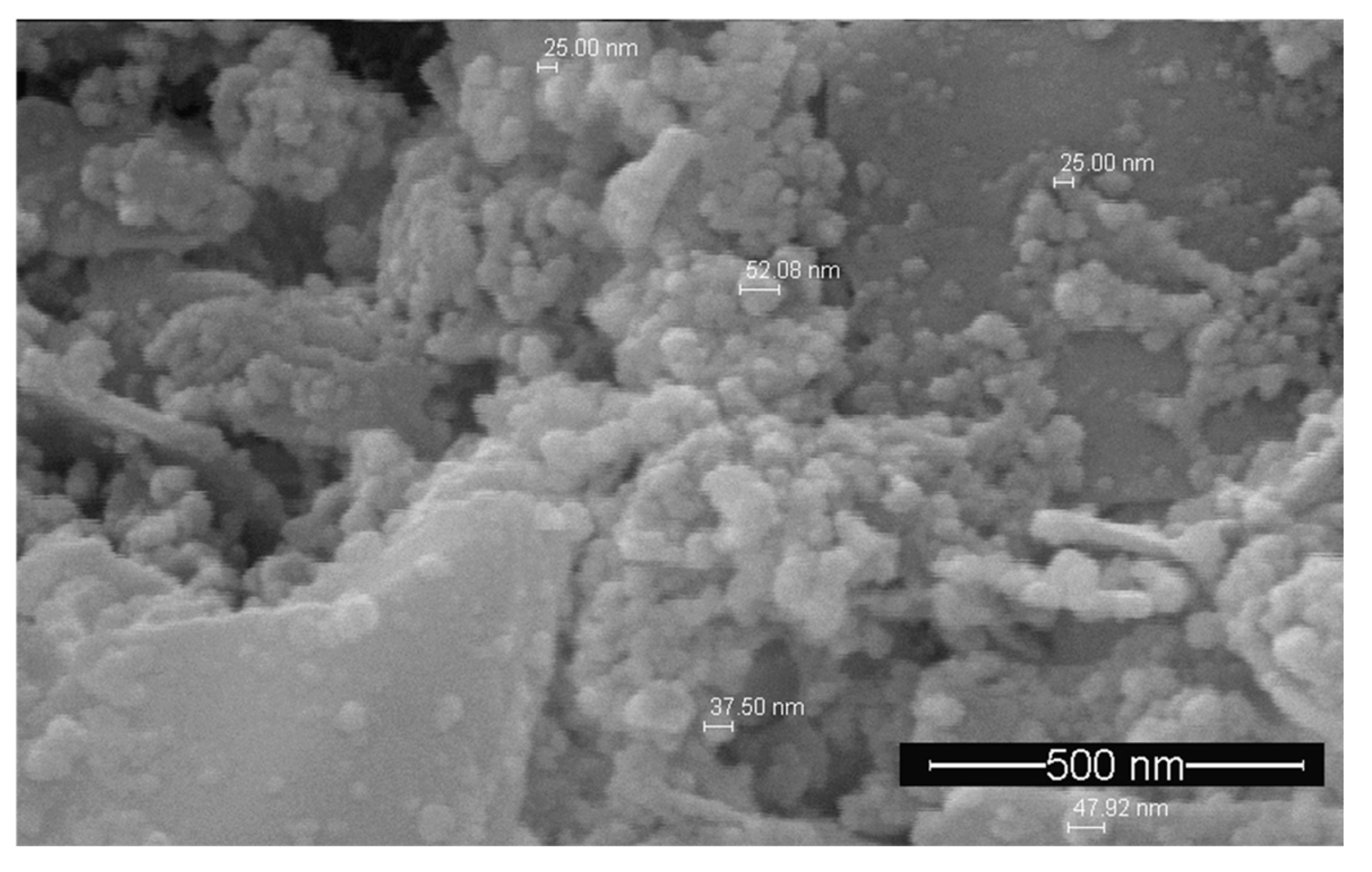

3.1. TGA Curve of The Produced Blue Nano-powder

The TGA curve showed five significant weight loss drops as a function of temperature, as illustrated in

Figure 2. The first drop was the moisture loss from the sample, which ended at approximately 125 °C. The second drop, occurring at 125-226 °C, represented the water loss due to crystallization from the metal oxalate mixtures. The third drop in weight at 226-293 °C could be due to the decomposition of CuC

2O

4, BaC

2O

4, and Gd

2(C

2O

4)

3.6H

2O into CuO, BaCO

3, and Gd

2(C

2O

4)

3. The fourth drop is associated with the decomposition of Gd

2(C

2O

4)

3to Gd

2O

3, and formation of BaCuO

2 and which agrees with previous reports [24, 25]. The final drop shows a complete decomposition and the formation of GdBa

2Cu

3O

7- that begins at 900 °C, as indicated in

Table 1. Therefore, from the TGA thermogram, it can be concluded that the suitable calcination and sintering temperatures for Gd123 are in the range of 900-950 °C

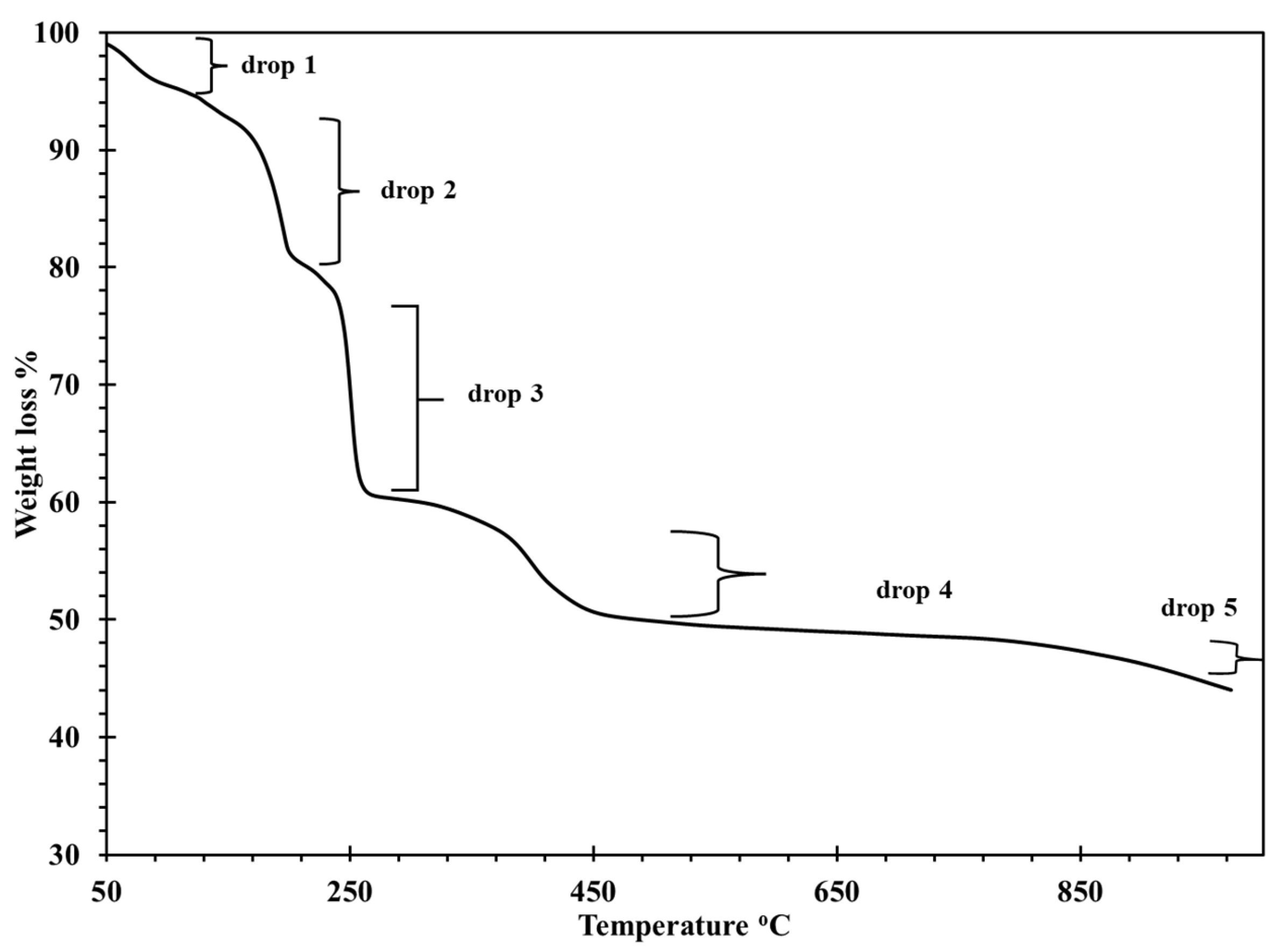

3.2. Microstructure of The Produced Powder and Sintered Pellets

The SEM image of the produced blue powder confirms the precipitation of nanoparticles, as shown in

Figure 3. The image reveals the agglomeration state of the nanoscale particles, which is a probable result because of the mutual diffusion between particles during the precipitation process, in the absence of any capping substance. The particle size is within the range of 50 nm or less.

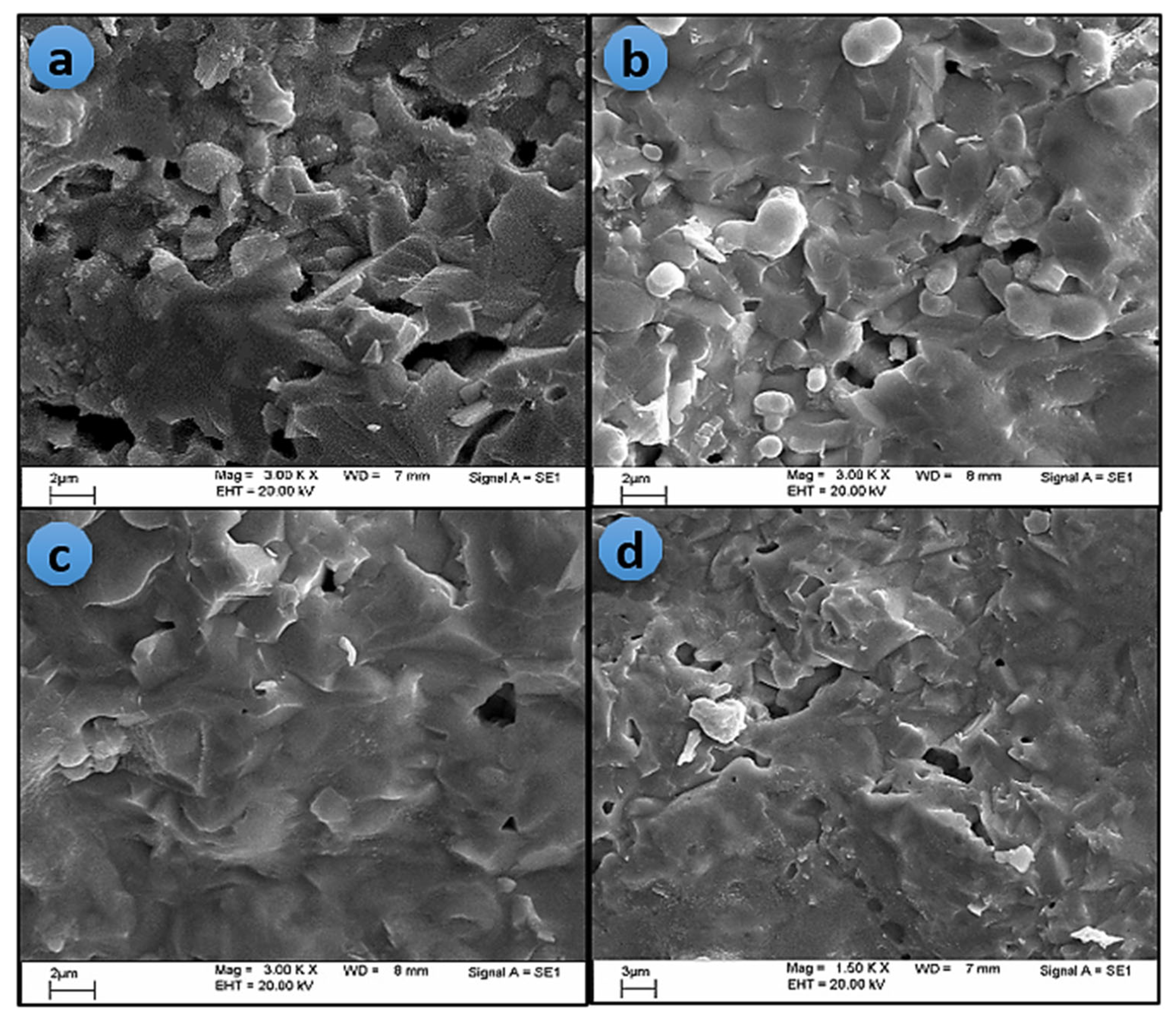

All sintered pellets exhibited large, highly compacted grains with melt-like structures, as demonstrated in

Figure 4. In addition, the grains become closer and more coherent as the sintering temperature increases, thus improving the sintering density as a common result, which is in good agreement with the porosity and relative density measurements recorded in

Table 3.

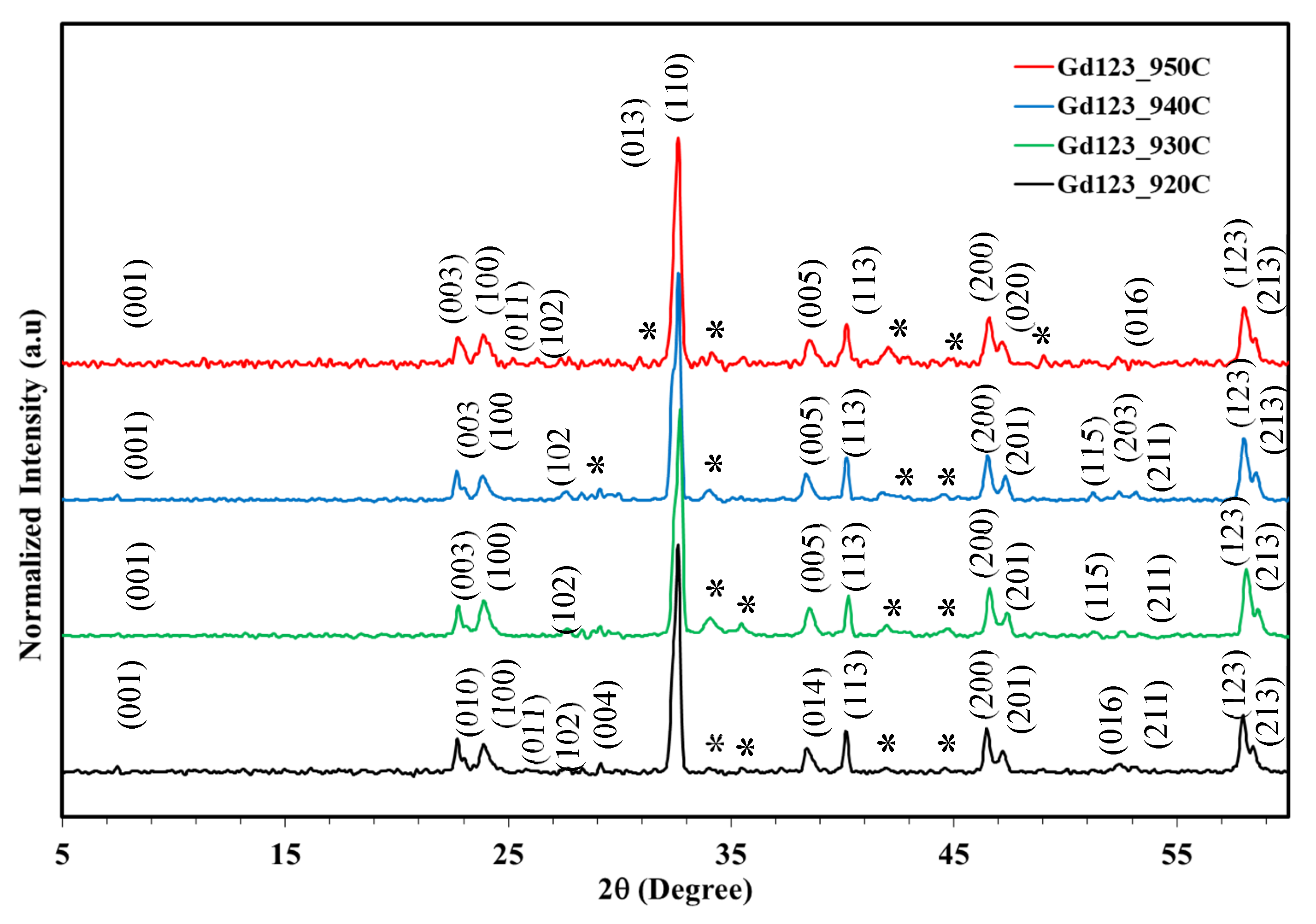

3.2. XRD Results

Figure 5 presents XRD patterns for sintered Gd123 at temperatures ranging from 920°C to 950°C. The dominant phase of the orthorhombic structure (Gd123) is presented for all samples. This phase was identified and labeled as (h k l) planes and the perovskite structure with the space group of Pmmm, No. 47, Z = 1, α = β = γ = 90°. The measured lattice parameters for all samples match the standard (JCPDS, # 01-089-5733) listed in

Table 2. Few peaks belonging to impurities at 28.42°, 29.27°, 30.08°, 35.68°, 39.99°, 41.87°, 42.54°, and 49.27° were also detected and belonged to the non-superconducting phases, such as BaCuO

2 (Gd011) and Gd

2BaCuO

5 (Gd211).

GdBa2Cu3O7−δ "Gd123%" phase contents for samples sintered at 920 °C, 930 °C, 940 °C, and 950 °C were 92.5%, 99.1%, 99.5%, and 99.8%, respectively. Impurities at 920 °C result from incomplete sintering, while 930–950 °C yields high Gd123 purity.

Table 2.

Lattice parameters and volume for all sintered samples .

Table 2.

Lattice parameters and volume for all sintered samples .

Sintering

(oC) |

a (Å) |

b (Å) |

c (Å) |

Volume (Å) |

| 920 |

3.849 + 0.001 |

3.901 + 0.001 |

11.718 + 0.002 |

175.92+ 0.02 |

| 930 |

3.846 + 0.001 |

3.902 + 0.001 |

11.716 + 0.001 |

175.80+ 0.03 |

| 940 |

3.842 + 0.001 |

3.903 + 0.001 |

11.722 + 0.001 |

175.81+ 0.02 |

| 950 |

3.843 + 0.001 |

3.904 + 0.001 |

11.723 + 0.001 |

175.85+ 0.02 |

The Gd123% was calculated using the following Equation (1) [

11]:

where I

123 and I

mpurities are the peak intensities of the observed phases for Gd 123 and impurities.

3.4. Electrical Measurements

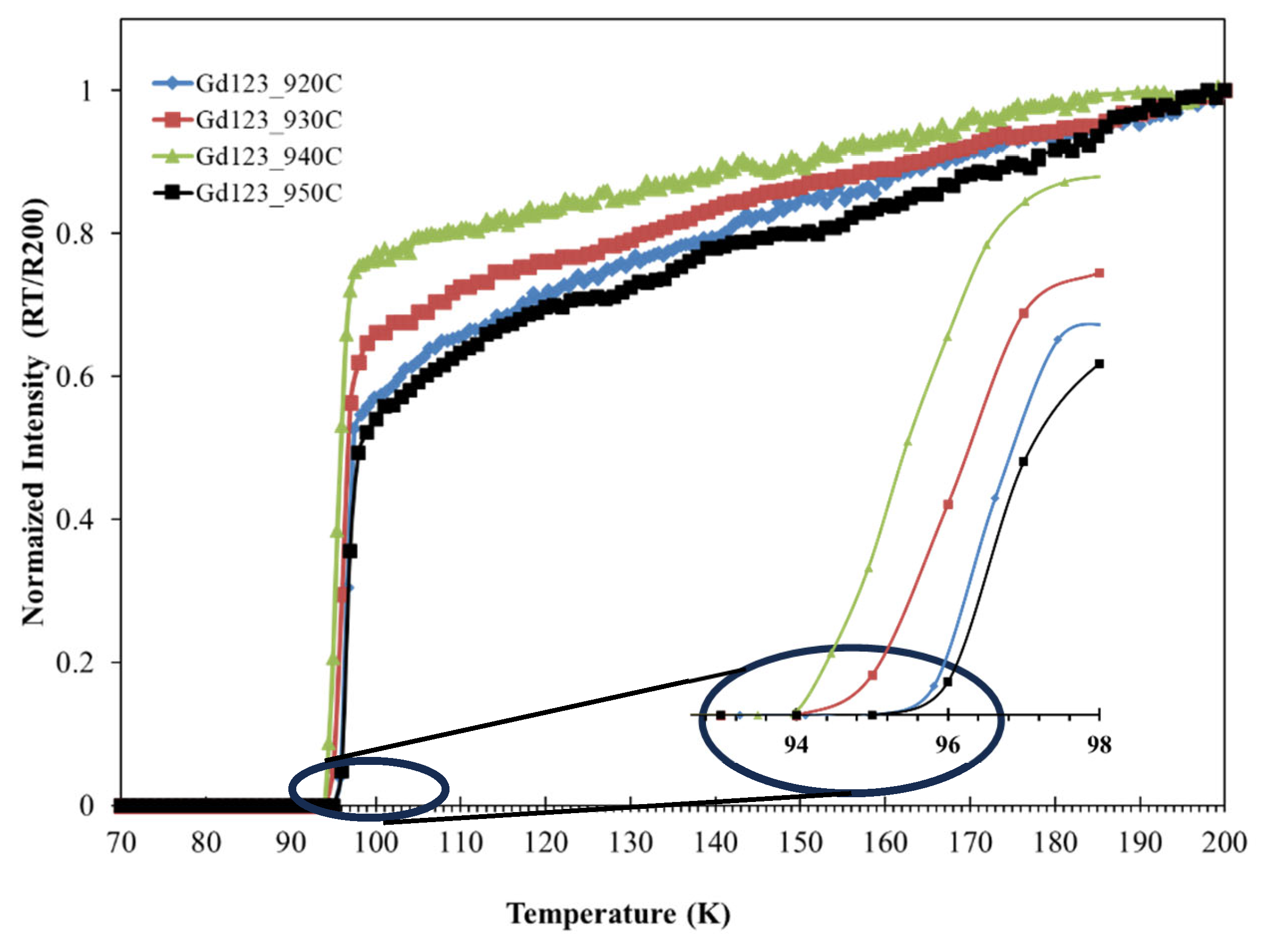

The normalized electrical resistance as a function of temperature, in the absence of a magnetic field, was measured for all sintered samples and showed normal metallic behavior with a single-drop transition feature, as shown in

Figure 6. All sintered samples showed a zero-resistance temperature (T

C, R=0) of 94–95 K, with no notable changes as the sintering temperature increased.

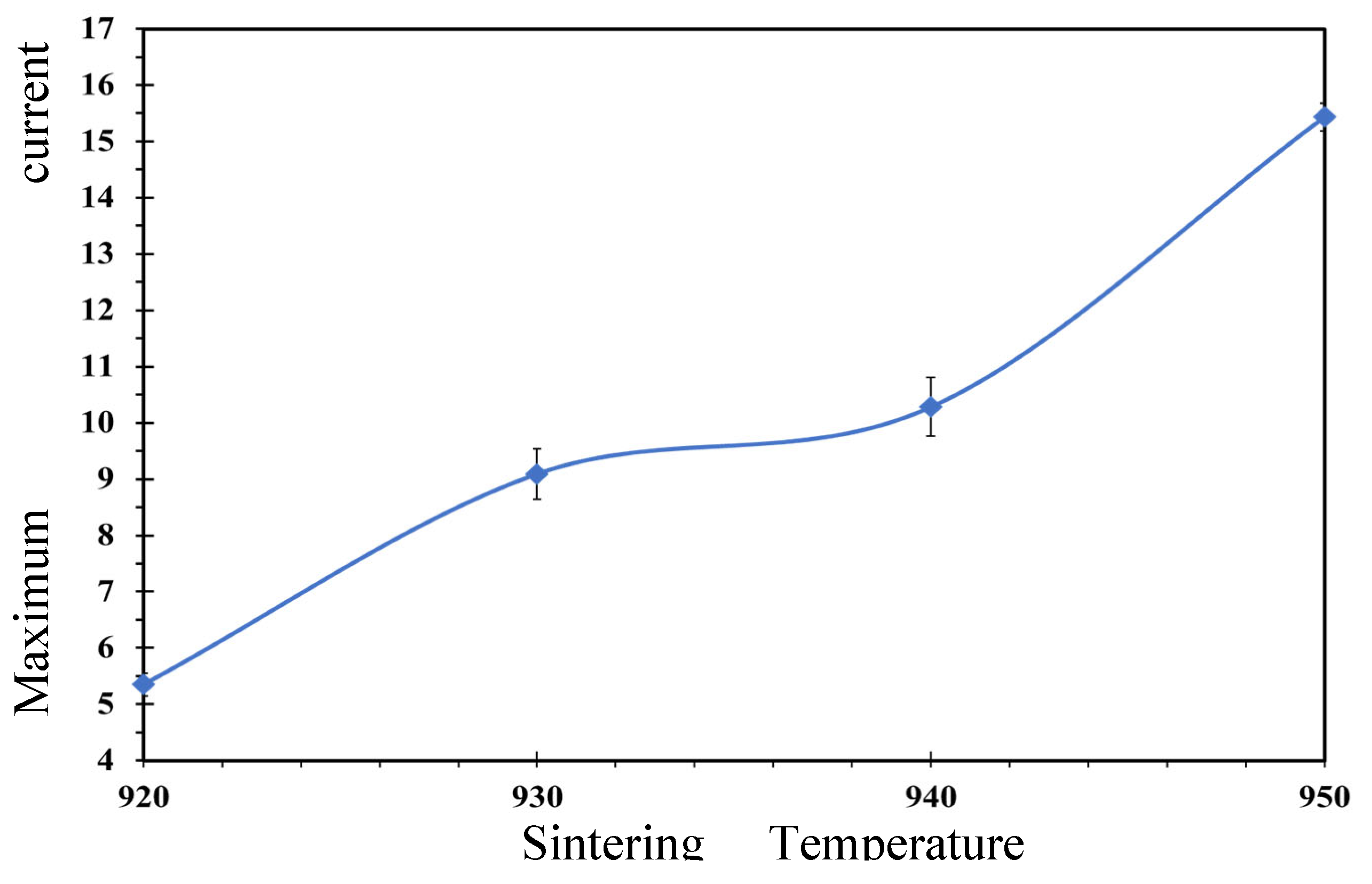

The transport critical current density,

JC, was calculated using Eq. (2):[

13]

where

IC represents the maximum current (A) through the sample's cross-sectional area (cm²) before superconductivity is lost at 77 K and zer

o magnetic field.

Figure 7 presents JC values of 4.35 ± 0.11, 6.35 ± 0.43, 7.89 ± 0.71, and 12.9 ± 0.89 A/cm² for samples treated at 920, 930, 940, and 950 °C, respectively.

The

JC values presented in

Table 3 (section 3.4) increased with higher sintering temperatures, attributed to a reduction in weak link formation at grain boundaries, thereby facilitating improved current flow. Additionally, the small quantity of 211 phases identified within the 123 superconducting system contributed positively to transport properties, as corroborated by XRD data (which indicates these phases are not superconductors). These 211 phases serve as flux pinning centers and may enhance current flow between grains, as discussed in references [15, 16, 25].

3.5. Relative Density and Porosity

The relative density (Drelative %) and the porosity for all samples were calculated from the actual and theoretical densities using the following equations (3 & 4):

where the relative density of sample D

Relative is given by the percentage ratio of the density

sample, obtained for the bulk samples, to theoretical density ρ

theoretical obtained from the XRD data (

Table 3). Increasing the relative density of ceramics plays a pivotal role in improving their critical current density. This enhancement is primarily attributed to the reduction of insulating cavities within the material, which facilitates better current flow between the grains.

Table 3.

Summarized data of TC(R=0) (K), TC-onset (K), Gd123%, relative density, porosity and the maximum current density ( Jc) of superconducting GdBa2Cu3O7.

Table 3.

Summarized data of TC(R=0) (K), TC-onset (K), Gd123%, relative density, porosity and the maximum current density ( Jc) of superconducting GdBa2Cu3O7.

| Sintering (oC) |

TC(R=0)

|

TC (onset)

|

Impurities % |

Relative Density % |

Porosity % |

Jc

(A/cm2) |

| 920 |

95 |

97 |

3.8 |

80.3 |

19.7 |

4.4+0.1 |

| 930 |

94 |

97 |

0.9 |

83.2 |

16.8 |

6.4+0.4 |

| 940 |

94 |

96 |

1.8 |

89.9 |

10.2 |

7.9+0.7 |

| 950 |

95 |

97 |

2.2 |

95.3 |

4.7 |

12.9+0.9 |

4. Conclusions

GdBa₂Cu₃O₇−δ superconducting ceramics were synthesized from nanoscale metal-oxalate precursors via co-precipitation, followed by sintering at temperatures ranging from 920 °C to 950 °C Elevated sintering temperatures resulted in an increase of the orthorhombic Gd123 phase fraction from 92% to 99.8%. Electrical measurements demonstrated metallic characteristics, with (Tc, R=0) consistently observed between 94 and 95 K.

Both XRD and SEM analyses show that raising the sintering temperature improves the critical current density. According to XRD patterns, small amounts of secondary phases are present, which can serve as efficient flux-pinning centers. Meanwhile, SEM images demonstrate that higher temperatures progressively decrease the gaps and voids between superconducting grains. This reduction in insulating cavities strengthens intergranular coupling and increases the material's relative density, resulting in better current transport efficiency.

Overall, these findings demonstrate that careful optimization of sintering temperature can significantly enhance the microstructure and transport properties of Gd123 ceramics, offering valuable guidance for their development in large-scale electrical and magnetic applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptual: Ahmed Al-Mobydeen and Imad Hamadneh; methodology: Mohammed M Alawamleh.; software: Imad Hamadneh and Jamal Rahhal; validation: Yousef Al-Dalahmeh, Sondos Shamah and Jamal Rahhal; formal analysis: Wala`a Al-Tarawneh and Sondos Shamah; investigation: Mohammed M Alawamleh and Ahmed Al-Mobydeen.; data curation: Imad Hamadneh.; writing—original draft preparation: Imad Hamadneh.; writing—review and editing: Iessa Sabbe Moosa and Ehab AlShamaileh.; visualization: Iessa Sabbe Moosa, Ehab AlShamaileh and, Mike Haddad; supervision, Imad Hamadneh.; project administration: Imad Hamadneh.; funding acquisition: Imad Hamadneh. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Dean of Scientific Research at the University of Jordan (grant No. 2490).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Takao, T.; Kameyama, S.; Doi, T.; Tanoue, N.; and Kamijo, H. Increase of Levitation Properties on Magnetic Levitation System Using Magnetic Shielding Effect of GdBCO Bulk Superconductor. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2011, 21, 1543–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krekels, T.; Zou, H.; Van Tendeloo, G.; Wagener, D.; Buchgeister, M.; Hosseini, S. M.; and Herzog, P. Ortho II Structure in ABa2Cu3O7−δ Compounds (A = Er, Nd, Pr, Sm, Yb). Physica C 1992, 196, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, J. D.; Hinks, D. G.; Radaelli, P. G.; Pei, S.; Lightfoot, P.; Dabrowski, B.; Segre, C. U.; and Hunter, B. A. Defects, Defect Ordering, Structural Coherence, and Superconductivity in the 123 Copper Oxides. Physica C 1991, 185–189, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchgeister, M.; Herzog, P.; Hosseini, S. M.; Kopitzki, K.; and Wagener, D. Oxygen Evolution from ABa2Cu3O7−δ High-Tc Superconductors with A = Yb, Er, Y, Gd, Eu, Sm, Nd, and La. Physica C 1991, 178, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plackowski, T.; Sułkowski, C.; Włosewicz, D.; and Wnuk, J. Effect of the RE3+ Ionic Size on the REBa2Cu3O7−δ Ceramics Oxygenated at 250 Bar. Physica C 1998, 300, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, R.; Vijayaraghavan, R.; Ganapathi, L.; Mohan Ram, R. A.; and Rao, C. N. R. Evidence for Two Distinct Orthorhombic Structures Associated with Different Tc Regimes in LnBa2Cu3O7−δ (Ln = Nd, Eu, Gd, and Dy): A Study of the Dependence of Superconductivity on Oxygen Stoichiometry. Physica C 1989, 158, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Lee, M.; Ann, H.; Choi, Y. H.; and Lee, H. A Superconducting Joint for GdBa2Cu3O7−δ-Coated Conductors. NPG Asia Mater. 2014, 6, e98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masi, A.; Freda, R.; Formichetti, A.; Greco, A.; Alimenti, A.; Khan, M. R.; and Celentano, G. High Current Measurement of Commercial REBCO Tapes in Liquid Helium: Experimental Challenges and Solutions. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 7697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Kim, C. J.; Choi, S. M.; Yoo, S. I.; and Shin, K. M. TEM Analysis of the Interfacial Defects in the Superconducting GdBa2Cu3O7−δ Tapes Synthesized by IBAD-PLD. Physica C 2007, 463–465, 722–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadneh, I. The Influence of Heat Treatment on the Formation and Transport Current Density of DyBa2Cu3O7−δ Ceramics Superconductor Synthesized from Nano-Coprecipitated Powders. Electron. Mater. Lett. 2014, 10, 597–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadneh, I.; Ahmad, A. M.; and Hamadneh, L. Effect of Heat Treatment of HoBa2Cu3O7−δ Ceramics Superconductor Synthesized from Nano-Coprecipitated Powders. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2013, 27, 1350118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadneh, I.; Ahmad, A. M.; Wahid, M. H.; Zainal, Z.; and Abd-Shukor, R. Effect of Nano-Sized Oxalate Precursor on the Formation of GdBa2Cu3O7−δ Phase via Coprecipitation Method. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2009, 23, 2063–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadneh, I.; Halim, S. A.; and Lee, C. K. Characterization of Bi1.6Pb0.4Sr2Ca2Cu3Oy Ceramic Superconductor Prepared via Coprecipitation Method at Different Sintering Times. J. Mater. Sci. 2006, 41, 5526–5530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadneh, I.; Khalili, F.; Shaaer, M.; and Rosli, A. M. Effect of Nano Sized Oxalate Precursor on the Formation of RE-Ba2Cu3O7−δ (RE = Gd, Sm, Ho) Ceramic via Coprecipitation Method. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2010, 234, 012016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadneh, I.; Yaseen, N.; Abdallat, Y.; Hamadneh, L.; and Tarawneh, O. The Sintering Effect on the Phase Formation and Transport Current Properties of SmBa2Cu3O7−δ Ceramic Prepared from Nano-Coprecipitated Precursors. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2016, 29, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Liu, C.; Guo, M.; Han, Y.; Ren, Y.; Liu, D.; and Zhao, G. Fabrication of GdBa2Cu3O7−δ Fine Patterns by “Chemically Modified Self-Photosensitive” Photolithography. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 27503–27510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimouni, M.; Bayou, S.; Zeroual, S.; Hamadneh, I.; Mahboub, M. S.; Ramdani, S.; Rihia, G.; and Ghougali, M. S. Synthesis and Characterization of Bulk Bi-2212 Superconducting Ceramic Using Photopolymerization Reaction-Based Method. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2022, 35, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamadneh, I.; Abdullah, I.; Halim, S. A.; and Abd-Shukor, R. Dynamic Magnetic Properties of Superconductor/Polymer NdBCO/PVC Composites. J. Mater. Sci. Lett. 2002, 21, 1615–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarudin, M. F.; Zainal, Z.; and Hamadneh, I. Synthesis of ErBa2Cu3O7−δ Superconducting Ceramic Material via Coprecipitation and Conventional Solid State Routes. J. Mater. Environ. Sci. 2015, 6, 359–365. [Google Scholar]

- Yahya, A. K.; Hamid, N. A.; Abd-Shukor, R.; and Imad, H. Anomalous Elastic Response of HoBa2−xHoxCu3O7−δ Ceramic Superconductors. Ceram. Int. 2004, 30, 1597–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujaini, M.; Yahya, S. Y.; Hamadneh, I.; and Shukor, R. A. Synthesis of YBa2Cu3O7−δ High Temperature Superconductor by Coprecipitation Method. AIP Conf. Proc. 2008, 1023, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarudin, M. F.; Hamadneh, I.; Tan, W. T.; and Zainal, Z. The Effect of Sintering Temperature Variation on the Superconducting Properties of ErBa2Cu3O7−δ Superconductor Prepared via Coprecipitation Method. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2011, 24, 1745–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, M. H.; Zainal, Z.; Hamadneh, I.; Tan, K. B.; Halim, S. A.; Rosli, A. M.; Alaghbari, E. S.; Nazarudin, M. F.; and Kadri, E. F. Phase Formation of REBa2Cu3O7−δ (RE: Y0.5Gd0.5, Y0.5Nd0.5, Nd0.5Gd0.5) Superconductors from Nanopowders Synthesized via Coprecipitation. Ceram. Int. 2012, 38, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibille, R.; Didelot, E.; Mazet, T.; Malaman, B.; and François, M. Magnetocaloric Effect in Gadolinium-Oxalate Framework Gd2(C2O4)3(H2O)6·(0.6H2O). APL Mater. 2014, 2, 124402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maimaiti, N.; Abulaiti, A.; Yang, W. The Effect of Infiltration Temperature on the Microstructure and Magnetic Levitation Force of Single-Domain YBa2Cu3O7-x Bulk Superconductors Grown by a Modified Y+011 IG Method. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).