1. Introduction

Reproductive technologies play a key role in enhancing both productivity and genetic improvement, contributing to long-term economic sustainability and the conservation of indigenous breeds. Among these technologies,

in vitro embryo production (IVEP) has become particularly valuable, consisting of sequential procedures beginning with oocyte retrieval and followed by

in vitro maturation (IVM), fertilization (IVF), and culture (IVC) to generate embryos suitable for transfer or cryopreservation [

1]. The developmental potential of oocytes is influenced by numerous intrinsic and extrinsic factors, including donor physiology, nutritional status, and environmental conditions such as ambient temperature and photoperiod, which can modulate follicular dynamics and oocyte competence [

2]. In addition to these factors, oxidative stress represents a major threat to oocyte quality. Excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) can disrupt maturation and compromise early embryogenesis during both pre-culture handling and subsequent

in vitro culture phases [

3]. These ROS induce oxidative damage through protein and DNA oxidation, lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and developmental arrest [

4].

Under physiological conditions, oocytes develop within a finely regulated follicular microenvironment in which ROS and antioxidant defenses maintain a delicate redox balance [

5]. Disruption of this balance such as during ovary collection, transportation, temperature fluctuation [

6], or post-mortem ischemia, can lead to excessive ROS accumulation before IVM, leaving oocytes highly vulnerable at an early stage [

7]. Oocytes retrieved for IVM may already possess compromised antioxidant capacity due to intrinsic follicular factors, including mitochondrial activity, metabolic demands, and the limited stores of enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants in both the oocyte and its surrounding cumulus cells [

5]. Agarwal et al. [

8] similarly highlighted that the laboratory environment in assisted reproductive technologies inherently predisposes gametes to ROS overproduction, often even before oocyte maturation begins. Collectively, these findings indicate that the period prior to IVM represents a particularly sensitive window during which unmanaged oxidative stress can impair meiotic progression, cytoskeletal integrity, and subsequent developmental competence. ROS production can then persist throughout the

in vitro culture period, starting approximately 4 hours after IVM and peaking after 12 h of culture [

9]. This increase coincides with the oocyte’s heightened adenosine triphosphate (ATP) demand during critical processes, such as spindle formation, chromosome segregation, and cell division [

10]. In cellular systems, excessive ROS initiates lipid peroxidation, leading to the formation of reactive aldehydes such as malondialdehyde (MDA). MDA, a stable end-product of lipid peroxidation, is widely used as a biochemical marker of oxidative stress across mammalian cell systems [

11].

To mitigate oxidative damage, the use of biomolecules with antioxidant properties has gained significant interest for improving oocyte quality. Sericin, a silk-derived protein from

Bombyx mori, has attracted attention due to its high biocompatibility and strong antioxidant capacity [

12]. Supplementation of culture media with sericin has shown to stimulate collagen production, and promote cell proliferation and adhesion [

13]. Growing evidence further supports its application in reproductive systems, supplementing maturation media with 0.05% sericin enhances meiotic progression, reduces intracellular hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) accumulation, and decreases DNA fragmentation in oocytes exposed to oxidative stress [

14]. Satrio et al. [

15] reported that supplementation with 0.1% sericin in both collection and maturation media improved oocyte maturation. In embryos, sericin has also been shown to promote pre-implantation development and reduce ROS-induced DNA damage, particularly under experimentally induced oxidative stress, as demonstrated in bovine embryos cultured individually [

16].

Although several studies have examined the effects of oxidative stress and antioxidants during the IVM phase, information regarding their impact prior to IVM remains limited. Oocytes are often exposed to oxidative stress immediately after ovary collection. A recent study demonstrated that short-term exposure to 100 µM H₂O₂ for 1 h provides a reliable and physiologically relevant model for inducing oxidative stress in bovine oocytes before IVM, offering a standardized platform for evaluating antioxidant interventions [

17]. Building upon this model, the present study aimed to evaluate the protective role of sericin supplementation during the pre-IVM phases against H₂O₂ -induced oxidative stress in bovine oocytes. Unlike earlier studies that primarily explored sericin as a serum substitute, this study focuses on its role as an active antioxidant supplement in conventional culture media. The sericin concentration used during IVM was selected based on previous findings demonstrating that this dosage optimizes meiotic progression and reduces intracellular ROS levels without causing cytotoxic effects [

14,

15,

16], making it an appropriate and physiologically safe concentration for improving oocyte competence under oxidative stress conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ovaries Collection and Handling

The oocytes used in this study were collected from ovaries of intact mature female cattle slaughtered at three slaughterhouses in Nakhon Pathom province. Oocyte collection was conducted between June and September 2025. Bovine ovaries were transported to the laboratory within 2 h of collection and maintained at 30–35°C in 0.9% NaCl supplemented with 100 IU/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin sulfate (HyClone™, Logan, UT, USA) during transport to minimize microbial contamination.

2.2. Cumulus-Oocyte Complexes Recovery and Selection

Upon arrival at the laboratory, the ovaries were washed three times with pre-warmed (37°C) transport medium. Cumulus–oocyte complexes (COCs) were then aspirated from follicles measuring 2-5 mm in diameter using an 18-gauge needle attached to a 10-mL disposable syringe. Only grade 1 and grade 2 COCs, characterized according to the morphological criteria established by the International Embryo Technology Society (IETS) were selected for further processing.

2.3. Induction of Oxidative Stress and Grouping

Before IVM, COCs were randomly assigned into three experimental groups: control, –SC (without sericin-supplemented), and +SC (sericin-supplemented). Each treatment group was conducted in five independent replicates, using oocytes collected from different ovaries for each replicate. All groups were transferred using a mouth pipette into a collecting medium consisting of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone™, Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA), 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (HyClone™, Cytiva, USA).

For the –SC and +SC groups, H₂O₂ (H₂O₂; 30% w/w analytical grade, ACS reagent, Fisher Scientific, USA) was freshly added to the collecting medium to achieve a final concentration of 100 µM, and the COCs were incubated at 38.5 °C for 1 h to induce oxidative stress. The +SC group additionally received 0.1% (w/v) sericin (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) in the collecting medium. The control group was handled identically but without H₂O₂ or sericin treatment.

2.4. In Vitro Maturation

After oxidative stress induction, all COCs were washed three times and transferred to maturation medium. The +SC group continued to receive 0.05% (w/v) sericin supplementation during in vitro maturation, while the control and –SC groups were cultured in standard medium without sericin. Selected COCs were placed into 50 µL drops of maturation medium at a density of 10 oocytes per drop. The oocytes were then cultured at 38.5 °C under a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO₂ in air for 23 h. The maturation medium was based on Medium-199 (M-199; Cytiva, USA) supplemented with 10 IU/mL follicle-stimulating hormone (Folligon; Intervet, Boxmeer, Netherlands), 10 IU/mL human chorionic gonadotropin (Chorulon; Intervet, Netherlands), 100 IU/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin sulfate. For the sericin-supplemented group, 0.05% (w/v) sericin was added in the medium. All maturation media were pre-equilibrated for 2 h in a humidified CO₂ incubator prior to use.

2.5. Aceto-Orcein Staining

Following incubation, cumulus cells were removed by repeated pipetting in PBS containing 0.25% hyaluronidase (Medchem Express, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA). The denuded oocytes were then fixed in methanol: acetic acid (1:3 v/v) for 48 h. After fixation, oocytes were stained with 2% aceto-orcein (prepared in 45% acetic acid) for 10 min. The nuclear maturation stage of each oocyte was subsequent assessed under a phase-contrast microscope (Olympus CX22LED, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) at 400× total magnification.

2.6. TBARS (Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances)

Intracellular malondialdehyde (MDA) was quantified using a thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) assay. For each experimental group, 100 bovine COCs were pooled and processed together as a single biological sample, with the procedure was repeated in three independent replicates. A 30 µL homogenate was mixed with 50 µL of glacial acetic acid and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The samples were then centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 minutes. A 60 µL aliquot of the resulting supernatant was combined with 60 µL of 3.5 M sodium acetate buffer and 60 µL of 0.8% thiobarbituric acid (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The mixture was heated at 95 °C for 1 h, followed by incubation on ice for 30 minutes. Samples were then centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C. The resulting supernatant was measured for absorbance at 532 nm and compared against a standard curve generated using 1,1,3,3-tetraethoxypropane (Sigma Aldrich, USA).

2.7. Data Analysis

The normality of data distribution was assessed using both Shapiro–Wilk and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests. All variables met the assumption of normality (p > 0.05). Homogeneity of variance was verified using Levene’s test before conducting further analysis. Comparisons among treatment group means were performed using one-way ANOVA and multiple comparisons between group were evaluated using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test.

3. Results

3.1. Oocyte Maturation Assessment

The results showed that the oxidative stress group (–SC) had a significantly higher proportion of oocytes arrested at the GV and GVBD stages, as compared with both the control and sericin-supplemented (+SC) groups (p < 0.01), indicating meiotic arrest under oxidative stress conditions. Conversely, the percentage of oocytes reaching the MII stage was markedly reduced in the –SC group compared with both the control and +SC groups (

p < 0.001). No significant difference in the MII rate was observed between the control and +SC groups (

Table 1), suggesting that sericin supplementation effectively restored meiotic progression impaired by oxidative stress. These findings indicated that oxidative stress induced by 100 µM H₂O₂ prior to IVM significantly inhibited meiotic maturation, while sericin supplementation during both the pre-IVM and IVM phases mitigated oxidative damage and supported nuclear maturation to levels comparable with the control.

3.2. Measurement of TBARS Levels

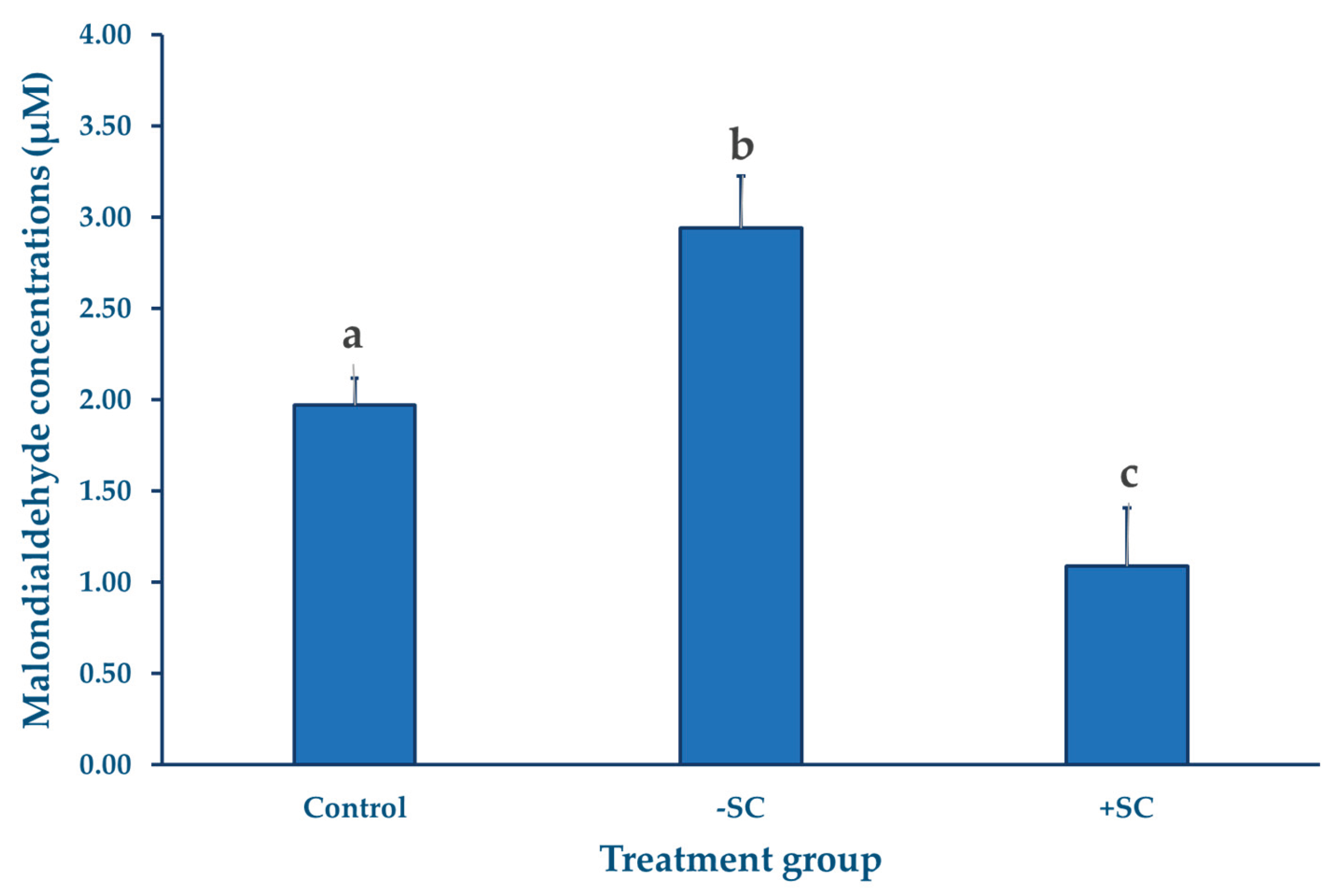

MDA levels were measured using the TBARS assay, as previously described, with three replicates performed for each group. The results showed that the H₂O₂-treated group exhibited the highest MDA concentration (2.94 ± 0.28 µM), indicating a pronounced increase in lipid peroxidation compared with the control group (1.97 ± 0.14 µM). In contrast, the sericin-supplemented group showed the lowest MDA level (1.09±0.32 µM). Statistical analysis revealed that MDA concentrations differed significantly among the three groups (p < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Intracellular malondialdehyde (MDA) concentrations (µM) in bovine oocytes following pre-IVM oxidative stress induction and subsequent in vitro maturation. Oocytes in the –SC and +SC groups were exposed to 100 µM H₂O₂ for 1 h prior to IVM, whereas the control group received no oxidative treatment. The +SC group also received sericin supplementation during both the pre-IVM (0.1%) and IVM (0.05%) phases. MDA levels were measured after 23 h of IVM using pooled samples of 100 oocytes per replicate (n = 3). Values are presented as means and the error bars are SD.

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Intracellular malondialdehyde (MDA) concentrations (µM) in bovine oocytes following pre-IVM oxidative stress induction and subsequent in vitro maturation. Oocytes in the –SC and +SC groups were exposed to 100 µM H₂O₂ for 1 h prior to IVM, whereas the control group received no oxidative treatment. The +SC group also received sericin supplementation during both the pre-IVM (0.1%) and IVM (0.05%) phases. MDA levels were measured after 23 h of IVM using pooled samples of 100 oocytes per replicate (n = 3). Values are presented as means and the error bars are SD.

4. Discussion

The oxidative stress induced by H₂O₂ before IVM markedly reduced oocyte quality, as shown by the decreased proportion of oocytes reaching the MII stage. Sericin supplementation restored nuclear maturation to levels comparable to or exceeding the control, confirming its protective role against oxidative stress and its capacity to promote meiotic progression. Overall, these findings indicated that sericin supplementation effectively counteracts pre-IVM oxidative stress, mimicking the physiological stress conditions that oocytes encounter following ovary collection.

The protective mechanism of sericin is thought to be related to its unique antioxidant properties. Sericin, a natural protein derived from the silkworm (

Bombyx mori), is rich in polar amino acids such as serine, aspartic acid, and glycine. These amino acids provide functional groups (–OH, –COOH, and –NH₂) capable of donating electrons or scavenge free radicals, thereby reducing oxidative reactions [

12]. This activity helps inhibit lipid peroxidation and minimize Fenton reactions that elevate intracellular ROS levels. Additionally, sericin exhibits cryoprotective properties, stabilizing proteins and cell membranes while maintaining moisture balance in culture systems [

18]. Collectively, these characteristics protected the cytoskeleton and spindle apparatus during meiosis, reduce chromosomal misalignment, and promote proper nuclear maturation. These mechanisms are consistent with the findings of the present study in which the sericin-supplemented group exhibited the highest proportion of oocytes reaching the MII stage and the lowest MDA levels.

A notable observation in this study was the substantial increase in MDA levels in the –SC group compared with both the control and +SC groups. This elevation indicated that exposure to H₂O₂ during the pre-IVM phase effectively induced oxidative stress, leading to enhanced lipid peroxidation and a corresponding decline in nuclear maturation. Interestingly, oocytes in the control group also exhibited measurable levels of MDA, suggesting that

in vitro conditions may inherently expose oocytes to a certain degree of oxidative stress [

5,

6]. This aligns with a previous report demonstrating that oocytes can generate ROS during metabolic activation after collection and throughout the early IVM period [

9]. The significant reduction in MDA observed in the +SC group not only relative to –SC but also compared with the control, further supports the notion that sericin supplementation does more than counteract experimentally induced oxidative stress; it may actively improve the intracellular redox balance beyond the physiological baseline.

Recent evidence also indicated that sericin’s antioxidative action extends beyond direct free radical scavenging to include the preservation of cumulus–oocyte communication. Supplementation with 0.1% sericin has been shown to reduce intracellular ROS, maintain gap junction communication (GJC), and preserve transzonal projections (TZPs) between the oocyte and cumulus cells. Such sustained communication enhances the transfer of metabolites and promotes glutathione (GSH) synthesis within the oocyte, an intrinsic antioxidant crucial for meiotic progression [

19]. These dual mechanisms, direct suppression of ROS and indirect enhancement of endogenous GSH, provide a plausible explanation for the superior nuclear maturation seen in the +SC group. The concomitant decrease in MDA levels and increase in MII rate observed in this study thus reflect an improved oxidative environment that supports meiotic resumption, spindle stability, and chromosomal alignment, ultimately preserving oocyte competence under oxidative challenge.

Although sericin supplementation demonstrated clear benefits in reducing oxidative damage and improving nuclear maturation, several limitations of this study should be noted. The present study focused primarily on nuclear maturation and lipid peroxidation, without assessing cytoplasmic maturation or intracellular structures that are highly sensitive to oxidative stress [

20]. Previous evidence indicated that oxidative stress can impair mitochondrial ATP production, disrupt microtubule polymerization, and compromise spindle assembly, leading to chromosome misalignment and reduced developmental competence [

21]. Such cytoskeletal abnormalities have also been associated with decreased fertilization potential and lower blastocyst formation [

22]. Therefore, future investigations should include assessments of mitochondrial activity, spindle morphology, and specific oxidative biomarkers, along with downstream functional outcomes such as IVF success and embryo development. These approaches would help clarify whether sericin prevents less obvious cytoskeletal defects that may not be captured by nuclear maturation alone.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that sericin supplementation during both pre-IVM phases effectively mitigated oxidative stress induced by H₂O₂ in bovine oocytes. Sericin markedly reduced intracellular MDA levels a widely accepted indicator of lipid peroxidation and restored meiotic progression to the MII stage to levels comparable with the control group. These results support the dual protective role of sericin, involving both direct free radical scavenging and the enhancement of intrinsic antioxidant defenses, potentially mediated through the preservation of cumulus–oocyte communication. Beyond its antioxidative effects, the findings highlight sericin’s value as a natural and biocompatible additive capable of improving oocyte resilience during routine procedures such as ovary transportation and post-mortem handling, where oxidative stress is unavoidable. Its suitability for use in serum-reduced or defined culture systems also aligns with emerging trends toward safer, more standardized, and ethically sustainable reproductive technologies. Although the study confirmed sericin’s beneficial influence on nuclear maturation, additional research is needed to determine whether these improvements extend to cytoplasmic maturation, spindle integrity, mitochondrial function, and downstream developmental competence following IVF or embryo culture. Future investigations in oocytes obtained via ovum pick-up (OPU) or under field conditions will be essential for validating sericin’s practical applicability. Collectively, the evidence suggests that sericin holds strong potential as a standard supplement for enhancing oocyte quality and improving the overall efficiency and reliability of IVEP systems in cattle.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Y., S.T., A.S., and T.R.; methodology, S.Y., S.T., A.S., and T.R.; software, S.Y.; validation, S.Y., and T.R.; formal analysis, S.Y.; investigation, S.Y., S.T., and A.S.; resources, T.R.; data curation, S.Y.; writing—original draft, S.Y.; writing—review and editing, T.R.; visualization, S.Y., and T.R.; supervision, T.R.; project administration, S.Y.; funding acquisition, T.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and the APC were funded by Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kasetsart University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for the study because the oocyte samples were obtained from slaughterhouses as part of the routine meat inspection process. The animals were slaughtered for commercial purposes and not specifically for research. Only carcass tissues from animals certified as fit for human consumption by veterinary authorities were used. Therefore, no live animals were handled, subjected to experimental procedures, or exposed to any additional harm or distress for the purpose of this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ATP |

Adenosine Triphosphate |

| COCs |

Cumulus–oocyte complexes |

| GJC |

Gap junction communication |

| GSH |

Glutathione |

| GV |

Germinal vesicle |

| GVBD |

Germinal vesicle breakdown |

| H₂O₂ |

Hydrogen peroxide |

| IETS |

International Embryo Technology Society |

| IVC |

In vitro culture |

| IVEP |

In vitro embryo production |

| IVF |

In vitro fertilization |

| IVM |

In vitro maturation |

| MI |

Metaphase I |

| MII |

Metaphase II |

| MDA |

malondialdehyde |

| OPU |

Ovum pick-up |

| ROS |

reactive oxygen species |

| SC |

Sericin |

| TBARs |

Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances |

| TZPs |

Transzonal projections |

References

- Ferré, L.; Kjelland, M.; Strøbech, L.; Hyttel, P.; Mermillod, P.; Ross, P. Recent advances in bovine in vitro embryo production: reproductive biotechnology history and methods. Animal 2020, 14, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, J.; De Roos, A.; Mullaart, E.; De Ruigh, L.; Kaal, L.; Vos, P.; Dieleman, S. Factors affecting oocyte quality and quantity in commercial application of embryo technologies in the cattle breeding industry. Theriogenology 2003, 59, 651–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, M. Oxidative stress and redox regulation on in vitro development of mammalian embryos. Journal of Reproduction and Development 2012, 58, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerin, P.; El Mouatassim, S.; Menezo, Y. Oxidative stress and protection against reactive oxygen species in the pre-implantation embryo and its surroundings. Human reproduction update 2001, 7, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combelles, C.M.; Gupta, S.; Agarwal, A. Could oxidative stress influence the in-vitro maturation of oocytes? Reproductive biomedicine online 2009, 18, 864–880. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Soto-Heras, S.; Paramio, M.-T. Impact of oxidative stress on oocyte competence for in vitro embryo production programs. Research in Veterinary Science 2020, 132, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Zuo, L. Characterization of oxygen radical formation mechanism at early cardiac ischemia. Cell Death & Disease 2013, 4, e787–e787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, A.; Durairajanayagam, D.; Du Plessis, S.S. Utility of antioxidants during assisted reproductive techniques: an evidence based review. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology 2014, 12, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morado, S.A.; Cetica, P.D.; Beconi, M.T.; Dalvit, G.C. Reactive oxygen species in bovine oocyte maturation in vitro. Reproduction, Fertility and Development 2009, 21, 608–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappel, S. The role of mitochondria from mature oocyte to viable blastocyst. Obstetrics and gynecology international 2013, 2013, 183024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El, H.A.H.M. Lipid peroxidation end-products as a key of oxidative stress: effect of antioxidant on their production and transfer of free radicals. In Lipid peroxidation; IntechOpen, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.-Q. Applications of natural silk protein sericin in biomaterials. Biotechnology Advances 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramwit, P.; Kanokpanont, S.; De-Eknamkul, W.; Kamei, K.; Srichana, T. The effect of sericin with variable amino-acid content from different silk strains on the production of collagen and nitric oxide. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition 2009, 20, 1295–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustina, S.; Karja, N.; Hasbi, H.; Setiadi, M.; Supriatna, I. Hydrogen peroxide concentration and DNA fragmentation of buffalo oocytes matured in sericin-supplemented maturation medium. South African Journal of Animal Science 2019, 49, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satrio, F.; Karja, N.; Setiadi, M.; Kaiin, E.; Gunawan, M.; Memili, E.; Purwantara, B. Improved maturation rate of bovine oocytes following sericin supplementation in collection and maturation media. Tropical Animal Science Journal 2022, 45, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobe, T.; Ikebata, Y.; Onitsuka, T.; Wittayarat, M.; Sato, Y.; Taniguchi, M.; Otoi, T. Effect of sericin on preimplantation development of bovine embryos cultured individually. Theriogenology 2012, 78, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yindeetrakul, S.; Triwutanon, S.; Sangmalee, A.; Rukkwamsuk, T. Optimization of Hydrogen Peroxide Concentrations for Inducing Oxidative Stress in Bovine Oocytes Prior to In vitro Maturation. Animals 2025, 3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aramwit, P.; Kanokpanont, S.; Nakpheng, T.; Srichana, T. The effect of sericin from various extraction methods on cell viability and collagen production. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2010, 11, 2200–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatun, H.; Yamanaka, K.-i.; Sugimura, S. Antioxidant sericin averts the disruption of oocyte–follicular cell communication triggered by oxidative stress. Molecular Human Reproduction 2024, 30, gaae001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, X.Q.; Lu, S.; Guo, Y.L.; Ma, X. Deficit of mitochondria-derived ATP during oxidative stress impairs mouse MII oocyte spindles. Cell research 2006, 16, 841–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashibe, S.; Kobayashi, Y.; Toishikawa, S.; Nagao, Y. Effects of maternal liver abnormality on in vitro maturation of bovine oocytes. Zygote 2025, 33, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilia, L.; Chapman, M.; Kilani, S.; Cooke, S.; Venetis, C. Oocyte meiotic spindle morphology is a predictive marker of blastocyst ploidy—a prospective cohort study. Fertility and Sterility 2020, 113, 105–113. e101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).