Submitted:

25 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Selection Process

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Quality Assessment

2.7. Data Synthesis

3. Results

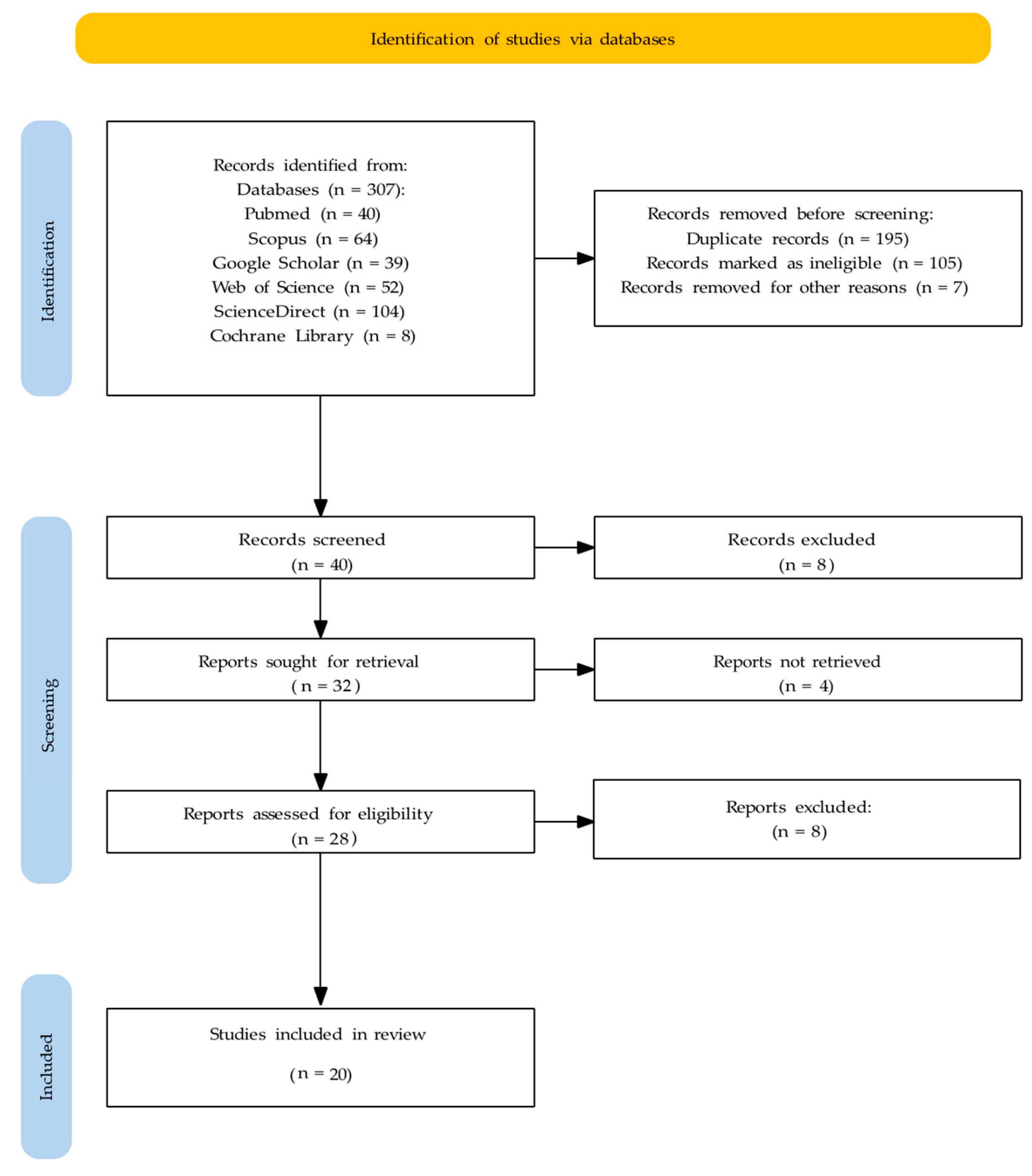

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Evidence Quality Distribution (Oxford CEBM)

3.4. Synthesis of Findings

3.4.1. Terminology and Definitions

3.4.2. Epidemiology and Demographics

3.4.3. Clinical Presentation

3.4.4. Etiology and Pathophysiology

3.4.5. Differential Diagnosis

3.4.6. Diagnostic Approaches and Criteria

3.4.7. Treatment Approaches and Management

3.4.8. Special Considerations and Complications

3.5. Summary of Evidence

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with Existing Literature

4.2. Clinical Implications

4.3. Pathophysiological Insights and Future Directions

4.4. Research Gaps and Future Priorities

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

4.5.1. Strengths

4.6.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

- OD is a distinct clinical entity with the following characteristic features: female predominance, onset in middle age, chronic course, onset often following dental procedures, and frequent psychiatric comorbidities.

- Current evidence suggests that OD is a central sensory processing disorder rather than a primary occlusal or purely psychiatric condition, although psychiatric comorbidities are common and clinically important.

- Conservative multidisciplinary management is strongly recommended, including patient education, CBT, and supportive pharmacotherapy. Irreversible dental interventions should be avoided because of the risk of iatrogenic harm.

- Emerging neurophysiological evidence (fNIRS and cerebral blood flow studies) provides objective support for central nervous system involvement and may eventually yield diagnostic biomarkers.

- Substantial research gaps exist, particularly the absence of population-based epidemiological data, validated diagnostic criteria, and randomized controlled trials.

- Improved professional education and clinical awareness are needed to facilitate the early recognition, appropriate management, and prevention of iatrogenic complications.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OD | Occlusal dysesthesia |

| PBS | Phantom Bite Syndrome |

| CEBM | Center for Evidence-Based Medicine |

| TMD | Temporomandibular Disorders |

| TMJ | Temporomandibular Joint |

| fNIRS | Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy |

| CBT | Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy |

References

- Imhoff, B.; Ahlers, M.O.; Hugger, A.; Lange, M.; Schmitter, M.; Ottl, P.; Wolowski, A.; Türp, J.C. Occlusal dysesthesia—A clinical guideline. J. Oral Rehabil. 2020, 47, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hara, E.S.; Matsuka, Y.; Minakuchi, H.; Clark, G.T.; Kuboki, T. Occlusal dysesthesia: A qualitative systematic review of the epidemiology, aetiology and management. J. Oral Rehabil. 2012, 39, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, M.; Hong, C.; Liu, Z.; Takao, C.; Suga, T.; Tu, T.T.H.; Yoshikawa, T.; Takenoshita, M.; Sato, Y.; Higashihori, N.; et al. Case Report: Iatrogenic Dental Progress of Phantom Bite Syndrome: Rare Cases With the Comorbidity of Psychosis. Front. Psychiatry. 2021, 12, 701232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelleher, M.G.; Rasaratnam, L.; Djemal, S. The paradoxes of phantom bite syndrome or occlusal dysaesthesia (‘dysesthesia’). Dent. Update 2017, 44, 8–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, T.T.H.; Watanabe, M.; Toyofuku, A.; Yojiro, U. Phantom bite syndrome. Br. Dent J. 2022, 232, 839–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melis, M.; Zawawi, K.H. Occlusal dysesthesia: A topical narrative review. J. Oral Rehabil. 2015, 42, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Mikami, S.; Okada, K.; Matsuki, T.; Gotouda, A.; Gotuda, S.; Satoh, K.; Komatsu, K. A clinical study on persistent uncomfortable occlusion. Prosthodont. Res. Pract. 2007, 6, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Salazar, V.; Morrow, L.; Schiffman, E.L. Pain and persistent occlusal awareness: What should dentists do? J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2012, 143, 989–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelleher, M.G.D.; Canavan, D. The perils of “phantom bite syndrome” or “occlusal dysaesthesia”. J. Irish Dent. Assoc. 2020, 66, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguchi, H.; Yamauchi, Y.; Karube, Y.; Suzuki, N.; Tamaki, K. Occlusal dysesthesia: A clinical report on the psychosomatic management of a Japanese patient cohort. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2017, 30, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, T.T.H.; Watanabe, M.; Nayanar, G.K.; Umezaki, Y.; Motomura, H.; Sato, Y.; Toyofuku, A. Phantom bite syndrome: Revelation from clinically focused review. World J. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 1053–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howick, J.; Chalmers, I.; Glasziou, P.; Greenhalgh, T.; Heneghan, C.; Liberati, A.; Moschetti, I.; Phillips, B.; Thornton, H.; The 2011 Oxford CEBM Levels of Evidence (Introductory Document). Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. Available online: https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-of-evidence/ocebm-levels-of-evidence (accessed on 7 October 2025).

- Rampello, A.; Rampello, A. Description of low-threshold mechanisms of consciousness and occlusal dysesthesia: diagnosis and therapy through active functional rehabilitative repositioning bite. Ann. Stomatol. 2025, 16, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türp, J.C.; Hellmann, D. Occlusal dysesthesia and its impact on daily practice. Semin. Orthod. 2024, 30, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versteegh, P.A.M.; van Rood, Y.R. Occlusal dysaesthesia an unusual persistent somatic symptom. Ned. Tijdschr. Tandheelkd. 2025, 132, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Umezaki, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Miura, A.; Shinohara, Y.; Yoshikawa, T.; Sakuma, T.; Shitano, C.; Katagiri, A.; Sato, Y.; Takenoshita, M.; Toyofuku, A. Psychiatric comorbidities and psychopharmacological outcomes of phantom bite syndrome. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 78, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, Y.; Ishikawa, Y.; Munakata, M.; Shibuya, T.; Shimada, A.; Miyachi, H.; Wake, H.; Tamaki, K. Diagnosis of occlusal dysesthesia utilizing prefrontal hemodynamic activity with slight occlusal interference. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2016, 34, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munakata, M.; Ono, Y.; Hayama, R.; Kataoka, K.; Ikuta, R.; Tamaki, K. Relationship between occlusal discomfort syndrome and occlusal threshold. Kokubyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2016, 83, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ligas, B.B.; Galang, M.T.S.; BeGole, E.A.; Evans, C.A.; Klasser, G.D.; Greene, C.S. Phantom bite: A survey of US orthodontists. Orthodontics (Chic). 2011, 12, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tinastepe, N.; Küçük, B.B.; Oral, K. Phantom bite: Case report and literature review. Cranio. 2015, 33, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutter, B.A. Phantom bite: A real or a phantom diagnosis? A case report. Gen. Dent. 2017, 65, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Umezaki, Y.; Tu, T.T.H.; Toriihara, A.; Sato, Y.; Naito, T.; Toyofuku, A. Change of cerebral blood flow after a successful pharmacological treatment of phantom bite syndrome: A case report. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2019, 42, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author(s), Year | Title | Type of Study | Sample Size | Oxford Level | Important Findings | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yamaguchi et al., 2007 [7] | A clinical study on persistent uncomfortable occlusion | Retrospective case series | 39 patients | Level 4 | Improvement observed in 17/39 patients; muscle relaxant medication showed significant relationship with treatment outcome; prognosis cannot be predicted from initial history alone | Persistent uncomfortable occlusion comprises several occlusal patterns; comprehensive assessment needed beyond occlusal contacts |

| Ligas et al., 2011 [20] | Phantom bite: A survey of US orthodontists | Cross-sectional survey | 337 orthodontists | Level 4 | Approximately 50% of responding orthodontists unfamiliar with “phantom bite”; many reported encountering such patients; no regional differences in familiarity | Awareness of phantom bite among orthodontists is inconsistent; educational efforts needed |

| Hara et al., 2012 [2] | Occlusal dysesthesia: A qualitative systematic review of the epidemiology, aetiology and management | Systematic review | 37 patients (pooled) | Level 2 | Predominantly middle-aged women; long symptom duration (mean ~6 years); frequent psychological comorbidity; treatments (psychotherapy, CBT, splints, medications) supported mainly by case reports | Current evidence is low quality; OD has characteristic features, but robust studies needed for mechanisms and evidence-based management |

| Leon-Salazar et al., 2012 [8] | Pain and persistent occlusal awareness: What should dentists do? | Clinical discussion (Case report) | 1 patient | Level 5 | Cases combining TMD and phantom bite syndrome; multidisciplinary diagnostic context important | Dentists should recognize persistent occlusal awareness and consider multidisciplinary evaluation rather than repeated occlusal treatments |

| Melis et al., 2015 [6] | Occlusal dysesthesia: a topical narrative review | Topical narrative review | 22 articles reviewed | Level 5 | OD commonly associated with emotional distress; frequently follows dental procedures; repeated dental interventions often worsen symptoms | Irreversible occlusal treatments contraindicated; management should emphasize counseling, defocusing, psychotherapy, conservative measures |

| Watanabe et al., 2015 [17] | Psychiatric comorbidities and psychopharmacological outcomes of phantom bite syndrome | Retrospective case series | 130 patients | Level 4 | High frequency of psychiatric comorbidities; variable responses to psychopharmacological interventions | Psychiatric evaluation is important in PBS management; psychopharmacology may benefit some patients but responses heterogeneous |

| Tinastepe et al., 2015 [21] | Phantom bite: a case report and literature review | Case report | 1 patient | Level 5 | Patient with persistent bite discomfort without objective dental pathology; sertraline 50mg/day + psychotherapy led to significant improvement | Clinicians should be aware of phantom bite to avoid unnecessary interventions; consider non-dental causes |

| Ono et al., 2016 [18] | Diagnosis of occlusal dysesthesia utilizing prefrontal hemodynamic activity with slight occlusal interference | Case-control (fNIRS study) | 6 OD patients, 8 controls | Level 3 | OD patients showed persistent increases in deoxyhemoglobin over left frontal pole during occlusal loading; 92.9% diagnostic accuracy | Prefrontal hemodynamic responses may provide objective neuronal signature for OD diagnosis |

| Munakata et al., 2016 [19] | Relationship between occlusal discomfort syndrome and occlusal threshold | Case-control study | 21 ODS patients, 21 controls | Level 3 | Recognition thresholds similar between groups; discomfort thresholds significantly lower in ODS patients | Occlusal discomfort threshold (not recognition) is altered in ODS; foil grinding test useful clinical tool |

| Kelleher et al., 2017 [4] | The paradoxes of phantom bite syndrome or occlusal dysaesthesia | Clinical review (Case series) | 12 patients | Level 5 | PBS typically driven by fixed belief about bad occlusion; often leads to multiple unsuccessful dental interventions; psychiatric explanations discussed | Early recognition and referral to secondary care (including psychiatry) recommended to prevent unnecessary procedures |

| Oguchi et al., 2017 [10] | Occlusal dysesthesia: A clinical report on psychosomatic management of a Japanese patient cohort | Retrospective cohort study | 61 patients | Level 4 | Among 61 patients: 41% resolved, 33% discontinued treatment, 21% referred to specialists, 5% continued treatment; mean follow-up 3.6 years | OD management should account for underlying psychiatric disorders; psychosomatic strategies are important |

| Sutter, 2017 [22] | Phantom bite: a real or a phantom diagnosis? A case report | Case report | 1 patient | Level 5 | Digital occlusal analysis identified prolonged disclusion time and force imbalance; targeted corrections produced marked symptom improvement | Some phantom bite presentations may have identifiable occlusal factors amenable to careful, guided correction |

| Umezaki et al., 2019 [23] | Change of cerebral blood flow after successful pharmacological treatment of phantom bite syndrome: A case report | Case report (with SPECT imaging) | 1 patient | Level 5 | Aripiprazole 3mg/day led to symptomatic improvement and normalized regional cerebral blood flow on SPECT | Findings support CNS involvement in PBS; psychopharmacological treatment may alter neurophysiologic correlates |

| Imhoff et al., 2020 [1] | Occlusal dysesthesia—A clinical guideline | Clinical guideline | 77 articles reviewed | Level 5 | OD independent of occlusion; likely due to maladaptive signal processing; recommended non-dental therapies (education, CBT, supportive medication); advised against irreversible dental treatments | Treat OD with patient education, defocusing, CBT, supportive pharmacotherapy; avoid irreversible dental interventions |

| Tu et al., 2021 [11] | Phantom bite syndrome: Revelation from clinically focused review | Narrative review | Not applicable | Level 5 | PBS is rare but has consistent clinical pattern: persistent non-verifiable occlusal complaints, frequent psychiatric comorbidity, substantial QoL impact | Increased clinician awareness and multidisciplinary care model (dentists, psychiatrists, psychotherapists) necessary |

| Watanabe et al., 2021 [3] | Case Report: Iatrogenic Dental Progress of Phantom Bite Syndrome: Rare Cases With the Comorbidity of Psychosis | Case series | 3 patients | Level 5 | Iatrogenic dental interventions sometimes precipitated or worsened PBS symptoms in patients with comorbid psychosis | Dental procedures can exacerbate PBS in vulnerable patients; coordination with psychiatric services critical |

| Tu et al., 2022 [5] | Phantom bite syndrome | Clinical review | Not applicable | Level 5 | Summarizes clinical features of PBS; emphasizes psychosomatic impact and risk of unnecessary dental interventions | Awareness and conservative multidisciplinary management are essential to limit harm from unnecessary treatments |

| Türp et al., 2023 [15] | Occlusal dysesthesia and its impact on daily practice | Narrative review | Not applicable | Level 5 | OD commonly occurs in stressed patients after dental therapy; often with TMD comorbidity; occlusal adjustments contraindicated; psychological treatments recommended | Primary goal is to improve oral health-related QoL with counseling, psychological therapy, splint defocusing, medication rather than occlusal modification |

| Rampello et al., 2025 [14] | Description of low-threshold mechanisms of consciousness and occlusal dysesthesia: diagnosis and therapy through active functional rehabilitative repositioning bite | Theoretical article | Not applicable | Level 5 | Proposes neurophysiological regulatory pathways; emphasizes occlusal hypervigilance as mechanism in OD; suggests active rehabilitative mandibular repositioning bites | Active rehabilitative mandibular repositioning bites may address occlusal hypervigilance, but empirical validation needed |

| Versteegh et al., 2025 [16] | Occlusal dysaesthesia: an unusual, persistent somatic symptom | Clinical guideline | Not applicable | Level 5 | Approximately 75% of cases follow dental treatment; persistent symptoms should be treated as persistent somatic symptoms requiring dialogue and referral; routine occlusal adjustments contraindicated | General practitioners should engage patients and refer for interventions optimizing conditions for symptom resolution |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).