1. Introduction

Rapid urbanization and the expansion of densely populated cities have significantly increased environmental noise exposure, raising concerns about public health, well-being, and urban livability. Effective management and mitigation of urban noise rely on accurate, reliable, and standardized assessment methods capable of capturing both objective acoustic conditions and subjective human responses. Soundscape evaluation, which integrates perceptual and physical aspects of urban acoustic environments, has emerged as a complementary approach to traditional noise metrics, emphasizing the experiential and contextual dimensions of urban noise [

1].

Engineering and acoustical standards play a central role in ensuring consistency, comparability, and reliability in noise measurement, reporting, and interpretation. ANSI/ASA, ASTM International, and ISO standards provide structured methodologies for quantifying environmental noise, assessing human annoyance, and evaluating soundscapes. These frameworks facilitate reproducible data collection, support cross-study comparisons, and serve as a foundation for research, policy-making, and urban planning initiatives. By standardizing both instrumentation and perceptual assessment protocols, these guidelines reduce methodological variability and promote evidence-based decision-making in environmental acoustics.

In recent years, several review studies have examined acoustics-related standards and their relevance to urban noise assessment and management. Morillas et al. [

2] evaluated ISO 1996-2, which governs the measurement of environmental noise, in the context of strategic noise mapping under the European Noise Directive. Their analysis highlights potential inaccuracies in standardized corrections, such as those related to microphone placement, façade reflections, and geometric conditions, and discusses how these limitations can affect noise exposure estimations in real urban environments, offering insight into the technical and methodological constraints of applying ISO 1996 in practice. Clark et al. [

3] reviewed the application of ISO/TS 15666, the standard for assessing community noise annoyance. They examined methodological issues including variations in annoyance rating scales, differing definitions of “highly annoyed,” and updates introduced in the 2021 revision, underscoring the importance of consistent human-response assessment protocols beyond simple sound-level measurements. Sahlathasneem and Deswal [

4] provided a broad overview of noise measurement approaches, relevant standards, assessment methodologies, geospatial mapping techniques, and public health implications. Aletta [

5] analyzed the adoption of the ISO soundscape standard, a more perception-based approach to acoustic evaluation. The review found that, despite the availability of multiple methodological pathways within the ISO framework, most studies rely primarily on Method A, and full compliance with the standard is relatively rare. This work highlights the increasing importance of soundscape-based approaches that consider the perceived quality of acoustic environments rather than focusing solely on decibel levels. Zhang et al. [

6] sought to develop a systematic understanding of soundscape–context relationships. Their review clarifies the roles of spatial–physical and socio-cultural contextual factors and proposes a framework for standardizing the integration of contextual attributes into soundscape research and practice. Mediastika et al. [

7] examined noise legislation and standards across Southeast Asian (ASEAN) countries, comparing them with those of developed nations and with WHO guidelines. Their findings provide insight into how standards are implemented across diverse policy settings and highlight existing enforcement and regulatory gaps.

While these reviews offer valuable contributions, most focus on one or two specific standards or explore their applications in limited contexts. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no prior review has examined a broader set of key standards from ANSI/ASA, ASTM, and ISO together, nor assessed their collective applications to urban noise and soundscape evaluation.

This review aims to provide a concise overview of the key ANSI/ASA, ASTM, and ISO standards relevant to urban noise assessment and soundscape evaluation. t highlights their measurement principles, practical applications, and contributions to understanding human responses to urban acoustic environments. The focus of this paper is on standard measurement procedures, assessment protocols, and their applications in urban noise and soundscape studies. Detailed comparative analyses of individual standards or technical specifications are beyond the scope of this review. Instead, the emphasis is on illustrating how these standards collectively support consistent, rigorous, and human-centric approaches to assessing urban acoustic environments..

2. Regulatory and Standards Bodies in Acoustics

The formulation, harmonization, and continual refinement of acoustical and noise-control standards are fundamental to ensuring consistency, accuracy, and comparability in research, measurement, and engineering practice worldwide. Across national and international scales, standards bodies play a central role in defining measurement methodologies, performance criteria, and terminology for acoustics, vibration, environmental noise, and related fields. Their coordinated efforts provide the framework that supports scientific inquiry, facilitates technology development, and guides regulatory and policy decisions.

One of the major contributors to acoustical standardization in the United States is ASTM International (formerly known as American Society for Testing and Materials), particularly Committee E33 on Building and Environmental Acoustics, established in 1972 [

8]. Committee E33 publishes standards within the

Annual Book of ASTM Standards, Volume 04.06, and operates through a broad set of specialized subcommittees: E33.01 (Sound Absorption), E33.02 (Speech Privacy), E33.03 (Sound Transmission), E33.04 (Application of Acoustical Materials and Systems), E33.05 (Research), E33.06 (International Standards), E33.07 (Definitions and Editorial), E33.08 (Mechanical and Electrical System Noise), E33.09 (Community Noise), E33.10 (Structural Acoustics and Vibration), as well as administrative subcommittees including E33.90, E33.91, E33.92, and E33.95 (see Appendix

Table A1) . Collectively, these groups have shaped many of the material specifications, testing protocols, and performance metrics that underpin modern building acoustics, architectural design, and environmental noise assessment. ASTM’s standards are widely used in industry and research, offering validated methodologies for evaluating acoustical materials, noise sources, and vibration phenomena.

In parallel, the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) serves as the accrediting body for U.S. standards-developing organizations in acoustics, vibration, shock, and noise. A principal ANSI partner is the Acoustical Society of America (ASA), which administers a series of ANSI-accredited Standards Committees (ASCs) covering topics ranging from bioacoustics to mechanical vibration. Since its formation in 1929, ASA has played a pivotal role in shaping the national and international acoustical standards landscape, supported by its Committee on Acoustical Standardization. Its influence is underscored by the prominent involvement of ASA leadership in standards development; historically, six ASA presidents and two vice presidents have held major standardization roles, including four members of the National Academy of Engineering [

9]. Through this network, ASA provides a platform for integrating scientific advances into widely adopted measurement and evaluation procedures.

At the global level, acoustical standardization is led primarily by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC). ISO’s Technical Committee ISO/TC 43 (Acoustics) and its Subcommittee ISO/TC 43/SC 1 (Noise) develop foundational international standards governing sound measurement, noise assessment, and acoustic performance evaluation [

10]. These standards underpin regulatory frameworks and engineering practices worldwide, with broad influence across occupational noise exposure, building and architectural acoustics, machinery noise emission, environmental and ecoacoustic monitoring, and related domains.

Complementing ISO’s work, the IEC develops standards for acoustic and electroacoustic instrumentation, with emphasis on device performance, calibration protocols, and measurement technologies. A key example is the IEC 60268 series (under technical committee TC 100/TA 20), which specifies performance testing methods for sound system equipment. This series encompasses standards for amplifiers (IEC 60268-3), microphones (IEC 60268-4), loudspeakers (IEC 60268-5), and headphones (IEC 60268-7), as well as procedures for evaluating speech intelligibility (IEC 60268-16). Such standards are essential for ensuring the accuracy, reliability, and interoperability of sound level meters, microphones, sensors, and numerous electrical and electronic systems, including household appliances and renewable-energy technologies such as wind turbines.

Together, these national and international organizations form a highly interconnected standardization ecosystem that underlies nearly every aspect of acoustical science and engineering. Their collaborative and complementary efforts enhance reproducibility, support cross-disciplinary research, enable technological innovation, and establish consistent criteria for environmental and occupational noise management. As acoustics continues to expand into emerging domains, such as ecoacoustics, soundscape ecology, and intelligent noise-control systems, the role of these standards bodies remains indispensable for guiding methodological rigor and supporting global harmonization in the field.

3. Standardization Frameworks for Urban Noise Assessment

Accurate and consistent measurement of environmental noise relies on standardized procedures that ensure comparability and reliability across studies, applications, and geographic regions. Standardized methods define how sound is measured, the instruments and calibration protocols to be used, the selection of appropriate acoustic indicators, and the conditions under which data are collected. By providing a uniform framework, these standards reduce variability, minimize potential biases, and enable meaningful comparison of results across different urban environments, research projects, and policy assessments. Such consistency is critical for informed decision-making in urban planning, public health, and environmental management. The following sections review key standards relevant to environmental noise measurement and urban soundscape assessment.

3.1. Environmental Noise Measurement

3.1.1. ANSI/ASA standards

The ANSI/ASA standards provide the quantitative and procedural foundation for the measurement, description, and management of environmental noise. Among these, the S1 and S12.9 series are particularly influential in shaping standardized approaches to environmental acoustics and community noise assessment (Appendix

Table A2,

Table A3,

Table A4).

The ASA S1 series establishes the fundamental terminology, instrumentation requirements, and data representation frameworks that underpin all subsequent noise measurement standards. For example, ANSI/ASA S1.1 –

Acoustical Terminology [

11] provides standardized definitions for fundamental concepts such as ambient sound, sound pressure level, frequency weighting, equivalent continuous sound level (

), statistical descriptors (L10, L90), as well as impulse noise. These definitions are indispensable for urban noise research because they ensure that acoustic metrics are used consistently across studies and disciplines. Such terminological uniformity enables coherent communication among engineers, planners, public-health researchers, and social scientists engaged in urban and environmental acoustics. Other standards within the S1 series address the performance and calibration of sound level meters (S1.4, Parts 1–3) [

12,

13,

14], acoustic instrumentation (S1.15, Parts 1–7) [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21], and data formatting for spectral analysis (S1.11, Parts 1–3) [

22,

23,

24], which specify octave and one-third octave band measurements. Collectively, these standards ensure measurement accuracy, promote interoperability of acoustic data, and support reproducibility in research and regulatory applications.

The ANSI/ASA S12.9 series [

25] —

Quantities and Procedures for Description and Measurement of Environmental Sound — forms the core framework for environmental noise characterization and community noise evaluation. This multi-part series (Parts 1–7) provides consistent methods for measuring, describing, and interpreting outdoor sound, thereby supporting environmental impact assessment, land-use planning, and the prediction of community responses to noise exposure. ANSI/ASA S12.9 Part 1 [

26] defines the fundamental acoustic metrics and outlines general procedures for characterizing environmental sound in community settings. The standardized descriptors provided in this part form the basis for regulatory compliance and environmental noise management, supporting applications such as noise mapping, transportation noise impact assessment, and baseline environmental surveys.

ANSI/ASA S12.9 Part 2 [

27] specifies methodologies for the long-term measurement of time-averaged outdoor sound at one or more community locations . It provides detailed requirements for sampling duration, number and placement of measurement sites, and accuracy classifications (Class A, B, or C). The standard also defines procedures for computing long-term average sound levels such as the day-night average sound level (

) and Community Noise Equivalent Level (CNEL). These descriptors are widely used in urban planning, zoning evaluations, aviation-noise studies, and population-exposure modeling, enabling representative assessments of environmental noise from continuous or distributed sources such as highways, airports, and industrial facilities.

ANSI/ASA 12.9 Part 3 [

28] complements the S12.9 framework by specifying procedures for short-term, time-averaged outdoor measurements conducted with an observer present. It includes methods for correcting measured sound levels to account for background noise, ensuring accurate characterization of community sound exposure. This part is widely applied in attended surveys, such as urban traffic spot measurements, walk-through noise audits, hotspot assessments, complaint investigations, calibration of noise maps, and validation of noise model predictions. Attended measurements are particularly important in urban environments with complex sound sources, such as construction, transit, or amplified music, where human oversight is necessary for proper contextual interpretation.

ANSI/ASA 12.9 Part 4 [

29] provides procedures for long-term, unattended environmental sound monitoring and for predicting community annoyance responses to urban noise. The standard supports modern sensor-based noise monitoring networks by specifying installation procedures, data-logging protocols, environmental protection measures, and system performance verification. In recent years, it has become increasingly important as researchers deploy unattended, city-wide monitoring networks to collect continuous acoustic data in complex urban environments.

ANSI/ASA 12.9 Part 5 [

30] offers guidance on evaluating the compatibility of various land uses with existing or projected acoustic environments . It uses the annual average of the day–night adjusted sound exposure or the adjusted day–night average sound level to characterize long-term environmental sound conditions. The standard provides an informative annex for designating land uses that are compatible with specific noise exposure ranges, thereby supporting evidence-based urban and regional planning decisions. ANSI/ASA 12.9 Part 7 [

31] focuses on the measurement of low-frequency noise (LFN) and infrasound (ILFN), addressing both outdoor conditions in the presence of wind and indoor environments in occupied spaces. This standard is particularly relevant for wind turbine projects and industrial operations, where low-frequency components are significant. It outlines standardized techniques to minimize wind-induced noise and to ensure consistent, repeatable, and comparable low-frequency measurements using commercially available instrumentation.

Taken together, the ANSI/ASA S1 and S12.9 series provide a coherent and comprehensive framework for environmental acoustics. They collectively support every stage of environmental noise management, from the definition of acoustic quantities and calibration of instruments to the measurement, interpretation, and regulation of environmental sound. Their systematic structure and methodological rigor ensure the reproducibility, comparability, and scientific credibility of environmental noise assessments across a wide range of practical, regulatory, and research applications.

3.1.2. ASTM standards

The ASTM has developed a comprehensive suite of standards that address various aspects of environmental acoustics, ranging from terminology to field measurement methodologies and data interpretation. These standards collectively support the uniform assessment of environmental noise in diverse contexts such as urban environments, industrial facilities, and transportation corridors.

The foundational document in this domain is ASTM C634-22–

Standard Terminology Relating to Building and Environmental Acoustics [

32]. This standard provides standardized definitions and terminology for building and environmental acoustics, ensuring clear communication of acoustic parameters, measurement methods, and evaluation criteria. By establishing a consistent linguistic and conceptual framework, ASTM C634-22 serves as a reference point for the interpretation and application of subsequent measurement standards. For practical field measurement of environmental sound, ASTM E1014-12(2021),

Standard Guide for Measurement of Outdoor A-Weighted Sound Levels [

33], offers comprehensive guidance on the determination of outdoor noise using A-weighted sound levels. It specifies procedures for data collection, instrumentation requirements, calibration, and reporting. This guide is particularly relevant for environmental impact assessments and regulatory compliance studies, where A-weighted levels are commonly employed to approximate human hearing sensitivity.

Further refinement in sound power determination is provided by ASTM E1124-10(2024),

Standard Test Method for Field Measurement of Sound Power Level by the Two-Surface Method [

34]. This standard prescribes a field method for quantifying the sound power level of noise sources based on sound pressure measurements taken over two concentric surfaces surrounding the source. It facilitates accurate characterization of equipment and machinery in situ, an essential step for evaluating their environmental noise contribution.

For statistical analyses of fluctuating outdoor noise environments, ASTM E1503-22,

Standard Test Method for Conducting Outdoor Sound Measurements Using a Statistical Sound Analysis System [

35], establishes procedures employing statistical sound analysis systems. The method defines requirements for instrumentation, measurement duration, and data reduction, supporting robust characterization of variable noise environments such as those influenced by traffic or meteorological conditions.

Complementing these measurement methodologies, ASTM E1686-23,

Standard Guide for Applying Environmental Noise Measurement Methods and Criteria [

36], offers integrative guidance on selecting appropriate measurement approaches and evaluation criteria. This guide covers key aspects including weighting networks, averaging times, and noise metrics (e.g.,

, L10, L90, etc.), thereby assisting practitioners in aligning measurement objectives with relevant regulatory or analytical frameworks.

Targeting specific source-receiver configurations, ASTM E1780-12(2021) [

37], provides procedures for assessing sound propagation from localized fixed sources such as mechanical plants or stationary industrial operations. It addresses practical considerations such as microphone placement, environmental influences, and data interpretation to ensure reliable evaluation of noise exposure at receiver locations.

Finally, ASTM E2202-23 [

38], focuses on health-related assessments of continuous noise emissions from equipment. It specifies the instrumentation, calibration, measurement procedures, and reporting methods necessary for evaluating potential auditory or non-auditory health risks associated with continuous noise exposure.

Collectively, these ASTM standards provide a coherent framework for the accurate, consistent, and scientifically rigorous measurement of environmental noise. Their application ensures data comparability across studies and supports informed decision-making in environmental management, regulatory compliance, and urban planning contexts.

3.1.3. ISO standards

The ISO has developed a comprehensive set of standards that establish globally recognized methodologies for describing, measuring, and assessing environmental noise (see Appendix

Table A6). These standards ensure consistency and comparability of acoustic data across regions and applications, forming the basis for regulatory frameworks, environmental assessments, and research practices worldwide. Among the most important documents in this domain are the ISO 1996 and ISO 9613 series, which collectively define the essential quantities, measurement procedures, and propagation models used in environmental acoustics.

The cornerstone of environmental noise assessment is ISO 1996-1:2016,

Acoustics — Description, measurement and assessment of environmental noise — Part 1: Basic quantities and assessment procedures[

39]. This standard establishes the fundamental acoustic quantities used to characterize environmental noise, including the equivalent continuous sound pressure level (

), sound exposure level (SEL), and rating level, and it outlines the principles and procedures for community noise assessment. It provides unified terminology and detailed guidance on field measurement techniques, instrumentation requirements, uncertainty evaluation, and methods for determining noise exposure. Importantly, ISO 1996-1 also incorporates procedures for integrating physical measurements with perceptual considerations, such as tonality, impulsiveness, and low-frequency content, through appropriate correction factors. Although it does not prescribe noise limits, ISO 1996-1 provides a robust and standardized framework for describing and assessing noise from diverse sources, making it broadly applicable in urban planning, strategic noise mapping, and environmental impact assessments.

Complementing this, ISO 1996-2:2017,

Acoustics — Description, measurement and assessment of environmental noise — Part 2: Determination of sound pressure levels [

40], specifies detailed methodologies for measuring environmental sound levels in outdoor environments. It provides guidance on the selection of measurement locations, instrumentation, calibration procedures, and data evaluation techniques, with particular emphasis on quantifying measurement uncertainty and ensuring representative sampling of environmental noise conditions. This standard also allows for the combination of direct measurements and calculation-based estimates, making it flexible for both field monitoring and predictive assessments of environmental noise exposure. Owing to its comprehensive scope, ISO 1996-1 and ISO 1996-2 serve as the primary references for regulatory compliance, environmental noise monitoring, and the calibration and validation of noise maps. Their widespread use in urban noise studies ensures methodological consistency and facilitates comparisons across locations and over time.

While the ISO 1996 series focuses on the measurement and assessment of environmental noise, the predictive modelling of outdoor sound propagation is addressed in ISO 9613-2:2024,

Acoustics — Attenuation of sound during propagation outdoors — Part 2: Engineering method for the prediction of sound pressure levels outdoors [

41]. This standard provides an engineering method for calculating sound attenuation from one or more sources to a receiver under “favorable” meteorological conditions, such as downwind propagation or temperature inversion. It incorporates the major physical mechanisms that influence outdoor sound transmission, including geometrical divergence, atmospheric absorption, ground effects, reflections, and barrier attenuation, forming the computational basis for widely used noise prediction software (e.g., SoundPLAN, CadnaA). The resulting predictions are expressed as long-term average A-weighted sound pressure levels, ensuring consistency with the indicators defined in the ISO 1996 series. ISO 9613-2 is extensively used in environmental impact assessments and strategic noise mapping because it provides a practical and empirically validated framework for modelling environmental noise in complex outdoor environments. Its role is particularly critical in urban planning applications, such as evaluating new road corridors, industrial developments, and residential expansions, where forecasting future noise exposure is essential for designing effective mitigation strategies prior to construction.

In addition to these core standards, several others contribute to comprehensive environmental noise characterization. ISO 3746:2010,

Acoustics — Determination of sound power levels and sound energy levels of noise sources using sound pressure — Survey method using an enveloping measurement surface over a reflecting plane [

42], and ISO 3747:2010,

Acoustics — Determination of sound power levels and sound energy levels of noise sources using sound pressure — Engineering/survey methods for use in situ in a reverberant environment [

43], provide standardized procedures for determining the sound power levels of noise sources in the field. These methods are particularly valuable for identifying and characterizing noise emissions from machinery and equipment used in industrial or outdoor settings, which can then serve as input data for propagation models such as those defined in ISO 9613-2.

Together, these ISO standards form a cohesive framework that encompasses the description, measurement, and prediction of environmental noise. The ISO 1996 series defines the key acoustic metrics and assessment methodologies, ISO 9613-2 extends this framework into predictive modelling of sound propagation, and the ISO 3740 series supports accurate determination of source sound power levels. Collectively, they ensure that environmental noise studies are methodologically sound, scientifically reproducible, and internationally harmonized. Adherence to these standards enhances the reliability of noise data used in regulatory compliance, environmental impact assessments, and policy formulation, while also facilitating cross-country comparisons and the integration of measurement and modelling approaches in contemporary environmental acoustics research.

3.2. Urban Soundscape Assessment

3.2.1. ANSI/ASA and ASTM standards

ANSI/ASA provides the foundational technical framework for evaluating environmental sound. Although ANSI has not issued a dedicated “urban soundscape” standard, several key documents establish the procedures and criteria for measuring and interpreting environmental sound in complex urban settings. For instance, the ANSI S12 series standards, particularly ANSI S12.9 (Part 1-7), outline procedures for the measurement and analysis of environmental noise, including methodologies for sound level meters, frequency weighting, and statistical noise descriptors (e.g.,

,

, L90). These standards form the foundation for reliable acoustic measurements, which are necessary for assessing the impact of urban noise on human perception. Moreover, ANSI/ISO S12.65-2006 (R2025) [

44] offers specific applicability to the public realm, used for assessing speech privacy and annoyance in urban parks, plazas, and outdoor dining areas. Furthermore, the ANSI/ASA S12.100 standard [

45], though originally designed for protected natural and quiet residential areas (QRAs), is highly relevant to urban soundscape analysis by providing a rigorous, standardized methodology for defining and measuring the residual sound (or ambient background noise). This standard is particularly significant as an emerging standard for "quiet areas" in cities (e.g., urban parks designated as quiet zones). Its procedures enable planners to accurately establish the acoustic ’floor’ of a specific urban locale using statistical levels like

. This baseline measurement is essential for soundscape planning aimed at preserving quiet zones, setting effective noise control targets for new developments, and ultimately evaluating the perceived quality of the urban acoustic environment, not just the loudness of its noise.

Similarly, ASTM International provides several standards relevant to environmental acoustics and urban sound assessment. Some of the standards developed by committee E33 on building and environmental acoustics, offers guidance for sound measurement in environmental contexts, including assessment of noise impact on communities. ASTM standards often emphasize procedural rigor, including instrumentation calibration, data acquisition protocols, and reporting requirements. Such practices ensure that urban soundscape data can be reproduced and compared across studies, supporting both research and regulatory applications.

Despite these contributions, ANSI and ASTM standards remain largely oriented toward physical noise quantification and do not directly address perceptual or contextual aspects of urban soundscapes. As research in urban sound perception continues to expand, there is an opportunity for these organizations to develop standards integrating both objective and experiential metrics, particularly for evaluating how urban environments influence human well-being.

3.2.2. ISO standards

ISO has advanced urban soundscape research by integrating quantitative, qualitative, and contextual methodologies that account for human perception. It defines soundscape as “the acoustic environment as perceived, experienced, and/or understood by a person or people, in context” (ISO 12913-1:2014), emphasizing perceptual experience rather than sound level alone [

46]. Whereas ISO 1996 and ISO 9613 focus primarily on the physical characterization and prediction of sound, the ISO 12913 series introduces a human-centred framework for perceptual and contextual assessment (

Table A6). It provides methodologies for collecting perceptual data, analysing listener responses, and incorporating contextual factors such as visual cues, cultural expectations, and environmental characteristics. This perspective is increasingly important in contemporary urban design, where improving the quality of public spaces requires not only reducing unwanted noise but also fostering positive auditory experiences. Soundscape approaches have therefore been widely applied in the study and design of parks, pedestrian zones, and waterfront areas, supporting a shift toward more holistic and people-centred urban acoustic planning.

ISO 12913-1:2014 [

46] establishes the conceptual foundation of the soundscape series, introducing a triadic framework that links sound sources, the physical environment, and human perception. It identifies key components, context, sound sources, auditory sensation, interpretation, and response, providing a structure for urban soundscape research that extends beyond conventional acoustic measurement. Building on this framework, ISO/TS 12913-2:2018 [

47] specifies procedures for collecting both physical and perceptual data. Physical measurements include standard acoustic indicators (

,

, L10, L90), frequency analyses (1/3-octave bands), and spatially immersive techniques such as binaural recordings and soundwalks. Perceptual assessments employ questionnaires, interviews, and guided soundwalks, often incorporating Perceived Affective Quality (PAQ) metrics to evaluate attributes such as pleasantness, calmness, and eventfulness. Complementary documentation of environmental context, including visual, cultural, and functional characteristics, supports comprehensive interpretation of perceptual responses.

ISO/TS 12913-3:2025 [

48] provides analytical methods for relating physical and psychoacoustic indicators, such as loudness, sharpness, and roughness, to perceptual evaluations through statistical and modelling approaches. Spatial analysis using GIS facilitates the mapping of tranquil areas, noise hotspots, and context-dependent perceptual patterns, thereby informing targeted interventions such as green walls, water features, or traffic-calming strategies. The forthcoming ISO/TS 12913-4 (draft) [

49] extends these principles toward design and planning applications, explicitly linking soundscape assessment to practical urban design decisions. Overall, the ISO 12913 series shifts the emphasis from exposure to experience, prioritizing how acoustic environments are perceived rather than simply how loud they are. Its human-centred, context-sensitive framework supports urban livability, place identity, and well-being, while providing methodological rigor without imposing fixed acceptability thresholds.

Additional ISO standards complement the ISO 12913 soundscape framework by addressing perceptual, psychoacoustic, and contextual factors that influence how people experience urban acoustic environments. ISO/TS 16755-1:2025 [

50] examines the role of non-acoustic factors in shaping human perception, interpretation, and response to environmental sounds. It defines a non-acoustic factor as any influence beyond objectively measured or modelled acoustic parameters that affects how an acoustic environment is perceived or experienced. The standard promotes consistency across disciplines by reconciling the concept of “context” used in soundscape research with the notion of “non-acoustic factors” commonly applied in noise and health studies, supporting more coherent evidence synthesis. ISO/TS 16755-1 also introduces a structured classification of non-acoustic influences, including personal, psychosocial, environmental, and situational factors, and outlines their roles in modulating perceptual outcomes and behavioral responses [

6]. This guidance strengthens the theoretical underpinnings of soundscape assessment and helps integrate perceptual analysis with broader urban design and public health considerations.

The ISO 532 series [

51,

52,

53] further supports this integration by providing standardized psychoacoustic methods for calculating sensory attributes such as loudness, sharpness, and roughness (see Table A7). These indicators are essential for bridging physical measurement with perceptual experience and are widely used in analyses conducted under ISO/TS 12913-3, where relationships between acoustic metrics and listener evaluations are modelled. By offering validated computational procedures, the ISO 532 standards enable more nuanced interpretation of how specific sound characteristics contribute to perceived pleasantness, calmness, vibrancy, or annoyance in urban settings.

Additionally, ISO/TS 15666:2021 [

54] provides standardized tools for assessing community response to noise through annoyance surveys and rating scales. Although traditionally applied in environmental noise and health research, its structured questionnaire methods and response scales are increasingly relevant to urban soundscape studies, particularly when comparing perceptual data with regulatory assessments or modelling results. Integrating ISO 15666 with ISO 12913 enables soundscape research to draw on decades of empirical work on noise annoyance, while adapting these methods to a broader perceptual framework that includes positive and context-dependent experiences, not only adverse outcomes.

Together, ISO/TS 16755, the ISO 532 series, and ISO 15666 enhance the methodological depth of the ISO 12913 framework by addressing psychological, sensory, and community-response dimensions of urban sound perception. These complementary standards strengthen the scientific foundation for designing urban environments that prioritize human experience, providing robust tools for understanding how acoustic, contextual, and individual factors interact to shape soundscape quality, livability, and well-being.

4. Applications of Acoustical Standards in Urban Noise Assessment

4.1. ANSI/ASA and ASTM standards

Recent urban soundscape studies increasingly rely on a rigorous metrological foundation grounded in internationally recognized acoustical standards. For example, many field campaigns deploy sound level meters conformant to ANSI/ASA S1.4 (IEC 61672) to ensure high-precision measurements of overall sound pressure levels, including A- and C-weighted time-averaged metrics, under variable urban conditions [

55,

56]. Such instrumentation commonly uses ANSI/ASA S1.11 fractional-octave filters to perform spectral analyses, which are especially critical in characterizing low-frequency phenomena and infrasound in built environments, consistent with S12.9-Part 7 protocols for low-frequency noise measurement.

When calibrating and validating sensors, researchers draw on ANSI/ASA S1.15 methods for microphone calibration to maintain measurement traceability throughout long-term urban deployments. On the semantics side, ANSI/ASA S1.1 helps standardize definitions across multi-disciplinary teams, ensuring consistent usage (e.g., of community noise descriptors, event metrics, statistical levels). Meanwhile, the ANSI/ASA S12.9 family of environmental-sound quantity definitions supports the adoption of community noise descriptors (e.g., percentile levels,

) in urban studies, and enables cross-study comparability. For example, Gjestland et al. [

57] performed social survey to measuring Community Response to Noise. They used ANSI 12.9 and ISO 1996-1 guidelines to evaluate the community tolerence level and questionaire was prepared using ISO/TS 15666. In a comprehensive review, Khan et al. [

58] reported the use of ANSI/ASA S12.9 standards in measurement of transport noise and vibration.

On the methodological front, ASTM E1503 has been used in recent urban noise compliance studies; for instance, a noise-study around an urban RICE (reciprocating internal combustion engine) facility explicitly cited ASTM E1503 in their measurement plan for capturing equivalent, statistical sound levels and octave-band spectra over multi-day surveys. Calibration and procedural guidance is further reinforced by the ASTM E1686 guide, which directs environmental noise practitioners in selecting appropriate metrics, weightings, and criteria — a necessity in urban settings where heterogeneous noise sources (traffic, rail, HVAC, construction) predominate [

59]. In addition, ASTM C634-22 underpins the consistent use of terms in both instrumentation standards (e.g., S1.4, S1.11) and environmental guidance (e.g., E1686).

Although direct references to ASTM E1014, E1124, E1780, E2202 in peer-reviewed urban soundscape literature remain limited, their roles are implicit: E1780 (guide for measuring outdoor sound from fixed sources) and E2202 (statistical analysis of impulsive source emissions) provide structured protocols for isolating and quantifying discrete urban noise events (e.g., construction, impulse-like sources), while E1014 and E1124 (governing measurement of building-related and façade sound) enable coupling outdoor and indoor noise assessments in dense city environments. These standards form part of the acoustic quality assurance chain in regulatory-driven or health-impact-based urban noise studies.

4.2. ISO standards

4.2.1. ISO 1996

ISO 1996 standards are widely applied in field measurements of urban and environmental noise, providing guidelines for instrumentation, microphone placement, and data analysis to ensure accurate and comparable results. These standards, particularly ISO 1996-2, have been widely utilized in diverse applications, ranging from urban noise monitoring [

60,

61,

62], to façade noise assessments [

63,

64,

65,

66], and the validation of custom measurement equipment [

65]. A growing body of research underscores the importance of adapting measurement protocols to the specific characteristics of each site and noise source, thereby enhancing the accuracy of environmental assessments [

67]. Furthermore, ISO 1996 is frequently integrated with complementary standards such as ISO 9613, which is used for noise mapping and predictive modeling, and ISO 12913-1 for sound classification, enabling comprehensive evaluations of environmental noise across varying terrains, meteorological conditions, and natural–anthropogenic sound interactions [

62,

68].

Recent studies highlight both the versatility and critical importance of ISO 1996 standards in advancing our understanding of noise impacts. Kukulski et al. [

69] introduced parameter-based criteria for the application of impulsive noise adjustments, offering a potential extension to the methodologies outlined in ISO 1996-1. Foraster et al. [

70] conducted a longitudinal investigation on the effects of road traffic noise exposure on cognitive development in schoolchildren in Barcelona, employing ISO 1996-2 to assess long-term noise exposure both indoors and outdoors at schools and homes. Gedik et al. [

71] explored the adverse effects of industrial noise, measured below permissible limits, on workers’ hearing health, performance, and stress levels in medium-sized enterprises, adhering to ISO 1996-2 standards for noise level measurements. Fedorko et al. [

72] assessed the noise environment surrounding roadways, illustrating the need for anti-noise measures based on measurements aligned with ISO 1996-1 and ISO 1996-2 protocols. Mihajlov et al. [

73] proposed a robust methodology for estimating uncertainty in long-term environmental noise measurements, using ISO 1996 as a core framework for refining measurement procedures and enhancing data reliability. Chauhan et al. [

74] applied both analytical models and machine learning methods to predict continuous sound pressure levels (

) and percentile-exceeded sound levels (L10) from road traffic noise, based on over 200 monitoring sites in Delhi-NCR, in full compliance with ISO 1996-2:2017.

4.2.2. ISO 9613

Recent studies demonstrate that ISO 9613 remains one of the most widely applied sound propagation standards in urban and peri-urban noise assessment. Its use spans diverse contexts, allowing researchers to estimate environmental noise under varying geometrical, meteorological, and land-use conditions.

A first major application domain concerns urban and community noise mapping, where ISO 9613-2 provides a standardized basis for modelling noise from commercial, construction and transportation sources. Deaconu et al. [

75] implemented ISO 9613-2 in a prediction tool to assess the impact of commercial centre noise on adjacent residential areas, while Yajing et al. [

76] applied the standard within a GIS-based framework to model airport-related noise in the communities surrounding Nanjing Lukou Airport. Lee et al. [

77] built noise propagation model based on ISO 9613-1 and -2 for construction sites.

A second and rapidly expanding application involves wind turbine noise prediction, where ISO 9613-2 is commonly employed to model propagation from individual turbines and wind farms. This includes studies addressing general environmental noise impacts [

78,

79,

80,

81], the modelling of low-frequency and infrasound components [

82], and the development of perceptual or auralization-based assessment approaches [

83]. Researchers have also extended or adapted ISO 9613-2 within spatially explicit modelling environments, for example in forested landscapes where additional shielding effects are considered [

84]. In operational planning, ISO 9613-2-based propagation models have been incorporated into wind farm optimization frameworks to evaluate noise-constrained operating strategies [

85]. Several studies have additionally examined model performance by comparing ISO 9613-2 predictions to field measurements, highlighting potential deviations between calculated and observed noise levels [

86].

ISO 9613-2 also continues to serve as a reference in noise control evaluations, including structural or infrastructure-based mitigation strategies. For instance, Papadakis et al. [

87] employed the standard to determine insertion loss in FEM-based noise barrier analyses.

4.2.3. ISO/TS 12913

Recent soundscape literature shows widespread and increasingly sophisticated adoption of the ISO 12913 series as a methodological backbone for perceptual, ecological, physiological, and participatory evaluations of urban acoustic environments. A broad review by Aletta and Torresin [

5] demonstrated that researchers predominantly rely on ISO/TS 12913-2 methods for collecting perceptual data, and their analysis revealed growing, yet uneven, compliance with ISO recommendations, highlighting the standard’s central role in harmonizing soundscape research practices. Building on this foundation, several scholars have expanded ISO-based protocols into emerging ecoacoustic frameworks. Lawrence et al. [

88] directly used the ISO 12913-2 perceptual assessment procedure to link soundscape descriptors with ecoacoustic indices, creating composite indicators capable of integrating perceptual and ecological information. Similarly, Zhong et al. [

89] employed ISO-aligned perceptual methods to reveal nonlinear relationships between ecoacoustic indices and soundscape evaluations, demonstrating the capacity of the standard to support advanced modelling of perceptual–ecological interactions.

The ISO 12913 series has also guided novel methodological frameworks and experimental designs. Hammami and Claramun [

90] incorporated ISO 12913 (along with ISO 532) to structure both qualitative and quantitative components of a unified experimental framework for evaluating urban soundscapes. In participatory contexts, Hornberg et al. [

91] applied the ISO-defined soundwalk approach across 35 guided soundwalks to examine how perceived sound type dominance relates to overall soundscape assessments in two contrasting German urban areas. Controlled laboratory and physiological studies have likewise integrated ISO perceptual descriptors: Li et al. [

92] used ISO 12913-based questionnaires to evaluate physiological and subjective responses to 20 representative urban sound scenarios, demonstrating how ISO metrics can guide the interpretation of psychophysiological indicators. Similarly, Xu et al. [

93] adopted ISO soundscape constructs to analyse perceptual responses and contextual factors in dense residential public open spaces.

Spatial and demographic variations in soundscape experience have been explored using ISO-guided survey instruments as well. Papadakis et al. [

94] applied ISO/TS 12913-2 procedures to identify perceptual differences among residents of cities, towns, and villages, while Papadakis et al. [

95] used the same framework to investigate relationships between ISO-defined soundscape attributes and sound categories. Standard validation efforts further demonstrate the operational reach of ISO 12913: Rimskaya-Korsakova et al. [

96] carried out empirical validation of the standard by comparing psychoacoustic and acoustic measurements with the ISO pleasantness–eventfulness coordinate system across diverse urban locations. In open-space design research, Llorca-Bofi Sezer [

97] adopted ISO descriptors to examine how individual soundscape attributes relate to perceived quality in public spaces.

The ISO 12913 framework has also informed interdisciplinary and health-focused approaches. Montenegro et al. [

98] used ISO-aligned deep listening assessments to study links between the urban acoustic environment and mental well-being, integrating perceptual soundscape evaluations with noise mapping. Cultural dimensions of perception have been explored by Zhang et al. [

99], who employed ISO soundscape constructs in modelling cultural influences on emotion-related soundscape interpretations. ISO 12913 guidance has also been extended to non-traditional environments: Puay et al. [

100] adapted ISO perceptual frameworks to assess congregants’ experiences of worship-music soundscapes within a Malaysian church. Finally, Aletta et al. [

101] applied ISO 12913 to frame a systems-thinking investigation of the relationship between soundscape quality and public health, demonstrating the standard’s capacity to integrate perceptual, social, and environmental dimensions in complex urban systems.

4.2.4. ISO 532

The ISO 532 series, which defines standardized psychoacoustic metrics, has seen broad application in recent years, particularly within urban soundscape research where it is frequently used alongside the ISO 12913 soundscape framework. Many studies employ the ISO 532 metrics, such as loudness, sharpness, roughness, and fluctuation strength, to quantify perceptual attributes of complex acoustic environments.

A primary area of application is the characterization of urban soundscapes, especially when direct surveying of perceptual responses is not feasible. Mitchell et al. [

102] applied ISO 532 together with ISO 12913 in a predictive modelling approach to assess changes in soundscape perception in Central London and Venice before and during the COVID-19 lockdown, integrating both subjective and objective indicators. Similarly, Ma et al. [

103] employed ISO 532 to derive psychoacoustic metrics to examine how environmental sound quality influences soundscape preference in public urban spaces. Other researchers have combined ISO 532 with ISO 12913 to identify key perceptual dimensions of urban acoustic environments [

104] and to categorize urban background sounds under varying meteorological conditions for virtual acoustic applications [

105].

Beyond urban soundscapes, the ISO 532 series has also been increasingly adopted in engineering and technical noise assessments. A comprehensive review by Horvath [

106] outlined the use of ISO 532 psychoacoustic metrics in evaluating the noise of geared drives, highlighting their importance for characterizing sound quality in mechanical systems. In materials and structural acoustics, AllahTavakoli et al. [

107] proposed a psychoacoustic-based framework using ISO 532 metrics to improve the sound quality of composite panels while preserving structural performance.

4.2.5. ISO 16755

The application of ISO 16755 has gained increasing relevance in urban soundscape studies, particularly because it complements the perceptual and methodological framework established in ISO 12913 [

108,

109,

110]. While ISO 12913 focuses on describing, analyzing, and reporting soundscape perception, ISO 16755 provides guidance on assessing contextual factors, such as land use, temporal patterns, social activities, and environmental conditions, that substantially influence how urban sound environments are experienced [

6]. As soundscape research continues to shift toward a contextual and interdisciplinary perspective, ISO 16755 offers a systematic foundation for integrating non-acoustic parameters into soundscape evaluations, thereby enabling more comprehensive interpretations of how people perceive urban acoustic environments.

4.2.6. ISO/TS 15666

ISO 15666 has become a widely adopted standard for assessing subjective noise annoyance in urban, occupational, and experimental settings. Its structured questionnaires and numerical rating scales enable consistent evaluation of human responses to environmental noise, supporting both exposure–response research and the development of noise-mitigation strategies.

In occupational contexts, Shabani et al. [

111] used the ISO 15666 questionnaire to evaluate changes in workers’ annoyance following an educational intervention in a textile industry, while Nasrolahi et al. [

112] applied the same instrument to assess annoyance levels in petrochemical-industry workers exposed to chronic noise. In community and infrastructure noise studies, Benz et al. [

113] prepared ISO-15666–based questionnaires to investigate contributors to neighbour-noise annoyance, and Di et al. [

114] used the standard to identify and predict factors influencing annoyance in substation environments.

ISO 15666 is also central to perceptual and experimental noise research. Lacey et al. [

115] combined ISO 15666 with ISO 12913-1/2 soundscape metrics to evaluate a biophilic soundscape design; Socher et al. [

116] used the standard’s 11-point annoyance scale to examine within- and between-participant stability across experimental conditions; and Sobhani et al. [

117] employed the ISO-15666 questionnaire to quantify annoyance while studying cognitive effects of office-noise exposure across personality types.

Table 1.

Applications of ISO Standards in Urban Noise and Soundscape Assessment

Table 1.

Applications of ISO Standards in Urban Noise and Soundscape Assessment

| Standard |

Application Group |

Description of Use in Urban Noise Assessment |

References |

| ISO 1996 |

Field Measurement of Urban Noise |

Establishes procedures for measurement of environmental noise (traffic, industrial, mixed urban environments). Used for compliance checks, monitoring programs, and ground-truthing noise maps. |

[63]; [64]; [60]; [65]; [61]; [66]; [67]; [62]; [68] |

| |

Noise Exposure and Legal Assessment |

Defines noise indicators (, ), rating levels, and guidelines for assessing compliance against local regulations. |

[70]; [69]; [71]; [118] |

| |

Long-Term Monitoring and Trend Analysis |

Supports consistent long-term noise monitoring strategies and uncertainty estimation. |

[72]; [119]; [120]; [73];[74] |

| ISO 9613 |

Noise Prediction |

Core standard for predicting noise from transportation, industrial, and construction sources in open environments. Widely used in noise mapping software. |

[86]; [78]; [79]; [82]; [83] |

| |

Strategic Noise Mapping |

Used in developing citywide noise maps for policy and planning (transport corridors, industrial zones). |

[84] |

| |

Predictive Assessment for Future Infrastructure |

Forecasts effects of proposed roads, transit lines, industrial developments, or new zoning plans. |

[80]; [87]; [85]; [81] |

| ISO 12913 |

Soundscape Characterization |

Provides frameworks for linking acoustic data with human perception (pleasantness, annoyance, appropriateness). Used in quality-of-life evaluations. |

[88] |

| |

Human-Centered Urban Design |

Supports planning and evaluating public spaces (parks, plazas) based on perceived sound environment rather than only sound pressure levels. |

[121]; [122]; [123] |

| |

Perception Surveys |

Methods for perceptual surveys, contextual data collection, and integrating qualitative and quantitative indicators. |

[124]; [99] |

| ISO/TS 16755 |

Non-Acoustic Factors |

Defines and classifies personal, psychosocial, environmental, and situational factors affecting sound perception. Aligns terminology between soundscape and noise/health research. |

[108]; [125]; [109]; [110] |

| ISO 532 |

Psychoacoustic Characterization |

Provides methods for calculating perceptual attributes (loudness, sharpness, roughness, tonality) to bridge physical sound measurement and human experience. |

[102]; [103,126]; [104]; [127]; [105]; [106]; [107] |

| ISO/TS 15666 |

Community Response Surveys |

Standardized methods for measuring noise annoyance and community response. Supports comparison with regulatory thresholds or perceptual soundscape studies. |

[111,113]; [128]; [114]; [108]; [129]; [109]; [130]; [112]; [116]; [117] |

| Other ISO Standards |

Specialized Applications |

Includes ISO 3741 (sound power determination), ISO 3744, ISO 3746, ISO 9614 (sound intensity measurement), ISO 266 (preferred frequencies), supporting urban noise assessments. |

[59]; [131] |

5. Key Findings

5.1. Acoustic Descriptors with Relevant Standards

Table 2 summarizes the key acoustic and psychoacoustic descriptors used in urban soundscape assessment along with their relevant standards. Energy-based metrics like

and

quantify average sound levels and are referenced in ISO 1996-1, IEC 61672-1, ANSI S1.4, and ASTM methods. Statistical and percentile levels (

–

) capture temporal variability, while maximum, minimum, and event-level indicators such as

and SEL describe peak or discrete noise events. Long-term environmental indicators (

,

,

) provide day–evening–night exposure assessment and are aligned with ISO, EU, and national guidelines. Psychoacoustic descriptors, including loudness (

,

,

) and sensory attributes (sharpness, tonality, roughness, fluctuation strength), characterize human perception of sound. For soundscape-focused evaluations, a core set combining acoustic and psychoacoustic metrics is recommended by ISO/TS 12913. Accurate measurement relies on instrumentation and calibration standards (IEC 61672, ANSI S1.4, ASTM E1779), ensuring comparability across studies. Collectively, these descriptors and standards (

Table 2) provide a structured framework for assessing urban acoustic environments [

132].

5.2. Overview of Key Standards for Urban Acoustic Environments

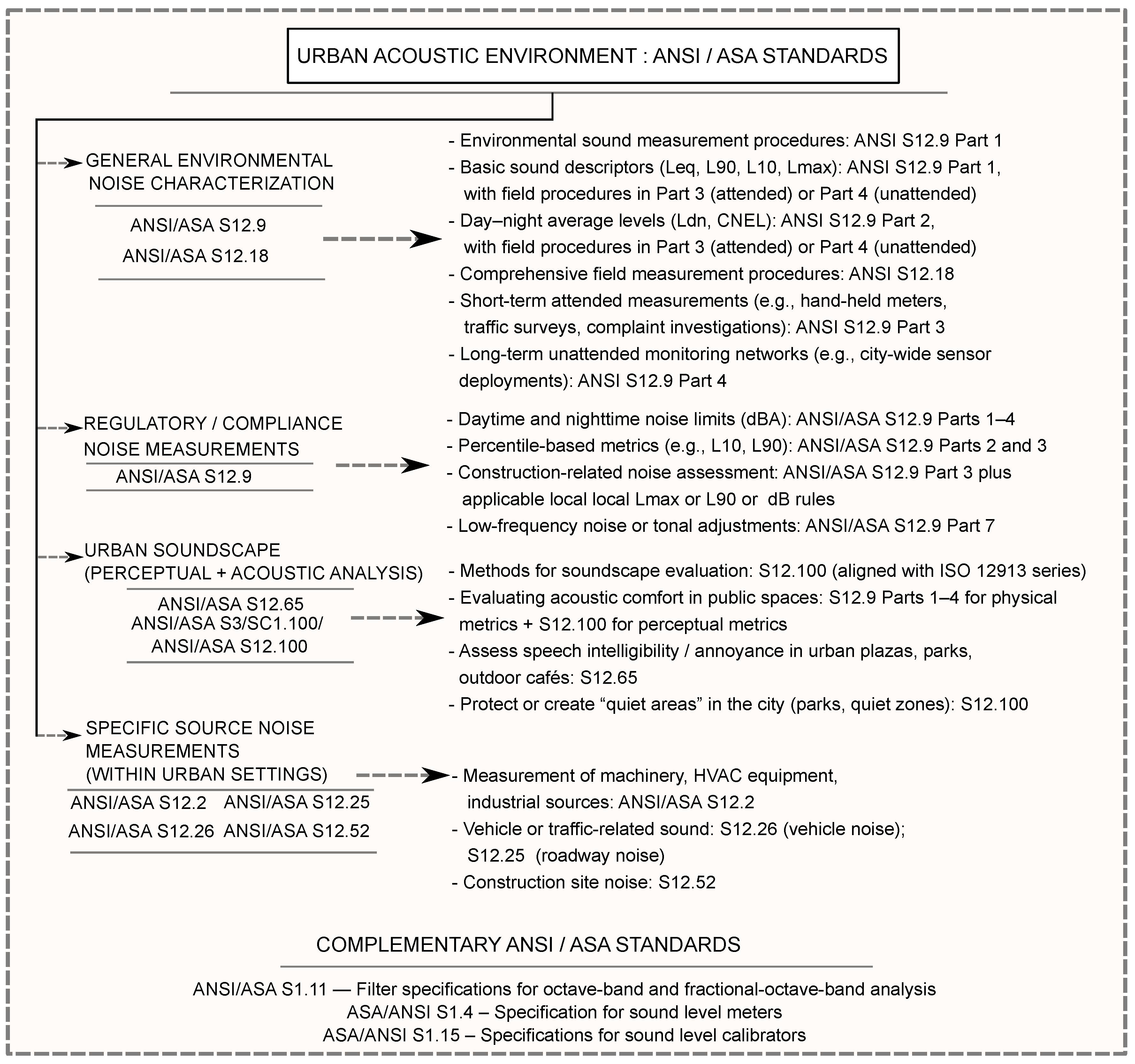

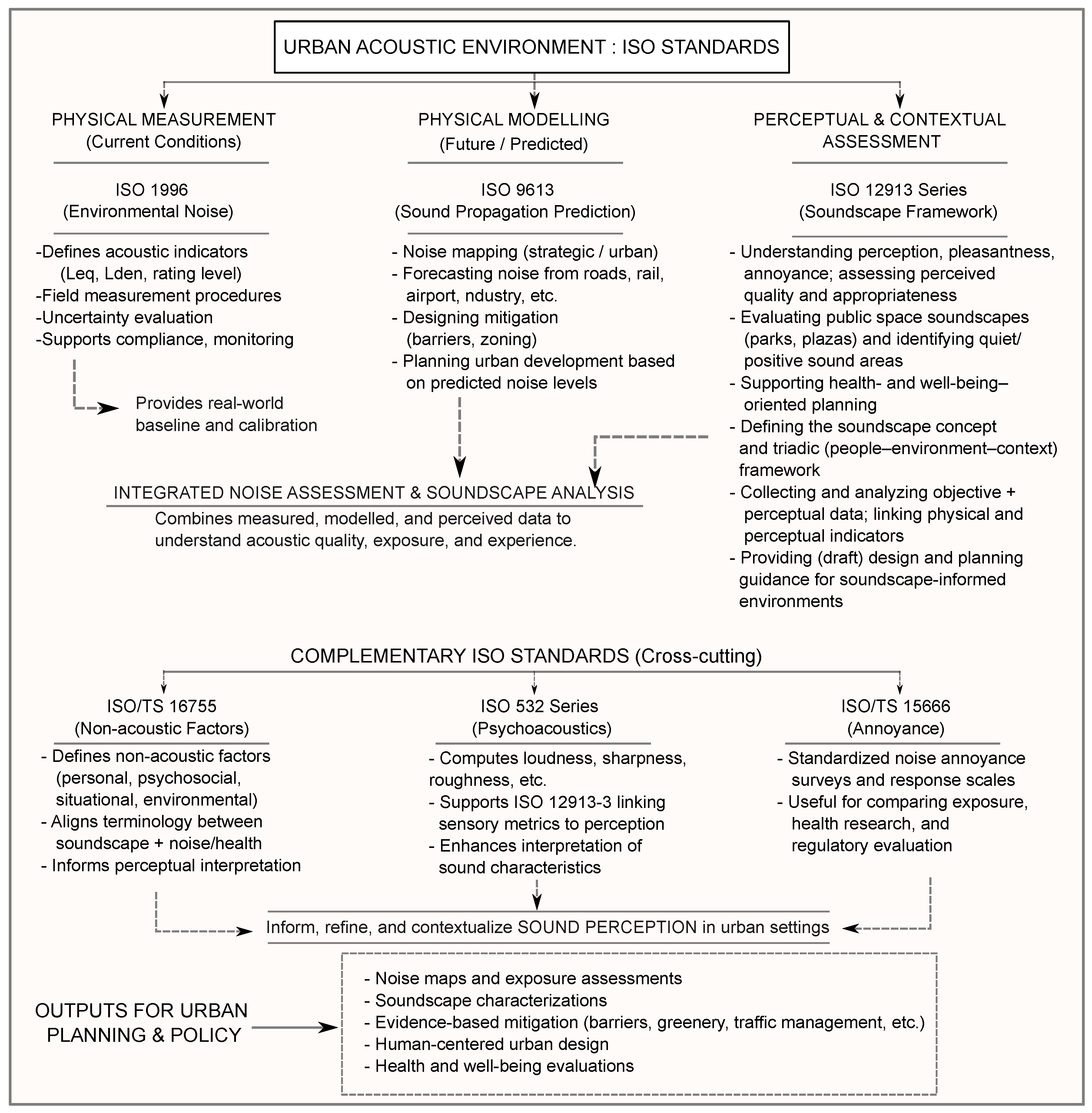

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 provide a concise visual summary of the key ANSI/ASA and ISO standards relevant to urban noise assessment.

Figure 1 outlines major ANSI/ASA standards, highlighting their roles in environmental noise measurement, instrumentation requirements, calibration procedures, and specialized assessments such as construction noise, percentile-based metrics, and low-frequency or tonal adjustments.

Figure 2 complements this by summarizing the ISO standards that support global alignment in noise evaluation, including guidelines for environmental noise measurement, soundscape assessment, annoyance evaluation, and acoustic instrumentation. Together, these figures offer a quick reference for researchers and practitioners, helping them identify the appropriate standard for specific measurement tasks and ensuring consistency in the assessment of urban acoustic environments.

6. Challenges and Future Directions

6.1. Challenges

Urban acoustic environment measurement requires evaluating noise levels, sources, and their impacts within city settings. While standards such as ANSI/ASA, ISO, and ASTM provide a framework for consistent assessments, several challenges arise from the complexity of urban noise, methodological limitations, and practical implementation constraints.

Variability and Complexity of Urban Noise Sources

Urban environments feature dynamic and heterogeneous noise sources, such as traffic, construction, and social activities, that vary temporally and spatially. Standards like ISO 1996 and ANSI/ASA S12.9 use metrics such as LAeq (equivalent continuous sound level) and DNL (day-night level), which may fail to capture transient or impulsive events, such as sirens or aircraft. These average metrics do not account for interactions between multiple sources, resulting in incomplete assessments of urban noise. Additionally, weather conditions (e.g., wind, temperature inversions) introduce significant variability in sound propagation, further complicating measurements, especially for low-frequency or impulsive sounds.

Mixed-use urban developments present another challenge, as standards often assume isolated noise sources. In reality, background noise (e.g., traffic) may mask other industrial or environmental sounds, requiring adjustments that are not always addressed by existing standards.

Inadequacies in Acoustic Descriptors and Metrics

Common descriptors like A-weighting (used in ISO 1996 and ANSI/ASA S12.9) tend to underrepresent annoyance from specific sound characteristics such as tonality, impulsiveness, or low-frequency content. Although adjustments (e.g., +5 dB penalties) are made to account for these features, they are often subjective and fail to capture combined effects in urban environments. Moreover, low-frequency noise (e.g., 16-63 Hz) remains difficult to assess reliably, as urban noise floors often mask its presence, and standards like ASTM E2235 or ISO 3382-1 assume controlled measurement environments not achievable in public spaces.

The use of octave-band analysis for pure tones (e.g., from transformers) is also problematic, as confirmation thresholds can vary, and dB(A) alone fails to fully capture perceptual irritation in real-world settings.

Practical Measurement and Instrumentation Challenges

Field conditions in urban areas, such as high winds, rain, and pollution, can interfere with measurement accuracy, requiring specialized equipment, such as windscreens or dehumidifiers. However, existing standards do not fully address these environmental variables, leading to potential inaccuracies. Long-term monitoring, which is essential for capturing comprehensive noise data, is resource-intensive, while short-term sampling methods (e.g., ISO 1996-2 grid methods) risk missing peak events. Instrumentation must meet IEC/ANSI standards, but urban applications often face durability issues, especially for low-frequency or impulsive sound measurements.

Scope Restrictions and Lack of Comprehensive Guidance

Cultural and socioeconomic factors are underexplored in current standards. Although ISO 12913 includes human perception, its applicability across diverse cultural contexts remains unresolved, as linguistic differences may impact the interpretation of sound descriptors [

133,

134,

135]. Furthermore, while emerging technologies such as wearable sensors, mobile platforms, and AI-driven acoustic analytics hold promise, formal guidance on integrating these tools into established methodologies is still lacking. Issues like data management, validation, and privacy concerns require further attention.

There is also a growing need for improved integration of soundscape metrics into urban design and policy [

136]. ISO 12913-4 begins to address this by linking soundscape assessments to planning actions, but standardized frameworks for incorporating acoustic data into zoning regulations or public space design are still in development. Strengthening this connection could enable more evidence-based interventions.

Finally, most existing standards focus primarily on auditory experiences, with limited consideration for the multisensory nature of urban environments. Future methodologies should expand to account for the interactions between sound, visual, thermal, and olfactory stimuli, which influence overall user experience.

6.2. Future Directions

There is significant potential for the development of new standards by ANSI/ASA and ASTM focused specifically on urban soundscapes. As the field continues to evolve, the establishment of comprehensive urban-specific noise standards would provide invaluable support for researchers and practitioners. These standards could complement existing frameworks like ISO 12913, which addresses soundscape perception, by offering additional guidelines that account for the complexities of urban environments.

A key area for improvement is the adoption of multi-dimensional descriptors that go beyond traditional metrics like LAeq and DNL. These current descriptors often fail to fully capture the nuanced characteristics of urban sound, such as impulsiveness, tonality, and low-frequency content, all of which significantly impact human perception and well-being. Developing more comprehensive, context-sensitive metrics could improve both the accuracy of noise assessments and the applicability of soundscape studies in urban planning and policy development.

Additionally, integrating new technologies and methodologies, such as real-time monitoring, mobile platforms, and AI-driven analytics, will further enhance the scalability and responsiveness of urban noise management. Continued refinement of measurement standards, coupled with greater inclusion of perceptual and cultural factors, will be crucial in advancing the field of urban soundscape research and fostering more sustainable, livable cities.

7. Conclusion

This paper discussed the principal ANSI/ASA, ASTM, and ISO standards that guide contemporary practices in urban noise assessment and soundscape evaluation. By presenting their core principles, methodologies, and areas of application, it highlights how these standards provide a structured foundation for measuring acoustic environments, capturing human perception, and supporting evidence-based urban planning. Their widespread adoption across environmental noise monitoring, perceptual soundscape studies, and applied urban design underscores their essential role in promoting consistency, comparability, and methodological rigor.

At the same time, several opportunities exist to further develop these standards. Challenges related to cultural adaptation, temporal variability, integration of emerging technologies, multisensory interactions, and translation of perceptual metrics into planning practice indicate that urban soundscape assessment is a continually evolving field. Ongoing refinement, informed by interdisciplinary collaboration and practical guidance, will be key to ensuring that acoustic evaluation methods remain relevant to the complexities of modern urban environments.

In summary, ANSI, ASTM, and ISO standards offer a robust foundation for understanding and shaping urban soundscapes. Thoughtful application and continued development of these frameworks can help create healthier, more inclusive, and acoustically responsive cities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation,formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing-visualization, : S.K..

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express sincere gratitude to Prof. H. P. Lee, Department of Mechanical Engineering, National University of Singapore, for providing access to several full copies of relevant standards and for offering valuable insights that supported the development of this work. The author also wishes to acknowledge the support and inspiration of his daughter, Srijanya Sah, throughout the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANS |

American National Standard |

| ANSI |

American National Standards Institute |

| ASA |

Acoustical Society of America |

| ASTM |

American Society for Testing and Materials |

| CNEL |

Community Noise Equivalent Level |

| IEC |

International Electrotechnical Commission |

| ISO |

International Organization for Standardization |

| PAQ |

Perceived Affective Quality |

| SEL |

Sound Exposure Level |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. ASTM Standards

Table A1.

ASTM standards related to environmental and building acoustics.

Table A1.

ASTM standards related to environmental and building acoustics.

| Standard No. |

Title |

Description |

| Developed by Subcommittee: E33.07 on Definitions and Editorial |

| ASTM C634-22 |

Standard Terminology Relating to Building and Environmental Acoustics |

Provides definitions and terminology for building and environmental acoustics, ensuring consistent communication of acoustic parameters, measurement methods, and evaluation criteria. |

| Developed by Subcommittee: E33.08 on Mechanical and Electrical System Noise |

| ASTM E1124-10(2024) |

Standard Test Method for Field Measurement of Sound Power Level by the Two-Surface Method |

Specifies a field method to determine the sound power level of noise sources by measuring sound pressure on two surfaces surrounding the source. |

| ASTM E1574-98(2023) |

Standard Test Method for Measurement of Sound in Residential Spaces |

. |

| ASTM E2202-23 |

Standard Practice for Measurement of Equipment-Generated Continuous Noise for Assessment of Health Hazards |

Specifies procedures for measuring continuous noise generated by equipment to assess potential health hazards, including instrumentation, metrics, and reporting. |

| Developed by Subcommittee: E33.09 on Community Noise |

| ASTM E1014-12(2021) |

Standard Guide for Measurement of Outdoor A-Weighted Sound Levels |

Guides the measurement of outdoor sound levels using A-weighting, including procedures for data collection, instrumentation, and reporting of environmental noise. |

| ASTM E1503-22 |

Standard Test Method for Conducting Outdoor Sound Measurements Using a Statistical Sound Analysis System |

Provides procedures for outdoor noise measurement using statistical analysis systems, including guidelines for instrumentation, measurement periods, and data processing. |

| ASTM E1686-23 |

Standard Guide for Applying Environmental Noise Measurement Methods and Criteria |

Offers guidance on selecting appropriate measurement methods and criteria for environmental noise assessments, covering metrics, weightings, and evaluation approaches. |

| ASTM E1780-12(2021) |

Standard Guide for Measuring Outdoor Sound Received from a Nearby Fixed Source |

Provides guidance for measuring outdoor noise received from a fixed nearby source, including procedures for placement, instrumentation, and evaluation. |

Appendix A.2. ANSI/ASA Standards

Table A2.

Key ASA (ANSI/ASA) Standards Relevant to Acoustical Measurements.

Table A2.

Key ASA (ANSI/ASA) Standards Relevant to Acoustical Measurements.

| Standard No. |

Title |

Description |

| ASA S1.1-2013 (R2024) |

Acoustical Terminology |

Defines standardized terminology used across acoustical measurements and analysis. |

| ASA S1.4-2014 / Part 1 / IEC 61672-1:2013 (R2024) |

Electroacoustics—Sound Level Meters—Part 1: Specifications |

Defines performance and accuracy requirements for integrating and non-integrating sound level meters. |

| ASA S1.4-2014 / Part 2 / IEC 61672-2:2013 (R2024) |

Electroacoustics—Sound Level Meters—Part 2: Pattern Evaluation Tests |

Specifies methods for testing and verifying compliance of sound level meters with Part 1 specifications. |

| ASA S1.4-2014 / Part 3 / IEC 61672-3:2013 (R2024) |

Electroacoustics—Sound Level Meters—Part 3: Periodic Tests |

Describes procedures for periodic verification and functional testing of sound level meters. |

| ASA S1.6-2016 (R2025) |

Preferred Frequencies, Frequency Levels, and Band Numbers for Acoustical Measurements |

Specifies preferred frequencies and bands used in acoustical testing and sound analysis. |

| ASA S1.8-2016 (R2025) |

Reference Values for Levels Used in Acoustics and Vibrations |

Establishes reference quantities for expressing levels of sound pressure and vibration. |

| ASA S1.11-2014 / IEC 61260-1:2014 (R2019) |

Electroacoustics—Octave-band and Fractional-octave-band Filters—Part 1: Specifications |

Specifies performance requirements for octave-band and fractional-octave-band filters. |

| ASA S1.11-2016 / IEC 61260-2:2016 (R2020) |

Electroacoustics—Octave-band and Fractional-octave-band Filters—Part 2: Pattern-evaluation Tests |

Describes methods for testing and verifying the performance of acoustic filters. |

| ASA S1.11-2016 / IEC 61260-3:2016 (R2020) |

Electroacoustics—Octave-band and Fractional-octave-band Filters—Part 3: Periodic Tests |

Provides guidance for conducting periodic performance checks of filter sets. |

| ASA S1.13-2020 |

Measurement of Sound Pressure Levels in Air |

Establishes standardized methods for measuring sound pressure levels in air environments. |

| ASA S1.15-2021 / Part 1 / IEC 61094-1:2000 |

Specifications for Laboratory Standard Microphones |

Defines the mechanical, electrical, and acoustic characteristics of laboratory reference microphones used for precision calibration. |

| ASA S1.15-2021 / Part 2 / IEC 61094-2:2009 |

Primary Method for Pressure Calibration of Laboratory Standard Microphones by the Reciprocity Technique |

Specifies procedures for the primary pressure calibration of laboratory microphones using reciprocity. |

| ASA S1.15-2021 / Part 3 / IEC 61094-3:2016 |

Primary Method for Free-Field Calibration of Laboratory Standard Microphones by the Reciprocity Technique |

Describes the primary method for calibrating microphones in a free-field using reciprocity techniques. |

| ASA S1.15-2021 / Part 4 / IEC 61094-4:1995 |

Specifications for Working Standard Microphones |

Provides specifications for working standard microphones used for routine calibrations and secondary reference measurements. |

| ASA S1.15-2021 / Part 5 / IEC 61094-5:2016 |

Methods for Pressure Calibration of Working Standard Microphones by Comparison |

Details procedures for calibrating working standard microphones against laboratory standard microphones. |

| ASA S1.15-2021 / Part 6 / IEC 61094-6:2004 |

Electrostatic Actuators for Determination of Frequency Response |

Specifies the design and use of electrostatic actuators to determine microphone frequency response. |

| ASA S1.15-2021 / Part 7 / IEC TS 61094-7:2006 |

Values for the Difference Between Free-Field and Pressure Sensitivity Levels of Laboratory Standard Microphones |

Provides reference data for converting between free-field and pressure sensitivity levels of microphones. |

| ASA S1.15-2021 / Part 8 / IEC 61094-8:2012 |

Methods for Determining the Free-Field Sensitivity of Working Standard Microphones by Comparison |

Describes methods for determining free-field sensitivity of working standard microphones relative to a calibrated reference microphone. |

| ASA S1.22-2021 / IEC 60263-2020 |

Scales and Sizes for Plotting Frequency Characteristics and Polar Diagrams |

Defines standard plotting formats for frequency response and polar data. |

| ASA S1.25-1991 (R2020) |

Specification for Personal Noise Dosimeters |

Establishes performance and calibration requirements for instruments measuring personal noise exposure over time. |

| ASA S1.26-2014 (R2024) |

Method for the Calculation of the Absorption of Sound by the Atmosphere |

Describes equations and procedures for determining atmospheric sound absorption. |

| ASA S1.40-2006 (R2024) |

Specifications and Verification Procedures for Sound Calibrators |

Defines requirements and procedures for verifying the accuracy of sound calibrators used to check sound level meters and microphones. |

| ASA S1.42-2023 |

Design Response of Weighting Networks for Acoustical Measurements |

Specifies performance characteristics of A-, B-, C-, and Z-weighting networks used in sound measurement. |

| ASA S1.45-2020 / IEEE Std 260.4-2018 |

IEEE Standard Letter Symbols and Abbreviations for Quantities Used in Acoustics |

Lists standardized symbols and abbreviations for quantities used in acoustics and vibration. |

Table A3.

ANSI/ASA S12.9 series standards on environmental sound.

Table A3.

ANSI/ASA S12.9 series standards on environmental sound.

| Standard No. |

Title |

Description |

| ASA/ANSI S12.9-2013/Part 1 (R2023) |

Quantities and Procedures for Description and Measurement of Environmental Sound — Part 1: Basic Quantities and Definitions |

Defines the fundamental quantities, definitions and metrics for describing environmental sound, including time-average A-weighted levels and other relevant measures. |

| ANSI/ASA S12.9-1992 / Part 2 (R2023) |

Quantities and Procedures for Description and Measurement of Environmental Sound — Part 2: Measurement of Long-Term, Wide-Area Sound |

Describes recommended procedures for measurement of long-term, time-average outdoor environmental sound over one or more locations in a community for use in land-use planning and other applications. |

| ANSI/ASA S12.9-2013 / Part 3 (R2018) |

Quantities and Procedures for Description and Measurement of Environmental Sound — Part 3: Short-term Measurements with an Observer Present |

Specifies recommended procedures for short-term, time-average outdoor sound pressure measurements when an observer is present to record extraneous conditions and background sound corrections. |

| ASA/ANSI S12.9-2021/Part 4 |

Quantities and Procedures for Description and Measurement of Environmental Sound — Part 4: Noise Assessment and Prediction of Long-Term Community Response |

Provides methods to assess environmental sound and predict community response (such as annoyance) for long-term noise from discrete or distributed sources in residential and related land-uses. |

| ANSI/ASA S12.9-2007 / Part 5 (R2024) |