1. Introduction

Hamstring injuries are a frequent and persistent problem in competitive sports and have long been recognized as a major cause of time-loss [

1]. Epidemiological studies have shown a continuous increase, with professional football demonstrating a yearly rise in incidence, and hamstring strains now accounting for nearly one-quarter of all injuries [

2]. Although eccentric strengthening can reduce occurrence [

3] and the mechanisms and risk factors have been increasingly clarified, hamstring injuries remain a significant clinical and performance challenge [

4,

5,

6].

Among hamstring muscle tears, the ST-BF complex is drawing attention because injuries spanning from the origin at the ischial tuberosity to the muscle-tendon junction are frequent and require a long recovery time for return to play (RTP) [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Anatomically, the semitendinosus (ST) and BFLH share a common origin at the ischial tuberosity, forming the conjoint tendon (CT), whereas the semimembranosus (SM) arises separately [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. The CT represents a structurally unique tendinous unit bridging the medial and lateral hamstrings and transmits tractional forces from both muscles during hip extension and knee flexion.

Recent biomechanical and electromyographic studies have highlighted the unique loading environment of this region. BFLH activation increases markedly during the acceleration phase of sprinting, whereas ST activation increases at top speed, demonstrating phase-dependent functional differences between the two muscles [

17]. Furthermore, during the terminal swing phase and initial ground contact, the BFLH generates an external-rotation moment while the ST generates an internal-rotation moment, creating opposing tensile forces that converge on the CT [

18]. Muscle functional MRI studies have also shown that hip extension relies more on the BFLH and SM than on the ST, supporting the biomechanical vulnerability of the CT during high-speed movements [

19]. These opposing loading patterns suggest that when the CT is injured, realignment of tendon fibers during healing may be disrupted, predisposing the region to delayed recovery and re-injury.

Previous imaging and anatomical studies have further described the structural vulnerability of the CT region. Forlizzi et al. stated that the biceps femoris tendon and semitendinosus tendon fuse to form the common tendon and investigated the severity classification of CT injuries on MRI, as well as return to play (RTP) and patient-reported treatment satisfaction [

20]. Rubin et al. [

21] reported that avulsion injuries from the ischial tuberosity most frequently involve the conjoint tendon rather than the biceps femoris alone. Azzopardi et al. [

22] demonstrated that the angle of the CT’s origin may predispose it to increased strain. These anatomical observations support the hypothesis that CT injuries represent a distinct clinical entity [

20,

21,

22]. We previously described the ultrasound morphology of the proximal hamstring originate tendon [

23], providing preliminary structural insights relevant to proximal hamstring injuries. However, despite growing recognition of the CT’s structural and biomechanical role, few clinical studies have specifically examined the prognostic impact of CT involvement on recovery time. Although past classifications, such as the Munich Consensus [

24]and the BAMIC system [

25], have helped standardize the description of hamstring injury morphology, none distinguish CT injury as a unique pathological category. The prognostic relevance of injury location—tendon origin (Zone A), free tendon (Zone B), and the proximal musculotendinous junction (Zone C)—also remains insufficiently understood.

To date, no study has directly compared recovery times for ST injuries without CT involvement, BFLH injuries without CT involvement, and full-layer CT injuries involving both muscles. We hypothesized that injuries involving the ST–BFLH conjoint tendon are associated with longer RTP compared with injuries limited to either the BFLH or ST alone. We also hypothesized that differences in recovery time between unilateral and bilateral injuries would vary at the musculotendinous junction of the CT. Therefore, we performed detailed MRI-based classification of proximal hamstring injuries in university rugby athletes by Type (conjoint tendon vs BFLH-only vs ST-only), Zone (A–E), and Grade (0–3), and compared RTP outcomes across these categories.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

This prospective study involved male university rugby league players who presented to our clinic with posterior thigh pain initially suspected to be hamstring strains. The study period extended from September 2020 to April 2025. After detailed medical history taking, players with no prior hamstring strain in the same region were included.

Individuals with a previous hamstring muscle strain in another region were included if more than one year had elapsed since full recovery. Athletes with a history of muscle strain in the contralateral leg or treatment for other injuries were also included provided they had achieved complete recovery.

Exclusion criteria comprised cases in which a direct external force may have been applied and individuals with a history of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction using hamstring tendon grafts.

2.2. Diagnosis

Diagnosis was based on physical examination, ultrasonography (US), and MRI evaluation. The diagnostic procedure was as follows:

Physical examination: visual inspection, palpation, assessment of joint range of motion, identification of the site of pain by resisted muscle contraction, and detection of extension pain using the Straight Leg Raising test.

Ultrasonography: US was performed primarily at the site of pain using a short-axis technique, followed by long-axis evaluation.

MRI: All athletes suspected of having a hamstring muscle tear based on physical examination and ultrasound underwent MRI, and the final diagnosis was confirmed by two physicians with more than 20 years of experience.

Inclusion of SM injuries: Cases involving isolated semimembranosus (SM) injury identified by MRI were included solely for frequency analysis. The present study on return-to-play (RTP) timing focused exclusively on injuries affecting the BF–ST complex (BFLH, BFSH, ST).

2.3. Zone and Type Classification of BF–ST Complex

Focusing on the conjoint tendon, the following Zone and Type classifications were applied. The conjoint tendon was divided into Zones A–C based on its detachment from the ischium, representing various patterns of musculotendinous junction injury. In Zone C, the injury location was further classified as ST-side, BFLH-side, or involving both.

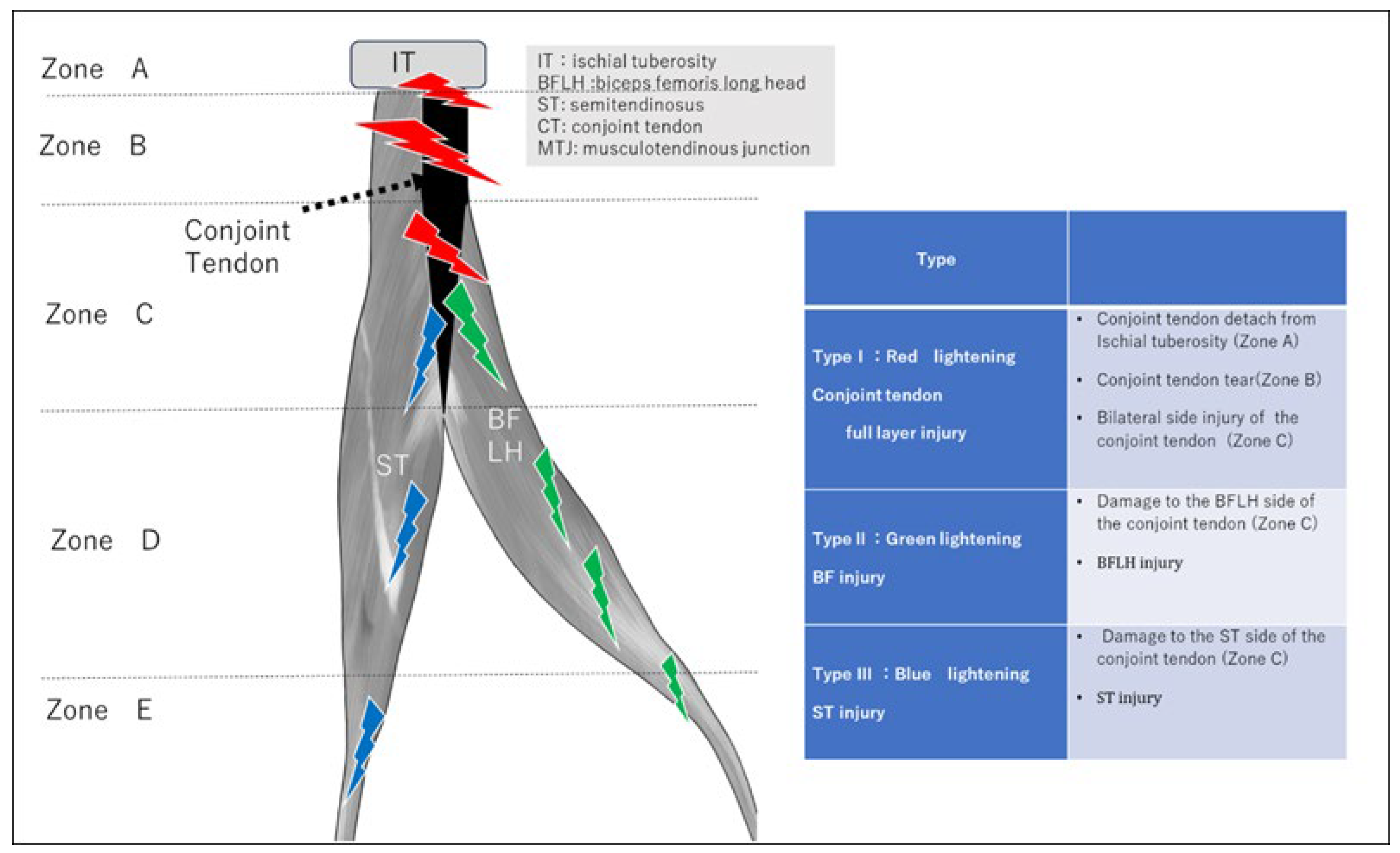

Figure 1.

Type classification of BF-ST complex injury.

Figure 1.

Type classification of BF-ST complex injury.

Injury Site (Zone)

A: Osteotendinous junction

Injury involving detachment of the conjoint tendon from the ischial tuberosity.

B: Conjoint tendon injury

Injury from the ischial tuberosity extending to just before the start of the BFLH musculotendinous junction.

C: Proximal musculotendinous junction injury

Injury to the musculotendinous junction of the conjoint tendon: BFLH-side, ST-side, or both.

D: Intermuscular and myofascial junction

Injury at the intermuscular or myofascial junction between BF and ST muscles.

E: Distal musculotendinous junction and distal tendon injury

Injury at the distal musculotendinous junction or distal tendon of BF or ST.

Severity (Criticality) Classification

Grade 0: Pain and physical findings present but no abnormalities detected on MRI.

Grade 1: Mild injury with a small hematoma or a limited tear.

Grade 2: Moderate injury with a short discontinuity of the injured tendon and mild tendon waviness or distal tearing.

Grade 3: Severe injury characterized by marked tendon tortuosity resulting from loss of tension due to rupture, large discontinuity surfaces, and significant retraction.

2.4. Return-to-Play Assessment

Return to competition was defined as the point at which the player fully rejoined team training or participated in a match. RTP time was compared across the different Types.

Among Type 1 proximal conjoint tendon injuries, differences in RTP were analyzed according to injury site and severity. In Zone C injuries, RTP time was compared for each Type.

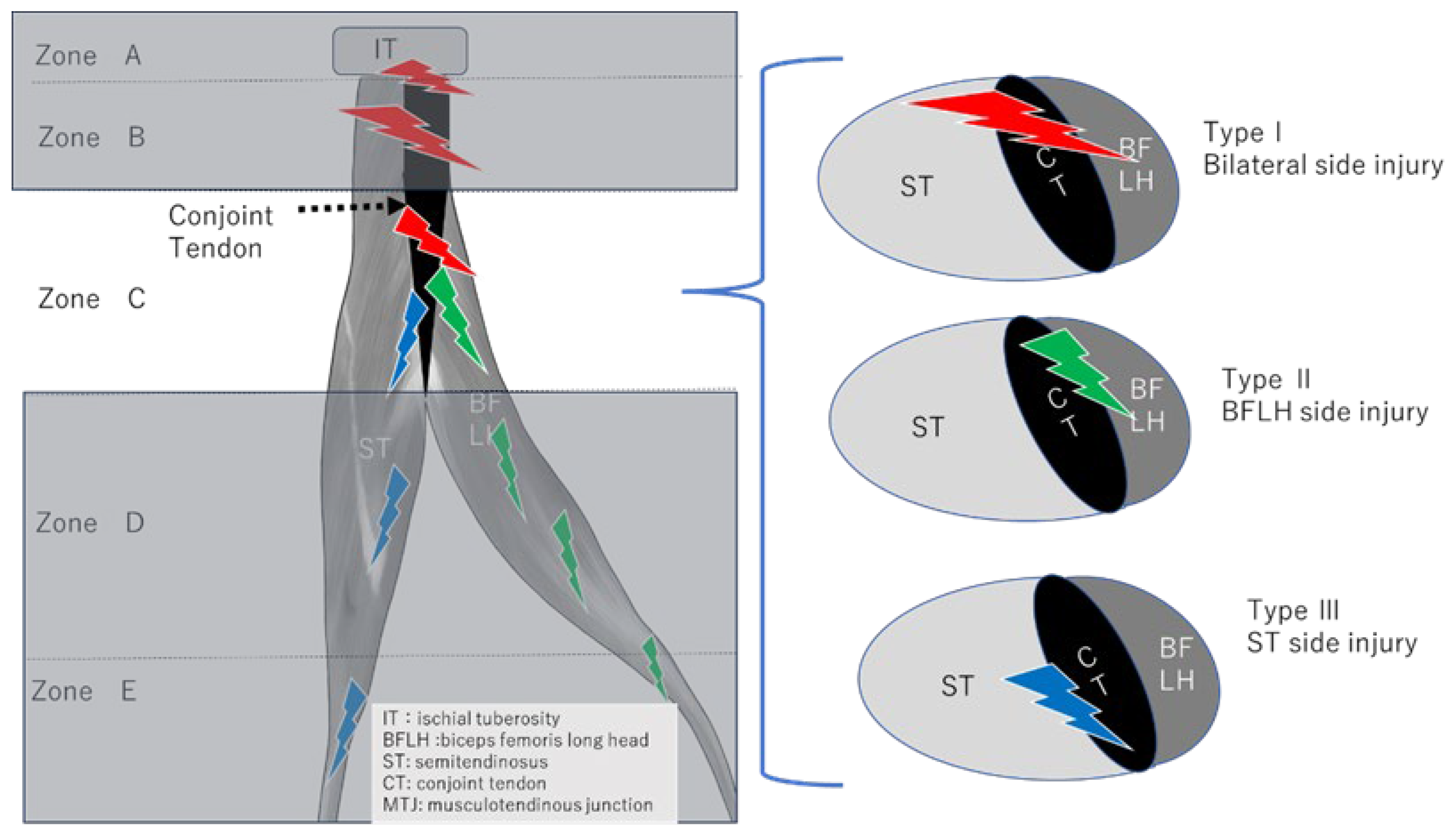

Figure 2.

Determination of unilateral or bilateral involvement in Zone C (muscle-tendon transition zone).

Figure 2.

Determination of unilateral or bilateral involvement in Zone C (muscle-tendon transition zone).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (Version 27; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Normality of RTP time (weeks) for each group was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and homogeneity of variance was evaluated using Levene’s test.

If equal variances were confirmed, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used; if not, the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied.

Post-hoc comparisons were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

2.6. Ethics Approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the institutional clinical research ethics committee of Waseda University. All participants were informed about the purpose and details of the study prior to enrollment, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

3. Results

A total of 41 male university rugby players were included in the final analysis. Initially, 68 athletes with acute proximal hamstring injuries were screened. Among these, four players with bruises, eight players with a previous hamstring strain on the same side, and two players who had undergone ipsilateral hamstring tendon harvest for anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction were excluded. MRI examinations were performed within seven days of injury using 1.5- or 3.0-Tesla scanners. Thirteen of the 54 cases involved isolated semimembranosus (SM) injury. After these exclusions, 41 players with proximal injuries involving the biceps femoris–semitendinosus (BF–ST) complex were included in the final cohort. No cases demonstrated combined injury involving both the SM and the BF–ST complex.

The mean age at the time of injury was 20.4 ± 1.3 years (range, 18–23 years). The cohort included 26 backs (63%) and 15 forwards (37%). Most injuries occurred during running or sprinting.

3.1. Comparison of RTP Time by Type

Type I (conjoint tendon injury) had a mean return-to-play (RTP) duration of 11.4 ± 4.77 weeks, which was significantly longer than Type II (BFLH-only injury) and Type III (ST-only injury). There was no significant difference between Type II and Type III (p = 0.45) (

Table 1).

3.2. Zone C Injury Analysis

In Zone C, which corresponds to the proximal musculotendinous junction, five cases involved injuries extending to both sides of the conjoint tendon. Unilateral BFLH injury was the most common pattern, occurring in 11 cases. There were no cases of unilateral ST injury. The time to return to play was longer for injuries extending to both sides of the conjoint tendon than for unilateral BFLH injuries.

Table 2.

Comparison of RTP Times for Injuries in Zone C.

Table 2.

Comparison of RTP Times for Injuries in Zone C.

| Group |

N |

Mean (weeks) |

SD |

t(df) |

p-value |

| Bilateral side injury |

5 |

11.0 |

3.8 |

|

|

| BFLH side injury |

10 |

6.1 |

2.7 |

2.6 (7.2) |

0.042 * |

| ST side injury |

None |

― |

― |

― |

|

3.3. RTP Analysis in Type I Injuries

When Type I cases were analyzed by Zone (A/B/C) and Grade (1–3), significant differences were observed for both comparisons (p = 0.041 by Zone; p = 0.038 by Grade). Zone A (Grade 2, mean 20.0 weeks) had a significantly longer RTP time than Zones B and C (p < 0.05). Grade 3 (mean 13.67 weeks) also showed a significantly longer RTP time compared with Grades 1 and 2 (p < 0.05).

Additionally, in Type I, Zone A demonstrated a longer RTP time than Zones B and C when comparing Grade 2 injuries (

Table 3).

4. Case Presentations

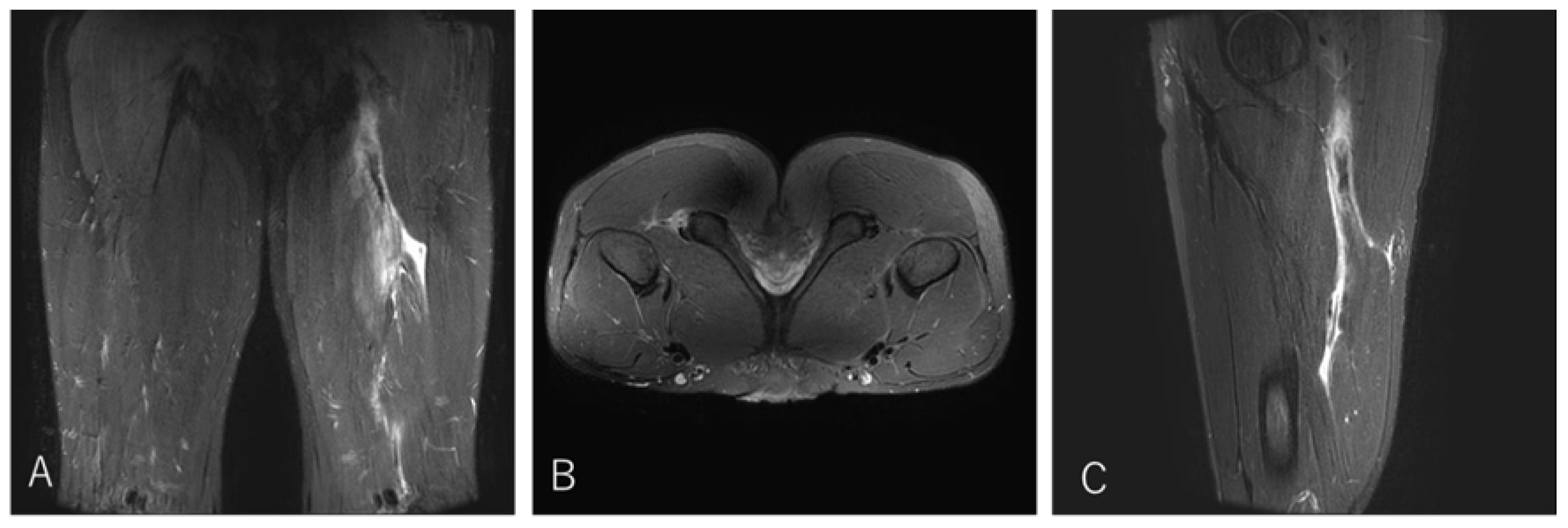

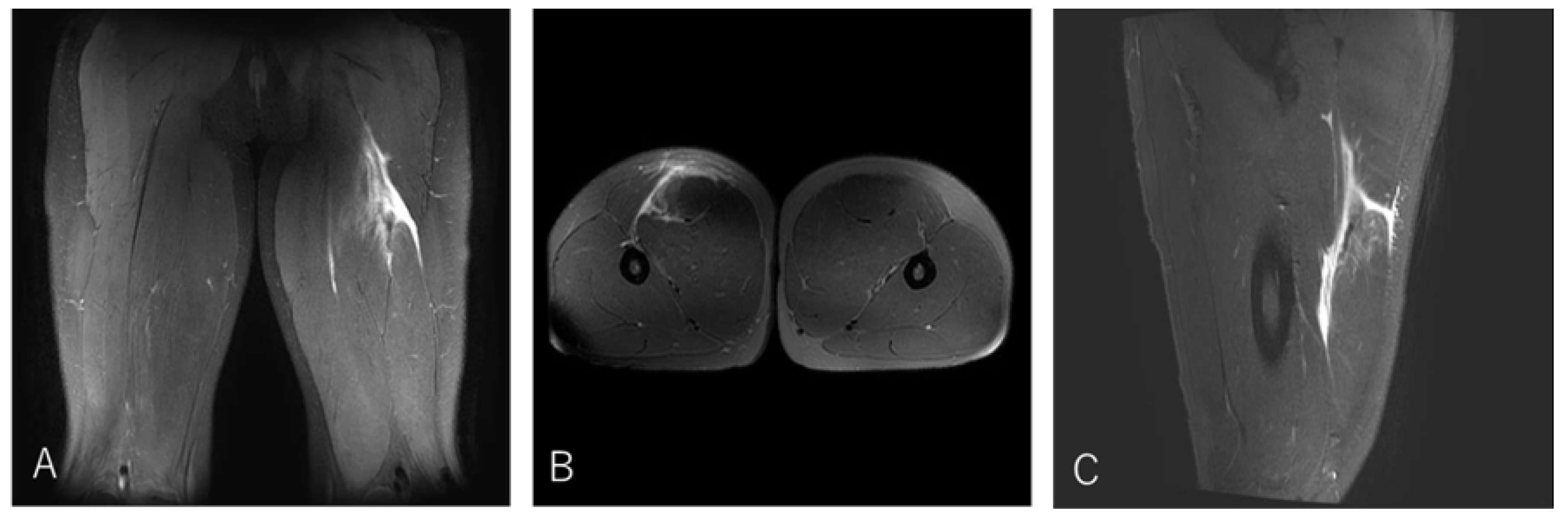

4.1. Case 1. Type I / Zone A (Conjoint tendon detachment), Grade 2

A 20-year-old lock (FW) stepped to evade an opponent while running with the ball and experienced a sharp tearing sensation in the posterior thigh near the origin. He returned to competition after 20 weeks.

Figure 3.

Case 1 MRI images: Conjoint tendon detachment, Type I.

Figure 3.

Case 1 MRI images: Conjoint tendon detachment, Type I.

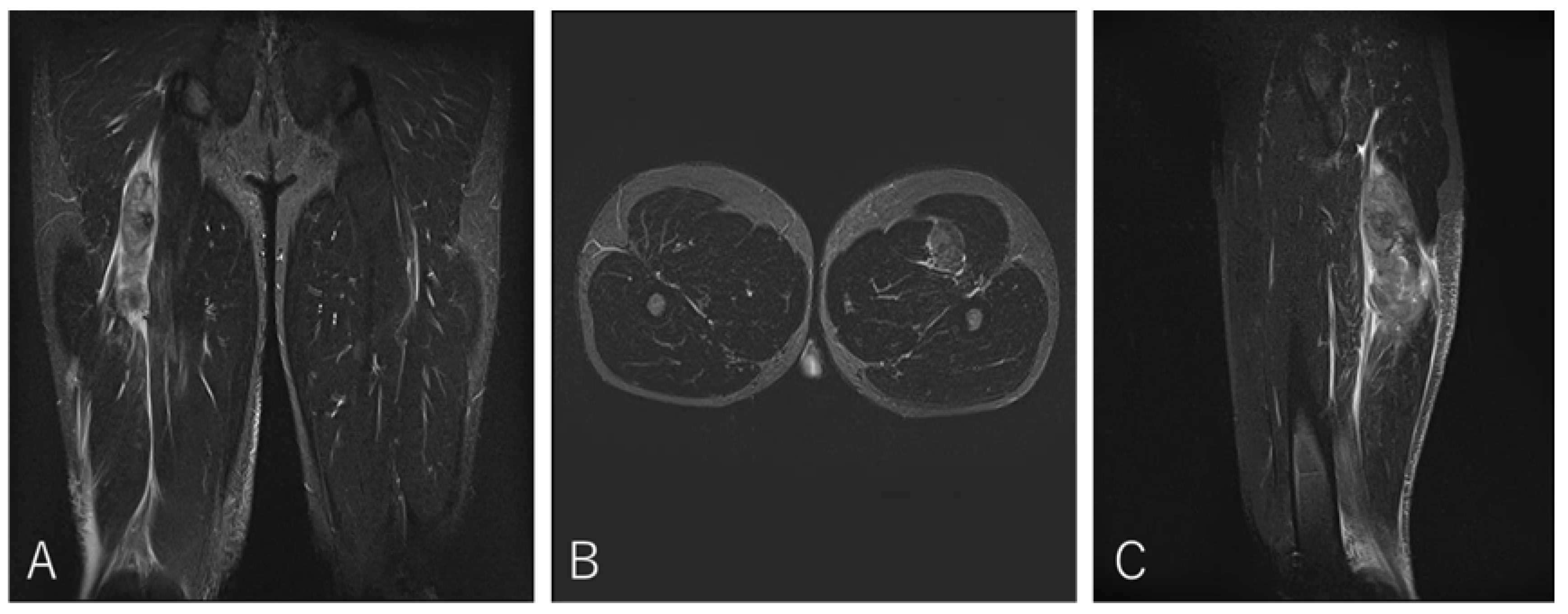

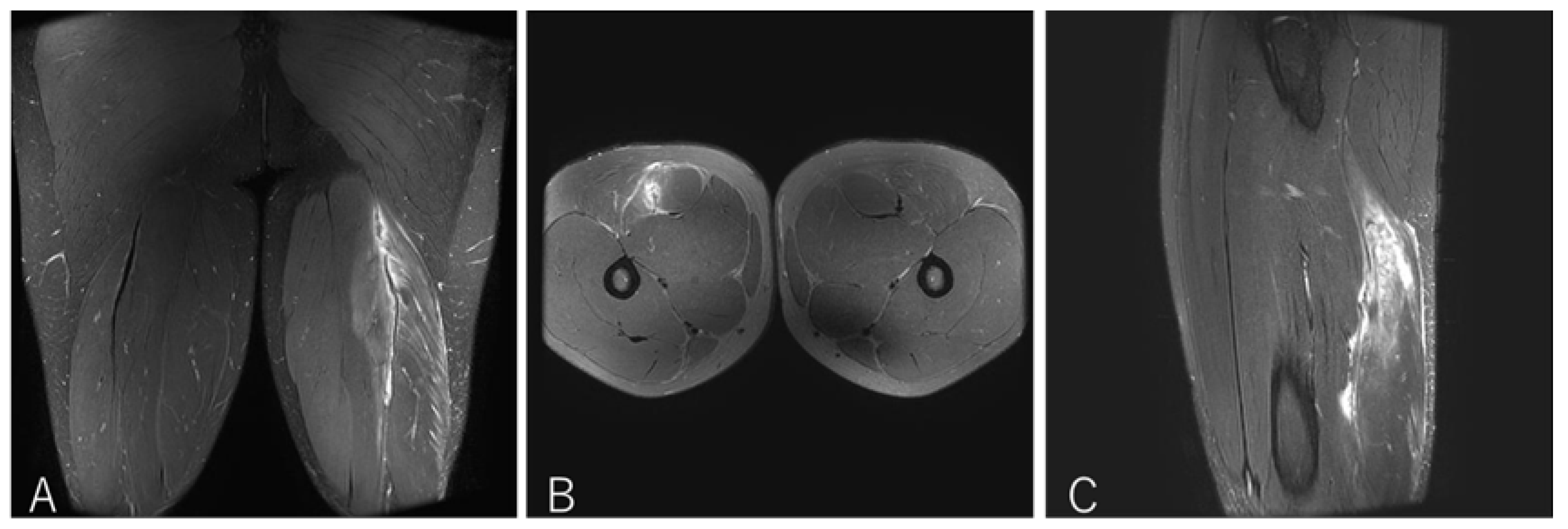

4.2. Case 2. Type I / Zone B (Conjoint tendon tear), Grade 3

A 20-year-old flanker (FW) experienced sharp twisting pain during a 30-m sprint drill while running at top speed. He returned to play after 14 weeks.

Figure 4.

Case 2 MRI images: Conjoint tendon tear, Type I.

Figure 4.

Case 2 MRI images: Conjoint tendon tear, Type I.

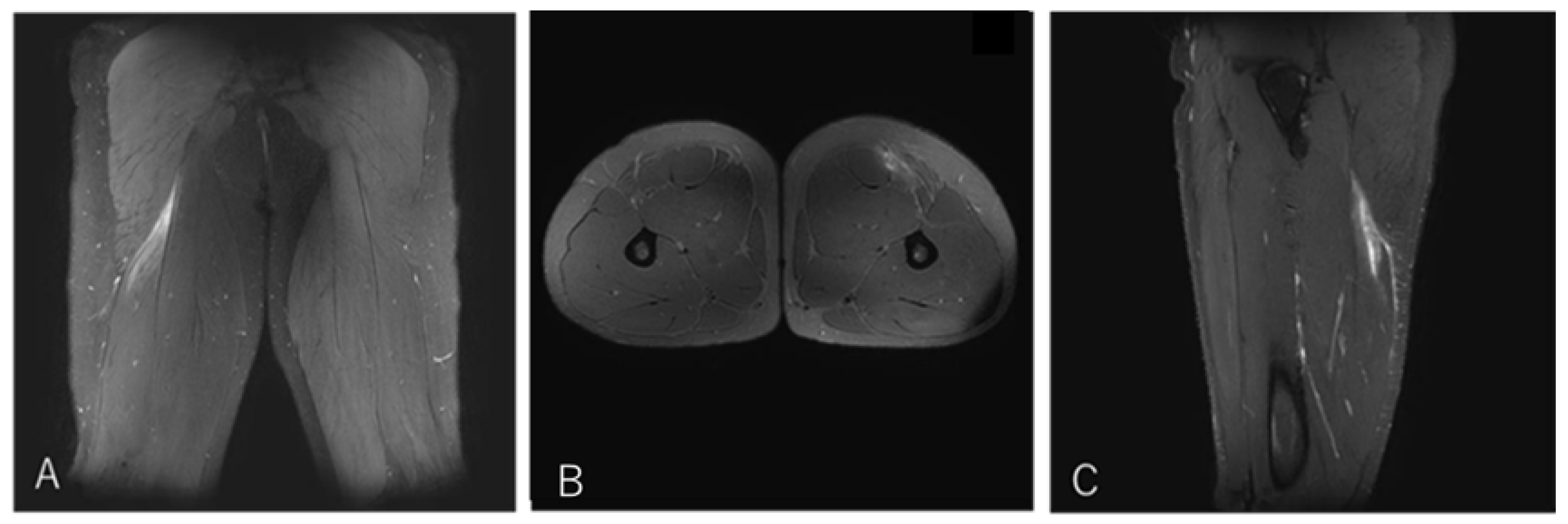

4.3. Case 3. Type I / Zone C (MTJ injury), Grade 2

A 21-year-old scrum half (BK) developed pain in the proximal posterior thigh while changing direction to chase an opposing player. He returned to play after 10 weeks.

Figure 5.

Case 3 MRI images: Conjoint tendon MTJ injury, Type I.

Figure 5.

Case 3 MRI images: Conjoint tendon MTJ injury, Type I.

4.4. Case 4. Type II / Zone C (Proximal MTJ Tear), Grade 2

A 20-year-old center (BK) developed posterior thigh pain during a match while tackling an opponent. He returned to play after three weeks.

Figure 6.

Case 4 MRI images: BFLH proximal MTJ injury, Type II.

Figure 6.

Case 4 MRI images: BFLH proximal MTJ injury, Type II.

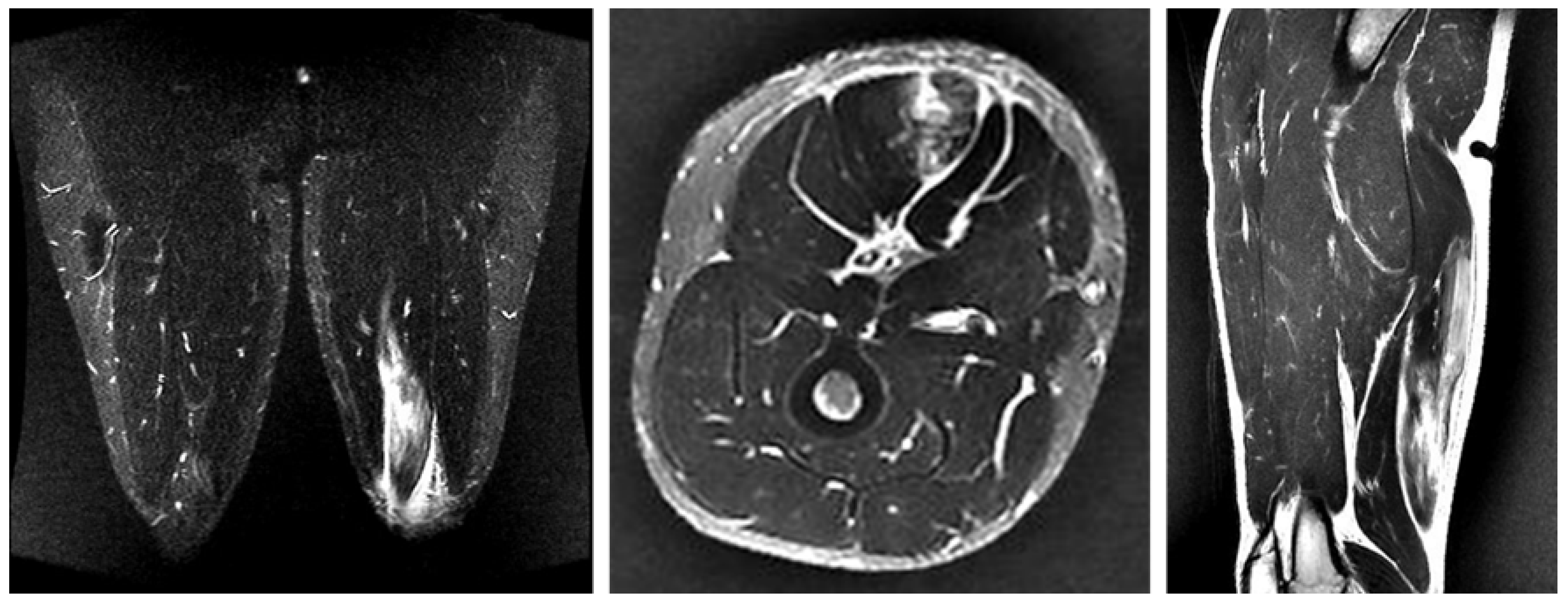

4.5. Case 5. Type II / Zone C (Proximal MTJ Tear), Grade 3

A 20-year-old wing (BK) developed sharp pain accompanied by a snapping sensation while accelerating from a low crouching position during a match. He returned to competition after nine weeks.

Figure 7.

Case 5 MRI images: BFLH proximal MTJ injury, Type II.

Figure 7.

Case 5 MRI images: BFLH proximal MTJ injury, Type II.

4.6. Case 6. Type III / Zone E (Distal MTJ tear), Grade 2

A 20-year-old center (BK) developed thigh pain while running with the ball during a match. He returned to competition after six weeks.

Figure 8.

Case 6 MRI images: ST distal MTJ injury, Type III.

Figure 8.

Case 6 MRI images: ST distal MTJ injury, Type III.

5. Discussion

This study found that in ST–BF complex injuries, Type I (conjoint tendon injury involving the shared origin of the ST and BFLH) had a significantly longer RTP than the other injury types (Type II and Type III) (

Table 1). Significant differences were also observed between Type I and Type II injuries in Zone C, the musculotendinous junction of the conjoint tendon (

Table 2).

5.1. Anatomical and Biomechanical perspectives of the BF-ST complex

The conjoint tendon (CT) is a proximal tendinous structure shared at the ischial tuberosity by the lateral hamstring, the long head of the biceps femoris (BFLH), and the medial hamstring, the semitendinosus (ST) [

12,

13,

26,

27,

28]. In addition, the semimembranosus (SM) attaches independently in the same region [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Higashihara’s electromyographic study of 13 male sprinters revealed that during the early stance of the acceleration sprint, the hip extension torque was significantly greater than during the maximum-speed sprint, and the relative EMG activation of the BFlh muscle was significantly higher than that of the ST muscle, furthermore during the late stance and terminal mid-swing of maximum-speed sprint, the knee was more extended and a higher knee flexion moment was observed compared to the acceleration sprint, and the ST muscle showed higher activation than that of the BFlh. [

17,

34]. Ono reported, based on electromyography and muscle functional MRI, that hip extension relies more on the BF and SM than on the ST [

19]. During the terminal phase of sprinting and change-of-direction movements (late swing to early ground contact), BFLH generates an external rotation moment, whereas ST and SM generate internal rotation moments, creating opposing tensile forces concentrated in the central portion of the CT [

18,

35]. These opposing forces may destabilize tendon fiber realignment during the healing process, increasing the risk of scar formation and re-rupture. These findings support our hypothesis that the CT, subjected to opposing traction forces from its medial (ST) and lateral (BFLH) components, contributes to delayed healing and prolonged time to return to competition.

5.2. Zone C (Proximal MTJ Injury): Unilateral or Bilateral?

We investigated the frequency and recovery time of three injury patterns in Zone C, the musculotendinous junction: unilateral BFLH injury, unilateral ST injury, and bilateral injury involving both the BFLH and ST. In this study, there were no cases of unilateral ST injury in Zone C, and bilateral injuries resulted in longer recovery times than unilateral BFLH injuries. Pollock et al. (2014) classified hamstring strain morphology into myofascial injuries, myotendinous injuries, and intratendinous injuries of the BFLH [

24]. This supports the notion that Type I injuries, being intratendinous in nature, require a longer recovery period. He reported that intratendinous injuries take the longest to heal because of poor blood supply and the characteristics of the extracellular matrix [

29]. This suggests that unilateral injuries correspond to myotendinous injuries, whereas bilateral injuries correspond to intratendinous injuries. In other words, bilateral injuries at the musculotendinous junction share the structural characteristic that tendon healing is prolonged. Balius et al. [

36] explained delayed tendon repair in terms of impaired ECM remodeling: the ECM provides mechanical strength and elasticity to tendon tissue, and after injury it requires a long time to synthesize and reorganize collagen types I and III. In particular, the ECM in tendons is hypometabolic, and the rate of tendon repair is significantly slower than that of muscle fiber injury, leading to delayed RTP [

37].

5.3. Location of Conjoint Tendon Injury and Return to Play

How much difference in recovery time should be expected depending on the specific site of injury within the proximal conjoint tendon, which serves as the shared origin for the medial (ST) and lateral (BFLH) hamstrings? Although Zone A included only one case, the Grade 2 injury in this zone required 20 weeks for RTP. This recovery time was clearly longer than that of injuries in Zones B and C. In other words, injuries at the insertion of the conjoint tendon took significantly longer to recover than injuries to the tendon substance itself. No clear difference was observed between Zones B and C. This study found that even for musculotendinous junction injuries, when both the ST and BFLH were involved, the recovery time was similar to that of Zone B injuries, which involve the free tendon of the BFLH (

Table 3). Askling (2007) [

8] reported that BFLH injuries closer to the ischial tuberosity required longer recovery times. Considering Zone C injuries as those involving either the BFLH alone or both the BFLH and ST (N = 15), the mean RTP was 7.7 weeks, showing a pattern of Zone A > Zone B > Zone C, consistent with the findings of the present study.

5.4. Injury Mechanism and Player’s Position

The injury mechanism in this study was predominantly muscle strain occurring during running, with few stretch-type injuries involving the hamstrings, which are more likely to occur during actions such as mauls. Regarding player position, injuries were more common among backs (positions 9–15) than forwards (positions 1–8). These findings are consistent with previous reports by Askling [

8,

38]. These anatomical and physiological factors, together with previous findings, support the conclusion that RTP following conjoint tendon injuries is prolonged.

5.5. Comparison With Previous Classifications and Novelty

Numerous classifications for hamstring injuries have been proposed. In the Munich Consensus by Müller-Wohlfahrt et al. (2013), injury morphology was divided into functional and structural injuries, with structural injuries further classified in detail by site and extent [

25]. The BAMIC classification by Pollock et al. (2014) categorizes injury sites into myofascial, myotendinous, and intratendinous types, and assigns a severity grade from 0 to 4 [

24]. Although these existing classifications have been useful and have contributed to the standardization of injury location and severity, none specifically distinguishes injuries of the conjoint tendon (CT), which is shared by the BFLH and ST.

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study to identify full-layer CT injuries as a distinct entity and to quantitatively demonstrate their significant impact on RTP in competitive athletes. In this study, we focused on the ST–BF complex, which shares a proximal conjoint tendon, and classified injuries into three categories: Type I, full-layer conjoint tendon tear involving both the BFLH and ST; Type II, BFLH-only injury; and Type III, ST-only injury. The key novelty of this classification is that it enables clear assessment of the presence or absence of conjoint tendon injury and provides clinically relevant information directly related to RTP prediction. In particular, this study differs from previous classifications in demonstrating that Type I injuries have a significantly longer RTP than the other injury types.

6. Limitations

This study was conducted in a single cohort of university rugby players, and the sample size was relatively small, particularly for Type III injuries, which limits the statistical power of between-group comparisons. Further research is needed to determine whether these findings can be generalized to athletes in other sports or competitive levels.

MRI examinations were performed using both 1.5- and 3.0-Tesla scanners, and although all scans were interpreted by two experienced clinicians, differences in image resolution may have influenced the detection of subtle intratendinous alterations. In addition, MRI was obtained within seven days of injury, but the variation in imaging timing may have affected the assessment of edema, hemorrhage, or early tendon discontinuity.

The classification of injury Type, Zone, and Grade was performed by experienced physicians; however, inter-rater reliability was not formally assessed. Finally, RTP was defined as full return to team training or match play, which may be influenced by team circumstances, coaching decisions, and player position, rather than reflecting purely biological healing.

7. Conclusions

This prospective study demonstrates that full-layer conjoint tendon tears involving both the BFLH and ST result in markedly prolonged RTP compared with isolated BFLH or ST injuries. By distinguishing conjoint tendon injuries as a separate category within the BF–ST complex, this classification provides clinically useful information for prognosis and RTP planning. Future studies with larger and more diverse athletic populations are needed to validate this classification and clarify RTP differences across injury Zones and severity grades.

References

- Agre, J.C. Hamstring Injuries. Sports Medicine 1985, 2, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstrand, J.; Waldén, M.; Hägglund, M. Hamstring Injuries Have Increased by 4% Annually in Men’s Professional Football, since 2001: A 13-Year Longitudinal Analysis of the UEFA Elite Club Injury Study. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Askling, C.; Karlsson, J.; Thorstensson, A. Hamstring Injury Occurrence in Elite Soccer Players after Preseason Strength Training with Eccentric Overload. Scandinavian Med Sci Sports 2003, 13, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opar, D.A.; Williams, M.D.; Shield, A.J. Hamstring Strain Injuries. Sports Med 2012, 42, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, B.; Bourne, M.N.; Van Dyk, N.; Pizzari, T. Recalibrating the Risk of Hamstring Strain Injury (HSI): A 2020 Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Risk Factors for Index and Recurrent Hamstring Strain Injury in Sport. Br J Sports Med 2020, 54, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekstrand, J.; Bengtsson, H.; Waldén, M.; Davison, M.; Khan, K.M.; Hägglund, M. Hamstring Injury Rates Have Increased during Recent Seasons and Now Constitute 24% of All Injuries in Men’s Professional Football: The UEFA Elite Club Injury Study from 2001/02 to 2021/22. Br J Sports Med 2023, 57, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudisill, S.S.; Kucharik, M.P.; Varady, N.H.; Martin, S.D. Evidence-Based Management and Factors Associated With Return to Play After Acute Hamstring Injury in Athletes: A Systematic Review. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine 2021, 9, 23259671211053833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askling, C.M.; Tengvar, M.; Saartok, T.; Thorstensson, A. Acute First-Time Hamstring Strains during High-Speed Running: A Longitudinal Study Including Clinical and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings. Am J Sports Med 2007, 35, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.M. Return to Play After Thigh Muscle Injury: Utility of Serial Ultrasound in Guiding Clinical Progression. Curr Sports Med Rep 2018, 17, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comin, J.; Malliaras, P.; Baquie, P.; Barbour, T.; Connell, D. Return to Competitive Play After Hamstring Injuries Involving Disruption of the Central Tendon. Am J Sports Med 2013, 41, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balius, R.; Bossy, M.; Pedret, C.; Capdevila, L.; Alomar, X.; Heiderscheit, B.; Rodas, G. Semimembranosus Muscle Injuries In Sport. A Practical MRI Use for Prognosis. Sports Med Int Open 2017, 01, E94–E100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linklater JM, Hamilton B, Carmichael J, Orchard J, Wood DG. Hamstring injuries: anatomy, imaging, and intervention. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2010;14(2):131-161. [CrossRef]

- Beltran, L.; Ghazikhanian, V.; Padron, M.; Beltran, J. The Proximal Hamstring Muscle–Tendon–Bone Unit: A Review of the Normal Anatomy, Biomechanics, and Pathophysiology. European Journal of Radiology 2012, 81, 3772–3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, S.L.; Gill, J.; Webb, G.R. The Proximal Origin of the Hamstrings and Surrounding Anatomy Encountered During Repair: A Cadaveric Study. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery 2007, 89, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feucht, M.J.; Plath, J.E.; Seppel, G.; Hinterwimmer, S.; Imhoff, A.B.; Brucker, P.U. Gross Anatomical and Dimensional Characteristics of the Proximal Hamstring Origin. Knee surg. sports traumatol. arthrosc. 2015, 23, 2576–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel-Pérez, M.; Iglesias-Chamorro, P.; Ortiz-Miguel, S.; Ortiz-Sagristà, J.-C.; Möller, I.; Blasi, J.; Agullò, J.; Martinoli, C.; Pérez-Bellmunt, A. Anatomical Relationships of the Proximal Attachment of the Hamstring Muscles with Neighboring Structures: From Ultrasound, Anatomical and Histological Findings to Clinical Implications. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashihara, A.; Nagano, Y.; Ono, T.; Fukubayashi, T. Differences in Hamstring Activation Characteristics between the Acceleration and Maximum-Speed Phases of Sprinting. Journal of Sports Sciences 2018, 36, 1313–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schache, A.G.; Dorn, T.W.; Blanch, P.D.; Brown, N.A.T.; Pandy, M.G. Mechanics of the Human Hamstring Muscles during Sprinting. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2012, 44, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, T.; Higashihara, A.; Fukubayashi, T. Hamstring Functions During Hip-Extension Exercise Assessed With Electromyography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Research in Sports Medicine 2010, 19, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlizzi, J.M.; Nacca, C.R.; Shah, S.S.; Saks, B.; Chilton, M.; MacAskill, M.; Fang, C.J.; Miller, S.L. Acute Proximal Hamstring Tears Can Be Defined Using an Imaged-Based Classification. Arthroscopy, Sports Medicine, and Rehabilitation 2022, 4, e653–e659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, D.A. Imaging Diagnosis and Prognostication of Hamstring Injuries. American Journal of Roentgenology 2012, 199, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzopardi, C.; Almeer, G.; Kho, J.; Beale, D.; James, S.L.; Botchu, R. Hamstring Origin–Anatomy, Angle of Origin and Its Possible Clinical Implications. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma 2021, 13, 50–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada M, Kumai T, Okunuki T, Sugimoto T, Ishizuka K, Tanaka Y. Ultrasound Diagnosis of Hamstring Muscle Complex Injuries: Focus on Originate Tendon Structure—Male University Rugby Players. Diagnostics. 2025;15(1):54. [CrossRef]

- Mueller-Wohlfahrt, H.-W.; Haensel, L.; Mithoefer, K.; Ekstrand, J.; English, B.; McNally, S.; Orchard, J.; Van Dijk, C.N.; Kerkhoffs, G.M.; Schamasch, P.; et al. Terminology and Classification of Muscle Injuries in Sport: The Munich Consensus Statement. Br J Sports Med 2013, 47, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, N.; James, S.L.J.; Lee, J.C.; Chakraverty, R. British Athletics Muscle Injury Classification: A New Grading System. Br J Sports Med 2014, 48, 1347–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, P.M.; Knörr, M.; Geyer, S.; Imhoff, A.B.; Feucht, M.J. Delayed Proximal Hamstring Tendon Repair after Ischial Tuberosity Apophyseal Fracture in a Professional Volleyball Athlete: A Case Report. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2021, 22, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelli, A.; Parenti, M.; Tirone, G.; Spera, M.; Azzola, F.; Zanon, G.; Grassi, F.A.; Jannelli, E. Proximal Avulsion of the Hamstring in Young Athlete Patients: A Case Series and Review of Literature. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, M.J.; Vandersluis, R.; Wood, D.; Banff, M. Surgical Repair of Chronic Complete Hamstring Tendon Rupture in the Adult Patient. Am J Sports Med 1998, 26, 785–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, N.; Kelly, S.; Lee, J.; Stone, B.; Giakoumis, M.; Polglass, G.; Brown, J.; MacDonald, B. A 4-Year Study of Hamstring Injury Outcomes in Elite Track and Field Using the British Athletics Rehabilitation Approach. Br J Sports Med 2022, 56, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Made AD, Almusa E, Whiteley R, et al. The hamstring muscle complex: a review of the anatomy and biomechanics. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(5):354-358. TheHamstringMuscleCompleMade2015_Article_x. [CrossRef]

- Farfán-C, E.; Gaete-C, M.; Olivé-V, R.; Rodríguez-Baeza, A. Common Origin Tendon of the Biceps Femoris and Semitendinosus Muscles, Functional and Clinical Relevance. Int. J. Morphol. 2020, 38, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obey, M.R.; Broski, S.M.; Spinner, R.J.; Collins, M.S.; Krych, A.J. Anatomy of the Adductor Magnus Origin: Implications for Proximal Hamstring Injuries. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine 2016, 4, 2325967115625055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodley, S.J.; Mercer, S.R. Hamstring Muscles: Architecture and Innervation. Cells Tissues Organs 2005, 179, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashihara A, Ono T, Kubota J, et al. Functional differences in the activity of the hamstring muscles during sprinting. J Sports Sci. 2010, 28, 175–182.

- Chumanov, E.S.; Heiderscheit, B.C.; Thelen, D.G. The Effect of Speed and Influence of Individual Muscles on Hamstring Mechanics during the Swing Phase of Sprinting. Journal of Biomechanics 2007, 40, 3555–3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balius, R.; Alomar, X.; Pedret, C.; Blasi, M.; Rodas, G.; Pruna, R.; Peña-Amaro, J.; Fernández-Jaén, T. Role of the Extracellular Matrix in Muscle Injuries: Histoarchitectural Considerations for Muscle Injuries.

- Kjær, M. Role of Extracellular Matrix in Adaptation of Tendon and Skeletal Muscle to Mechanical Loading. Physiological Reviews 2004, 84, 649–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askling, C.M.; Tengvar, M.; Saartok, T.; Thorstensson, A. Proximal Hamstring Strains of Stretching Type in Different Sports: Injury Situations, Clinical and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Characteristics, and Return to Sport. Am J Sports Med 2008, 36, 1799–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Type-specific RTP period (weeks; mean ± SD).

Table 1.

Type-specific RTP period (weeks; mean ± SD).

| Type |

N |

Mean ± SD (weeks) |

p-value vs Type I |

| I |

20 |

11.4 ± 4.8 |

— |

| II |

18 |

5.28 ± 2.4 |

<0.001 |

| III |

3 |

4.00 ± 1.7 |

<0.001 |

Table 3.

Duration of RTP by Zone and Grade for Type I Injuries (weeks; mean ± SD).

Table 3.

Duration of RTP by Zone and Grade for Type I Injuries (weeks; mean ± SD).

| Zone |

Grade |

N |

Mean ± SD (weeks) |

| A |

2 |

1 |

20.0 ± — |

| B |

1 |

2 |

7.5 ± 0.7 |

| B |

2 |

8 |

9.3 ± 2. |

| B |

3 |

6 |

13.7 ± 6.5 |

| C(Bilateral side injury) |

2 |

3 |

12.7 ± 2.5 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).