1. Introduction

Hamstring injuries, particularly acute strains, are among the most common sports-related injuries, accounting for up to 30% of lower-extremity pathologies in athletes[

1,

2]. Accurate diagnosis of these injuries is critical, especially for high-grade strains that often lead to prolonged recovery and delayed return to sports[

3,

4]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is widely regarded as the gold standard for diagnosing hamstring injuries owing to its superior ability to assess the extent and severity of tissue damage[

3,

5]. However, its high cost, limited accessibility, and scheduling delays make it less practical for immediate clinical decision-making[

6,

7].

Ultrasonography offers a rapid, cost-effective, and portable alternative that can be used to diagnose soft tissue injuries[

8,

9]. Recent advances in high-resolution ultrasonography have significantly improved its ability to detect muscle injuries[

10], yet its performance in accurately identifying injury location and extent compared to MRI remains inadequately explored. Moreover, although MRI findings have been associated with recovery timelines[

11,

12,

13], evidence on whether ultrasonography can reliably support similar prognostic assessments is sparse.

For athletes, the ability to quickly and cost-effectively evaluate the location and severity of hamstring injuries immediately after occurrence, as well as to predict the recovery timeline for returning to sports, could be highly beneficial. However, no study has comprehensively evaluated the agreement between ultrasonography and MRI in identifying the location of hamstring injuries, and no study has examined the clinical relevance of these findings in relation to recovery time.

This study addressed these gaps by clarifying the agreement between ultrasonography and MRI for identifying the location and extent of acute hamstring injuries. Additionally, it examined MRI-based differences in recovery times associated with injury characteristics, aiming to provide a comprehensive framework for the diagnostic and prognostic utility of these imaging modalities.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Ethical Considerations

This retrospective observational study was conducted at [Name of the clinic], a tertiary sports clinic specializing in athletic injuries, between April 2019 and March 2022. The study protocol was approved by our Institutional Review Board (IRB approval number: XXXX). An opt-out informed consent approach was employed, adhering to the institutional guidelines and ethical standards.

Study Population

Patients with suspected acute hamstring strain who presented to the clinic during the study period were reviewed retrospectively. To evaluate the agreement between ultrasonography and MRI findings, patients who underwent both ultrasonography and MRI within five days of injury were included. Clinical and imaging data were retrospectively collected from the electronic medical records.

Acute hamstring strain was diagnosed by two experienced orthopedic surgeons following clinical protocols routinely used in the clinic. Patients were assessed for clinical signs such as swelling, tenderness in the posterior thigh, or pain exacerbated by palpation or movement of the affected limb. The presence of one or more of these findings was considered suggestive of hamstring strain. Ultrasonography and MRI were used to confirm the diagnosis, identify the injured muscles, and evaluate the severity and location of the strain. The details of the ultrasonography and MRI procedures are described in this manuscript. Treatment was conducted according to standard protocols, including rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE) during the acute phase. The patients were advised to keep the affected area at rest and gradually resume activities based on their pain levels. Range-of-motion exercises and weight-bearing activities were permitted once the pain at rest subsided, and the patients were instructed to avoid any activities that induced pain. Exercise intensity was gradually increased as tolerated without causing discomfort. Return to sports was determined in collaboration with the team’s trainers and coaches. If there was uncertainty about the timing of the return, the attending orthopedic surgeons at the clinic provided a final assessment.

Patients were included in the study if they had undergone both ultrasonography and MRI, with data available for review. Eligible participants were limited to elite athletes who had either competed in national tournaments or were professionals. Furthermore, patients were required to be capable of attending follow-up visits to the clinic until they returned to athletic activities. The study excluded those with a history of acute hamstring strain on the ipsilateral side. Additionally, patients with simultaneous muscle or skeletal injuries that could compromise clinical or imaging evaluations were excluded.

Hamstring Muscle Diagnosis Using Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography was used to diagnose injuries in the three hamstring muscles: biceps femoris, semimembranosus, and semitendinosus. Examinations were performed during the initial consultation by two orthopedic surgeons with over 10 years of experience in sports orthopedic surgery and the routine use of musculoskeletal ultrasonography in clinical practice. A high-resolution ultrasound machine (SONIMAGE MX1 SNiBLE yb, KONICA MINOLTA JAPAN, INC., Tokyo, Japan) with a linear probe (L11-3) was employed, which had been introduced to the clinic in 2018.

The patients were positioned supine with their hips and knees fully extended, allowing comprehensive scanning of the hamstring muscles from the ischial tuberosity to the knee joint in both the longitudinal and transverse planes. To ensure diagnostic accuracy, ultrasonography was performed on both the injured and uninjured sides for comparison. An abnormality was diagnosed if one or more of the following findings were observed (

Figure 1):

Changes in echogenicity or fiber disruption within the muscle.

Edema or hemorrhage, identified as areas of increased echogenicity with or without visible fiber disruption in orthogonal planes.

Hypoechoic fluid tracking along the fascial layer surrounding the muscle, indicative of intermuscular hematoma.

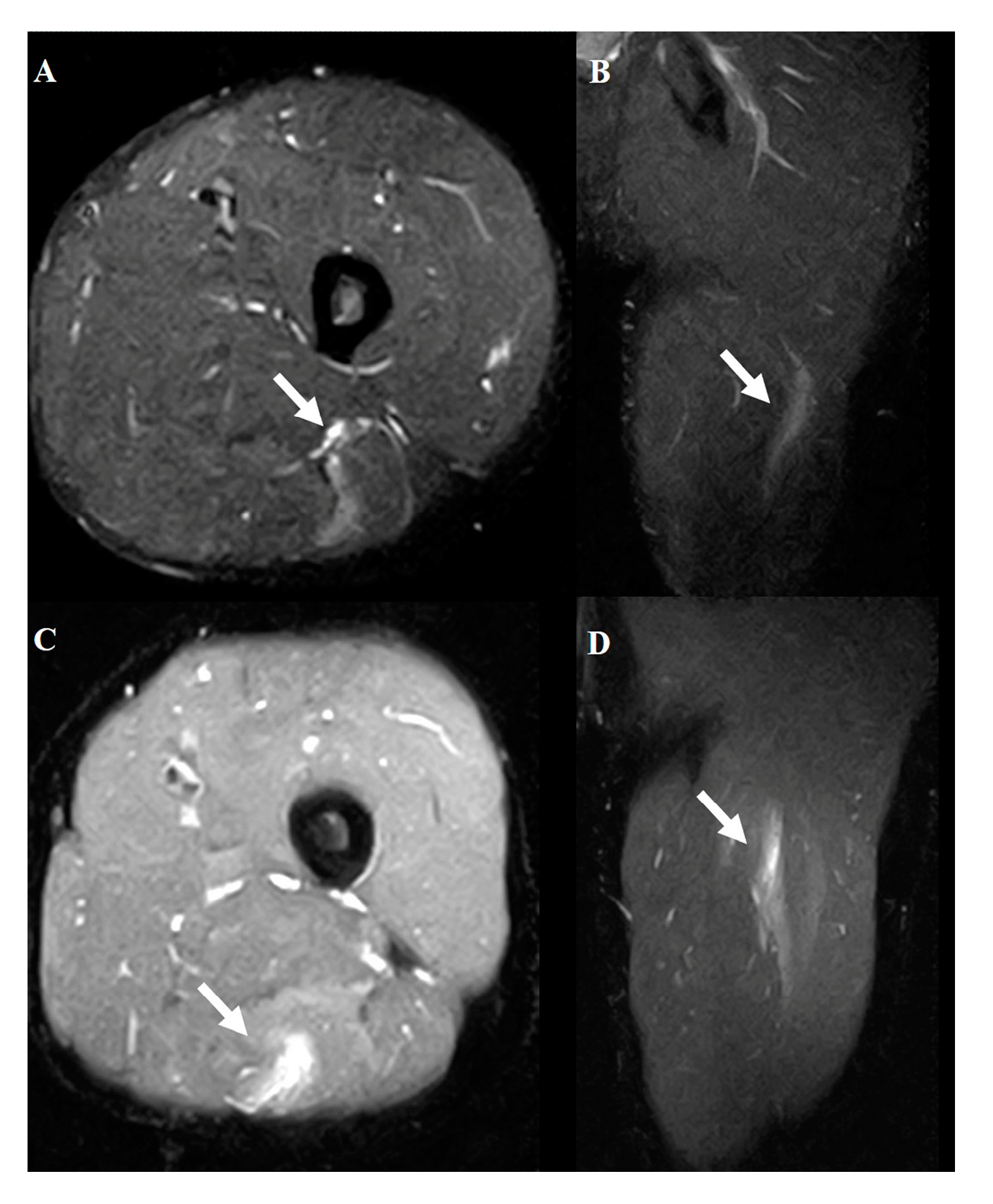

Figure 1.

Typical MRI findings in muscle injury. Axial (A) and coronal (B) views of grade 1. Axial (C) and coronal (D) views of grade 2. The white arrows indicate the injured area.

Figure 1.

Typical MRI findings in muscle injury. Axial (A) and coronal (B) views of grade 1. Axial (C) and coronal (D) views of grade 2. The white arrows indicate the injured area.

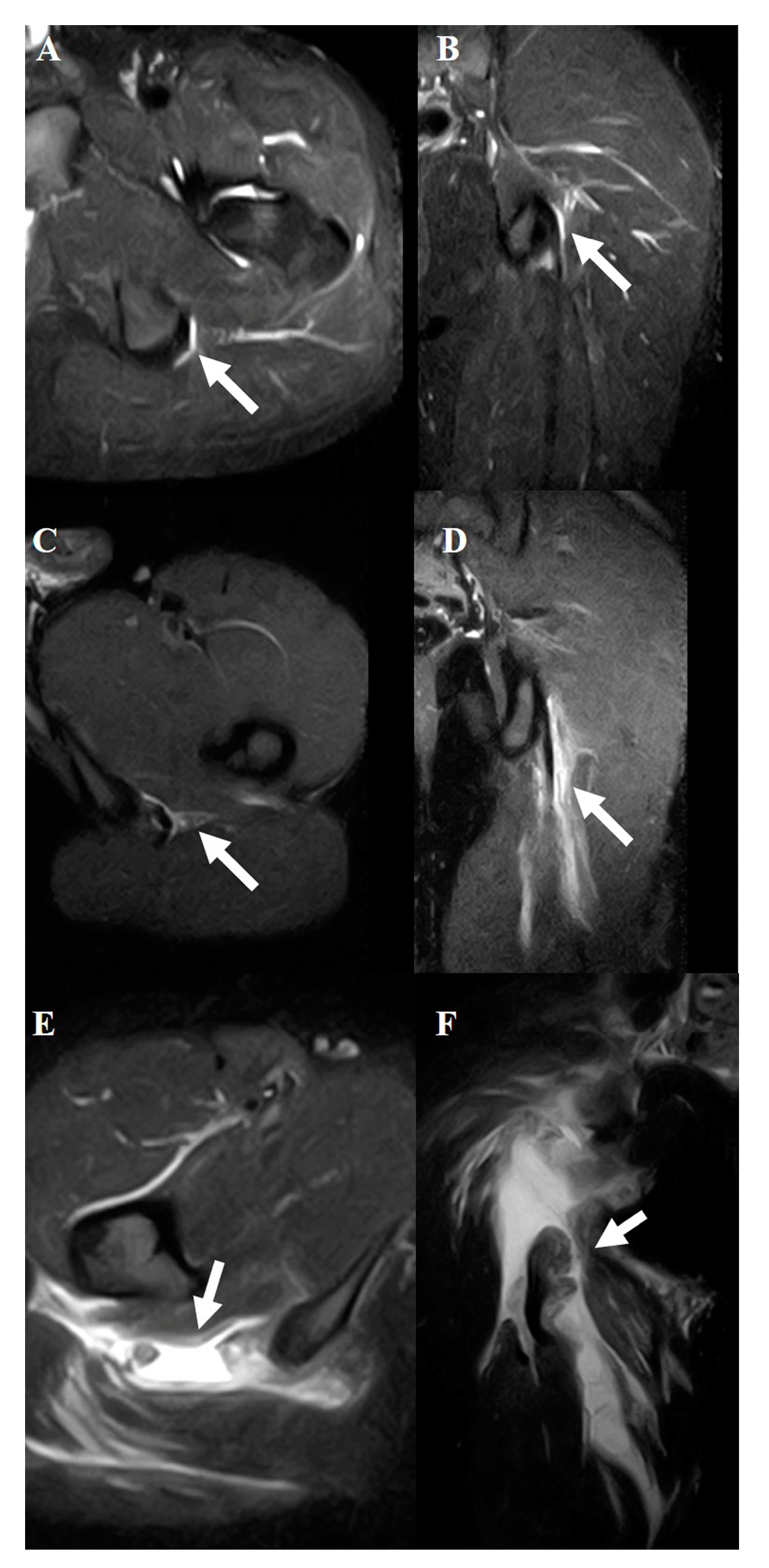

Figure 2.

Typical MRI findings in musculotendinous junction injury.Axial (A) and coronal (B) views of grade 1. Axial (C) and coronal (D) views of grade 2. Axial (E) and coronal (F) views of grade 3. The white arrows indicate the injured area.

Figure 2.

Typical MRI findings in musculotendinous junction injury.Axial (A) and coronal (B) views of grade 1. Axial (C) and coronal (D) views of grade 2. Axial (E) and coronal (F) views of grade 3. The white arrows indicate the injured area.

Figure 3.

Typical MRI findings in tendon injury. Axial (A) and coronal (B) views of grade 1. Axial (C) and coronal (D) views of grade 2. Axial (E) and coronal (F) views of grade 3. The white arrows indicate the injured area.

Figure 3.

Typical MRI findings in tendon injury. Axial (A) and coronal (B) views of grade 1. Axial (C) and coronal (D) views of grade 2. Axial (E) and coronal (F) views of grade 3. The white arrows indicate the injured area.

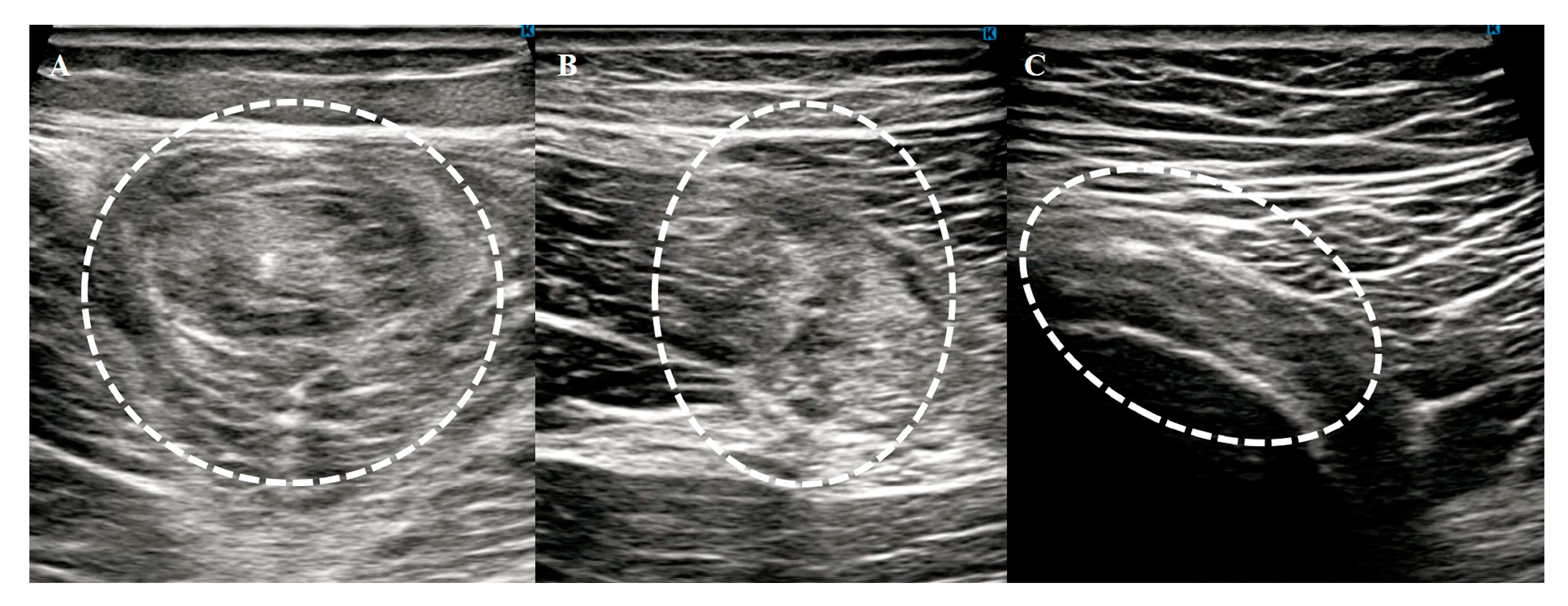

Figure 4.

Typical ultrasonography findings in acute hamstring strain. Muscle (A), musculotendinous junction (B), and tendon (C) injuries. The white dotted circles indicates the injured area.

Figure 4.

Typical ultrasonography findings in acute hamstring strain. Muscle (A), musculotendinous junction (B), and tendon (C) injuries. The white dotted circles indicates the injured area.

Muscle Diagnosis Using MRI

MRI examinations were conducted using a 0.4-T superconducting unit with a quadrature detection coil (APERTO Lucent, Hitachi, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). All scans were performed by a radiology technician with over 20 years of experience in musculoskeletal imaging to ensure the consistency and reliability of the imaging process.

Patients were positioned supine on the examination table. Both hamstrings were scanned bilaterally from the ischial origin of the muscles to their insertions into the fibula and tibia to comprehensively evaluate the injured and uninjured sides. Imaging was performed in the coronal and axial planes by using short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) sequences. Coronal sequences were obtained with a repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE) of 4660/20 ms, field of view of 340 mm, 224 × 224 matrix, 5 mm section thickness, 0.5 mm gap, and echo-train length of 9. The axial sequences were acquired with a TR/TE of 3800/20 ms, field of view of 340 mm, 224 × 224 matrix, 7 mm section thickness, 1.0 mm gap, and an echo-train length of 8.

The diagnostic criteria were based solely on the STIR sequences. These sequences enabled the precise identification of abnormalities such as edema, hemorrhage, and structural disruptions in the hamstring muscles. The evaluation focused on identifying the location of the injury (muscle, musculotendinous junction, or tendon) and grading the severity of the injury using the modified Peetrons classification[

14] as follows: grade 0, negative MRI without visible pathology; grade 1, edema without architectural distortion; grade 2, architectural distortion indicating partial tears; and grade 3, total muscle or tendon rupture.

Evaluation Criteria

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate the agreement between ultrasonography and MRI findings in diagnosing acute hamstring strain, with a particular focus on identifying injured parts, such as the muscle, musculotendinous junction, or tendon, including avulsion injuries. Metrics such as sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value were calculated to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography using MRI as the reference standard.

Additionally, MRI findings were analyzed to explore the distribution of injured muscles, injury locations, and severity. Recovery times for returning to preinjury athletic activities were examined across different injury locations and severity grades. The return-to-sport timeline was defined as the interval between the date of injury and the resumption of athletic activities, including training or competitive games, at the preinjury level. Follow-up consultations and patient interviews provided this information.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic data are described using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Differences in the time to return to sporting activities were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance for comparisons among multiple groups. Bonferroni correction was applied for pairwise comparisons to adjust for multiple testing and identify statistically significant differences. We used STATA (version 16.0; Stata Corp LLC) for all analyses. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided p-value of < 0.05.

3. Results

Ultrasonography’s Diagnostic Accuracy as Part of Agreement Analysis

In a cohort of 109 patients with suspected acute hamstring strain, ultrasonography identified 66 positive cases, whereas MRI confirmed 71 cases. Using MRI as the reference standard, ultrasonography demonstrated a sensitivity of 85%, specificity of 84%, positive predictive value of 91%, and negative predictive value of 73%.

These findings suggest that ultrasonography can be a practical tool for early diagnosis, particularly in clinical settings where MRI access is limited.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

Seventy-one patients met the inclusion criteria and underwent both ultrasonography and MRI to ensure comprehensive data collection. Detailed demographic characteristics are provided in

Table 1, illustrating the distribution of sports participation, age, and sex within the cohort. The injuries were evenly distributed between the right (48%) and left (52%) sides. Rugby was the most frequently associated sport (49%), followed by sprint running (14%) and baseball (13%). The mean age of the patients was 21 years, and 86% were male.

Agreement Between Ultrasonography and MRI, and Clinical Relevance of Injury Location

Ultrasonography showed 70% overall agreement with MRI in identifying injury locations. The agreement rates varied by muscle group, with the semitendinosus showing the highest agreement (100%), followed by the biceps femoris (82%) and semimembranosus (68%). Ultrasonography identified injuries at the musculotendinous junction in 80% of the cases and at the muscle belly in 90% of the cases, showing higher detection rates for these locations than for tendon injuries, with an accuracy of 60%.

The MRI findings revealed that the musculotendinous junction was the most commonly injured site (65%), followed by the tendon (21%) and muscle belly (14%). MRI further revealed that the recovery times differed significantly depending on the injury location, with muscle belly injuries recovering in 16 days, musculotendinous junction injuries in 70 days, and tendon injuries in 83 days (p < 0.01). Further data supporting these findings are presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

Impact of Injury Severity on Return to Sport Based on MRI Analysis

Injury severity was classified using the modified Petron classification system. Grade 1 injuries accounted for 37% of cases, grade 2 for 32%, and grade 3 for 31%. Recovery times increased with injury severity; grade 1 injuries required 35 days, grade 2 injuries required 56 days, and grade 3 injuries required 111 days (P < 0.001). These results highlight the necessity of MRI for the assessment of high-grade injuries. The detailed results are summarized in

Table 4.

Combined Analysis of Injury Location and Severity

Patients were categorized into nine groups based on the MRI-determined injury location (muscle belly, musculotendinous junction, or tendon) and severity (grades 1, 2, or 3). These findings are presented in

Table 5 and

Table 6.

Recovery times showed distinct differences depending on injury location:

Tendon grade 3 injuries required the longest recovery time, averaging 383 days, and differed significantly from all the other groups (p < 0.001).

Musculotendinous junction grade 3 injuries had a recovery time of 100 days, which was significantly longer than that of most of the other groups, except tendon grade 3 (p < 0.01).

Groups with musculotendinous junction grade 2 and tendon grades 1 and 2 showed similar recovery times, ranging from 57 to 65 days.

Muscle grade 1 injuries had the shortest recovery time, averaging 16 days.

Seventy patients received conservative treatment and successfully returned to sports. One patient with a tendon grade 3 injury underwent surgical repair involving tendon reattachment to the ischial tuberosity using suture anchors. This case underscores the challenges of managing high-grade tendon injuries, as the patient required 383 days to fully recover.

4. Discussion

This study highlights the substantial diagnostic utility of high-resolution ultrasonography for acute hamstring injuries, demonstrating 85% sensitivity and 70% agreement with MRI in identifying injury locations. Ultrasonography exhibited high accuracy in diagnosing muscle belly (90%) and musculotendinous junction (80%) injuries, which are commonly associated with shorter recovery times. These findings underscore the potential of ultrasonography as a rapid, accessible, and cost-effective diagnostic tool, particularly in clinical settings where MRI is not readily available.

Although the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography is high, its prognostic value remains unclear. MRI findings, including the extent of muscle tears and the presence of edema, have been strongly correlated with return-to-play timelines[

15,

16]. This study confirms that MRI-identified injury location and severity significantly influence recovery time, whereas the role of ultrasonography in predicting prognosis requires further investigation. Given its real-time imaging capability, ultrasonography may serve as an initial assessment tool for triage cases requiring MRI, particularly for moderate injuries involving the muscle belly and musculotendinous junctions.

The ability to quickly diagnose the injury location and severity is critical for managing acute hamstring injuries, especially in elite athletes who require precise and timely treatment decisions. Ultrasonography is a valuable first-line diagnostic modality owing to its portability and dynamic imaging capabilities. Our findings support its role in cases involving low- to moderate-grade injuries to the muscle belly or musculotendinous junction, where recovery timelines are predictable and relatively short (16–70 days). These results align with those of previous studies demonstrating the reliability of ultrasonography in diagnosing soft tissue injuries in the elbow, knee, and ankle[

8,

9,

17,

18,

19]. However, ultrasonography has shown reduced accuracy (60%) in the diagnosis of tendon injuries, which often involve high-grade damage and prolonged recovery periods. In such cases, MRI is indispensable for assessing the extent of the injury and guiding treatment planning. These observations corroborate earlier studies that reported the limitations of ultrasonography in detecting intratendinous or complex injuries[

6,

20].

MRI has been extensively used to assess the severity of hamstring injuries and to predict return-to-sport timelines. For example, Ekstrand et al. analyzed 516 conservatively treated hamstring injuries and reported significant differences in recovery timelines across grades (grade 0,8 days; grade 1,17 days; grade 2,22 days; and grade 3,73 days; p < 0.0001)

21. Similarly, Cohen et al. found a strong correlation between MRI grades and missed games among professional football players, with grade 3 injuries resulting in the longest absence[

22]. In line with these findings, our study confirmed that MRI-identified injury location and severity significantly influenced recovery time. Tendon grade 3 injuries required the longest recovery time (383 days), while muscle belly injuries required the shortest recovery time (16 days). Moreover, moderate injuries involving the musculotendinous junction (grade 2), tendon (grade 1), and tendon (grade 2) exhibited recovery durations of 57–65 days.

Notably, this study found that musculotendinous junction grade 2, tendon grade 1, and tendon grade 2 injuries had similar recovery times (57–65 days). This suggests that these injury types share common biomechanical and physiological characteristics that influence healing. The clinical implications of this finding warrant further investigation as they may inform rehabilitation strategies and return-to-play decision-making. Future research should explore whether these injury categories respond similarly to treatment and whether additional MRI parameters, such as intramuscular edema patterns or fiber disruption extent, can refine prognostic accuracy.

Additionally, this study provides novel insights by categorizing recovery timelines into nine groups based on injury location and severity. Notably, musculotendinous junction grade 3 and tendon grade 3 injuries required over 100 days for recovery, corroborating the findings of Askling et al., who associated proximal tendon and muscle-tendon junction injuries with longer recovery times23. These detailed classifications offer clinicians a practical framework for setting rehabilitation goals and managing athletes’ expectations. Ultrasonography, particularly in acute settings, can assist in triaging injuries with shorter recovery times such as muscle belly or musculotendinous junction injuries.

This study has several limitations. First, the retrospective design and relatively small sample size for certain injury groups, such as muscle grade 3 and tendon grade 3 injuries, limit the generalizability of our findings. However, further studies with larger cohorts are required to validate these findings. Second, the use of a 0.4-T MRI scanner may have restricted the detection of subtle structural abnormalities, although it was sufficient for evaluating injury location and severity. Third, although ultrasonography was performed by experienced sports orthopedic surgeons, inter- and intra-observer reliabilities were not assessed. Future studies should include these evaluations to establish the diagnostic consistency of ultrasonography. Additionally, as this study focused exclusively on elite athletes, the findings may not be directly applicable to recreational athletes or non-athletic populations. Future investigations should examine whether the diagnostic performances of ultrasonography and MRI vary across different patient demographics and activity levels.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the complementary role of ultrasonography and MRI in the diagnosis and management of acute hamstring injuries. Ultrasonography has high diagnostic accuracy for muscle belly and musculotendinous junction injuries, combined with its accessibility and cost-effectiveness, which support its use as a first-line imaging tool. However, for high-grade injuries, particularly those involving the tendons, MRI is essential for accurate diagnosis and treatment planning. This study highlights the importance of optimizing imaging modality selection. Ultrasonography is effective in diagnosing mild-to-moderate injuries. However, MRI should be prioritized in cases with suspected high-grade tendon involvement, prolonged recovery expectations, or uncertain initial findings. These insights provide a framework for integrating ultrasonography and MRI into evidence-based clinical pathways, ultimately improving outcomes in athletes with hamstring injuries.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, X.X. and Y.Y.; methodology, X.X.; software, X.X.; validation, X.X., Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

Please add: “This research received no external funding” or “This research was funded by NAME OF FUNDER, grant number XXX” and “The APC was funded by XXX”. Check carefully that the details given are accurate and use the standard spelling of funding agency names at

https://search.crossref.org/funding. Any errors may affect your future funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In this section, you should add the Institutional Review Board Statement and approval number, if relevant to your study. You might choose to exclude this statement if the study did not require ethical approval. Please note that the Editorial Office might ask you for further information. Please add “The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving humans. OR “The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving animals. OR “Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Any research article describing a study involving humans should contain this statement. Please add “Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.” OR “Patient consent was waived due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable.” for studies not involving humans. You might also choose to exclude this statement if the study did not involve humans.

Written informed consent for publication must be obtained from participating patients who can be identified (including by the patients themselves). Please state “Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper” if applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

Declare conflicts of interest or state “The authors declare no conflicts of interest.” Authors must identify and declare any personal circumstances or interest that may be perceived as inappropriately influencing the representation or interpretation of reported research results. Any role of the funders in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results must be declared in this section. If there is no role, please state “The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results”.

Abbreviations

| MRI |

magnetic resonance imaging |

References

- Heer, S.T.; Callander, J.W.; Kraeutler, M.J.; Mei-Dan, O.; Mulcahey, M.K. Hamstring injuries: Risk Factors, Treatment, and Rehabilitation. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2019, 101, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerkhoffs, G.M.M.J.; van Es, N.; Wieldraaijer, T.; Sierevelt, I.N.; Ekstrand, J.; van Dijk, C.N. Diagnosis and prognosis of acute hamstring injuries in athletes. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2013, 21, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arner, J.W.; McClincy, M.P.; Bradley, J.P. Hamstring injuries in athletes: evidence-based treatment. J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 2019, 27, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiderscheit, B.C.; Sherry, M.A.; Silder, A.; Chumanov, E.S.; Thelen, D.G. Hamstring strain injuries: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and injury prevention. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2010, 40, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenky, M.; Cohen, S.B. Magnetic resonance imaging for assessing hamstring injuries: clinical benefits and pitfalls – a review of the current literature. Open Access J. Sports Med. 2017, 8, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, D.A.; Schneider-Kolsky, M.E.; Hoving, J.L.; Malara, F.; Buchbinder, R.; Koulouris, G.; Burke, F.; Bass, C. Longitudinal study comparing sonographic and MRI assessments of acute and healing hamstring injuries. A.J.R. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2004, 183, 975–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beek, E.J.R.; Kuhl, C.; Anzai, Y.; Desmond, P.; Ehman, R.L.; Gong, Q.; Gold, G.; Gulani, V.; Hall-Craggs, M.; Leiner, T.; Lim, C.C.T.; Pipe, J.G.; Reeder, S.; Reinhold, C.; Smits, M.; Sodickson, D.K.; Tempany, C.; Vargas, H.A.; Wang, M. Value of MRI in medicine: more than just another test? J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2019, 49, e14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, J.; Thorborg, K.; Nielsen, M.B.; Skjødt, T.; Bolvig, L.; Bang, N.; Hölmich, P. The diagnostic and prognostic value of ultrasonography in soccer players with acute hamstring injuries. Am. J. Sports Med. 2014, 42, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendawi, T.K.; Rendos, N.K.; Warrell, C.S.; Hackel, J.G.; Jordan, S.E.; Andrews, J.R.; Ostrander, R.V. Medial elbow stability assessment after ultrasound-guided ulnar collateral ligament transection in a cadaveric model: ultrasound versus stress radiography. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019, 28, 1154–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.-P.; Wang, T.-G.; Hsieh, S.-F. Application of ultrasound in sports injury. J. Med. Ultrasound 2013, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier-Farley, C.; Lamontagne, M.; Gendron, P.; Gagnon, D.H. Determinants of return to play after the nonoperative management of hamstring injuries in athletes: A systematic review. Am. J. Sports Med. 2016, 44, 2166–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuske, B.; Hamilton, D.F.; Pattle, S.B.; Simpson, A.H.R.W. Patterns of hamstring muscle tears in the general population: A systematic review. PLOS One 2016, 11, e0152855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Horst, N.; van de Hoef, S.; Reurink, G.; Huisstede, B.; Backx, F. Return to play after hamstring injuries: A qualitative systematic review of definitions and criteria. Sports Med. 2016, 46, 899–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peetrons, P. Ultrasound of muscles. Eur. Radiol. 2002, 12, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zein, M.I.; Mokkenstorm, M.J.K.; Cardinale, M.; Holtzhausen, L.; Whiteley, R.; Moen, M.H.; Reurink, G.; Tol, J.L.; Qatari and Dutch Hamstring Study Group. Baseline clinical and MRI risk factors for hamstring reinjury showing the value of performing baseline MRI and delaying return to play: a multicentre, prospective cohort of 330 acute hamstring injuries. Br. J. Sports Med. 2024, 58, 766–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedret, C. Hamstring muscle injuries: MRI and ultrasound for diagnosis and prognosis. J. Belg. Soc. Radiol. 2021, 105, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, G.A.; Jadaan, M.; Harrington, P. Accuracy of ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging for detection of full thickness rotator cuff tears. Int. J. Shoulder Surg. 2009, 3, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhimani, R.; Lubberts, B.; DiGiovanni, C.W.; Tanaka, M.J. Dynamic ultrasound can accurately quantify severity of medial knee injury: A cadaveric study. Arthrosc. Sports Med. Rehabil. 2022, 4, e1777–e1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergün, T.; Peker, A.; Aybay, M.N.; Turan, K.; Muratoğlu, O.G.; Çabuk, H. Ultrasonography vıew for acute ankle ınjury: comparison of ultrasonography and magnetic resonance ımaging. Arch. Orthop. Trauma. Surg. 2023, 143, 1531–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koulouris, G.; Connell, D. Evaluation of the hamstring muscle complex following acute injury. Skelet. Radiol. 2003, 32, 582–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekstrand, J.; Lee, J.C.; Healy, J.C. MRI findings and return to play in football: a prospective analysis of 255 hamstring injuries in the UEFA Elite Club Injury Study. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 738–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.B.; Towers, J.D.; Zoga, A.; Irrgang, J.J.; Makda, J.; Deluca, P.F.; Bradley, J.P. Hamstring injuries in professional football players: magnetic resonance imaging correlation with return to play. Sports Health 2011, 3, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Askling, C.M.; Tengvar, M.; Saartok, T.; Thorstensson, A. Acute first-time hamstring strains during high-speed running: a longitudinal study including clinical and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Am. J. Sports Med. 2007, 35, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics.

| Variable |

Value |

| Number of patients |

71 |

| Sex (% male) |

61 (86%) |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) |

21.0 ± 4.7 (18–48) |

| Injured side (%) |

Right: 48, Left: 52 |

| Sports activity |

Rugby: 49, Sprint: 14, Baseball: 13, Soccer: 11, Judo: 8, Long-distance running: 7, American football: 3, Field events: 2, Tennis: 1, Lacrosse: 1 |

| Time to imaging (hr) |

US: 57.2 ± 59.3, MRI: 88.9 ± 83.1 |

Table 2.

Agreement Between Ultrasonography and MRI in Diagnosing Acute Hamstring Injuries.

Table 2.

Agreement Between Ultrasonography and MRI in Diagnosing Acute Hamstring Injuries.

| Injury Location |

Agreement Rate (%) |

| Overall Agreement |

70 |

| By Muscle Group |

|

| Semitendinosus |

100 |

| Biceps Femoris |

82 |

| Semimembranosus |

68 |

| By Specific Location |

|

| Musculotendinous Junction |

80 |

| Muscle Belly |

90 |

| Tendon |

60 |

Table 3.

MRI Findings and Return-to-Sport Timelines.

Table 3.

MRI Findings and Return-to-Sport Timelines.

| |

Musculotendinous

junction

|

Tendon |

Muscle |

P-value |

| Proportion of Injuries (%) |

65 |

21 |

14 |

|

Time to return to

sporting activity (Days) |

70±36 |

83±90 |

16±8 |

<0.01 |

Table 4.

Relationship Between Injury Severity (MRI Grade) and Return-to-Sport Time.

Table 4.

Relationship Between Injury Severity (MRI Grade) and Return-to-Sport Time.

| |

Grade 1 |

Grade 2 |

Grade 3 |

P-value |

| Proportion of Injuries (%) |

37 |

32 |

31 |

|

The time to return to

sporting activity (Days) |

35±28 |

56±28 |

111±67 |

<0.01 |

Table 5.

Combined Analysis of Injury Location and Severity.

Table 5.

Combined Analysis of Injury Location and Severity.

| Injured Part |

Grade |

Number of Patients |

Return to Sporting Activity (Days, Mean ± SD) |

| Muscle |

1 |

8 |

17 ± 8 |

| |

2 |

1 |

8 ± 0 |

| |

3 |

0 |

|

| Musculotendinous Junction |

1 |

10 |

31 ± 13 |

| |

2 |

17 |

57 ± 21 |

| |

3 |

20 |

100 ± 27 |

| Tendon |

1 |

6 |

65 ± 39 |

| |

2 |

8 |

59 ± 37 |

| |

3 |

1 |

383 ± 0 |

Table 6.

Summary of Ultrasonography and MRI Utility in Diagnosing Hamstring Injuries.

Table 6.

Summary of Ultrasonography and MRI Utility in Diagnosing Hamstring Injuries.

| Group |

Muscle Grade 1 |

Muscle Grade 2 |

Musculotendinous Grade 1 |

Musculotendinous Grade 2 |

Musculotendinous Grade 3 |

Tendon Grade 1 |

Tendon Grade 2 |

Tendon Grade 3 |

| Muscle Grade 2 |

n.s. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Musculotendinous Grade 1 |

n.s. |

n.s. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Musculotendinous Grade 2 |

<0.05 |

n.s. |

n.s. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Musculotendinous Grade 3 |

<0.001 |

<0.05 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

|

|

|

|

| Tendon Grade 1 |

<0.05 |

n.s. |

n.s. |

n.s. |

n.s. |

|

|

|

| Tendon Grade 2 |

<0.05 |

n.s. |

n.s. |

n.s. |

n.s. |

<0.01 |

|

|

| Tendon Grade 3 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

<0.001 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).