Submitted:

24 July 2025

Posted:

25 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The Munich consensus statement [12], which differentiates, among indirect muscle injuries, functional disorders (type 1a = fatigue-induced functional disorders; type 1b = delayed onset muscle soreness – DOMS; types 2a and 2b = neuromuscular disorders of central or peripheral origin) and structural lesions (type 3a = minor partial muscle injury; type 3b = moderate partial injury; type 4 = (sub) total muscle ruptures and tendon avulsions).

- The British Athletics Muscle Injury Classification (BAMIC) [13], proposes to associate, on the one hand, the extent of the injury according to 5 progressive lesion stages based on magnetic resonance imaging (stage 0 = DOMS; stage 1 = minimal lesion in terms of longitudinal dimensions of the injury and percentage of fibers involved; stage 2 = moderate lesion; stage 3 = extensive lesion; stage 4 = complete lesion) and, on the other hand, the site of the lesion (a = myofascial; b = muscular/musculotendinous; c = intratendinous).

- The acronym MLG-R, resulting from a collaboration between FC Barcelona and “Aspetar”, this classification refers to the use of four letters: M for mechanism of injury (direct, indirect “sprinting-type” or indirect “stretching-type”), L for location (proximal, middle or distal third of the muscle), G for grade (lesion stages 0 to 3) and R for number of recurrences (0 = first episode; 1 = first recurrence) [14].

- While there are three major classification systems for hamstring (HSI) injuries that incorporate anatomical and imaging criteria, these classification systems are not specific to any individual athlete's individual muscle injuries.

- Specialists most frequently use the British Athletics Muscle Injury Classification (BAMIC) system, but the Munich and Barcelona systems are also considered valid for the classification of musculoskeletal injuries (HSI).

- The expert panel reports that MRI is the recommended diagnostic test, while few use diagnostic ultrasound. However, neither is recommended for monitoring rehabilitation progress or assessing readiness to return to sports (RTS).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Aspects and Eligibility Criteria

- Clinical and MRI-confirmed diagnosis of proximal biceps femur tendinopathy.

- Age between 18 and 50 years.

- Acute symptoms present for less than 3 months.

- Active or athletic individuals.

- Subject had not previously undergone reconstructive or conservative surgical treatments.

- They had not benefited from infiltrative and/or other conservative treatment.

- They had no other concomitant pathologies within PHT.

- They completed treatment with MD-Muscle (Guna spa, Milano, Italy).

- Complete tendon tears.

- Previous local injections or regenerative treatments.

- Rheumatologic or neurologic comorbidities.

- Known allergy to collagen or components of the product.

- Refusal to sign consent or poor compliance with follow-up.

2.1. Data Assessment

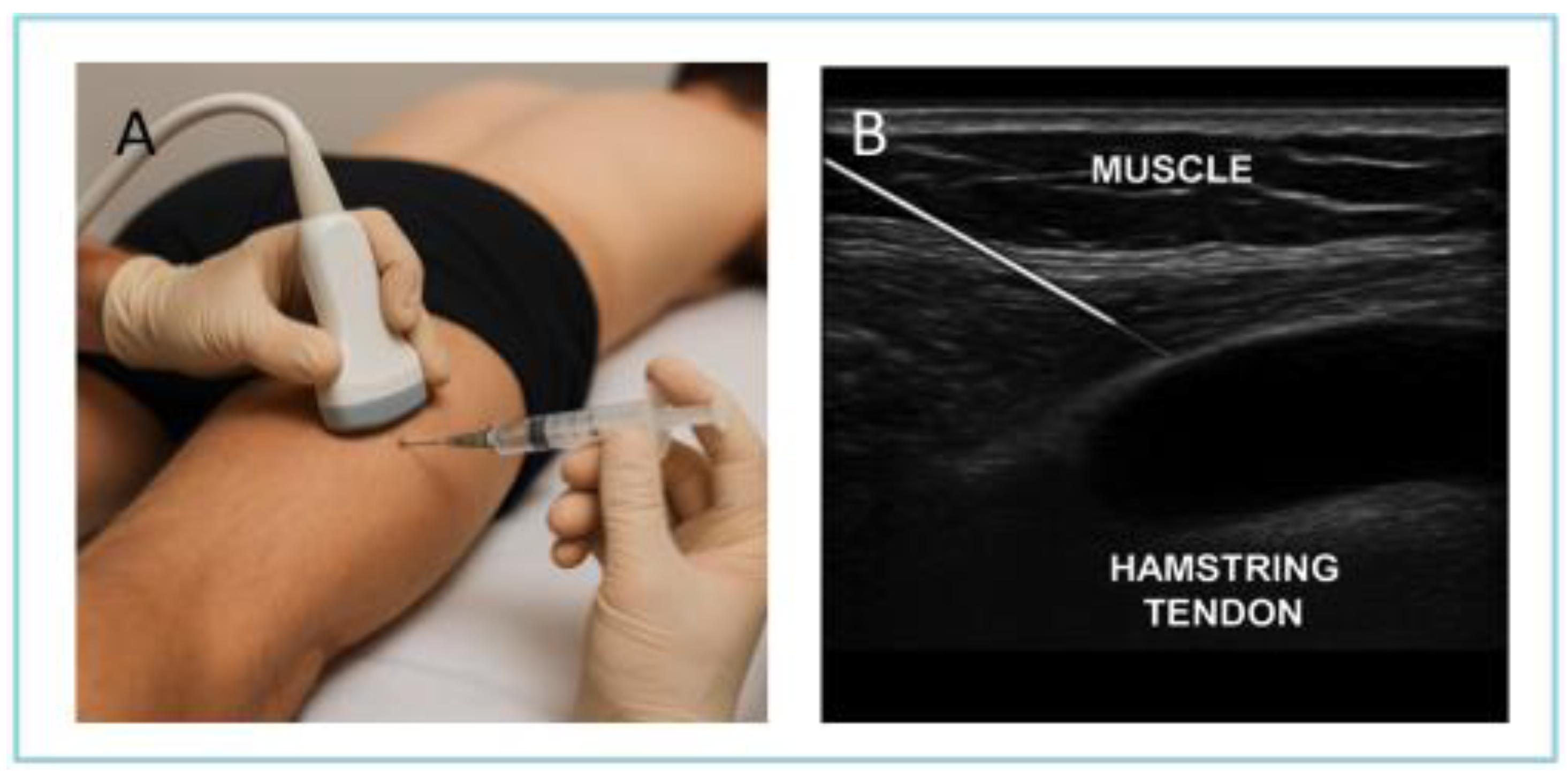

2.1. Treatment and Technical Procedure

2.4. Follow-Up and Score Evaluation the Follow-Up Duration

2.1. Statistical Procedures

2.5.1. General Methodology

2.5.2. Study Variables

2.5.3. Analytical Test Application (ATA)

3. Results

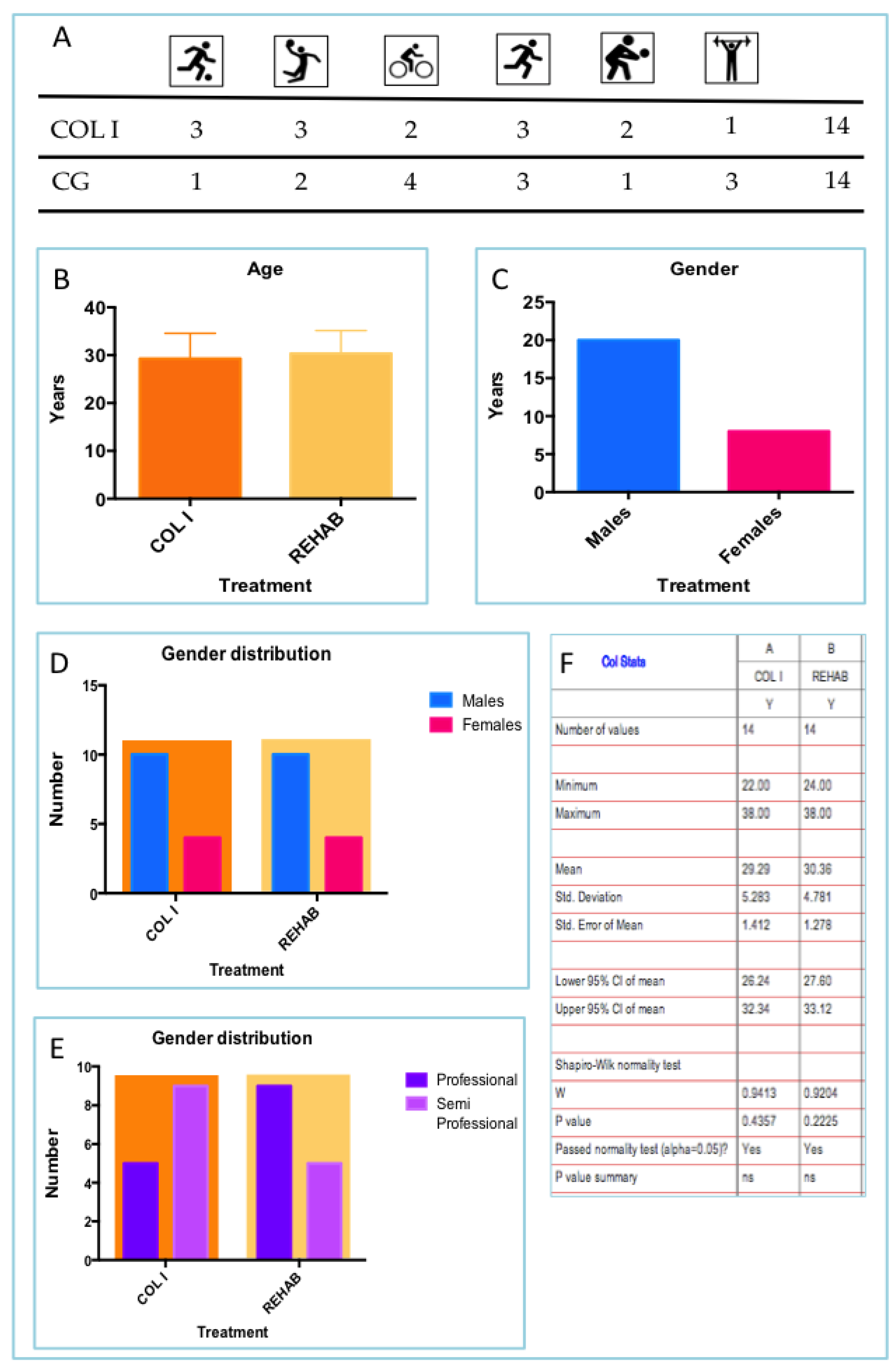

3.1. Athletes Distribution

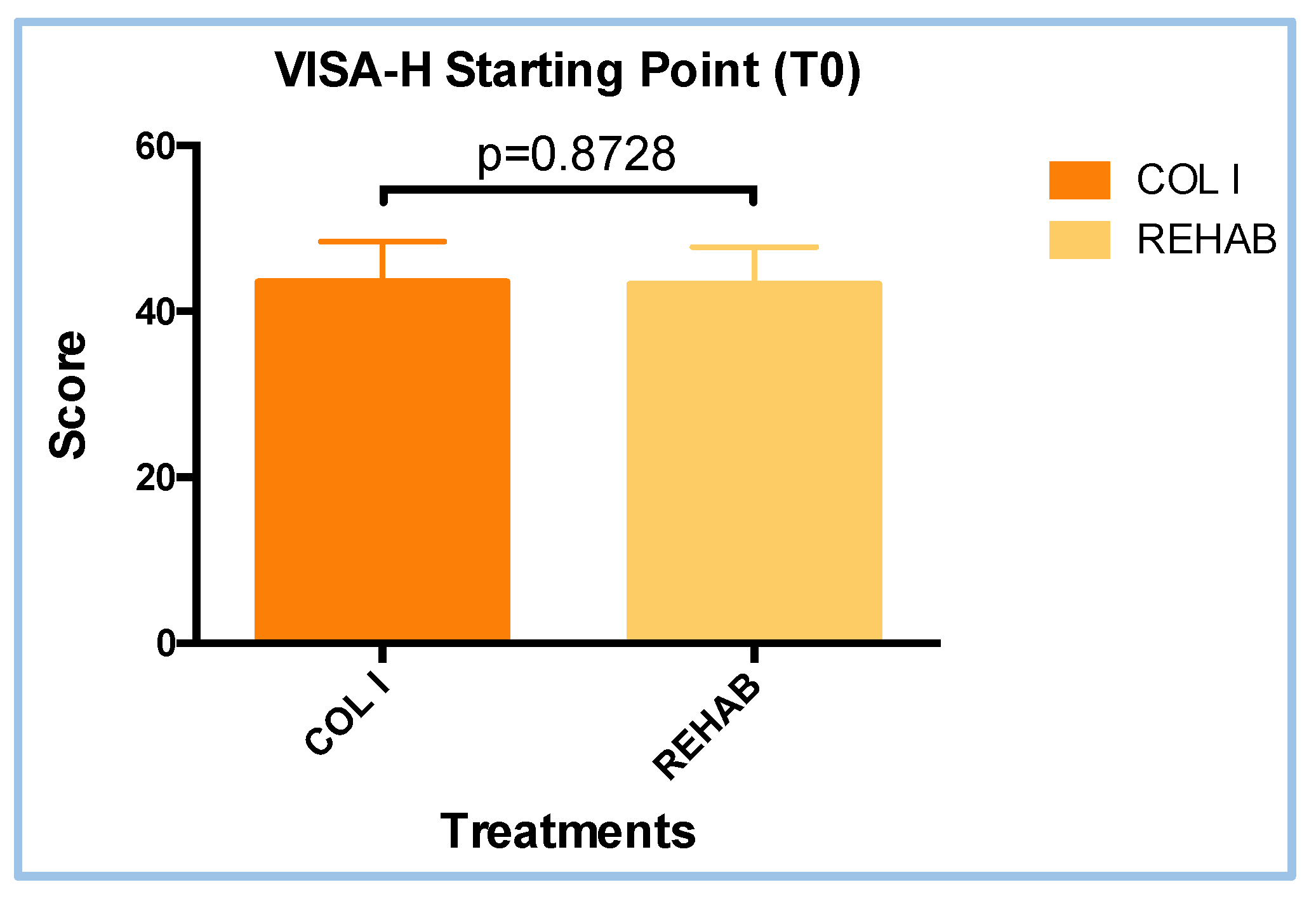

3.1. VISA-H Questionnaire Scores at T0 Visit

3.1. Follow-Up

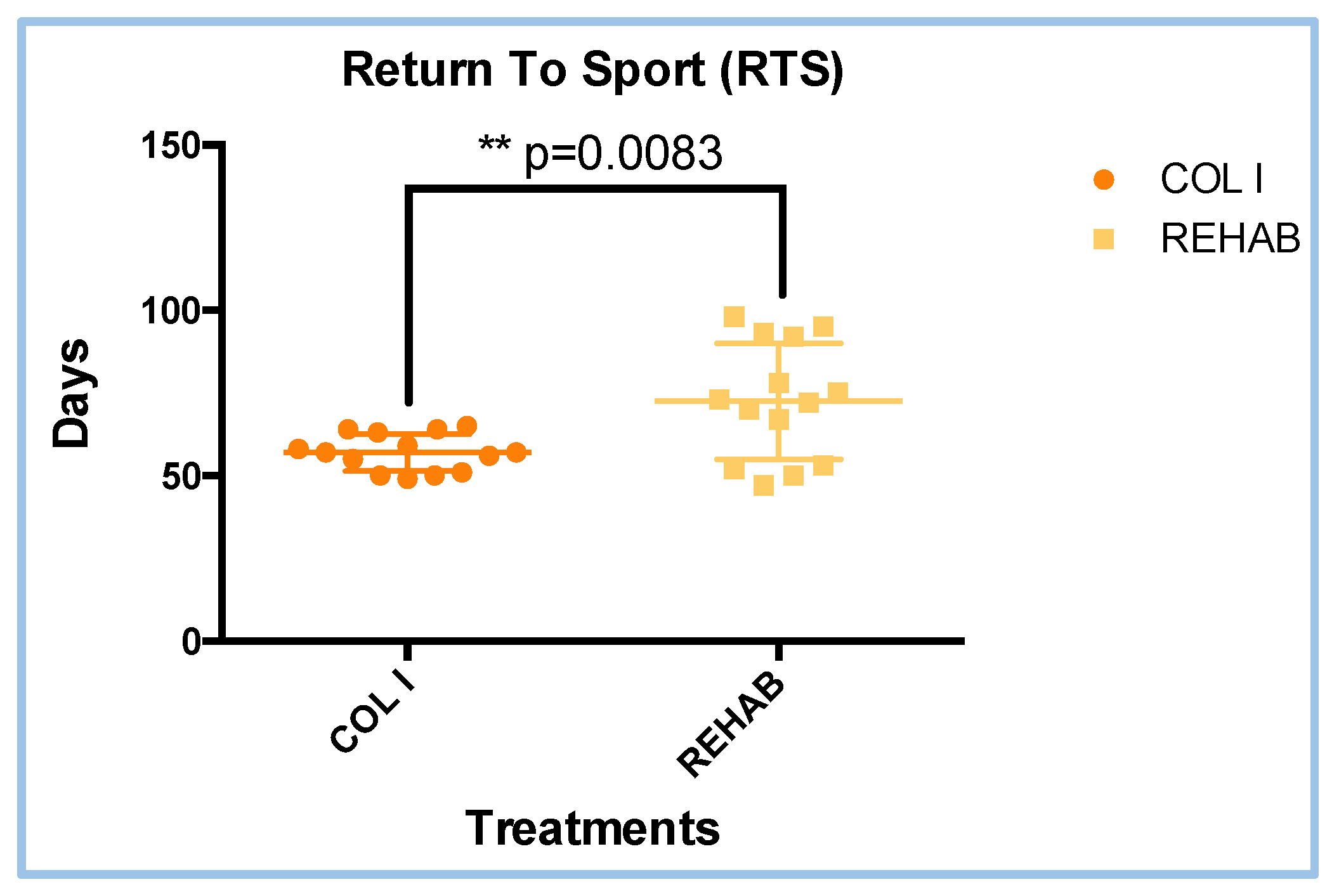

3.1. Return to Sports (RTS) Results

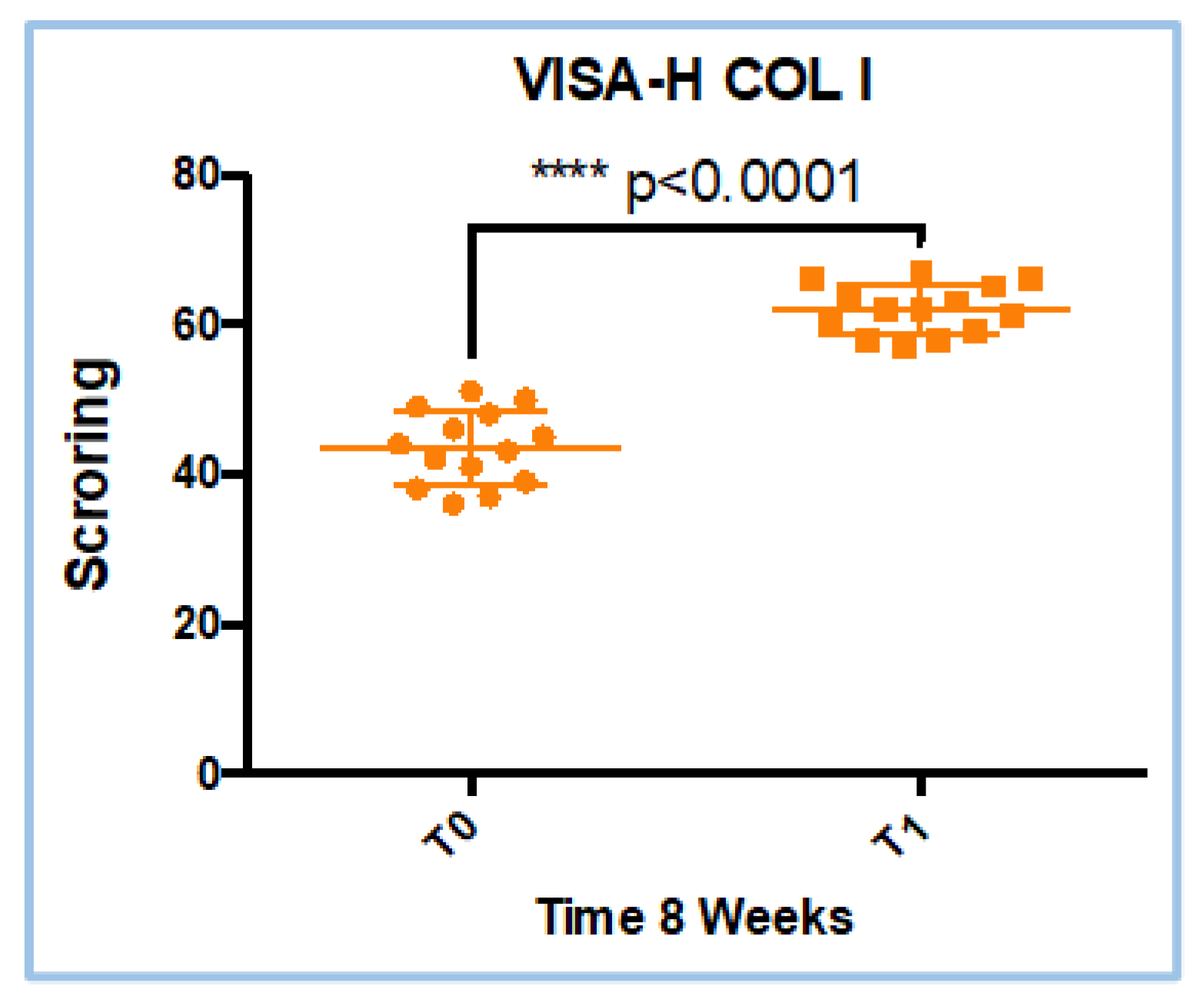

3.1. VISA-H Score Results in COL I Treatment

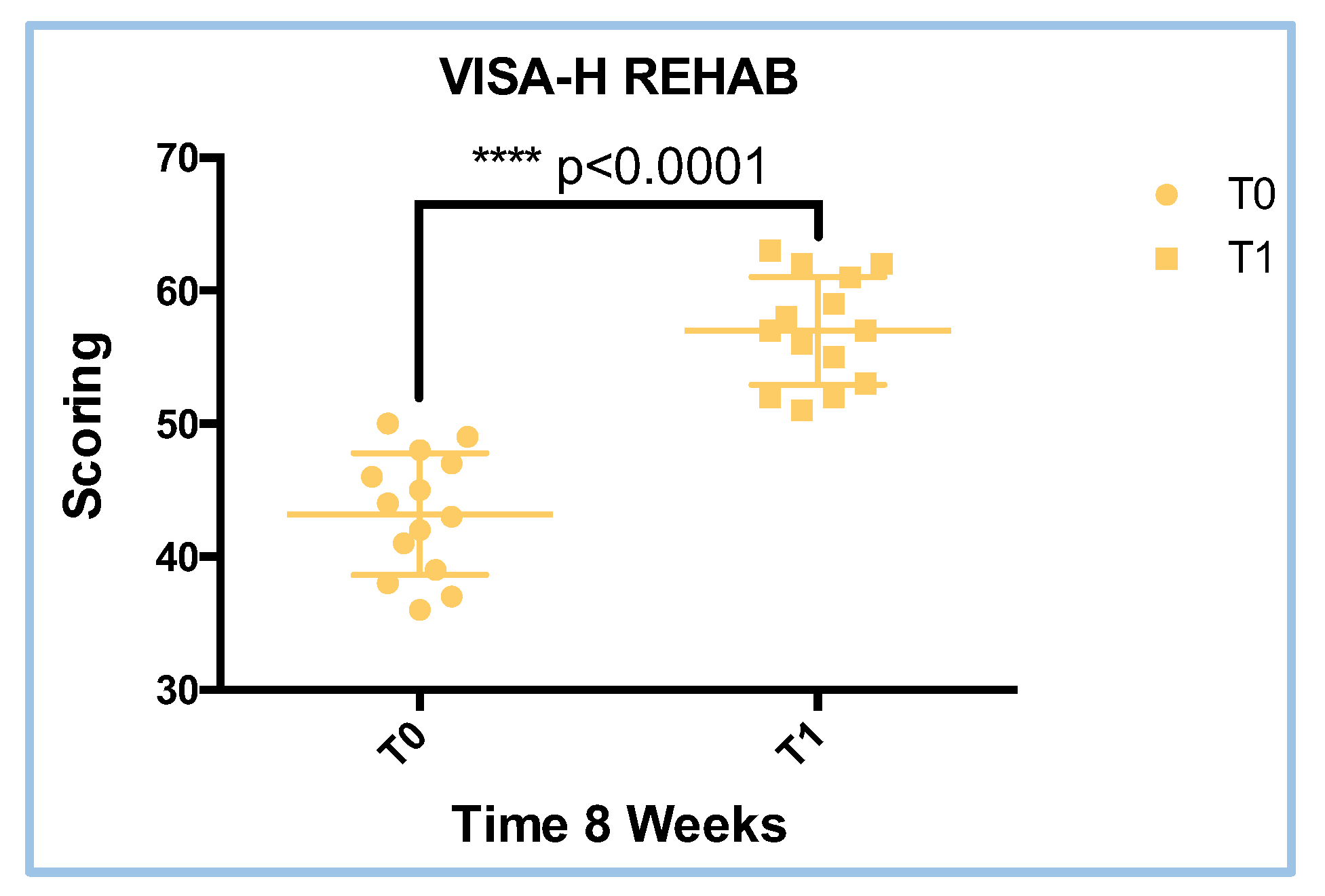

3.1. VISA-H Score Results in REHAB Treatment

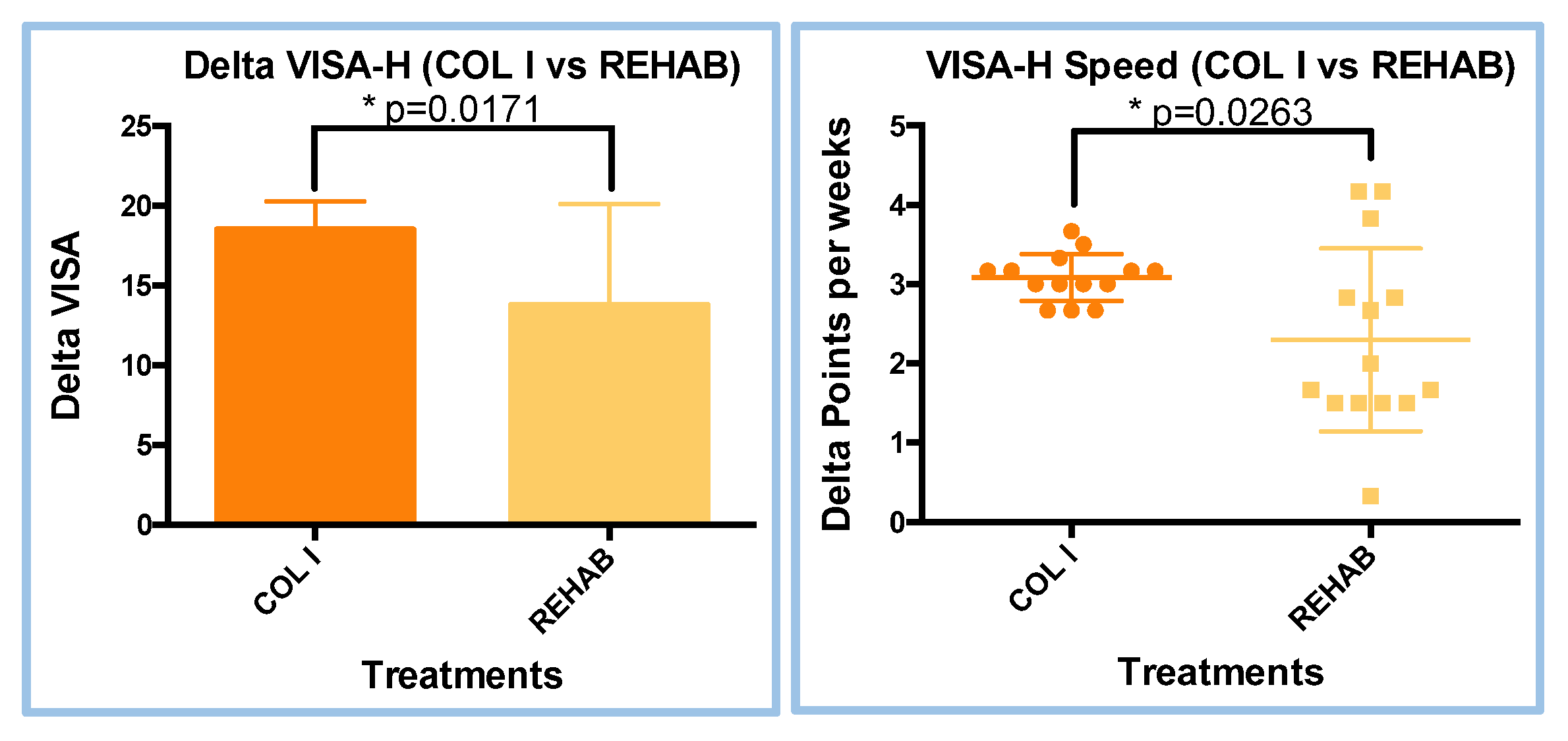

3.1. VISA-H Analyses (Delta an Speed Evaluation)

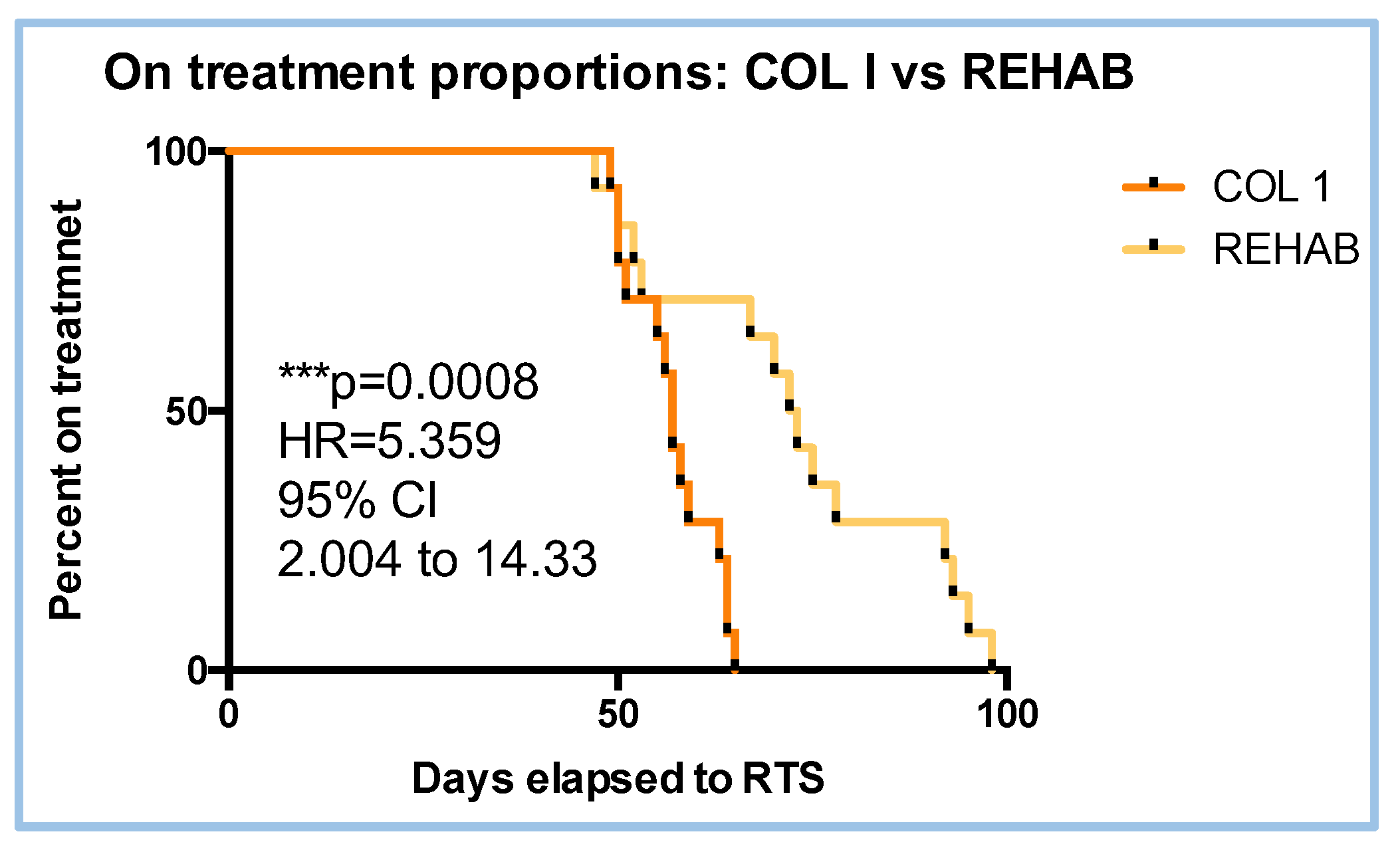

3.1. Proportion and Hazard Ratio (HR) to RTS

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Waldén, M.; Hägglund, M.; Magnusson, H.; Ekstrand, J. ACL Injuries in Men’s Professional Football: A 15-Year Prospective Study on Time Trends and Return-to-Play Rates Reveals Only 65% of Players Still Play at the Top Level 3 Years after ACL Rupture. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 744–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roe, M.; Murphy, J.C.; Gissane, C.; Blake, C. Hamstring Injuries in Elite Gaelic Football: An 8-Year Investigation to Identify Injury Rates, Time-Loss Patterns and Players at Increased Risk. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 982–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertiche, P.; Mohtadi, N.; Chan, D.; Hölmich, P. Proximal Hamstring Tendon Avulsion: State of the Art. J. ISAKOS 2021, 6, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biz, C.; Nicoletti, P.; Baldin, G.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Crimì, A.; Ruggieri, P. Hamstring Strain Injury (HSI) Prevention in Professional and Semi-Professional Football Teams: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 8272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiderscheit, B.C.; Hoerth, D.M.; Chumanov, E.S.; Swanson, S.C.; Thelen, B.J.; Thelen, D.G. Identifying the Time of Occurrence of a Hamstring Strain Injury during Treadmill Running: A Case Study. Clin. Biomech. 2005, 20, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, J.T.; Opar, D.A.; Weiss, L.J.; Heiderscheit, B.C. Hamstring Strain Injury Rehabilitation. J. Athl. Train. 2022, 57, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiteley, R.; Van Dyk, N.; Wangensteen, A.; Hansen, C. Clinical Implications from Daily Physiotherapy Examination of 131 Acute Hamstring Injuries and Their Association with Running Speed and Rehabilitation Progression. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 303–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, P.; Witvrouw, E.; Muxart, P.; Tol, J.L.; Whiteley, R. A Combination of Initial and Follow-up Physiotherapist Examination Predicts Physician-Determined Time to Return to Play after Hamstring Injury, with No Added Value of MRI. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016, 50, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opar, D.A.; Williams, M.D.; Shield, A.J. Hamstring Strain Injuries: Factors That Lead to Injury and Re-Injury. Sports Med. 2012, 42, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chumanov, E.S.; Heiderscheit, B.C.; Thelen, D.G. Hamstring Musculotendon Dynamics during Stance and Swing Phases of High-Speed Running. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvaux, F.; Croisier, J.-L.; Carling, C.; Orhant, E.; Kaux, J.-F. [Hamstring muscle injury in football players - Part I : epidemiology, risk factors, injury mechanisms and treatment]. Rev. Med. Liege 2023, 78, 160–164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mueller-Wohlfahrt, H.-W.; Haensel, L.; Mithoefer, K.; Ekstrand, J.; English, B.; McNally, S.; Orchard, J.; Van Dijk, C.N.; Kerkhoffs, G.M.; Schamasch, P.; et al. Terminology and Classification of Muscle Injuries in Sport: The Munich Consensus Statement. Br. J. Sports Med. 2013, 47, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, N.; James, S.L.J.; Lee, J.C.; Chakraverty, R. British Athletics Muscle Injury Classification: A New Grading System. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 1347–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, X.; Alentorn-Geli, E.; Tol, J.L.; Hamilton, B.; Garrett, W.E.; Pruna, R.; Til, L.; Gutierrez, J.A.; Alomar, X.; Balius, R.; et al. Muscle Injuries in Sports: A New Evidence-Informed and Expert Consensus-Based Classification with Clinical Application. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1241–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paton, B.M.; Court, N.; Giakoumis, M.; Head, P.; Kayani, B.; Kelly, S.; Kerkhoffs, G.M.M.J.; Moore, J.; Moriarty, P.; Murphy, S.; et al. London International Consensus and Delphi Study on Hamstring Injuries Part 1: Classification. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pihl, E.; Laszlo, S.; Rosenlund, A.-M.; Kristoffersen, M.H.; Schilcher, J.; Hedbeck, C.J.; Skorpil, M.; Micoli, C.; Eklund, M.; Sköldenberg, O.; et al. Operative versus Nonoperative Treatment of Proximal Hamstring Avulsions. NEJM Evid. 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, R.; Whiteley, R.; Van Der Made, A.D.; Van Dyk, N.; Almusa, E.; Geertsema, C.; Targett, S.; Farooq, A.; Bahr, R.; Tol, J.L.; et al. Early versus Delayed Lengthening Exercises for Acute Hamstring Injury in Male Athletes: A Randomised Controlled Clinical Trial. Br. J. Sports Med. 2022, 56, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clanton, T.O.; Coupe, K.J. Hamstring Strains in Athletes: Diagnosis and Treatment: J. Am. Acad. Orthop. Surg. 1998, 6, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankaew, A.; Chen, J.-C.; Chamnongkich, S.; Lin, C.-F. Therapeutic Exercises and Modalities in Athletes With Acute Hamstring Injuries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Health Multidiscip. Approach 2023, 15, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishøi, L.; Krommes, K.; Husted, R.S.; Juhl, C.B.; Thorborg, K. Diagnosis, Prevention and Treatment of Common Lower Extremity Muscle Injuries in Sport – Grading the Evidence: A Statement Paper Commissioned by the Danish Society of Sports Physical Therapy (DSSF). Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeulen, R.; Whiteley, R.; Van Der Made, A.D.; Van Dyk, N.; Almusa, E.; Geertsema, C.; Targett, S.; Farooq, A.; Bahr, R.; Tol, J.L.; et al. Early versus Delayed Lengthening Exercises for Acute Hamstring Injury in Male Athletes: A Randomised Controlled Clinical Trial. Br. J. Sports Med. 2022, 56, 792–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, A.N.; Tenforde, A.S.; Jelsing, E.J. Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy in the Management of Sports Medicine Injuries. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2021, 20, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.K.; Rho, M.E. Hamstring Injuries in the Athlete: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Return to Play. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2016, 15, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korakakis, V.; Whiteley, R.; Tzavara, A.; Malliaropoulos, N. The Effectiveness of Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy in Common Lower Limb Conditions: A Systematic Review Including Quantification of Patient-Rated Pain Reduction. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 387–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zissen, M.H.; Wallace, G.; Stevens, K.J.; Fredericson, M.; Beaulieu, C.F. High Hamstring Tendinopathy: MRI and Ultrasound Imaging and Therapeutic Efficacy of Percutaneous Corticosteroid Injection. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2010, 195, 993–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvers-Granelli, H.J.; Cohen, M.; Espregueira-Mendes, J.; Mandelbaum, B. Hamstring Muscle Injury in the Athlete: State of the Art. J. ISAKOS 2021, 6, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seow, D.; Shimozono, Y.; Tengku Yusof, T.N.B.; Yasui, Y.; Massey, A.; Kennedy, J.G. Platelet-Rich Plasma Injection for the Treatment of Hamstring Injuries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis With Best-Worst Case Analysis. Am. J. Sports Med. 2021, 49, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desouza, C.; Shetty, V. Efficacy of Platelet-Rich Plasma in Grade 2 Hamstring Muscle Injuries: Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol. 2025, 35, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poursalehian, M.; Lotfi, M.; Zafarmandi, S.; Arabzadeh Bahri, R.; Halabchi, F. Hamstring Injury Treatments and Management in Athletes: A Systematic Review of the Current Literature. JBJS Rev. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrado, B.; Mazzuoccolo, G.; Liguori, L.; Chirico, V.A.; Costanzo, M.; Bonini, I.; Bove, G.; Curci, L. Treatment of Lateral Epicondylitis with Collagen Injections: A Pilot Study. Muscle Ligaments Tendons J. 2019, 09, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godek, P.; Szczepanowska-Wolowiec, B.; Golicki, D. Collagen and PRP in Partial Thickness Rotator Cuff Injuries. Friends or Only Indifferent Neighbours? Randomized Controlled Trial; In Review, 2021; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Park, P.Y.S.; Cai, C.; Bawa, P.; Kumaravel, M. Platelet-Rich Plasma vs. Steroid Injections for Hamstring Injury—Is There Really a Choice? Skeletal Radiol. 2019, 48, 577–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieters, D.; Wezenbeek, E.; Schuermans, J.; Witvrouw, E. Return to Play After a Hamstring Strain Injury: It Is Time to Consider Natural Healing. Sports Med. 2021, 51, 2067–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giai Via, A.; Papa, G.; Oliva, F.; Maffulli, N. Tendinopathy. Curr. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Rep. 2016, 4, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koszela, K.; Woldańska-Okońska, M.; Słupiński, M.; Gasik, R. The Role of Injection Collagen Therapy in Greater Trochanter Pain Syndrome. A New Therapeutic Approach? Rheumatology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randelli, F.; Sartori, P.; Carlomagno, C.; Bedoni, M.; Menon, A.; Vezzoli, E.; Sommariva, M.; Gagliano, N. The Collagen-Based Medical Device MD-Tissue Acts as a Mechanical Scaffold Influencing Morpho-Functional Properties of Cultured Human Tenocytes. Cells 2020, 9, 2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randelli, F.; Menon, A.; Giai Via, A.; Mazzoleni, M.; Sciancalepore, F.; Brioschi, M.; Gagliano, N. Effect of a Collagen-Based Compound on Morpho-Functional Properties of Cultured Human Tenocytes. Cells 2018, 7, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randelli, F.; Fioruzzi, A.; Mazzoleni, M.G.; Radaelli, A.; Rahali, L.; Verga, L.; Menon, A. Efficacy of Ultrasound-Guided Injections of Type I Collagen-Based Medical Device for Greater Trochanteric Pain Syndrome: A Pilot Study. Life 2025, 15, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, B.; Bonini, I.; Chirico, V.A.; Filippini, E.; Liguori, L.; Magliulo, G.; Mazzuoccolo, G.; Rosano, N.; Gisonni, P. Ultrasound-Guided Collagen Injections in the Treatment of Supraspinatus Tendinopathy: A Case Series Pilot Study. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34, 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- De Pascalis, M.; Mulas, S.; Sgarbi, L. Combined Oxygen–Ozone and Porcine Injectable Collagen Therapies Boosting Efficacy in Low Back Pain and Disability. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godek, P.; Szczepanowska-Wolowiec, B.; Golicki, D. Collagen and PRP in Partial Thickness Rotator Cuff Injuries. Friends or Only Indifferent Neighbours? Randomized Controlled Trial; In Review, 2021; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Praet, S.F.E.; Purdam, C.R.; Welvaert, M.; Vlahovich, N.; Lovell, G.; Burke, L.M.; Gaida, J.E.; Manzanero, S.; Hughes, D.; Waddington, G. Oral Supplementation of Specific Collagen Peptides Combined with Calf-Strengthening Exercises Enhances Function and Reduces Pain in Achilles Tendinopathy Patients. Nutrients 2019, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jendricke, P.; Centner, C.; Zdzieblik, D.; Gollhofer, A.; König, D. Specific Collagen Peptides in Combination with Resistance Training Improve Body Composition and Regional Muscle Strength in Premenopausal Women: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarantino, D.; Mottola, R.; Palermi, S.; Sirico, F.; Corrado, B.; Gnasso, R. Intra-Articular Collagen Injections for Osteoarthritis: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2023, 20, 4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto Torrejón, L.; Martínez-Serrano, A.; Villalón, J.M.; Alcaraz, P.E. Economic Impact of Muscle Injury Rate and Hamstring Strain Injuries in Professional Football Clubs. Evidence from LaLiga. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0301498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacchio, A.; De Paulis, F.; Maffulli, N. Development and Validation of a New Visa Questionnaire (VISA-H) for Patients with Proximal Hamstring Tendinopathy. Br. J. Sports Med. 2014, 48, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, R.M. Proximal Hamstring Injuries: Management of Tendinopathy and Avulsion Injuries. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2019, 12, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauf, K.; Van Der Made, A.D.; Jaspers, R.; Tacken, R.; Maas, M.; Kerkhoffs, G. Successful Rapid Return to Performance Following Non-Operative Treatment of Proximal Hamstring Tendon Avulsion in Elite Athletes. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2025, 11, e002468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biz, C.; Nicoletti, P.; Baldin, G.; Bragazzi, N.L.; Crimì, A.; Ruggieri, P. Hamstring Strain Injury (HSI) Prevention in Professional and Semi-Professional Football Teams: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2021, 18, 8272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hickey, J.T.; Opar, D.A.; Weiss, L.J.; Heiderscheit, B.C. Hamstring Strain Injury Rehabilitation. J. Athl. Train. 2022, 57, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, R.L.; Cibulka, M.T.; Bolgla, L.A.; Koc, T.A.; Loudon, J.K.; Manske, R.C.; Weiss, L.; Christoforetti, J.J.; Heiderscheit, B.C. Hamstring Strain Injury in Athletes: Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health From the Academy of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy and the American Academy of Sports Physical Therapy of the American Physical Therapy Association. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2022, 52, CPG1–CPG44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihl, E.; Laszlo, S.; Rosenlund, A.-M.; Kristoffersen, M.H.; Schilcher, J.; Hedbeck, C.J.; Skorpil, M.; Micoli, C.; Eklund, M.; Sköldenberg, O.; et al. Operative versus Nonoperative Treatment of Proximal Hamstring Avulsions. NEJM Evid. 2024, 3, EVIDoa2400056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rich, A.; Cook, J.; Hahne, A.; Ford, J. Treatment of Proximal Hamstring Tendinopathy with Individualized Physiotherapy: A Clinical Commentary. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2025, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, A.L.F.; Cook, J.L.; Hahne, A.J.; Ford, J.J. A Pilot Randomised Trial Comparing Individualised Physiotherapy versus Shockwave Therapy for Proximal Hamstring Tendinopathy: A Protocol. J. Exp. Orthop. 2023, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afonso, J.; Olivares-Jabalera, J.; Fernandes, R.J.; Clemente, F.M.; Rocha-Rodrigues, S.; Claudino, J.G.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Valente, C.; Andrade, R.; Espregueira-Mendes, J. Effectiveness of Conservative Interventions After Acute Hamstrings Injuries in Athletes: A Living Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2023, 53, 615–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, B.; Bonini, I.; Alessio Chirico, V.; Rosano, N.; Gisonni, P. Use of Injectable Collagen in Partial-Thickness Tears of the Supraspinatus Tendon: A Case Report. Oxf. Med. Case Rep. 2020, 2020, omaa103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrado, B.; Mazzuoccolo, G.; Liguori, L.; Chirico, V.A.; Costanzo, M.; Bonini, I.; Bove, G.; Curci, L. Treatment of Lateral Epicondylitis with Collagen Injections: A Pilot Study. Muscle Ligaments Tendons J. 2019, 09, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, L.T.; DiSegna, S.; Newman, J.S.; Miller, S.L. Fluoroscopically Guided Peritendinous Corticosteroid Injection for Proximal Hamstring Tendinopathy: A Retrospective Review. Orthop. J. Sports Med. 2014, 2, 2325967114526135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scutt, N.; Rolf, C.G.; Scutt, A. Glucocorticoids Inhibit Tenocyte Proliferation and Tendon Progenitor Cell Recruitment. J. Orthop. Res. 2006, 24, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, B.; Tol, J.L.; Almusa, E.; Boukarroum, S.; Eirale, C.; Farooq, A.; Whiteley, R.; Chalabi, H. Platelet-Rich Plasma Does Not Enhance Return to Play in Hamstring Injuries: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Br. J. Sports Med. 2015, 49, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medina-Porqueres, I.; Rosado-Velazquez, D.; Moya-Torrecilla, F.; Orava, S.; Cacchio, A. Translation, Linguistic Validation, and Readability of the Spanish Version of VISA-H Scale in Elite Athletes. Arch. Bone Jt. Surg. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehto, M.; Sims, T.J.; Bailey, A.J. Skeletal Muscle Injury—Molecular Changes in the Collagen during Healing. Res. Exp. Med. (Berl.) 1985, 185, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, H.; Fujii, T.; Kuhn, K.; Chung, E.; Miller, E.J. Comparative Electron-Microscope Studies on Type-III and Type-I Collagens. Eur. J. Biochem. 1975, 51, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stauber, W.T.; Knack, K.K.; Miller, G.R.; Grimmett, J.G. Fibrosis and Intercellular Collagen Connections from Four Weeks of Muscle Strains. Muscle Nerve 1996, 19, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Järvinen, T.A.H.; Järvinen, T.L.N.; Kääriäinen, M.; Kalimo, H.; Järvinen, M. Muscle Injuries: Biology and Treatment. Am. J. Sports Med. 2005, 33, 745–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, T.M.; Shehadeh, S.E.; Leverson, G.; Michel, J.T.; Corr, D.T.; Aeschlimann, D. Analysis of Changes in mRNA Levels of Myoblast- and Fibroblast-derived Gene Products in Healing Skeletal Muscle Using Quantitative Reverse Transcription-polymerase Chain Reaction. J. Orthop. Res. 2001, 19, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | W value | P value | Parametric data |

|---|---|---|---|

| COL I | 0.9573 | 0.6787 | YES |

| REHAB | 0.9583 | 0.6952 | YES |

| Treatment | W value | P value | Parametric data |

|---|---|---|---|

| COL I | 0.9168 | 0.1974 | YES |

| REHAB | 0.9201 | 0.2268 | YES |

| Treatment | W value | P value | Parametric data |

|---|---|---|---|

| COL I (T0) | 0.9573 | 0.6787 | YES |

| COL I (T1) | 0.9468 | 0.5123 | YES |

| Treatment | W value | P value | Parametric data |

|---|---|---|---|

| REHAB (T0) | 0.9583 | 0.6952 | YES |

| REHAB (T1) | 0.9371 | 0.3820 | YES |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).