1. Introduction

Biliary tract malignancies are rare but lethal diseases. Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) represents the second most prevalent primary hepatic malignancy following hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), accounting for approximately 15% of all primary liver neoplasms and 3% of all gastrointestinal cancers [

1]. Its incidence and associated mortality have increased globally over the recent decade. Additionally, the other aggressive cancer that can affect the bile duct is pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), which mostly occurs in the head of the pancreas. Both PDAC and CCA are known for their poor prognosis [

2]. PDAC typically arises from ductal and acinar cells, often developing via precursor pancreatic lesions. In contrast, CCA originates from the epithelial lining of intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, frequently through biliary intraepithelial precursor lesions. Gallbladder cancers (GBC) are most commonly adenocarcinoma, but can also occur as squamous, adenosquamous, and small-cell subtypes, with no clear prognostic significance. Due to their anatomical site of origin, CCA is classified into intrahepatic (iCCA, 10–20%) and extrahepatic (eCCA) subtypes, with the latter further categorized into perihilar (pCCA, 60%) and distal (dCCA, 20–30%) variations [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Hilar cholangiocarcinoma (HC) is a malignant neoplasm of the proximal common bile duct or distal intrahepatic ducts involving biliary confluence. HC, specifically called Klatskin tumor, is considered an extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma as it originates from the extrahepatic bile ducts in the hepato-duodenal ligament and the gallbladder. Klatskin tumors account for 60-70% of all cholangiocarcinoma [

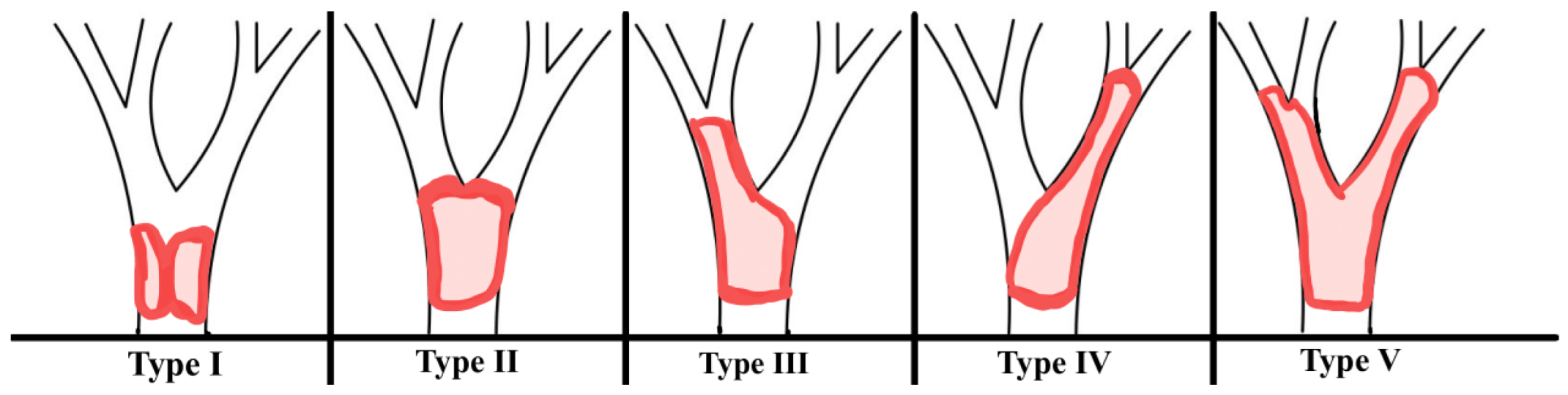

7]. This cancer develops gradually and implicitly, while symptoms appear mostly at the end stage of the disease. To evaluate the degree of ductal infiltration in perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, the 4-type Bismuth-Corlette classification system was developed (

Figure 1).

The classification is based on tumor location and the extent of bile duct infiltration, which has significant implications for surgical approaches in clinical practice. Symptoms of bilateral hilar tumors (including jaundice, pruritis, discolored stools, dark urine, and haemobilia) depend on the narrowing of the bile duct, the degree of infiltration into adjacent structures, and the location of the tumor. In the advanced stage of disease, nausea, vomiting, weight reduction, hepatomegaly, and ascites occur [

8]. Cholangiocarcinoma is considered one of the main causes of malignant biliary structures, which may lead to serious obstructions. Unfortunately, the histopathological diagnosis of the HC is often acquired while the carcinoma is at an advanced, non-resectable stage, which limits possible medical intervention that could result in an improvement of the patients’ condition. Less than one-half of HCs are resectable. The main treatment options encompass surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and photodynamic therapy. For PDAC localized in the head of the pancreas, surgical resections can be performed, such as a pancreaticoduodenectomy, commonly known as the Whipple procedure, or a pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (Traverso-Longmire procedure). However, only 25% of patients are classified for that surgical treatment. Even with radical treatment, chemotherapy is still obligatory in each case. In the management of GBC, treatment modalities beyond immunotherapy and radiotherapy encompass extensive hepatoduodenal ligament lymphadenectomy as well as resection of the gallbladder fossa, which typically involves partial hepatic resection. Recent studies show that jaundiced patients benefit from surgical treatment in this case [

9]. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) and percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) are essential techniques for assessing the extent of the tumor in the bile ducts. A method recommended for biliary drainage is the placement of an endoscopic or percutaneous stent with a self-expanding metallic stent (SEMS). Recent studies have shown that SEMS tend to have more suitable outcomes than plastic stents, and SEMS provide a longer patency and improved patient survival after the procedure [

10]. Thus, the insertion of plastic or metal SEMS biliary stents during ERCP and combining it with RFA of the tumor mass is one of the minimally invasive methods of treatment for biliary obstruction and palliative treatment of biliary hilar tumors [

11]

RFA is a minimally invasive technique used in the palliative treatment of bile duct cancer. This procedure is typically performed during routine endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERCP). RFA works by generating thermocoagulation cell necrosis through ionic excitation using electromagnetic wave frequencies ranging from 104 to 3×1012 Hz. Thermal ablation is achieved using an electrode that is inserted into the tumor site, which delivers high-frequency radio waves. This energy heats the diseased tissue, resulting in necrosis and the gradual separation of the tissue from the surrounding healthy area. The depth of necrosis typically extends radially for about 3 to 8 mm and is influenced by the amount of energy applied during treatment. Two types of probes can be used to establish an electrical circuit: a monopolar probe or two bipolar probes. The ions within the cancerous tissue follow the alternating current path, creating frictional heat that leads to protein denaturation and cell dehydration, resulting in cell death. This effect is most potent near the probe, limiting the coagulation of tissues farther away, which are primarily heated by thermal conduction, insufficient to cause necrosis. To achieve effective results, the required intermittent heat must reach a temperature between 60–80°C, maintained for 1–2 minutes with an output of 7–10 W. Currently, two bipolar endoluminal RFA catheters are available on the market: the Habib™ EndoHPB and the ELRA™ Electrode. This study aims to investigate the impact of using endoluminal RFA via the endoscopic approach for hilar tumors, combined with the placement of bilateral self-expanding metal stents (SEMS), Amsterdam stents, or double pig-tail stents (PGT), on the clinical prognosis of patients, as well as the safety and occurrence of complications related to the procedure.

2. Materials and Methods

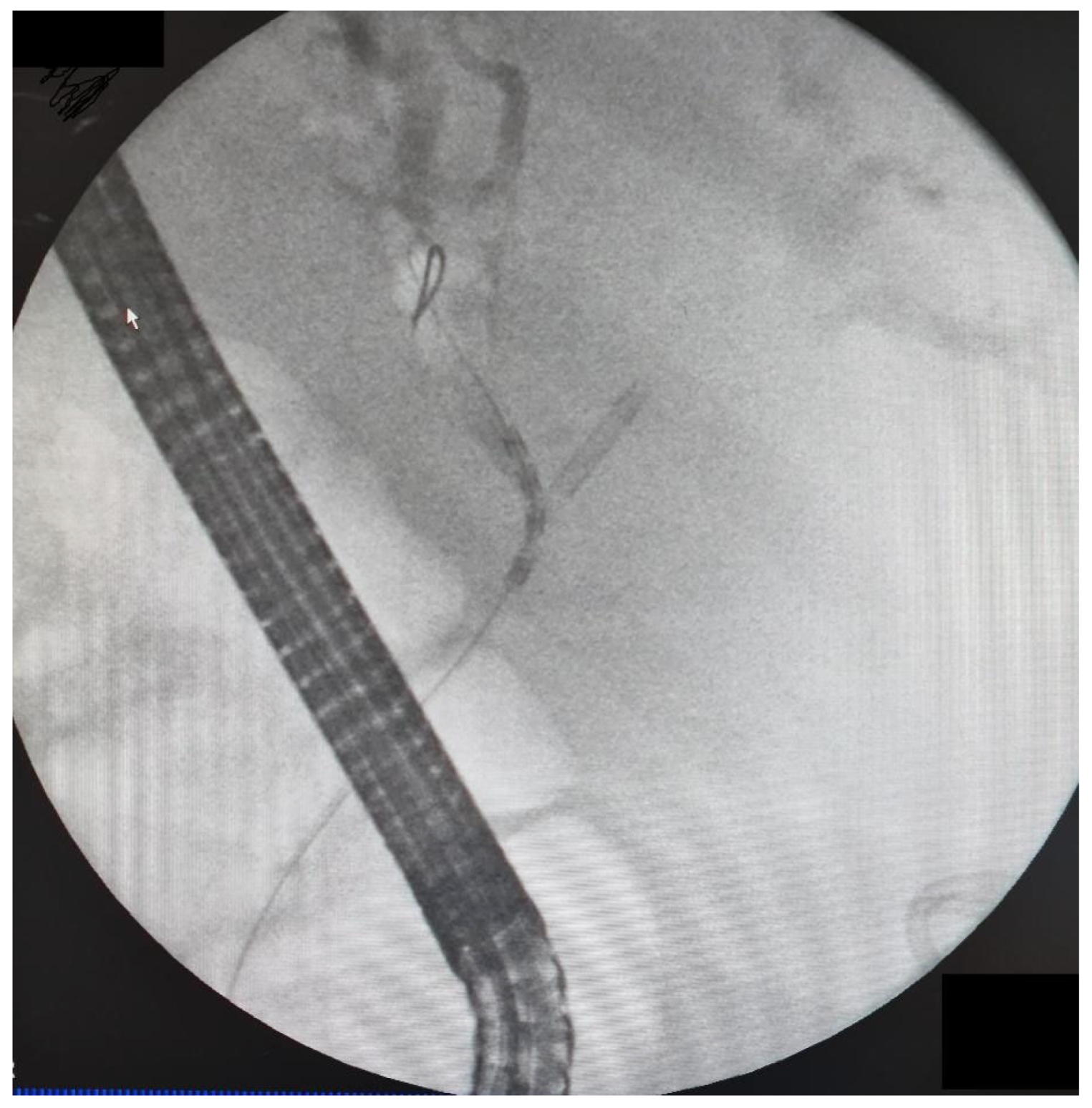

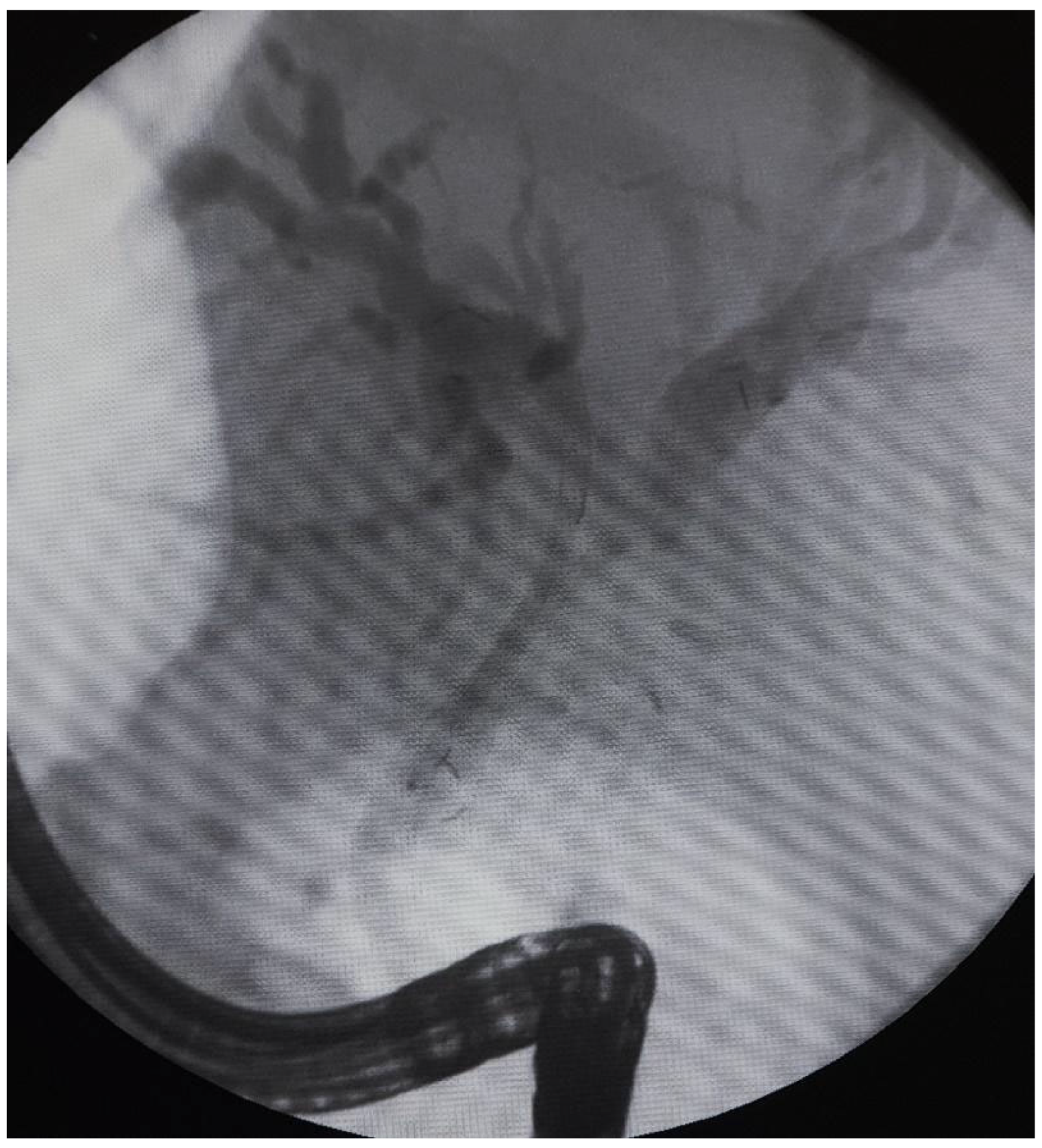

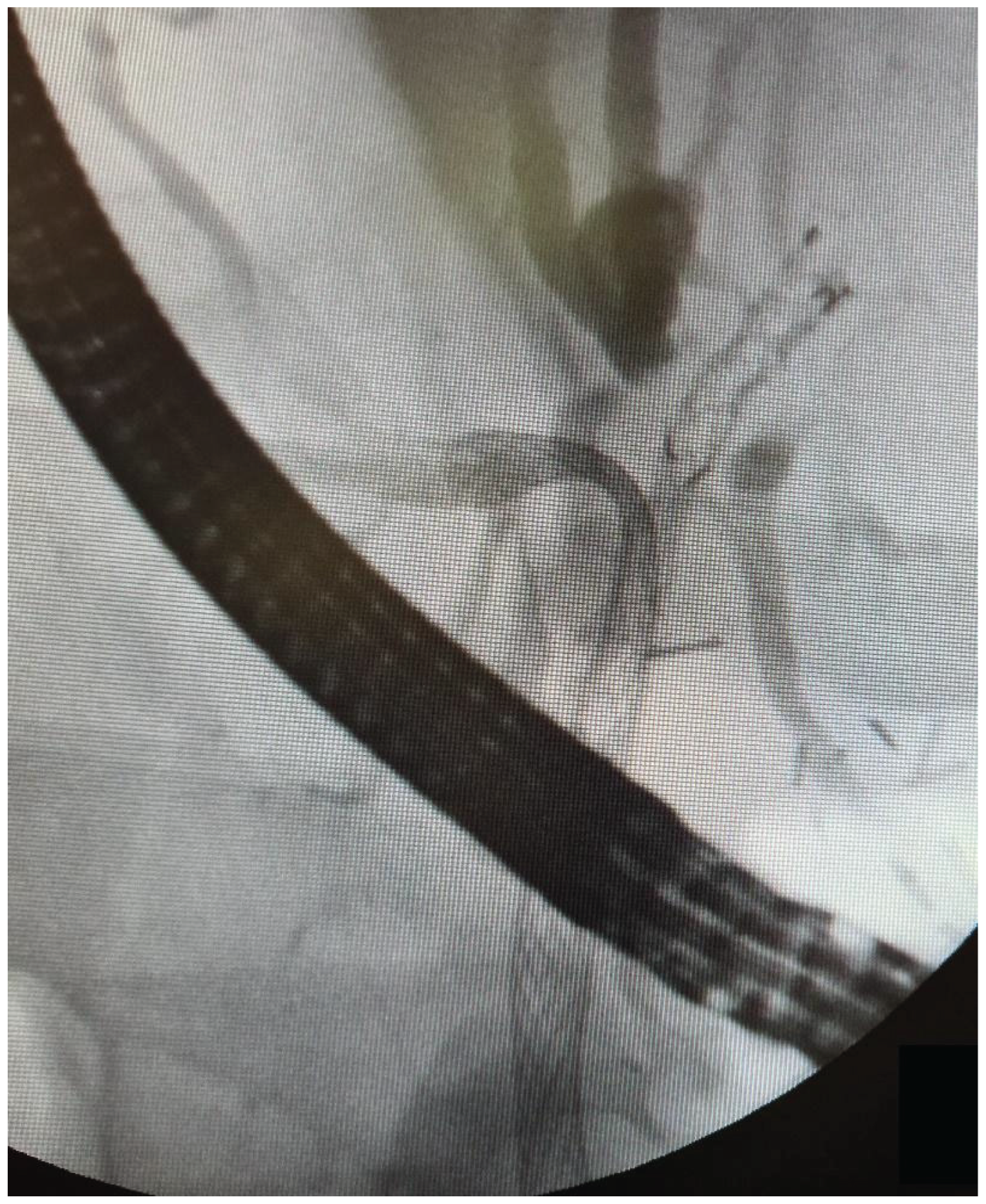

The data from 24 consecutive patients with bile duct stenosis due to non-resectable HC who underwent RFA with bile duct stenting in our department between 05.2020–05.2024 were collected retrospectively from electronic medical records and analyzed. Patients with malignant biliary stenosis had diagnoses of unresectable HC, PDAC in the head of the pancreas, and adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder. Inclusion criteria for RFA treatment included patients with recurrent mechanical jaundice due to cancer progression despite a previous biliary prosthesis. High-power radiofrequency ablation of the narrowed biliary segments, followed by reimplantation of SEMS, Amsterdam stents, or double pigtail (DPT) into their lumen, was performed in 24 patients (19 women and 5 men). The procedure was performed under intravenous sedation using a PENTAX-ED-34 and 10t2 duodenoscope. RFA was carried out with a power setting of 7–14 watts and a temperature of 75–80°C. The following stents were used for the procedure: uncovered SEMS (10x80 mm, 10x60 mm, 10x100 mm), Large Cell D-type stents (LCD) (10x60 mm), fully-covered SEMS (8x80 mm), Amsterdam-type plastic stents (12cm 10 Fr, 9cm 10 Fr, 12 cm 8.5 Fr, 12 cm 7 Fr), and self-expandable BIL-0-10-60-RP stents. Figures 2, 3, and 4 present the RFA catheter and stents’ configurations (

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4).

A retrospective study compared serum bilirubin concentration before treatment, 30 days, and 6 months after the procedure. Stent patency and complications were investigated and analyzed. The main measure of the effectiveness of the procedure was the decrease in bilirubin concentration, allowing the continuation of chemotherapy. The statistical analysis was performed to identify factors influencing the success rate, defined as bilirubin concentration, allowing the continuation of oncological treatment. The following variables were examined:

Categorical variables: gender and type of the prosthesis;

Numerical variables: age, bilirubin level before the procedure, number of stents being used, size of the stent, number of RFA series, and RFA power.

Statistical Tests: For numerical variables, the Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the distributions of the success rate between the groups, as the data did not meet the assumptions for parametric testing. For categorical variables, Fisher’s Exact Test was applied for 2x2 contingency tables, while the Chi-Square Test was used for larger tables to assess associations with success.

3. Results

24 patients (19 females and 5 males) were included in the study. The patients' ages varied from 50 to 84, with the median and mean of 69 and 67.1 years, respectively. All the patients underwent an implantation of a biliary prosthesis in the past due to cholestasis caused by malignancy. Among the investigated cases, 8 were diagnosed with metastatic adenocarcinoma, 6 with cholangiocarcinoma (CCC), 5 with adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder, 4 with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and 1 with neuroendocrine tumour (NET).

Table 1 describes detailed patient characteristics.

The number of RFA series, the energy applied, and the number of prostheses being used varied among patients, reflecting individualized treatment protocols, as summarized in

Table 2.

6 of 24 patients (25%) did not complete the 6-month follow-up. In this group, during the 30-day follow-up, only 1 patient did not achieve a bilirubin concentration allowing the continuation of chemotherapy. The rest of the patients died due to the advanced stage of the malignancy.

In the group of patients who completed the 6-month follow-up, 16/18 (88.9%) maintained the patency of biliary stents and could continue the oncological treatment. The remaining two patients required endoscopic interventions due to biliary stent obstruction, which were not successful. Boxplot analyses were conducted to examine the distribution of numerical variables (age, bilirubin level before the procedure, number of prostheses, length of prosthesis, and number of RFA series) between patients who achieved success and those who did not. While there was a slight difference in median age between the success and failure groups, statistical analysis revealed no significant difference (p=0.148, Mann-Whitney U test).

Patients' bilirubin levels before the procedure showed variability within both groups, but no significant association with success was observed (p=0.662, Mann-Whitney U test).

Most patients required one prosthesis, and the distribution of prosthesis counts did not differ significantly between the groups (p=0.204, Mann-Whitney U test). The median length of prostheses was similar between groups, with no statistically significant association with success (p=0.961, Mann-Whitney U test).

Patients underwent between one and six RFA sessions, with no statistically significant difference in the number of sessions between the success and failure groups (p=0.637, Mann-Whitney U test).

The findings suggest that none of the examined numerical variables showed a significant impact on the likelihood of achieving success. Bar chart analyses and contingency tables were used to explore associations between categorical variables (gender and type of prosthesis) and success. The proportion of male and female patients achieving success was comparable, with no statistically significant difference (p=0.329, Fisher’s Exact Test). The use of different prosthesis types did not significantly impact the likelihood of success (p=0.401, Chi-Square Test).

The results indicate that neither the numerical variables (e.g., age, bilirubin level, number of prostheses, length of prosthesis, number of RFA series) nor the categorical variables (e.g., gender, type of prosthesis) were significantly associated with treatment success (

Table 3). The group characteristics and parameters, and efficacy of the applied radiofrequency ablation are in

Table 4 (

Table 4).

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the effectiveness and safety of RFA with biliary stenting in patients with non-resectable malignancies (HC, PDAC in the head of the pancreas, and adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder) causing biliary obstruction in the initial group of 24 patients. Our findings reveal that this minimally invasive approach can help restore and maintain biliary patency in non-resectable malignancies that cause bile obstruction. In approximately 90% of patients who survived the 6-month follow-up period, bilirubin levels decreased and stabilized sufficiently to allow chemotherapy to continue. This highlights the usefulness of RFA as an adjunct to palliative treatment that prolongs stent patency and increases an individual's ability to undergo systemic oncological therapy. The observed high stent patency with RFA is consistent with the recent studies, such as meta-analyses, that favour the use of RFA with biliary stenting compared to sole biliary stenting [

12,

13].

Our results are consistent with the observations of other authors, who recognise the benefits of using RFA in conjunction with biliary stenting. Recent RCTs, Gao et al. and Yang et al., support the use of RFA with biliary stenting, highlighting its association with longer survival, stent patency, and improvements in functioning status compared to sole biliary stenting in unresectable extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma or ampullary cancer unsuitable for surgery [

14,

15]. Another RCT, Kang et al., concerning advanced malignant hilar biliary obstruction, also confirms the findings [

16].

However, Jarosova et al. conducted a randomized controlled trial concerning the use of RFA with stenting compared to stenting alone in patients with CCA and PDAC. Regarding stent patency at 12 months and prolonging survival, RFA with biliary stenting was found to be non-superior to biliary stenting alone [

17]. The most recent meta-analysis, including the mentioned above RCTs, revealed that in patients with unresectable cholangiocarcinoma, the combination of RFA and stenting was associated with improved overall survival and stent patency; however, the statistical power and high heterogeneity of the study group do not allow for clear conclusions to be drawn [

18]. The authors point to the need for further research, hence our attempt to describe our clinical experience with RFA and stenting.

Biliary drainage is a key element that improves overall survival for malignant biliary obstruction [

19]. Prognosis in nonresectable malignant biliary obstruction is generally poor, but drainage, along with palliative chemotherapy, can increase overall survival, improve quality of life, and relieve pain and pruritus [

20]. Based on the results of available studies, the median overall survival of patients treated with drainage alone, without RFA, remains within a few months (6-9 months). With RFA, this value increases to about a year (10-12 months). Primary bile duct tumours, such as CCA or ampullary carcinoma, are particularly valuable in terms of median survival, while secondary tumours (PDAC, gallbladder carcinoma, HCC, metastases) derive questionable benefit from the use of RFA. [

21]. Complications can also negatively affect survival rates. In retrospective and cohort studies, e.g., among patients with non-operable malignant distal bile duct stricture after stenting, the 6-month survival rate was only 24% (median ≈ 81 days) [

22]. In Yang's study, patients with CCA were randomly assigned to receive RFA with stenting in combination with a novel 5-fluorouracil compound, S-1, or RFA with biliary stenting alone. The results demonstrated that additional chemotherapy significantly improved overall survival (16 months and 11 months, respectively), and stent patency time was significantly longer (6.6 months and 5.6 months, respectively), and quality of life assessed by Karnofsky index was also improved [

23].

The study population consisted mostly of females, with a mean age of 67.1 years. The heterogeneity of our study group remains high due to many types of non-resectable cancers and their location within the biliary tract, stent types (plastic, covered, self-expandable), and their number (1 or 2), dimensions of each stent. Remarkably, the statistical analysis did not allow for identification of any factors between treatment success and the variables assessed, including age, gender, bilirubin levels, RFA technical parameters and type/number of prostheses, which suggests the RFA effectiveness is consistent across wide range of factors that could potentially play a crucial role in treatment success, both patient-depended and technical ones. However, the main limitation is small sample size, which does not allow for drawing objective conclusions. What is important, our study did not find any significant difference in the type of prosthesis used that could affect the clinical outcomes. Moole et al. compared the use of self-expandable metal stents with plastic stents in malignant distal biliary strictures and found that SEMS seemed to be superior in comparison to plastic stents in providing patency for a longer time. SEMS was also found to have lower odds of complications such as occlusion, the need for re-intervention, and cholangitis [

24]. In our study, the Amsterdam plastic stent performed comparably well as SEMS. However, proper patient selection for each stent and disease progression was crucial.

Also, it is important to recognize that 25% of patients did not survive 6 months of follow-up due to malignancy progression, which reveals the aggressive nature of the disease and the limited time window to undertake treatment. Nevertheless, the great majority of patients completed the follow-up period and maintained biliary tract patency, which confirms that RFA combined with biliary stenting is a highly effective, modern, safe, and minimally invasive treatment method. Unfortunately, 2 patients struggled with maintaining patency, requiring multiple interventions, which were not successful. This suggests that when the stent occlusion occurs, the outcomes of treatment may be less favourable, underlining the urge for early detection and the initial effective management.

This study has a few limitations. First, the sample size comprises 24 patients; however, the actual follow-up at 6 months was assessed in only 18 patients. That significantly limits the power of statistical analysis to detect significant associations between variables and treatment outcomes. Although single-institutional reports like ours are encouraging regarding the effectiveness of RFA and biliary stenting, this calls for larger, multi-institutional, high-quality randomized controlled studies of RFA with stenting and sole stenting, given the rarity of biliary tract malignancies. Indistinct data in the literature support the need for further research on RFA and biliary stenting. Second, the retrospective design of the study introduces the risk of confounding in patient selection and prosthetic selection. Third, our study assessed only the bilirubin concentration as a success indicator. We did not assess patient-reported outcomes, such as quality of life, pain control, and relief of pruritus. This should be the subject of further research on the impact on quality of life after RFA with biliary stenting.

5. Conclusions

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) with biliary stenting is a highly effective, safe method for maintaining biliary patency in cases of unresectable biliary malignant obstruction. This minimally invasive approach helped to maintain biliary patency and allowed for the continuation of chemotherapy in the majority of patients who completed follow-up. While we did not find any specific factors associated with treatment success or failure, our findings support the use of RFA with biliary stenting as a safe, feasible option in non-resectable malignancies of the biliary tract.

Author Contributions

TK: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, software, validation, writing - original draft, writing - review and editing. WC: Data curation, formal analysis, methodology, software, validation, writing - original draft, writing - review and editing. WA: Data curation, formal analysis, methodology, software, validation, visualization, writing - original draft, writing - review and editing. KW: Data curation, formal analysis, methodology, software, validation, writing - original draft, writing - review and editing. AG: Data curation, formal analysis, methodology, software, validation, writing - original draft, writing - review and editing. AD: Data curation, formal analysis, supervision, validation, writing - review and editing. JS: Data curation, formal analysis, supervision, validation, writing - review and editing. PH: Data curation, formal analysis, supervision, validation, writing - review and editing.

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was a retrospective analysis of anonymized clinical data and did not involve any direct patient intervention or identifiable personal information. According to institutional and national regulations, it does not meet the criteria of a medical experiment and, therefore, was exempt from ethics committee review and informed consent requirements. The study was conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant guidelines for research integrity.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to retrospective nature of the study. All data used in this study were anonymized prior to analysis. The research involved only retrospective evaluation of anonymized clinical information, with no patient contact or use of identifiable personal data. According to institutional and national regulations, the study did not meet the criteria for human subjects research requiring informed consent. Therefore, informed consent was not required.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.Acknowledgments: AI-based programs, such as Grammarly and ChatGPT, were implemented only to improve the readability of the manuscript and grammar. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sarcognato S, Sacchi D, Fassan M, Fabris L, Cadamuro M, Zanus G, Cataldo I, Capelli P, Baciorri F, Cacciatore M, Guido M. Cholangiocarcinoma. Pathologica. 2021;113(3):158-169. [CrossRef]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022;72:7–33. [CrossRef]

- Nagtegaal ID, Odze RD, Klimstra D, Paradis V, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Washington KM, Carneiro F, Cree IA. WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board The 2019 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Histopathology. 2020;76:182–188. [CrossRef]

- Banales JM, Marin JJG, Lamarca A, Rodrigues PM, Khan SA, Roberts LR, Cardinale V, Carpino G, Andersen JB, Braconi C, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: The next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;17:557–588. [CrossRef]

- Rizvi S, Khan SA, Hallemeier CL, Kelley RK, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma—Evolving concepts and therapeutic strategies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2018;15:95–111. [CrossRef]

- Blechacz B, Komuta M, Roskams T, Gores GJ. Clinical diagnosis and staging of cholangiocarcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011;8:512–522. [CrossRef]

- Lee IC, Stüben BO, Fard-Aghaie M, Giannou A, Ghadban T, Heumann A, Li J. Individualized surgical approach based on Bismuth-Corlette classification for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Surg Oncol. 2024;3:100057. [CrossRef]

- Laimer G, Jaschke N, Gottardis M, Schullian P, Putzer D, Eberle G, Bale R. Stereotactic radiofrequency ablation of an unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC): transforming an aggressive disease into a chronic condition. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2020;43(5):791–796. [CrossRef]

- Weismüller TJ. Role of Intraductal RFA: A Novel Tool in the Palliative Care of Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma. Visc Med. 2021;37(1):39-47. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Sánchez MV, Napoléon B. Review of endoscopic radiofrequency in biliopancreatic tumours with emphasis on clinical benefits, controversies, and safety. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(37):8257–70.

- Jansen C, Vilmann P, Brink L, Olafsson L, Kovacevic B. Endoluminal radiofrequency ablation of malignant biliary obstruction. Ugeskr Laeger. 2023;185(12): V11220678.

- Khizar H, Hu Y, Wu Y, Ali K, Iqbal J, Zulqarnain M, Yang J. Efficacy and Safety of Radiofrequency Ablation Plus Stent Versus Stent-alone Treatments for Malignant Biliary Strictures: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2023;57(4):335-345. [CrossRef]

- Tarar ZI, Farooq U, Gandhi M, Ghous G, Saleem S, Kamal F, Imam Z, Jamil L. Effect of radiofrequency ablation in addition to biliary stent on overall survival and stent patency in malignant biliary obstruction: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;35(6):646-653. [CrossRef]

- Gao DJ, Yang JF, Ma SR, Wu J, Wang TT, Jin HB, Xia MX, Zhang YC, Shen HZ, Ye X, Zhang XF, Hu B. Endoscopic radiofrequency ablation plus plastic stent placement versus stent placement alone for unresectable extrahepatic biliary cancer: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94(1):91-100.e2. [CrossRef]

- Yang J, Wang J, Zhou H, Zhou Y, Wang Y, Jin H, Lou Q, Zhang X. Efficacy and safety of endoscopic radiofrequency ablation for unresectable extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2018;50(8):751-760. [CrossRef]

- Kang H, Han SY, Cho JH, Kim EJ, Kim DU, Yang JK, Jeon S, Park G, Lee TH. Efficacy and safety of temperature-controlled intraductal radiofrequency ablation in advanced malignant hilar biliary obstruction: A pilot multicenter randomized comparative trial. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2022;29(4):469-478. [CrossRef]

- Jarosova J, Zarivnijova L, Cibulkova I, Mares J, Macinga P, Hujova A, Falt P, Urban O, Hajer J, Spicak J, Hucl T. Endoluminal radiofrequency ablation in patients with malignant biliary obstruction: a randomised trial. Gut. 2023;72(12):2286-2293. [CrossRef]

- Balducci D, Montori M, Martini F, Valvano M, De Blasio F, Argenziano ME, Tarantino G, Benedetti A, Bendia E, Marzioni M, Maroni L. The Impact of Radiofrequency Ablation on Survival Outcomes and Stent Patency in Patients with Unresectable Cholangiocarcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16(7):1372. [CrossRef]

- Jagtap VK, Kumar S, Harris C, Lynser D, Raphael V. Improved Survival With Chemotherapy in Patients With Malignant Biliary Tract Obstruction After Percutaneous Transhepatic Biliary Drainage (PTBD). Cureus. 2024;16(6):e63218. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Z, Li J, Liu H, Wu D, Xu Y, Xia Y, Lu J, Guo C, Zhou Y. Quality of life and survival of patients with malignant bile duct obstruction following different ERCP based treatments. Int J Clin Exp Med 2016;9(5):8821-8832.

- Xia M, Qin W, Hu B. Endobiliary radiofrequency ablation for unresectable malignant biliary strictures: Survival benefit perspective. Dig Endosc. 2023;35(5):584-591. [CrossRef]

- Kusumaningtyas L, Makmun D, Syam AF, Setiati S. Six-month Survival of Patients with Malignant Distal Biliary Stricture Following Endoscopic Biliary Stent Procedure and Its Associated Factors. Acta Med Indones. 2020;52(1):31-38.

- Yang J, Wang J, Zhou H, Wang Y, Huang H, Jin H, Lou Q, Shah RJ, Zhang X. Endoscopic radiofrequency ablation plus a novel oral 5-fluorouracil compound versus radiofrequency ablation alone for unresectable extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92(6):1204-1212.e1. [CrossRef]

- Moole H, Jaeger A, Cashman M, Volmar FH, Dhillon S, Bechtold ML, Puli SR. Are self-expandable metal stents superior to plastic stents in palliating malignant distal biliary strictures? A meta-analysis and systematic review. Med J Armed Forces India. 2017;73(1):42-48. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).