Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

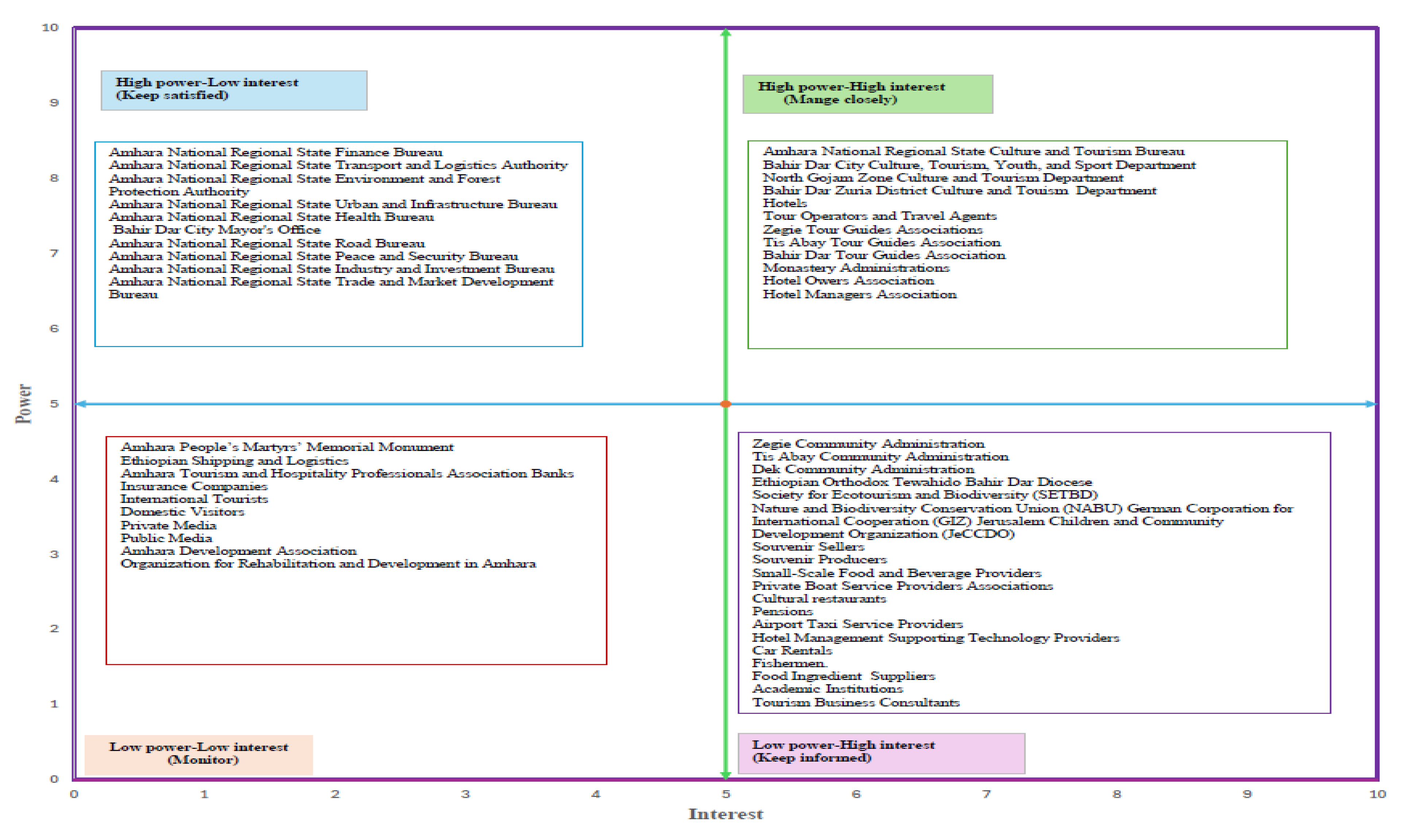

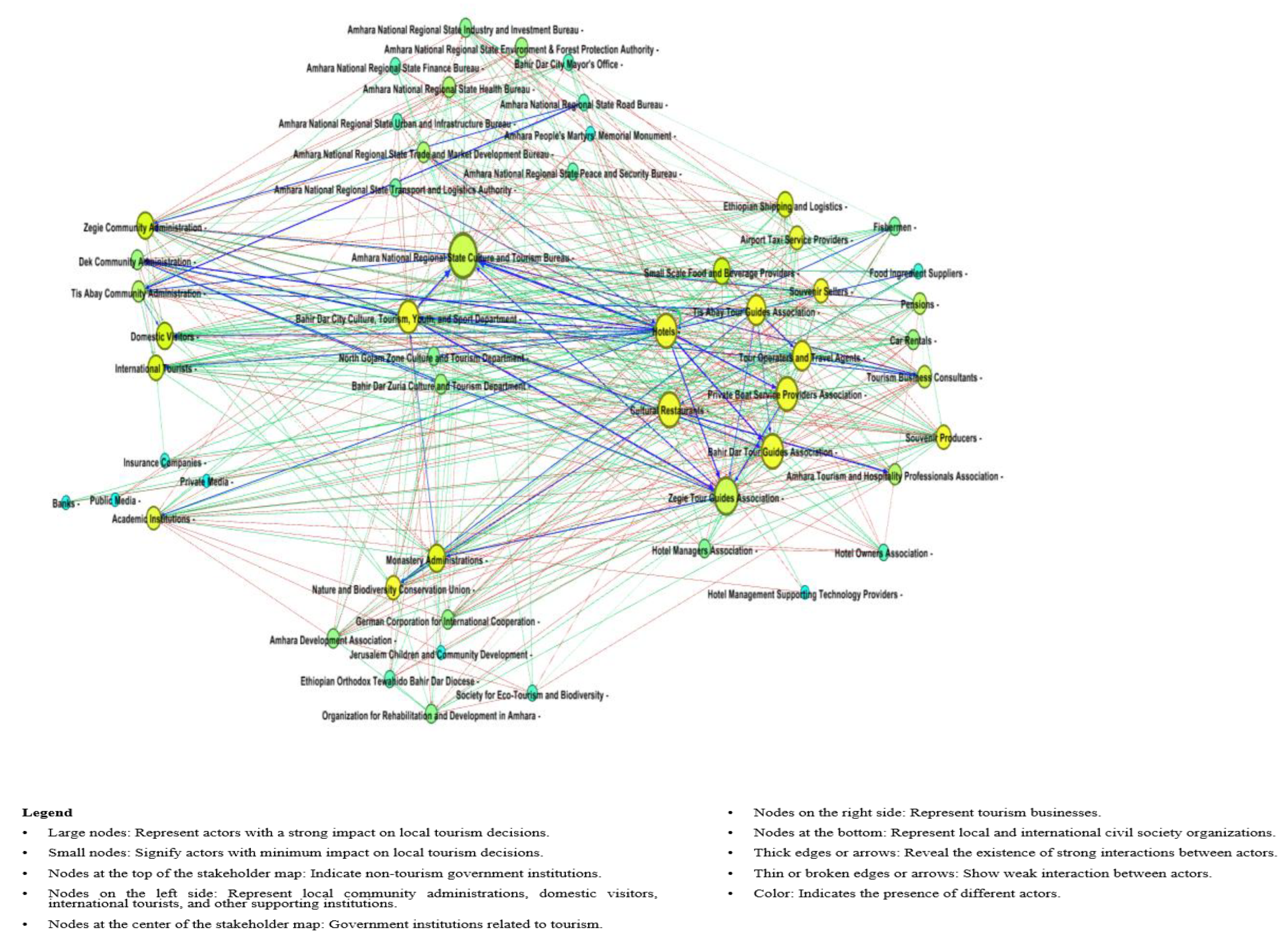

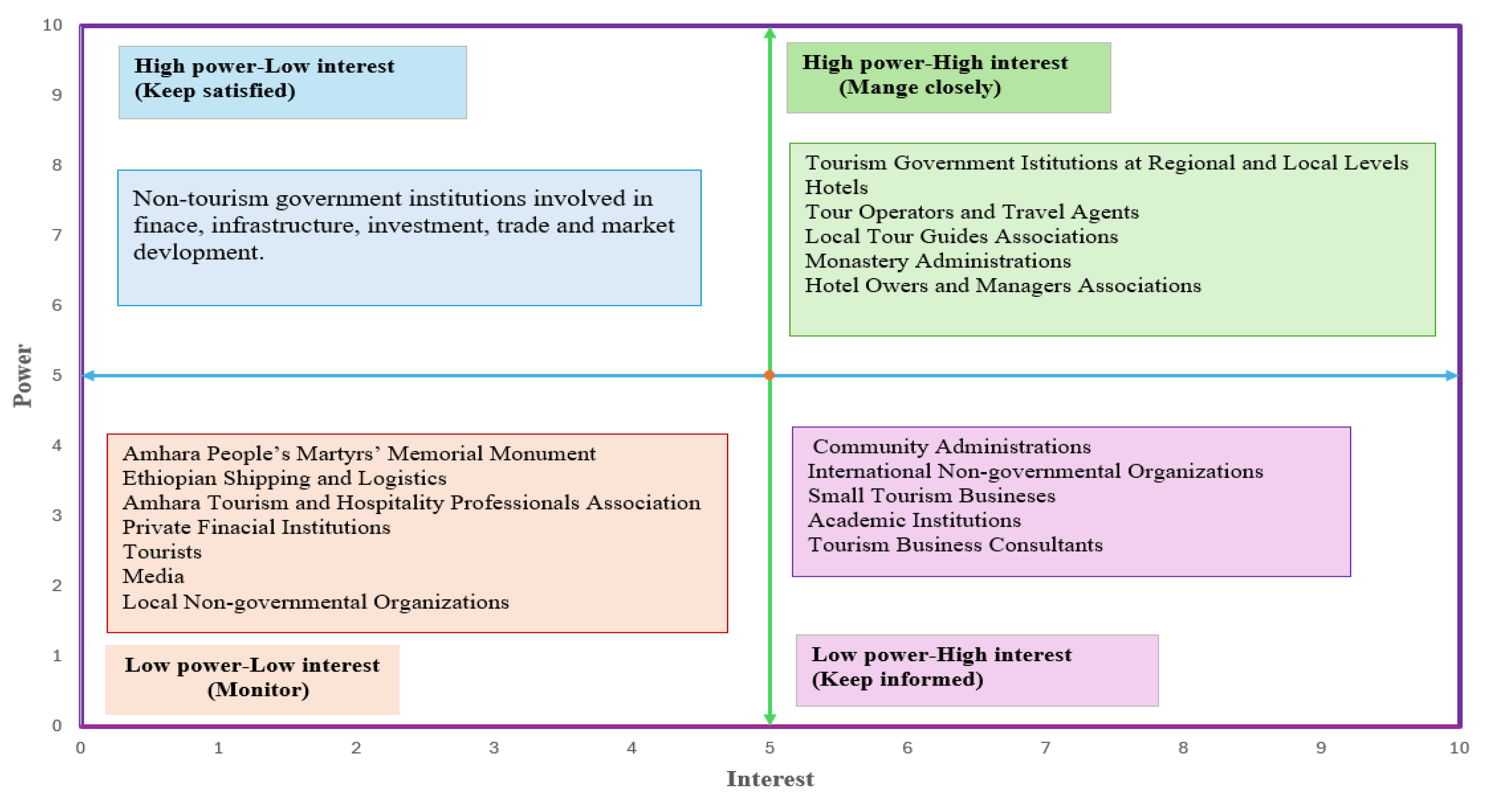

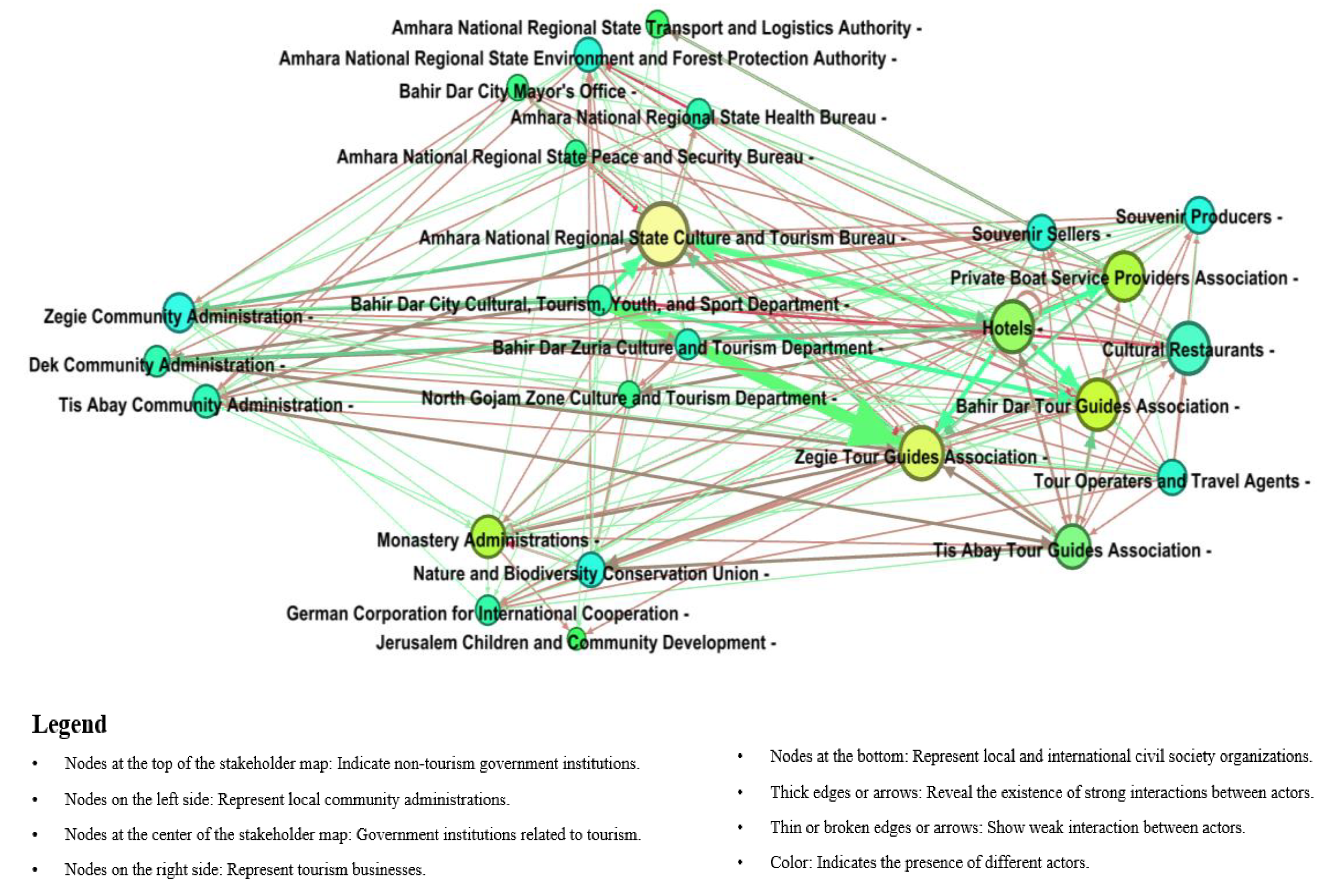

Tourism, being an inherently fragmented and multisectoral phenomenon, requires the involvement of a diverse range of stakeholders. The main aim of the present study is to map local tourism stakeholders and analyze governance networks. The researchers recruited research participants from key tourism stakeholders through purposive sampling techniques. Closed-ended questionnaires, semi-structured interviews, and focus group discussions were used for collecting data. This study applied the power-interest grid for mapping local tourism stakeholders. In addition, by applying the concept of resource dependency theory, the Social Network Analysis technique was employed for mapping the local tourism governance networks. The findings disclosed that the local tourism stakeholder map primarily comprises government institutions, tourism businesses, local communities, and civil society organizations. Even though tourism government institutions and large tourism businesses established strong linkages, the network density was found to be moderate. Implementing effective stakeholder mapping techniques and strengthening local tourism governance networks is crucial to augment sustainable tourism. This study makes a substantive contribution to academia by providing insights into the methods and techniques essential for mapping tourism stakeholders and governance networks. Moreover, the study has practical implications for destination management organizations, policymakers, and destination administrators.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Stakeholder Mapping in Tourism: Insights from Empirical Literature

2.2. Resource Dependence Theory

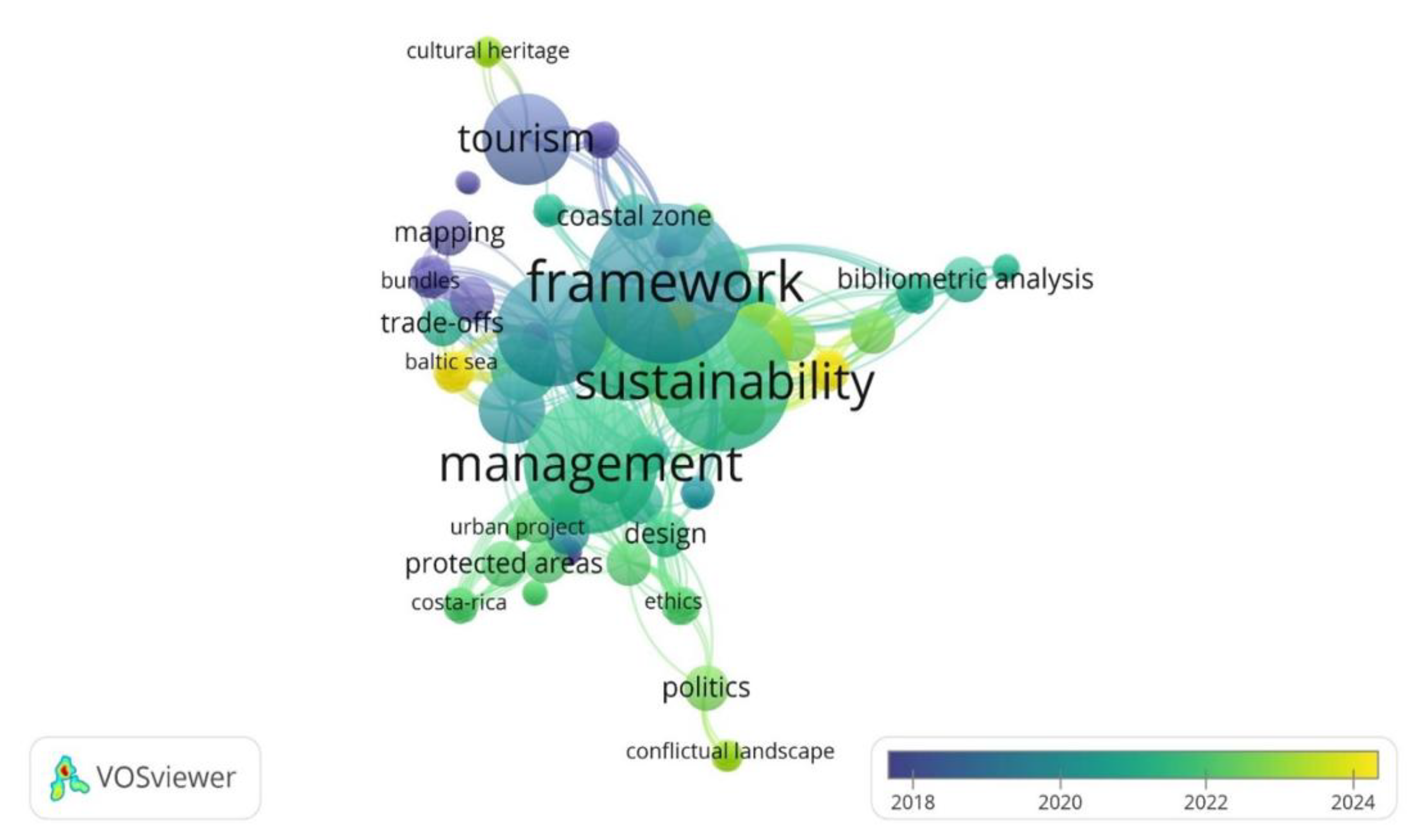

2.3. Bibliometric Analysis

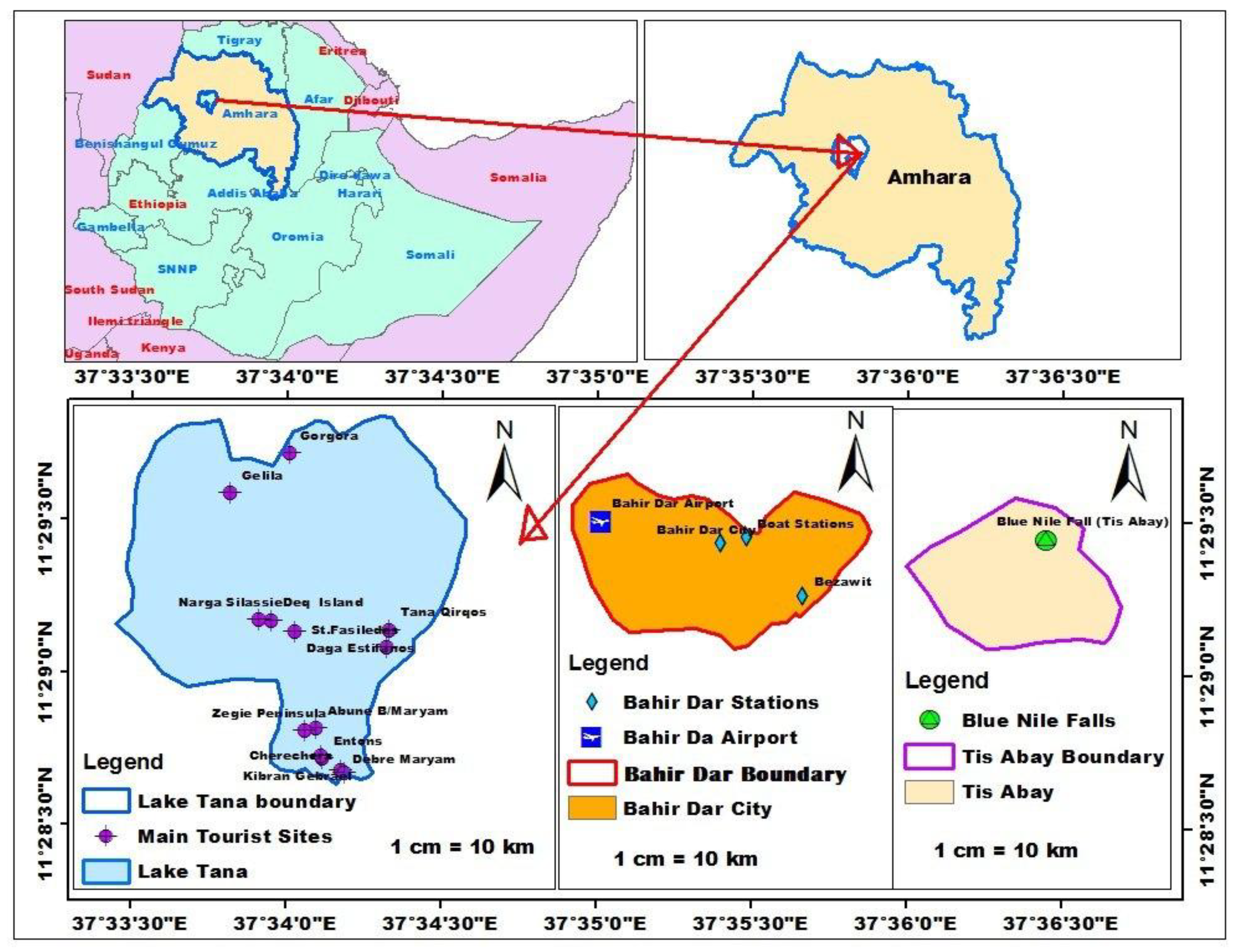

3. The Study Area

4. Materials and Methods

Data Analysis

5. Results

5.1. Local Tourism Stakeholder Mapping

5.2. Local Tourism Governance Network Map

“…..As I have observed, in the Lake Tana region, despite their importance in improving tourism infrastructure, non-tourism government institutions working on finance, transport, investment, trade, and market development experienced sporadic interaction with tourism government institutions and tourism businesses. So, this scenario retards, sustainable tourism development…….“.

“As far as I know, no tourist activity is allowed within a peninsula or island monastery without the permission of the monastery administration. Therefore, tour operators and local tour guides work in harmony with monastery administrators, which strengthens local tourism governance networks”.

“The involvement of monastery administrators, local communities, civil society organizations, tourism businesses, and domestic and international visitors in the local tourism governance network map is crucial in improving tourism decisions. However, in the Lake Tana region, local and international non-governmental organizations established poor linkages with tourism government institutions”.

“…….Weak interactions are also exhibited between tourism government institutions and small tourism businesses. Therefore, as far as I am concerned, in light of the existing network between tourism stakeholders in the Lake Tana region, it is essential to ensure that each stakeholder's interest is considered in the local tourism decision-making process…“.

“…..one information I would like to add is concerning the importance of tourism stakeholders for each other's existence in the sector. To the best of my expertise, it is always feasible to ensure strong interaction between actors involved in tourism service provisions. As such, actors with strong networks need to encourage those actors with weak networks to participate in local tourism decisions. In this regard, actors feel more responsible in the local tourism activities…...“.

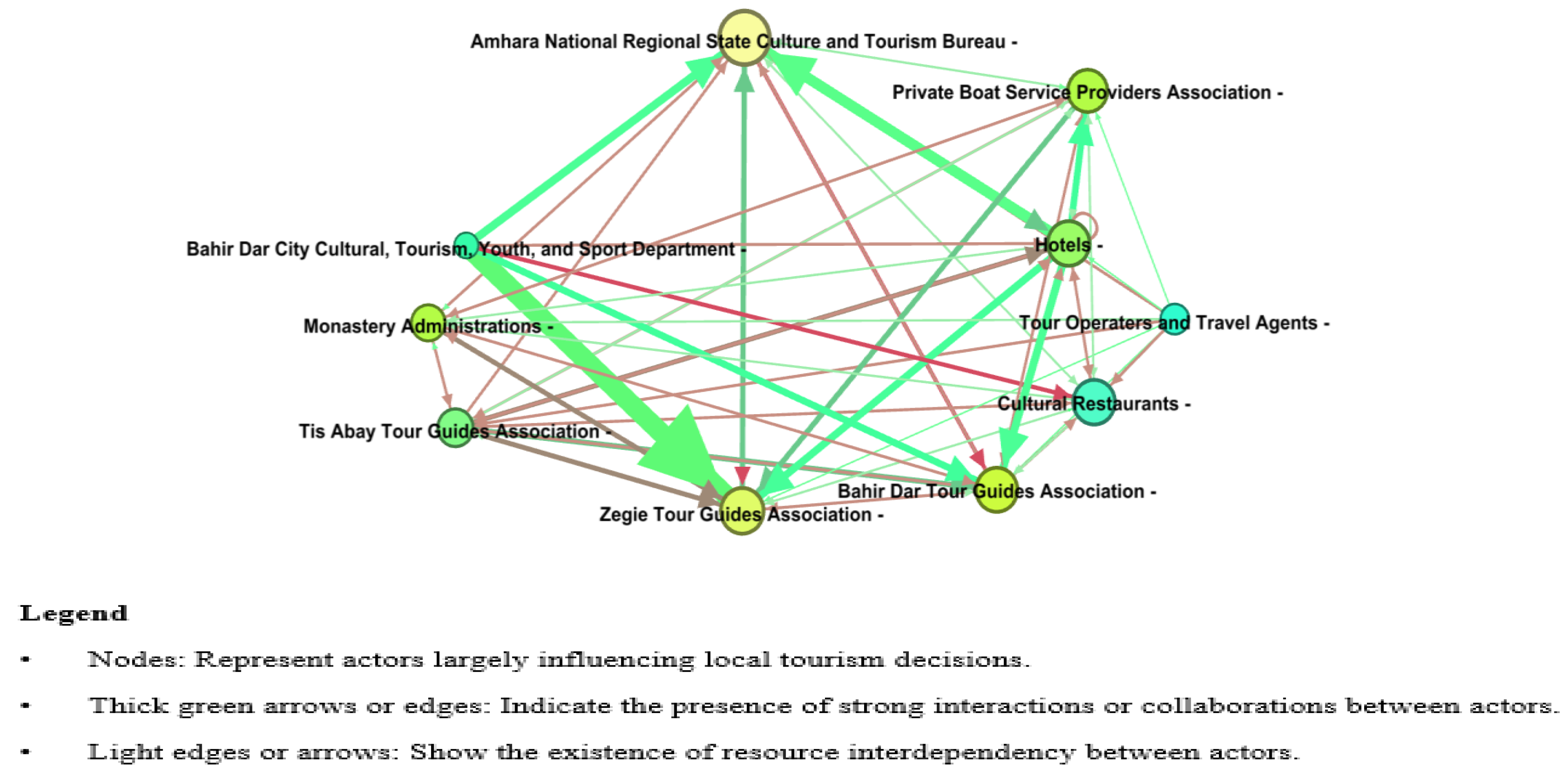

5.2.1. Actors with Strong Ties

“…since tourism businesses in the Lake Tana region are highly dependent on each other's resources, they experience strong interaction. As far as I know, in the Lake Tana region, tour operators rely on hotel rooms, car rentals, boat service providers, and local tour guides to serve local and international tourists. Large hotels and car rentals also depend on tour and travel organizers that arrange tours for international tourists who visit Bahir Dar City, Blue Nile Falls, and Lake Tana monasteries…“.

5.2.1. Network Density

| Number of actors | 54 |

| Total number of expected edges | 2862 |

| Total number of actual edges | 712 |

| Average degree | 13.18 |

| Network density | 0.25 |

5.2.3. Degree of Centrality

5.3. The Nexus Between Stakeholder Mapping and Sustainable Tourism Development

“…..In the Lake Tana region, identifying tourism stakeholders and the resources they control is crucial for understanding their level of influence in local tourism. It is also vital to facilitate resource sharing and collaboration. This ultimately supports and guides the development of sustainable tourism….”.

“To the best of my experience, tourism service provision in the Lake Tana region is struggling with a lack of coordination among actors involved in tourism activities. Therefore, mapping stakeholders by considering their power and interest in local tourism decisions would improve collaboration. It is also helpful to specify stakeholders' roles in local tourism, thereby contributing to sustainable tourism development”.

6. Discussion

7. Implications for Tourism Governance

7.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2. Practical Implications

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix One: A Comprehensive Local Tourism Stakeholder Map

Appendix Two: A Detailed Local Tourism Governance Network Map

Appendix Three: Degree of Centrality (DC) Report

| No. | List of actors | Raw degree | Normalized degree |

| 1 | Amhara National Regional State Culture and Tourism Bureau | 46 | 0.87 |

| 2 | Bahir Dar City Culture, Tourism, Youth, and Sport Department | 43 | 0.81 |

| 3 | Hotels | 41 | 0.77 |

| 4 | Zegie Tour Guides Association | 35 | 0.66 |

| 5 | Cultural Restaurants | 34 | 0.64 |

| 6 | Bahir Dar Tour Guides Association | 31 | 0.58 |

| 7 | Private Boat Service Providers Association | 28 | 0.53 |

| 8 | Tour Operators and Travel Agents | 28 | 0.53 |

| 9 | Tis Abay Tour Guides Association | 24 | 0.45 |

| 10 | Monastery Administrations | 20 | 0.37 |

| 11 | Ethiopian Shipping and Logistics | 19 | 0.36 |

| 12 | Amhara National Regional State Environment and Forest Protection Authority | 18 | 0.34 |

| 13 | Tourism Business Consultants | 17 | 0.32 |

| 14 | Souvenir Sellers | 16 | 0.30 |

| 15 | Domestic Visitors | 16 | 0.30 |

| 16 | Souvenir Producer | 15 | 0.28 |

| 17 | Small-Scale Food and Beverage Providers | 14 | 0.26 |

| 18 | Airport Taxi Service Providers | 14 | 0.26 |

| 19 | Nature and Biodiversity Conservation Union | 13 | 0.25 |

| 20 | Pensions | 13 | 0.25 |

| 21 | International Tourists | 13 | 0.25 |

| 22 | Amhara National Regional State Health Bureau | 12 | 0.23 |

| 23 | Bahir Dar Zuria Culture and Tourism Department | 11 | 0.21 |

| 24 | Hotel Managers Association | 11 | 0.21 |

| 25 | Zegie Community Administration | 11 | 0.21 |

| 26 | North Gojam Zone Culture and Tourism Department | 10 | 0.18 |

| 27 | Amhara National Regional State Trade and Market Development Bureau | 10 | 0.19 |

| 28 | Amhara National Regional State Peace and Security Bureau | 10 | 0.19 |

| 29 | Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahido Bahir Dar Diocese | 10 | 0.19 |

| 30 | Bahir Dar City Mayor's Office | 9 | 0.17 |

| 31 | Car Rentals | 8 | 0.15 |

| 32 | Amhara Tourism and Hospitality Professionals Association | 8 | 0.15 |

| 33 | Amhara National Regional State Transport and Logistics Authority | 7 | 0.13 |

| 34 | Amhara National Regional State Road Bureau | 6 | 0.11 |

| 35 | Amhara National Regional State Industry and Investment Bureau | 6 | 0.11 |

| 36 | Amhara National Regional State Urban and Infrastructure Bureau | 6 | 0.11 |

| 37 | Academic Institutions | 6 | 0.11 |

| 38 | Fishermen | 6 | 0.11 |

| 39 | Amhara Development Association | 6 | 0.11 |

| 40 | Tis Abay Community Administration | 5 | 0.09 |

| 41 | Hotel Owners Association | 5 | 0.09 |

| 42 | Dek Community Administration | 5 | 0.09 |

| 43 | Food Ingredient Suppliers | 5 | 0.09 |

| 44 | Insurance Companies | 5 | 0.09 |

| 45 | Organization for Rehabilitation and Development in Amhara | 5 | 0.09 |

| 46 | Society for Eco-Tourism and Biodiversity | 5 | 0.09 |

| 47 | Amhara National Regional State Finance Bureau | 5 | 0.09 |

| 48 | Amhara People Martyrs’ Memorial Monument | 4 | 0.08 |

| 49 | German Corporation for International Cooperation | 4 | 0.08 |

| 50 | Banks | 4 | 0.08 |

| 51 | Hotel Management Supporting Technology Providers | 3 | 0.05 |

| 52 | Private Media | 2 | 0.04 |

| 53 | Public Media | 2 | 0.04 |

| 54 | Jerusalem Children and Community Development Organization | 2 | 0.04 |

| Total number of actual edges or connections | 712 |

References

- Bichler, B. F.; Lösch, M. (2019). Collaborative governance in tourism: Empirical insights into a community-oriented destination. Sustainability (Switzerland). 2019, 11, 23. [CrossRef]

- Ramukumba, T. Tourism collaborative governance: The views of tourism small and medium-sized enterprises in rural areas. Interdisciplinary Journal of Management Sciences. 2025, 2, a04. [CrossRef]

- Eadens, L. M.; Jacobson, S. K.; Stein, T. V.; Confer, J. J.; Gape, L.; Sweeting, M. Stakeholder mapping for recreation planning of a Bahamian National Park. Society and Natural Resources, 2009, 22, 111–127. 10.1080/08941920802191696.

- Novelli, M.; Schmitz, B.; Spencer, T. Networks, clusters and innovation in tourism: A UK experience. Tourism Management. 2006, 27, 1141–1152. [CrossRef]

- Sedereviciute, K.; Valentini, C. Towards a more holistic stakeholder analysis approach. Mapping known and undiscovered stakeholders from social media. International Journal of Strategic Communication. 2022, 5, 221-239. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H. Managing conflict by mapping stakeholders’ views on ecotourism development using statement and place Q methodology. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism. 2022, 37, 100453. [CrossRef]

- Pavlovich, K. The evolution and transformation of a tourism destination network: The Waitomo Caves, New Zealand. Tourism Management. 2003, 24, 203-216. [CrossRef]

- Van der Zee, E.; Gerrets, A. M.; Vanneste, D. Complexity in the governance of tourism networks: Balancing between external pressure and internal expectations. Journal of Destination Marketing and Management. 2017, 6, 296–308. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.; Getz, D. Resource Dependency, Costs and Revenues of a Street Festival. Tourism Economics, 2007, 13, 143-162. [CrossRef]

- Prell, C.; Hubacek, K.; Reed, M. Stakeholder analysis and social network analysis in natural resource management. Society and Natural Resources. 2009, 22, 501-518. 10.1080/08941920802199202.

- Hillman, A. J.; Withers, M. C.; Collins, B. J. Resource dependence theory: A review. Journal of Management. 2009, 35, 1404–1427. [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, B.; Sharman, A. Collaboration in local tourism policymaking. Annals of Tourism Research, 1999, 26. [CrossRef]

- Silva, L. F.; Ribeiro, J. C.; Carballo-Cruz, F. Towards sustainable tourism development in a small protected area: Mapping stakeholders’ perceptions in the Alvão Natural Park, Portugal. Tourism Planning & Development. 2024, 21, 712–734. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. Q. T.; Young, T.; Johnson, P.; Wearing, S. Conceptualizing networks in sustainable tourism development. Tourism Management Perspectives. 2019, 32, 100575. [CrossRef]

- Lustický, M.; Zaunmüllerová, P.; Váchová, L.; Kadeřábková, J. Stakeholder mapping in selected Czech regions. In the 16th International Colloquium on Regional Sciences. Conference Proceedings (pp. 73–80). Masaryk University. 2013, 579-586. [CrossRef]

- Nalau, J.; Becken, S.; Noakes, S.; Mackey, B. Mapping tourism stakeholders’ weather and climate information-seeking behavior in Fiji. Weather, Climate, and Society, 2017, 9, 377–391. [CrossRef]

- Roxas, F. M. Y.; Rivera, J. P. R. ; Gutierrez, E. L. M. Mapping stakeholders’ roles in governing sustainable tourism destinations. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management. 2020, 45, 387-398. [CrossRef]

- Connor, T.; Frank, K.; Qiao, M.; Scribner, K.; Hou, J.; Zhang, J.; Wilson, A.; Hull, V.; Li, R.; Liu, J. Social network analysis uncovers hidden social complexity in giant pandas. Ursus, 2023, 34e9, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Hollstein, B.; Dominguez, S. Mixed methods social networks research. Design and Applications. New York: Cambridge University Press. (2014), 3-35.

- Scott, N.; Baggio, R. ; Cooper, C. (2008). Network Analysis and Tourism: From Theory to Practice. In Network Analysis and Tourism: From Theory to Practice. 2008, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Tessema, G. A.; van der Borg, J.; Minale, A. S.; Van Rompaey, A.; Adgo, E.; Nyssen, J.; Asrese, K.; Van Passel, S.; Poesen, J. Inventory and Assessment of Geosites for Geotourism Development in the Eastern and Southeastern Lake Tana Region, Ethiopia. Geoheritage. 2021, 13. 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Afni, I. N. Stakeholder mapping dalam Pelaksanaan Community Tourism Collaborative Governance (CTCG) di Desa Maron Wonosobo. Jurnal Litbang Provinsi Jawa Tengah. 2022, 19, 123–136. [CrossRef]

- Chhetri, A.; Arrowsmith, C.; Chhetri, P.; Corcoran, J. Mapping spatial tourism and hospitality employment clusters: An application of spatial autocorrelation. Tourism Analysis. 2013, 18, 559-573. [CrossRef]

- Valverde Sanchez, R. Conservation Strategies, Protected Areas, and Ecotourism in Costa Rica. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 2018, 36, 115–128. [CrossRef]

- Agapity, G.; Mugobi, T. Escapism experience an avenue for tourism development: Mapping the Test of Tanzania: Evidence from Arusha Region. African Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management. 2023, 2, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Dos Anjos, F. A.; Kennell, J. Tourism, governance, and sustainable development. Sustainability, 2019, 11. [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R. Governance and sustainable tourism: What is the role of trust, power, and social capital? Journal of Destination Marketing and Management, 2017, 6, 277-285. [CrossRef]

- Grindsted, T.; Madsen, M. T.; Madsen, M. Conflicting landscapes integrating sustainable tourism in nature park developments. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism. 2023, 23, 1–20. 10.1080/04353684.2023.2280262.

- Shoukat, M. H.; Shah, S. A.; Ali, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Mapping stakeholder role in building destination image and destination brand: Mediating role of stakeholder brand engagement. Tourism Analysis. 2023, 28, 29–46. [CrossRef]

- Waligo, V. M.; Clarke, J.; Hawkins, R. Implementing sustainable tourism: A multi-stakeholder involvement management framework. Tourism Management. 2023, 36 342–353. [CrossRef]

- Spenceley, A.; Casimiro, R. Tourism concessions in protected areas in Mozambique: Analysis of tourism concessions models in protected areas in Mozambique. USAID SPEED. 2012, 004. [CrossRef]

- Byrd, E. T. Stakeholders in sustainable tourism development and their roles: applying stakeholder theory to sustainable tourism development. Tourism Review. 2007, 62, 6–13. [CrossRef]

- Sautter, E. T.; Leisen, B. Managing stakeholders: A tourism planning model. Annals of Tourism Research. 1999, 26, 312–328. [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; McVea, J.F. A stakeholder approach to strategic management. SSRN Electronic Journal. 2001,1–29. [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. Harper & Row, New York. 1978. [CrossRef]

- Achmad, F.; Abdillah, I. T.; Amani, H. Decision-making process for tourism potential segmentation: A Case Study Analysis. International Journal of Innovation in Enterprise System. 2023, 7, 19–30. [CrossRef]

- Erdmenger, E. C. The end of participatory destination governance as we thought to know it. Tourism Geographies. 2023 (25). [CrossRef]

- Đurkin Badurina, J.; Soldić Frleta, D. Tourism dependency and perceived local tourism governance: Perspective of residents of highly-visited and less-visited tourist destinations. Societies. 2021, 11, 79. [CrossRef]

- Ha, D.W.; Choi, S.D.; Kwon, Y.K.; Kim, H.J. Analysis of tourism resource dependency on collaboration among local governments in the multi-regional tourism development. SHS Web of Conferences. 2014, 12, 01015. [CrossRef]

- Köseoglu, M. A.; Yick, Y. Y. M.; King, B. E. M.; Arici, H. E. Relational bibliometrics for hospitality and tourism research: A best practice guide. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management. 2022, 52, 316–330. [CrossRef]

- Molina-Collado, A.; Gómez-Rico, M.; Sigala, M.; Molina, M. V., Aranda, E.; Salinero, Y. Mapping tourism and hospitality research on information and communication technology: A bibliometric and scientific approach. Information Technology & Tourism. 2022, 24, 299-340. [CrossRef]

- Maghsoudi, M.; Aliakbar, S.; Mohammadi, A. Patterns and pathways: Applying social network analysis to understand user behavior in the tourism industry websites. arXiv preprint arXiv. 2023, 2308.08527. [CrossRef]

- Valeri, M.; Baggio, R. Social network analysis: Organizational implications in tourism management. International Journal of Organizational Analysis. 2021, 29, 342–353. [CrossRef]

- Fusch, P. I.; Ness, L. R. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qualitative Report, 2015, 20. 1408-1416. [CrossRef]

- Brandes, U. A faster algorithm for betweenness centrality. Journal of Mathematical Sociology. 2001, 25, 163–177. [CrossRef]

- Butts, C. T. Social network analysis with sna. Journal of Statistical Software. 2008, 24, 1–51. [CrossRef]

- Lestari, F.; Md Dali, M.; Che-Ha, N. The importance of a multistakeholder perspective in mapping stakeholders' roles toward city branding implementation. Policy & Governance Review, 2022, 6, 264. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. S.; Barbrook-Johnson, P.; Font, X. Participatory complexity in tourism policy: Understanding sustainability programmes with participatory systems mapping. Annals of Tourism Research. 2021, 90, 103269. [CrossRef]

- Purboyo, H.; Briliayanti, A. The effectivity of stakeholders’ collaboration on tourism destination governance in Pangandaran, West Java, Indonesia. Asean Journal on Hospitality and Tourism. 2019, 17(1), 25. [CrossRef]

- Montenegro, L. M.; Bulgacov, S. Reflections on actor-network theory, governance networks, and strategic outcomes. Brazilian Administration Review. 2014, 11. [CrossRef]

- Sudini, L. P.; Wiryani, M. Juridical analysis of local government authority on the establishment of local regulations for eco-tourism development. Diponegoro Law Review. 2022, 7, 53–69. [CrossRef]

- Derr, A. (2024). Using network density to evaluate and optimize collaboration intensity. Visible Network Labs. https://visiblenetworklabs.com/2024/11/13/using-network-density-to-evaluate-and-optimize-collaboration-intensity/.

- Becken, S.; Loehr, J. Tourism governance and enabling drivers for intensifying climate action. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2022, 32, 1743-1761. [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T.; Stronza, A. Collaboration theory and tourism practice in protected areas: Stakeholders, structuring and sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2009, 17, 169–190. [CrossRef]

- Provan, K. G.; Kenis, P. Modes of network governance: Structure, management, and effectiveness. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory. 2008, 18, 229–252. [CrossRef]

- Halim, H. A.; Nurasa, H.; Rusli, B.; Sugandi, Y. S. Governance networks in urban tourism policy. Jurnal Manajemen Pelayanan Publik, 2024, 8, 605–622. [CrossRef]

- Dangi, T. B.; Petrick, J. F. Enhancing the role of tourism governance to improve collaborative participation, responsiveness, representation, and inclusion for sustainable community-based tourism: A case study. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 2021, 7, 1029–1048. [CrossRef]

| Authors a | Key insights |

| Grindsted et al.[28] | Identifying stakeholders involved in tourism is crucial to understanding which actors play a vital role in promoting destination development. |

| Shoukat et al.[29] | Specifying the type, power, and interest of key actors in the tourism industry is essential for defining the responsibility of each stakeholder category. |

| Roxas et al.[17] | Tourism stakeholder mapping plays a crucial role in managing destination resources and improving collaborations. |

| Nguyen [14] | Stakeholder mapping highlights the importance of various stakeholders in influencing local tourism decisions and promoting sustainable tourism. |

| Waligo et al. [30] | The number of stakeholders involved in achieving sustainable tourism depends on the type and quantity of destination resources. |

| Casimiro & Spenceley [31] | Stakeholder mapping guides how stakeholders interact in the tourism setting. |

| Byrd [32] | Applying a stakeholder mapping approach is one of the most important steps considered in the sustainable tourism development process. |

| Sautter & Leisen [33] | Developing a framework for tourism planning and demonstrating the need to identify stakeholders can contribute to destination governance. |

| Freeman [34] | Understanding stakeholders' behavior and interests is crucial to enhancing sustainable development. |

| Interview participants | Number of interviewees | Codes assigned | Gender | Experience (in years) |

|

Tourism experts at government tourism institutions |

3 | TR 1 | Male | 15 |

| TR 2 | Female | 13 | ||

| TR 3 | Male | 10 | ||

| Tourism businesses |

6 |

TB 1 | Male | 20 |

| TB 2 | Male | 17 | ||

| TB 3 | Female | 8 | ||

| TB 4 | Female | 10 | ||

| TB 5 | Male | 14 | ||

| TB 6 | Male | 16 | ||

| Representatives from civil society organizations | 2 |

CS 1 | Male | 22 |

| CS 2 | Male | 18 | ||

| Academics and researchers | 2 |

AC 1 | Male | 16 |

| AC 2 | Male | 14 | ||

| FGD participants | ||||

| Hotels and restaurants |

3 |

FGD 1 | Female | 8 |

| FGD 2 | Male | 12 | ||

| FGD 3 | Male | 10 | ||

| Tour operator and travel agent | 1 | FGD 4 | Male | 17 |

| Local tour guides |

2 |

FGD 5 | Male | 17 |

| FGD 6 | Male | 6 | ||

| Boat service providers |

2 |

FGD 7 | Male | 20 |

| FGD 8 | Male | 13 | ||

| Souvenir seller | 1 | FGD 9 | Female | 14 |

| Local community representative | 1 | FGD 10 | Male | 16 |

| Tourism government institutions | 2 | FGD 11 | Female | 14 |

| FGD 12 | Male | 7 |

| Number of actors | 54 |

|---|---|

| Total number of expected edges | 2862 |

| Total number of actual edges | 712 |

| Average degree | 13.18 |

| Network density | 0.25 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).