Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials & Reagents

3. Results and Discussion

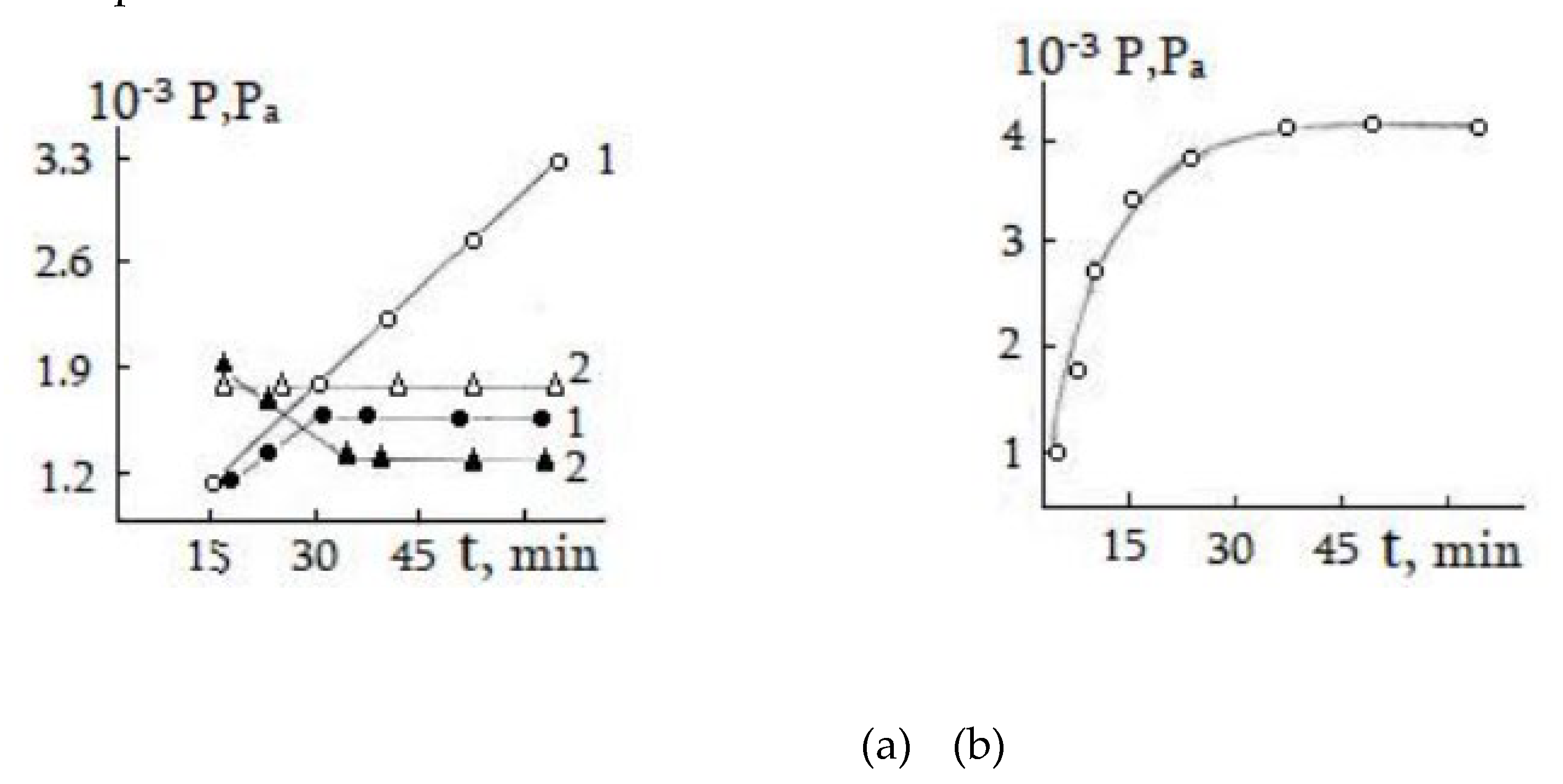

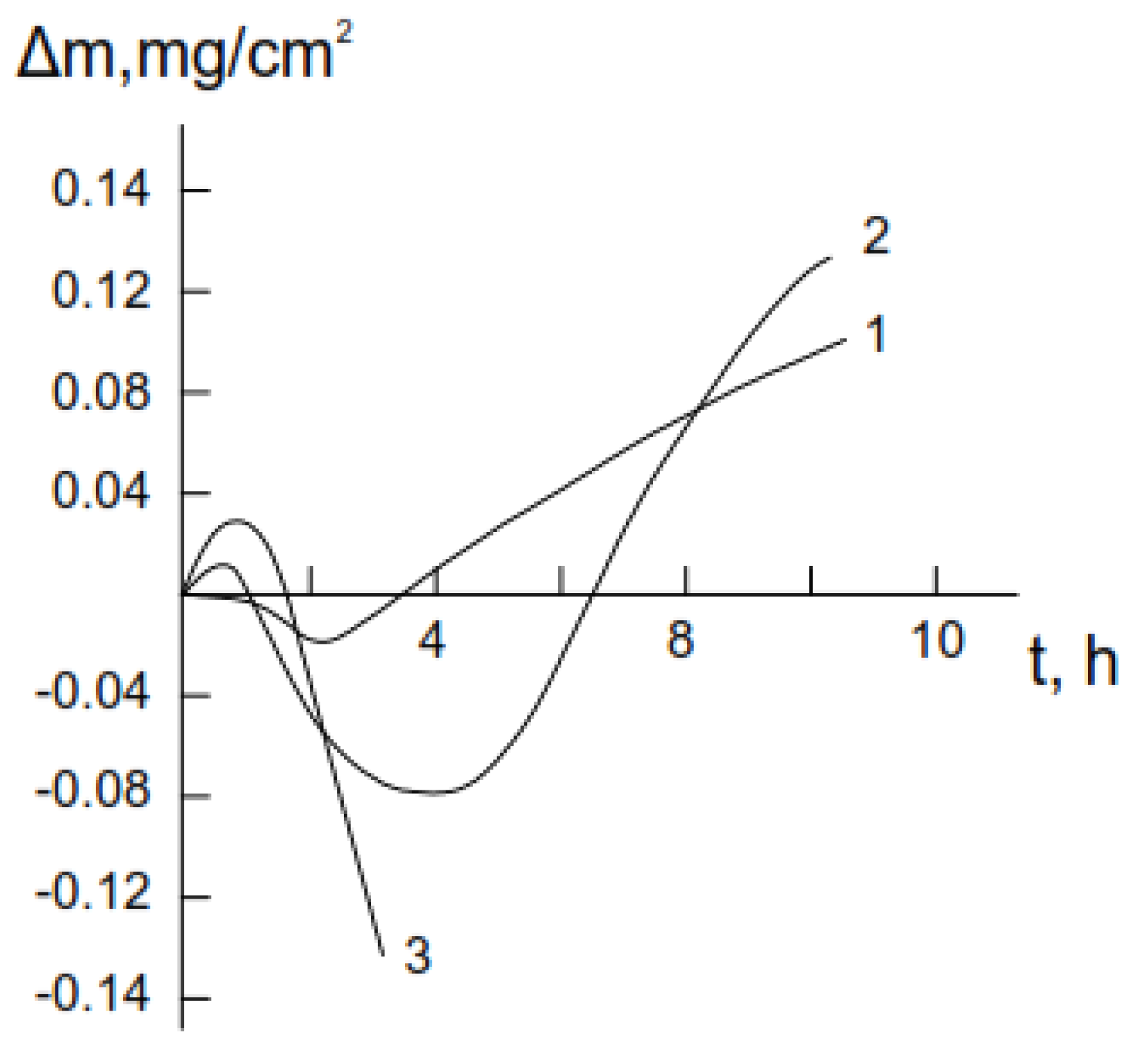

3.1. Decomposition of Hydrazine on the Surface of Single-Crystalline Germanium

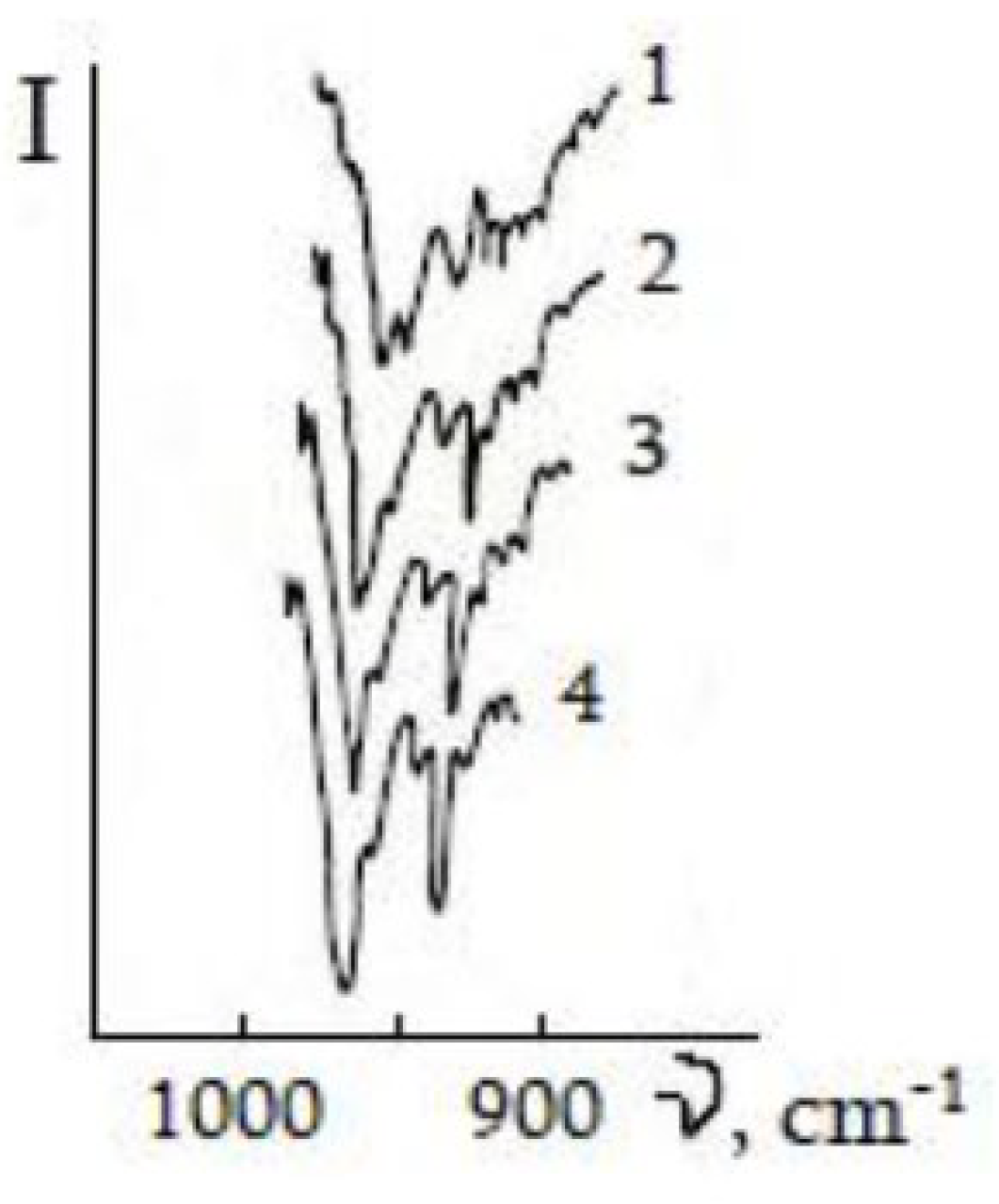

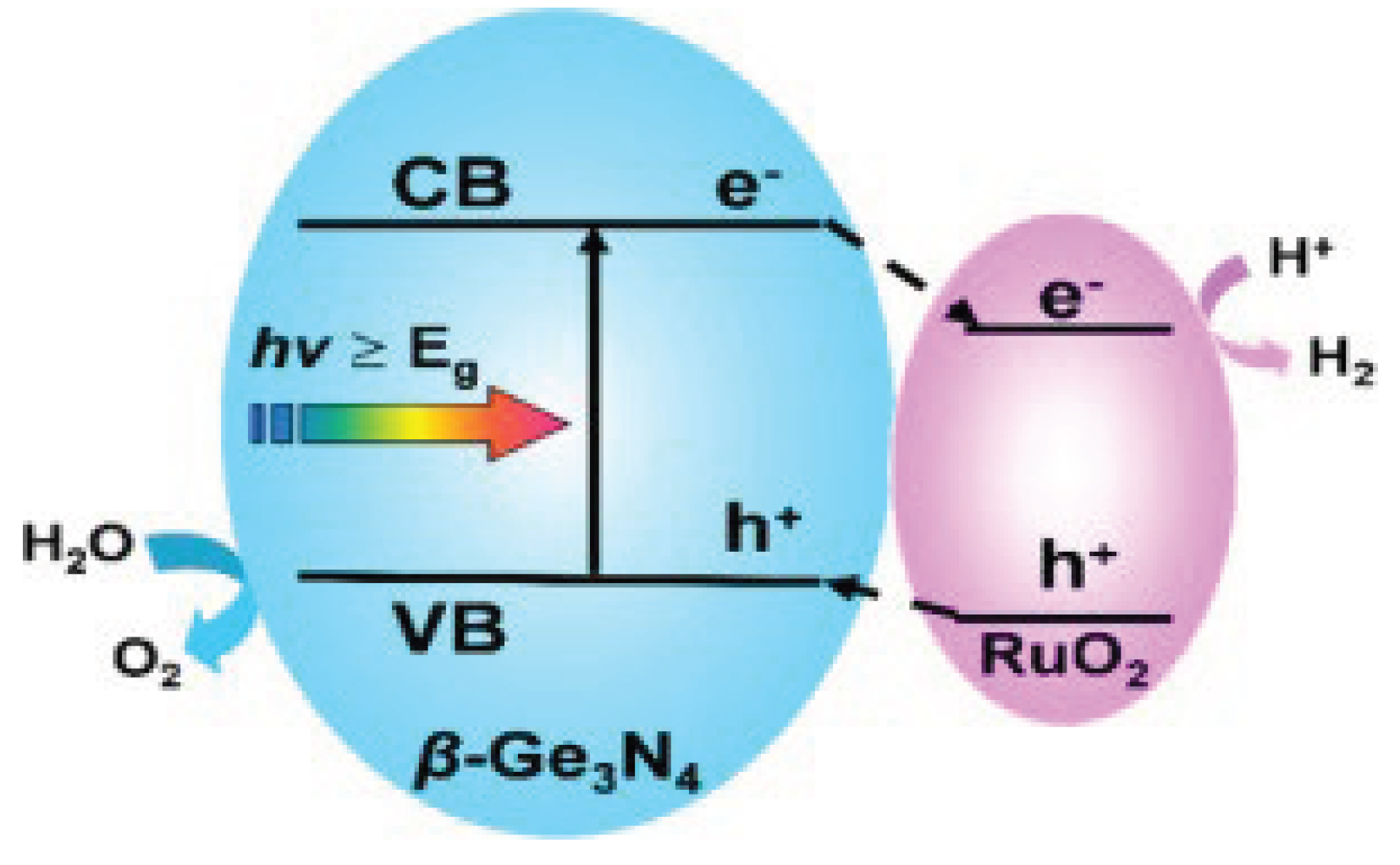

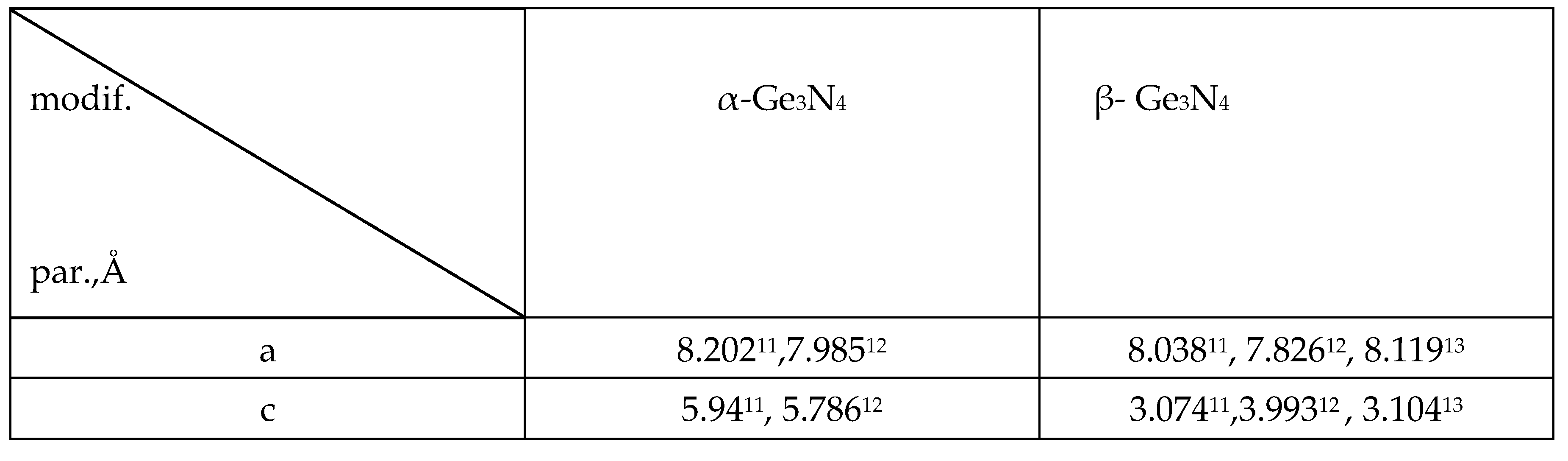

3.2. Formation of Nitride on Germanium Surface

3.3. The Possibility of Using of Germanium Nitride as a Photocatalyst in the Conversion of Carbon Monoxide to Dioxide

4. Conclusions

References

- Mallem K, Jagadeesh Chandra S V, Ju M et al., Influence of ultra-thin Ge3N4 passivation layer on structural, interfacial, and electrical properties of HfO2/Ge Metal-Oxide–Semiconductor devices. Nanosci Nanotechn, 20 (2020), 1039.

- Okamoto G, Kutsuki K, Hosoi T. et al., 2011. Electrical characteristics of Ge-based metal-insulator-semiconductor devices with Ge3N4 dielectrics formed by plasma nitridation. Nanosci and Nanotechn, 11 (2011), 2856.

- 3Huang Z, Su R, Yuan H et al., Synthesis and photoluminescence of ultra-pure α-Ge3N4 nanowires. Ceramics Intern, 4, (2018), 10858.

- Kim Sh, Hwang G, Jung J-W et al., Fast, scalable synthesis of micronized Ge3N4 @C with a high tap density for excellent lithium storage. Adv Funct Mater, 7 (2017), 1605975.

- Maggoini G, Carturan S, Fiorese L et al., Germanium nitride and oxynitride films for surface passivation of Ge radiation detectors. Appl Surface Sci, 393 (2017), 119.

- Yayak Y O, Sozen Y, Tan F et al., First-principles investigation of structural, Raman and electronic characteristics of single layer Ge3N4. Appl Surface Sci, 572 (2022), 15136.

- Sato J, Saito N, Yasmada Y et al., RuO2-loaded β-Ge3N4 as a non-oxide photocatalyst for overall water splitting. Amer Chem Soc, 127 (2005), 4150.

- Lee Y, Watanabe T, Takata T et al., Effect of high-pressure ammonia treatment on the activity of Ge3N4 photocatalyst for overall water splitting. Phys Chem B, 110 (2006), 17563.

- 9Maeda K & Domen K, New non-oxide photocatalysts designed for overall water splitting under visible light. Phys Chem C, 111, (2007), 7851.

- Ma Y, Wang M & Zhou X, First-principles investigation of β-Ge3N4 loaded with RuO2 cocatalysts for photocatalytic overall water splitting. Energy Chem, 44 (2020), 24-32.

- Ruddlesden S & Popper D, On the crystal structures of the nitrides of silicon and germanium. Acta Cryst, 11 (1958), 465-469.

- Sevic C & Bulutay C, Theoretical study of the insulating oxides and nitrides. Mater Sci, 42 (2007), 6555.

- Luo Y, Cang Y & Chen D, 2014. Determination of the finite temperature anisotropic elastic and thermal properties of Ge3N4: A first principle study. Computat Condens Matt, 1 (2014), 1, 1.

- Cang Y, Chen D, Yang F & Yang H, 2016. Theoretical studies of tetragonal, monoclinic and orthorhombic distortions of germanium nitride polymorphs. Chem Chinese Univ, 37 (2016), 674.

- Cang Y, Yao X, Chen D et al., First-principles study on the electronic, elastic and thermodynamic properties of tree novel germanium nitrides. Semiconduct, 37 (2016), 072002.

- Nakhutsrishvili I, Study of growth and sublimation of germanium nitride using the concept of Tedmon’s kinetic model. Oriental J Chem, 36 (2020), 850.

- Audrieth L F & Mohr P H, 1948. The chemistry of hydrazine. Chem Eng News, 26 (1948), 3746.

- Audrieth L F & Ogg B A, The chemistry of hydrazines. John Wiley & Sons: New York, USA, (1951), 256.

- Schmidt E W, One hundred years of hydrazine chemistry. Proceedings of 3rd Conference on Environmental Chemistry of Hydrazine Fuels: 15-17 September 1987, Florida, USA, 4-16.

- 20Krishnadasan A, Kennedy N, Zhao Y & Morgenstern H, Nested case-control study of occupational chemical exposures and prostate cancer in aerospace and radiation workers. Amer Industrial Medic, 50, (2007), 383.

- 21Turner J L, Rocket and spacecraft propulsion: Principles, practice and new developments. Springer Praxis Books. Prax. Publ. LTD: New York, USA, 2009, 390.

- 22 Schmidt E W & Gordon M S, The decomposition of hydrazine in the gas phase and over an iridium catalyst. Zeitsch. Phys. Chem., 227, (2013), 1301.

- 23 Chen Y, Zhao Ch, Liu X et al., 2023. Multi-scene visual hydrazine hydrate detection based on a dibenzothiazole derivative. Analyst, 148 (2022), 856.

- 24 Yan K, Yan L, Kuang W et al., Novel biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles for multifunctional applications: Electrochemical detection of hydrazine and treatment of gastric cancer. Environm Res, 238, (2023), 117081.

- Zhang G, Zhu Z, Chen Y et al., Direct hydrazine borane fuel cells using non-noble carbon-supported polypyrrole cobalt hydroxide as an anode catalyst. Sustain Energy Fuels, 7, (2023), 2594.

- Luo F, Pan Ch, Xie Y et al., Hydrazine-assisted acidic water splitting driven by iridium single atoms. Adv Sci, 10, (2023), 2305058.

- Burilov V A, Belov R N, Solovieva S E & Antipin I S, Hydrazine-assisted one-pot depropargylation and reduction of functionalized nitro calix[4]arenes. Russ Chem Bull, 72 (2023), 948.

- Rennebaum T, van Gerven D, Sean S et al., Hydrazine sulfonic acid, NH3NH(SO3), the bigger sibling of sulfamic acid. Chem Europe, 30, (2024), e202302526.

- Elts E, Windmann T, Staak D & Vrabec J, Fluid phase behavior from molecular simulation: Hydrazine, Monomethylhydrazine, Dimethylhydrazine and binary mixtures containing these compounds. Fluid Phase Equilibr, 322/323 (2012), 79.

- Ahlert R C, Bauerle G L & Lecce J V, Density and viscosity of anhydrous hydrazine at elevated temperatures. Chem Eng Data, 7, (1962), 158.

- Zhao B, Song J, Ran R & Shao Z, Catalytic decomposition of hydrous hydrazine to hydrogen over oxide catalysts at ambient conditions for PEMFCs. Hydrogen Energy, 1 (2012), 1133.

- Frolov V M., Catalytic decomposition of hydrazine on germanium. Russ Kinetics and Catalysis, 6 (1965), 149.

- Nakhutsrishvili I, Adamia Z & Kakhniashvili G, Gas etching of germanium surface with water vapors contained in nitrogen-containing reagents. Appl Surface Sci, 2, (2024), 1.

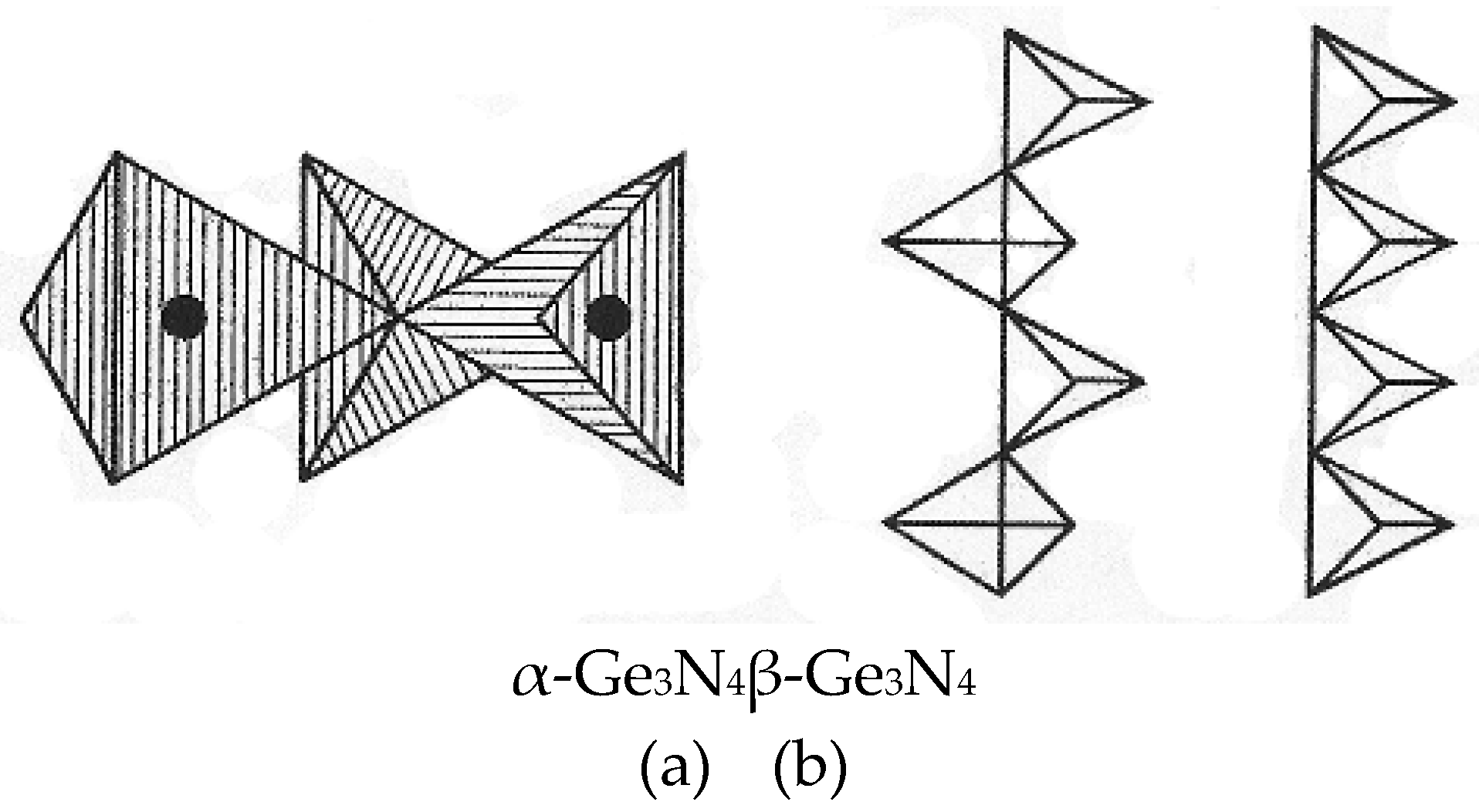

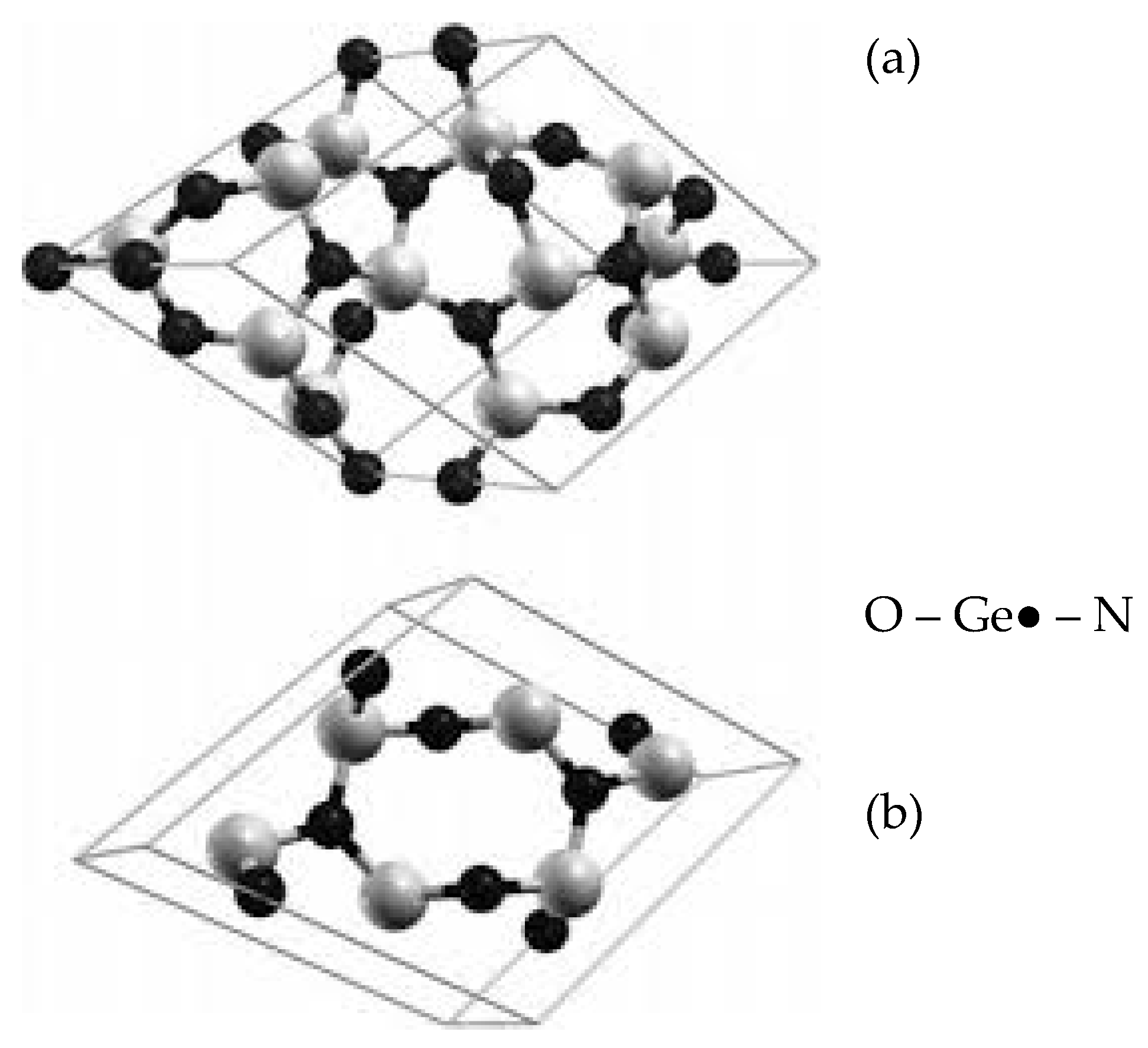

- Vardosanidze Z, Nakhutsrishvili I & Kokhreidze R, Conditions of formation of α- and β-modifications of Ge3N4 and preparation of germanium oxynitride dielectric films. Coating Sci and Techn, 11 (2024), 1.

- Ekong A, Akpan V A & Ebomwonyi O, DMC and VMC calculations of the electric dipole moment and the ground-state total energy of hydrazine molecule using CASINO-code. Lett Chem Phys and Astronomy, 59 (2015), 106.

- Krylov O V, Frolov V M, Fokina E A & Rufov Yu N, Catalytic decomposition of hydrazine. 8th Mendeleev Congress on General and Applied Chemistry - Section of Physical Chemistry: 16-23 March 1958, Moskow, USSR, 172.

- Ye J, Wan Y & Li Y, Construction of dual S-scheme heterojunctions g-C3N4/CoAl LDH@MIL-53(Fe) ternary photocatalyst for enhanced photocatalytic H2 evolution. Appl. Surface Sci., 2025, 684, 161862.

- Wtulich M, Skwierawska A, Ibragimov S & Lisowska–Oleksial A, Exploring the role of carbon nitrides (melem, melon, g-C3N4) in enhancing photoelectrocatalytic properties of TiO2 nanotubes for water electrooxidation. Appl Surface Sci, 685 (2025), 161994.

- Mohapatra L, Paramanik L, Choi D & Yoo S H, Advancing photocatalytic performance for enhanced visible-light-driven H2 evolution and Cr(VI) reduction of g-C3N4 through defect engineering via electron beam irradiation. Appl Surface Sci, 685 (2025), 161996.

- Sharma P, Mukherjee D, Sakar S et al., Pd doped carbon nitride (Pd-g-C3N4): an efficient photocatalyst for hydrogenation via an Al–H2O system and an electrocatalyst towards overall water splitting. Green Chem, 24 (2022), 5535.

- Chen J, Fang S, Shen Q et al., Recent advances of doping and surface modifying carbon nitride with characterization techniques. Catalysts, 12 (2022), 962.

- Ohkawa K, Ohara W, Ushida D & Deura M, Highly stable GaN photocatalyst for producing H2 gas from water. Japan Appl Phys, 52 (2013), 08JH04.

- Shimosako N & Sakama H, Quantum efficiency of photocatalytic activity by GaN films. AIP Adv, 11 (2021), 025019.

- Schäfer S. Wyrzgol A, Caterino R et al., Platinum nanoparticles on gallium nitride surfaces: Effect of semiconductor doping on nanoparticle reactivity. Amer Chem Soc, 134 (2012), 12528.

- Guler U, Suslov S, Kildishev A V et al., Colloidal plasmonic titanium nitride nanoparticles: properties and applications. Nanophotonics, 4 (2015), 269.

- Zhou X, Zolnhofer E M, Nguyen N T et al., Stable cocatalyst-free photocatalytic H2 evolution from oxidized titanium nitride nanopowders. Angew Chem, 54, (2015), 13385.

- Ma S S K, Hisatomi T, Maeda K et al., Enhanced water oxidation on Ta3N5 photocatalysts by modification with alkaline metal alts. Amer Chem Soc, 134 (2012), 19993.

- Harb M & Basset J-M, Predicting the most suitable surface candidates of Ta3N5 photocatalysts for water-splitting reactions using screened coulomb hybrid DFT computations. Phys Chem C, 124 (2020), 2472.

- Shirvani F & Shokri A, Photocatalytic applicability of HfN and tuning it with Mg and Sc alloys: A DFT and molecular dynamic survey. Phys B: Condensed Matter, 649 (2023), 414459.

- O’neill D B, Frehan S K, Zhu K et al., Ultrafast photoinduced heat generation by plasmonic HfN nanoparticles. Adv Opt Materials, 9 (2021), 2100510.

- Yang Q, Chen Z, Yang X et al., Facile synthesis of Si3N4 nanowires with enhanced photocatalytic applications. Materials Lett, 212 (2018), 41.

- Munif A N, Firas J & Kadhim F J, Structural characteristics and photocatalytic activity of TiO2/Si3N4 nanocomposite synthesized via plasma sputtering technique. Iraqi Phys, 22 (2024), 99.

- Fujishima A, Rao T N & Tryk D A, Titanium dioxide photocatalysis. Photochem and Photobiol C: Photochem Rev, 1 (2000), 1.

- Seifikar F & Habibi-Yangjeh A, Floating photocatalysts as promising materials for environmental detoxification and energy production: A review. Chemosphere, 355 (2024), 141686.

- Mohamadpour F & Amani A M, Photocatalytic systems: reactions, mechanism, and applications. RSC Adv, 14 (2024), 20609.

- Beil S B, Bonnet S, Casadevall C et al., Challenges and future perspectives in photocatalysis: Conclusions from an interdisciplinary workshop. JACS, 4 (2024), 2746.

- Chakravorty A & Roy S, A review of photocatalysis, basic principles, processes, and materials. Sust Chem Envir, 8 (2024), 100155.

- Haag W M, Methods to reduce carbon monoxide levels at the workplace. Preventive Medic, 8 (1979), 369.

- Samadi P, Binczarski M J, Pawlaczyk A et al., CO oxidation over Pd catalyst supported on porous TiO2 prepared by plasma electrolytic oxidation (PEO) of a Ti metallic carrier. Materials, 15 (2022), 4301.

- Kersell H, Hooshmand Z, G. Yan G et al., CO oxidation mechanisms on CoOx-Pt thin films. Amer Chem Soc, 142 (2020), 8312.

- Rostami A A, Hajaligol M, Li P et al., Formation and reduction of carbon monoxide. Beiträge zur Tabakforsch Intern, 20 (2014), 439.

- Antony A G, Radhakrishnan K, Saravanan K & Vijayan V, 2020. Reduction of carbon monoxide content from four stroke petrol engine by using subsystem. Vehicle Struct. & Systems, 12 (2020), 384.

- Mamilov S, Yesman S, Mantareva V et al., Optical method for reduction of carbon monoxide intoxication. Bulg Chem Commun, 52 (2020), 142.

- Bujak J, Sitarz P & Pasela R, 2021. Possibilities for reducing CO and TOC emissions in thermal waste treatment plants: A case study. Energies, 14 (2021), 2901.

- Ruqia B, Tomboc G M, Kwon T et al., Recent advances in the electrochemical CO reduction reaction towards highly selective formation of Cx products (X = 1–3). Chem Catalysis, 2 (2022), 1961.

- Wilbur Sh, Williams M, Williams R et al., Toxicological profile for carbon monoxide. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry: Atlanta, USA. Bookshelf ID: NBK153696 (2012).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).