1. Introduction

Macrophages are recognized as versatile innate immune cells integral to tissue homeostasis, immune surveillance, and repair mechanisms [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Their functional status is highly plastic, shifting along a spectrum defined by two classic extremes: the classically activated (M1) phenotype, characterized by pro-inflammatory cytokine production and microbicidal activity [

6,

7,

8]; and the alternatively activated (M2) phenotype, typically involved in immunosuppression, tissue remodeling, and resolution of inflammation [

9,

10,

11]. The specific balance of M1 and M2 phenotypes within a tissue microenvironment often dictates the progression and outcome of diseases ranging from pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis to malignant transformation [

12,

13,

14].

Alveolar macrophages (AMs), resident in the lung, continuously interact with external factors and represent a critical sentinel population [

15,

16,

17,

18]. Phenotyping of AM subpopulations is necessary for diagnosing local immune status and for developing targeted interventions aimed at correcting pathological M1/M2 imbalances, such as the excessive accumulation of M2-like tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) that promote tumor growth [

19,

20,

21]. The role of TAMs is now well-established. They constitute a critical component of the tumor microenvironment (TME) [

22,

23], typically exhibiting an M2-like phenotype characterized by immunosuppressive activities that foster tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis, while suppressing anti-tumor immune responses. This impact on TAMs can be harnessed to reprogram from «cold» to «hot» TME of tumors [

24,

25], such as through the use of Paclitaxel, but similar approaches can be employed for various other conditions involving macrophages.

Many therapeutic agents have secondary immunomodulatory properties that influence macrophage polarization. For example, some anti-inflammatory drugs like curcumin [

32,

33,

34,

35] and coumarin are known to reduce the pro-inflammatory M1 population, making them relevant for treating M1-dominant diseases like bronchiectasis. Doxorubicin [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30], a widely used chemotherapeutic, also exerts such effects and is known to reprogram pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages toward an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype. Given that bronchiectasis is characterized by an M1-skewed profile and chronic inflammation, we selected doxorubicin as a model drug to achieve targeted therapeutic remodeling.

Our research aims to test whether anti-inflammatory drugs encapsulated in targeted ligands can reprogram alveolar macrophages (AMs) from a dysfunctional state back to a healthy one. Within the context of pulmonary diseases, our objective is to regulate AMs to reduce inflammation and restore their protective functions. Local delivery using targeted methods provides a more precise approach for this regulation compared to systemic administration [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36].

To analyze these cellular shifts, we use "macrophage fingerprinting." This analytical approach allows us to classify macrophages into distinct functional states based on their surface markers and cytokine profiles. The three primary phenotypes are the resting state (M0), the pro-inflammatory state (M1), and the tissue-remodeling or anti-inflammatory state (M2). By generating a detailed "fingerprint," we can map the macrophage populations to distinguish between healthy and diseased states and measure the effectiveness of our intervention.

Our previous work built upon this foundation, developing a more refined method for creating phenotypic profiles of macrophage populations [

37,

38]. This approach allows us to identify specific subpopulations within the M1, M2a, M2b, M2c, and M2d categories, as well as M3. However, it is important to note that there is a continuous spectrum of variations within these categories. Now, we are advancing this idea from profiling to targeted intervention. Our current research aims to leverage this understanding to not only identify the specific "good" (balanced) and "bad" (pathogenic M1) profiles within patient samples but, crucially, to selectively correct these imbalances. This is achieved by employing specific ligands, engineered to carry Dox, which can engage particular macrophage subsets and reprogram them toward a more beneficial state.

Therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating M1/M2 AMs balance. However, a major challenge is the lack of tools to accurately assess the composition of macrophage populations directly in patient-derived samples. To address this, we have developed a novel diagnostic platform consisting of a panel of synthetic ligands designed to create a "fingerprint" or profile of the macrophage populations present.

C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) on the macrophage surface not only mediate pathogen recognition but also play fundamental roles in regulating macrophage polarization [

39,

40,

41,

42]. The Mannose Receptor (CD206), a canonical M2a marker, is a key target for ligands featuring mannose or complex mannosylated clusters [

39,

43,

44]. Conversely, the Macrophage Galactose-type Lectin (MGL/CD301) is associated with M2 subsets and typically binds N-acetylgalactosamine and certain galactose structures [

45,

46]. To create a comprehensive phenotypic profile, this study utilized a panel of five synthetic glycoligands (L1–L5) built on a polyethyleneimine (PEI) polymer scaffold, which provides multivalency necessary for high-affinity CLR binding. These ligands include linear mannose (L1), cyclic mannose (L2), linear galactose (L3), cyclic galactose (L4), and a complex GlcNAc2-trimannoside cluster (L5). The application of this panel allows for the generation of a quantitative binding profile, providing a molecular basis for phenotypic deconvolution.

Firstly, we propose that our glyco-ligands can selectively deliver anti-inflammatory drugs to specific macrophage subsets. We hypothesize that direct interactions between the glycan structure of these ligands and C-type Lectin Receptors (CLRs) trigger intracellular signaling, which is predicted to influence the M1/M2 polarization state of macrophages. The core of our work is to use this glyco-ligand platform to address macrophage polarization imbalances. For instance, in diseases like bronchiectasis (M1-dominant profile) or tumors (M2-dominant profile), our platform serves a dual purpose: identifying the imbalance and tracking its correction during therapy.

This study's primary goal was to validate our macrophage profiling system's sensitivity. We aimed to (1) establish a baseline profile of alveolar macrophages (AMs) from BALF and (2) track its remodeling after Dox treatment. Additionally, we investigated if these ligands could selectively target and eliminate or reprogram specific macrophage subsets, thus demonstrating a proof-of-concept for 'correcting' dysfunctional profiles.

Ultimately, this platform could be developed into a diagnostic test. Such a system would assess patient samples to determine therapeutic efficacy and identify the most suitable treatment for various diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Case and Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL) Fluid Collection

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient's legal guardian.

BALF) samples were collected from three pediatric patients undergoing diagnostic bronchoscopy at Morozovskaya Children's City Clinical Hospital. All procedures were performed after obtaining informed consent from the patients' legal guardians, following protocols approved by the local ethics committee. The patients presented with chronic respiratory symptoms and underlying lung conditions.

BALF was obtained during flexible bronchoscopy performed under general anesthesia. Lavage was performed according to standard procedures, typically involving the instillation and aspiration of sterile saline solution from affected lung segments identified during the procedure or via prior imaging. Samples were processed immediately for subsequent analysis, including cytological examination and ex vivo cell culture experiments.

2.2. Reagents

Polyethyleneimine (PEI, 1.8 kDa), mannan, α-D-mannose (Man), methyl α-D-mannoside (Me-Man), D-galactose, D-lactose, and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Mannotriose-di-(N-acetyl-D-glucosamine) (triMan-GlcNAc2) was obtained from Dayang Chem Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China). Carbonyldiimidazole (CDI) was acquired from GL Biochem Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All other chemicals and solvents, including DMSO, NaBH3CN, and buffer components, were of chemically pure grade and sourced from Reakhim Production (Moscow, Russia).

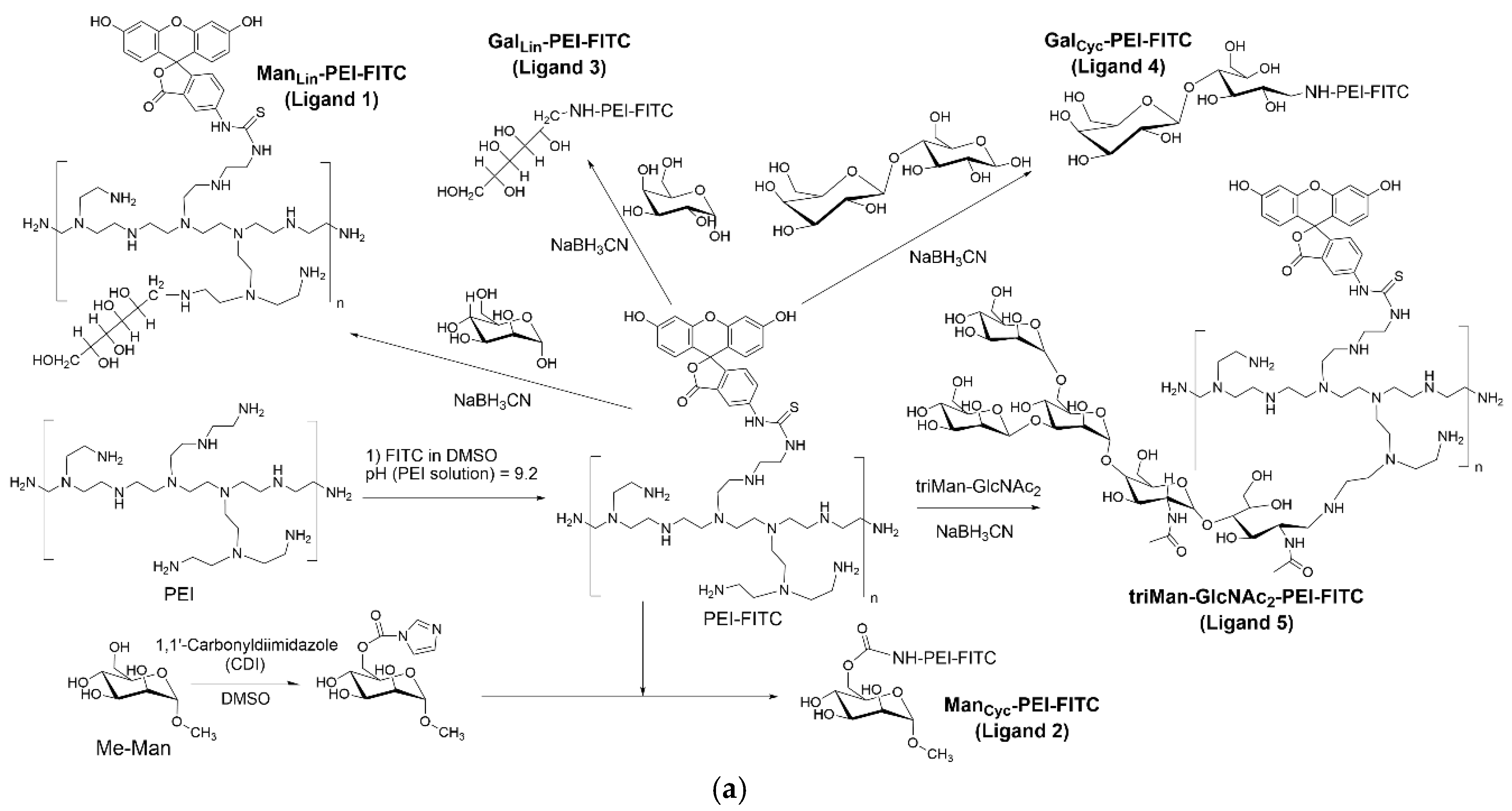

2.3. Synthesis of FITC-Labeled Profiling Ligands

The synthesis of profiling ligands has been described previously [

37]. Briefly, PEI (1.8 kDa) was dissolved in 0.01 M HCl, and the pH was adjusted to 9.2 with sodium borate buffer. A solution of FITC in DMSO was added dropwise to achieve an equimolar ratio with PEI. The resulting PEI-FITC conjugate was purified by dialysis (MWCO 3.5 kDa) against water.

For conjugation with carbohydrates via reductive amination (mannose, galactose, lactose, triMan-GlcNAc2), the respective saccharide was added to the PEI-FITC solution in a 20-fold molar excess, along with NaBH3CN. The pH was adjusted to 5.0, and the reaction proceeded for 12 hours at 50°C. For methyl-α-mannoside (Me-Man), its 6-OH group was first activated with CDI in DMSO. This activated sugar was then added to the PEI-FITC solution (pH 7.4) and incubated for 6 hours at 50°C. All final conjugates were purified by extensive dialysis (MWCO 3.5 kDa) and lyophilized.

2.4. Synthesis of Doxorubicin-Conjugated Remodeling Ligands

To synthesize the remodeling ligands, doxorubicin (Dox) was first activated. Dox was dissolved (1 mg/mL) in sodium borate buffer (pH 9.2), and a 2-fold molar excess of carbonyldiimidazole (CDI) in DMSO was added. The mixture was incubated for 2 hours at 40 °C to form an activated Dox intermediate. This solution was then slowly added to a solution of PEI (1.8 kDa) in the same buffer and stirred for 6 hours at 50°C to form the PEI-Dox conjugate. The product was purified by dialysis (MWCO 3.5 kDa) against water.

The subsequent conjugation of the five carbohydrate moieties (L1-L5) to the PEI-Dox backbone was carried out using the same reductive amination and CDI-activation protocols described for the FITC-labeled ligands in the section above. All final Dox-conjugated ligands were purified by dialysis and lyophilized before use.

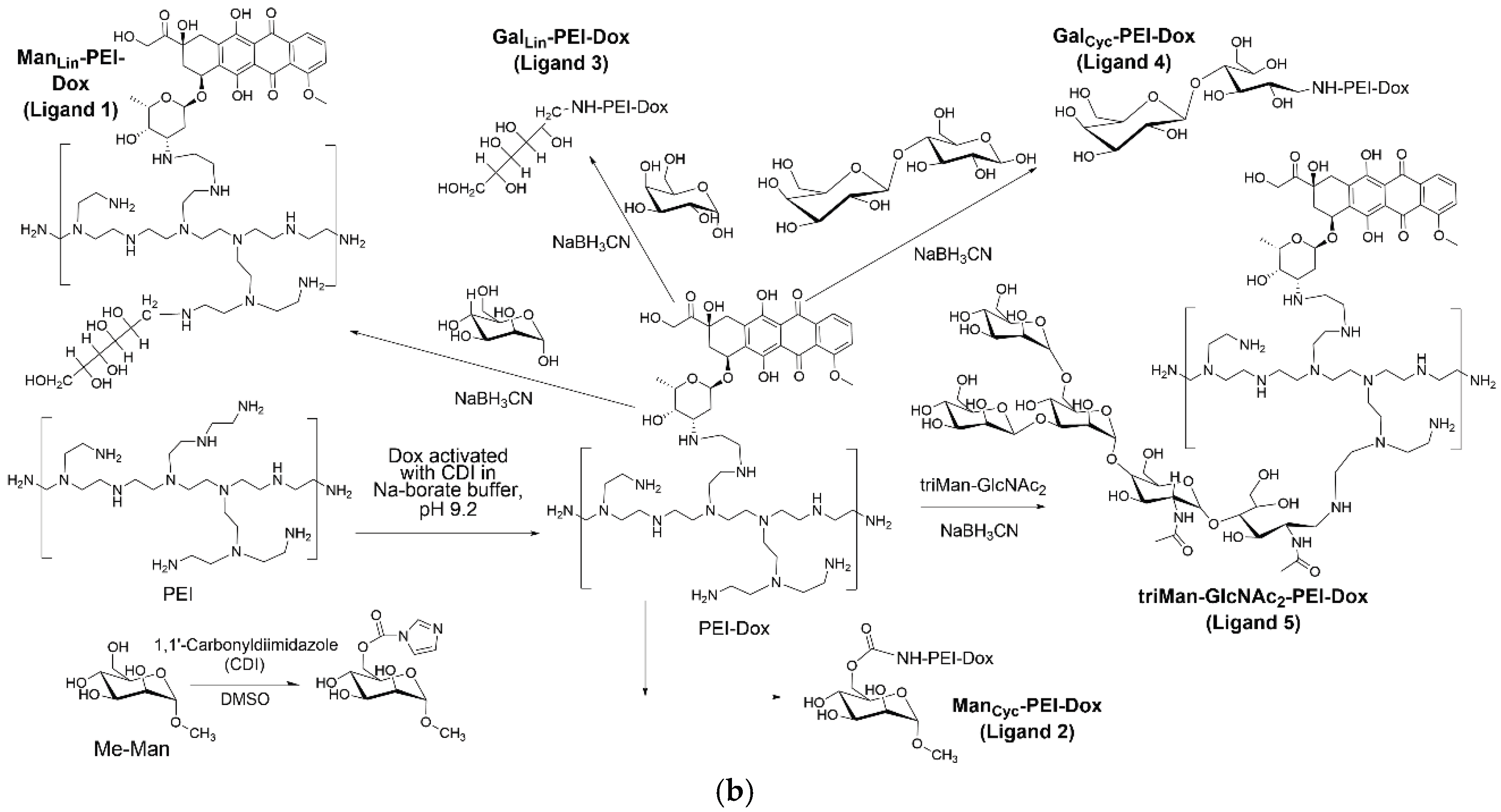

2.5. Physicochemical Characterization of Glycoligand Conjugates

FTIR Spectroscopy. Spectra of the conjugates were recorded using a Bruker Tensor 27 spectrometer (Bruker, Bremen, Germany) for solutions and a MICRAN-3 FTIR microscope (Simex, Novosibirsk, Russia) for solid films to confirm the covalent attachment of the carbohydrate and Dox/FITC moieties to the PEI backbone.

NMR Spectroscopy. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker DRX-500 instrument. Samples (10-15 mg) were dissolved in D2O to confirm the presence of signals corresponding to both the polymer and the conjugated carbohydrate structures.

Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS). The hydrodynamic diameter and ζ-potential of the ligand particles in PBS were measured using a Zetasizer Nano S (Malvern, Worcestershire, UK) to determine their size and surface charge characteristics.

2.6. Isolation and Culture of Alveolar Macrophages

The collected BALF was centrifuged at 4000 × g for 10 minutes at 4 °C to pellet the cellular components. The cell pellet was washed twice with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in PBS for Quantitative Analysis and Imaging Experiments or on RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin for remodeling experiments.

2.7. Macrophage Remodeling and Phenotypic Profiling Assay

Isolated AMs were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well and allowed to adhere for 2 hours. The cells were then incubated for 24 hours with the five different Dox-conjugated remodeling ligands (Dox-L1 to Dox-L5) at a final concentration of 10 µg/mL. A control group was incubated with medium alone (intact cells).

After the 24-hour remodeling period, the wells were washed three times with PBS to remove unbound conjugates and non-adherent cells. The remaining adherent cells were then profiled by incubating them for 1 hour with the panel of five FITC-labeled profiling ligands (FITC-L1 to FITC-L5) at a concentration of 5 µg/mL.

2.8. Quantitative Analysis and Imaging

The fluorescence intensity of the bound L1-L5 FITC-ligands was measured using a plate fluorometer (Ex/Em = 485/520 nm). The percentage of bound ligand was calculated relative to the initial fluorescence added to each well. For competitive binding assays, cells were pre-incubated with 1 mg/mL mannan for 30 minutes before the addition of FITC-ligands (ML1-ML5).

For visualization, cells were cultured on glass-bottom dishes and processed using the same remodeling and profiling protocol. Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) was performed to visualize FITC fluorescence (ligand binding) and the intrinsic Dox fluorescence (drug delivery & remodeling).

2.9. Deconvolution Analysis of Macrophage Subpopulations

The quantitative binding profiles of the treated BALF samples were analyzed using a non-negative least squares (NNLS) deconvolution algorithm. This analysis calculated the relative contribution of three reference macrophage phenotypes (M0 monocytes, M1-polarized macrophages, and M2a-polarized macrophages) to the observed experimental binding profile, allowing for a quantitative assessment of the macrophage polarization state.

3. Results and Discussion

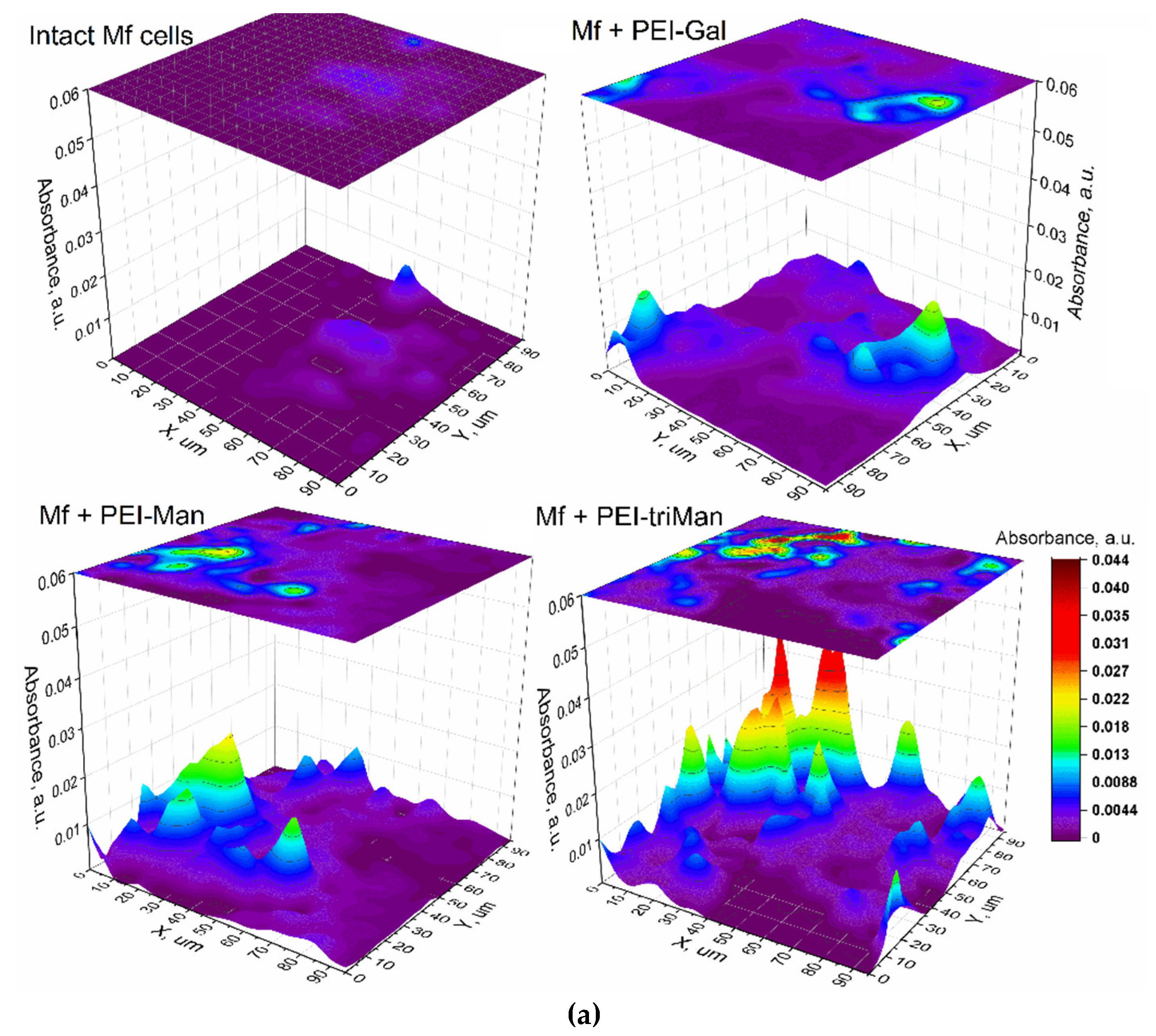

2.2. Nanoscale Receptor Mapping and Ligand Binding Specificity for CD206+ Macrophages

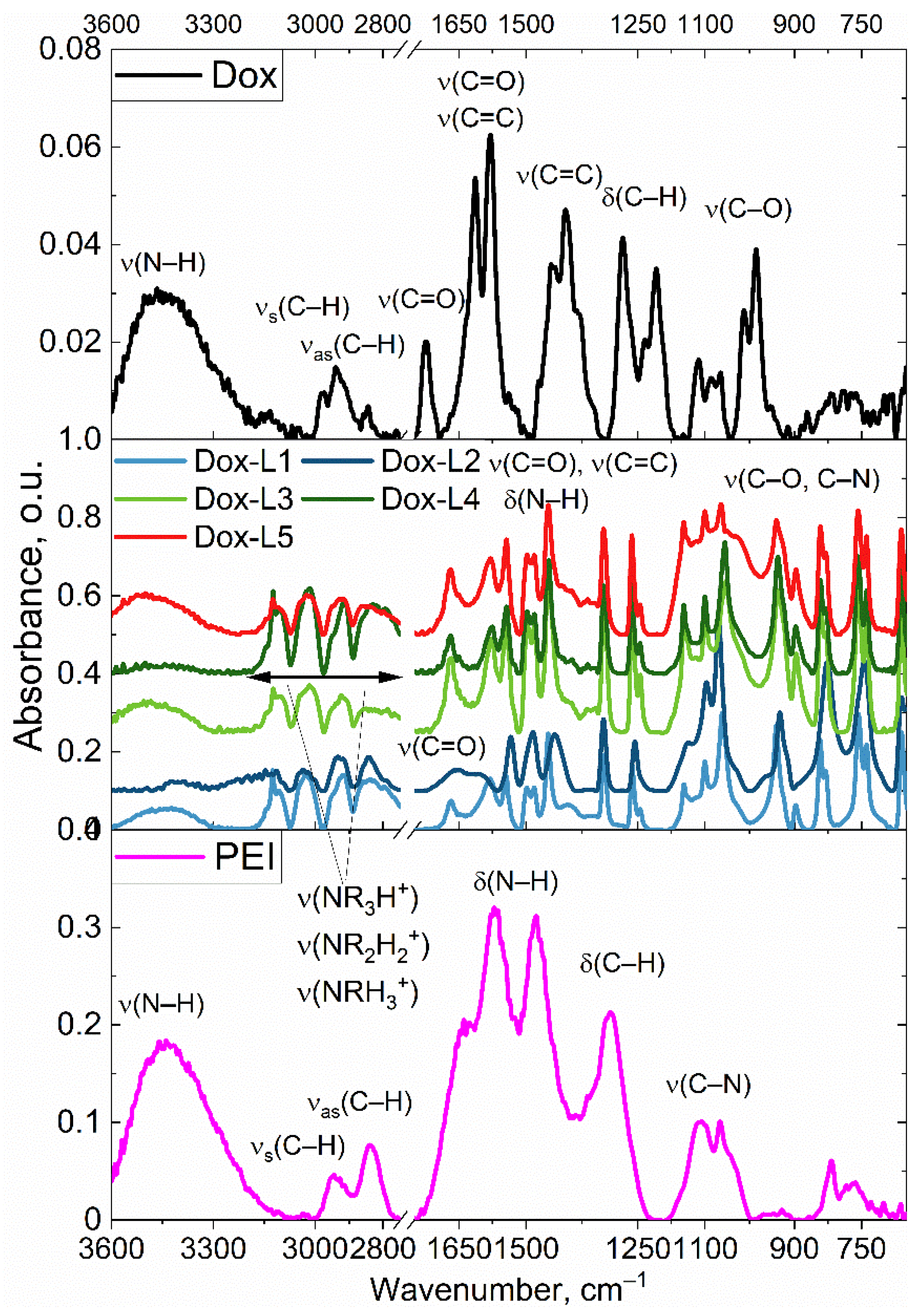

The objective of this study was to precisely map the distribution and quantify the interaction of our synthesized glycan ligands with specific receptors on individual alveolar macrophages. To achieve this, we employed nanoscale FTIR microscopy to characterize the binding patterns of selected ligands at the single-cell level, enabling us to visualize receptor positioning and compare binding efficiencies across different ligands.

Our glycan-based labeling strategy revealed differential affinities for specific macrophage receptor populations, as evidenced by varying binding intensities. Ligands L2 (cyclic mannose), L3 (linear galactose), and L5 (GlcNAc2-trimannoside cluster) were selected for detailed investigation due to their hypothesized interaction with CD206 (mannose receptor), a key marker predominantly found on M2-polarized macrophages. As depicted in

Figure 3, FTIR microscopy provided distinct binding signatures for these ligands on the macrophage surface. We quantified ligand-specific binding by measuring the combined signal from the PEI-polymer backbone (I1000) and the characteristic IR absorption of the carbohydrate moiety (I1650). Notably, L2 and L5 exhibited significant and distinct binding patterns, suggesting substantial interaction with CD206+ cells within the BALF population. Ligand L3 also showed detectable binding, though its distribution implies either a lower affinity or interaction with a receptor subset subtly different from those targeted by L2 and L5.

These observed binding patterns of carbohydrate ligands on macrophage surfaces should be interpreted alongside the ligand–ConA binding data shown in

Table 1. Ligand L5 (GlcNAc

2-trimannoside), which exhibited the highest affinity for ConA, also demonstrated strong and selective interaction with CD206+ macrophages, as established by FTIR microscopy. This high ConA affinity matches L5’s tri-mannoside structure, indicating that the multivalent mannose presentation recognized by ConA is also efficiently engaged by CD206. In comparison, ligand L2 (cyclic mannose) displayed moderate binding to ConA and distinct, significant binding to CD206+ cells. This suggests that while ConA detects cyclic mannose, its binding profile does not fully mimic that of L5. Ligand L3, with low ConA affinity, also showed weaker binding towards macrophages, possibly reflecting a lower affinity for CD206 or interaction with alternative cell-surface receptors.

These results suggest that ConA binding can provide valuable insights into the presentation and accessibility of carbohydrate ligands (especially for mannose-containing structures like L2 and L5), yet actual in situ binding to specific macrophage receptors—such as CD206—remains the definitive measure of targeting efficacy and is strongly affected by ligand architecture (linear vs. cyclic, carbohydrate type, degree of multimerization). Therefore, the ConA assay serves as a quantitative benchmark for new ligand candidates, while FTIR microscopy uniquely enables direct mapping of receptor engagement on the surface of individual macrophages with high spatial resolution.

Uniquely, this study for the first time demonstrated the ability to visualize the spatial distribution of glycan receptors at the single-cell level via FTIR microscopy, utilizing receptor-specific ligand mapping. This technical advance opens new opportunities for the in situ mapping of immune receptors and should be highlighted in both the conclusions and abstract.

2.3. Sandwich-Like Assay System for Profiling Macrophage Subpopulations in Patient

AMs are crucial for maintaining lung homeostasis, but they also play a critical role in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory lung diseases, such as bronchiectasis. The delicate balance between the pro-inflammatory M1 and anti-inflammatory/resolving M2 macrophage phenotypes determines the course of disease progression (

Figure 4a). M0 macrophages are undifferentiated cells that can shift their function depending on cues from their environment; M1 macrophages are polarized toward a pro-inflammatory role, defending against pathogens and tumors; M2 macrophages are alternatively activated, mainly supporting anti-inflammatory processes, tissue repair, and immune regulation, with further subtypes specialized for wound healing, inflammation resolution.

In order to explore the capacity of our testing system to implement profiling and identify imbalances, we first developed a sandwich-like assay, as depicted in

Figure 4b. This assay serves as a foundation for subsequent selective reprogramming of macrophages. This assay consists of a series of five unique glycan-based ligands, L1–L5, synthesized using a branched polyethyleneimine (PEI) backbone (

Figure 1,

Table 1). Each ligand is designed with a distinct carbohydrate moiety — linear D-mannose (L1), cyclic D-mannose (L2), linear D-galactose (L3), cyclic D-galactose (L4), or a synthetic GlcNAc2-trimannoside cluster (L5) — intended to interact with specific lectin receptors on macrophages.

To assess the in situ cellular response and quantify the resulting macrophage profile, we employed a cell-based profiling assay. Alveolar macrophages (AMs) were incubated with a panel of FITC-labeled synthetic glycoligands (FITC-L1 to FITC-L5). The fluorescence intensity of bound FITC-ligands was quantified using a plate fluorometer. To enhance the diagnostic power of this "fingerprint" analysis, we incorporated competitive binding assays with Mannan. Mannan's inclusion provides additional information regarding the selectivity of our ligands, particularly their interaction with mannose-specific receptors. This quantitative binding data, derived from the interaction of our ligand panel with AM surface receptors, generates a unique binding "fingerprint" for each macrophage population.

To translate these observed binding "fingerprints" into a clinically relevant measure of macrophage polarization, we established standardized reference binding profiles for distinct macrophage subpopulations: M0 (quiescent), M1 (pro-inflammatory), and M2 (pro-resolving/tissue-repair). These reference populations were generated by ex vivo differentiation of peripheral blood monocytes, providing a well-defined and reproducible standard for comparison against the heterogeneous patient-derived samples.

We then applied a non-negative least squares (NNLS) deconvolution algorithm to the binding data obtained from patient-derived BALF samples. This algorithm deconvolved the complex experimental profiles, allowing us to determine the relative proportions of M0, M1, and M2 subpopulations within the patient samples. This quantitative deconvolution enabled us to assess the baseline macrophage phenotype in bronchiectasis patients and, subsequently, to monitor the dynamic remodeling of this profile following targeted therapeutic intervention with Dox-conjugated ligands.

2.4. Baseline Macrophage Receptor Profiling and Its Significance in Bronchiectasis

2.4.1. Establishing Baseline Macrophage Receptor Profiles in Bronchiectasis

To establish the baseline macrophage phenotype in bronchiectasis, alveolar macrophages (AMs) isolated from the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of patients were analyzed and compared against a healthy control. A panel of five distinct FITC-labeled, glycan-based ligands (L1-L5) was applied to the cells to profile their surface receptor expression. The resulting binding affinities are presented numerically in

Table 2, with the binding patterns and their statistical distributions visualized across

Figure 5.

The analysis revealed a starkly different binding profile for AMs from bronchiectasis patients compared to the healthy control, as depicted in

Figure 5 and quantified in

Table 2. Specifically, patient-derived AMs showed a pronounced binding affinity for ligands L2 (cyclic mannose) and L5 (GlcNAc2-trimannoside cluster), with binding percentages of 25% and 26%, respectively. The kernel density distributions shown in

Figure 5c further illustrate the prevalence of these specific binding events. This affinity was significantly higher than the binding observed for these same ligands in the healthy control (5% for L2 and 2% for L5,

Table 2). This imbalanced receptor profile, characterized by a strong preference for binding of the complex mannose structures, is indicative of a pathogenic, pro-inflammatory state.

To confirm the specificity of these ligand-receptor interactions, a competitive inhibition assay was performed on the patient's AMs using mannan. As shown graphically in

Figure 5b and detailed numerically in

Table 2, the presence of mannan significantly reduced the binding of L5 (from 26% to 17%) and L2 (from 25% to 21%). This result strongly suggests that ligands L2 and L5 primarily engage with mannose-specific receptors, such as the Mannose Receptor (CD206). In contrast, the binding of galactose-based ligands (L3, L4) and linear mannose (L1) was largely unaffected, confirming their interaction with different receptor types.

Furthermore, the binding profile of the ex vivo AMs from the bronchiectasis patient did not perfectly align with any of the standardized in vitro M0, M1, or M2a macrophage controls, the data for which are provided for comparison in

Table 2. This discrepancy highlights that macrophage phenotypes in a complex disease environment are more nuanced than simplified laboratory models, reinforcing the necessity of analyzing patient samples directly. The identification of this specific, imbalanced receptor profile provides a clear rationale for targeted therapeutic intervention.

2.4.2. A Targeted Modulating Macrophage Phenotypes with Doxorubicin Formulations:

Bronchiectasis is a chronic inflammatory condition that is frequently sustained by a surplus of pro-inflammatory macrophages of the M1 phenotype. Consequently, it is unmet need to develop a therapeutic approach that can specifically target and suppress these M1 cell populations.

Dox, a well-established chemotherapeutic agent, is known to possess immunomodulatory properties that can impact macrophage behavior. While its cytostatic effects on tumor cells are widely studied, a key characteristic relevant to our work is its ability to shift macrophage polarization, often promoting a transition from pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages towards an M2-like phenotype [

50,

51]. While this phenomenon may contribute to immune suppression during cancer treatment, it serves as a powerful model for investigating the impact on conditions characterized by chronic inflammation. We leverage this property to investigate the potential for targeted delivery and selective remodeling of specific macrophage subpopulations. We aimed to test the hypothesis that Dox, delivered via our glycan ligands, can reduce the pro-inflammatory M1 population, thereby addressing the macrophage imbalance that drives chronic inflammation in conditions like bronchiectasis.

To explore this, we investigated the ex vivo effects of Dox-conjugated ligands (Dox-L1 to Dox-L5) (

Figure 1) on AMs obtained from BALF of a pediatric patient with traction bronchiectasis (BALF1).

Analysis of ligand binding before and after pre-incubation with the corresponding Dox-conjugated formulations revealed significant modulatory effects on macrophage receptor engagement (

Figure 5). Pre-incubation with Dox-L5, which targets the high-affinity CD206 receptor, almost completely abolished subsequent FITC-L5 binding (a sharp decrease from 26% to 1%). This dramatic reduction strongly suggests efficient targeting, saturation, and/or internalization of CD206 by the Dox-L5 formulation, indicating successful delivery of Dox to these M2-associated receptor populations.

In contrast, pre-treatment with Dox-L3 (linear galactose), a ligand with lower intrinsic binding affinity, unexpectedly enhanced the binding of FITC-L3 (from 8% to 27%). This suggests that the Dox-L3 formulation might prime or activate the macrophages, possibly by altering membrane properties or indirectly upregulating receptor expression, thereby increasing the accessibility or affinity for other ligands. This enhancement is distinct from the receptors saturation effect and the decrease in L5 binding (from 26% to 1%) observed after pre-treatment with Dox-L5. Pre-treatment with Dox-L1 and Dox-L4 induced negligible changes. Dox-L2 showed only a minor increase in L2 binding (25% to 30%), close to the experimental error margin. These findings highlight the ligand-specific nature of Dox formulation effects on macrophage receptor availability.

These results demonstrate that our glyco-ligand platform can serve as a vehicle for targeted drug delivery, capable of inducing distinct modulatory effects on macrophage receptor expression and potentially cellular phenotype based on ligand affinity. For instance, this platform could be adapted to test the efficacy of alternative anti-inflammatory agents, such as curcumin, which is increasingly recognized for its relevance in treating chronic inflammatory conditions like bronchiectasis, thereby guiding optimal therapeutic choices.

2.6. Control Ex Vivo Polarization Remodeling by Free Doxorubicin

In order to elucidate the effects of glycan-targeted conjugates on remodeling, we conducted an assessment of the immunomodulatory influence of free Dox, serving as a control. So, we analyzed BALF samples from three pediatric patients with distinct underlying pathologies leading to chronic lung inflammation and bronchiectasis: traction bronchiectasis (BALF1), bronchiectasis secondary to primary immunodeficiency post-HSCT (BALF2), and obliterative bronchiolitis secondary to chronic aspiration (BALF3). The aim was to determine if free Dox alters macrophage polarization ex vivo and whether these effects vary depending on the patient's specific clinical context. The baseline macrophage polarization profiles and the changes following ex vivo treatment with free Dox are summarized in

Table 4.

Similar to the case of Dox in ligands, for free Dox, we observe that across samples BALF1 and BALF2, which represent typical cases of bronchiectasis and its complications, Dox treatment consistently demonstrated a pro-resolving effect. Specifically, Dox administration led to a reduction in the pro-inflammatory M1 macrophage population and a corresponding increase in anti-inflammatory/resolving M2a and M2b-c-d subsets. For instance, in BALF1, M1 decreased from 55% to 40%, while M2a increased from 18% to 29%. Similarly, BALF2 showed a marked reduction in M1 (29% to 18%) with increased M2a (32% to 43%). This trend suggests that Dox, in these contexts, tends to a shift pro-inflammatory M1 towards more regulatory M2 phenotypes. However, the effectiveness and direction of this modulation seem to be dependent on the underlying pathology and the context. For example, in the case of BAL-3, anti-inflammatory M1 increases even more.

The observed immunomodulatory effect of free Dox, specifically its tendency to reduce M1 and increase M2 populations in our ex vivo BALF system (

Table 4), warrants comparison with existing literature [

52,

53,

54,

55]. While Dox is primarily known as a cytotoxic agent, its influence on the immune system, including macrophage polarization, is a field of growing interest, albeit with context-dependent findings.

Our findings of a pro-resolving (M1-to-M2) shift align with reports in non-oncological inflammatory contexts, particularly in studies of Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. For instance, Chen et al. (2023) demonstrated that M2b macrophages can protect against Dox-induced cardiotoxicity by regulating cardiomyocyte autophagy, supporting the idea that M2 phenotypes can be part of the tissue response to Dox-induced stress [

53]. This suggests that the M1-to-M2 shift observed in our BALF samples may represent a similar endogenous reparative response promoted by the drug.

The immunomodulatory effects of Doxorubicin (Dox) are known to be highly dependent on the surrounding tissue microenvironment, dosage, and administration regimen, as indicated by studies in various contexts [

50]. In the specific inflammatory milieu of bronchiectasis BALF, observed trends suggest that free Dox may favor a pro-resolving M2 pathway, albeit with modest and non-specific effects. This contextual finding further underscores the significant potential of our glycan-targeted formulations. While free Dox shows a limited M2 trend, our Dox-conjugated ligands are engineered to achieve a superior and highly specific polarization. For example, the Dox-L5 conjugate demonstrated a potent and highly specific induction of the M2a phenotype (99%,

Table 3), highlighting its strong immunomodulatory capacity. However, such a near-complete shift toward M2a polarization exceeds the physiological balance observed in healthy controls, suggesting that while Dox-L5 effectively suppresses pro-inflammatory activity, an optimal therapeutic outcome likely requires a more balanced M0/M2 composition resembling that of the healthy lung. This finding underscores both the strength and the specificity of the conjugate’s action, far surpassing the effects of the free drug.

2.7. Efficacy of Targeted vs. Non-Targeted Macrophage Remodeling

The therapeutic superiority of glycan-targeted delivery over the administration of free Dox is demonstrated by a more profound and beneficial remodeling of the macrophage population (

Table 6). While free Dox provided a modest reduction in the M1 phenotype, the Dox-ligand conjugates achieved a more potent M1 suppression. Critically, only the targeted conjugates were able to induce the re-emergence of a quiescent, M0-like macrophage population, a key indicator of a return toward a healthy, non-inflammatory state. This suggests that targeted delivery not only enhances the drug's efficacy but fundamentally alters its immunomodulatory action, enabling a more complete restoration of immune homeostasis.

The structural characteristics of the glycan ligands were pivotal in determining therapeutic success. Ligands designed to engage the Mannose Receptor (CD206)—particularly those with multivalent or conformationally constrained structures like Dox-L5 and Dox-L2—were most effective, confirming CD206 as a key therapeutic target on pathogenic M1 macrophages. Unexpectedly, the cyclic galactose conjugate (Dox-L4) also showed high efficacy, suggesting that its cyclic structure allows it to mimic mannose and engage CD206. This "structural mimicry" reveals a novel targeting strategy, indicating that conformational design is as important as the type of saccharide used.

2.8. CLSM and Fluorescence Microscopy Analysis of Glycoligand-Conjugate Uptake in BALF-Derived Alveolar Macrophages

2.8.1. Fluorescence Microscopy Screening Analysis

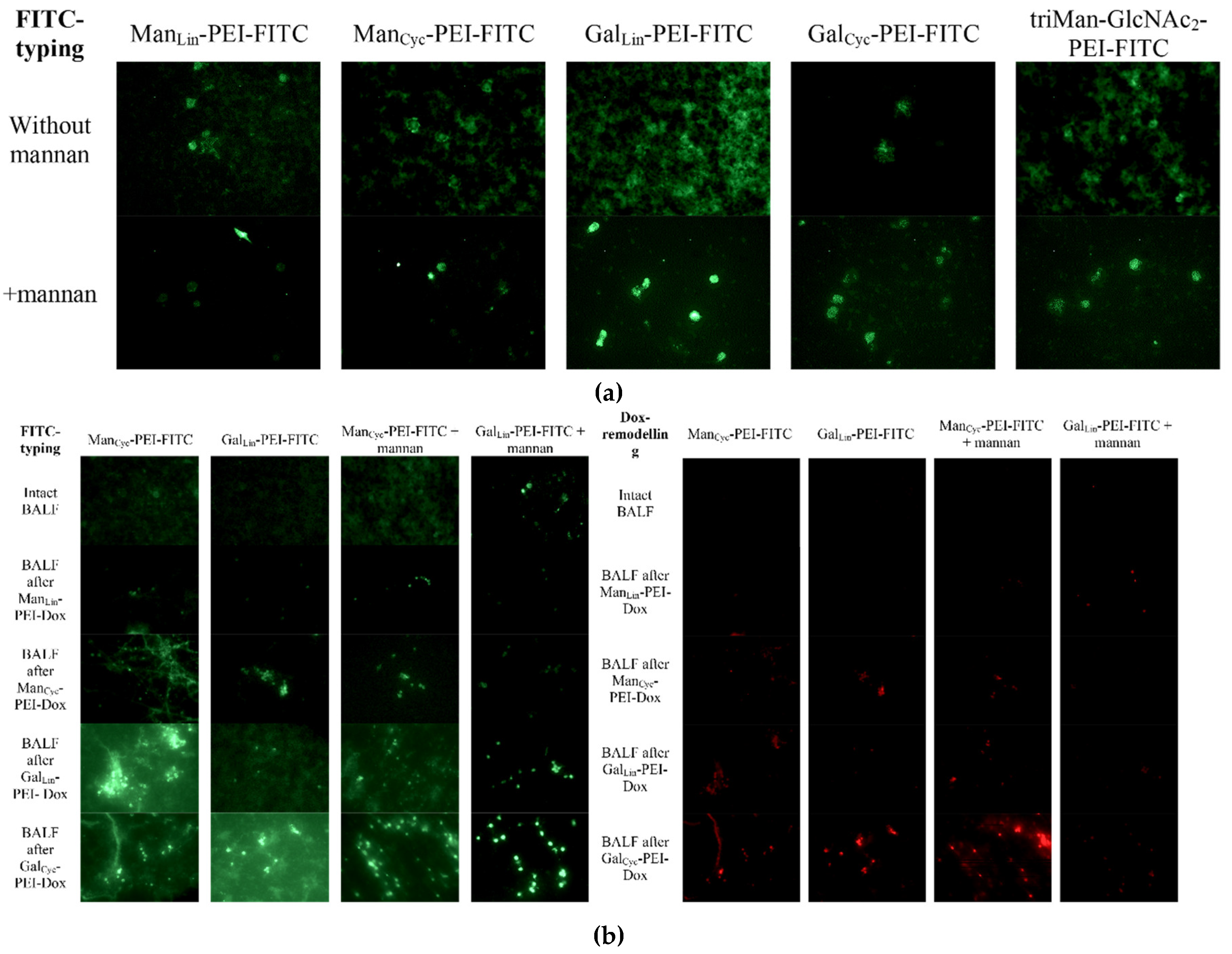

Following our quantitative analysis of binding profiles and Doxorubicin's reprogramming effects, we employed fluorescence microscopy to directly visualize ligand selectivity and assess Dox cellular uptake by BALF-derived alveolar macrophages. This approach aimed to confirm whether the glycan ligands enable selective targeting and deliver Dox effectively, thereby influencing macrophage reprogramming.

Fluorescence microscopy screening analysis was conducted to visually verify the targeted delivery of Dox to alveolar macrophages and its reprogramming. Analysis of BALF from a patient with bronchiectasis revealed distinct, non-overlapping cell populations defined by their specific carbohydrate-binding profiles. The cyclic mannose conjugate (Man

Cyc-PEI-FITC) exhibited the highest binding efficiency, with an estimated cellular fluorescence intensity 3-5 times greater than its linear analog (Man

Lin-PEI-FITC) on a predominant population of large, distinct cells. This superior binding resulted in an excellent signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio, indicative of selective detection. Quantitative flow cytometry data (Zlotnikov et al. [

56]) confirms that mannose-binding cells constitute approximately 50–70% of the total BALF cells visualized, consistent with alveolar macrophages. In contrast, galactose-binding cells, represented a smaller but clearly distinct subset. Competitive inhibition with mannan (

Figure 7a, bottom panel) unequivocally validated the specificity of mannose-based ligand binding, completely abrogating fluorescence from Man

Cyc, Man

Lin, and triMan ligands. The specificity of this binding was also confirmed through competition assays; the addition of excess free mannan completely abrogated the binding of all mannose-based ligands (Man

Cyc, Man

Lin, triMan) but had no inhibitory effect on the binding of the galactose-based ligands. This strongly indicates the presence of at least two distinct lectin-mediated recognition systems: a mannose-dependent pathway, characteristic of the Mannose Receptor (CD206) on alveolar macrophages, and a mannose-independent, galactose-dependent pathway, likely mediated by galectins on

Our objective in this phase was to directly visualize the selective binding of our glycan ligands to specific BALF cell populations and to confirm that Dox, when conjugated to these ligands, could be effectively delivered to target cells for macrophage reprogramming (

Figure 7b). The sequential remodeling and displacement assay provided definitive visual evidence of targeted drug delivery and its impact on receptor availability.

Pre-incubation with ManCyc-PEI-Dox selectively labeled the macrophage-like population with Doxorubicin (red channel). Crucially, this Dox-conjugated ligand blocked subsequent binding of the imaging ManCyc-PEI-FITC ligand (green channel) to these same cells. Importantly, this mannose-mediated blocking did not interfere with the binding of the galactose ligand (GalLin-PEI-FITC) to its distinct target population.

Conversely, pre-treatment with GalLin-PEI-Dox intensely labeled granulocytic cells (red channel) and completely prevented subsequent binding of the imaging ligand. This galactose-mediated 'block' showed no cross-reactivity, leaving the ManCyc-FITC binding to macrophages entirely intact (green channel).

Thus, these fluorescence microscopy results provide definitive evidence for at least two mutually exclusive cellular targets within the pathological BALF sample. The Man ligand demonstrates high fidelity for the alveolar macrophage population, interacting via the Mannose Receptor. The Gal ligand selectively targets a separate population of galectin-expressing cells, Macrophage galactose lectin (MGL, CD301).

2.8.2. Mechanistic Validation: Bridging Quantitative Data and Visual Evidence

To confirm that our quantitative data obtained by deconvolution (

Table 3) accurately reflect biological processes, we used fluorescence microscopy (

Figure 7). These images allowed us to visually demonstrate how the ligand recognition system works in practice. First, we confirmed that our mannose-containing ligands (ManCyc, triMan), which are the basis of therapeutic conjugates, selectively bind to a specific population of alveolar macrophages (

Figure 7a). We have shown that this binding is specific to the mannose-dependent pathway (i.e., the CD206 receptor), which was confirmed by competitive inhibition by free mannan, and that it does not affect galactose binding receptors (MGL, CD301). This high specificity proves that the deconvolution data truly reflect the state of macrophages. Secondly, the sequential displacement experiment (

Figure 7b) provided definitive evidence of targeted drug delivery. He showed that therapeutic conjugates with doxorubicin (for example, ManCyc-PEI-Dox) occupy precisely those specific macrophage receptors. This targeted delivery, visualized by the red fluorescence of doxorubicin, which "blocks" the green fluorescence of the diagnostic FITC ligand, is a key mechanistic link. It confirms that the powerful immunomodulatory shifts observed during deconvolution (for example, achieving 99% of the M2a profile under the action of Dox-L5) are a direct result of specific receptor-mediated delivery of doxorubicin to alveolar macrophages.

2.8.3. CLSM Fine Features of BALF Cells Profiles

Subsequent to quantitative analysis of ligand binding across the entire BALF cell population, Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) was employed to provide critical spatial and morphological context (

Figure 8). CLSM enables the identification of specific cell subsets (e.g., AMs vs. neutrophils) binding the glycan ligands, the determination of subcellular localization (surface binding vs. internalization), and the assessment of co-localization between profiling and therapeutic ligands. For this, a dual-fluorescence strategy was utilized, employing the profiling ligand L2-FITC (cyclic mannose, green channel) to identify all cells expressing receptors for simple mannose, and therapeutic ligands (L4-Dox, L2-Dox, or L5-Dox, red channel) to assess targeted drug delivery.

CLSM of the BALF cells revealed a morphologically heterogeneous population. This comprised large, adherent cells, identified as mature AMs, alongside a distinct population of smaller, non-adherent cells. Based on our previous immunological studies, these smaller cells are not neutrophils but are instead classified as immature, actively secreting macrophages, which stand in functional contrast to their larger, phagocytic counterparts [

40,

56]. This distinction is critical for interpreting the ligand binding patterns.

The different macrophage subpopulations exhibited distinct receptor profiles. The large, mature AMs, consistent with a pro-inflammatory state, showed a strong binding preference for mannose-based ligands (L2 and L5), which primarily target the Mannose Receptor (CD206). In contrast, and in line with our prior flow cytometry data, the smaller, secreting macrophage population showed significant binding with galactose-based ligands [

40,

56]. This strongly indicates the expression of the Macrophage Galactose Lectin (MGL/CD301), a key surface marker for this immature macrophage subset. This differential expression—CD206 on mature inflammatory AMs and MGL on immature secreting macrophages—paints a more complex picture of the lung's cellular landscape in bronchiectasis and underscores the need for multi-receptor targeting strategies.

When BALF cells were sequentially incubated with L4-Dox (cyclic galactose) and L2-FITC (cyclic mannose), both the green (L2-FITC) and red (L4-Dox) signals were exclusively restricted to the N/M cell population. Significant co-localization (yellow/orange) was observed within these smaller cells. This observation, confirmed in a control experiment using L2-Dox and L2-FITC, indicates that L2 (cyclic mannose) and L4 (cyclic galactose) ligands primarily target the N/M subset. These findings align with our hypothesis that monomannose ligands interact with receptors more highly expressed on neutrophils/monocytes, and not on the AMs from this patient.

To test the hypothesis that oligomannose might preferentially target AMs, we utilized L5-Dox (trimannoside conjugate) alongside L2-FITC (cyclic mannose). Consistent with previous observations, the L2-FITC signal remained restricted to the N/M cells, leaving the large AM clusters unlabeled by L2-FITC. In stark contrast, an intense red signal from L5-Dox was observed, perfectly co-localizing with the AM clusters. This signal exhibited a punctate intracellular pattern, indicative of successful receptor-mediated endocytosis and internalization of the L5-Dox conjugate into the AMs.

CLSM analysis definitively segregates the BALF cells into two distinct populations based on their glycan receptor profiles:

Alveolar Macrophages. These cells exhibit poor binding or lack of functional receptors for simple mannose (L2) and galactose (L4) ligands. However, they specifically internalize the complex trimannoside structure (L5), likely via mannose receptors (e.g., CD206/CD209) which are known to bind multivalent mannose structures with high affinity.

Neutrophils/Monocytes (N/M). These cells actively bind simple monomannose (L2) and potentially galactose (L4) ligands, suggesting expression of distinct lectins (e.g., other mannose-binding proteins, galectins).

This differential targeting has direct therapeutic implications. For targeted drug delivery to AMs in bronchiectasis, vectors based on simple mannose (L2) or simple galactose (L4) ligands are ineffective and would lead to off-target delivery to granulocytes/monocytes. In contrast, the L5 (trimannoside) ligand serves as a highly specific and efficient vector for selectively delivering therapeutic cargo, such as Doxorubicin, into alveolar macrophages. This targeted approach is crucial for potentially modulating the imbalanced macrophage phenotype implicated in chronic lung inflammation.

4. Conclusions

The finely orchestrated equilibrium among alveolar macrophage (AM) phenotypes—M0, M1, and M2—is pivotal in governing inflammatory trajectories and dictating disease outcomes. In persistent inflammatory pathologies such as bronchiectasis, a dysregulated macrophage (Mf) profile, typified by a preponderance of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages, serves as a cardinal indicator of disease progression and amplifies the risk of adverse clinical sequelae.

Our team has pioneered a sophisticated platform leveraging precisely engineered glyco-ligands conjugated to Doxorubicin (Dox) for highly targeted immunomodulation. This integrated system not only facilitates sensitive phenotypic profiling of Mf subpopulations but, more critically, enables precise therapeutic intervention to recalibrate a healthy Mf balance. Our investigations unequivocally demonstrate that dysregulated Mf profiles are amenable to therapeutic re-shaping through selective engagement of specific glycan receptors.

Employing Dox as a benchmark therapeutic agent, we rigorously validated the efficacy of our targeted strategy. We observed that these conjugates, by judiciously exploiting specific glycan-ligand interactions, robustly altered Mf polarization dynamics. Notably, Dox conjugates engineered to target the Mannose Receptor (MR, CD206/CD209) via a high-affinity trimannoside structure (Dox-L5) achieved profound therapeutic success. In a preclinical bronchiectasis model, this specific formulation proficiently attenuated the pathogenic M1 population from a dysregulated 55% to a substantially reduced 15%, with instances even demonstrating complete eradication (0%) of M1 cells. This targeted reprogramming was concurrently marked by an induction of M0-like cells and a decisive phenotypic shift towards the reparative M2 anti-inflammatory phenotype, thereby fostering the resolution of inflammation.

The efficacy of Mf reprogramming is demonstrably contingent upon precise glycan architecture. Our empirical data emphasize the paramount importance of multivalency (exemplified by L5) and conformational constraint (as elucidated by cyclic ligands L2 and L4) for optimal MR engagement and subsequent cellular remodeling. Beyond this, we unveiled intriguing structural cross-reactivity: a cyclic galactose ligand, despite its limited affinity for the MR, was effectively recognized by galectin-expressing cells. This finding underscores the profound potential for tailoring ligand design to selectively address distinct immune cell subsets, thereby establishing a novel principle for engineering selective vectors targeting both C-type lectin receptors and galectins.

Our sophisticated platform thus presents a compelling paradigm for the development of precision immunomodulatory therapies. By transcending conventional systemic immunosuppression in favor of targeted reprogramming of the innate immune system, this approach holds transformative potential for managing chronic, destructive inflammatory diseases, steering them from states of persistent inflammation towards efficacious resolution and tissue repair. This work constitutes a significant advancement in translating intricate glycan-based biological concepts into clinically relevant, targeted therapeutic strategies. Furthermore, the inherent capabilities of our system extend to its application as a powerful diagnostic tool for evaluating the efficacy of novel pharmaceutical agents.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1. FTIR spectra of fluorescent markers with different affinity to CD206 macrophage receptors X-PEI-FITC. PBS (0.01 M, pH 7.4). T = 37 °C. Figure S2. (a) 1H NMR spectra of triMan-(GlcNAc)2. D2O. T = 22 °C. (b) 1H NMR spectra of triMan-(GlcNAc)2-PEI as a polymer for fluorescent markers. D2O. T = 22 °C.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.V.K., I.D.Z.; methodology, I.D.Z.and E.V.K.; formal analysis, I.D.Z., A.A.E.; investigation, I.D.Z., A.A.E. and E.V.K.; data curation, I.D.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, I.D.Z.; writing—review and editing, E.V.K.; project supervision, E.V.K.; funding acquisition, E.V.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Cell lines were obtained from Lomonosov Moscow State University Depository of Live Systems Collection (Moscow, Russia).

Informed Consent Statement

BALF samples were obtained from the Morozovskaya Children’s City Clinical Hospital following patient consent and strict adherence to ethical guidelines (approved by the Local Ethics Committee, Protocol #2024-15A).

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

This work was performed using the following equipment from the program for the development of Moscow State University: the MICRAN-3 FTIR microscope, Jasco J-815 CD spectrometer, NTEGRA II AFM microscope, Olympus FluoView FV1000 confocal laser scanning microscope and Olympus IX81 motorized inverted microscope.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMs |

Alveolar macrophages |

| BAL |

Bronchoalveolar lavage |

| BALF |

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid |

| CLSM |

Confocal laser scanning microscopy |

| FTIR |

Fourier-transformed infrared spectroscopy |

| Mf or Mφ |

Macrophages |

References

- Alizadeh, D.; Zhang, L.; Hwang, J.; Schluep, T.; Badie, B. Tumor-Associated Macrophages Are Predominant Carriers of Cyclodextrin-Based Nanoparticles into Gliomas. Nanomedicine Nanotechnology, Biol. Med. 2010, 6, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savchenko, I.V.; Zlotnikov, I.D.; Kudryashova, E.V. Biomimetic Systems Involving Macrophages and Their Potential for Targeted Drug Delivery. Biomimetics 2023, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepekha, L.N.; Erokhina, M.V. Pulmonary Macrophages and Dendritic Cells. Respir. Med. Man. 4 Vol. 3rd Ed., Add. Revis. Vol. 1. 2024, 249–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C.D. Anatomy of a Discovery: M1 and M2 Macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papachristoforou, E.; Ramachandran, P. Macrophages as Key Regulators of Liver Health and Disease. In; 2022; pp. 143–212.

- Peng, Y.; Zhou, M.; Yang, H.; Qu, R.; Qiu, Y.; Hao, J.; Bi, H.; Guo, D. Regulatory Mechanism of M1/M2 Macrophage Polarization in the Development of Autoimmune Diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2023, 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.H.; Lee, H.; Park, C.; Hong, S.H.; Hong, S.H.; Kim, G.Y.; Cha, H.J.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.S.; Hwang, H.J.; et al. Glutathione Induced Immune-Stimulatory Activity by Promoting M1-like Macrophages Polarization via Potential ROS Scavenging Capacity. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Huang, Q.; Peng, C.; Yao, L.; Chen, H.; Qiu, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. Exosomes from M1-Polarized Macrophages Enhance Paclitaxel Antitumor Activity by Activating Macrophages-Mediated Inflammation. Theranostics 2019, 9, 1714–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italiani, P.; Boraschi, D. From Monocytes to M1/M2 Macrophages: Phenotypical vs. Functional Differentiation. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutolo, M.; Campitiello, R.; Gotelli, E.; Soldano, S. The Role of M1/M2 Macrophage Polarization in Rheumatoid Arthritis Synovitis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strizova, Z.; Benesova, I.; Bartolini, R.; Novysedlak, R.; Cecrdlova, E.; Foley, L.K.; Striz, I. M1/M2 Macrophages and Their Overlaps - Myth or Reality? Clin. Sci. 2023, 137, 1067–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, S.; Dang, X.; Lin, L.; Ren, L.; Song, R. GPNMB Plays an Active Role in the M1/M2 Balance. Tissue Cell 2022, 74, 101683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, D.; Kim, M.R.; Jeong, H.; Jeong, H.C.; Jeong, M.H.; Yoon, S.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Ahn, Y. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Reciprocally Regulate the M1 / M2 Balance in Mouse Bone Marrow-Derived Macrophages. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2014, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, C.D.; Drouet, C. Modulators of the Balance between M1 and M2 Macrophages during Pregnancy. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikonova, A.A.; Ataullakhanov, R.I.; Khaitov, R.M.; Khaitov, M.R. Antiviral Activity of Different Types of Human Macrophages. Immunologiya 2016, 37, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.; Ma, Y.; Yang, C.; Li, L. Plasticity of Monocytes/Macrophages: Phenotypic Changes during Disease Progression. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- St-Laurent, J.; Turmel, V.; Boulet, L.P.; Bissonnette, E. Alveolar Macrophage Subpopulations in Bronchoalveolar Lavage and Induced Sputum of Asthmatic and Control Subjects. J. Asthma 2009, 46, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, N.; Xu, W. Mannan-Modified Solid Lipid Nanoparticles for Targeted Gene Delivery to Alveolar Macrophages. Pharm. Res. 2010, 27, 1584–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, D.; Li, T.E.; Li, J.H.; Xiao, Z.T.; Chen, M.; Yang, X.; Jia, H.L.; Dong, Q.Z.; et al. IFN-a Facilitates the Effect of Sorafenib via Shifting the M2-like Polarization of TAM in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2021, 13, 301–313. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, L.; Liang, G.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, R.; Chen, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, H.; Yang, B.; He, Q. Metformin Prevents Cancer Metastasis by Inhibiting M2-like Polarization of Tumor Associated Macrophages. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 36441–36455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Marchesi, F.; Malesci, A.; Laghi, L.; Allavena, P. Tumour-Associated Macrophages as Treatment Targets in Oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 14, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brancewicz, J.; Wójcik, N.; Sarnowska, Z.; Robak, J.; Król, M. The Multifaceted Role of Macrophages in Biology and Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashyap, B.K.; Singh, V.V.; Solanki, M.K.; Kumar, A.; Ruokolainen, J.; Kesari, K.K. Smart Nanomaterials in Cancer Theranostics: Challenges and Opportunities. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 14290–14320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullman, N.A.; Burchard, P.R.; Dunne, R.F.; Linehan, D.C. Immunologic Strategies in Pancreatic Cancer: Making Cold Tumors Hot. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 2789–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Liu, H.; Xue, Y.; Lin, J.; Fu, Y.; Xia, Z.; Pan, D.; Zhang, J.; Qiao, K.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Reversing Cold Tumors to Hot: An Immunoadjuvant-Functionalized Metal-Organic Framework for Multimodal Imaging-Guided Synergistic Photo-Immunotherapy. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslzad, S.; Heydari, P.; Abdolahinia, E.D.; Amiryaghoubi, N.; Safary, A.; Fathi, M.; Erfan-Niya, H. Chitosan/Gelatin Hybrid Nanogel Containing Doxorubicin as Enzyme-Responsive Drug Delivery System for Breast Cancer Treatment. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2023, 301, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukyanov, A.N.; Elbayoumi, T.A.; Chakilam, A.R.; Torchilin, V.P. Tumor-Targeted Liposomes: Doxorubicin-Loaded Long-Circulating Liposomes Modified with Anti-Cancer Antibody. J. Control. Release 2004, 100, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, C.; Santos, R.; Cardoso, S.; Correia, S.; Oliveira, P.; Santos, M.; Moreira, P. Doxorubicin: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly Effect. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 3267–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Liao, A.T.; Wang, S.L. Article L-Asparaginase, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, and Prednisolone (Lhop) Chemotherapy as a First-Line Treatment for Dogs with Multicentric Lymphoma. Animals 2021, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sritharan, S.; Sivalingam, N. A Comprehensive Review on Time-Tested Anticancer Drug Doxorubicin. Life Sci. 2021, 278, 119527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyfman, P.A.; Malsin, E.S.; Khuder, B.; Joshi, N.; Gadhvi, G.; Flozak, A.S.; Carns, M.A.; Aren, K.; Goldberg, I.A.; Kim, S.; et al. A Novel MIP-1–Expressing Macrophage Subtype in BAL Fluid from Healthy Volunteers. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2023, 68, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, J.L.; Weber, J.M.; Kelly, F.L.; Neely, M.L.; Mulder, H.; Frankel, C.W.; Nagler, A.; McCrae, C.; Newbold, P.; Kreindler, J.; et al. BAL Fluid Eosinophilia Associates With Chronic Lung Allograft Dysfunction Risk: A Multicenter Study. Chest 2023, 164, 670–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Arisi, I.; Puxeddu, E.; Mramba, L.K.; Amicosante, M.; Swaisgood, C.M.; Pallante, M.; Brantly, M.L.; Sköld, C.M.; Saltini, C. Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL) Cells in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Express a Complex pro-Inflammatory, pro-Repair, Angiogenic Activation Pattern, Likely Associated with Macrophage Iron Accumulation. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0194803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Alessandro, M.; Carleo, A.; Cameli, P.; Bergantini, L.; Perrone, A.; Vietri, L.; Lanzarone, N.; Vagaggini, C.; Sestini, P.; Bargagli, E. BAL Biomarkers’ Panel for Differential Diagnosis of Interstitial Lung Diseases. Clin. Exp. Med. 2020, 20, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.A.; Cuttica, M.J.; Malsin, E.S.; Argento, A.C.; Wunderink, R.G.; Smith, S.B. Comparing Nasopharyngeal and BAL SARS-CoV-2 Assays in Respiratory Failure. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 203, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratke, K.; Weise, M.; Stoll, P.; Virchow, J.C.; Lommatzsch, M. Flow Cytometry as an Alternative to Microscopy for the Differentiation of BAL Fluid Leukocytes. Chest 2024, 166, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Kudryashova, E.V. Polymeric Infrared and Fluorescent Probes to Assess Macrophage Diversity in Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid of Asthma and Other Pulmonary Disease Patients. Polymers (Basel). 2024, 16, 3427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Kolganova, N.I.; Gitinov, S.A.; Ovsyannikov, D.Y.; Kudryashova, E.V. The Role of CD68+ Cells in Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid for the Diagnosis of Respiratory Diseases. Immuno 2025, 5, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurynina, A.V.; Erokhina, M.V.; Makarevich, O.A.; Sysoeva, V.Y.; Lepekha, L.N.; Kuznetsov, S.A.; Onishchenko, G.E. Plasticity of Human THP–1 Cell Phagocytic Activity during Macrophagic Differentiation. Biochem. 2018, 83, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Vigovskiy, M.A.; Davydova, M.P.; Danilov, M.R.; Dyachkova, U.D.; Grigorieva, O.A.; Kudryashova, E.V. Mannosylated Systems for Targeted Delivery of Antibacterial Drugs to Activated Macrophages. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Kudryashova, E.V. Mannose Receptors of Alveolar Macrophages as a Target for the Addressed Delivery of Medicines to the Lungs. Russ. J. Bioorganic Chem. 2022, 48, 46–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepenies, B.; Lee, J.; Sonkaria, S. Targeting C-Type Lectin Receptors with Multivalent Carbohydrate Ligands. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 1271–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- East, L.; Isacke, C.M. The Mannose Receptor Family. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Gen. Subj. 2002, 1572, 364–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Ezhov, A.A.; Kolganova, N.I.; Ovsyannikov, D.Y.; Belogurova, N.G.; Kudryashova, E.V. Optical Methods for Determining the Phagocytic Activity Profile of CD206-Positive Macrophages Extracted from Bronchoalveolar Lavage by Specific Mannosylated Polymeric Ligands. Polymers (Basel). 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.; Hong, J.Y.; Lei, J.; Chen, Q.; Bentley, J.K.; Hershenson, M.B. Rhinovirus Infection Induces Interleukin-13 Production from CD11b-Positive, M2-Polarized Exudative Macrophages. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2015, 52, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.Y.; Chung, Y.; Steenrod, J.; Chen, Q.; Lei, J.; Comstock, A.T.; Goldsmith, A.M.; Bentley, J.K.; Sajjan, U.S.; Hershenson, M.B. Macrophage Activation State Determines the Response to Rhinovirus Infection in a Mouse Model of Allergic Asthma. Respir. Res. 2014, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, P.J. Macrophage Polarization. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physiol-022516-034339. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, F.O.; Gordon, S. The M1 and M2 Paradigm of Macrophage Activation: Time for Reassessment. F1000Prime Reports 2014, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Zhao, F.; Cheng, H.; Su, M.; Wang, Y. Macrophage Polarization: An Important Role in in Fl Ammatory Diseases. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.; Qian, B.; Rowan, C.; Muthana, M.; Keklikoglou, I.; Olson, O.C.; Tazzyman, S.; Danson, S.; Addison, C.; Clemons, M.; et al. Perivascular M2 Macrophages Stimulate Tumor Relapse after Chemotherapy. Cancer Res 2015, 75, 3479–3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakasone, E.S.; Askautrud, H.A.; Kees, T.; Park, J.H.; Plaks, V.; Ewald, A.J.; Fein, M.; Rasch, M.G.; Tan, Y.X.; Qiu, J.; et al. Imaging Tumor-Stroma Interactions during Chemotherapy Reveals Contributions of the Microenvironment to Resistance. Cancer Cell 2012, 21, 488–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Géraldine Genard, S.L. and C.M. Reprogramming of Tumor- Associated Macrophages with Anticancer Therapies: Radiotherapy versus Chemo- and Immunotherapies. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8. [CrossRef]

- Sida, C.; Huang, Y.; Huang, S.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, K.; Pan, J. M2b Macrophages Protect against Doxorubicin Induced Cardiotoxicity via Alternating Autophagy in Cardiomyocytes. 2023, 1–13. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Li, H.; Zhu, H.; Liu, T. Docetaxel - Loaded M1 Macrophage - Derived Exosomes for a Safe and Efficient Chemoimmunotherapy of Breast Cancer. J. Nanobiotechnology 2022, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millrud, C.R.; Mehmeti, M.; Leandersson, K. Docetaxel Promotes the Generation of Anti-Tumorigenic Human Macrophages. Exp. Cell Res. 2017, 362, 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Ezhov, A.A.; Petrov, R.A.; Vigovskiy, M.A.; Grigorieva, O.A.; Belogurova, N.G.; Kudryashova, E.V. Mannosylated Polymeric Ligands for Targeted Delivery of Antibacterials and Their Adjuvants to Macrophages for the Enhancement of the Drug Efficiency. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

The scheme of synthesis of a series of macrophage phenotype profiling (FITC) ligands and a series of macrophage remodeling (Dox) ligands.

Figure 1.

The scheme of synthesis of a series of macrophage phenotype profiling (FITC) ligands and a series of macrophage remodeling (Dox) ligands.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of the dried films from the PBS buffer solution of initial components — doxorubicin (Dox) and polyethylenimine (PEI), as well as the target conjugates L1–L5 with Dox. The region between 2750 and 1800 cm–1 has been excised, as there are no peaks of analytical significance in this range.

Figure 2.

FTIR spectra of the dried films from the PBS buffer solution of initial components — doxorubicin (Dox) and polyethylenimine (PEI), as well as the target conjugates L1–L5 with Dox. The region between 2750 and 1800 cm–1 has been excised, as there are no peaks of analytical significance in this range.

Figure 3.

FTIR microscopy-based analysis of glycan ligand selectivity for CD206+ macrophages derived from BALF obtained from a patient with bronchiectasis. (a) Integrated IR signal intensity maps (I1650 × I1000) representing the combined signal from the carbohydrate moiety and the PEI backbone, for the indicated ligands: PEI-Man (L2, cyclic mannose), PEI-Gal (L3, linear galactose), and PEI-triMan (L5, GlcNAc2-trimannoside cluster). These signals reflect the binding of the ligands to BALF cells, with higher intensities indicating greater ligand-receptor engagement, particularly with CD206-expressing macrophages. (b) Intensity distribution histograms derived from the corresponding IR maps in (a). Peaks in the intensity maps correspond to individual BALF cells. Imaging was performed using FRIR microscopy with a 5 µm scanning step.

Figure 3.

FTIR microscopy-based analysis of glycan ligand selectivity for CD206+ macrophages derived from BALF obtained from a patient with bronchiectasis. (a) Integrated IR signal intensity maps (I1650 × I1000) representing the combined signal from the carbohydrate moiety and the PEI backbone, for the indicated ligands: PEI-Man (L2, cyclic mannose), PEI-Gal (L3, linear galactose), and PEI-triMan (L5, GlcNAc2-trimannoside cluster). These signals reflect the binding of the ligands to BALF cells, with higher intensities indicating greater ligand-receptor engagement, particularly with CD206-expressing macrophages. (b) Intensity distribution histograms derived from the corresponding IR maps in (a). Peaks in the intensity maps correspond to individual BALF cells. Imaging was performed using FRIR microscopy with a 5 µm scanning step.

Figure 4.

(a) Macrophage Polarization: M0, M1, and M2 Subtypes Overview. Adapted from works [

47,

48,

49]. (b) A scheme for isolating macrophages from BALF, remodeling oligosaccharide-PEI-Dox (L1-L5 with Dox), and profiling them with FITC-labeled L1-L5 ligands.

Figure 4.

(a) Macrophage Polarization: M0, M1, and M2 Subtypes Overview. Adapted from works [

47,

48,

49]. (b) A scheme for isolating macrophages from BALF, remodeling oligosaccharide-PEI-Dox (L1-L5 with Dox), and profiling them with FITC-labeled L1-L5 ligands.

Figure 5.

Binding data, expressed as a percentage in the range from 0 to 100, (a) for ligands 1-5 in the absence (L1–L5) and (b) in the presence of mannan (ML1–ML5), respectively, for macrophage cells derived from BALF obtained from a patient with bronchiectasis – before and after administration five targeted Dox drugs. Similar data on the binding of reference lines of monocytes M0, macrophages M1 and M2 are also shown. The experimental error did not exceed 10%. (c) Kernel smooth distributions of binding parameters of ligands 1-5 (L1-L5) and their presence of mannan (ML1-ML5) with BALF cells before and after exposure to 5 targeted Dox formulations.

Figure 5.

Binding data, expressed as a percentage in the range from 0 to 100, (a) for ligands 1-5 in the absence (L1–L5) and (b) in the presence of mannan (ML1–ML5), respectively, for macrophage cells derived from BALF obtained from a patient with bronchiectasis – before and after administration five targeted Dox drugs. Similar data on the binding of reference lines of monocytes M0, macrophages M1 and M2 are also shown. The experimental error did not exceed 10%. (c) Kernel smooth distributions of binding parameters of ligands 1-5 (L1-L5) and their presence of mannan (ML1-ML5) with BALF cells before and after exposure to 5 targeted Dox formulations.

Figure 6.

Examples of deconvolution of binding data profiles of macrophage cells derived from BALF obtained from a patient with bronchiectasis, on reference profiles of monocyte lines M0, macrophage M1, and M2: (a) Deconvolution of the profile of intact BALF; (b) Deconvolution of BALF profile after administration of the remodeling Dox-L1 ligand. (с) Deconvolution of BALF profile after administration of the remodeling Dox-L5 ligand. (d) Example of deconvolution of binding data profiles of macrophage cells derived from BALF obtained from a healthy donor, on reference profiles of monocyte lines M0, macrophage M1, and M2.

Figure 6.

Examples of deconvolution of binding data profiles of macrophage cells derived from BALF obtained from a patient with bronchiectasis, on reference profiles of monocyte lines M0, macrophage M1, and M2: (a) Deconvolution of the profile of intact BALF; (b) Deconvolution of BALF profile after administration of the remodeling Dox-L1 ligand. (с) Deconvolution of BALF profile after administration of the remodeling Dox-L5 ligand. (d) Example of deconvolution of binding data profiles of macrophage cells derived from BALF obtained from a healthy donor, on reference profiles of monocyte lines M0, macrophage M1, and M2.

Figure 7.

(a) Profiles of carbohydrate ligand binding to BALF cells. Fluorescence microscopy images demonstrating the specific binding of five different FITC-labeled carbohydrate ligands to cells isolated from the BAL of a patient with bronchiectasis. The top panel ("Without mannan") shows the basic ligand binding. The bottom panel ("+ mannan") demonstrates the effect of competitive inhibition by soluble mannan on ligand binding. (b) The specificity and effectiveness of targeting ligands conjugated with doxorubicin on BAL cells. Fluorescence microscopy images illustrating an experiment on sequential modification and diagnostic profiling of BAL cells in bronchiectasis. The left block ("FITC typing", green channel) shows fluorescence from FITC-labeled diagnostic ligands. The right block ("Dox remodeling", red channel) shows fluorescence from therapeutic ligands conjugated with doxorubicin. The first line ("Intact BALFE") serves as a control. The following lines demonstrate the specific blocking of the binding of the FITC ligand after pretreatment with the corresponding Dox conjugated ligand. The width of the micrographs is 100 microns.

Figure 7.

(a) Profiles of carbohydrate ligand binding to BALF cells. Fluorescence microscopy images demonstrating the specific binding of five different FITC-labeled carbohydrate ligands to cells isolated from the BAL of a patient with bronchiectasis. The top panel ("Without mannan") shows the basic ligand binding. The bottom panel ("+ mannan") demonstrates the effect of competitive inhibition by soluble mannan on ligand binding. (b) The specificity and effectiveness of targeting ligands conjugated with doxorubicin on BAL cells. Fluorescence microscopy images illustrating an experiment on sequential modification and diagnostic profiling of BAL cells in bronchiectasis. The left block ("FITC typing", green channel) shows fluorescence from FITC-labeled diagnostic ligands. The right block ("Dox remodeling", red channel) shows fluorescence from therapeutic ligands conjugated with doxorubicin. The first line ("Intact BALFE") serves as a control. The following lines demonstrate the specific blocking of the binding of the FITC ligand after pretreatment with the corresponding Dox conjugated ligand. The width of the micrographs is 100 microns.

Figure 8.

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) analysis of glycan ligand binding and doxorubicin delivery to alveolar macrophages from bronchiectasis patients. Representative CLSM images are presented for alveolar macrophages (Mf) derived from BALF. Cells were treated with Dox-conjugated glycan ligands: (a) L4-Dox (cyclic galactose -PEI-Dox); (b) L2-Dox (cyclic mannose -PEI-Dox); (c) L5-Dox (trimannoside-PEI-Dox). FITC-labeled ligands used for tracking: L2-FITC. Images display 4 imaging modalities: (1) FITC fluorescence (green, excitation: 488 nm, emission: 505-535 nm) indicating the distribution of the profiling glycan ligand; (2) Doxorubicin fluorescence (red, excitation: 515 nm, emission: 575-675 nm) indicating the intracellular localization of the delivered drug; (3) Brightfield microscopy for cellular morphology; and (4) A merged overlay of all channels to assess co-localization. Scale bar represents 50 µm.

Figure 8.

Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) analysis of glycan ligand binding and doxorubicin delivery to alveolar macrophages from bronchiectasis patients. Representative CLSM images are presented for alveolar macrophages (Mf) derived from BALF. Cells were treated with Dox-conjugated glycan ligands: (a) L4-Dox (cyclic galactose -PEI-Dox); (b) L2-Dox (cyclic mannose -PEI-Dox); (c) L5-Dox (trimannoside-PEI-Dox). FITC-labeled ligands used for tracking: L2-FITC. Images display 4 imaging modalities: (1) FITC fluorescence (green, excitation: 488 nm, emission: 505-535 nm) indicating the distribution of the profiling glycan ligand; (2) Doxorubicin fluorescence (red, excitation: 515 nm, emission: 575-675 nm) indicating the intracellular localization of the delivered drug; (3) Brightfield microscopy for cellular morphology; and (4) A merged overlay of all channels to assess co-localization. Scale bar represents 50 µm.

Table 1.

Physico-chemical parameters of a series of macrophage phenotype profiling (FITC) ligands and a series of macrophage remodeling (Dox) ligands. PBS (0.01 M, pH 7.4). T = 37 °C.

Table 1.

Physico-chemical parameters of a series of macrophage phenotype profiling (FITC) ligands and a series of macrophage remodeling (Dox) ligands. PBS (0.01 M, pH 7.4). T = 37 °C.

| Code |

Ligand |

Molar Ratio of Constituents |

Hydrodynamic Diameter*, nm |

ζ-Potential*, mV |

Kdis (ConA–Ligand), M ** |

CD206 affinity*** |

CD209 affinity*** |

CD301 affinity*** |

| L1 |

ManLin-PEI FITC or Dox |

15:1:1 |

105 ± 10 |

+10 ± 2 |

(7 ± 2) × 10–4

|

+ |

– |

– |

| L2 |

ManCyc-PEI FITC or Dox |

18:1:1 |

115 ± 15 |

(5 ± 1) × 10–6

|

++ |

± |

– |

| L3 |

GalLin-PEI FITC or Dox |

16:1:1 |

110 ± 15 |

(3 ± 1) × 10–3

|

– |

– |

± |

| L4 |

GalCyc-PEI FITC or Dox |

13:1:1 |

115 ± 10 |

(9 ± 1) × 10–5

|

+ |

– |

+ |

| L5 |

triMan-GlcNAc2-PEI FITC or Dox |

10:1:1 |

130 ± 20 |

(2.5 ± 0.3) × 10–7

|

+++ |

+ |

+ |

Table 2.

Binding data, expressed as a percentage ranging from 0 to 100, for ligands 1–5 (L1–L5) in the absence and presence of mannan (ML1–ML5), respectively, for macrophage cells derived from BALF obtained from healthy donor and patient with bronchiectasis, both before and after administration of five targeted Dox formulations. The experimental error did not exceed 10 %. Pronounced changes are highlighted in bold.

Table 2.

Binding data, expressed as a percentage ranging from 0 to 100, for ligands 1–5 (L1–L5) in the absence and presence of mannan (ML1–ML5), respectively, for macrophage cells derived from BALF obtained from healthy donor and patient with bronchiectasis, both before and after administration of five targeted Dox formulations. The experimental error did not exceed 10 %. Pronounced changes are highlighted in bold.

| Ligand/cells |

Intact BALF |

BALF after Dox-L1 |

BALF after Dox-L2 |

BALF after Dox-L3 |

BALF after Dox-L4 |

BALF after Dox-L5 |

Healthy BALF |

М0 |

М1 |

М2а |

| FITC-L1 |

9 |

12 |

12 |

9 |

10 |

3 |

9 |

9 |

11 |

4 |

| FITC-L2 |

25 |

21 |

30 |

27 |

21 |

18 |

5 |

9 |

10 |

20 |

| FITC-L3 |

8 |

19 |

27 |

20 |

18 |

14 |

1 |

5 |

2 |

13 |

| FITC-L4 |

7 |

10 |

10 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

5 |

11 |

14 |

3 |

| FITC-L5 |

26 |

28 |

27 |

24 |

19 |

1 |

2 |

8 |

12 |

1 |

| FITC-ML1 |

9 |

9 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

8 |

5 |

17 |

| FITC-ML2 |

21 |

18 |

26 |

18 |

17 |

14 |

3 |

6 |

8 |

20 |

| FITC-ML3 |

5 |

16 |

25 |

13 |

16 |

12 |

6 |

8 |

1 |

15 |

| FITC-ML4 |

6 |

8 |

6 |

8 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

10 |

12 |

19 |

| FITC-ML5 |

17 |

23 |

28 |

23 |

17 |

10 |

4 |

6 |

10 |

17 |

Table 3.

The deconvolution of relative contributions in percentage terms of monocyte M0 and macrophage M1 and M2 binding profiles for ligands 1–5 (L1–L5) was conducted in the absence and presence of mannan (ML1–ML5), respectively. The data was obtained from macrophages derived from BALF, collected from a patient with bronchiectasis, both prior to and following the administration of five distinct Dox formulations. The experimental error did not exceed 10 %.

Table 3.

The deconvolution of relative contributions in percentage terms of monocyte M0 and macrophage M1 and M2 binding profiles for ligands 1–5 (L1–L5) was conducted in the absence and presence of mannan (ML1–ML5), respectively. The data was obtained from macrophages derived from BALF, collected from a patient with bronchiectasis, both prior to and following the administration of five distinct Dox formulations. The experimental error did not exceed 10 %.

| Relative contribution, % |

Deconvolution based on L1-L5 data |

Deconvolution based on ML1-ML5 data |

Deconvolution based on L1-L5 and ML1-ML5 data |

| BALF cells / reference |

M0 |

M1 |

M2a |

M2b-c-d |

M0 |

M1 |

M2a |

M2b-c-d |

M0 |

M1 |

M2a |

M2b-c-d |

| Intact BALF |

<1 |

50 |

27 |

23 |

<1 |

35 |

43 |

22 |

<1 |

55 |

18 |

27 |

| BALF after Dox-L1 |

31 |

24 |

22 |

23 |

<1 |

<1 |

82 |

18 |

29 |

28 |

17 |

26 |

| BALF after Dox-L2 |

41 |

6 |

37 |

16 |

<1 |

<1 |

60 |

40 |

23 |

16 |

24 |

36 |

| BALF after Dox-L3 |

<1 |

34 |

46 |

20 |

<1 |

30 |

41 |

29 |

<1 |

39 |

27 |

34 |

| BALF after Dox-L4 |

20 |

20 |

42 |

19 |

<1 |

<1 |

67 |

33 |

24 |

15 |

24 |

36 |

| BALF after Dox-L5 |

<1 |

<1 |

99 |

<1 |

<1 |

<1 |

50 |

50 |

25 |

16 |

25 |

35 |

Healthy

control |

77 |

<1 |

<1 |

23 |

18 |

<1 |

15 |

28 |

63 |

<1 |

<1 |

28 |

Table 4.

Summary of phenotypic remodeling and proposed mechanisms of Dox on BALF macrophages from three pediatric patients with distinct underlying pathologies leading to chronic lung inflammation and bronchiectasis.

Table 4.

Summary of phenotypic remodeling and proposed mechanisms of Dox on BALF macrophages from three pediatric patients with distinct underlying pathologies leading to chronic lung inflammation and bronchiectasis.

| Sample |

Diagnosis |

Treatment |

M0 (%) |

M1 (%) |

M2a (%) |

M2b-c-d (%) |

| BALF1 |

Bronchiectasis in the middle lobe of the right lung (J47) |

Intact |

<1 |

55 |

18 |

27 |

| + Doxorubicin |

<1 |

40 |

29 |

31 |

| BALF2 |

Immunodeficiency, complicated by bronchiectasis, chronic bronchitis |

Intact |

<1 |

29 |

32 |

39 |

| + Doxorubicin |

<1 |

18 |

43 |

39 |

| BALF3 |

Obliterative bronchiolitis (J84.8) |

Intact |

17 |

20 |

8 |

55 |

| + Doxorubicin |

25 |