Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

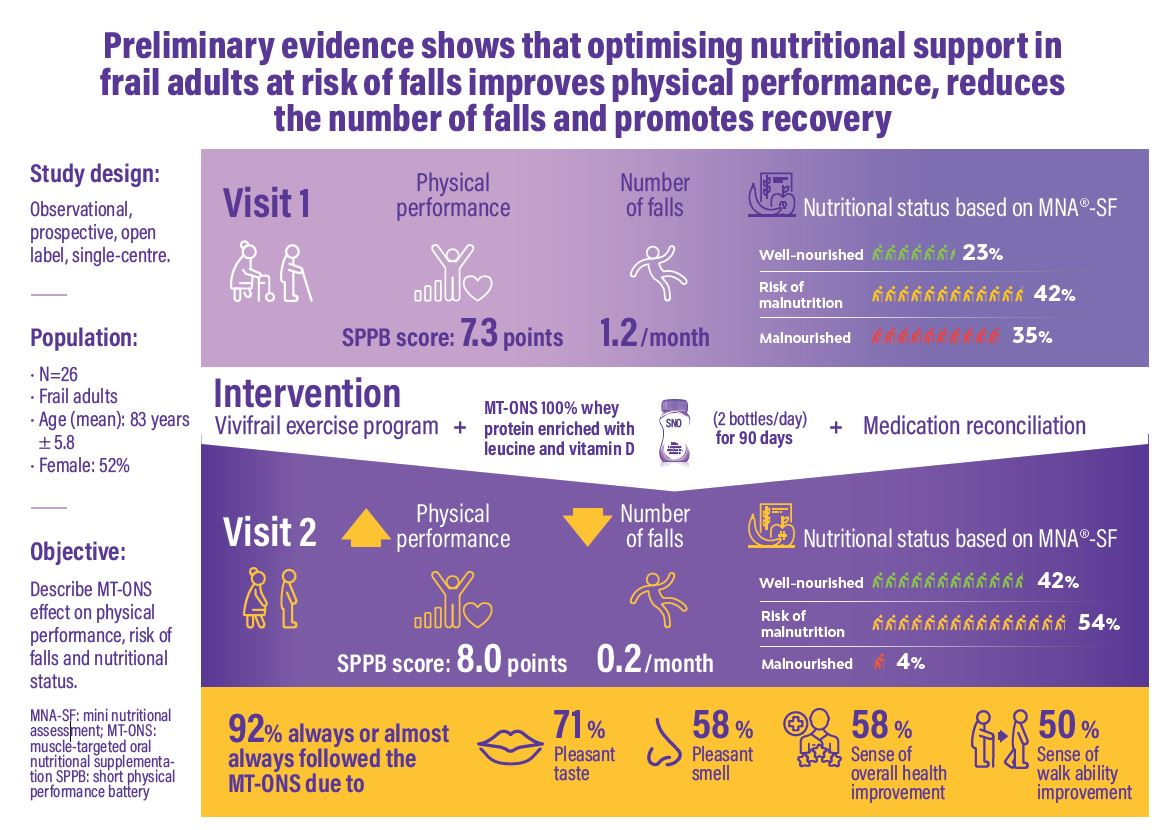

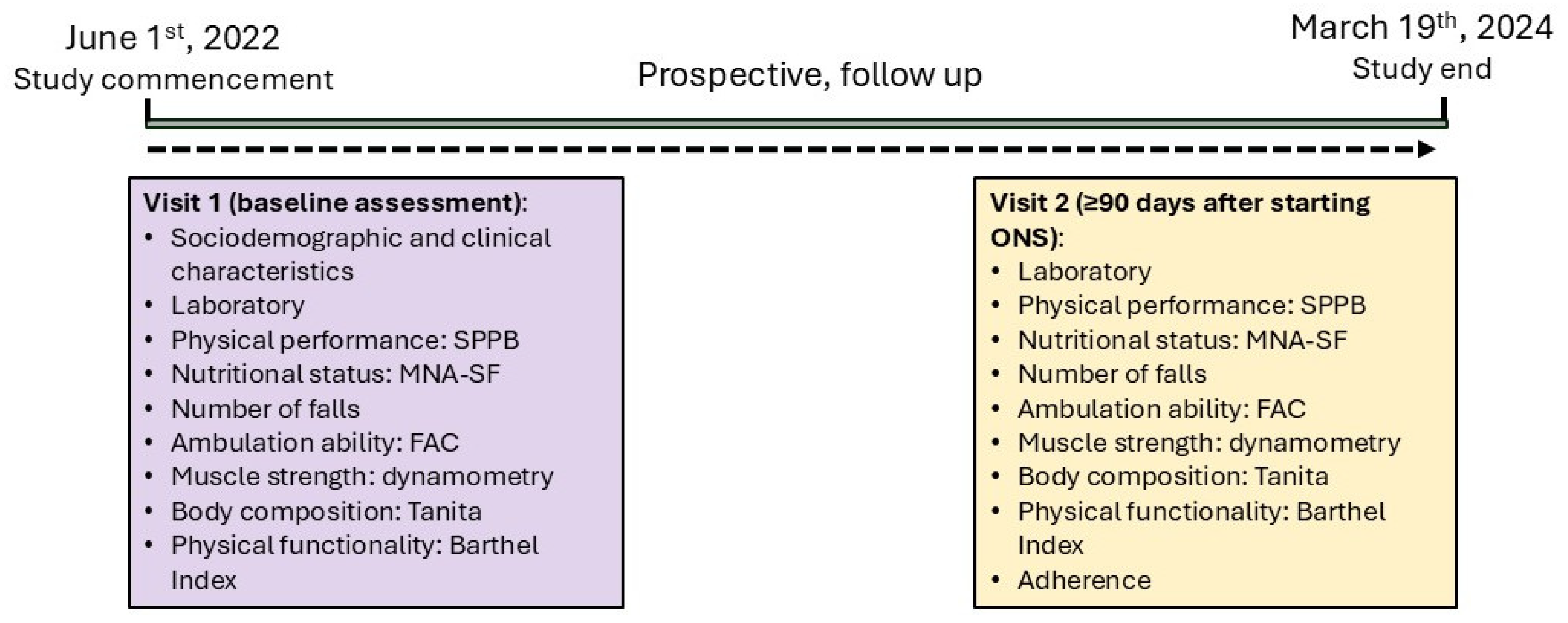

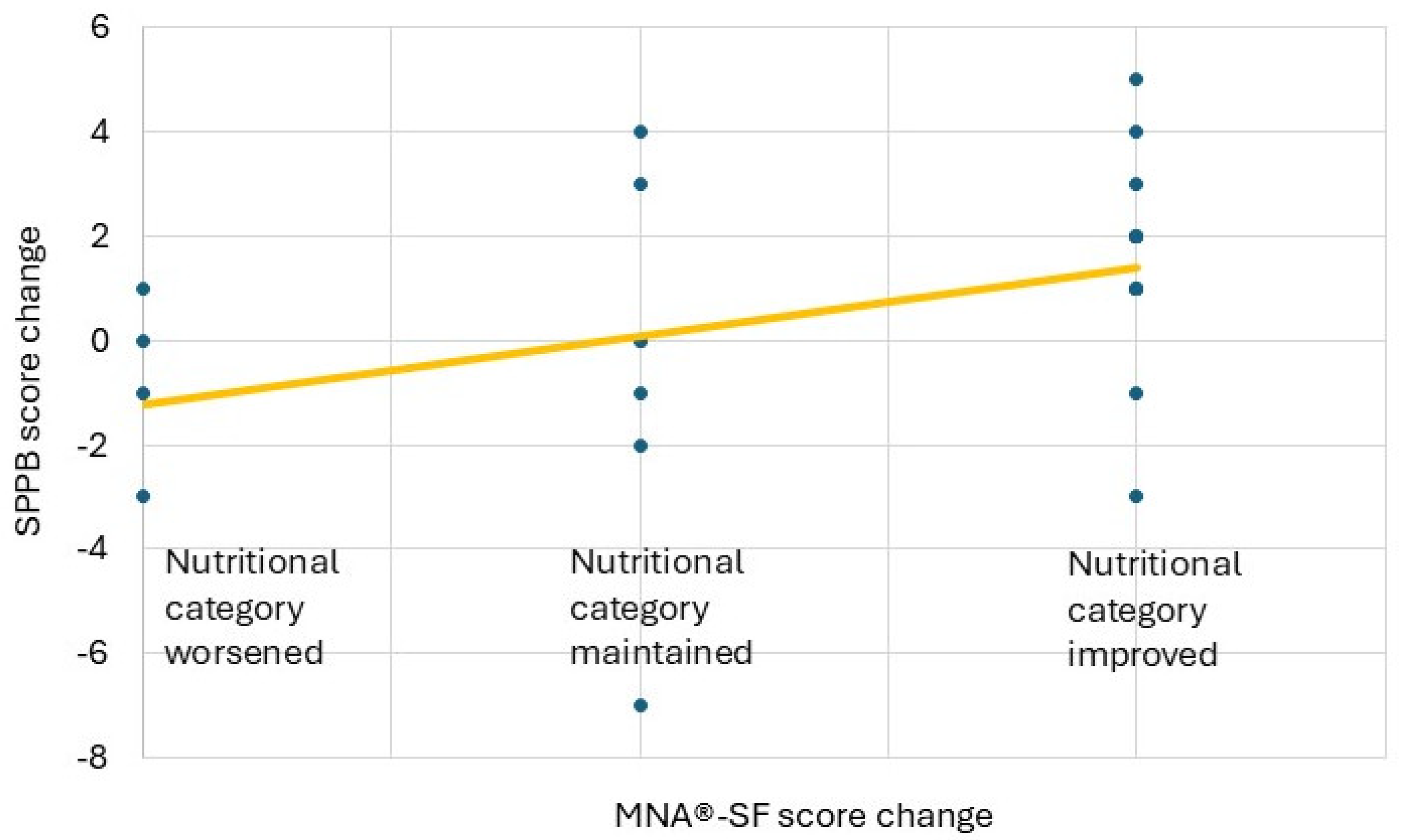

Background/Objectives: The study aimed to describe the effect of muscle-targeted oral nutritional supplementation (MT-ONS) on enhancing physical performance and nutritional status in frail adults at risk of falls. Methods: A prospective, open-label, single-centre, descriptive study was conducted. Patients ≥70 years attending an outpatient fall clinic were recruited, assessed at baseline and after at least 90 days with MT-ONS 100% whey protein enriched with leucine and vitamin D. Sociodemographic, physical performance [Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB)], nutritional status [Mini Nutritional Assessment-Short Form, (MNA®-SF)], walking ability [Functional Ambulation Categories (FAC)], number of falls, muscle strength (dynamometry), body composition (Tanita), health-related quality-of-life (SF-12), functional capacity (Barthel Index) and adherence data were collected. Descriptive and inferential statistics were performed. Results: Twenty-six patients were assessed (58% women age: 82.1 ±5.4 years). Mean SPPB score increased from 7.3 (±3.6) to 8.0 (±4.0). At baseline, 35% were malnourished, 42% at risk of malnutrition, and 23% well-nourished. After ≥90 days of muscle-targeted ONS, 4% were malnourished; 54% at risk and 42% well-nourished. The number of falls decreased from 1.2 falls/month (±0.9) to 0.2 falls/month (±0.3, p<0.0001). Change to better physical performance correlated positively with better nutritional status (p=0.03) after MT-ONS. 92% of patients nearly always followed the ONS recommendations due to pleasant taste (71%) and smell (58%) and good health perception (58%). Conclusions: Frail adults at risk of falls who received MT-ONS, 100% whey protein enriched with leucine and vitamin D for ≥90 days improved their physical performance and nutritional status and reduced the number of falls.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Design

Study Population

Recruitment and Assessment

Intervention

Statistical Analysis

Ethical Considerations

3. Results

Study Population

Clinical and Functional Characteristics at Follow Up (Visit 2)

Physical Performance, Muscle Strength and Nutritional Status

Physical Performance and Health Related Quality of Life

BMI, Muscle Strength, and Gait Stability as Predictors of SPPB Improvement

BMI, Muscle Strength, Physical Performance and Improved MNA®-SF

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADL | Activities of Daily Living |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| FAC | Functional Ambulation Categories |

| IADL | Instrumental Activities of Daily Living |

| MNA®-SF | Mini Nutritional Assessment – Short Form |

| MT-ONS | Muscle-Targeted Oral Nutritional Supplementation |

| ONS | Oral Nutritional Supplementation |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SF-12 | 12-item Short Form Health Survey |

| SPPB | Short Physical Performance Battery |

| V1 | Visit 1 (Baseline) |

| V2 | Visit 2 (Follow-up) |

References

- Kwak, D.; Thompson, L.V. Frailty: Past, present, and future? Sport Med Heal Sci. 2021, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivas-Ruiz, F.; Machón, M.; Contreras-Fernández, E.; Vrotsou, K.; Padilla-Ruiz, M.; Díez Ruiz, A.I.; et al. Prevalence of frailty among community-dwelling elderly persons in Spain and factors associated with it. Eur J Gen Pract. 2019, 25, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, B.; Walter, S.; Rodríguez-Laso, A.; Carnicero Carreño, J.A.; García-García, F.J.; Álvarez-Bustos, A.; et al. Differential Association of Frailty and Sarcopenia With Mortality and Disability: Insight Supporting Clinical Subtypes of Frailty. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022, 23, 1712–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doody, P.; Lord, J.M.; Greig, C.A.; Whittaker, A.C. Frailty: Pathophysiology, Theoretical and Operational Definition(s), Impact, Prevalence, Management and Prevention, in an Increasingly Economically Developed and Ageing World. Gerontology. 2023, 69, 927–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun KD, Kenneth R. Frailty in Older Adults. N Engl J Med [Internet]. 2024 Aug 7;391(6):538–48. [CrossRef]

- Sayer, A.A.; Cooper, R.; Arai, H.; Cawthon, P.M.; Ntsama Essomba, M.J.; Fielding, R.A.; et al. Sarcopenia. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2024, 10, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, S.S.Y.; Reijnierse, E.M.; Pham, V.K.; Trappenburg, M.C.; Lim, W.K.; Meskers, C.G.M.; et al. Sarcopenia and its association with falls and fractures in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019, 10, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Díaz, L.B.; Casuso-Holgado, M.J.; Labajos-Manzanares, M.T.; Barón-López, F.J.; Pinero-Pinto, E.; Romero-Galisteo, R.P.; et al. Analysis of Fall Risk Factors in an Aging Population Living in Long-Term Care Institutions in SPAIN: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Blanco, J.; Albornos-Muñoz, L.; Costa-Menen, M.À.; García-Martínez, E.; Rubinat-Arnaldo, E.; Martínez-Soldevila, J.; et al. Prevalence of falls in noninstitutionalized people aged 65-80 and associations with sex and functional tests: A multicenter observational study. Res Nurs Health. 2022, 45, 433–45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Komisar, V.; Dojnov, A.; Yang, Y.; Shishov, N.; Chong, H.; Yu, Y.; et al. Injuries from falls by older adults in long-term care captured on video: Prevalence of impacts and injuries to body parts. BMC Geriatr [Internet]. 2022, 22, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoene D, Heller C, Aung YN, Sieber CC, Kemmler W, Freiberger E. A systematic review on the influence of fear of falling on quality of life in older people: is there a role for falls? Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:701–19.

- Vaishya R, Vaish A. Falls in Older Adults are Serious. Indian J Orthop. 2020 Feb;54(1):69–74.

- Florence CS, Bergen G, Atherly A, Burns E, Stevens J, Drake C. Medical Costs of Fatal and Nonfatal Falls in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018 Apr;66(4):693–8.

- Kurkcu M, Meijer RI, Lonterman S, Muller M, de van der Schueren MAE. The association between nutritional status and frailty characteristics among geriatric outpatients. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2018 Feb;23:112–6.

- Prado CM, Landi F, Chew STH, Atherton PJ, Molinger J, Ruck T, et al. Advances in muscle health and nutrition: A toolkit for healthcare professionals. Clin Nutr. 2022;41(10):2244–63.

- Pourhassan M, Rommersbach N, Lueg G, Klimek C, Schnatmann M, Liermann D, et al. The Impact of Malnutrition on Acute Muscle Wasting in Frail Older Hospitalized Patients. Nutrients. 2020 May;12(5).

- Cereda E, Pisati R, Rondanelli M, Caccialanza R. Whey Protein, Leucine- and Vitamin-D-Enriched Oral Nutritional Supplementation for the Treatment of Sarcopenia. Nutrients. 2022 Apr;14(7).

- Camargo L da R, Doneda D, Oliveira VR. Whey protein ingestion in elderly diet and the association with physical, performance and clinical outcomes. Exp Gerontol. 2020;137:110936.

- Hill TR, Verlaan S, Biesheuvel E, Eastell R, Bauer JM, Bautmans I, et al. A Vitamin D, Calcium and Leucine-Enriched Whey Protein Nutritional Supplement Improves Measures of Bone Health in Sarcopenic Non-Malnourished Older Adults: The PROVIDE Study. Calcif Tissue Int. 2019 Oct;105(4):383–91.

- Bauer JM, Verlaan S, Bautmans I, Brandt K, Donini LM, Maggio M, et al. Effects of a vitamin D and leucine-enriched whey protein nutritional supplement on measures of sarcopenia in older adults, the PROVIDE study: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015 Sep;16(9):740–7.

- Guo Y, Fu X, Hu Q, Chen L, Zuo H. The Effect of Leucine Supplementation on Sarcopenia-Related Measures in Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 17 Randomized Controlled Trials. Front Nutr. 2022;9:929891.

- Rondanelli M, Cereda E, Klersy C, Faliva MA, Peroni G, Nichetti M, et al. Improving rehabilitation in sarcopenia: a randomized-controlled trial utilizing a muscle-targeted food for special medical purposes. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2020 Dec;11(6):1535–47.

- Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in Older Adults: Evidence for a Phenotype. Journals Gerontol Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–57.

- Bouillon K, Kivimaki M, Hamer M, Sabia S, Fransson EI, Singh-Manoux A, et al. Measures of frailty in population-based studies: an overview. BMC Geriatr. 2013 Jun;13:64.

- Welch SA, Ward RE, Beauchamp MK, Leveille SG, Travison T, Bean JF. The Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB): A Quick and Useful Tool for Fall Risk Stratification Among Older Primary Care Patients. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2021 Aug;22(8):1646–51.

- Guigoz Y, Vellas B, Garry PJ. Assessing the nutritional status of the elderly: The Mini Nutritional Assessment as part of the geriatric evaluation. In: Nutrition Reviews. Blackwell Publishing Inc.; 1996.

- Molina-Luque R, Muñoz Díaz B, de la Iglesia J, Romero-Saldaña M, Molina-Recio G. Is the Spanish short version of Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA-SF) valid for nutritional screening of the elderly? Nutr Hosp Hosp. 2019;36(2):290–5.

- Holden MK, Gill KM, Magliozzi MR. Gait assessment for neurologically impaired patients. Standards for outcome assessment. Phys Ther. 1986 Oct;66(10):1530–9.

- Vasold KL, Parks AC, Phelan DML, Pontifex MB, Pivarnik JM. Reliability and Validity of Commercially Available Low-Cost Bioelectrical Impedance Analysis. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2019 Jul;29(4):406–410.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, Cederholm T, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019 Jan;48(1):16–31.

- Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, Apolone G, Bjorner JB, Brazier JE, et al. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998 Nov;51(11):1171–8.

- Cabañero-Martínez MJ, Cabrero-García J, Richart-Martínez M, Muñoz-Mendoza CL. Structured review of activities of daily living measures in older people. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol. 2008;43(5):271–83.

- Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. FUNCTIONAL EVALUATION: THE BARTHEL INDEX. Md State Med J. 1965 Feb;14:61–5.

- Nutricia. Fortimel Advanced [Internet]. [cited 2024 Oct 3]. p. 1–5. Available from: https://vademecum.nutricia.es/pdf/info_nutricional/prod_304.pdf.

- Izquierdo, M. [Multicomponent physical exercise program: Vivifrail]. Nutr Hosp. 2019 Jul;36(Spec No2):50–6.

- Beuscart JB, Pelayo S, Robert L, Thevelin S, Marien S, Dalleur O. Medication review and reconciliation in older adults. Eur Geriatr Med. 2021 Jun;12(3):499–507.

- Hui EGM. Inferential Statistics and Regressions BT - Learn R for Applied Statistics: With Data Visualizations, Regressions, and Statistics. In: Hui EGM, editor. Berkeley, CA: Apress; 2019. p. 173–236.

- Bermejo Boixareu C, Ojeda-Thies C, Guijarro Valtueña A, Cedeño Veloz BA, Gonzalo Lázaro M, Navarro Castellanos L, et al. Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of Centenarians versus Other Age Groups Over 75 Years with Hip Fractures. Clin Interv Aging. 2023;18:441–51.

- Solsona Fernández S, Caverni Muñoz A, Labari Sanz G, Monterde Hernandez B, Martínez Marco MA, Mesa Lampré P. Preliminary Evidence on the Effectiveness of a Multidisciplinary Nutritional Support for Older People with Femur Fracture at an Orthogeriatric Unit in Spain. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr [Internet]. 2022 Oct 2;41(4):270–93. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Spanish Ministry of Health. Update of the consensus document on prevention of frailty in elderly people [Internet]. Reports, studies and research 2023. 2022. p. 1–61. Available from: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/areas/promocionPrevencion/envejecimientoSaludable/fragilidadCaidas/home.htm.

- Hart LA, Phelan EA, Yi JY, Marcum ZA, Gray SL. Use of Fall Risk-Increasing Drugs Around a Fall-Related Injury in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020 Jun;68(6):1334–43.

- Yoshida Y, Ishizaki T, Masui Y, Hori N, Inagaki H, Ito K, et al. Effect of number of medications on the risk of falls among community-dwelling older adults: A 3-year follow-up of the SONIC study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2024 Mar;24 Suppl 1:306–10.

- Dautzenberg L, Beglinger S, Tsokani S, Zevgiti S, Raijmann RCMA, Rodondi N, et al. Interventions for preventing falls and fall-related fractures in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021 Oct;69(10):2973–84.

- Montero-Odasso M, van der Velde N, Martin FC, Petrovic M, Tan MP, Ryg J, et al. World guidelines for falls prevention and management for older adults: a global initiative. Age Ageing [Internet]. 2022 Sep 2;51(9):afac205. [CrossRef]

- de Fátima Ribeiro Silva C, Ohara DG, Matos AP, Pinto ACPN, Pegorari MS. Short Physical Performance Battery as a Measure of Physical Performance and Mortality Predictor in Older Adults: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Oct;18(20).

- Bernabei R, Landi F, Calvani R, Cesari M, Del Signore S, Anker SD, et al. Multicomponent intervention to prevent mobility disability in frail older adults: randomised controlled trial (SPRINTT project). Bmj. 2022;377:1–13.

- Artaza-Artabe I, Sáez-López P, Sánchez-Hernández N, Fernández-Gutierrez N, Malafarina V. The relationship between nutrition and frailty: Effects of protein intake, nutritional supplementation, vitamin D and exercise on muscle metabolism in the elderly. A systematic review. Maturitas. 2016 Nov;93:89–99.

- Navarrete-Villanueva D, Gómez-Cabello A, Marín-Puyalto J, Moreno LA, Vicente-Rodríguez G, Casajús JA. Frailty and Physical Fitness in Elderly People: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sport Med [Internet]. 2021;51(1):143–60. [CrossRef]

- Wang DXM, Yao J, Zirek Y, Reijnierse EM, Maier AB. Muscle mass, strength, and physical performance predicting activities of daily living: a meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2020 Feb;11(1):3–25.

| Characteristic | Title 2 |

| Age, years (±SD) | 82 (±5.4) |

| Gender | |

| Female, n (%) | 15 (58%) |

| Male, n (%) | 11 (42%) |

| Marital status | |

| Single, n (%) | 1 (4%) |

| In a relationship, n (%) | 14 (54%) |

| Married, n (%) | 2 (8%) |

| Divorced, n (%) | 0 (0%) |

| Widow, n (%) | 9 (34%) |

| Household living conditions | |

| Alone, n (%) | 8 (31%) |

| Accompanied, n (%) | 18 (69%) |

| Institution | 0 (0%) |

| Characteristics | Visit 1 | Visit 2 |

| Nutritional status: MNA®-SF score | ||

| 12–14 points, well- nourished, n (%) | 6 (23%) | 11 (42%) |

| 8–11 points, at risk of malnutrition, n (%) | 11 (42%) | 14 (54%) |

| 0–7 points, malnourished, n (%) | 9 (35%) | 1 (4%%) |

| Laboratory (nutritional) parameters | ||

| Serum albumin levels (g/dl) mean (±SD) | 4.0 (±0.5) | 4.3 (±0.59) |

| Cholesterol levels (md/dl) mean (±SD) | 156.0 (±38.9) | 156.0 (±34.67) |

| Lymphocyte count (x1000/µl) mean (±SD) | 1.5 (±0.6) | 1.5 (±0.59) |

| Weight, kg (SD) | 66.6 (±11.88) | 68.4 (±12.54) |

| BMI | 25.9 (6.61) | 26.7 (±4.33) |

| Body composition: Tanita | ||

| Muscle mass (%) | 42% | 42% |

| Total body water /%) | 48% | 47% |

| Body fat (%) | 34% | 34% |

| Bone mass, kg (SD) | 3.1 (±4.09) | 3.1 (±4.16) |

| Visceral fat | 17.1 (±17.71) | 16.2 (±7.20) |

| Metabolic age | 73.6 (±9.55) | 74.9 (±9.48) |

| Lower body physical function: SPPB score, mean (SD) | 7.3 (±3.56) | 8.0 (±4.03) |

| Good physical function (SPPB scores 10-12), n (%) | 7 (27%) | 14 (54%) |

| Mild limitations (SPPB scores 7-9), n (%) | 9 (35%) | 3 (12%) |

| Moderate limitations (SPPB scores 4-6), n (%) | 5 (19%) | 3 (12%) |

| Severe physical limitations (SPPB scores 0-3), n (%) | 5 (19%) | 6 (22%) |

| Number of falls/month, mean (SD) | 1.2 (±0.9) | 0.2 (±0.3) |

| Number of falls/month, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 5 (19%) | 19 (73%) |

| 1 | 17 (65%) | 7 (27%) |

| 2 | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| 3 | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

| 4 | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Walking ability: FAC score | ||

| 5: normal deambulation, n (%) | 6 (22%) | 9 (35%) |

| 4: able to walk anywhere but with obvious limp or need of technical assistance, n (%) | 8 (31%) | 6 (22%) |

| 3: able to walk inside and outside of home but limited distances, n (%) | 9 (35%) | 9 (35%) |

| 2: only able to walk on flat surfaces and known spaces like home, n (%) | 3 (12%) | 1 (4%) |

| 1: requires external help to be able to walk, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) |

| Dynamometry | ||

| Muscle strength right hand, kg (SD) | 15.6 (±8.65) | 15.7 (±9.19) |

| Muscle strength left hand, kg (SD) | 12.6 (±5.48) | 13.9 (6.61) |

| Independence to perform basic activities of daily living: Barthel Index score | ||

| ≥ 60 points (independent), n (%) | 24 (92%) | 25 (96%) |

| < 60 points (dependant), n (%) | 2 (8%) | 1 (4%) |

| SF-12, score general health perception | ||

| Excellent, n (%) | 1 (4%) | 1 (4%) |

| Very good, n (%) | 2 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Good, n (%) | 11 (42%) | 14 (54%) |

| Moderate, n (%) | 11 (42%) | 9 (35%) |

| Bad, n (%) | 1 (4%) | 2 (8%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).