1. Introduction

Ageing is associated with declining muscle mass, function, and strength (sarcopenia) [

1]. This loss increases with age and is further accelerated by a sedentary lifestyle, weight loss and physical disease. Loss of muscle mass and sarcopenia are associated with adverse health outcomes in older adults, such as falls, mortality, cognitive decline, and disability [

2,

3]. Sarcopenia is linked to several chronic conditions such as liver cirrhosis, diabetes, osteoporosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), kidney failure, and cancer, as well as acute conditions such as stroke and trauma [

4].

Although physical exercise and increased protein intake are effective in reducing sarcopenia, there is insufficient evidence to support the effectiveness of other treatment options, medical foods, or nutritional interventions. Therefore, specific dietary recommendations cannot be made [

5]. Certain nutrients, including vitamin D, calcium, and omega-3 fatty acids (or their combination), may have a positive impact on muscle maintenance and strength [

6,

7], with larger increases being reported in muscle quality and function for women compared to men for nutrients like long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) [

8]. Still, gaining a deeper understanding of nutrients that may be linked to preserving muscle health is crucial in developing new dietary interventions. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the association of dietary components with appendicular, total lean mass, gait speed (muscle performance) and hand grip strength (muscle strength).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design, settings and participants

Cross-sectional data were derived from the Swedish population-based Gothenburg H70 Birth Cohort Study (H70 study) on 70-year-olds born in 1944 and examined between 2014 and 2016 (n= 1,203). The response rate was 72 % [

9,

10]. See detailed sample description in supplementary material

Figure S1.

2.2. Anthropometry

Body weight and height were measured using a calibrated electronic scale and a stadiometer, respectively. Body composition was analyzed using Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan (Lunar Prodigy scanner). The appendicular lean soft tissue index (ALSTI) was used to estimate lean mass and was calculated as the sum of lean soft tissue in arms and legs divided by squared body height. The scanners were cross-calibrated using a double scan of 33 subjects, with the iDXA ALSTI measurements calibrated using a regression-derived equation.

2.3. Muscle strength and performance

Physical performance tests included the self-selected and maximum gait speed, measured in meters per second over a 30-meter indoor distance with a standing start [

11,

12].

Moreover, the measurement of distance covered in a six-minute indoor walking test was documented in meters. Grip strength was evaluated using both a Martin Vigorimeter and, for a subset of participants, a JAMAR dynamometer, while ensuring the shoulder joint remained in a neutral position. This assessment was conducted thrice for each hand, and the highest recorded value from the dominant hand was considered as the final result [

13]. Results are reported in kPa as provided by the study and as previously reported by Wallengren et al. [

14].

2.4. Dietary examination

The previously validated diet history method (DH) was used to estimate dietary intake [

15]. The DH used in this study was a semi-structured face-to-face interview performed by a registered dietitian, estimating habitual dietary intake during the preceding three months. The interview protocol consisted of a meal-pattern interview, accompanied by a food list with questions on usual frequencies and portion sizes of foods. Pictures of foods from the Swedish Food Agency (SFA) were used to estimate individual portion sizes during the interviews. Dietary intake was registered as grams of food items usually consumed per day/week/month in the nutritional calculation computer program Dietist Net Pro, containing the SFAs nutrient database of 2015. Estimated mean daily energy and nutrient intake was calculated based on results from the DH interview. Dietary supplements were not included in this study.

2.5. Dietary components included

Mean daily energy, alcohol, and nutrient intakes were estimated based on results from the DH interview. In this study, we included data on energy (mean kcal intake/day), protein, carbohydrates, dietary fiber, total fat, saturated fatty acids, monounsaturated fatty acids, PUFAs, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), protein, and alcohol intake, all measured in mean gram intakes/day. Nutrients included were vitamins C (mean mg intake/day), D (mean µg intake/day), E (mean mg intake/day), thiamine (B1) (mean mg intake/day), riboflavin (B2) (mean mg intake/day), niacin equivalents (mean mg intake/day), B6 (mean mg intake/day), B12 (mean µg intake/day), folate (B9) (mean µg intake/day), and retinol equivalents (mean µg intake/day), as well as iron (mean mg intake/day), calcium (mean mg intake/day), phosphorus (mean mg intake/day), magnesium (mean mg intake/day), potassium (mean mg intake/day), zinc (mean mg intake/day), and selenium (mean µg intake/day).

2.6. Statistical analysis

First, it was provided a description of the included variables, estimating percentages for categorical variables and averages and standard deviations for numerical variables. Subsequently, differences between men and women were assessed by applying Pearson's chi-square test for categorical variables and Student's t-test for numerical variables. Finally, linear regression models were used to analyze the relationship between the dependent variables (i.e., ALSTI, handgrip strength, and gait speed) and each of the covariates, while controlling for sex, mean energy intake (kcal/day), and the interaction between the exposure variable and sex. The estimated coefficients, standard errors, and p-values for each exposure variable were reported. In addition, correlation graphs were constructed to visualize the association between the ALSTI and the statistically significant covariates. The statistical significance level was set at 0.05, and the Benjamini & Hochberg method was used to adjust for multiple comparisons [

16]. The analyses were performed using R version 4.2.1 and STATA 17.0 software.

2.7. Ethical considerations

Participants provided informed consent, and the study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive results

719 individuals were included (56.7% females). Muscle measurements were significantly higher in men: ALSTI (kg/m2) mean for men and women were 7.83 ± 0.77 and 6.21 ± 0.64 (p<0.001), respectively. Sarcopenia confirmed and Sarcopenia severe were more prevalent in men (

Table 1).

Men had a predominantly higher nutrient’s intake, except for vitamin C (mg) and vitamin E (mg). No participants had an intake below average requirement level (

Table 2).

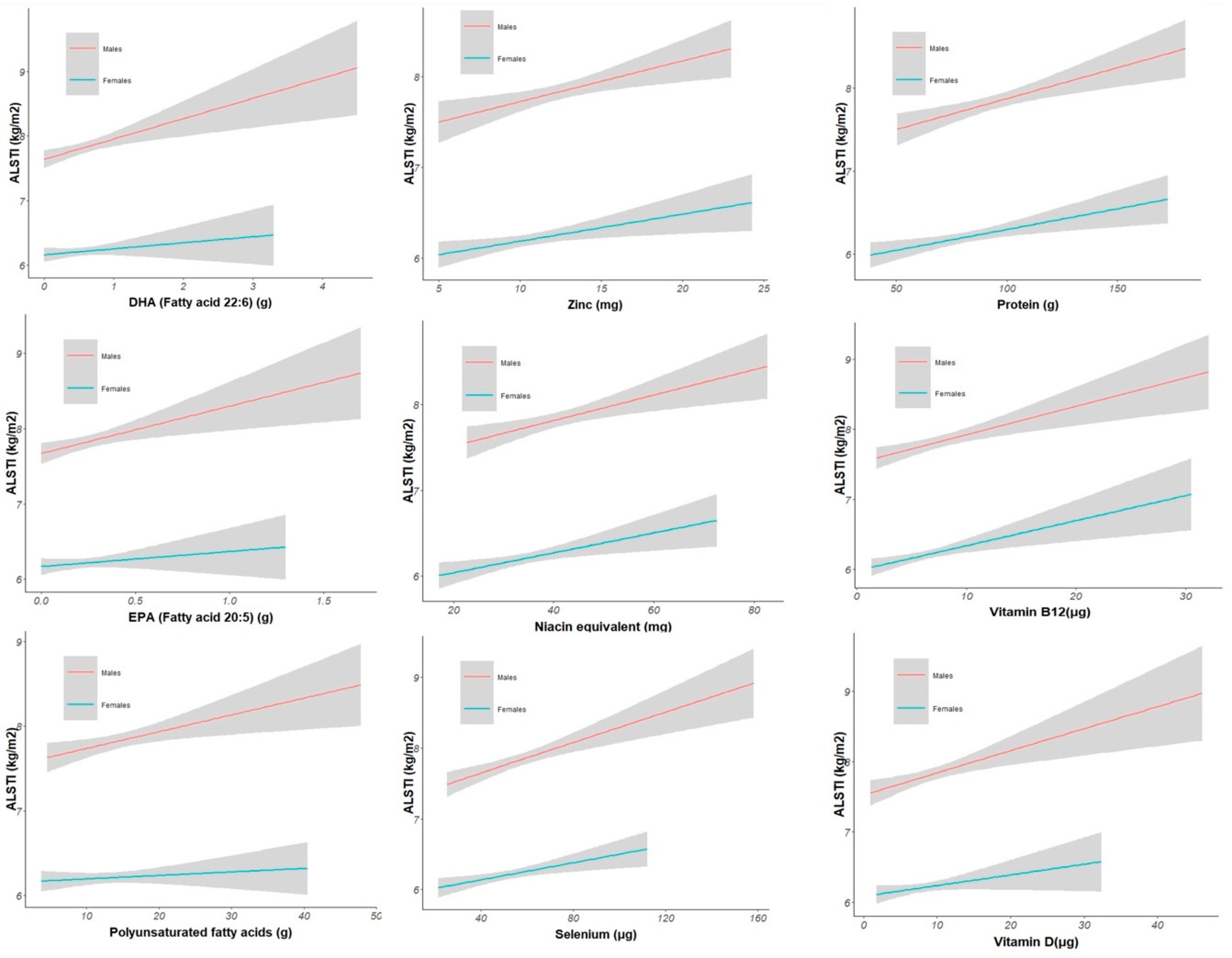

3.2. Association between nutrients and ALSTI

Several nutrients were positively associated with ALSTI, maintaining statistical significance after multiple comparison adjustments. The strongest associations were found for the PUFAs (Est 0.0171 SE 0.0072, p adjusted = 0.034), EPA (Est 0.5892 SE 0.1968, p adjusted = 0.008), DHA (Est 0.2978 SE 0.0875, p adjusted = 0.003), selenium (Est 0.0109 SE 0.0024, p adjusted < 0.001), zinc (Est 0.0604 SE 0.0172, p adjusted = 0.003), riboflavin (Est 0.2068 SE 0.0838, p adjusted = 0.029), niacin equivalent (Est 0.0176 SE 0.0049, p adjusted = 0.003), vitamin B12 (Est 0.0397 SE 0.0104, p adjusted = 0.001), vitamin D (Est 0.0292 SE 0.0089, p adjusted = 0.004), iron (Est 0.0439 SE 0.0137, p adjusted = 0.005) and protein (Est 0.017 SE 0.0023, p adjusted < 0.001) (Supplementary material

Table S1). Correlation models are displayed in

Figure 1.

3.3. Association between nutrients and handgrip strength (kPa)

Fibers, iron, vitamin E and vitamin B6 were significantly related to handgrip strength. However, after multiple comparison, none of them remained significant (Supplementary material

Table S1).

3.4. Association between nutrients and gait speed 30 m (m/s)

Gait speed correlated with the consumption of calcium and riboflavin; however, after multiple comparation adjustments, no variables remained significantly correlated (Supplementary material

Table S1).

4. Discussion

The results of this study indicate that there were several nutrients associated with ALSTI; specifically, positive associations were identified for protein, PUFAs such as DHA and EPA, iron, vitamin D, riboflavin, niacin equivalents, vitamin B12, zinc and selenium. These nutrients play important roles in supporting the correct body functioning, contributing significantly to overall health and well-being [

6,

17]. Enhancing muscle health by increasing the consumption of these nutrients can potentially lead to benefits such as muscle mass growth, improved strength, function and enhanced overall health. Nutrient intake in relation to sarcopenia has been previously studied. The most widely studied association has been the inadequate protein intake with a higher prevalence of sarcopenia, low muscle mass and low muscle strength. Such findings have led to strong recommendations for adequate protein intake in older adults to prevent and treat sarcopenia [

18,

19].

Our findings highlight that some nutrients, e.g. vitamin D, correlate with higher lean mass. Vitamin D can suppress the activity of atrophy-related transcription factors and may also stimulate protein synthesis [

20]. A recent report by Yang et al. demonstrated that a combination of physical inactivity and low serum vitamin D levels can exacerbate muscle atrophy in older individuals [

21]. However, consensus does not recommend vitamin D supplementation in older adults with sarcopenia as there is insufficient evidence to support their effectiveness [

22,

23,

24].

There is growing interest in exploring the effects of dietary antioxidants such as vitamins E, C, CoQ10, and anthocyanins on age-related muscle loss and dysfunction. It appears that antioxidants may positively affect muscle growth in the younger population [

25]. For older adults, antioxidants have mainly been studied for cognitive effects, with conflicting results [

26]. Several other micronutrients have been linked to sarcopenia. For example, there is evidence that low vitamin B12 (necessary to produce red blood cells and maintain nerve sheaths) is associated with muscle weakness and decreased physical function [

27]. In our study, the intake of vitamin B12 was significantly associated with ALSTI. Of note, no participants in this cohort had an intake below average requirement levels. Among older adults, vitamin B12 deficiency is usually not related to insufficient intake, but rather to decreased uptake due to atrophic gastritis or metformin intake, conditions that require vitamin B12 supplementation [

28]. In addition, other minerals were significantly related to muscle mass in our sample. For example, selenium may be important for sarcopenia prevention [

6]. It has been reported that selenium may play a role in preventing sarcopenia by reducing oxidative stress and inflammation, factors that likely contribute to age-related loss of muscle mass [

29].

Omega-3 fatty acids have anti-inflammatory properties and may help prevent muscle loss and maintain muscle function in older adults. Omega-3 PUFAs directly reduce the synthesis of cytokines that have pro-inflammatory functions [

30]. In addition, omega-3 PUFAs, particularly DHA, are key components of the phospholipids that form cell membranes and preserve the integrity and function of the cells [

18,

30]. Smith et al found that supplementation with DHA and EPA increased muscle strength in older women [

31]. It was also observed that supplementation with DHA and EPA in older adults increased muscle protein synthesis [

32]. However, although there is growing evidence on this topic, additional research is needed to determine the precise dosage, frequency, and application of sarcopenia treatment and prevention [

33].

Nutrients like EPA, DHA, Vitamin B12 and selenium have also been assessed for prevention of cognitive decline in older adults [

34]. It is proposed that a combination of nutrients might be required to synergistically increase brain levels of phosphatide molecules, that comprise the bulk of brain synaptic membranes [

35]. This might also have a role in the neuromuscular junction. In a pilot trial, at 12 weeks, significant improvement was noted in the delayed verbal recall task in the treatment group compared with the control [

34].

Although our study provides valuable insights into the relationship between muscle volume and dietary intake of several nutrients, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of this study. The study sample consisted of older individuals from a specific geographic area, who, in addition, fulfilled average nutrients requirement levels, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other populations. Moreover, the study design was cross-sectional, making it challenging to establish causality or determine the temporal sequence of events. Additionally, relying on self-reported data may introduce social desirability bias, memory recall bias, and other cognitive biases. However, this sample was relatively young and cognitively healthy, and the objective of this paper mainly focused on physical measures. Finally, the results of this paper were through diet history registry rather than blood nutrient levels.

Our analysis was conducted by separately examining two key aspects, muscle mass and muscle function. Muscle mass serves as a direct indicator linked to nutritional status, while the amalgamation of muscle mass and muscle function defines the condition known as sarcopenia. Analyzing these variables individually, owing to their linear nature, facilitates a more robust and dependable statistical approach. Notwithstanding, the intricate challenge of extrapolating the individual contribution of each nutrient to muscle mass/strength is noteworthy. Many of these nutrients serve as cofactors/activators in various metabolic processes, with zinc being a prominent example. Caution is essential when drawing conclusions based on findings, given the multifaceted roles these nutrients play.

In relation to the aforementioned concern, within the context of omega-3, which involves a more intricate metabolic process, these nutrients could enhance the metabolism of PUFAs to benefit muscle, particularly in males. Significant differences between males and females raise some questions [

8]: could estrogen stimulation of enzymes in this pathway explain the observed lower omega-3 levels in women over 70? Additionally, the decrease in circulating estrogen in postmenopausal women may impact the processing/synthesis of these nutrients, leading to suboptimal outcomes. These aspects warrant further investigation to enhance the depth of understanding regarding the observed patterns [

36].

This study has several strengths. The large sample size provides good statistical power to detect associations. Moreover, the cohort is population-based and hence representative of the population in this region, with comprehensive clinical assessments. The use of DXA to measure lean mass is a strength as it is considered the reference method.

The results may be important with the potential to improve the management alternatives for sarcopenia. However, due to controversies and insufficient evidence in certain areas, such as vitamin D or omega-3 supplementation, further research is needed to determine optimal dosage, frequency, and application of nutritional interventions for sarcopenia treatment and prevention.

5. Conclusions

In our analysis, we found that various nutrients, including fatty acids, zinc, and iron, were associated with higher muscle mass in cross-sectional examinations. These findings contribute significantly to the expanding body of knowledge concerning the role of specific nutrients in geriatric conditions. They underscore the potential for targeted interventions and strategies aimed at promoting healthy aging and preserving muscle health. As a consequence, the incorporation of these nutrients into one's diet or considering appropriate supplementation emerges as a promising approach for addressing sarcopenia and fostering healthy aging among older adults. Furthermore, these results offer a foundation for the development of clinical trials designed to broaden treatment options for individuals at risk of or already experiencing sarcopenia. Such initiatives hold the promise of improving health outcomes and enhancing the quality of life for the growing aging population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Population selection; Table S1: Linear association models.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, MGB, MUPZ and JS; methodology, MGB, MUPZ, JPB; validation, MGB, MUPZ, JPB,JS.GB,AZ,SK.LR.MGL,SSL,GD,IS and DA; formal analysis, JPB.; investigation, MGB, MUPZ, JPB,JS, GB.; resources IS and DA.; data curation, JPB,AZ,IS; writing—original draft preparation, MGB, MUPZ and JS; writing—review and editing, MGB, MUPZ, JPB,JS.GB,AZ,SK.LR.MGL,SSL,GD,IS and DA; visualization, MGB,MUPZ,JPB.; supervision, MUPZ, GD,IS and DA; project administration, DA, IS; funding acquisition, DA, IS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by: SK was financed by grants from the Swedish state under the agreement between the Swedish government and the county councils, the ALF-agreement (ALFGBG-965923, ALFGBG-81392, ALF GBG-771071). The Alzheimerfonden (AF-842471, AF-737641, AF-929959, AF-939825 ). The Swedish Research Council (2019-02075),Stiftelsen Psykiatriska Forskningsfonden, Stiftelsen Demensfonden, Stiftelsen Hjalmar Svenssons Forskningsfond, Stiftelsen Wilhelm och Martina Lundgrens vetenskapsfond. In addition, this paper represents independent research supported by the Norwegian government, through hospital owner Helse Vest (Western Norway Regional Health Authority). Also, funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care. LW is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship award.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the principal investigator.

Acknowledgments

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to all the participants, researchers, and technical staff whose invaluable contributions have made the H70 study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, Cederholm T, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):16-31.

- Yeung SSY, Reijnierse EM, Pham VK, Trappenburg MC, Lim WK, Meskers CGM, et al. Sarcopenia and its association with falls and fractures in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2019;10(3):485-500.

- Cipolli GC, Aprahamian I, Borim FSA, Falcão DVS, Cachioni M, Melo RC, et al. Probable sarcopenia is associated with cognitive impairment among community-dwelling older adults: results from the FIBRA study. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2021;79(5):376-83.

- Rosenberg, IH. Sarcopenia: origins and clinical relevance. J Nutr. 1997;127(5 Suppl):990S-1S.

- Morley, JE. Treatment of sarcopenia: the road to the future. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2018;9(7):1196-9.

- van Dronkelaar C, van Velzen A, Abdelrazek M, van der Steen A, Weijs PJM, Tieland M. Minerals and Sarcopenia; The Role of Calcium, Iron, Magnesium, Phosphorus, Potassium, Selenium, Sodium, and Zinc on Muscle Mass, Muscle Strength, and Physical Performance in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(1):6-11.e3.

- Robinson S, Granic A, Sayer AA. Nutrition and Muscle Strength, As the Key Component of Sarcopenia: An Overview of Current Evidence. Nutrients. 2019;11(12).

- Da Boit M, Sibson R, Sivasubramaniam S, Meakin JR, Greig CA, Aspden RM, et al. Sex differences in the effect of fish-oil supplementation on the adaptive response to resistance exercise training in older people: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105(1):151-8.

- Wetterberg H, Ryden L, Ahlner F, Falk Erhag H, Gudmundsson P, Guo X, et al. Representativeness in population-based studies of older adults: five waves of cross-sectional examinations in the Gothenburg H70 Birth Cohort Study. BMJ open. 2022;12(12):e068165.

- Rydberg Sterner T, Ahlner F, Blennow K, Dahlin-Ivanoff S, Falk H, Havstam Johansson L, et al. The Gothenburg H70 Birth cohort study 2014-16: design, methods and study population. Eur J Epidemiol. 2019;34(2):191-209.

- Bohannon, RW. Comfortable and maximum walking speed of adults aged 20-79 years: reference values and determinants. Age Ageing. 1997;26(1):15-9.

- Skillbäck T, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Skoog J, Rydén L, Wetterberg H, et al. Slowing gait speed precedes cognitive decline by several years. Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18(9):1667-76.

- Rydberg Sterner T, Ahlner F, Blennow K, Dahlin-Ivanoff S, Falk H, Havstam Johansson L, et al. The Gothenburg H70 Birth cohort study 2014-16: design, methods and study population. European journal of epidemiology. 2019;34(2):191-209.

- Wallengren O, Bosaeus I, Frandin K, Lissner L, Falk Erhag H, Wetterberg H, et al. Comparison of the 2010 and 2019 diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) in two cohorts of Swedish older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21(1):600.

- Samuelsson J, Rothenberg E, Lissner L, Eiben G, Zettergren A, Skoog I. Time trends in nutrient intake and dietary patterns among five birth cohorts of 70-year-olds examined 1971–2016: results from the Gothenburg H70 birth cohort studies, Sweden. Nutrition Journal. 2019;18(1):66.

- Haynes, W. Benjamini–Hochberg Method. In: Dubitzky W, Wolkenhauer O, Cho K-H, Yokota H, editors. Encyclopedia of Systems Biology. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2013. p. 78-.

- Muscaritoli, M. The Impact of Nutrients on Mental Health and Well-Being: Insights From the Literature. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2021;8.

- Bagheri A, Hashemi R, Heshmat R, Motlagh AD, Esmaillzadeh A. Patterns of Nutrient Intake in Relation to Sarcopenia and Its Components. Front Nutr. 2021;8:645072.

- Bauer J, Biolo G, Cederholm T, Cesari M, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Morley JE, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: a position paper from the PROT-AGE Study Group. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(8):542-59.

- Yang A, Lv Q, Chen F, Wang Y, Liu Y, Shi W, et al. The effect of vitamin D on sarcopenia depends on the level of physical activity in older adults. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2020;11(3):678-89.

- Uchitomi R, Oyabu M, Kamei Y. Vitamin D and Sarcopenia: Potential of Vitamin D Supplementation in Sarcopenia Prevention and Treatment. Nutrients. 2020;12(10).

- Dent E, Morley JE, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Arai H, Kritchevsky SB, Guralnik J, et al. International Clinical Practice Guidelines for Sarcopenia (ICFSR): Screening, Diagnosis and Management. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22(10):1148-61.

- Remelli F, Vitali A, Zurlo A, Volpato S. Vitamin D Deficiency and Sarcopenia in Older Persons. Nutrients. 2019;11(12).

- Gkekas NK, Anagnostis P, Paraschou V, Stamiris D, Dellis S, Kenanidis E, et al. The effect of vitamin D plus protein supplementation on sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Maturitas. 2021;145:56-63.

- Taherkhani S, Valaei K, Arazi H, Suzuki K. An Overview of Physical Exercise and Antioxidant Supplementation Influences on Skeletal Muscle Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021;10(10).

- Pritam P, Deka R, Bhardwaj A, Srivastava R, Kumar D, Jha AK, et al. Antioxidants in Alzheimer’s Disease: Current Therapeutic Significance and Future Prospects. Biology. 2022;11(2):212.

- Chae SA, Kim HS, Lee JH, Yun DH, Chon J, Yoo MC, et al. Impact of Vitamin B12 Insufficiency on Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling Older Korean Adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(23).

- Marchi G, Busti F, Zidanes AL, Vianello A, Girelli D. Cobalamin Deficiency in the Elderly. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2020;12(1):e2020043.

- Polidori MC, Mecocci P. Plasma susceptibility to free radical-induced antioxidant consumption and lipid peroxidation is increased in very old subjects with Alzheimer disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2002;4(6):517-22.

- Jeromson S, Gallagher IJ, Galloway SD, Hamilton DL. Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Skeletal Muscle Health. Mar Drugs. 2015;13(11):6977-7004.

- Smith GI, Julliand S, Reeds DN, Sinacore DR, Klein S, Mittendorfer B. Fish oil-derived n-3 PUFA therapy increases muscle mass and function in healthy older adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102(1):115-22.

- Smith GI, Atherton P, Reeds DN, Mohammed BS, Rankin D, Rennie MJ, et al. Dietary omega-3 fatty acid supplementation increases the rate of muscle protein synthesis in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(2):402-12.

- Dupont J, Dedeyne L, Dalle S, Koppo K, Gielen E. The role of omega-3 in the prevention and treatment of sarcopenia. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2019;31(6):825-36.

- Soininen H, Solomon A, Visser PJ, Hendrix SB, Blennow K, Kivipelto M, et al. 36-month LipiDiDiet multinutrient clinical trial in prodromal Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(1):29-40.

- Wurtman, RJ. A Nutrient Combination that Can Affect Synapse Formation. Nutrients. 2014;6(4):1701-10.

- Rossato LT, Schoenfeld BJ, de Oliveira EP. Is there sufficient evidence to supplement omega-3 fatty acids to increase muscle mass and strength in young and older adults? Clin Nutr. 2020;39(1):23-32.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).