Submitted:

03 December 2025

Posted:

05 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. MECP2: Molecular Biology, Isoforms, and Genetics

2.1. Gene Structure, Isoforms, and Transcriptional Regulation

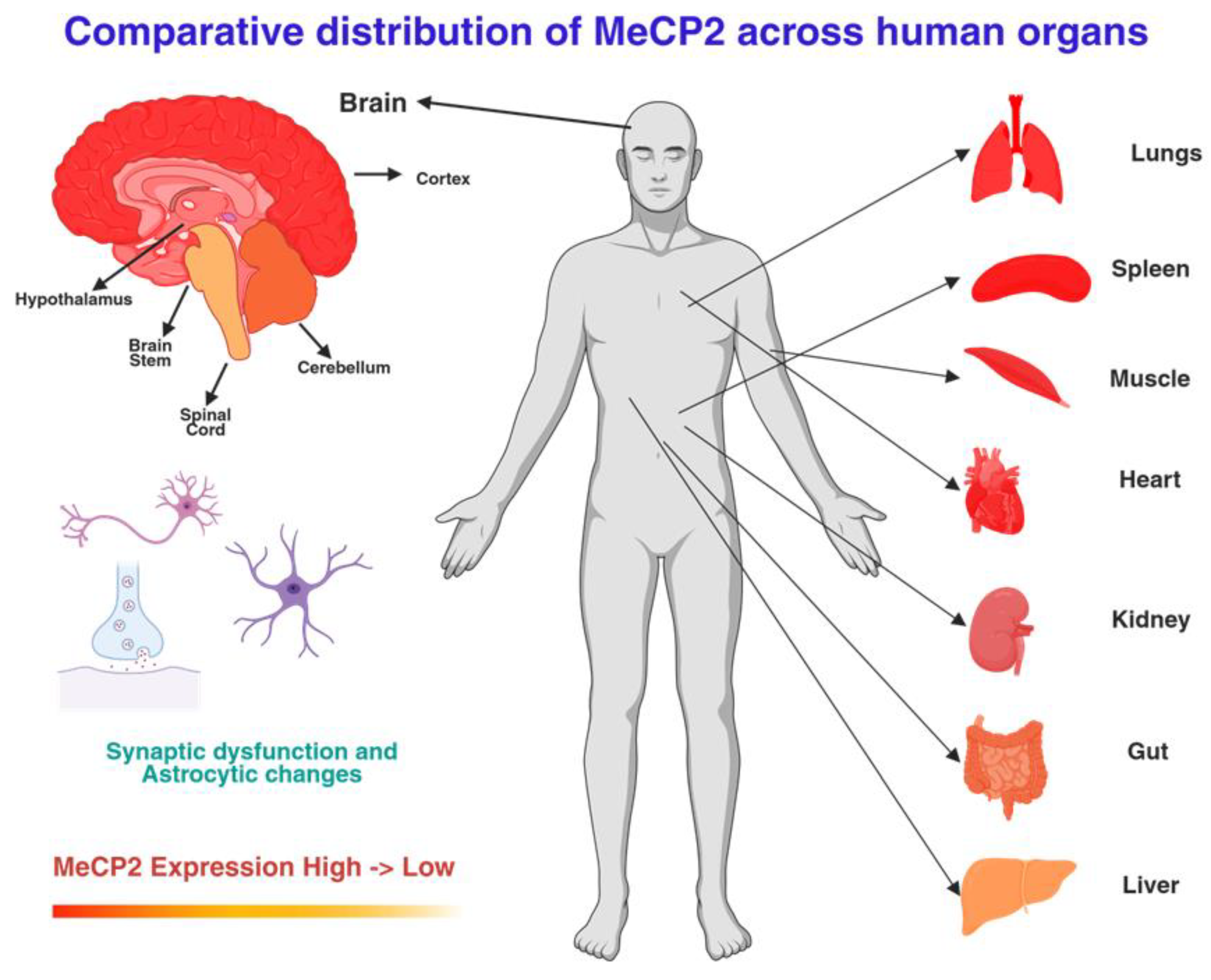

2.2. Expression Patterns and Systemic Role

2.3. Functional Role and Dosage Sensitivity

2.4. MECP2 Mutations and Genotype–Phenotype Correlations

2.5. Preclinical Insights and Therapeutic Implications

3. Central Nervous System Phenotype

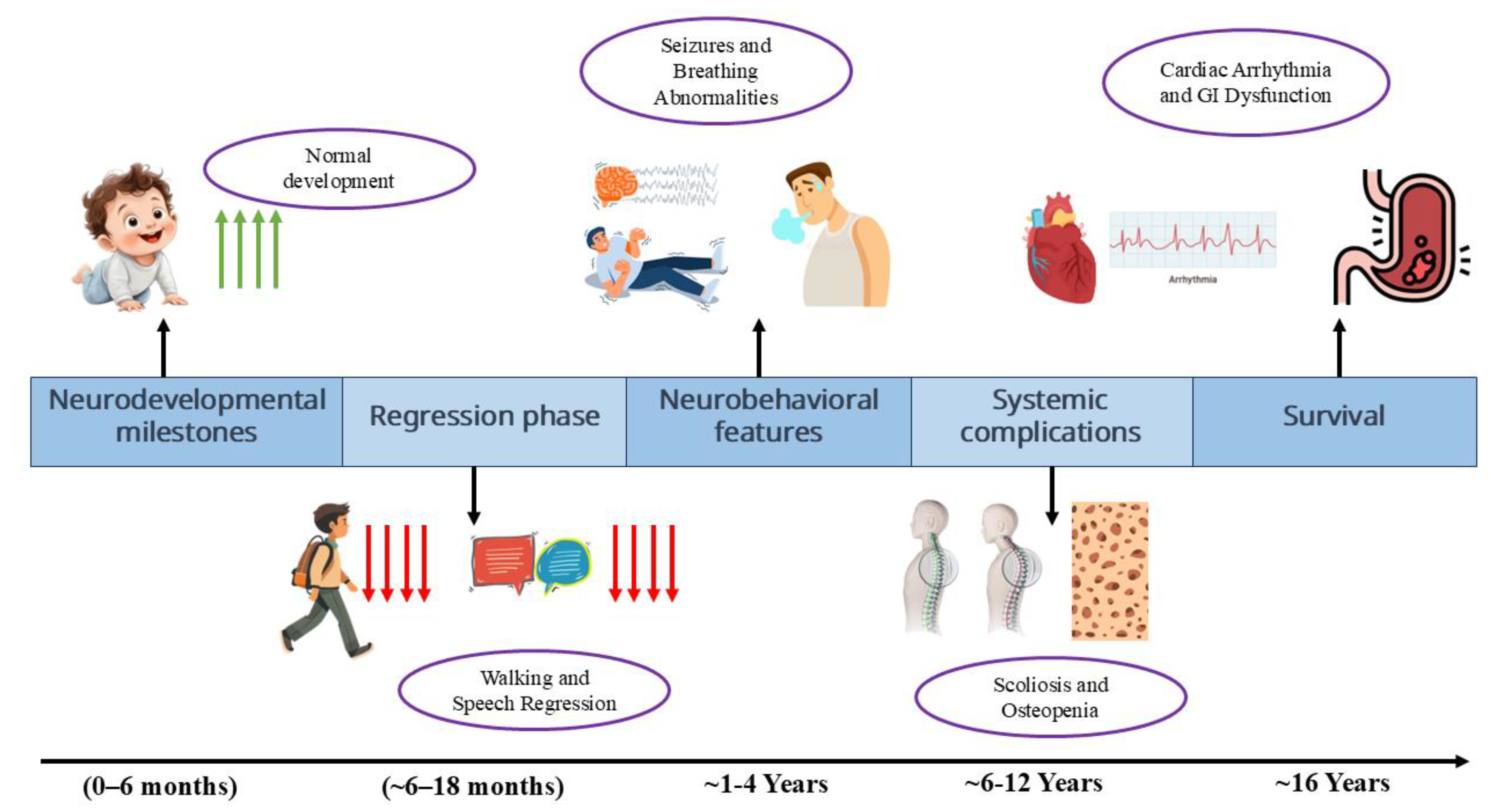

3.1. Developmental Stages and Regression

3.2. Stage I: Early Onset / Developmental Arrest (6–18 months)

3.3. Stage II: Rapid Progressive / Regression (1–4 years)

3.4. Stage III: Plateau / Pseudo-Stationary (2–10 years, extending into preadolescence)

3.5. Stage IV: Late Motor Deterioration (Post-10 years)

3.6. Seizures and Electroencephalography

3.7. Neuroimaging and Brain Structure

3.8. Behavioral Features and Communication

3.9. Natural History Data and Clinical Insights

3.10. Summary of Clinical and CNS Phenotype

4. Beyond the Brain — System-by-System Pathophysiology & Clinical Manifestations

4.1. Respiratory Control & Breathing Irregularities

4.2. Cardiovascular System (Autonomic Dysfunction and Arrhythmia)

4.3. Gastrointestinal System & Nutrition

4.4. Skeletal & Musculoskeletal System

4.5. Metabolic & Mitochondrial Dysfunction

4.6. Immune System & Glial/Peripheral Immune Interactions

4.7. Endocrine & Growth / Reproductive Health

4.8. Sleep, Sensory Systems & Pain

4.9. Oral/Dental & Dental Health

4.10. Other Organ Systems (Renal, Dermatologic, Ophthalmologic)

5. Biomarkers, Outcome Measures, and Trial Endpoints

6. Models and Mechanistic Tools (Preclinical & Translational Platforms)

6.1. Rodent Models of RTT

6.2. Human Cell-Based Models

6.3. Molecular and Multi-Omic Insights

6.4. Comparative Strengths and Limitations of Models

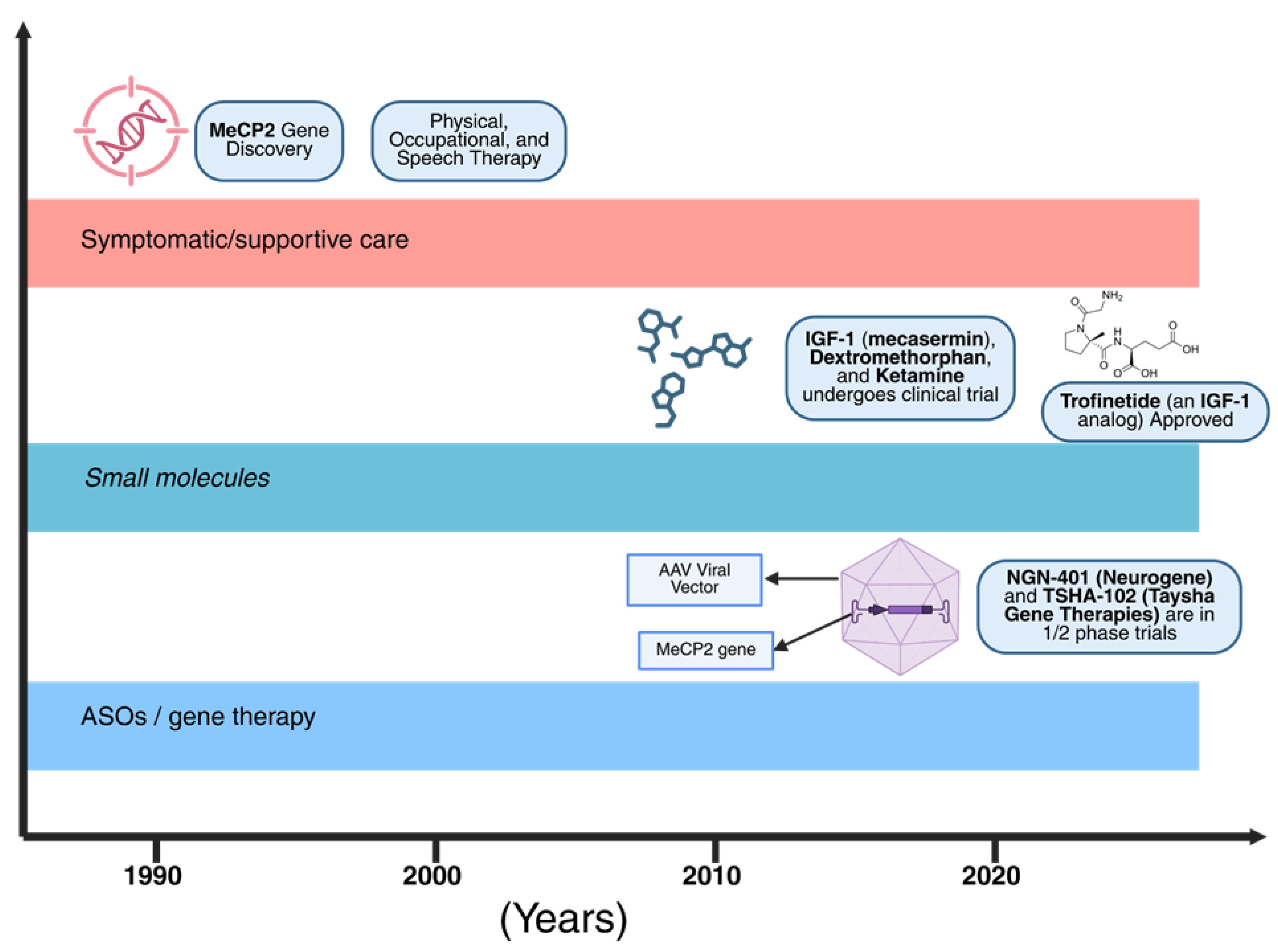

7. Therapeutic Landscape: Symptom Control to Disease Modification

7.1. Standard Supportive Care

7.2. Approved Pharmacotherapy: Trofinetide (DAYBUE™)

7.3. Gene Replacement / Gene Therapy

7.4. Antisense Oligonucleotides and Dosage Normalization

7.5. Small Molecules, Neurotrophic Strategies, and Repurposing

7.6. Cellular and Other Novel Strategies

7.7. Clinical Trial Design and Operational Considerations

8. Safety & Regulatory Considerations

9. Quality of Life, Caregiver Burden, and Health-Services Issues

10. Global Health, Equity & Access to Specialized Care

11. Gaps, Controversies & Prioritized Research Agenda

12. Conclusions

13. Declaration

13.1. Funding

13.1. Authorship Contribution Statement

13.1. Declaration of Competing Interest

13.1. Acknowledgement

13.1. Ethical Statements

13.1. Declaration of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing Process

References

- Bricker K, Vaughn BV. Rett syndrome: a review of clinical manifestations and therapeutic approaches. Front Sleep [Internet]. 2024 May 21 [cited 2025 Sep 3];3. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/sleep/articles/10.3389/frsle.2024.1373489/full.

- Kyle SM, Vashi N, Justice MJ. Rett syndrome: a neurological disorder with metabolic components. Open Biol. 2018 Feb;8(2):170216. [CrossRef]

- May D, Kponee-Shovein K, Neul JL, Percy AK, Mahendran M, Downes N, Chen G, Watson T, Pichard DC, Kennedy M, Lefebvre P. Characterizing the journey of Rett syndrome among females in the United States: a real-world evidence study using the Rett syndrome natural history study database. J Neurodev Disord. 2024 Jul 26;16(1):42. [CrossRef]

- Pejhan S, Rastegar M. Role of DNA Methyl-CpG-Binding Protein MeCP2 in Rett Syndrome Pathobiology and Mechanism of Disease. Biomolecules. 2021 Jan 8;11(1):75. [CrossRef]

- Gold WA, Percy AK, Neul JL, Cobb SR, Pozzo-Miller L, Issar JK, Ben-Zeev B, Vignoli A, Kaufmann WE. Rett syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2024 Nov 7;10(1):84.

- Carvalho MR de, Cavalcante TT, Oliveira PS, Naves PVF, Cunha PEL. Rett syndrome due to mutation in the MECP2 gene and electroencephalographic findings. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2024 Aug;82(8):1–2.

- Ribeiro MC, MacDonald JL. Sex differences in Mecp2-mutant Rett syndrome model mice and the impact of cellular mosaicism in phenotype development. Brain Res. 2020 Feb 15;1729:146644. [CrossRef]

- Buchanan CB, Stallworth JL, Scott AE, Glaze DG, Lane JB, Skinner SA, Tierney AE, Percy AK, Neul JL, Kaufmann WE. Behavioral profiles in Rett syndrome: Data from the natural history study. Brain Dev. 2019 Feb 1;41(2):123–34. [CrossRef]

- Percy AK, Benke TA, Marsh ED, Neul JL. Rett syndrome: The Natural History Study journey. Ann Child Neurol Soc. 2024;2(3):189–205.

- Chin EWM, Goh ELK. MeCP2 Dysfunction in Rett Syndrome and Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Methods Mol Biol Clifton NJ. 2019;2011:573–91.

- Vidal S, Xiol C, Pascual-Alonso A, O’Callaghan M, Pineda M, Armstrong J. Genetic Landscape of Rett Syndrome Spectrum: Improvements and Challenges. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Aug 12;20(16):3925. [CrossRef]

- Fang X, Baggett LM, Caylor RC, Percy AK, Neul JL, Lane JB, Glaze DG, Benke TA, Marsh ED, Motil KJ, Barrish JO, Annese FE, Skinner SA. Parental age effects and Rett syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2024 Feb;194(2):160–73. [CrossRef]

- Kim JA, Kwon WK, Kim JW, Jang JH. Variation spectrum of MECP2 in Korean patients with Rett and Rett-like syndrome: a literature review and reevaluation of variants based on the ClinGen guideline. J Hum Genet. 2022 Oct;67(10):601–6.

- Ip JPK, Mellios N, Sur M. Rett syndrome: insights into genetic, molecular and circuit mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018 Jun;19(6):368–82. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Flamier A, Bell GW, Diao AJ, Whitfield TW, Wang HC, Wu Y, Schulte F, Friesen M, Guo R, Mitalipova M, Liu XS, Vos SM, Young RA, Jaenisch R. MECP2 directly interacts with RNA polymerase II to modulate transcription in human neurons. Neuron. 2024 Jun 19;112(12):1943-1958.e10. [CrossRef]

- Ali NE, Tariq N, Naz G, Abalkhail A, Kausar T, Mazhar I, Zia S, Aqib AI, Khan NU. Rett syndrome: advances in Understanding MeCP2 function, potential gene therapies, and public health implications. Mol Biol Rep. 2025 Jul 8;52(1):687.

- Golubiani G, van Agen L, Tsverava L, Solomonia R, Müller M. Mitochondrial Proteome Changes in Rett Syndrome. Biology. 2023 Jul 3;12(7):956.

- Pascual-Alonso A, Xiol C, Smirnov D, Kopajtich R, Prokisch H, Armstrong J. Identification of molecular signatures and pathways involved in Rett syndrome using a multi-omics approach. Hum Genomics. 2023 Sep 15;17(1):85. [CrossRef]

- Qian J, Guan X, Xie B, Xu C, Niu J, Tang X, Li CH, Colecraft HM, Jaenisch R, Liu XS. Multiplex epigenome editing of MECP2 to rescue Rett syndrome neurons. Sci Transl Med. 2023 Jan 18;15(679):eadd4666.

- Collins BE, Neul JL. Rett Syndrome and MECP2 Duplication Syndrome: Disorders of MeCP2 Dosage. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2022;18:2813–35.

- Zahorakova D, Lelkova P, Gregor V, Magner M, Zeman J, Martasek P. MECP2 mutations in Czech patients with Rett syndrome and Rett-like phenotypes: novel mutations, genotype-phenotype correlations and validation of high-resolution melting analysis for mutation scanning. J Hum Genet. 2016 Jul;61(7):617–25. [CrossRef]

- Abo Zeid M, Elrosasy A, Mohamed RG, Ghazou A, Goufa E, Hassan N, Abuzaid Y. A meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of trofinetide in patients with rett syndrome. Neurol Sci Off J Ital Neurol Soc Ital Soc Clin Neurophysiol. 2024 Oct;45(10):4767–78.

- Lou S, DJiake Tihagam R, Wasko UN, Equbal Z, Venkatesan S, Braczyk K, Przanowski P, Il Koo B, Saltani I, Singh AT, Likhite S, Powers S, Souza GMPR, Maxwell RA, Yu J, Zhu LJ, Beenhakker M, Abbott SBG, Lu Z, Green MR, Meyer KC, Tushir-Singh J, Bhatnagar S. Targeting microRNA-dependent control of X chromosome inactivation improves the Rett Syndrome phenotype. Nat Commun. 2025 Jul 4;16(1):6169. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi S, Takeguchi R, Kuroda M, Tanaka R. Atypical Rett syndrome in a girl with mosaic triple X and MECP2 variant. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2020 Mar;8(3):e1122. [CrossRef]

- Collins BE, Merritt JK, Erickson KR, Neul JL. Safety and efficacy of genetic MECP2 supplementation in the R294X mouse model of Rett syndrome. Genes Brain Behav. 2022 Jan;21(1):e12739.

- Powers S, Likhite S, Gadalla KK, Miranda CJ, Huffenberger AJ, Dennys C, Foust KD, Morales P, Pierson CR, Rinaldi F, Perry S, Bolon B, Wein N, Cobb S, Kaspar BK, Meyer KC. Novel MECP2 gene therapy is effective in a multicenter study using two mouse models of Rett syndrome and is safe in non-human primates. Mol Ther J Am Soc Gene Ther. 2023 Sep 6;31(9):2767–82. [CrossRef]

- Akaba Y, Takahashi S. MECP2 duplication syndrome: Recent advances in pathophysiology and therapeutic perspectives. Brain Dev. 2025 Aug;47(4):104371.

- Chen X, Han X, Blanchi B, Guan W, Ge W, Yu YC, Sun YE. Graded and pan-neural disease phenotypes of Rett Syndrome linked with dosage of functional MeCP2. Protein Cell. 2021 Aug;12(8):639–52.

- Haase F, Gloss BS, Tam PPL, Gold WA. WGCNA Identifies Translational and Proteasome-Ubiquitin Dysfunction in Rett Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Sep 15;22(18):9954. [CrossRef]

- Anitha A, Poovathinal SA, Viswambharan V, Thanseem I, Iype M, Anoop U, Sumitha PS, Parakkal R, Vasu MM. MECP2 Mutations in the Rett Syndrome Patients from South India. Neurol India. 2022;70(1):249–53. [CrossRef]

- Chin EWM, Goh ELK. Behavioral Characterization of MeCP2 Dysfunction-Associated Rett Syndrome and Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Methods Mol Biol Clifton NJ. 2019;2011:593–605.

- Li Y, Anderson AG, Qi G, Wu SR, Revelli JP, Liu Z, Zoghbi HY. Early transcriptional signatures of MeCP2 positive and negative cells in Rett syndrome. BioRxiv Prepr Serv Biol. 2025 Jun 26;2025.06.26.661761.

- Müller M. Disturbed redox homeostasis and oxidative stress: Potential players in the developmental regression in Rett syndrome. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019 Mar;98:154–63. [CrossRef]

- Chin Wong L, Hung PL, Jan TY, Lee WT, Taiwan Rett Syndrome Association. Variations of stereotypies in individuals with Rett syndrome: A nationwide cross-sectional study in Taiwan. Autism Res Off J Int Soc Autism Res. 2017 Jul;10(7):1204–14.

- Lazek R, Karoum A, Fathalla W. Genotype-Phenotype Correlation and Therapeutic Amenability in a Cohort of Rett Syndrome Patients: A Single-Center Study. Cureus. 2025 Jun;17(6):e86953.

- Zhou J, Cattoglio C, Shao Y, Tirumala HP, Vetralla C, Bajikar SS, Li Y, Chen H, Wang Q, Wu Z, Tang B, Zahabiyon M, Bajic A, Meng X, Ferrie JJ, LaGrone A, Zhang P, Kim JJ, Tang J, Liu Z, Darzacq X, Heintz N, Tjian R, Zoghbi HY. A novel pathogenic mutation of MeCP2 impairs chromatin association independent of protein levels. Genes Dev. 2023 Oct 1;37(19–20):883–900. [CrossRef]

- Bahram Sangani N, Koetsier J, Gomes AR, Diogo MM, Fernandes TG, Bouwman FG, Mariman ECM, Ghazvini M, Gribnau J, Curfs LMG, Reutelingsperger CP, Eijssen LMT. Involvement of extracellular vesicle microRNA clusters in developing healthy and Rett syndrome brain organoids. Cell Mol Life Sci CMLS. 2024 Sep 21;81(1):410.

- Lopes AG, Loganathan SK, Caliaperumal J. Rett Syndrome and the Role of MECP2: Signaling to Clinical Trials. Brain Sci. 2024 Jan 24;14(2):120. [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Alonso A, Martínez-Monseny AF, Xiol C, Armstrong J. MECP2-Related Disorders in Males. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Sep 4;22(17):9610. [CrossRef]

- Shiohama T, Tsujimura K. Quantitative Structural Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging Analyses: Methodological Overview and Application to Rett Syndrome. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:835964. [CrossRef]

- Kong Y, Li QB, Yuan ZH, Jiang XF, Zhang GQ, Cheng N, Dang N. Multimodal Neuroimaging in Rett Syndrome With MECP2 Mutation. Front Neurol. 2022;13:838206.

- Buchanan CB, Stallworth JL, Joy AE, Dixon RE, Scott AE, Beisang AA, Benke TA, Glaze DG, Haas RH, Heydemann PT, Jones MD, Lane JB, Lieberman DN, Marsh ED, Neul JL, Peters SU, Ryther RC, Skinner SA, Standridge SM, Kaufmann WE, Percy AK. Anxiety-like behavior and anxiolytic treatment in the Rett syndrome natural history study. J Neurodev Disord. 2022 May 14;14(1):31. [CrossRef]

- Stallworth JL, Dy ME, Buchanan CB, Chen CF, Scott AE, Glaze DG, Lane JB, Lieberman DN, Oberman LM, Skinner SA, Tierney AE, Cutter GR, Percy AK, Neul JL, Kaufmann WE. Hand stereotypies: Lessons from the Rett Syndrome Natural History Study. Neurology. 2019 May 28;92(22):e2594–603.

- Vilvarajan S, McDonald M, Douglas L, Newham J, Kirkland R, Tzannes G, Tay D, Christodoulou J, Thompson S, Ellaway C. Multidisciplinary Management of Rett Syndrome: Twenty Years’ Experience. Genes. 2023 Aug 11;14(8):1607.

- Andoh-Noda T, Inouye MO, Miyake K, Kubota T, Okano H, Akamatsu W. Modeling Rett Syndrome Using Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2016;15(5):544–50. [CrossRef]

- Parent H, Ferranti A, Niswender C. Trofinetide: a pioneering treatment for Rett syndrome. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2023 Oct;44(10):740–1.

- Sweatt JD, Tamminga CA. An epigenomics approach to individual differences and its translation to neuropsychiatric conditions. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2016 Sep;18(3):289–98. [CrossRef]

- Vogel Ciernia A, Yasui DH, Pride MC, Durbin-Johnson B, Noronha AB, Chang A, Knotts TA, Rutkowsky JR, Ramsey JJ, Crawley JN, LaSalle JM. MeCP2 isoform e1 mutant mice recapitulate motor and metabolic phenotypes of Rett syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2018 Dec 1;27(23):4077–93.

- Marano D, Fioriniello S, D’Esposito M, Della Ragione F. Transcriptomic and Epigenomic Landscape in Rett Syndrome. Biomolecules. 2021 Jun 30;11(7):967. [CrossRef]

- Sandweiss AJ, Brandt VL, Zoghbi HY. Advances in understanding of Rett syndrome and MECP2 duplication syndrome: prospects for future therapies. Lancet Neurol. 2020 Aug;19(8):689–98.

- Haase FD, Coorey B, Riley L, Cantrill LC, Tam PPL, Gold WA. Pre-clinical Investigation of Rett Syndrome Using Human Stem Cell-Based Disease Models. Front Neurosci. 2021;15:698812.

- Pramanik S, Bala A, Pradhan A. Zebrafish in understanding molecular pathophysiology, disease modeling, and developing effective treatments for Rett syndrome. J Gene Med. 2024 Feb;26(2):e3677.

- MacKay J, Leonard H, Wong K, Wilson A, Downs J. Respiratory morbidity in Rett syndrome: an observational study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018 Sep;60(9):951–7. [CrossRef]

- Rashid N, Darer JD, Ruetsch C, Yang X. Aspiration, respiratory complications, and associated healthcare resource utilization among individuals with Rett syndrome. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2025 May 15;20(1):232.

- Crosson J, Srivastava S, Bibat GM, Gupta S, Kantipuly A, Smith-Hicks C, Myers SM, Sanyal A, Yenokyan G, Brenner J, Naidu SR. Evaluation of QTc in Rett syndrome: Correlation with age, severity, and genotype. Am J Med Genet A. 2017 Jun;173(6):1495–501.

- Rodrigues GD, Cordani R, Veneruso M, Chiarella L, Prato G, Ferri R, Carandina A, Tobaldini E, Nobili L, Montano N. Predominant cardiac sympathetic modulation during wake and sleep in patients with Rett syndrome. Sleep Med. 2024 Jul;119:188–91. [CrossRef]

- Meyyazhagan A, Balasubramanian B, Kathannan S, Alagamuthu KK, Easwaran M, Shanmugam S, Pappusamy M, Bhotla HK, Mustaqahamed S, Arumugam VA, Kaul T, Keshavarao S. Scrutinizing the molecular, biochemical, and cytogenetic attributes in subjects with Rett syndrome (RTT) and their mothers. Epilepsy Behav EB. 2020 Oct;111:107277.

- Singh J, Lanzarini E, Santosh P. Autonomic dysfunction and sudden death in patients with Rett syndrome: a systematic review. J Psychiatry Neurosci JPN. 2020 May 1;45(3):150–81. [CrossRef]

- Berger TD, Fogel Berger C, Gara S, Ben-Zeev B, Weiss B. Nutritional and gastrointestinal manifestations in Rett syndrome: long-term follow-up. Eur J Pediatr. 2024 Sep;183(9):4085–91.

- Caputi V, Hill L, Figueiredo M, Popov J, Hartung E, Margolis KG, Baskaran K, Joharapurkar P, Moshkovich M, Pai N. Functional contribution of the intestinal microbiome in autism spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and Rett syndrome: a systematic review of pediatric and adult studies. Front Neurosci. 2024;18:1341656. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Yang Q, Liu X. The microbiota-gut-brain axis and neurodevelopmental disorders. Protein Cell. 2023 Oct 25;14(10):762–75.

- Borghi E, Vignoli A. Rett Syndrome and Other Neurodevelopmental Disorders Share Common Changes in Gut Microbial Community: A Descriptive Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Aug 26;20(17):4160. [CrossRef]

- Downs J, Wong K, Leonard H. Associations between genotype, phenotype and behaviours measured by the Rett syndrome behaviour questionnaire in Rett syndrome. J Neurodev Disord. 2024 Oct 25;16(1):59.

- Moore R, Poulsen J, Reardon L, Samples-Morris C, Simmons H, Ramsey KM, Whatley ML, Lane JB. Managing Gastrointestinal Symptoms Resulting from Treatment with Trofinetide for Rett Syndrome: Caregiver and Nurse Perspectives. Adv Ther. 2024 Apr;41(4):1305–17.

- Motil KJ, Beisang A, Smith-Hicks C, Lembo A, Standridge SM, Liu E. Recommendations for the management of gastrointestinal comorbidities with or without trofinetide use in Rett syndrome. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Jun;18(6):227–37. [CrossRef]

- Borloz E, Villard L, Roux JC. Rett syndrome: think outside the (skull) box. Fac Rev. 2021;10:59.

- Singh J, Fiori F, Law ML, Ahmed R, Ameenpur S, Basheer S, Chishti S, Lawrence R, Mastroianni M, Mosaddegh A, Santosh P. Development and Psychometric Properties of the Multi-System Profile of Symptoms Scale in Patients with Rett Syndrome. J Clin Med. 2022 Aug 30;11(17):5094. [CrossRef]

- Y L, R G, R J. Rett Syndrome: Thinking Beyond Brain Borders. Adv Exp Med Biol [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 3];1477. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40442389/.

- Wang W, Li H, Xiao M, Mu M, Xu H, Wang B. Clinical Research on Rett Syndrome: Central Hypoxemia and Hypokalemic Metabolic Alkalosis. Altern Ther Health Med. 2024 Jan;30(1):167–71.

- Zlatic SA, Duong D, Gadalla KKE, Murage B, Ping L, Shah R, Fink JJ, Khwaja O, Swanson LC, Sahin M, Rayaprolu S, Kumar P, Rangaraju S, Bird A, Tarquinio D, Carpenter R, Cobb S, Faundez V. Convergent cerebrospinal fluid proteomes and metabolic ontologies in humans and animal models of Rett syndrome. iScience. 2022 Sep 16;25(9):104966. [CrossRef]

- A V, V C, A P, G V. Ox-inflammasome involvement in neuroinflammation. Free Radic Biol Med [Internet]. 2023 Oct [cited 2025 Sep 3];207. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37442280/.

- Gonçalez JL, Shen J, Li W. Molecular Mechanisms of Rett Syndrome: Emphasizing the Roles of Monoamine, Immunity, and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Cells. 2024 Dec 17;13(24):2077.

- Das DK, Raha S, Sanghavi D, Maitra A, Udani V. Spectrum of MECP2 gene mutations in a cohort of Indian patients with Rett syndrome: report of two novel mutations. Gene. 2013 Feb 15;515(1):78–83. [CrossRef]

- Zepeda-Mendoza CJ, Bardon A, Kammin T, Harris DJ, Cox H, Redin C, Ordulu Z, Talkowski ME, Morton CC. Phenotypic interpretation of complex chromosomal rearrangements informed by nucleotide-level resolution and structural organization of chromatin. Eur J Hum Genet EJHG. 2018 Mar;26(3):374–81.

- Huang CH, Wong LC, Chu YJ, Hsu CJ, Wang HP, Tsai WC, Lee WT. The sleep problems in individuals with Rett syndrome and their caregivers. Autism Int J Res Pract. 2024 Dec;28(12):3118–30. [CrossRef]

- Kay C, Leonard H, Smith J, Wong K, Downs J. Genotype and sleep independently predict mental health in Rett syndrome: an observational study. J Med Genet. 2023 Oct;60(10):951–9. [CrossRef]

- Tascini G, Dell’Isola GB, Mencaroni E, Di Cara G, Striano P, Verrotti A. Sleep Disorders in Rett Syndrome and Rett-Related Disorders: A Narrative Review. Front Neurol. 2022;13:817195.

- Lai YYL, Downs J, Zafar S, Wong K, Walsh L, Leonard H. Oral health care and service utilisation in individuals with Rett syndrome: an international cross-sectional study. J Intellect Disabil Res JIDR. 2021 Jun;65(6):561–76. [CrossRef]

- Neul JL, Percy AK, Benke TA, Berry-Kravis EM, Glaze DG, Marsh ED, Lin T, Stankovic S, Bishop KM, Youakim JM. Trofinetide for the treatment of Rett syndrome: a randomized phase 3 study. Nat Med. 2023 Jun;29(6):1468–75.

- Hirano D, Goto Y, Shoji H, Taniguchi T. Relationship between hand stereotypies and purposeful hand use and factors causing skin injuries and joint contractures in individuals with Rett syndrome. Early Hum Dev. 2023 Aug;183:105821. [CrossRef]

- Zhang E, Zhao T, Sikora T, Ellaway C, Gold WA, Van Bergen NJ, Stroud DA, Christodoulou J, Kaur S. CHD8 Variant and Rett Syndrome: Overlapping Phenotypes, Molecular Convergence, and Expanding the Genetic Spectrum. Hum Mutat. 2025;2025:5485987.

- Migovich M, Ullal A, Fu C, Peters SU, Sarkar N. Feasibility of wearable devices and machine learning for sleep classification in children with Rett syndrome: A pilot study. Digit Health. 2023;9:20552076231191622. [CrossRef]

- Wandin H, Lindberg P, Sonnander K. Aided language modelling, responsive communication and eye-gaze technology as communication intervention for adults with Rett syndrome: three experimental single case studies. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2023 Oct;18(7):1011–25.

- Monteiro-Fernandes D, Charles I, Guerreiro S, Cunha-Garcia D, Pereira-Sousa J, Oliveira S, Teixeira-Castro A, Varney MA, Kleven MS, Newman-Tancredi A, P Sheikh Abdala A, Duarte-Silva S, Maciel P. Rescue of respiratory and cognitive impairments in Rett Syndrome mice using NLX-101, a selective 5-HT1A receptor biased agonist. Biomed Pharmacother Biomedecine Pharmacother. 2025 May;186:117989.

- Cordone V. Biochemical and molecular determinants of the subclinical inflammatory mechanisms in Rett syndrome. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2024 Jul;757:110046. [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann WE, Oberman LM, Downs J, Leonard H, Barnes KV. Rett Syndrome Behaviour Questionnaire: Variability of Scores and Related Factors. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2025 Feb 5; [CrossRef]

- Percy AK, Neul JL, Benke TA, Marsh ED, Glaze DG. A review of the Rett Syndrome Behaviour Questionnaire and its utilization in the assessment of symptoms associated with Rett syndrome. Front Pediatr. 2023;11:1229553.

- Neul JL, Percy AK, Benke TA, Berry-Kravis EM, Glaze DG, Peters SU, Jones NE, Youakim JM. Design and outcome measures of LAVENDER, a phase 3 study of trofinetide for Rett syndrome. Contemp Clin Trials. 2022 Mar;114:106704. [CrossRef]

- Oberman LM, Leonard H, Downs J, Cianfaglione R, Stahlhut M, Larsen JL, Madden KV, Kaufmann WE. Rett Syndrome Behaviour Questionnaire in Children and Adults With Rett Syndrome: Psychometric Characterization and Revised Factor Structure. Am J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2023 May 1;128(3):237–53. [CrossRef]

- Cohen SR, Helbig I, Kaufman MC, Schust Myers L, Conway L, Helbig KL. Caregiver assessment of quality of life in individuals with genetic developmental and epileptic encephalopathies. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2022 Aug;64(8):957–64.

- Killian JT, Lane JB, Lee HS, Pelham JH, Skinner SA, Kaufmann WE, Glaze DG, Neul JL, Percy AK. Caretaker Quality of Life in Rett Syndrome: Disorder Features and Psychological Predictors. Pediatr Neurol. 2016 May;58:67–74.

- McGraw SA, Smith-Hicks C, Nutter J, Henne JC, Abler V. Meaningful Improvements in Rett Syndrome: A Qualitative Study of Caregivers. J Child Neurol. 2023 Apr;38(5):270–82.

- Bajikar SS, Zhou J, O’Hara R, Tirumala HP, Durham MA, Trostle AJ, Dias M, Shao Y, Chen H, Wang W, Yalamanchili HK, Wan YW, Banaszynski LA, Liu Z, Zoghbi HY. Acute MeCP2 loss in adult mice reveals transcriptional and chromatin changes that precede neurological dysfunction and inform pathogenesis. Neuron. 2025 Feb 5;113(3):380-395.e8. [CrossRef]

- Ito-Ishida A, Ure K, Chen H, Swann JW, Zoghbi HY. Loss of MeCP2 in Parvalbumin-and Somatostatin-Expressing Neurons in Mice Leads to Distinct Rett Syndrome-like Phenotypes. Neuron. 2015 Nov 18;88(4):651–8.

- Sadhu C, Lyons C, Oh J, Jagadeeswaran I, Gray SJ, Sinnett SE. The Efficacy of a Human-Ready miniMECP2 Gene Therapy in a Pre-Clinical Model of Rett Syndrome. Genes. 2023 Dec 24;15(1):31.

- Yang K, Li T, Geng Y, Zhang R, Xu Z, Wu J, Yuan Y, Zhang Y, Qiu Z, Li F. Protocol for the neonatal intracerebroventricular delivery of adeno-associated viral vectors for brain restoration of MECP2 for Rett syndrome. STAR Protoc. 2024 Dec 20;5(4):103344. [CrossRef]

- Gomathi M, Balachandar V. Novel therapeutic approaches: Rett syndrome and human induced pluripotent stem cell technology. Stem Cell Investig. 2017;4:20.

- Huber A, Sarne V, Beribisky AV, Ackerbauer D, Derdak S, Madritsch S, Etzler J, Huck S, Scholze P, Gorgulu I, Christodoulou J, Studenik CR, Neuhaus W, Connor B, Laccone F, Steinkellner H. Generation and Characterization of a Human Neuronal In Vitro Model for Rett Syndrome Using a Direct Reprogramming Method. Stem Cells Dev. 2024 Mar;33(5–6):128–42. [CrossRef]

- Samarasinghe RA, Miranda OA, Buth JE, Mitchell S, Ferando I, Watanabe M, Allison TF, Kurdian A, Fotion NN, Gandal MJ, Golshani P, Plath K, Lowry WE, Parent JM, Mody I, Novitch BG. Identification of neural oscillations and epileptiform changes in human brain organoids. Nat Neurosci. 2021 Oct;24(10):1488–500.

- Gomes AR, Fernandes TG, Vaz SH, Silva TP, Bekman EP, Xapelli S, Duarte S, Ghazvini M, Gribnau J, Muotri AR, Trujillo CA, Sebastião AM, Cabral JMS, Diogo MM. Modeling Rett Syndrome With Human Patient-Specific Forebrain Organoids. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:610427.

- Mok RSF, Zhang W, Sheikh TI, Pradeepan K, Fernandes IR, DeJong LC, Benigno G, Hildebrandt MR, Mufteev M, Rodrigues DC, Wei W, Piekna A, Liu J, Muotri AR, Vincent JB, Muller L, Martinez-Trujillo J, Salter MW, Ellis J. Wide spectrum of neuronal and network phenotypes in human stem cell-derived excitatory neurons with Rett syndrome-associated MECP2 mutations. Transl Psychiatry. 2022 Oct 18;12(1):450.

- Pradeepan KS, McCready FP, Wei W, Khaki M, Zhang W, Salter MW, Ellis J, Martinez-Trujillo J. Calcium-Dependent Hyperexcitability in Human Stem Cell-Derived Rett Syndrome Neuronal Networks. Biol Psychiatry Glob Open Sci. 2024 Mar;4(2):100290. [CrossRef]

- Aldosary M, Al-Bakheet A, Al-Dhalaan H, Almass R, Alsagob M, Al-Younes B, AlQuait L, Mustafa OM, Bulbul M, Rahbeeni Z, Alfadhel M, Chedrawi A, Al-Hassnan Z, AlDosari M, Al-Zaidan H, Al-Muhaizea MA, AlSayed MD, Salih MA, AlShammari M, Faiyaz-Ul-Haque M, Chishti MA, Al-Harazi O, Al-Odaib A, Kaya N, Colak D. Rett Syndrome, a Neurodevelopmental Disorder, Whole-Transcriptome, and Mitochondrial Genome Multiomics Analyses Identify Novel Variations and Disease Pathways. Omics J Integr Biol. 2020 Mar;24(3):160–71.

- Karaosmanoglu B, Imren G, Ozisin MS, Reçber T, Simsek Kiper PO, Haliloglu G, Alikaşifoğlu M, Nemutlu E, Taskiran EZ, Utine GE. Ex vivo disease modelling of Rett syndrome: the transcriptomic and metabolomic implications of direct neuronal conversion. Mol Biol Rep. 2024 Sep 13;51(1):979. [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Alonso A, Xiol C, Smirnov D, Kopajtich R, Prokisch H, Armstrong J. Multi-omics in MECP2 duplication syndrome patients and carriers. Eur J Neurosci. 2024 Jul;60(2):4004–18.

- Baroncelli L, Auel S, Rinne L, Schuster AK, Brand V, Kempkes B, Dietrich K, Müller M. Oral Feeding of an Antioxidant Cocktail as a Therapeutic Strategy in a Mouse Model of Rett Syndrome: Merits and Limitations of Long-Term Treatment. Antioxid Basel Switz. 2022 Jul 20;11(7):1406.

- Panayotis N, Ehinger Y, Felix MS, Roux JC. State-of-the-art therapies for Rett syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2023 Feb;65(2):162–70.

- Persico AM, Ricciardello A, Cucinotta F. The psychopharmacology of autism spectrum disorder and Rett syndrome. Handb Clin Neurol. 2019;165:391–414.

- Kaufmann WE, Stallworth JL, Everman DB, Skinner SA. Neurobiologically-based treatments in Rett syndrome: opportunities and challenges. Expert Opin Orphan Drugs. 2016 Oct 2;4(10):1043–55.

- Percy AK, Neul JL, Benke TA, Berry-Kravis EM, Glaze DG, Marsh ED, An D, Bishop KM, Youakim JM. Trofinetide for the treatment of Rett syndrome: Results from the open-label extension LILAC study. Med N Y N. 2024 Sep 13;5(9):1178-1189.e3. [CrossRef]

- Singh A, Balasundaram MK, Gupta D. Trofinetide in Rett syndrome: A brief review of safety and efficacy. Intractable Rare Dis Res. 2023 Nov;12(4):262–6.

- Coorey B, Haase F, Ellaway C, Clarke A, Lisowski L, Gold WA. Gene Editing and Rett Syndrome: Does It Make the Cut? CRISPR J. 2022 Aug;5(4):490–9. [CrossRef]

- Fonzo M, Sirico F, Corrado B. Evidence-Based Physical Therapy for Individuals with Rett Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci. 2020 Jun 30;10(7):410.

- Saby JN, Peters SU, Roberts TPL, Nelson CA, Marsh ED. Evoked Potentials and EEG Analysis in Rett Syndrome and Related Developmental Encephalopathies: Towards a Biomarker for Translational Research. Front Integr Neurosci. 2020;14:30.

- Buckley N, Stahlhut M, Elefant C, Leonard H, Lotan M, Downs J. Parent and therapist perspectives on “uptime” activities and participation in Rett syndrome. Disabil Rehabil. 2022 Dec;44(24):7420–7. [CrossRef]

- Bajikar SS, Sztainberg Y, Trostle AJ, Tirumala HP, Wan YW, Harrop CL, Bengtsson JD, Carvalho CMB, Pehlivan D, Suter B, Neul JL, Liu Z, Jafar-Nejad P, Rigo F, Zoghbi HY. Modeling antisense oligonucleotide therapy in MECP2 duplication syndrome human iPSC-derived neurons reveals gene expression programs responsive to MeCP2 levels. Hum Mol Genet. 2024 Nov 8;33(22):1986–2001.

- Gogliotti RG, Senter RK, Rook JM, Ghoshal A, Zamorano R, Malosh C, Stauffer SR, Bridges TM, Bartolome JM, Daniels JS, Jones CK, Lindsley CW, Conn PJ, Niswender CM. mGlu5 positive allosteric modulation normalizes synaptic plasticity defects and motor phenotypes in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2016 May 15;25(10):1990–2004.

- Merritt JK, Fang X, Caylor RC, Skinner SA, Friez MJ, Percy AK, Neul JL. Normalized Clinical Severity Scores Reveal a Correlation between X Chromosome Inactivation and Disease Severity in Rett Syndrome. Genes. 2024 May 8;15(5):594. [CrossRef]

- Abbas A, Fayoud AM, El Din Moawad MH, Hamad AA, Hamouda H, Fouad EA. Safety and efficacy of trofinetide in Rett syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Pediatr. 2024 Mar 23;24(1):206.

- Cherchi C, Chiappini E, Amaddeo A, Chiarini Testa MB, Banfi P, Veneselli E, Cutrera R, panel for the Problems in Patients with Rett Syndrome. Management of respiratory issues in patients with Rett syndrome: Italian experts’ consensus using a Delphi approach. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2024 Jul;59(7):1970–8.

- Furley K, Mehra C, Goin-Kochel RP, Fahey MC, Hunter MF, Williams K, Absoud M. Developmental regression in children: Current and future directions. Cortex J Devoted Study Nerv Syst Behav. 2023 Dec;169:5–17.

- Xiol C, Vidal S, Pascual-Alonso A, Blasco L, Brandi N, Pacheco P, Gerotina E, O’Callaghan M, Pineda M, Armstrong J, Rett Working Group. X chromosome inactivation does not necessarily determine the severity of the phenotype in Rett syndrome patients. Sci Rep. 2019 Aug 19;9(1):11983.

- Lim J, Greenspoon D, Hunt A, McAdam L. Rehabilitation interventions in Rett syndrome: a scoping review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020 Aug;62(8):906–16.

- Downs J, Pichard DC, Kaufmann WE, Horrigan JP, Raspa M, Townend G, Marsh ED, Leonard H, Motil K, Dietz AC, Garg N, Ananth A, Byiers B, Peters S, Beatty C, Symons F, Jacobs A, Youakim J, Suter B, Santosh P, Neul JL, Benke TA. International workshop: what is needed to ensure outcome measures for Rett syndrome are fit-for-purpose for clinical trials? June 7, 2023, Nashville, USA. Trials. 2024 Dec 21;25(1):845. [CrossRef]

- Howell KB, White SM, McTague A, D’Gama AM, Costain G, Poduri A, Scheffer IE, Chau V, Smith LD, Stephenson SEM, Wojcik M, Davidson A, Sebire N, Sliz P, Beggs AH, Chitty LS, Cohn RD, Marshall CR, Andrews NC, North KN, Cross JH, Christodoulou J, Scherer SW. International Precision Child Health Partnership (IPCHiP): an initiative to accelerate discovery and improve outcomes in rare pediatric disease. NPJ Genomic Med. 2025 Feb 27;10(1):13. [CrossRef]

- Smith M, Arthur B, Cikowski J, Holt C, Gonzalez S, Fisher NM, Vermudez SAD, Lindsley CW, Niswender CM, Gogliotti RG. Clinical and Preclinical Evidence for M1 Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptor Potentiation as a Therapeutic Approach for Rett Syndrome. Neurother J Am Soc Exp Neurother. 2022 Jul;19(4):1340–52. [CrossRef]

| Mutation Type | Common Variants | Approximate frequency among classic MECP2 variants in RTT (%)—cohort-dependent | Phenotypic Severity | Associated Features | Recent Data | Inference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Missense | R106W, R133C, T158M | 40–50 | Moderate to Severe | Early regression, epilepsy (60–80%), scoliosis | Disrupt methyl-binding domain; partial function retained. | R133C shows a milder phenotype due to residual binding. RNHS: Better ambulation in R133C (30% vs. 10% in R106W). |

| Nonsense | R168X, R255X, R270X | 30–40 | Severe | Profound intellectual disability, non-ambulatory, respiratory issues | Early truncation leading to a null function. | High sudden death risk (25%). 2025 data: Correlation with mitochondrial dysfunction suggests metabolic crisis. |

| Frameshift/Deletions | C-terminal deletions | 10–15 | Mild to Moderate | Preserved speech variant, later onset | Retain partial domains; 2024 iPSC data show reduced synaptic loss. | Therapeutic window exists for partial restoration. |

| Duplications | MECP2 duplication syndrome | <5 (males predominant) | Severe (males lethal) | Hypotonia, infections, autism-like features | Overexpression toxicity; mouse models demonstrate anxiety phenotypes. | Dosage sensitivity inferred. |

| System | Key Features | Prevalence | Mechanisms (Animal/iPSC Evidence) | Clinical Management | Inference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory / Breathing Dysrhythmia | Awake hyperventilation, apnea, breath-holds; brainstem circuit disruption; mitochondrial hypoxia | ~60–80% (RNHS 2024–2025: 70–80%) | Brainstem circuit disruption; mitochondrial hypoxia | NIV, oxygen; training | Central–peripheral interplay; oxidative stress target for therapies. |

| Cardiovascular / Autonomic | QTc prolongation, arrhythmia, HRV ↓ vagal tone; sympathetic overdrive | ~20% QTc↑ (RNHS: 75% instability; 20–30% QTc) | Ion channel dysregulation; sympathetic overdrive; mitochondrial contribution | Annual ECG; beta-blockers | Mitochondrial role inferred; sudden death prevention priority. |

| Gastrointestinal (Constipation, GERD, Dysphagia)* | Severe chronic constipation; reflux disease; swallowing incoordination | Constipation ~80–90% (RNHS: 80%); GERD/Dysphagia ~60–70% (RNHS: 70%) | Enteric neuron hypofunction; microbiome shifts | Laxatives, gastrostomy | Inflammation link; trofinetide GI AEs highlight need for adjuncts. |

| Skeletal (Scoliosis, Low BMD/Fractures)* | Scoliosis often progressive (>40°); osteopenia; frequent fractures | Scoliosis ≥60–85% (RNHS: 85%); Low BMD ≈45–60%; fractures ~30% (RNHS: 20%) | Osteoblast defects; endocrine (low Vitamin D) | Bisphosphonates; surgery | Immobility exacerbates; early PT inferred to mitigate. |

| CNS – Seizures | Onset 2–5 yrs; mix of focal and generalized; treatable | ~60–90% lifetime | Cortical hyperexcitability; neuronal circuit dysfunction | Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs); multidisciplinary seizure management | Seizure control impacts quality of life and neurodevelopment. |

| Growth / Nutrition | Short stature, poor weight gain, microcephaly | ~80–100% | Nutritional/metabolic dysfunction; growth hormone/endocrine contribution | Nutritional support; multidisciplinary monitoring | Growth failure central to prognosis; metabolic basis |

| Sleep | Insomnia, night awakenings, non-restorative sleep | ~60–80% | Circadian rhythm disruption; neurotransmitter imbalance | Behavioral interventions; melatonin | Sleep disturbance linked to cognition and seizures. |

| Anxiety / Mood | Excessive fear, anxious behaviors, mood swings | ~50–70% | Amygdala circuit dysfunction; altered GABA/glutamate signaling | Behavioral therapy; SSRIs (case-based) | Mental health central to QoL; neurochemical imbalance inferred. |

| Dental – Bruxism | Daytime teeth grinding | ~80–100% | Abnormal brainstem reflex pathways; neuromuscular dysregulation | Mouthguards; dental monitoring | Contributes to dental wear; symptomatic care only. |

| Peripheral / Autonomic – Cold Extremities | Vasomotor instability (cyanosis of hands/feet) | ~50% | Autonomic dysregulation; vascular tone impairment | Supportive management; warming measures | Peripheral autonomic dysfunction reinforces systemic involvement |

| Model System | Genetic Alteration / Type | Key Features / Uses | Strengths | Limitations | Inferences |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse Mecp2-null (Bird) males | Mecp2 null (hemizygote) | Rapid-onset RTT-like phenotype; seizures; early death (~10 wks) | High phenotypic fidelity; reproducible phenotype | Small brain size; not representative of female mosaicism | Adult re-expression reverses ~80% of phenotypes; omics show metabolic shifts. |

| Mouse Mecp2-null (heterozygous females) | Mecp2+/– (female heterozygote) | Mosaic neuronal populations; slower progression | Models clinical female RTT; long survival | Variable expressivity due to XCI | Omics reveal compensatory networks in mosaic populations. |

| Mouse Mecp2-duplication | Multiple Mecp2 transgene copies | Models MECP2 duplication syndrome; seizures | Relevant for antisense therapy | Overexpression artifacts; limited survival | Overexpression risks validated in vivo. |

| Conditional knockout mice | Mecp2 deleted in neuron/astrocyte/microglia | Cell-type specific phenotypes | Dissects MECP2 roles | Restricted scope | Highlights glial contributions to disease. |

| Rat Mecp2 knockout | Mecp2 deletion | RTT-like features; larger size | Larger brain; better dosing/autonomic profiling | Fewer strains; less genetic versatility | Enhanced autonomic profiling; better for gene therapy dosing. |

| Human iPSC-derived neurons | Patient fibroblasts reprogrammed | Reduced dendritic arborization, synaptic deficits | Human genotype/phenotype context | No systemic environment | Synaptic rescue demonstrated; 2025: mitochondrial targets identified. |

| Brain organoids (human iPSC) | 3D cortical cultures | Reveal early cortical networks, activity patterns | Human-specific; network-level | Limited maturation | Organoid models validate early neurodevelopmental signatures. |

| Large Animal / NHP Mecp2 models | Transgenic/gene-edited | Translational biodistribution, pharmacology | Closer to human brain | Ethical and costly | AAV safety validated; overexpression risks confirmed. |

| Zebrafish Mecp2-null | MecP2 mutant fish | Transparent larvae; rapid assays | Fast, scalable | Limited behavioral fidelity | Useful for rapid drug screening and in vivo imaging approaches. |

| Therapeutic Class / Strategy | Example(s) / Compound(s) | Mechanism of Action | Status | Key Efficacy / Safety Notes | Inference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacotherapy | Trofinetide | IGF-1 analog; neurotrophic/anti-inflammatory | FDA-Approved (2023) | Efficacy on RSBQ, CGI-I, CSBS. GI side effects (diarrhea, vomiting). | Symptom modifier; real-world reports suggest sustained benefits with careful GI management. |

| Neurotrophic / Growth Factor Strategies | IGF-1 (mecasermin) | Neurotrophic support | Phase 2 | Mixed efficacy; not advanced. | Highlights limitations of systemic IGF-1 therapy. |

| Gene Replacement Therapy | NGN-401 (Neurogene) | AAV-based MECP2 delivery | Phase I/II | High-dose halted (fatal inflammatory syndrome). Low-dose: 28–52% RSBQ improvement. | Potential disease modifier; tight dose regulation essential. |

| Dosage Normalization | ASOs (e.g., ISIS-LEGRO) | Silence MECP2 mRNA | Preclinical/early trials | Dosage titration possible; risk of over-suppression. | Conceptually validates dosage control; requires precision for safety. |

| Metabolic / Mitochondrial Modulators | Leriglitazone | PPAR-γ agonist; mitochondrial targeting | Phase 2a | Ongoing; systemic benefit expected. | Mitochondrial/metabolic pathways are relevant therapeutic targets. |

| Cell-based Approaches | Stem cell transplantation, exosome therapy | Replacement/trophic support | Investigational | Safety and targeting limitations. | Currently experimental; requires advanced targeting. |

| Neuromodulation | TNS, VNS | Electrical network modulation | Experimental | Small studies: improvements in arousal/respiration. | Adjunct potential but preliminary. |

| Symptomatic / Supportive Care | PT, OT, speech, nutritional support | Multidisciplinary | Standard of care | Improves quality of life. | Remains essential alongside all experimental therapies. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).