Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

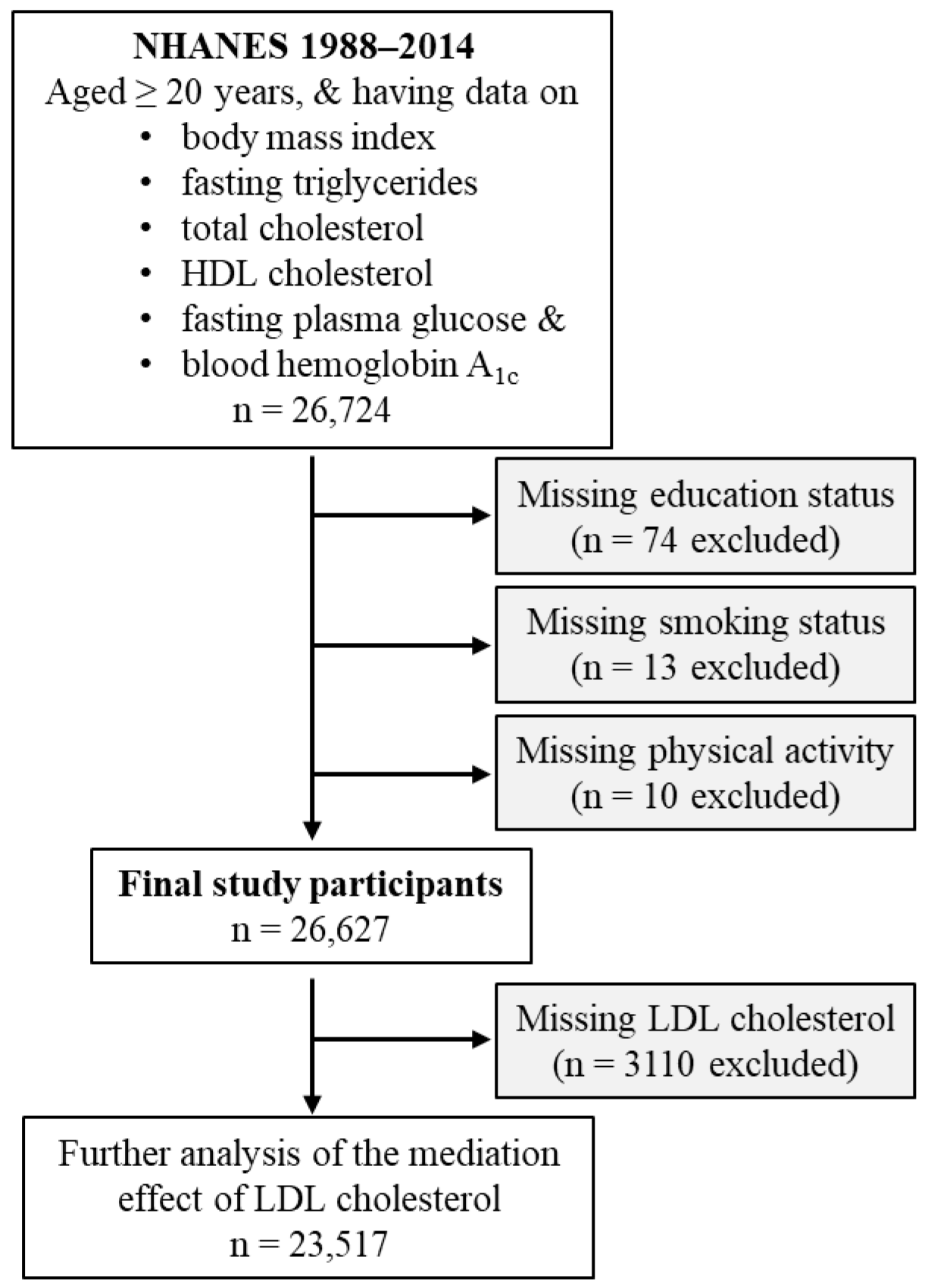

2.1. Study Participants

2.2. Exposure Variable

2.3. Outcome Variable

2.4. Candidate Mediators

2.4. Confounding Variables

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. General Characteristics

3.2. Association of Obesity with Diabetes Diagnosis

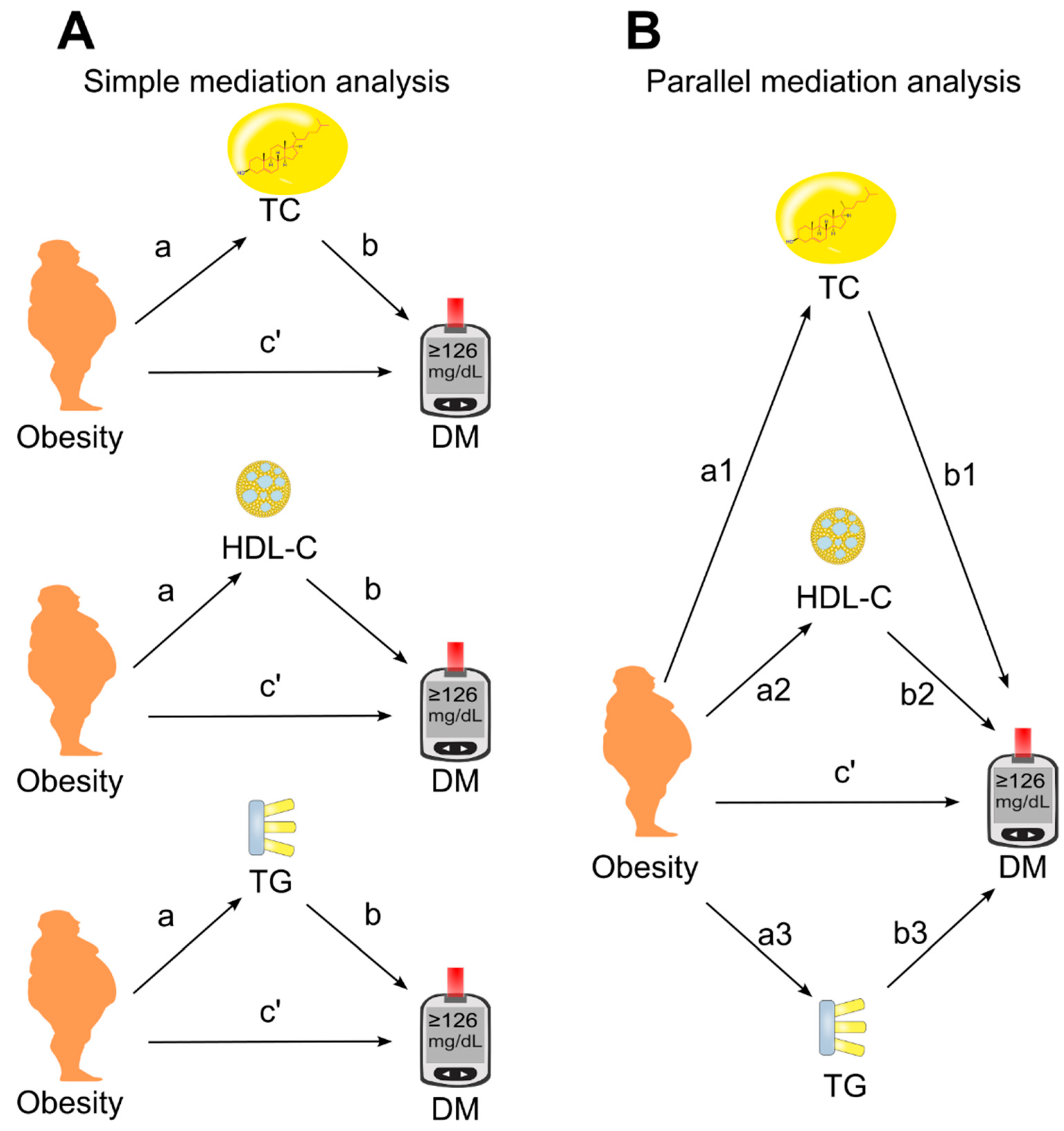

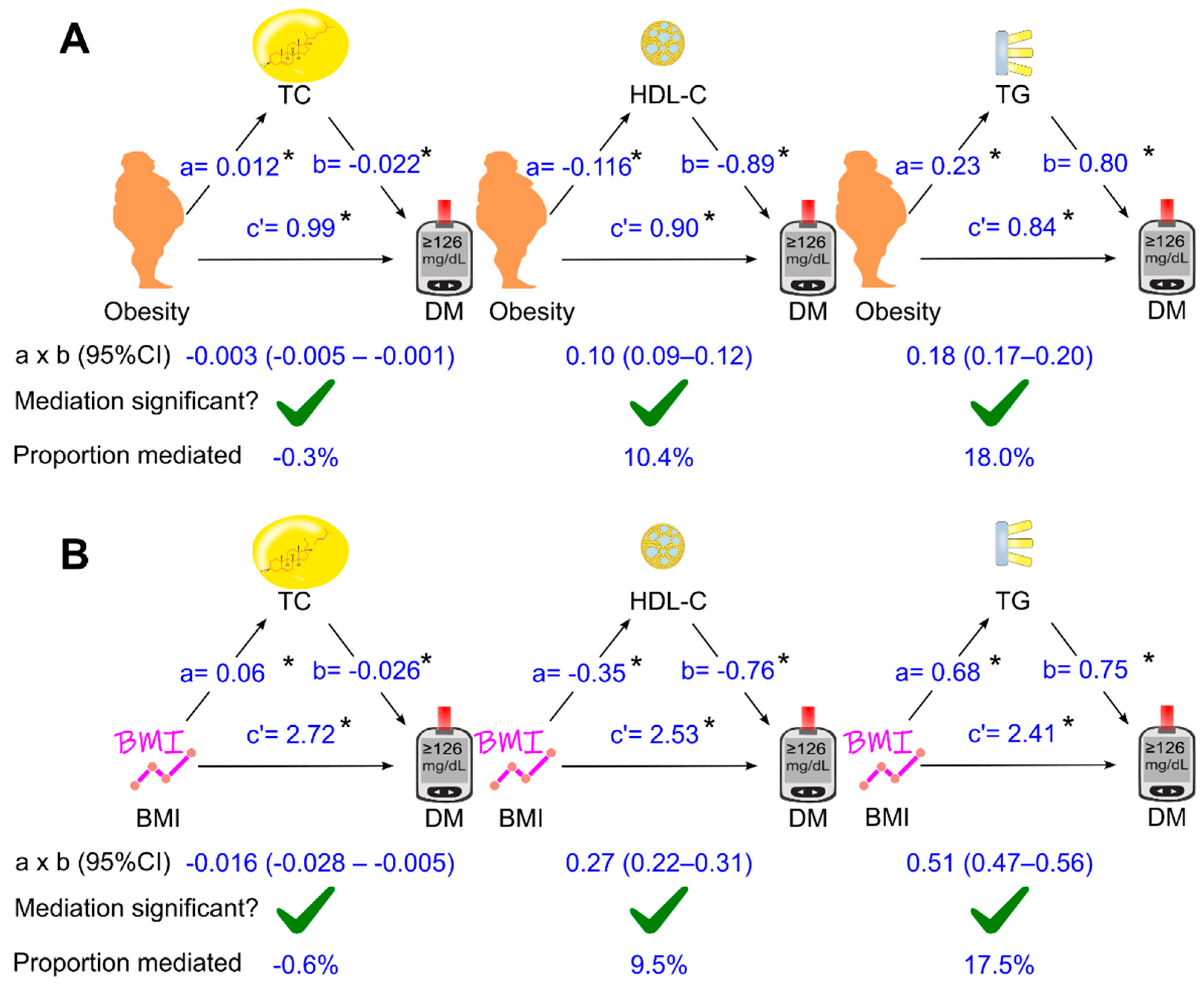

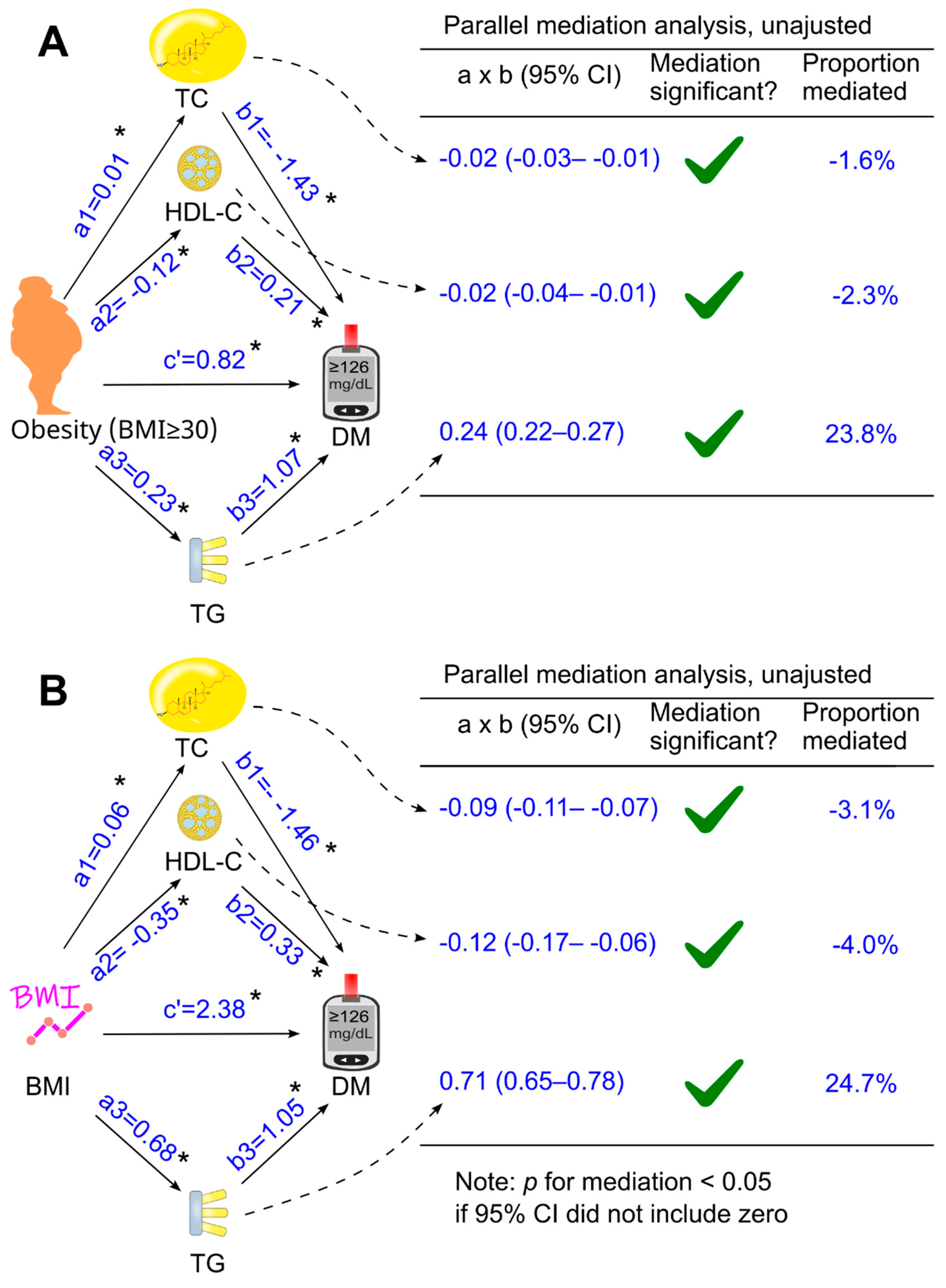

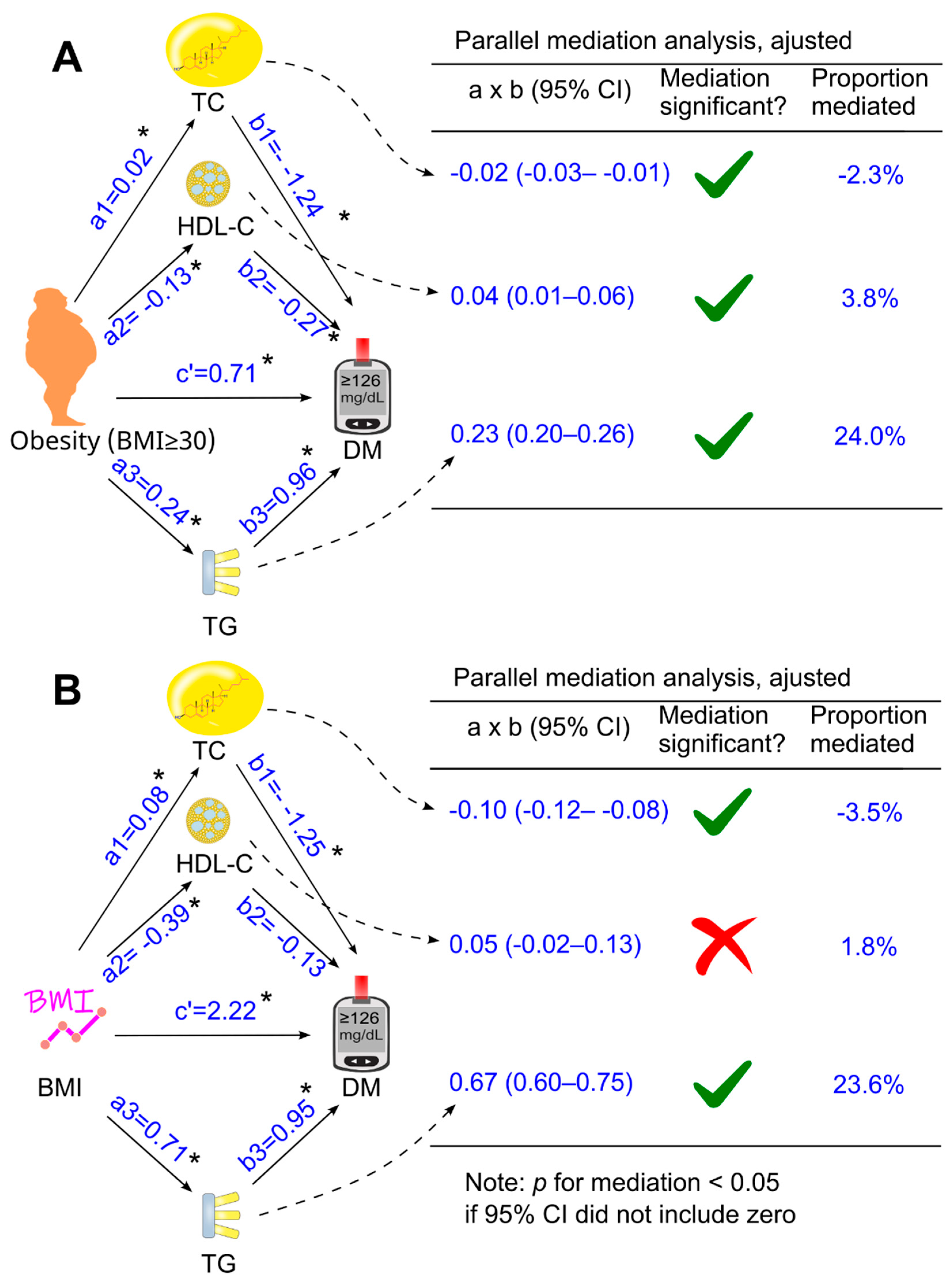

3.3. Role of Circulating Lipids in Mediating the Effect of Obesity on Diabetes

3.4. Role of Circulating Lipids in Mediating the Effect of Body Mass Index on Diabetes

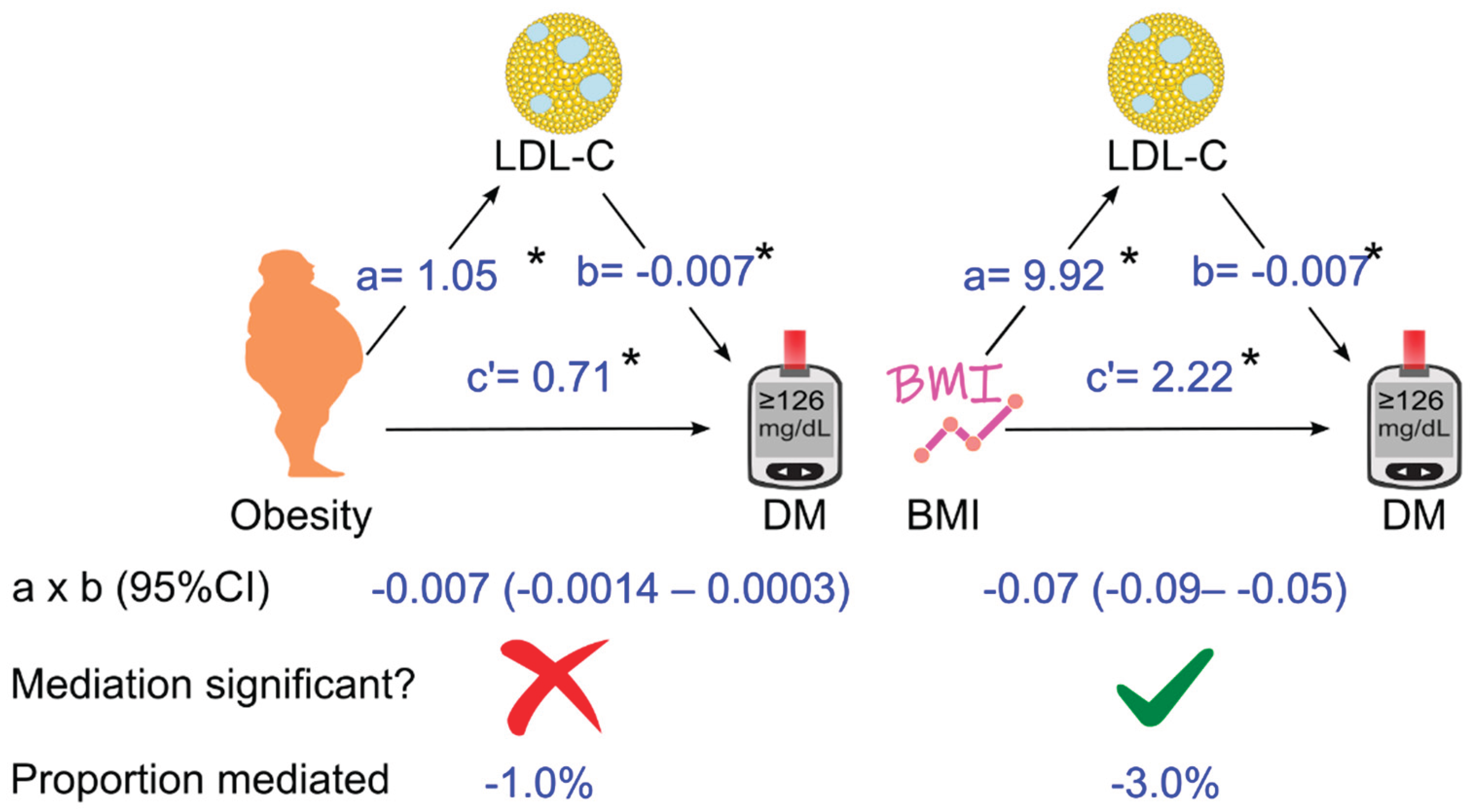

3.5. Further Analyses of the Role of LDL Cholesterol in Mediating the Effect of Obesity (or Body Mass Index) on Diabetes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CDC | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CETP | Cholesteryl ester transfer protein |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| DM | Diabetes |

| HbA1c | Hemoglobin A1c |

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein |

| HDL-C | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HSDA | N-(2-hydroxy-3-sulfopropyl)-3,5-dimethoxyaniline |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| LDL-C | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LDLR | LDL receptor |

| n | Number; |

| NA | Not applicable |

| NCHS | National Center for Health Statistics |

| NHANES | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| TC | Total cholesterol |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| VLDL | Very low-density lipoprotein |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Lingvay, I.; Cohen, R.V.; Roux, C.W.L.; Sumithran, P. Obesity in adults. Lancet 2024, 404, 972-987. [CrossRef]

- Ng, M.; Gakidou, E.; Lo, J.; Abate, Y.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, N.; Abbasian, M.; Abd ElHafeez, S.; Abdel-Rahman, W.M.; Abd-Elsalam, S.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of adult overweight and obesity, 1990–2021, with forecasts to 2050: a forecasting study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet 2025, 405, 813-838. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ. Tech. Rep. Ser. 2000, 894, 1-253.

- World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight. Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight. Accessed on 14 October 2025.

- House of Commons Library. Obesity statistics. Available at https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn03336/. Accessed on 15 October 2025.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Obesity Statistics in Canada: Report. Available at https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/obesity-statistics-canada.html#a6. Accessed on 15 October 2025.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Overweight and obesity. Available at https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/overweight-obesity/overweight-and-obesity/contents/summary. Accessed on 14 October 2025.

- Stierman, B.; Afful, J.; Carroll, M.D.; Chen, T.-C.; Davy, O.; Fink, S.; Fryar, C.D.; Gu, Q.; Hales, C.M.; Hughes, J.P. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017-March 2020 prepandemic data files-development of files and prevalence estimates for selected health outcomes. National health statistics reports 2021, number 158. [CrossRef]

- Buckell, J.; Mei, X.W.; Clarke, P.; Aveyard, P.; Jebb, S.A. Weight loss interventions on health-related quality of life in those with moderate to severe obesity: Findings from an individual patient data meta-analysis of randomized trials. Obes. Rev. 2021, 22, e13317. [CrossRef]

- Ul-Haq, Z.; Mackay, D.F.; Fenwick, E.; Pell, J.P. Meta-analysis of the association between body mass index and health-related quality of life among adults, assessed by the SF-36. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013, 21, E322-327. [CrossRef]

- Luppino, F.S.; de Wit, L.M.; Bouvy, P.F.; Stijnen, T.; Cuijpers, P.; Penninx, B.W.; Zitman, F.G. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 220-229. [CrossRef]

- Nedunchezhiyan, U.; Varughese, I.; Sun, A.R.; Wu, X.; Crawford, R.; Prasadam, I. Obesity, Inflammation, and Immune System in Osteoarthritis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 907750. [CrossRef]

- Pipitone, R.M.; Ciccioli, C.; Infantino, G.; La Mantia, C.; Parisi, S.; Tulone, A.; Pennisi, G.; Grimaudo, S.; Petta, S. MAFLD: a multisystem disease. Ther. Adv. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 14, 20420188221145549. [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Obesity and Cancer. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/risk-factors/obesity.html#:~:text=Overweight%20and%20obesity%20can%20cause,longer%20a%20person%20is%20overweight. Accessed on 15 October 2025.

- Onstad, M.A.; Schmandt, R.E.; Lu, K.H. Addressing the Role of Obesity in Endometrial Cancer Risk, Prevention, and Treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 4225-4230. [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.; Gastaldelli, A.; Yki-Järvinen, H.; Scherer, P.E. Why does obesity cause diabetes? Cell Metab. 2022, 34, 11-20. [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.J.; Al-Mamun, M.; Islam, M.R. Diabetes mellitus, the fastest growing global public health concern: Early detection should be focused. Health Sci Rep 2024, 7, e2004. [CrossRef]

- Klonoff, D.C. The increasing incidence of diabetes in the 21st century. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2009, 3, 1-2. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Diabetes. Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes. Accessed on 18 October 2025.

- World Obesity Federation. Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes: a Joint Approach to Halt the Rise. Available at https://www.worldobesity.org/news/idf-and-wof-release-new-policy-brief-to-address-obesity-and-type-2-diabetes. Accessed on 15 October 2025.

- International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes facts and figures. Available at https://idf.org/about-diabetes/diabetes-facts-figures/. Accessed on 1 October 2025.

- Wondmkun, Y.T. Obesity, Insulin Resistance, and Type 2 Diabetes: Associations and Therapeutic Implications. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2020, 13, 3611-3616. [CrossRef]

- Ruze, R.; Liu, T.; Zou, X.; Song, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, R.; Yin, X.; Xu, Q. Obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: connections in epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatments. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1161521. [CrossRef]

- Shamai, L.; Lurix, E.; Shen, M.; Novaro, G.M.; Szomstein, S.; Rosenthal, R.; Hernandez, A.V.; Asher, C.R. Association of body mass index and lipid profiles: evaluation of a broad spectrum of body mass index patients including the morbidly obese. Obes. Surg. 2011, 21, 42-47. [CrossRef]

- Denke, M.A.; Sempos, C.T.; Grundy, S.M. Excess body weight. An under-recognized contributor to dyslipidemia in white American women. Arch. Intern. Med. 1994, 154, 401-410. [CrossRef]

- Klop, B.; Elte, J.W.; Cabezas, M.C. Dyslipidemia in obesity: mechanisms and potential targets. Nutrients 2013, 5, 1218-1240. [CrossRef]

- Feingold, K.R. Obesity and Dyslipidemia; MDText.com, Inc.: South Dartmouth (MA). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK305895/, 2000.

- Bays, H.E.; Toth, P.P.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Abate, N.; Aronne, L.J.; Brown, W.V.; Gonzalez-Campoy, J.M.; Jones, S.R.; Kumar, R.; La Forge, R.; et al. Obesity, adiposity, and dyslipidemia: a consensus statement from the National Lipid Association. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2013, 7, 304-383. [CrossRef]

- Oda, E. LDL cholesterol was more strongly associated with percent body fat than body mass index and waist circumference in a health screening population. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2018, 12, 195-203. [CrossRef]

- Bays, H.E.; Chapman, R.H.; Grandy, S. The relationship of body mass index to diabetes mellitus, hypertension and dyslipidaemia: comparison of data from two national surveys. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2007, 61, 737-747. [CrossRef]

- Zipf, G.; Chiappa, M.; Porter, K.S.; Ostchega, Y.; Lewis, B.G.; Dostal, J. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: Plan and operations, 1999–2010. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat. 1 2013, 56, 1-37.

- Garvey, W.T.; Mechanick, J.I.; Brett, E.M.; Garber, A.J.; Hurley, D.L.; Jastreboff, A.M.; Nadolsky, K.; Pessah-Pollack, R.; Plodkowski, R. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology Comprehensive Clinical Practice Guidelines for Medical Care of Patients with Obesity. Endocr. Pract. 2016, 22, 842-884. [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, S. Role of Granulosa Cell Dysfunction in Women Infertility Associated with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Obesity. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 923.

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Vrablik, M. Homeostasis Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance Mediates the Positive Association of Triglycerides with Diabetes. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 733. [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2019. Diabetes Care 2019, 42, S13-s28. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Higher fasting triglyceride predicts higher risks of diabetes mortality in US adults. Lipids Health Dis. 2021, 20, 181. [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2021. Diabetes Care 2021, 44, S15-S33. [CrossRef]

- Lipid Laboratory Johns Hopkins. Total Cholesterol. Laboratory Procedure Manual. NHANES 2005-2006. Available from: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/public/2005/labmethods/tchol_d_met_h717.pdf. Access on 1 October 2025.

- Lipid Laboratory Johns Hopkins. HDL- Cholesterol. Laboratory Procedure Manual. NHANES 2005-2006. Available from: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/public/2005/labmethods/hdl_d_met_cholesterol_hdl_h717.pdf. Access on 1 October 2025.

- Lipid Laboratory Johns Hopkins. Triglycerides. Laboratory Procedure Manual. NHANES 2005-2006. Available from: https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/2005-2006/labmethods/trigly_d_met_triglyceride_h717.pdf. Access on 1 October 2025.

- NHANES. Cholesterol - LDL & Triglycerides. Available from https://wwwn.cdc.gov/Nchs/Nhanes/2009-2010/TRIGLY_F.htm. Accessed on 1 March 2025.

- Friedewald, W.T.; Levy, R.I.; Fredrickson, D.S. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem. 1972, 18, 499-502.

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Witting, P.K.; Charchar, F.J.; Sobey, C.G.; Drummond, G.R.; Golledge, J. Dietary fatty acids and mortality risk from heart disease in US adults: an analysis based on NHANES. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1614. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Magliano, D.J.; Charchar, F.J.; Sobey, C.G.; Drummond, G.R.; Golledge, J. Fasting triglycerides are positively associated with cardiovascular mortality risk in people with diabetes. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023, 119, 826–834. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Aberson, C.L.; Charchar, F.J.; Ceriello, A. Postprandial Plasma Glucose between 4 and 7.9 h May Be a Potential Diagnostic Marker for Diabetes. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1313.

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Qian, T.; Sun, H.; Xu, Q.; Hou, X.; Hu, W.; Zhang, G.; Drummond, G.R.; Sobey, C.G.; et al. Reduced renal function may explain the higher prevalence of hyperuricemia in older people. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1302. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Stage 1 hypertension and risk of cardiovascular disease mortality in United States adults with or without diabetes. J. Hypertens. 2022, 40, 794–803. [CrossRef]

- Qian, T.; Sun, H.; Xu, Q.; Hou, X.; Hu, W.; Zhang, G.; Drummond, G.R.; Sobey, C.G.; Charchar, F.J.; Golledge, J.; et al. Hyperuricemia is independently associated with hypertension in men under 60 years in a general Chinese population. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2021, 35, 1020-1028, doi:doi:10.1038/s41371-020-00455-7.

- Cheng, W.; Wen, S.; Wang, Y.; Qian, Z.; Tan, Y.; Li, H.; Hou, Y.; Hu, H.; Golledge, J.; Yang, G. The association between serum uric acid and blood pressure in different age groups in a healthy Chinese cohort. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017, 96, e8953. [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879-891. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. The PROCESS macro for SPSS, SAS, and R. Available from https://processmacro.org/index.html. Accessed on 21 July 2025.

- DiCiccio, T.J.; Efron, B. Bootstrap confidence intervals. Statistical Science 1996, 11, 189-228. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhong, H.Y.; Xiao, T.; Xiao, R.H.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.L.; Yao, Q.; Chen, X.J. Association between self-disclosure and benefit finding of Chinese cancer patients caregivers: the mediation effect of coping styles. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 684. [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.J.; Calton, E.K.; Pathak, K.; Zhao, Y. Hypothesized pathways for the association of vitamin D status and insulin sensitivity with resting energy expenditure: a cross sectional mediation analysis in Australian adults of European ancestry. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2022, 76, 1457-1463. [CrossRef]

- Ananth, C. Proportion mediated in a causal mediation analysis: how useful is this measure? BJOG 2019, 126, 983-983. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Definition, prevalence, and risk factors of low sex hormone-binding globulin in US adults. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e3946–e3956. [CrossRef]

- Gunzler, D.; Chen, T.; Wu, P.; Zhang, H. Introduction to mediation analysis with structural equation modeling. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry 2013, 25, 390-394. [CrossRef]

- Betteridge, D.J.; Carmena, R. The diabetogenic action of statins — mechanisms and clinical implications. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2016, 12, 99-110. [CrossRef]

- Carter, A.A.; Gomes, T.; Camacho, X.; Juurlink, D.N.; Shah, B.R.; Mamdani, M.M. Risk of incident diabetes among patients treated with statins: population based study. BMJ 2013, 346, f2610. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Cai, R.; Yuan, Y.; Varghese, Z.; Moorhead, J.; Ruan, X.Z. Association between reductions in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol with statin therapy and the risk of new-onset diabetes: a meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 39982. [CrossRef]

- Zaharan, N.L.; Williams, D.; Bennett, K. Statins and risk of treated incident diabetes in a primary care population. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 75, 1118-1124. [CrossRef]

- Galicia-Garcia, U.; Jebari, S.; Larrea-Sebal, A.; Uribe, K.B.; Siddiqi, H.; Ostolaza, H.; Benito-Vicente, A.; Martín, C. Statin Treatment-Induced Development of Type 2 Diabetes: From Clinical Evidence to Mechanistic Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [CrossRef]

- Endo, A. A gift from nature: the birth of the statins. Nat. Med. 2008, 14, 1050-1052. [CrossRef]

- Endo, A. A historical perspective on the discovery of statins. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 2010, 86, 484-493. [CrossRef]

- Femlak, M.; Gluba-Brzózka, A.; Ciałkowska-Rysz, A.; Rysz, J. The role and function of HDL in patients with diabetes mellitus and the related cardiovascular risk. Lipids Health Dis. 2017, 16, 207. [CrossRef]

- Barter, P.J. High Density Lipoprotein: A Therapeutic Target in Type 2 Diabetes. Endocrinol Metab 2013, 28, 169-177. [CrossRef]

- Fryirs, M.A.; Barter, P.J.; Appavoo, M.; Tuch, B.E.; Tabet, F.; Heather, A.K.; Rye, K.A. Effects of high-density lipoproteins on pancreatic beta-cell insulin secretion. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010, 30, 1642-1648. [CrossRef]

- Drew, B.G.; Duffy, S.J.; Formosa, M.F.; Natoli, A.K.; Henstridge, D.C.; Penfold, S.A.; Thomas, W.G.; Mukhamedova, N.; de Courten, B.; Forbes, J.M.; et al. High-density lipoprotein modulates glucose metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2009, 119, 2103-2111. [CrossRef]

- Barter, P.J.; Rye, K.A.; Tardif, J.C.; Waters, D.D.; Boekholdt, S.M.; Breazna, A.; Kastelein, J.J. Effect of torcetrapib on glucose, insulin, and hemoglobin A1c in subjects in the Investigation of Lipid Level Management to Understand its Impact in Atherosclerotic Events (ILLUMINATE) trial. Circulation 2011, 124, 555-562. [CrossRef]

- Hollister, L.E.; Overall, J.E.; Snow, H.L. Relationship of Obesity to Serum Triglyceride, Cholesterol, and Uric Acid, and to Plasma-Glucose Levels1. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1967, 20, 777-782. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, N.-Q. Non-Fasting Plasma Triglycerides Are Positively Associated with Diabetes Mortality in a Representative US Adult Population. Targets 2024, 2, 93-103. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, P.W.; Meigs, J.B.; Sullivan, L.; Fox, C.S.; Nathan, D.M.; D'Agostino, R.B., Sr. Prediction of incident diabetes mellitus in middle-aged adults: the Framingham Offspring Study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007, 167, 1068-1074. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Triglycerides, Glucose Metabolism, and Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9910. [CrossRef]

- Terauchi, Y.; Takamoto, I.; Kubota, N.; Matsui, J.; Suzuki, R.; Komeda, K.; Hara, A.; Toyoda, Y.; Miwa, I.; Aizawa, S.; et al. Glucokinase and IRS-2 are required for compensatory β cell hyperplasia in response to high-fat diet–induced insulin resistance. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2007, 117, 246-257. [CrossRef]

- Boden, G.; Chen, X.; Rosner, J.; Barton, M. Effects of a 48-h Fat Infusion on Insulin Secretion and Glucose Utilization. Diabetes 1995, 44, 1239-1242. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, D.A.; Hekerman, P.; Ladrière, L.; Bazarra-Castro, A.; Ortis, F.; Wakeham, M.C.; Moore, F.; Rasschaert, J.; Cardozo, A.K.; Bellomo, E.; et al. Initiation and execution of lipotoxic ER stress in pancreatic β-cells. J. Cell Sci. 2008, 121, 2308-2318. [CrossRef]

- Weinman, E.O.; Strisower, E.H.; Chaikoff, I.L. Conversion of Fatty Acids to Carbohydrate: Application of Isotopes to this Problem and Role of the Krebs Cycle as a Synthetic Pathway. Physiol. Rev. 1957, 37, 252-272. [CrossRef]

- Borrebaek, B.; Bremer, J.; Davis, E.J.; Thienen, W.D.V.-v.; Singh, B. The effect of glucagon on the carbon flux from palmitate into glucose, lactate and ketone bodies, studied with isolated hepatocytes. Int. J. Biochem. 1984, 16, 841-844. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.B.; O’Brien, P.E.; Playfair, J.; Chapman, L.; Schachter, L.M.; Skinner, S.; Proietto, J.; Bailey, M.; Anderson, M. Adjustable Gastric Banding and Conventional Therapy for Type 2 DiabetesA Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2008, 299, 316-323. [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, J.P.; Courcoulas, A.P.; Cummings, D.E.; Goldfine, A.B.; Kashyap, S.R.; Simonson, D.C.; Arterburn, D.E.; Gourash, W.F.; Vernon, A.H.; Jakicic, J.M.; et al. Diabetes Remission in the Alliance of Randomized Trials of Medicine Versus Metabolic Surgery in Type 2 Diabetes (ARMMS-T2D). Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 1574-1583. [CrossRef]

- Genua, I.; Ramos, A.; Caimari, F.; Balagué, C.; Sánchez-Quesada, J.L.; Pérez, A.; Miñambres, I. Effects of Bariatric Surgery on HDL Cholesterol. Obes. Surg. 2020, 30, 1793-1798. [CrossRef]

- Sjöström, L.; Lindroos, A.-K.; Peltonen, M.; Torgerson, J.; Bouchard, C.; Carlsson, B.; Dahlgren, S.; Larsson, B.; Narbro, K.; Sjöström Carl, D.; et al. Lifestyle, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Risk Factors 10 Years after Bariatric Surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 2683-2693. [CrossRef]

- Heffron, S.P.; Lin, B.-X.; Parikh, M.; Scolaro, B.; Adelman, S.J.; Collins, H.L.; Berger, J.S.; Fisher, E.A. Changes in High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Efflux Capacity After Bariatric Surgery Are Procedure Dependent. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2018, 38, 245-254. [CrossRef]

- Kawano, Y.; Ohta, M.; Hirashita, T.; Masuda, T.; Inomata, M.; Kitano, S. Effects of Sleeve Gastrectomy on Lipid Metabolism in an Obese Diabetic Rat Model. Obes. Surg. 2013, 23, 1947-1956. [CrossRef]

- Lim, E.L.; Hollingsworth, K.G.; Aribisala, B.S.; Chen, M.J.; Mathers, J.C.; Taylor, R. Reversal of type 2 diabetes: normalisation of beta cell function in association with decreased pancreas and liver triacylglycerol. Diabetologia 2011, 54, 2506-2514. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R. Type 2 Diabetes: Etiology and reversibility. Diabetes Care 2013, 36, 1047-1055. [CrossRef]

| Total cholesterol | HDL cholesterol | LDL cholesterol | |

| HDL cholesterol | 0.154 | ||

| LDL cholesterol | 0.917 | -0.070 | |

| Triglycerides | 0.367 | -0.317 | 0.178 |

| Non obese | Obese | Overall | p value | |

| Sample size | 18,202 | 8425 | 26,627 | NA |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 25 (23–27) | 34 (32–38) | 27 (24–31) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 1926 (10.6) | 2032 (24.1) | 3958 (14.9) | <0.001 |

| Glucose, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 95 (89–104) | 101 (94–114) | 97 (90–106) | <0.001 |

| HbA1c, %, median (IQR) | 5.3 (5.1–5.6) | 5.6 (5.3–6.0) | 5.4 (5.1–5.8) | <0.001 |

| TC, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 196 (169–225) | 198 (172–227) | 196 (170–225) | <0.001 |

| HDL-C, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 52 (43–64) | 46 (39–56) | 50 (42–61) | <0.001 |

| LDL-C 2, mg/dL, mean (SD) | 119.3 (36.8) | 121.3 (36.6) | 120.0 (36.8) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL, median (IQR) | 102 (72–150) | 131 (91–189) | 110 (77–163) | <0.001 |

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 48 (19) | 49 (17) | 48 (19) | <0.001 |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 9248 (50.8) | 3503 (41.6) | 12,751 (47.9) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 8522 (46.8) | 3464 (41.1) | 11,986 (45) | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic black | 3567 (19.6) | 2265 (26.9) | 5832 (21.9) | |

| Hispanic | 4963 (27.3) | 2463 (29.2) | 7426 (27.9) | |

| Other | 1150 (6.3) | 233 (2.8) | 1383 (5.2) | |

| Education, n (%) | ||||

| < High School | 5790 (31.8) | 2786 (33.1) | 8576 (32.2) | 0.01 |

| High School | 4651 (25.6) | 2209 (26.2) | 6860 (25.8) | |

| > High School | 7761 (42.6) | 3430 (40.7) | 11,191 (42.0) | |

| Poverty-income ratio, n (%) | ||||

| < 130% | 5008 (27.5) | 2585 (30.7) | 7593 (28.5) | <0.001 |

| 130%-349% | 6714 (36.9) | 3136 (37.2) | 9850 (37.0) | |

| ≥ 350% | 4929 (27.1) | 2032 (24.1) | 6961 (26.1) | |

| Unknown | 1551 (8.5) | 672 (8.0) | 2223 (8.3) | |

| Physical activity, n (%) | ||||

| Active | 5351 (29.4) | 1696 (20.1) | 7047 (26.5) | <0.001 |

| Insufficiently active | 6807 (37.4) | 3115 (37.0) | 9922 (37.3) | |

| Inactive | 6044 (33.2) | 3614 (42.9) | 9658 (36.3) | |

| Alcohol consumption, n (%) | ||||

| 0 drink/week | 2957 (16.2) | 1775 (21.1) | 4732 (17.8) | <0.001 |

| < 1 drink/week | 3846 (21.1) | 2166 (25.7) | 6012 (22.6) | |

| 1-6 drinks/week | 4004 (22.0) | 1392 (16.5) | 5396 (20.3) | |

| ≥ 7 drinks/week | 2606 (14.3) | 829 (9.8) | 3435 (12.9) | |

| Unknown | 4789 (26.3) | 2263 (26.9) | 7052 (26.5) | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||

| Past smoker | 4435 (24.4) | 1587 (18.8) | 6022 (22.6) | <0.001 |

| Current smoker | 4413 (24.2) | 2260 (26.8) | 6673 (25.1) | |

| Nonsmoker | 9354 (51.4) | 4578 (54.3) | 13,932 (52.3) | |

| Hypertension, n (%) | ||||

| No | 11,963 (65.7) | 3919 (46.5) | 15,882 (59.6) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 5991 (32.9) | 4377 (52.0) | 10368 (38.9) | |

| Unknown | 248 (1.4) | 129 (1.5) | 377 (1.4) | |

| Family history of diabetes, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 7239 (39.8) | 4340 (51.5) | 11,579 (43.5) | <0.001 |

| No | 10,626 (58.4) | 3931 (46.7) | 14,557 (54.7) | |

| Unknown | 337 (1.9) | 154 (1.8) | 491 (1.8) |

| Models | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p value |

| Model 1 | 2.69 | 2.51–2.88 | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 3.11 | 2.88–3.35 | <0.001 |

| Model 3 | 2.84 | 2.63–3.07 | <0.001 |

| Model 4 | 2.44 | 2.25–2.65 | <0.001 |

| Model 5 (Model 4 + TC) | 2.44 | 2.25–2.65 | <0.001 |

| Model 6 (Model 4 + HDL-C) | 2.14 | 1.97–2.32 | <0.001 |

| Model 7 (Model 4 + TG) | 2.13 | 1.96–2.31 | <0.001 |

| Model 8 (Model 4 + TC + HDL-C + TG) | 2.03 | 1.87–2.21 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).