1. Introduction

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are exogenous compounds that interfere with the synthesis, secretion, transport, or action of natural hormones, thereby disrupting endocrine homeostasis [

1,

2]. Dietary intake is a primary route of human exposure to EDCs, which have been increasingly linked to reproductive dysfunction, metabolic disorders, neuroendocrine disturbances, and various cancers [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

Bisphenol A (BPA; 2,2-bis (4-hydroxyphenyl) propane) is a well-characterized xenoestrogen and a high-production-volume chemical, with global output projected to reach 9.3 million tons by 2030 [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. It is ubiquitous in consumer products, including polycarbonate plastics, epoxy resins lining food containers, and medical devices [

13]. Human exposure to BPA is associated with dysregulation of multiple hormonal pathways, including those for androgens, insulin, and thyroid hormones [

14,

15]. Epidemiological and experimental studies further link BPA to cardiovascular diseases, obesity, reproductive developmental disorders, and cancers of the breast and prostate, mediated through molecular and metabolic mechanisms [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

The thyroid gland is particularly vulnerable to EDCs exposure [

23]. Thyroid function is modulated by estrogenic signaling, and due to its structural mimicry of estrogen, BPA can bind to estrogen receptors in thyroid follicular cells, perturbing receptor-mediated processes [

24,

25,

26].

Urinary BPA levels in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) were higher than those found in healthy individuals, suggesting that BPA may be a risk factor for the development of PTC [

27]. In animal model studies, the synergistic effect between BPA and excess of iodine was confirmed, which, together, may increase susceptibility to the development of thyroid tumors in rats [

28]. In Chinese women, elevated urinary BPA levels were associated with an increased risk of thyroid nodules (TNs), but only in those with positive thyroid autoantibodies. This relationship was nearly linear, suggesting that BPA exposure is directly related to an increased risk of TNs [

29] in that setting.

BPA exposure was described to alter the expression of critical genes involved in thyroid hormone synthesis, such as sodium-iodide symporter (NIS), thyroglobulin (Tg), and thyroid peroxidase (TPO), as well as key developmental transcription factors like Pax8, Nkx2-1, and Foxe1 [

30]. While regulatory agencies have established tolerable daily intake (TDI) values for BPA, these vary significantly, from the European Food Safety Authority's (EFSA) of 0.2 ng/kg/day to the U.S. EPA/FDA reference dose of 4 µg/kg/day [

31,

32,

33,

34]. This discrepancy, coupled with evidence of thyroid sensitivity to low EDC doses, underscores the necessity of assessing the effects of BPA across a range of physiologically relevant concentrations.

Existing data demonstrate that BPA can impair thyroid function, alter glandular morphology, and promote thyroid tumor cell proliferation [

28,

35,

36,

37]. However, molecular studies have reported contradictory findings, and a comprehensive comparison of BPA's functional impact across thyroid cell lines with distinct genetic backgrounds is lacking. Such an investigation is critical to elucidate how genetic susceptibility influences cellular responses to this common environmental contaminant. The relationship between BPA and thyroid cancer is inconclusive. This is particularly relevant given the high prevalence of thyroid nodules, which are detectable in up to half of the adult population and represent a substantial pool of follicular cells at risk of acquiring genetic alterations. This context is crucial given the rising global incidence of thyroid cancer, largely attributed to papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC). PTC is frequently driven by oncogenic mutations, such as BRAF V600E and RET/PTC rearrangements, which promote tumorigenesis through the constitutive activation of the MAPK pathway [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43].

This study aimed to characterize and elucidate the genotype-dependent effects of BPA on the viability, proliferation, and migration of normal and neoplastic -derived human thyroid cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines and Culture Conditions

Three human thyroid cell lines were employed in this study: Nthy-ori 3-1, an immortalized non-tumorigenic thyroid follicular epithelial line, served as a control; BCPAP and TPC-1, derived from PTC, represented malignant models with distinct molecular backgrounds. BCPAP harbors the BRAF V600E mutation, whereas TPC-1 carries the RET/PTC rearrangement.

Cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Capricorn Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, Gibco, EUA. and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Penicillin/Streptomycin and Amphotericin B) (Invitrogen™, USA) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO₂. Passaging was performed every three days using standard trypsinization. In T25 flasks to Nthy-ori 3-1 cells were seeded at 3.0×10⁴ cells/mL, reflecting their lower proliferation rate, while BCPAP and TPC-1 cells were seeded at 1.5×10⁴cells/mL accommodate higher proliferation rates. Approximately 1×10⁵ cells were cultured in each well of a 24-well plate.

2.2. BPA Preparation

Bisphenol A (CAS No. 80-05-7, ≥95 % purity) (BPA; 2,2-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl) propane, Supelco, USA) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Final working concentrations (0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, and 1.0 µg/mL) were prepared in culture medium with a final DMSO concentration ≤0.1% (v/v). Vehicle controls contained 0.1% DMSO.

2.3. BPA Exposure Protocol

After 24 h of seeding, the cultures were washed with pre-warmed PBS 1X and treated with BPA-containing medium for 24 or 48 h. Exposure concentrations (0.1-1.0 µg/mL) were selected based on the maximum migration limit (LME) allowed in food by the Brazilian regulatory agency (ANVISA), corresponding to physiologically relevant doses (~1 µg/mL). Cultures were maintained under standard incubator conditions (37 °C, 5% CO₂, saturated humidity) for the duration of treatment

All experiments were performed in biological triplicates with at least two technical replicates per condition.

2.4. Cell Viability Assays

2.4.1. Trypan Blue Exclusion

The cells were detached, resuspended, and mixed 1:1 with 0.4% Trypan Blue solution. Viable cells remained unstained, whereas non-viable cells were stained blue. Cell counts were performed in a Neubauer chamber, and viability was calculated. Cell viability was expressed as the percentage of viable cells relative to the total number of cells.

2.4.2. PrestoBlue® Assay

PrestoBlue® reagent (Invitrogen™, USA) was used to assess metabolic activity. After BPA treatment, medium was replaced with 100 µL of fresh medium containing 10% PrestoBlue®, and plates were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C, 5% CO₂, protected from light. Fluorescence was measured using a SpectraMax® microplate reader (excitation: 560 nm; emission: 590 nm). Relative viability was calculated in reference to the control condition (0.1% DMSO), after subtracting the blank fluorescence readings from both the control and the treated samples. The resulting values were used to determine the percentage of viable cells in each condition.

2.5. Cell Proliferation (EdU Incorporation)

Proliferation was assessed using the Click-iT™ EdU Alexa Fluor™ 647 Imaging Kit (Invitrogen™, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, after BPA exposure, the cells were incubated with 20 µM EdU for 2 hours. The cells were then fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100, and stained using the Click-iT® reaction cocktail along with Hoechst nuclear counterstain. Fluorescence imaging was performed using the Operetta® system, and proliferation was automatically quantified as the percentage of EdU-positive nuclei.

2.6. Cell Migration (Wound Healing Assay)

Directional migration was evaluated using a wound-healing assay. Cells were seeded in Ibidi® Culture-Insert 2 well µ-Dishes until confluence. The inserts were removed, and the monolayer was washed with PBS. Cells were treated with BPA, and wound closure was imaged every 30 minutes using the Opera Phenix® imaging system. Migration rates were automatically quantified by measuring the reduction in cell-free area over time.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.0.1. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were conducted using one-way ANOVA with post-hoc tests or Student’s t-test, as appropriate. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. BPA Reduces Viability and Metabolic Activity in Thyroid Cells

In non-tumorigenic Nthy-ori 3-1 cells, viability assessed by Trypan Blue exclusion was reduced even at the lowest BPA concentration (0.1 µg/mL), showing a dose-dependent reduction. After 24 h, significant reductions were detected at 0.8 and 1.0 µg/mL (p ≤ 0.05), which became more pronounced at 48 h (0.8 µg/mL, p ≤ 0.05; 1.0 µg/mL, p ≤ 0.001), indicating a clear cytotoxic effect of BPA on normal thyroid cells. In the PrestoBlue assay, Nthy-ori 3-1 cells displayed viability comparable to controls at low BPA concentrations but showed significant reductions at 0.8 µg/mL (p = 0.05) and 1.0 µg/mL (p = ≤0.001), which became more pronounced after 48 h, consistent with Trypan Blue findings (Figure 1a).

TPC-1 cells exhibited a more gradual and modest reduction in viability in the Trypan Blue assay. At 24 hours, slight increases in cell numbers were observed at 0.2 and 0.4 µg/mL, followed by a decrease at 0.8 µg/mL, although these changes were not statistically significant. After 48 hours, reductions began at 0.1 µg/mL and reached significance at 0.8 and 1.0 µg/mL (p ≤0.05), suggesting a relative resistance of RET/PTC-rearranged cells to BPA compared with that of normal thyroid cells. Cell viability measured by PrestoBlue measured by PrestoBlue remained stable at lower and intermediate concentrations but was significantly reduced at 0.8 and 1.0 µg/mL (p = ≤0.05 and p = ≤0.001, respectively), consistent with the trends observed in the Trypan Blue assay (Figure 1b).

BCPAP cells exhibited a variable response, with slight decreases in viability at lower BPA concentrations, particularly at 24 hours after treatment. A biphasic pattern was observed, with some intermediate doses showing viability comparable to that of the controls. At 48 hours, minor reductions were observed at 0.2 µg/mL, while slight increases were noted at 0.4 and 0.8 µg/mL, potentially reflecting the intrinsic characteristics of BRAF-mutant cells. Metabolic activity after 24 hours of exposure showed minor decreases at intermediate concentrations, with 0.8 µg/mL and 1.0 µg/mL resulting in reductions of 1.5% (p = ≤0.05) and 2.6% (p = ≤0.001), respectively. At 48 hours, these reductions reached approximately 10% at 0.8 µg/mL (p = ≤0.05) and 15% at 1.0 µg/mL (p = ≤0.001), confirming a modest but significant effect on cell viability (

Figure 1c).

3.2. BPA impairs Thyroid Cancer Cell Proliferation

The effects of BPA on thyroid cell proliferation were assessed using the EDU incorporation assay (

Figure 2). Nthy-ori 3-1 cell proliferation was not significantly altered compared with control after 48 h of treatment (0.8 µg/mL: 39.57%, p = 0.485; 1.0 µg/mL: 38.22%, p = 0.732), suggesting that BPA did not affect DNA synthesis in normal thyroid cells. In TPC-1 cells, proliferation remained near control levels at both 0.8 µg/mL (41.62%; 1.0% increase) and 1.0 µg/mL (41.60%; 0.97% decrease), with no significant differences observed (p = 0.6730 and p > 0.9999, respectively). These results suggest that exposure to BPA at concentrations of 0.8 µg/mL and 1.0 µg/mL does not significantly affect the proliferative capacity of this RET-rearranged cell line. In BCPAP cells, proliferation remained near-control at 0.8 µg/mL (26.74%; 7.1% reduction) and showed a significant decrease at 1.0 µg/mL (22.76%; 20.9% reduction; p ≤ 0.05), suggesting a dose-dependent impairment of proliferative capacity in this BRAF-mutant cell line.

3.3. BPA Modulates Thyroid Cell Migration

Closure of the cell-free area in Nthy-ori 3-1 cells progressed gradually in controls, reaching near-complete closure (~0% open area) between 24 and 30 h of treatment. In BPA-treated cells (0.8 and 1.0 µg/mL), area closure was accelerated, with consistently smaller open areas compared with control (

Figure 3). At 0.8 µg/mL, closure occurred more rapidly, particularly during the early phase. Significant differences were observed between 1.5 and 4.5 h (p ≤ 0.05), indicating a clear stimulatory effect of BPA on early cell migration. Between 5 and 9 h, the effect remained pronounced, with mean differences of approximately 21-22% relative to control and highly significant values (p ≤ 0.01), suggesting a peak effect during this interval. After 10-10.5 h, differences remained statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05) but the magnitude began to decrease. These results indicate that even at low doses, BPA consistently enhances the migratory capacity of non-tumorigenic thyroid cells. At 1.0 µg/mL, a similar reduction in open area was observed, although values were comparable to control, with a trend toward slightly accelerated migration during the early hours. However, statistical analysis did not detect significant differences (p ≥ 0.05) between control and treatment. Mean migration differences for Nthy-ori 3-1 cells exposed to 0.8 µg/mL BPA are provided in see

Table S1, while data for area closure under both treatments are shown in

Figure 3.

TPC-1 cells displayed rapid baseline closure, with full closure in control within 24 hours. BPA-treated cells showed minor acceleration (0.8 µg/mL: closure ~17 h; 1.0 µg/mL: ~19 h), but differences were not statistically significant (p ≥ 0.05), indicating a subtle effect on migration (

Figure 4 and

Table S2).

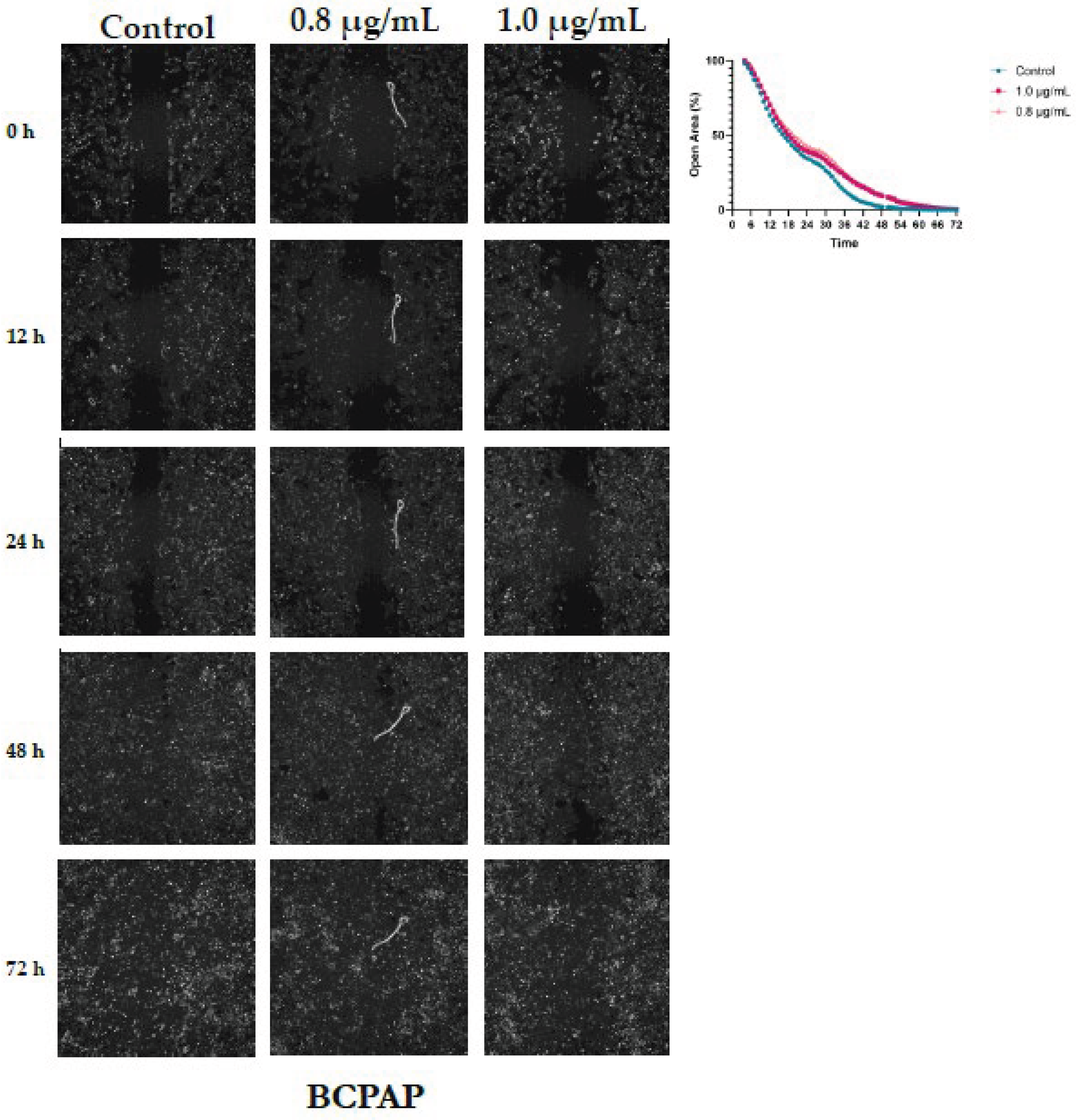

In BCPAP cells, closure of the cell-free area occurred more slowly compared with the other cell lines, requiring a total observation period of 72 hours. In control cells, the area approached complete closure around 53 hours. In BPA-treated groups (0.8 and 1.0 µg/mL), closure was delayed, occurring at approximately 71 and 66 hours, respectively. Both doses resulted in slightly larger open areas than those observed in control at various time points (

Figure 5). Comparison between the 0.8 µg/mL treatment and control revealed that BPA significantly reduced the rate of area closure. Mean differences ranged from -4.9% to -6.3%, with 95% confidence intervals excluding zero, indicating a consistent inhibitory effect over the course of the analysis. Most comparisons reached statistical significance (p ≤ 0.05), with the strongest effects observed between 28 and 30 hours, showing the lowest p-values (p < 0.001), as presented in

Table S3.

4. Discussion

Our study demonstrates that BPA exerts cell type- and dose-dependent effects on human thyroid cell lines, influencing viability, proliferation, and migration in a manner that seems to be dictated by the cells' genetic background.

The heightened sensitivity of non-tumorigenic Nthy-ori 3-1 cells was evident in the clear, dose-dependent decrease in viability at higher BPA concentrations (0.8–1.0 µg/mL), as corroborated by both Trypan Blue and PrestoBlue assays. This finding aligns with previous reports that BPA disrupts thyroid function by interfering with signaling, and metabolic homeostasis [

11,

44]. Intact endocrine regulatory pathways in normal cells may render them more susceptible to xenobiotic-induced stress and cytotoxicity. Interestingly, despite this reduced viability, the proliferative capacity of Nthy-ori 3-1 cells remained unchanged, suggesting that BPA induces cytotoxic stress, leading to cell death in a subset of the population without arresting the cell cycle in the remaining cells. A striking and paradoxical finding was that BPA significantly accelerated the migration of normal cells. This pro-migratory effect, particularly at 0.8 µg/mL, suggests that BPA may activate pathways promoting cytoskeletal rearrangement and motility, potentially through estrogen receptor signaling or HIF-1α/VEGF pathways, which are known to be influenced by BPA in other cell types [

45]. Divergent effect was observed between the two cancer cell lines. TPC-1 cells harboring RET/PTC rearrangements do not exhibit inhibition of proliferation, in contrast to BCPAP cells carrying the BRAF V600E mutation that displayed only modest, but significant, reductions in proliferation at the highest concentration. This latter finding is consistent with studies on prostate cancer models, where BPA triggered antiproliferative effects via p53 regulation and upregulation of p21 and p27 [

46]. This relative resistance may reflect the constitutive activation of the MAPK/ERK pathway, which confers resilience to cytostatic effects [

46]. BCPAP cells also exhibited significantly impaired migratory capacity upon BPA exposure, contrasting sharply with the stimulated motility observed in normal cells. This dichotomy underscores a potential biphasic or hormetic effect, wherein BPA exerts opposing actions on cell motility depending on the oncogenic drivers and the balance of proliferative and signaling pathways [

45,

47].

The divergent responses observed among the three cell lines highlight the complex interplay between BPA and thyroid cell signaling pathways. Owing to its structural similarity to estradiol, BPA can interact with estrogen receptors expressed in thyroid follicular cells, thereby modulating key processes, such as proliferation and migration [

26,

28,

48,

49].

The BCPAP cell line exhibits high expression of estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) and comparatively low expression of estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) relative to normal thyroid cells [

50]. An increased ERα/ERβ ratio has been associated with enhanced proliferative, invasive, and migratory behaviors, supporting a pro-tumorigenic role for ERα and a counter-regulatory, inhibitory role for ERβ [

51]. Consistent with this, exposure to agents that downregulate ERα or upregulate ERβ expression reduces BCPAP cell aggressiveness [

52,

53]. Similarly, the TPC-1 cell line expresses both ERα and ERβ, although the expression levels vary depending on the experimental context [

54]. In these cells, ERα is generally linked to proliferative and pro-survival signaling, whereas ERβ contributes to differentiation and pro-apoptotic pathways [

55]. In addition to classical nuclear receptors, TPC-1 cells express the membrane-associated G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER1), which mediates rapid, non-genomic responses to estrogenic stimuli [

56]. Collectively, these receptor expression profiles provide a plausible mechanistic basis for the genotype-dependent effects of BPA observed in this study, suggesting that the balance between ERα, ERβ, and GPER1 signaling may critically shape the cellular outcomes of BPA exposure in normal and neoplastic thyroid contexts.

Furthermore, BPA-induced oxidative stress, DNA damage, and altered expression of thyroid-specific transcription factors, such as Pax8, Nkx2-1, and Foxe1, may contribute to the observed cytotoxicity and impaired proliferative capacity in susceptible cell types [

32,

35]. Our data suggest that genetic background is a critical determinant of BPA response, revealing mutation-specific vulnerabilities that may be relevant to thyroid cancer progression.

It is important to note that this study has limitations. The use of in vitro models and short-term exposures does not fully capture the complexity of chronic BPA exposure in a whole-organism context, and the precise molecular mechanisms underlying the observed differential effects remain to be elucidated. Despite these constraints, the concentrations used (0.1 -1.0 µg/mL) are within the range estimated for human dietary exposure, highlighting the physiological relevance of our findings [

13,

23]. The significant effects observed at these concentrations highlight concerns about the widespread presence of BPA, suggesting that even low-dose exposure may impact thyroid cell function, particularly in genetically predisposed or neoplastic cells. To further consolidate the findings on cell proliferation, it is essential to conduct cell cycle analysis, as well as assays to assess cell death mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our data contribute to the understanding of the complex and genotype dependent nature of the effects of BPA on thyroid cells. BPA is not a uniformly cytotoxic or promotive agent but rather a modulator whose functional impact, inducing cytotoxicity in normal cells, impairing migration in RET/PTC-rearranged cells and proliferation in BRAF-mutant cells, is interpreted through the molecular identity of the cell. These findings underscore the need of considering genetic susceptibility in toxicological risk assessment and provide a compelling foundation for future mechanistic studies to dissect the signaling pathways involved, thereby informing regulatory policies aimed at minimizing BPA-related thyroid dysfunction and cancer risk.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: E.S.T. and L.S.W.; Methodology: E.S.T. and M.B.G.; Software: E.S.T.; Validation: E.S.T. and M.B.G.; Formal Analysis: E.S.T.; Investigation: E.S.T. and L.S.W.; Resources: L.S.W. and P.S.; Data Curation: E.S.T.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation: E.S.T.; Writing – Review and Editing: E.S.T., L.S.W., and P.S.; Visualization: L.T.R; K.C.P.; N.E.B.; V.M.; Supervision: L.S.W. and P.S.; Funding Acquisition: L.S.W. and P.S. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

That work was supported by FEDER financial support for operation no. 16135, operation code at the Funds Counter COMPETE2030-FEDER-00728800, within the scope of Notice for Submission of Applications no. MPr-2023-12. It also received the support of FAPESP (project 2023/12993-6) and CNPq (project 441433/2023-5 and 201096/2024-2).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was waived for this study as it did not involve human participants or animals.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are available in the REDU repository of the State University of Campinas (UNICAMP) under the identifier

https://doi.org/10.25824/redu/HH7SBA.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BPA |

Bisphenol A |

| EDCs |

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals |

| TN |

Thyroid nodules |

| NIS |

Sodium-iodide symporter |

| TG |

Thyroglobulin |

| TPO |

Thyroid peroxidase |

| TDI |

Tolerable daily intake |

| EFSA |

European Food Safety Authority |

| PTC |

Papillary thyroid carcinoma |

| DMSO |

Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| LME |

Maximum migration limit |

| ERα |

Estrogen receptor alpha |

| ERβ |

Estrogen receptor beta |

| GPER1 |

G protein-coupled estrogen receptor |

References

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, E.; Bourguignon, J.-P.; Giudice, L.C.; Hauser, R.; Prins, G.S.; Soto, A.M.; Zoeller, R.T.; Gore, A.C. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: An Endocrine Society Scientific Statement. Endocr. Rev. 2009, 30, 293–342. [CrossRef]

- Peivasteh-Roudsari, L.; Barzegar-Bafrouei, R.; Sharifi, K.A.; Azimisalim, S.; Karami, M.; Abedinzadeh, S.; Asadinezhad, S.; Tajdar-Oranj, B.; Mahdavi, V.; Alizadeh, A.M.; et al. Origin, dietary exposure, and toxicity of endocrine-disrupting food chemical contaminants: A comprehensive review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18140. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee R, Pandya P, Baxi D, Ramachandran AV. Endocrine Disruptors-'Food' for Thought. Proc Zool Soc. 2021;74(4):432-42.

- Patisaul, H.B. REPRODUCTIVE TOXICOLOGY: Endocrine disruption and reproductive disorders: impacts on sexually dimorphic neuroendocrine pathways. Reproduction 2021, 162, F111–F130. [CrossRef]

- La Merrill, M.A.; Vandenberg, L.N.; Smith, M.T.; Goodson, W.; Browne, P.; Patisaul, H.B.; Guyton, K.Z.; Kortenkamp, A.; Cogliano, V.J.; Woodruff, T.J.; et al. Consensus on the key characteristics of endocrine-disrupting chemicals as a basis for hazard identification. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 16, 45–57. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, C.; Jeung, E.-B. Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals and Disease Endpoints. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5342. [CrossRef]

- Amon, M.; Kek, T.; Klun, I.V. Endocrine disrupting chemicals and obesity prevention: scoping review. J. Heal. Popul. Nutr. 2024, 43, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Kannan, K. Concentrations and Profiles of Bisphenol A and Other Bisphenol Analogues in Foodstuffs from the United States and Their Implications for Human Exposure. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 4655–4662. [CrossRef]

- Mandel, N.D.; Gamboa-Loira, B.; Cebrián, M.E.; Mérida-Ortega, Á.; López-Carrillo, L. Challenges to regulate products containing bisphenol A: Implications for policy. Salud Publica De Mex. 2019, 61, 692–697. [CrossRef]

- Valentino, R.; D’esposito, V.; Ariemma, F.; Cimmino, I.; Beguinot, F.; Formisano, P. Bisphenol A environmental exposure and the detrimental effects on human metabolic health: is it necessary to revise the risk assessment in vulnerable population?. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2015, 39, 259–263. [CrossRef]

- Gore, A.C.; Chappell, V.A.; Fenton, S.E.; Flaws, J.A.; Nadal, A.; Prins, G.S.; Toppari, J.; Zoeller, R.T. EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s Second Scientific Statement on Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Endocr. Rev. 2015, 36, E1–E150. [CrossRef]

- Markets Ra. Global Bisphenol A Strategic Industry Report 2023-2030 with Coverage of 30+ Major Players Including Altivia, ChangChun Group, Covestro AG. 2024.

- Rochester JR. Bisphenol A and human health: a review of the literature. Reprod Toxicol. 2013;42:132-55.

- Fenercioglu, A.K.; Unal, D.O. The Role of Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals in the Development of Atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2025, 25, 1706–1717. [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.L.Y.; Co, V.A.; El-Nezami, H. Endocrine disrupting chemicals and breast cancer: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 62, 6549–6576. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Yang, Y.; Baral, K.; Fu, Y.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, F.; Zhao, M. Relationship between bisphenol A and the cardiovascular disease metabolic risk factors in American adults: A population-based study. Chemosphere 2023, 324, 138289. [CrossRef]

- Le Magueresse-Battistoni, B.; Labaronne, E.; Vidal, H.; Naville, D. Endocrine disrupting chemicals in mixture and obesity, diabetes and related metabolic disorders. World J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 8, 108–119. [CrossRef]

- Jozkowiak, M.; Piotrowska-Kempisty, H.; Kobylarek, D.; Gorska, N.; Mozdziak, P.; Kempisty, B.; Rachon, D.; Spaczynski, R.Z. Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: The Relevant Role of the Theca and Granulosa Cells in the Pathogenesis of the Ovarian Dysfunction. Cells 2022, 12, 174. [CrossRef]

- Mínguez-Alarcón, L.; Hauser, R.; Gaskins, A.J. Effects of bisphenol A on male and couple reproductive health: a review. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 106, 864–870. [CrossRef]

- Gao H, Yang BJ, Li N, Feng LM, Shi XY, Zhao WH, et al. Bisphenol A and hormone-associated cancers: current progress and perspectives. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94(1): e211.

- Khan, N.G.; Correia, J.; Adiga, D.; Rai, P.S.; Dsouza, H.S.; Chakrabarty, S.; Kabekkodu, S.P. A comprehensive review on the carcinogenic potential of bisphenol A: clues and evidence. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 19643–19663. [CrossRef]

- Pellerin, E.; Caneparo, C.; Chabaud, S.; Bolduc, S.; Pelletier, M. Endocrine-disrupting effects of bisphenols on urological cancers. Environ. Res. 2021, 195, 110485. [CrossRef]

- Vandenberg, L.N.; Hauser, R.; Marcus, M.; Olea, N.; Welshons, W.V. Human exposure to bisphenol A (BPA). Reprod. Toxicol. 2007, 24, 139–177. [CrossRef]

- Gorini, F.; Bustaffa, E.; Coi, A.; Iervasi, G.; Bianchi, F. Bisphenols as Environmental Triggers of Thyroid Dysfunction: Clues and Evidence. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2654. [CrossRef]

- Santin, A.P.; Furlanetto, T.W. Role of Estrogen in Thyroid Function and Growth Regulation. J. Thyroid. Res. 2011, 2011, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, F.; Zhang, J.; Hao, L.; Jiang, J.; Dang, L.; Mei, D.; Fan, S.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, L. Bisphenol A and estrogen induce proliferation of human thyroid tumor cells via an estrogen-receptor-dependent pathway. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2017, 633, 29–39. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, F.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, L. Higher urinary bisphenol A concentration and excessive iodine intake are associated with nodular goiter and papillary thyroid carcinoma. Biosci. Rep. 2017, 37. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, C.; Liu, Z.; Hao, L.; Fan, S.; Jiang, F.; Xie, Y.; et al. Low dose of Bisphenol A enhance the susceptibility of thyroid carcinoma stimulated by DHPN and iodine excess in F344 rats. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 69874–69887. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ying, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Feng, Y.; Liang, J.; Song, H.; Wang, Y. Bisphenol A exposure and risk of thyroid nodules in Chinese women: A case-control study. Environ. Int. 2019, 126, 321–328. [CrossRef]

- Gentilcore, D.; Porreca, I.; Rizzo, F.; Ganbaatar, E.; Carchia, E.; Mallardo, M.; De Felice, M.; Ambrosino, C. Bisphenol A interferes with thyroid specific gene expression. Toxicology 2013, 304, 21–31. [CrossRef]

- EFSA. EFSA's Scientific Opinion on Bisphenol A. Scientific Opinion on the risks to public health related to the presence of bisphenol A (BPA) in foodstuffs.

- Vom Saal FS ea. The Conflict between Regulatory Agencies over the 20,000-Fold Lowering of the Tolerable Daily Intake (TDI) for Bisphenol A (BPA) by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). . Environ Health Perspect2024.

- Birnbaum, L.S.; Aungst, J.; Schug, T.T.; Goodman, J.L. Working Together: Research- and Science-Based Regulation of BPA. Environ. Heal. Perspect. 2013, 121, a206–a207. [CrossRef]

- EFSA. Bisphenol A. In: Authority EFS, editor. https://wwwefsaeuropaeu/en/topics/topic/bisphenol2025.

- Wang, Y.; Su, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Z. Bisphenol A exposure enhances proliferation and tumorigenesis of papillary thyroid carcinoma through ROS generation and activation of NOX4 signaling pathways. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 292, 117946. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Guo, N.; Jin, H.; Liu, R.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, C.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, G.; Xiao, M.; Wu, S.; et al. Bisphenol A drives di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate promoting thyroid tumorigenesis via regulating HDAC6/PTEN and c-MYC signaling. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 425, 127911. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-Y.; Xie, R.-H.; Li, P.-H.; Chen, C.-Y.; You, B.-H.; Sun, Y.-C.; Chou, C.-K.; Chang, Y.-H.; Lin, W.-C.; Chen, G.-Y. Environmental Exposure to Bisphenol A Enhances Invasiveness in Papillary Thyroid Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26. [CrossRef]

- Durante, C.; Hegedüs, L.; Czarniecka, A.; Paschke, R.; Russ, G.; Schmitt, F.; Soares, P.; Solymosi, T.; Papini, E. 2023 European Thyroid Association Clinical Practice Guidelines for thyroid nodule management. Eur. Thyroid. J. 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Symonds, C.J.; Seal, P.; Ghaznavi, S.; Cheung, W.Y.; Paschke, R. Thyroid nodule ultrasound reports in routine clinical practice provide insufficient information to estimate risk of malignancy. Endocrine 2018, 61, 303–307. [CrossRef]

- Kitahara, C.M.; Sosa, J.A. The changing incidence of thyroid cancer. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 646–653. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Pei, J.; Xu, M.; Shu, T.; Qin, C.; Hu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, M.; Zhu, C. Changing incidence and projections of thyroid cancer in mainland China, 1983–2032: evidence from Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. Cancer Causes Control. 2021, 32, 1095–1105. [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Filho, A.; Lortet-Tieulent, J.; Bray, F.; Cao, B.; Franceschi, S.; Vaccarella, S.; Dal Maso, L. Thyroid cancer incidence trends by histology in 25 countries: A population-based study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 225–234. [CrossRef]

- Xing, M. Molecular pathogenesis and mechanisms of thyroid cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 184–199. [CrossRef]

- van Dijk JG, Pondaag W, Malessy MJ. Botulinum toxin and the pathophysiology of obstetric brachial plexus lesions. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;49(4):318; author reply -9.

- Dairkee, S.H.; Seok, J.; Champion, S.; Sayeed, A.; Mindrinos, M.; Xiao, W.; Davis, R.W.; Goodson, W.H. Bisphenol A Induces a Profile of Tumor Aggressiveness in High-Risk Cells from Breast Cancer Patients. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 2076–2080. [CrossRef]

- Bilancio, A.; Bontempo, P.; Di Donato, M.; Conte, M.; Giovannelli, P.; Altucci, L.; Migliaccio, A.; Castoria, G. Bisphenol A induces cell cycle arrest in primary and prostate cancer cells through EGFR/ERK/p53 signaling pathway activation. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 115620–115631. [CrossRef]

- Rajoria, S.; Suriano, R.; Shanmugam, A.; Wilson, Y.L.; Schantz, S.P.; Geliebter, J.; Tiwari, R.K. Metastatic Phenotype Is Regulated by Estrogen in Thyroid Cells. Thyroid® 2010, 20, 33–41. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.G.; Vlantis, A.C.; Zeng, Q.; van Hasselt, C.A. Regulation of Cell Growth by Estrogen Signaling and Potential Targets in Thyroid Cancer. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2008, 8, 367–377. [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.M.; Wang, Y.D.; Chai, F.; Zhang, J.; Lv, S.; Wang, J.X.; Xi, Y. Estrogen enhances the proliferation, migration, and invasion of papillary thyroid carcinoma via the ERα/KRT19 signaling axis. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2024, 48, 653–670. [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.-W.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Gou, X.; Qiu, Y.-B.; Liu, Z.-M. [Effects of UHRF1 on Estrogen Receptor and Proliferation, Invasion and Migration of BCPAP Cells in Thyroid Papillary Carcinoma].. 2020, 51, 325–330.

- Dai, Y.-J.; Qiu, Y.-B.; Jiang, R.; Xu, M.; Liao, L.-Y.; Chen, G.G.; Liu, Z.-M. Concomitant high expression of ERα36, GRP78 and GRP94 is associated with aggressive papillary thyroid cancer behavior. Cell. Oncol. 2018, 41, 269–282. [CrossRef]

- Fan, D.; Liu, S.Y.W.; van Hasselt, C.A.; Vlantis, A.C.; Ng, E.K.W.; Zhang, H.; Dong, Y.; Ng, S.K.; Chu, R.; Chan, A.B.W.; et al. Estrogen Receptor α Induces Prosurvival Autophagy in Papillary Thyroid Cancer via Stimulating Reactive Oxygen Species and Extracellular Signal Regulated Kinases. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, E561–E571. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; He, L.; Sun, W.; Qin, Y.; Dong, W.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, H. miRNA-299-5p regulates estrogen receptor alpha and inhibits migration and invasion of papillary thyroid cancer cell. Cancer Manag. Res. 2018, ume 10, 6181–6193. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Song, Y.S.; Lee, H.S.; Lin, C.-W.; Lee, J.; Kang, Y.E.; Kim, S.-K.; Kim, S.-Y.; Park, Y.J.; Park, J.-I. Estrogen-related receptor alpha promotes thyroid tumor cell survival via a tumor subtype-specific regulation of target gene networks. Oncogene 2024, 43, 2431–2446. [CrossRef]

- Mercado, M. The Role of Androgen Receptors in Thyroid Cancer Biology: Beyond Sexual Dimorphism. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 109, e868–e869. [CrossRef]

- Elmi, M.A.; Motamed, N.; Picard, D. Proteomic Analyses of the G Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor GPER1 Reveal Constitutive Links to Endoplasmic Reticulum, Glycosylation, Trafficking, and Calcium Signaling. Cells 2023, 12, 2571. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Effects of Bisphenol A on Thyroid Cell Viability. Thyroid cell viability was measured after exposure to increasing BPA concentrations (0.1–1.0 µg/mL) for 24 and 48 h in Nthy-ori 3-1, TPC-1, and BCPAP cell lines, using the Trypan Blue exclusion assay (upper panels) and PrestoBlue® metabolic assay (lower panels). Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. *p ≤ 0.05, *p ≤ 0.001 vs. control.

Figure 1.

Effects of Bisphenol A on Thyroid Cell Viability. Thyroid cell viability was measured after exposure to increasing BPA concentrations (0.1–1.0 µg/mL) for 24 and 48 h in Nthy-ori 3-1, TPC-1, and BCPAP cell lines, using the Trypan Blue exclusion assay (upper panels) and PrestoBlue® metabolic assay (lower panels). Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. *p ≤ 0.05, *p ≤ 0.001 vs. control.

Figure 2.

Effect of Bisphenol A on Thyroid Cell Proliferation. Cell proliferation was assessed in Nthy-ori 3-1, TPC-1, and BCPAP cell lines after 48 h of exposure to BPA (0.8 and 1.0 µg/mL) using an EdU incorporation assay. The bars represent the proportion of EdU-positive nuclei under each condition. Representative fluorescence images showing proliferating cells labeled with EdU (red) and nuclei counterstained with Hoechst (blue). Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. p ≤ 0.05 vs. control.

Figure 2.

Effect of Bisphenol A on Thyroid Cell Proliferation. Cell proliferation was assessed in Nthy-ori 3-1, TPC-1, and BCPAP cell lines after 48 h of exposure to BPA (0.8 and 1.0 µg/mL) using an EdU incorporation assay. The bars represent the proportion of EdU-positive nuclei under each condition. Representative fluorescence images showing proliferating cells labeled with EdU (red) and nuclei counterstained with Hoechst (blue). Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. p ≤ 0.05 vs. control.

Figure 3.

Dose-Dependent Acceleration of Wound Closure by Bisphenol A in Nthy-ori 3-1 Thyroid Cells. Cell migration was assessed following exposure to 0.8 and 1.0 µg/mL BPA. Wound closure was evaluated at 0, 6, 12, 18, and 24 h, relative to the control condition. Representative images illustrate the progressive closure of the cell-free area, and the corresponding quantified open area (%) curves depict the kinetics of wound closure, demonstrating the stimulatory effect of BPA on Nthy-ori 3-1 cell migration.

Figure 3.

Dose-Dependent Acceleration of Wound Closure by Bisphenol A in Nthy-ori 3-1 Thyroid Cells. Cell migration was assessed following exposure to 0.8 and 1.0 µg/mL BPA. Wound closure was evaluated at 0, 6, 12, 18, and 24 h, relative to the control condition. Representative images illustrate the progressive closure of the cell-free area, and the corresponding quantified open area (%) curves depict the kinetics of wound closure, demonstrating the stimulatory effect of BPA on Nthy-ori 3-1 cell migration.

Figure 4.

Dose-Dependent Acceleration of Wound Closure by Bisphenol A in TPC-1 Thyroid Cells. Cell migration was assessed following exposure to 0.8 and 1.0 µg/mL BPA. Wound closure was evaluated at 0, 6, 12, 18, and 24 h, relative to the control condition. Representative images illustrate the progressive closure of the cell-free area, and the corresponding quantified open area (%) curves depict the kinetics of wound closure, demonstrating the stimulatory effect of BPA on TPC-1 cell migration. .

Figure 4.

Dose-Dependent Acceleration of Wound Closure by Bisphenol A in TPC-1 Thyroid Cells. Cell migration was assessed following exposure to 0.8 and 1.0 µg/mL BPA. Wound closure was evaluated at 0, 6, 12, 18, and 24 h, relative to the control condition. Representative images illustrate the progressive closure of the cell-free area, and the corresponding quantified open area (%) curves depict the kinetics of wound closure, demonstrating the stimulatory effect of BPA on TPC-1 cell migration. .

Figure 5.

Dose-Dependent Acceleration of Wound Closure by Bisphenol A in BCPAP Thyroid Cells. Cell migration was assessed following exposure to 0.8 and 1.0 µg/mL BPA. Wound closure was evaluated at 0, 12, 24, 48 and 72 h, relative to the control condition. Representative images illustrate the progressive closure of the cell-free area, and the corresponding quantified open area (%) curves depict the kinetics of wound closure, demonstrating the stimulatory effect of BPA on BCPAP cell migration.

Figure 5.

Dose-Dependent Acceleration of Wound Closure by Bisphenol A in BCPAP Thyroid Cells. Cell migration was assessed following exposure to 0.8 and 1.0 µg/mL BPA. Wound closure was evaluated at 0, 12, 24, 48 and 72 h, relative to the control condition. Representative images illustrate the progressive closure of the cell-free area, and the corresponding quantified open area (%) curves depict the kinetics of wound closure, demonstrating the stimulatory effect of BPA on BCPAP cell migration.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).