These wavefunctions successfully predict observable quantities such as energy levels and transition probabilities. However, they remain disconnected from any physical explanation of why these orbitals form, what shapes them, and how they relate to the field reality of the atom itself. QM treats the wavefunction as an abstract probabilistic object — a tool for computing measurement outcomes — but not as a physically real field. The only link between theory and observation is the “collapse” during measurement, yet even that remains unexplained in terms of causality or mechanism. The actual shape of the atom — its field distribution in space — has no dynamic cause in standard quantum theory. Traditional QM implicitly assumes that orbital shapes arise from an interaction between the electron and the proton via the Coulomb potential. But it completely neglects the role of the surrounding field — the background entropy — that constantly interacts with the atom. It assumes that the electron absorbs photons from the environment and “jumps” from one level to another, without explaining how the field shape changes or what controls the spatial transformation of the orbital. S-Theory provides this missing insight. We propose that the hydrogen atom is not a fixed structure but a recursive entropy engine, continuously interacting with its surroundings. We model the hydrogen atom as a recursive, entropy-guided relaxer: a local thermodynamic entropy density field, S(r), organizes the orbital geometry, and discrete environmental inputs drive transitions between S-max macrostates.

1.1. Generalized Definition of Entropy in S-Theory

S-Theory begins with a primordial entropic background,

: an unbounded, unstructured field composed of an infinite number of

entropic quanta, the fundamental microscopic elements of the theory, as indicated in

Figure 1. For mathematical convenience, individual entropic quanta are treated as elements of a complex potential field, whose real and imaginary components capture correlated and uncorrelated contributions. This allows wave-like interference and geometry to emerge from recursion, without postulating a separate quantum wavefunction. In

, these quanta fluctuate freely without correlation or geometry, representing maximal entropy. Physical structure arises when subsets of these quanta become correlated, giving rise to three distinct correlation classes: (i)

Sthermal — minimally correlated entropic quanta that generate thermal and background fluctuations; (ii)

SEM — highly correlated entropic quanta that organize into electromagnetic-like field structures; and (iii)

Score — maximally correlated entropic quanta that form stable, localized cores associated with mass. Energy and mass are not primitive; they emerge from these different correlation states.

SEM corresponds to organized field energy,

Score to localized mass structures, while

Sthermal represents background heat and noise. We define the local entropy at position

by counting the number of possible microscopic arrangements of entropic quanta within a finite local cell, subject to their correlation structure and boundary geometry. For 2D approximation,

Here, is the total number of distinguishable microconfigurations of entropic quanta, decomposed into three contributions given by

corresponding to Sthermal, SEM, and Score, respectively.

counts micro configurations of entropic quanta that produce macroscopic thermal energy through random, minimally correlated arrangements.

counts field-structured micro configurations of entropic quanta arising from correlations linked to electric charges and magnetic field organization.

counts mass-forming micro configurations of entropic quanta, representing maximally correlated clusters that behave as stable cores.

In regions dominated by Sthermal, the definition reduces to the classical Boltzmann form. In structured regions, correlated quanta (SEM and Score) reduce the number of accessible micro configurations, giving rise to organized energy fields and mass. This generalized entropy definition serves as the foundational expression for all subsequent derivations in S-Theory, unifying thermal entropy, electromagnetic field structure, and mass within a single entropic counting framework that encompasses both structured and unstructured components of physical reality.

This generalized definition does more than extend Boltzmann’s counting—it introduces geometry as an intrinsic outcome of entropy correlations. In classical statistical mechanics, entropy quantifies the number of microstates consistent with a given macroscopic energy, but it carries no information about spatial form. In S-Theory, however, the correlated entropic quanta (SEM and Score) not only reduce accessible micro configurations but also organize them in space, producing stable geometric patterns. These correlated fields act as sculptors of structure: Score defines localized cores, while SEM defines coherent surrounding fields, together giving rise to shapes such as atomic orbitals, molecular structures, and eventually large-scale cosmic forms. In this way, geometry itself is an entropic construct, emerging directly from the distribution and correlation of entropic quanta, not imposed by external equations. This shift—from entropy as a scalar descriptor to entropy as a shaper of structure—is the central conceptual advance of S-Theory.

To generate orbital fields in 2D, we work with the dimensionless capacity field

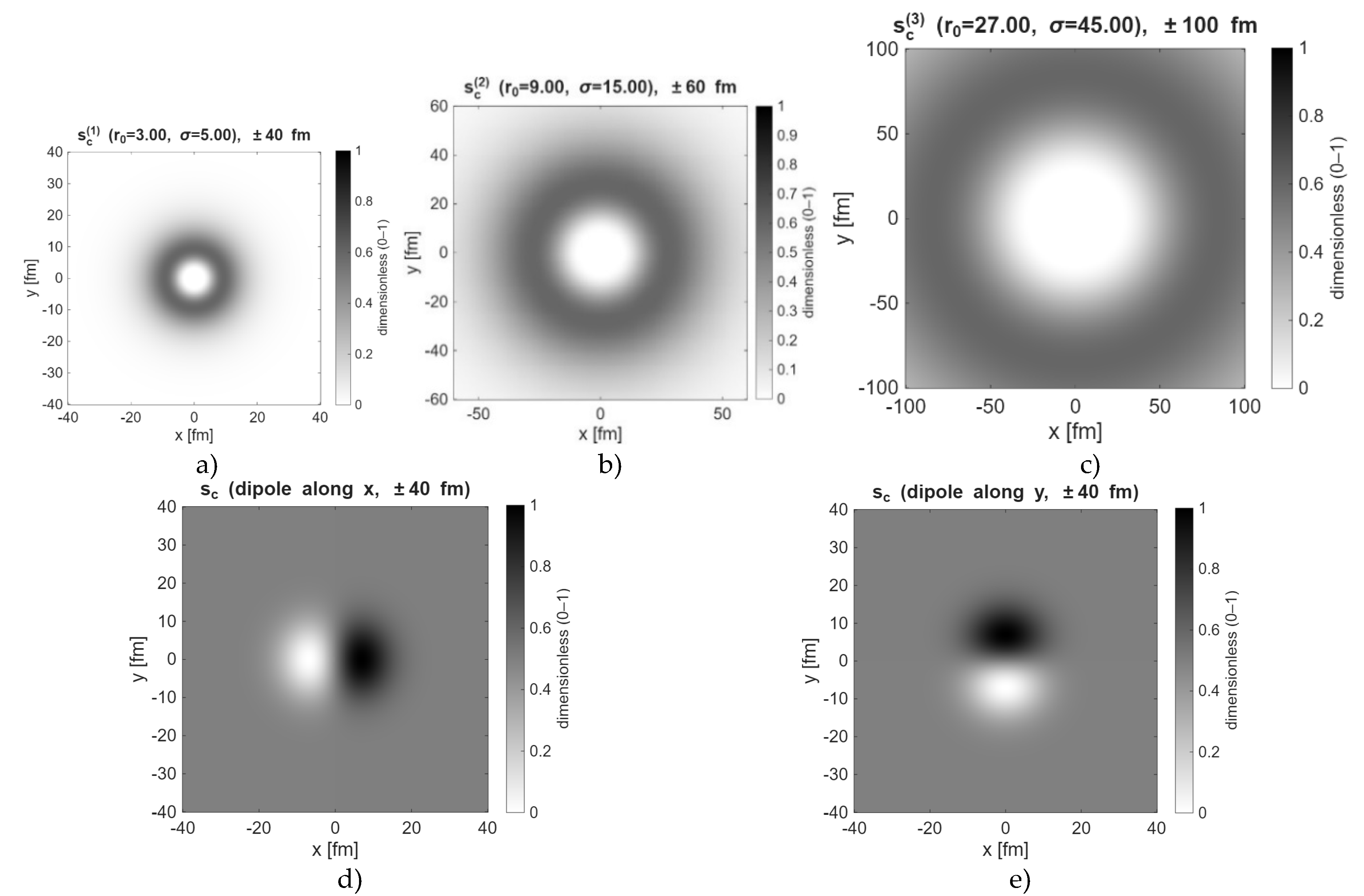

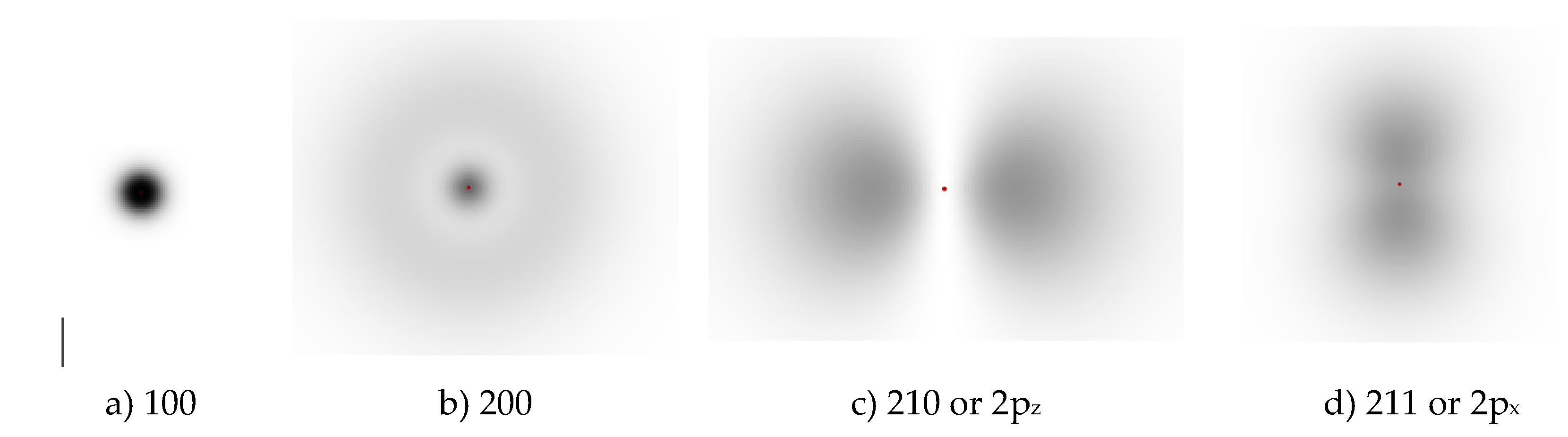

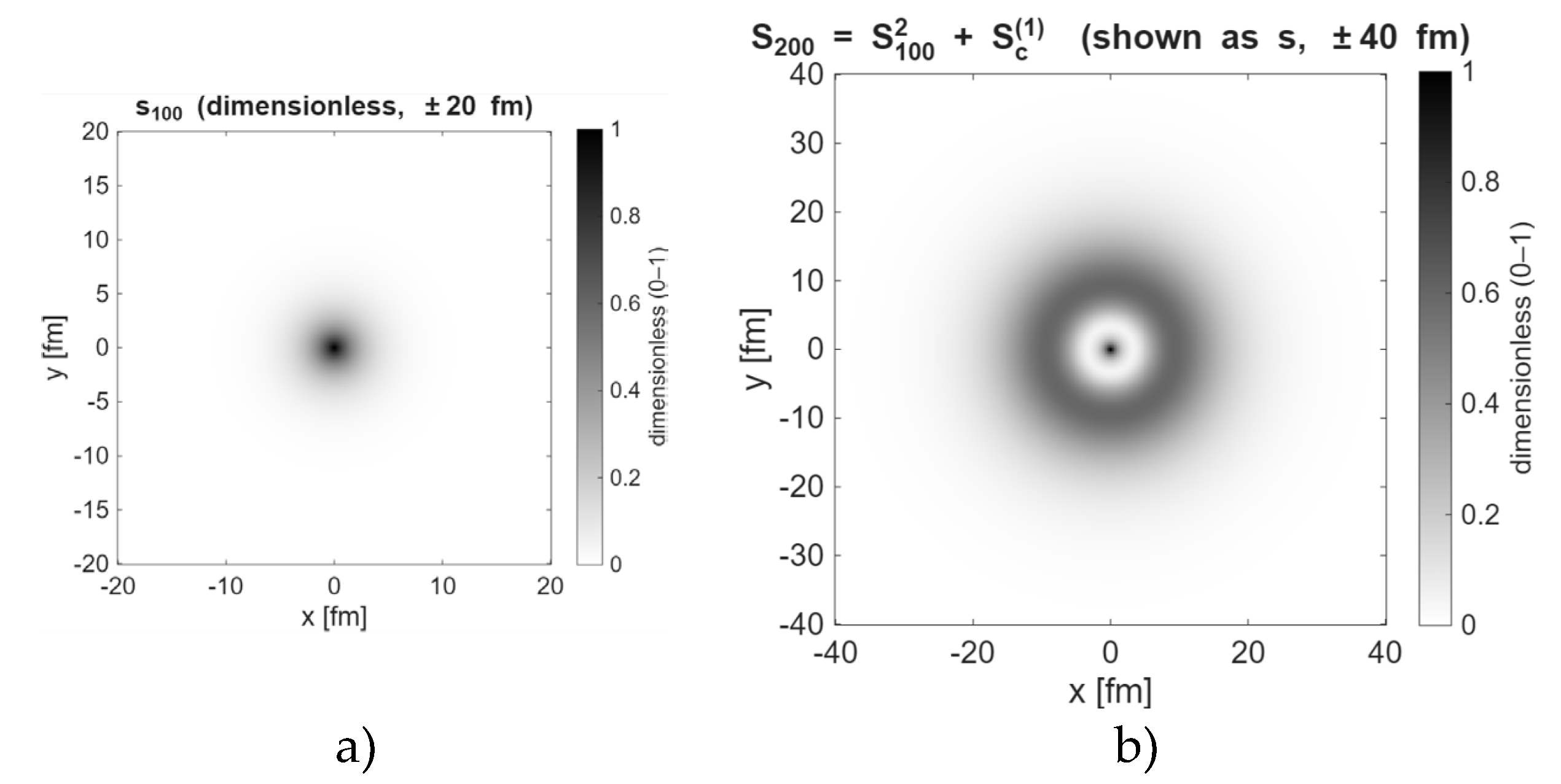

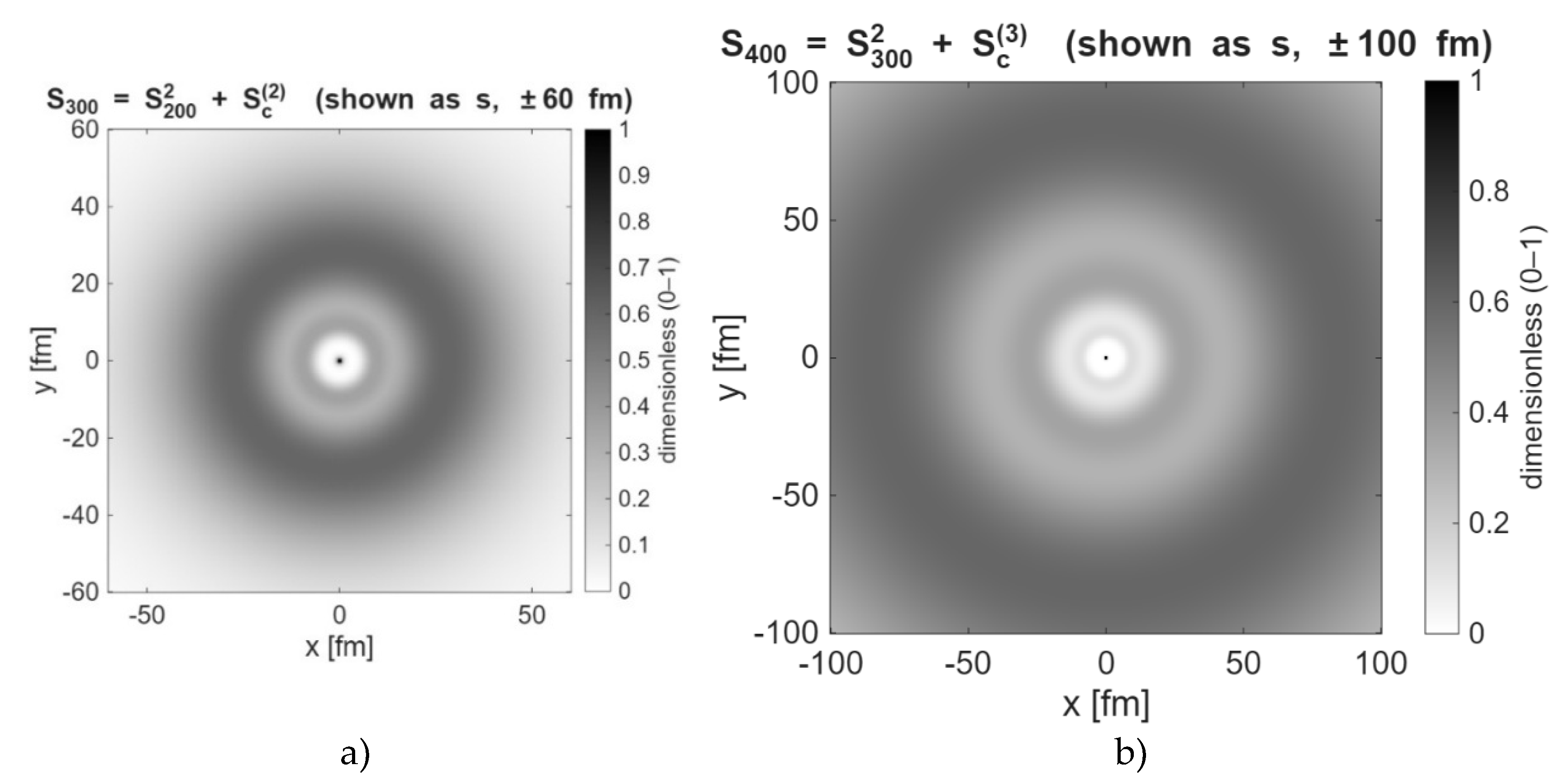

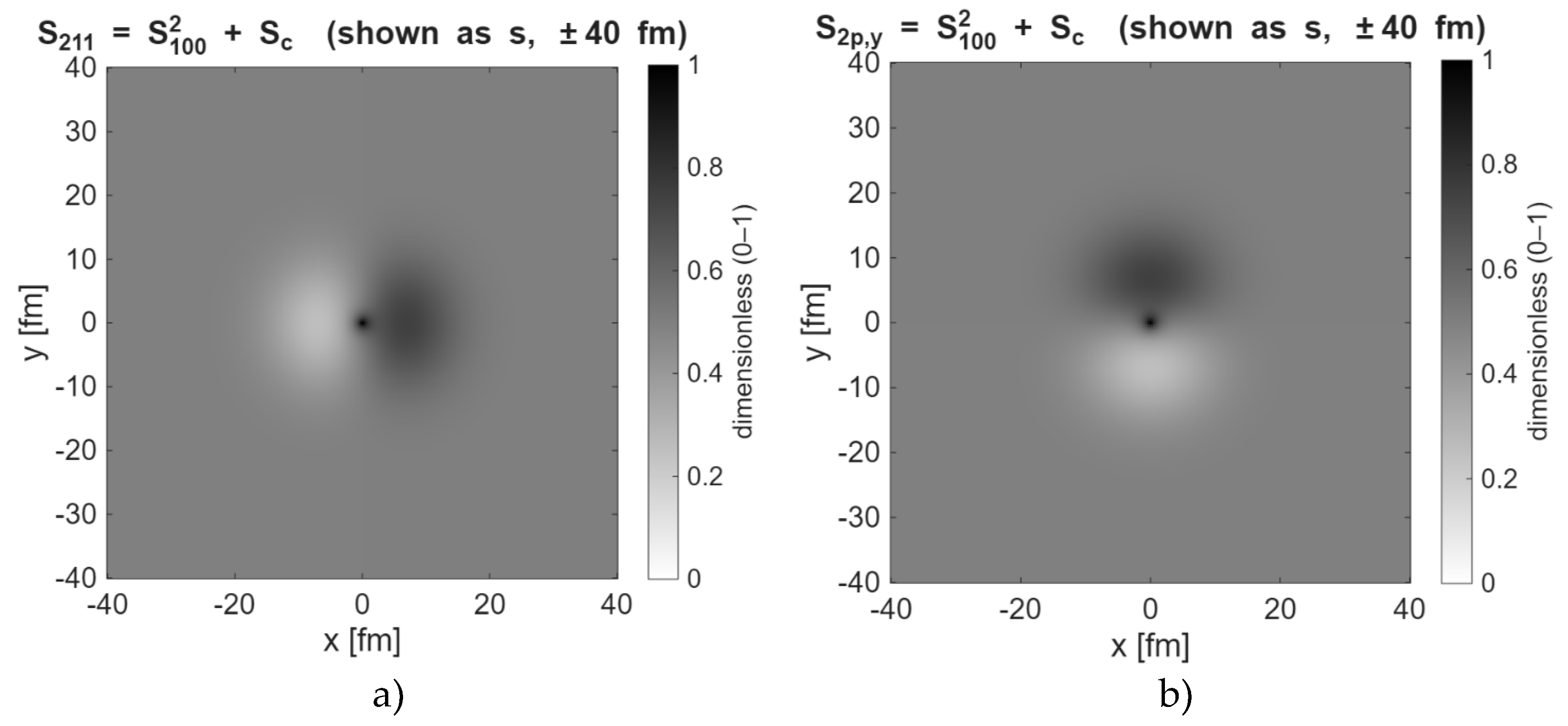

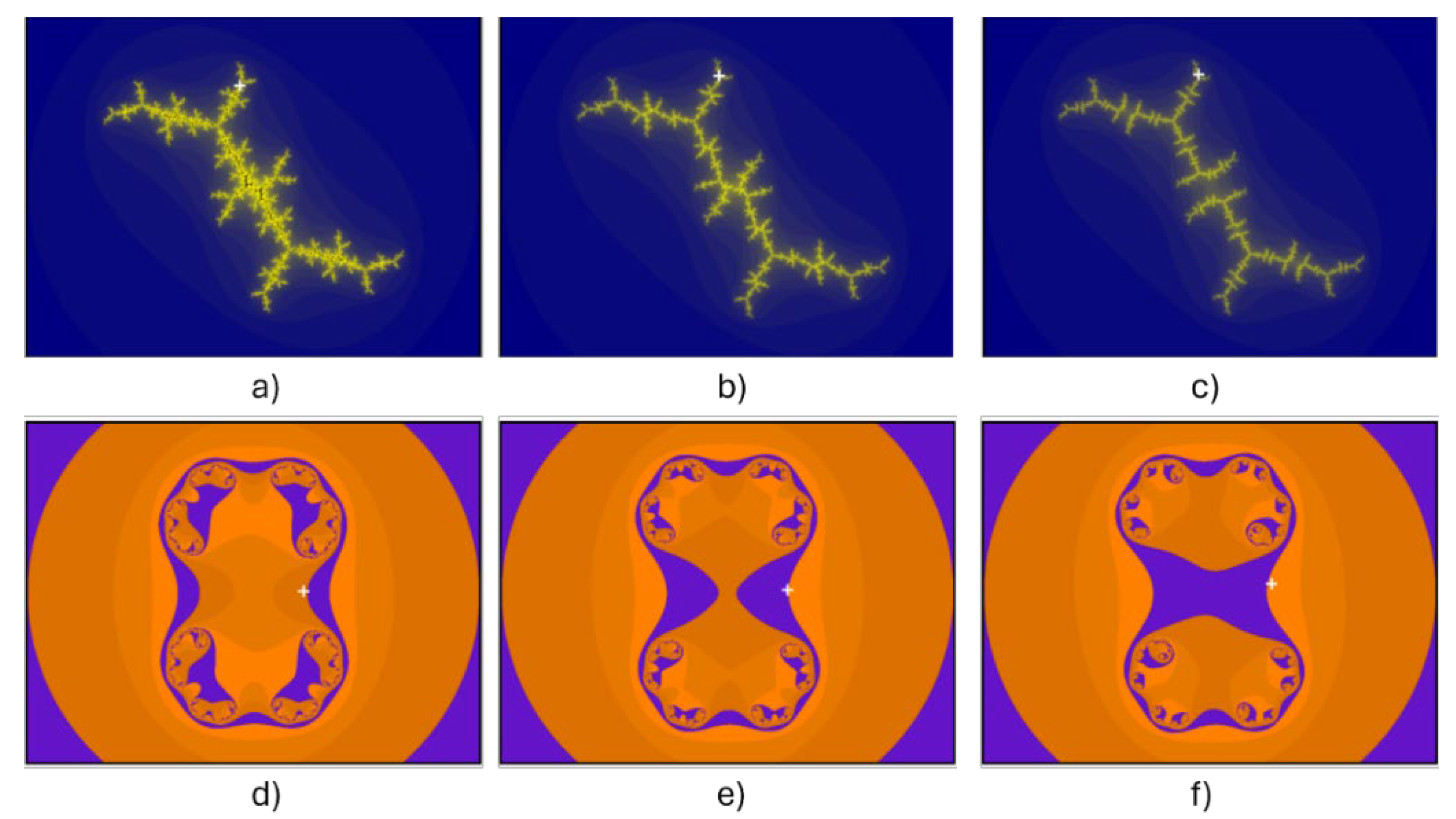

where S0 is a fixed ground-state reference (peak of the total entropy density). Intuitively, the fraction of non-dimensional entropic density s ≈1 marks locations with many compatible micro-configurations available under the same mesoscopic constraints (high local accessibility), while s ≈ 0 marks nodes (strong constraints). Environmental influence is encoded by a driver sc(r) that specifies where capacity can be unlocked (e.g., rings for s-like and dipoles for p-like structure). The state update is the local, pointwise map given by the recursive fractal equation,

interpreted as a constrained-maximum-entropy relaxation toward the next S-max pattern. Here, sn = S/S0 is the non-dimensional entropy density field s ∈ [0,1] at iteration n (initialized, e.g., with a 1s-like ground-state profile), sc is a non-dimensional source term representing entropy input from the surrounding fields (constructed from the Sthermal and/or SEM components), and sn+1 is the updated field; under iteration, the map approaches a high-entropy configuration smax. The superlinear self-term s2 captures cooperative, contrast-enhancing growth—peaks tend to sustain, nodes persist—so that, together with a rim-localized sc, the evolution is edge-driven (consistent with the annular area scaling A∝R2) rather than a global smear. Thus, the recursive equation (3) is essentially a phenomenological constrained-entropy ascent toward the next Smax macrostate.

Throughout, we compare shapes of normalized

s(r) to the familiar ∣ψ∣

2 patterns for hydrogen, but we do not identify

s(r) with the quantum wavefunction. All figures display dimensionless

s(r) (axes in

fm); physical units are restored only when reporting observables. The non-dimensional recursion (equation 3- pointwise square) is implemented on a uniform two-dimensional grid; the resulting fields are analyzed in

Section 4, where we detail the numerical conventions (choice of the fixed reference scale

S0, discretization, area element

dA, and recovery of physical units for observables via

S=sS0 (Dimensional equivalence entropy). Equation (3) is equivalent to the dimensional form

Sn+1=

Sn2/S0+Sc, where

S0 is the fixed baseline scale defined in

Section 4. This makes the role of units explicit while leaving the computation in non-dimensional variables.

In this paper, we revisit the hydrogen atom — the simplest quantum system — not as a particle-in-a-potential but as a recursive entropy system. We show that each orbital state corresponds to a recursive entropic amplification of the base field s(r), guided by boundary interaction from the surrounding. Using both mathematical formulation and simulation, we demonstrate that S-Theory not only reproduces known orbital structures, but also reveals why they form — linking entropy, structure, and energy into a unified physical picture. This reformulation enables us to retain all predictive successes of quantum mechanics while introducing deeper physical meanings for phenomena such as orbital quantization, ground and excited states, collapse and measurement, entanglement between atoms, and the link between thermodynamic and quantum domains. Our goal is to demonstrate that the quantum behavior of hydrogen is not mysterious, but an inevitable result of recursive entropy optimization in a thermodynamic universe.

Summary of methods

We implemented S-Theory’s recursive entropic framework on two-dimensional hydrogen orbitals using non-dimensional entropy density fields normalized to a ground-state reference. Orbital structures were generated by iteratively applying the recursive update rule with pre-specified drivers (ring-type for s-states, dipole-type for p-states) without case-by-case fitting. Numerical simulations were carried out on uniform grids, restoring physical units only when reporting observables. Predicted orbital geometries and nodal structures were then compared to standard quantum mechanical solutions and proposed photoionization microscopy data, providing falsifiable criteria for agreement or refutation.