1. Introduction

The transformation of normal epithelial cells to cancerous cells can be caused by multiple factors like genetic mutations, environmental factors, and lifestyle [

1]. One of the idiosyncratic type of head and neck cancers Polymorphous Adenocarcinoma (PAC), also known as terminal duct or lobular carcinoma, was recognized as a distinct entity by Batsakis et al. in the year 1983 [

2,

3]. In the past, this type of cancer was inaccurately categorized using different terms because of its complex histological appearance and the unclear distinguishing features. PAC is a malignant epithelial tumor with a potential for a distant metastasis and it has a diverse histopathology. Due its unique histology and prognosis, the World Health Organization PAC was replaced by polymorphous adenocarcinoma (PAC) due to poor prognosis in some cases [

4]. This specific tumor needs further research regarding its etiology and treatment since it has the ability to spread and has a complex clinical management [

5].

The malignant tumor known as polymorphous adenocarcinoma (PAC) usually appears in the minor salivary glands of the oral cavity[

6]. In order to learn more about the events behind tumor formation and neoplastic proliferation, Rosa et al. researched the expression of growth factors and receptors in PAC. Collectively with their receptors, PDGF-A and FGF-2 may migrate through the cytoplasm from the cell surface and adhere to chromatin in the nucleus, which directly influences gene expression[

7]. With a slight tendency toward females, it mainly affects individuals between the ages of 50 and 70. PAC is low-grade but it can still cause local recurrence and in some cases spread to distant sites or nearby lymph nodes. Compared to other types of salivary gland tumors PAC is a relatively uncommon malignancy of the glands even though its exact incidence varies by region and demographic [

8].

Various types of malignancies can develop from salivary glands. Since morphological characteristics frequently overlap between them, they are frequently difficult to diagnose [

9]. Polymorphous adenocarcinoma shares morphological similarities with adenoid cystic carcinoma and cellular pleomorphic adenoma, particularly in small biopsy specimens. Accurate diagnosis is crucial, as the prognosis, treatment, and follow-up for these conditions differ. p63+ve/p40-ve immunoprofile should assist distinguish PACs from adenoid cystic carcinomas and pleomorphic adenomas [

10,

11].

In their most extensive series, Patel et al. documented 460 cases of head and neck PAC, with a mean age of 61.3 years at diagnosis, a female propensity (female-to-male ratio of 2.15:1), and a 25% likelihood of regional metastases and a 4.3% chance of distant metastases [

12]. The overall recurrence rate was reported to be 19% in a literature review of 456 PAC cases by Kimple et al. Following the initial resection, recurrences were reported up to 24 years later. [

13] PAC was earlier thought to be primarily a locally invasive tumor with a low potential for metastatic spread. But, the rate of recurrence for PAC are significant at about 33%, and metastatic spread or even transformation to a high-grade adenocarcinoma have been recorded with adequate long-term follow-up [

14,

15]. Consequently, we think that although while polymorphous adenocarcinoma is much less aggressive than, say, adenoid cystic carcinoma, it is nonetheless a real cancer that can be lethal in a small percentage of cases. Hence, periodic observation all through the life is recommended [

16].

The size and location of the tumor, the existence of perineural invasion and the effectiveness of surgical resection are some of the variables that can affect the prognosis of PAC. A better prognosis is linked to a full surgical excision with distinct margins [

14]. Adjuvant radiation is frequently used following surgical resection with positive margins and advanced-stage disease to lower the risk of local recurrence. For PAC chemotherapy is typically ineffective. Radiation therapy may also be used palliatively to reduce symptoms and enhance quality of life. To remove the regional lymph nodes a neck dissection may be done if there is lymph node involvement or a high risk of lymph node metastasis [

17]. Individuals who exhibit ulceration, bleeding, or pain may not have a more aggressive course or be inclined to suffer recurrences [

18]. Prognosis and overall survival of patients with PAC can be enhanced by early detection and treatment.

Histologically, PAC tumors showed bland, homogeneous nuclei, nonencapsulated, infiltrative borders, and wildly unpredictable growth patterns. They were solid, papillary, tubular, cribriform, microcystic, pseudoadenoid cystic, fascicular, single-file, and strand-like patterns. Furthermore, larger areas of papillary growth were noticed [

19]. A targetoid arrangement is often produced by the concentric arrangement of tumor cells around a central nidus which is frequently observed to be a tiny nerve bundle [

18]. Salivary gland cribriform adenocarcinoma (CASG) is characterized by glomeruloid appearance, optically clear nuclei, and cribriform and solid patterns. The amount of cribriform and papillary patterns should be clearly recorded because the data seems to have prognostic importance [

5].

In PAC, a hyalinized, somewhat eosinophilic stroma that occasionally showed myxoid degeneration envelops the tumor cells. Additionally, a distinctive slate gray-blue stroma is commonly seen. Two main mistake patterns were identified by Seethala and team whilst talking about distinguishing palatal pleomorphic adenoma (PAC) from other tumors. The first is the inability to differentiate PAC, which is monophasic, from biphasic malignancies, such as adenoid cystic carcinoma and epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma. Unlike the distinct biphasic structure noted in other cancers, myoepithelial differentiation in PAC is modest and only visible on immunohistochemical staining. Second, tumors reinterpreted as adenocarcinoma, NOS, failed to exhibit the distinctive nuclear characteristics of PAC, such as monomorphic, ovoid nuclei with fragile membranes [

14].

PAC neoplastic cells have moderate to strong immunohistochemical reactivity to Bcl-2, carcinoembryonic antigen, vimentin, cytokeratin, and S-100 protein.[

10] According to the expression of CKs [

7,

8,

18], cells near junction between the acini and intercalated duct are the source of origin for PAC. Numerous studies have demonstrated that glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) does not react with PAC, which is helpful in differentiating it from pleomorphic adenoma [

17] Vimentin may be the sole marker allowing distinction between PAC and ACC [

8].

Despite the great advancements in the field of oncology, there are still many ambiguities and lack of knowledge regarding PAC which usually tends to complicate its diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Our aim and objective for this review is to provide a detailed understanding of its clinical features, histological presentation, immunohistochemical markers which can help in differential diagnosis, treatment planning, follow up, and distant metastasis

2. Materials and Methods

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria was followed to conduct this systematic review.

Literature Search

The designated databases PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Library, and Google Scholar were used by advanced searches for articles published between 2013 and 2023 to perform a literature search on studies that investigated the prevalence of polymorphous adenocarcinoma.

Keywords used for search strategy

Table 1.

Keywords used in advanced search.

Table 1.

Keywords used in advanced search.

| Concept 1 |

Concept 2 |

Concept 3 |

Salivary gland neoplasms Minor salivary glands Recurrent salivary gland cancer Epidemiology of salivary gland cancers Therapeutic advancements in salivary gland tumors Biomarkers in salivary gland tumors |

|

Differential diagnosis of PAC Genetic alterations in PAC Management of recurrent PAC |

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Table 2.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Table 2.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| |

Inclusion Criteria |

Exclusion Criteria |

| Study Design |

Case Reports

Cohort studies

Full-text articles published in a peer-reviewed journal

Minimal sample size of 20 |

Systematic Review, Confidence abstracts, review articles, non-English articles, studies involving different types of tumors, studies involving non-humans |

| Population |

Studies involving patients with recurrence of the disease.

Studies with a comparison group using different types of treatment.

Studies involving patients affected by PAC and metastasis. |

Studies involving patients with other concurrent malignancies.

Studies involving patients who have had previous salivary gland surgeries or radiation therapy might have altered anatomy or treatment responses. |

| Outcomes |

Studies reporting confirmed diagnosis of PAC.

Studies involving patients undergoing surgery treatment, radiation therapy

Studies involving patients at the initial stage of the disease.

Studies involving patients' survival rate after the recurrence of the disease.

Studies with a follow-up duration. |

Studies with incomplete or insufficient data on the specified outcomes. |

Risk of bias (quality assessment)

AHRQ standards and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) are two instruments used to evaluate the calibre of non-randomized research, including observational studies. The process of translating NOS scores to AHRQ standards entails assigning star ratings to AHRQ quality categories, which are commonly characterized as "Good," "Fair," and "Poor." Studies that received three or four stars in the selection domain, one or two stars in the comparability domain, and two or three stars in the result or exposure domain were awarded a "Good" rating. A "Fair" rating was assigned to studies that received two stars in the selection domain, one or two stars in the comparability area, and two or three stars in the result or exposure domain. Studies were deemed "Poor" if they received 0 or 1 stars in the outcome/exposure domain, 0 or 1 star in the comparability domain, or 0 or 1 star in the selection domain.

Table 3.

Risk of Bias.

| Author/Year |

Selection |

Comparability |

Outcomes |

Score |

Representativeness

of the exposed

cohort |

Selection of the

non-exposed

cohort |

Determination of exposure |

Presence of

outcome of interest

before the study |

Comparison of

cohorts |

Outcome |

Long follow-ups |

Adequacy of

follow ups |

| (Hay et al., 2019) |

★ |

☆ |

★ |

★ |

★★ |

★ |

★ |

★ |

9 |

| (Mimica et al., 2019) |

★ |

☆ |

☆ |

★ |

★☆ |

★ |

★ |

★ |

6 |

| (De Araujo et al., 2013b) |

☆ |

★ |

★ |

★ |

★☆ |

★ |

☆ |

★ |

6 |

| (Castle et al., 1999) |

☆ |

★ |

★ |

☆ |

☆☆ |

★ |

★ |

★ |

5 |

| (Ulku et al., 2017) |

☆ |

★ |

★ |

★ |

★☆ |

★ |

★ |

★ |

7 |

| (Adam J Kimple et al2014) |

★ |

★ |

★ |

★ |

★★ |

★ |

★ |

★ |

9 |

| (KR Chatura 2015) |

☆ |

★ |

★ |

☆ |

☆☆ |

★ |

★ |

★ |

5 |

| (Matthew s et al 2009) |

★ |

☆ |

★ |

★ |

★★ |

☆ |

★ |

★ |

7 |

The NOS rating of a study must be converted to AHRQ standards by applying the above-mentioned thresholds after determining the number of stars the study obtained in each of the NOS areas (selection, comparability, and outcome/exposure). Based on these standards, the study's overall quality would be reflected in the ensuing categorization (Good, Fair, or Poor).

Using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) Risk of Bias tool, the assessment of risk of bias conducted by two reviewers across the included studies revealed varying levels of concern. Three of the studies were found to have some concerns regarding bias, while four were deemed to have a low risk of bias. This indicates a mixed quality of evidence within the reviewed literature, corroborated by the independent evaluations of both reviewers

3. Results

3.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

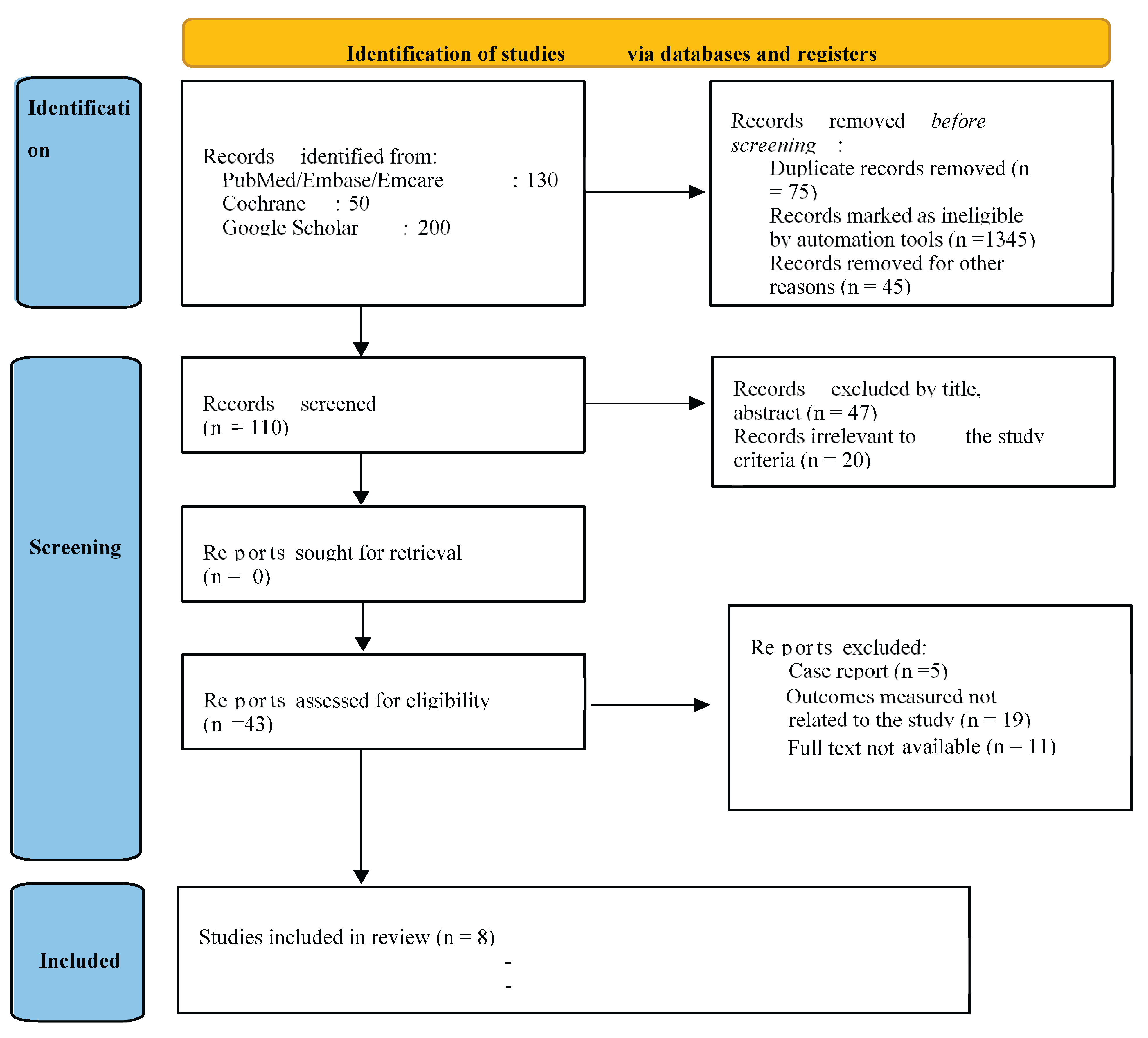

A total of 43 articles were identified from all databases. After assessing the titles and abstracts of these 43 papers, 13 were found ineligible. The full-text publications of the remaining 30 studies underwent individual eligibility reviews, resulting in the disqualification of 22 studies for not meeting inclusion criteria. Eventually, eight studies met the inclusion requirements and were primed for critical evaluation (

Figure 1). Initially, the original examiners' kappa score, indicating average agreement for quality evaluation, stood at 0.83. Following deliberation and consensus, the agreement reached a perfect score of 1.00.

Figure 1.

Prisma Flowchart.

Figure 1.

Prisma Flowchart.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the included studies and the outcome measured.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the included studies and the outcome measured.

| Author and year |

Mean age, Number of cases |

Location |

Histological feature |

Treatment |

Metastasis |

Follow up |

James Castle et al [21]

2000 |

57.8 years

164 |

Alveolar ridge 13

Buccal mucosa 16 |

Will circumscribed but not encapsulated with perineural invasion |

Surgical excision |

Pulmonary metastasis |

Dead with disease 3

Alive with disease 1

No disease 124 |

Adam Kimple et al[13]

2014 |

54 years

456 |

Palate 12

Retromolar

trigone 2

Gingiva 1

Nasal septum 1

maxillary sinus 2

nasal cavity 2

base of tongue 1 |

The non-encapsulated tumor seen invading the surrounding connective tissue. |

primary neutron beam therapy-one patient

primary radiation therapy-one patient

extensive local surgical excision-eighteen patients |

lung metastases |

Dead with disease 1

Alive with disease 4

13 no disease |

Hay. A et al [22]

2019 |

>60 years

450 |

oral cavity- 305 tumors

oropharynx- 96

sinonasal cavity

trachea 7

larynx with 4 |

The most frequent histological types in the oral cavity were mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, and PAC. |

All patients underwent surgical resection, with some also having a neck dissection. A portion of the patients were treated with surgery alone, while others received adjuvant radiation or adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. |

liver metastasis |

There were five late distant metastases from adenocarcinomas, one from polymorphous adenocarcinoma (PAC), five from mucoepidermoid carcinomas (MECs), and one from a mixed carcinoma. |

Ximena Mimica et al[23]

2019 |

61 years

884 patients |

Hard palate was the most common site (31) followed by the buccal mucosa(5) and

retromolar trigone and gum(2 each) |

papillary, tubular, solid with organoid apattern, and cribriform |

A mandibulectomy, transoral robotic surgery, craniofacial resection, extensive local excision, and partial maxillectomy were performed (34 patients, 17 patients, and 1 patient, respectively). Parotidectomy was performed on two patients and partial parotidectomy on one. Neck dissection was performed on 11 patients. |

lung metastases

bone metastases |

10-year recurrence-free survival -88% |

Vera Cavalcanti de Araujo et al [8] 2013 |

60-70 years

431 |

Palate |

Uniform single-cell strands characterize tumor histology.

With vesicular oval nuclei and inconspicuous nucleoli, the cells are tiny to medium in size and cytologically uniform in appearance. |

Not discussed |

Occasional metastases may appear years after the procedure. |

Favorable prognosis |

KR Chatura

[6] 2015 |

23 - 94 years

164 |

soft palate 17%

hard palate 16%

lip 13%

buccal mucosa 10%

alveolar ridge 8%

mucosal site 4% |

Lobular solid islands combined with a localized papillary cystic region, cribriform, and trabecular areas. ‘beads on a string’ amphophilic or eosinophilic cytoplasm

glasslike nuclei chromatin

washed out nuclei chromatin appearance |

conservative wide excision |

Cervical metastases- 15%

distant metastases- 7.5%

Death- 12.5% |

NA |

| Pogodzinski et al[24] 2006 |

61 years

19 |

Palate |

Characteristic small nucleoli, vesicular chromatin, a uniform oval nuclei, and cytoplasm that is moderately amphophilic to eosinophilic. |

wide local excision

no chemotherapy |

Lung metastasis (1)

Regional nodal disease (1) |

9.6 years

Local recurrence (5) |

| Çağatay Han Ülkü et al [25] 2017 |

66 years

600 |

hard palate 4 - buccal mucosa 5 |

solid membranous, tubular or trabecular |

parotidectomy and postoperative radiotherapy |

cervical lymph node - lungs - scalp - manubrium |

24 months with no disease recurrence and no complaints |

4. Discussion

Polymorphous Adenocarcinoma (PAC), an infrequent malignancy originating from the minor salivary glands, presents significant challenges in understanding its clinical features, treatment modalities, and survival rates.[

3] The varying incidences of PAC in different geographic regions emphasizes the condition's convoluted etiology. It demonstrates a complex interaction of genetic, environmental, and cultural factors in disease prevalence. [

26] It is crucial to comprehend the PAC epidemiology in depth and modify treatment protocols to accommodate for regional differences in disease incidence and presentation. [

8]

According to Castle et al., PAC usually affects people between the ages of sixty and seventy, and it is significantly more common in females in minor salivary glands.[

21] Development of customized management techniques is required due to regional differences in disease etiology and presentations.[

8] Clinically, PAC is characterized by painless swelling, although ulceration inside the tumor may be a sign of advanced disease stages and tissue invasion.[

21] Histological patterns of PAC, such as cribriform and solid patterns, have prognostic implications, with perineural invasion significantly influencing treatment decisions. [

18]

According to a study done by James Castle and others in the USA, the average age of the patients was found to be 57.8 years, and the male-to-female ratio was 55:108. Among the clinical characteristics noted were mass lesions in 143 cases, discomfort, ulceration, and bleeding in 13, and poorly fitting dentures in 7. The malignancies were found in the buccal mucosa (16 cases) and alveolar ridge (13 cases). The tumors were non-encapsulated and displayed perineural invasion, microscopically. Surgical excision was the main treatment. In certain cases, the disease had metastasized to the lungs. Three patients had died from the illness, one was still alive, and 124 were disease-free at the end of the follow-up period. [

21]

Adam Kimple et al. reported a slightly younger mean age of 54 years in the USA. This study highlighted swelling as the predominant symptom compared to Castle’s study. The sites reported were the palate (12), retromolar trigone (2), and other areas like the nasal cavity and base of the tongue. Surgery was the main mode of treatment with adjuvant radiation therapy. Kimple’s follow-up had 1 death with the disease, 4 alive with disease, and 13 without disease, showing a somewhat better outcome than Castle’s study.[

13,

21]

3 more studies in the USA provide further insights. Ashley J. Hay et al. observed a nearly equal male-to-female ratio (45:55) with edema as the prominent clinical feature. While Ximena Mimica and Matthew S et al. found swelling to be the primary clinical feature, with a mean age of 61 years. Mimica et al. and Matthew S et al. found the most common tumor location was the palate, but Hay et al.'s study is notable for its attention on a range of sites, including less common places like the trachea and larynx. All 3 studies used surgery as the main intervention, although Hay et al. included radiation as additional therapy. Different results are shown in the follow-up data; Mimica et al. showed good survival rates, while Hay et al. saw more distant metastases and recurrences. [

22,

23,

24]

Brazilian researchers Vera Cavalcanti de Araujo and associates presented the results of a study which involved patients with an age range of 60 to 70. Although some individuals experienced rare discomfort and ulceration, asymptomatic edema was the main clinical characteristic. The most common site was palate. The tumors were immunohistochemically positive and microscopically showed homogeneous single-cell strands. Although metastases were uncommon, they were observed to occur many years following surgical excision, which was employed as the chief treatment strategy. The study concluded that these tumors had a fair prognosis and were of low-grade malignancy.[

8]

An Indian study by KR Chatura included patients ranging in age from 23 to 94, with a 2:1 female to male ratio. A firm, painless submucosal tumor was the chief clinical characteristic. The most frequent locations for tumors were the hard palate, and soft palate; lip and other locations like the buccal mucosa, alveolar ridge, and mucosal regions. Histologically, the tumors showed papillary cystic regions, cribriform, trabecular, and lobular solid nests. The method used for treatment was conservative broad excision. It spread to distant locations and cervical lymph nodes. Some patients passed away from the illness, after several years.[

6]

In a research published by Çağatay Han Ülkü and associates from Turkey, the average patient age was 66 years. Clinical characteristics were cutaneous adnexal lesions and a non-tender tumor that was slowly growing. The hard palate and buccal mucosa were the main sites of tumors. Histologically, the tumors showed trabecular, tubular, and solid patterns. Postoperative irradiation was used a. The scalp, lungs, and cervical lymph nodes all showed signs of metastasis. In the 24-month period of observation, no recurrence of the condition was noted. [

25]

Histological subtleties such as cytologic and architectural features are crucial in differentiating these two tumors, for an accurate diagnosis and directing the right course of treatment. Small biopsy specimens were cited by Pogodzinski et al. as a contributing cause to diagnostic ambiguity, in distinguishing ACC from palatal pleomorphic adenoma and PAC. [

24] However, PAC's unique characteristics can be observed by a thorough histological analysis.[

6] Surgery is still the primary mode for treating PAC, and in cases with inadequate resection or perineural invasion, postoperative irradiation is used as an adjuvant therapy to improve prognosis and lower the chances of recurrence. Due to its high frequency, resistance to treatment, and invasive nature, PAC is still difficult to manage despite breakthroughs. [

22] Advances in imaging technologies and research into the molecular structure of PAC may help find the best treatments and enhance patient outcomes. [

24,

26]

The studies tend to display consistency in reporting the clinical and histological variability of PAC and the successful outcome of surgical excision as the main therapeutic approach. The intricacy of PAC is further highlighted by variations in study populations, methodology, and geographic locations, which also highlight the significance of customized approaches to patient care.

Limitations of the study

It is critical to recognize the shortcomings of current research, such as study heterogeneity and data quality problems. Differences in follow-up times, treatment results, and metastatic rates is the main limitation. The Newcastle and Ottawa scale (NOS) brought attention to drawbacks such as the time needed to evaluate treatment effects and failure to follow-up. Furthermore, some gaps in the evidence may go unfilled due to the limited number of researches.

5. Conclusion

Though its clinical presentation varies, painless swelling is a hallmark of PAC, which primarily affects palate. Histologically, PAC shows a variety of morphologies, such as solid, papillary, cystic, cribriform, fascicular, single file, and strand-like, which affects prognostic outcomes and treatment choices. In cases of incomplete resection, radiation therapy is frequently used as an adjuvant. Significantly, our data highlights the good prognosis linked to PAC, which is demonstrated by high survival rates and comparatively low rates of metastasis. However, with long term follow ups, distant metastasis or even transformation to a high-grade adenocarcinoma has been noted. Molecular characterisation is necessary due to challenges in accurate diagnosis and differentiation from other salivary gland neoplasms.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

MJ and PP supervised the study, conceptualized the idea and contributed equally in writing and editing the manuscript. AD, OM collected the resources, analyzed and interpreted the data in the screened scientific publications to fit the theme. MA, KA, AM, AS were major contributors in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Exclude this statement.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in request.

Acknowledgments

The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”Authors would like to thank Ajman University for supporting the APC of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| PAC |

Polymorphous Adenocarcinoa |

| NOS |

Newcastle and Ottawa scale |

References

- Lewandowska, A. M., Rudzki, M., Rudzki, S., Lewandowski, T., & Laskowska, B. (2019). Environmental risk factors for cancer - review paper. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine, 26(1), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Evans, H. L., & Batsakis, J. G. (1984). Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma of minor salivary glands. A study of 14 cases of a distinctive neoplasm. Cancer, 53(4), 935–942.

- Vincent, S. D., Hammond, H. L., & Finkelstein, M. W. (1994). Clinical and therapeutic features of polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, 77(1), 41–47.

- World Health Organization Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. (2024). Head and neck tumours. (5th ed.). Springer.

- Xu, B., Aneja, A., Ghossein, R., & Katabi, N. (2016). Predictors of outcome in the phenotypic spectrum of polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma (PAC) and cribriform adenocarcinoma of salivary gland (CASG): A retrospective study of 69 patients. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology, 40(11), 1526–1537. [CrossRef]

- Chatura, K. R. (2015). Polymorphous low grade adenocarcinoma. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, 19(1), 77–82.

- Rosa, A. C., Soares, A. B., Santos, F. P., Furuse, C., & de Araújo, V. C. (2016). Immunoexpression of growth factors and receptors in polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine, 45(7), 494–499. [CrossRef]

- de Araujo, V. C., Passador-Santos, F., Turssi, C., Soares, A. B., & de Araujo, N. S. (2013). Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma: An analysis of epidemiological studies and hints for pathologists. Diagnostic Pathology, 8, 6.

- Skalova, A., Michal, M., & Simpson, R. H. (2017). Newly described salivary gland tumors. Modern Pathology, 30(S1), S27–S43. [CrossRef]

- Atiq, A., Mushtaq, S., Hassan, U., Loya, A., Hussain, M., & Akhter, N. (2019). Utility of p63 and p40 in distinguishing polymorphous adenocarcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention, 20(10), 2917–2921. [CrossRef]

- Rooper, L., Sharma, R., & Bishop, J. A. (2015). Polymorphous low grade adenocarcinoma has a consistent p63+/p40- immunophenotype that helps distinguish it from adenoid cystic carcinoma and cellular pleomorphic adenoma. Head and Neck Pathology, 9, 79–84. [CrossRef]

- Patel, T. D., Vazquez, A., Park, R. C., & Eloy, J. A. (2015). Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma of the head and neck: A population-based study of 460 cases. The Laryngoscope, 125(7), 1644–1649.

- Kimple, A. J., Austin, G. K., Shah, R. N., Welch, C. M., Funkhouser, W. K., Zanation, A. M., & et al. (2014). Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma: A case series and determination of recurrence. The Laryngoscope, 124(12), 2714–2719.

- Seethala, R. R., Johnson, J. T., Barnes, E. L., & Myers, E. N. (2010). Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma: The University of Pittsburgh experience. Archives of Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery, 136(4), 385–392. [CrossRef]

- Simpson, R. H. W., Reis-Filho, J. S., Pereira, E. M., Ribeiro, A. C., & Abdulkadir, A. (2002). Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma of the salivary glands with transformation to high-grade carcinoma. Histopathology, 41(3), 250–259. [CrossRef]

- Surya, V., Tupkari, J. V., Joy, T., & Verma, P. (2015). Histopathological spectrum of polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, 19(2), 266. [CrossRef]

- Khosla, D., Madan, R., Goyal, S., Kumar, N., & Kapoor, R. (2022). Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma of the salivary glands - a review. Nigerian Medical Journal, 62(2), 49–53.

- Surya, V., Tupkari, J. V., Joy, T., & Verma, P. (2015). Histopathological spectrum of polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, 19(2), 266. [CrossRef]

- Evans, H. L., & Luna, M. A. (2000). Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma: A study of 40 cases with long-term follow up and an evaluation of the importance of papillary areas. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology, 24(10), 1319–1328. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L. D. R. (2004). Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma. Pathology Case Reviews, 9(6), 259–263. [CrossRef]

- Castle, J. T., Thompson, L. D., Frommelt, R. A., Wenig, B. M., & Kessler, H. P. (2000). Polymorphous low grade adenocarcinoma: A clinicopathologic study of 164 cases. Cancer, 86(2), 207–219.

- Hay, A. J., Migliacci, J., Karassawa Zanoni, D., McGill, M., Patel, S., & Ganly, I. (2019). Minor salivary gland tumors of the head and neck-Memorial Sloan Kettering experience: Incidence and outcomes by site and histological type. Cancer, 125(19), 3354–3366.

- Mimica, X., Katabi, N., McGill, M. R., Hay, A., Zanoni, D. K., Shah, J. P., Wong, R. J., Cohen, M. A., Patel, S. G., & Ganly, I. (2019). Polymorphous adenocarcinoma of salivary glands. Oral Oncology, 95, 52–58. [CrossRef]

- Pogodzinski, M. S., Sabri, A. N., Lewis, J. E., & Olsen, K. D. (2006). Retrospective study and review of polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma. The Laryngoscope, 116(12), 2145–2149. [CrossRef]

- Ülkü, Ç. H., Oltulu, P., & Avunduk, M. C. (2017). High-grade basal cell adenocarcinoma arising from the parotid gland: A case report and review of the literature. Turkish Archives of Otorhinolaryngology, 55(4), 187–190.

- Hernandez-Prera, J. C. (2019). Historical evolution of the polymorphous adenocarcinoma. Head and Neck Pathology, 13(3), 415–422. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).