Submitted:

24 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Liposome Preparation

2.2. Fluorescence Measurements

2.2.1. Curcumin-Liposomes Dissociation Constant

2.2.2. Curcumin’s Fluorescence Quenching by n-SASL

2.3. EPR Measurements

2.3.1. Continuous Wave (CW)

2.3.2. Saturation Recovery (SR)

3. Results

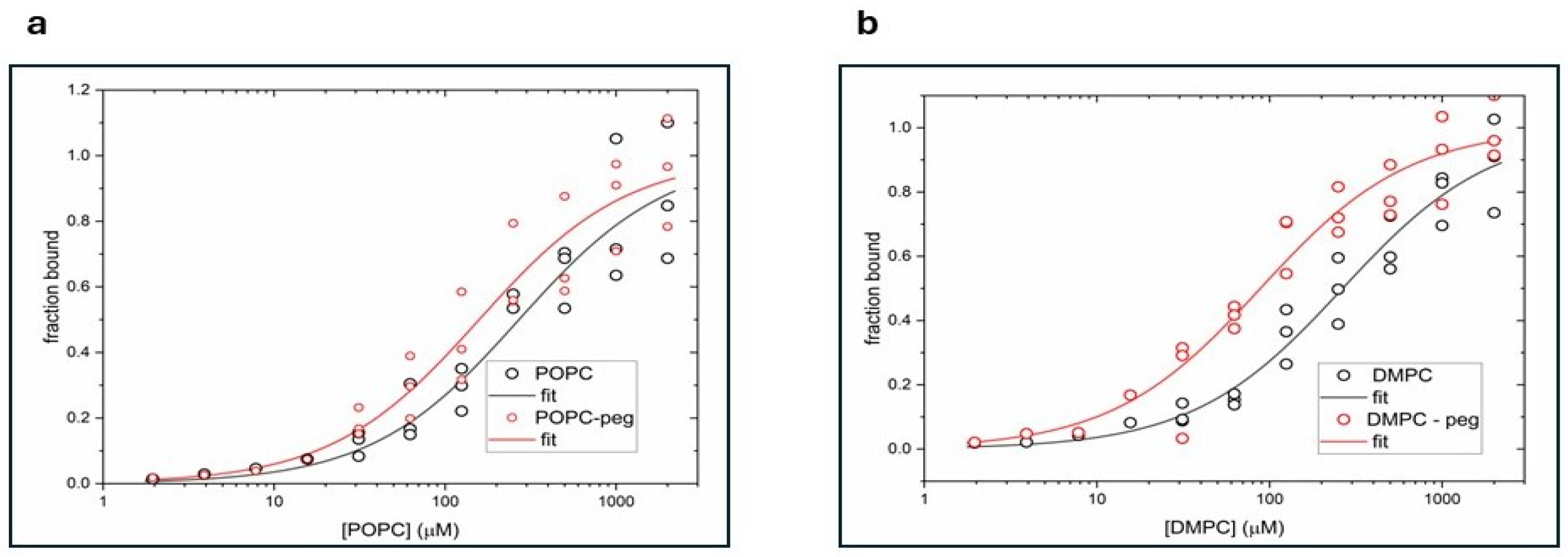

3.1. Effect of PEGylation on Curcumin Binding to DMPC and POPC Liposomes

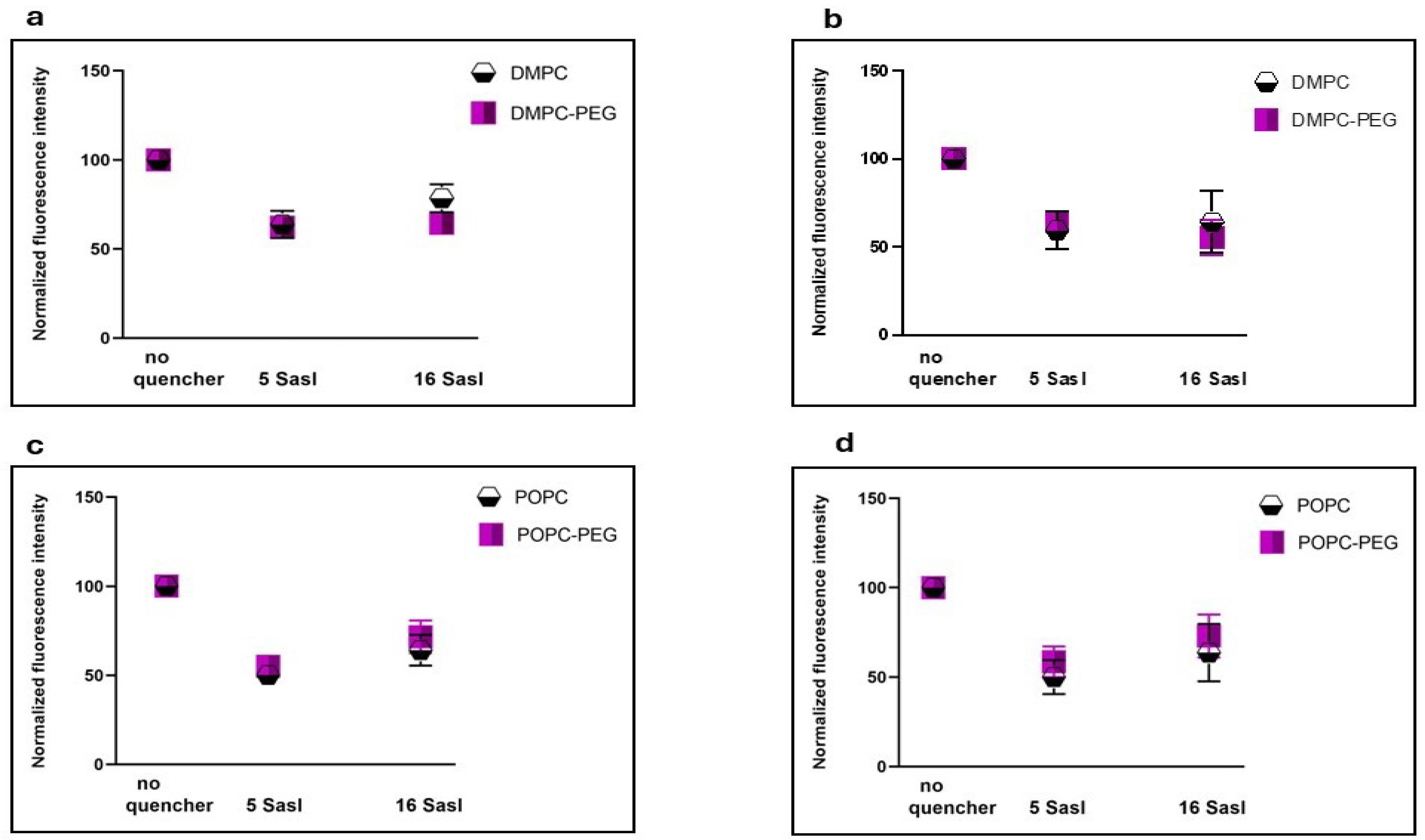

3.2. Quenching of Curcumin Fluorescence by Lipid Spin Labels

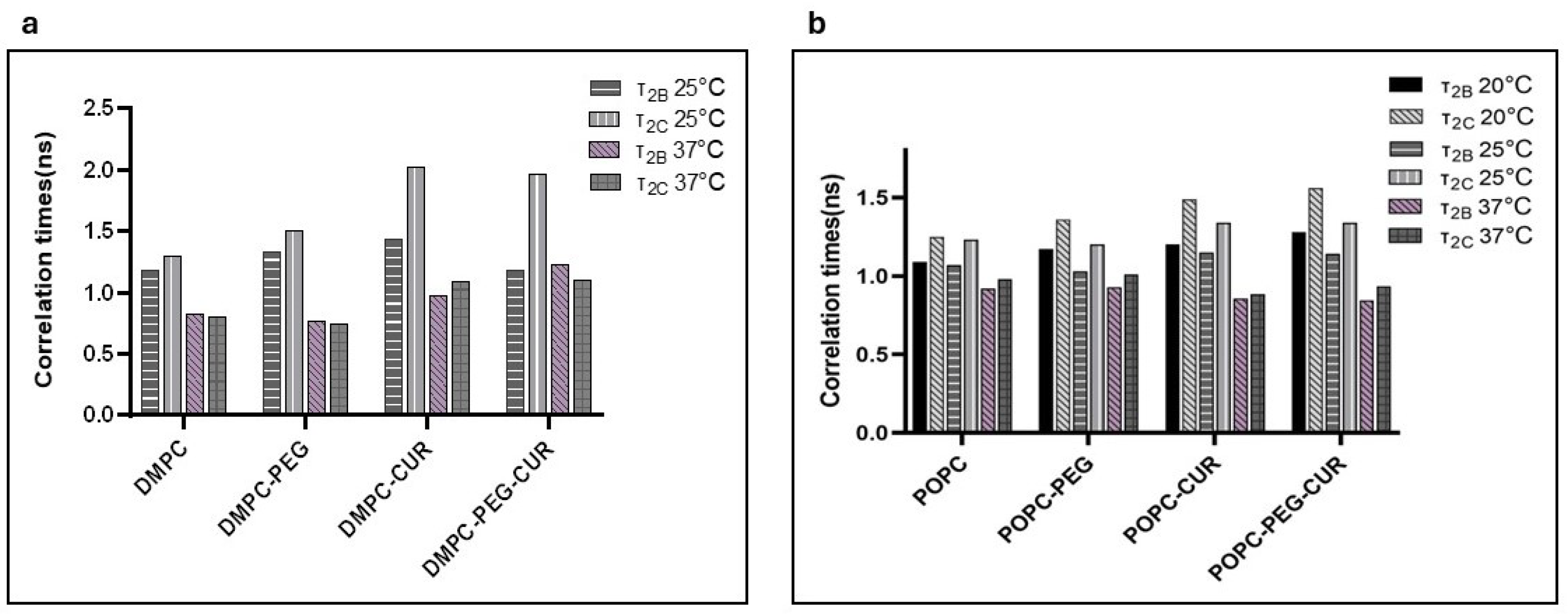

3.3. Effect of Curcumin on Lipid Mobility in PEGylated and Non-PEGylated Liposomes

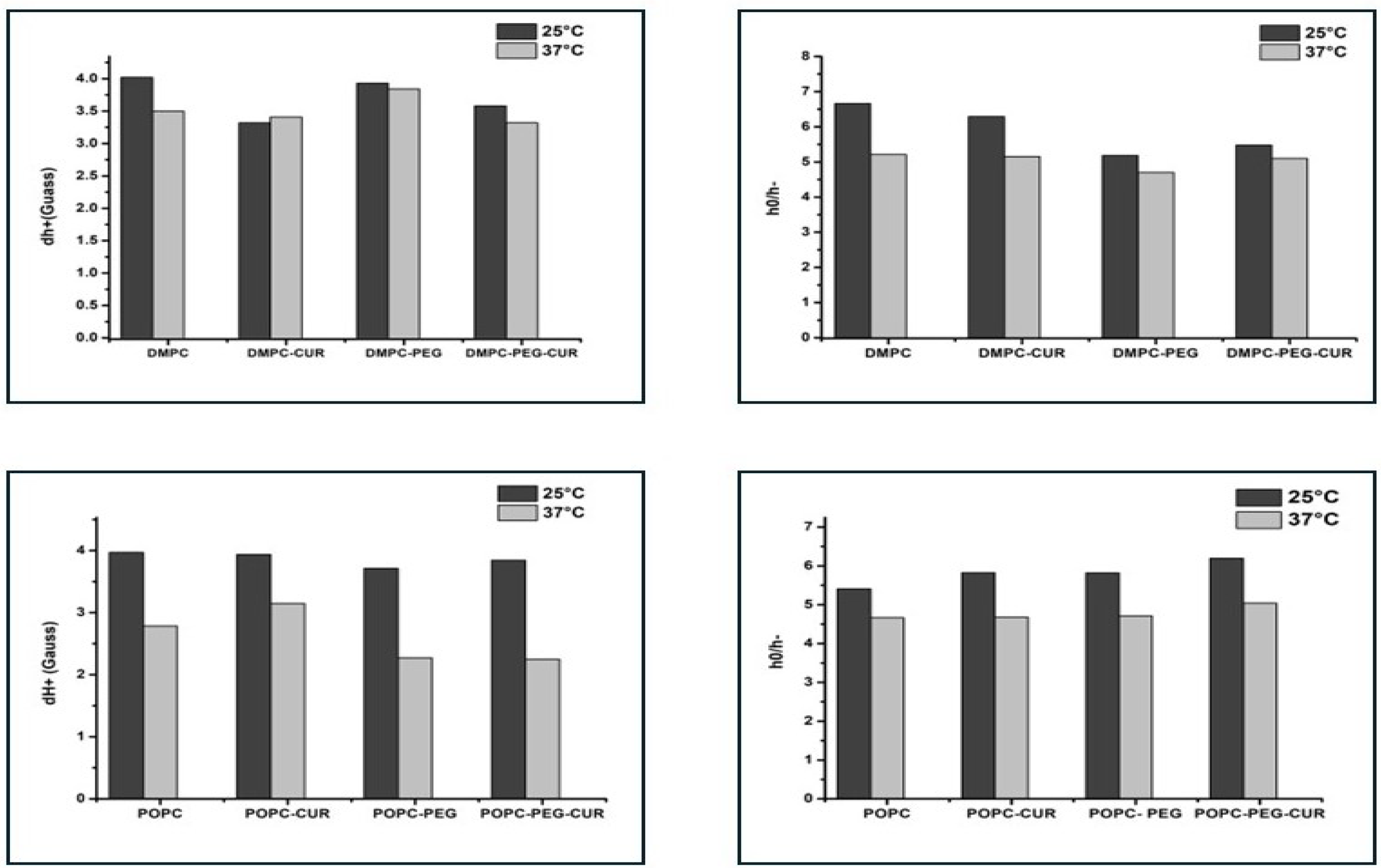

3.3.1. Polar Headgroup Region

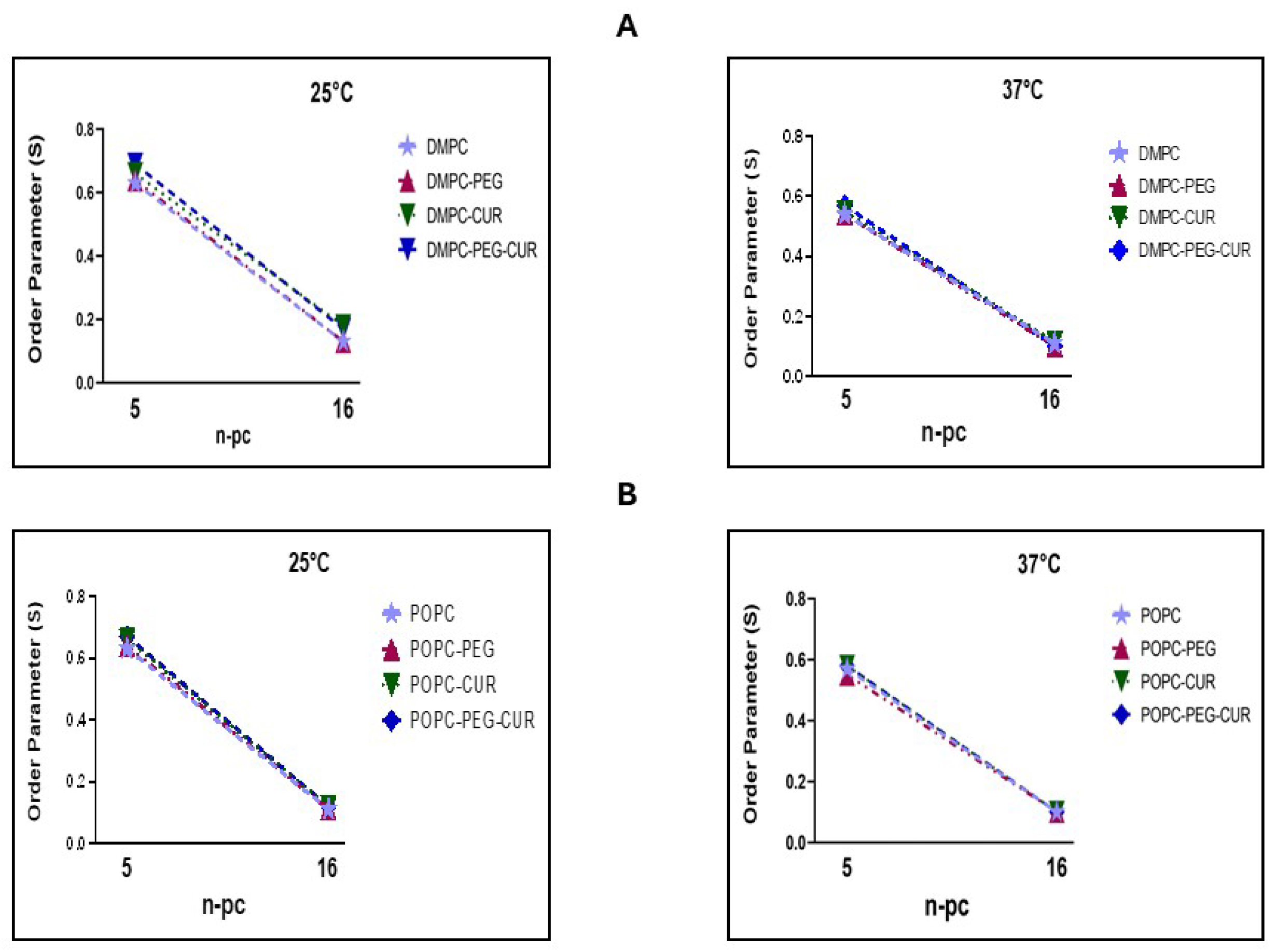

3.3.2. Alkyl Chain Region

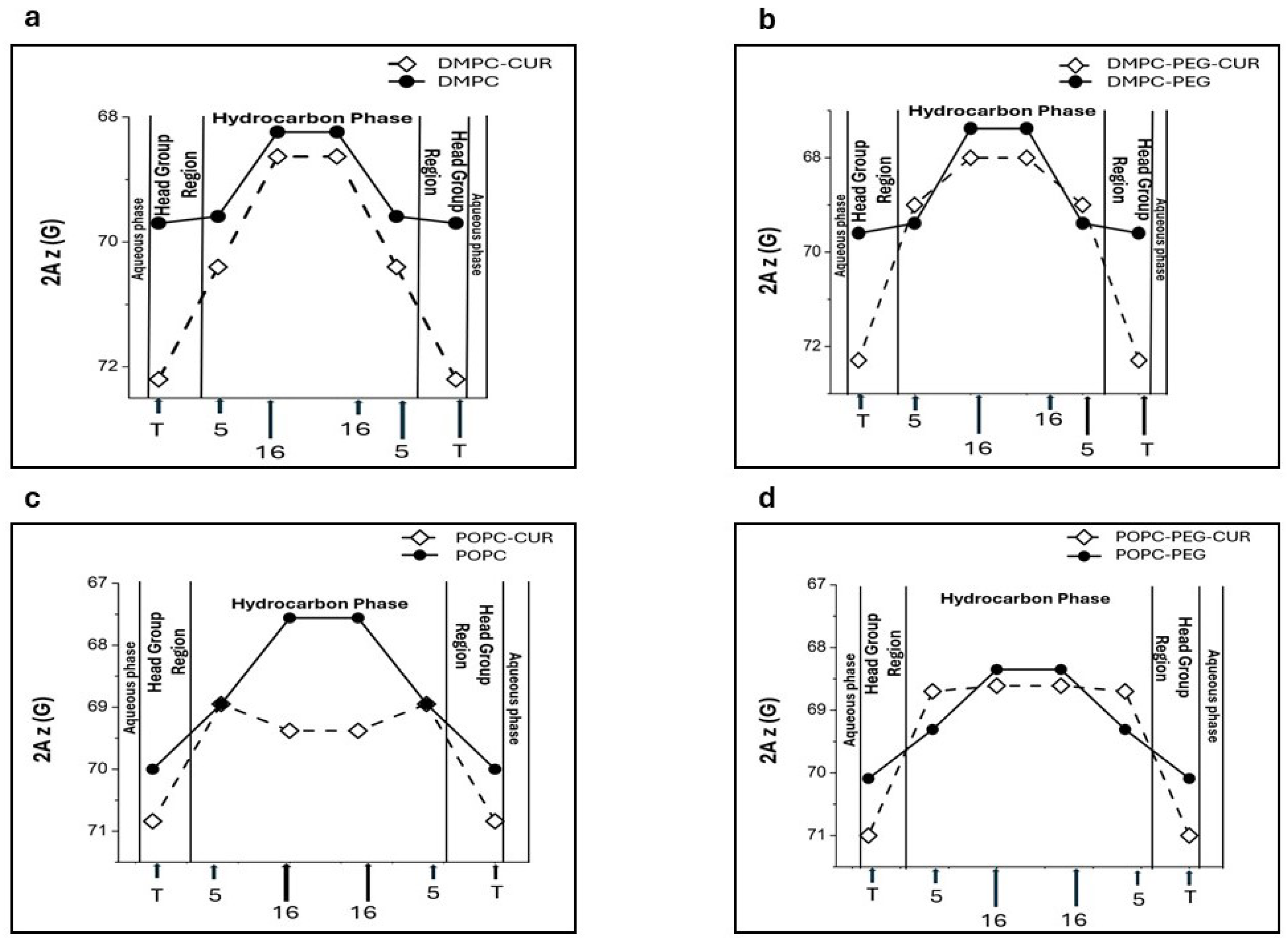

3.4. Effect of Curcumin on Polarity Profiles of PEGylated and Non-PEGylated Liposomes

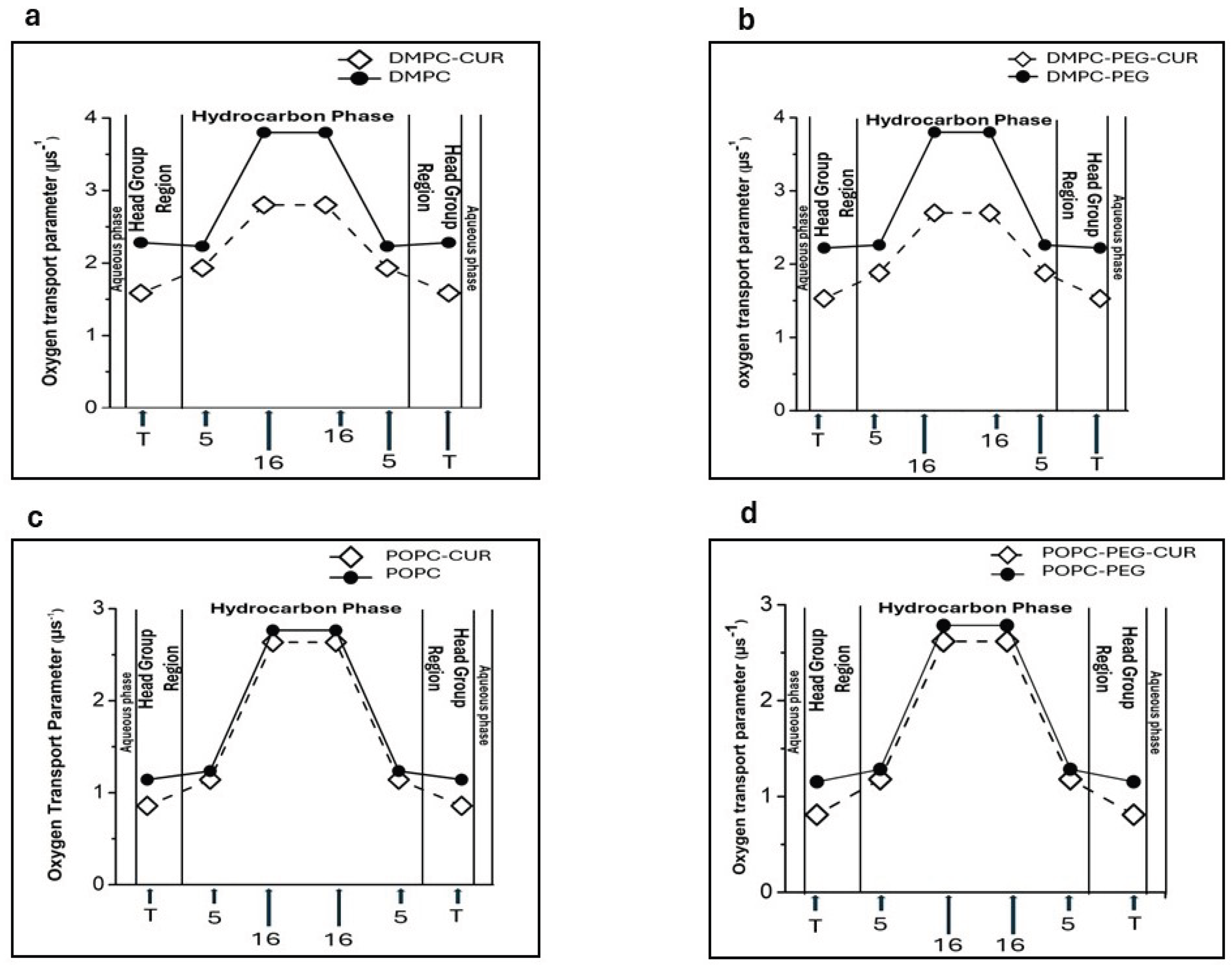

3.5. Effect of Curcumin on Oxygen Transport Parameter of PEGylated and Non-PEGylated Liposomes

4. Discussion

Fluorescence Experiments

EPR Experiments

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, G.; Zhou, X.; Pang, X.; Ma, K.; Li, L.; Song, Y.; Hou, D.; Wang, X. Pharmacological Effects, Molecular Mechanisms and Strategies to Improve Bioavailability of Curcumin in the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Pharmacol 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, P.; Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Newman, R.A.; Aggarwal, B.B. Bioavailability of Curcumin: Problems and Promises. Mol Pharm 2007, 4, 807–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duda, M.; Cygan, K.; Wisniewska-Becker, A. Effects of Curcumin on Lipid Membranes: An EPR Spin-Label Study. Cell Biochem Biophys 2020, 78, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Hu, S.; Sun, M.; Shi, J.; Zhang, H.; Yu, H.; Yang, Z. Recent Advances and Clinical Translation of Liposomal Delivery Systems in Cancer Therapy. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2024, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisani, S.; Di Martino, D.; Cerri, S.; Genta, I.; Dorati, R.; Bertino, G.; Benazzo, M.; Conti, B. Investigation and Comparison of Active and Passive Encapsulation Methods for Loading Proteins into Liposomes. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerasimov, O.V.; Boomer, J.A.; Qualls, M.M.; Thompson, D.H. Cytosolic Drug Delivery Using PH- and Light-Sensitive Liposomes. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 1999, 38, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.M.; Cullis, P.R. Liposomal Drug Delivery Systems: From Concept to Clinical Applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2013, 65, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.; Alaaeldin, E.; Hussein, A.; Sarhan, H.A. Liposomes and PEGylated Liposomes as Drug Delivery Systems, 2020.

- Liu, P.; Chen, G.; Zhang, J. A Review of Liposomes as a Drug Delivery System: Current Status of Approved Products, Regulatory Environments, and Future Perspectives. Molecules 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepczyński, M.; Nawalany, K.; Kumorek, M.; Kobierska, A.; Jachimska, B.; Nowakowska, M. Which Physical and Structural Factors of Liposome Carriers Control Their Drug-Loading Efficiency? Chem Phys Lipids 2008, 155, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Yamashita, K.; Itoh, Y.; Yoshino, K.; Nozawa, S.; Kasukawa, H. Comparative Studies of Polyethylene Glycol-Modified Liposomes Prepared Using Different PEG-Modification Methods. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2012, 1818, 2801–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzieciuch, M.; Rissanen, S.; Szydłowska, N.; Bunker, A.; Kumorek, M.; Jamróz, D.; Vattulainen, I.; Nowakowska, M.; Róg, T.; Kepczynski, M. Pegylated Liposomes as Carriers of Hydrophobic Porphyrins. Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2015, 119, 6646–6657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudyka, J.; Ceja-Vega, J.; Ivanchenko, K.; Morocho, Z.; Panella, M.; Gamez Hernandez, A.; Clarke, C.; Perez, E.; Silverberg, S.; Lee, S. Concentration-Dependent Effects of Curcumin on Membrane Permeability and Structure. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 2024, 7, 1546–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokkinis, S.; Paudel, K.R.; De Rubis, G.; Yeung, S.; Singh, M.; Singh, S.K.; Gupta, G.; Panth, N.; Oliver, B.; Dua, K. Liposomal Encapsulated Curcumin Attenuates Lung Cancer Proliferation, Migration, and Induces Apoptosis. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangemi, C.M.A.; Mirabile, S.; Monforte, M.; Barattucci, A.; Bonaccorsi, P.M. Bioimaging and Sensing Properties of Curcumin and Derivatives. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewska, A.; Subczynski, W.K. Effects of Polar Carotenoids on the Shape of the Hydrophobic Barrier of Phospholipid Bilayers; 1998; Vol. 1368.

- Kuzmič, P. Program DYNAFIT for the Analysis of Enzyme Kinetic Data: Application to HIV Proteinase. Anal Biochem 1996, 237, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilnicki, J., O.T., K.J., G.W., G.R.J., & F.W. SATURATION RECOVERY EPR SPECTROMETER. Molecular physics reports 1994.

- Froncisz W and James S Hyde The Loop-Gap Resonator: A New Microwave Lumped Circuit ESR Sample Structure. Journal of Magnetic Resonance 1982, 47, 515–521.

- Subczynski, W.K.; Wisniewska, A.; Hyde, J.S.; Kusumi, A. Three-Dimensional Dynamic Structure of the Liquid-Ordered Domain in Lipid Membranes as Examined by Pulse-EPR Oxygen Probing. Biophys J 2007, 92, 1573–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewska, A.; Widomska, J.; Subczynski, W.K. Carotenoid-Membrane Interactions in Liposomes: Effect of Dipolar, Mo-Nopolar, and Nonpolar Carotenoids *; 2006. Interactions in Liposomes.

- Kepczynski, M.; Kumorek, M.; Stepniewski, M.; Rog, T.; Kozik, B.; Jamroz, D.; Bednar, J.; Nowakowska, M. Behavior of 2,6-Bis(Decyloxy)Naphthalene inside Lipid Bilayer. J Phys Chem B 2010, 114, 15483–15494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepien, P.; Polit, A.; Wisniewska-Becker, A. Comparative EPR Studies on Lipid Bilayer Properties in Nanodiscs and Liposomes. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr 2015, 1848, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, D. Electron Spin Resonance: Spin Labels. 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Berliner, L.J. Spin Labeling in Enzymology: Spin-Labeled Enzymes and Proteins. Methods Enzymol 1978, 49, 418–480. [Google Scholar]

- Subczynski, W.K., W.A., Y.J.J., H.J.S., & K.A. Hydrophobic Barriers of Lipid Bilayer Membranes Formed by Reduction of Water Penetration by Alkyl Chain Unsaturation and Cholesterol?; 1994; Vol. 33.

- Yin, J.J.; Feix, J.B.; Hyde, J.S. Mapping of Collision Frequencies for Stearic Acid Spin Labels by Saturation-Recovery Electron Paramagnetic Resonance. Biophys J 1990, 58, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subczynski, W.K.; Hyde, J.S. The Diffusion-Concentration Product of Oxygen in Lipid Bilayers Using the Spin-Label Method. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1981, 643, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumi, A.; Subczynski, W.K.; Hydet, J.S. Oxygen Transport Parameter in Membranes as Deduced by Saturation Recovery Measurements of Spin-Lattice Relaxation Times of Spin Labels (Pulse ESR/Diffusion and Concentration of Oxygen/Phase Transitions); 1982; Vol. 79.

- Moghimi, S.M.; Szebeni, J. Stealth Liposomes and Long Circulating Nanoparticles: Critical Issues in Pharmacokinetics, Opsonization and Protein-Binding Properties. Prog Lipid Res 2003, 42, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Z.; Ye, H.; Kröger, M.; Li, Y. Aggregation of Polyethylene Glycol Polymers Suppresses Receptor-Mediated Endocytosis of PEGylated Liposomes. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 4545–4560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomatsu, I.; Marsden, H.R.; Rabe, M.; Versluis, F.; Zheng, T.; Zope, H.; Kros, A. Influence of Pegylation on Peptide-Mediated Liposome Fusion. J Mater Chem 2011, 21, 18927–18933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkle, H.; Subczynski, W.K.; Kusumi, A. Dynamic Fluorescence Quenching Studies on Lipid Mobilities in Phosphatidylcholine-Cholesterol Membranes. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1987, 897, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainali, L.; Hyde, J.S.; Subczynski, W.K. Using Spin-Label W-Band EPR to Study Membrane Fluidity Profiles in Samples of Small Volume. Journal of Magnetic Resonance 2013, 226, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subczynski, W.K.; Markowska, E.; Gruszecki, W.I.; Sielewiesiuk, J. Effects of Polar Carotenoids on Dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine Membranes: A Spin-Label Study. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1992, 1105, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subczynski, W.K.; Hyde, J.S.; Kusumi, A. Oxygen Permeability of Phosphatidylcholine-Cholesterol Membranes (Pulse ESR/Permeability Coefficient/Oxygen Transport); 1989; Vol. 86.

- Subczynski, W.K.; Markowska, E.; Gruszecki, W.I.; Sielewiesiuk, J. Effects of Polar Carotenoids on Dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine Membranes: A Spin-Label Study. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 1992, 1105, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaalem, M.; Hadrioui, N.; Derouiche, A.; Ridouane, H. Structure and Dynamics of Liposomes Designed for Drug Delivery: Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics Simulations to Reveal the Role of Lipopolymer Incorporation. RSC Adv 2020, 10, 3745–3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giakoumatos, E.C.; Gascoigne, L.; Gumí-Audenis, B.; García, Á.G.; Tuinier, R.; Voets, I.K. Impact of Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Functionalized Lipids on Ordering and Fluidity of Colloid Supported Lipid Bilayers. Soft Matter 2022, 18, 7569–7578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloi, E.; Bartucci, R. Cryogenically Frozen PEGylated Liposomes and Micelles: Water Penetration and Polarity Profiles. Biophys Chem 2020, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subczynski Witold, J.S.H. and A.K. Effect of Alkyl Chain Unsaturation and Cholesterol Intercalation on Oxygen Transport in Membranes: A Pulse ESR Spin Labeling Study?; 1991; Vol. 30.

| Samples | Kd* (μM) |

|---|---|

| POPC | 270 ± 89 |

| POPC-peg | 156 ± 46 |

| DMPC | 263 ± 58 |

| DMPC-peg | 88 ± 21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).