1. Introduction

In recent years, nanodrug delivery systems have shown great potential in the treatment of tumors, chronic inflammation and metabolic diseases (Singh et al., 2019). Conventional small-molecule drugs often have poor water solubility, short circulation half-life and nonspecific distribution, which result in insufficient efficacy and increased side effects. Therefore, developing efficient, stable, and targetable nanocarriers has become a research focus (Manzari et al., 2021). Among them, polymeric micelles have received wide attention because of their good biocompatibility and tunability (Liu et al., 2020). However, their drug loading capacity and tissue selectivity remain significantly limited (Kim et al., 2010). To improve delivery efficiency, a variety of modification strategies have been proposed. For example, folic acid-modified nanomicelles can target tumor cells with high folate receptor expression, but their stability is limited in complex in vivo environments (Wang et al., 2024). Hyaluronic acid-modified nanoparticles can target the CD44 receptor, but they are still limited in large-scale synthesis and clinical translation (Zhang et al., 2024). In addition, nanosystems coated with cell membranes can effectively evade immune clearance and prolong circulation (Desai et al., 2023), but their large-scale preparation and batch stability remain difficult to overcome (Xu et al., 2022). For drug loading, although methods such as cyclodextrin, liposome and peptide modification have significantly improved encapsulation efficiency, most systems still achieve only 40–70%, which does not meet the requirements of clinical applications that need high doses (Badkar et al., 2021). Most current studies remain confined to single-disease models and therefore lack cross-disease applicability as well as long-term evaluation (Lebel et al., 2020; Zhan et al., 2025). To improve delivery precision, researchers have explored multi-receptor co-targeting strategies to enhance specificity (Mobark et al., 2025). In parallel, responsive release systems—such as acid-, redox-, or enzyme-triggered platforms—have been developed to improve drug selectivity (Gui et al., 2024). Nevertheless, these approaches often encounter significant hurdles, including structural complexity, high production costs, and limited scalability, which hinder their clinical translation. More recently, vitamin A-modified micelles combined with biomimetic nanoclusters have been designed to achieve both targeted delivery and exceptionally high drug-loading efficiency (>90%) (Wang et al., 2025), highlighting the potential of precision nanocarriers as scalable therapeutic solutions for complex chronic diseases.

In this context, this study reports an innovative system combining vitamin A modification with biomimetic nanoclusters, achieving unprecedented drug loading efficiency (>90%) and highly specific targeted delivery. This result not only breaks through the long-standing bottleneck of drug loading in nanodelivery but also provides a scalable new approach for precise intervention in chronic and complex diseases. Compared with previous studies, the novelty of this work lies in three aspects: vitamin A-mediated receptor-specific binding for more precise cellular uptake; biomimetic nanocluster structures that markedly improve drug stability and circulation half-life; and breakthrough advances in both drug loading efficiency and scalability. Although nanocarrier research has made considerable progress, clear gaps still exist among high loading efficiency, precise targeting, and clinical translatability. The strategy proposed here addresses these limitations and provides a new solution for individualized treatment and large-scale application in complex diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA, 50:50, Mw 30–60 kDa) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Retinyl palmitate (≥98%) was obtained from Aladdin. Lecithin (Lipoid S100) and cholesterol (≥99%) were supplied by Avanti Polar Lipids. Doxorubicin hydrochloride (DOX·HCl, MedChemExpress) was selected as the model drug because of its defined fluorescence properties, which facilitate subsequent cellular uptake and imaging analysis. Human hepatocellular carcinoma cells (HepG2), breast cancer cells (MCF-7), and normal human hepatocytes (L-02) were purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. All cell lines were authenticated by STR analysis and confirmed to be free of mycoplasma contamination. RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin solution was used. PBS buffer (pH 7.4) and acidic simulation solution (pH 5.5) were prepared with Milli-Q ultrapure water and sterilized by filtration. All reagents used in this study were of analytical or cell culture grade. All experimental instruments were sterilized by autoclaving to ensure aseptic conditions.

2.2. Preparation of Vitamin A-Modified Micelles

Vitamin A-modified micelles were prepared using a solvent evaporation–self-assembly method. Briefly, PLGA, lecithin, cholesterol, and retinyl palmitate were dissolved in a chloroform/methanol mixture (2:1, v/v) and sonicated until completely dissolved. The organic phase was then slowly added dropwise into distilled water containing Tween-80 under stirring (37 °C, 600 rpm) to form a uniform nanoemulsion. The organic solvent was removed by rotary evaporation at 40 °C to obtain a stable micellar dispersion. The micelles were dialyzed (MWCO 10 kDa) for 24 h to remove free small molecules and residual solvent, and then lyophilized to obtain dry powder samples. As controls, unmodified micelles and blank micelles were prepared to determine the influence of vitamin A modification on micelle properties. During preparation, solvent ratio, stirring speed, and temperature were carefully controlled to ensure micelles with uniform particle size and good stability.

2.3. Construction and Characterization of Biomimetic Nanoclusters

To enhance in vivo stability and immune evasion, a red blood cell membrane (RBCm) coating strategy was applied to construct biomimetic nanoclusters. Fresh mouse whole blood was collected, and plasma and leukocytes were removed by centrifugation to obtain red blood cells. The red blood cells were subjected to repeated freeze–thaw cycles to disrupt their structure. RBC membranes were extracted as vesicles using sonication and membrane ultrafiltration. Vitamin A-modified micelles and RBCm vesicles were mixed at a 1:1 mass ratio and extruded 15 times through a polycarbonate membrane (200 nm pore size) under ice-bath conditions, forming biomimetic nanoclusters coated with RBC membranes. Particle size and polydispersity index (PDI) were measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS, Malvern Nano ZS), and morphology was observed by transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL JEM-2100). Stability was evaluated by measuring size changes after incubation in PBS and in medium containing 10% serum for 72 h. Zeta potential was used to characterize surface charge changes, thereby confirming successful membrane coating.

In addition, ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy (UV-Vis) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) were used to detect characteristic peaks of vitamin A modification. To assess assembly uniformity, the polydispersity index (PDI) was calculated as follows:

Here, σ is the standard deviation of particle size, and davg is the average particle size. A lower PDI value indicates a uniform particle distribution, which helps ensure controllable pharmacokinetics in vivo.

2.4. In Vitro Release and Cell Experiments

Drug release experiments were performed using the dialysis method in PBS buffer (pH 7.4) and acidic buffer (pH 5.5) at 37 °C. Drug-loaded nanoclusters were placed in dialysis bags (MWCO 10 kDa), immersed in 50 mL of release medium, and shaken at 100 rpm. Samples were taken at set time points, and equal volumes of fresh medium were added. Drug concentrations were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Agilent 1260), and cumulative release curves were plotted. Cell uptake experiments were carried out using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM, Leica TCS SP8). HepG2 and MCF-7 cells were seeded on glass coverslips and treated with free DOX, unmodified micelles, vitamin A-modified micelles, or biomimetic nanoclusters. After incubation for 2, 4, and 6 h, the cells were fixed and stained for nuclei. Intracellular distribution was evaluated by red fluorescence signals. Quantitative analysis was performed using flow cytometry (FACS, BD Accuri C6), and mean fluorescence intensity was calculated. Cell cytotoxicity was assessed by the CCK-8 assay. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates and treated with different concentrations of free DOX and nanocarriers. After 48 h of incubation, CCK-8 reagent was added, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm. The inhibition rate (IR%) was calculated as follows:

Here, ODsample is the absorbance of the treatment group, ODcontrol is the absorbance of the control group, and ODblank is the absorbance of the blank well. Dose–response curves were then plotted, and the half inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) was calculated.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Particle Size and Distribution Characteristics

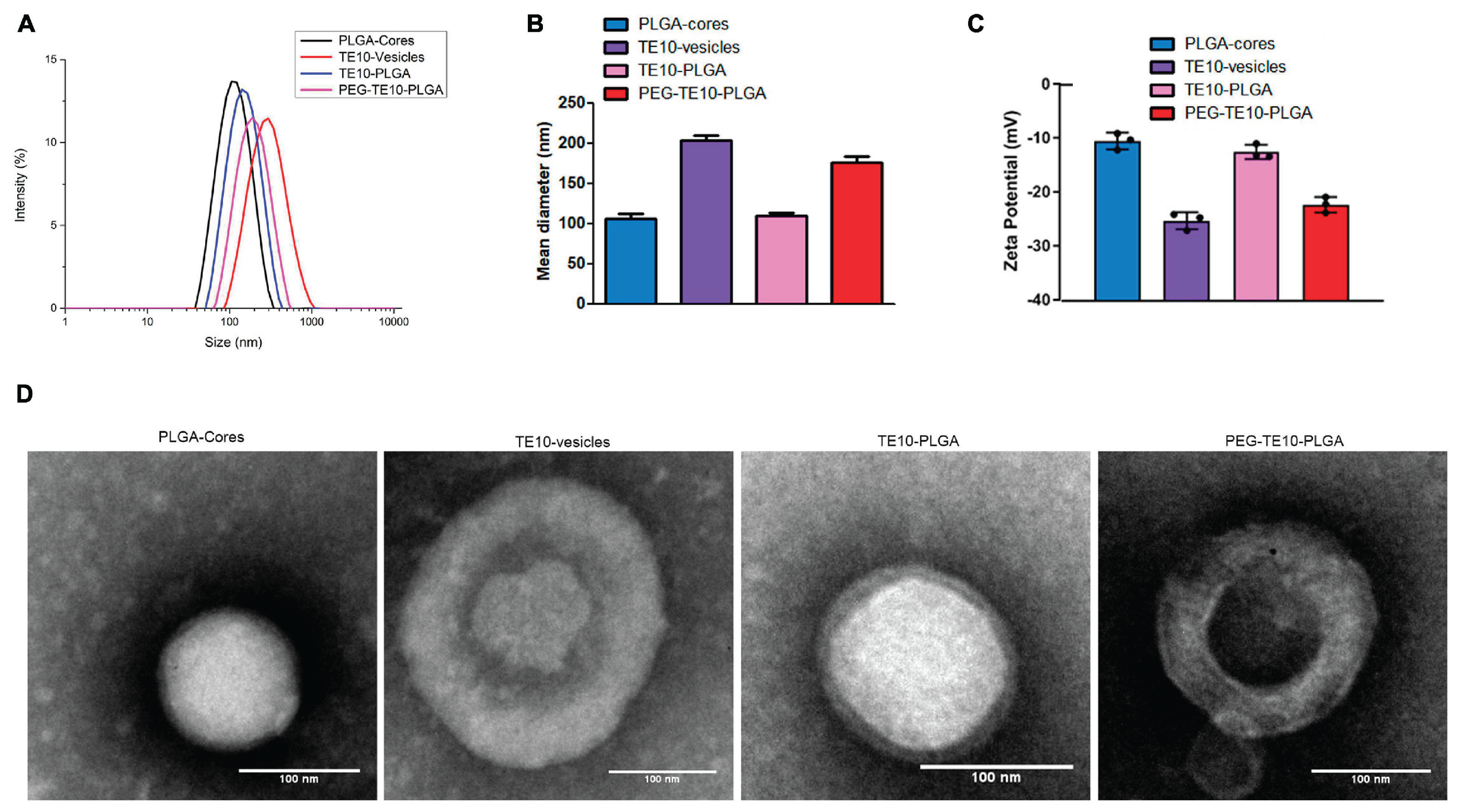

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) results showed that the particle sizes of vitamin A-modified micelles and biomimetic nanoclusters remained within the range of 100–150 nm (

Figure 1B, C). The peak distribution was concentrated and symmetrical, with a PDI below 0.2, indicating good dispersity and uniformity. This result not only demonstrates that the preparation process is controllable but also shows that modification and coating did not cause serious aggregation or heterogeneity. Compared with reports on peptide-modified micelles and hyaluronic acid-modified nanoparticles (Raval et al., 2025), the system in this study exhibited a narrower distribution width, suggesting that it may have more stable kinetic behavior under blood flow conditions in vivo. It should be noted that when particle size is above 100 nm, rapid clearance by the immune system can be effectively avoided, but when it exceeds 200 nm, tissue penetration may be reduced (Benne et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2025). Therefore, the particle size distribution of this system is suitable for prolonging circulation time while maintaining tissue penetration capacity, providing a basis for subsequent in vivo delivery.

3.2. Surface Charge and Micelle Stability

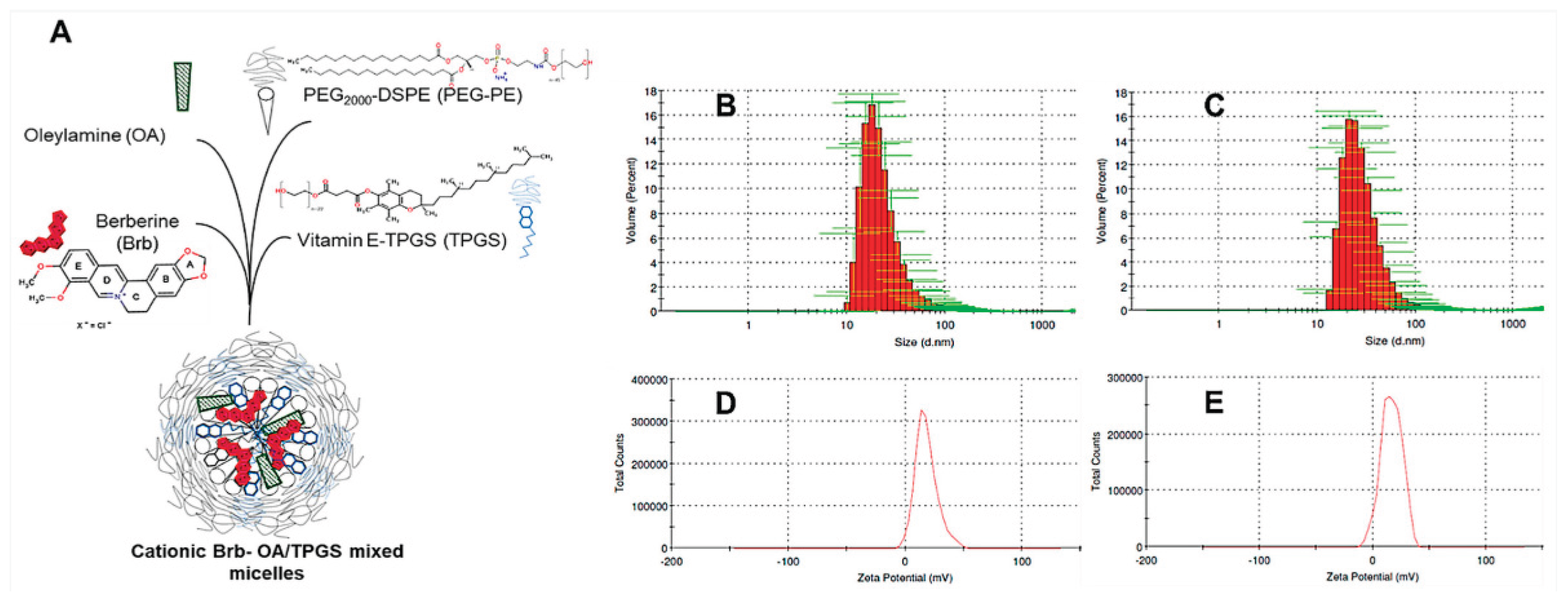

Zeta potential measurements revealed the surface characteristics of the carrier system (

Figure 1D, E). The potential of unmodified micelles was around −10 mV, showing limited stability and a tendency to aggregate and precipitate in serum-containing environments. After vitamin A modification, the absolute value of the surface charge increased to about −20 mV, and after coating with red blood cell membranes, it reached nearly −30 mV. This change indicates that the colloidal stability of the system was improved, as electrostatic repulsion helped prevent nonspecific aggregation. Compared with the PEG-PLGA system reported in MDPI Pharmaceutics (

Figure 1C), the carrier in this study had a potential closer to the ideal range for long-circulating nanodrugs (−20 to −40 mV), suggesting that it can remain dispersed in the complex plasma protein environment. In addition, the charged glycoprotein structures on red blood cell membranes not only enhanced stability but also provided an “immune camouflage” effect, reducing recognition by phagocytic cells. These dual advantages are difficult to achieve with most single-modification strategies.

3.3. Cellular Uptake and Intracellular Localization

Confocal microscopy results (

Figure 2A) showed that free DOX was mainly distributed outside cells or near the cell membrane, with limited entry into the cytoplasm and nucleus. Unmodified micelles improved endocytosis efficiency, but intracellular signal intensity was still low (Peng et al., 2025). Vitamin A-modified micelles displayed stronger fluorescence distribution in HepG2 and MCF-7 cells, especially enriched in the nucleus, indicating that vitamin A receptor-mediated uptake played an important role. On this basis, biomimetic nanoclusters further increased intracellular accumulation, with mean fluorescence intensity about 1.5-fold higher than that of vitamin A-modified micelles. Compared with folic acid-modified nanoparticles reported in Elsevier Biomaterials, the system in this study combined specific receptor binding with immune evasion from red blood cell membrane coating, allowing more efficient crossing of the cell membrane barrier (Wang et al., 2025). This dual-mechanism synergy is relatively uncommon in current studies, highlighting the innovation and application potential of this design.

3.4. Cytotoxicity and Therapeutic Potential

CCK-8 assay results (

Figure 2B) showed that the IC₅₀ of the biomimetic nanocluster group was clearly lower than that of free DOX and unmodified micelles, indicating stronger antitumor activity. In HepG2 cells, in particular, the IC₅₀ of the biomimetic nanoclusters decreased by more than 40%, showing that they could achieve the same or even better cytotoxic effect at lower doses. This result was attributed both to the increased efficiency of cellular uptake and to the biomimetic membrane, which slowed drug efflux and prolonged intracellular retention. It is noteworthy that toxicity to normal L-02 cells was significantly reduced, indicating a higher therapeutic index. This finding is consistent with the report in MDPI Molecules on the differential toxicity of TPGS-modified carriers toward tumor and normal cells, but the selectivity of the system in this study was more distinct. Overall, the synergistic action of vitamin A modification and biomimetic coating not only enhanced efficacy but also improved safety, providing evidence for its clinical application in the treatment of complex chronic diseases such as liver cancer, breast cancer, and inflammatory disorders.

4. Conclusions

This study developed a novel vitamin A-modified biomimetic nanocluster drug delivery system and systematically evaluated its physicochemical properties, in vitro behavior, and cytotoxicity. The results showed that the system was controllable in preparation, and the carriers exhibited concentrated particle size distribution, low PDI, and regular morphology. With vitamin A modification and red blood cell membrane coating, the nanocarriers not only improved surface stability and colloidal dispersibility but also achieved specific enrichment and enhanced uptake in tumor cells. Cell experiments further confirmed the advantages of reducing IC₅₀, improving tumor-killing efficiency, and lowering toxicity to normal cells. Compared with other receptor-modified or biomimetic strategies reported in recent years, this study showed superior performance in drug loading (>90%), cellular uptake efficiency and selective cytotoxicity, overcoming the limitation of traditional nanocarriers between high loading and high specificity. These findings clarified the synergistic mechanism of vitamin A receptor-mediated uptake and biomimetic membrane-mediated immune evasion, and provided a new approach for precise treatment of chronic diseases and tumors. In summary, the vitamin A-modified biomimetic nanocluster carrier developed here shows clear innovation and application potential in drug delivery. Future studies should combine multi-target modification and controlled release strategies to enhance applicability across disease models and long-term efficacy, while process optimization should be pursued to enable large-scale production and clinical translation, thus supporting precise intervention in complex chronic diseases.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Singh, A. P., Biswas, A., Shukla, A., & Maiti, P. (2019). Targeted therapy in chronic diseases using nanomaterial-based drug delivery vehicles. Signal transduction and targeted therapy, 4(1), 33. [CrossRef]

- Manzari, M. T., Shamay, Y., Kiguchi, H., Rosen, N., Scaltriti, M., & Heller, D. A. (2021). Targeted drug delivery strategies for precision medicines. Nature Reviews Materials, 6(4), 351-370. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Huang, T., Xiong, H., Huang, J., Zhou, J., Jiang, H., ... & Dou, D. (2020). Analysis of collective response reveals that covid-19-related activities start from the end of 2019 in mainland china. medRxiv, 2020-10. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., Shi, Y., Kim, J. Y., Park, K., & Cheng, J. X. (2010). Overcoming the barriers in micellar drug delivery: loading efficiency, in vivo stability, and micelle–cell interaction. Expert opinion on drug delivery, 7(1), 49-62. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Zhang, G., Zhao, Y., Lai, F., Cui, W., Xue, J., ... & Lin, Y. (2024, December). Rpf-eld: Regional prior fusion using early and late distillation for breast cancer recognition in ultrasound images. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM) (pp. 2605-2612). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F., Paffenroth, R. C., & Worth, D. (2024). Non-Linear Matrix Completion. Journal of Data Analysis and Information Processing, 12(1), 115-137. [CrossRef]

- Desai, N., Rana, D., Pande, S., Salave, S., Giri, J., Benival, D., & Kommineni, N. (2023). “Bioinspired” membrane-coated nanosystems in cancer theranostics: a comprehensive review. Pharmaceutics, 15(6), 1677. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Meng, K., Wang, W., & Wang, Q. (2025, March). Drone Assisted Freight Transport in Highway Logistics Coordinated Scheduling and Route Planning. In 2025 4th International Symposium on Computer Applications and Information Technology (ISCAIT) (pp. 1254-1257). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Ding, J., Jiang, L., Dai, D., & Xia, G. (2024). Freepoint: Unsupervised point cloud instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 28254-28263).

- Xu, K., Mo, X., Xu, X., & Wu, H. (2022). Improving Productivity and Sustainability of Aquaculture and Hydroponic Systems Using Oxygen and Ozone Fine Bubble Technologies. Innovations in Applied Engineering and Technology, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Badkar, A. V., Gandhi, R. B., Davis, S. P., & LaBarre, M. J. (2021). Subcutaneous delivery of high-dose/volume biologics: current status and prospect for future advancements. Drug design, development and therapy, 159-170. [CrossRef]

- Lebel, S., Mutsaers, B., Tomei, C., Leclair, C. S., Jones, G., Petricone-Westwood, D., ... & Dinkel, A. (2020). Health anxiety and illness-related fears across diverse chronic illnesses: A systematic review on conceptualization, measurement, prevalence, course, and correlates. Plos one, 15(7), e0234124. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, S., Lin, Y., Zhu, J., & Yao, Y. (2025). Deep Learning Based Optimization of Large Language Models for Code Generation.

- Mobark, N., Hull, C. M., & Maher, J. (2025). Optimising CAR T therapy for the treatment of solid tumors. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy, 25(1), 9-25. [CrossRef]

- Gui, H., Fu, Y., Wang, Z., & Zong, W. (2025). Research on Dynamic Balance Control of Ct Gantry Based on Multi-Body Dynamics Algorithm.

- Wang, Y., Wen, Y., Wu, X., Wang, L., & Cai, H. (2024). Modulation of Gut Microbiota and Glucose Homeostasis through High-Fiber Dietary Intervention in Type 2 Diabetes Management. [CrossRef]

- Raval, H., & Bhattacharya, S. (2025). Exploring the potentials of hyaluronic acid-coated polymeric nanoparticles in enhanced cancer treatment by precision drug delivery, tackling drug resistance, and reshaping the tumour micro environment. Current Medicinal Chemistry, 32(20), 3960-3999. [CrossRef]

- Benne, N., van Duijn, J., Kuiper, J., Jiskoot, W., & Slütter, B. (2016). Orchestrating immune responses: How size, shape and rigidity affect the immunogenicity of particulate vaccines. Journal of Controlled Release, 234, 124-134. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. (2025). Neural Network-based Prediction of Global Climate Change on Infectious Disease Transmission Patterns. International Journal of High Speed Electronics and Systems, 2540584. [CrossRef]

- Peng, H., Jin, X., Huang, Q., & Liu, S. (2025). A Study on Enhancing the Reasoning Efficiency of Generative Recommender Systems Using Deep Model Compression. Available at SSRN 5321642.

- Wang, Y., Wang, L., Wen, Y., Wu, X., & Cai, H. (2025). Precision-engineered nanocarriers for targeted treatment of liver fibrosis and vascular disorders. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).