Submitted:

23 November 2025

Posted:

26 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental and Theoretical Approaches

2.1. Experimental Preparation and Characterization of g-C3N4 and P@g-C3N4

2.2. Structural Models and Computational Details

3. Results and Discussion

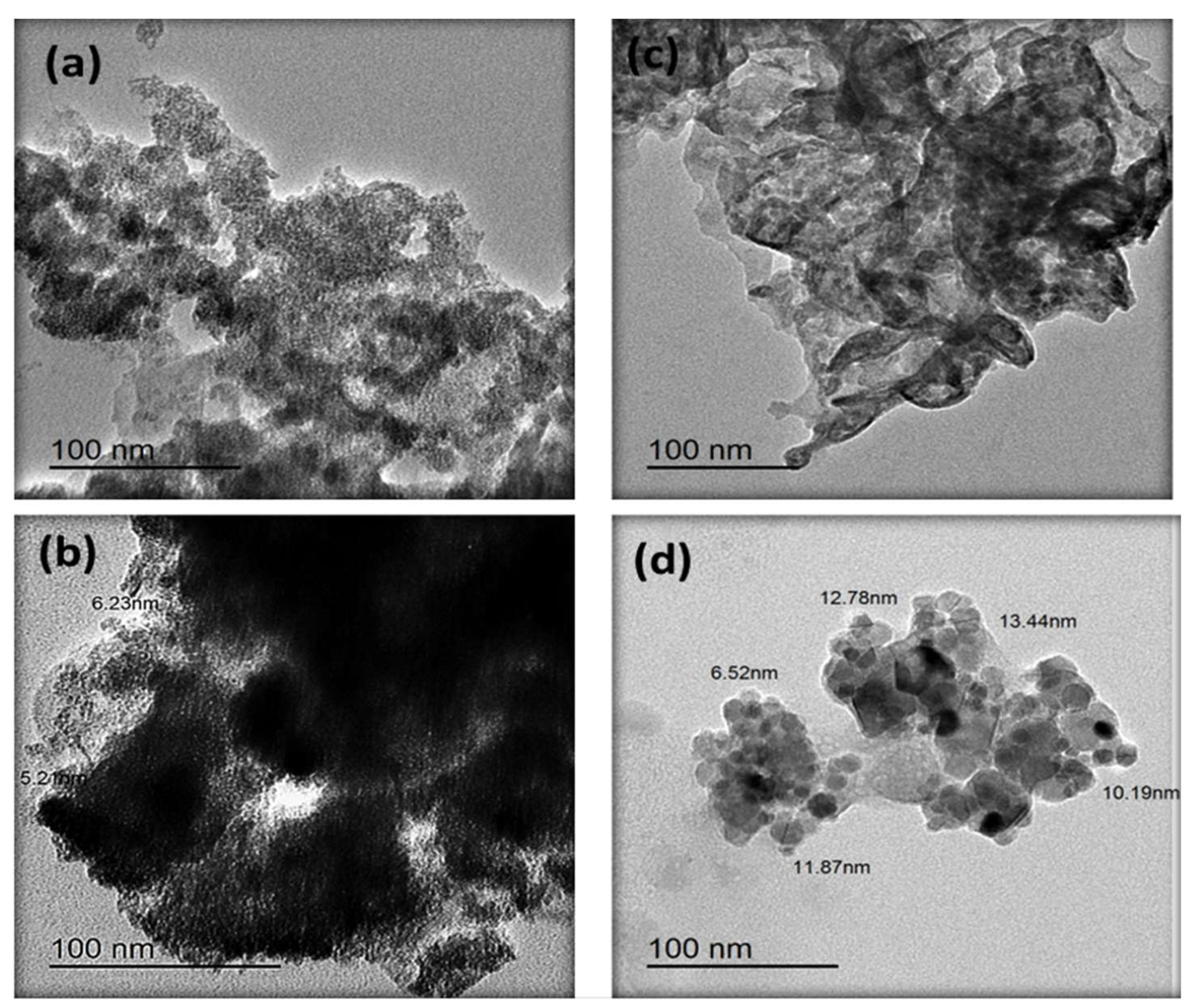

3.1. Transmission Electron Microscopy of g-C3N4 and P@g-C3N4

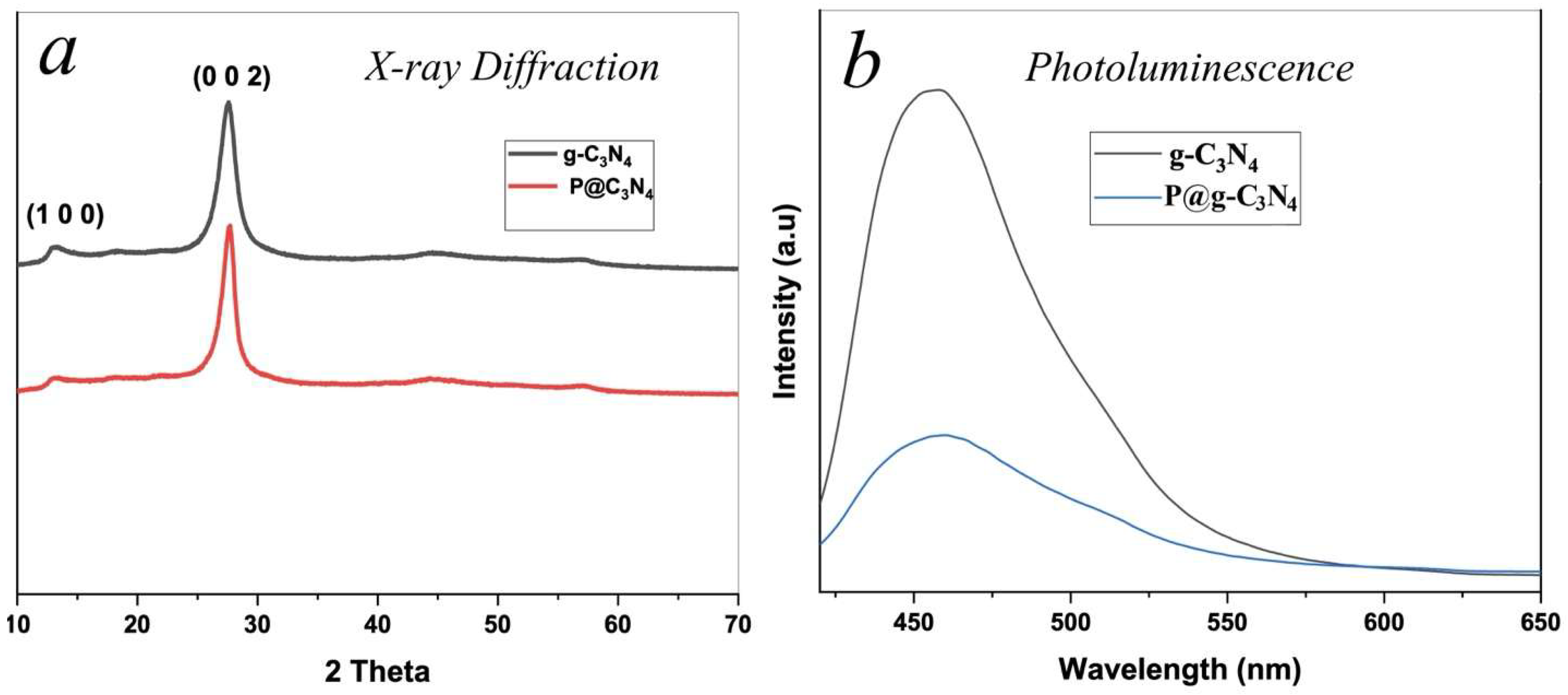

3.2. X Ray Diffraction of g-C3N4 and P@g-C3N4

3.3. Fluorescence Spectra of g-C3N4 and P@g-C3N4

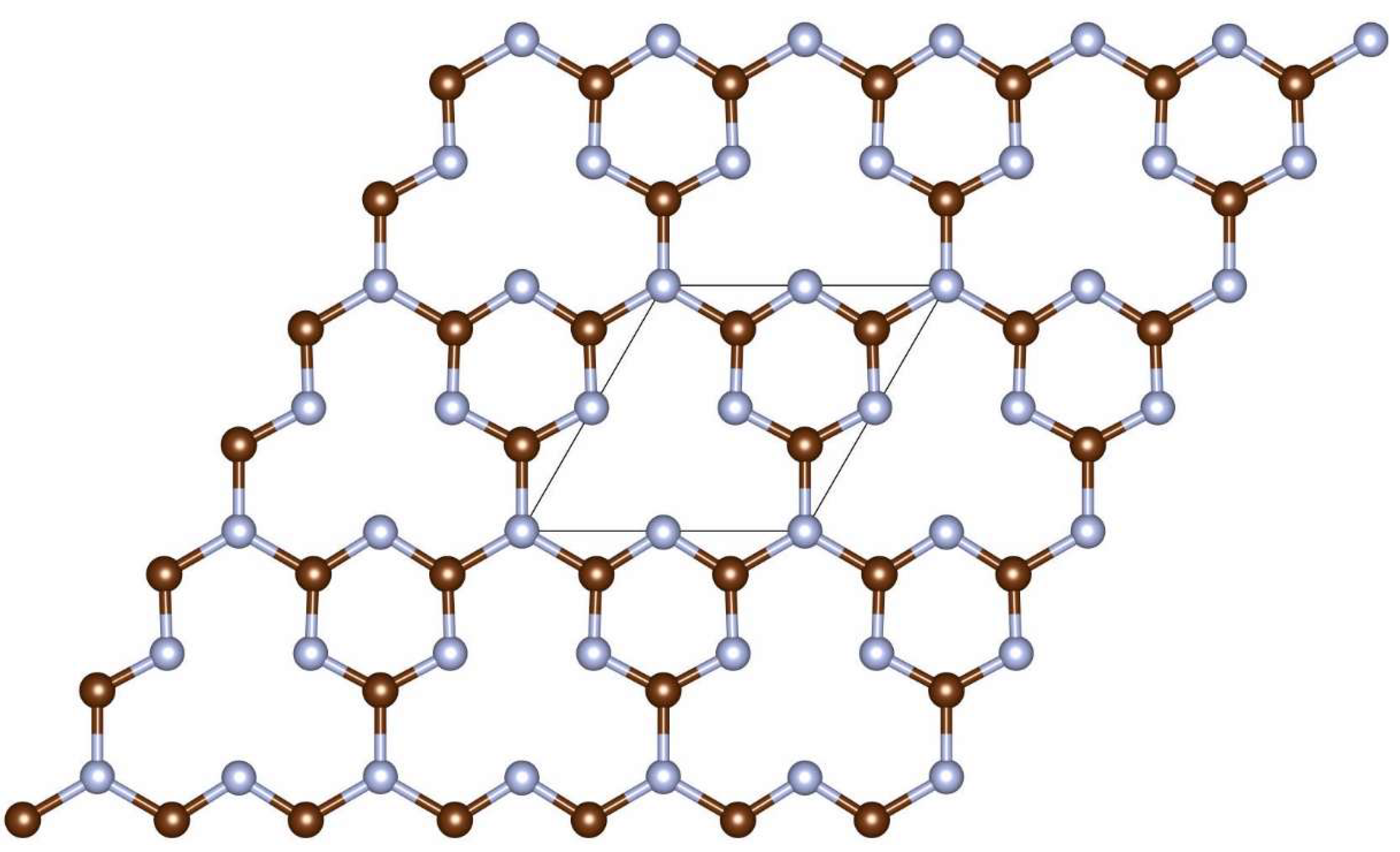

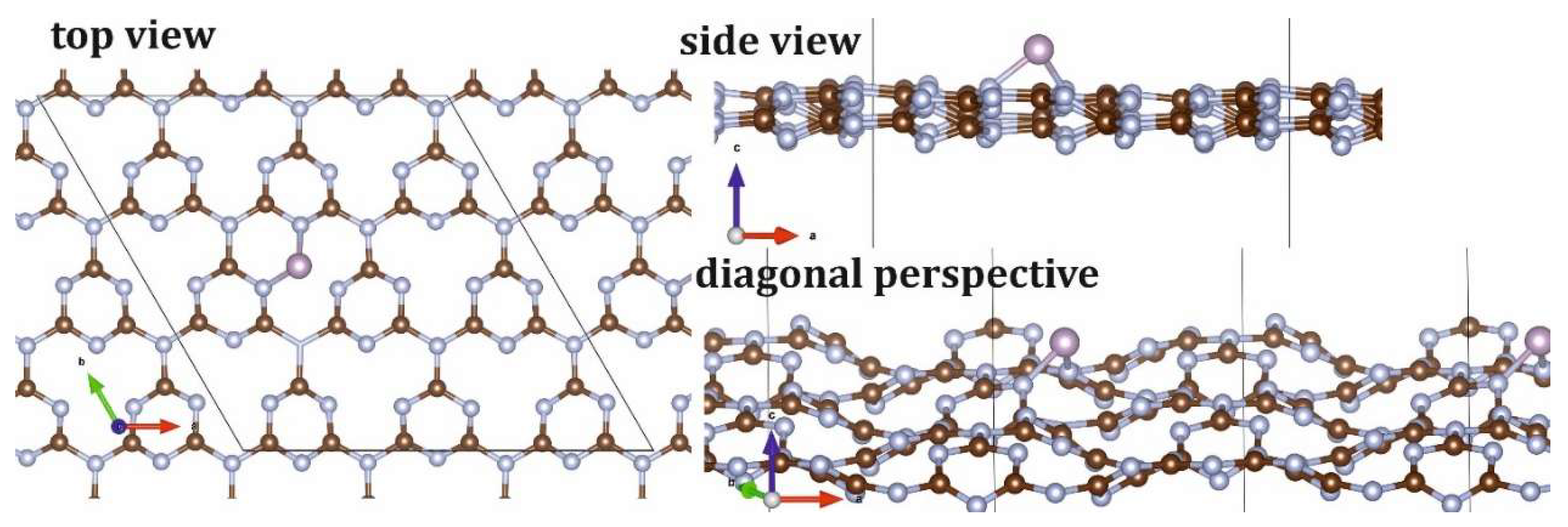

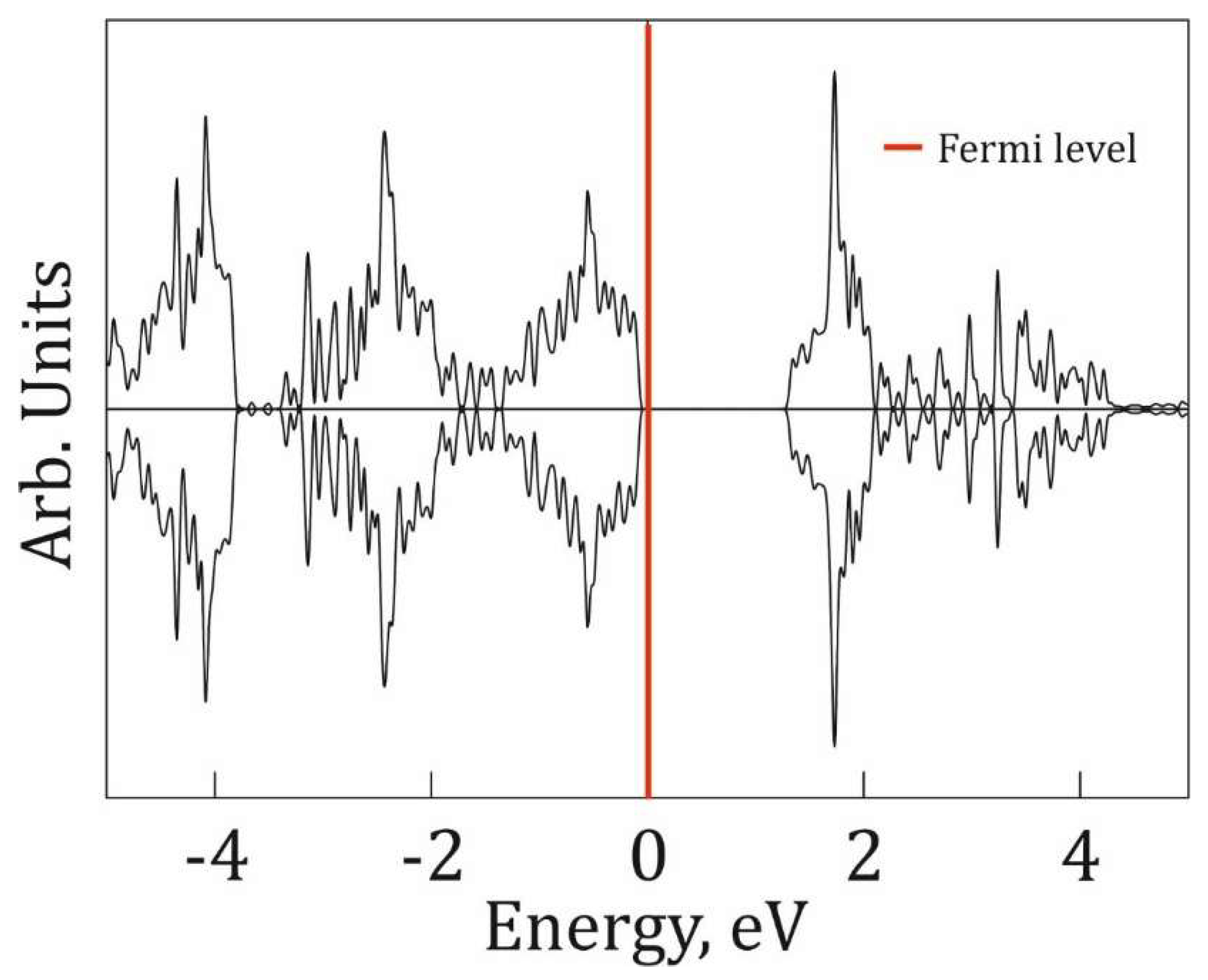

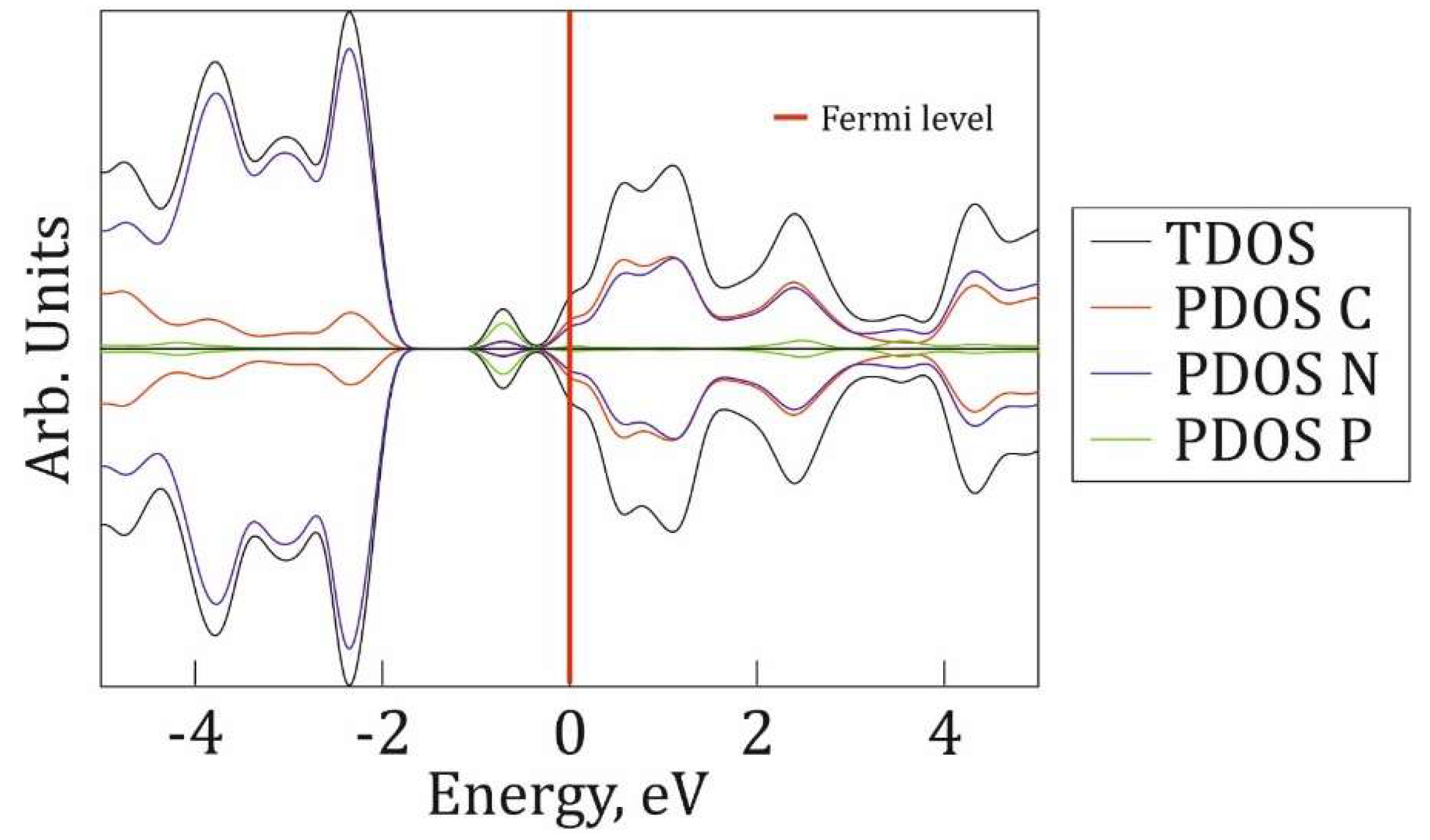

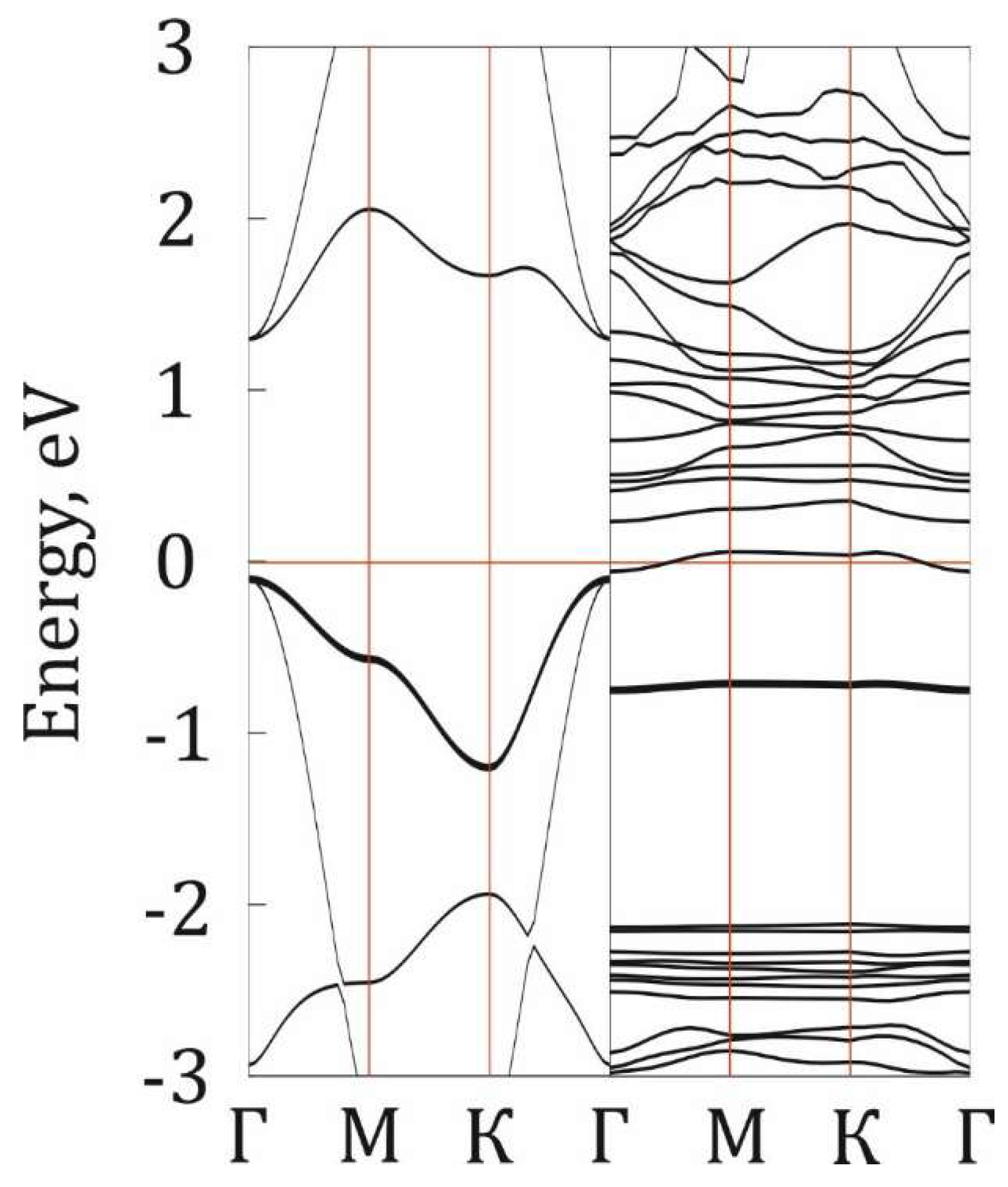

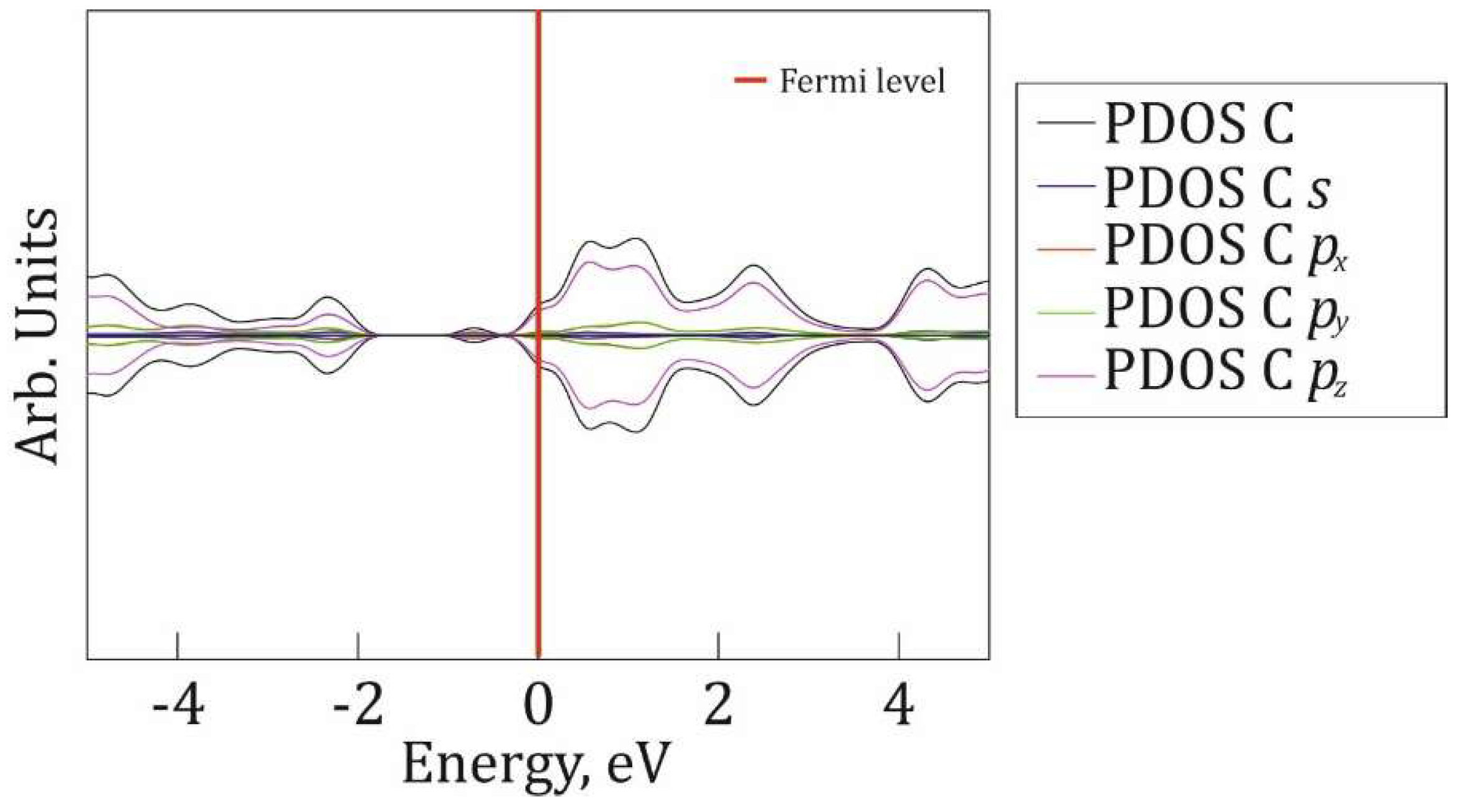

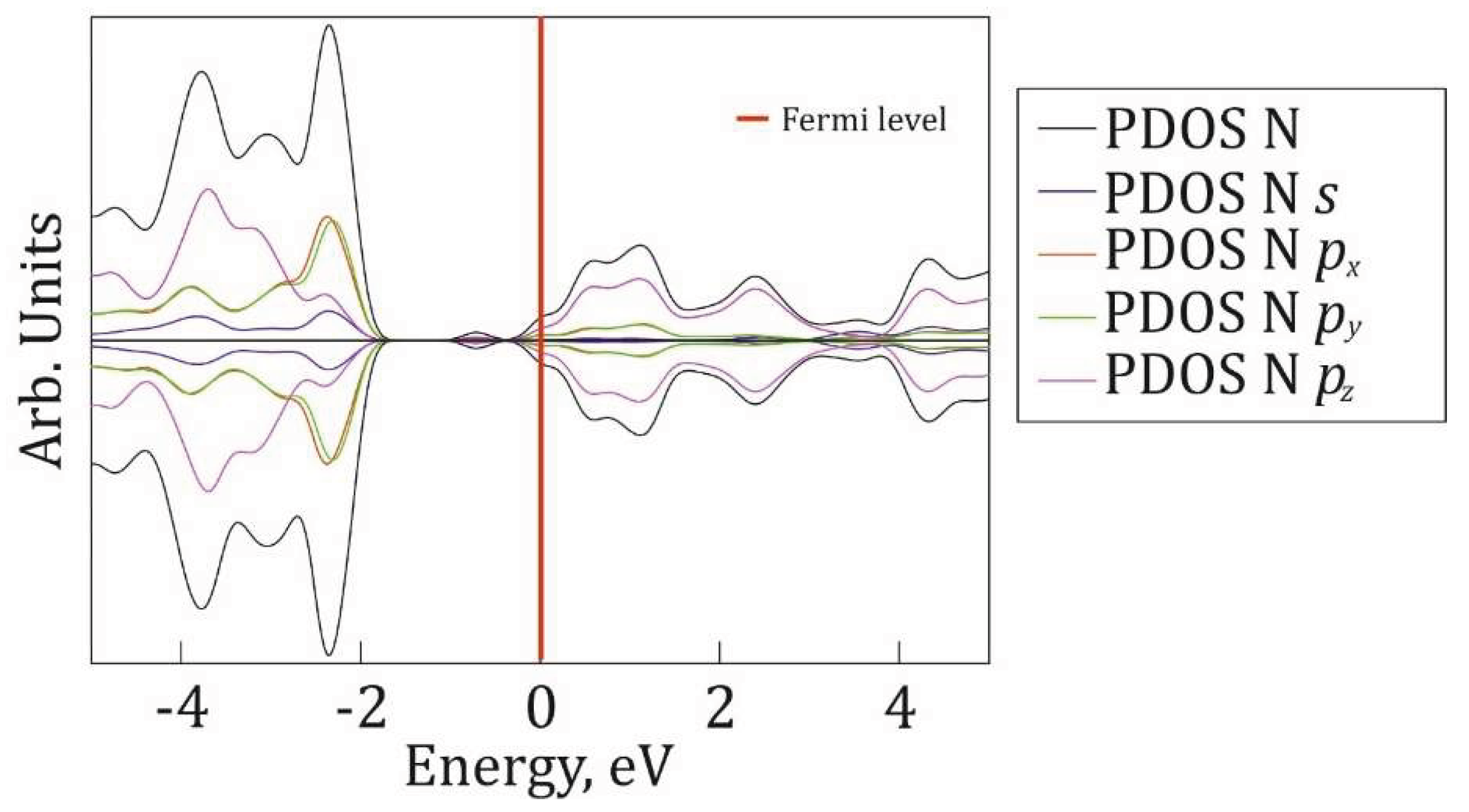

3.4. Density Functional Study of Atomic and Electronic Structure and Properties g-CN1 and P@g-CN1 Composites

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

References

- Hu, J.; Hu, C.; Liu, H.; Jiao, F. Nitrogen Self-Doped Graphitic Carbon Nitride with Optimized Band Gap as a Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalyst for Hydrogen Production and Pollutant Degradation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 2696–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, P.; Park, H.; Park, J.Y. Surface chemistry of graphitic carbon nitride: doping and plasmonic effect, and photocatalytic applications. Surf. Sci. Technol. 2023, 1, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottammal, D.; Cherusseri, J.; Thomas, S.A.; R. S., R.I.; Rajendran, D.N.; Choi, M.Y. Toward Doping in Graphitic Carbon Nitride: Progress and Perspectives on Catalytic Hydrogen Production. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2025, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, D.; Wang, F.; Chen, M. Element-doped graphitic carbon nitride: confirmation of doped elements and applications. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 3, 4370–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Yuan, X.; Pan, Y.; Liang, J.; Zeng, G.; Wu, Z.; Wang, H. Doping of graphitic carbon nitride for photocatalysis: A reveiw. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2017, 217, 388–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Xiao, W.-Z.; Wang, L.-L.; Yue, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.-Y. Half-metallic and magnetic properties in nonmagnetic element embedded graphitic carbon nitride sheets. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 22136–22143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rono, N.; Kibet, J.K.; Martincigh, B.S.; Nyamori, V.O. A review of the current status of graphitic carbon nitride. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2020, 46, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, M.; Faraji, M.; Asgari, R.; Moshfegh, A.Z. Effect of boron and phosphorus codoping on the electronic and optical properties of graphitic carbon nitride monolayers: First-principle simulations. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 97, 195428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, Q.; Qiu, J. A fantastic graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) material: Electronic structure, photocatalytic and photoelectronic properties. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2014, 20, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, P.; Park, H.; Park, J.Y. Surface chemistry of graphitic carbon nitride: doping and plasmonic effect, and photocatalytic applications. Surf. Sci. Technol. 2023, 1, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starukh, H.; Praus, P. Doping of Graphitic Carbon Nitride with Non-Metal Elements and Its Applications in Photocatalysis. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevlin, S.A.; Guo, Z.X. Anionic Dopants for Improved Optical Absorption and Enhanced Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production in Graphitic Carbon Nitride. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 7250–7256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolbov, S.; Zuluaga, S. Sulfur doping effects on the electronic and geometric structures of graphitic carbon nitride photocatalyst: insights from first principles. J. Physics: Condens. Matter 2013, 25, 085507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesavan, G.; Sorescu, D.C.; Ahamed, R.; Damodaran, K.; Crawford, S.E.; Askari, F.; Star, A. Influence of gadolinium doping on structural, optical, and electronic properties of polymeric graphitic carbon nitride. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 23342–23351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, J.; Huang, Y.; Liu, J.; Ma, M.; Liu, K.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Z.; Qu, S.; Zhang, L.; et al. Recent development in electronic structure tuning of graphitic carbon nitride for highly efficient photocatalysis. J. Semicond. 2022, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, Q.; Qiu, J. A fantastic graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) material: Electronic structure, photocatalytic and photoelectronic properties. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2014, 20, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchakova, I.; Nikolaeva, K.M.; Kovaleva, E.A.; Tomilin, F.N.; Ovchinnikov, S.G.; Tchaikovskaya, O.N.; Avramov, P.V.; Kuzubov, A.A. Potential energy surfaces of adsorption and migration of transition metal atoms on nanoporus materials: The case of nanoporus bigraphene and G-C3N4. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Fischer, A.; Goettmann, F.; Antonietti, M.; Müller, J.-O.; Schlögl, R.; Carlsson, J.M. Graphitic carbon nitride materials: variation of structure and morphology and their use as metal-free catalysts. J. Mater. Chem. 2008, 18, 4893–4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, Q.; Qiu, J. A fantastic graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) material: Electronic structure, photocatalytic and photoelectronic properties. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2014, 20, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramov, P. Topology conservation theorem, quantum instability and violation of subperiodic symmetry of complex low-dimensional lattices. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Adv. 2023, 79, C325–C325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramov, P.V.; Kuklin, A.V. Topological and quantum stability of low-dimensional crystalline lattices with multiple nonequivalent sublattices. New J. Phys. 2022, 24, 103015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Hafner, J. Ab initiomolecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 47, 558–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kresse, G.; Hafner, J. Ab initiomolecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal–amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 49, 14251–14269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes forab initiototal-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 11169–11186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohenberg, P.; Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous Electron Gas. Phys. Rev. 1964, 136, B864–B871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, W.; Sham, L.J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 1965, 140, A1133–A1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blöchl, P.E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50, 17953–17979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 1758–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 2006, 27, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Xing, Z.; Feng, Q.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, P.; Zhou, W. Sandwich-like mesoporous graphite-like carbon nitride (Meso-g-C3N4)/WP/Meso-g-C3N4 laminated heterojunctions solar-driven photocatalysts. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 568, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majdoub, M.; Anfar, Z.; Amedlous, A. Emerging Chemical Functionalization of g-C3N4: Covalent/Noncovalent Modifications and Applications. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 12390–12469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patnaik, S.; Martha, S.; Parida, K.M. An overview of the structural, textural and morphological modulations of g-C3N4towards photocatalytic hydrogen production. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 46929–46951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Han, C.; Xiao, X.; Guo, L.; Li, Y. Enhanced visible light photocatalytic hydrogen evolution of sulfur-doped polymeric g-C3N4 photocatalysts. Mater. Res. Bull. 2013, 48, 3919–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Zhu, C.; Wei, S.; Chen, L.; Ji, H.; Su, T.; Qin, Z. Phosphorus-Doped Hollow Tubular g-C3N4 for Enhanced Photocatalytic CO2 Reduction. Materials 2023, 16, 6665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).