Submitted:

23 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Study Description

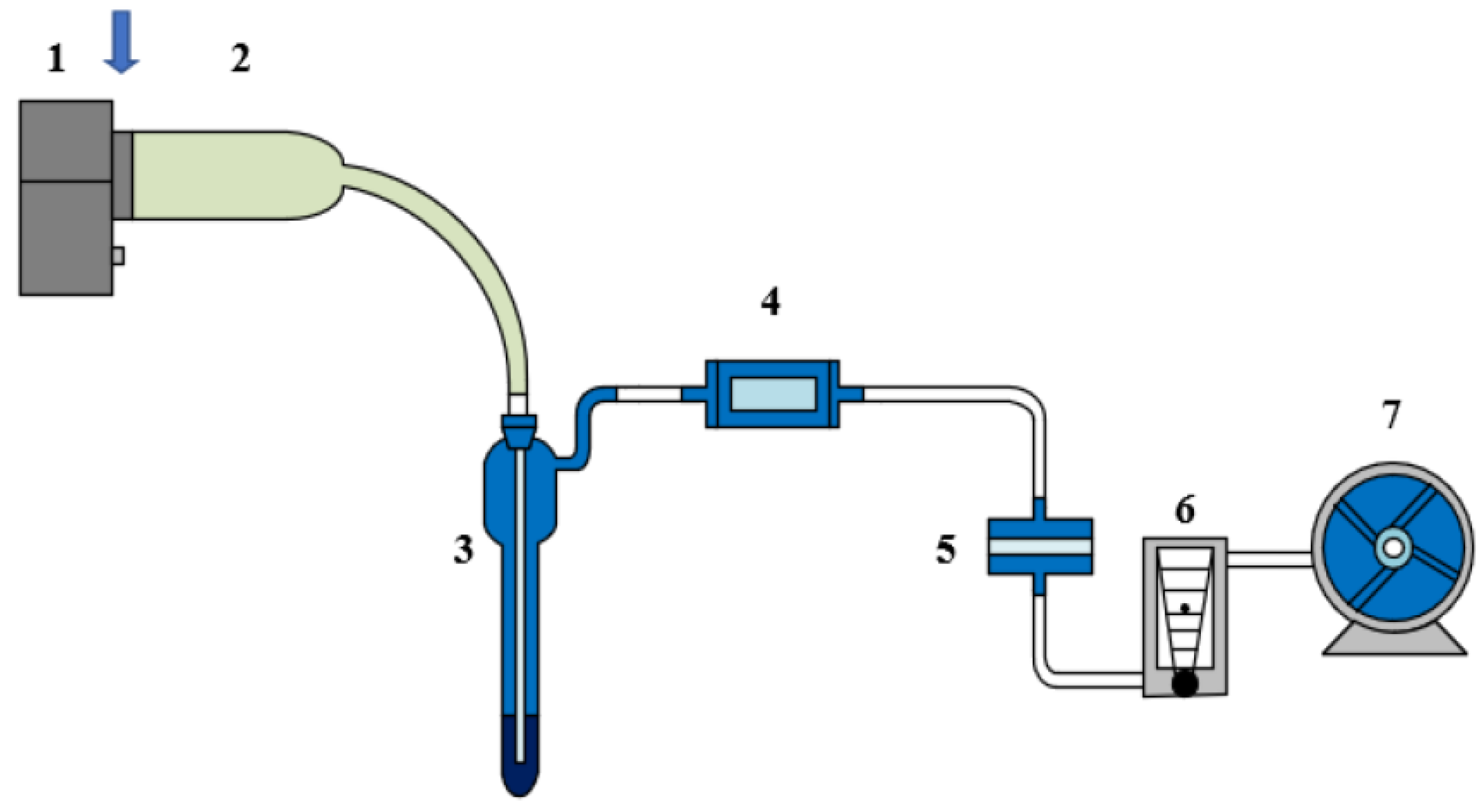

2.2. Experimental Design and Control Setup

2.3. Measurement Methods and Quality Control

2.4. Data Processing and Model Equations

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

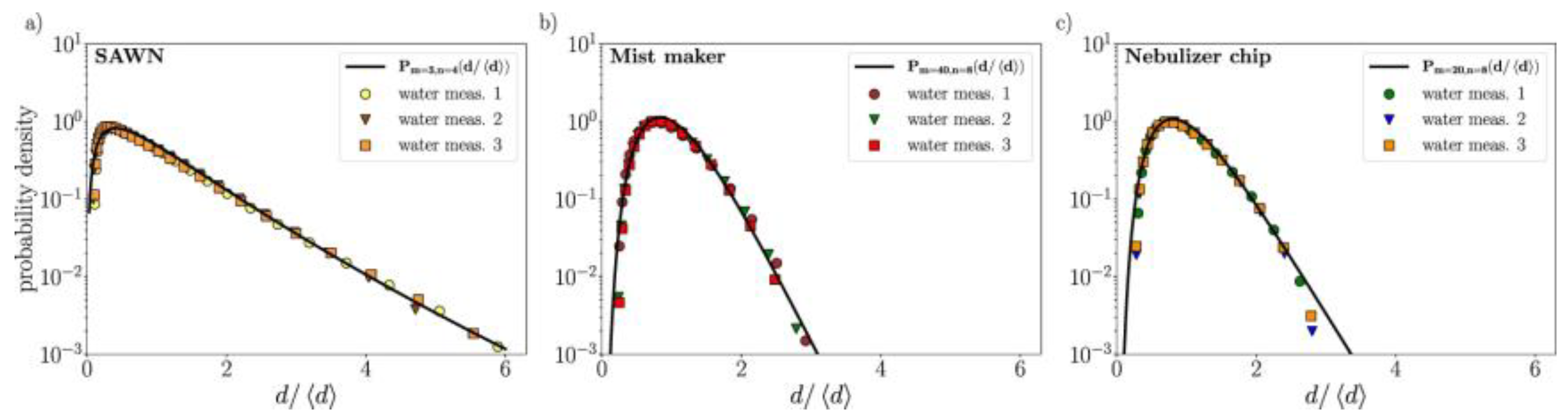

3.1. Frequency Controls Droplet Size and Aerosol Quality

3.2. Lung Deposition and Spatial Uniformity

3.3. Mucus Penetration Depth and Epithelial Access

3.4. Comparison with Prior Work and Implications for Therapy

4. Conclusion

References

- Cojocaru, E.; Petriș, O R. , & Cojocaru, C. Nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems in inhaled therapy: improving respiratory medicine. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 1059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zha, D.; Mahmood, N.; Kellar, R. S., Gluck, J. M., & King, M. W. (2025). Fabrication of PCL Blended Highly Aligned Nanofiber Yarn from Dual-Nozzle Electrospinning System and Evaluation of the Influence on Introducing Collagen and Tropoelastin. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering.

- Patel, B.; Gupta, N.; Ahsan, F. Barriers that inhaled particles encounter. Journal of Aerosol Medicine and Pulmonary Drug Delivery 2024, 37, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadhav, K.; Kole, E.; Abhang, A.; Rojekar, S.; Sugandhi, V.; Verma, R. K. ,... & Naik, J. Revealing the potential of nano spray drying for effective delivery of pharmaceuticals and biologicals. Drying Technology 2025, 43, 90–113. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K. , Lu, Y., Hou, S., Liu, K., Du, Y., Huang, M.,... & Sun, X. Detecting anomalous anatomic regions in spatial transcriptomics with STANDS. Nature Communications 2024, 15, 8223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yiannacou, K. (2025). Machine Learning Based Acoustic Manipulation of Particles and Droplets inside Microfluidic Devices.

- Jadhav, K. , Jhilta, A., Singh, R., Sharma, S., Negi, S., Ahirwar, K.,... & Verma, R. K. Trans-nasal brain delivery of anti-TB drugs by methyl-β-cyclodextrin microparticles show efficient mycobacterial clearance from central nervous system. Journal of Controlled Release 2025, 378, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bain, A. , Vasdev, N., Muley, A., Sengupta, P., & Tekade, R. K. Mucus-Penetrating PEGylated Nanoshuttle for Enhanced Drug Delivery and Healthcare Applications. Indian Journal of Microbiology 2025, 65, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D. , Liu, S., Chen, D., Liu, J., Wu, J., Wang, H.,... & Suk, J. S. A two-pronged pulmonary gene delivery strategy: a surface-modified fullerene nanoparticle and a hypotonic vehicle. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2021, 60, 15225–15229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mansour, H. M. , Muralidharan, P., & Hayes Jr, D. Inhaled nanoparticulate systems: composition, manufacture and aerosol delivery. Journal of Aerosol Medicine and Pulmonary Drug Delivery 2024, 37, 202–218. [Google Scholar]

- Tillett, B. J. , Dwiyanto, J., Secombe, K. R., George, T., Zhang, V., Anderson, D.,... & Hamilton-Williams, E. E. SCFA biotherapy delays diabetes in humanized gnotobiotic mice by remodeling mucosal homeostasis and metabolome. Nature communications 2025, 16, 2893. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dash, P. K. , Chen, C., Kaminski, R., Su, H., Mancuso, P., Sillman, B.,... & Khalili, K. CRISPR editing of CCR5 and HIV-1 facilitates viral elimination in antiretroviral drug-suppressed virus-infected humanized mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2023, 120, e2217887120. [Google Scholar]

- Sosnowski, T. R. Towards more precise targeting of inhaled aerosols to different areas of the respiratory system. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zha, D. , Gamez, J., Ebrahimi, S. M., Wang, Y., Verma, N., Poe, A. J.,... & Saghizadeh, M. Oxidative stress-regulatory role of miR-10b-5p in the diabetic human cornea revealed through integrated multi-omics analysis. Diabetologia 2025, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimiazar, M. , & Ashgriz, N. Aerosol generation by ultrasonic atomization of nanoliter liquid volumes. Physics of Fluids 2025, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J. (2025). Building a Structured Reasoning AI Model for Legal Judgment in Telehealth Systems.

- Talaat, M. (2024). Revolutionizing Respiratory Medicine: An Integrated Computational and Experimental Approach to Inhalation Dosimetry and Disease Severity Classification (Doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts Lowell).

- Wang, Y. , Wen, Y., Wu, X., Wang, L., & Cai, H. (2025). Assessing the Role of Adaptive Digital Platforms in Personalized Nutrition and Chronic Disease Management.

- Doan, H. (2025). Ultrasound-Induced Dynamics of Nanodroplets and Microbubbles in Synthetic Cystic Fibrosis Mucus: Toward Pulmonary Drug Delivery and Mucus Rheology Assessment.

- Wen, Y. , Wu, X., Wang, L., Cai, H., & Wang, Y. Application of Nanocarrier-Based Targeted Drug Delivery in the Treatment of Liver Fibrosis and Vascular Diseases. Journal of Medicine and Life Sciences 2025, 1, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).