1. Introduction

Global adult obesity rates have more than doubled from 7% in 1990 to 16% in 2022 [

1]. Obesity has been associated with an increased risk for mood disorders [

2,

3], which are often characterized by alterations in emotional processing [

4] and most commonly manifest during young adulthood [

5]. Similarly, obesity is linked to alterations in affective processing, namely enhanced automatic negative affective processing (i.e., more difficulties in suppressing the automatic processing of information associated with negative emotions [

6,

7,

8]) and, to a lesser extent, attenuated automatic positive affective processing (i.e., diminished automatic processing of information associated with positive emotions [

9]). In contrast to these findings, however, an exploratory meta-analysis comprised of 13 studies reported that that emotional processing was not significantly impaired in those with obesity compared to controls, but this meta-analysis included studies that were comprised of participants across all age groups [

10]. A preliminary study also did not find a deficit in affective processing among young preadolescents and adolescents with obesity, although this study did not include young adults [

11]. Hence, evidence of whether obesity influences affective processing in young adults remains inconsistent in the prevailing body of literature. However, considering that global rates of mental disorders have increased, especially mood disorders [

12], it is crucial to clarify whether modifiable risk factors such as excess adiposity is associated with deficits in affective processing, particularly in an age group when such disorders are most likely to emerge.

Additionally, insulin resistance (IR) is also a risk factor for mood disorders [

13,

14]. Insulin, a pancreatic hormone, functions in whole-body glycolytic processes [

15]. IR emerges when target tissues are less responsive to insulin stimulation [

16]. Although IR has also been consistently correlated with more emotional processing impairments in children [

17], younger adult females with polycystic ovary syndrome [

18], and male mice [

19], work investigating the relationship between IR and affective processing impairments among otherwise healthy younger adults remains underexplored and, therefore, also warrants investigation in this population.

Neurophysiologically, affective processing neurocircuitry involves widespread brain regions. Affective processing commences with an automatic, nonconscious response to an emotional stimulus that is signaled by increased amygdala activity [

20]. Information about emotional arousal is subsequently relayed from the amygdala and basal ganglia to the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (vlPFC), anterior insula, supplementary motor area, angular gyrus, and superior temporal gyrus. The former two regions evaluate the affective input to determine whether the affective arousal necessitates emotional regulation, while the lattermost three regions respectively simulate the motor, somatosensory, and language processes associated with the affective input to enhance an emotional experience. If regulation is required, the vlPFC and anterior insula further project this information to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), where affect regulation occurs (i.e., downregulation of Negatively-valenced stimuli and/or upregulation of Positively-valenced stimuli). Subsequently, the dlPFC projects a feedforward signal directly or through the anterior middle cingulate gyrus back to the amygdala, basal ganglia, supplementary motor area, as well as the angular and superior temporal gyri, which, in turn, contribute to the production of a newly-regulated emotional state [

21].

Obesity and IR may impair affective processing by inducing brain structural and functional alterations in regions that modulate affective processing. For example, greater adiposity has been linked to fewer dopamine striatal D2 receptors [

22], which, in turn, associates with impaired prefrontal metabolism within the orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortices in those with obesity [

23]. These neural modifications may reduce prefrontal modulation of affective input from the amygdala and basal ganglia, resulting in amplified responses to unpleasant stimuli and consequent enhanced negative affective processing. Furthermore, considering that antagonistic action against dopamine D2/D3 receptors has been found to attenuate striatal activity in response to rewarding stimuli [

24], this may partially explain why blunted positive affective processing has also been found in these subjects [

9]. Additionally, a neuroimaging study observed blunted activity in the amygdalae of subjects with obesity, which was linked to a greater susceptibility to feelings of negative affectivity, particularly fear [

25]. IR is also correlated with brain structural and functional alterations. Peripheral IR impedes central signaling, causing central IR [

26] and hindering brain glucose metabolism. Chronic central IR engenders progressive brain atrophy [

27]. IR-induced atrophy is most pronounced in brain structures that function in affective processing/regulation (e.g., prefrontal cortices, medial temporal lobe, parietal gyri [

28]), which may consequently impede emotional processing function over time. Central IR has also been associated with impediments in dopamine turnover and mitochondrial dysfunction, which, in turn, was related to a higher risk of mood disorders [

29]. These findings collectively suggest that impairments in affective processing among those with obesity and/or IR may be partially attributed to the diminished top-down modulation of affectivity due to obesity-/IR-linked brain structural and functional impairments.

The prevailing empirical evidence has most frequently utilized functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to investigate if obesity and/or IR associates with deficits[32–35 in neural activity and underlying affective processing [

17,

18,

25,

30,

31]. Although electroencephalography (EEG) has been used extensively in studies of emotional processing (e.g., [

32,

33,

34,

35]), neuroelectrophysiological investigations of whether adiposity and IR influence brain function and affective processing outcomes are remarkably underexplored to date. The limited evidence that has investigated this, however, focused on older adults [

36], leaving these interrelationships unexplored in younger adults. Yet, considering that young adulthood is the most frequent period for the onset of mood disorders [

37], further exploration of how risk factors may be related to alterations in not just hemodynamic but also electrophysiological properties of brain function and emotional processing outcomes is crucial in this age group. Such electrophysiological properties of brain function can be captured by EEG. During a task, electrical activity recorded by EEG is utilized to quantified event-related potentials (ERPs), which are voltage fluctuations captured by an electroencephalogram that are induced by a particular event or stimulus [

38]. Each ERP component is functionally differentiated according to: 1) polarity (direction of amplitude deflection); 2) scalp distribution; 3) latency (time and duration of electrocortical activity); and 4) sensitivity to particular task-linked manipulations [

39].

Two ERP components—early posterior negativity (EPN) and late positive potential (LPP)—index affective processing [

40]. EPN is a negative, occipitotemporal potential with an electrocortical activity trough approximately 200–300 milliseconds (ms) post-stimulus exposure. Larger (i.e., more negative) EPN voltage amplitudes reflect an increase in postsynaptic potentials in the extrastriate visual cortex [

41] and indicate elevated automatic, nonconscious, visual attention to and sensory processing of emotional stimuli [

42]. EPN is particularly sensitive to Positively-valenced stimuli [

43]. LPP is a positive, centroparietal potential that commences 300–400 ms post-stimulus exposure [

44,

45]. Higher (i.e., more positive) LPP voltage amplitudes reflect an increase in prolonged postsynaptic potentials in the parietal and prefrontal cortices [

46], and amplitude deflections are consistently higher in response to emotional versus neutral stimuli [

47,

48]. As LPP amplitudes are generally sustained throughout the continuance of stimulus presentation [

44], LPP is often segmented into three distinctive latency windows that represent neural responses during three sequential affective processing stages: 1) automatic emotional response; 2) sustained attention to and ongoing evaluation of emotional stimuli; and 3) prolonged affective processing, affect regulation, and possibly memory encoding [

40,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54]. LPP amplitudes in the early latency window peak in the centroparietal area [

54,

55,

56] and functionally index emotional salience in terms of motivated attention during passive picture-viewing tasks, with amplitudes reflecting the level of arousal elicited by emotional stimuli [

49,

50,

54]. In contrast, LPP amplitudes during the later latency windows shift to a frontal distribution [

54,

55,

56] and reflect greater processing of as well as sustained attention to affective stimuli relative to neutral during passive picture-viewing tasks [

50,

51,

54]. Late-window LPP amplitudes may also be more sensitive to valence-specific differentiation compared to the early-window LPP [

57]. As such, individuals with obesity and IR would be expected to have higher late-window LPP amplitudes and enhanced affective processing in response to unpleasant stimuli as well as lower late-window LPP amplitudes and attenuated affective processing in response to pleasant stimuli compared to lean and insulin-sensitive individuals, respectively.

Nevertheless, no studies to date have used EEG to investigate whether the relationships between brain function and negative or positive affective processing may differ by levels of body fat and IR in younger adults. To help fill these gaps, this study aimed to investigate whether obesity and/or IR moderate the links between brain potentials and underlying negative and/or positive affective processing parameters in younger adults. The central hypotheses were: 1) younger adults without obesity or IR will show attenuated negative affective processing through lower late-window LPP amplitudes in response to unpleasant stimuli compared to respective counterparts; and 2) young adults without obesity or IR will show enhanced positive affective processing through higher late-window LPP amplitudes in response to pleasant stimuli compared to respective counterparts.

4. Discussion

Evidence to support whether obesity is associated with deficits in emotional processing in young adults has been inconsistent in the prevailing literature. Furthermore, whether IR is linked to affective processing impairments in otherwise healthy young adults remains unexplored to date. Furthermore, neuroelectrophysiological investigations of whether adiposity and IR modify the correlation between electrocortical activity and affective processing in young adults is lacking. Therefore, EEG was utilized to investigate whether obesity and/or IR moderated brain potentials and associated affective processing outcomes in young adults.

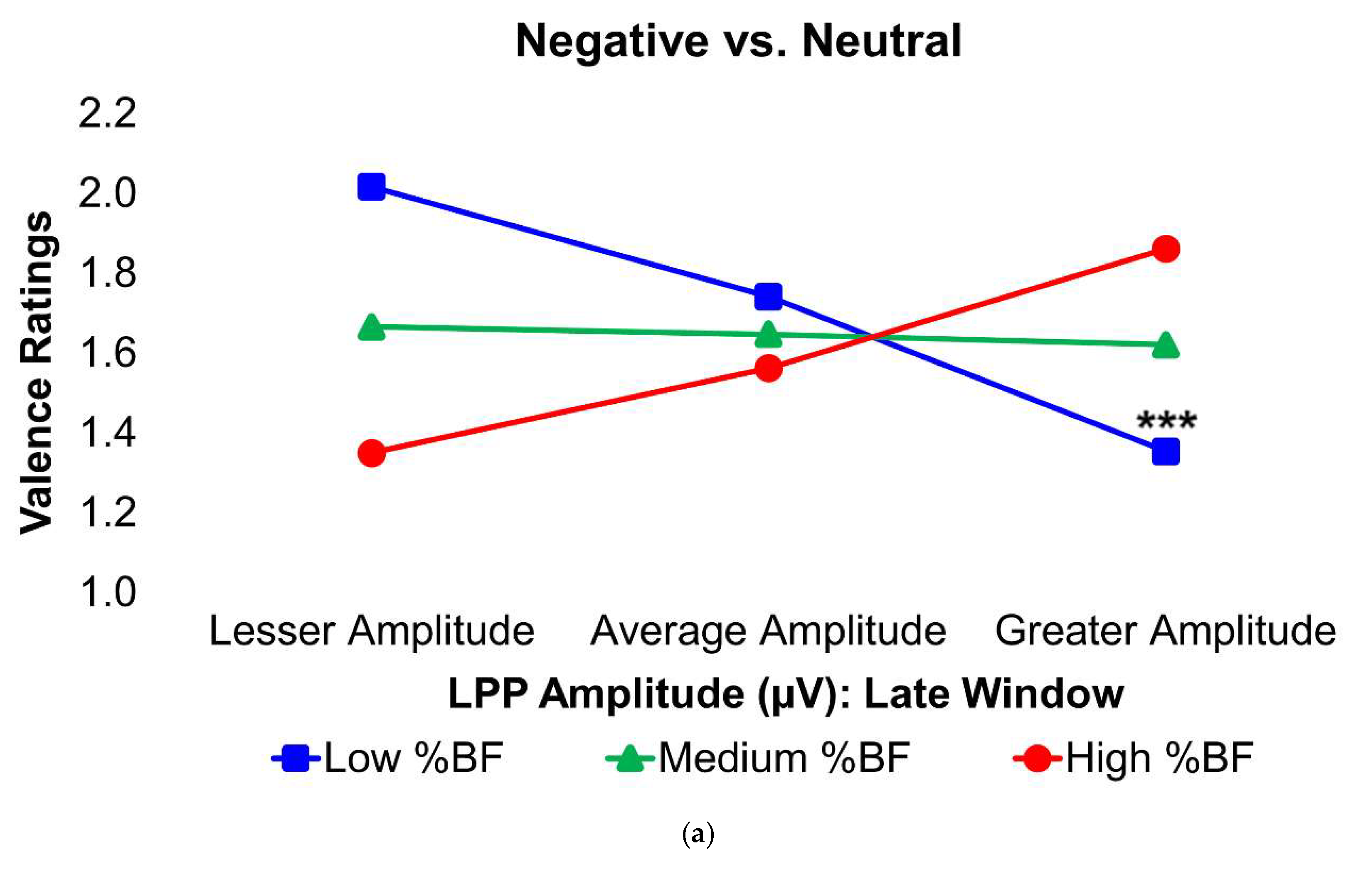

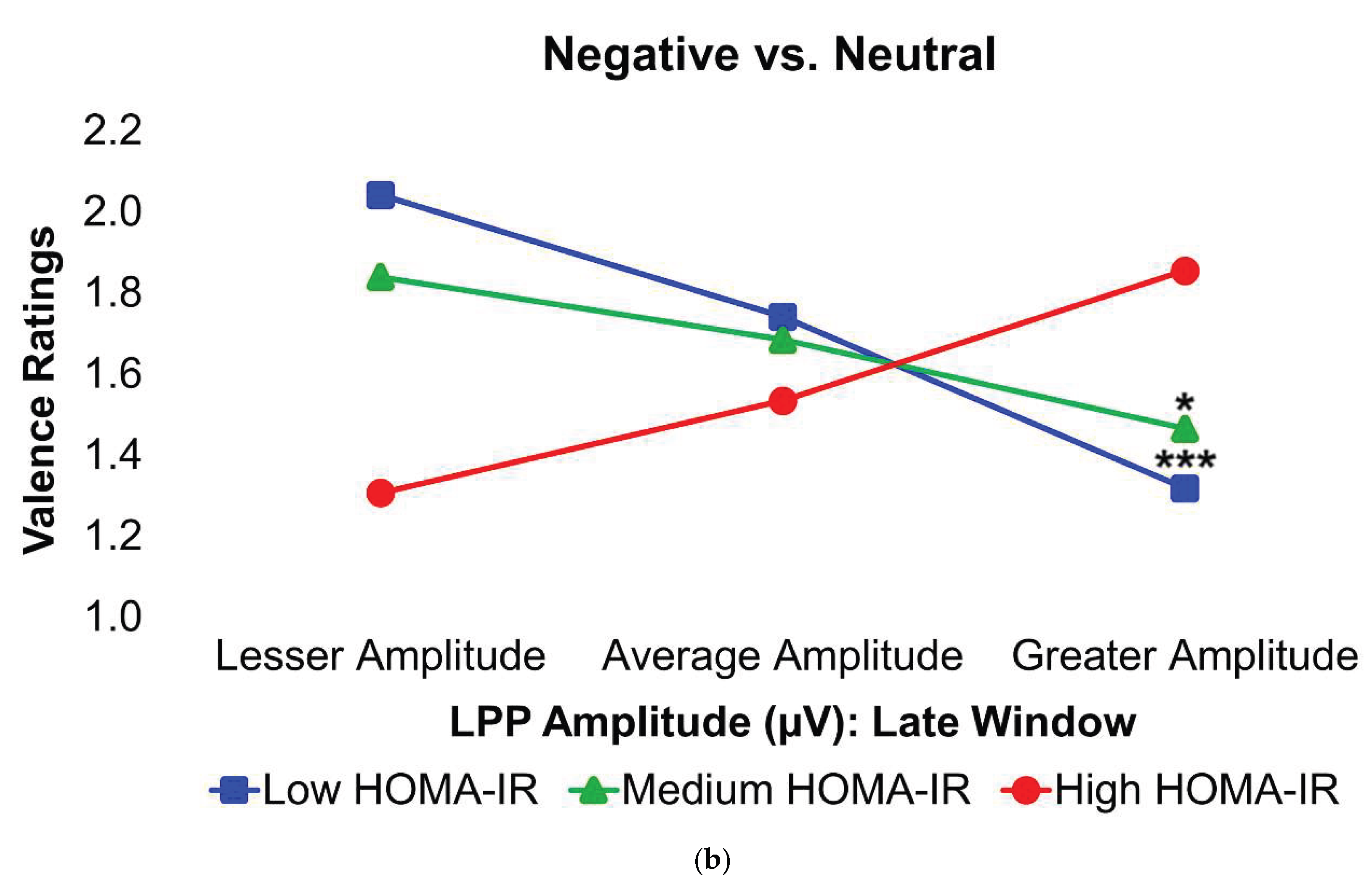

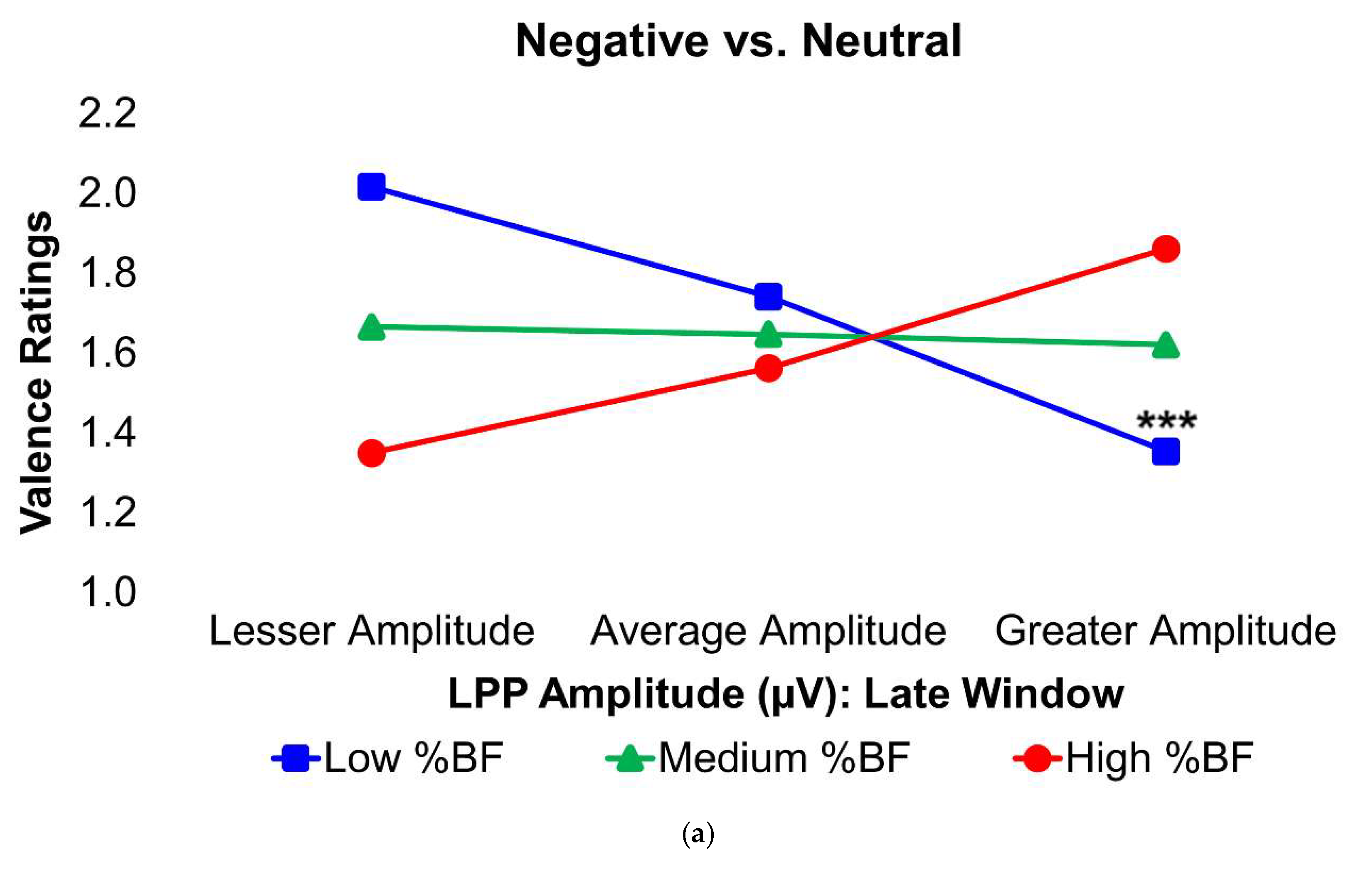

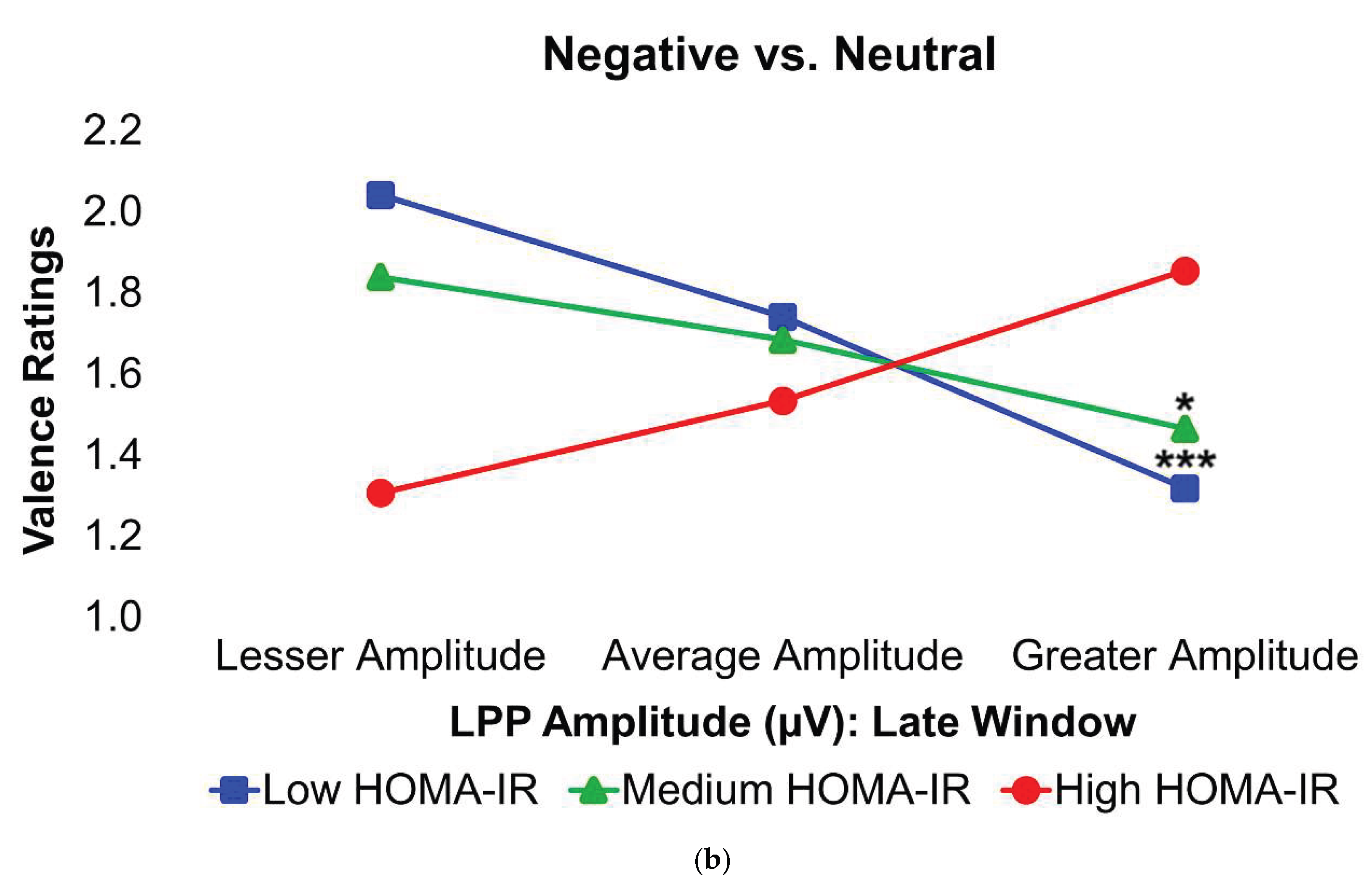

In the Negative–Neutral trials, young adults without obesity or IR displayed significantly greater LPP amplitudes during the late latency window, in contrast with what was expected. However, among these participants, larger LPP responses were linked to less negative ratings of unpleasant images, suggesting that stronger neural engagement was associated with a dampening of negative emotional experience. By contrast, this relationship was absent in young adults with obesity and/or IR, indicating a disruption in the typical coupling between neural activity and emotional evaluation. Ordinarily, increased activity in the dlPFC in response to unpleasant stimuli reflects more top-down control to suppress affective responses [

21], with successful down-regulation of Negatively-valenced stimuli generally being subsequently manifested as reduced LPP amplitudes [

86]. Hence, an inverse relationship between late-window LPP amplitudes and valence ratings (where lower numerical values indicated less negative valence ratings) to unpleasant stimuli in lean, insulin-sensitive young adults was unexpected. Despite this, an inverse LPP amplitudes–valence ratings correlation is in congruence with findings from several studies (e.g., [

87,

88,

89,

90]). Rather than indicating an unsuccessful dampening of Negatively-valenced stimuli and a concomitant enhancement of negative affective processing, higher LPP amplitudes in the late latency window may instead reflect more effortful spontaneous emotion regulation, as previously suggested [

87,

90]. Taken together, these findings suggest that lean, insulin-sensitive individuals may attenuate negative affective processing of unpleasant stimuli through greater cognitive effort to automatically regulate these Negatively-valenced stimuli spontaneously.

While these results show that both BF% and IR are independent moderators of brain potentials and negative affective processing in young adults, prior work has suggested that IR may be one mechanism through which obesity alters the neural basis of negative affective processing rather than acting as isolated moderators. Excess body fat has been identified as an independent inducer of IR [

91,

92,

93], predominantly via the promoting cell dysfunction and inflammation [

94]. Given this, it is unsurprising that obesity and IR are risk factors for many of the same health conditions, including mood disorders [

2,

3,

19,

29] and emotional processing modifications [

7,

9,

18]. Although a feasible hypothesis, this study lacked the statistical power to test both moderators simultaneously. Future research should test these associations utilizing a larger sample and longitudinal designs.

In the contrasted Positive–Neutral valence trial, neither obesity nor IR were found to moderate the links between LPP amplitudes across any of the latency windows and affective processing scores, implying that neural responses to pleasant stimuli and associated positive affective processing may be spared from obesity- and/or IR-induced brain structural and functional alterations in young adulthood. These results are in concurrence with some [

95,

96], but not all [

97,

98] previous findings. The null results found for positive affective processing parameters in this study may be in part explained by differences in neurocircuitry between negative versus positive affective processing. Specifically, the processing of negative emotions more heavily involves activity from the amygdala, anterior insula, anterior cingulate and visual cortices, dlPFC, and vlPFC [

99,

100], whereas the processing of positive emotions more substantially relies upon activity in the medial prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortices, ventral striatum, nucleus accumbens, and ventral tegmental area [

101,

102]. Hence, the brain structures involved in positive affective processing may be less susceptible to obesity- and/or IR-linked structural and functional alterations compared to structures that modulate negative affective processing. Still, future studies will be crucial to improving understanding of whether obesity and IR impact brain potentials and positive affective processing in young adulthood.

Moreover, obesity and IR did not moderate the relationships between brain potentials and underlying affective processing in the contrasted Negative–Positive condition. This suggests that, similarly to the early-window LPP, late-window LPP may also be more strongly driven by arousal than by valence and, thus, may not be valence-biased [

44,

103,

104], although this contrasts some prior study findings (e.g., [

57]). Moreover, inconsistencies exist in the body of literature that has compared the LPP responses to unpleasant versus pleasant stimuli, with some studies finding no differences in LPP amplitudes between either emotional condition across a wide range of age groups [

46,

105] and other studies finding valence-specific differentiation, although these findings appeared to be arousal-dependent [

57,

104]. Significant methodological, LPP quantification, and sample heterogeneity may partially account for such discordant findings.

Finally, BF% and HOMA-IR did not moderate the links between EPN amplitudes and affective processing parameters across any of the contrasted valence conditions. Hence, this suggests that obesity and IR do not impact visual attention allocation to emotional versus neutral stimuli in young adulthood. As far as the authors are aware, this study is the first to investigate whether obesity and/or IR moderated the relationship between EPN amplitudes and affective processing. Nonetheless, these results are not surprising when considering that the scalp distribution of the EPN component over the occipitotemporal sites reflects visual cortical activity [

106], a largely insulin-independent region [

107]. One study demonstrated this by showing that insulin infusion had no effect on subsequent visual evoked potentials [

108]. Nevertheless, additional research is needed to clarify whether obesity and/or IR influence EPN amplitudes and underlying visual attention allocation to emotional versus neutral stimuli.

This study was not without limitations. First, the sample size was small, hence limiting the generalizability of this study’s findings and barring the simultaneous testing of both moderators in one model due to being underpowered. Second, the utilization of the EEG neuroimaging modality in conjunction with the cross-sectional study design barred any causal implications. Third, neural activity measured during exposure to emotional images in a laboratory setting may not necessarily translate to real-world settings. Fourth, HOMA-IR is an index of short-term IR and may not have accurately captured chronic IR in all subjects.

This study also included several strengths. First, the central research questions were novel. Second, EEG provided an inexpensive, non-invasive neuroimaging approach with superior temporal resolution [

109,

110] compared to fMRI. Third, body composition was measured directly via DEXA, which provided a significantly more accurate quantification of BF% in comparison to indirect measures (e.g., BMI [

111]).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.W.; methodology, B.L., B.K., T.W. and K.M.; software, A.W.; validation, B.L. and B.K.; formal analysis, B.L.; investigation, B.K., T.W. and K.M.; resources, A.W.; data curation, B.L.; writing—original draft preparation, B.L.; writing—review and editing, B.L., B.K., T.W., K.M., Q.W., P.M., M.F., A.S. and A.W.; visualization, B.L. and B.K.; supervision, B.K., T.W., K.M., Q.W. and A.W.; project administration, A.W.; funding acquisition, A.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

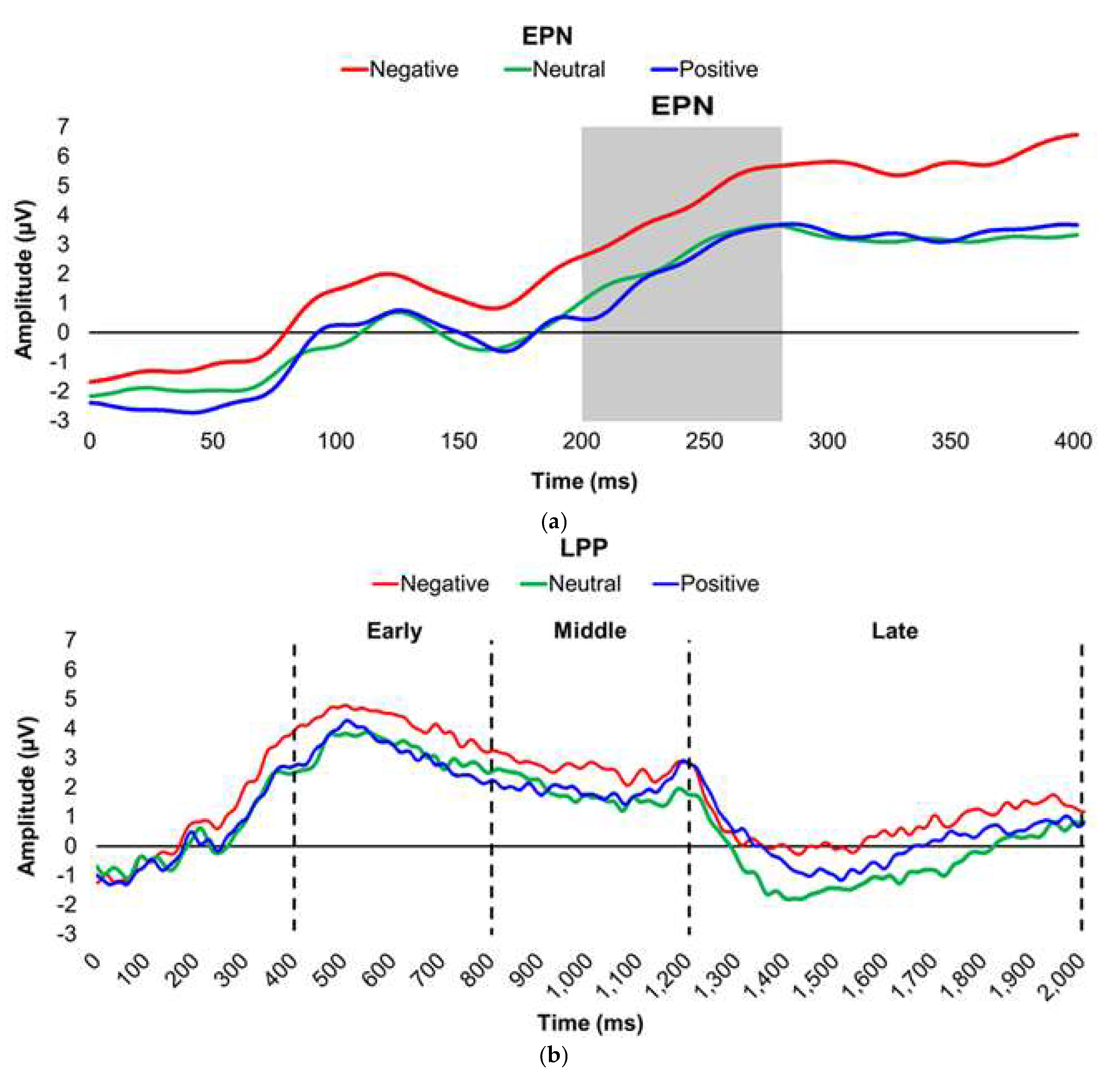

Figure 1.

Line graphs depict the grand-mean averaged EPN (a) and LPP (b) waveforms across all participants after viewing Negatively- (red), Neutrally- (green), and Positively-valenced (blue) pictures during an International Affective Picture System task. Amplitude was measured in microvolts (µV); time was measured in milliseconds. EPN = early posterior negativity; LPP = late positive potential; ms = milliseconds. Early, middle, and late latency windows of the LPP component = 400–800 ms, 800–1,200 ms, and 1,200–2,000 ms post-stimulus onset, respectively.

Figure 1.

Line graphs depict the grand-mean averaged EPN (a) and LPP (b) waveforms across all participants after viewing Negatively- (red), Neutrally- (green), and Positively-valenced (blue) pictures during an International Affective Picture System task. Amplitude was measured in microvolts (µV); time was measured in milliseconds. EPN = early posterior negativity; LPP = late positive potential; ms = milliseconds. Early, middle, and late latency windows of the LPP component = 400–800 ms, 800–1,200 ms, and 1,200–2,000 ms post-stimulus onset, respectively.

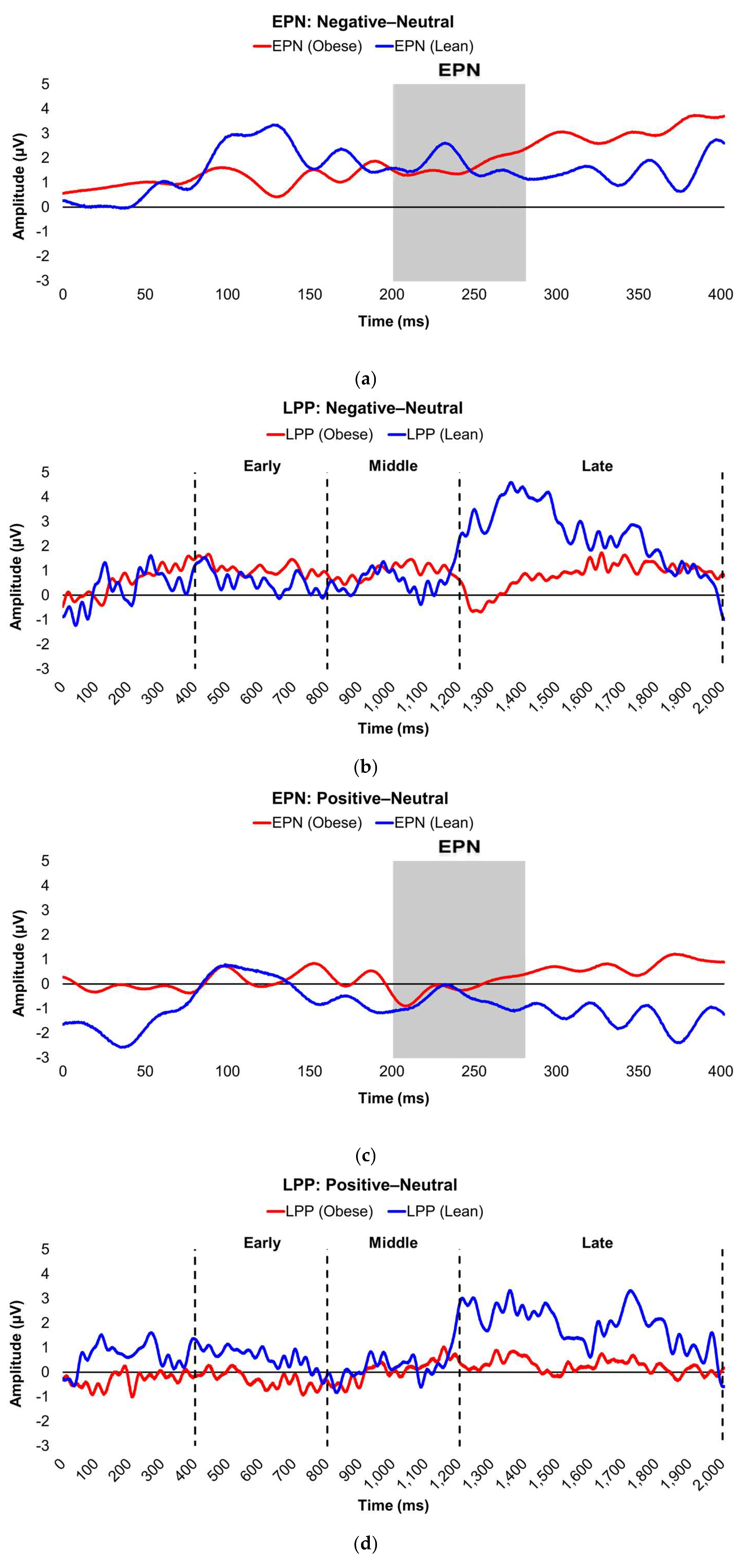

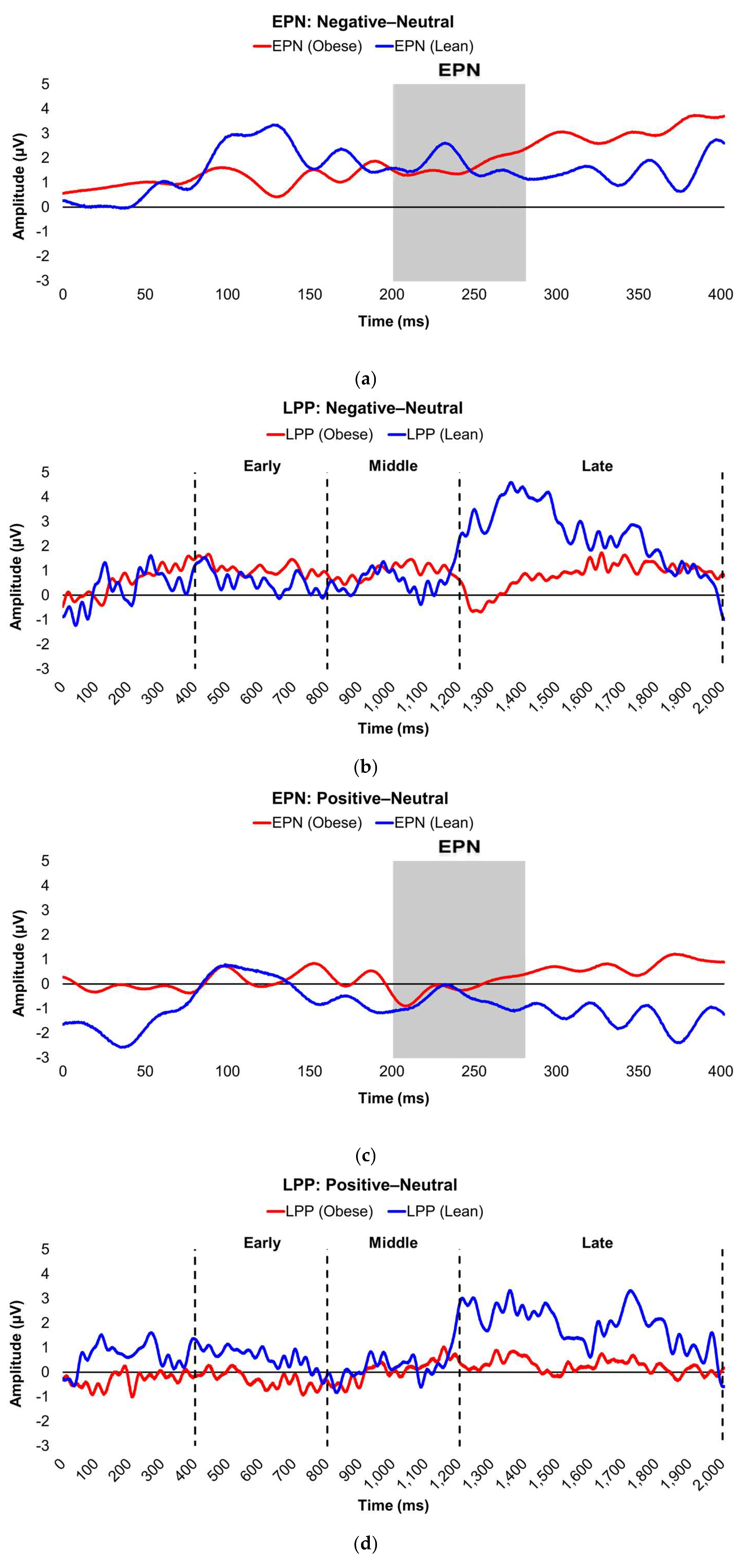

Figure 2.

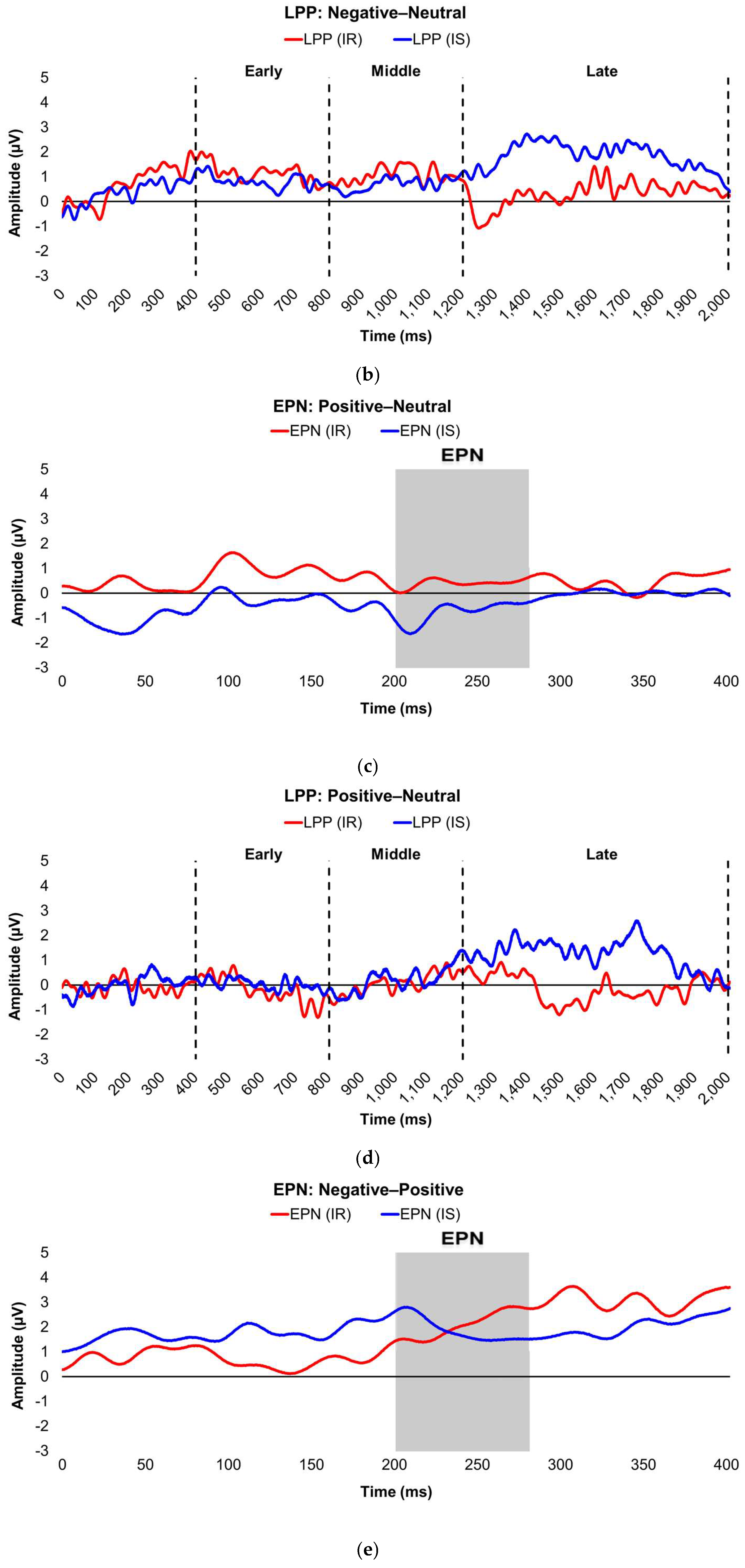

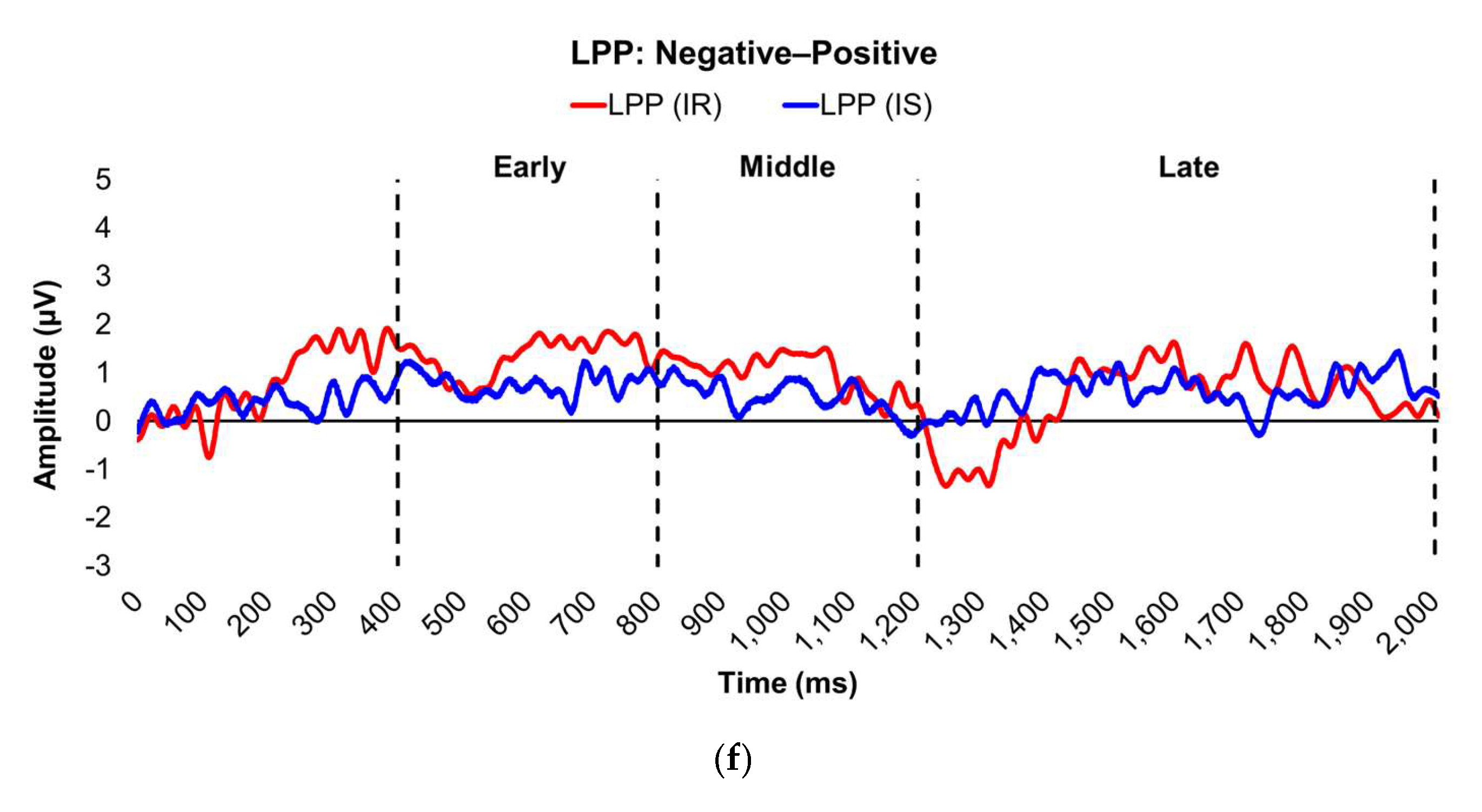

Line graphs show the comparisons of the differenced grand-mean averaged EPN (left) and LPP (right) waveforms in the contrasted picture conditions (i.e., Negative minus Neutral (a–b), Positive minus Neutral (c–d), and Negative minus Positive (e–f) EPN and LPP waveforms) between lean (body fat percentage of <25% (males) and <35% (females), in blue) versus obese (body fat percentage of ≥25% (males) and ≥35% (females), in red) subjects. Amplitude was measured in microvolts (µV); time was measured in milliseconds. EPN = early posterior negativity; LPP = late positive potential; ms = milliseconds. Early, middle, and late latency windows of the LPP component = 400–800 ms, 800–1,200 ms, and 1,200–2,000 ms post-stimulus onset, respectively. For the EPN component, lower difference score values reflect overall larger amplitude deflections in response to the emotionally-valenced condition compared to the Neutrally- or oppositely-valenced condition, whereas higher difference scores indicate overall larger amplitude deflections in response to the emotionally-valenced condition compared to the Neutrally- or oppositely-valenced condition for the LPP component.

Figure 2.

Line graphs show the comparisons of the differenced grand-mean averaged EPN (left) and LPP (right) waveforms in the contrasted picture conditions (i.e., Negative minus Neutral (a–b), Positive minus Neutral (c–d), and Negative minus Positive (e–f) EPN and LPP waveforms) between lean (body fat percentage of <25% (males) and <35% (females), in blue) versus obese (body fat percentage of ≥25% (males) and ≥35% (females), in red) subjects. Amplitude was measured in microvolts (µV); time was measured in milliseconds. EPN = early posterior negativity; LPP = late positive potential; ms = milliseconds. Early, middle, and late latency windows of the LPP component = 400–800 ms, 800–1,200 ms, and 1,200–2,000 ms post-stimulus onset, respectively. For the EPN component, lower difference score values reflect overall larger amplitude deflections in response to the emotionally-valenced condition compared to the Neutrally- or oppositely-valenced condition, whereas higher difference scores indicate overall larger amplitude deflections in response to the emotionally-valenced condition compared to the Neutrally- or oppositely-valenced condition for the LPP component.

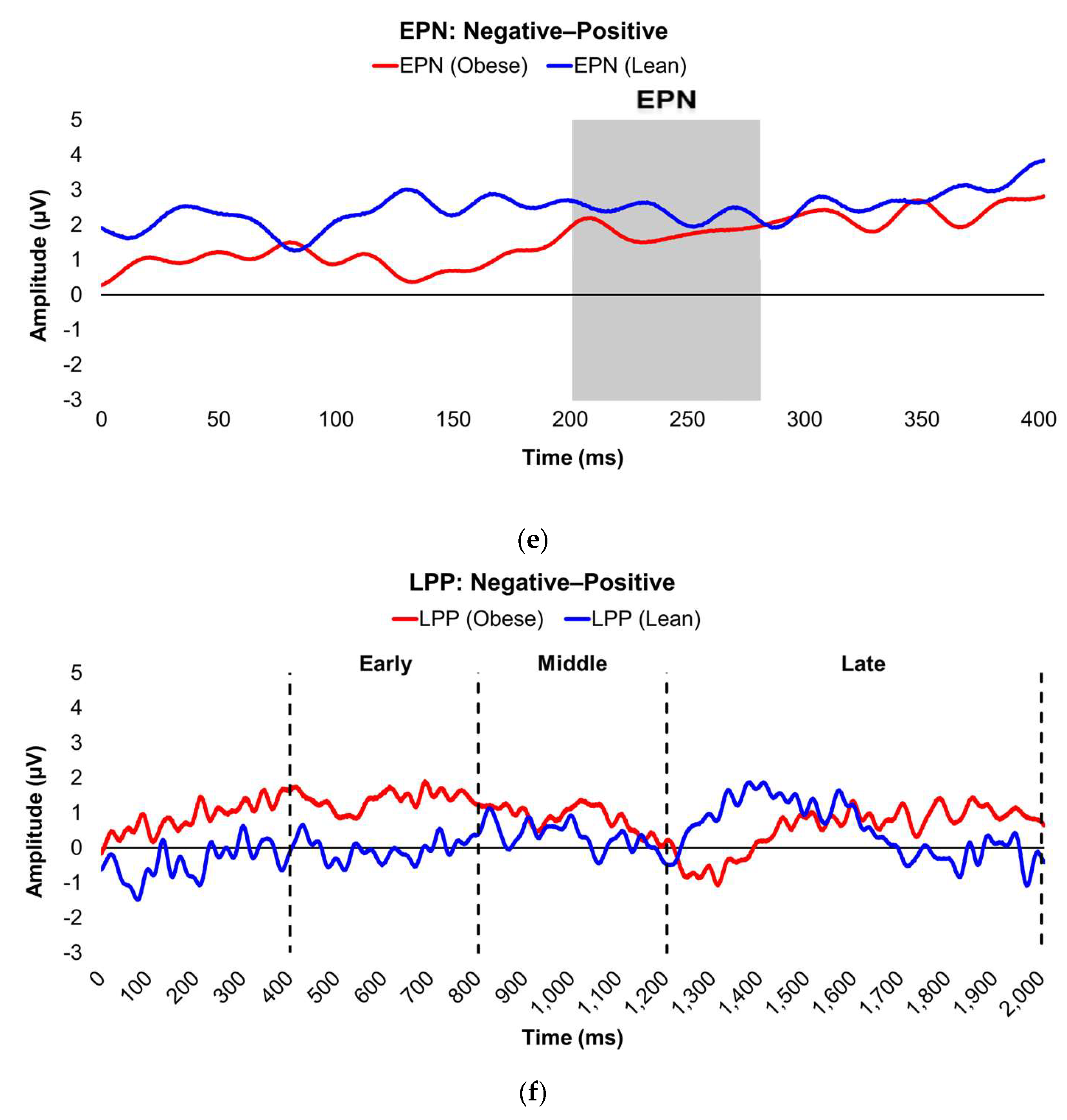

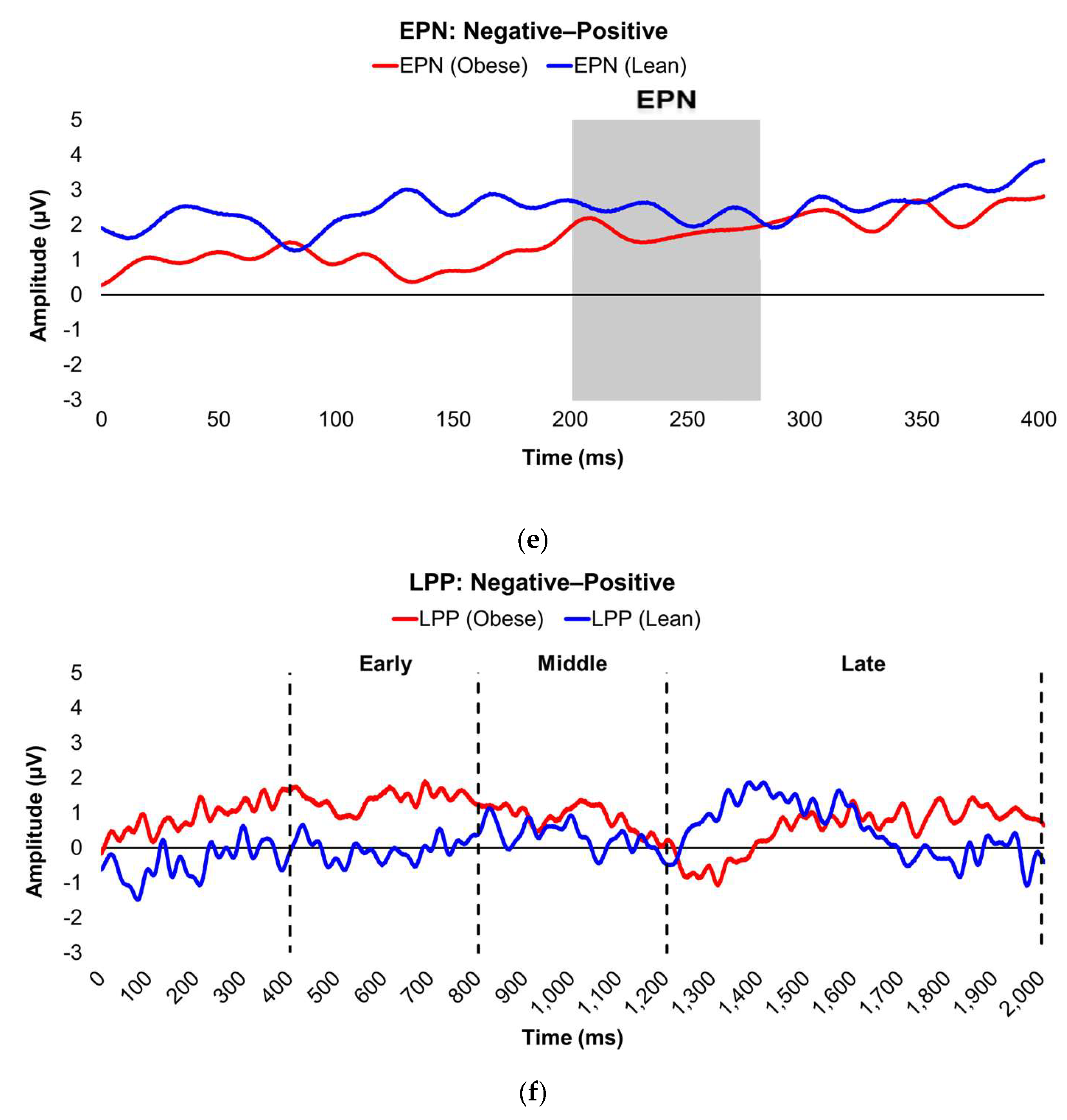

Figure 3.

Line graphs show the comparisons of the differenced grand-mean averaged EPN (left) and LPP (right) waveforms in the contrasted picture conditions (i.e., Negative minus Neutral (a–b), Positive minus Neutral (c–d), and Negative minus Positive (e–f) EPN and LPP waveforms) between insulin-sensitive (HOMA-IR values of <2.0, in blue) versus insulin-resistant (HOMA-IR values of ≥2.0, in red) subjects. Amplitude was measured in microvolts (µV); time was measured in milliseconds. EPN = early posterior negativity; IR = insulin-resistant; IS = insulin-sensitive; LPP = late positive potential; ms = milliseconds. Early, middle, and late latency windows of the LPP component = 400–800 ms, 800–1,200 ms, and 1,200–2,000 ms post-stimulus onset, respectively. For the EPN component, lower difference score values reflect overall larger amplitude deflections in response to the emotionally-valenced condition compared to the Neutrally- or oppositely-valenced condition, whereas higher difference scores indicate overall larger amplitude deflections in response to the emotionally-valenced condition compared to the Neutrally- or oppositely-valenced condition for the LPP component.

Figure 3.

Line graphs show the comparisons of the differenced grand-mean averaged EPN (left) and LPP (right) waveforms in the contrasted picture conditions (i.e., Negative minus Neutral (a–b), Positive minus Neutral (c–d), and Negative minus Positive (e–f) EPN and LPP waveforms) between insulin-sensitive (HOMA-IR values of <2.0, in blue) versus insulin-resistant (HOMA-IR values of ≥2.0, in red) subjects. Amplitude was measured in microvolts (µV); time was measured in milliseconds. EPN = early posterior negativity; IR = insulin-resistant; IS = insulin-sensitive; LPP = late positive potential; ms = milliseconds. Early, middle, and late latency windows of the LPP component = 400–800 ms, 800–1,200 ms, and 1,200–2,000 ms post-stimulus onset, respectively. For the EPN component, lower difference score values reflect overall larger amplitude deflections in response to the emotionally-valenced condition compared to the Neutrally- or oppositely-valenced condition, whereas higher difference scores indicate overall larger amplitude deflections in response to the emotionally-valenced condition compared to the Neutrally- or oppositely-valenced condition for the LPP component.

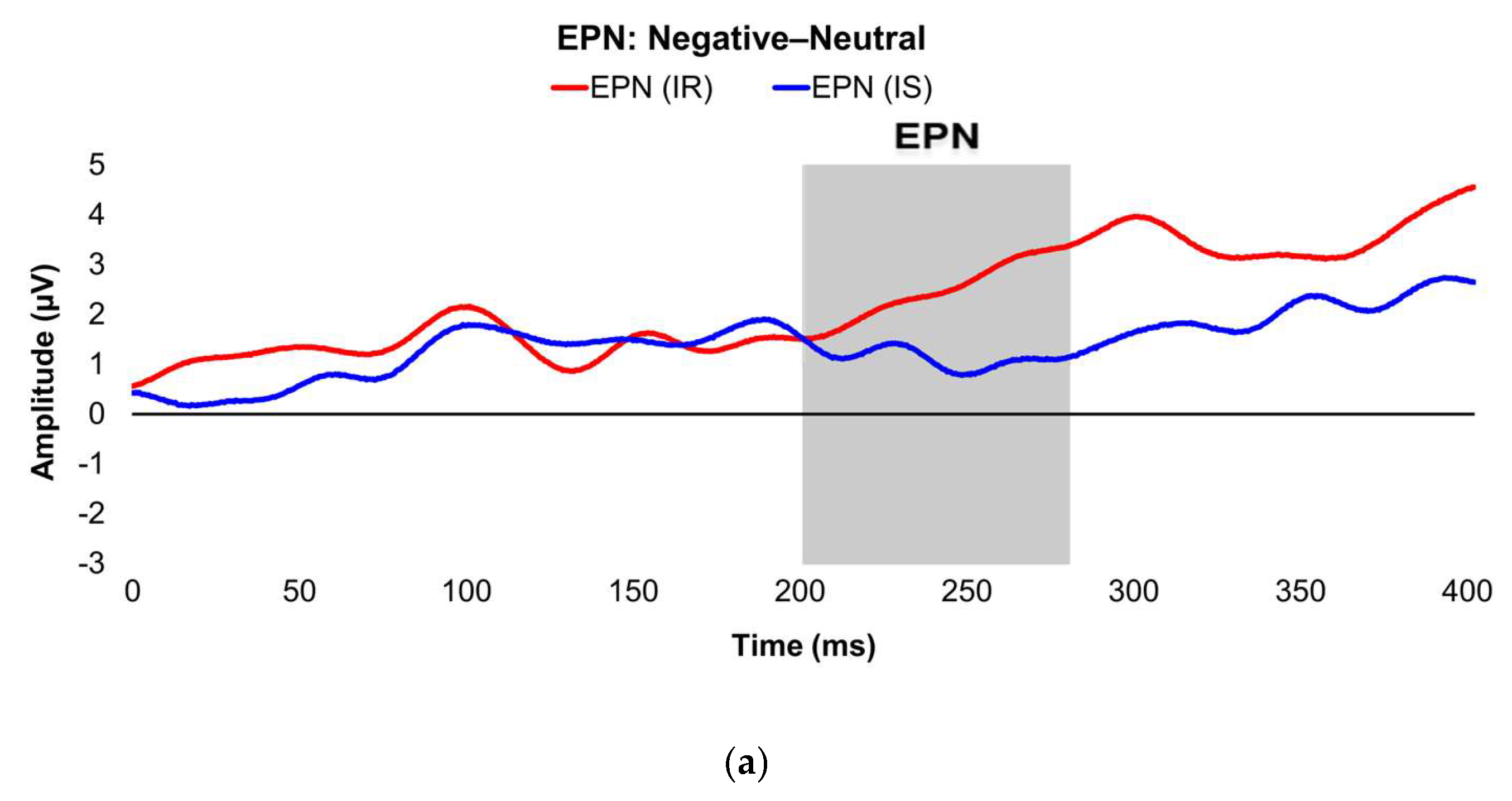

Figure 4.

Interaction plots depict how body fat percentage (a) and HOMA-IR (b) moderated the relationships between the voltage amplitudes of the LPP component during the late latency window and mean valence ratings in the contrasted Negative–Neutral picture condition. Predictor (late-window LPP component voltage amplitudes) and moderator (BF%, HOMA-IR values) variables were tested as continuous variables but are shown as tertiles for visualization. BF% = body fat percentage; HOMA-IR = homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance; LPP = late positive potential; ms = milliseconds. * and *** = p’s≤0.05 and ≤0.005, respectively. Amplitude deflections (lesser, average, greater) and BF% or HOMA-IR levels (low, medium, high) respectively reflect values at the 16th, 50th, and 84th percentiles of the total sample. Valence ratings represent the mean ratings of the magnitude of pleasantness or unpleasantness of images for each valence condition, where 1=“very positive,” 2=“somewhat positive,” 3=“somewhat negative,” and 4=“very negative,” which were subsequently contrasted as the difference between the mean valence ratings of Neutrally-valenced pictures from the mean valence ratings of Negatively-valenced pictures (i.e., Negative minus Neutral valence ratings). For the contrasted valence ratings, larger difference scores for the contrasted Negatively-valenced conditions indicate more unpleasant ratings assigned to the visual stimuli overall. For the LPP component, higher difference scores indicate overall larger amplitude deflections in response to unpleasant pictures compared to neutral pictures. For subjects with low BF% and low-to-medium HOMA-IR values, greater (i.e., more positive) LPP amplitudes during the late latency window were linked to less negative valence ratings in response to unpleasant versus neutral pictures. Early, middle, and late latency windows of the LPP component = 400–800 ms, 800–1,200 ms, and 1,200–2,000 ms, respectively.

Figure 4.

Interaction plots depict how body fat percentage (a) and HOMA-IR (b) moderated the relationships between the voltage amplitudes of the LPP component during the late latency window and mean valence ratings in the contrasted Negative–Neutral picture condition. Predictor (late-window LPP component voltage amplitudes) and moderator (BF%, HOMA-IR values) variables were tested as continuous variables but are shown as tertiles for visualization. BF% = body fat percentage; HOMA-IR = homeostatic model assessment for insulin resistance; LPP = late positive potential; ms = milliseconds. * and *** = p’s≤0.05 and ≤0.005, respectively. Amplitude deflections (lesser, average, greater) and BF% or HOMA-IR levels (low, medium, high) respectively reflect values at the 16th, 50th, and 84th percentiles of the total sample. Valence ratings represent the mean ratings of the magnitude of pleasantness or unpleasantness of images for each valence condition, where 1=“very positive,” 2=“somewhat positive,” 3=“somewhat negative,” and 4=“very negative,” which were subsequently contrasted as the difference between the mean valence ratings of Neutrally-valenced pictures from the mean valence ratings of Negatively-valenced pictures (i.e., Negative minus Neutral valence ratings). For the contrasted valence ratings, larger difference scores for the contrasted Negatively-valenced conditions indicate more unpleasant ratings assigned to the visual stimuli overall. For the LPP component, higher difference scores indicate overall larger amplitude deflections in response to unpleasant pictures compared to neutral pictures. For subjects with low BF% and low-to-medium HOMA-IR values, greater (i.e., more positive) LPP amplitudes during the late latency window were linked to less negative valence ratings in response to unpleasant versus neutral pictures. Early, middle, and late latency windows of the LPP component = 400–800 ms, 800–1,200 ms, and 1,200–2,000 ms, respectively.

Table 1.

Participant characteristic comparisons by adiposity and insulin groups.

Table 1.

Participant characteristic comparisons by adiposity and insulin groups.

| |

Adiposity |

Insulin |

| Data (unit) |

Total (n=30) |

Lean (n=8) |

Obese (n=22) |

t value/Chi-square |

Insulin-sensitive (n=18) |

Insulin-resistant (n=12) |

t value/ Chi-square |

| Age (years) |

25.7 (5.3) |

23.3 (4.1) |

26.5 (5.5) |

t= -1.54 |

24.9 (5.6) |

26.8 (4.9) |

t= -0.98 |

| Sex (n females (%)) |

15 (50.0%) |

3 (37.5%) |

12 (54.5%) |

χ2= 0.68 |

8 (44.4%) |

7 (58.3%) |

χ2= 0.56 |

| Activity Level (n (%)) |

|

|

|

χ2= 4.18 |

|

|

χ2= 5.63* |

| Sedentary/Low Active |

20 (66.7%) |

3 (37.5%) |

17 (77.3%) |

|

9 (50.0%) |

11 (91.7%) |

|

| Active/Very Active |

10 (33.3%) |

5 (62.5%) |

5 (22.7%) |

|

9 (50.0%) |

1 (8.3%) |

|

| Race/Ethnicity (n (%)) |

|

|

|

χ2= 3.62 |

|

|

χ2= 5.17 |

| White |

24 (80.0%) |

5 (62.5%) |

19 (86.4%) |

|

13 (72.2%) |

11 (91.7%) |

|

| Asian |

5 (16.7%) |

3 (37.5%) |

2 (9.1%) |

|

5 (27.8%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

| Hispanic/Latinx |

1 (3.3%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (4.5%) |

|

0 (0.0%) |

1 (8.3%) |

|

| Black |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

| BF% (DEXA) |

37.1 (10.3) |

24.8 (4.7) |

41.6 (7.9) |

t= -5.64***

|

31.6 (8.5) |

45.5 (6.7) |

t= -4.76***

|

| BMI |

29.3 (8.2) |

21.0 (1.6) |

32.2 (7.5) |

t= -6.94***

|

24.5 (5.3) |

36.4 (6.4) |

t= -5.74***

|

| BP, diastolic (kPa) |

10.2 (1.7) |

9.6 (2.0) |

10.5 (1.5) |

t= -1.26 |

9.7 (1.6) |

11.1 (1.4) |

t= -2.33*

|

| BP, systolic (kPa) |

16.2 (2.1) |

16.6 (2.8) |

16.0 (1.7) |

t= 0.68 |

16.0 (2.4) |

16.6 (1.3) |

t= -0.75 |

| Glucose (mmol/L), fasting |

5.0 (0.5) |

4.7 (0.4) |

5.1 (0.4) |

t= -2.38*

|

4.9 (0.5) |

5.2 (0.5) |

t= -1.50 |

| Height (meters) |

1.7 (0.1) |

1.8 (0.1) |

1.7 (0.1) |

t= 0.43 |

1.7 (0.1) |

1.7 (0.1) |

t= -0.37 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) |

5.4 (0.2) |

5.3 (0.1) |

5.4 (0.2) |

t= -1.05 |

5.3 (0.2) |

5.4 (0.2) |

t= -1.36 |

| HOMA-IR |

2.6 (2.5) |

0.9 (0.3) |

3.3 (2.7) |

t= -4.24***

|

1.2 (0.4) |

4.9 (2.8) |

t= -8.07***

|

Table 2.

Comparisons of event-related potentials by adiposity and insulin groups.

Table 2.

Comparisons of event-related potentials by adiposity and insulin groups.

| |

Adiposity |

Insulin |

| ERP Components |

Total |

Lean |

Obese |

t value |

Insulin-sensitive |

Insulin-resistant |

t value |

| Negative–Neutral |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| EPN |

1.7 (2.7) |

1.7 (3.0) |

1.6 (2.6) |

t= 0.04 |

1.1 (2.6) |

2.5 (2.6) |

t= -1.37 |

| Early LPP |

0.9 (1.9) |

0.6 (2.5) |

1.1 (1.7) |

t= -0.64 |

0.8 (2.1) |

1.2 (1.7) |

t= -0.47 |

| Middle LPP |

0.8 (2.2) |

0.6 (2.2) |

0.9 (2.2) |

t= -0.38 |

0.7 (2.1) |

1.1 (2.4) |

t= -0.45 |

| Late LPP |

1.2 (1.8) |

2.4 (2.3) |

0.8 (1.5) |

t= 2.31*

|

1.8 (1.9) |

0.3 (1.3) |

t= 2.37*

|

| Positive–Neutral |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| EPN |

-0.3 (2.6) |

-0.7 (2.1) |

-0.2 (2.8) |

t= -0.49 |

-0.8 (2.5) |

0.4 (2.6) |

t= -1.22 |

| Early LPP |

-0.1 (2.3) |

0.6 (1.7) |

-0.3 (2.5) |

t= 0.96 |

0.0 (2.3) |

-0.2 (2.5) |

t= 0.26 |

| Middle LPP |

0.1 (2.7) |

0.3 (2.0) |

0.1 (2.9) |

t= 0.17 |

0.2 (2.5) |

0.0 (3.1) |

t= 0.13 |

| Late LPP |

0.7 (2.2) |

1.9 (2.1) |

0.3 (2.2) |

t= 1.87 |

1.2 (1.9) |

-0.1 (2.6) |

t= 1.69 |

| Negative–Positive |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| EPN |

2.0 (2.7) |

2.4 (3.1) |

1.8 (2.6) |

t= 0.50 |

1.9 (2.9) |

2.1 (2.5) |

t= -0.18 |

| Early LPP |

1.0 (1.6) |

0.0 (1.6) |

1.4 (1.4) |

t= -2.38*

|

0.8 (1.7) |

1.3 (1.4) |

t= -0.97 |

| Middle LPP |

0.7 (2.0) |

0.3 (1.2) |

0.9 (2.2) |

t= -0.65 |

0.5 (1.9) |

1.0 (2.2) |

t= -0.68 |

| Late LPP |

0.5 (2.0) |

0.5 (2.0) |

0.5 (2.0) |

t= 0.03 |

0.6 (2.0) |

0.4 (2.0) |

t= 0.19 |

Table 3.

Comparisons of affective processing task scores by adiposity and insulin groups.

Table 3.

Comparisons of affective processing task scores by adiposity and insulin groups.

| |

Adiposity |

Insulin |

| Affective Processing Parameters |

Total |

Lean |

Obese |

t value |

Insulin Sensitive |

Insulin Resistant |

t value |

| Rating (Negative–Neutral) |

1.6 (0.4) |

1.5 (0.5) |

1.6 (0.3) |

t= -0.37 |

1.6 (0.4) |

1.5 (0.3) |

t= 0.57 |

| RT (Negative–Neutral) |

2.6 (206.1) |

-1.3 (154.2) |

4.0 (225.2) |

t= -0.06 |

-59.0 (182.9) |

95.0 (211.6) |

t= -2.12*

|

| Rating (Positive–Neutral) |

-0.4 (0.2) |

-0.5 (0.2) |

-0.4 (0.2) |

t= -1.26 |

-0.5 (0.2) |

-0.3 (0.2) |

t= -0.91 |

| RT (Positive–Neutral) |

25.5 (174.4) |

58.9 (213.0) |

13.4 (162.2) |

t= 0.63 |

7.8 (213.8) |

52.1 (91.1) |

t= -0.78 |

| Rating (Negative–Positive) |

2.7 (0.2) |

2.5 (0.3) |

2.7 (0.2) |

t= -2.39*

|

2.6 (0.2) |

2.8 (0.2) |

t= -1.64 |

| RT (Negative–Positive) |

-17.8 (216.8) |

-30.8 (156.0) |

-13.0 (238.2) |

t= -0.20 |

-53.7 (184.3) |

36.2 (257.3) |

t= -1.12 |

Table 4.

Correlation matrix of event-related potentials and affective processing parameters.

Table 4.

Correlation matrix of event-related potentials and affective processing parameters.

| |

Negative–Neutral |

Positive–Neutral |

Negative–Positive |

| ERP Components |

Valence Rating |

Reaction Time |

Valence Rating |

Reaction Time |

Valence Rating |

Reaction Time |

| Negative–Neutral |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| EPN |

-0.15 |

0.11 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Early LPP |

0.08 |

0.08 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Middle LPP |

-0.01 |

0.16 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Late LPP |

-0.36 |

0.06 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Positive–Neutral |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| EPN |

- |

- |

-0.27 |

0.15 |

- |

- |

| Early LPP |

- |

- |

-0.06 |

0.09 |

- |

- |

| Middle LPP |

- |

- |

-0.04 |

0.14 |

- |

- |

| Late LPP |

- |

- |

-0.31 |

0.01 |

- |

- |

| Negative–Positive |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| EPN |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.19 |

-0.38* |

| Early LPP |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.28 |

-0.19 |

| Middle LPP |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.31 |

-0.08 |

| Late LPP |

- |

- |

- |

- |

-0.08 |

-0.15 |

Table 5.

Hierarchical moderated regression results for Negative vs. Neutral valence ratings.

Table 5.

Hierarchical moderated regression results for Negative vs. Neutral valence ratings.

| |

Step 1 |

|

Step 2 |

| Variables |

β |

t |

R2 |

F |

p |

|

β |

t |

ΔR2 |

ΔF |

p |

| Model 1 |

|

|

0.03 |

0.47 |

0.63 |

|

|

|

0.03 |

0.30 |

0.82 |

| EPN |

-0.15 |

-0.79 |

|

|

|

|

-0.15 |

-0.78 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

0.10 |

0.53 |

|

|

|

|

0.10 |

0.52 |

|

|

|

| EPN*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.02 |

0.10 |

0.00 |

0.01 |

0.92 |

| Model 2 |

|

|

0.02 |

0.33 |

0.73 |

|

|

|

0.02 |

0.21 |

0.89 |

| EPN |

-0.15 |

-0.81 |

|

|

|

|

-0.15 |

-0.77 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

-0.01 |

-0.06 |

|

|

|

|

-0.01 |

-0.07 |

|

|

|

| EPN*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.02 |

0.09 |

0.00 |

0.01 |

0.93 |

| Model 3 |

|

|

0.02 |

0.28 |

0.76 |

|

|

|

0.03 |

0.24 |

0.87 |

| eLPP |

0.10 |

0.51 |

|

|

|

|

0.11 |

0.57 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

0.12 |

0.62 |

|

|

|

|

0.13 |

0.67 |

|

|

|

| eLPP*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.08 |

0.40 |

0.00 |

0.16 |

0.69 |

| Model 4 |

|

|

0.01 |

0.09 |

0.91 |

|

|

|

0.01 |

0.10 |

0.96 |

| eLPP |

0.08 |

0.43 |

|

|

|

|

0.09 |

0.46 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

0.00 |

-0.01 |

|

|

|

|

-0.01 |

-0.05 |

|

|

|

| eLPP*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.07 |

0.36 |

0.01 |

0.13 |

0.73 |

| Model 5 |

|

|

0.01 |

0.16 |

0.86 |

|

|

|

0.06 |

0.53 |

0.66 |

| mLPP |

-0.02 |

-0.10 |

|

|

|

|

0.00 |

0.01 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

0.11 |

0.56 |

|

|

|

|

0.15 |

0.76 |

|

|

|

| mLPP*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.22 |

1.13 |

0.05 |

1.28 |

0.27 |

| Model 6 |

|

|

0.00 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

0.06 |

0.55 |

0.65 |

| mLPP |

-0.01 |

-0.06 |

|

|

|

|

-0.04 |

-0.21 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

0.01 |

0.03 |

|

|

|

|

-0.09 |

-0.42 |

|

|

|

| mLPP*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.26 |

1.29 |

0.06 |

1.65 |

0.21 |

| Model 7 |

|

|

0.13 |

2.06 |

0.15 |

|

|

|

0.38** |

5.25** |

0.006 |

| lLPP |

-0.38 |

-1.94 |

|

|

|

|

-0.05 |

-0.24 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

-0.06 |

-0.28 |

|

|

|

|

-0.08 |

-0.46 |

|

|

|

| lLPP*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.60*** |

3.20*** |

0.24*** |

10.23*** |

0.004 |

| Model 8 |

|

|

0.14 |

2.20 |

0.13 |

|

|

|

0.38** |

5.29** |

0.006 |

| lLPP |

-0.40 |

-2.12 |

|

|

|

|

-0.20 |

-1.18 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

-0.12 |

-0.63 |

|

|

|

|

-0.11 |

-0.69 |

|

|

|

| lLPP*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.52*** |

3.14*** |

0.24*** |

9.89*** |

0.004 |

Table 6.

Hierarchical moderated regression results for Negative vs. Neutral reaction times.

Table 6.

Hierarchical moderated regression results for Negative vs. Neutral reaction times.

| |

Step 1 |

|

Step 2 |

| Variables |

β |

t |

R2 |

F |

p |

|

β |

t |

ΔR2 |

ΔF |

p |

| Model 1 |

|

|

0.14 |

1.38 |

0.27 |

|

|

|

0.16 |

1.17 |

0.35 |

| EPN |

0.10 |

0.56 |

|

|

|

|

0.12 |

0.64 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

0.02 |

0.09 |

|

|

|

|

0.02 |

0.10 |

|

|

|

| Age |

0.35 |

1.90 |

|

|

|

|

0.36 |

1.95 |

|

|

|

| EPN*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

-0.15 |

-0.78 |

0.02 |

0.61 |

0.44 |

| Model 2 |

|

|

0.15 |

2.37 |

0.11 |

|

|

|

0.25 |

2.05 |

0.12 |

| EPN |

0.15 |

0.85 |

|

|

|

|

0.11 |

0.63 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

0.37 |

2.08 |

|

|

|

|

0.32 |

1.76 |

|

|

|

| Age |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0.32 |

1.73 |

|

|

|

| EPN*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

-0.16 |

-0.86 |

0.02 |

0.75 |

0.40 |

| Model 3 |

|

|

0.16 |

1.65 |

0.20 |

|

|

|

0.16 |

1.19 |

0.34 |

| eLPP |

0.19 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

|

0.18 |

0.93 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

0.03 |

0.16 |

|

|

|

|

0.02 |

0.13 |

|

|

|

| Age |

0.40 |

2.14 |

|

|

|

|

0.40 |

2.10 |

|

|

|

| eLPP*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

-0.02 |

-0.12 |

0.00 |

0.01 |

0.91 |

| Model 4 |

|

|

0.32 |

2.91 |

0.04 |

|

|

|

0.32 |

2.91 |

0.04 |

| eLPP |

0.11 |

0.61 |

|

|

|

|

0.12 |

0.69 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

0.38 |

2.09 |

|

|

|

|

0.30 |

1.75 |

|

|

|

| Age |

0.32 |

1.79 |

|

|

|

|

0.36 |

2.02 |

|

|

|

| Race/Ethnicity |

0.32 |

1.83 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| eLPP*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

-0.31 |

-1.84 |

0.09 |

3.38 |

0.08 |

| Model 5 |

|

|

0.18 |

1.93 |

0.15 |

|

|

|

0.19 |

1.42 |

0.26 |

| mLPP |

0.24 |

1.32 |

|

|

|

|

0.23 |

1.26 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

-0.01 |

-0.07 |

|

|

|

|

-0.02 |

-0.13 |

|

|

|

| Age |

0.41 |

2.21 |

|

|

|

|

0.41 |

2.19 |

|

|

|

| mLPP*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

-0.06 |

-0.33 |

0.00 |

0.11 |

0.74 |

| Model 6 |

|

|

0.34 |

3.22 |

0.03 |

|

|

|

0.38 |

2.88 |

0.04 |

| mLPP |

0.19 |

1.11 |

|

|

|

|

0.22 |

1.30 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

0.37 |

2.05 |

|

|

|

|

0.42 |

2.29 |

|

|

|

| Age |

0.33 |

1.92 |

|

|

|

|

0.38 |

2.15 |

|

|

|

| Race/Ethnicity |

0.33 |

1.93 |

|

|

|

|

0.31 |

1.81 |

|

|

|

| mLPP*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

-0.21 |

-1.17 |

0.04 |

1.36 |

0.26 |

| Model 7 |

|

|

0.24 |

1.95 |

0.13 |

|

|

|

0.36 |

2.74 |

0.04 |

| lLPP |

0.31 |

1.42 |

|

|

|

|

0.09 |

0.40 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

0.25 |

1.13 |

|

|

|

|

0.28 |

1.39 |

|

|

|

| Age |

0.37 |

2.11 |

|

|

|

|

0.39 |

2.34 |

|

|

|

| Race/Ethnicity |

0.37 |

1.79 |

|

|

|

|

0.42 |

2.15 |

|

|

|

| lLPP*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

-0.44 |

-2.18 |

0.13 |

4.75 |

0.04 |

| Model 8 |

|

|

0.44*** |

4.92*** |

0.005 |

|

|

|

0.56*** |

6.04*** |

<0.001 |

| lLPP |

0.43 |

2.44 |

|

|

|

|

0.28 |

1.63 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

0.59*** |

3.28*** |

|

|

|

|

0.58*** |

3.52*** |

|

|

|

| Age |

0.29 |

1.91 |

|

|

|

|

0.28 |

2.02 |

|

|

|

| Race/Ethnicity |

0.52 |

2.97 |

|

|

|

|

0.49** |

3.07** |

|

|

|

| lLPP*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

|

-0.37 |

-2.52 |

0.12 |

6.33 |

0.02 |

Table 7.

Hierarchical moderated regression results for Positive vs. Neutral valence ratings.

Table 7.

Hierarchical moderated regression results for Positive vs. Neutral valence ratings.

| |

Step 1 |

Step 2 |

| Variables |

β |

t |

R2 |

F |

p |

β |

t |

ΔR2 |

ΔF |

p |

| Model 1 |

|

|

0.44*** |

6.82*** |

0.002 |

|

|

0.44*** |

4.99*** |

0.004 |

| EPN |

-0.27 |

-1.85 |

|

|

|

-0.29 |

-1.87 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

0.32 |

2.11 |

|

|

|

0.32 |

2.05 |

|

|

|

| Race/Ethnicity |

0.62*** |

4.02*** |

|

|

|

0.61*** |

3.91*** |

|

|

|

| EPN*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

0.06 |

0.41 |

0.00 |

0.17 |

0.68 |

| Model 2 |

|

|

0.41*** |

6.03*** |

0.003 |

|

|

0.41 |

4.38 |

0.008 |

| EPN |

-0.32 |

-2.10 |

|

|

|

-0.32 |

-2.07 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

0.27 |

1.70 |

|

|

|

0.27 |

1.66 |

|

|

|

| Race/Ethnicity |

0.61*** |

3.84*** |

|

|

|

0.61*** |

3.72*** |

|

|

|

| EPN*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

0.04 |

0.29 |

0.00 |

0.08 |

0.78 |

| Model 3 |

|

|

0.45*** |

5.09*** |

0.004 |

|

|

0.45 |

3.91 |

0.01 |

| eLPP |

-0.15 |

-0.93 |

|

|

|

-0.15 |

-0.86 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

0.32 |

1.99 |

|

|

|

0.32 |

1.94 |

|

|

|

| Age |

-0.28 |

-1.85 |

|

|

|

-0.28 |

-1.82 |

|

|

|

| Race/Ethnicity |

0.62*** |

3.99*** |

|

|

|

0.62*** |

3.91*** |

|

|

|

| eLPP*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

0.00 |

-0.01 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.99 |

| Model 4 |

|

|

0.43** |

4.65** |

0.006 |

|

|

0.43 |

3.57 |

0.02 |

| eLPP |

-0.23 |

-1.46 |

|

|

|

-0.23 |

-1.39 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

0.28 |

1.68 |

|

|

|

0.28 |

1.64 |

|

|

|

| Age |

-0.32 |

-2.00 |

|

|

|

-0.32 |

-1.96 |

|

|

|

| Race/Ethnicity |

0.64*** |

3.90*** |

|

|

|

0.64*** |

3.81*** |

|

|

|

| eLPP*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

0.01 |

0.04 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.97 |

| Model 5 |

|

|

0.45*** |

5.01*** |

0.004 |

|

|

0.46 |

4.01 |

0.009 |

| mLPP |

-0.12 |

-0.81 |

|

|

|

0.04 |

0.23 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

0.35 |

2.24 |

|

|

|

0.51 |

2.55 |

|

|

|

| Age |

-0.27 |

-1.78 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Race/Ethnicity |

0.62*** |

3.97*** |

|

|

|

0.67*** |

4.13*** |

|

|

|

| Physical Activity |

|

|

|

|

|

0.36 |

1.81 |

|

|

|

| mLPP*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.17 |

-1.00 |

0.02 |

1.00 |

0.33 |

| Model 6 |

|

|

0.32 |

4.11 |

0.02 |

|

|

0.48 |

3.48 |

0.01 |

| mLPP |

-0.17 |

-1.10 |

|

|

|

0.03 |

0.17 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

0.29 |

1.76 |

|

|

|

0.46 |

2.32 |

|

|

|

| Age |

-0.29 |

-1.83 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Race/Ethnicity |

0.62*** |

3.77*** |

|

|

|

0.76*** |

4.24*** |

|

|

|

| Physical Activity |

|

|

|

|

|

0.39 |

1.94 |

|

|

|

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.33 |

-1.91 |

|

|

|

| mLPP*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.25 |

-1.44 |

0.05 |

2.08 |

0.16 |

| Model 7 |

|

|

0.54*** |

5.59*** |

0.001 |

|

|

0.54*** |

4.56*** |

0.004 |

| lLPP |

-0.29 |

-1.76 |

|

|

|

-0.31 |

-1.81 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

0.42 |

2.25 |

|

|

|

0.39 |

1.99 |

|

|

|

| Age |

-0.29 |

-1.94 |

|

|

|

-0.28 |

-1.85 |

|

|

|

| Physical Activity |

0.30 |

1.76 |

|

|

|

0.32 |

1.79 |

|

|

|

| Race/Ethnicity |

0.61*** |

4.00*** |

|

|

|

0.59*** |

3.72*** |

|

|

|

| lLPP*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

0.08 |

0.52 |

0.01 |

0.27 |

0.61 |

| Model 8 |

|

|

0.47*** |

5.46*** |

0.003 |

|

|

0.47 |

4.24 |

0.007 |

| lLPP |

-0.32 |

-2.03 |

|

|

|

-0.30 |

-1.80 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

0.21 |

1.30 |

|

|

|

0.22 |

1.32 |

|

|

|

| Age |

-0.35 |

-2.24 |

|

|

|

-0.35 |

-2.22 |

|

|

|

| Race/Ethnicity |

0.54*** |

3.44*** |

|

|

|

0.54*** |

3.39*** |

|

|

|

| lLPP*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.05 |

-0.35 |

0.00 |

0.12 |

0.73 |

Table 8.

Hierarchical moderated regression results for Positive vs. Neutral reaction times.

Table 8.

Hierarchical moderated regression results for Positive vs. Neutral reaction times.

| |

Step 1 |

Step 2 |

| Variables |

β |

t |

R2 |

F |

p |

β |

t |

ΔR2 |

ΔF |

p |

| Model 1 |

|

|

0.04 |

0.39 |

0.76 |

|

|

0.10 |

0.96 |

0.43 |

| EPN |

0.15 |

0.77 |

|

|

|

0.21 |

1.08 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

-0.09 |

-0.47 |

|

|

|

-0.08 |

-0.44 |

|

|

|

| EPN*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.27 |

-1.41 |

0.07 |

2.00 |

0.17 |

| Model 2 |

|

|

0.03 |

0.37 |

0.70 |

|

|

0.04 |

0.37 |

0.78 |

| EPN |

0.16 |

0.82 |

|

|

|

0.16 |

0.84 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

-0.07 |

-0.36 |

|

|

|

-0.07 |

-0.35 |

|

|

|

| EPN*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.12 |

-0.62 |

0.01 |

0.38 |

0.54 |

| Model 3 |

|

|

0.01 |

0.18 |

0.84 |

|

|

0.01 |

0.12 |

0.95 |

| eLPP |

0.07 |

0.33 |

|

|

|

0.06 |

0.28 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

-0.07 |

-0.35 |

|

|

|

-0.07 |

-0.35 |

|

|

|

| eLPP*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

0.02 |

0.09 |

0.00 |

0.01 |

0.93 |

| Model 4 |

|

|

0.01 |

0.13 |

0.88 |

|

|

0.03 |

0.22 |

0.88 |

| eLPP |

0.09 |

0.44 |

|

|

|

0.12 |

0.58 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

-0.03 |

-0.18 |

|

|

|

-0.04 |

-0.23 |

|

|

|

| eLPP*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.13 |

-0.65 |

0.02 |

0.42 |

0.53 |

| Model 5 |

|

|

0.03 |

0.35 |

0.71 |

|

|

0.04 |

0.32 |

0.81 |

| mLPP |

0.13 |

0.67 |

|

|

|

0.16 |

0.79 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

-0.07 |

-0.39 |

|

|

|

-0.10 |

-0.48 |

|

|

|

| mLPP*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.11 |

-0.52 |

0.01 |

0.27 |

0.61 |

| Model 6 |

|

|

0.02 |

0.30 |

0.74 |

|

|

0.07 |

0.62 |

0.61 |

| mLPP |

0.14 |

0.73 |

|

|

|

0.21 |

1.06 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

-0.04 |

-0.22 |

|

|

|

0.00 |

0.00 |

|

|

|

| mLPP*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.23 |

-1.12 |

0.05 |

1.26 |

0.27 |

| Model 7 |

|

|

0.01 |

0.13 |

0.86 |

|

|

0.02 |

0.13 |

0.94 |

| lLPP |

-0.03 |

-0.16 |

|

|

|

-0.05 |

-0.23 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

-0.11 |

-0.51 |

|

|

|

-0.13 |

-0.60 |

|

|

|

| lLPP*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

0.08 |

0.38 |

0.01 |

0.14 |

0.71 |

| Model 8 |

|

|

0.00 |

0.03 |

0.97 |

|

|

0.01 |

0.08 |

0.97 |

| lLPP |

0.00 |

0.00 |

|

|

|

0.03 |

0.14 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

-0.05 |

-0.24 |

|

|

|

-0.03 |

-0.17 |

|

|

|

| lLPP*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.09 |

-0.42 |

0.01 |

0.18 |

0.67 |

Table 9.

Hierarchical moderated regression results for Negative vs. Positive valence ratings.

Table 9.

Hierarchical moderated regression results for Negative vs. Positive valence ratings.

| |

Step 1 |

Step 2 |

| Variables |

β |

t |

R2 |

F |

p |

β |

t |

ΔR2 |

ΔF |

p |

| Model 1 |

|

|

0.41*** |

5.96*** |

0.003 |

|

|

0.43** |

4.74** |

0.006 |

| EPN |

0.34 |

2.09 |

|

|

|

0.30 |

1.84 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

0.35 |

2.23 |

|

|

|

0.37 |

2.33 |

|

|

|

| Race/Ethnicity |

-0.42 |

-2.51 |

|

|

|

-0.36 |

-1.98 |

|

|

|

| EPN*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

0.17 |

1.02 |

0.02 |

1.04 |

0.32 |

| Model 2 |

|

|

0.35 |

4.68 |

0.01 |

|

|

0.40 |

4.20 |

0.01 |

| EPN |

0.41 |

2.41 |

|

|

|

0.46 |

2.71 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

0.25 |

1.51 |

|

|

|

0.25 |

1.54 |

|

|

|

| Race/Ethnicity |

-0.47 |

-2.67 |

|

|

|

-0.40 |

-2.29 |

|

|

|

| EPN*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

0.25 |

1.47 |

0.05 |

2.15 |

0.16 |

| Model 3 |

|

|

0.32 |

4.07 |

0.02 |

|

|

0.24 |

2.77 |

0.06 |

| eLPP |

0.12 |

0.68 |

|

|

|

0.14 |

0.74 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

0.61** |

3.02** |

|

|

|

0.43 |

2.36 |

|

|

|

| Physical Activity |

0.33 |

1.72 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| eLPP*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

0.02 |

0.13 |

0.00 |

0.02 |

0.89 |

| Model 4 |

|

|

0.26 |

3.04 |

0.05 |

|

|

0.27 |

2.36 |

0.08 |

| eLPP |

0.15 |

0.83 |

|

|

|

0.10 |

0.52 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

0.22 |

1.24 |

|

|

|

0.28 |

1.40 |

|

|

|

| Sex |

-0.36 |

-2.08 |

|

|

|

-0.38 |

-2.14 |

|

|

|

| eLPP*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.14 |

-0.71 |

0.01 |

0.50 |

0.49 |

| Model 5 |

|

|

0.03 |

0.12 |

0.99 |

|

|

0.31 |

3.97 |

0.02 |

| mLPP |

0.18 |

1.07 |

|

|

|

0.17 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

0.60** |

3.06** |

|

|

|

0.38 |

2.23 |

|

|

|

| Physical Activity |

0.33 |

1.75 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| mLPP*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

0.24 |

1.45 |

0.06 |

2.11 |

0.16 |

| Model 6 |

|

|

0.27 |

3.25 |

0.04 |

|

|

0.27 |

2.37 |

0.80 |

| mLPP |

0.19 |

1.09 |

|

|

|

0.18 |

0.97 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

0.24 |

1.38 |

|

|

|

0.22 |

1.23 |

|

|

|

| Sex |

-0.34 |

-1.95 |

|

|

|

-0.34 |

-1.93 |

|

|

|

| mLPP*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

0.05 |

0.26 |

0.00 |

0.07 |

0.80 |

| Model 7 |

|

|

0.33 |

4.33 |

0.01 |

|

|

0.46*** |

5.29*** |

0.003 |

| lLPP |

-0.16 |

-1.00 |

|

|

|

-0.16 |

-1.05 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

0.39 |

2.34 |

|

|

|

0.39 |

2.51 |

|

|

|

| Race/Ethnicity |

-0.33 |

-1.92 |

|

|

|

-0.36 |

-2.27 |

|

|

|

| lLPP*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

0.35 |

2.40 |

0.13 |

5.77 |

0.02 |

| Model 8 |

|

|

0.24 |

2.78 |

0.06 |

|

|

0.26 |

2.21 |

0.10 |

| lLPP |

-0.05 |

-0.32 |

|

|

|

-0.15 |

-0.86 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

0.26 |

1.53 |

|

|

|

0.18 |

1.00 |

|

|

|

| Sex |

-0.38 |

-2.18 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Race/Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.39 |

-2.11 |

|

|

|

| lLPP*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

0.19 |

1.13 |

0.04 |

1.27 |

0.27 |

Table 10.

Hierarchical moderated regression results for Negative vs. Positive reaction times.

Table 10.

Hierarchical moderated regression results for Negative vs. Positive reaction times.

| |

Step 1 |

Step 2 |

| Variables |

β |

t |

R2 |

F |

p |

β |

t |

ΔR2 |

ΔF |

p |

| Model 1 |

|

|

0.36 |

3.52 |

0.02 |

|

|

0.29 |

2.50 |

0.07 |

| EPN |

-0.48 |

-2.82 |

|

|

|

-0.35 |

-2.05 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

0.13 |

0.77 |

|

|

|

0.02 |

0.14 |

|

|

|

| Age |

0.33 |

2.04 |

|

|

|

0.36 |

2.06 |

|

|

|

| Race/Ethnicity |

0.36 |

1.98 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| EPN*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.16 |

-0.94 |

0.03 |

0.89 |

0.36 |

| Model 2 |

|

|

0.41 |

4.30 |

0.01 |

|

|

0.41 |

3.36 |

0.02 |

| EPN |

-0.44 |

-2.64 |

|

|

|

-0.45 |

-2.63 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

0.27 |

1.62 |

|

|

|

0.27 |

1.56 |

|

|

|

| Age |

0.29 |

1.84 |

|

|

|

0.31 |

1.86 |

|

|

|

| Race/Ethnicity |

0.39 |

2.28 |

|

|

|

0.37 |

2.06 |

|

|

|

| EPN*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

-0.07 |

-0.41 |

0.00 |

0.17 |

0.68 |

| Model 3 |

|

|

0.18 |

1.94 |

0.15 |

|

|

0.20 |

1.52 |

0.23 |

| eLPP |

-0.25 |

-1.31 |

|

|

|

-0.23 |

-1.18 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

0.11 |

0.59 |

|

|

|

0.13 |

0.67 |

|

|

|

| Age |

0.35 |

1.97 |

|

|

|

0.33 |

1.75 |

|

|

|

| eLPP*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

0.12 |

0.62 |

0.01 |

0.38 |

0.54 |

| Model 4 |

|

|

0.27 |

3.24 |

0.04 |

|

|

0.22 |

2.49 |

0.08 |

| eLPP |

-0.31 |

-1.78 |

|

|

|

-0.25 |

-1.32 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

0.34 |

1.89 |

|

|

|

0.33 |

1.63 |

|

|

|

| Age |

0.29 |

1.71 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| eLPP*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

0.20 |

1.05 |

0.03 |

1.10 |

0.30 |

| Model 5 |

|

|

0.14 |

1.37 |

0.27 |

|

|

0.14 |

0.99 |

0.43 |

| mLPP |

-0.09 |

-0.48 |

|

|

|

-0.09 |

-0.48 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

0.05 |

0.28 |

|

|

|

0.05 |

0.26 |

|

|

|

| Age |

0.35 |

1.89 |

|

|

|

0.35 |

1.81 |

|

|

|

| mLPP*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

0.01 |

0.07 |

0.00 |

0.01 |

0.94 |

| Model 6 |

|

|

0.12 |

1.78 |

0.19 |

|

|

0.19 |

2.03 |

0.14 |

| mLPP |

-0.14 |

-0.78 |

|

|

|

-0.21 |

-1.12 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

0.34 |

1.83 |

|

|

|

0.26 |

1.41 |

|

|

|

| mLPP*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

0.29 |

1.53 |

0.07 |

2.35 |

0.14 |

| Model 7 |

|

|

0.19 |

2.00 |

0.14 |

|

|

0.20 |

1.53 |

0.22 |

| lLPP |

-0.25 |

-1.37 |

|

|

|

-0.24 |

-1.30 |

|

|

|

| BF% |

0.03 |

0.19 |

|

|

|

0.04 |

0.21 |

|

|

|

| Age |

0.41 |

2.25 |

|

|

|

0.39 |

2.02 |

|

|

|

| lLPP*BF% |

|

|

|

|

|

0.10 |

0.52 |

0.01 |

0.27 |

0.61 |

| Model 8 |

|

|

0.23 |

2.63 |

0.07 |

|

|

0.24 |

2.00 |

0.13 |

| lLPP |

-0.23 |

-1.29 |

|

|

|

-0.23 |

-1.27 |

|

|

|

| HOMA-IR |

0.22 |

1.25 |

|

|

|

0.23 |

1.25 |

|

|

|

| Age |

0.36 |

1.99 |

|

|

|

0.35 |

1.85 |

|

|

|

| lLPP*HOMA-IR |

|

|

|

|

|

0.10 |

0.58 |

0.01 |

0.33 |

0.57 |