Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Central Problem: Civilizational Nihilism from a Capped Lifespan

2.1. The Psychology of Temporal Myopia and Short-Termism

2.2. Consumerist Nihilism and the Erosion of Meaning

2.3. Demographic Apathy and the Intellectual Drain

| Pathology | Manifestation | Key References |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Myopia & Short-Termism | Quarterly profits, short political cycles, devaluation of long-term infrastructure and research. | Sandeep & Gopesh, 2017; Jacobs, 2016; Peters & Büchel, 2011 |

| Consumerist Nihilism | Materialism, hedonic treadmill, erosion of intergenerational meaning and projects. | Kasser & Sheldon, 2000; Brown & Kasser, 2005; Diener et al., 2006 |

| Demographic Apathy & Intellectual Drain | Sub-replacement fertility, negative correlation between cognitive ability and reproduction. | Vollset et al., 2020; Beauchamp, 2016; Kanazawa, 2014; Lynn & Harvey, 2008 |

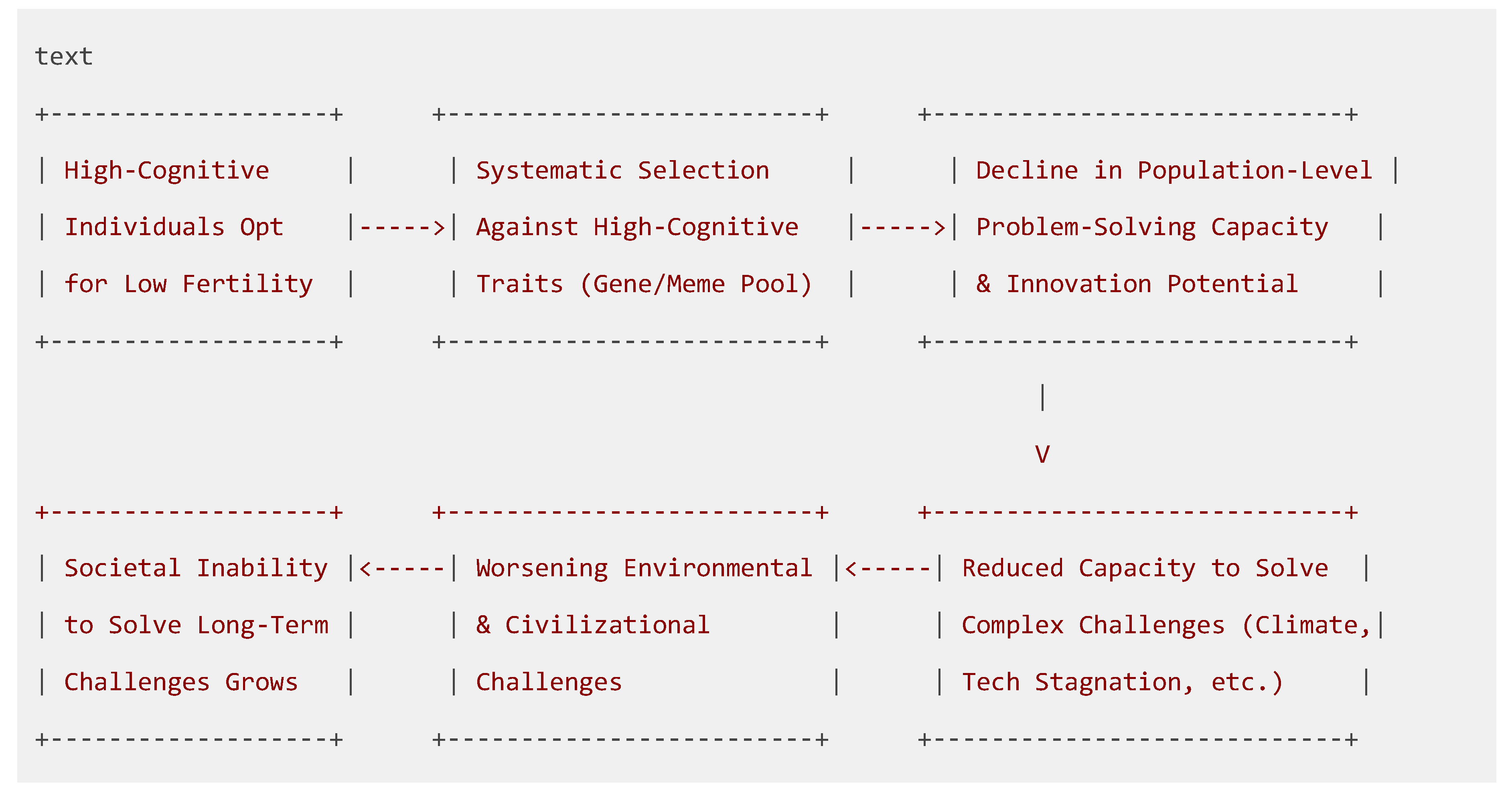

3. The Mechanism of Intellectual Decline: Dysgenic Reproduction Patterns

3.1. Empirical Evidence for the Negative Correlation

3.2. The Causal Nexus

- Opportunity Cost: The high cost of pausing a demanding career for child-rearing (Hose et al., 2020; Balgopal, 2016).

- Existential Risk Awareness: Ethical concerns about overpopulation and environmental crises (Kellstedt et al., 2008).

- Delayed Gratification & Hyper-Agency: The trait of long-term planning paradoxically leads to delaying reproduction beyond the biological window (Shamosh & Gray, 2008; Balbo et al., 2013).

- Genetic Confound: Polygenic scores for educational attainment are negatively correlated with fertility, suggesting selective pressure against cognitive traits (Beauchamp, 2016; Conley, 2016).

3.3. The Long-Term Recursive Drain

4. The Biotechnological Intervention: A Strategy of Continuous Rejuvenation

4.1. The Scientific Premise: Stem Cell Exhaustion

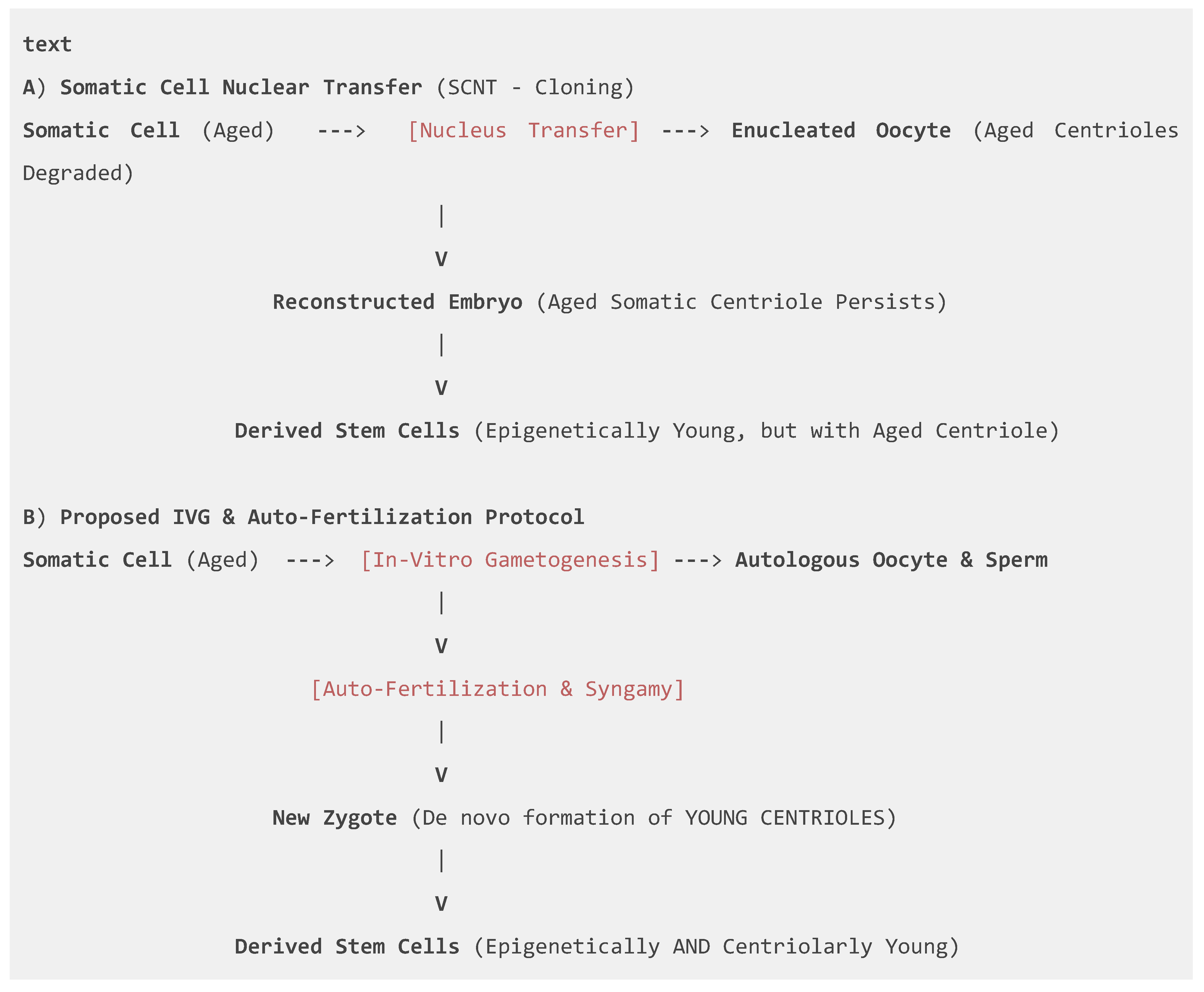

4.2. The Protocol: In-Vitro Gametogenesis (IVG) and Auto-Fertilization

- Advantage over SCNT (Cloning): Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer (Wilmut et al., 1997) fails to reset the aged centriole from the donor somatic cell, carrying forward age-related defects (Simerly et al., 2003). Our IVG-based protocol recapitulates natural gametogenesis, where parental centrioles are eliminated, allowing for de novo formation of young centrioles upon fertilization (Szollosi et al., 1972; Fishman et al., 2017).

4.3. The Centriolar Theory of Organismal Aging and its Reversal

- Mitotic Errors: Chromosome mis-segregation and aneuploidy (Gönczy, 2015).

- Ciliopathy and Signaling Defects: Disruption of crucial signaling pathways (Anvarian et al., 2019).

- Stem Cell Exhaustion: Disruption of asymmetric cell division, depleting regenerative pools (Yamashita et al., 2010; Liang et al., 2020).

4.4. The Rejuvenation Protocol: A Periodic Treatment

| Feature | Current Approach (Treating Diseases) | Harvesting Own Adult Stem Cells | Proposed IVG-based Strategy |

| Target | Symptoms (e.g., cancer, dementia) | N/A (propagates aged state) | Root cause (cellular aging) |

| Epigenetic Age | No change | Aged | Reset to embryonic state |

| Centriolar Age | No change | Aged | Reset to young state (de novo) |

| Long-term Efficacy | Low (whack-a-mole) | None | High (periodic systemic reset) |

| Civilizational Impact | None | None | High (safeguard against intellectual decline) |

5. The Societal Benefit: Civilizational Safeguard

5.1. Halting the Intellectual Drain and Accumulating Wisdom

5.2. Transforming Demographics and Alleviating the Burden of Aging

5.3. Enhancing Cultural and Scientific Continuity

5.4. Ethical and Equitable Implementation as a Prerequisite

6. Discussion and Conclusion

6.1. Synthesis

6.2. Addressing Limitations

- Scientific Hurdles: Perfecting human IVG, ensuring genomic stability, and safe differentiation of stem cells are formidable tasks (Zhou et al., 2016; Ditadi et al., 2015).

- The Equity Problem: This is the most significant ethical challenge, requiring proactive policy to avoid a dystopian outcome (Partridge et al., 2011; Farrelly, 2020).

- Societal Adaptation: Society would need to rethink concepts of career, relationships, and meaning (Weber, 2020), though the goal is healthspan, not prolonged decrepitude.

- Overpopulation: This Malthusian objection ignores demographic trends; the societies adopting this will have low birth rates, and solutions lie in the innovation a long-lived society enables (Vollset et al., 2020).

6.3. Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anvarian, Z., Mykytyn, K., Mukhopadhyay, S., Pedersen, L. B., & Christensen, S. T. (2019). Cellular signalling by primary cilia in development, organ function and disease. Nature Reviews Nephrology, 15(4), 199–219. [CrossRef]

- Bajekal, M. (2005). Healthy life expectancy by area deprivation: magnitude and trends in England, 1994-1999. Health Statistics Quarterly, 25, 18–27. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15804167/.

- Balbo, N., Billari, F. C., & Mills, M. (2013). Fertility in advanced societies: A review of research. European Journal of Population, 29(1), 1–38. [CrossRef]

- Balgopal, P. R. (2016). The impact of female education on fertility: A natural experiment from Nigeria. World Development, 87, 152–169. [CrossRef]

- Barban, N., Jansen, R., de Vlaming, R., Vaez, A., Mandemakers, J. J., Tropf, F. C., ... & Mills, M. C. (2016). Genome-wide analysis identifies 12 loci influencing human reproductive behavior. Nature Genetics, 48(12), 1462–1472. [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, J. P. (2016). Genetic evidence for natural selection in humans in the contemporary United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(28), 7774–7779. [CrossRef]

- Bostrom, N. (2014). Superintelligence: Paths, dangers, strategies. Oxford University Press.

- Brown, K. W., & Kasser, T. (2005). Are psychological and ecological well-being compatible? The role of values, mindfulness, and lifestyle. Social Indicators Research, 74(2), 349–368. [CrossRef]

- Chatterji, S., Byles, J., Cutler, D., Seeman, T., & Verdes, E. (2015). Health, functioning, and disability in older adults—present status and future implications. The Lancet, 385(9967), 563–575. [CrossRef]

- Conley, D. (2016). Socio-genomic research using genome-wide molecular data. Annual Review of Sociology, 42, 275–299. [CrossRef]

- de Grey, A., & Rae, M. (2007). Ending Aging: The Rejuvenation Breakthroughs That Could Reverse Human Aging in Our Lifetime. St. Martin's Press.

- de Magalhães, J. P. (2014). The scientific quest for lasting youth: prospects for curing aging. Rejuvenation Research, 17(5), 458–467. [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Scollon, C. N. (2006). Beyond the hedonic treadmill: Revising the adaptation theory of well-being. American Psychologist, 61(4), 305–314. [CrossRef]

- Ditadi, A., Sturgeon, C. M., & Keller, G. (2015). A view of human haematopoietic development from the Petri dish. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 16(1), 56–67. [CrossRef]

- Dong, X., Milholland, B., & Vijg, J. (2016). Evidence for a limit to human lifespan. Nature, 538(7624), 257–259. [CrossRef]

- Farrelly, C. (2020). The case for optimism about human longevity. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 75(1), 35–38. [CrossRef]

- Fishman, E. L., Jo, K., Nguyen, Q. P. H., Kong, D., Royfman, R., Cekic, A. R., ... & Avidor-Reiss, T. (2017). A novel atypical sperm centriole is functional during human fertilization. Nature Communications, 8(1), 2210. [CrossRef]

- Goldman, D. P., Cutler, D., Rowe, J. W., Michaud, P. C., Sullivan, J., Peneva, D., & Olshansky, S. J. (2013). Substantial health and economic returns from delayed aging may warrant a new focus for medical research. Health Affairs, 32(10), 1698–1705. [CrossRef]

- Gönczy, P. (2015). Centrosomes and cancer: revisiting a long-standing relationship. Nature Reviews Cancer, 15(11), 639–652. [CrossRef]

- Goodell, M. A., & Rando, T. A. (2015). Stem cells and healthy aging. Science, 350(6265), 1199–1204. [CrossRef]

- Green, L., & Myerson, J. (2004). A discounting framework for choice with delayed and probabilistic rewards. Psychological Bulletin, 130(5), 769–792. [CrossRef]

- Hartshorne, J. K., & Germine, L. T. (2015). When does cognitive functioning peak? The asynchronous rise and fall of different cognitive abilities across the life span. Psychological Science, 26(4), 433–443. [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K., Ogushi, S., Kurimoto, K., Shimamoto, S., Ohta, H., & Saitou, M. (2012). Offspring from oocytes derived from in vitro primordial germ cell-like cells in mice. Science, 338(6109), 971–975. [CrossRef]

- Hikabe, O., Hamazaki, N., Nagamatsu, G., Obata, Y., Hirao, Y., Hamada, N., ... & Saitou, M. (2016). Reconstitution in vitro of the entire cycle of the mouse female germ line. Nature, 539(7628), 299–303. [CrossRef]

- Hose, A., Küspert, S., & Schneider, M. V. (2020). The academic career landscape: A systematic review of the literature on academic work and life. Studies in Higher Education, 45(12), 2465–2482. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, A. M. (2016). Policy making for the long term in advanced democracies. Annual Review of Political Science, 19, 433–454. [CrossRef]

- Jeste, D. V., Ardelt, M., Blazer, D., Kraemer, H. C., Vaillant, G., & Meeks, T. W. (2010). Expert consensus on characteristics of wisdom: a Delphi method study. The Gerontologist, 50(5), 668–680. [CrossRef]

- Kanazawa, S. (2014). Intelligence and childlessness. Social Science Research, 48, 157–170. [CrossRef]

- Kasser, T., & Sheldon, K. M. (2000). Of wealth and death: Materialism, mortality salience, and consumption behavior. Psychological Science, 11(4), 348–351. [CrossRef]

- Kellstedt, P. M., Zahran, S., & Vedlitz, A. (2008). Personal efficacy, the information environment, and attitudes toward global warming and climate change in the United States. Risk Analysis, 28(1), 113–126. [CrossRef]

- Kravdal, Ø., & Rindfuss, R. R. (2008). Changing relationships between education and fertility: A study of women and men born 1940 to 1964. American Sociological Review, 73(5), 854–873. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y., Yang, N., Pan, G., Jin, L., & Liu, F. (2020). Centrosome dysfunction in hematopoietic stem cells and its clinical relevance. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports, 16(4), 637–647. [CrossRef]

- López-Otín, C., Blasco, M. A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M., & Kroemer, G. (2013). The hallmarks of aging. Cell, 153(6), 1194–1217. [CrossRef]

- Lynn, R., & Harvey, J. (2008). The decline of the world's IQ. Intelligence, 36(2), 112–120. [CrossRef]

- Lynn, R., & Van Court, M. (2004). New evidence of dysgenic fertility for intelligence in the United States. Intelligence, 32(2), 193–201. [CrossRef]

- Maher, T. M., & Baum, S. D. (2013). Adaptation to and recovery from global catastrophe. Sustainability, 5(4), 1461–1479. [CrossRef]

- Partridge, B., Lucke, J., & Hall, W. (2011). If we could live forever, should we? And who gets to decide? The American Journal of Bioethics, 11(9), 57–59.

- Partridge, B., Lucke, J., Bartlett, H., & Hall, W. (2009). Ethical, social, and personal implications of extended human lifespan identified by members of the public. Rejuvenation Research, 12(5), 351–357. [CrossRef]

- Peters, J., & Büchel, C. (2011). The neural mechanisms of inter-temporal decision-making: understanding variability. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(5), 227–239. [CrossRef]

- Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., & Greenberg, J. (2015). Thirty years of terror management theory: From genesis to revelation. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 52, pp. 1-70). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Sandeep, S., & Gopesh, A. (2017). The influence of temporal myopia on decision making. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 10(2-3), 89–104. [CrossRef]

- Shamosh, N. A., & Gray, J. R. (2008). Delay discounting and intelligence: A meta-analysis. Intelligence, 36(4), 289–305. [CrossRef]

- Simerly, C., Dominko, T., Navara, C., Payne, C., Capuano, S., Gosman, G., ... & Schatten, G. (2003). Molecular correlates of primate nuclear transfer failures. Science, 300(5617), 297. [CrossRef]

- Skirbekk, V. (2008). Fertility trends by social status. Demographic Research, 18, 145–180. [CrossRef]

- Szollosi, D., Calarco, P., & Donahue, R. P. (1972). Absence of centrioles in the first and second meiotic spindles of mouse oocytes. Journal of Cell Science, 11(2), 521–541. [CrossRef]

- Tkemaladze, J. (2023). Reduction, proliferation, and differentiation defects of stem cells over time: a consequence of selective accumulation of old centrioles in the stem cells?. Molecular Biology Reports, 50(3), 2751–2761. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I., Subbarao, R. B., & Rho, G. J. (2015). Human mesenchymal stem cells - current trends and future prospective. Bioscience Reports, 35(2), e00191. [CrossRef]

- Vollset, S. E., Goren, E., Yuan, C. W., Cao, J., Smith, A. E., Hsiao, T., ... & Murray, C. J. L. (2020). Fertility, mortality, migration, and population scenarios for 195 countries and territories from 2017 to 2100: a forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. The Lancet, 396(10258), 1285-1306. [CrossRef]

- Wade-Benzoni, K. A. (2002). A golden rule over time: Reciprocity in intergenerational allocation decisions. Academy of Management Journal, 45(5), 1011–1028. [CrossRef]

- Weber, A. M. (2020). The social implications of longevity. Nature Aging, 1(1), 8–9. [CrossRef]

- Wilmut, I., Schnieke, A. E., McWhir, J., Kind, A. J., & Campbell, K. H. (1997). Viable offspring derived from fetal and adult mammalian cells. Nature, 385(6619), 810–813. [CrossRef]

- Woodley of Menie, M. A., Figueredo, A. J., Sarraf, M. A., Hertler, S., & Fernandes, H. B. (2017). The rhythm of the west: A biohistory of the modern era, AD 1600 to the present. Journal of Social, Political, and Economic Studies, 32(4), 1–40.

- Yamashita, Y. M., Yuan, H., Cheng, J., & Hunt, A. J. (2010). Polarity in stem cell division: asymmetric stem cell division in development, cancer and aging. Development, 137(1), 19–32.

- Zhou, Q., Wang, M., Yuan, Y., Wang, X., Fu, R., Wan, H., ... & Xie, W. (2016). Complete meiosis from embryonic stem cell-derived germ cells in vitro. Cell Stem Cell, 18(3), 330–340. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).