1. From Observation to Design

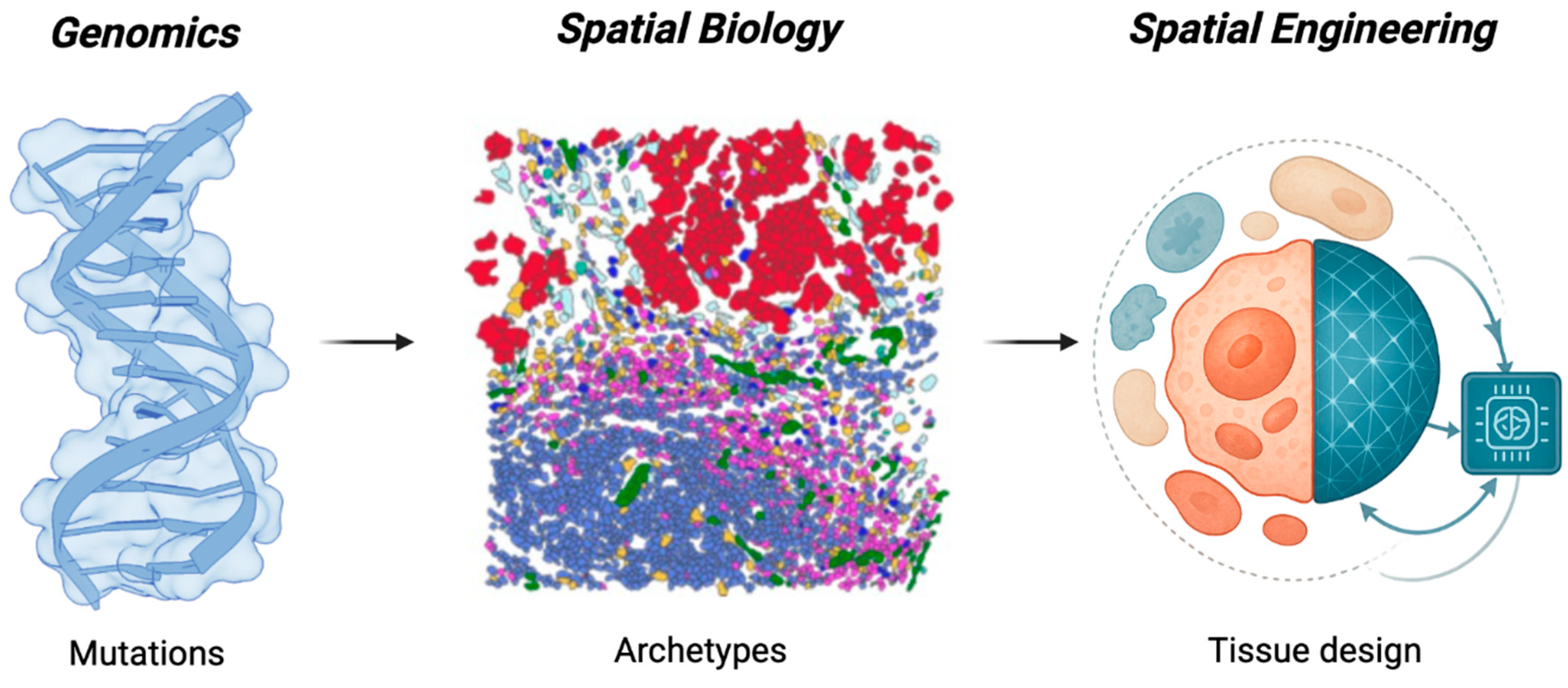

In just two decades, precision oncology has rewritten its own logic of discovery. The field began by decoding the parts list of cancer, the genomic circuitry that explained why tumors differ1. It is now learning to read the patterns that emerge when those parts assemble in space, defining ecological archetypes that predict therapeutic response2. The next transformation is already forming: the shift from recognizing patterns to designing them. Recent frameworks proposing sequential ecosystem nudges underscore the emerging interest in controllable trajectories3; Spatial Engineering generalizes this idea by defining a multidimensional control space and the predictive models required to steer it. Driven by the convergence of AI and spatial biology, the coming engineering era will treat tumor architecture not as a constraint but as a variable: something to be steered, stabilized, or disrupted by design.

This convergence is turning spatial biology from an observational discipline into a predictive one. Vast reference atlases and longitudinal patient cohorts now provide temporal depth; AI methods translate these data into quantitative models; and spatial technologies reveal the rules of cellular organization within intact tissues. Together they make it possible, for the first time, to model, perturb, and redesign the architecture of tumors in silico before acting in vivo.

Spatial technologies have shifted oncology from lists of differentially expressed genes to maps of tissue architecture: who is next to whom, under which physical and metabolic constraints, and how these relationships change over time4–9. These patterns, such as immune-infiltrated10, immune-excluded11, fibrotic12, hypoxic13, govern how drugs, nutrients, and signals move through tissue and, therefore, how therapy succeeds or fails. Yet most treatment decisions still rely on bulk molecular profiles, as if tumors were spatially uniform.

Breakthrough therapies already operate through spatial mechanisms, even if discovered empirically. Checkpoint require physical proximity between adaptive immune and cancer cells14,15; anti-angiogenic drugs remodel vascular geometry to normalize perfusion16; stromal-targeting agents relax the mechanical barriers that exclude immune infiltration17; bispecific antibodies and CAR-T cells physically rewire cellular networks18. The efficacy of all these treatments depends not only on molecular targets but on whether the tumor’s architecture is permissive to change2. In other words, modern oncology has been practicing spatial intervention without calling it that.

What has been missing is a predictive language of control. Until recently, these interventions were found through trial and error. The convergence of spatial biology, AI, and agent-based simulation now allows us to model tumor ecosystems directly, perturb their parameters in silico, and forecast architectural responses19–21. What was once empirical can now become rational: we can design, rather than stumble upon, the interventions that destabilize malignant equilibria or restore homeostatic organization.

We define Spatial Engineering as the deliberate reprogramming of tissue architecture through measurable and controllable parameters (cellular composition, spatial topology, microenvironmental context), and therapeutic timing. By shifting oncology from mutation hunting to ecosystem design, it frames treatment as the rational control of architecture (

Figure 1).

2. The Architecture of Malignancy

Tumors organize themselves in space5,6,22,23. Across organs and genetic backgrounds, cancer, stromal, and immune cells assemble into recurring architectural states that dictate how the disease behaves and how it can be treated8. Some tumors are immune-infiltrated, where cytotoxic lymphocytes penetrate the malignant core and maintain surveillance24,25. Others are immune-excluded, with immune cells confined to the periphery by fibrotic barriers or aberrant vasculature26. Still others form hypoxic or necrotic zones sustained by chaotic blood vessels and altered diffusion geometry27. These spatial phenotypes are not random, but emergent equilibria: stable yet reversible configurations maintained by feedback loops between cells, signaling gradients, and physical forces.

Each architecture defines how information, nutrients, and therapies reach the tumor’s interior. Dense collagen networks raise interstitial pressure and impede both immune entry and drug penetration28,29. Mechanical confinement within these rigid architectures can also reprogram cancer cells themselves, triggering cytoskeletal and chromatin remodeling that promotes invasive, drug-tolerant states30. Disordered vessels generate oxygen and pH gradients that shape metabolism and drug sensitivity31,32. Cytokine circuits between cancer cells, fibroblasts, and macrophages reinforce immune suppression and matrix deposition33,34. Together, these mechanical and biochemical interactions create self-stabilizing niches that persist even as their individual components change30.

From a systems perspective, malignancy can be understood as a problem of spatial stability and feedback control. Tumors resist therapy because their ecosystems settle into robust configurations that buffer against perturbation. Understanding which interactions maintain these configurations provides the substrate for Spatial Engineering: measurable, potentially reversible architectures that can be systematically reprogrammed.

3. The Logic of Spatial Control

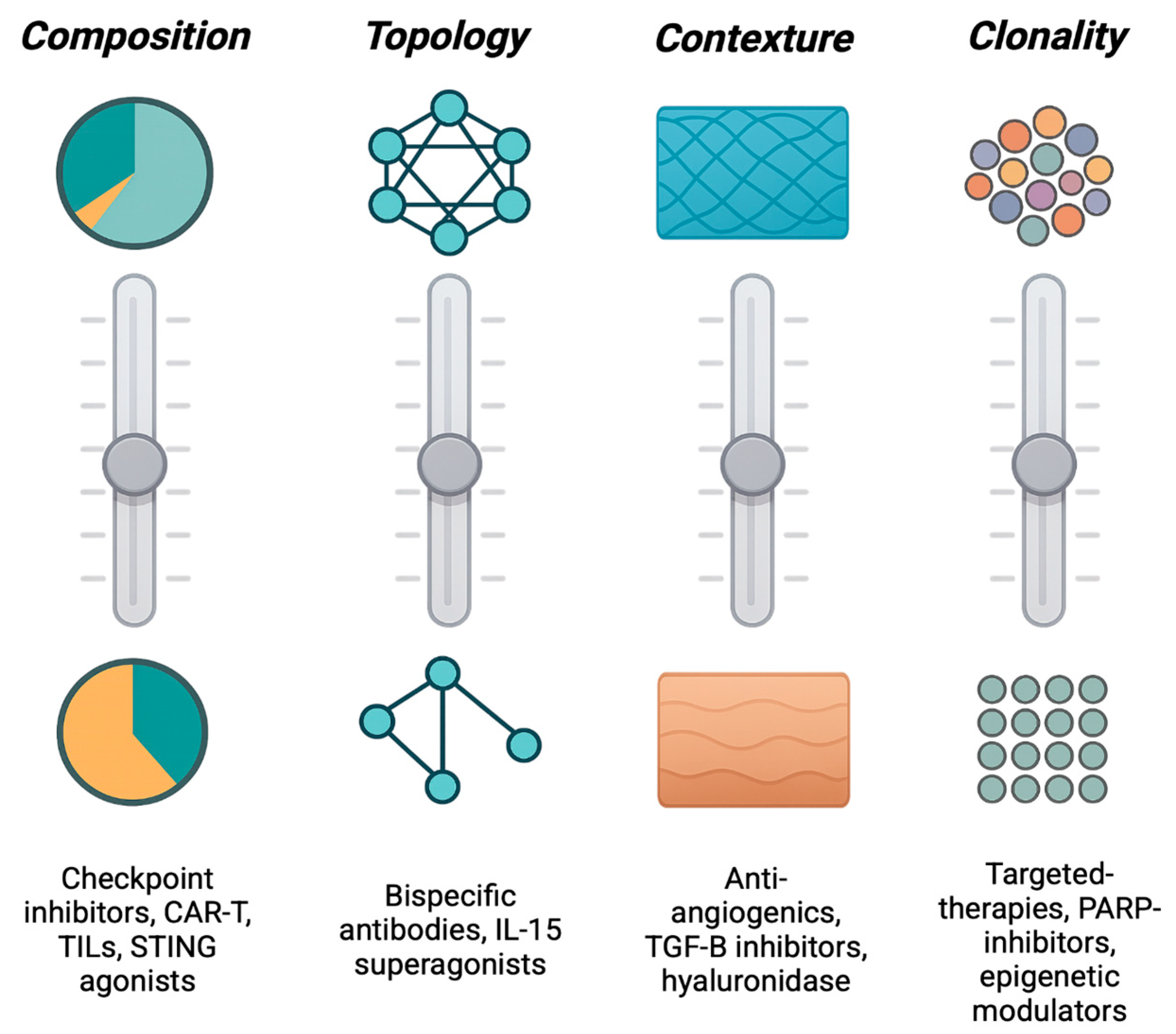

If architecture dictates therapeutic response, the next question is how to change it. Every tumor occupies a position within a multidimensional control space defined by variables that determine its organization: which cells are present, how they are arranged, and what physical and chemical fields connect them. Spatial Engineering treats these variables as design parameters: levers that can be adjusted to move a tumor from one spatial equilibrium to another (

Figure 2).

The most intuitive form of control is compositional. Tumor architecture changes when the cast of cells changes. Altering the abundance or state of specific populations (activating cytotoxic T cells, reprogramming macrophages, normalizing endothelium, or deactivating cancer-associated fibroblasts) reshapes the cellular mixture that defines an ecotype. Therapies such as checkpoint blockade or macrophage re-education act through this axis: they modify who occupies the tissue and in what proportion, transforming its ecological balance35.

Yet composition alone does not determine behavior; who touches whom matters just as much. The second axis, topological control, concerns the network of physical and signaling interactions among cells. Checkpoint inhibitors restore suppressed immune–tumor contact36–38, CAR-T and bispecific antibodies forge new synapses between effectors and targets39–41, and oncolytic viruses42 or cytokine gradients43,44 can open channels through previously isolated regions. These interventions rewire the connectivity graph of the tissue, converting disconnected compartments into communicating networks.

Cells and their interactions exist within a broader contexture environment: the diffusional and mechanical fields that channel oxygen, metabolites, and force. Anti-angiogenic drugs that alter vasculature formation45, TGF-β inhibitors that relax matrix stiffness46, and agents that modulate acidity or hypoxia47 all act through contextual control, reshaping the physical landscape that governs cell behavior. By altering perfusion, pressure, and gradient geometry, they redefine the environment in which all other interactions occur.

A fourth, increasingly recognized dimension is clonal control. Distinct genetic subclones often play specialized ecological roles: secreting factors that recruit stroma, remodel matrix, or suppress immunity48–50. Although numerically minor, these keystone clones can stabilize entire ecosystems. Targeting them, or the functions they provide, can collapse resistant architectures even if they are not the dominant clone. In such cases, success stems not from eradication but from destabilization: removing the structural linchpin that upholds the malignant configuration.

Together, these axes (compositional, topological, contextual, and clonal) define the spatial control space of a tumor: the coordinates through which therapies alter architectural equilibrium when measured through harmonized, cross-platform biomarkers and robust multi-region sampling. Each axis can be parameterized by measurable biomarkers. For example, cell-type fractions for composition, neighborhood contact metrics for topology, perfusion or stiffness indicators for context, and subclonal ecological functions for clonal control. However, these operational definitions require standardization and benchmarking across datasets to ensure reproducibility. Ensuring comparability of these spatial metrics across technologies is essential for reproducible coordinate assignment51.

Most therapies can be approximated by the coordinates they predominantly modify within this space and by its vector of effects across the architectural dimensions that sustain the ecosystem. Importantly, comprehensive, quantitative mappings of therapies across tumor types and platforms remain to be validated prospectively to confirm the generality of this coordinate framework. Transitions occur when one or more parameters cross a threshold that destabilizes the current configuration, allowing the system to reorganize into a more favorable state. The next challenge is to determine not only which variables to manipulate, but when.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that not all axes may be equally reversible. Architectural transitions can exhibit hysteresis (dependence on history, where restoring initial conditions does not automatically restore the initial state) or partial irreversibility. For example, once a tumor has calcified a fibrotic barrier, removing the signal that caused it may not dissolve the barrier. This makes it essential to identify controllability bounds where targeted perturbations reliably shift the ecosystem without inducing new stable malignant equilibria.

4. Dynamics and Timing: Designing Therapeutic Windows

Tissue architecture is not static. Each therapeutic intervention perturbs the local ecosystem, creating transient states of altered connectivity, perfusion, and immune visibility before new equilibria are established52. These fleeting configurations often determine whether treatment succeeds or fails53, yet they remain largely invisible in conventional trial designs. For example, transient ‘normalization’ after anti-VEGF or post-radiotherapy immune visibility indicates that some architectures can be shifted (albeit temporarily) supporting partial reversibility. Spatial Engineering seeks to quantify the bounds and path-dependence of these windows. Spatial Engineering expands beyond structure to include time as a controllable design variable, viewing therapeutic opportunity as a dynamic and measurable property of tissue organization rather than a fixed schedule.

Every perturbation, no matter how brief, reshapes the spatial organization of a tumor. Cytotoxic drugs and antibody–drug conjugates release neoantigens and danger signals that recruit antigen-presenting cells, producing a short-lived burst of immune visibility54–56. Anti-angiogenic therapies temporarily normalize vascular networks, improving oxygenation and drug penetration before hypoxia reasserts itself31. Stromal-modulating agents relax the extracellular matrix and increase lymphocyte infiltration for a limited period46. Each of these events creates a transient architectural window, a moment when the ecosystem becomes accessible, permissive, or sensitized.

This principle extends beyond pharmacology to endogenous physiological cycles. For example, chemotherapy efficacy in breast cancer oscillates across the oestrous cycle, with maximal response during the vascularly dilated, immune-permissive phase and reduced sensitivity during vasoconstricted, macrophage-rich dioestrus57. Such oscillations represent natural instances of tissue reorganization that modulate therapeutic accessibility in time58.

When subsequent interventions, such as checkpoint blockade or adoptive cell transfer, are timed to coincide with these windows, their efficacy can be dramatically amplified59. Recognizing and exploiting these transient states transforms therapy from a fixed sequence into an adaptive choreography. Clinically, this concept is exemplified by the “vascular normalization window” following anti-VEGF therapy, during which cytotoxics or checkpoint inhibitors achieve superior penetration60,61. Similar spatiotemporal synergy arises when radiotherapy precedes PD-1 blockade, exploiting the brief phase of enhanced antigen release and immune infiltration62–64.

Because these transitions unfold in both space and time, they can be monitored through architectural biomarkers rather than bulk molecular kinetics. Metrics such as stromal stiffness, immune–tumor proximity, vascular perfusion, or hypoxia gradients can signal when the tissue enters a transiently permissive phase. Real-time imaging, circulating spatial surrogates, or short-interval biopsies could provide actionable readouts of when to deliver the next therapy. While these approaches remain under development, they represent the foundation for clinically deployable longitudinal biomarkers that could translate spatial dynamics into actionable therapeutic timing. In this light, timing is a candidate controllable parameter, derived from the dynamics of tissue reorganization rather than imposed arbitrarily by clinical protocol.

5. Modeling the Control Space

Knowing what to perturb and when is only the beginning; the challenge is to determine how combinations of levers and timings interact to reshape the tumor ecosystem. Spatial Engineering addresses this through modeling, the bridge between observation and design. By integrating spatial measurements with mechanistic and data-driven simulations, modeling allows systematic exploration of the control space: the multidimensional landscape defined by compositional, topological, contextual, clonal, and temporal parameters.

At its simplest, this process links cause to consequence. Agent-based models and graph neural networks translate single-cell maps into dynamic simulations of how cells move, divide, and communicate within realistic tissue geometries. Perturbing these models in silico (altering cell states, contact networks, or microenvironmental constraints) reveals how local interventions propagate across the ecosystem. More abstract dynamical-systems formulations identify stability basins and tipping points, mapping where small changes in architecture lead to large shifts in state. Together, these approaches create aim to create digital twins of tumor ecosystems capable of forecasting how specific therapeutic sequences will reorganize the tissue over time. Prospective validation of these forecasted transitions in living systems remains a critical next step to ensure that modeled trajectories correspond to real architectural change.

Crucially, these simulations increasingly allow to test causality: by perturbing individual parameters in silico, one can forecast how the architecture will reorganize before committing to experimental or clinical intervention. In this way, modeling allows us to simulate thousands of virtual interventions, map their outcomes in control space, and identify the combinations most likely to drive controlled reorganization of malignant ecosystems within empirically demonstrable bound.

In doing so, it integrates the levers of control with the kinetics of their action to identify trajectories that drive malignant architectures toward collapse or reversion while minimizing collateral damage. Rather than testing endless empirical combinations, modeling allows clinicians and researchers to search the control space rationally, predicting which interventions, in which order and timing, are most likely to produce durable reprogramming. However, quantitative benchmarking against sequence-based predictors and fixed therapeutic schedules will be essential to confirm that architecture-guided models deliver genuine predictive gain and clinical utility. In this way, modeling transforms spatial biology from a descriptive map into a predictive laboratory, where each tumor’s architecture can be simulated, perturbed, and redesigned before a single dose is given.

6. The Spatial Engineering Loop: From Mapping to Manipulation

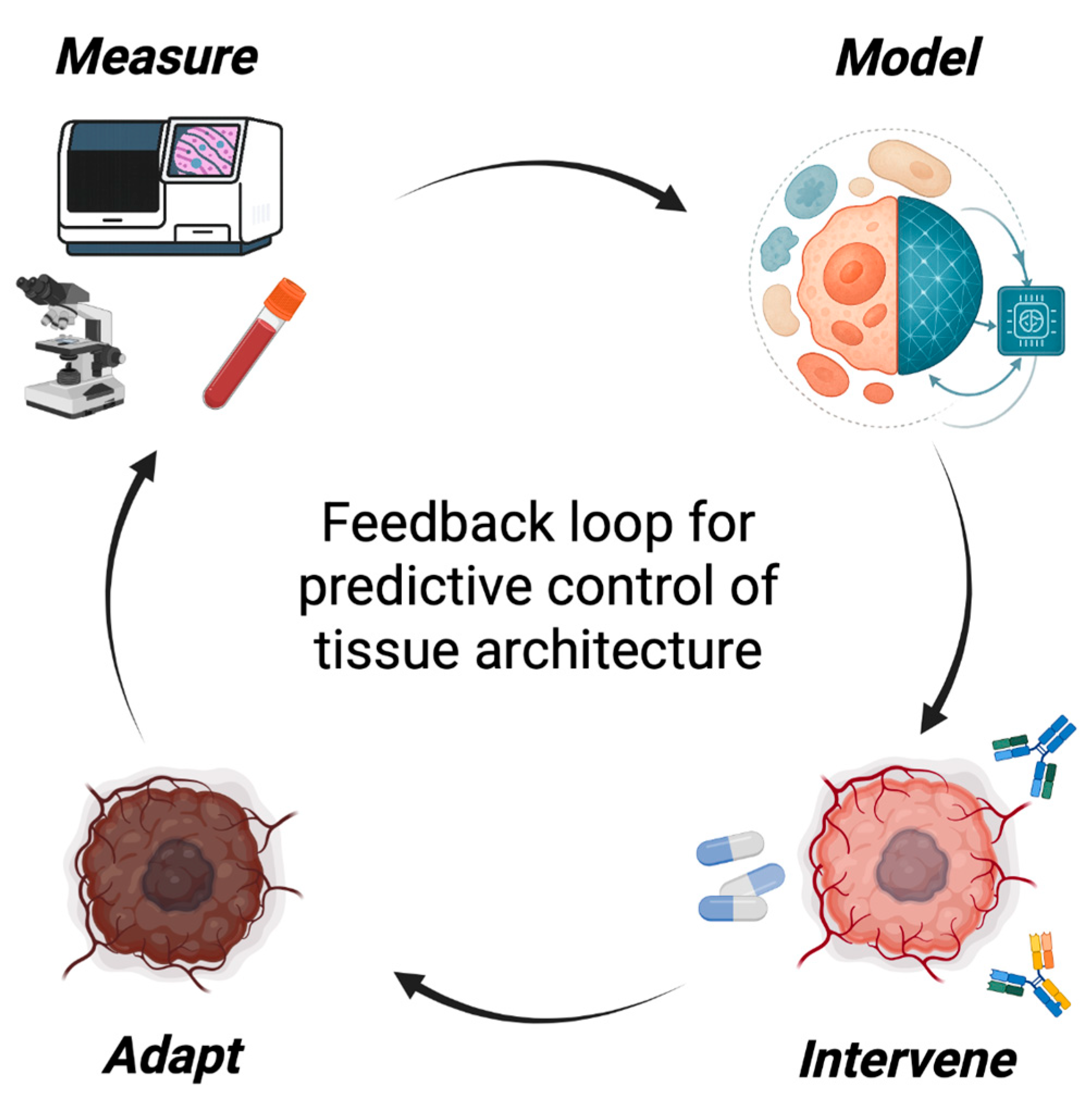

Spatial Engineering functions as a feedback discipline linking measurement, modeling, and intervention in a continuous cycle of refinement. This loop transforms spatial biology from a descriptive science into a predictive and actionable framework for architectural control (

Figure 3).

Each cycle begins with spatial measurement, capturing how cellular composition, topology, and microenvironmental context evolve under therapy. Importantly, because spatial technologies differ in resolution, chemistry, and segmentation pipelines51,65, cross-platform harmonization and uncertainty quantification are critical prerequisites for ensuring that loop-triggered measurements are comparable across regions and cohorts. High-resolution imaging65–67, multiplexed in situ assays68,69, and high-parameter proteomics70–72 now allow these dynamics to be monitored longitudinally, transforming static snapshots into temporal trajectories that describe the system’s evolving state and identify when a system approaches instability73–75.

From these data, modeling generates predictive representations of the tissue (using graph neural networks76, agent-based simulations77, or dynamical-systems models78) that forecast how local perturbations propagate through the ecosystem. As described above, these models identify which interventions, in which order and timing, are most likely to reprogram the architecture and restore accessibility or homeostasis.

This logic becomes more intuitive when examined in the context of a concrete tissue architecture, where the interplay of composition, topology, and context produces distinct evolutionary trajectories. One illustration comes from recent spatially initialized models of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

19. In these simulations, spatial transcriptomics and histologic maps of epithelial, mesenchymal, and fibroblast-rich regions were used to initialize a digital twin of each lesion. Mechanistic rules, such as ECM-dependent motility and fibroblast-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transitions, were then applied to forecast how alternative architectures would evolve over time. Perturbing fibroblast abundance or matrix organization in silico revealed sharp topological tipping points: lesions in which fibroblasts formed continuous encapsulating rings maintained architectural stability and restricted invasion, whereas those with patchy fibroblast distributions rapidly transitioned to invasive trajectories. These forecasts emerged directly from the interplay of compositional, topological, and contexture axes defined in

Figure 2, demonstrating how small differences in initial architecture can drive divergent spatial trajectories when passed through the Spatial Engineering loop (

Figure 3).

Insights from such simulations illustrate how the loop translates architectural forecasts into actionable intervention strategies, guiding intervention and converting simulation into strategy. Instead of applying fixed regimens, therapies are sequenced and tuned according to the system’s current position in control space, normalizing vasculature before immune activation, decompressing stroma before drug delivery, or targeting keystone clones once supportive niches have been dismantled.

The final step, adaptation, closes the loop. As tissues evolve under therapy, new equilibria emerge79, often accompanied by early-warning signatures such as rising spatial variance, flickering between alternative local architectures, or increasing correlation across distant regions80,81. Detecting these changes provides a means to anticipate transitions before they manifest. In practice, this could mean adjusting treatment in real time: escalating, sequencing, or pausing therapy as spatial indicators reveal the tissue’s trajectory.

Together, these four components (measurement, modeling, intervention, and adaptation) define the Spatial Engineering loop, a prospective framework for rational ecosystem control. Each stage informs the next, converting static maps into an evolving model of tissue organization. Embedded in experimental workflows and clinical trials, this loop can turn spatial biology into a genuine engineering discipline, one that designs, tests, and refines therapeutic strategies to collapse or restore tumor ecosystems through predictive control of architecture. Future work will need to benchmark closed-loop performance against static or heuristic treatment schedules, using quantitative metrics of predictive accuracy, lead-time, and clinical benefit, to establish the true added value of adaptive spatial control.

7. Challenges and Future Directions

Turning Spatial Engineering from a conceptual framework into a practical discipline will require overcoming several interconnected challenges. Each represents both an obstacle and an opportunity to transform how spatial data are used in medicine, from static description to predictive design and control.

Measurement across time remains the central limitation. Harmonization across space (platforms, laboratories, and regions) is critical to avoid systematic measurement bias. Moreover, most spatial profiling technologies still provide static snapshots, while the transitions that define tissue reorganization are inherently dynamic. Capturing these processes will require longitudinal approaches that reveal how architectures evolve under therapy: serial biopsies, intravital imaging, or computational reconstructions of pseudo-temporal trajectories82,83. Furthermore, accurately mapping the 'Clonal' axis remains challenging, often requiring the integration of spatial transcriptomics with inferred genomic features or emerging spatial DNA sequencing methods. Real progress will depend on developing minimally invasive longitudinal readouts that track architectural biomarkers such as immune proximity, stromal stiffness, or vascular perfusion in real time. Only when we can measure these variables continuously will therapy timing and sequence be guided by the actual state of the tissue rather than arbitrary clinical schedules.

Establishing causality is equally critical. Spatial correlations, even when statistically robust, do not prove control. To determine which variables truly stabilize or destabilize a given architecture, we need systematic perturbation experiments in organoids, explants, and engineered co-cultures where mechanical, chemical, or cellular parameters can be tuned independently. Integrating such systems with AI-guided agent-based modeling will allow iterative, semi-causal inference: perturb, observe, refine.

A further challenge will be the systematic mapping of therapeutic classes within this four-axis space. Cross-cohort analyses and prospective perturbation studies will be needed to quantify how different interventions shift compositional, topological, contexture, and clonal coordinates, and to calibrate the reproducibility of these trajectories. This approach will identify which features act as anchors of malignant stability and which serve as levers for therapeutic reprogramming. Prospective validation of model-predicted trajectories and transition points in vivo will be essential to confirm that simulated control strategies can indeed steer living architectures as forecasted.

Additionally, while the framework treats architectures as controllable equilibria, transitions may be path-dependent or partially irreversible. Mapping ‘controllability bounds’, where and when axes can be moved bidirectionally without loss of function, is essential. In practice, this will require cyclic, bidirectional perturbations and model-guided inference to quantify hysteresis loops and tipping points before claiming reliable steering.

Another frontier concerns evolutionary adaptation. Every architectural intervention creates new selection pressures. Tumors that adapt to immune infiltration may evolve new exclusion mechanisms; those that survive vascular normalization may shift toward alternative metabolic strategies. Maintaining control therefore requires continuous feedback between measurement and modeling, while also updating the digital twin as the tissue evolves. Adaptive therapy, long discussed in evolutionary oncology, gains new meaning in the spatial context: not simply adjusting dose or duration, but actively steering architecture as the ecosystem reorganizes.

Translation to the clinic will also be a challenge. Spatial datasets are rich but costly, and too slow to inform real-time treatment decisions. For Spatial Engineering to influence clinical practice, complex profiles must be distilled into clinically tractable biomarkers: minimal gene panels, imaging signatures, or histological features that classify a tumor’s architecture from standard biopsies. Developing and validating such surrogates will bridge the gap between research-grade data and bedside decision-making. Equally important will be defining quantitative metrics of spatial instability (e.g., variance, correlation length, or neighborhood entropy) as new clinical endpoints for adaptive trials where, instead of volume reduction, architectural change marks success.

Finally, there is a human and infrastructural challenge. Implementing Spatial Engineering will demand scientists fluent across biology, computation, and systems control, a skill set rarely combined in current training. Building this discipline will require cross-domain education, shared data repositories, and transparent modeling standards. Institutes that integrate spatial profiling, predictive modeling, and adaptive clinical translation can serve as prototypes for this new paradigm. By embedding feedback loops directly into experimental and clinical workflows, these centers will accelerate the transition from mapping to manipulation. A key next step will be formal benchmarking of Spatial Engineering models against established genomic and clinical predictors, ensuring that any adaptive or closed-loop advantage is empirically validated across independent cohorts. Equally important will be comparing adaptive feedback strategies with fixed-schedule or rule-based baselines, defining objective metrics of forecasting accuracy and therapeutic gain to confirm that closed-loop control confers measurable improvement.

Addressing these challenges will not only refine the toolkit of Spatial Engineering but will also define its identity as a discipline. Each step marks progress toward a science capable of designing and controlling tissue ecosystems rather than merely observing them. In doing so, Spatial Engineering will establish the foundation for the next era of precision medicine: one grounded in spatial prediction, rational intervention, and architectural control.

8. Outlook—The Design Era of Oncology

Spatial biology has changed what we can see. Spatial Engineering aims to change what we can do. The capacity to map tumors in exquisite detail has revealed that therapeutic success depends as much on architecture as on genotype. What has been missing is a language of control, a way to navigate the complex landscape of tissue organization not by chance, but by design. Spatial Engineering provides that language. It reframes therapy as a problem of architectural engineering, where measurable spatial variables become the levers of prediction, intervention, and repair.

In this framework, tumors are not inert collections of mutated cells but adaptive ecosystems governed by feedback among cellular composition, topology, and context. Therapies succeed when they redirect those feedbacks: opening immune access, normalizing perfusion, softening stroma, or extinguishing keystone clones that stabilize resistance. With spatial AI and agent-based modeling, these mechanisms can now be simulated and optimized before they reach the clinic. This could transform therapeutic development from empirical trial-and-error to rational ecosystem design, where the goal is not eradication per se, but the collapse or reversion of malignant ecosystems into stable tissue states.

Spatial Engineering thus completes the evolution of precision oncology. The genomic era identified mutations; the signaling era mapped networks; the spatial era revealed ecosystems. The next step is to control them. By measuring architecture, modeling stability, and intervening with intent, we can design trajectories of reorganization rather than react to failure. This logic extends beyond cancer: the same control principles apply to fibrosis, regeneration, and inflammation, where tissue stability and transition determine outcome.

As the necessary infrastructures (spatial pipelines, predictive models, and adaptive clinical frameworks) mature, spatial biology will evolve from static atlases to dynamic, designable models of tissue behavior. Therefore, modern oncology now enters its design era, where therapy itself becomes an engineered system. By turning the art of spatial perturbation into the science of architectural control, Spatial Engineering transforms treatment from the manipulation of molecules to the predictive reprogramming of ecosystems. Spatial Engineering marks the transition from mapping tumors to designing their cure.

References

- Bailey, M. H. et al.. Comprehensive Characterization of Cancer Driver Genes and Mutations. Cell 173, 371–385.e18 (2018).

- Combes, A. J., Samad, B. & Krummel, M. F. Defining and using immune archetypes to classify and treat cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 23, 491–505 (2023).

- Courau, T., Desai, A., Wagner, A., Combes, A. J. & Krummel, M. F. The coming era of nudge drugs for cancer. Cancer Cell 43, 1973–1979 (2025).

- Mo, C.-K. et al.. Tumour evolution and microenvironment interactions in 2D and 3D space. Nature 634, 1178–1186 (2024).

- Sibai, M. et al.. The spatial landscape of cancer hallmarks reveals patterns of tumor ecological dynamics and drug sensitivity. Cell Rep 44, 115229 (2025).

- Lomakin, A. et al.. Spatial genomics maps the structure, nature and evolution of cancer clones. Nature 611, 594–602 (2022).

- Sibai, M., Zacharias, M., McGranahan, N., Jamal-Hanjani, M. & Porta-Pardo, E. Cancer in 4D: Towards Spatiotemporal Hallmark Ecosystems. Preprints (2025) . [CrossRef]

- Combes, A. J. et al.. Discovering dominant tumor immune archetypes in a pan-cancer census. Cell 185, 184–203.e19 (2022).

- Luca, B. A. et al.. Atlas of clinically distinct cell states and ecosystems across human solid tumors. Cell 184, 5482–5496.e28 (2021).

- Maley, C. C., Koelble, K., Natrajan, R., Aktipis, A. & Yuan, Y. An ecological measure of immune-cancer colocalization as a prognostic factor for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 17, 131 (2015).

- Joyce, J. A. & Fearon, D. T. T cell exclusion, immune privilege, and the tumor microenvironment. Science 348, 74–80 (2015).

- Han, Y. et al.. Spatiotemporal analyses of the pan-cancer single-cell landscape reveal widespread profibrotic ecotypes associated with tumor immunity. Nat Cancer (2025) . [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y. et al.. Spatial transcriptomics reveals niche-specific enrichment and vulnerabilities of radial glial stem-like cells in malignant gliomas. Nat Commun 14, 1028 (2023).

- Grande, E. et al.. Spatial biomarkers of response to neoadjuvant therapy in muscle-invasive bladder cancer: the DUTRENEO trial. medRxiv (2025) . [CrossRef]

- Gil-Jimenez, A. et al.. Spatial relationships in the urothelial and head and neck tumor microenvironment predict response to combination immune checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Commun 15, 2538 (2024).

- Zuazo-Gaztelu, I. & Casanovas, O. Unraveling the Role of Angiogenesis in Cancer Ecosystems. Front Oncol 8, 248 (2018).

- Prakash, J. & Shaked, Y. The Interplay between Extracellular Matrix Remodeling and Cancer Therapeutics. Cancer Discov 14, 1375–1388 (2024).

- Fenis, A., Demaria, O., Gauthier, L., Vivier, E. & Narni-Mancinelli, E. New immune cell engagers for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol 24, 471–486 (2024).

- Johnson, J. A. I. et al.. Human interpretable grammar encodes multicellular systems biology models to democratize virtual cell laboratories. Cell 188, 4711–4733.e37 (2025).

- Ghaffarizadeh, A., Heiland, R., Friedman, S. H., Mumenthaler, S. M. & Macklin, P. PhysiCell: An open source physics-based cell simulator for 3-D multicellular systems. PLoS Comput Biol 14, e1005991 (2018).

- Ponce-de-Leon, M. et al.. PhysiBoSS 2.0: a sustainable integration of stochastic Boolean and agent-based modelling frameworks. NPJ Syst Biol Appl 9, 54 (2023).

- Elhanani, O., Ben-Uri, R. & Keren, L. Spatial profiling technologies illuminate the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell 41, 404–420 (2023).

- Khaliq, A. M. et al.. Spatial transcriptomic analysis of primary and metastatic pancreatic cancers highlights tumor microenvironmental heterogeneity. Nat Genet 56, 2455–2465 (2024).

- Barry, K. C. et al.. A natural killer-dendritic cell axis defines checkpoint therapy-responsive tumor microenvironments. Nat Med 24, 1178–1191 (2018).

- Galon, J. et al.. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science 313, 1960–1964 (2006).

- Sweis, R. F. et al.. Molecular Drivers of the Non-T-cell-Inflamed Tumor Microenvironment in Urothelial Bladder Cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 4, 563–568 (2016).

- Chen, Z., Han, F., Du, Y., Shi, H. & Zhou, W. Hypoxic microenvironment in cancer: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct Target Ther 8, 70 (2023).

- Zhang, Y. et al.. Mechanical forces in the tumor microenvironment: roles, pathways, and therapeutic approaches. J Transl Med 23, 313 (2025).

- Al-Hilal, T. A. et al.. Durotaxis is a driver and potential therapeutic target in lung fibrosis and metastatic pancreatic cancer. Nat Cell Biol 27, 1543–1554 (2025).

- Hunter, M. V. et al.. Mechanical confinement governs phenotypic plasticity in melanoma. Nature (2025) . [CrossRef]

- Martin, J. D., Seano, G. & Jain, R. K. Normalizing Function of Tumor Vessels: Progress, Opportunities, and Challenges. Annu Rev Physiol 81, 505–534 (2019).

- Ward, C. et al.. The impact of tumour pH on cancer progression: strategies for clinical intervention. Explor Target Antitumor Ther 1, 71–100 (2020).

- Timperi, E. et al.. At the Interface of Tumor-Associated Macrophages and Fibroblasts: Immune-Suppressive Networks and Emerging Exploitable Targets. Clin Cancer Res 30, 5242–5251 (2024).

- Mao, X. et al.. Crosstalk between cancer-associated fibroblasts and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment: new findings and future perspectives. Mol Cancer 20, 131 (2021).

- Ludin, A. et al.. CRATER tumor niches facilitate CD8 T cell engagement and correspond with immunotherapy success. Cell (2025) . [CrossRef]

- Gobbini, E. et al.. The Spatial Organization of cDC1 with CD8+ T Cells is Critical for the Response to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Patients with Melanoma. Cancer Immunol Res 13, 517–526 (2025).

- Rahim, M. K. et al.. Dynamic CD8 T cell responses to cancer immunotherapy in human regional lymph nodes are disrupted in metastatic lymph nodes. Cell 186, 1127–1143.e18 (2023).

- Javed, S. A., Najmi, A., Ahsan, W. & Zoghebi, K. Targeting PD-1/PD-L-1 immune checkpoint inhibition for cancer immunotherapy: success and challenges. Front Immunol 15, 1383456 (2024).

- Xiong, Y., Libby, K. A. & Su, X. The physical landscape of CAR-T synapse. Biophys J 123, 2199–2210 (2024).

- Liu, C. et al.. Population dynamics of immunological synapse formation induced by bispecific T cell engagers predict clinical pharmacodynamics and treatment resistance. Elife 12, (2023).

- Strohl, W. R. & Naso, M. Bispecific T-Cell Redirection versus Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR)-T Cells as Approaches to Kill Cancer Cells. Antibodies (Basel) 8, (2019).

- Wang, L., Chard Dunmall, L. S., Cheng, Z. & Wang, Y. Remodeling the tumor microenvironment by oncolytic viruses: beyond oncolysis of tumor cells for cancer treatment. J Immunother Cancer 10, (2022).

- Xu, S., Wang, Q. & Ma, W. Cytokines and soluble mediators as architects of tumor microenvironment reprogramming in cancer therapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 76, 12–21 (2024).

- Yi, M. et al.. Targeting cytokine and chemokine signaling pathways for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther 9, 176 (2024).

- Wallin, J. J. et al.. Atezolizumab in combination with bevacizumab enhances antigen-specific T-cell migration in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Nat Commun 7, 12624 (2016).

- Mai, Z., Lin, Y., Lin, P., Zhao, X. & Cui, L. Modulating extracellular matrix stiffness: a strategic approach to boost cancer immunotherapy. Cell Death Dis 15, 307 (2024).

- Peppicelli, S. et al.. Acidity and hypoxia of tumor microenvironment, a positive interplay in extracellular vesicle release by tumor cells. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 48, 27–41 (2025).

- Noble, R. et al.. Spatial structure governs the mode of tumour evolution. Nat Ecol Evol 6, 207–217 (2022).

- Somarelli, J. A. The Hallmarks of Cancer as Ecologically Driven Phenotypes. Front Ecol Evol 9, (2021).

- Vinci, M. et al.. Functional diversity and cooperativity between subclonal populations of pediatric glioblastoma and diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma cells. Nat Med 24, 1204–1215 (2018).

- Cervilla, S. et al.. Benchmarking of spatial transcriptomics platforms across six cancer types. bioRxiv (2024) . [CrossRef]

- Cui, X., Liu, S., Song, H., Xu, J. & Sun, Y. Single-cell and spatial transcriptomic analyses revealing tumor microenvironment remodeling after neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer 24, 111 (2025).

- Hockings, H. et al.. Adaptive Therapy Exploits Fitness Deficits in Chemotherapy-Resistant Ovarian Cancer to Achieve Long-Term Tumor Control. Cancer Res 85, 3503–3517 (2025).

- Fucikova, J. et al.. Detection of immunogenic cell death and its relevance for cancer therapy. Cell Death Dis 11, 1013 (2020).

- Shi, R., Jia, L., Lv, Z. & Cui, J. Another power of antibody-drug conjugates: immunomodulatory effect and clinical applications. Front Immunol 16, 1632705 (2025).

- Galluzzi, L., Guilbaud, E., Schmidt, D., Kroemer, G. & Marincola, F. M. Targeting immunogenic cell stress and death for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 23, 445–460 (2024).

- Bornes, L. et al.. The oestrous cycle stage affects mammary tumour sensitivity to chemotherapy. Nature 637, 195–204 (2025).

- Wang, C. et al.. Circadian tumor infiltration and function of CD8 T cells dictate immunotherapy efficacy. Cell 187, 2690–2702.e17 (2024).

- Choi, Y. & Jung, K. Normalization of the tumor microenvironment by harnessing vascular and immune modulation to achieve enhanced cancer therapy. Exp Mol Med 55, 2308–2319 (2023).

- Lin, Q.-X. et al.. Sequential treatment of anti-PD-L1 therapy prior to anti-VEGFR2 therapy contributes to more significant clinical benefits in non-small cell lung cancer. Neoplasia 59, 101077 (2025).

- Lee, W. S., Yang, H., Chon, H. J. & Kim, C. Combination of anti-angiogenic therapy and immune checkpoint blockade normalizes vascular-immune crosstalk to potentiate cancer immunity. Exp Mol Med 52, 1475–1485 (2020).

- Zhang, Z., Liu, X., Chen, D. & Yu, J. Radiotherapy combined with immunotherapy: the dawn of cancer treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther 7, 258 (2022).

- Gong, J., Le, T. Q., Massarelli, E., Hendifar, A. E. & Tuli, R. Radiation therapy and PD-1/PD-L1 blockade: the clinical development of an evolving anticancer combination. J Immunother Cancer 6, 46 (2018).

- Shen, Y. et al.. Combination radiation and αPD-L1 enhance tumor control by stimulating CD8+ PD-1+ TCF-1+ T cells in the tumor-draining lymph node. Nat Commun 16, 3522 (2025).

- Grases, D. & Porta-Pardo, E. A practical guide to spatial transcriptomics: lessons from over 1000 samples. Trends Biotechnol (2025) . [CrossRef]

- Moses, L. & Pachter, L. Museum of spatial transcriptomics. Nat Methods 19, 534–546 (2022).

- Lázár, E. & Lundeberg, J. Spatial architecture of development and disease. Nat Rev Genet (2025) . [CrossRef]

- Semba, T. & Ishimoto, T. Spatial analysis by current multiplexed imaging technologies for the molecular characterisation of cancer tissues. Br J Cancer 131, 1737–1747 (2024).

- Sheng, W. et al.. Multiplex Immunofluorescence: A Powerful Tool in Cancer Immunotherapy. Int J Mol Sci 24, (2023).

- Horvath, P. & Coscia, F. Spatial proteomics in translational and clinical research. Mol Syst Biol 21, 526–530 (2025).

- Keren, L. et al.. MIBI-TOF: A multiplexed imaging platform relates cellular phenotypes and tissue structure. Sci Adv 5, eaax5851 (2019).

- Schürch, C. M. et al.. Coordinated Cellular Neighborhoods Orchestrate Antitumoral Immunity at the Colorectal Cancer Invasive Front. Cell 182, 1341–1359.e19 (2020).

- Choi, M. E. et al.. Spatial transcriptomics of progression gene signature and tumor microenvironment leading to progression in mycosis fungoides. Blood Adv 9, 2871–2885 (2025).

- Gong, D., Arbesfeld-Qiu, J. M., Perrault, E., Bae, J. W. & Hwang, W. L. Spatial oncology: Translating contextual biology to the clinic. Cancer Cell 42, 1653–1675 (2024).

- Klughammer, J. et al.. A multi-modal single-cell and spatial expression map of metastatic breast cancer biopsies across clinicopathological features. Nat Med 30, 3236–3249 (2024).

- Ali, M., Richter, S., Ertürk, A., Fischer, D. S. & Theis, F. J. Graph neural networks learn emergent tissue properties from spatial molecular profiles. Nat Commun 16, 8419 (2025).

- Cogno, N., Axenie, C., Bauer, R. & Vavourakis, V. Agent-based modeling in cancer biomedicine: applications and tools for calibration and validation. Cancer Biol Ther 25, 2344600 (2024).

- Uthamacumaran, A. A review of dynamical systems approaches for the detection of chaotic attractors in cancer networks. Patterns (N Y) 2, 100226 (2021).

- de Visser, K. E. & Joyce, J. A. The evolving tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic outgrowth. Cancer Cell 41, 374–403 (2023).

- Bareham, B., Dibble, M. & Parsons, M. Defining and modeling dynamic spatial heterogeneity within tumor microenvironments. Curr Opin Cell Biol 90, 102422 (2024).

- Ma, Z., Luo, Y., Zeng, C. & Zheng, B. Spatiotemporal diffusion as early warning signal for critical transitions in spatial tumor-immune system with stochasticity. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, (2022).

- Quek, C. et al.. Single-cell spatial multiomics reveals tumor microenvironment vulnerabilities in cancer resistance to immunotherapy. Cell Rep 43, 114392 (2024).

- Liu, Y. et al.. Image-based inference of tumor cell trajectories enables large-scale cancer progression analysis. Sci Adv 11, eadv9466 (2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).