Submitted:

22 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

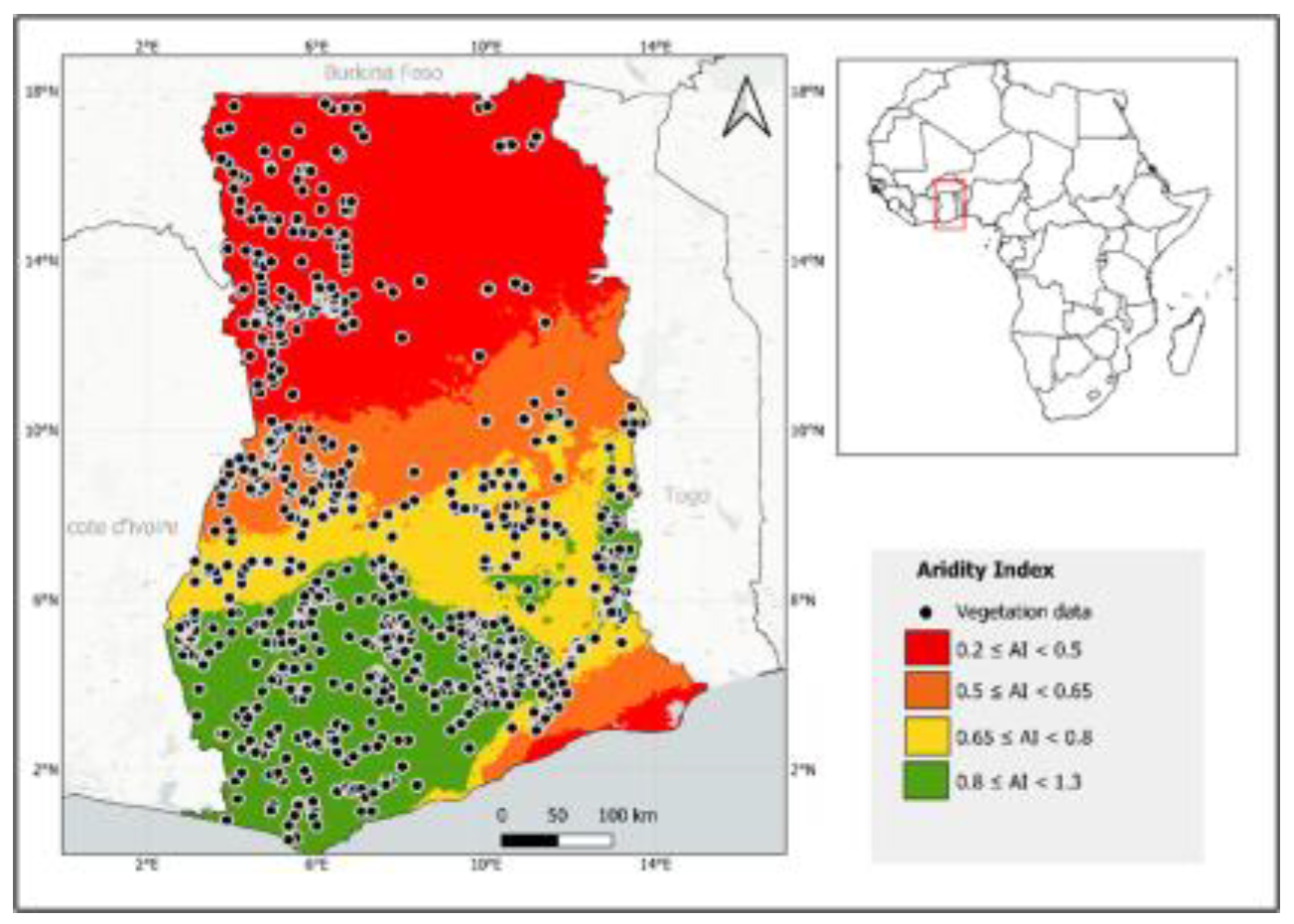

2.1. Study Area and Datasets

2.2. Vegetation Data Extraction

2.2.1. Spatial Autocorrelation Diagnostics

2.2.2. Biodiversity Metric: Species Richness

2.3. Above-Ground Biomass (AGB) Dataset and Extraction

2.3.1. Validation of Above-Ground Biomass with GEDI Biomass Footprints

2.4. Climate Data (Aridity Index)

2.5. Forest Fragmentation Metrics

| Fragmentation metrics | Equation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patches (NP) | Total number of discrete forest patches within the buffer. Higher NP indicates greater fragmentation. |

|

|

Landscape Shape Index (LSI) |

Quantifies shape complexity by standardizing total edge length to landscape area; 0.25 corrects for raster geometry. |

|

| Mean Shape Index (MSI) | Average shape irregularity of forest patches; higher values indicate more complex patch form. |

|

| Edge density (ED) | Total length of forest edges (m) per hectare of landscape area (A). indicates the relative amount of edge habitat. | |

| Mean Patch Area (Area_MN) | Arithmetic means of forest patch areas. Reflects average patch size and connectivity. |

2.6. Temporal Consistency and Dataset Alignment

2.7. Temporal Consistency and Dataset Alignment

2.7.1. Effects of Aridity Index on Above-Ground Biomass

2.7.2. Multicollinearity and Dimensionality Diagnostics

2.7.3. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

2.7.4. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

3. Results

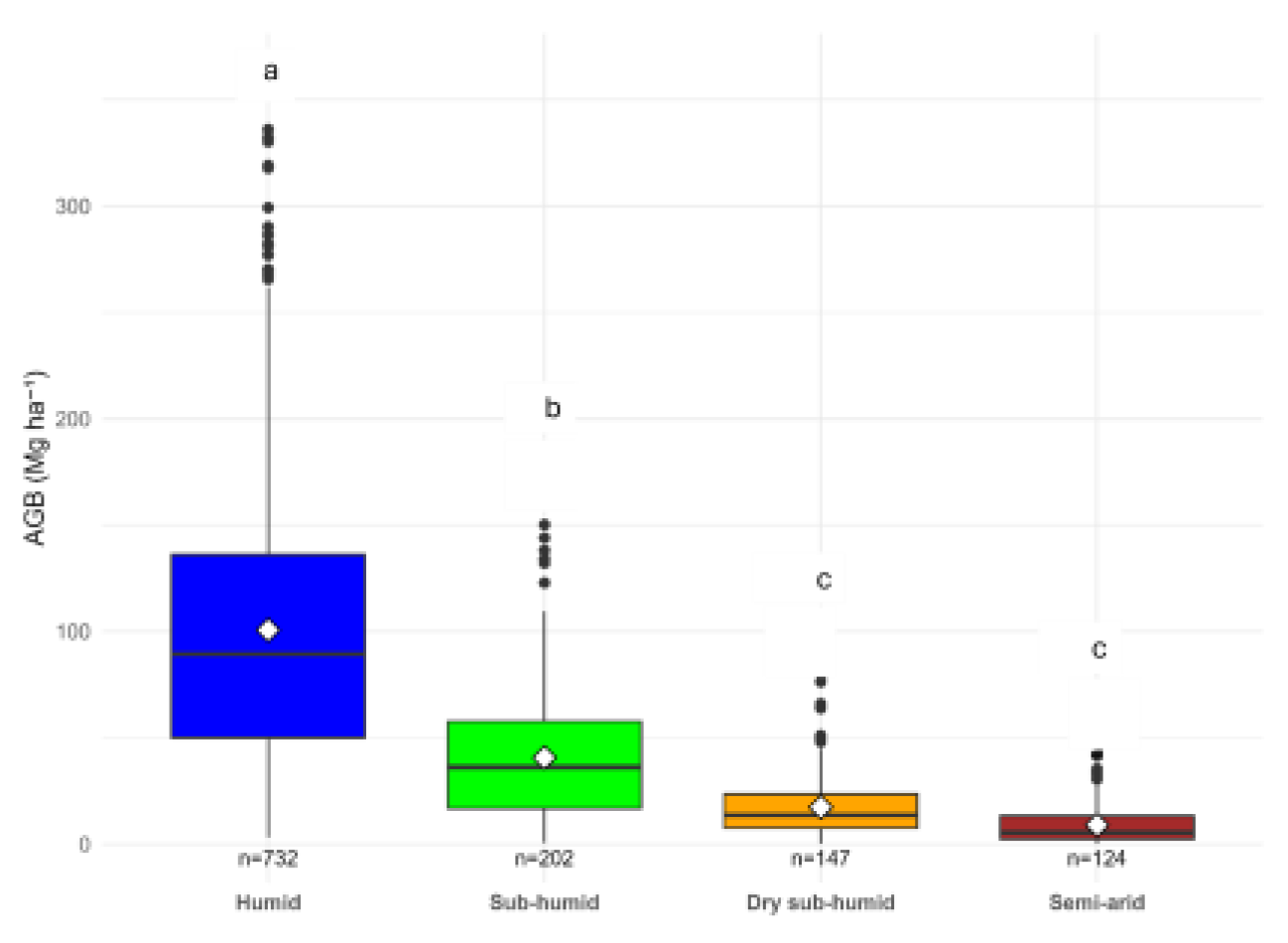

3.1. Effects of Aridity on Above-Ground Biomass

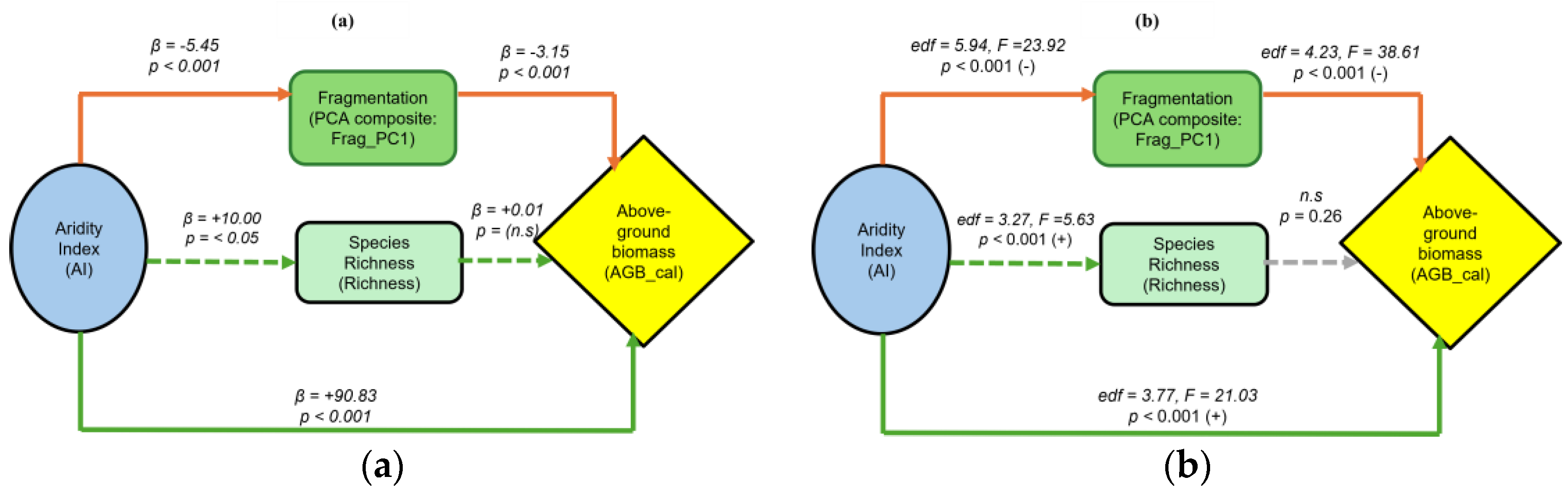

3.2. Structural Pathways: Linear and Nonlinear SEMs

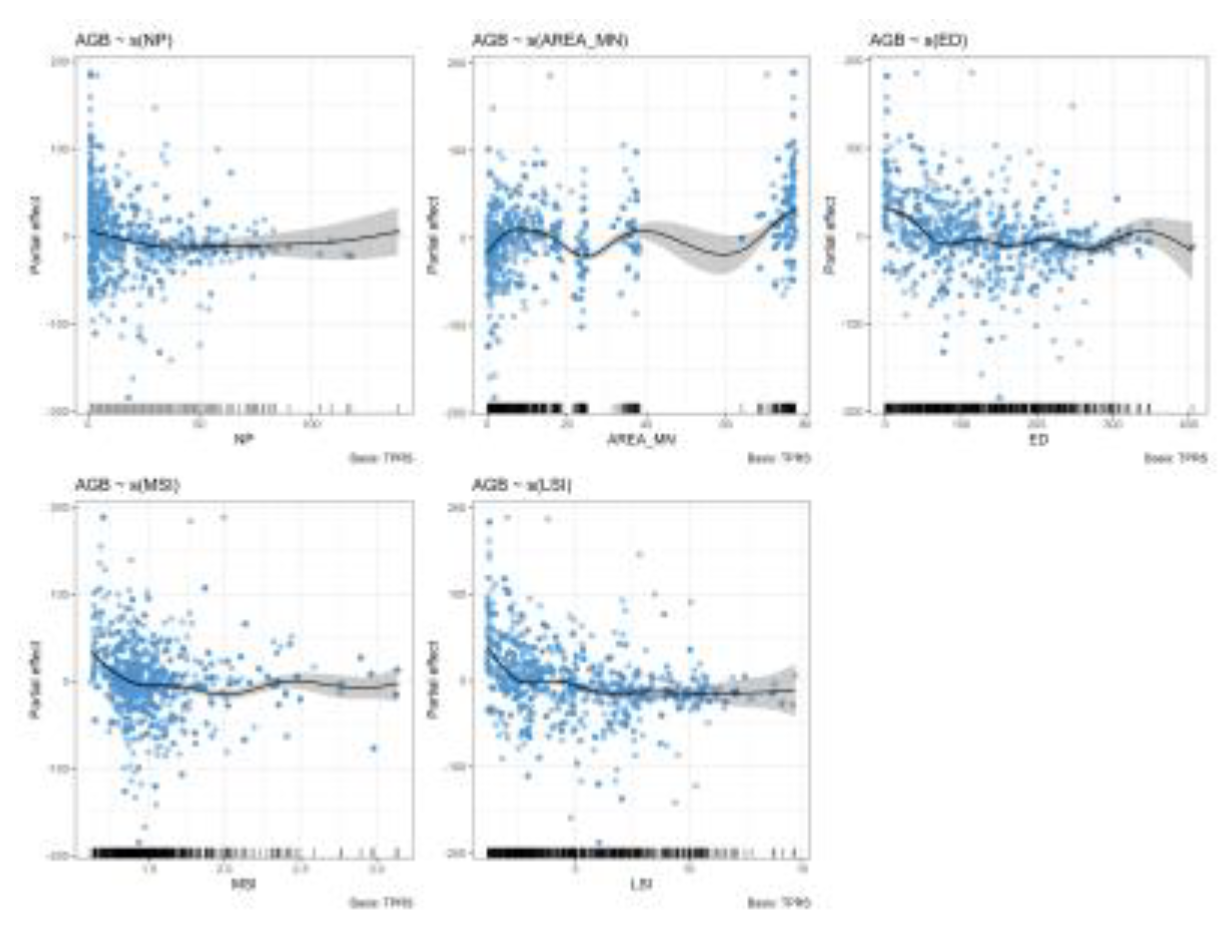

3.3. Functional Forms of Fragmentation Effects

4. Discussion

4.1. Aridity as Dominant Driver of Above-Ground Biomass Decline

4.2. Fragmentation as Mediator of Aridity Impacts on Above-Ground Biomass

4.3. Limited Role of Biodiversity in Mediating Aridity–Biomass Relationships

4.4. Functional Responses of Biomass to Fragmentation Metrics

4.5. Functional Responses of Biomass to Fragmentation Metrics

4.6. Management and Policy Implications Under Climate Change

4.7. Limitations and Future Direction

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGB | Above-ground Biomass |

| AFR100 | African Forest Restoration Initiative |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| AI | Aridity Index |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| AREA_MN | Mean Patch Area |

| CGLS | Copernicus Global Land Service |

| CGLS-LC100 | Copernicus global land service dynamic land cover map (100m) |

| ED | Edge Density |

| ESA | European Space Agency |

| ESA-CCI | European Space Agency Climate Change Initiative (biomass) |

| ETs | Reference Evapotranspiration |

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| GAM | General Additive Model |

| GBIF | Global Biodiversity Information Facility |

| GEE | Google Earth Engine |

| GEDI | Global Ecosystem Dynamics Investigation |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| LSI | Landscape Shape Index |

| MSI | Mean Shape Index |

| NP | Number of Patches |

| NCCP | National Climate Change Policy |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| REDD+ | Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| SFTS | Space for Time Substitution |

| UNEP | United Nations Environmental Programme |

| VIF | Variable Inflation Factor |

References

- Zhang, X.; Huang, X. Human disturbance caused stronger influences on global vegetation change than climate change. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Birdsey, R.A.; Fang, J.; Houghton, R.; Kauppi, P.E.; Kurz, W.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Shvidenko, A.; Lewis, S.L.; Canadell, J.G.; et al. A Large and Persistent Carbon Sink in the World’s Forests. Science 2011, 333, 988–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saatchi, S.S.; Harris, N.L.; Brown, S.; Lefsky, M.; Mitchard, E.T.A.; Salas, W.; Zutta, B.R.; Buermann, W.; Lewis, S.L.; Hagen, S.; et al. Benchmark map of forest carbon stocks in tropical regions across three continents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 9899–9904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilman, D.; Lehman, C. Human-caused environmental change: Impacts on plant diversity and evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001, 98, 5433–5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodart, C.; Brink, A.B.; Donnay, F.; Lupi, A.; Mayaux, P.; Achard, F. Continental estimates of forest cover and forest cover changes in the dry ecosystems of Africa between 1990 and 2000. J. Biogeogr. 2013, 40, 1036–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asubonteng, K.; Pfeffer, K.; Ros-Tonen, M.; Verbesselt, J.; Baud, I. Effects of Tree-crop Farming on Land-cover Transitions in a Mosaic Landscape in the Eastern Region of Ghana. Environ. Manag. 2018, 62, 529–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare, R.; Afari-Sefa, V.; Osei-Owusu, Y.; Pabi, O. Cocoa agroforestry for increasing forest connectivity in a fragmented landscape in Ghana. Agrofor. Syst. 2014, 88, 1143–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyngrope, O.R.; Kumar, M.; Pebam, R.; Singh, S.K.; Kundu, A.; Lal, D. Investigating forest fragmentation through earth observation datasets and metric analysis in the tropical rainforest area. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Gigorro, S.; Saura, S. Forest Fragmentation Estimated from Remotely Sensed Data: Is Comparison Across Scales Possible? For. Sci. 2005, 51, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, N.M.; Brudvig, L.A.; Clobert, J.; Davies, K.F.; Gonzalez, A.; Holt, R.D.; Lovejoy, T.E.; Sexton, J.O.; Austin, M.P.; Collins, C.D.; et al. Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastias, C.C.; Castilla, G.R.; Zarzosa, P.S.; Herraiz, A.D.; Herranz, N.G.; Ruiz-Benito, P.; Barrón, V.; Pérez, J.L.Q.; Villar, R. Differential aridity-induced variations in ecosystem multifunctionality between Iberian Pinus and Quercus Mediterranean forests. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsu, K.; Bonin, O. Assessing landscape fragmentation and its implications for biodiversity conservation in the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area (GAMA) of Ghana. Discov. Environ. 2023, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner Monica (1996) Landscape Ecology Theory and Practice. 72–82.

- Flowers, B.; Huang, K.-T.; Aldana, G.O. Analysis of the Habitat Fragmentation of Ecosystems in Belize Using Landscape Metrics. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aabeyir, R.; Adu-Bredu, S.; Agyare, W.A.; Weir, M.J.C. Allometric models for estimating aboveground biomass in the tropical woodlands of Ghana, West Africa. For. Ecosyst. 2020, 7, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurance, W.F.; Lovejoy, T.E.; Vasconcelos, H.L.; Bruna, E.M.; Didham, R.K.; Stouffer, P.C.; Gascon, C.; Bierregaard, R.O.; Laurance, S.G.; Sampaio, E. Ecosystem Decay of Amazonian Forest Fragments: a 22-Year Investigation. Conserv. Biol. 2002, 16, 605–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, Y.; Roberts, J.T.; Betts, R.A.; Killeen, T.J.; Li, W.; Nobre, C.A. Climate Change, Deforestation, and the Fate of the Amazon. Science 2008, 319, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, O.L.; Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Lewis, S.L.; Fisher, J.B.; Lloyd, J.; López-González, G.; Malhi, Y.; Monteagudo, A.; Peacock, J.; Quesada, C.A.; et al. Drought Sensitivity of the Amazon Rainforest. Science 2009, 323, 1344–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.A.; Piper, S.C.; Keeling, C.D.; Clark, D.B. Tropical rain forest tree growth and atmospheric carbon dynamics linked to interannual temperature variation during 1984–2000. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 5852–5857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduro, K.; Mohren, G.; Peña-Claros, M.; Kyereh, B.; Arts, B. Tracing forest resource development in Ghana through forest transition pathways. Land Use Policy 2015, 48, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addo-Fordjour P, Obeng S, Anning A, Addo M (2009) Floristic composition, structure and natural regeneration in a moist semi-deciduous forest following anthropogenic disturbances and plant invasion. Int J Biodivers Conserv 1:21–37.

- Mensah, S.; Veldtman, R.; Assogbadjo, A.E.; Ham, C.; Kakaï, R.G.; Seifert, T. Ecosystem service importance and use vary with socio-environmental factors: A study from household-surveys in local communities of South Africa. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinck, K.; Fischer, R.; Groeneveld, J.; Lehmann, S.; De Paula, M.D.; Pütz, S.; Sexton, J.O.; Song, D.; Huth, A. High resolution analysis of tropical forest fragmentation and its impact on the global carbon cycle. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidumayo E, Gumbo DJ (2010) The dry forests and woodlands of Africa: managing for products and services. Earthscan Libr.

- Chaplin-Kramer, R.; Ramler, I.; Sharp, R.; Haddad, N.M.; Gerber, J.S.; West, P.C.; Mandle, L.; Engstrom, P.; Baccini, A.; Sim, S.; et al. Degradation in carbon stocks near tropical forest edges. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njomaba, E.; Mushtaq, F.; Nagbija, R.K.; Yakalim, S.; Aikins, B.E.; Surovy, P. Adopting Land Cover Standards for Sustainable Development in Ghana: Challenges and Opportunities. Land 2025, 14, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampim, P.A.Y.; Ogbe, M.; Obeng, E.; Akley, E.K.; MacCarthy, D.S. Land Cover Changes in Ghana over the Past 24 Years. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawer, E.A. Predicting the impact of climate change on the potential distribution of a critically endangered avian scavenger, Hooded Vulture Necrosyrtes monachus, in Ghana. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 49, e02804–e02804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofori, S.A.; Asante, F.; Boateng, T.A.B.; Dahdouh-Guebas, F. The composition, distribution, and socio-economic dimensions of Ghana's mangrove ecosystems. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbam, T.; Johnson, F.A.; Dash, J.; Padmadas, S.S. Spatiotemporal Variations in Rainfall and Temperature in Ghana Over the Twentieth Century, 1900–2014. Earth Space Sci. 2018, 5, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare (2021) Plants of Ghana. Version 1.1. In: Ghana Herb. Occur. dataset. [CrossRef]

- Beck, J.; Böller, M.; Erhardt, A.; Schwanghart, W. Spatial bias in the GBIF database and its effect on modeling species' geographic distributions. Ecol. Informatics 2014, 19, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello-Lammens, M.E.; Boria, R.A.; Radosavljevic, A.; Vilela, B.; Anderson, R.P. spThin: an R package for spatial thinning of species occurrence records for use in ecological niche models. Ecography 2015, 38, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillebrand, H.; Bennett, D.M.; Cadotte, M.W. Consequences of dominance: A review of evenness effects and local and regional ecosystem processes. Ecology 2008, 89, 1510–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, S.A.; Szöcs, E. taxize: taxonomic search and retrieval in R. F1000Research 2013, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, C.; Weigelt, P.; Kreft, H. Multidimensional biases, gaps and uncertainties in global plant occurrence information. Ecol. Lett. 2016, 19, 992–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ficetola, G.F.; Mazel, F.; Thuiller, W. Global determinants of zoogeographical boundaries. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 89–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandom, C.; Faurby, S.; Sandel, B.; Svenning, J.-C. Global late Quaternary megafauna extinctions linked to humans, not climate change. Proc. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2014, 281, 20133254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoro M, Cartus O (2024) ESA Biomass Climate Change Initiative (Biomass_cci): Global datasets of forest above-ground biomass for the years 2010, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021, v5.01. In: NERC EDS Cent. Environ. Data Anal. https://gee-community-catalog.org/projects/cci_agb/#dataset-preprocessing-for-gee. Accessed 5 Apr 2024.

- Dubayah R, Tang H, Armston J, et al (2021) GEDI L2B Canopy Cover and Vertical Profile Metrics Data Global Footprint Level V002 [Data set]. In: NASA L. Process. Distrib. Act. Arch. Cent. https://doi.org/10.5067/GEDI/GEDI02_B.002. Accessed 20 Sep 2025.

- Hu, T.; Su, Y.; Xue, B.; Liu, J.; Zhao, X.; Fang, J.; Guo, Q. Mapping Global Forest Aboveground Biomass with Spaceborne LiDAR, Optical Imagery, and Forest Inventory Data. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, N.; Narine, L.L.; Wilson, A.E. Forest Aboveground Biomass Estimation Using Airborne LiDAR: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. For. 2025, 123, 389–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zomer, R.J.; Xu, J.; Trabucco, A. Version 3 of the Global Aridity Index and Potential Evapotranspiration Database. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton N, Thomas DS. (1997) World atlas of desertification. In: United Nations Environ. Program. https://opac.library.strathmore.edu/bib/33981. Accessed 5 Apr 2024.

- McGargical K, Cushman S, Ene E (2012) Spatial Pattern Analysis Program for Categorical Maps. https://www.fragstats.org.

- Enaruvbe GO, Atafo OP (2018) A Long-Term Assessment of Habitat Fragmentation in Coastal Wetlands, Niger Delta, Nigeria. Ife Soc Sci Rev 26:36–47.

- Hansen, M.C.; Potapov, P.V.; Moore, R.; Hancher, M.; Turubanova, S.A.; Tyukavina, A.; Thau, D.; Stehman, S.V.; Goetz, S.J.; Loveland, T.R.; et al. High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change. Science 2013, 342, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, E.O.; Macgregor, C.J.; Sloan, S.; Sayer, J. Deforestation is driven by agricultural expansion in Ghana's forest reserves. Sci. Afr. 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blois, J.L.; Williams, J.W.; Fitzpatrick, M.C.; Jackson, S.T.; Ferrier, S. Space can substitute for time in predicting climate-change effects on biodiversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 9374–9379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RCoreTeam (2024) A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R version 4.3.3. https://www.r-project.org/.

- Allen, M. (Ed.) The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dormann, C.F.; Elith, J.; Bacher, S.; Buchmann, C.; Carl, G.; Carré, G.; Marquéz, J.R.G.; Gruber, B.; Lafourcade, B.; Leitão, P.J.; et al. Collinearity: A review of methods to deal with it and a simulation study evaluating their performance. Ecography 2013, 36, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood S. (2017) Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R, Second Edition (2nd ed.). Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- Malhi, Y.; Baker, T.R.; Phillips, O.L.; Almeida, S.; Alvarez, E.; Arroyo, L.; Chave, J.; Czimczik, C.I.; Di Fiore, A.; Higuchi, N.; et al. The above-ground coarse wood productivity of 104 Neotropical forest plots. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2004, 10, 563–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Dudík, M. Modeling of species distributions with Maxent: new extensions and a comprehensive evaluation. Ecography 2008, 31, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choat, B.; Jansen, S.; Brodribb, T.J.; Cochard, H.; Delzon, S.; Bhaskar, R.; Bucci, S.J.; Feild, T.S.; Gleason, S.M.; Hacke, U.G.; et al. Global convergence in the vulnerability of forests to drought. Nature 2012, 491, 752–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chave, J.; Andalo, C.; Brown, S.; Cairns, M.A.; Chambers, J.Q.; Eamus, D.; Fölster, H.; Fromard, F.; Higuchi, N.; Kira, T.; et al. Tree allometry and improved estimation of carbon stocks and balance in tropical forests. Oecologia 2005, 145, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.L.; Lopez-Gonzalez, G.; Sonké, B.; Affum-Baffoe, K.; Baker, T.R.; Ojo, L.O.; Phillips, O.L.; Reitsma, J.M.; White, L.; Comiskey, J.A.; et al. Increasing carbon storage in intact African tropical forests. Nature 2009, 457, 1003–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, B.P.; Bowman, D.M. What controls the distribution of tropical forest and savanna? Ecol. Lett. 2012, 15, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brienen, R.J.W.; Phillips, O.L.; Feldpausch, T.R.; Gloor, E.; Baker, T.R.; Lloyd, J.; Lopez-Gonzalez, G.; Monteagudo-Mendoza, A.; Malhi, Y.; Lewis, S.L.; et al. Long-term decline of the Amazon carbon sink. Nature 2015, 519, 344–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC (2021) Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Laurance, W.F.; Useche, D.C.; Rendeiro, J.; Kalka, M.; Bradshaw, C.J.A.; Sloan, S.P.; Laurance, S.G.; Campbell, M.; Abernethy, K.; Alvarez, P.; et al. Averting biodiversity collapse in tropical forest protected areas. Nature 2012, 489, 290–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, E.N.; Asner, G.P.; Keller, M.; Knapp, D.E.; Oliveira, P.J.; Silva, J.N. Forest fragmentation and edge effects from deforestation and selective logging in the Brazilian Amazon. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 1745–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubert, F.; Fischer, R.; Groeneveld, J.; Lehmann, S.; Müller, M.S.; Rödig, E.; Wiegand, T.; Huth, A. Global patterns of tropical forest fragmentation. Nature 2018, 554, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleman, J.C.; Staver, A.C.; Gillespie, T. Spatial patterns in the global distributions of savanna and forest. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2018, 27, 792–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abugre, S.; Asigbaase, M.; Kumi, S.; Nkoah, G.; Asare, A. Forest landscape degradation, carbon loss and ecological consequences of illegal gold mining in Ghana. Discov. For. 2025, 1, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng, E.A.; Oduro, K.A.; Obiri, B.D.; Abukari, H.; Guuroh, R.T.; Djagbletey, G.D.; Appiah-Korang, J.; Appiah, M. Impact of illegal mining activities on forest ecosystem services: local communities’ attitudes and willingness to participate in restoration activities in Ghana. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qie, L.; Lewis, S.L.; Sullivan, M.J.P.; Lopez-Gonzalez, G.; Pickavance, G.C.; Sunderland, T.; Ashton, P.; Hubau, W.; Abu Salim, K.; Aiba, S.-I.; et al. Long-term carbon sink in Borneo’s forests halted by drought and vulnerable to edge effects. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, B.J.; Duffy, J.E.; Gonzalez, A.; Hooper, D.U.; Perrings, C.; Venail, P.; Narwani, A.; Mace, G.M.; Tilman, D.; Wardle, D.A.; et al. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature 2012, 486, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jucker, T.G.; Avăcăriței, D.; Bărnoaiea, I.; Duduman, G.; Bouriaud, O.; Coomes, D.A. Climate modulates the effects of tree diversity on forest productivity. J. Ecol. 2015, 104, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliffe, S.; Wirth, C.; Jucker, T.; Van Der Plas, F.; Scherer-Lorenzen, M.; Verheyen, K.; Allan, E.; Benavides, R.; Bruelheide, H.; Ohse, B.; et al. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning relations in European forests depend on environmental context. Ecol. Lett. 2017, 20, 1414–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammerant, R.; Rita, A.; Borghetti, M.; Muscarella, R. Water-limited environments affect the association between functional diversity and forest productivity. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e10406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheil, D.; Bongers, F. Interpreting forest diversity-productivity relationships: volume values, disturbance histories and alternative inferences. For. Ecosyst. 2020, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, R.A.; Muller-Landau, H.C.; Rahman, K.A.; Bebber, D.P.; Bin, Y.; Bohlman, S.A.; Bourg, N.A.; Brinks, J.; Bunyavejchewin, S.; Butt, N.; et al. Scale-dependent relationships between tree species richness and ecosystem function in forests. J. Ecol. 2013, 101, 1214–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.J.P.; Talbot, J.; Lewis, S.L.; Phillips, O.L.; Qie, L.; Begne, S.K.; Chave, J.; Cuni-Sanchez, A.; Hubau, W.; Lopez-Gonzalez, G.; et al. Diversity and carbon storage across the tropical forest biome. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 39102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyo-Rodríguez, V.; Fahrig, L. Why is a landscape perspective important in studies of primates? Am. J. Primatol. 2014, 76, 901–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewers, R.M.; Banks-Leite, C. Fragmentation Impairs the Microclimate Buffering Effect of Tropical Forests. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e58093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurance, W.F.; Camargo, J.L.; Luizão, R.C.; Laurance, S.G.; Pimm, S.L.; Bruna, E.M.; Stouffer, P.C.; Williamson, G.B.; Benítez-Malvido, J.; Vasconcelos, H.L.; et al. The fate of Amazonian forest fragments: A 32-year investigation. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinck, K.; Fischer, R.; Groeneveld, J.; Lehmann, S.; De Paula, M.D.; Pütz, S.; Sexton, J.O.; Song, D.; Huth, A. High resolution analysis of tropical forest fragmentation and its impact on the global carbon cycle. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Shi, N.; Fu, S.; Ye, W.; Ma, L.; Guan, D. Decline in Aboveground Biomass Due to Fragmentation in Subtropical Forests of China. Forests 2021, 12, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junior, C.H.L.S.; Aragão, L.E.O.C.; Anderson, L.O.; Fonseca, M.G.; Shimabukuro, Y.E.; Vancutsem, C.; Achard, F.; Beuchle, R.; Numata, I.; Silva, C.A.; et al. Persistent collapse of biomass in Amazonian forest edges following deforestation leads to unaccounted carbon losses. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz8360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, K.A.; Macdonald, S.E.; Burton, P.J.; Chen, J.; Brosofske, K.D.; Saunders, S.C.; Euskirchen, E.S.; Roberts, D.; Jaiteh, M.S.; Esseen, P.-A. Edge Influence on Forest Structure and Composition in Fragmented Landscapes. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 768–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahrig, L. Effects of Habitat Fragmentation on Biodiversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2003, 34, 487–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.C.; Fahrig, L.; Francis, C.M. Landscape size affects the relative importance of habitat amount, habitat fragmentation, and matrix quality on forest birds. Ecography 2011, 34, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villard, M.; Metzger, J.P. REVIEW: Beyond the fragmentation debate: a conceptual model to predict when habitat configuration really matters. J. Appl. Ecol. 2014, 51, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong EN, Ozor N, Sekyi-annan E (2014) Development of small dams and their impact on livelihoods: Cases from northern Ghana. African J Agric Res 9:1867–1877. [CrossRef]

- Dam J, Eijck J, Schure J, Zuzhang X (2017) The charcoal transition: greening the charcoal value chain to mitigate climate change and improve local livelihoods.

- Jose, S. Agroforestry for ecosystem services and environmental benefits: an overview. Agrofor. Syst. 2009, 76, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MESTI (2018) Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology and Innovation (Mesti) Sector Medium-Term Development Plan. Accra, Ghana.

- Hilson, G. Shootings and burning excavators: Some rapid reflections on the Government of Ghana's handling of the informal Galamsey mining ‘menace’. Resour. Policy 2017, 54, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AFR100 (2015) Peopl Restoring Africa’s Landscapes. https://afr100.org/.

- Siyum, Z.G. Tropical dry forest dynamics in the context of climate change: syntheses of drivers, gaps, and management perspectives. Ecol. Process. 2020, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aridity index (AI) values | Climate class (zones) |

|---|---|

| 0.2 ≤ AI < 0.35 | Semi-arid |

| 0.35 ≤ AI < 0.5 | Dry sub-humid |

| 0.5 ≤ AI < 0.65 | Sub-humid |

| AI ≥ 0.65 | Humid |

| Aridity class | Sample size (n) | Mean AGB (Mg ha-1) | SD (Mg ha-1) | Scheffé group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humid | 732 | 217.34 | 152.82 | a |

| Sub-humid | 202 | 70.13 | 69.61 | b |

| Dry sub-humid | 147 | 18.71 | 26.44 | c |

| Semi-arid | 124 | 7.30 | 13.83 | c |

| Model type | AIC | Fisher’s C | df | p-value | R2(AGB_cal) | R2(Frag_PC1) | R2(Richness) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear SEM | 4178.46 | 3.04 | 2 | 0.219 | 0.620 | 0.304 | 0.004 |

| Nonlinear SEM | 8130.84 | 226.34 | 18 | < 0.001 | 0.834 | 0.154 | 0.032 |

| Predictor | edf | F | P | ∆AIC | ∆Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI* | 3.71 | 13.74 | <0.001 | ‒ | ‒ |

| NP | 2.68 | 4.91 | <0.001 | 71.21 | 0.009 |

| AREA_MN | 6.95 | 46.70 | <0.001 | 386.25 | 0.043 |

| ED | 7.09 | 31.59 | <0.001 | 268.51 | 0.031 |

| MSI | 5.65 | 15.14 | <0.001 | 156.77 | 0.020 |

| LSI | 6.60 | 29.73 | <0.001 | 256.44 | 0.030 |

| Richness* | 0.60 | 0.39 | 0.052 | ‒ | ‒ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).