Submitted:

21 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

3. Materials and Methods

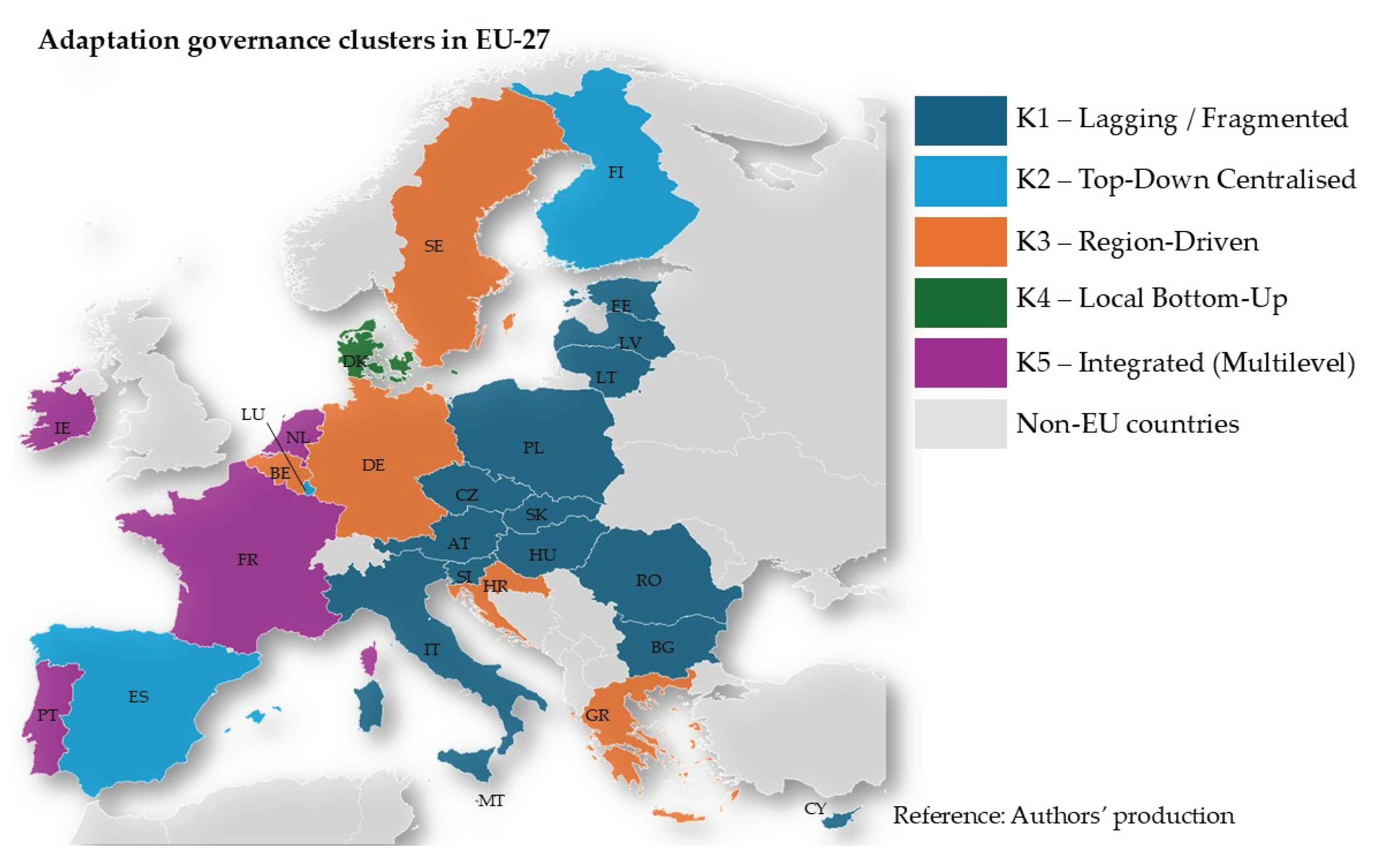

3.1. Rationale for the Five Clusters and Rule Order

- K1 – Lagging/Fragmented. Several foundational pillars are low; neither regional nor local tiers are consolidated, and the national core is not steering multilevel diffusion. Rule: count {B..I ≤ 1} ≥ 4, M ≤ 0.25, J < 2.5, C ≤ 2, D ≤ 2, L ≤ 2, and not higher classes.

- K2 – Top-Down Centralised. Robust national strategic–legal backbone with incomplete territorial diffusion and local collaboration; not yet integrated. Residual rule (after excluding K5/K3/K4/K1): J ≥ 2.5 and N < 3.

- K3 – Region-Driven. Territorial (regional) leadership precedes full national consolidation; the local tier is present but not yet scaled. Rule: C ≥ 3, D ≥ 1, K ≥ 2, J < 3, and not K5.

- K4 – Local/Urban Bottom-Up. City-led mobilisation and urban policy instruments lead, while the regional tier remains weak and the national core is moderate. Rule: L > 2 driven by at least one advanced local lever (D ≥ 3 or G ≥ 2 or I ≥ 2), C ≤ 2, J < 3, and not K5/K3.

- K5 – Integrated (Multilevel). Balanced, mature multilevel architecture in which a strong national core is coupled with mandatory or widely institutionalised sub-national layers and active local/urban integration. Rule: (i) vertical balance N ≥ 2.5; (ii) advanced local tier D ≥ 3 and urban integration G ≥ 2; (iii) regional presence C ≥ 2; (iv) advanced climate law H ≥ 3; (v) functional NAS/NAP B ≥ 2.

3.2. Coding and Verification Protocol

3.3. Limitations

4. Results

4.1. Aggregate Patterns and Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Country Archetypes

-

K1—Lagging/Fragmented (14 MS): AT, BG, CY, CZ, EE, HU, IT, LV, LT, MT, PL, RO, SK, SI.Profiles combine multiple low pillars (≥ 4 bases ≤ 1), weak national cores (J < 2.5) and thin territorial layers (C ≤ 2, D ≤ 2, L ≤ 2). N typically ≤ 1.7; positive TOP_DOWN indicates centre-led yet shallow systems. Sub-national obligations are often non-binding or absent; sectoral institutionalisation is at an early stage; LTS content tends to be narrative rather than KPI-based; urban integration is at the guidance level; and CoM leverage is generally low. These profiles do not satisfy the gates for other archetypes (not K2/K3/K4/K5 for the stated reasons). Policy priorities follow directly: mandate RAP/LAP with coverage and review clauses; upgrade LTS/NUP to binding hooks; issue stand-alone SAPs in key sectors; and scale network leverage—consistent with the non-compensatory design.

-

K2—Top-Down Centralised (3 MS): FI, LU, ES.Robust national cores (J ≥ 2.5) coexist with N < 2.5 and at least one territorial gate below K5 (often D < 3 and/or C < 2–3), typically with O = J − L > 0. Finland and Luxembourg pair strong legal backbones with voluntary or thin territorial layers; Spain is closest to K5 but remains below D ≥ 3 and N ≥ 2.5. Trajectories: convert voluntary regional/local activity into mandated RAP/LAP with coverage and review, embed binding urban-planning standards (G ≥ 3), and consolidate local ecosystem density so that N crosses 2.5.

-

K3—Region-Driven (5 MS): BE, HR, DE, EL, SE.Regional institutions are the primary engine (C ≥ 3, K ≥ 2), while the national core is non-dominant (J < 3) and N ≈ 1.7–1.9; local synergy is present but uneven (L ≈ 2.0). Progression requires binding local coverage (D ≥ 3), a stronger national legal backbone (H ≥ 3, with J rising) and tighter urban-policy mandates (G), which together move N beyond 2.5.

-

K4—Local/Urban Bottom-Up (1 MS): DK.High local synergy (L > 2) driven by mandatory LAPs with full population coverage (D = 4), weak/absent regional tier (C ≤ 2) and a non-dominant national core (J < 3), yielding N = 2.0. Progress toward K5: codify national adaptation duties (H, J), strengthen monitored urban standards (G) and consider a functional regional coordination layer (C/K).

-

K5—Integrated (Multilevel) (4 MS): FR, IE, NL, PT.Membership requires all high bars—B ≥ 2, C ≥ 2, D ≥ 3, G ≥ 2, H ≥ 3, N ≥ 2.5—so neither strong laws nor dense local activity alone suffice. These systems exhibit convergent medians across J, K, and L, and at high N, indicating balanced pillars rather than single-lever dominance. Differences at the margin (sectoral articulation E, network mobilisation I) are secondary to the rule gates.

4.3. Robustness and Sensitivity

4.4. Typologies of Adaptation Governance (Five Country Clusters)

4.4.1. Cluster 1: Lagging / Fragmented

- Austria: mature NAS/NAP, but no adaptation clauses in the Klimaschutzgesetz and voluntary Länder instruments (RAP = 1; SAP = 1; G = 1; I very low).

- Czechia: comprehensive NAS/NAP, no climate act; RAP recommendations are voluntary (RAP = 1) and LAP/CoM uptake is extremely low (LAP = 0; I ≈ 0.37%).

- Estonia: solid NAS and an LTS chapter (F = 2), but no mandated RAP/LAP/SAP and I = 0.

- Hungary: county-level strategies in the 2014–2020 EU-funding window (temporarily RAP = 2), but no binding framework at present (LAP = 1; H = 0).

- Romania, Latvia, Lithuania: adaptation embedded narratively in LTS/NUP (F ≈ 2; G ≈ 1–2), without enforceable subnational duties and with low CoM coverage.

- Italy: updated PNACC, no framework climate law; regional/local diffusion remains voluntary, and CoM coverage is moderate (approx. 8%).

- Malta: H = 4 (strong law) yet no RAP/LAP/SAP and I = 0; non-compensatory gates keep the profile in K1.

4.4.2. Cluster 2: Top-Down Centralised

- Finland: the 2022 Climate Act includes a whole adaptation chapter (H = 4) and NAS/NAP are current (B = 4); RAPs are voluntary with < 50% coverage (C = 1), LAPs are voluntary with limited diffusion (D = 1), and NUP integration is reference-level (G = 1). The result is J = 3.3, N = 1.9 and L = 1.3—insufficient for K5.

- Luxembourg: a robust Climate Law (H = 4), an operational national plan, and a strong strategy (B = 3) coexist with an absent regional tier (C = 0) and non-mandated LAPs (D = 1); despite a coherent central policy (J = 3.0), both N = 1.7 and L = 1.7 remain low.

- Spain: a consolidated NAS/NAP cycle codified in Law 7/2021 (H = 3; B = 4) and structured monitoring is accompanied by widespread yet voluntary regional/local engagement (C = 2; D = 2), G = 2, and N = 2.4—closest to K5, but still below the D ≥ 3 and N ≥ 2.5 gates.

- These profiles do not meet:

- K3 (Region-Driven): regions are not the primary engine (FI C = 1; LU C = 0; ES C = 2 with voluntary diffusion);

- K4 (Local/Urban Bottom-Up): LAPs are not mandatory with ≥ 50% coverage (D < 3) and L is moderate;

- K5 (Integrated): the joint non-compensatory gates—N ≥ 2.5 together with D ≥ 3 (and C ≥ 2, H ≥ 3, B ≥ 2, G ≥ 2)—are not simultaneously satisfied (all three cases fall short on N and D, and FI/LU also on C).

4.4.3. Cluster 3: Region-Driven

- Belgium exemplifies a constitutionally decentralised model: each Region has an autonomous, up-to-date RAP (C = 3; K = 2.5), CoM participation is very high (I = 4; L = 2.3), yet the federal core is weak (J = 1.3) and there is no national climate law on adaptation (H = 0).

- Croatia and Greece display asymmetric profiles: statutory or fully rolled-out regional planning (EL C = 4; HR C = 3; both K ≥ 2) compensates for under-powered national cores (HR J = 1.3, H = 2; EL J = 1.0, H = 1) and non-mandatory LAPs (D = 1), with mid-range N (≈ 1.7–1.8).

- Germany’s Länder drive adaptation (C = 3; K = 2.0), but the federal layer remains largely strategic (J = 1.7), with no binding national adaptation law (H = 1), no stand-alone SAPs (E = 0), limited LAP diffusion (D = 1) and very low CoM coverage (I = 0)—all of which cap L (= 1.3) and N (= 1.7).

- Sweden combines mandatory regional assignments (C = 3; K = 2.5) and strong sectoral agency plans (E = 4) with integration in urban planning (G = 3; D = 2); nonetheless, the national core is non-dominant (J = 1.3; H = 1) and N (= 1.9) remains below the integrated threshold.

4.4.4. Cluster 4: Local Bottom-Up

4.4.5. Cluster 5: Integrated (Multilevel)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NAS | National Adaptation Strategy |

| NAP | National Adaptation Plan |

| RAP | Regional Adaptation Plan |

| LAP | Local Adaptation Plan |

| LTS | Long-Term Strategy |

| NUP | National Urban Policy |

| CoM | Covenant of Mayors |

| EEA | European Environment Agency |

| EU | European Union |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Document Inventory by Member State

| Country | Document type | Full citation | Year (as stated in file) | Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | NAS | Die Österreichische Strategie zur Anpassung an den Klimawandel. Teil 1 – Kontext. Bundesministerium für Klimaschutz, Umwelt, Energie, Mobilität, Innovation und Technologie (BMK), Wien. Stand: 18. März 2024. | 2024 | German |

| NAP | Die Österreichische Strategie zur Anpassung an den Klimawandel. Teil 2 – Aktionsplan. Handlungsempfehlungen für die Umsetzung. BMK, Wien. Stand: 18. März 2024. | 2024 | German | |

| LTS | Langfriststrategie – Österreich. Periode bis 2050. Bundesministerium für Nachhaltigkeit und Tourismus, Wien, Dezember 2019. | 2019 | English | |

| LTS | Long-Term Strategy 2050 – Austria. Period through to 2050. Federal Ministry for Sustainability and Tourism, Vienna, December 2019 (As of: 1 December 2020). | 2019 | German | |

| Belgium | NAS | Belgian National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy. National Climate Commission, December 2010. | 2010 | English |

| LTS | Stratégie à long terme de la Belgique. Document fédéral, décembre 2019. | 2019 | French | |

| LTS | Belgische Langetermijnstrategie. Federaal document, december 2019. | 2019 | Dutch | |

| Federal adaptation measures (FAP) | Federale adaptatiemaatregelen 2023–2026 – Naar een klimaatbestendige samenleving in 2050. Federaal niveau. | 2023 | Dutch | |

| RAP (Flanders) | Vlaams Klimaatadaptatieplan – Vlaanderen wapenen tegen de klimaatverandering. Vlaamse overheid, depotnummer D/2022/3241/266. | 2022 | Dutch | |

| RAP (Brussels) | Plan régional Air-Climat-Énergie (PRACE). Bruxelles Environnement, Juin 2016 – Axe 7 « Adaptation ». | 2016 | French | |

| Bulgaria | NAS & NAP (strategy + action plan) | Ministry of Environment and Water (Republic of Bulgaria). National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy and Action Plan. “Final Report …” (text references 2018 context and adoption pathway). | 2018 | English |

| LTS (Long-Term Strategy) | Republic of Bulgaria. Long-term Strategy for Mobilizing Investments for Climate-friendly, Competitive and Secure Economy in the Republic of Bulgaria 2050. (document header indicates 2022). | 2022 | English | |

| Croatia | Climate law | Republic of Croatia. Zakon o klimatskim promjenama i zaštiti ozonskog sloja (Official Gazette NN 127/2019, 27.12.2019). | 2019 | Croatian |

| LTS (Long-Term Strategy / Low-carbon strategy) | Republika Hrvatska, Ministarstvo gospodarstva i održivog razvoja. Strategija niskougljičnog razvoja Republike Hrvatske do 2030. s pogledom na 2050. godinu (nacrt, Zagreb, lipanj 2021). | 2021 | Croatian | |

| NUP (National Urban Policy / Spatial planning strategy) | Republic of Croatia. Spatial Development Strategy of the Republic of Croatia (Zagreb, 2017). | 2017 | English | |

| Cyprus | NAS (National Adaptation Strategy) | Republic of Cyprus, Department of Environment, Ministry of Agriculture, Rural Development and Environment. National Adaptation Strategy to Climate Change. Nicosia, 2017. | 2017 | English |

| NAP (National Adaptation Plan) | Υπουργείο Γεωργίας, Aγροτικής Aνάπτυξης και Περιβάλλοντος. Σχέδιο Δράσης Προσαρμογής στην Κλιματική Aλλαγή (Παράρτημα ΙΙ του CYPADAPT). Λευκωσία, 2017. | 2017 | Greek | |

| LTS (Long-Term Low GHG Emission Development Strategy) | Department of Environment, Ministry of Agriculture, Rural Development and Environment. Cyprus’ Long-Term Low Greenhouse Gas Emission Development Strategy – 2022 Update. Nicosia, September 2022. | 2022 | English | |

| Czechia | NAS (National Adaptation Strategy) | Ministerstvo životního prostředí České republiky. Strategie přizpůsobení se změně klimatu v podmínkách České republiky – 1. aktualizace pro období 2021–2030. Prague: Ministerstvo životního prostředí, 2021. | 2021 | Czech |

| NAP (National Adaptation Plan) | Ministerstvo životního prostředí České republiky. Národní akční plán adaptace na změnu klimatu – 1. aktualizace pro období 2021–2025. Prague: Ministerstvo životního prostředí, 2021. | 2021 | Czech | |

| NUP (National Urban Policy) | Ministerstvo pro místní rozvoj České republiky. Zásady urbánní politiky – Aktualizace 2017. Prague: MMR ČR, 2017. | 2017 | Czech | |

| LTS (Long-Term Strategy / Low-Emission Strategy) | Ministerstvo životního prostředí České republiky. Politika ochrany klimatu v České republice. Prague: Ministerstvo životního prostředí, 2017. | 2017 | Czech | |

| Denmark | NAS (National Adaptation Strategy) | Regeringen. Strategi for tilpasning til klimaændringer i Danmark. Copenhagen: Energistyrelsen, March 2008. ISBN 978-87-7844-719-7. | 2008 | Danish |

| NAP (National Adaptation Plan) | Regeringen, Miljøministeriet. Handlingsplan for klimatilpasning i Danmark. Copenhagen, 2012. | 2012 | Danish | |

| LTS (Long-Term Strategy / Low GHG Emission Development Strategy) | Ministry of Climate, Energy and Utilities. Denmark’s Long-Term Strategy for Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Copenhagen, 2020. | 2020 | English | |

| NUP (National Urban Policy / Spatial Planning Act) | Ministry of the Environment. The Planning Act in Denmark: Consolidated Act No. 813 of 21 June 2007. Copenhagen: Ministry of the Environment, 2007. ISBN 978-87-7279-795-3. | 2007 | English | |

| Estonia | LTS | Government of the Republic of Estonia. General Principles of Climate Policy until 2050. English version (LTS submitted to the EU). | 2017 | English |

| NAS/NAP | Ministry of the Environment (Republic of Estonia). Development Plan for Climate Change Adaptation until 2030 (with Implementation Plan 2017–2020). | 2017 | English | |

| NUP (National Urban Policy / Territorial Development Plan) | Republic of Estonia, Ministry of Finance. Territoriaalse tegevuskava 2030 atlas – Euroopa territoriaalse arengu kaardid. Tallinn: Ministry of Finance, 2021. Source: www.bmi.bund.de (European Territorial Development Atlas). | 2021 | Estonian | |

| Finland | NAS | Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. Finland’s National Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change. Helsinki: Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, 2005. | 2005 | English |

| NAP | Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. Finland’s National Climate Change Adaptation Plan 2022. Government Resolution 20 November 2014. Publications of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry 5b/2014. ISBN 978-952-453-862-6. | 2014 | English | |

| LTS | Työ- ja elinkeinoministeriö (Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment). Suomen pitkän aikavälin strategia kasvihuonekaasujen vähentämiseksi. Helsinki, 2020. | 2020 | Finnish | |

| CRA (Climate Risk Assessment) | Finnish Meteorological Institute. National Climate Change Risk Assessment for Finland – 2022 Update. Helsinki: FMI, 2022. | 2022 | English | |

| RAP | Centre for Economic Development, Transport and the Environment (ELY Centres). Regional Adaptation Plans for Climate Change – Finland’s Regional Climate Work Framework. Helsinki, 2022. | 2022 | English | |

| Climate Law | Parliament of Finland. Ilmastolaki (Climate Act) 423/2022. Helsinki: Finlex Data Bank. Available online: https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/2022/20220423. | 2022 | Finnish | |

| France | LTS | Ministère de la Transition Écologique. Stratégie Nationale Bas-Carbone (SNBC). Mars 2020. | 2020 | French |

| NAS | ONERC – Observatoire national sur les effets du réchauffement climatique. Stratégie nationale d’adaptation au changement climatique. (La stratégie et ses éclairages sectoriels.) | 2007 | French | |

| NAP | Ministère de la Transition Écologique et Solidaire. Plan national d’adaptation au changement climatique 2018–2022 (PNACC-2). | 2018 | French | |

| Germany | NAS | Federal Government of Germany. Deutsche Anpassungsstrategie an den Klimawandel (German Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change). Adopted by the Federal Cabinet on 17 December 2008. | 2008 | German |

| NAP | Federal Government of Germany. Aktionsplan Anpassung der Deutschen Anpassungsstrategie an den Klimawandel (Action Plan for the German Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change). Adopted by the Federal Cabinet on 31 August 2011. | 2011 | German | |

| LTS | Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU). Langfristige Klimaschutzstrategie Deutschlands (Long-Term Climate Strategy of Germany). Submitted to the European Commission, Berlin. | 2020 | German | |

| Progress Report | Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und nukleare Sicherheit. Fortschrittsbericht zur Deutschen Anpassungsstrategie an den Klimawandel (Progress Report on the German Adaptation Strategy to Climate Change). Berlin: BMU, 2015. | 2015 | German | |

| NUP | Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat. Nationales Umsetzungsprogramm zur Territorialen Agenda 2030. Berlin: BMI, 2021. | 2021 | German | |

| Greece | NAS | Ministry of Environment and Energy (MEEN). National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy (NAS) of Greece. Athens: MEEN, 2016. | 2016 | Greek |

| LTS | Ministry of Environment and Energy. Long-Term Strategy for 2050 (LTS) – National Energy and Climate Plan. Athens, 2019. | 2019 | Greek | |

| NC / BR | Hellenic Republic, Ministry of Environment and Energy. 8th National Communication and 5th Biennial Report under the UNFCCC. Athens: MEEN, December 2022. | 2022 | English | |

| NUP | Ministry of Environment and Energy. National Implementation Programme for the Territorial Agenda 2030. Athens, 2021. | 2021 | Greek | |

| Hungary | NAS | Ministry of Agriculture. Nemzeti Alkalmazkodási Stratégia (National Adaptation Strategy) 2018–2030, with Outlook to 2050. Budapest: Ministry of Agriculture, 2018. | 2018 | Hungarian |

| LTS | Ministry for Innovation and Technology (ITM). Nemzeti Tiszta Fejlődési Stratégia 2020–2050 (National Clean Development Strategy 2020–2050). Budapest: ITM, 2021. | 2021 | Hungarian | |

| Ireland | NAS/NAP | Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications. National Adaptation Framework – Planning for a Climate Resilient Ireland. Dublin: DECC, 2024. | 2024 | English |

| LTS | Government of Ireland. Ireland’s Long-Term Strategy on Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction. Dublin: DECC, 2024. | 2024 | English | |

| Climate Law | Government of Ireland. Climate Action and Low Carbon Development Act 2015 (No. 46 of 2015); Amendment Act 2021 (No. 32 of 2021). Dublin: Government Publications. | 2015 / 2021 | English | |

| NUP | Government of Ireland, Department of Housing, Local Government and Heritage. National Planning Framework – First Revision. Dublin: DHLGH, April 2025. | 2025 | English | |

| Italy | NAS/NAP | Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare (MATTM). Strategia Nazionale di Adattamento ai Cambiamenti Climatici (SNAC). Rome: MATTM, 2015. | 2015 | Italian |

| LTS | Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Tutela del Territorio e del Mare, Ministero dello Sviluppo Economico, Ministero delle Infrastrutture e dei Trasporti, Ministero delle Politiche Agricole, Alimentari e Forestali. Strategia Italiana di Lungo Termine sulla Riduzione delle Emissioni dei Gas a Effetto Serra. Rome: Governo Italiano, 2021. | 2021 | Italian | |

| National Report (NC/BR) | Government of Italy. Seventh National Communication and Third Biennial Report under the UNFCCC. Rome: Ministry for the Environment, Land and Sea, 2021. | 2021 | English | |

| Technical Report | SNPA – Sistema Nazionale per la Protezione dell’Ambiente. Rapporto sugli Indicatori di Impatto dei Cambiamenti Climatici – Edizione 2021 (Report SNPA 21/2021). Rome: ISPRA, 2021. | 2021 | Italian | |

| Latvia | NAS/NAP | Ministry of Environmental Protection and Regional Development (VARAM). Latvian National Plan for Adaptation to Climate Change until 2030. Riga: VARAM, 2019. | 2019 | English |

| LTS | Vides aizsardzības un reģionālās attīstības ministrija (VARAM). Latvijas stratēģija klimatneitralitātes sasniegšanai līdz 2050. gadam (Latvia’s Strategy for Achieving Climate Neutrality by 2050). Riga: Ministry of Environmental Protection and Regional Development, 2019. | 2019 | Latvian | |

| NUP | Ministry of Environmental Protection and Regional Development (VARAM). National Development Plan of Latvia for 2021–2027. Riga: VARAM, 2020. | 2020 | English | |

| Lithuania | NAS/NAP | Ministry of Environment of the Republic of Lithuania. National Strategy for Climate Change Management Policy (Nacionalinė klimato kaitos valdymo politikos strategija). Vilnius: Ministry of Environment, 2012 (updated 2019). | 2019 | Lithuanian |

| NECP | Government of the Republic of Lithuania. National Energy and Climate Action Plan for 2021–2030. Vilnius: Ministry of Energy, 2019. | 2019 | English | |

| LTS | Lietuvos Respublikos Energetikos Ministerija. Lietuvos ilgos trukmės strategija iki 2050 m. dėl mažai anglies dioksido išskiriančios ekonomikos (Lithuania’s Long-Term Strategy for a Low-Carbon Economy until 2050). Vilnius: Ministry of Energy, 2021. | 2021 | Lithuanian | |

| NUP | Government of the Republic of Lithuania. National Progress Plan for 2021–2030 (Nacionalinis pažangos planas). Vilnius: Government of Lithuania, 2020. | 2020 | Lithuanian | |

| Luxembourg | NAS/NAP | Ministère de l’Environnement, du Climat et du Développement durable. Stratégie et plan d’action pour l’adaptation aux effets du changement climatique au Luxembourg 2018–2023. Luxembourg: Gouvernement du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg, 2018. | 2018 | French |

| LTS | Gouvernement du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg. Stratégie nationale à long terme en matière d’action climat « Vers la neutralité climatique en 2050 ». Octobre 2021. | 2021 | French | |

| Climate Law | Journal officiel du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg. Loi du 15 décembre 2020 relative au climat (modifiant la loi modifiée du 31 mai 1999 instituant un fonds pour la protection de l’environnement), A994, Luxembourg: Gouvernement du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg, 2020. | 2020 | French | |

| Malta | LTS | Government of Malta. Long-Term Strategy for Malta’s Climate Neutrality by 2050, Valletta: Ministry for the Environment, Energy and Enterprise, 2023. | 2023 | English |

| Climate Law | Government of Malta. Climate Action Act (CAP. 543), Laws of Malta, Ministry for the Environment, Sustainable Development and Climate Change, Valletta, 2015. | 2015 | English | |

| National Spatial/Planning Strategy | Government of Malta. Strategic Plan for the Environment and Development (SPED), Planning Authority, Valletta, 2015. | 2015 | English | |

| Netherlands | LTS | Government of the Netherlands. Langetermijnstrategie Klimaat (Long-Term Strategy). The Hague: Government of the Netherlands, 2019. | 2019 | Dutch |

| Other (Adaptation Communication) | Government of the Netherlands, Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management. Adaptation Communication of the Netherlands. The Hague, 2021. Submission date: October 2021. | 2021 | English | |

| Poland | NAS/NAP | Ministry of the Environment of the Republic of Poland. Strategic Adaptation Plan for Sectors and Areas Vulnerable to Climate Change in Poland until 2020, with a perspective until 2030 (SPA 2020). Warsaw: Ministry of the Environment, 2013. | 2013 | Polish / English (summary available) |

| Portugal | NAS/NAP | Government of Portugal. Resolução do Conselho de Ministros n.º 56/2015 — Quadro Estratégico para a Política Climática (QEPiC), Programa Nacional para as Alterações Climáticas 2020/2030 (PNAC 2020/2030) e Estratégia Nacional de Adaptação às Alterações Climáticas (ENAAC 2020). Diário da República, 1.ª série, n.º 147, 30 July 2015. | 2015 | Portuguese |

| LTS | Government of Portugal, Ministry of the Environment and Energy Transition. Roadmap for Carbon Neutrality 2050 (RNC2050): Long-Term Strategy for Carbon Neutrality of the Portuguese Economy by 2050. Lisbon, 2019. | 2019 | English | |

| Climate Law | Government of Portugal. Lei de Bases do Clima (Climate Framework Law). Lei n.º 98/2021, Diário da República, 1.ª série, n.º 239, 10 December 2021. | 2021 | Portuguese | |

| NUP | Government of Portugal, Direção-Geral do Território. Programa Nacional da Política de Ordenamento do Território (PNPOT). Lisbon, 2019. | 2019 | Portuguese | |

| Romania | LTS | Long Term Strategy of Romania. Prepared for the Ministry of Energy and the Ministry of Environment, Waters and Forests by PwC; current version elaborated 23 Apr 2023 and presented to CISC 24 Apr 2023 (public consultation launched 18 Apr 2023).. | 2023 | English |

| Slovakia | NUP | The Urban Development Policy of the Slovak Republic by 2030 (short version). Ministry of Transport and Construction; Government Resolution no. 5/2018 of 10 January 2018. | 2018 | English |

| LTS | Low-Carbon Development Strategy of the Slovak Republic until 2030 with a View to 2050. Ministry of Environment of the Slovak Republic (draft, November 2019). | 2019 | English | |

| NAP | Akčný plán pre implementáciu Stratégie adaptácie SR na zmenu klímy. Ministerstvo životného prostredia SR, August 2021. | 2021 | Slovak | |

| LTS | Resolucija o dolgoročni podnebni strategiji Slovenije do leta 2050 (ReDPS50). Državni zbor, sprejeta 13. julija 2021. | 2021 | Slovenian | |

| NAS | Strateški okvir prilagajanja podnebnim spremembam. Vlada Republike Slovenije, december 2016. | 2016 | English | |

| NUP | Spatial Management Policy of the Republic of Slovenia. Government of the Republic of Slovenia, adopted December 20, 2001. | 2001 | English | |

| Spain | Climate Law | Government of Spain. Law 7/2021, of 20 May, on Climate Change and Energy Transition. | 2021 | Spanish |

| NAS | Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico (MITECO). Plan Nacional de Adaptación al Cambio Climático 2021–2030 (PNACC 2021–2030). | 2021 | Spanish | |

| NAP | Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico (MITECO). Climate Change Adaptation: Work Programme 2021–2025 (Programa de Trabajo 2021–2025 del PNACC). | 2021 | Spanish | |

| SAP | ADIF – Administrador de Infraestructuras Ferroviarias. Climate Change Plan 2018–2030 (Plan de Cambio Climático 2018–2030). | 2018 | Spanish | |

| SAP | Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico (MITECO). Adaptation Strategy for the Spanish Coast (Estrategia de Adaptación de la Costa al Cambio Climático). | NA | Spanish | |

| SAP | Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico (MITECO). Strategic Guidelines on Water and Climate Change (Directrices Estratégicas en materia de agua y cambio climático). | NA | Spanish | |

| Sweden | NAS | Nationell strategi för klimatanpassning (Prop. 2017/18:163). Government of Sweden. | 2018 | Swedish |

| LTS | Sveriges långsiktiga strategi för minskning av växthusgasutsläppen. Ministry of the Environment. | 2019 | Swedish | |

| NUP | Voluntary National Review – New Urban Agenda (Sweden). Ministry of Finance; Boverket. | 2021 | Swedish | |

| SAP | Handlingsplan för klimatanpassning 2022–2025. Socialstyrelsen. | 2022 | Swedish | |

| RAP | Regional plan för klimatanpassning i Dalarna (Rapport 2021:09). Länsstyrelsen Dalarnas län. | 2021 | Swedish | |

| RAP | Regional handlingsplan för klimatanpassning i Västernorrlands län (Rapport 2018:01). Länsstyrelsen Västernorrland. | 2018 | Swedish | |

| RAP | Anpassning till ett förändrat klimat – Blekinges regionala handlingsplan (2014:12). Länsstyrelsen Blekinge län. | 2014 | Swedish | |

| RAP | Regional handlingsplan för klimatanpassning i Gotlands län 2018–2020 (uppdaterad 2019-04-04). Länsstyrelsen Gotlands län. | 2018 (upd. 2019) | Swedish | |

| RAP | Regional handlingsplan för klimatanpassning i Gävleborgs län (2014:11). Länsstyrelsen Gävleborg. | 2014 | Swedish |

Appendix B. Data, Descriptive Statistics and Diagnostic Visualisations

Appendix B.1. Excel Implementation of the Rule-Based Classifier

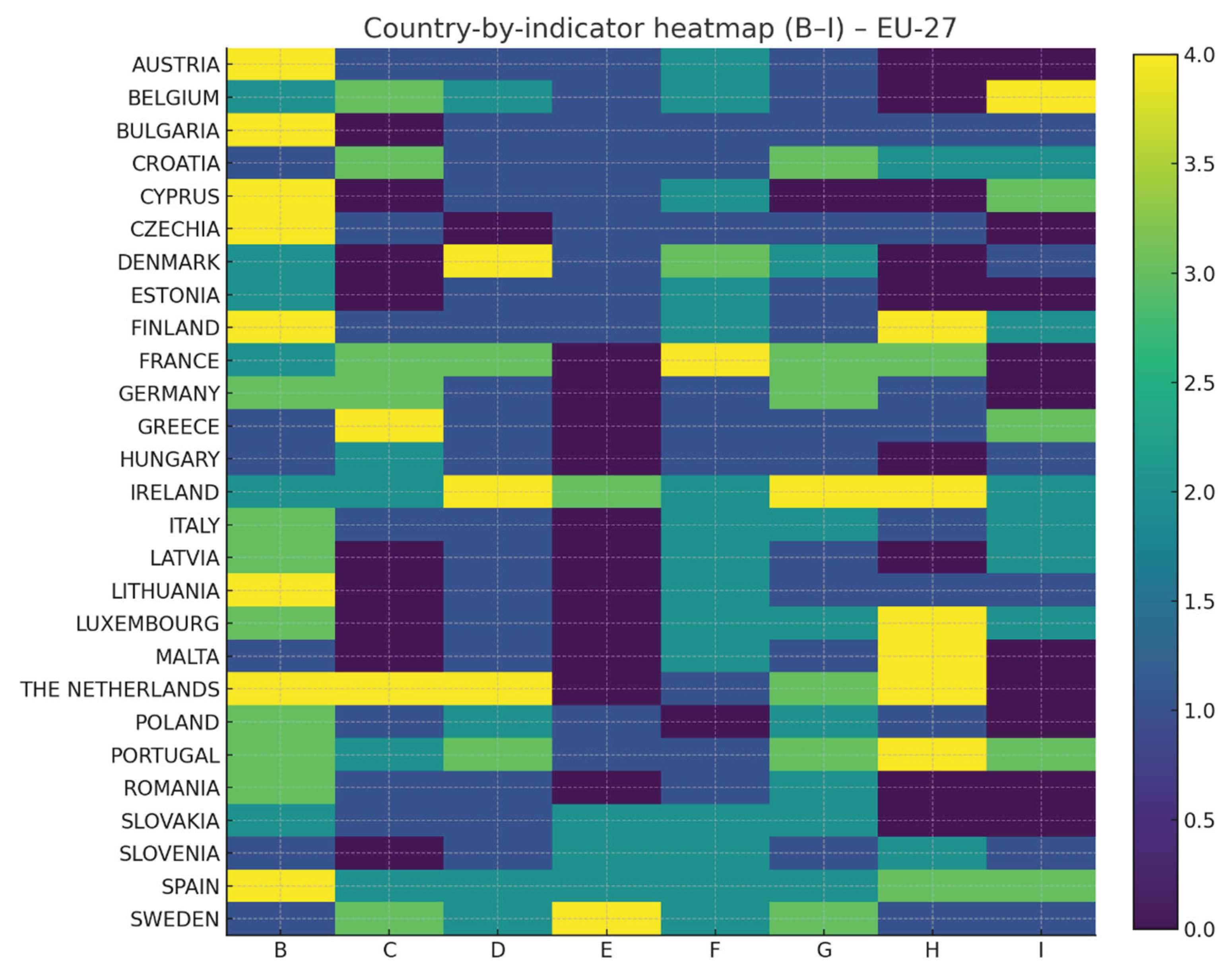

Appendix B.2. Descriptive Statistics for Base Indicators (B–I)

| Indicator | N (countries) | Median | IQR | 0 (%) | 1 (%) | 2 (%) | 3 (%) | 4 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (NAS/NAP) | 27 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 14.8 | 40.7 | 37.0 | 7.4 |

| C (RAPs) | 27 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 25.9 | 33.3 | 22.2 | 18.5 | 0.0 |

| D (LAPs) | 27 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 66.7 | 11.1 | 18.5 | 3.7 |

| E (SAPs) | 27 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 22.2 | 70.4 | 3.7 | 0.0 | 3.7 |

| F (LTS, adaptive) | 27 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 3.7 | 33.3 | 55.6 | 7.4 | 0.0 |

| G (NUP integration) | 27 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 3.7 | 37.0 | 40.7 | 18.5 | 0.0 |

| H (Climate Law, adaptation) | 27 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 22.2 | 25.9 | 14.8 | 18.5 | 18.5 |

| I (CoM coverage) | 27 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 33.3 | 40.7 | 18.5 | 3.7 | 3.7 |

Appendix B.3. Descriptive Statistics for Composite Indices (J–P)

| Code | Index (short name) | Theoretical range | N | Median | IQR | Observed min | Observed max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | NAT_CORE (National core strength) | 0–4 | 27 | 1.70 | 1.00 | 0.70 | 3.30 |

| K | TERR_MAN (Territorial mandate) | 0–4 | 27 | 1.50 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 4.00 |

| L | LSS / URB_SYNERGY (Local collaboration) | 0–4 | 27 | 1.30 | 1.00 | 0.30 | 3.30 |

| M | ADV_SCORE (Share of pillars ≥ 3) | 0–1 | 27 | 0.10 | 0.25 | 0.00 | 0.60 |

| N | MULTI_INT (Multilevel integration) | 0–4 | 27 | 1.70 | 0.73 | 0.80 | 3.10 |

| O | TOP_DOWN (J − L) | −4 to 4 | 27 | +0.30 | — | −1.70 | +2.00 |

| P | BOTTOM_UP (L − J) | −4 to 4 | 27 | −0.30 | — | −2.00 | +1.00 |

Appendix B.4. Country-by-Indicator Heatmaps

Appendix C. Robustness and Sensitivity Analysis

Appendix C.1. Document Inventory by Member State

| Scenario ID | Change vs. baseline | Rationale tested | Countries reclassified (n) | Reclassification details | Adjusted Rand Index vs. baseline | % stable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Zero-penalty on N (−0.25 if any base = 0) | Non-compensatory stress (penalises zero pillars) | 0 | — | 1.00 | 100 |

| S2 | N threshold stricter: 2.75 (vs. 2.50) | Tougher integration bar for K5 | 0 | — | 1.00 | 100 |

| S3 | N threshold loser: 2.25 (vs. 2.50) | Easier integration bar for K5 | 0 | — | 1.00 | 100 |

| S4 | Tiebreakers inverted (J before N) | Sensitivity to tie resolution | 0 | — | 1.00 | 100 |

References

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Europe’s Changing Climate Hazards: State of Play 2023; EEA Report No. 04/2023; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, Luxembourg, 2023.

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2022. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/ (accessed in July 2024).

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Urban Adaptation in Europe: How Cities and Towns Respond to Climate Change; EEA Report No. 12/2020; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, Luxembourg, 2020.

- Amundsen, H.; Berglund, F.; Westskog, H. Overcoming barriers to climate change adaptation: A question of multilevel governance? Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 2010, 28, 276–289. [CrossRef]

- Rayner, T. Adaptation to climate change: EU policy on a Mission towards transformation? npj Climate Action 2023, 2, 36. [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Scales of governance and environmental justice for adaptation to climate change. Global Environmental Change 2001, 11, 379–389.

- Clar, C.; Prutsch, A.; Steurer, R. Barriers and guidelines for public policies on climate change adaptation: A missed opportunity of scientific knowledge-brokerage. Natural Resources Forum 2013, 37, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy. The Multilevel Climate Action Playbook for Local and Regional Governments: Second Edition; Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. Available online: https://www.globalcovenantofmayors.org/multilevel-climate-action-playbook-second-edition/ (accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Betsill, M.M.; Bulkeley, H. Cities and the multilevel governance of global climate change. Global Governance 2006, 12, 141–159. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, A.; Feichtinger, J.; Steurer, R. The governance of climate change adaptation in ten OECD countries: Challenges and approaches. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 2012, 14, 279–304. [CrossRef]

- Gilissen, H.K.; Alexander, M.; Beyers, J.-C.; Chmielewski, P.; Matczak, P.; Schellenberger, T.; Suykens, C. Bridges over troubled waters: An interdisciplinary framework for evaluating the interconnectedness within fragmented domestic flood risk management systems. Journal of Water Law 2016, 25(1), 12–26.

- European Commission. Forging a Climate-Resilient Europe: The New EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change; COM(2021) 82 final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 June 2021 establishing the framework for achieving climate neutrality (European Climate Law). Official Journal of the European Union 2021, L243/1 (9 July 2021).

- Füssel, H.-M. Adaptation planning for climate change: Concepts, assessment approaches, and key lessons. Sustainability Science 2007, 2, 265–275. [CrossRef]

- Smit, B.; Burton, I.; Klein, R.J.T.; Street, R. The science of adaptation: A framework for assessment. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 2000, 4, 199–213. [CrossRef]

- Termeer, C.J.A.M.; Dewulf, A.; Biesbroek, R. Transformational change: Governance interventions for climate change adaptation from a continuous change perspective. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2017, 60, 558–576. [CrossRef]

- Mees, H.L.P. Local governments in the driving seat? A comparative analysis of public and private responsibilities for adaptation to climate change in European and North American cities. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 2017, 19, 374–390. [CrossRef]

- Runhaar, H.A.C.; Uittenbroek, C.J.; van Rijswick, H.F.M.W.; Mees, H.L.P.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Gilissen, H.K. Prepared for climate change? A method for the ex-ante assessment of formal responsibilities for climate adaptation in specific sectors. Regional Environmental Change 2016, 16, 1389–1400. [CrossRef]

- Juhola, S.; Westerhoff, L. Challenges of adaptation to climate change across multiple scales: A case study of network governance in two European countries. Environmental Science & Policy 2011, 14, 239–247. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; COM(2019) 640 final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Biesbroek, G.R.; Swart, R.J.; Carter, T.R.; Cowan, C.; Henrichs, T.; Mela, H.; Morecroft, M.D.; Rey, D. Europe adapts to climate change: Comparing national adaptation strategies. Global Environmental Change 2010, 20, 440–450. [CrossRef]

- Reckien, D.; Salvia, M.; Heidrich, O.; Church, J.M.; Pietrapertosa, F.; De Gregorio-Hurtado, S.; D’Alonzo, V.; Foley, A.; Simões, S.G.; Krkoška Lorencová, E. How are cities planning to respond to climate change? Assessment of local climate plans from 885 cities in the EU-28. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 191, 207–219. [CrossRef]

- Massey, E.; Biesbroek, R.; Huitema, D.; Jordan, A. Climate policy innovation: The adoption and diffusion of adaptation policies across Europe. Global Environmental Change 2014, 29, 434–443. [CrossRef]

- Termeer, C.J.A.M.; van Buuren, A.; Dewulf, A.; Huitema, D.; Mees, H.L.P.; Meijerink, S.; van Rijswick, M. Governance arrangements for the adaptation to climate change. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science; Oxford University Press: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2017.

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Advancing towards Climate Resilience in Europe: Status of Reported National Adaptation Actions in 2021; EEA Report No. 11/2022; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022. [CrossRef]

- European Commission; European Environment Agency (EEA). Climate-ADAPT Platform: Sharing Knowledge for a Climate-Resilient Europe. Available online: https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu (accessed in July 2024).

- Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment; London School of Economics (LSE). Climate Change Laws of the World Database. Available online: https://climate-laws.org (accessed in July 2024).

- Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy. Covenant of Mayors Official Website. Available online: https://www.covenantofmayors.eu (accessed in July 2024).

- UN-Habitat. Urban Policy Platform. Available online: https://urbanpolicyplatform.org (accessed in July 2024).

- World Resources Institute; Climate Watch. Climate Watch Platform. Available online: https://www.climatewatchdata.org (accessed in July 2024).

- Rauken, T.; Mydske, P.K.; Winsvold, M. Climate change adaptation through municipal planning in Norway: The importance of reforming the planning system. Local Environment 2015, 20, 408–423. [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C. Mainstreaming ecosystem-based adaptation: Transformation toward sustainability in urban governance and planning. Ecology and Society 2015, 20(2), 30. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- OECD; Joint Research Centre (JRC). Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2008.

- OECD. Measuring Progress in Adapting to a Changing Climate; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024.

- UNFCCC Adaptation Committee. Monitoring and Evaluation of Adaptation at the National and Subnational Levels: Technical Paper; UNFCCC: Bonn, Germany, 2023.

- OECD; UN-Habitat; Cities Alliance. Global State of National Urban Policy 2021: Achieving Sustainable Development Goals and Delivering Climate Action; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2021.

- Melica, G.; Treville, A.; Franco De Los Rios, C.; Palermo, V.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Baldi, M.G.; Ulpiani, G.; Ortega Hortelano, A.; Barbosa, P.; Bertoldi, P. Covenant of Mayors: 2022 Assessment – Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation at Local Level; EUR 31291 EN; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy (GCoM). Common Reporting Framework – Guidance Note; GCoM: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Becker, J.; Knackstedt, R.; Pöppelbuß, J. Developing maturity models for IT management: A procedure model and its application. Business & Information Systems Engineering 2009, 1(3), 213–222. [CrossRef]

- Pöppelbuß, J.; Röglinger, M. What makes a useful maturity model? A framework of general design principles for maturity models and its demonstration in BPM. In Proceedings of the 19th European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS 2011); Helsinki, Finland, 2011.

- Neuendorf, K.A. The Content Analysis Guidebook, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017.

- UNFCCC. Updated Technical Guidelines for National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) (Draft, July 2025); UNFCCC secretariat: Bonn, Germany, 2025.

- Davide, M.; Bastos, J.; Bezerra, P.; Hernandez Moral, G.; Palermo, V.; et al. How to Develop a Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plan (SECAP) – Covenant of Mayors Guidebook – Main Document; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2025. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Glossary of Climate Change Terms. Available online: https://unfccc.int (accessed in July 2024).

- Global Green Growth Institute (GGGI). Identifying Good Practices in National Adaptation Plans: A Global Review (GGGI Technical Report No. 36); Global Green Growth Institute: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2024.

- Hooghe, L.; Marks, G. Unravelling the central state, but how? Types of multi-level governance. American Political Science Review 2003, 97(2), 233–243. [CrossRef]

- Bache, I.; Flinders, M. (Eds.). Multi-level Governance; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004.

- Eurostat. Population on 1 January by Age and Sex (Provisional 2024). Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat (accessed in July 2025).

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Chapter 14 — North America; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/chapter/chapter-14/ (accessed in October 2025).

- Craig, R.K. Climate adaptation law and policy in the United States. Frontiers in Marine Science 2022, 9, 1059734. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. Multilevel climate governance, anticipatory adaptation, and county-level resilience in the United States. Review of Policy Research 2021, 38, 675–697. [CrossRef]

- Tietjen, B.; et al. Progress and gaps in U.S. adaptation policy at the local level. Global Environmental Change 2024, 84, 102912. [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Chapter 10 — Asia; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. Available online (PDF): https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGII_Chapter10.pdf (accessed in October 2025).

- OECD. Climate Change Risks and Adaptation: Linking Policy and Economics; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. From Risk to Resilience: Helping People and Firms Adapt in South Asia; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/sar/publication/from-risk-to-resilience-helping-people-and-firms-adapt-in-south-asia (accessed in October 2025).

- OECD; Asian Development Bank (ADB). Multi-Level Governance and Subnational Finance in Asia and the Pacific; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2023.

- Fujita, T.; et al. Unravelling the challenges of Japanese Local Climate Change Adaptation Centres. Urban Climate 2023, 49, 101464. [CrossRef]

- OECD. A Territorial Approach to Climate Action and Resilience in Japan (TACAR); OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; et al. Deeper understanding of the barriers to national climate adaptation policy in South Korea. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 2023, 28, 97. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). Republic of Korea: Adaptation Strategy to Climate Change (Country Overview); UNDRR/PreventionWeb, 2022. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/ (accessed in October 2025).

- UNEP. Adaptation Gap Report 2023: Under-financed. Under-prepared. United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2023. Available online (PDF): https://www.unep.org/resources/adaptation-gap-report-2023 (accessed in October 2025).

- European Investment Bank (EIB); World Bank; Asian Development Bank; et al. Joint Report on Multilateral Development Banks’ Climate Finance 2022; 2023. Available online: https://www.eib.org/en/publications/mdb-joint-report-2022 (accessed in October 2025).

| Code | Indicator | Scale and decision rule (0–4) | Typical evidence sources | Key sources for thresholds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | National Adaptation Strategy / Plan (NAS / NAP) | 0: none. 1: only NAS, or NAS/NAP obsolete (≥10 years). 2: NAS+NAP exists but are outdated (7–9 years) or lack indicators/costing. 3: revised ≤6 years, formally adopted, with indicators and responsibility mapping. 4: revision ≤5 years, dedicated budget/finance lines, a monitoring framework, and a mandatory review cycle. | Official NAS/NAP texts and adoption decrees (national gazette/official journal); consolidated versions on competent ministry portals; Climate-ADAPT country profiles and document library (for version cross-checks). | Anchoring on iterative NAP design, M&E features (indicators, finance, review) and EU governance cycles: UNFCCC NAP guidance [43]; UNFCCC AC M&E [36]; OECD measurement/monitoring principles [35]; EU Adaptation Strategy & Climate Law [12,13]. |

| C | Regional Adaptation Plans (RAPs) | 0: none. 1: voluntary/pilots in <50% of regions. 2: stand-alone RAPs with ≥50% coverage but non-binding or outdated. 3: mandatory RAP in all regions or ≥50% with funding conditionality; updated ≤6 years. 4: mandatory, budgeted, monitored, explicitly aligned with NAS/NAP (vertical link). | Regional laws/strategies and implementing decrees (regional official bulletins); regional budget/monitoring provisions; national framework decrees on RAP mandates; Climate-ADAPT country pages (coverage cross-check). | Territorialisation and vertical coherence; mandate, resourcing and monitoring: EEA evidence on regionalisation [1,3,25]; EU strategic framing [12]; OECD & UNFCCC M&E guidance [35,36]. |

| D | Local Adaptation Plans (LAPs) | 0: none. 1: voluntary/pilot in <25% of municipalities. 2: stand-alone but non-binding or 25–50% population coverage. 3: mandatory with reporting; ≥50% population; updated ≤6 years. 4: mandatory; ≥75% population; KPIs + dedicated finance. | Municipal council resolutions and plan texts; national inventories of municipal climate plans (where available); SECAPs on the Covenant of Mayors platform; guidance/mandates from the national urban ministry. | Local planning standards, reporting architecture and diffusion tiers: Global State of National Urban Policy [37]; GCoM Common Reporting Framework & 2025 SECAP Guidebook [39,44]; JRC assessment of CoM diffusion [38]; OECD & UNFCCC M&E features [35,36]. |

| E | Sectoral Adaptation Plans (SAPs) | 0: none. 1: voluntary SAP in <2 sectors. 2: ≥2 stand-alone SAPs, non-binding. 3: binding SAP in key sectors or comprehensive sector updates ≤6 years with KPIs. 4: binding in ≥4 sectors with KPIs, resources, and periodic review. | Sector-ministry strategies/ordinances (water, health, agriculture, transport, infrastructure, coastal); parliamentary acts and implementing regulations (official journal); national adaptation M&E reports and budget laws/appropriations. | Sectoral breadth, binding force, KPIs and review cycles: EEA status of sectoral adaptation [25] (with document corroboration via Climate-ADAPT where relevant [26]); GGGI NAP good practices [46]; OECD & UNFCCC on resourcing and periodic review [35,36] |

| F | Adaptive content in Long--Term Strategy (LTS) | 0: no LTS / mitigation-only. 1: passing mention of adaptation. 2: dedicated chapter, no KPIs. 3: targets/timeline + explicit linkage to NAS/NAP. 4: monitoring, five-year review cycle, budget, and explicit multilevel coordination. | UNFCCC LTS registry and EU submissions under Reg. (EU) 2018/1999; government climate/energy strategy portals (latest version); legal instruments integrating LTS provisions (where applicable). | Iterative long-term planning, institutional capacity and EU cyclic governance: UNFCCC NAP/LTS guidance [43]; OECD on review cycles and capability [35]; EU Adaptation Strategy & Climate Law [12,13]. |

| G | Integration in National Urban Policy (NUP) | 0: no NUP / mitigation-only. 1: brief reference. 2: clear adaptation section. 3: binding guidance/standards for local plans. 4: mandatory standards + monitoring & finance for resilient urban projects. | National urban/spatial planning acts and policy white papers (official journal); implementation guidelines/circulars of the competent ministry; UN-Habitat Urban Policy Platform entries (policy metadata and texts). | Instrument ladder/mainstreaming and measurement principles: Global State of National Urban Policy [37]; OECD composite/measurement guidance [35]. |

| H | Adaptation Relevance in Climate Law | 0: no climate law / mitigation-only. 1: principle-level mention. 2: dedicated article/chapter on adaptation. 3: law mandates NAP/RAP/LAP, governance and reporting. 4: level 3 plus finance provisions, five-year review, and indicators. | Framework climate acts and amendments (consolidated in the national gazette/official journal); implementing decrees and reporting clauses; Climate Change Laws of the World database (cross-reference). | Legal embedding of adaptation, accountability cycles, indicators and finance: EU Climate Law/strategy [12,13]; OECD & UNFCCC on monitoring and finance provisions [35,36]. |

| I | Covenant of Mayors adhesion (CoM) % | Share of national population in municipalities with an adopted SECAP, including adaptation (cut-off 30 June 2025). For the CoM indicator, coverage is defined as the share of national residents living in municipalities with an adopted SECAP including adaptation as at 30 June 2025, using the CoM platform for the numerator [29] and Eurostat 2024 provisional population for the denominator [49]. CoM coverage (%) = (Population in municipalities with adopted SECAP (mitigation + adaptation) / National resident population) × 100. | Covenant of Mayors (MyCovenant) reporting platform and SECAP documents (numerator); Eurostat national resident population (2024 provisional) (denominator); JRC CoM assessment (methodological cross-check). | Coverage tiers and reporting scope for SECAPs, including adaptation: JRC CoM assessment [38]; GCoM CRF [39]; 2025 SECAP Guidebook [44]. |

| Coverage (%) | Score (I) | Label |

|---|---|---|

| ≥15.00 | 4 | Very High |

| 10.00–14.99 | 3 | High |

| 5.00–9.99 | 2 | Medium |

| 1.00–4.99 | 1 | Low |

| <1.00 | 0 | Very Low |

| Code | Index (short name) | Formula | Range | Conceptual meaning | Interpretation/use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J | NAT_CORE (National Core Strength) | ((B + F + H) / 3) | 0–4 | Robustness of the national strategic–legal backbone (NAS/NAP, LTS, climate law). | Higher = stronger national architecture. Threshold: (J ≥ 2.5) interpreted as “strong”. Used in clustering rules and differentials. |

| K | TERR_MAN (Territorial Mandate) | ((C + D) / 2) | 0–4 | Institutionalisation of regional and local mandates (RAPs, LAPs). | Higher = deeper, more formalised sub-national mandates. |

| L | LSS / URB_SYNERGY (Local Synergy Score) | ((D + G + I) / 3) | 0–4 | Density/coherence of the local–urban ecosystem (plans, national urban integration, network mobilisation). | Higher = stronger local/urban mobilisation and integration. |

| M | ADV_SCORE (Advanced breadth) | (#{B..I ≥ 3} / 8) | 0–1 | Non-compensatory breadth of advanced pillars. | Higher = more pillars at “advanced” (≥3). Prevents single-pillar compensation. |

| N | MULTI_INT (Multilevel Integration Index) | ((J + K + L) / 3) | 0–4 | Vertical balance across national core, territorial mandates and local collaboration. | Higher = more integrated multilevel system. Rule use: (N ≥ 2.5) as the minimum balance for K5. |

| O | TOP_DOWN (directional differential) | (J - L) | −4 to 4 | Directional strength of the centre relative to the local tier. | Positive = centre > local; negative = local > centre. Diagnostic only. |

| P | BOTTOM_UP (directional differential) | (L - J) | −4 to 4 | Directional strength of the local tier relative to the centre. | Positive = local > centre. Note (P = -O). Diagnostic only. |

| Cluster | No. of countries | Members | Median J (IQR) | Median K (IQR) | Median L (IQR) | Median M (IQR) | Median N (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K1 — Lagging / Fragmented | 14 | AT, BG, CY, CZ, EE, HU, IT, LV, LT, MT, PL, RO, SK, SI | 1.5–1.8 (≈0.7–1.0) | 1.0 (≈0.5–1.0) | 1.0 (≈0.7–1.3) | 0.1 (≈0.0–0.1) | 1.2 (≈1.1–1.3) |

| K2 — Top-Down Centralised | 3 | FI, LU, ES | 3.0 (≈0.3) | 1.0 (≈0.5–1.0) | 1.7 (≈1.3–2.3) | 0.3 (≈0.3–0.4) | 1.9–2.4 (≈0.3–0.5) |

| K3 — Region-Driven | 5 | BE, HR, DE, EL, SE | 1.3 (≈0.4) | 2.0–2.5 (≈0.5–1.0) | 2.0 (≈0.7) | 0.3–0.4 (≈0.1) | 1.7–1.9 (≈0.2–0.3) |

| K4 — Local / Urban Bottom-Up | 1 | DK | 1.7 (–) | 2.0 (–) | 2.3 (–) | 0.3 (–) | 2.0 (–) |

| K5 — Integrated (Multilevel) | 4 | FR, IE, NL, PT | 2.9–3.0 (≈0.3) | 2.5–3.0 (≈0.5–1.0) | 2.7–3.0 (≈0.7–1.0) | 0.6 (≈0.5–0.6) | 2.7–3.1 (≈0.3–0.6) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).