1. Introduction

Climate change is an increasingly accelerating systemic factor that is exacerbating ecological disturbances, public health issues, and socioeconomic instability. Europe is the continent experiencing the fastest warming and is undergoing temperature increases at a rate more than double the global average [1]. This is intensifying spatial disparities in terms of exposure to and vulnerability of heat waves, droughts, floods and changes in water availability [2,3]. Projections indicate not only an increase in the frequency and intensity of extremes but also significant shifts in mean climatic conditions, affecting health, agriculture, infrastructure, energy systems, and water supply [2,3]. These risks are unevenly distributed because vulnerabilities differ across socioeconomic, geographic and institutional contexts [4,5], making the design of territorially sensitive adaptation pathways more complex [6,7]. The compounding impacts of climate-related hazards are heightening socioeconomic and territorial risks and require urgent, coordinated, multilevel governance, as emphasised by the European Environment Agency [1]. At the same time, the Global Covenant of Mayors emphasises that robust multilevel networks, providing capacity-building, information, strategic guidance, and tailored finance, are crucial for empowering subnational adaptation efforts [1,8]. Effective multilevel governance is characterised by vertical and horizontal coordination mechanisms that enable inclusive stakeholder involvement, helping to bridge planning and implementation gaps and unlock local adaptation potential [8]. Academic research has also established the fundamental role of cities as political actors within multilevel climate governance structures, influencing transnational diffusion and local experimentation [9].

Nevertheless, persistent governance barriers can prevent implementation, even where formal regulatory frameworks exist. Key obstacles include limited coordination capacity, insufficient financial, technical, and human resources, as well as ambiguities in roles and responsibilities across levels [10,11]. Although the EU Adaptation Strategy positions the local level as the “bedrock” of adaptation and calls for scaled-up regional and local action with coherent policy alignment [1,12], misalignments between national, regional, and local tiers continue to undermine coherence and operational effectiveness [5,7]. The 2021 Strategy articulates a 2050 vision of a climate-resilient European society: smarter (with improved knowledge and risk/loss data), more systemic (mainstreamed across sectors and governance levels), faster (with accelerated implementation), internationally engaged, and socially just through equitable benefit distribution [12,13].

Adaptation is the process of adjustment in human (ecological, social, and economic) systems to actual or expected climatic stimuli and their effects to moderate harm or seize beneficial opportunities. In natural systems, it denotes adjustment to actual climate and its effects, potentially facilitated by human intervention [2,14,16]. It has become a central pillar of European climate policy within this long-term transformational agenda [5,12]. Unlike mitigation—which tackles the causes of climate change by cutting greenhouse-gas emissions—adaptation addresses the impacts we cannot avoid. It does so through both anticipatory and reactive measures, spanning incremental steps (e.g., protective works, nature-based solutions, risk communication) and, where these prove insufficient, more transformational shifts that reconfigure core socio-technical systems and governance arrangements [2,15,17]. The IPCC distinguishes between autonomous (largely spontaneous) ecological adjustments and planned societal interventions, cautioning against maladaptation, actions that lock in risk, heighten vulnerability, or exacerbate inequities [2,14]. Effectiveness and feasibility depend on enabling conditions, including multilevel governance, finance, knowledge and data systems, technology, and capacity building, while operating within both soft limits (options exist but are not yet accessible) and hard limits (biophysical thresholds) [2]. Inclusive, polycentric arrangements that integrate local, indigenous, and scientific knowledge are pivotal for overcoming fragmentation, enhancing access to finance and climate-risk information, embedding equity and justice, and advancing climate-resilient development pathways across scales [2,17].

Scholarly contributions further clarify these governance dynamics: structural transformation may be required beyond incrementalism [17]; local provision of adaptation “public goods” faces distinct governance challenges [18]; justice, equity and uneven adaptive capacity distributions shape outcomes [6]; legal embedding of responsibilities across sectors remains insufficient [19,11]; and multilevel governance networks can enable or constrain adaptation depending on the distribution of power, resources, and knowledge [20]. Recurring barriers emerge across this literature, including institutional fragmentation, ambiguous mandates, sectoral silos, limited coordination and knowledge brokerage capacity, resource constraints, and uneven transformative potential [7,10,11,19,20,24]. In addition, analyses of diffusion and innovation processes highlight both incremental policy layering and the need for deliberate governance interventions to trigger transformational pathways [24,25].

Within the European Union policy architecture, adaptation has been elevated in the European Green Deal and the European Climate Law, and operationalised through the 2021 EU Adaptation Strategy’s integrated, multilevel, cross-sectoral and just resilience agenda [12,13,21]. Nonetheless, heterogeneity in National Adaptation Strategies (NASs) and Plans (NAPs), uneven diffusion of regional and sectoral plans, and variable municipal engagement persist as barriers to implementation gaps and territorial disparities [1,3,22,23,26]. Barriers rooted in institutional inertia, conflicting policy priorities, and weak knowledge brokerage persist [7].

Prior comparative studies have illuminated specific components, including early NAS development [22], diffusion trajectories of national adaptation policies [24], characteristics of local climate plans across 885 EU cities [23], and monitoring of national adaptation actions [1,3,26]. However, these analyses are generally bounded to single governance levels, subsets of instruments (e.g., NASs, NAPs, local plans), or provide descriptive inventories without an integrated comparative framework that simultaneously captures cross-level alignment, cross-sector coverage, legal status and binding force, integration into urban policy and long-term strategies, and linkage with transnational city networks.

This study addresses that gap by developing and applying a harmonised, indicator–based comparative framework encompassing eight base indicators (qualitative) of adaptation governance across all 27 EU Member States: (i) National Adaptation Strategy / Plan (NAS / NAP); (ii) Regional Adaptation Plans (RAPs); (iii) Local Adaptation Plans (LAPs); (iv) Sectoral Adaptation Plans (SAPs); (v) Integration in National Urban Policy (NUP); (vi) Adaptation content in Long-Term Strategies (LTS); (vii) Adaptation relevance in Climate Law; and (viii) Covenant of Mayors adhesion (CoM) (plans incluting adaptation). The dataset integrates authoritative sources [1,3,26], Climate-ADAPT [27], Climate Change Laws of the World [28], Covenant of Mayors [29], Urban Policy Platform [30], Climate Watch [31], national and sub-national climate adaptation policy documents and explicitly codes legal status and binding force, an under-examined determinant of governance effectiveness. From the base indicators, we derive composite indices: national core robustness (NAT_CORE), territorial mandate (TERR_MAN), local/urban synergy (LSS), breadth of advanced maturity (ADV_SCORE), and multilevel integration (MULTI_INT), as well as directional differentials TOP_DOWN and BOTTOM_UP. A rule-based hierarchical classification, grounded in conceptually justified thresholds (rather than a purely algorithmic ‘black box’), assigns Member States to five governance archetypes (clusters: K1–K5).

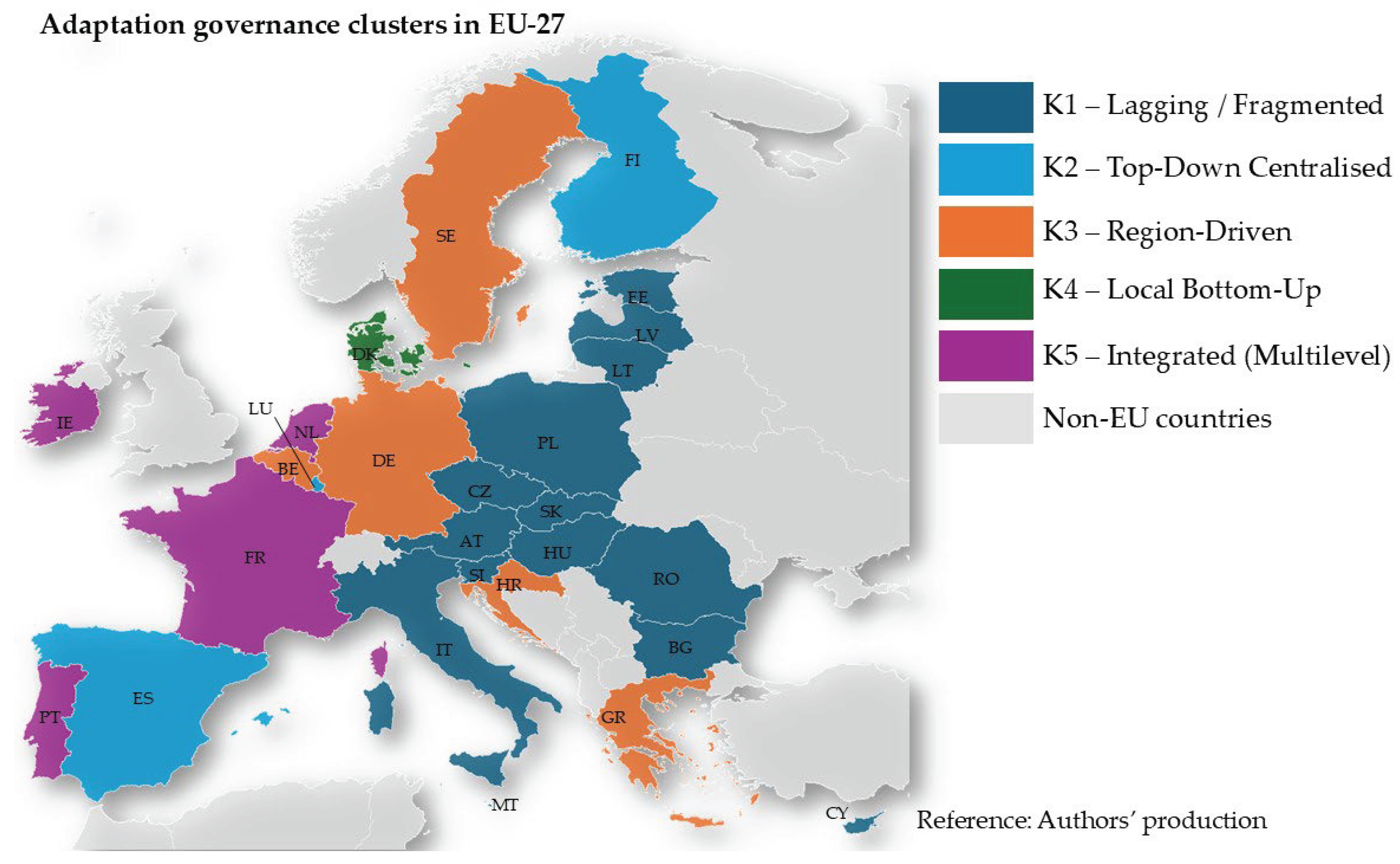

Findings delineate a gradient of multilevel institutionalisation: K1 – Lagging/Fragmented (14 states) exhibits concurrent weaknesses in regional and local tiers, as well as an as yet unconsolidated national core. K2 – Top-Down Centralised (3 states) displays a robust strategic–legal core with incomplete territorial and local diffusion; at least one sub-national pillar is below the advanced threshold. K3 – Region-Driven (5 states) is driven by a mature regional layer ahead of full national–local convergence. K4 – Local/Urban Bottom-Up (1 state) represents a distinctive bottom-up configuration with elevated local/urban synergy, in the absence of a strong regional mandate and with a still moderate national core. K5 – Integrated (Multilevel) (4 states) achieves an advanced balance, advanced climate law, at least moderate urban integration and a high multilevel integration, signalling emergent ‘whole-of-governance’ convergence.

In summary, the study pursues two principal objectives: (i) the development and application of a harmonised, indicator-based framework for mapping and typologising national, regional and local adaptation architectures across all 27 EU Member States; and (ii) the identification of key governance gaps and institutional misalignments that impede coherent, multilevel implementation.

Section 2 presents the rationale, foundations, and design logic, detailing the indicator design and methodological passages.

Section 3 introduces the five empirically grounded governance typologies (clusters K1-K5). Section 4 interprets these patterns in light of existing scholarship discussing the main findings of this research.

Section 5 concludes by outlining strategic orientations and suggests future avenues for assessing whether institutional reforms yield measurable outcomes in climate adaptation.

2. Materials and Methods

This study develops a replicable, indicator-based comparative framework to characterise national adaptation governance across the 27 EU Member States at a 2025 reference point. The objective is to operationalise multilevel adaptation governance, linking national strategic-legal backbones, territorial (regional) mandates, and local/urban diffusion, into a transparent typology of country profiles (clusters: K1-K5). The selection and structuring of indicators were theory-informed and evidence-guided by (i) the multilevel governance levers and institutional enablers enumerated in the Multilevel Climate Action Playbook (Second Edition) [8], which highlights policy instruments (economic, regulatory, voluntary/informational) and coordination, capacity, finance and civic engagement processes central to vertical integration, and (ii) the good-practice dimensions of National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) synthesised by the Global Green Growth Institute (GGGI) [34], which identify strengths and recurrent gaps across seven functional categories (Goals, Participation, Fact Base, Policy, Implementation, Finance, Monitoring & Evaluation). Integrating these complementary lenses allows simultaneous assessment of structural multilevel diffusion [8] and procedural/functional plan robustness [34].

2.1. Rationale and design Logic

Adaptive capacity in the EU-27 depends not only on the existence of national adaptation strategies but on how coherently mandates, legal anchoring, territorial diffusion, and urban/local mobilisation interlock across governance scales [8,34]. Prior comparative studies have highlighted multilevel fragmentation, uneven vertical integration, and variation in legal-institutional consolidation as persistent barriers to effective adaptation (e.g., multilevel governance and urban/climate governance literature: [4,7,9,17,18,22,25,32,33]. However, no recent post-European Climate Law (2021) assessment systematically re-codes the maturity and binding force of the constituent pillars shaping national, regional, and local adaptation architectures as of 2024–2025. This study was therefore designed to: (i) operationalise a transparent, reproducible indicator framework that captures qualitative institutional attributes; (ii) derive composite indices that represent core structural dimensions; (iii) classify Member States into conceptually meaningful governance clusters via an explicit rule set rather than a cloudy clustering algorithm, thereby maximising interpretability for policy learning.

2.2. Scope, temporal cut-off, and units of analysis

The analysis was conducted across the 27 EU Member States, as the starting point is to understand the integration of the New European Adaptation Strategy (2021) in the EU-27. This research is the result of three years of data collection and policy review of national and subnational (regional, local, and urban) policy documents on adaptation (from 2022 to 2025). All data, indicators, and indices presented in this document reflect the state of adaptation in the EU-27 as of July 2025. Where new strategies or laws have been formally adopted but are not yet in force (vacatio legis), the status of adoption (anchored to the date of adoption) has been used. Drafts under consultation without formal approval have been excluded from the count. Where national documents were not publicly available, attempts were made to obtain the information through European and international platforms.

2.3. Data sources

Primary data derive from a comparative document analysis of official, publicly available policy and legal instruments for each Member State:

National Adaptation Strategies (NAS) and National Adaptation Plans (NAP) (if distinct).

National Climate Laws (framework/omnibus climate legislation).

Long-Term Strategies (LTS) submitted under Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 and UNFCCC.

Regional Adaptation Plans (RAPs) (all regions or a representative sample where >50% coverage).

Local Adaptation Plans (LAPs) (stand-alone or integrated in Sustainable Energy and Climate Action Plans, SECAPs).

Sectoral Adaptation Plans in key climate-sensitive sectors (water, health, agriculture, infrastructure, coastal).

National Urban Policies/spatial planning frameworks embedding adaptation.

Monitoring, evaluation and finance annexes were available.

These were identified, downloaded and cross-validated using authoritative reports and meta-platforms: European Environment Agency reports (EEA) [1,3,26]; Climate-ADAPT [27]; Climate Change Laws of the World database [28]; Covenant of Mayors (CoM) platform [29]; UN-Habitat Urban Policy Platform [30]; Climate Watch [31]. When a platform summary conflicted with the primary legal text, the original national source prevailed. For each indicator, at least two independent evidence sources (e.g., statutory articles and implementation guidelines) were sought, where feasible.

Documents not available in English (including several strategies, climate laws, and national and sub-national policy documents) were translated from the official national languages using DeepL (version current as of 2025).

2.4. Indicator construction (Base indicators B-I)

Eight base indicators were operationalised to capture discrete governance aspects (see

Table 1):

(i) National Adaptation Strategy/Plan (NAS/NAP)– Existence, recency and institutional robustness of national strategic and operational adaptation framework (strategy + plan).

(ii) Regional Adaptation Plans (RAPs) – Degree to which adaptation planning is mandated/structured at regional (sub-national) tier.

(iii) Local Adaptation Plans (LAPs) – Penetration, mandate and maturity of municipal adaptation plans.

(iv) Sectoral Adaptation Plans (SAPs) – Presence and binding nature of stand-alone sectoral adaptation plans (e.g., water, health, agriculture).

(v) Adaptive content in Long-Term Strategy (LTS) – Strength and specificity of adaptation integration in national long-term climate strategy (e.g., neutrality roadmap).

(vi) Integration in National Urban Policy (NUP) - Degree to which adaptation is structurally embedded in national urban/territorial policy framework.

(vii) Adaptation relevance in Climate Law – Extent to which national climate legislation embeds adaptation governance (duties, instruments, review, finance).

(viii) Covenant of Mayors adhesion (plans included adaptation) – proportion of national population covered by adaptation-inclusive SECAPs, by capturing population coverage in the CoM network.

Each indicator was ordinally coded 0–4 using explicit anchor thresholds. Each score point was anchored to explicit, observable criteria (e.g., B=3 requires revision within ≤6 years, plus indicators & responsibility mapping; B=4 additionally requires dedicated budget lines, a monitoring framework, and a mandatory review cycle within ≤5 years). This criterion-anchoring reduces coder discretion and facilitates replication.

For each Member State, the percentage of CoM coverage was calculated using the following formula (1):

| CoM Coverage (%) = (Population in municipalities with an adopted SECAP addressing both mitigation and adaptation by June 2025 [29]/National resident population (Eurostat 2024 provisional)) ×100 |

(1) |

Then the percentage was converted into a label and then into a score (I) (see

table 2).

2.5. Composite Indices (J–P)

To capture higher-order governance properties and vertical balance, structural composite indices were derived for each of the MSs, using the eight base indicators (see

Table 3).

2.6. Rule-Based cluster classification

Rather than using k-means or hierarchical clustering (which can obscure interpretability and mix ordinal with interval assumptions), a deterministic hierarchical decision tree (a sequence of logical predicates) was engineered to map indicator patterns to five theoretically grounded archetypes. This approach ensures that assignment to each cluster reflects whether it surpasses (or fails) clearly defined governance maturity conditions, directly traceable to multilevel integration concepts and good practice benchmarks.

Clusters were applied in the following hierarchical order (exclusive assignment once a condition was satisfied):

K5 (Integrated Multilevel) – simultaneous satisfaction of minimum multilevel balance (N ≥2.5) plus advanced local tier (D ≥3), solid regional presence (C ≥2), climate law anchoring (H ≥3), national strategy robustness (B ≥2), and urban integration (G ≥2).

K3 (Region-Driven) – high regional mandate (C ≥3) with at least embryonic local presence (D ≥1), territorial consolidation (K ≥2), but national core not yet strong (J <3) and not meeting K5 criteria.

K4 (Local Bottom-Up) – strong local synergy (L >2) driven by at least one advanced local lever (D ≥3 or G ≥2 or I ≥2), weak/limited regional mandate (C ≤2), moderate/immature national core (J <3), not previously classified as K5 or K3.

K1 (Lagging/Fragmented) – breadth of under-development: ≥4 base indicators at ≤1 (low), narrow horizontal maturity (M ≤0.25), weak national core (J <2.5), weak territorial layers (C ≤2, D ≤2), and low local synergy (L ≤2), not qualifying as K3/K4/K5.

K2 (Top-Down Centralised) – residual assignment where national core is strong (J ≥2.5) but integrated balance not yet consolidated (N <3) and no prior archetype condition met.

The final formula (2) applied to classify countries into different clusters is:

In spreadsheet implementation (MS Excel 365), a nested IF formula operationalised the hierarchy (provided in Supplementary Material S2). Any case returning “Review” triggered manual reassessment (none remained after quality checks).

A “Review” flag (none triggered in final dataset) would prompt manual re-examination of borderline or anomalous profiles.

2.7. Limitations

A rule-based typology ensures greater transparency but may not fully capture the latent, multidimensional proximities that can be identified through probabilistic clustering methods. Ordinal compression (with anchors from 0 to 4) prioritises comparability at the expense of intra-level variation. Delays in publication, such as recent subnational mandates that have not yet appeared on European and international portals, may result in conservatively low scores. Employing explicit anchors, a comprehensive evidence-reference code, and sensitivity analyses helps mitigate these limitations. For future research, it would be appropriate to subject the scoring scale developed in this study to an expert panel for validation and refinement. It will also be essential to engage stakeholders across the EU-27 to verify that the interpretations and analyses derived from official documents accurately reflect real-world conditions.

3. Results: Typologies of climate adaptation governance systems in the EU

The comparative analysis across the 27 EU countries reveals a complex and heterogeneous landscape of climate adaptation governance, as discussed in the following subsection. Most Member States exhibit relatively high formal strategic maturity at the national level, with the majority possessing up-to-date National NASs and, to a lesser extent, operational NAPs. Otherwise, the analysis highlights that a significant variation persists in the territorial diffusion of adaptation efforts, particularly about RAPs, LAPs and the implementation of SAPs. These discrepancies often reflect a country's institutional structures, particularly the presence or absence of regional mandates, legal codification and organised, multi-level coordination mechanisms.

Legal frameworks, such as climate or adaptation laws, act as enabling structures that often clarify roles, establish reporting duties and define revision cycles. Nevertheless, legal presence alone does not ensure systemic uptake, which also depends on financing channels and operational coherence. Participation in transnational initiatives (e.g. the Covenant of Mayors) and the existence of national support programmes reinforce local-level diffusion, particularly when accompanied by coherent urban policies and performance standards. High-performing systems are further distinguished by interoperable data systems and monitoring architectures, which facilitate vertical feedback and the adaptive recalibration of strategies. Based on this evidence, the analysis identifies five distinct clusters of adaptation governance. Each cluster represents a unique combination of institutional maturity, legal anchoring and vertical integration:

Cluster 1 (Lagging/Fragmented): Weak coordination at both national and subnational levels, with fragmented and often inconsistent local and regional action.

Cluster 2 (Top-Down Centralised): Strong central strategies with limited territorial institutionalisation and incomplete vertical integration.

Cluster 3 (Region-Driven): Robust regional engagement compensating for a comparatively weak national strategic core, with moderate multilevel alignment.

Cluster 4 (Local Bottom-Up): Strong bottom-up mobilisation, particularly through local legislation and urban initiatives, coupled with a moderate national framework and marginal regional role.

Cluster 5 (Integrated Multilevel): Balanced and legally grounded multilevel systems with high institutional maturity, although gaps remain in sectoral adaptation and implementation monitoring.

The following sections provide a detailed account of each cluster, highlighting their governance features and existing gaps, as well as the implications of advancing integrated and territorially responsive adaptation systems in Europe.

3.1. Aggregate patterns of adaptation governance maturity across EU Member States

This research reveals a clear hierarchy in the maturity of adaptation governance. At the national level, measured by the NAT_CORE index (which is the average of the National Adaptation Strategy/Plan, standalone Climate Law, and adaptive content in the Long-Term Strategy), the country consistently receives top scores. This is primarily because all the countries have adopted a NAS, and almost all have also implemented a NAP. Seven countries (Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Finland, Lithuania, the Netherlands, and Spain) achieve the maximum score of 4, reflecting recently revised strategies, explicit legal mandates, and operationalised long-term commitments. A further ten states (including Germany, Portugal, Ireland, and France) score 3, indicating robust but partially outdated frameworks, while only a handful (Greece, Hungary, Malta, and Sweden) remain at levels 1–2, signalling overdue revisions or the absence of legal foundations.

By contrast, sub-national institutionalisation, measured by the TERR_MAN index (the average of Regional and Local Adaptation Plans), is highly uneven. Federated or decentralised systems, such as those in the Netherlands (4.0), France (3.0), Ireland (3.0), and Belgium (2.5), benefit from binding regional mandates or well-resourced coordination platforms, yielding comprehensive RAPs and compulsory LAPs. Unitary, centralised states (e.g., Cyprus, Estonia, Luxembourg, Bulgaria) score below 1, relying primarily on sectoral mainstreaming and voluntary networks rather than territorially explicit planning. This divergence demonstrates that proper vertical integration demands both strategic leadership at the centre and institutional mechanisms that bridge national and sub-national competencies.

The municipal level exhibits the most remarkable heterogeneity. The URB_SYNERGY index (the mean of Local Adaptation Plans, integration into National Urban Policy and Covenant of Mayors adhesion) remains modest overall. High performers, including Ireland (3.3), the Netherlands (2.3), Portugal (3.0), and France (2.0), combine mandated, council-approved LAPs with urban-policy levers and strong CoM engagement. By contrast, Austria (0.7), Bulgaria (1.0), and the Czech Republic (0.3) lack formal municipal duties, urban planning integration, or stakeholder uptake, illustrating that statutory obligations, planning integration, and network cooperation must operate in concert to drive local adaptation.

Sectoral integration also lags behind strategic maturity. Few Member States produce standalone Sectoral Adaptation Plans (SAPs); instead, adaptation chapters are embedded within NAS/NAPs. SAP scores average at levels 1–2, with notable exceptions (France, Finland, Sweden), where cross-cutting standards—climate-resilient infrastructure codes, land-use regulations, and adaptation clauses in building codes—effectively mainstream resilience into sectoral governance.

Advanced performers are further identified by the ADV_SCORE composite (proportion of eight base indicators scored ≥ 3). France, Ireland, the Netherlands and Portugal exceed 0.6, demonstrating breadth across strategic, territorial and local dimensions. However, positive TOP_DOWN differentials (NAT_CORE minus URB_SYNERGY) in most Member States indicate strong central frameworks paired with weaker municipal systems; only Ireland and Portugal approach balance or exhibit slight bottom-up dynamics.

Proper multilevel integration emerges where five conditions converge:

Statutory mandates at regional and municipal levels that translate central strategies into enforceable plans.

Urban-policy instruments integrated with binding local obligations and stakeholder networks (e.g. Covenant of Mayors SECAPs).

Dedicated legal frameworks and explicit adaptation provisions within long-term strategies, ensuring iterative revision cycles.

Cross-cutting sectoral regulations that embed resilience requirements in the absence of SAPs.

Mature data-governance and capacity-building programmes that reduce municipal transaction costs, enable evidence-based prioritisation and support feedback loops for national strategy recalibration.

Only those Member States aligning these dimensions achieve high coherence and maturity across all governance levels, an outcome most evident in Ireland, France, the Netherlands, and Portugal.

3.2. Typologies of Adaptation Governance (Five country clusters)

Countries are grouped into five analytically derived governance typologies based on (i) strategic maturity (NAS/NAP currency), (ii) territorial diffusion (RAP/LAP mandates and uptake), (iii) horizontal sectoral integration (SAP presence), (iv) legal codification, (v) engagement/network leverage, and (vi) enabling capacities (data, finance, multi-actor processes). These clusters help interpret the diversity of adaptation governance across the 27 EU member states, highlighting distinct pathways and deficits. This reflects the multilevel and multi-actor dynamics necessary for systemic transformation.

3.2.1. Cluster 1: Lagging/Fragmented

Cluster 1 includes countries situated at an initial and fragmented stage of climate adaptation governance. These Member States are characterised by a simultaneously weak national core (NAT_CORE < 2.5), limited sub-national mandates (TERR_MAN ≤ 1.5), and underdeveloped local synergy (LSS ≤ 1.7). Although all countries possess at least a formal national adaptation strategy or plan, their institutional capacity to implement it effectively is limited, and the legal enforceability is often absent or weak.

Several national frameworks are either outdated (e.g. Estonia with a >6-year-old strategy; Malta's 2012 NAS unrevised and scoring only 1), still in draft or embedded in other strategies (Hungary lacks an adopted NAP; Poland's operational elements are housed within Klimada 2.0, not in a standalone NAP), or legally non-binding (Austria, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czechia, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania). Italy's updated PNACC (score 3) slightly improves formal coverage but still lacks earmarked finance and binding implementation provisions.

RAPs are either absent or voluntary in all countries within this cluster (scores 0–2). Isolated non-binding examples exist, such as some strategies from Austrian Länder, Hungarian counties (during the 2014–2020 EU funding period), or voivodeship-level documents in Poland. LAPs also remain sporadic and non-compulsory, with LAP scores ranging from 0 to 2. Poland stands out with a score of 2, primarily due to the 44MPA programme, while most countries exhibit limited spatial coverage.

The CoM uptake is weak: many countries register very low participation (score 0 in Austria, Czechia, Estonia, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovakia), low in Bulgaria, Hungary, Lithuania and Slovenia (score 1), and only moderate levels in Cyprus (3), Italy and Latvia (2). This indicates that CoM has not yet been leveraged as a systemic driver of bottom-up adaptation.

Sectoral Adaptation Plans (SAPs) are rarely adopted as standalone instruments. Most countries in this cluster score 0 or 1, indicating either their absence or the early, fragmented elaboration of this concept. Only Slovakia and Slovenia score 2, reflecting partial sectoral developments without binding force.

LTSs rarely contain robust adaptation content (scores 0–2): when present, it is typically narrative, lacking quantified targets, dedicated budgets, or monitoring frameworks. Similarly, integration of adaptation into National Urban Policies (NUPs) remains weak (scores 0–2), with few examples translating resilience principles into binding municipal obligations or financial instruments. Poland and Romania exhibit somewhat more explicit references, although they are still non-mandatory.

Legal anchoring is highly uneven. Only Malta achieves the maximum score (4) for climate legislation (reflecting high integration of adaptation), while Slovenia reaches a moderate level (2). Most others either contain weak references (e.g. Bulgaria and Lithuania, score 1), mitigation-only statutes, or no legislative mention of adaptation (score 0), thus reducing enforceability and accountability.

Overall, Cluster 1 is the only group displaying simultaneous institutional weakness at both sub-national tiers, coupled with a national core that is too weak to compensate. This results in the lowest Multilevel Integration Index (MULTI_INT ≤ 1.3) and primarily top-down but shallow configurations (TOP_DOWN > zero and BOTTOM_UP < 0), where adaptation is led by the centre but without strong local engagement or feedback loops.

3.2.2. Cluster 2: Top-Down Centralised

Cluster 2 comprises countries where climate adaptation governance is characterised by a strong, legally anchored national core, yet with limited vertical diffusion across regional and local tiers. This configuration is typical of Finland, Luxembourg, and Spain, which all exhibit high values in NAT_CORE (≥2.5), reflecting consolidated national frameworks, robust strategic instruments, and climate legislation. Nevertheless, their Multilevel Integration Index (MULTI_INT < 3) remains below the threshold for integrated governance, due to insufficient territorial devolution and weak horizontal spillover effects.

Finland presents one of the most mature national adaptation architectures in the EU, with an updated National Adaptation Plan (2022), a revised Climate Act (2022), and a comprehensive Climate Risk Assessment. However, regional and local adaptation remain in their early stages: RAPs are in the piloting phase, and LAPs are still confined to a few cities, such as Helsinki and Tampere. Sectoral adaptation is present but unevenly binding across ministries, and while participation in the CoM exists, municipal coverage remains limited and variable.

Spain has a longstanding NAS–NAP framework supported by a national climate law (2021) and a centralised monitoring system. Despite some proactive regional adaptation strategies—particularly in the Basque Country and Catalonia—the overall territorial mandate remains fragmented, with RAP and LAP scores in the intermediate range. CoM participation is relatively high (score 3), but does not yet translate into systemic local embedding, and local synergy (LSS) remains moderate.

Luxembourg is notable for its policy coherence at the national level, scoring 3 or above in nearly all core indicators (NAS/NAP, climate law, CRA, LTS, SAP). However, the country’s small administrative scale constrains the development of regional tiers—RAPs are not applicable—and local implementation remains highly centralised. Few municipalities have developed independent adaptation plans or initiatives, and bottom-up engagement is limited.

What differentiates Cluster 2 is the asymmetry between robust central frameworks and the incomplete functional integration of subnational levels. Unlike Cluster 5, which achieves vertical coherence through systemic local activation, or Clusters 3 and 4, which exhibit strong regional or bottom-up dynamics, Cluster 2 lacks consistent downward diffusion of mandates. Territorial indicators such as RAP, LAP, and TERR_MAN remain in the intermediate range (scores 1–2), and local mainstreaming via NUPs or green infrastructure planning is rarely enforced through binding obligations or earmarked funding.

From a policy perspective, the main challenge for Cluster 2 countries is to enhance vertical articulation mechanisms. This includes expanding the coverage and legal mandate of regional and local adaptation plans, strengthening municipal participation (MUNIC_COV, LSS), and improving the sectoral integration of adaptation objectives (SAP, INST_SEC). Greater coherence in budgeting, implementation cycles, and territorial delegation would facilitate a transition towards the more integrated multilevel governance observed in Cluster 5.

3.2.3. Cluster 3: Region-Driven

Cluster 3 identifies countries where climate adaptation governance is primarily driven by regional institutions rather than national leadership. This configuration is characterised by strong territorial mandates (TERR_MAN ≥ 2.0), high-performing Regional Adaptation Plans (RAP scores 3–4), and intermediate levels of multilevel integration (MULTI_INT ≈ 1.7–2.1). Conversely, national core frameworks (NAT_CORE ≤ 1.7) tend to be underdeveloped, fragmented, or weakly binding.

Belgium exemplifies a constitutionally decentralised model: adaptation is fully delegated to the regional level, where autonomous RAPs (score 4) and high CoM participation (score 3) are observed. The federal NAS is weak (score 1) and no national climate law is in place (CL_LAW = 0), yet regional governance compensates with strong implementation mechanisms.

Croatia and Greece follow an asymmetric configuration: both register strong regional planning (RAP = 3–4), but their national frameworks remain insufficiently structured. Croatia lacks an overarching climate law and has only partial sectoral anchoring, while Greece exhibits a low NAT_CORE score (1.3) and limited legal force for national adaptation strategies. In both cases, regional initiatives are often supported by EU funding cycles rather than national policy coherence.

Germany shows a similar pattern, with the Länder playing a central role in adaptation planning, supported by high RAP scores (3), yet without a binding national climate law (CL_LAW = 1). The federal adaptation framework is strategic in nature but lacks enforceability, with partial sectoral integration (SAP = 2) and limited cascading into municipal tiers.

Sweden, often perceived as a top-down system, enters this cluster due to its active regional and local tiers. RAPs and LAPs score 3 and 2 respectively, and urban mainstreaming (NUP = 3) is relatively advanced. However, the national strategy remains non-binding (CL_LAW = 0), and sectoral coverage is only moderate. CoM participation is relatively low (score 1), reflecting limited bottom-up mobilisation despite regional and municipal engagement.

Across Cluster 3, subnational dynamism emerges as the main engine of adaptation policy. Urban integration (URB_SYNERGY ≈ 2.0) is present but uneven, and CoM mobilisation ranges widely—from high in Belgium to low in Sweden—indicating differentiated local commitment. These countries demonstrate that effective regional adaptation governance can emerge independently of a strong national legal backbone. However, this strength remains structurally constrained by vertical misalignments, uneven legal anchoring, and lack of systemic coherence between tiers. The result is a multilevel system that is operationally effective in some components but institutionally unbalanced, limiting the overall consolidation of an integrated adaptation regime.

3.2.4. Cluster 4: Local Bottom-Up

Denmark represents a paradigmatic case of decentralised adaptation governance, where local and urban actors assume a leading role in shaping climate resilience. Despite the absence of stand-alone RAPs, reflecting a weak or non-mandatory regional tier, adaptation has been strongly embedded at the local level through legally binding LAPs, mandated by the 2012 National Action Plan and fully integrated within land-use planning legislation. The 2012 Action Plan for a Climate-Proof Denmark explicitly instructed that “all municipalities shall prepare a climate-adaptation action plan within a maximum of two years”. This obligation is enshrined in the Water Sector Act and municipal planning rules, making LAPs compulsory for all 98 municipalities. These plans must be formally approved by the city council and integrated into local spatial plans (Kommuneplaner and Lokalplaner). Since 2013, an amendment to the Environmental Protection Act requires each municipality to develop a cloudburst plan, addressing flood and stormwater risks. As a result, LAPs now cover 100% of the population, and their scope includes risk mapping, local prioritisation, and operational adaptation strategies.

At the same time, national coordination remains moderate. The NAS (2008) and NAP (2012) have not been updated or backed by systematic monitoring or budgeting frameworks. The Danish Climate Act (2020) is mitigation-focused and does not enshrine binding adaptation mandates, although sectoral and spatial planning laws offer indirect support (e.g., flood risk integration). No formal SAPs have been issued, with sectoral adaptation taking place through voluntary or integrated measures in other plans.

At the urban scale, Denmark demonstrates high local synergy (LSS > 2), thanks to an advanced National Urban Policy (NUP) and the strong incorporation of adaptation into local land-use regulations. While Denmark has a medium number of submitted SECAPs under the Covenant of Mayors (CoM), with a CoM population coverage of just 4.08%, its national legislation mandates stronger adaptation standards than those typically found in CoM-affiliated countries. The national portal Klimatilpasning.dk, coordinated by the Danish EPA, provides municipalities with templates, technical guidance, and tools for adaptation planning, including the Kystplanlægger coastal tool and flood risk mapping platforms. In summary, Denmark exemplifies the K4 model, where city-led innovation and local legal mandates are the primary drivers of adaptation.

Inizio modulo

Fine modulo

3.2.5. Cluster 5: Integrated (Multilevel)

Cluster 5 represents the most advanced and consolidated model of climate adaptation governance in the EU. Countries in this cluster demonstrate legally anchored, vertically integrated multilevel systems, with consistent implementation across national, regional, and local levels. This configuration is characterised by strategic coherence, legal robustness, and operational alignment, embodying a “whole-of-governance” approach that combines top-down frameworks with decentralised capacity and cross-scale coordination.

All four countries meet the stringent criteria for this cluster:

A dedicated or embedded NAS/NAP with formal adoption and strategic orientation (B ≥ 2);

Mandatory or functionally equivalent RAPs, either as standalone instruments or integrated in regional spatial planning (C ≥ 2);

Legally required LAPs covering over 50% of the population (D ≥ 3);

National climate laws that explicitly address adaptation and anchor governance responsibilities (H ≥ 3);

Urban integration and vertical coherence, with legal mechanisms and planning tools ensuring coordination across scales (G, N ≥ 2).

France exhibits one of the most institutionalised frameworks. The NAS/NAP are articulated, while mandatory Local Climate-Air-Energy Plans (PCAET) and regional SRADDET frameworks integrate adaptation across spatial and energy planning. The Energy-Climate Law and recent national strategies provide legal and procedural clarity. However, the absence of standalone SAPs and limited engagement with the Covenant of Mayors (CoM <1%) expose weaknesses in sectoral articulation and participatory governance at the local level.

Ireland anchors adaptation in the Climate Action and Low Carbon Development Act (2015, revised 2021), which mandates the National Adaptation Framework (NAF) and a suite of Sectoral Adaptation Plans (SAPs). All municipalities are legally required to adopt Local Climate Action Plans (LCAPs), supported by the CARO network, a unique model of functional regional hubs. While Ireland lacks standalone RAPs, the National Planning Framework and coordination role of CAROs ensure effective multilevel integration.

The Netherlands presents a fully embedded and spatially coordinated model. The Delta Programme, supported by the Delta Act, requires stress testing, risk dialogues, and adaptation planning at both municipal and provincial levels. Adaptation is embedded in the Environment and Planning Act, and responsibilities are distributed among municipalities, provinces, and water boards. Although sectoral planning and CoM participation remain limited, the functional integration of spatial planning and hydrological governance makes the Dutch model a reference case for decentralised climate resilience.

Portugal complements its updated NAS/NAP (ENAAC + P-3AC) with a robust legal foundation under the Climate Framework Law (2021). This law mandates the development of Local Adaptation Plans (LAPs) and requires regions to adopt adaptation strategies, effectively institutionalising the multilevel system. While RAPs are not yet universal and SAPs are still embedded in sectoral planning, Portugal demonstrates strong legal mechanisms, procedural innovation, and growing urban integration through platforms such as the AdapteClima portal.

In summary, Cluster 5 countries represent the upper benchmark of adaptation governance maturity within the EU. While some differences remain in sectoral specificity, community engagement, or international platforms like CoM, these systems offer strong examples of how adaptation can be embedded across scales and legal instruments. Future trajectories for these countries involve: (i) the consolidation of SAPs, (ii) the expansion of indicator and monitoring frameworks, and (iii) the development of dedicated financial mechanisms to support implementation, paving the way toward systemic and institutionalised climate resilience.

3.3. Territorial distribution of adaptation governance clusters

Distinct spatial patterns emerge when adaptation-governance maturity is plotted across the EU, reflecting deep-seated administrative traditions, planning cultures, and institutional architectures. Five cluster archetypes (see

Figure 1) capture the diversity of multilevel governance arrangements, each offering lessons on innovation pathways, coordination bottlenecks and diffusion dynamics.

K1 – Lagging/Fragmented:

Predominantly Central and Eastern European states (e.g. Bulgaria, Czechia, Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia) fall into this category. Outdated or missing strategic frameworks, weak subnational mandates, and minimal urban-policy integration have confined adaptation to nascent or project-based efforts.

K2 – Top-Down Centralised:

Although Finland, Luxembourg and Spain exhibit robust national leadership underpinned by clear legal frameworks, subnational diffusion remains limited. Adaptation objectives cascade via sectoral regulations rather than territorially tailored plans. Although national cohesion is strong, local innovation and place-based responses to vulnerability can be stifled.

K3 – Region-Driven:

Belgium, Croatia, Germany, Greece, and Sweden rely primarily on regional authorities. Binding decrees or soft-law platforms at the Länder or regional level bridge national directives and municipal efforts. However, uneven local engagement and resource disparities result in patchy implementation, indicating a need for more substantial municipal incentives and capacity-building to complement regional cores.

K4 – Local Bottom-Up:

Denmark demonstrates a decentralised, municipality-led approach. In the absence of formal regional mandates, peer networks and council-approved spatial plans have achieved universal coverage. This grassroots paradigm highlights the power of empowered local authorities but underscores the necessity of national oversight to maintain coherence and equity.

K5 – Integrated (Multilevel):

France, Ireland, the Netherlands and Portugal epitomise seamless vertical alignment. National strategies, standalone climate laws and long-term plans explicitly mandate regional and municipal action, creating an institutional feedback loop in which local pilots inform national refinements and vice versa. This model accelerates iterative learning, secures dedicated budgeting and engenders broad stakeholder buy-in.

As shown in

Figure 1, these clusters are not randomly distributed but rather correlate with historical governance models and planning legacies. The contrast between Integrated – Multilevel performers and Lagging / Fragmented states underscores the importance of statutory mandates, regulatory integration and stakeholder networks in achieving systemic resilience. Moreover, cross-cluster collaboration, pairing bottom-up innovators with top-down centralisers, or matching lagging states with advanced peers, offers a promising route to foster convergence and tailor support mechanisms to local risk profiles.

4. Discussion

The comparative assessment of the 27 EU countries reveals five recurring governance configurations (clusters): Lagging/Fragmented, Top-Down Centralised, Region-Driven, Local Bottom-Up, Integrated Multilevel. Rather than depicting a linear progression, these clusters represent distinct equilibria between strategic maturity, territorial diffusion, sectoral integration and legal anchoring. They corroborate the observation that adaptation pathways are path-dependent and shaped by the interplay of political authority, knowledge systems, and resource endowments, rather than by policy diffusion alone [22, 24]. The concentration of maturity at the national tier, contrasted with uneven sub-national uptake, echoes earlier evidence on the persistent ‘governance gap’ between national agenda-setting and local implementation [10,11]; nevertheless, the typology presented here nuances this gap by demonstrating that formal mandates do not automatically translate into effective vertical integration, thereby confirming insights from multilevel governance scholarship.

The findings reinforce the premise that a legal framework is a necessary but insufficient precondition for systemic uptake [6,13]. Countries grouped in Cluster 2, for instance, exhibit robust national legislation yet limited territorial embedding, a pattern consistent with EU-wide reviews that portray statutory provisions as ‘amplifiers’ whose effect hinges on complementary capacity-building and financing mechanisms [12,22]. Conversely, Cluster 3 illustrates how strong regional agency can compensate for a weak national strategic core, resonating with empirical studies of federal or highly decentralised contexts [18,20]. Denmark’s bottom-up arrangement (Cluster 4) substantiates claims that municipal planning obligations embedded in land-use regulation accelerate on-the-ground implementation [32,33]. However, the absence of an intermediate tier raises questions about the coordination of cross-scale risks, such as catchment-wide flooding. By contrast, Cluster 5 demonstrates that genuinely integrated systems combine binding multilevel mandates with iterative monitoring and knowledge infrastructures [26,27]; yet even these advanced jurisdictions reveal deficits in horizontal sectoral mainstreaming, mirroring critiques that line-ministry adaptation lags behind spatial and environmental planning [17, 19]. Engagement in transnational city networks is positively associated with local plan diffusion; however, this relationship varies with national enabling conditions, underscoring that network benefits are mediated by domestic institutional capacity [8,23]. The uneven leverage of the Covenant of Mayors, in particular, highlights the need for national programmes that translate voluntary commitments into enforceable standards and resources [29].

Taken together, the results advance adaptation governance theory by replacing a unidimensional maturity ladder with a multidimensional portfolio perspective, which views functional integration as the co-evolution of legal clarity, financial incentives, and interoperable data systems, rather than the attainment of any single threshold [17]. The disconnect observed in Cluster 2 cautions against conflating statutory ambition with transformational capacity, reinforcing the importance of scalar justice considerations [6]. From a policy standpoint, a differentiated enabling framework is required: Cluster 1 countries should prioritise capacity-building, earmarked funding linked to maturity indicators and national technical hubs for standardised risk data; Cluster 2 should introduce binding or incentivised regional and local plans, performance-based fiscal transfers and permanent vertical-coordination platforms; Cluster 3 would benefit from minimum national coherence standards for risk methodologies and monitoring; Cluster 4 needs functional regional consortia and mechanisms that integrate municipal outputs into national infrastructure prioritisation; and Cluster 5 ought to deepen sectoral mainstreaming, broaden participatory mechanisms and strengthen outcome-orientated monitoring. Across all clusters, interoperable climate-risk information portals [27], stable sub-national finance such as revolving funds or climate bonds [31] and equity-focused allocation criteria are pivotal to avoiding a widening ‘adaptation readiness divide’, while scaling the EU Mission on Adaptation’s target of 150 climate-resilient regions by 2030 offers a laboratory for systemic experimentation [27].

This study contributes to the literature by integrating functional and formal dimensions of governance and identifying intermediate clusters not as transitional stages but as stable configurations with specific leverage points, thereby enabling more targeted policy design. Nonetheless, several limitations must be acknowledged: reliance on institutional indicators rather than outcome metrics. This cross-sectional design is unable to capture rapid reforms, and it has incomplete coverage of financial flows and private-sector involvement. Future research should triangulate institutional maturity with quantitative measures of risk reduction and distributive impacts, pursue longitudinal analyses of cluster transitions, and explore digital innovations such as territorial digital twins as enablers of adaptive management. Ultimately, achieving climate-resilient governance across Europe requires the convergence of statutory mandates, multilevel coordination, data interoperability, and fiscal coherence; bridging the maturity gap is both a prerequisite and an opportunity for a just, competitive, and green European Union.

5. Conclusions

Recent data confirm that climate-related risks in Europe are increasing in frequency and severity [1], putting growing pressure on governance systems whose capacity to adapt remains uneven. The five archetypes identified in this study reveal that only a truly multilevel governance framework, with aligned legal mandates, financing streams and information infrastructures at European, national, regional and municipal tiers, can deliver resilient outcomes.

Countries with a strong municipal commitment to the Covenant of Mayors but limited higher-level support (e.g., Poland, Italy) remain trapped in short-lived, project-based initiatives. In contrast, those with robust climate legislation and national strategies (e.g., Spain, Finland) still face a delivery gap when sub-national planning is voluntary or only partially institutionalised. Region-centric systems (Germany, Belgium) demonstrate sub-national innovation but lack a dedicated forum for managing cross-border risks.

Denmark’s example shows how embedding adaptation into statutory municipal planning accelerates implementation, albeit in the absence of co-ordinated regional mechanisms. The Netherlands, France, and Portugal, which represent the Integrated (Multilevel) cluster, demonstrate how binding mandates combined with interoperable data platforms can be effective, provided that adaptation is integrated into all sectoral policies and supported by civic engagement:

Three fundamental imperatives emerge from these considerations:

Transparent multilevel governance: Governance at every level must be endowed with well-defined roles, resources, and accountability mechanisms, from EU directives down to municipal bylaws, so that no jurisdiction becomes a weak link.

Sectoral mainstreaming: Integrating adaptation into sectoral plans (such as agriculture, transport, land-use, and health) is essential; siloed approaches fail to capitalise on synergies and leave critical vulnerabilities unaddressed.

Local planning integration: The local/municipal tier must embed adaptation as a core mandate, through binding land-use regulations, performance-based fiscal transfers, and streamlined reporting, to turn high-level commitments into on-the-ground resilience.

Policy recommendations therefore call for:

Performance-based fiscal transfers that reward demonstrable risk-reduction outcomes.

Statutory or consortial regional coordination bodies to align municipal plans and mediate inter-jurisdictional trade-offs.

Integration of local reporting streams (e.g., CoM) into the EU adaptation monitoring cycle to provide comparable, continent-wide indicators.

Systematic alignment of cohesion, agricultural and recovery funds with adaptation metrics, ensuring financial scale underpins systemic resilience.

Only by embedding adaptation across all levels of governance, mainstreaming it into every sector, and anchoring it in municipal planning instruments can the EU forge a coherent, multilevel regime capable of safeguarding all territories against escalating climate risks.

To overcome the limitations of this research, future studies should subject the scoring scale to rigorous expert-panel validation and embed field-based engagements with local and regional stakeholders across the EU-27 to verify that document-derived scores accurately reflect real-world practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, G.B.; methodology, M.C. and G.B.; formal analysis, M.C.; investigation, M.C.; resources, M.C.; data curation, M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C. and G.B; writing—review and editing, G.B.; visualisation, M.C.; supervision, G.B. M.C. conducted the research and drafted the manuscript under the guidance and supervision of G.B., who provided overall conceptual leadership, methodological oversight, and critical revision of the text. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are publicly available and were sourced from official and open-access repositories, including: the latest European Environment Agency (EEA) reports on climate hazards, vulnerabilities, and adaptation governance [1]; Climate-ADAPT, the European platform for climate adaptation knowledge, jointly managed by the European Commission and EEA [13]; Climate Change Laws of the World, a comparative database on national climate laws and policies [14]; the Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy, the EU initiative tracking local adaptation and mitigation plans [15]; UN-Habitat Urban Policy Platform, the repository of urban policies, including adaptation frameworks [16]; and Climate Watch, a global database aggregating national climate policies, targets, and commitments [17]. These sources are fully cited in the References section of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NAS |

National Adaptation Strategy |

| NAP |

National Adaptation Plan |

| RAP |

Regional Adaptation Plan |

| LAP |

Local Adaptation Plan |

| LTS |

Long-Term Strategy |

| NUP |

National Urban Policy |

| CoM |

Covenant of Mayors |

| EEA |

European Environment Agency |

| EU |

European Union |

| IPCC |

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

References

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Europe’s Changing Climate Hazards: State of Play 2023; EEA Report No. 04/2023; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, Luxembourg, 2023.

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2022. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/(accessed in July 2024).

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Urban Adaptation in Europe: How Cities and Towns Respond to Climate Change; EEA Report No. 12/2020; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, Luxembourg, 2020.

- Amundsen, H.; Berglund, F.; Westskog, H. Overcoming barriers to climate change adaptation: A question of multilevel governance? Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2010, 28, 276–289. [CrossRef]

- Rayner, T. Adaptation to climate change: EU policy on a Mission towards transformation? npj Clim. Action 2023, 2, 36. [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N. Scales of governance and environmental justice for adaptation to climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 2001, 11, 379–389. [CrossRef]

- Clar, C.; Prutsch, A.; Steurer, R. Barriers and guidelines for public policies on climate change adaptation: A missed opportunity of scientific knowledge-brokerage. Nat. Resour. Forum 2013, 37, 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy. The Multilevel Climate Action Playbook for Local and Regional Governments: Second Edition; Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy: Brussels, Belgium, 2023. Available online: https://www.globalcovenantofmayors.org/multilevel-climate-action-playbook-second-edition/(accessed on 25 May 2024).

- Betsill, M.M.; Bulkeley, H. Cities and the multilevel governance of global climate change. Glob. Gov. 2006, 12, 141–159.

- Bauer, A.; Feichtinger, J.; Steurer, R. The governance of climate change adaptation in ten OECD countries: Challenges and approaches. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2012, 14, 279–304. [CrossRef]

- Gilissen, H.K.; Alexander, M.; Matczak, P.; Pettersson, M.; Schellenberger, T. Bridges over troubled waters: An interdisciplinary framework for evaluating the interconnectedness within climate change adaptation policies. Reg. Environ. Change 2016, 16, 1389–1400. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Forging a Climate-Resilient Europe: The New EU Strategy on Adaptation to Climate Change; COM(2021) 82 final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021.

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 June 2021 establishing the framework for achieving climate neutrality (European Climate Law). Off. J. Eur. Union 2021, L243/1, 9 July 2021.

- Füssel, H.-M. Adaptation planning for climate change: Concepts, assessment approaches, and key lessons. Sustain. Sci. 2007, 2, 265–275. [CrossRef]

- Smit, B.; Burton, I.; Klein, R.J.T.; Street, R. The science of adaptation: A framework for assessment. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2000, 4, 199–213. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Glossary of Climate Change Terms. Available online: https://unfccc.int (accessed in July 2024).

- Termeer, C.J.A.M.; Dewulf, A.; Biesbroek, R. Transformational change: Governance interventions for climate change adaptation from a continuous change perspective. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2017, 60, 558–576. [CrossRef]

- Mees, H.L.P. Local governments in the driving seat? A comparative analysis of public and private responsibilities for adaptation to climate change in European and North-American cities. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2017, 19, 374–390. [CrossRef]

- Runhaar, H.A.C.; Uittenbroek, C.J.; van Rijswick, H.F.M.W.; Mees, H.L.P.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Gilissen, H.K. Prepared for climate change? A method for the ex-ante assessment of formal responsibilities for climate adaptation in specific sectors. Reg. Environ. Change 2016, 16, 1389–1400. [CrossRef]

- Juhola, S.; Westerhoff, L. Challenges of adaptation to climate change across multiple scales: A case study of network governance in two European countries. Environ. Sci. Policy 2011, 14, 239–247. [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; COM(2019) 640 final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Biesbroek, G.R.; Swart, R.J.; Carter, T.R.; Cowan, C.; Henrichs, T.; Mela, H.; Morecroft, M.D.; Rey, D. Europe adapts to climate change: Comparing national adaptation strategies. Glob. Environ. Change 2010, 20, 440–450. [CrossRef]

- Reckien, D.; Salvia, M.; Heidrich, O.; Church, J.M.; Pietrapertosa, F.; De Gregorio-Hurtado, S.; D’Alonzo, V.; Foley, A.; Simões, S.G.; Krkoška Lorencová, E. How are cities planning to respond to climate change? Assessment of local climate plans from 885 cities in the EU-28. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 191, 207–219. [CrossRef]

- Massey, E.; Biesbroek, R.; Huitema, D.; Jordan, A. Climate policy innovation: The adoption and diffusion of adaptation policies across Europe. Glob. Environ. Change 2014, 29, 434–443. [CrossRef]

- Termeer, C.J.A.M.; van Buuren, A.; Dewulf, A.; Huitema, D.; Mees, H.L.P.; Meijerink, S.; van Rijswick, M. Governance Arrangements for the Adaptation to Climate Change. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Climate Science; Oxford University Press: Oxford, United Kingdom, 2017.

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Advancing Towards Climate Resilience in Europe: Status of Reported National Adaptation Actions in 2021; EEA Report No. 11/2022; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022. ISBN 978-92-9480-423-8.

- European Commission; European Environment Agency (EEA). Climate-ADAPT Platform: Sharing Knowledge for a Climate-Resilient Europe. Available online: https://climate-adapt.eea.europa.eu (accessed in July 2024).

- Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment; London School of Economics (LSE). Climate Change Laws of the World Database. Available online: https://climate-laws.org (accessed in July 2024).

- Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy. Covenant of Mayors Official Website. Available online: https://www.covenantofmayors.eu (accessed in July 2024).

- UN-Habitat. Urban Policy Platform. Available online: https://urbanpolicyplatform.org (accessed in July 2024).

- World Resources Institute; Climate Watch. Climate Watch Platform. Available online: https://www.climatewatchdata.org (accessed in July 2024).

- Rauken, T.; Mydske, P.K.; Winsvold, M. Climate Change Adaptation through Municipal Planning in Norway: The Importance of Reforming the Planning System. Local Environ. 2015, 20, 408–423. [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C. Mainstreaming Ecosystem-Based Adaptation: Transformation toward Sustainability in Urban Governance and Planning. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 30. [CrossRef]

- Global Green Growth Institute (GGGI). Identifying Good Practices in National Adaptation Plans: A Global Review (GGGI Technical Report No. 36); Global Green Growth Institute: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).