1. Introduction

Scenario analysis is an integral tool in climate change research for exploring uncertainties in the assessment of potential future socioeconomic and physical impacts of climate change-related hazards such as heat stress, sea-level rise, or heavy precipitation (Moss et al. 2010; Ebi et al. 2014b). Socioeconomic scenarios, in particular, can inform mitigation and adaptation decisions as developments in socioeconomic conditions drive society’s adaptive capacity (Riahi et al. 2017) as well as potential exposure to climate change hazards (Hallegatte et al. 2011). For developing adaptation strategies at the local scale, socioeconomic scenarios need to reflect the local characteristics of the study area (Carlsen et al. 2013; Haasnoot et al. 2013; Walker et al. 2013). Local socioeconomic scenarios that are developed in collaboration with local stakeholders can, for instance, challenge perceptions and attitudes, encourage discussion about current issues, raise awareness, and serve as a tool to bridge knowledge gaps (Rotmans et al. 2000; Berkhout and Hertin 2002; Kok et al. 2007; Özkaynak and Rodríguez-Labajos 2010).

Previous work has proposed a range of approaches for developing locally relevant socioeconomic scenarios, ranging from top-down expert-led approaches to bottom-up stakeholder-led approaches. Top-down approaches are based on the assumption that socioeconomic developments at the local scale are embedded in the developments at regional, national, and global scales (van Vuuren et al. 2010; van Ruijven et al. 2014). Therefore, these approaches use existing global and/or regional socioeconomic scenarios as boundary conditions, which are downscaled based on the characteristics of the study area. These characteristics are established by integrating expert knowledge with literature review (Kok et al. 2006; Absar and Preston 2015; Kamei et al. 2016; Reimann et al. 2018; Kok et al. 2019). The advantage of top-down approaches is that the downscaled scenarios are consistent with the scenarios used as boundary conditions, which ensures comparability of studies across different regional contexts. However, scenarios developed exclusively using a top-down approach may not be relevant for local stakeholders, which limits their usability in local decision-making (Zurek and Henrichs 2007).

Bottom-up approaches, on the other hand, do not use existing scenarios to guide the scenario development process, but consult with local stakeholders from the beginning of the process, resulting in an original set of local socioeconomic scenarios (Reed et al. 2013; Gramberger et al. 2015; Berg et al. 2016; McBride et al. 2017; Palazzo et al. 2017; Pedde et al. 2018). Such stakeholder-led approaches ensure that the developed scenarios are tailored to the local characteristics of the study area, thereby creating a sense of ownership among stakeholders. As a result, the scenarios are more likely to be adopted as a decision tool at the local level, for instance as a basis for the development of local adaptation strategies (Berkhout and Hertin 2002; Reed et al. 2013; McBride et al. 2017).

This study has been designed as part of the EVOKED project

1, which has developed climate services in close collaboration with local stakeholders with the aim to support adaptation planning in five case-study regions across Europe (see section 2) (Swedish Geotechnical Institute 2018). The integration of local knowledge is one important precondition for a successful adaptation process (Oppenheimer et al. 2019). The project has employed a Living Lab (LL) approach, which puts the end-user (i.e. local stakeholders) at the center of the development process in order to ‘co-create’ and co-develop new knowledge, products or services (Robles et al. 2015; Evans et al. 2017; Dell'Era et al. 2019; Kolstad et al. 2019; Tiwari et al. 2022). The development of locally relevant socioeconomic scenarios is an integral component of such climate services as these scenarios provide the local basis for exploring different adaptation strategies. The project case studies are exposed to a variety of climate change-related hazards, which yield specific adaptation needs. Therefore, the socioeconomic scenarios need to reflect the local characteristics of each case study region.

To develop such locally relevant socioeconomic scenarios, we devise and apply a scenario development framework that combines elements of top-down and bottom-up scenario development approaches. Applying this framework, we produce local socioeconomic scenarios that integrate local stakeholder knowledge while at the same time harmonizing the scenario development process across case studies by using the same underlying scenarios as a starting point. Harmonization of the scenario development process ensures that the developed scenarios are internally consistent and coherent with the overarching scenarios used as boundary conditions, i.e. they follow the same scenario logic and the same underlying scenario assumptions, although storylines at the local scale may differ across case studies (Zurek and Henrichs 2007). In this way, scenarios become locally relevant and can be directly employed in local-level decision-making and planning processes. At the same time, more overarching conclusions can be drawn across case studies and results can be compared to studies in other regions that have used the same scenarios as boundary conditions for the development of local scenarios (Zandersen et al. 2019; Hagemann et al. 2020).

Our scenario development framework comprises a ‘multi-scale co-production approach’ where the developed local socioeconomic scenarios are coherent across multiple spatial scales (i.e. global – regional – local) (Biggs et al. 2007; Özkaynak and Rodríguez-Labajos 2010) and are co-produced in collaboration with local stakeholders. We have designed this approach specifically for the development of local socioeconomic scenario narratives, which are qualitative descriptions of plausible socioeconomic developments in the form of a story (Rotmans et al. 2000; Moss et al. 2010). We focus on the co-production of local scenario narratives as narratives ease the integration of local stakeholder knowledge into the scenario development process due to their typically non-scientific language (Nilsson et al. 2017). The local narratives constitute the basis for producing local-scale projections of key variables that need to be considered in adaptation planning, such as the spatial distribution of population and infrastructure (van Ruijven et al. 2014).

In the next sections, we provide a brief introduction into each case study region; present our ‘multi-scale co-production approach’ and explain how we use this approach to develop and implement the scenario framework in each case study region by tailoring it to the local stakeholder needs of the respective study area; compare the scenario outcomes across the case studies; and critically reflect upon the scenario development process and its potential use in climate impact research.

2. Case study regions

City of Larvik, Norway

As a coastal city located in southern Norway, Larvik is exposed to hazards and has historically experienced floods, strong winds, storms and storm surges. These events are expected to become more frequent and more intense with potentially increasing damage costs as a result of climate change (KSS 2023). In particular, the expected increase of extreme precipitation could lead to increases in intensity and frequency of urban flooding, erosion, quick clay slides, rock slides, and river flooding; while increases in storm activity in Skagerrak, in combination with a rising sea level, will increase the intensity and frequency of storm surges, coastal flooding, and erosion in Larvik.

Figure 1.

Map of the study region and case study areas.

Figure 1.

Map of the study region and case study areas.

According to the Civil Protection Act, all Norwegian municipalities have the obligation to carry out comprehensive risk and vulnerability assessments (RVA) which should be considered in land-use planning and should map potential impacts of climate change (Junker 2013). The municipality of Larvik aims to reduce both current and future risks due to climate change, through e.g. actions of its emergency preparedness group, or by incorporating adaptation analysis in all development projects.

As part of the last update of Larvik municipality's RVA, the potential impacts of climate change due to a range of natural hazards including intense rainfall, flooding, erosion, landslides, and storm surges were explored (NGI 2016). In this context, exposure maps for Larvik were developed and used for the building development of the Martineåsen area within the municipality, also accounting for a range of suggested local adaptation and mitigation measures; while the knowledge needs and perceptions of stakeholders were explored as input to the development of future socioeconomic scenarios that were relevant not only for the local authorities, but also the community of Larvik.

Värmland, Sweden

Värmland is an inland county located in Sweden that is exposed to flooding and other water-related hazards from Lake Vänern (the largest lake in the European Union) and river flows. The county capital of Karlstad situated on a delta where the Klarälven river meets Lake Vänern and has experienced several floods and landslides. In Värmlands county there is a need for new housing to deal with urbanization, especially in Karlstad. Smaller municipalities are losing population due to urbanisation migration to Karlstad and are using the possibility of living near the water as a way to attract people. This leads to more construction occurring close to the water today than previously, even though recent flooding events have put many areas at risk.

The Värmland County Administrative Board (VCAB) coordinates climate adaptation work in the county. It supports municipalities and other regional actors through awareness raising activities and disseminating knowledge about current and future climate change and climate change impacts. Within Värmland county, VCAB suggests measures which could help increase local and regional resilience to a changing climate; develops the Regional Climate Adaption Action Plans (Länsstyrelsen Värmland 2023a); and plays an active part in complying to the European Union Flood Directive. It focuses on adapting society to a changing climate to protect the environment, people and property in a long-term perspective.

Region of Northeast Brabant and Fluvius-region, the Netherlands

For the Netherlands, climate adaptation is often associated with flood risk (e.g. (Oliver et al. 2019). However, water scarcity, drought and heat stress are also considered as threats (Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Waterstaat 2020), particularly in the rural areas in the sandy east and south of the Netherlands, where drought is expected to become a problem (van den Eertwegh et al. 2019); while extreme rainfall and flooding are expected to occur more frequently. These hazards may affect both rural and urban areas (Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Waterstaat 2020). In response, the Deltaplan Spatial Adaptation (Deltaplan Ruimtelijke Adaptatie) was developed to help guide Dutch efforts (Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Waterstaat 2020) to such hazards. In this approach, the initial focus is to gain insights in the potential risks of climate change (stresstest), followed by the initiation of dialogues between local governmental bodies and regional stakeholders (e.g. agriculture, public healthcare, drinking water, nature) (risk dialogue) leading eventually to co-developing adaptation plans (regional adaptation strategy). Within this context both regions have developed a range climate services (Provincie Noord-Brabant 2020; Werkregio Fluvius 2022) and are currently in the process of consultation with regional stakeholders. For Platform Water Fluvius this has resulted in a regional adaptation strategy and regional implementation agenda, which acts as a strategic document for informing more localized climate adaptation plans for the Fluvius-partners (Werkregio Fluvius 2022). For the Province of North Brabant, this consultation has led to a vision on climate adaptation (2021) and is currently executing this vision within the climate program Netherlands-South (2022-2027) (Kennisportaal Klimaatadaptatie; Klimaatadaptatie 2021).

City of Flensburg, Germany

The city of Flensburg is located at the German Baltic Sea coast, directly at the national border to Denmark. The city is prone to coastal flooding during storm conditions, when a high-pressure system with winds from the northeast follows a low-pressure system with strong winds from the west, as these wind conditions can potentially result in a seiche over the entire Baltic Sea basin (Jensen and Mueller-Navarre 2008). The intensity and frequency of these flooding events are expected to increase over the next century and beyond due to accelerated sea-level rise (Sterr 2008; The BACC II Author Team 2015; Weiße and Meinke 2017; Oppenheimer et al. 2019). Currently, no assessment of vulnerability to coastal flooding exists for the city and no adaptation measures are in place apart from measures taken on an individual level (Hofstede 2008; Landesbetrieb für Küstenschutz, Nationalpark und Meeresschutz Schleswig-Holstein 2015). These household-level adaptation measures include sandbags and the installation of mobile barriers during flooding events (Ohlsen 2017; NDR 2019). Due to these circumstances, the city of Flensburg has recently initiated the process of developing an adaptation agenda, in cooperation with the local community. Furthermore, local stakeholders do not seem to favor conventional protection strategies in the form of engineered and built solutions, and appear more positive to alternative adaptation options for coping with future flood risk. In this context, the city can benefit from support in exploring potential adaptation options.

3. The multi-scale co-production approach for local scenario development

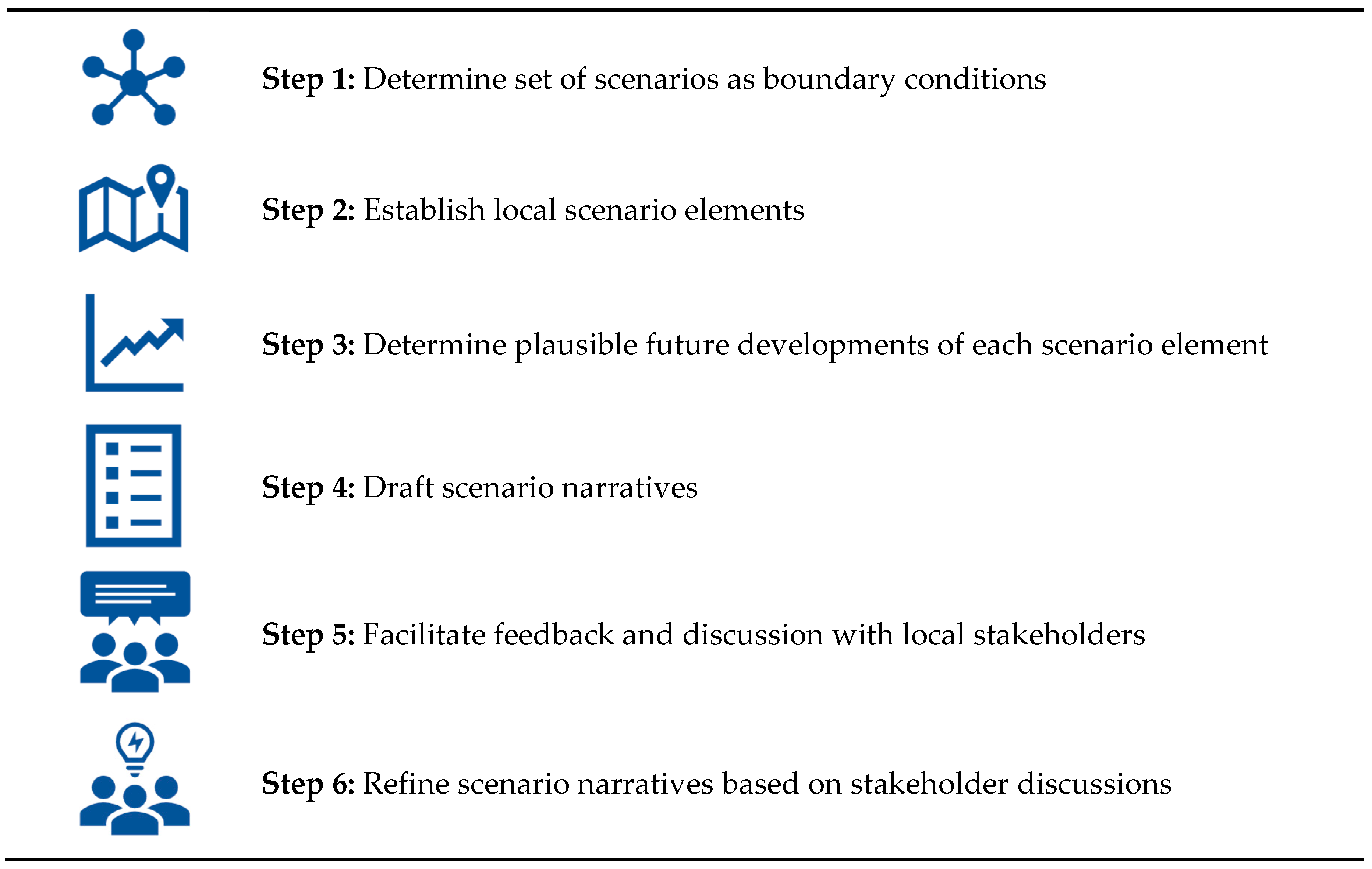

Our method is based on previous work by Rotmans et al. 2000 who developed scenarios for sustainable development in Europe, using a participatory scenario development approach. Rotmans and colleagues propose five steps to be taken during each stakeholder workshop. We adapt these steps to our approach and introduce an additional one, resulting in the following six steps shown in

Figure 2 and described below:

Step 1: Select scenarios as boundary conditions

When drafting local-scale socioeconomic scenarios, it is important to not only account for local developments, but also to consider that each case study is embedded in developments at different spatial scales, ranging from global to national, regional, and local levels (van Vuuren et al. 2010; van Ruijven et al. 2014). Therefore, we select scenarios covering all case study regions as boundary conditions for the local scenarios in a first step. This step needs to be taken jointly (i.e. with all those working on the different case studies) to ensure that the local socioeconomic scenarios are harmonized across case studies.

In EVOKED , we used the global-scale Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) as a starting point for providing the global context to the local scenario narratives as the SSPs are the current state-of-the-art socioeconomic scenarios used in climate change research (O’Neill et al. 2014; Abram et al. 2019). The SSPs describe five broad-scale pathways of plausible socioeconomic development until the end of the 21st century at a global scale, based on societal challenges for mitigation and adaptation (Kriegler et al. 2012; O’Neill et al. 2014). SSP1 ‘Sustainability’ describes a sustainable world with low challenges for both mitigation and adaptation; SSP2 ‘Middle of the Road’ is a scenario with moderate challenges; SSP3 ‘Regional Rivalry’ has high challenges; SSP4 ‘Inequality’ is characterized by high challenges for adaptation, but low challenges for mitigation; SSP5 ‘Fossil-fueled Development’ has low challenges for adaptation and high challenges for mitigation (O’Neill et al. 2017). Each SSP consists of a qualitative narrative and projections of several variables that have been produced on a national level, such as population (Kc and Lutz 2017), urbanization (Jiang and O’Neill 2017), and GDP (Dellink et al. 2017).

The SSPs have been intentionally designed in a broad manner to allow for the development of so-called ‘extended SSPs’ for sectoral and/or regional to local applications (Hunter and O'Neill 2014; O’Neill et al. 2014). More than thirty key elements that have been identified as important factors of socioeconomic development at the global scale are described in each global SSP narrative (O’Neill et al. 2017). As a result, the global narratives are generic enough to provide the overall socioeconomic context in each SSP while providing elements that are relevant to sub-global analyses as well (Ebi et al. 2014a; O’Neill et al. 2017). We use these scenario elements and their characteristics in each SSP as a starting point for the development of extended SSPs for each case study region.

Step 2: Establish local scenario elements

In Step 2, we extend the global SSP key elements by local scenario elements that are important drivers of societal development in each case study region. To establish local elements, we review the locally relevant literature, analyze data of the local and regional administrations and statistics offices, and/or consult with local stakeholders of each case study region. A number of guiding questions for each case study region have additionally driven the process to explore how drivers of socioeconomic development are embedded in the global to regional scale, which is an important aspect of multi-scale scenario development (Kok et al. 2007; Özkaynak and Rodríguez-Labajos 2010):

What is the demographic structure of the population? What are recent population trends?

What are the major issues of political and socioeconomic importance and/or concern in the case study region?

How are local politics embedded in regional, national and global politics?

How is the local economy embedded in global markets? What are the biggest companies in the case study region? Are they national, regional or global players?

As pointed out by Kok et al. 2007 and Özkaynak and Rodríguez-Labajos 2010, it is important to include local stakeholders at this stage of the process in order to confirm whether the established elements are relevant at the local scale and to establish potentially missing elements.

Once the local elements are established, we further select the global SSP elements that are most relevant to each case study region and extend them with the respective local SSP elements. By selecting only central global elements, we reduce the total number of scenario elements, thereby ensuring that the narrative is as short as possible to facilitate the communication with stakeholders (Özkaynak and Rodríguez-Labajos 2010).

Step 3: Determine plausible future developments of each scenario element

Based on current characteristics in socioeconomic development established by the literature review and analysis of regional socioeconomic data in Step 2, we proceed to define for each local scenario the characteristics of the scenario elements, including the newly established local elements as well as the selected global elements. As it is important to concentrate on a manageable number of scenarios to enhance communication and to facilitate productive discussion with local stakeholders, we propose using a set of three to four scenarios (Kok et al. 2006; Alcamo and Henrichs 2008; van der Heijden 2009). This number is sufficient to account for the full range of uncertainty regarding the challenges for mitigation and adaptation, as defined in the global SSPs (Carlsen et al. 2016).

To maintain consistency with the global SSPs, we use the developments of the global SSPs as a basis for each local scenario; adapt them where necessary to reflect the developments at local scale; and enhance them with further socioeconomic context based on the local elements. Here, it is important to develop plausible (at local level) assumptions of the future developments in each scenario in order to ensure that local stakeholders adopt the developed scenario narratives for local decision-making. Plausibility of scenarios is achieved if, based on their current knowledge and understanding of the world, stakeholders agree that the developments described in each scenario ‘could happen’ (Reimann et al. under review; based on Voros 2003; Reimann et al. 2021). We propose to assemble the results of Step 3 in a table in order to allow for comparing and contrasting the characteristics of all scenarios in a structured and clear manner (see Table x in SMx for an example).

Step 4: Draft scenario narratives

With the help of the table outlining the characteristics of the scenario narrative elements, a full-text narrative can been drafted for each scenario, describing the developments in each scenario qualitatively, in the form of a story (Rotmans et al. 2000; Moss et al. 2010). The narratives add further context to the scenario elements and are written in non-scientific language, with the aim to facilitate stakeholders’ understanding of each scenario (Nilsson et al. 2017). As pointed out by Kok et al. 2007, local stakeholders will be less overwhelmed by global developments, particularly social and economic developments, if they are not presented as facts but rather as underlying assumptions and changes in world views. In this step, we suggest giving each scenario a new name that reflects the overall socioeconomic developments in each narrative in a concise manner, also referring to the case study context. New scenario names are important for stakeholder identification with the local scenarios. Therefore, they should be developed in collaboration with the local stakeholders, aiming to create a sense of ownership among them (Kok et al. 2011).

Step 5: Facilitate feedback and discussion with local stakeholders

In Step 5, the first draft of the narratives along with the scenario names are discussed with the stakeholders of each case study to ensure plausibility and relevance of the local scenarios. In this context, it is essential to communicate to the stakeholders that scenarios are explorations of plausible futures rather than predictions of what will happen (Voros 2003; Alcamo and Henrichs 2008; Rounsevell and Metzger 2010). Therefore, it is important to note that the developed narratives can also reflect developments that are considered as less likely by the stakeholders (Kok et al. 2007). Depending on stakeholders’ background knowledge and prior experience with scenarios, sufficient time should be set aside for explaining these basic notions (Berkhout and Hertin 2002; Biggs et al. 2007).

Stakeholder interactions can take place in different communication formats, such as focus group discussions, interviews, expert workshops, or stakeholder workshops (Kok et al. 2007). In addition to the narrative text, other visualization tools should be used in order to ease understanding of each scenario, for instance pictures, collages, comics, graphs, an explanatory video, or a theatrical play (Kok et al. 2007; Kok and van Vliet 2011). It is important that the communication formats and visualization tools are selected based on the amount of time available and the previous experience of the stakeholders. Therefore, the project partners select those formats and tools most suitable for their case study region (Rotmans et al. 2000; Kok and van Vliet 2011).

In EVOKED, we aimed at including a broad group of stakeholders in the process as one important component of the Living Lab approach. Each project partner conducted a stakeholder analysis to establish the relevant stakeholders in each case study region using a snowballing method based on Reed et al. 2009. We aimed to include representatives from business, governments, NGOs, science/experts, and citizens of the case study region, following the recommendations of previous work (Kok et al. 2007; Kok et al. 2011; Kok et al. 2015).

Step 6: Refine scenario narratives based on stakeholder discussions

Based on the stakeholder feedback in Step 5, the narrative drafts are revised and adjusted to include the ideas and local knowledge of the stakeholders. Here, scenario experts weigh which points raised during the discussion to include in the scenario, thereby ensuring coherence across scales (i.e. with the global SSPs) (Zurek and Henrichs 2007) as well as consistency within each scenario narrative (Rotmans et al. 2000; Kok et al. 2007). Subsequently, the revised narrative drafts are discussed with the local stakeholders again to ensure that the scenarios are plausible and relevant at the local level. This process should be repeated in several iterations until the scenarios are fully approved by the stakeholders (Kok et al. 2015; Pedde et al. 2018). Depending on the time and resources available, this iterative process can take place in workshops or focus group discussions, but also remotely via email or during conference calls.

4. Implementation of the approach in each case study region

In this section, we describe how we applied the 6-step multi-scale co-production approach in each case study region and present the outcomes of this process.

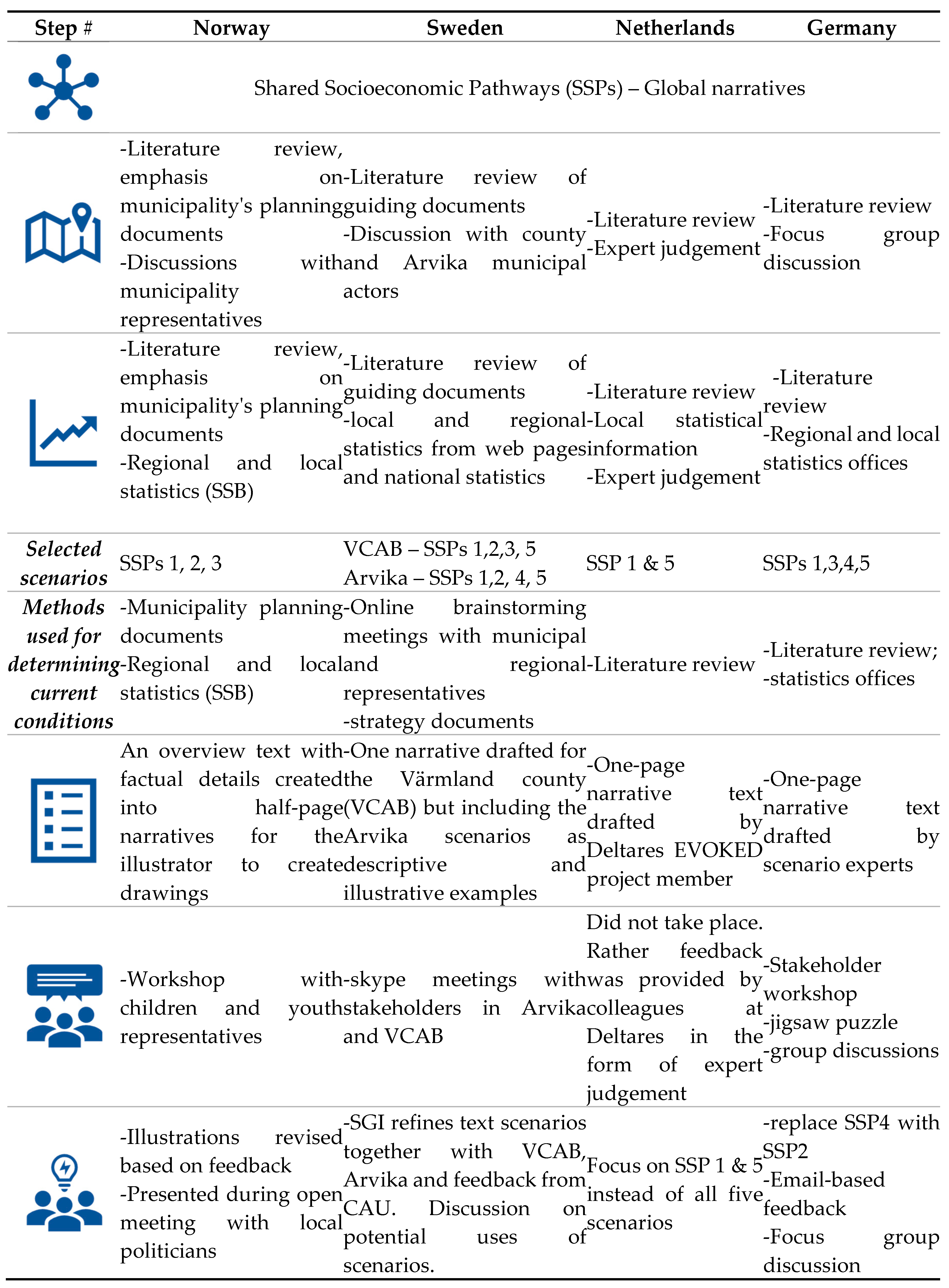

Table 1 provides an overview of how each step of the approach was tailored to the local particularities of each case study

City of Larvik, Norway

The local scenarios for Larvik were developed based on the five global-scale Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs). For step 1 and 2 relevant literature and data specific to Larvik were reviewed and analysed to investigate challenges and potential trends visible in Larvik today. Three of the global SSP were chosen, based on discussions with the municipality to select those SSPs which are considered most relevant for Larvik. The SSP selected included SSP1, SSP2 and SSP3, and plausible future developments were determined within each scenario element in step 3.

SSP1, "Sustainable Larvik", is mainly based on the municipal plans, as land-use plan and energy- and climate plan, as well as relevant strategies and action plans. This scenario reflects the Larvik that is currently planned for the future. SSP2, "Business as usual", is mainly based on relevant strategy documents and knowledge bases, discussing the situation in Larvik today. SSP3, "Regional rivalry", is also based on municipal strategies, but considered more as the scenario that could take place if the strategy "fails". Larvik and its neighbouring municipalities are already preparing for an anticipated centralization process towards the larger cities, especially in the Oslo region. Regional cooperation is therefore an important factor for the future of Larvik. However, if the regional municipalities are not able to compete at the same level as the neighbouring urban metropolitan areas, regional rivalry could result with these municipalities competing amongst one another.

In dialogue with the municipality, it was considered important not to develop dystopic scenarios, since Norway is a welfare state with quite robust safety net system for its citizens. The municipality did not believe such scenarios would be taken seriously by the stakeholders involved in their ongoing urban development plans (that the EVOKED project is following). Here, legitimacy was an important concern for the municipality and a desire to develop scenarios that people could relate to was considered as a better approach, especially regarding interests.

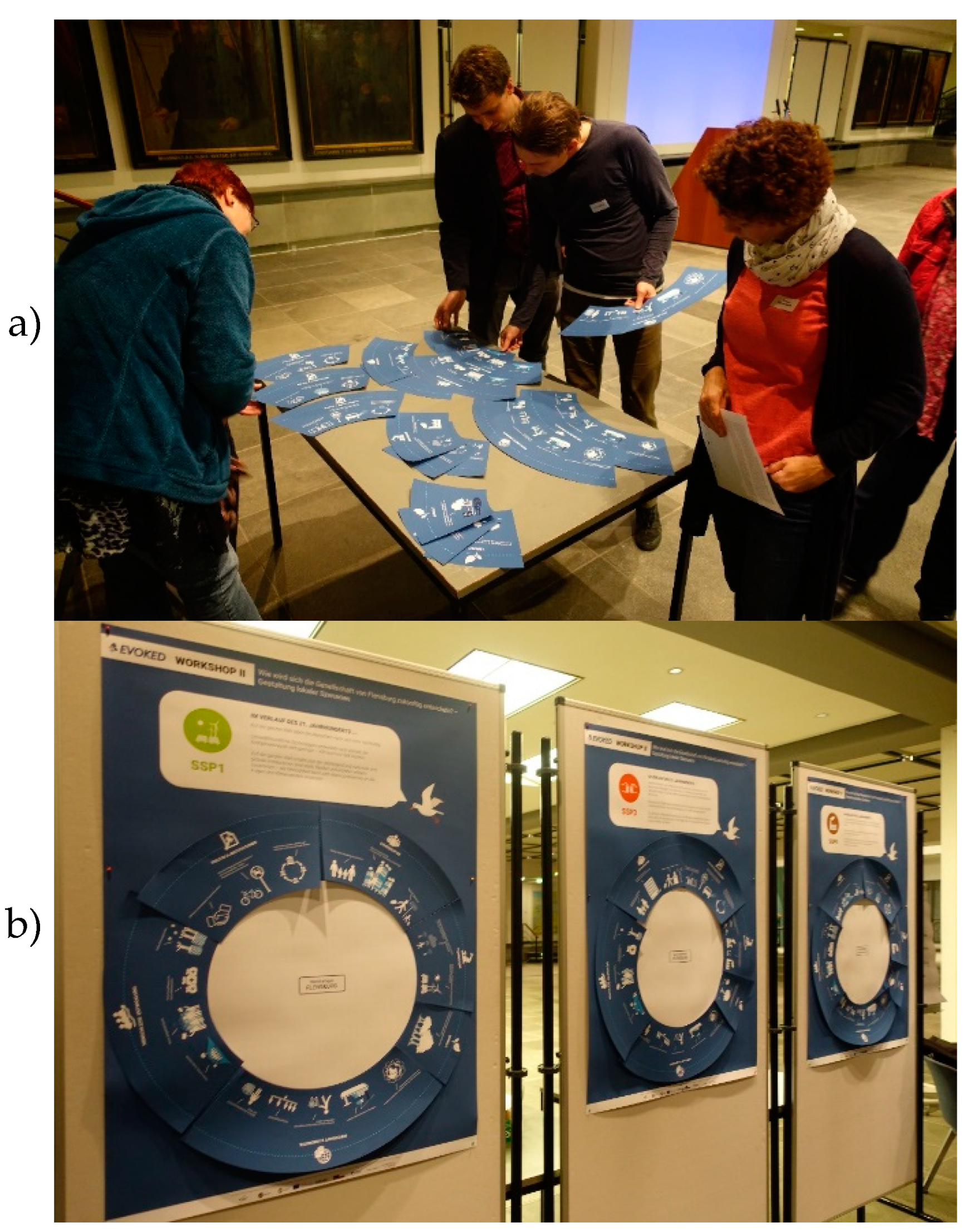

For step 4 the scenario table was drafted with partners from the municipality of Larvik, who identified information missing or not relevant. After the scenario table was completed, it was revised and rewritten into narratives. For step 5, the narratives were transformed into illustrations for children and youth (

Figure 3). The illustrations were then used in a workshop held at a primary school in Larvik. Feedback from the children and youth participants on these illustrations was then used for step 6, to further refine the illustrations. The final illustrations were presented to local politicians as part of a larger discussion on the development of the Martineåsen project. They formed the basis for a further dialog on how to use a blue-green factor tool to ensure a high quality of the blue-green infrastructure and how building developers incorporate stormwater runoff and infiltration in their projects to reduce the impact of urban flooding.

Värmland, Sweden

In step 1, we compiled a first draft of the local and regional scenario elements. SSP2 was based on current statistics for 2017-2018 on the home pages of Arvika municipality and Värmland county. SSP1 was based on strategic documents for sustainable development: Arvika’s Environmental strategy (Arvika Kommun 2015), Strategic plan for Arvika 2019-2020 (Arvika Kommun 2023), and Värmlandsstrategin 2014-2020 (Länsstyrelsen Värmland 2023b). SSPs 3,4 and 5 were based on what would happen if the strategies for sustainable development were only partially realized (SSP3 and 4) or not at all realized. In step 2, the scenario elements were discussed in an online meeting with representatives from VCAB and Arvika Teknik and Arvika municipality in September 2018 to determine the plausibility of the elements in each scenario and to select the scenarios that were most relevant.

In step 3 VCAB and Arvika representatives discussed the possibility ofo combining SSP3 (Regional rivalry) and SPP4 (Inequality: A more insular Arvika) into a single scenario and whether two separate scenarios, one for Arvika and one for the entire region (Värmland), were required. SSP3 was relevant in the debate about larger regions in Sweden, but SSP4 was more relevant for the local conditions in Arvika. The decision was taken to develop two separate scenarios, one for Arvika using SSP4 and one for VCAB using SSP3. The other SSP-based scenarios would remain the same, as well as the global and local elements, but the weighting and description of the elements were different. A first draft of the scenario narratives was compiled in step 4; this was subsequently discussed and revised by both VCAB and Arvika who each suggested changes and additions to the narratives to make them more plausible and relevant. Eventually, the local and county scenarios were merged into one narrative for the entire county of Värmland and use the Arvika scenarios as local examples. In steps 5 and 6 additional stakeholders in VCAB and Arvika were brought in during separate meetings to discuss the potential usefulness of the scenarios. For VCAB the scenarios could be used as input in the municipality’s work with a regional climate adaptation strategy. For Arvika they could be used in Comprehensive Plans or Risk and Vulnerability assessments, particularly for the building and planning section (Samhällsplanering) and less so for the technical sections (Teknik i väst).

Region of Northeast Brabant and Fluvius-region, Netherlands

For the Netherlands, national scenarios with detailed narratives (the “Delta-scenarios) that had been developed in consultation with stakeholders already existed (Wolters et al. 2018). These scenarios describe potential development paths for the Netherlands along two axes: with regard to climate change (“slow and little amount of climate impact vs fast and large amount of climate impact”) and socio-economic trends (“socio-economic shrinkage vs socio-economic growth”). As these scenarios match some of the SSP scenarios, and are at the same time relevant for the local studies in the Netherlands, they were also employed for the local scenario development by adjusting the six-step approach presented in section 3.

In the first step the five SSP scenarios were translated into potential developmental storylines for the case study areas. Then, we established local scenario elements based on literature specific to the case study areas, on the “Delta Scenarios” (Wolters et al. 2018) and on (local) statistical data and trends that are available for both regions. (Commission and Eurostat 2019). We employed the “Delta-scenarios” (Wolters et al. 2018) as a basis for extending the plausible future development of each scenario element and focused on the scenarios ‘Rest’ and ‘Steam’. These correspond with SSP 1 & 5, which we believe best cover the solution space for the future development of the study areas. Based on the local data and the narrative described in the Delta-Scenarios, we developed narratives for both selected SSP scenarios. For step 5 (asking feedback) we made use of expert judgement from colleagues working at Deltares that are involved in their daily work with scenario development in regard to climate change impacts in the Netherlands. This judgement involved the plausibility of the developments described in the first draft of the local SSP scenarios. Based on the feedback we made final adjustments to the developed scenario drafts for SSP 1 & 5.

City of Flensburg, Germany

The local scenario development process in the city of Flensburg closely followed the six-step approach (see Reimann et al. 2021). We established local scenario elements (Step 2) based on literature specific to the case study (Beer et al. 2013; IHR Sanierungsträger 2016; City of Flensburg 2017, 2018; Staudt 2018) and on the analysis of data of the local and regional administrations and statistics offices (Statistisches Amt für Hamburg und Schleswig-Holstein 2018; City of Flensburg 2019). We discussed the preliminary local scenario elements with Flensburg’s city administration in a focus group of four participants. During this discussion, we presented the local elements and asked participants to identify missing elements as well as items that were not relevant for the city of Flensburg. Subsequently, we devised the plausible future developments of each scenario element for four selected SSPs, ensuring coherence of the local-scale scenarios with the global SSPs. We chose SSPs 1, 3, 4 and 5 with the aim to span the full range of uncertainty regarding the challenges for mitigation and adaptation as defined in the SSPs. Step 3 resulted in a table outlining the future characteristics of each scenario element for each selected SSPs. Based on this table, we drafted a one-page narrative for each scenario (Step 4). We further devised new scenario names that reflect the local developments described in each narrative.

In Step 5, we discussed the local scenario narrative drafts in a stakeholder workshop, which we co-organized with Flensburg’s city administration. We focused on three scenarios (SSP1, SSP3 and SSP5) due to the number of workshop participants (13 stakeholders) and time constraints (half-day workshop). Following Kok and van Vliet 2011, we used a mix of visualization tools and formats of interaction to address a range of perceptions and tastes. At the beginning of the workshop (phase 1), a scenario expert provided general information of the SSP framework to the stakeholders via a flip chart presentation. In order to obtain a better understanding for each scenario, the stakeholders assigned the different scenario elements and their characteristics to the respective SSP in a second phase. Similar to a jigsaw puzzle, the task was to use graphical elements of the SSPs cut into several pieces and organize them on a poster (

Figure 4).

In phase 3, the narratives were discussed in smaller groups, with each group discussing one SSP. As our aim was to initiate a lively discussion of the narrative drafts, we decided upon a group size of four to five participants for each scenario. We asked the workshop participants to give feedback on the identified elements; report on missing ones; and to provide feedback on the narratives as a whole. After the discussion in smaller groups, we reflected upon all comments with all workshop participants. During this phase, the stakeholders identified the need for a scenario reflecting current development trends in Flensburg.

In Step 6, we integrated the stakeholder comments into each narrative. It was not possible to include all comments into the local scenarios as some contradicted with the developments described in the global narrative of the respective SSP. We sent the revised narratives to the stakeholders via email for a second round of comments. We also attached a justification and explanation document in those cases where we could not include specific comments. As we received further minor comments on SSP1 ‘Sustainable Flensburg’, we changed the narrative accordingly. We additionally replaced the SSP4-based narrative ‘Flensburg’s elites on the rise’ (which was not discussed during the workshop) with the newly devised SSP2-based narrative ‘Flensburg as we know it’ in order not to exceed a total number of four scenarios. We presented this narrative to representatives of Flensburg’s city administration for their comments on its plausibility before finalizing it.

5. Discussion and conclusions

In the context of the EVOKED project, we developed a set of local scenarios, following the common for all five case studies, stepwise approach described in section 3. The combination of a top-down (Steps 1-4) with a bottom-up approach (Steps 5-6) has resulted in sets of scenarios that are locally relevant and accepted by the potential end-users. At the same time, the developed scenarios are consistent with the global scenarios that were used as boundary conditions (i.e. the SSP) and are therefore comparable with, or complementary to, other downscaled scenarios developed in different regions or in different contexts.

Despite the distinct local context of each case study of EVOKED, the scenarios developed for the five case studies are similar in terms of the SSP that were selected by the stakeholders of every case study. The same trend was also observed in Kok and van Vliet 2011. In all case studies there was a clear preference for a local SSP1 to be developed, while three of the project partners developed local extensions for SSP2, SSP3 and SSP5. In particular, the inclusion of SSP2 was, in most cases, included following the demand of the stakeholders. This is possibly due to the nature of the SSP2 which, as a middle of the road scenario, entails less extreme change and its storyline is therefore closer to what stakeholders can envisage and project. The overall choice of scenarios appears to reflect current discussions in climate policy and the general political landscape, with society being torn between sustainable solutions, the use of fossil fuels, and the increasing tendency to protect regional markets. Nevertheless, the participatory approach leads to a shift from “typical” key elements (economic, demographic, technological) to socio-cultural, political and institutional elements (Rotmans et al. 2000).

Our approach leads to the development of sets of scenarios that are consistently informed by global developments as well as by local participatory processes, thus being locally credible and relevant to the needs of stakeholders. The methods leave ample room for interpretation in order to develop the scenarios based on the specific context of each case study (Swart et al., 2004) but are still coherent with the SSPs, thus avoiding a range of very different scenarios that do not allow for cross-case comparisons (van Ruijven et al. 2014; Zandersen et al. 2019). As such, they are characterized by internal consistency and similarity despite possible differences between them (Pedde et al., 2021). Such scenarios allow for adaptation options to be explored across plausible futures, trust to be built in the context of participatory processes, local values to be understood by the developers and policies to be more robust under changing climate conditions (Frame et al. 2018). As the developed scenarios allow for exploring a wide range of societal futures and the resulting plausible future climate change impacts, they provide an important basis for supporting adaptation planning in each project case study. Importantly, coherence further leads to consistency between spatial scales , which is particularly important in the context of climate change adaptation (Kok and van Vliet 2011).

The developed narratives also provide the basis for quantifying trends of socioeconomic development and for producing local-scale projections of socioeconomic variables that can directly feed into the analysis of risk and consequently guide the adaptation process. Examples of such variables are spatial population distributions, distribution of income, age groups, and land use changes under each scenario. For example, population projections that can be used as a basis for assessing population exposure and vulnerability to the potential impacts of climate change. Using the same model for all case studies allows for using projection input data from the same baseline scenarios (SSPs) (Kok and Pedde 2016, 2016; Hagemann et al. 2020), thus making the quantified projections consistent across the case studies. Further, the narratives constitute a climate service per se as they raise stakeholder awareness of the processes that will drive risk, exposure, and adaptive capacity in the future and provide context for stakeholder discussions on mitigation and adaptation strategies and pathways (Kok and Pedde, 2016) by comparing scenarios to determine most desirable pathway and devise policies to achieve the vision (Özkaynak and Rodríguez-Labajos 2010).

The process of co-developing local scenarios with stakeholders also has some drawbacks and challenges to overcome. The quality of the stakeholder feedback largely depends on the stakeholders’ background knowledge and participation. Regional long-term scenarios did not generally exist in most of our case studies and only few stakeholders had previous experience in the field of scenario development and analysis. In this context, exploring plausible future socioeconomic developments until 2100 can be rather abstract to stakeholders, who require time to fully immerse in the storylines discussed. For this reason, thorough preparation of the stakeholder workshop and the use of visualization techniques and material, such as figures, graphs, animations, and posters, is essential for facilitating comprehension. Further, we have observed that exercises in small groups can be particularly useful as these result in more lively discussions that help participants to engage in the topic, especially in those cases where the group of stakeholders is very diverse in terms of roles and background.

Second, achieving coherence between scenarios from different case studies may lead to loss of variety (Kok and van Vliet 2011) as the use of common scenario elements can lead to the developed scenarios being too rigid or restricted. Kok et al. 2007 propose that formal downscaling should be attempted only if there is particular scientific or policy value; if the aim is primarily to aid decision making constructing the scenarios for each scale using a broad common framework could suffice.

Third, aligning new scenarios with already existing scenarios at a national level that are accepted and used my stakeholders is a complex process. In EVOKED, for the Dutch case studies, we decided to map the already established national scenarios to the SSP. However, this is not a straightforward task and may introduce uncertainties when comparing case studies. Similarly, Hagemann et al.(2020) note that if stakeholders are free to choose scenarios, the outcomes may eventually look very different, reflecting to a greater extent the local logic based on cultural and geomorphological conditions (Hagemann et al. 2020).

Further work to tackle some of the above limitations could involve at improved implementation of the participatory part of the process, in line with the elements of a Living Lab. Moreover, integrating stakeholders right from the start of the scenario development and increasing the iterations with the stakeholders would allow further integration of local knowledge. However, time availability often constitutes a major constraint in this process. Last, we must note that the development of scenarios has only constituted one aspect of the EVOKED project in the process of the production of climate services. Therefore, the proposed method should be considered in this context and adapted in projects or analysis that for example focus entirely on scenario development (e.g. MedAction, Visions).

References

- Abram N, Gattuso J-P, Prakash A, Cheng L, Chidichimo MP, Crate S, Enomoto H, Garschagen M, Gruber N, Harper S, Holland E, Kudela RM, Rice J, Steffen K, von Schuckmann K (2019) Framing and Context of the Report. In: Pörtner H-O, Roberts DC, Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Tignor M, Poloczanska E, Mintenbeck K, Alegria A, Nicolai M, Okem A, Petzold J, Rama B, Weyer NM (eds) IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cyrosphere in a Changing Climate, in press.

- Absar SM, Preston BL (2015) Extending the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways for sub-national impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability studies. Global Environmental Change 33:83–96. [CrossRef]

- Alcamo J, Henrichs T (2008) Chapter Two Towards Guidelines for Environmental Scenario Analysis. In: Alcamo J (ed) Environmental futures: The practice of environmental scenario analysis, vol 2. Developments in Integrated Environmental Assessment, v. 2, 1st edn. Elsevier, Amsterdam, Boston, pp 13–35.

- Arvika Kommun (2015) Miljöstrategi för Arvika kommun. https://www.arvika.se/kommunochpolitik/planerochstyrandedokument/forfattningssamling/bestammelser/miljostrategi.2478.html. Accessed 22 September 2023.

- Arvika Kommun (2023) Strategisk plan 2024-2026 - Budget 2024. https://www.arvika.se/download/18.39e0dd96188d6b45c534fd/1692092130920/Strategisk%20plan%202024-2026.pdf. Accessed 22 September 2023.

- Beer M, Jahn M, Kovac E, Köster H, Laros S, Maas H (2013) Masterplan 100% Klimaschutz Flensburg: CO2-Neutralität und Halbierung des Energiebedarfs bis zum Jahr 2050.

- Berg C, Rogers S, Mineau M (2016) Building scenarios for ecosystem services tools: Developing a methodology for efficient engagement with expert stakeholders. Futures 81:68–80. [CrossRef]

- Berkhout F, Hertin J (2002) Foresight Futures Scenarios. Greener Management International 2002(37):37–52. [CrossRef]

- Biggs R, Raudsepp-Haerne C, Atkinson-Palombo C, Bohensky E, Boyd E, Cundill G, Fox H, Ingram S, Kok K, Spehar S, Tengö M, Timmer D, Zurek M (2007) Linking Futures across Scales: a Dialog on Multiscale Scenarios. Ecology and Society 12(1).

- Carlsen H, Dreborg KH, Wikman-Svahn P (2013) Tailor-made scenario planning for local adaptation to climate change. Mitig Adapt Strateg Glob Change 18(8):1239–1255. [CrossRef]

- Carlsen H, Eriksson EA, Dreborg KH, Johansson B, Bodin Ö (2016) Systematic exploration of scenario spaces. Foresight 18(1):59–75. [CrossRef]

- City of Flensburg (2017) Stadtportrait. https://www.flensburg.de/Leben-Soziales/Stadtportrait. Accessed 18 September 2019.

- City of Flensburg (2018) Perspektiven für Flensburg: Ein integriertes Stadtentwicklungskonzept. Konzept und Maßnahmen.

- City of Flensburg (2019) Statistik. https://www.flensburg.de/Politik-Verwaltung/Stadtverwaltung/Statistik. Accessed 18 September 2019.

- Commission E, Eurostat (2019) Eurostat regional yearbook – 2019 edition. Publications Office.

- Dell'Era C, LANDONI P, GONZALEZ SJ (2019) Investigating the innovation impacts of user-centred and participatory strategies adopted by European Living Labs. Int. J. Innov. Mgt. 23(05):1950048. [CrossRef]

- Dellink R, Chateau J, Lanzi E, Magné B (2017) Long-term economic growth projections in the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Global Environmental Change 42:200–214. [CrossRef]

- Ebi KL, Hallegatte S, Kram T, Arnell NW, Carter TR, Edmonds J, Kriegler E, Mathur R, O’Neill BC, Riahi K, Winkler H, van Vuuren DP, Zwickel T (2014a) A new scenario framework for climate change research: Background, process, and future directions. Climatic Change 122(3):363–372. [CrossRef]

- Ebi KL, Kram T, van Vuuren DP, O'Neill BC, Kriegler E (2014b) A New Toolkit for Developing Scenarios for Climate Change Research and Policy Analysis. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 56(2):6–16. [CrossRef]

- Evans P, Schuurmann D, Stahlbröst A, Vervoort K (2017) Living Lab Methodology Handbook.

- Frame B, Lawrence J, Ausseil A-G, Reisinger A, Daigneault A (2018) Adapting global shared socio-economic pathways for national and local scenarios. Climate Risk Management 21:39–51. [CrossRef]

- Gramberger M, Zellmer K, Kok K, Metzger MJ (2015) Stakeholder integrated research (STIR): A new approach tested in climate change adaptation research. Climatic Change 128(3-4):201–214. [CrossRef]

- Haasnoot M, Kwakkel JH, Walker WE, ter Maat J (2013) Dynamic adaptive policy pathways: A method for crafting robust decisions for a deeply uncertain world. Global Environmental Change 23(2):485–498. [CrossRef]

- Hagemann N, van der Zanden EH, Willaarts BA, Holzkämper A, Volk M, Rutz C, Priess JA, Schönhart M (2020) Bringing the sharing-sparing debate down to the ground—Lessons learnt for participatory scenario development. Land Use Policy 91:104262. [CrossRef]

- Hallegatte S, Przyluski V, Vogt-Schilb A (2011) Building world narratives for climate change impact, adaptation and vulnerability analyses. Nature Climate change 1(3):151–155. [CrossRef]

- Hofstede J (2008) Coastal Flood Defence and Coastal Protection along theBaltic Sea Coast of Schleswig-Holstein. Die Küste 74:170–178.

- Hunter LM, O'Neill BC (2014) Enhancing engagement between the population, environment, and climate research communities: The shared socio-economic pathway process. Population and environment 35:231–242. [CrossRef]

- IHR Sanierungsträger (2016) Stadt Flensburg Vorbereitende Untersuchungen Hafen-Ost: Öffentlichkeitsbeteiligung. Ergebnisse des Experten-Workshops am 13. Oktober 2016.

- Jensen J, Mueller-Navarre SH (2008) Storm Surges on the German Coast. Die Küste 74:92–124.

- Jiang L, O’Neill BC (2017) Global urbanization projections for the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Global Environmental Change 42:193–199. [CrossRef]

- Junker E (2013) Legal requirements for risk and vulnerability assessments in Norwegian land-use planning. Local Environment 20(4):474–488. [CrossRef]

- Kamei M, Hanaki K, Kurisu K (2016) Tokyo’s long-term socioeconomic pathways: Towards a sustainable future. Sustainable Cities and Society 27:73–82. [CrossRef]

- Kc S, Lutz W (2017) The human core of the shared socioeconomic pathways: Population scenarios by age, sex and level of education for all countries to 2100. Global environmental change : human and policy dimensions 42:181–192. [CrossRef]

- Kennisportaal Klimaatadaptatie Zuid-Nederland stelt uitvoeringsagenda op om klimaatbestendig te worden. https://klimaatadaptatienederland.nl/@249259/zuid-nederland-uitvoeringsagenda/. Accessed 25 September 2023.

- Klimaatadaptatie (2021) Zuid-Nederland stelt uitvoeringsagenda op om klimaatbestendig te worden. https://klimaatadaptatienederland-nl.translate.goog/?_x_tr_sl=auto&_x_tr_tl=de&_x_tr_hl=de&_x_tr_hist=true#canvas. Accessed 25 September 2023.

- Kok K, Bärlund I, Flörke M, Holman I, Gramberger M, Sendzimir J, Stuch B, Zellmer K (2015) European participatory scenario development: Strengthening the link between stories and models. Climatic Change 128(3-4):187–200. [CrossRef]

- Kok K, Biggs R, Zurek M (2007) Methods for Developing Multiscale Participatory Scenarios: Insights from Southern Africa and Europe. Ecology and Society 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Kok K, Pedde S (2016) IMPRESSIONS socio-economic scenarios: Deliverable D2.2. http://www.impressions-project.eu/getatt.php?filename=D2.2_Socioeconomic_Scenarios_FINAL_14009.pdf. Accessed 18 April 2018.

- Kok K, Pedde S, Gramberger M, Harrison PA, Holman IP (2019) New European socio-economic scenarios for climate change research: Operationalising concepts to extend the shared socio-economic pathways. Reg Environ Change 19(3):643–654. [CrossRef]

- Kok K, Rothman DS, Patel M (2006) Multi-scale narratives from an IA perspective: Part I. European and Mediterranean scenario development. Futures 38(3):261–284. [CrossRef]

- Kok K, van Vliet M (2011) Using a participatory scenario development toolbox: Added values and impact on quality of scenarios. Journal of Water and Climate Change 2(2-3):87–105. [CrossRef]

- Kok K, van Vliet M, Bärlund I, Dubel A, Sendzimir J (2011) Combining participative backcasting and exploratory scenario development: Experiences from the SCENES project. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 78(5):835–851. [CrossRef]

- Kolstad EW, Sofienlund ON, Kvamsås H, Stiller-Reeve MA, Neby S, Paasche Ø, Pontoppidan M, Sobolowski SP, Haarstad H, Oseland SE, Omdahl L, Waage S (2019) Trials, Errors, and Improvements in Coproduction of Climate Services. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 100(8):1419–1428. [CrossRef]

- Kriegler E, O’Neill BC, Hallegatte S, Kram T, Lempert RJ, Moss RH, Wilbanks T (2012) The need for and use of socio-economic scenarios for climate change analysis: A new approach based on shared socio-economic pathways. Global Environmental Change 22(4):807–822. [CrossRef]

- KSS (2023) Klimaprofil Vestfold - Norsk klima service senter. https://klimaservicesenter.no/kss/klimaprofiler/vestfold. Accessed 22 September 2023.

- Landesbetrieb für Küstenschutz, Nationalpark und Meeresschutz Schleswig-Holstein (2015) Fachplan Küstenschutz Ostseeküste.

- Länsstyrelsen Värmland (2023a) Värmland i ett förändrat klimat: Plan för vad Länsstyrelsen Värmland behöver göra - Handlingsplan och myndighetsmål 2020–2025. https://catalog.lansstyrelsen.se/store/38/resource/4. Accessed 22 September 2023.

- Länsstyrelsen Värmland (2023b) Värmland i ett förändrat klimat - Regional handlingsplan för klimatanpassning 2014.

- McBride MF, Lambert KF, Huff ES, Theoharides KA, Field P, Thompson JR (2017) Increasing the effectiveness of participatory scenario development through codesign. E&S 22(3).

- Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Waterstaat (2020) NATIONAL DELTA PROGRAMME, The Hague.

- Moss RH, Edmonds JA, Hibbard KA, Manning MR, Rose SK, van Vuuren DP, Carter TR, Emori S, Kainuma M, Kram T, Meehl GA, Mitchell JFB, Nakicenovic N, Riahi K, Smith SJ, Stouffer RJ, Thomson AM, Weyant JP, Wilbanks TJ (2010) The next generation of scenarios for climate change research and assessment. Nature 463(7282):747–756. [CrossRef]

- NDR (2019) Sturmtief "Zeetje" brachte Hochwasser. https://www.ndr.de/nachrichten/schleswig-holstein/Sturmtief-Zeetje-brachte-Hochwasser,sturm2742.html. Accessed 25 October 2019.

- NGI (2016) Lardal og Larvik kommuner – tilpasning til klimaendringer. Vurderinger og ekstrem nedbør, skred, flom, stormflo og havnivåstigning.

- Nilsson AE, Bay-Larsen I, Carlsen H, van Oort B, Bjørkan M, Jylhä K, Klyuchnikova E, Masloboev V, van der Watt L-M (2017) Towards extended shared socioeconomic pathways: A combined participatory bottom-up and top-down methodology with results from the Barents region. Global Environmental Change 45:124–132. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill BC, Kriegler E, Ebi KL, Kemp-Benedict E, Riahi K, Rothman DS, van Ruijven BJ, van Vuuren DP, Birkmann J, Kok K, Levy M, Solecki W (2017) The roads ahead: Narratives for shared socioeconomic pathways describing world futures in the 21st century. Global Environmental Change 42:169–180. [CrossRef]

- O’Neill BC, Kriegler E, Riahi K, Ebi KL, Hallegatte S, Carter TR, Mathur R, van Vuuren DP (2014) A new scenario framework for climate change research: The concept of shared socioeconomic pathways. Climatic Change 122(3):387–400. [CrossRef]

- Ohlsen H (2017) Keine Deiche, Sperrwerke oder mobile Sicherungseinheiten: „Wir haben nur Sandsäcke!“. Flensburger Tageblatt.

- Oliver J, Qin XS, Madsen H, Rautela P, Joshi GC, Jorgensen G (2019) A probabilistic risk modelling chain for analysis of regional flood events. Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess 33(4-6):1057–1074. [CrossRef]

- Oppenheimer M, Glavovic BC, Hinkel J, van de Wal R, Magnan AK, Abd-Elgawad A, Cai R, Cifuentes-Jara M, DeConto RM, Ghosh T, Hay J, Isla F, Marzeion B, Meyssignac B, Sebesvari Z (2019) Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low-Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities. In: Pörtner H-O, Roberts DC, Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Tignor M, Poloczanska E, Mintenbeck K, Alegria A, Nicolai M, Okem A, Petzold J, Rama B, Weyer NM (eds) IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cyrosphere in a Changing Climate, in press.

- Özkaynak B, Rodríguez-Labajos B (2010) Multi-scale interaction in local scenario-building: A methodological framework. Futures 42(9):995–1006. [CrossRef]

- Palazzo A, Vervoort JM, Mason-D'Croz D, Rutting L, Havlík P, Islam S, Bayala J, Valin H, Kadi Kadi HA, Thornton P, Zougmore R (2017) Linking regional stakeholder scenarios and shared socioeconomic pathways: Quantified West African food and climate futures in a global context. Global environmental change : human and policy dimensions 45:227–242. [CrossRef]

- Pedde S, Kok K, Onigkeit J, Brown C, Holman I, Harrison PA (2018) Bridging uncertainty concepts across narratives and simulations in environmental scenarios. Reg Environ Change 250(1–14):145. [CrossRef]

- Provincie Noord-Brabant (2020) Home - Klimaatadaptatie Provincie Noord-Brabant. https://www.klimaatadaptatiebrabant.nl/. Accessed 25 September 2023.

- Reed MS, Graves A, Dandy N, Posthumus H, Hubacek K, Morris J, Prell C, Quinn CH, Stringer LC (2009) Who's in and why? A typology of stakeholder analysis methods for natural resource management. Journal of environmental management 90(5):1933–1949. [CrossRef]

- Reed MS, Kenter J, Bonn A, Broad K, Burt TP, Fazey IR, Fraser EDG, Hubacek K, Nainggolan D, Quinn CH, Stringer LC, Ravera F (2013) Participatory scenario development for environmental management: a methodological framework illustrated with experience from the UK uplands. Journal of environmental management 128:345–362. [CrossRef]

- Reimann L, Merkens J-L, Vafeidis AT (2018) Regionalized Shared Socioeconomic Pathways: Narratives and spatial population projections for the Mediterranean coastal zone. Reg Environ Change 18(1):235–245. [CrossRef]

- Reimann L, Vollstedt B, Koerth J, Tsakiris M, Beer M, Vafeidis AT (under review) Developing extended Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) for the city of Flensburg, north Germany: a multi-scale co-production approach. Futures:revised version submitted.

- Reimann L, Vollstedt B, Koerth J, Tsakiris M, Beer M, Vafeidis AT (2021) Extending the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) to support local adaptation planning—A climate service for Flensburg, Germany. Futures 127(9):102691. [CrossRef]

- Riahi K, van Vuuren DP, Kriegler E, Edmonds J, O’Neill BC, Fujimori S, Bauer N, Calvin K, Dellink R, Fricko O, Lutz W, Popp A, Cuaresma JC, Kc S, Leimbach M, Jiang L, Kram T, Rao S, Emmerling J, Ebi K, Hasegawa T, Havlik P, Humpenöder F, Da Silva LA, Smith S, Stehfest E, Bosetti V, Eom J, Gernaat D, Masui T, Rogelj J, Strefler J, Drouet L, Krey V, Luderer G, Harmsen M, Takahashi K, Baumstark L, Doelman JC, Kainuma M, Klimont Z, Marangoni G, Lotze-Campen H, Obersteiner M, Tabeau A, Tavoni M (2017) The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: An overview. Global Environmental Change 42:153–168. [CrossRef]

- Robles AG, Hirvikoski T, Schuurman D, Stokes L (2015) Introducing ENoLL and its Living Lab Community.

- Rotmans J, van Asselt M, Anastasi C, Greeuw S, Mellors J, Peters S, Rothman D, Rijkens N (2000) Visions for a sustainable Europe. Futures 32(9-10):809–831. [CrossRef]

- Rounsevell MDA, Metzger MJ (2010) Developing qualitative scenario storylines for environmental change assessment. WIREs Clim Change 1(4):606–619.

- Statistisches Amt für Hamburg und Schleswig-Holstein (2018) Regionaldaten für Flensburg. http://region.statistik-nord.de/detail/0010000000000000000/1/0/356/. Accessed 18 September 2019.

- Staudt M (2018) Serie: Stadtteile in Flensburg. Flensburger Tageblatt.

- Sterr H (2008) Assessment of Vulnerability and Adaptation to Sea-Level Rise for the Coastal Zone of Germany. Journal of Coastal Research 242:380–393. [CrossRef]

- Swart, R.J., Raskin, P. and Robinson, J. (2004). The problem of the future: sustainability science and scenario analysis. Global environmental change, 14(2), pp.137-146. [CrossRef]

- Swedish Geotechnical Institute (2018) Living Lab Co-Design Requirements Guiding Paper: EVOKED Deliverable 1.1.

- The BACC II Author Team (2015) Second Assessment of Climate Change for the Baltic Sea Basin. Springer International Publishing, Cham.

- Tiwari A, Rodrigues LC, Lucy FE, Gharbia S (2022) Building Climate Resilience in Coastal City Living Labs Using Ecosystem-Based Adaptation: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 14(17):10863. [CrossRef]

- van den Eertwegh G, Bartholomeus R, Louw P de, Witte F, van Dam J, van Deijl D, Hoefsloot P, Clevers S, Hendriks D, van Huijgevoort M, Hunink J, Mulder N, Pouwels J, Wit J de (2019) Droogte in zandgebieden van Zuid-, Midden- en Oost-Nederland: Rapportage Fase 1: ontwikkeling van uniforme werkwijze voor analyse van droogte en tussentijdse bevindingen.

- van der Heijden K (2009) Scenarios: The art of strategic conversation, 2nd edn. Wiley, Chichester.

- van Ruijven BJ, Levy MA, Agrawal A, Biermann F, Birkmann J, Carter TR, Ebi KL, Garschagen M, Jones B, Jones R, Kemp-Benedict E, Kok M, Kok K, Lemos MC, Lucas PL, Orlove B, Pachauri S, Parris TM, Patwardhan A, Petersen A, Preston BL, Ribot J, Rothman DS, Schweizer VJ (2014) Enhancing the relevance of Shared Socioeconomic Pathways for climate change impacts, adaptation and vulnerability research. Climatic Change 122(3):481–494. [CrossRef]

- van Vuuren DP, Smith SJ, Riahi K (2010) Downscaling socioeconomic and emissions scenarios for global environmental change research: A review. WIREs Clim Change 1(3):393–404. [CrossRef]

- Voros J (2003) A generic foresight process framework. Foresight 5(3):10–21.

- Walker W, Haasnoot M, Kwakkel J (2013) Adapt or Perish: A Review of Planning Approaches for Adaptation under Deep Uncertainty. Sustainability 5(3):955–979. [CrossRef]

- Weiße R, Meinke I (2017) Meeresspiegelanstieg, Gezeiten, Sturmfluten und Seegang. In: Brasseur GP, Jacob D, Schuck-Zöller S (eds) Klimawandel in Deutschland: Entwicklung, Folgen, Risiken und Perspektiven. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 77–85.

- Werkregio Fluvius (2022) Samen werken aan klimaatbestendigheid – Regionale Adaptatiestrategie en Uitvoeringsagenda – 2022-2027. https://simcms.wdodelta.nl/_flysystem/media/ras-en-rua-samenwerkingsregio-fluvius_definitief.pdf. Accessed 10 February 2023.

- Wolters HA, van den Born, G.J., Dammers E, Reinhard S (2018) Deltascenario’s voor de 21e eeuw: actualisering 2017. Hoofdrapport, Utrecht.

- Zandersen M, Hyytiäinen K, Meier HEM, Tomczak MT, Bauer B, Haapasaari PE, Olesen JE, Gustafsson BG, Refsgaard JC, Fridell E, Pihlainen S, Le Tissier, Martin D. A., Kosenius A-K, van Vuuren DP (2019) Shared socio-economic pathways extended for the Baltic Sea: Exploring long-term environmental problems. Reg Environ Change 19(4):1073–1086. [CrossRef]

- Zurek MB, Henrichs T (2007) Linking scenarios across geographical scales in international environmental assessments. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 74(8):1282–1295. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).