Submitted:

21 November 2025

Posted:

25 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Differences Between p and pp Interactions

3. Kinematics

4. Cross Sections

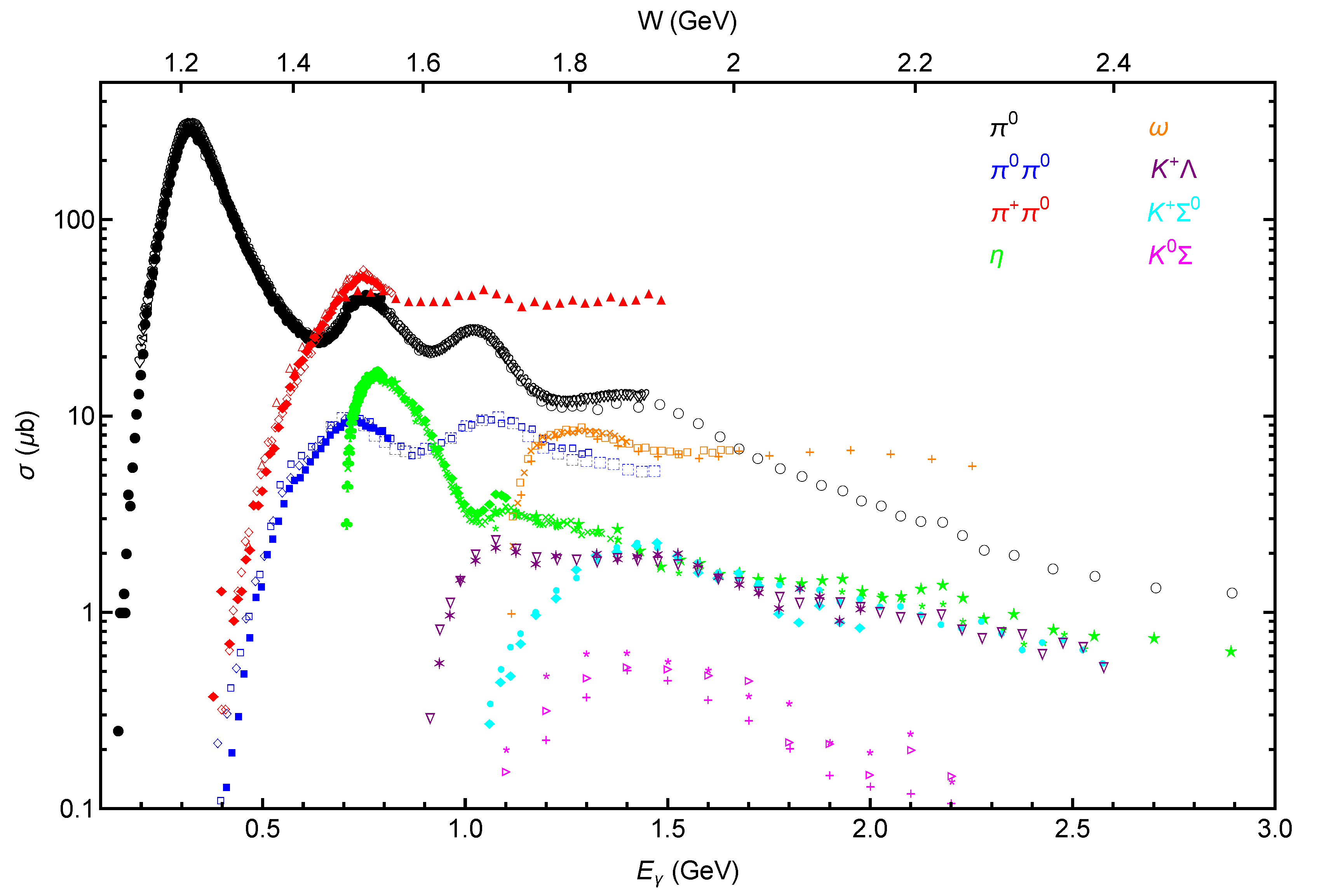

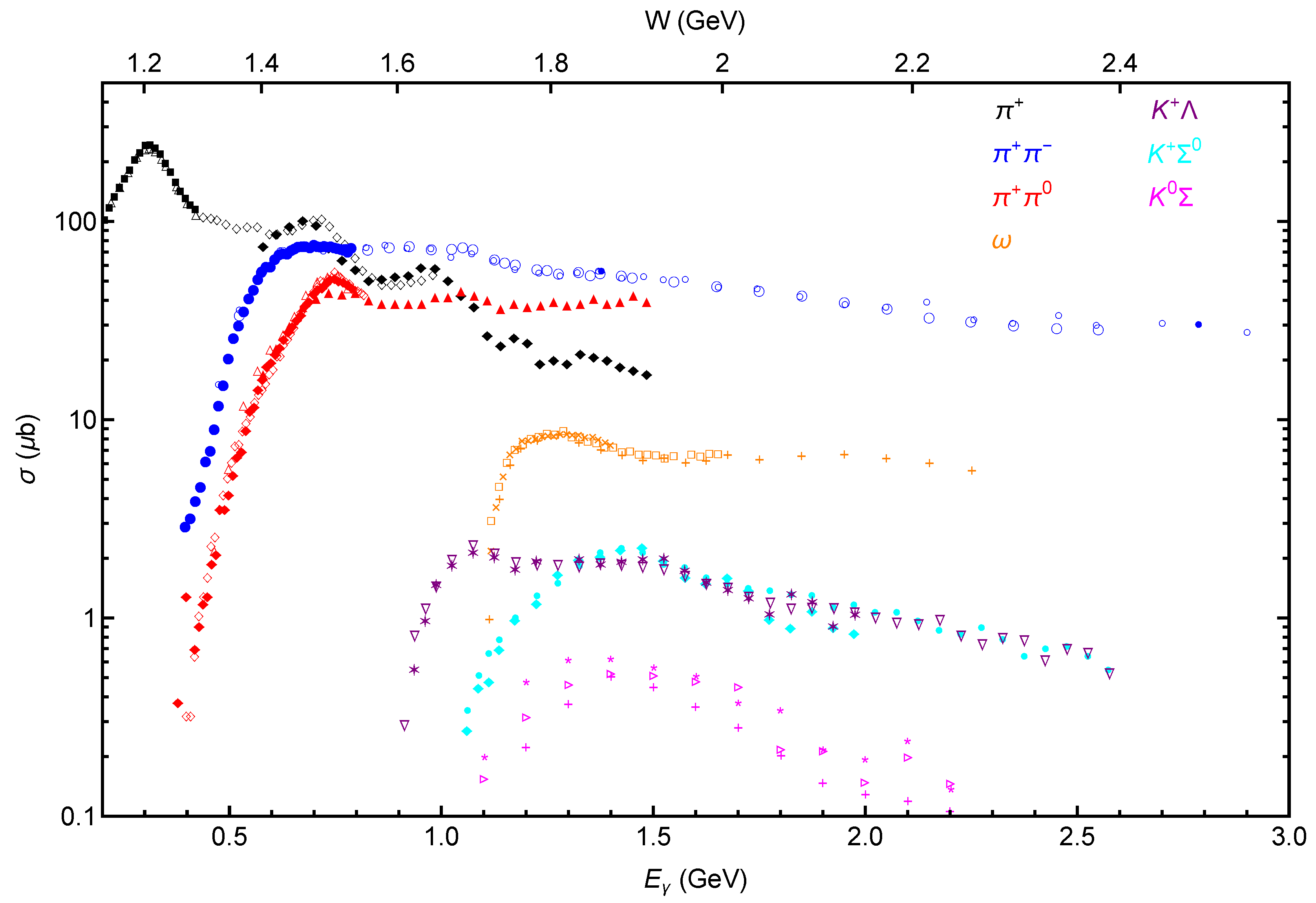

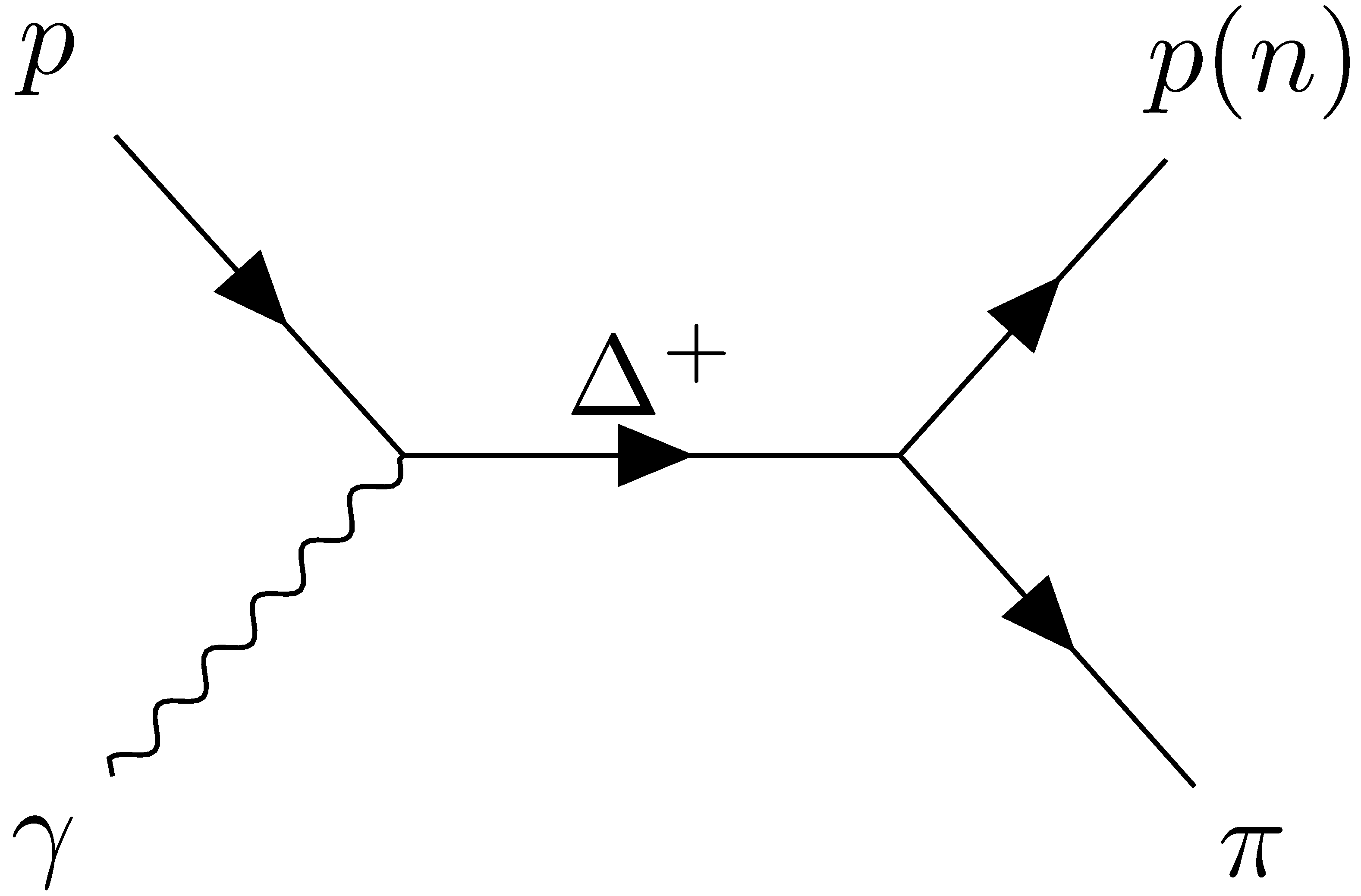

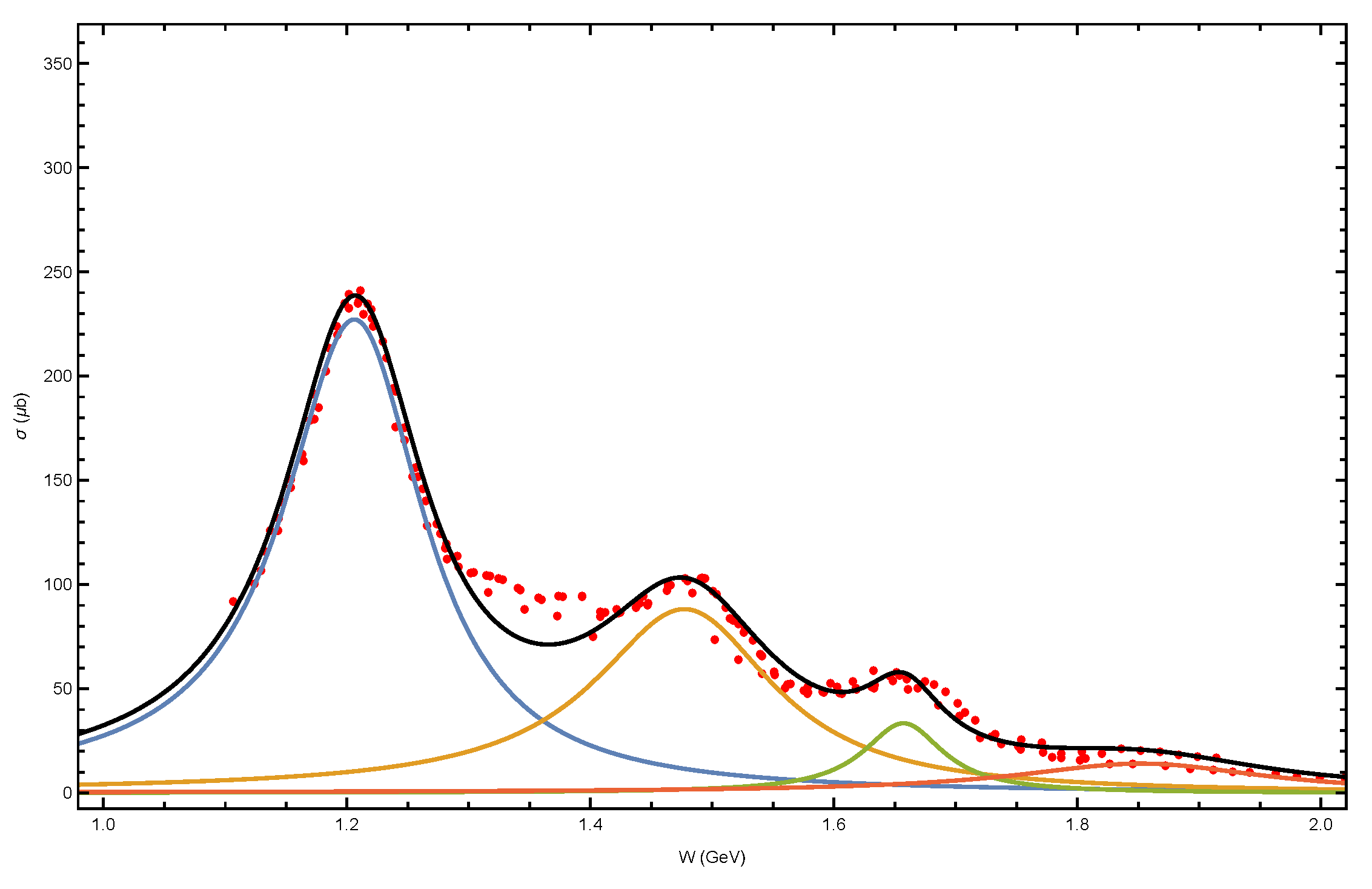

4.1. Single Pion Production

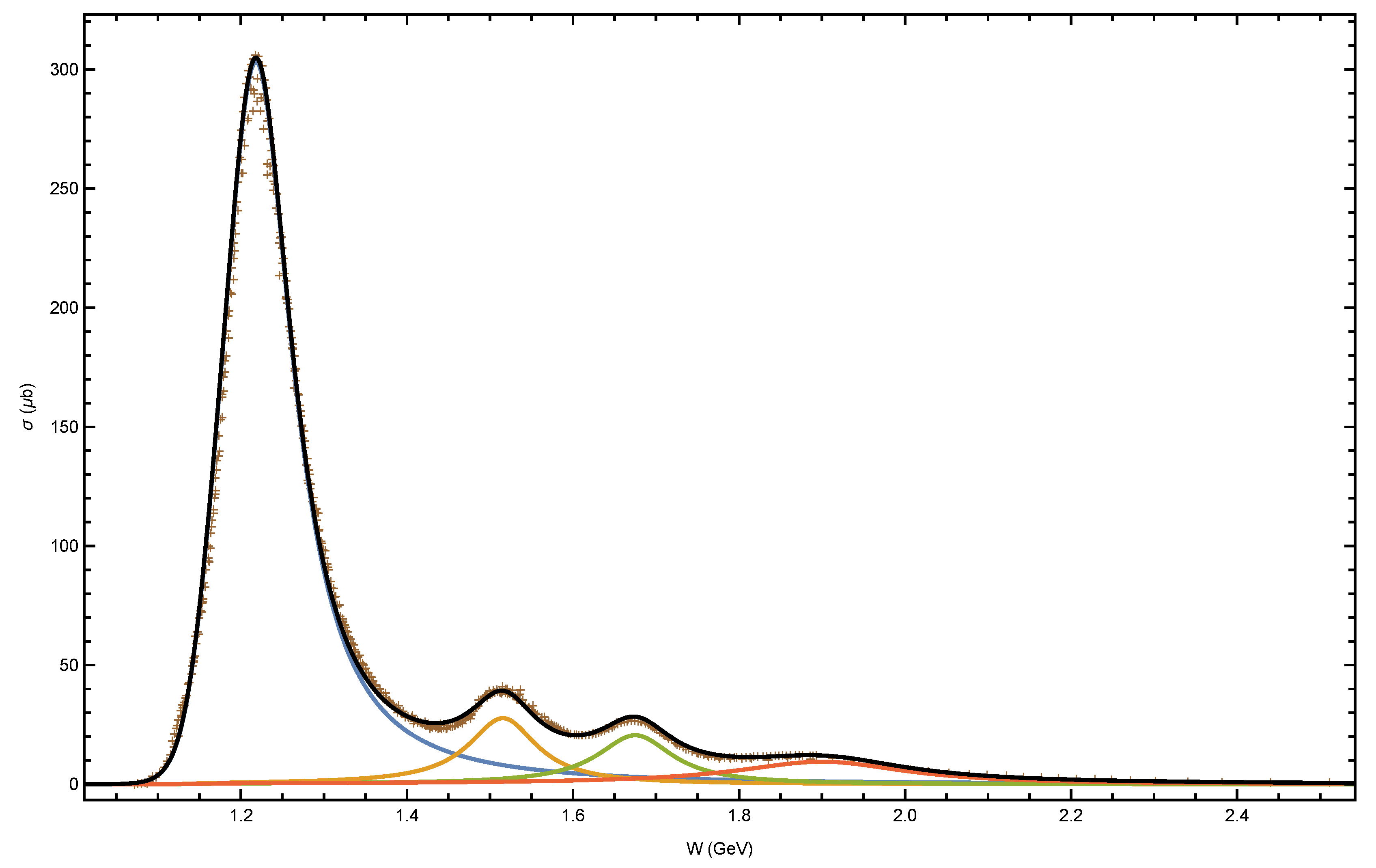

4.2. Single Pion Production

| peak | ) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 1.217 | 52.9 | 0.110 |

| 2nd | 1.516 | 4.35 | 0.100 |

| 3rd | 1.675 | 3.55 | 0.110 |

| 4th | 1.900 | 3.70 | 0.250 |

| peak | ) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 1.206 | 49.7 | 0.140 |

| 2nd | 1.477 | 24.8 | 0.180 |

| 3rd | 1.655 | 4.80 | 0.090 |

| 4th | 1.852 | 5.00 | 0.250 |

4.3. Two Pion Production

4.4. Three Pion and Gamma-Ray Line Production

5. Application for Highly Relativistic Protons in Astrophysical Sources

6. Heavier Nuclei

7. Discussion of Results

- By use of this collection of empirical cross section data one can determine the relative role of particle production channels in interactions leading to neutrino and -ray production in various astrophysical contexts. By compiling the cross sections for all of the channels that result in the production of -rays and neutrinos as a result of interactions, we have determined that only the single pion resonance channels are significant for astrophysical considerations. We have fitted the nucleon resonance data with a series of three-parameter Breit-Wigner type functions.The cross section data compiled here show that, contrary to the assertion of the SOPHIA collaboration [64], multiparticle production channels are not significant in producing -rays in interactions.

- We further find that two and three pion production is actually only the result of decay chains following from single particle photoproduction. There is no monotonic increase in multiplicity with energy as in the case of interctions. This is especially important when one takes account of the steep proton spectra, e.g., or steeper, expected for astrophysical sources of high energy protons.

- As shown in our Figure 4 and 5, there are significant differences between the production of charged and neutral pions (see point 5). This leads to significant differences between -ray and neutrino production that are not accounted for in SOPHIA-based models.

- As opposed to the case of pp interactions, and some speculation about interactions, owing to the small production cross sections and high threshold energy for kaons (see Section 3.) K production is negligible compared with pion production. This is abundantly clear from the data shown in Figs 1 and 2.

- As expected, among the single pion production channels, the channel dominates, even among the higher resonance channels. However, in the case of charged pion decay we find that the second resonance peak, made up of a blend on resonances, can give an additional contribution of as much as 20% to the resulting production of neutrinos. On the contrary, we find that the second resonance makes a negligible contribution to neutral pion production and subsequently to -ray production.

- For the first time, we have considered photoproduction of particles off heavier nuclei. As expected, only helium is important for astrophysical sources, given the relative cosmological abundances of the heavier elements. For helium, as for hydrogen, photoproduction is important only the region dominated by the Delta(1232) resonance. We find that the -ray and neutrino fluxes resulting from interactions is ∼10% of that from interactions.

- The use of a delta function approximation to simulate the production of -ray and neutrinos [4,5,14] is quite adequate for most calculations, given the present state of -ray and neutrino astronomy. However, a detailed knowledge the physics of photopion production may be more importance in the future as given advances in observational instrumentation and source modeling.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A Particle Spectra

Appendix A.1. Gamma-Ray Spectra

Appendix B Neutrino spectra

References

- K. Greisen, End to the Cosmic-Ray Spectrum?, Physical Review Letters 16 (17) (1966) 748–750. [CrossRef]

- G. T. Zatsepin, V. A. Kuz’min, Upper Limit of the Spectrum of Cosmic Rays, Soviet Journal of Experimental and Theoretical Physics Letters 4 (1966) 78.

- F. W. Stecker, Effect of photomeson production by the universal radiation field on high-energy cosmic rays, Phys. Rev. Lett. 21 (1968) 1016–1018.

- F. W. Stecker, Ultrahigh energy photons, electrons, and neutrinos, the microwave background, and the universal cosmic-ray hypothesis, Astrophysics and Space Science 20 (1) (1973) 47–57. [CrossRef]

- F. W. Stecker, Diffuse fluxes of cosmic high-energy neutrinos., The Astrophysical Journal 228 (1979) 919–927. [CrossRef]

- S. R. Kelner, F. A. Aharonian, Energy spectra of gamma rays, electrons, and neutrinos produced at interactions of relativistic protons with low energy radiation, Physical Review D 78 (3) (2008) 034013. [CrossRef]

- S. Hümmer, M. Rüger, F. Spanier, W. Winter, SIMPLIFIED MODELS FOR PHOTOHADRONIC INTERACTIONS IN COSMIC ACCELERATORS, The Astrophysical Journal 721 (1) (2010) 630. [CrossRef]

- F. W. Stecker (Ed.), The Encyclopedia of Cosmology: Volume 2: Neutrino Physics and Astrophysics, World Scientific, 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. W. Stecker, Chapter 1: Neutrino Physics and Astrophysics Overview (2023) 1–8http://arxiv.org/abs/2301.02935 arXiv:2301.02935. [CrossRef]

- F. W. Stecker, C. Done, M. H. Salamon, P. Sommers, High-energy neutrinos from active galactic nuclei, Physical Review Letters 66 (21) (1991) 2697–2700. [CrossRef]

- K. Murase, F. W. Stecker, Chapter 10: High-Energy Neutrinos from Active Galactic Nuclei, World Scientific Press, 2023, pp. 483–540. [CrossRef]

- V. S. Berezinsky, G. T. Zatsepin, Cosmic rays at ultrahigh-energies (neutrino?), Phys. Lett. B 28 (1969) 423–424. [CrossRef]

- IceCube Collaboration, First Observation of PeV-Energy Neutrinos with IceCube, Physical Review Letters 111 (2) (2013) 021103. [CrossRef]

- F. Halzen, A. Kheirandish, Chapter 5: IceCube and High-Energy Cosmic Neutrinos, World Scientific Press, 2023, pp. 107–235. http://arxiv.org/abs/2202.00694. [CrossRef]

- IceCube Collaboration, Neutrino emission from the direction of the blazar TXS 0506+056 prior to the IceCube-170922A alert, Science 361 (6398) (2018) 147–151. [CrossRef]

- IceCube Collaboration, Evidence for neutrino emission from the nearby active galaxy NGC 1068, Science (Nov. 2022). [CrossRef]

- F. W. Stecker, PeV neutrinos observed by IceCube from cores of active galactic nuclei, Physical Review D 88 (4) (2013) 047301. [CrossRef]

- K. Murase, D. Guetta, M. Ahlers, Hidden Cosmic-Ray Accelerators as an Origin of TeV-PeV Cosmic Neutrinos, Physical Review Letters 116 (7) (2016) 071101. [CrossRef]

- A. e. a. Mueecke, Monte Carlo Simulations of Phothadronic Processes and their Astrophysical Implications, Comp.Phys.Comm. 124 (2000) 290–314.

- G. F. Chew, F. E. Low, Theory of Photomeson Production at Low Energies, Phys. Rev. 101 (1956) 1579–1587. [CrossRef]

- G. F. Chew, M. L. Goldberger, F. E. Low, Y. Nambu, Relativistic dispersion relation approach to photomeson production, Phys. Rev. 106 (1957) 1345–1355. [CrossRef]

- D. Drechsel, L. Tiator, Threshold pion photoproduction on nucleons, J. Phys. G 18 (1992) 449–497. [CrossRef]

- K. Geiger, Particle production in high-energy nuclear collisions: A Parton cascade cluster hadronization model, Phys. Rev. D 47 (1993) 133–159. [CrossRef]

- S. Gevorkyan, Hadronic properties of the photon, EPJ Web Conf. 204 (2019) 05012. 05012. [CrossRef]

- H. Genzel, P. Joos, W. Pfeil, Photoproduction of Elementary Particles / Photoproduktion von Elementarteilchen, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1973.

- F. Härter, J. Ahrens, R. Beck, B. Krusche, V. Metag, M. Schmitz, H. Ströher, Th. Walcher, M. Wolf, Two neutral pion photoproduction off the proton between threshold and 800 MeV, Physics Letters B 401 (3) (1997) 229–233. [CrossRef]

- CB-ELSA Collaboration, O. Bartholomy, V. Credé, H. van Pee, A. V. Anisovich, G. Anton, R. Bantes, Yu. Beloglazov, R. Bogendörfer, R. Castelijns, A. Ehmanns, J. Ernst, I. Fabry, H. Flemming, A. Fösel, H. Freiesleben, M. Fuchs, Ch. Funke, R. Gothe, A. Gridnev, E. Gutz, S. K. Höffgen, I. Horn, J. Hößl, R. Joosten, J. Junkersfeld, H. Kalinowsky, F. Klein, E. Klempt, H. Koch, M. Konrad, B. Kopf, B. Krusche, J. Langheinrich, H. Löhner, I. Lopatin, J. Lotz, H. Matthäy, D. Menze, J. Messchendorp, C. Morales, D. Novinski, M. Ostrick, A. Radkov, J. Reinnarth, A. V. Sarantsev, S. Schadmand, Ch. Schmidt, H. Schmieden, B. Schoch, G. Suft, V. Sumachev, T. Szczepanek, U. Thoma, D. Walther, Ch. Weinheimer, Neutral Pion Photoproduction off Protons in the Energy Range 0.3. [CrossRef]

- S. Schumann, B. Boillat, E. J. Downie, P. Aguar-Bartolomé, J. Ahrens, J. R. M. Annand, H. J. Arends, R. Beck, V. Bekrenev, A. Braghieri, D. Branford, W. J. Briscoe, J. W. Brudvik, S. Cherepnya, R. Codling, P. Drexler, L. V. Fil’kov, D. I. Glazier, R. Gregor, E. Heid, D. Hornidge, O. Jahn, V. L. Kashevarov, R. Kondratiev, M. Korolija, M. Kotulla, D. Krambrich, B. Krusche, M. Lang, V. Lisin, K. Livingston, S. Lugert, I. J. D. MacGregor, D. M. Manley, M. Martinez-Fabregate, J. C. McGeorge, D. Mekterovic, V. Metag, B. M. K. Nefkens, A. Nikolaev, R. Novotny, M. Ostrick, R. O. Owens, P. Pedroni, A. Polonski, S. N. Prakhov, J. W. Price, G. Rosner, M. Rost, T. Rostomyan, D. Sober, A. Starostin, I. Supek, C. M. Tarbert, A. Thomas, M. Unverzagt, Th. Walcher, D. P. Watts, F. Zehr, T. a. A. C. The Crystal Ball at MAMI, Radiative Π0 photoproduction on protons in the Δ+ (1232) region, The European Physical Journal A 43 (3) (2010) 269–282. [CrossRef]

- A2 Collaboration at MAMI, P. Adlarson, F. Afzal, C. S. Akondi, J. R. M. Annand, H. J. Arends, Ya. I. Azimov, R. Beck, N. Borisov, A. Braghieri, W. J. Briscoe, S. Cherepnya, F. Cividini, C. Collicott, S. Costanza, A. Denig, E. J. Downie, M. Dieterle, M. I. Ferretti Bondy, L. V. Fil’kov, A. Fix, S. Gardner, S. Garni, D. I. Glazier, D. Glowa, W. Gradl, G. Gurevich, D. J. Hamilton, D. Hornidge, G. M. Huber, A. Käser, V. L. Kashevarov, S. Kay, I. Keshelashvili, R. Kondratiev, M. Korolija, B. Krusche, V. V. Kulikov, A. Lazarev, J. Linturi, V. Lisin, K. Livingston, I. J. D. MacGregor, D. M. Manley, P. P. Martel, M. Martemianov, J. C. McGeorge, W. Meyer, D. G. Middleton, R. Miskimen, A. Mushkarenkov, A. Neganov, A. Neiser, M. Oberle, M. Ostrick, P. Ott, P. B. Otte, B. Oussena, D. Paudyal, P. Pedroni, A. Polonski, V. V. Polyanski, S. Prakhov, A. Rajabi, G. Reicherz, G. Ron, T. Rostomyan, A. Sarty, D. M. Schott, S. Schumann, C. Sfienti, V. Sokhoyan, K. Spieker, O. Steffen, I. I. Strakovsky, Th. Strub, I. Supek, M. F. Taragin, A. Thiel, M. Thiel, L. Tiator, A. Thomas, M. Unverzagt, Yu. A. Usov, S. Wagner, D. P. Watts, D. Werthmüller, J. Wettig, L. Witthauer, M. Wolfes, R. L. Workman, L. A. Zana, Measurement of ${\ensuremath{\pi}}⌃{0}$ photoproduction on the proton at MAMI C, Physical Review C 92 (2) (2015) 024617. [CrossRef]

- A. Braghieri, L. Y. Murphy, J. Ahrens, G. Audit, N. d’Hose, V. Isbert, S. Kerhoas, M. Mac Cormick, P. Pedroni, T. Pinelli, G. Tamas, A. Zabrodin, Total cross section measurement for the three double pion photoproduction channels on the proton, Physics Letters B 363 (1) (1995) 46–50. [CrossRef]

- W. Langgärtner, J. Ahrens, R. Beck, V. Hejny, M. Kotulla, B. Krusche, V. Kuhr, R. Leukel, J. D. McGregor, J. G. Messchendorp, V. Metag, R. Novotny, V. Olmos de Léon, R. O. Owens, F. Rambo, S. Schadmand, A. Schmidt, U. Siodlaczek, H. Ströher, J. Weiß, F. Wissmann, M. Wolf, Physical Review Letters 87 (5) (2001) 052001. [CrossRef]

- J. Ahrens, The Total Absorption of Photons by Nuclei, Nucl. Phys. A 446 (1985) 229C–239C. [CrossRef]

- O. Bartalini, V. Bellini, J. P. Bocquet, P. Calvat, A. D’Angelo, J. P. Didelez, R. Di Salvo, A. Fantini, F. Ghio, B. Girolami, M. Guidal, A. Giusa, E. Hourany, A. S. Ignatov, R. Kunne, A. M. Lapik, P. L. Sandri, A. Lleres, D. Moricciani, A. N. Mushkarenkov, V. G. Nedorezov, C. Perrin, D. Rebreyend, F. Renard, N. V. Rudnev, T. Russew, G. Russo, C. Schaerf, M. L. Sperduto, M. C. Sutera, A. A. Turinge, Measurement of the total photoabsorption cross section on a proton in the energy range 600–1500 MeV at the GRAAL, Physics of Atomic Nuclei 71 (1) (2008) 75–82. [CrossRef]

- F. Zehr, B. Krusche, P. Aguar, J. Ahrens, J. R. M. Annand, H. J. Arends, R. Beck, V. Bekrenev, B. Boillat, A. Braghieri, D. Branford, W. J. Briscoe, J. Brudvik, S. Cherepnya, R. F. B. Codling, E. J. Downie, P. Drexler, D. I. Glazier, L. V. Fil’kov, A. Fix, R. Gregor, E. Heid, D. Hornidge, I. Jaegle, O. Jahn, V. L. Kashevarov, A. Knezevic, R. Kondratiev, M. Korolija, M. Kotulla, D. Krambrich, A. Kulbardis, M. Lang, V. Lisin, K. Livingston, S. Lugert, I. J. D. MacGregor, D. M. Manley, Y. Maghrbi, M. Martinez, J. C. McGeorge, D. Mekterovic, V. Metag, B. M. K. Nefkens, A. Nikolaev, M. Ostrick, P. Pedroni, F. Pheron, A. Polonski, S. Prakhov, J. W. Price, G. Rosner, M. Rost, T. Rostomyan, S. Schumann, D. Sober, A. Starostin, I. Supek, C. M. Tarbert, A. Thomas, M. Unverzagt, Th. Walcher, D. P. Watts, Photoproduction of Π0π0 - and Π0π+ -pairs off the proton from threshold to the second resonance region, The European Physical Journal A 48 (7) (2012) 98. [CrossRef]

- Y. Assafiri, O. Bartalini, V. Bellini, J. P. Bocquet, S. Bouchigny, M. Capogni, M. Castoldi, A. D’Angelo, J. P. Didelez, R. Di Salvo, A. Fantini, L. Fichen, G. Gervino, F. Ghio, B. Girolami, A. Giusa, M. Guidal, E. Hourany, V. Kouznetsov, R. Kunne, J.-M. Laget, A. Lapik, P. L. Sandri, A. Lleres, D. Moricciani, V. Nedorezov, D. Rebreyend, C. Randieri, F. Renard, N. Rudnev, C. Schaerf, M. Sperduto, M. Sutera, A. Turinge, A. Zucchiatti, Double ${\ensuremath{\pi}}⌃{0}$ Photoproduction on the Proton at GRAAL, Physical Review Letters 90 (22) (2003) 222001. [CrossRef]

- U. Thoma, et al., N* and Delta* decays into N pi0 pi0, Phys. Lett. B 659 (2008) 87–93. http://arxiv.org/abs/0707.3592 arXiv:0707.3592. [CrossRef]

- A. V. Sarantsev, M. Fuchs, M. Kotulla, U. Thoma, J. Ahrens, J. R. M. Annand, A. V. Anisovich, G. Anton, R. Bantes, O. Bartholomy, R. Beck, Yu. Beloglazov, R. Castelijns, V. Crede, A. Ehmanns, J. Ernst, I. Fabry, H. Flemming, A. Fösel, Chr. Funke, R. Gothe, A. Gridnev, E. Gutz, St. Höffgen, I. Horn, J. Hößl, D. Hornidge, S. Janssen, J. Junkersfeld, H. Kalinowsky, F. Klein, E. Klempt, H. Koch, M. Konrad, B. Kopf, B. Krusche, J. Langheinrich, H. Löhner, I. Lopatin, J. Lotz, J. C. McGeorge, I. J. D. MacGregor, H. Matthäy, D. Menze, J. G. Messchendorp, V. Metag, V. A. Nikonov, D. Novinski, R. Novotny, M. Ostrick, H. van Pee, M. Pfeiffer, A. Radkov, G. Rosner, M. Rost, C. Schmidt, B. Schoch, G. Suft, V. Sumachev, T. Szczepanek, D. Walther, D. P. Watts, Chr. Weinheimer, New results on the roper resonance and the p11 partial wave, Physics Letters B 659 (1) (2008) 94–100. [CrossRef]

- J. Barth, W. Braun, J. Ernst, K.-H. Glander, J. Hannappel, N. Jöpen, H. Kalinowsky, F. J. Klein, F. Klein, E. Klempt, R. Lawall, J. Link, D. Menze, W. Neuerburg, M. Ostrick, E. Paul, H. van Pee, I. Schulday, W. J. Schwille, B. Wiegers, F. W. Wieland, J. Wißkirchen, C. Wu, Low-energy photoproduction of ω-mesons, The European Physical Journal A - Hadrons and Nuclei 18 (1) (2003) 117–127. [CrossRef]

- CLAS Collaboration, M. Williams, D. Applegate, M. Bellis, C. A. Meyer, K. P. Adhikari, M. Anghinolfi, H. Baghdasaryan, J. Ball, M. Battaglieri, I. Bedlinskiy, B. L. Berman, A. S. Biselli, W. J. Briscoe, W. K. Brooks, V. D. Burkert, S. L. Careccia, D. S. Carman, P. L. Cole, P. Collins, V. Crede, A. D’Angelo, A. Daniel, R. De Vita, E. De Sanctis, A. Deur, B. Dey, S. Dhamija, R. Dickson, C. Djalali, G. E. Dodge, D. Doughty, M. Dugger, R. Dupre, A. E. Alaoui, L. Elouadrhiri, P. Eugenio, G. Fedotov, S. Fegan, A. Fradi, M. Y. Gabrielyan, M. Garçon, G. P. Gilfoyle, K. L. Giovanetti, F. X. Girod, W. Gohn, E. Golovatch, R. W. Gothe, K. A. Griffioen, M. Guidal, N. Guler, L. Guo, K. Hafidi, H. Hakobyan, C. Hanretty, N. Hassall, K. Hicks, M. Holtrop, Y. Ilieva, D. G. Ireland, B. S. Ishkhanov, E. L. Isupov, S. S. Jawalkar, H. S. Jo, J. R. Johnstone, K. Joo, D. Keller, M. Khandaker, P. Khetarpal, W. Kim, A. Klein, F. J. Klein, Z. Krahn, V. Kubarovsky, S. V. Kuleshov, V. Kuznetsov, K. Livingston, H. Y. Lu, M. Mayer, J. McAndrew, M. E. McCracken, B. McKinnon, M. Mirazita, V. Mokeev, B. Moreno, K. Moriya, B. Morrison, E. Munevar, P. Nadel-Turonski, C. S. Nepali, S. Niccolai, G. Niculescu, I. Niculescu, M. R. Niroula, R. A. Niyazov, M. Osipenko, A. I. Ostrovidov, M. Paris, K. Park, S. Park, E. Pasyuk, S. A. Pereira, Y. Perrin, S. Pisano, O. Pogorelko, S. Pozdniakov, J. W. Price, S. Procureur, D. Protopopescu, G. Ricco, M. Ripani, B. G. Ritchie, G. Rosner, P. Rossi, F. Sabatié, M. S. Saini, J. Salamanca, C. Salgado, D. Schott, R. A. Schumacher, H. Seraydaryan, Y. G. Sharabian, E. S. Smith, D. I. Sober, D. Sokhan, S. S. Stepanyan, P. Stoler, I. I. Strakovsky, S. Strauch, M. Taiuti, D. J. Tedeschi, S. Tkachenko, M. Ungaro, M. F. Vineyard, E. Voutier, D. P. Watts, D. P. Weygand, M. H. Wood, J. Zhang, B. Zhao, Partial wave analysis of the reaction γp→pω and the search for nucleon resonances, Physical Review C 80 (6) (2009) 065209. [CrossRef]

- A2 Collaboration at MAMI, I. I. Strakovsky, S. Prakhov, Ya. I. Azimov, P. Aguar-Bartolomé, J. R. M. Annand, H. J. Arends, K. Bantawa, R. Beck, V. Bekrenev, H. Berghäuser, A. Braghieri, W. J. Briscoe, J. Brudvik, S. Cherepnya, R. F. B. Codling, C. Collicott, S. Costanza, B. T. Demissie, E. J. Downie, P. Drexler, L. V. Fil’kov, D. I. Glazier, R. Gregor, D. J. Hamilton, E. Heid, D. Hornidge, I. Jaegle, O. Jahn, T. C. Jude, V. L. Kashevarov, I. Keshelashvili, R. Kondratiev, M. Korolija, M. Kotulla, A. Koulbardis, S. Kruglov, B. Krusche, V. Lisin, K. Livingston, I. J. D. MacGregor, Y. Maghrbi, D. M. Manley, Z. Marinides, J. C. McGeorge, E. F. McNicoll, D. Mekterovic, V. Metag, D. G. Middleton, A. Mushkarenkov, B. M. K. Nefkens, A. Nikolaev, R. Novotny, H. Ortega, M. Ostrick, P. B. Otte, B. Oussena, P. Pedroni, F. Pheron, A. Polonski, J. Robinson, G. Rosner, T. Rostomyan, S. Schumann, M. H. Sikora, A. Starostin, I. Supek, M. F. Taragin, C. M. Tarbert, M. Thiel, A. Thomas, M. Unverzagt, D. P. Watts, D. Werthmüller, F. Zehr, Photoproduction of the $\ensuremath{\omega}$ meson on the proton near threshold, Physical Review C 91 (4) (2015) 045207. [CrossRef]

- B. Krusche, J. Ahrens, G. Anton, R. Beck, M. Fuchs, A. R. Gabler, F. Härter, S. Hall, P. Harty, S. Hlavac, D. MacGregor, C. McGeorge, V. Metag, R. Owens, J. Peise, M. Röbig-Landau, A. Schubert, R. S. Simon, H. Ströher, V. Tries, Near Threshold Photoproduction of $\mathit{\ensuremath{\eta}}$ Mesons off the Proton, Physical Review Letters 74 (19) (1995) 3736–3739. [CrossRef]

- F. Renard, M. Anghinolfi, O. Bartalini, V. Bellini, J. P. Bocquet, M. Capogni, M. Castoldi, P. Corvisiero, A. D’Angelo, J. P. Didelez, R. Di Salvo, C. Gaulard, G. Gervino, F. Ghio, B. Girolami, M. Guidal, E. Hourany, V. Kouznetsov, R. Kunne, A. Lapik, P. Levi Sandri, A. Lleres, D. Morriciani, V. Nedorezov, L. Nicoletti, D. Rebreyend, N. Rudnev, M. Sanzone, C. Schaerf, M. L. Sperduto, M. C. Sutera, M. Taiuti, A. Turinge, Q. Zhao, A. Zucchiatti, Differential cross section measurement of η photoproduction on the proton from threshold to 1100 MeV, Physics Letters B 528 (3) (2002) 215–220. [CrossRef]

- M. Q. Tran, J. Barth, C. Bennhold, M. Bockhorst, W. Braun, A. Budzanowski, G. Burbach, R. Burgwinkel, J. Ernst, K. H. Glander, S. Goers, B. Guse, K. M. Haas, J. Hannappel, K. Heinloth, K. Honscheid, T. Jahnen, N. Jöpen, H. Jüngst, H. Kalinowsky, U. Kirch, F. J. Klein, F. Klein, E. Klempt, D. Kostrewa, A. Kozela, R. Lawall, L. Lindemann, J. Link, J. Manns, T. Mart, D. Menze, H. Merkel, R. Merkel, W. Neuerburg, M. Paganetti, E. Paul, R. Plötzke, U. Schenk, J. Scholmann, I. Schulday, M. Schumacher, P. Schütz, W. J. Schwille, F. Smend, J. Smyrski, W. Speth, H. N. Tran, H. van Pee, W. Vogl, R. Wedemeyer, F. Wehnes, B. Wiegers, F. W. Wieland, J. Wißkirchen, A. Wolf, Measurement of γp→K+Λ and γp→K+Σ0 at photon energies up to 2 GeV 1, Physics Letters B 445 (1) (1998) 20–26. [CrossRef]

- K.-H. Glander, J. Barth, W. Braun, J. Hannappel, N. Jöpen, F. Klein, E. Klempt, R. Lawall, J. Link, D. Menze, W. Neuerburg, M. Ostrick, E. Paul, I. Schulday, W. J. Schwille, H. v. Pee, F. W. Wieland, J. Wißkirchen, C. Wu, Measurement of $\gamma p \rightarrow K \Lambda$and $\gamma p \rightarrow K \Sigma$at photon energies up to 2.6 GeV, The European Physical Journal A - Hadrons and Nuclei 19 (2) (2004) 251–273. [CrossRef]

- F. J. Klein, Photoproduction of K0 Sigma+ with CLAS, Nucl. Phys. A 754 (2005) 321–326. [CrossRef]

- . Lawall, J. Barth, C. Bennhold, K. H. Glander, S. Goers, J. Hannappel, N. Jöpen, F. Klein, E. Klempt, T. Mart, D. Menze, M. Ostrick, E. Paul, I. Schulday, W. J. Schwille, F. W. Wieland, C. Wu, Measurement of the reaction Γp → K0Σat photon energies up to 2.6 GeV★, The European Physical Journal A - Hadrons and Nuclei 24 (2) (2005) 275–285. [CrossRef]

- R. Castelijns, A. V. Anisovich, J. C. S. Bacelar, B. Bantes, O. Bartholomy, D. Bayadilov, Y. A. Beloglazov, V. Crede, H. Dutz, A. Ehmanns, D. Elsner, K. Essig, R. Ewald, I. Fabry, K. Fornet-Ponse, M. Fuchs, C. Funke, R. Gothe, R. Gregor, A. B. Gridnev, E. Gutz, S. Höffgen, P. Hoffmeister, I. Horn, I. Jaegle, J. Junkersfeld, H. Kalinowsky, S. Kammer, F. Klein, F. Klein, E. Klempt, M. Konrad, M. Kotulla, B. Krusche, J. Langheinrich, H. Löhner, I. V. Lopatin, J. Lotz, S. Lugert, D. Menze, T. Mertens, J. G. Messchendorp, V. Metag, C. Morales, M. Nanova, V. A. Nikonov, D. Novinski, R. Novotny, M. Ostrick, L. M. Pant, H. van Pee, M. Pfeiffer, A. Roy, A. Radkov, A. V. Sarantsev, S. Schadmand, C. Schmidt, H. Schmieden, B. Schoch, S. Shende, A. Süle, V. V. Sumachev, T. Szczepanek, U. Thoma, D. Trnka, R. Varma, D. Walther, C. Weinheimer, C. Wendel, The CBELSA/TAPS Collaboration, Nucleon resonance decay by the K0Σchannel, The European Physical Journal A 35 (1) (2008) 39–45. [CrossRef]

- K. Büchler, K. H. Althoff, G. Anton, J. Arends, W. Beulertz, M. Breuer, P. Detemple, H. Dutz, E. Kohlgarth, D. Krämer, W. Meyer, G. Nöldeke, W. Schneider, W. Thiel, B. Zucht, Photoproduction of positive pions from hydrogen with PHOENICS at ELSA, Nuclear Physics A 570 (3) (1994) 580–598. [CrossRef]

- Total photoabsorption cross sections for H andHe from 200 to 800 MeV, author = MacCormick, M. and Audit, G. and d’Hose, N. and Ghedira, L. and Isbert, V. and Kerhoas, S. and Murphy, L. Y. and Tamas, G. and Wallace, P. A. and Altieri, S. and Braghieri, A. and Pedroni, P. and Pinelli, T. and Ahrens, J. and Beck, R. and Annand, J. R. M. and Crawford, R. A. and Kellie, J. D. and MacGregor, I. J. D. and Dolbilkin, B. and Zabrodin, A., year = 1996, month = jan, journal = Physical Review C, volume = 53, number = 1, pages = 41–49, publisher = American Physical Society, doi = 10.1103/PhysRevC.53.41, urldate = 2024-01-08, abstract = The total photoabsorption cross sections for 1H, 2H, and 3He have been measured for incident photon energies ranging from 200 to 800 MeV. The 3He data are the first for this nucleus. By using the large acceptance detector DAPHNE in conjunction with the tagged photon beam facility of the MAMI accelerator in Mainz, cross sections of high precision have been obtained. The results show clearly the changes in the nucleon resonances in going from 1H to 3He. In particular, for the D13 region the behavior for 3He is intermediate between that for 1H, 2H, and heavier nuclei. This will provide a strong constraint to the theories that are presently being developed with a view to explaining the apparent “damping” of higher resonances in heavy nuclei. © 1996 The American Physical Society., file = /Users/scullyst/Zotero/storage/SR88CNID/MacCormick et al. - 1996 - Total photoabsorption cross sections for 1mathrmH, 2mathrmH, and 3mathrmHe f.pdf;/Users/scullyst/Zotero/storage/YT472IPH/PhysRevC.53.html.

- Aachen-Berlin-Bonn-Hamburg-Heidelberg-München Collaboration, Photoproduction of Meson and Baryon Resonances at Energies up to 5.8 GeV, Physical Review 175 (5) (1968) 1669–1696. [CrossRef]

- J. Ballam, G. B. Chadwick, R. Gearhart, Z. G. T. Guiragossián, J. J. Murray, P. Seyboth, C. K. Sinclair, I. O. Skillicorn, H. Spitzer, G. Wolf, H. H. Bingham, W. B. Fretter, K. C. Moffeit, W. J. Podolsky, M. S. Rabin, A. H. Rosenfeld, R. Windmolders, R. H. Milburn, Bubble-Chamber Study of Photoproduction by 2.8- and 4.7-GeV Polarized Photons. I. Cross-Section Determinations and Production of ρ0 and Δ++ in the Reaction γp→pπ+π-, Physical Review D 5 (3) (1972) 545–589. [CrossRef]

- C. Wu, J. Barth, W. Braun, J. Ernst, K. H. Glander, J. Hannappel, N. Jöpen, H. Kalinowsky, F. J. Klein, F. Klein, E. Klempt, R. Lawall, J. Link, D. Menze, W. Neuerburg, M. Ostrick, E. Paul, H. van Pee, I. Schulday, W. J. Schwille, B. Wiegers, F. W. Wieland, J. Wißkirchen, Photoproduction of Pmesons and Δ-baryons in the reaction Γp → pπ+π- at energies up to $ \sqrt{{s}}$= 2.6 GeV, The European Physical Journal A - Hadrons and Nuclei 23 (2) (2005) 317–344. [CrossRef]

- F. W. Stecker, Cosmic Gamma Rays, U.S. Govt. Printing Office, NASA-SP249,19710015288.pdf, 1971.

- M. Gell-Mann, Isotopic Spin and New Unstable Particles, Phys. Rev. 92 (1953) 833–834. [CrossRef]

- T. Nakano, K. Nishijima, Charge Independence for V-particles, Prog. Theor. Phys. 10 (1953) 581–582. [CrossRef]

- R. R. Wilson, Possible New Isobaric State of the Proton, Phys. Rev. 110 (1958) 1212–1213. 1212–1213. [CrossRef]

- L. D. Roper, Evidence for a P-11 Pion-Nucleon Resonance at 556 MeV, Phys. Rev. Lett. 12 (1964) 340–342. [CrossRef]

- D. Lüke, P. Söding, Multiple pion photoproduction in the s channel resonance region, Springer Tracts Mod. Phys. 59 (1971) 39–76.

- M. Hirata, K. Ochi, T. Takaki, Effect of rho N channel in the gamma N —> pi pi N reactions (11 1997). http://arxiv.org/abs/nucl-th/9711031 arXiv:nucl-th/9711031.

- M. Hirata, N. Katagiri, K. Ochi, T. Takaki, Nuclear photoabsorption at photon energies between 300-MeV and 850-MeV, Phys. Rev. C 66 (2002) 014612. http://arxiv.org/abs/nucl-th/0112079. [CrossRef]

- M. MacCormick, J. Habermann, J. Ahrens, G. Audit, R. Beck, A. Braghieri, G. Galler, N. d’Hose, V. Isbert, P. Pedroni, T. Pinelli, G. Tamas, S. Wartenberg, A. Zabrodin, Total photoabsorption cross section for 4 He from 200 to 800 MeV, Physical Review C 55 (3) (1997) 1033–1038. [CrossRef]

- E. W. Kolb, M. S. Turner, The Early Universe, Vol. 69, Taylor and Francis, 2019. [CrossRef]

- W. Stecker, The Cosmic gamma-ray spectrum from secondary particle production in cosmic ray interactions, Astrophys. Space Sci. 6 (1970) 377–389. [CrossRef]

- A. Mücke, R. Engel, J. P. Rachen, R. J. Protheroe, T. Stanev, Monte Carlo simulations of photohadronic processes in astrophysics, Computer Physics Communications 124 (2) (2000) 290–314. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).