Submitted:

21 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

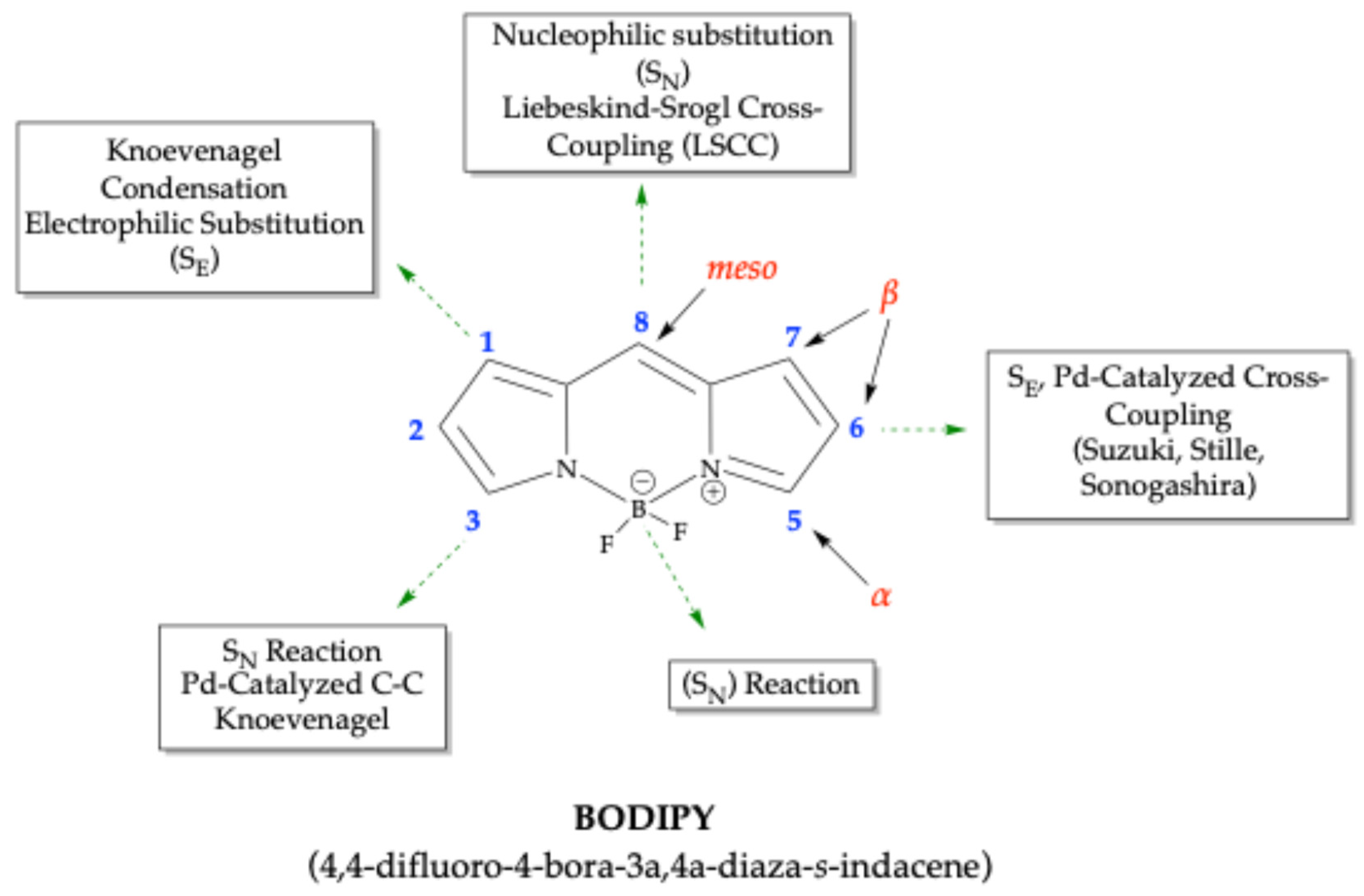

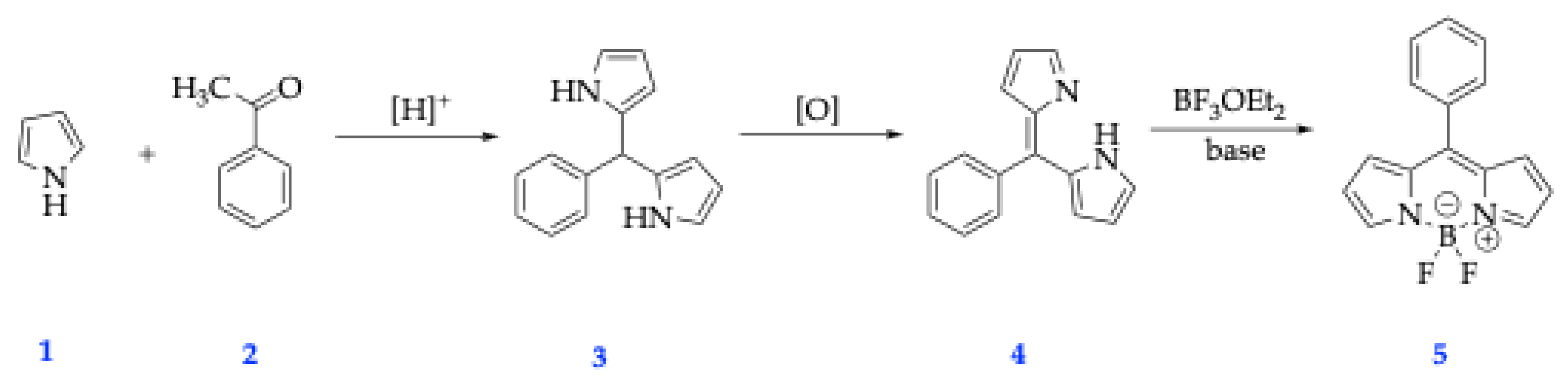

2. Synthesis of BODIPY Dyes

2.1. General Synthetic Strategies for BODIPY Dyes

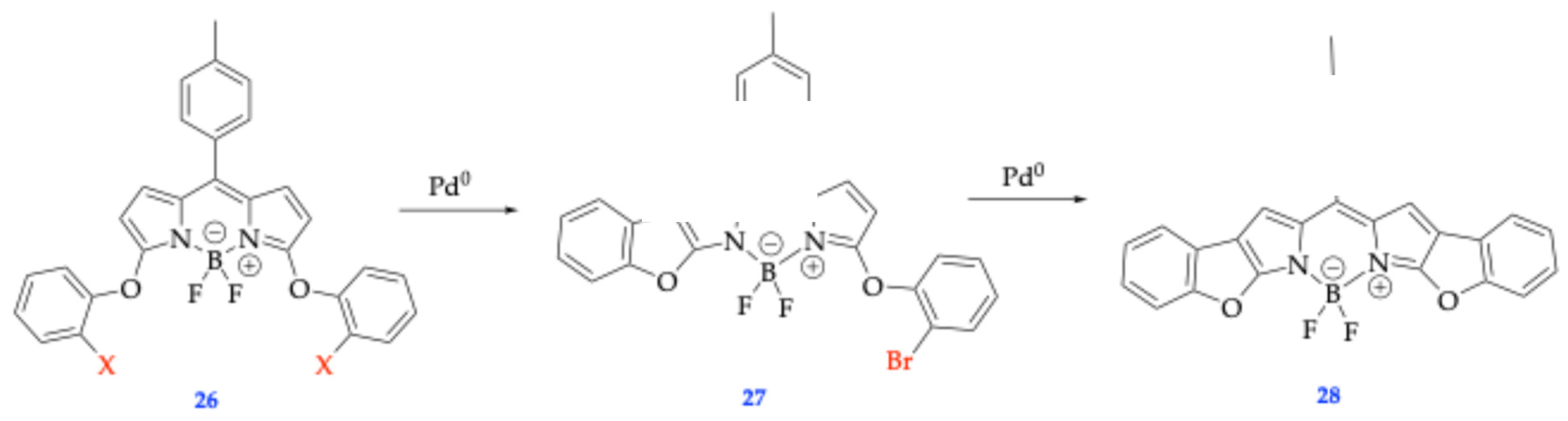

3. Synthesis of Aza-BODIPY Dyes

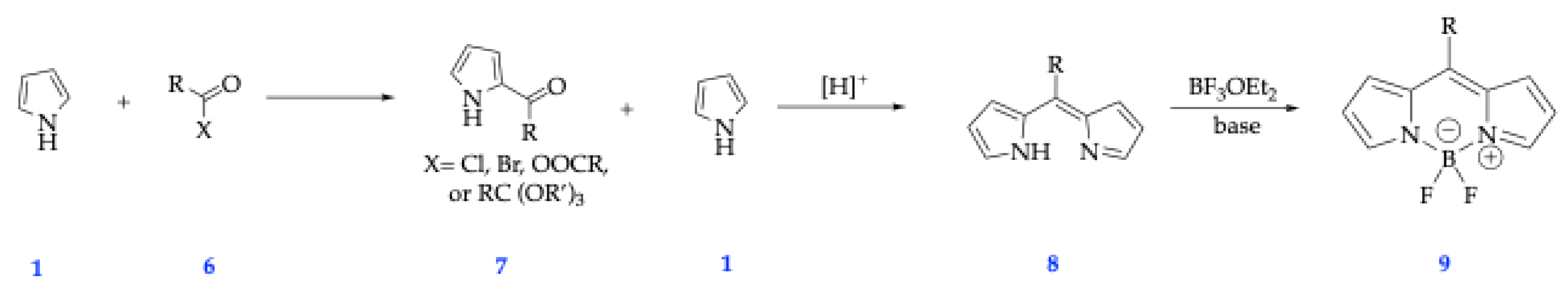

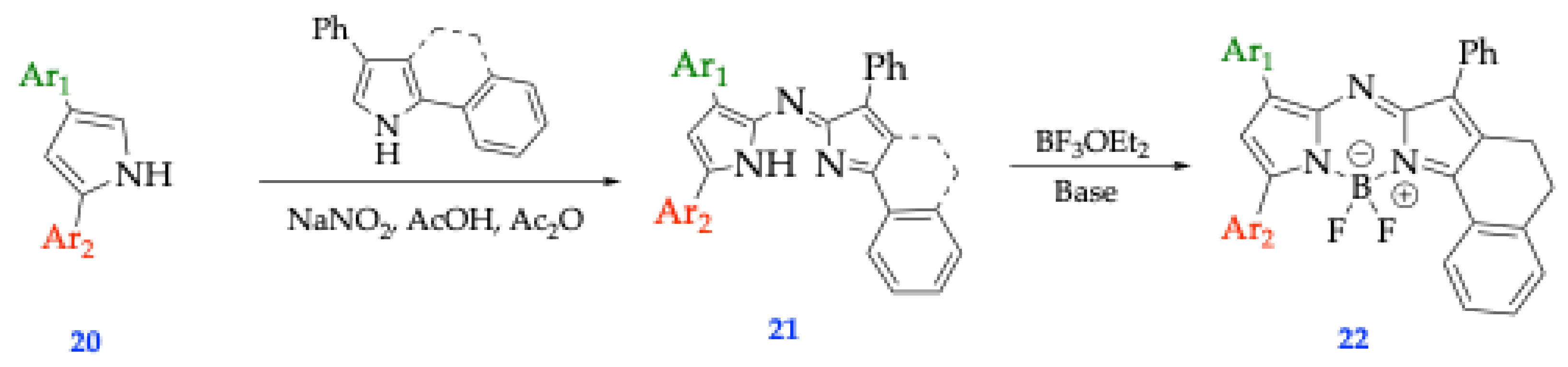

3.1. O’Shea’s Route

3.2. Carriera’s Route

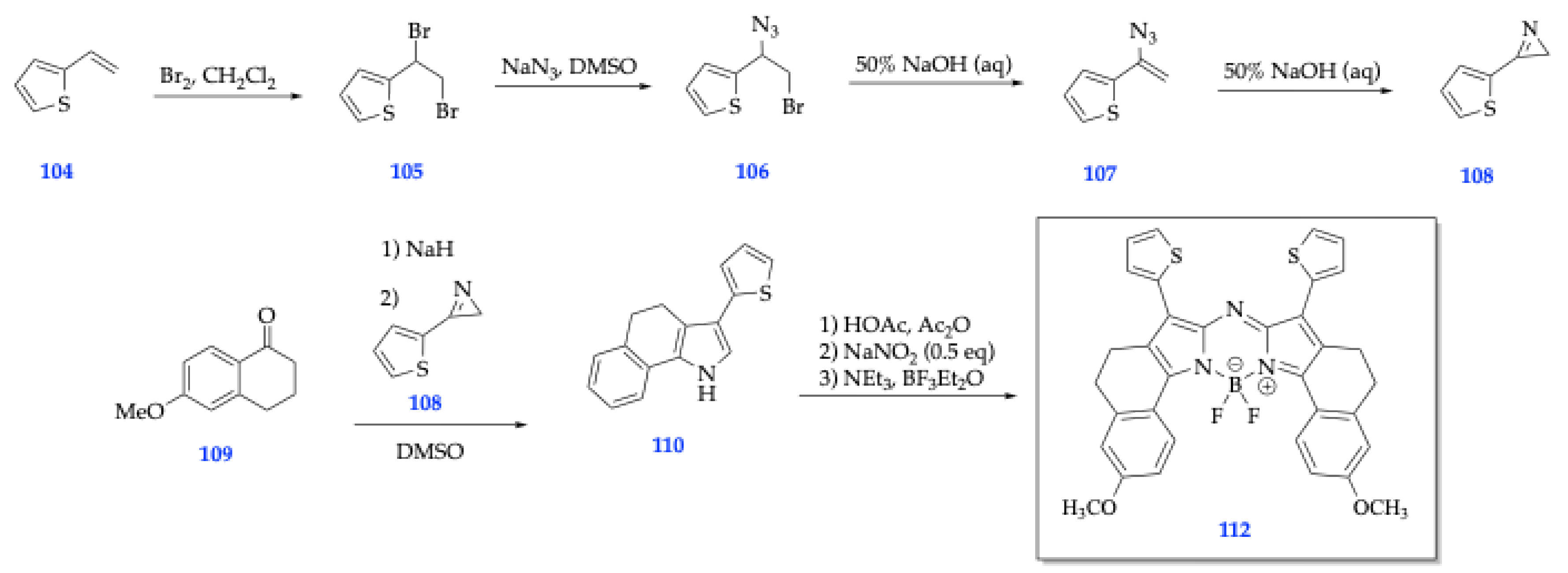

3.3. Lukyanet’s Route

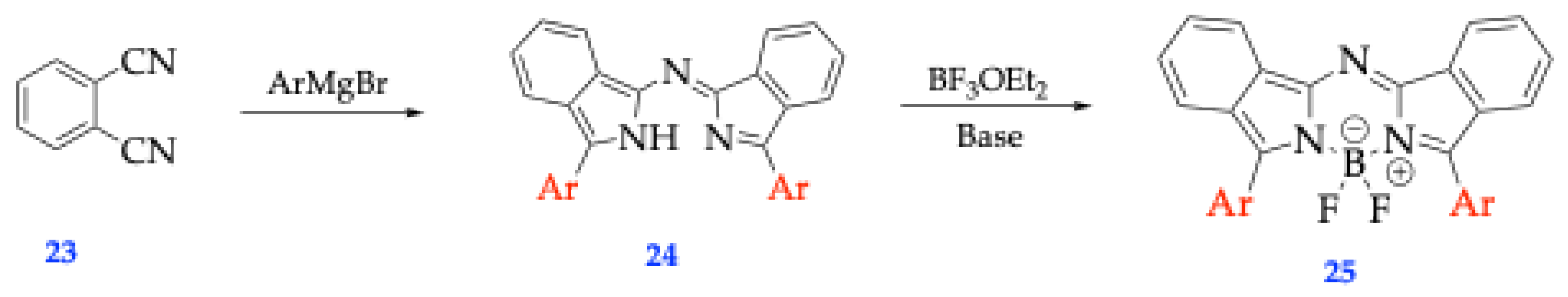

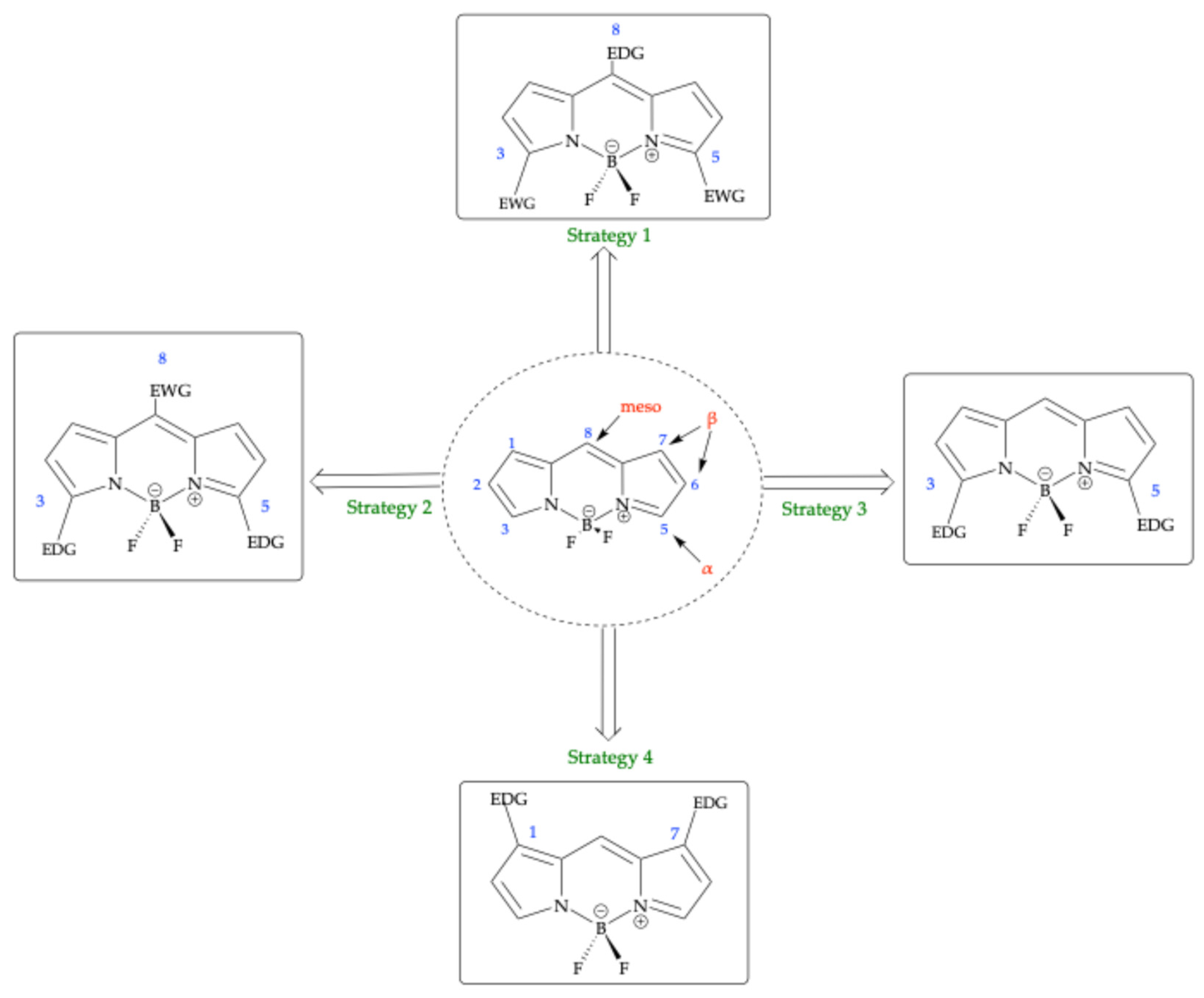

3.4. Strategies to Achieve Bathochromic Shift

3.5. Synthetic Modifications Favoring Bathochromic Shift

4. BODIPY Dyes as Fluorescent Sensors

5. Optical Properties of Selected Compounds

5.1. Two-Photon Absorption

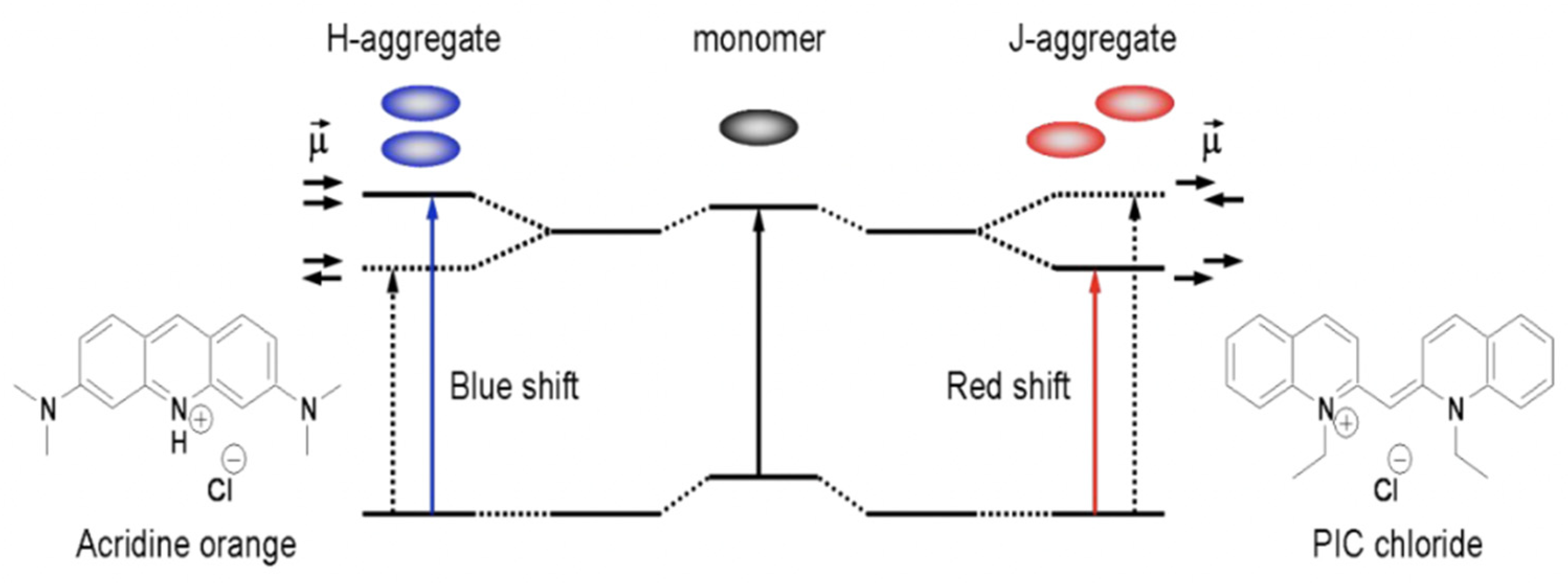

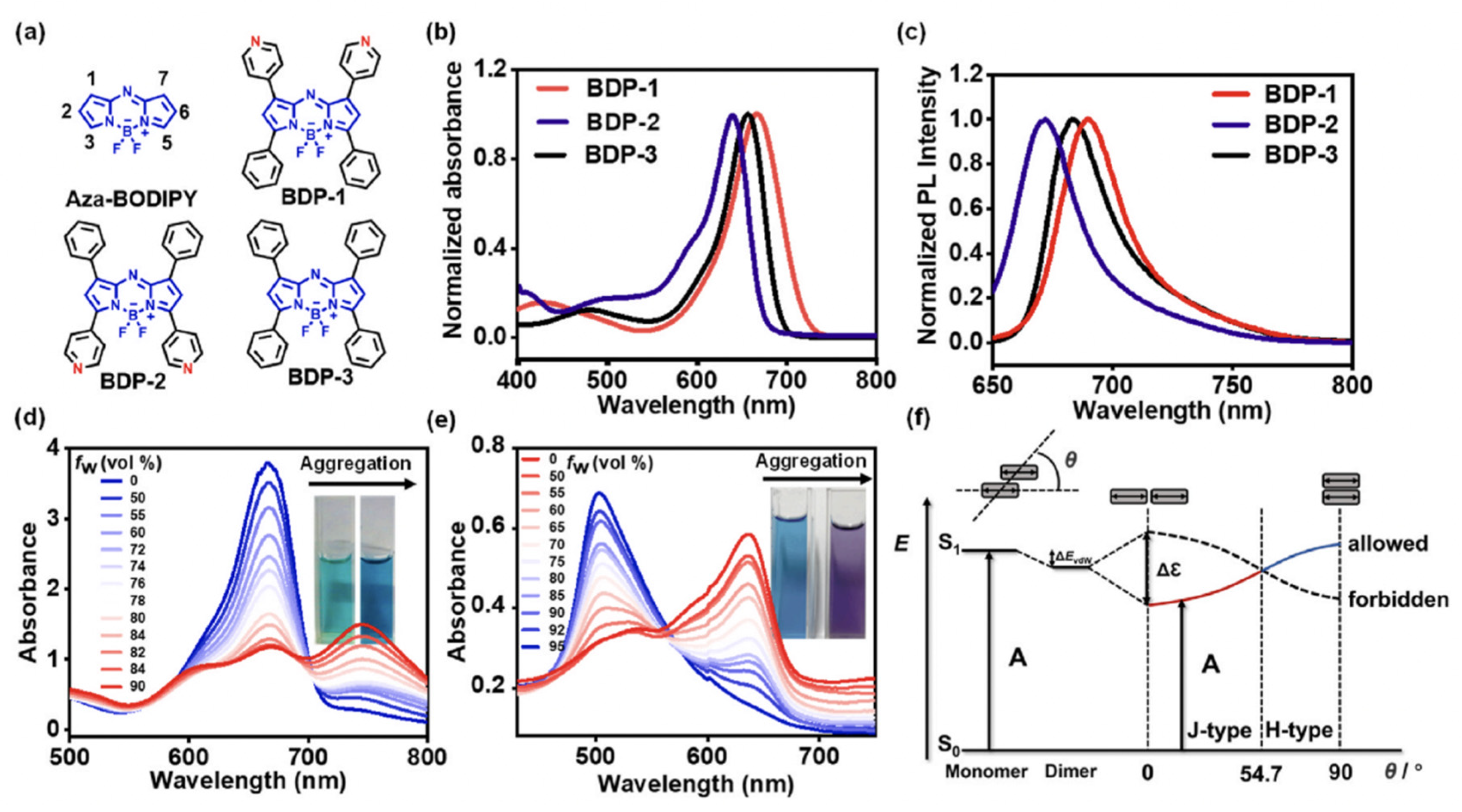

5.2. Aggregation-Induced Emission

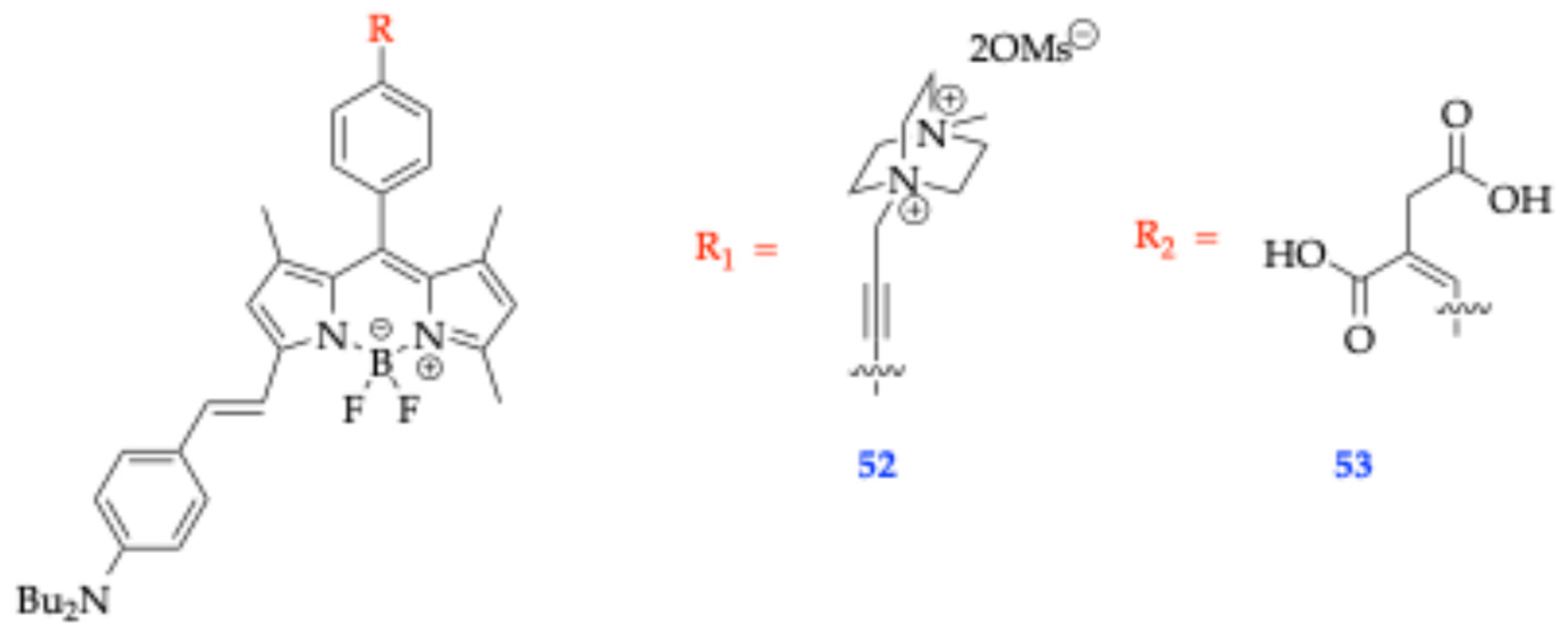

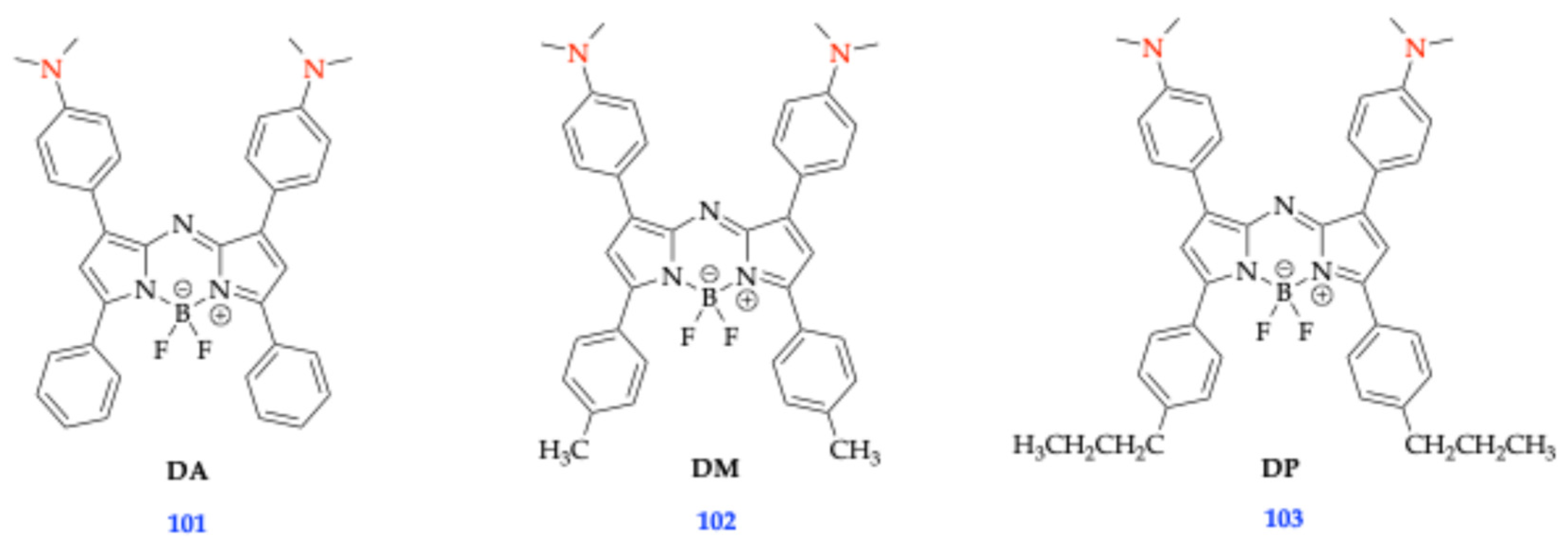

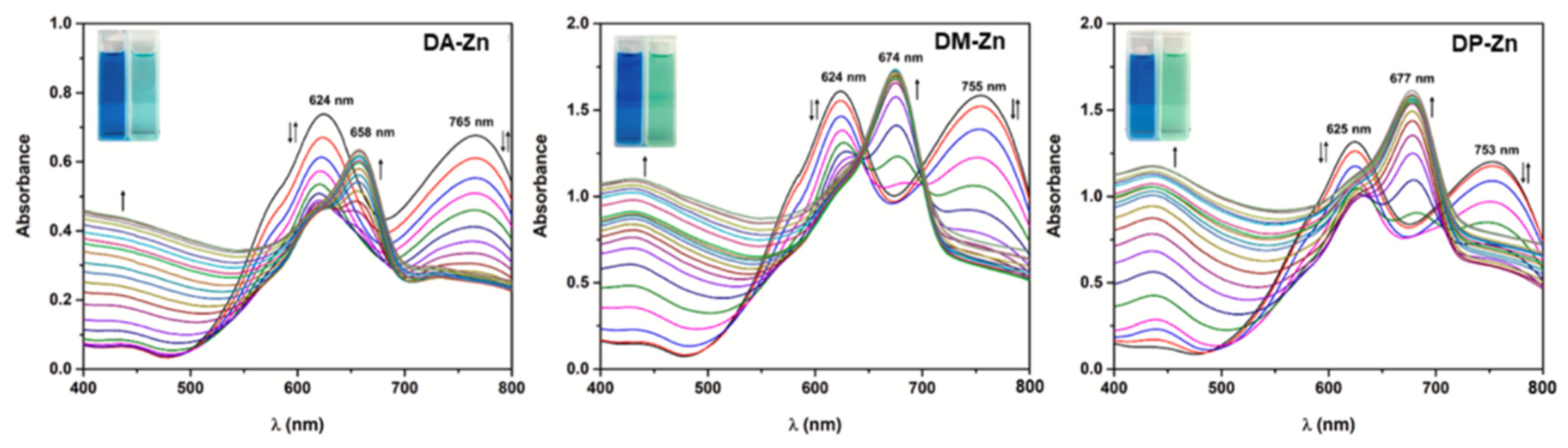

5.3. Spectroscopic Properties of Dicationic and Dianionic BODIPY Dyes

6. Biomedical Applications

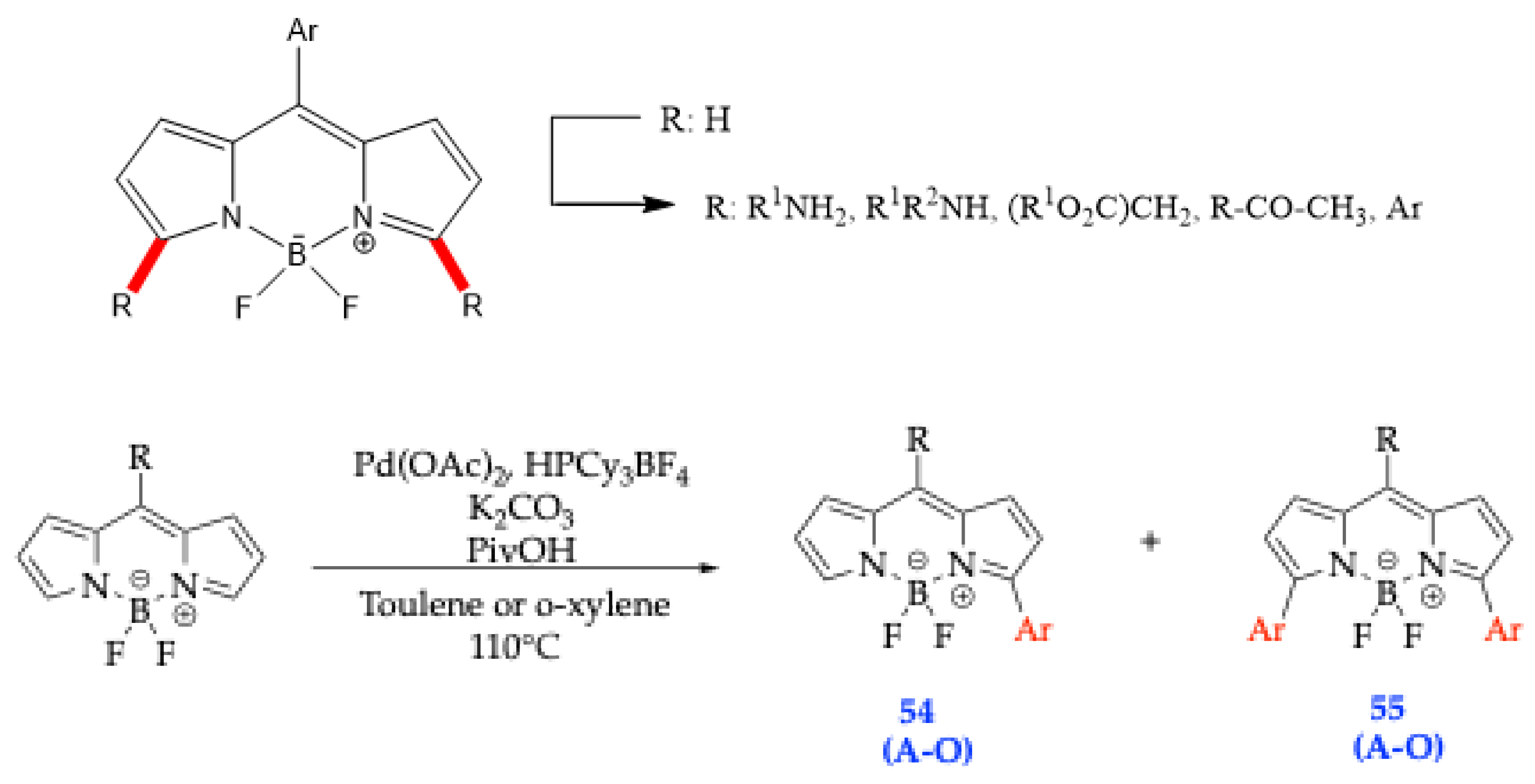

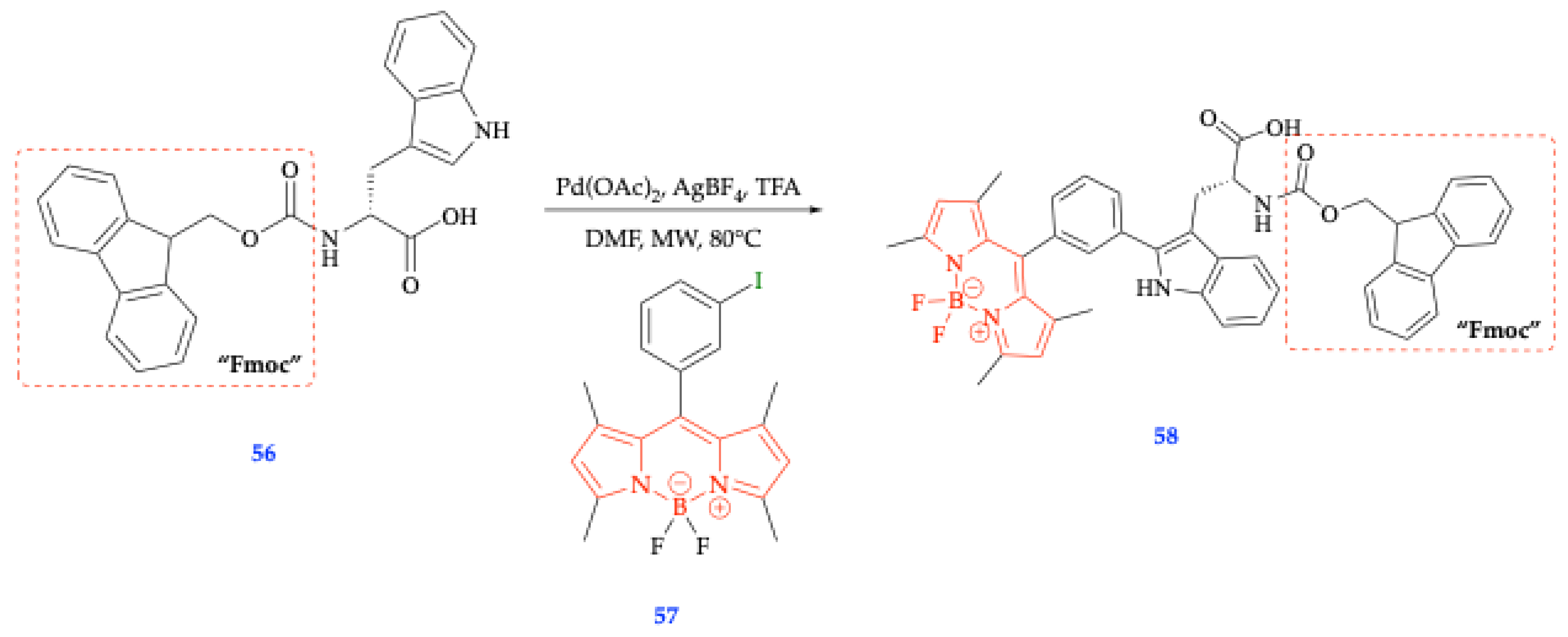

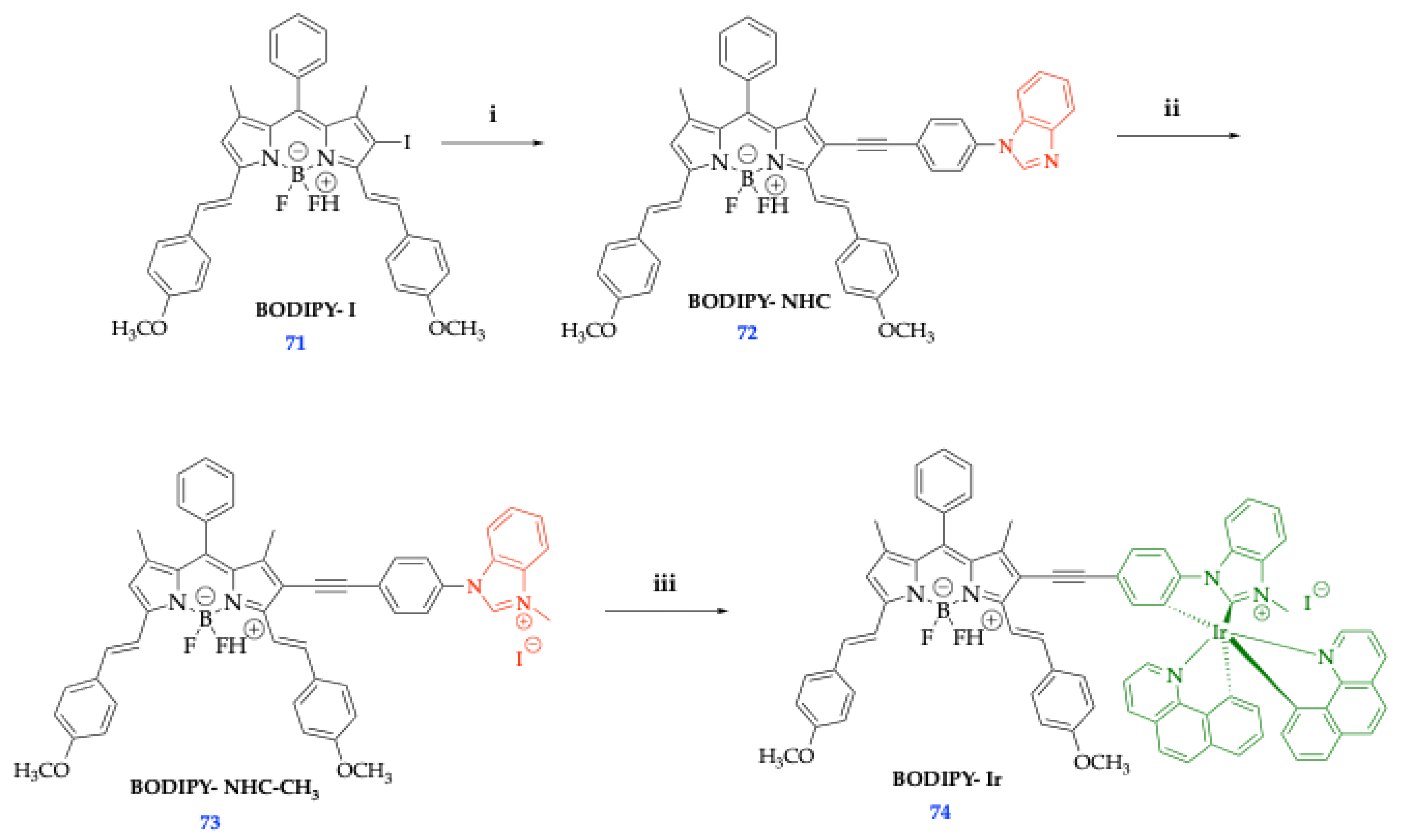

6.1. Metal-Catalyzed C-H Activation Reactions

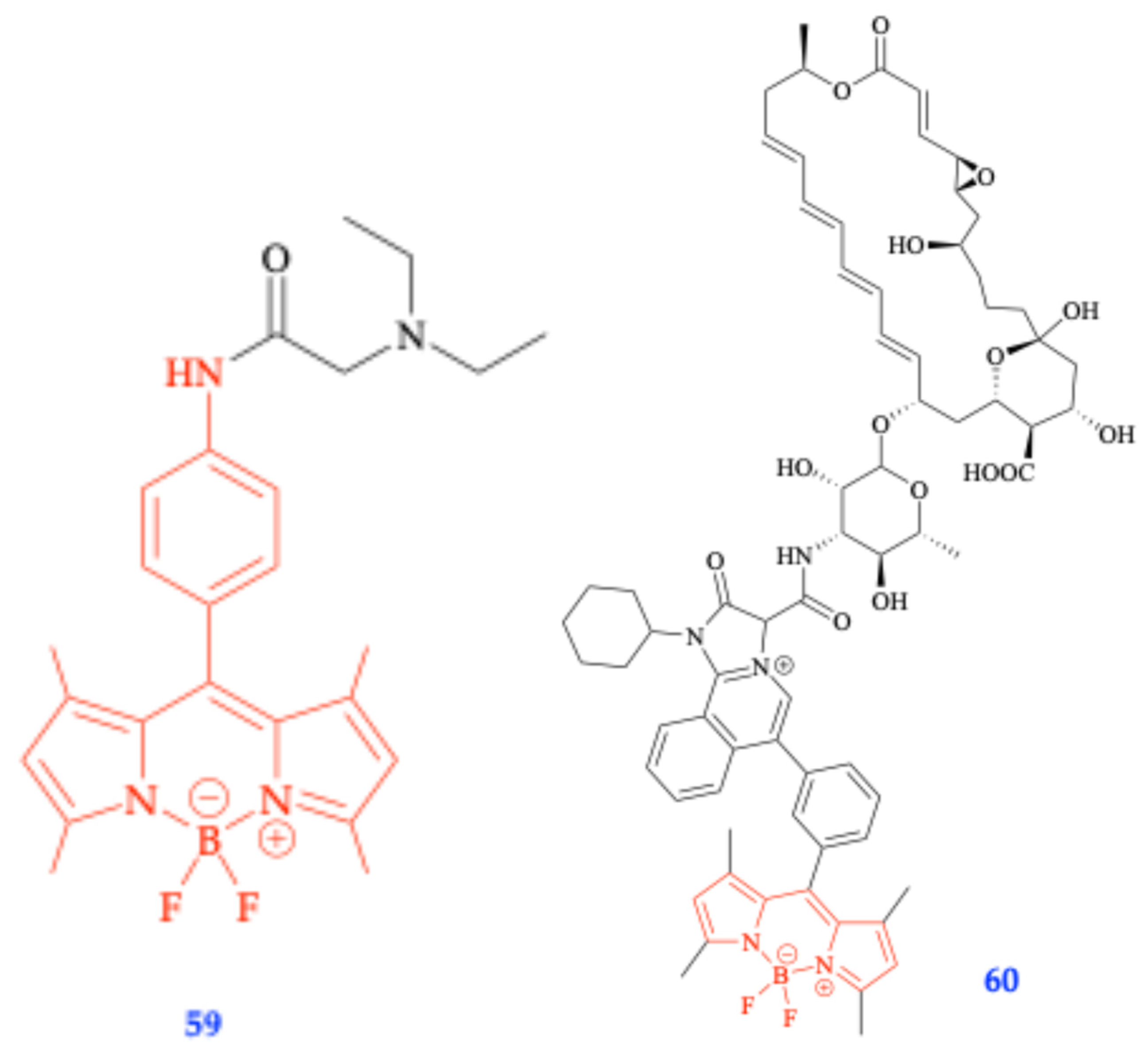

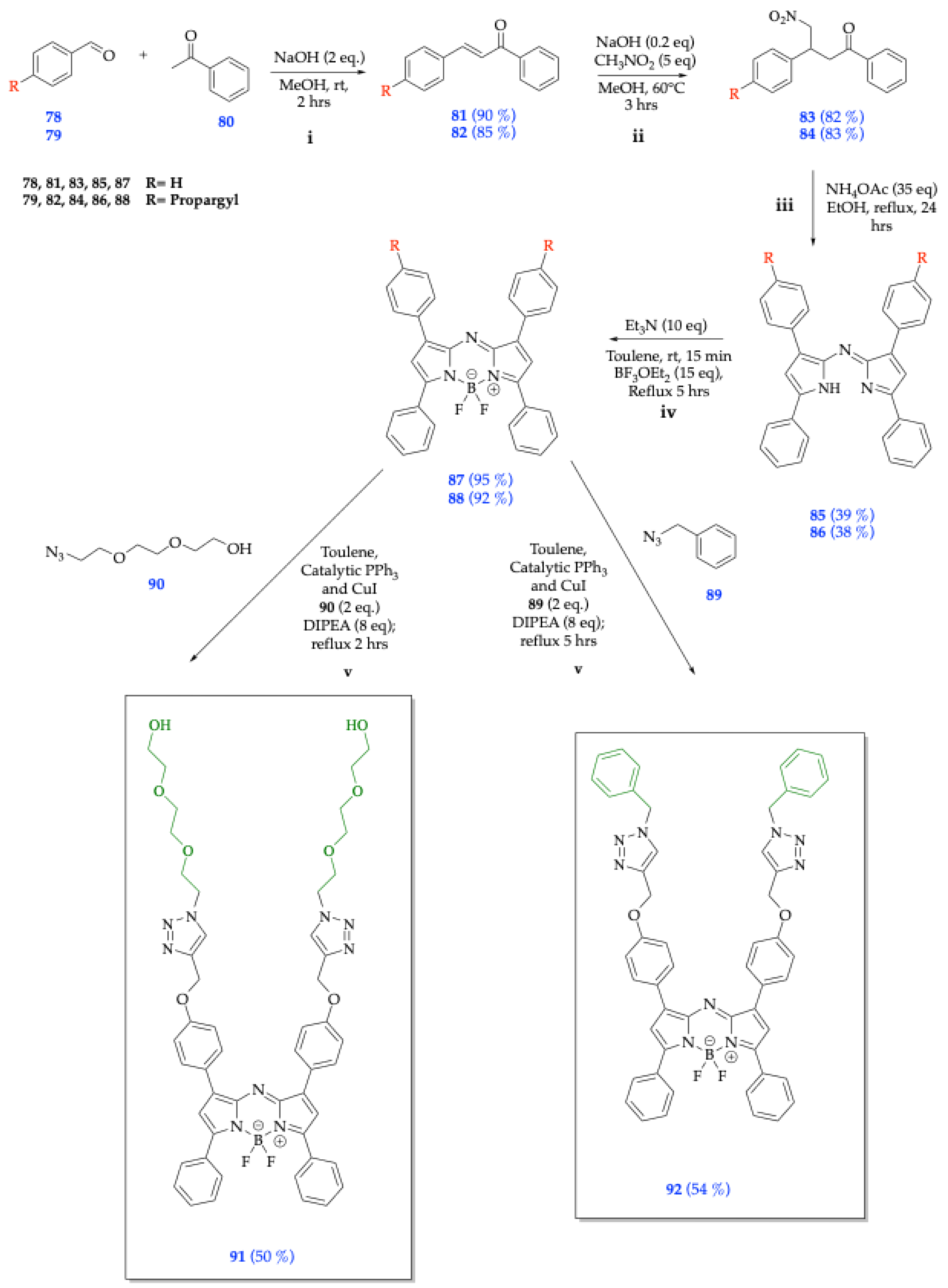

6.2. Functionalized BODIPY Fluorophores for Multicomponent Reactions (MCRs)

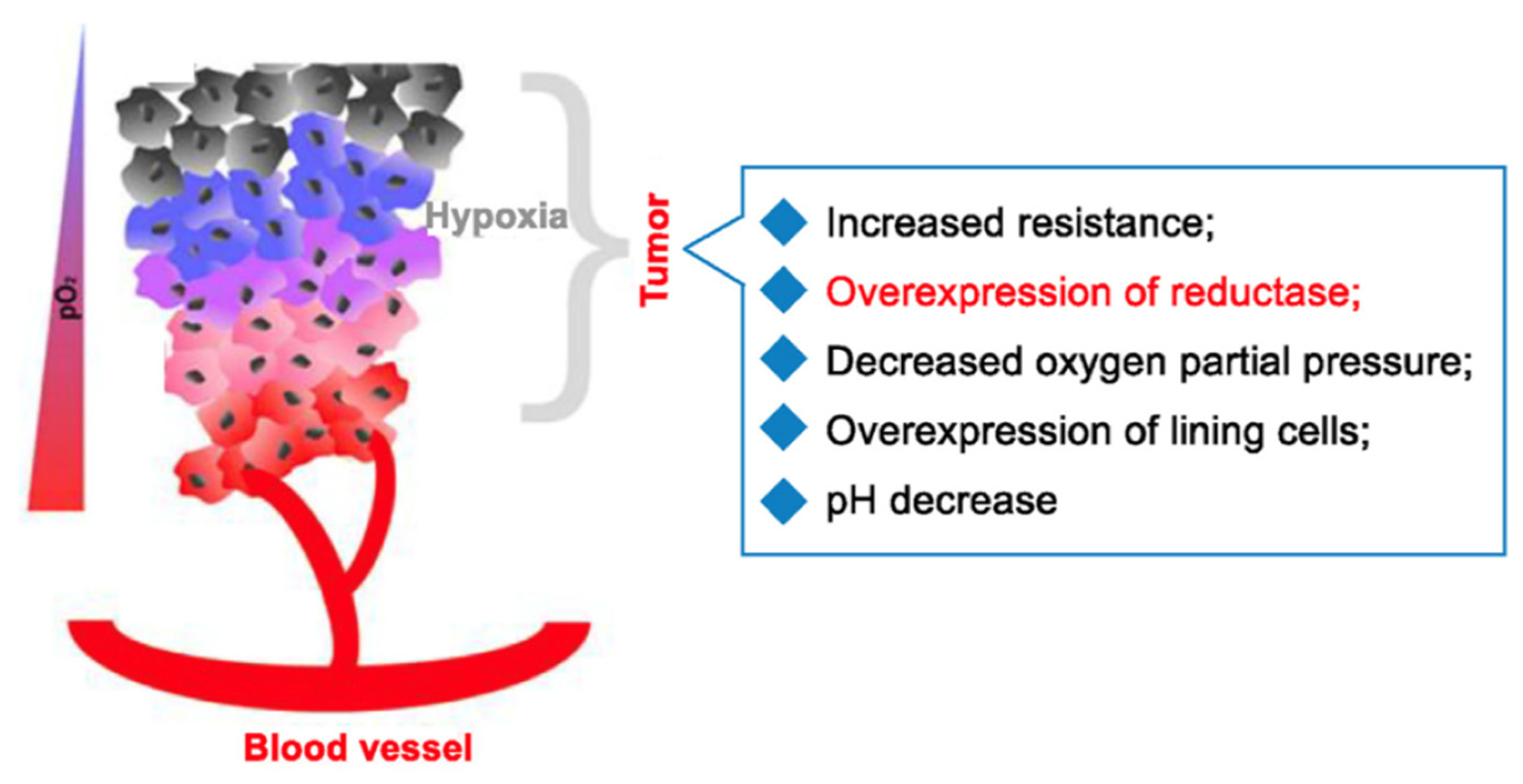

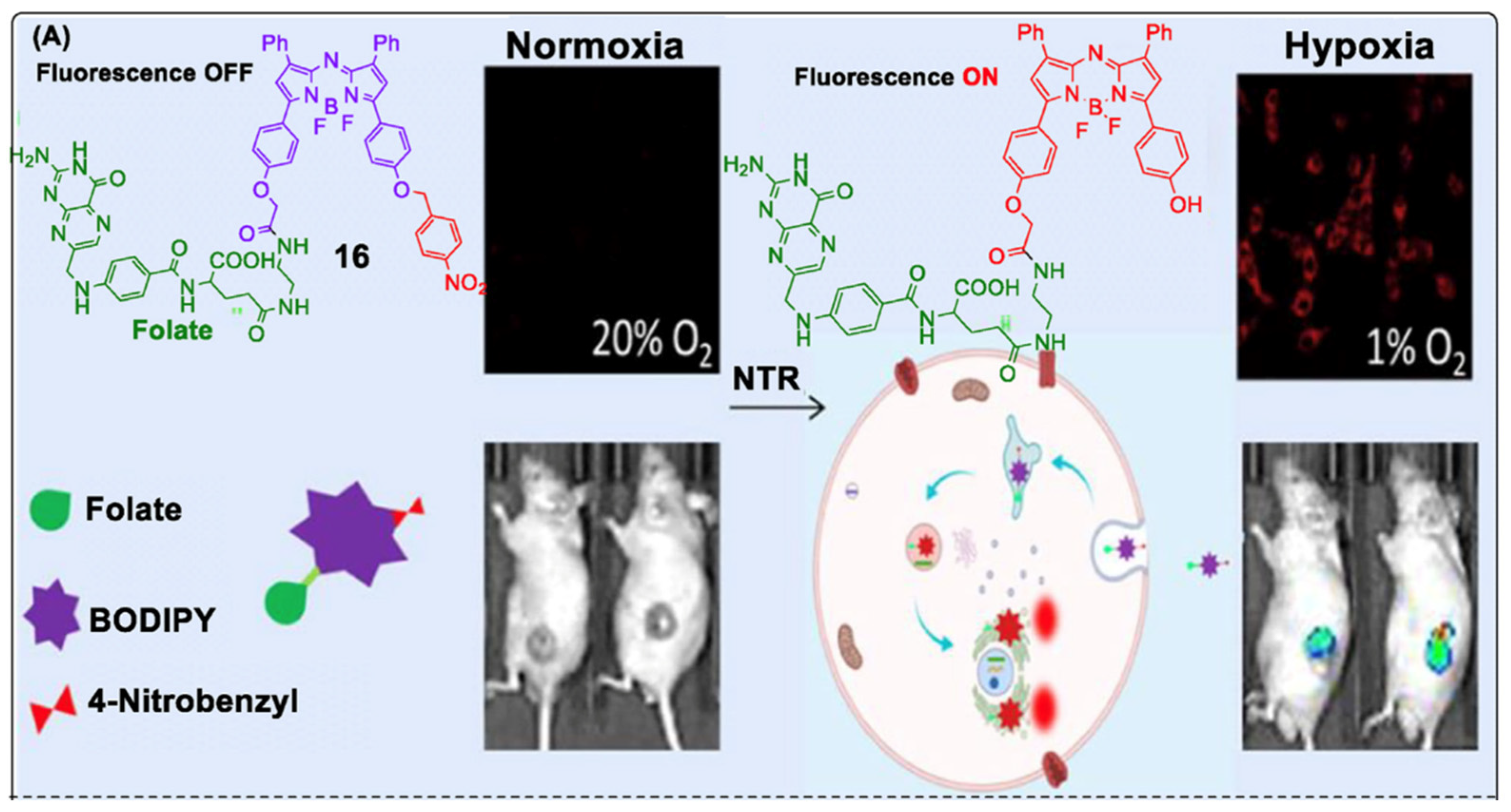

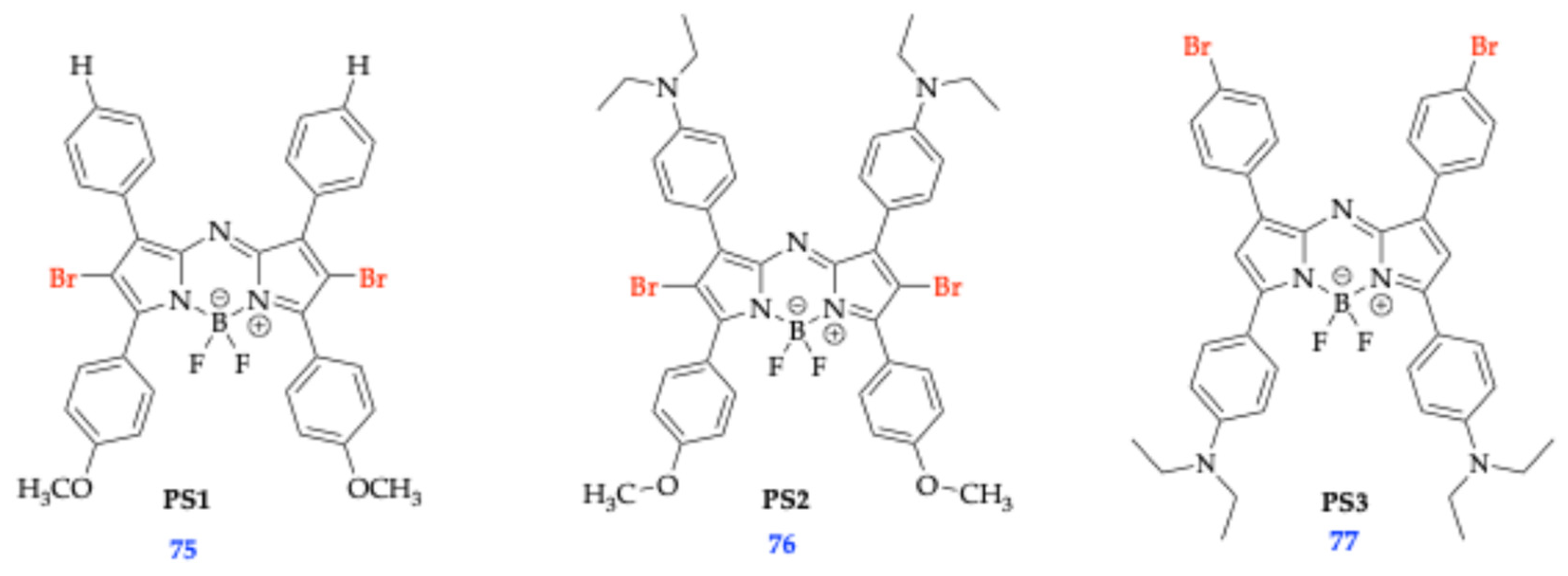

6.3. Activatable Photosensitizer Design Considerations

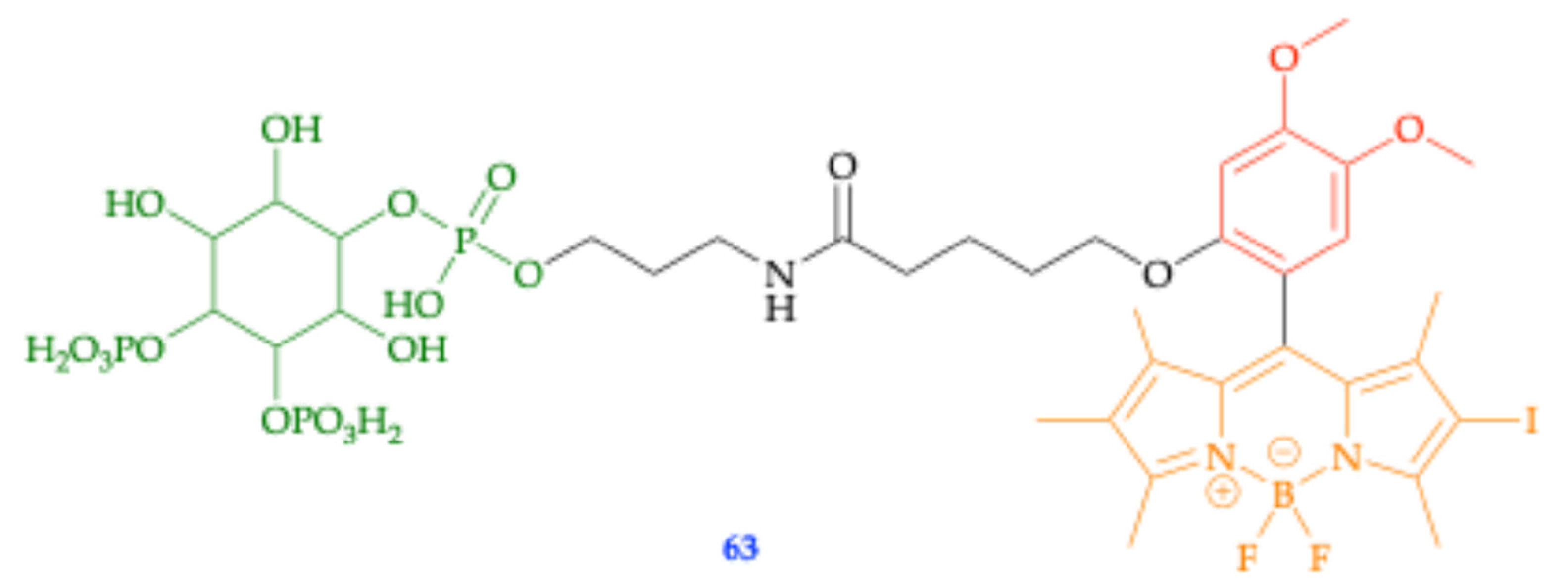

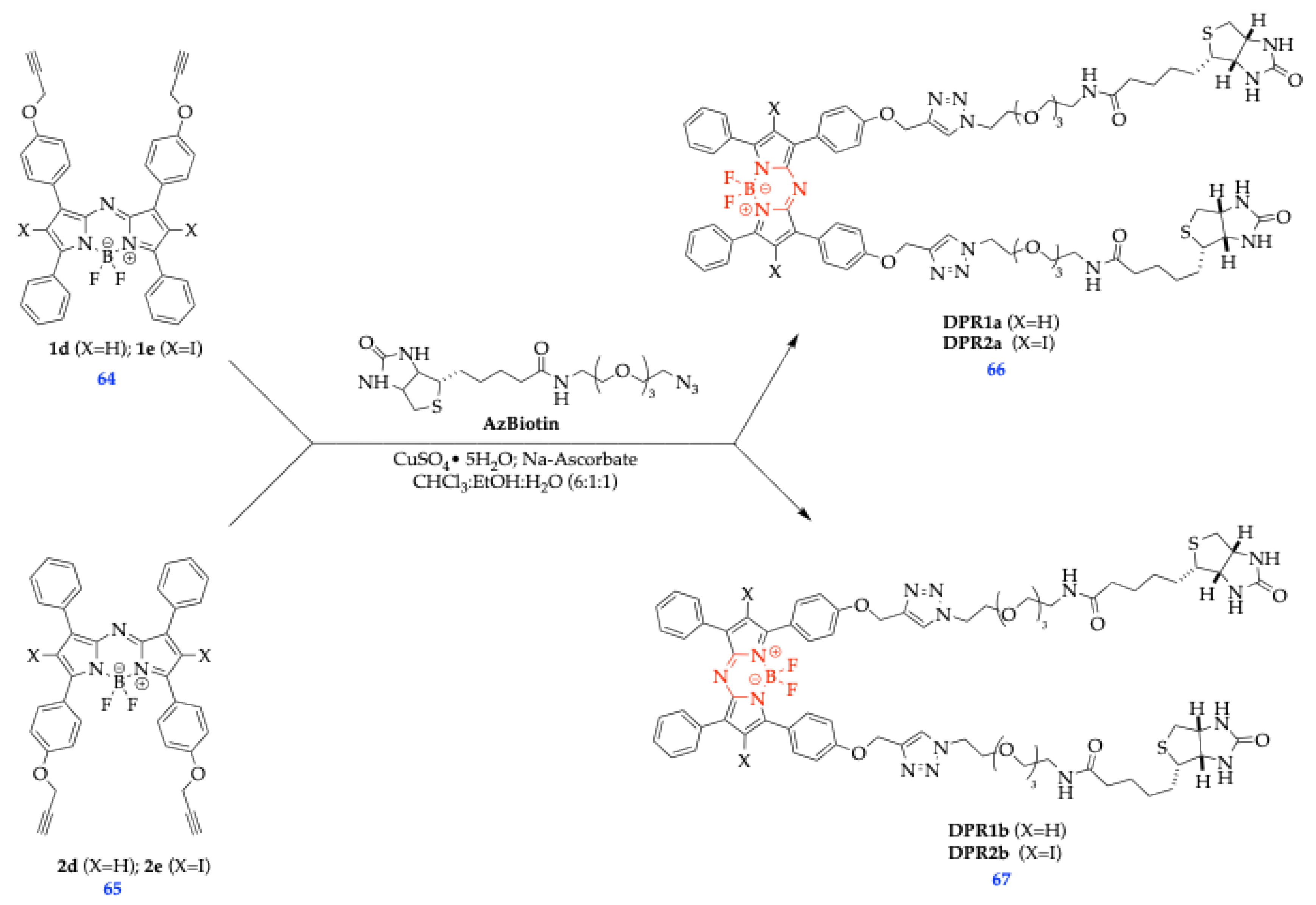

6.4. Biocompatible Aza-BODIPY Biotin Conjugates and Nanoparticles for PDT

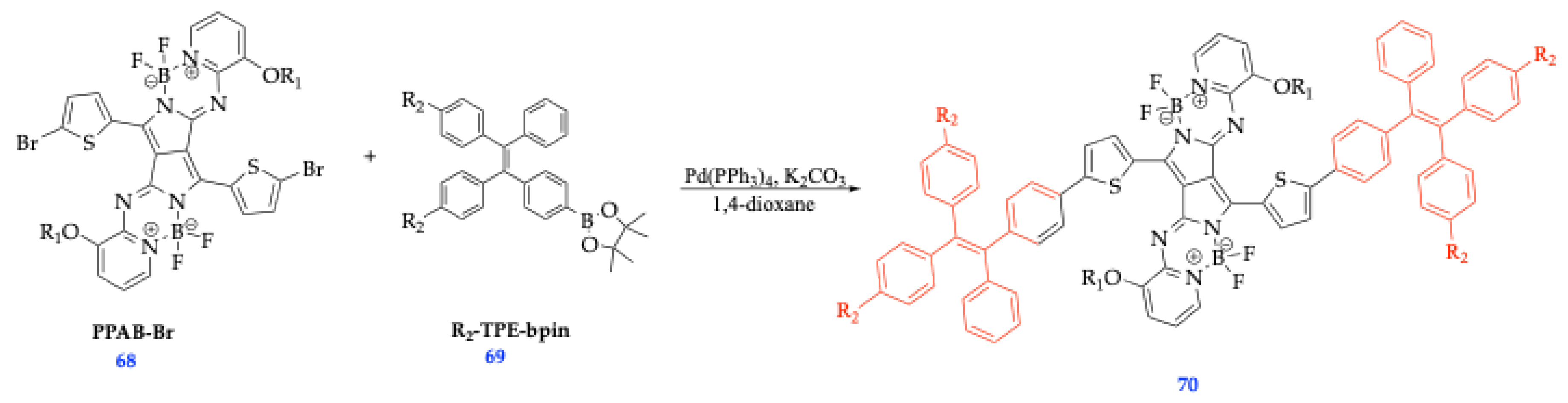

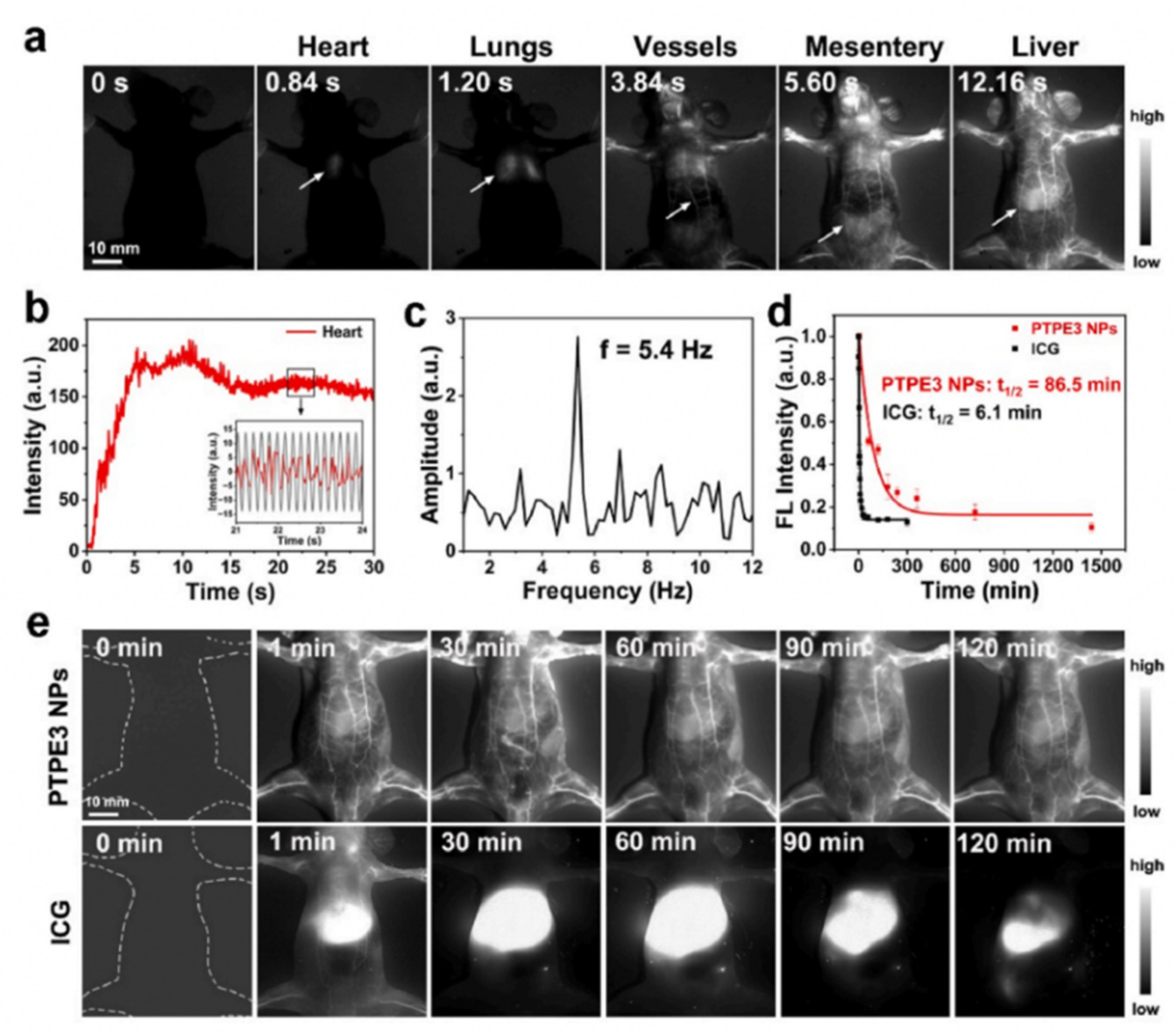

6.5. Development of NIR-II Aza-BODIPY Fluorophores

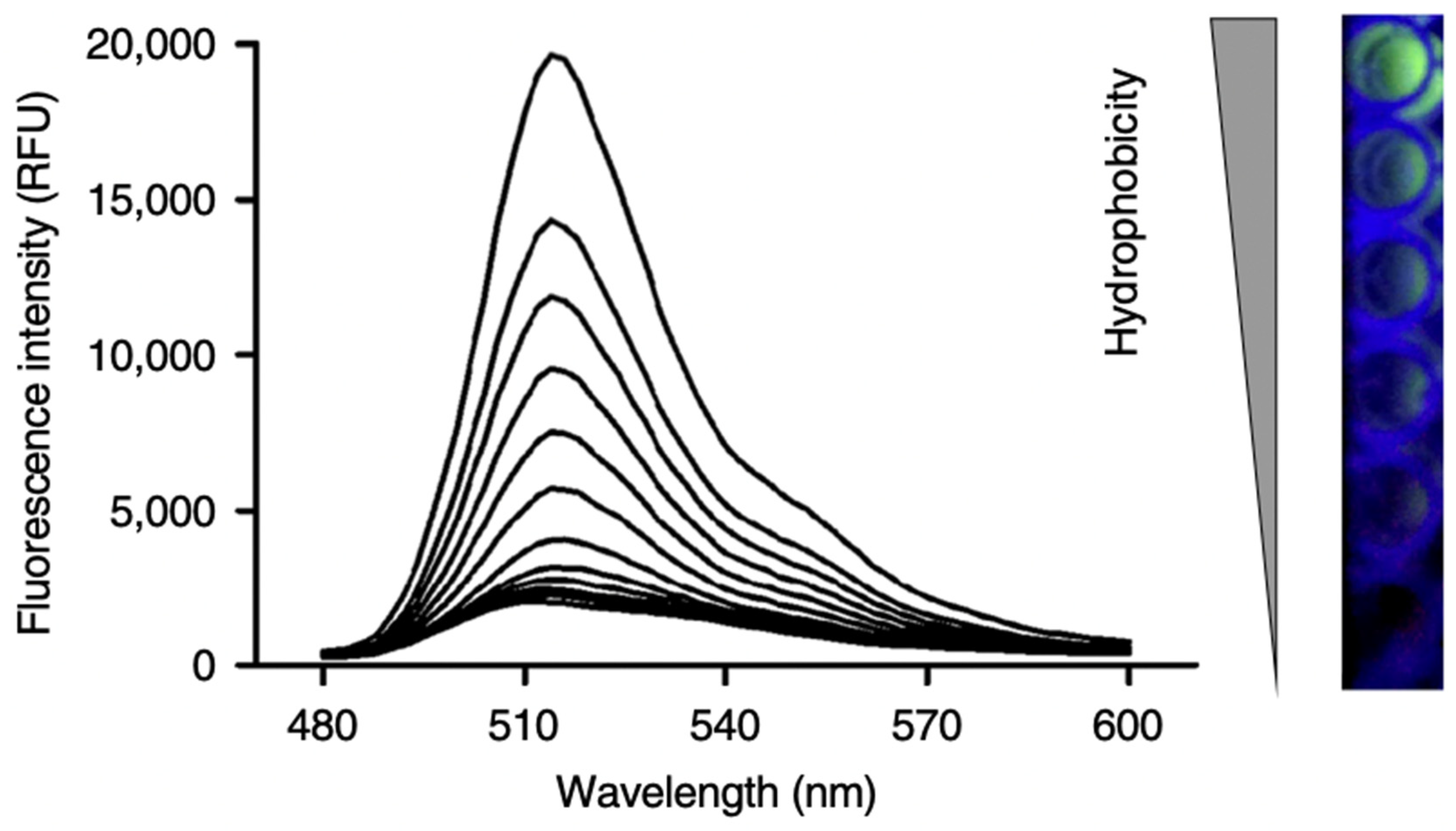

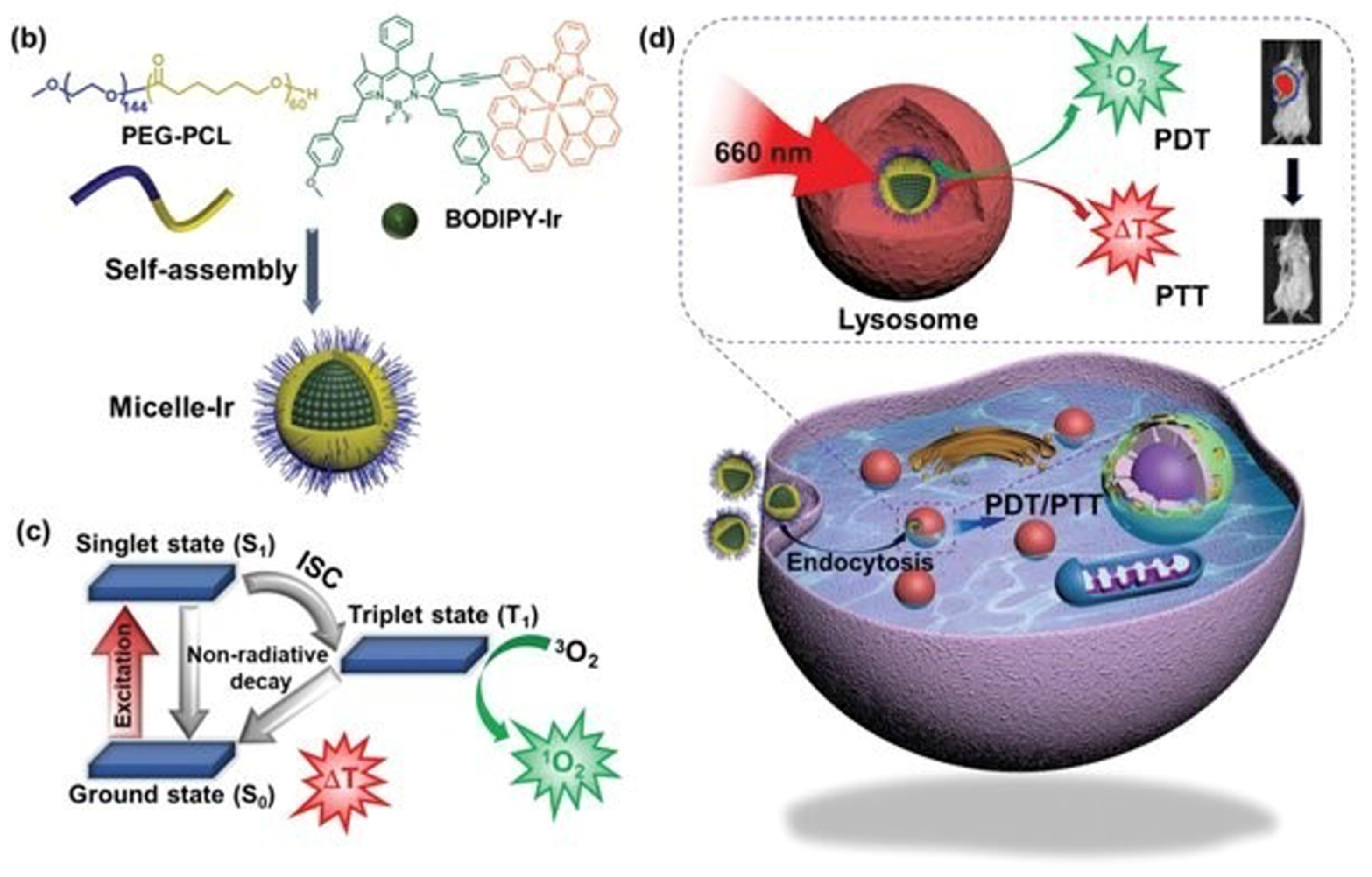

6.6. Self-Assembly of Polymeric BODIPY Micelles for Fluorescence Imaging

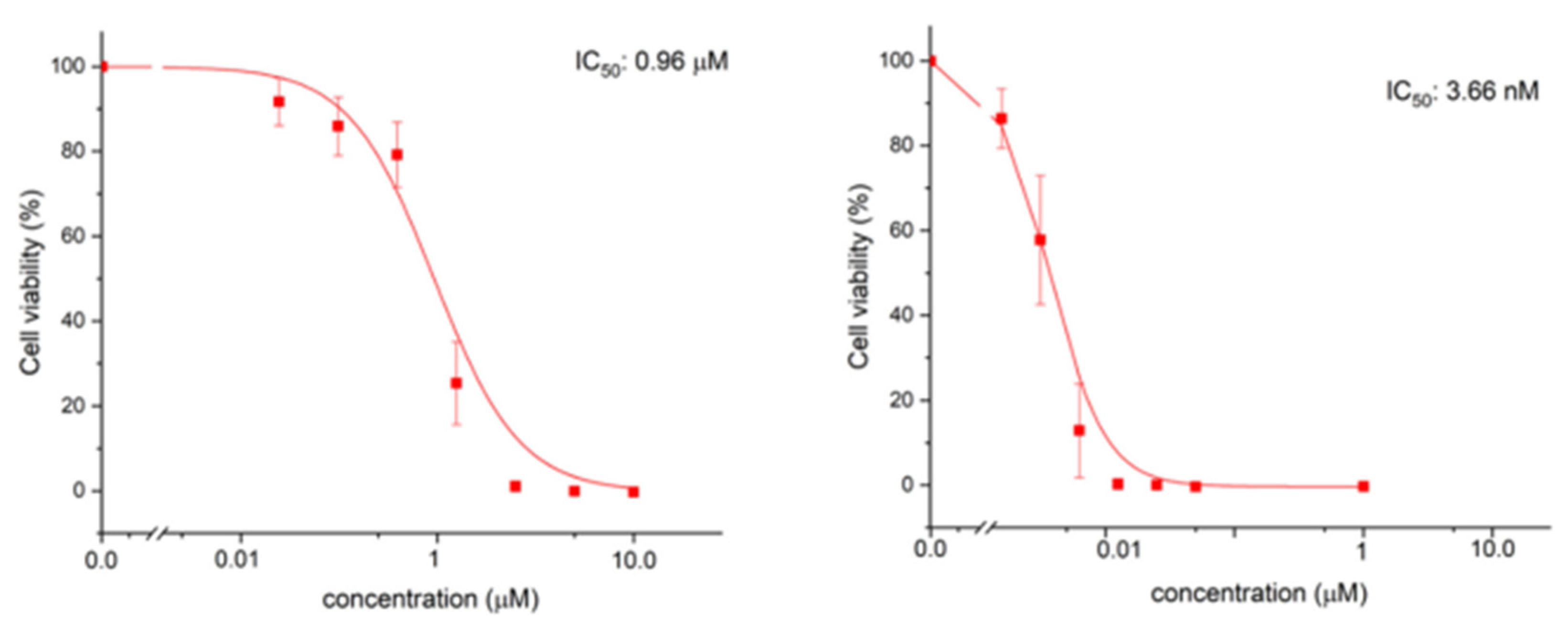

6.7. Advances in Cell Tracking and Cancer Detection Applications

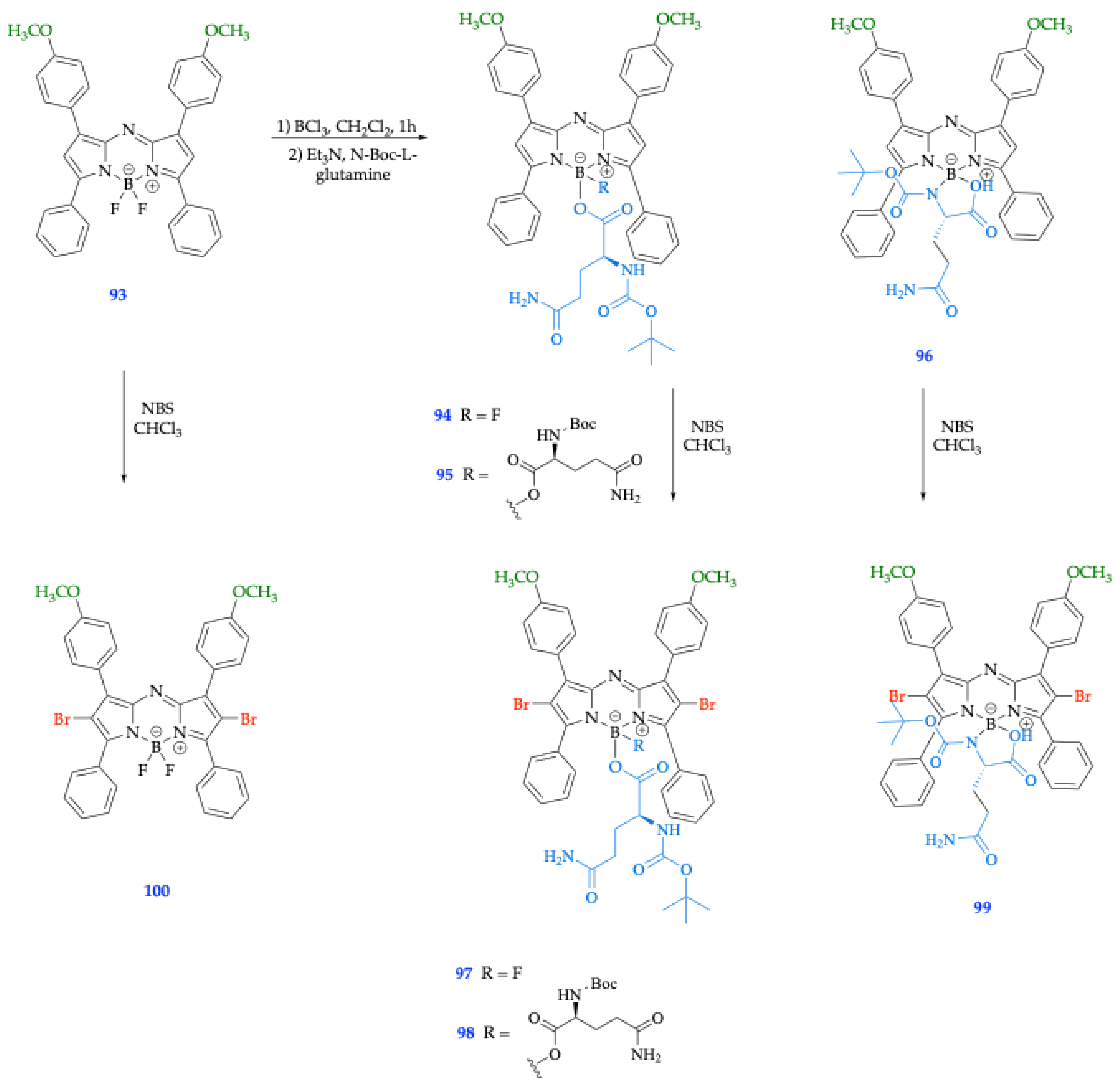

6.8. Boron Functionalization: Forming Linker-Free NIR Aza-BODIPY Glutamine Conjugates

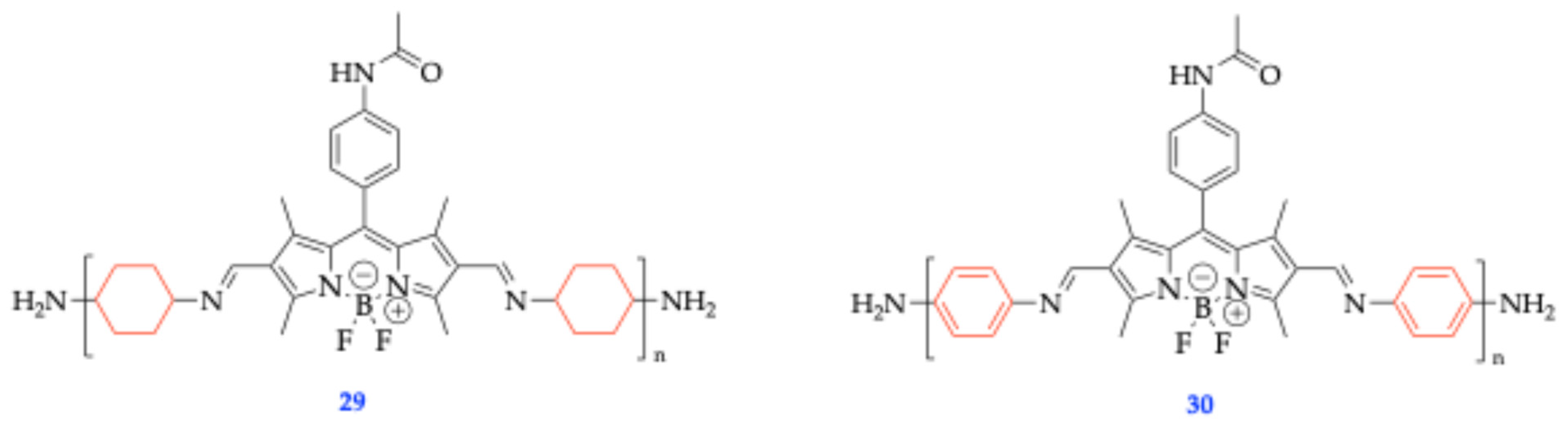

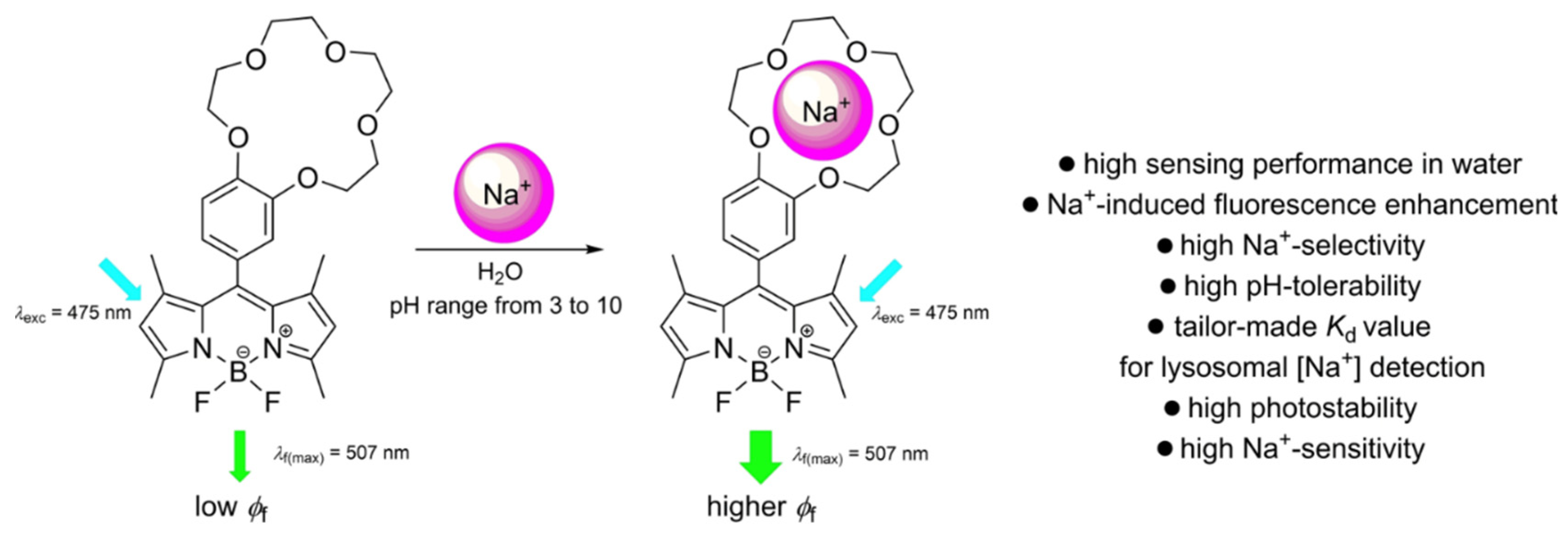

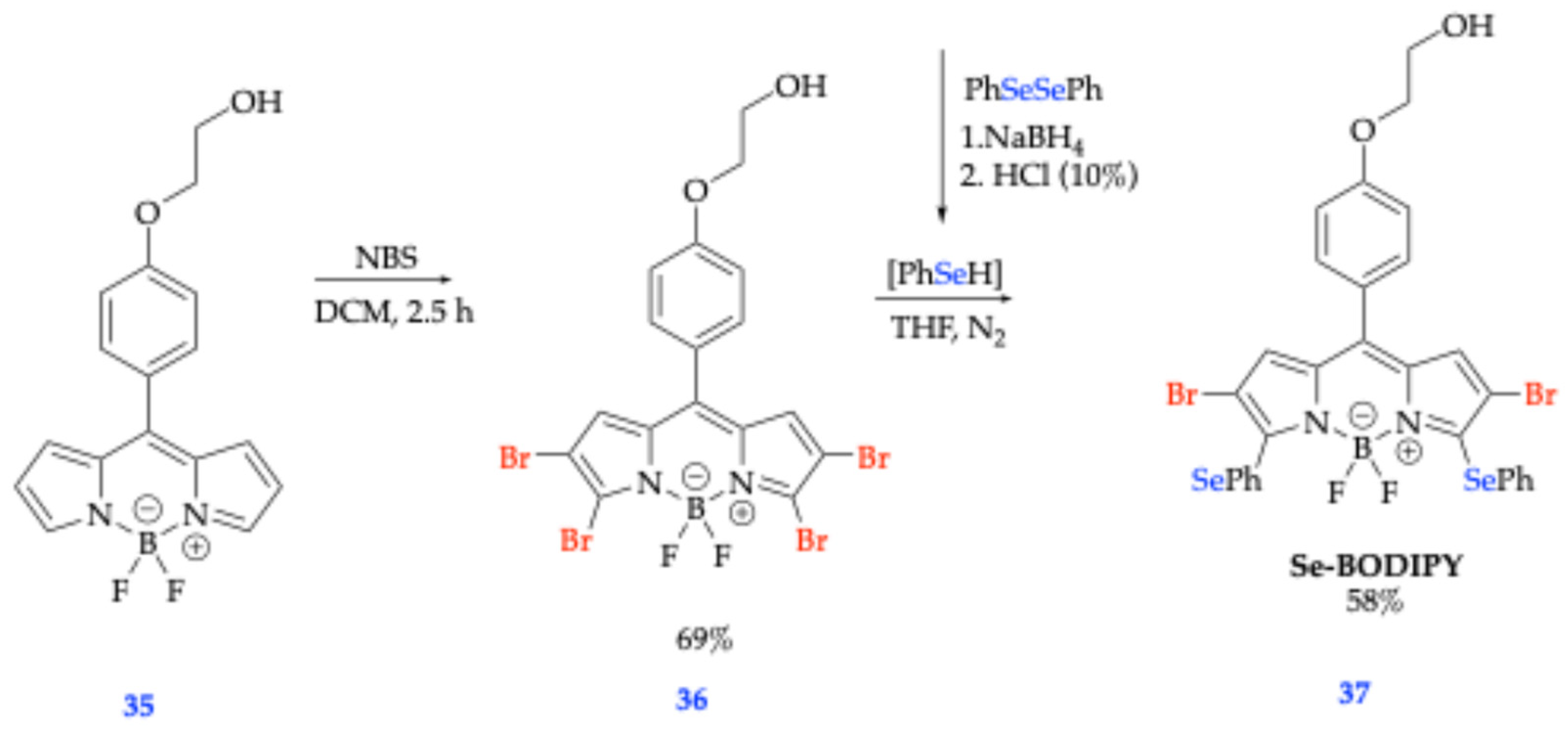

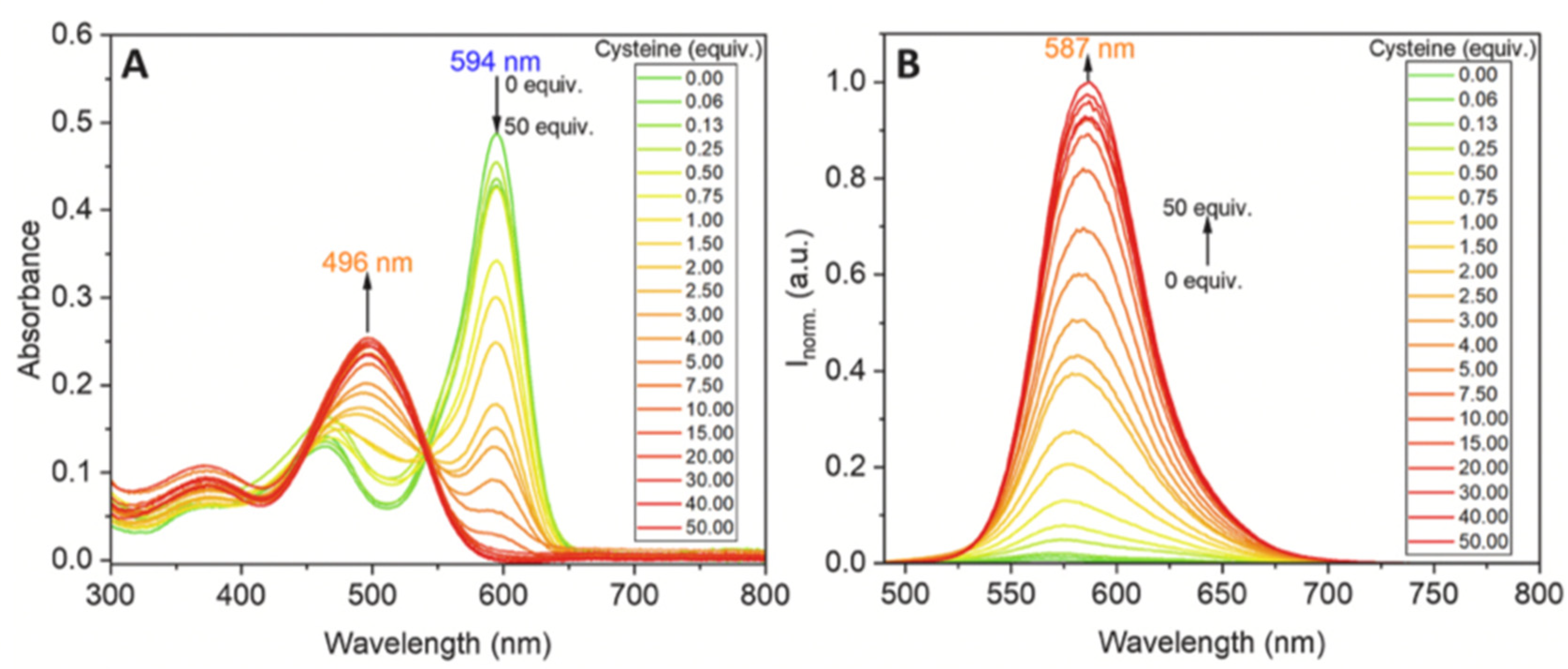

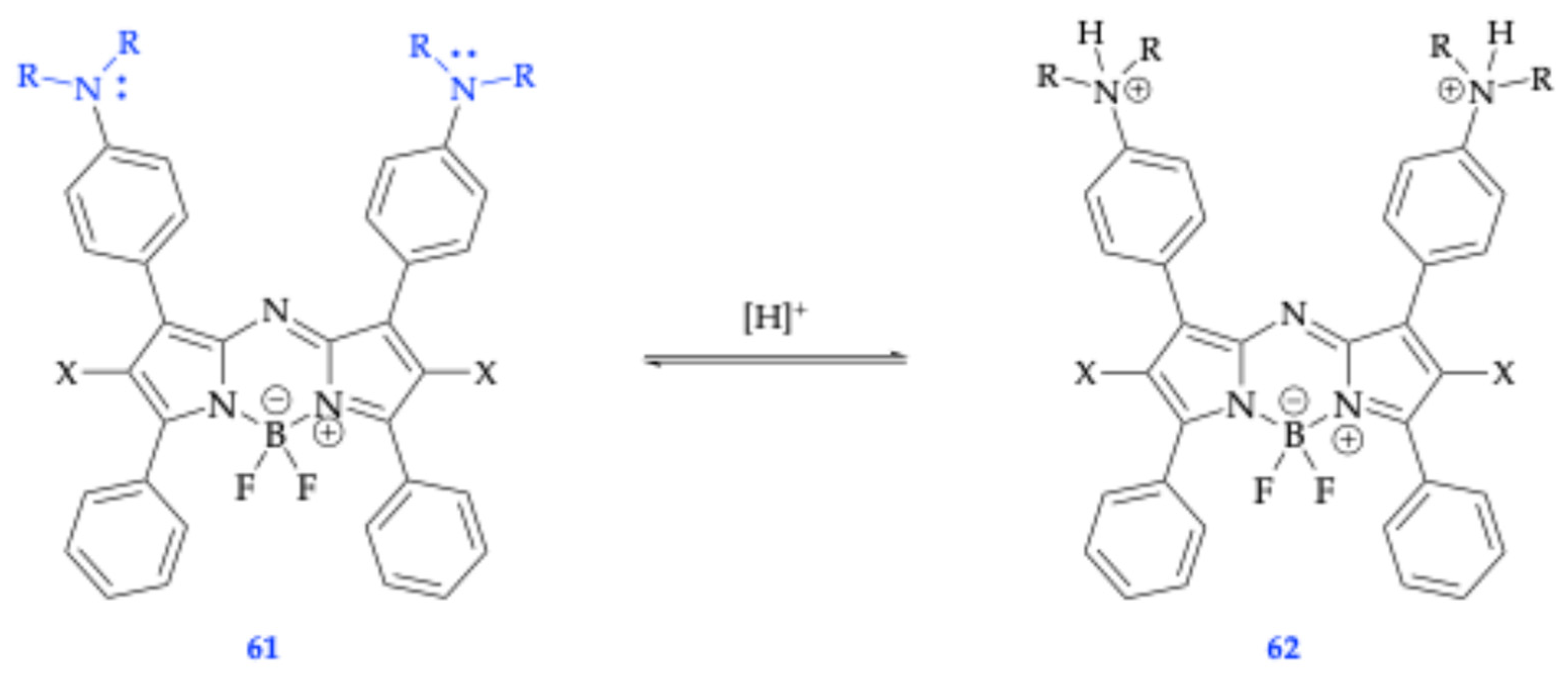

7. Biosensing, Chemosensing, and pH Sensing Applications

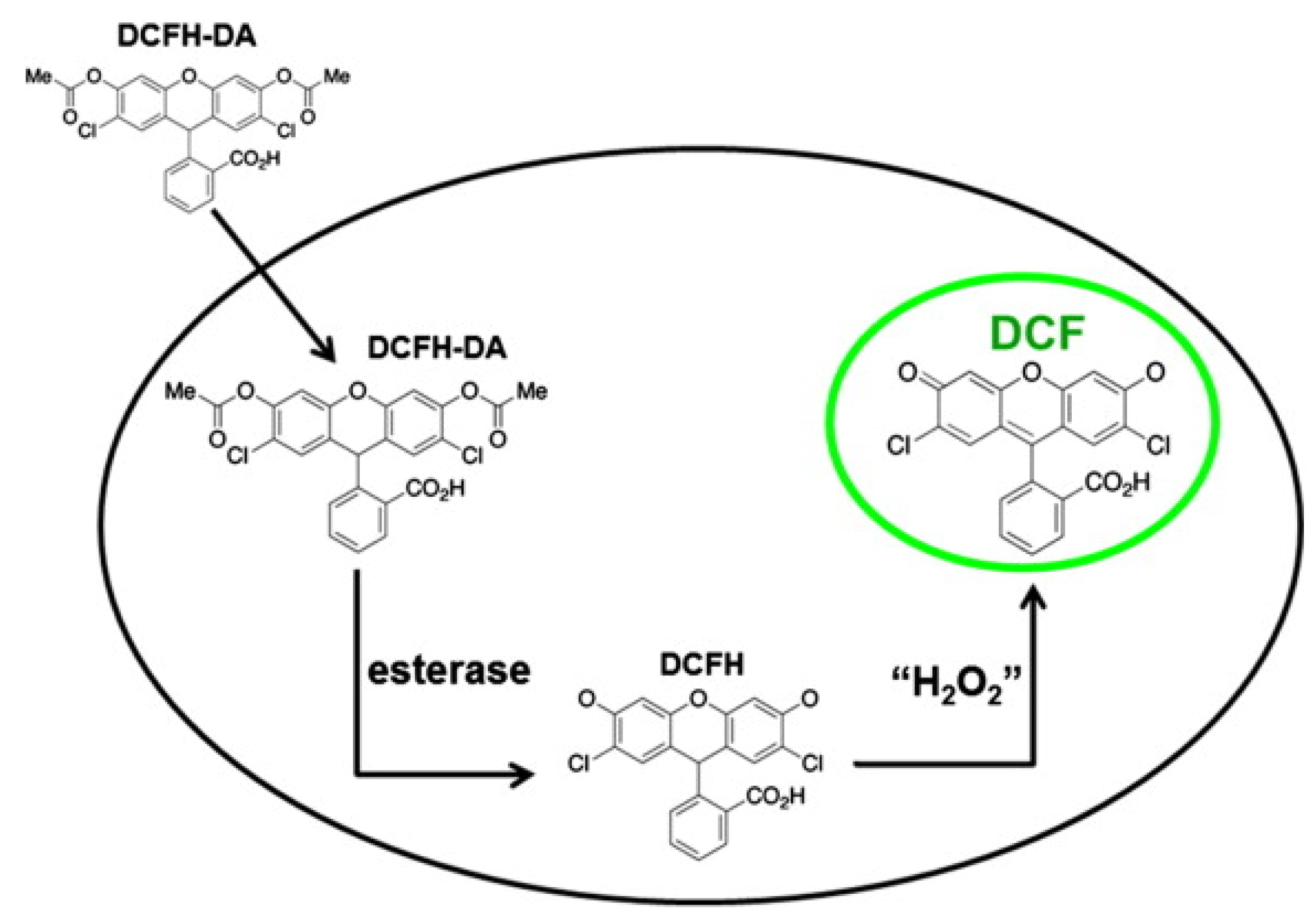

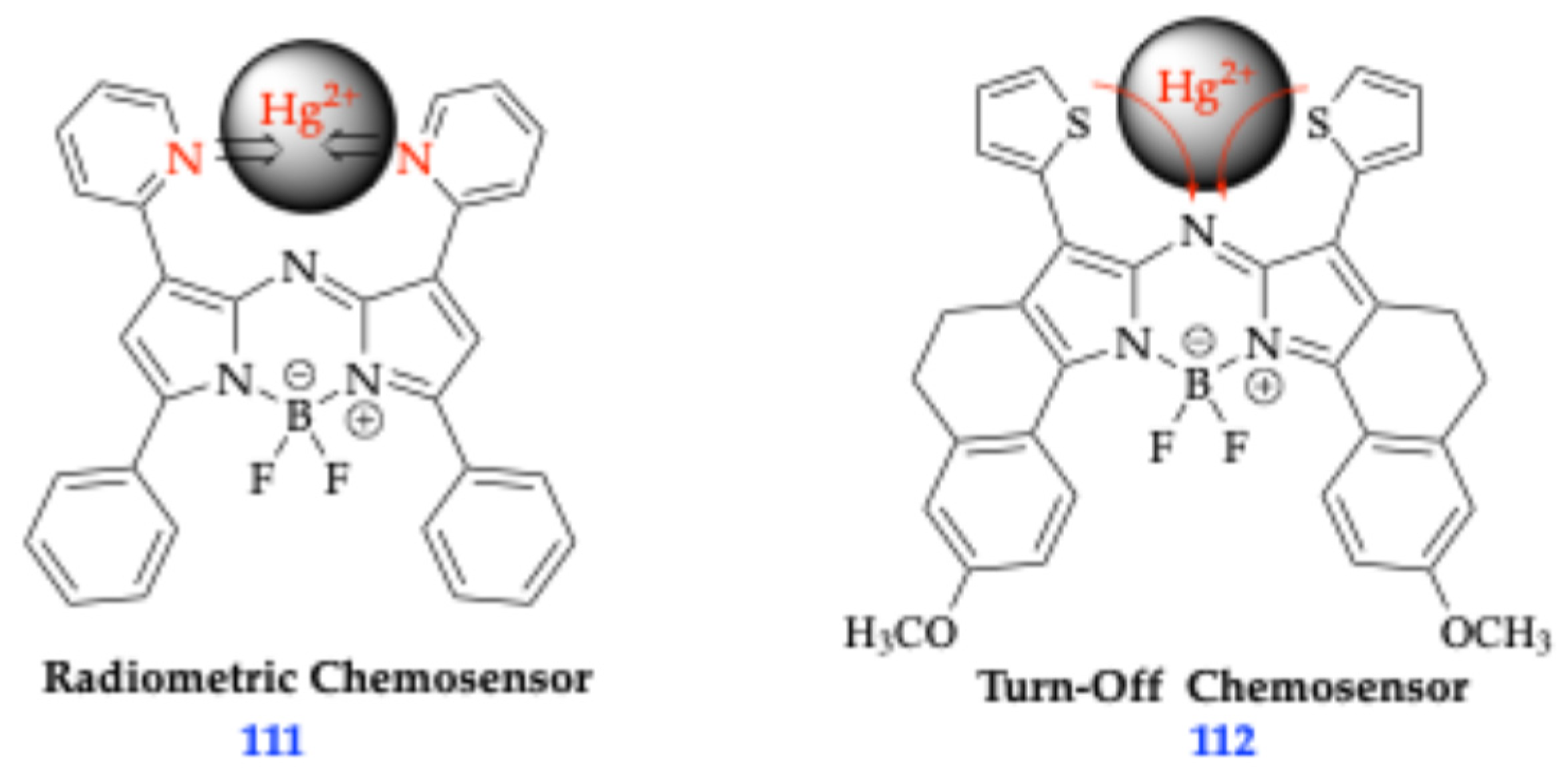

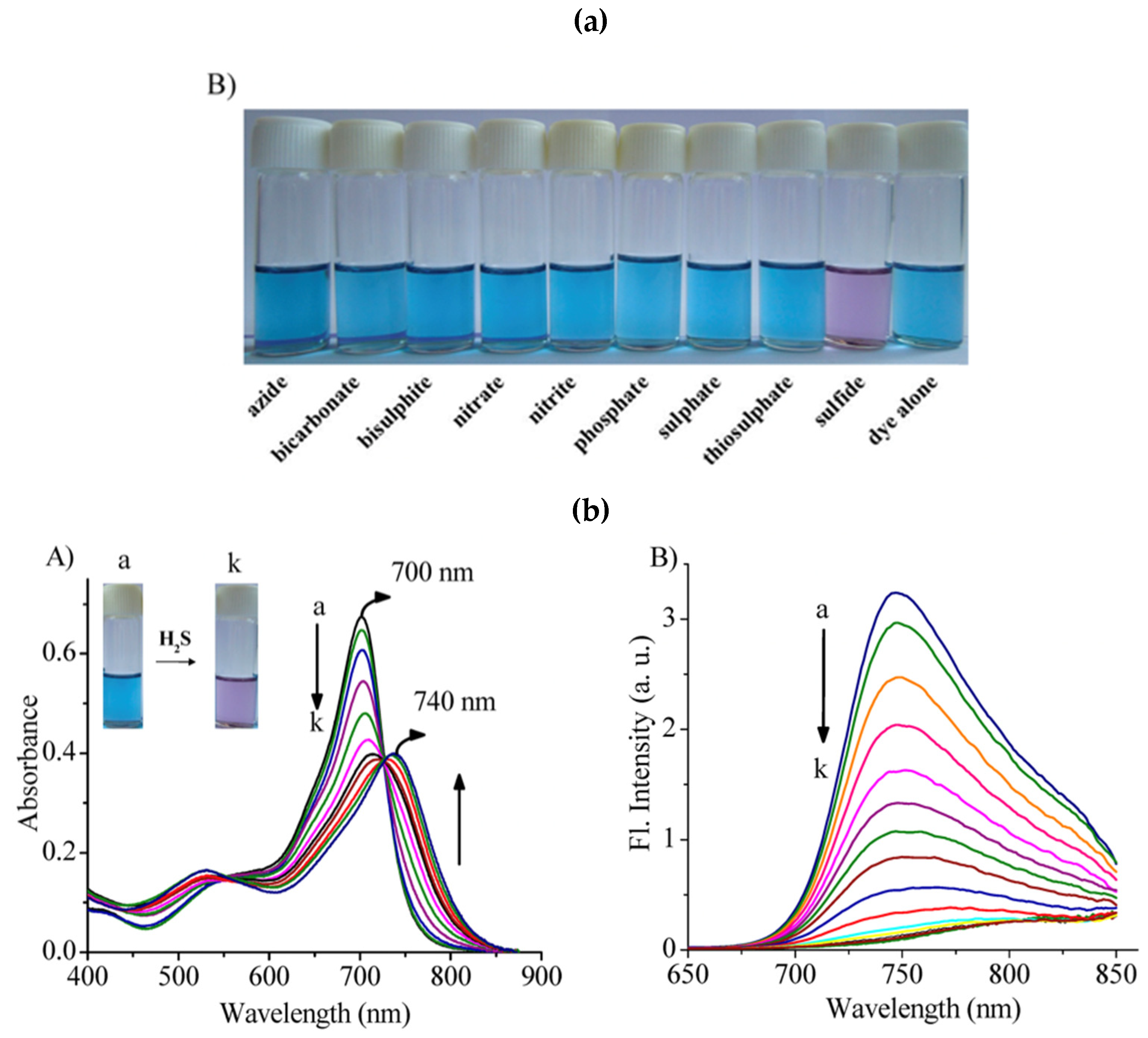

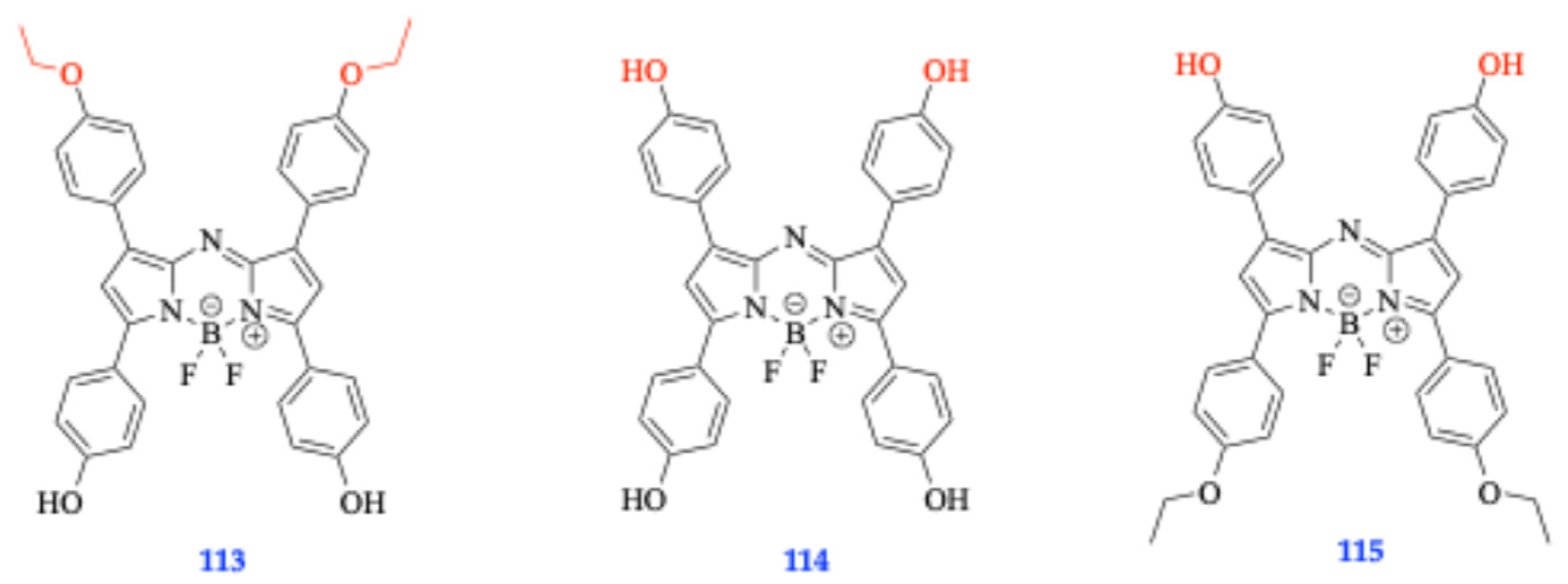

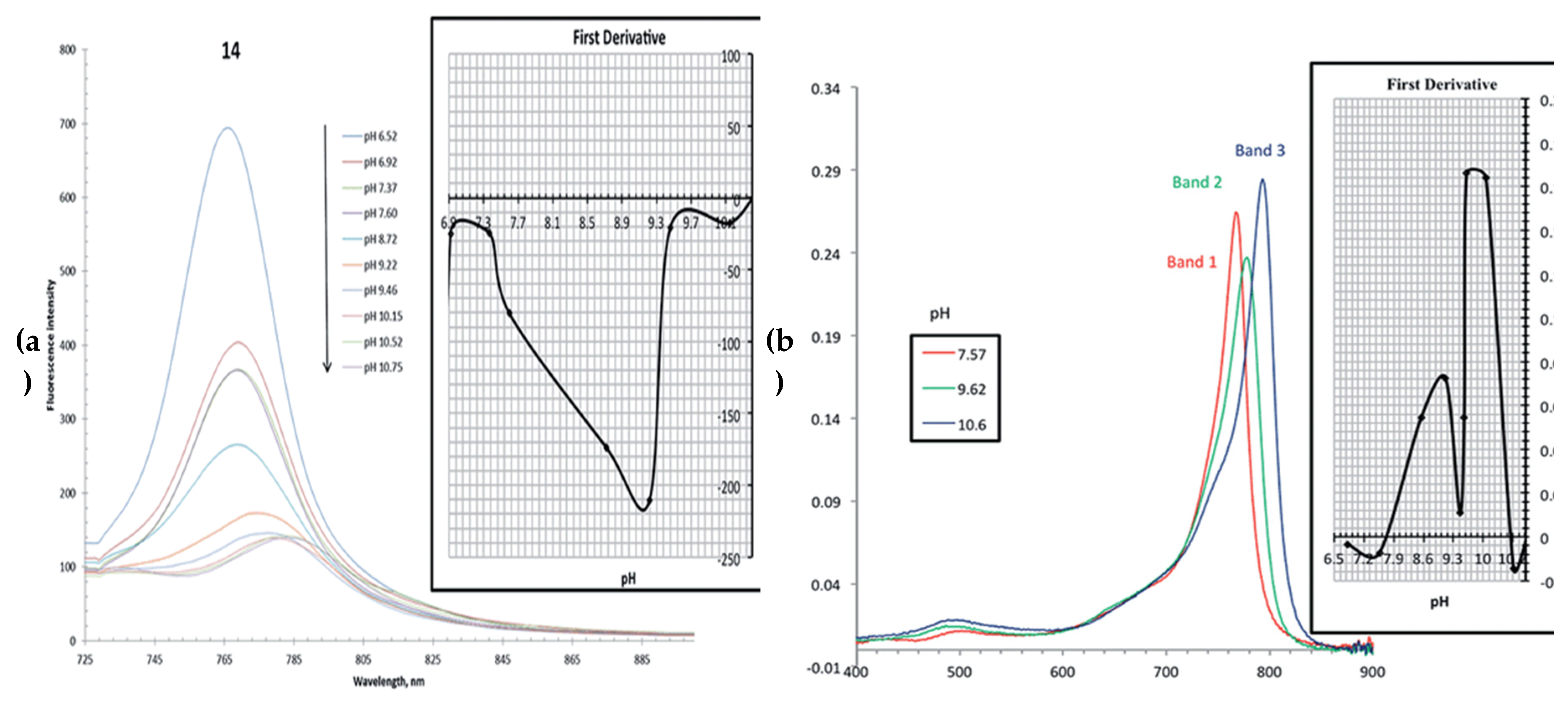

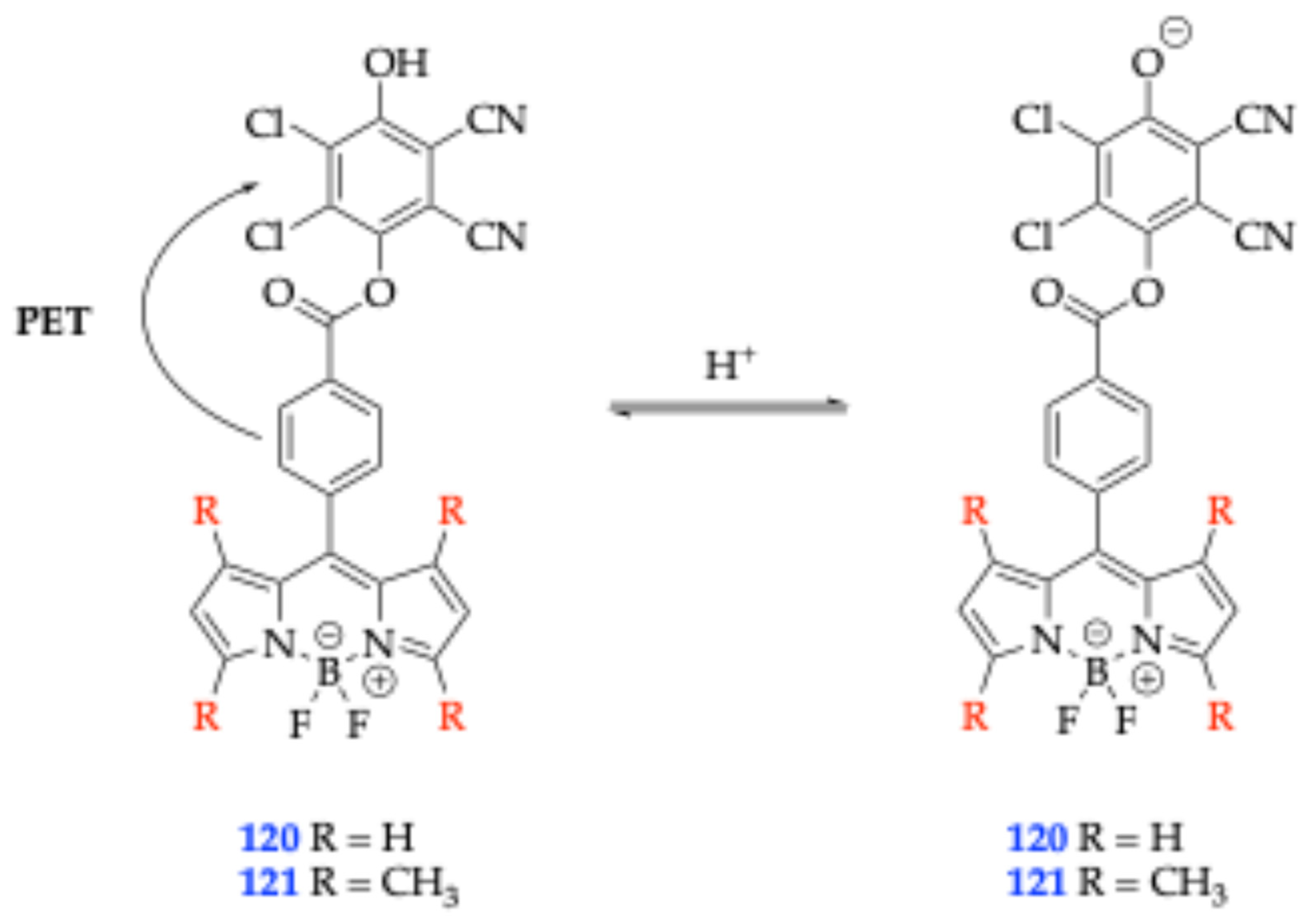

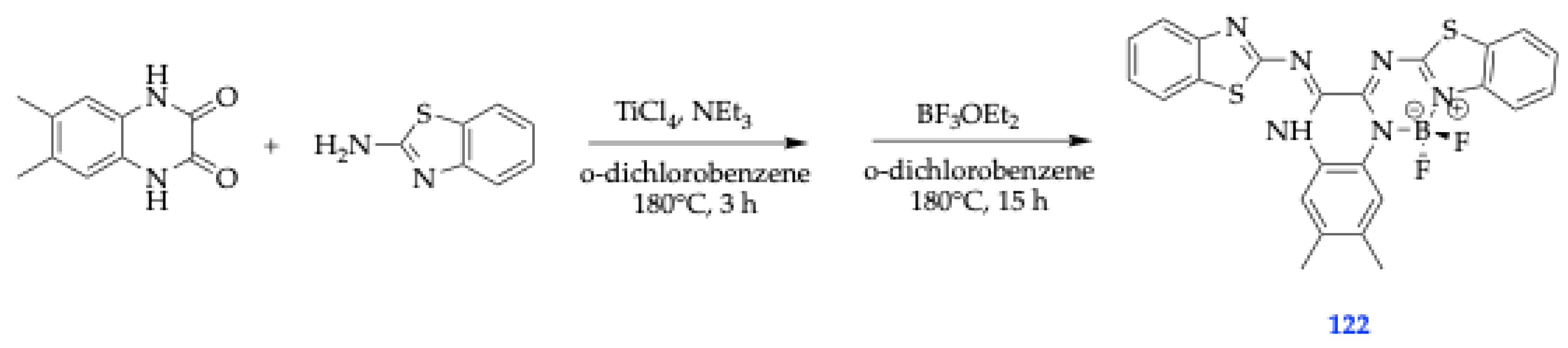

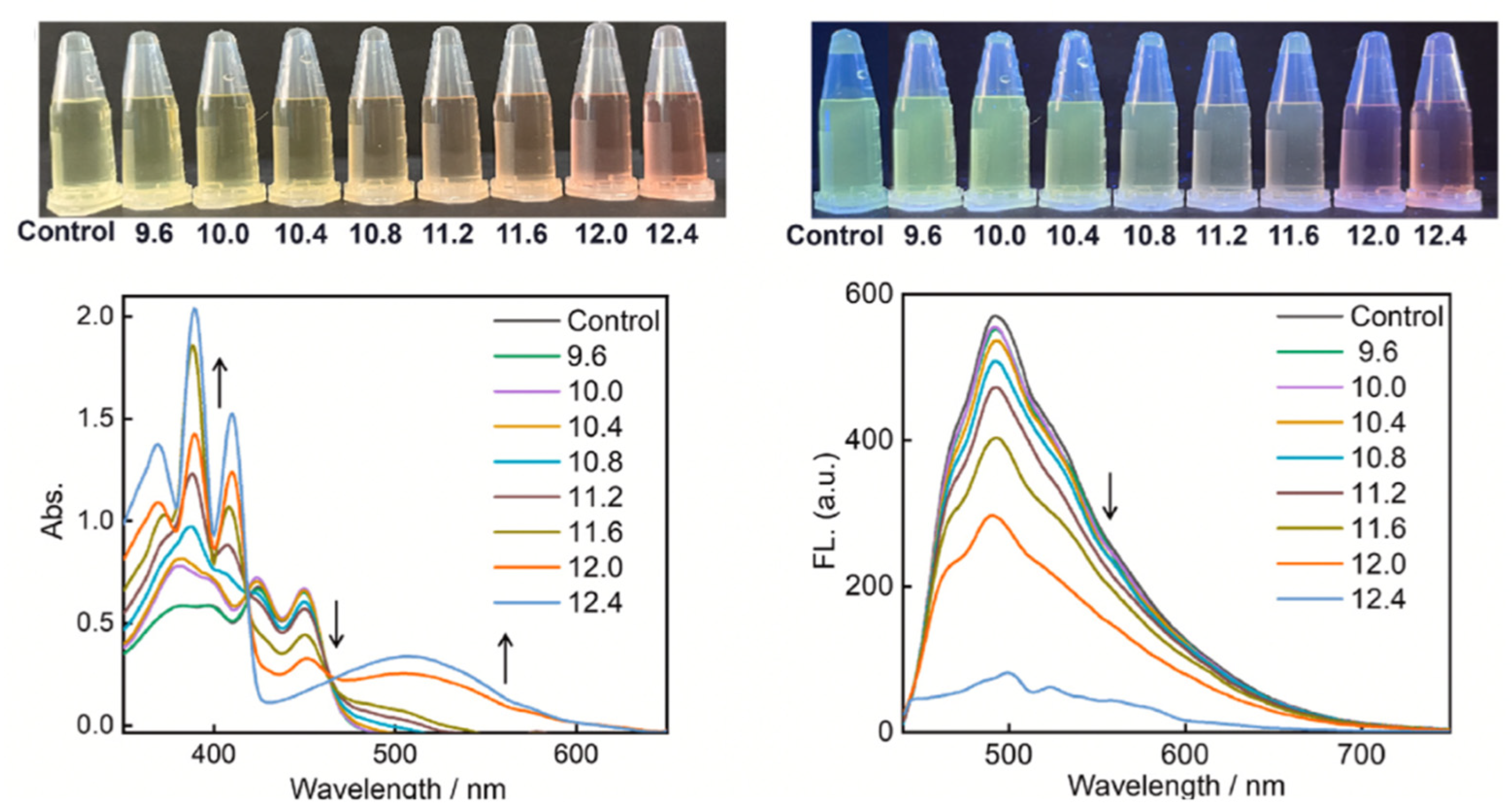

7.1. Metal-Sensing, pH Sensing, and Detection of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

| Compound | λabs [nm] |

log [ε] |

λem [nm] |

Φf% % [a] |

||

| 52 | 630 | 4.80 | 690 55.4 | |||

| 53 | 625 | 4.80 | 678 51.0 | |||

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AC2O | Acetic Anhydride |

| a-TOH | a-Tocopherol |

| AIE | Aggregation-Induced Emission |

| aPS | Activatable photosensitizers |

| Aza-BDPBA | Aza-Boronic Acid Functionalized |

| BODIPY | Boron-dipyrromethene |

| BuOH | Butanol |

| CT | Charge Transfer |

| CuAAC | Cu(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne Cycloaddition |

| Cys | Cysteine |

| DABCO | Triazabicyclo [2.2.2] octane |

| DCFH-DA | 2’,7’-Dichlorofluorescin Diacetate |

| DFT | Density-Functional Theory |

| DDQ | (2,3-Dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone) |

| DPBF | 1,3-Diphenylisobenzofuran |

| DPP | Diketopyrrolopyrrole |

| ECL | Electrochemiluminescence |

| EDG | Electron Donating Group |

| EWG | Electron Withdrawing Group |

| FE | Fluorescent Enhancement |

| FRET | Förster Resonance Energy Transfer |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| ISC | Intersystem Crossing |

| HOMO | Highest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital |

| Hcy | Homocysteine |

| ICT | Intramolecular Charge Transfer |

| LCMS | Laser Confocal Microscopy Scanning |

| LOD | Limit of Detection |

| LOQ | Limit of Quantification |

| LUMO | Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital |

| MO | Molecular Orbital |

| MCR | Multicomponent Reactions |

| NAC | N-acetylcysteine |

| NIR | Near Infrared Region |

| NIR-II | Near-Infrared Region Window II |

| NP | Nanoparticles |

| OL | Olive Oil |

| PA | Picric Acid |

| PAI | Photoacoustic Imaging |

| PALM | Photoactivated Localization Microscopy |

| PBA | Phenyl Boronic Acid |

| PEG-3 | Polyethylene Glycol |

| PDT | Photodynamic Therapy |

| PET | Positron Emission Tomography |

| PET | Photoinduced Electron Transfer |

| PM | Plasma Membrane |

| PPAB | Pyrrolopyrrole Aza-BODIPY |

| PS | Photosensitizers |

| PTPE3 NPs | Pyrrolopyrrole aza-BODIPY nanoparticles |

| RDX | Hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine |

| RNS | Reactive Nitrogen Species |

| ROSs | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RNSs | Reactive Nitrogen Species |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| TPP | Triphenylphosphonium |

| TPE | Tetraphenylethylene |

| TOH | Tocopherol |

| V-PDT | Vascular Photodynamic Therapy |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

References

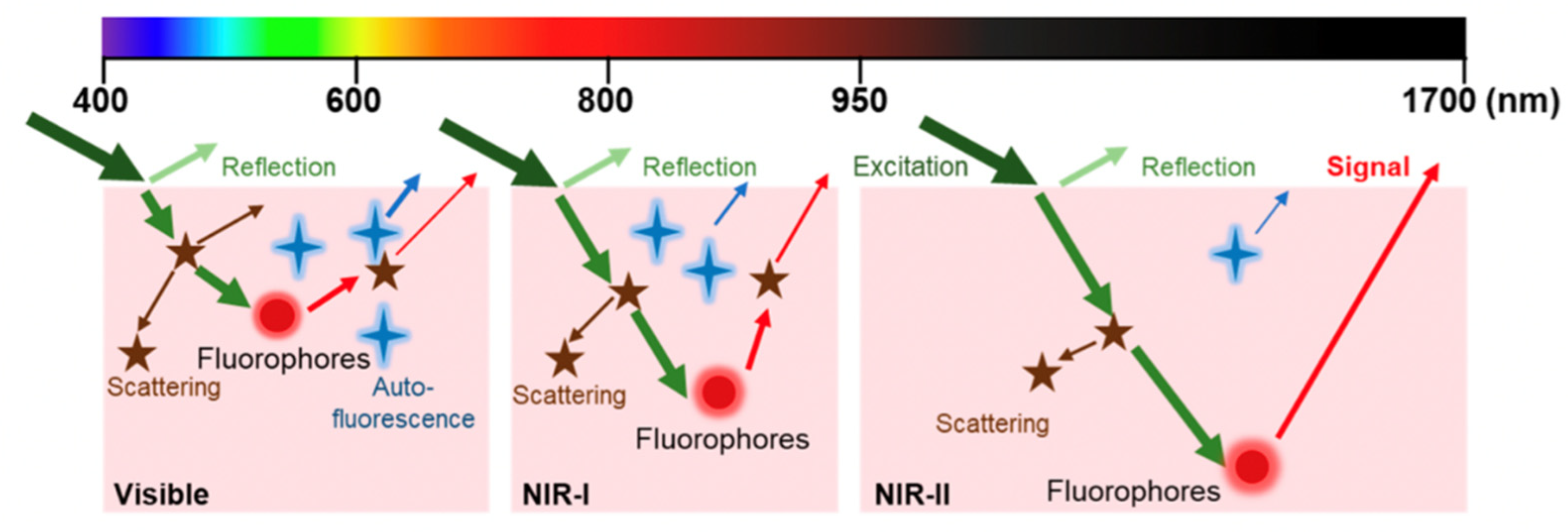

- Zhu, S.; Hu, Z.; Tian, R.; Yung, B.C.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, S.; Kiesewetter, D.O.; Niu, G.; Sun, H.; Antaris, A.L.; et al. Repurposing Cyanine NIR-I Dyes Accelerates Clinical Translation of Near-Infrared-II (NIR-II) Bioimaging. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1802546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, V.K.; Chakraborty, G.; Ray, A.K.; Nagaiyan, S. Red and NIR emitting ring-fused BODIPY/aza-BODIPY dyes. Dye. Pigment. 2023, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, A.; Wu, J.; Tang, X.; Zhao, L.; Xu, F.; Hu, Y. Application of Near-Infrared Dyes for Tumor Imaging, Photothermal, and Photodynamic Therapies. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 102, 6–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felbeck, T.; Hoffmann, K.; Lezhnina, M.M.; Kynast, U.H.; Resch-Genger, U. Fluorescent Nanoclays: Covalent Functionalization with Amine Reactive Dyes from Different Fluorophore Classes and Surface Group Quantification. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 12978–12987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuronuma, Y.; Watanabe, R.; Hiruta, Y. The latest developments of near-infrared fluorescent probes from NIR-I to NIR-II for bioimaging. Anal. Sci. 2025, 41, 737–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

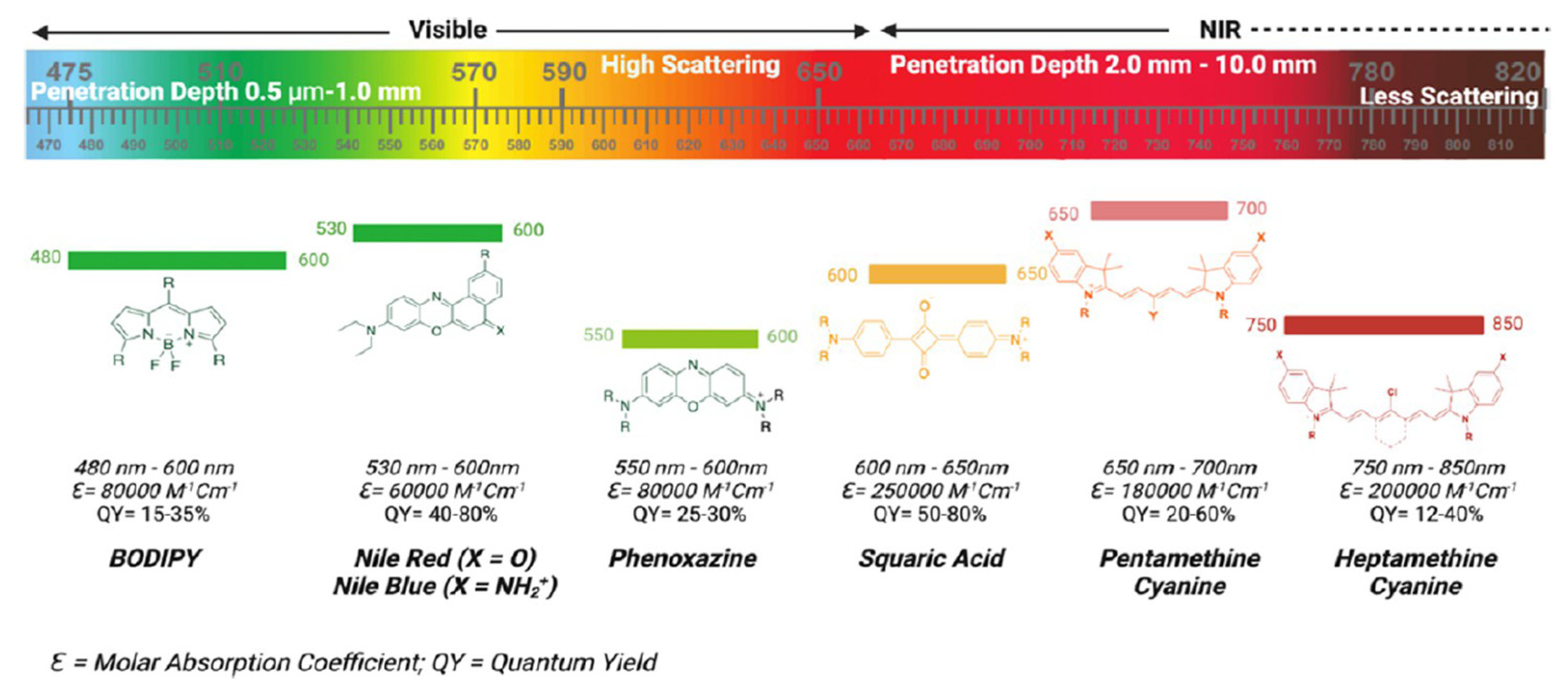

- Ersoy, G.; Henary, M. Roadmap for Designing Donor-π-Acceptor Fluorophores in UV-Vis and NIR Regions: Synthesis, Optical Properties and Applications. Biomolecules 2025, 15(1), 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasiya, S.; Sarasiya, S.; Henary, M. Exploration of NIR Squaraine Contrast Agents Containing Various Heterocycles: Synthesis, Optical Properties and Applications. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16(9), 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, P.; Singh, N.; Majumdar, P.; Singh, S.P. Evolution of BODIPY/aza-BODIPY dyes for organic photoredox/energy transfer catalysis. Co-ord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Fronczek, F.R.; Vicente, M.G.H.; Smith, K.M. Functionalization of 3,5,8-Trichlorinated BODIPY Dyes. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 10342–10352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bañuelos-Prieto, J.; Sola-Llano, R. Introductory Chapter: BODIPY Dye, an All-in-One Molecular Scaffold for (Bio)Photonics. In BODIPY Dyes - A Privilege Molecular Scaffold with Tunable Properties, Bañuelos-Prieto, J., Sola-Llano, R. Eds.; IntechOpen, 2018.

- Cao, J.; Zhu, B.; Zheng, K.; He, S.; Meng, L.; Song, J.; Yang, H. Recent Progress in NIR-II Contrast Agent for Biological Imaging. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2020, Volume 7 - 2019, Review. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, K.-H.; Tang, S.; Ravelo, L.; Cusido, J.; Sun, C.; Zhang, H.F.; Raymo, F.M. Far-Red Photoactivatable BODIPYs for the Super-Resolution Imaging of Live Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 12741–12745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Ji, P.; Sun, Q.; Gao, H.; Liu, Z. BODIPY-based small molecular probes for fluorescence and photoacoustic dual-modality imaging of superoxide anion in vivo. Talanta 2025, 294, 128269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

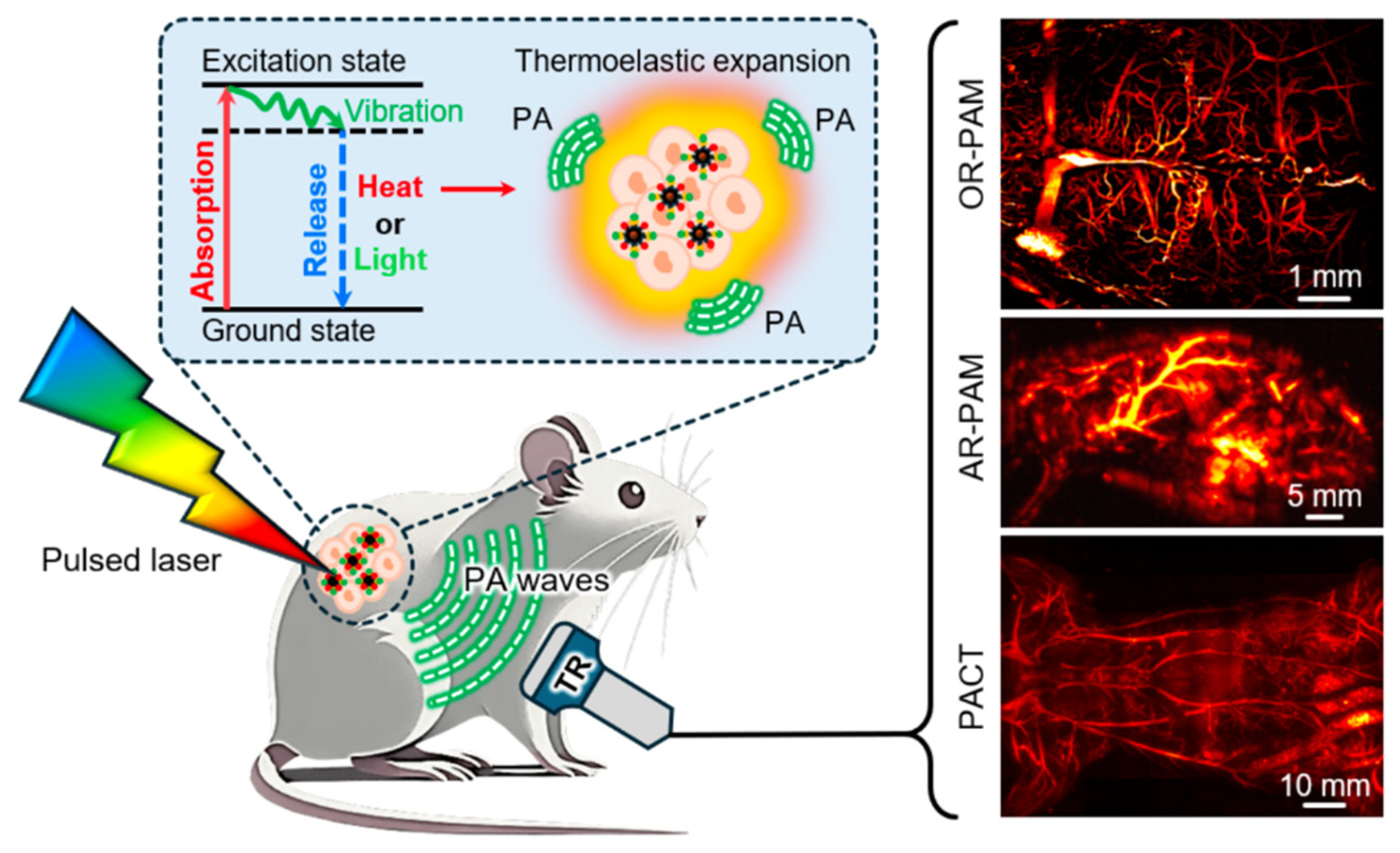

- Kye, H.; Jo, D.; Jeong, S.; Kim, C.; Kim, J. Photoacoustic Imaging of pH-Sensitive Optical Sensors in Biological Tissues. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Wang, F.; Li, Y.; Peng, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, L.; He, P.; Yu, T.; Chen, D.; Duan, M.; et al. Fluorination of Aza-BODIPY for Cancer Cell Plasma Membrane-Targeted Imaging and Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 3013–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, Y.; Chen, L.; Song, J.; Yang, H. Optical and Photoacoustic Imaging In Vivo: Opportunities and Challenges. Chem. Biomed. Imaging 2023, 1, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodio, E.; Goze, C. Investigation of B-F substitution on BODIPY and aza-BODIPY dyes: Development of B-O and B-C BODIPYs. Dye. Pigment. 2019, 160, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, P.; Chu, K.; Yan, N.; Ding, Z. Comparison study of electrochemiluminescence of boron-dipyrromethene (BODIPY) dyes in aprotic and aqueous solutions. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2016, 781, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, W.-J.; Wang, T.-T.; Chen, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, S. Synthesis and optical properties of tyramine-functionalized boron dipyrromethene dyes for cell bioimaging. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 324, 124980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.-D.; Xi, D.; Zhao, J.; Yu, H.; Sun, G.-T.; Xiao, L.-J. A styryl-containing aza-BODIPY as a near-infrared dye. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 60970–60973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boens, N.; Verbelen, B.; Ortiz, M.J.; Jiao, L.; Dehaen, W. Synthesis of BODIPY dyes through postfunctionalization of the boron dipyrromethene core. Co-ord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 399, 213024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loudet, A.; Burgess, K. BODIPY Dyes and Their Derivatives: Syntheses and Spectroscopic Properties. Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 4891–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wu, Y.; Ma, C.; Liu, W.; Zhang, C. Asymmetric anthracene-fused BODIPY dye with large Stokes shift: Synthesis, photophysical properties and bioimaging. Dye. Pigment. 2016, 126, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killoran, J.; McDonnell, S.O.; Gallagher, J.F.; O’sHea, D.F. A substituted BF2-chelated tetraarylazadipyrromethene as an intrinsic dual chemosensor in the 650–850 nm spectral range. New J. Chem. 2007, 32, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, M.L.H.; Vosch, T.; Laursen, B.W.; Hansen, T. Spectral shifts of BODIPY derivatives: a simple continuous model. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2019, 18, 1315–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Vicente, M.G.H.; Mason, D.; Bobadova-Parvanova, P. Stability of a Series of BODIPYs in Acidic Conditions: An Experimental and Computational Study into the Role of the Substituents at Boron. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 5502–5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybczynski, P.; Smolarkiewicz-Wyczachowski, A.; Piskorz, J.; Bocian, S.; Ziegler-Borowska, M.; Kędziera, D.; Kaczmarek-Kędziera, A. Photochemical Properties and Stability of BODIPY Dyes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, L.E.; Lincoln, R.; Krumova, K.; Cosa, G. Development of a Fluorogenic Reactivity Palette for the Study of Nucleophilic Addition Reactions Based on meso-Formyl BODIPY Dyes. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 8618–8624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Mack, J.; Yang, Y.; Shen, Z. Structural modification strategies for the rational design of red/NIR region BODIPYs. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 4778–4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Wu, Y.; Wang, S.; Hu, X.; Zhang, P.; Yu, C.; Cong, K.; Meng, Q.; Hao, E.; Vicente, M.G.H. Accessing Near-Infrared-Absorbing BF2-Azadipyrromethenes via a Push–Pull Effect. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 1830–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porolnik, W.; Koczorowski, T.; Wieczorek-Szweda, E.; Szczolko, W.; Falkowski, M.; Piskorz, J. Microwave-assisted synthesis, photochemical and electrochemical studies of long-wavelength BODIPY dyes. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 314, 124188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Han, X.; Hu, W.; Bai, H.; Peng, B.; Ji, L.; Fan, Q.; Li, L.; Huang, W. Bioapplications of small molecule Aza-BODIPY: from rational structural design toin vivoinvestigations. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 7533–7567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, V.; Ravikanth, M. Synthesis of novel fluorescent 3-pyrrolyl BODIPYs and their derivatives. Tetrahedron Chem 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yu, C.; Hao, E.; Jiao, L. Conformationally restricted and ring-fused aza-BODIPYs as promising near infrared absorbing and emitting dyes. Co-ord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donyagina, V.F.; Shimizu, S.; Kobayashi, N.; Lukyanets, E.A. Synthesis of N,N-difluoroboryl complexes of 3,3′-diarylazadiisoindolylmethenes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 6152–6154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Xiong, K.; Shang, R.; Jiang, X.-D. Near-infrared absorbing (>700 nm) aza-BODIPYs by freezing the rotation of the aryl groups. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2022, 33, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roohi, H.; Mohtamadifar, N. The role of the donor group and electron-accepting substitutions inserted in π-linkers in tuning the optoelectronic properties of D–π–A dye-sensitized solar cells: a DFT/TDDFT study. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 11557–11573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fron, E.; Coutiño-Gonzalez, E.; Pandey, L.; Sliwa, M.; Van der Auweraer, M.; De Schryver, F.C.; Thomas, J.; Dong, Z.; Leen, V.; Smet, M.; et al. Synthesis and photophysical characterization of chalcogen substituted BODIPY dyes. New J. Chem. 2009, 33, 1490–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomazzo, G.E.; Palladino, P.; Gellini, C.; Salerno, G.; Baldoneschi, V.; Feis, A.; Scarano, S.; Minunni, M.; Richichi, B. A straightforward synthesis of phenyl boronic acid (PBA) containing BODIPY dyes: new functional and modular fluorescent tools for the tethering of the glycan domain of antibodies. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 30773–30777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardon, K.M.; Selfridge, S.; Adams, D.S.; Minns, R.A.; Pawle, R.; Adams, T.C.; Takiff, L. Synthesis of Water-Soluble Far-Red-Emitting Amphiphilic BODIPY Dyes. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 13195–13199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonnelé, C. Chemical Sensors: Modelling the Photophysics of Cation Detection by Organic Dyes. 2013.

- Nguyen, Y.T.; Shin, S.; Kwon, K.; Kim, N.; Bae, S.W. BODIPY-based fluorescent sensors for detection of explosives. J. Chem. Res. 2023, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprenger, T.; Schwarze, T.; Müller, H.; Sperlich, E.; Kelling, A.; Holdt, H.; Paul, J.; Riaño, V.M.; Nazaré, M. BODIPY-Equipped Benzo-Crown-Ethers as Fluorescent Sensors for pH Independent Detection of Sodium and Potassium Ions. ChemPhotoChem 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

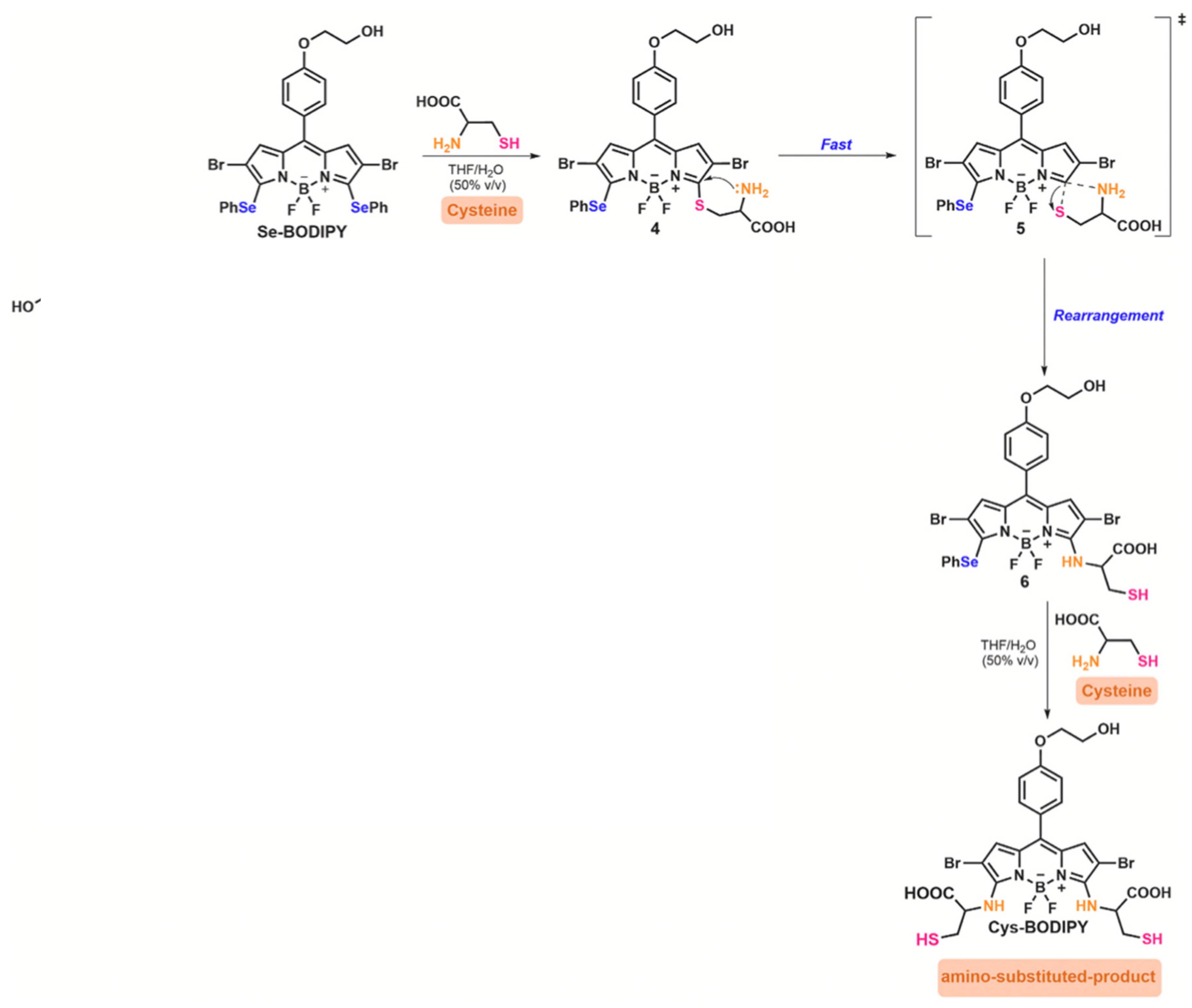

- Cugnasca, B.S.; Junior, T.C.; Penna, T.C.; Zuluaga, N.L.; Bustos, S.O.; Chammas, R.; Cuccovia, I.M.; Correra, T.C.; Dos Santos, A.A. Seleno-BODIPY as a fluorescent sensor for differential and highly selective detection of Cysteine and Glutathione for bioimaging in HeLa cells. Dye. Pigment. 2025, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

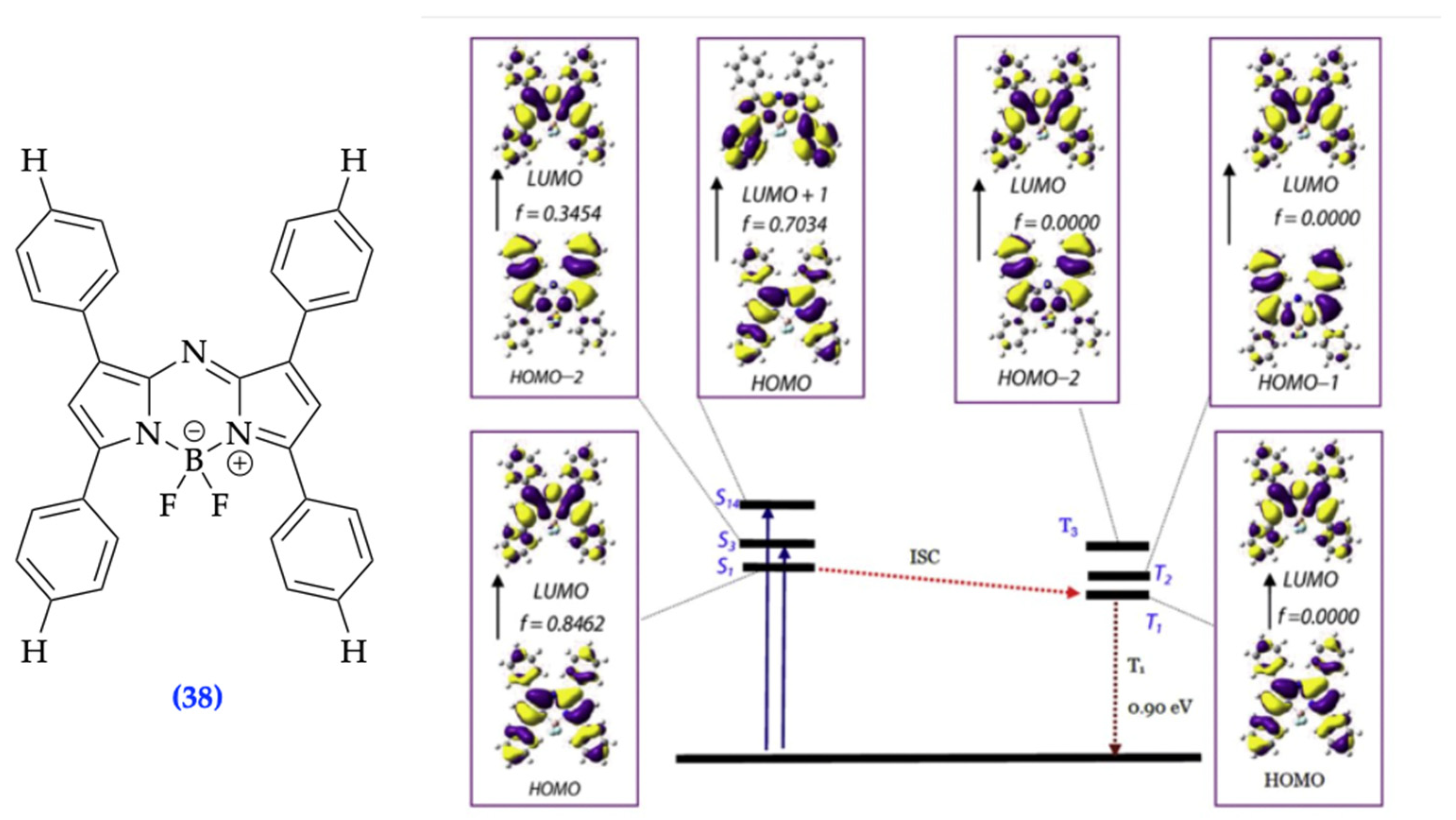

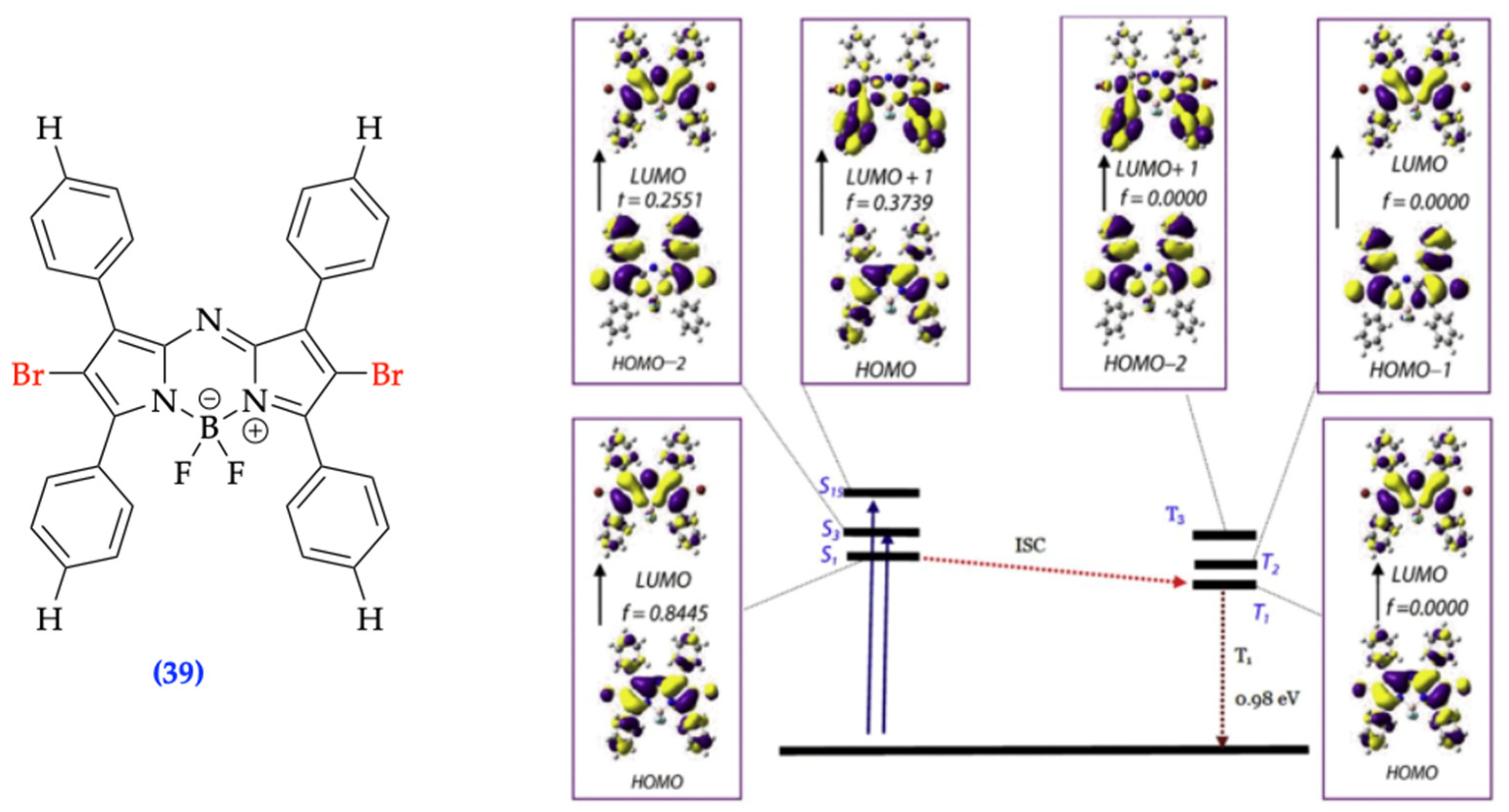

- Karatay, A.; Miser, M.C.; Cui, X.; Küçüköz, B.; Yılmaz, H.; Sevinç, G.; Akhüseyin, E.; Wu, X.; Hayvali, M.; Yaglioglu, H.G.; et al. The effect of heavy atom to two photon absorption properties and intersystem crossing mechanism in aza-boron-dipyrromethene compounds. Dye. Pigment. 2015, 122, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

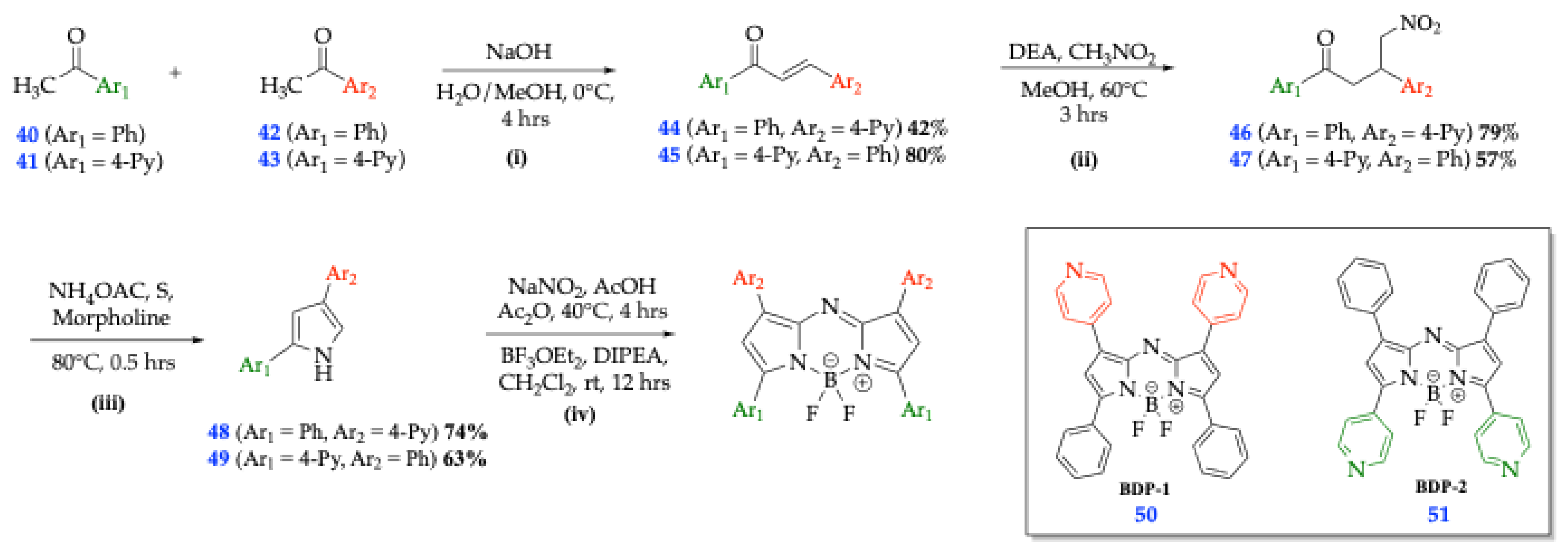

- Liu, Y.-C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, G.-J.; Xing, G.-W. J- and H-aggregates of heavy-atom-free Aza-BODIPY dyes with high 1O2 generation efficiency and photodynamic therapy potential. Dye. Pigment. 2022, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klymchenko, A. Emerging field of self-assembled fluorescent organic dye nanoparticles. Journal of Nanoscience Letters 2013, 3, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, H.S.; Gibbs, S.L.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Ashitate, Y.; Liu, F.; Hyun, H.; Park, G.; Xie, Y.; Bae, S.; et al. Targeted zwitterionic near-infrared fluorophores for improved optical imaging. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.S.; Nasr, K.; Alyabyev, S.; Feith, D.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Ashitate, Y.; Hyun, H.; Patonay, G.; Strekowski, L.; et al. Synthesis and In Vivo Fate of Zwitterionic Near-Infrared Fluorophores. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011, 50, 6258–6263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adarsh, N.; Babu, P.S.S.; Avirah, R.R.; Viji, M.; Nair, S.A.; Ramaiah, D. Aza-BODIPY nanomicelles as versatile agents for the in vitro and in vivo singlet oxygen-triggered apoptosis of human breast cancer cells. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 2372–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavaš, M.; Zlatić, K.; Jadreško, D.; Ljubić, I.; Basarić, N. Fluorescent pH sensors based on BODIPY structure sensitive in acidic media. Dye. Pigment. 2023, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killoran, J.; Allen, L.; Gallagher, J.F.; Gallagher, W.M.; O′Shea, D.F. Synthesis of BF2chelates of tetraarylazadipyrromethenes and evidence for their photodynamic therapeutic behaviour. Chem. Commun. 2002, 1862–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbelen, B.; Leen, V.; Wang, L.; Boens, N.; Dehaen, W. Direct palladium-catalysed C–H arylation of BODIPY dyes at the 3- and 3,5-positions. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 9129–9131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, H. Y.; Fu, X.; Liu, B.; Chao, X.; Chan, C. L.; Cao, H.; Su, T.; Tse, A. K. W.; Fong, W. F.; Yu, Z. L. Subcutaneous adipocytes promote melanoma cell growth by activating the Akt signaling pathway: role of palmitic acid. J Biol Chem 2014, 289(44), 30525–30537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikata, T.; Abela, A.R.; Huang, S.; Lipshutz, B.H. Cationic Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H activation/cross-coupling reactions at room temperature: synthetic and mechanistic studies. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 1040–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendive-Tapia, L.; Zhao, C.; Akram, A.R.; Preciado, S.; Albericio, F.; Lee, M.; Serrels, A.; Kielland, N.; Read, N.D.; Lavilla, R.; et al. Spacer-free BODIPY fluorogens in antimicrobial peptides for direct imaging of fungal infection in human tissue. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moliner, F.; Kielland, N.; Lavilla, R.; Vendrell, M. Modern Synthetic Avenues for the Preparation of Functional Fluorophores. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017, 56, 3758–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, T.; Sun, C.; Meng, Y.; Xiao, L. Synthesis of aza-BODIPY dyes bearing the naphthyl groups at 1,7-positions and application for singlet oxygen generation. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2019, 30, 1055–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

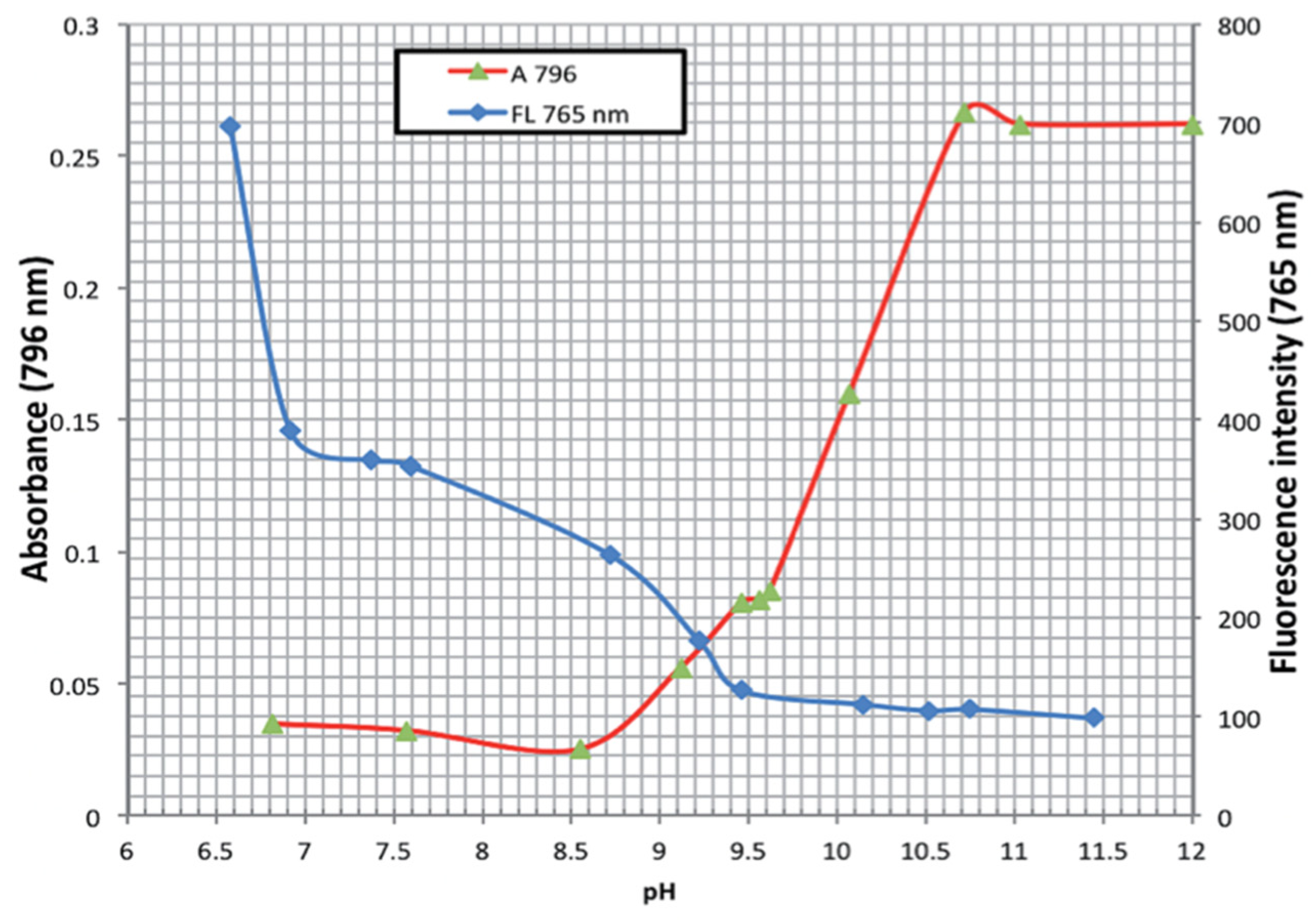

- Staudinger, C.; Breininger, J.; Klimant, I.; Borisov, S.M. Near-infrared fluorescent aza-BODIPY dyes for sensing and imaging of pH from the neutral to highly alkaline range. Anal. 2019, 144, 2393–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D.; Nair, R.R.; Mangalath, S.; Nair, S.A.; Joseph, J.; Gogoi, P.; Ramaiah, D. Biocompatible Aza-BODIPY-Biotin Conjugates for Photodynamic Therapy of Cancer. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 26180–26190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Daddario, C.; Pejić, S.; Sauvé, G. Synthesis and Properties of Azadipyrromethene-Based Complexes with Nitrile Substitution. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 2020, 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-Z.; Lin, H.-L.; Li, H.-Y.; Cao, H.-W.; Lang, X.-X.; Chen, Y.-S.; Chen, H.-W.; Wang, M.-Q. Red-emitting Styryl-BODIPY dye with donor-π-acceptor architecture: Selective interaction with serum albumin via disaggregation-induced emission. Dye. Pigment. 2023, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Li, H.; Tian, Y.; Niu, L.-Y. Novel phenothiazine-based amphiphilic Aza-BODIPYs for high-efficient photothermal therapy. Dye. Pigment. 2023, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

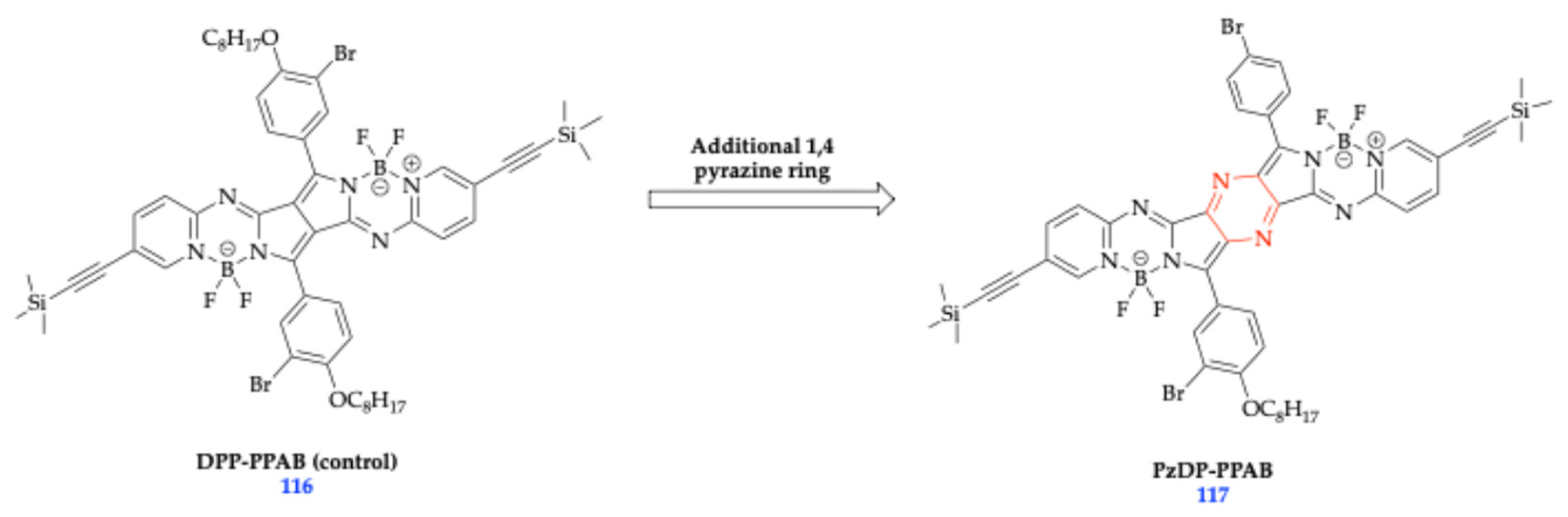

- Bian, S.; Zheng, X.; Liu, W.; Li, J.; Gao, Z.; Ren, H.; Zhang, W.; Lee, C.-S.; Wang, P. Pyrrolopyrrole aza-BODIPY-based NIR-II fluorophores for in vivo dynamic vascular dysfunction visualization of vascular-targeted photodynamic therapy. Biomaterials 2023, 298, 122130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhou, H.; Cheng, Q.; Dang, H.; Qian, H.; Teng, C.; Xie, K.; Yan, L. Stable twisted conformation aza-BODIPY NIR-II fluorescent nanoparticles with ultra-large Stokes shift for imaging-guided phototherapy. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 10, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, S.; Xiong, H. Modular Design of High-Brightness pH-Activatable Near-Infrared BODIPY Probes for Noninvasive Fluorescence Detection of Deep-Seated Early Breast Cancer Bone Metastasis: Remarkable Axial Substituent Effect on Performance. ACS Central Sci. 2021, 7, 2039–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Jiao, J.; Xu, W.; Zhang, M.; Cui, P.; Guo, Z.; Deng, Y.; Chen, H.; Sun, W. Highly Efficient Far-Red/NIR-Absorbing Neutral Ir(III) Complex Micelles for Potent Photodynamic/Photothermal Therapy. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2100795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgun, T.; Yurttas, A.G.; Cinar, K.; Ozcelik, S.; Gul, A. Effect of aza-BODIPY-photodynamic therapy on the expression of carcinoma-associated genes and cell death mode. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2023, 44, 103849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlogyik, T.; Laczkó-Rigó, R.; Bakos, É.; Poór, M.; Kele, Z.; Özvegy-Laczka, C.; Mernyák, E. Synthesis and in vitro photodynamic activity of aza-BODIPY-based photosensitizers. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 6018–6027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samanta, S.; Lai, K.; Wu, F.; Liu, Y.; Cai, S.; Yang, X.; Qu, J.; Yang, Z. Xanthene, cyanine, oxazine and BODIPY: the four pillars of the fluorophore empire for super-resolution bioimaging. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 7197–7261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tang, S.; Ravelo, L.; Cusido, J.; Raymo, F. M. Chapter Six - Far-red photoactivatable BODIPYs for the super-resolution imaging of live cells. In Methods in Enzymology, Chenoweth, D. M. Ed.; Vol. 640; Academic Press, 2020; pp 131-147.

- Gai, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Lu, H.; Guo, Z. BODIPY-based probes for hypoxic environments. Co-ord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlogyik, T.; Laczkó-Rigó, R.; Bakos, É.; Poór, M.; Kele, Z.; Özvegy-Laczka, C.; Mernyák, E. Synthesis and in vitro photodynamic activity of aza-BODIPY-based photosensitizers. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2023, 21, 6018–6027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aranda, A.; Sequedo, L.; Tolosa, L.; Quintas, G.; Burello, E.; Castell, J.; Gombau, L. Dichloro-dihydro-fluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) assay: A quantitative method for oxidative stress assessment of nanoparticle-treated cells. Toxicol. Vitr. 2013, 27, 954–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, G.; Kaufman, N.E.M.; Bobadova-Parvanova, P.; Fronczek, F.R.; Smith, K.M.; Vicente, M.d.G.H. Linker-Free Near-IR Aza-BODIPY-Glutamine Conjugates Through Boron Functionalization. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 2020, 971–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, J.F.; Liu, T.W.B.; Chen, J.; Zheng, G. Activatable Photosensitizers for Imaging and Therapy. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2839–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luangphai, S.; Thuptimdang, P.; Buddhiranon, S.; Chanawanno, K. Aza-BODIPY-based logic gate chemosensors and their applications. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 322, 124806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascal, S.; Bellier, Q.; David, S.; Bouit, P.-A.; Chi, S.-H.; Makarov, N.S.; Le Guennic, B.; Chibani, S.; Berginc, G.; Feneyrou, P.; et al. Unraveling the Two-Photon and Excited-State Absorptions of Aza-BODIPY Dyes for Optical Power Limiting in the SWIR Band. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 23661–23673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

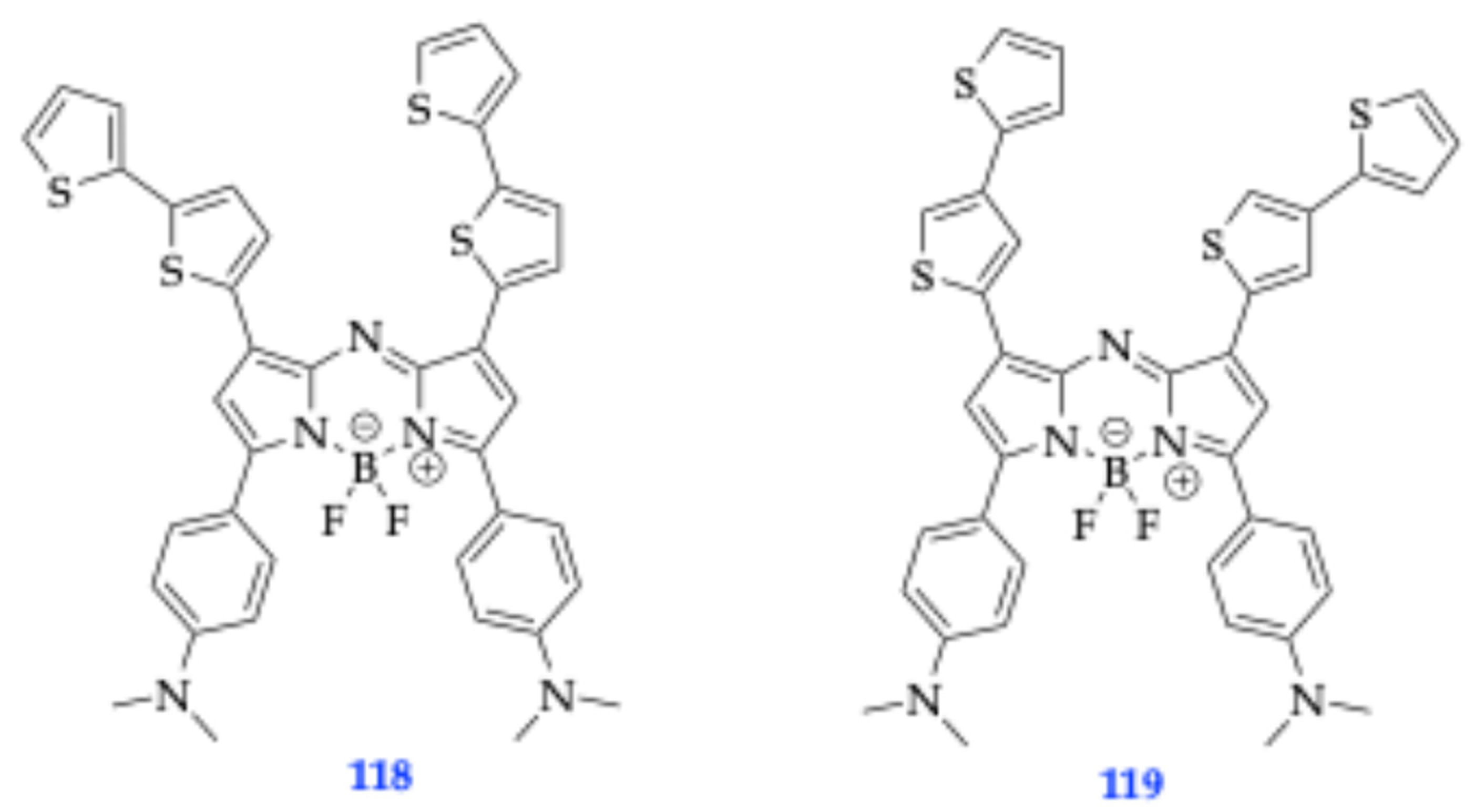

- Jiang, X.-D.; Zhao, J.; Li, Q.; Sun, C.-L.; Guan, J.; Sun, G.-T.; Xiao, L.-J. Synthesis of NIR fluorescent thienyl-containing aza-BODIPY and its application for detection of Hg2+: Electron transfer by bonding with Hg2+. Dye. Pigment. 2016, 125, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Sun, J.; Tang, F.; Xie, R.; Wang, H.; Ding, A.; Pan, S.; Li, L. Mitochondria-Targeting BODIPY Probes for Imaging of Reactive Oxygen Species. Adv. Sens. Res. 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adarsh, N.; Krishnan, M.S.; Ramaiah, D. Sensitive Naked Eye Detection of Hydrogen Sulfide and Nitric Oxide by Aza-BODIPY Dyes in Aqueous Medium. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 9335–9342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkushev, D.; Vodyanova, O.; Telegin, F.; Melnikov, P.; Yashtulov, N.; Marfin, Y. Design of Promising aza-BODIPYs for Bioimaging and Sensing. Designs 2022, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, M.M.; Owens, E.A.; Gao, T.; Lee, J.H.; Hyun, H.; Choi, H.S.; Henary, M. Hydroxylated near-infrared BODIPY fluorophores as intracellular pH sensors. Anal. 2014, 139, 4862–4873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

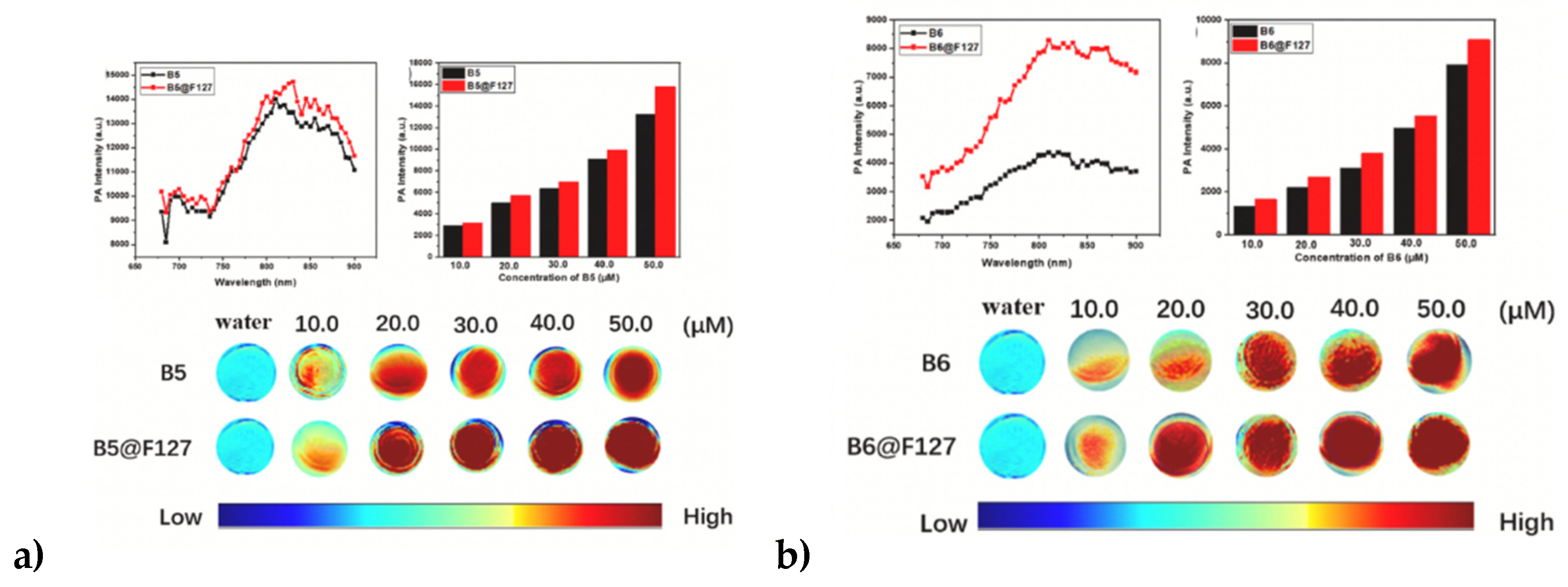

- Yadav AK, Tapia Hernandez R, Chan J. A general strategy to optimize the performance of aza-BODIPY-based probes for enhanced photoacoustic properties. Methods Enzymol. 2021;657:415-441. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2021.06.022. Epub 2021 Jul 21. PMID: 34353497.

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Xu, Y.; Qin, Y.; Jiang, D. Boronic Acid Functionalized Aza-Bodipy (azaBDPBA) based Fluorescence Optodes for the Analysis of Glucose in Whole Blood. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 11141–11145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Hou, S.; Bae, C.; Pham, T.C.; Lee, S.; Zhou, X. Aza-BODIPY based probe for photoacoustic imaging of ONOO− in vivo. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2021, 32, 3886–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, E.R.H.; Lee, L.C.-C.; Leung, P.K.-K.; Lo, K.K.-W.; Long, N.J. Mitochondria-targeting biocompatible fluorescent BODIPY probes. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 4846–4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamim, M.; Dinh, J.; Yang, C.; Nomura, S.; Kashiwagi, S.; Kang, H.; Choi, H.S.; Henary, M. Synthesis, Optical Properties, and In Vivo Biodistribution Performance of Polymethine Cyanine Fluorophores. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2023, 6, 1192–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

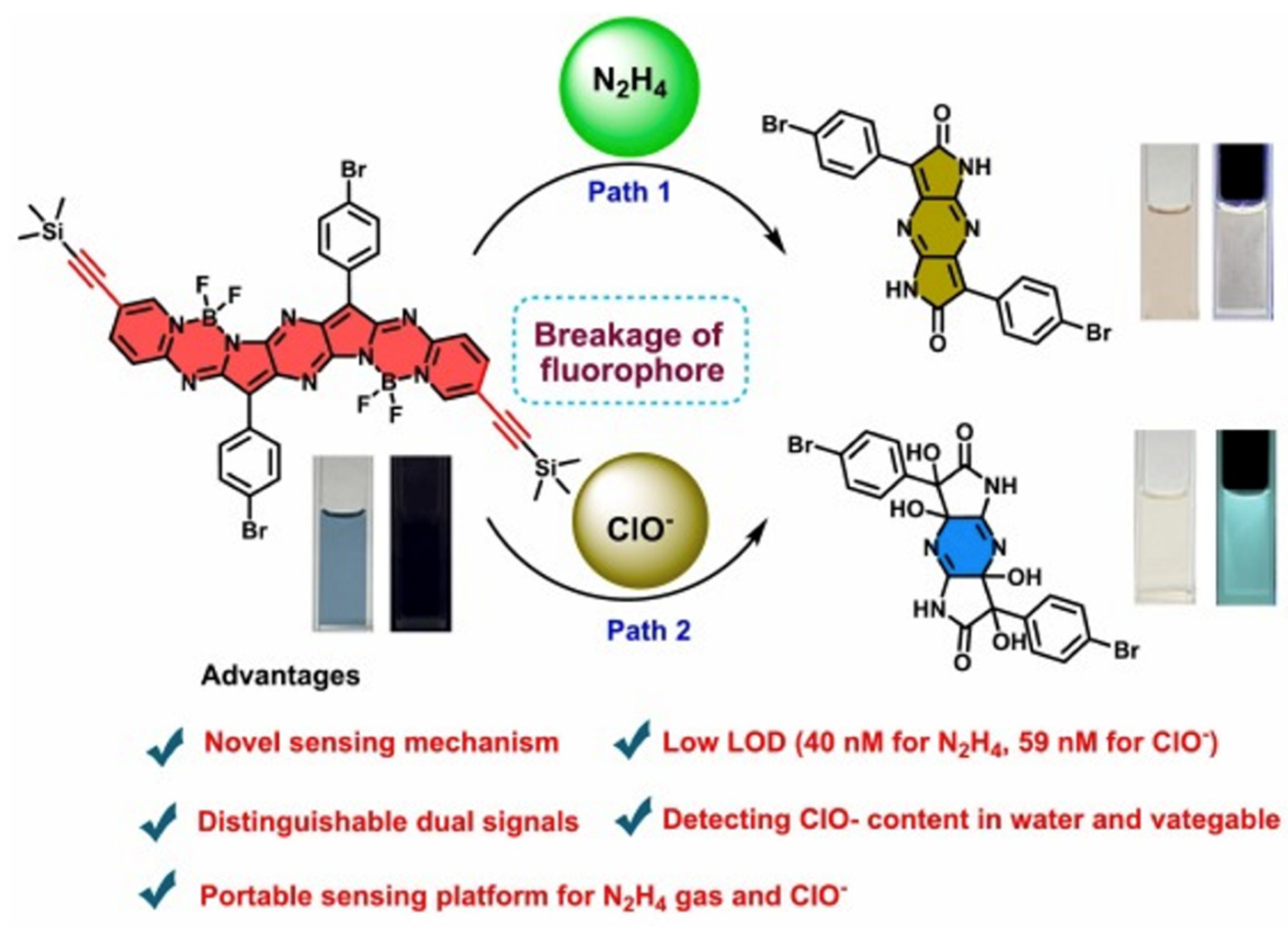

- Zhang, Y.; Gan, Y.; Lai, B.; Ran, X.; Cao, D.; Wang, L. A portable sensing platform using a novel dipyrrolopyrazinedione-based aza-BODIPY dimer for highly efficient detection of hypochlorite and hydrazine. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 341, 126415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizi-Khereshki, N.; Mousavi, H.Z.; Farsadrooh, M.; Evazalipour, M.; Feizi-Dehnayebi, M.; Ziarani, G.M.; Henary, M.; Rtimi, S.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles for colorimetric detection of Fe3+ in environmental samples: DFT calculations and molecular docking studies. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 387, 125880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, T.E.; Henary, M. Dimerizing Heptamethine Cyanine Fluorophores from the Meso Position: Synthesis, Optical Properties, and Metal Sensing Studies. Org. Lett. 2025, 27, 6623–6629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, Z.; Wen, B.; Dou, Q.; Guo, H.; Hu, C.; Bi, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, J.; Lin, Y.; Wang, J.; et al. Design, synthesis, and characterization of pH-responsive near infrared bithiophene Aza-BODIPY. Dye. Pigment. 2023, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavaš, M.; Zlatić, K.; Jadreško, D.; Ljubić, I.; Basarić, N. Fluorescent pH sensors based on BODIPY structure sensitive in acidic media. Dye. Pigment. 2023, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Shimizu, S.; Ji, S.; Pan, J.; Wang, Y.; Feng, R. A novel BODIPY-based fluorescent probe for naked-eye detection of the highly alkaline pH. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2024, 325, 125083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Reported Yield | Representative Compounds | Forms: Asymmetrical or Symmetrical Fluorophores? | |

| O’Shea’s | 20-50% [34] | Tetraphenyl Aza-BODIPY Dimethylamino Aza-BODIPY |

Both | |

| Carriera’s | 60-90% [34] | Cyclized 2,4-diaryl pyrroles complexed with BF3OEt2 | Both | |

| Lukyanet’s | 10-30% [34] | Phthalonitrile and aryl Grignard reagents complexed with BF3OEt2 | Symmetrical Only | |

| |||||||||

| Compound |

λabs [nm] |

λem [nm] |

Φf [a] | FEF [b] |

Kd [c] [mM] |

||||

| 31 | 498 | 506 | 0.072 | ------- | ------- | ||||

| 31+ 100 mM Na+ | 498 | 507 | 0.073 | 1.0 | ---- [d] | ||||

| 31+ 100 mM K+ | 498 | 507 | 0.072 | 1.0 | ---- [d] | ||||

| 31+ 100 mM Li+ | 498 | 507 | 0.072 | 1.0 | ---- [d] | ||||

| 32 | 498 | 507 | 0.008 | ------- | ------- | ||||

| 32 + 1000 mM Na+ | 498 | 507 | 0.056 | 7.3 | 276 | ||||

| 32 + 1000 mM K+ | 498 | 507 | 0.023 | 2.8 | 342 | ||||

| 33 | 498 | 507 | 0.008 | ------- | ------- | ||||

| 33 + 250 mM Na+ | 498 | 507 | 0.013 | 1.8 | 65 | ||||

| 33 + 250 mM K+ | 498 | 508 | 0.035 | 4.7 | 18 | ||||

| Entry | Compound | Ar | Reaction Time | Yield (%) of 54 | Yield (%) of 55 | ||||

| 1 | A | Phenyl a | 24 h | 44 | 17 | ||||

| 2 | B | 4-Anisyl | 43 h | 42 | 10 | ||||

| 3 | C | 4-(Dimethylamino)-phenyl | 48 h | --- | --- | ||||

| 4 | D | 3-Thienyl a | 27 h | 55 | 10 | ||||

| 5 | E | Mesityl | 43 h | 35 | 0 | ||||

| 6 | F | 1-Naphthyl | 24 h | 20 | 16 | ||||

| 7 | G | 4-Cyanophenyl | 48 h | --- | --- | ||||

| 8 | H | 3-Nitrophenyl | 48 h | --- | --- | ||||

| 9 | I | Phenyl a | 28 h | 31 | 32 | ||||

| 10 | J | Phenyl | 46 h | 28 | 18 | ||||

| 11 | K | Phenyl | 4 days | 13 | 43 | ||||

| 12 | L | Phenyl | 4 days | --- | 39 | ||||

| 13 | M | Phenyl b | 3 h | 39 | 40 | ||||

| 14 | N | 3-Thienyl b | 3 h | 26 | --- | ||||

| 15 | O | Phenyl b | 3.5 h | 28 | 46 | ||||

| Sensitizer |

λabs nm (ε, M-1 cm-1) |

λem nm | Fluorescence QY, Φf | Triplet QY ΦT | Singlet Oxygen Generation QY Φ (1O2) | ||

| DPR1a [60] | 660 (106,500) | 698 | 0.200 | ND | ND | ||

| DPR1b [60] | 684 (80,000) | 721 | 0.300 | ND | ND | ||

| DPR2a [60] | 648 (67,000) | 703 | 0.027 | 0.75 | 0.72 | ||

| DPR2b [60] | 670 (63,500) | 706 | 0.065 | 0.79 | 0.75 | ||

| Photofrin [60] | 628 (3000) | 630 | 0.10 | 0.61 | 0.30 | ||

| Aza-BODIPY 5a [60] | 660 (83,000) | 706 | ------- | 0.68 | 0.65 | ||

| Compound | 87 | 88 | 91 | 92 | ||

| Solvent | DMF | DMF | DMF | DMF | ||

| λabs [nm] [73] | 654 | 667 | 670 | 670 | ||

| λem [nm] [73] | 676 | 693 | 701 | 701 | ||

| Δ λ [nm] [73] | 22 | 26 | 31 | 31 | ||

| εmax [M-1 cm-1] [73] | 81,987 | 74,435 | 64,505 | 73,825 | ||

| (±) (SD) [73] | (± 7394) | (± 4023) | (± 5206) | (± 5586) | ||

| Compound |

λabs [nm] Exp |

λem [nm] Calc |

Band Gap (eV) | ε [M-1 cm-1] | Oscillator Strength |

λem [nm] |

Φf [a] | Stoke’s Shift [nm] | ||

| 93 [75] | 664 | 594 | 3.70 | 78,000 | 0.90 | 691 | 0.23 | 27 | ||

| 94 [75] | 664 | 612 | 3.64 | 53,300 | 0.79 | 697 | 0.32 | 33 | ||

| 96 [75] | 642 | 572 | 3.84 | 33,800 | 0.74 | 696 | 0.13 | 54 | ||

| 95 [75] | 667 | 593 | 3.72 | 47,300 | 0.74 | 703 | 0.23 | 36 | ||

| 100 [75] | 653 | 576 | 3.83 | 72,800 | 0.91 | 692 | < 0.01 | 39 | ||

| 97 [75] | 654 | 580 | 3.82 | 41,100 | 0.79 | 693 | < 0.01 | 39 | ||

| 99 [75] | 644 | 569 | 3.88 | 36,100 | 0.80 | 696 | < 0.01 | 52 | ||

| 98 [75] | 648 | 584 | 3.81 | 53,200 | 0.74 | 699 | < 0.01 | 51 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).