Submitted:

21 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

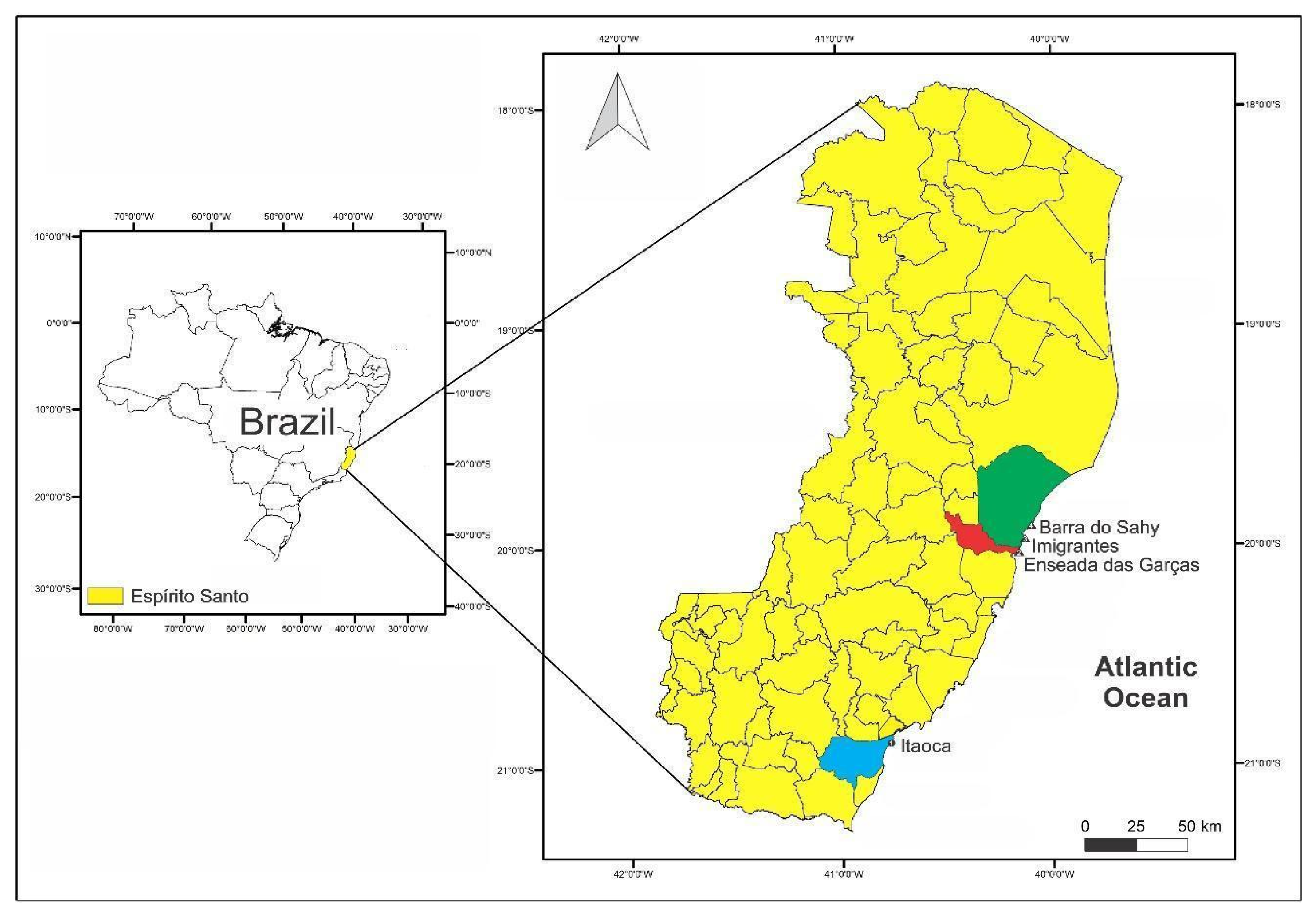

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Collection of Field Samples

2.3. Sample Preparation

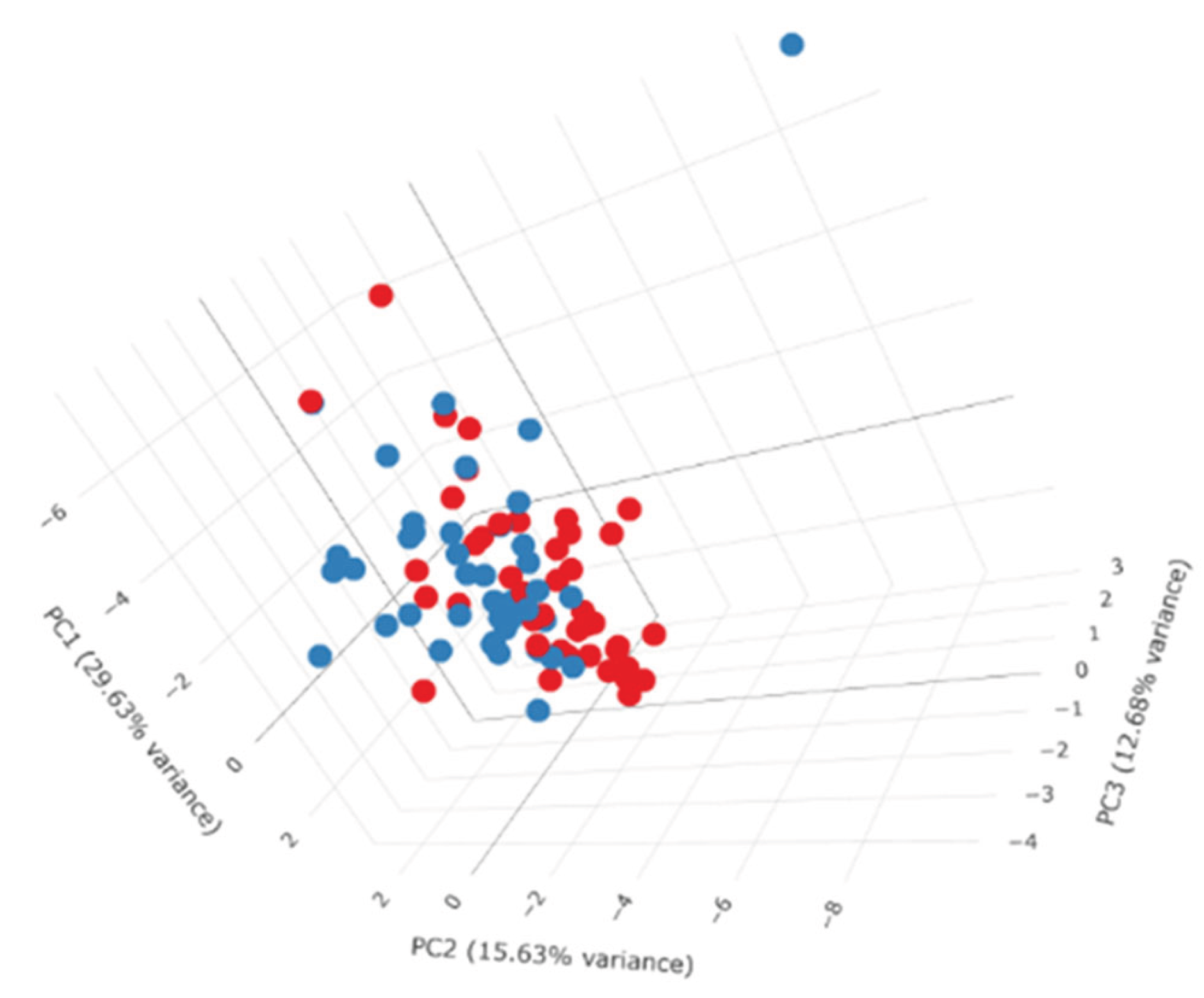

2.4. Data Analysis

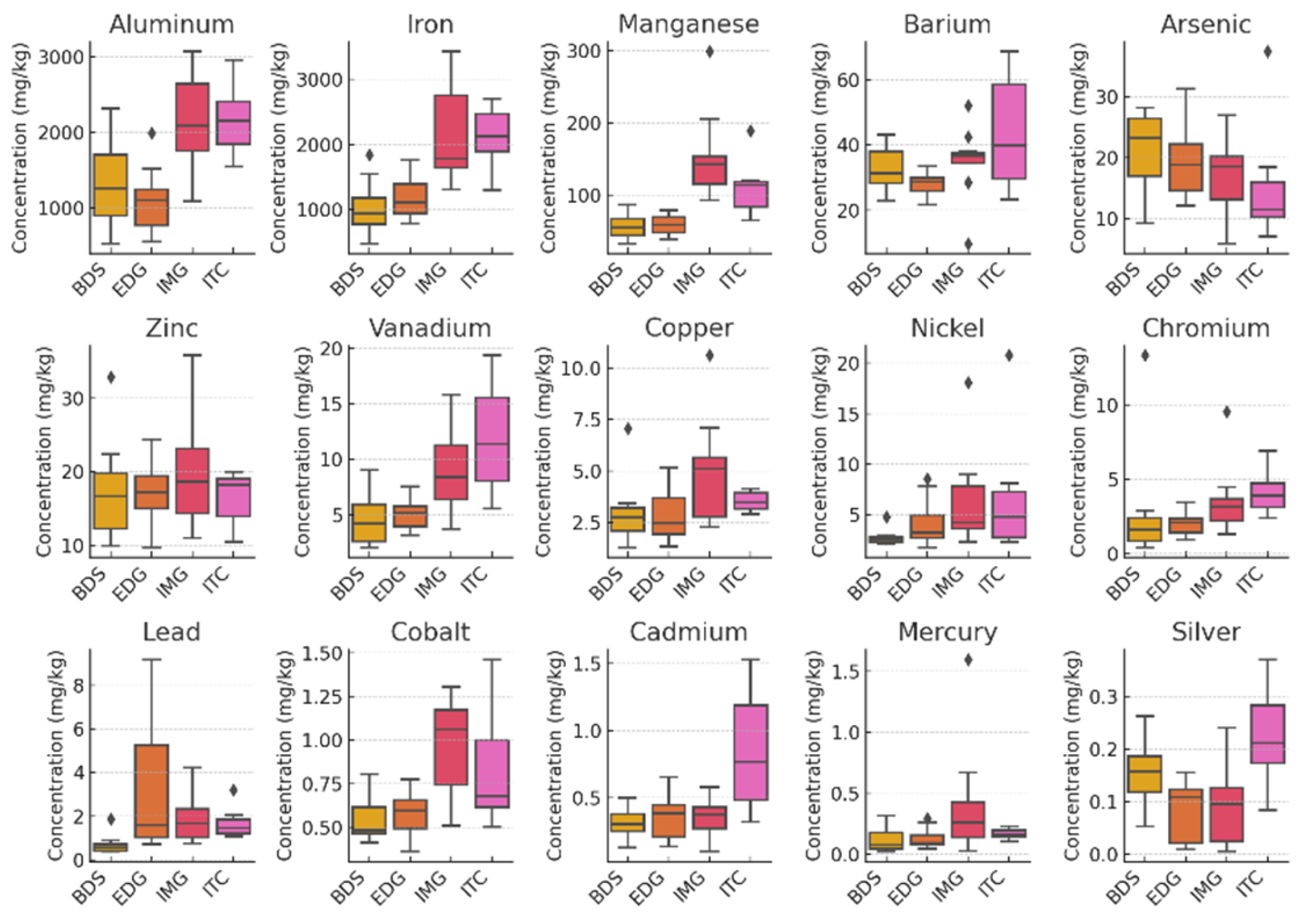

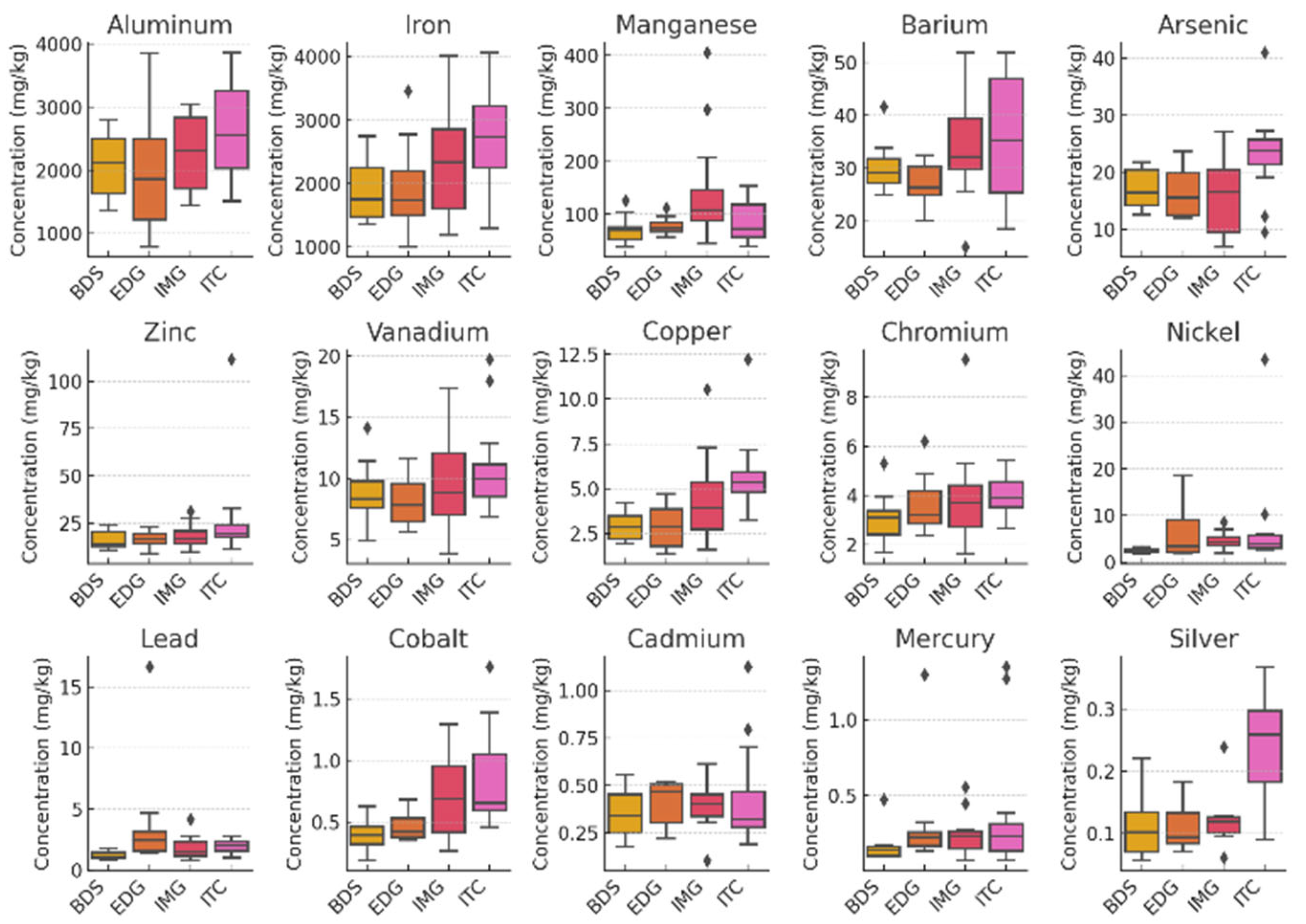

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Souza, I.C.; Duarte, I.D.; Pimentel, N.Q.; Rocha, L.D.; Morozesk, M.; Bonomo, M.M.; Azevedo, V.C.; Pereira, C.D.S.; Monferrán, M.V.; Milanez, C.R.D.; et al. Matching metal pollution with bioavailability, bioaccumulation and biomarkers response in fish (Centropomus parallelus) resident in neotropical estuaries. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 180, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, J.J.M.; Cutrim, M.V.J.; da Cruz, Q.S. Evaluation of metal contamination in surface sediments and macroalgae in mangrove and port complex ecosystems on the Brazilian equatorial margin. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaynab, M.; Al-Yahyai, R.; Ameen, A.; Sharif, Y.; Ali, L.; Fatima, M.; Khan, K.A.; Li, S. Health and environmental effects of heavy metals. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022, 34, 101653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kütter, V.T.; Martins, G.S.; Brandini, N.; Cordeiro, R.C.; Almeida, J.P.A.; Marques, E.D. Impacts of a tailings dam failure on water quality in the Doce river: The largest environmental disaster in Brazil. J. Trace Elem. Min. 2023, 5, 100084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhini, C.M.; Mahieu, L.; Sá, F.; van den Berg, C.M.G.; Salaün, P.; Neto, R.R. Coastal waters contamination by mining tailings: What triggers the stability of iron in the dissolved and soluble fractions? Limnol. Oceanogr. 2021, 66, 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado-Filho, G.M.; Salgado, L.T.; Rebelo, M.F.; Rezende, C.E.; Karez, C.S.; Pfeiffer, W.C. Heavy metals in benthic organisms from Todos os Santos Bay, Brazil. Braz. J. Biol. 2008, 68, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, C.G.; Liu, Z.Y.; Wang, X.L.; Qin, S. The seaweed holobiont: from microecology to biotechnological applications. Microb. Biotechnol. 2022, 15, 738–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavalcanti, M.I.L.G.; Fujii, M.T. Macroalgas Arribadas da Costa Brasileira: Biodiversidade e Potencial de Aproveitamento, 1st ed.; Editora CRV: Curitiba, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Harb, T.B.; Pereira, M.S.; Cavalcanti, M.I.L.G.; Fujii, M.T.; Chow, F. Antioxidant activity and related chemical composition of extracts from Brazilian beach-cast marine algae: opportunities of turning a waste into a resource. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021, 33, 3383–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, I.A.G.; Basílio, T.H.; dos Santos, I.L.F.; Fujii, M.T. Biodiversity and Reproductive Status of Beach-Cast Seaweeds from Espírito Santo, Southeastern Brazil: Sustainable Use and Conservation. Phycology. 2024, 4, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hu, C.; Barnes, B.B.; Mitchum, G.; Lapointe, B.; Montoya, J. The great Atlantic Sargassum belt. Science. 2019, 365, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tocci, B.R.C.; Vieira, L.M.; Tamanaha, M.S.; Charrid, R.J. Stranding events of drift organisms (Arribadas) in southern Brazil and the spread of invasive bryozoan in South America. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 184, 114120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resiere, D.; Valentino, R.N.; Banydeen, R.; Gueye, P.; Florentin, J.; Cabié, A.; Lebrun, T.; Mégarbane, B.; Guerrier, G.; Mehdaoui, H. Sargassum seaweed on Caribbean islands: an international public health concern. Lancet 2018, 392, 2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, G.N.; Do Nascimentos, O.S.; Pedreira, F.A.; Rios, G.I. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of arribadas algae North of Bahia State, Brazil. Acta Bot. Malacit. 2013, 38, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacramento, R.M.O.; Seidler, E.; Souza, M.; Yoshimura, C.Y. Utilização de macroalgas arribadas do litoral catarinense na adubação orgânica de olerícolas. Sci. Plena. 2013, 1, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, O.; Ramsubhag, A.; Jayaraman, J. Biostimulant Properties of Seaweed Extracts in Plants: Implications towards Sustainable Crop Production. Plants. 2021, 10, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandalka, A.; Cavalcanti, M.I.L.G.; Harb, T.B.; Fujii, M.T.; Eisner, P.; Scweiggert-Weisz, U.; Chow, F. Nutritional composition of beach-cast marine algae from the brazilian coast: added value for algal biomass considered as waste. Foods. 2022, 11, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb, T.B.; Chow, F. An overview of stranded seaweeds: Potential and opportunities for the valorization of underused waste biomass. Algal Res. 2022, 62, 102643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coração, A.C.Z.; Santos, F.S.; Duarte, E.A.P.L.F.; De-Paula, J.C.; Rocha, L.M.; Krepsky, N.; Fiaux, S.B.; Teixeira, V.L. What do we know about the utilization of the Sargassum species as biosorbents of trace metals in Brazil? J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 103941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, R.A.; Magalhães, C.A.; Taniguchi, S.; Siqueira, S.G.L.; Jacobucci, G.B.; Leite, F.P.P.; Bícego, M.C. Evaluation of macroalgae and amphipods as bioindicators of petroleum hydrocarbons input into the marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 145, 564–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Bhattacharya, T.; Singh, G.; Maity, J.P. Benthic macroalgae as biological indicators of heavy metal pollution in the marine environments: A biomonitoring approach for pollution assessment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2014, 100, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE – INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAPFIA E ESTATÍSTICA. Cities and States of Brazil. 2022. Available online: https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/ Accessed on: 22/09/2022.

- Karez, C.S.; Bahia, R.G.; Nunes, J.M.C.; Moraes, F.C.; Moura, R.L.; Salomon, P.S.; Ribeiro, C.C.M.; Silva, C.C.; Cardial, P.; Leal, G.A.; et al. Lista de espécies de macroalgas marinhas da Área de Proteção Ambiental Costa das Algas, ES. In Catálogo de Plantas das Unidades de Conservação do Brasil; Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2023; Available online: https://catalogo-ucs-brasil.jbrj.gov.br (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Ferreira, G.S.; Brito, P.O.B.; Aderaldo, F.I.C.; Carneiro, P.B.M.; Rocha, A.M.; Gondim, F.A. Arribadas algae from Pacheco beach, Ceará, Brazil. Revista Verde. 2020, 15, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, G.B.; De Souza, T.L.; Bressy, F.C.; Moura, C.W.N.; Korn, M.G.A. Levels and spatial distribution of trace elements in macroalgae species from the Todos os Santos Bay, Bahia, Brazil. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012, 64, 2238–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, E.E.; Nobre, I.G.; Silva, D.R.; Da Silva, W.M.; Sousa, S.K.; Holanda, T.B.; Lima, C.G.; De Lima, A.C.; Araújo, M.L.; Da Silva, F.L.; et al. Profile of inorganic elements of seaweed from the Brazilian Northeast coast. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 202, 116413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, N.; Ferraz, S.; Venuleo, M.; Barros, A.I.R.N.A.; Pinheiro de Carvalho, M.A.A. From a heavy metal perspective, is macroalgal biomass from Madeira Archipelago and Gran Canaria Island of eastern Atlantic safe for the development of blue bioeconomy products? J. Appl. Phycol. 2024, 36, 811–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Masri, M. S. , Mamish, S. , Budier, Y. Radionuclides and trace metals in eastern Mediterranean Sea algae. J. Environ. Rad., 2003, 67, 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Malea, P.; Kevrekidis, T. Trace element patterns in marine macroalgae. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 494–495, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.S.; Cagnin, R.C.; Da Silva, C.A.; Longhini, C.M.; Sá, F.; Lima, A.T.; Gomes, L.; Bernardino, A.F.; Neto, R.R. Iron ore tailings as a source of nutrients to the coastal zone. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 171, 112725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.T.; Bastos, F.A.; Junior, F.J.T.; Neto, R.R.; Gomes, H.I.; Barroso, G.F. Doce River Large-Scale Environmental Catastrophe: Decision and Policy-Making Outcomes. Environ. Dev. 2021, 2, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bonecker, A.C.T.; Menezes, B.S.; Dias Junior, C.; Silva, C.A.D.; Ancona, C.M.; Dias, C.D.O.; Longhini, C.M.; Costa, E.S.; Sá, F.; Lázaro, G.C.S. An integrated study of the plankton community after four years of Fundão dam disaster. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, R.L.; Alves, P.R.; Di Domenico, M.; Braga, A.A.; De Paiva, P.C.; D’Azeredo Orlando, M.T.; Sant’Ana Cavichini, A.; Longhini, C.M.; Martins, C.C.; Neto, R.R.; et al. The Fundão dam failure: Iron ore tailing impact on marine benthic macrofauna. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 156205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cagnin, R.C.; Costa, E.S.; Longhini, C.M.; Sá, F.; Neto, R.R. Rare earth elements as tracers of iron ore tailings on the Brazilian eastern continental shelf. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2024, 20, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura, F.R.; Nunes, E.A.; Paniz, F.P.; Paulelli, A.C.C.; Rodrigues, G.B.; Braga, G.U.L.; Pedreira Filho, W.R.; Barbosa Junior, F.; Cerchiaro, G.; Silva, F.F.; et al. Potential risks of the residue from Samarco’s mine dam burst (Bento Rodrigues, Brazil). Environ. Pollut. 2016, 218, 813–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sá, F.; Longhini, C.M.; Costa, E.S.; Da Silva, C.A.; Cagnin, R.C.; Gomes, L.E.D.O.; Lima, A.T.; Bernardino, A.F.; Neto, R.R. Time-sequence development of metal(loid)s following the 2015 dam failure in the Doce river estuary, Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 769, 144532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farias, S.; Smichowski, P.; Vélez, D.; Montoro, R.; Curtosi, A.; Vodopívez, C. Total and inorganic arsenic in Antarctic macroalgae. Chemosphere. 2007, 69, 1017–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeyens, W.; Mirlean, N.; Bundschuh, J.; De Winter, N.; Baisch, P.; Da Silva Júnior, F.M.R.; Gao, Y. Arsenic enrichment in sediments and beaches of Brazilian coastal waters: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 681, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassar, C.; Salgado, L.T.; Yoneshigue-Valentin, Y.; Amado-Filho, G.M. The effect of iron-ore particles on the metal content of the brown alga Padina gymnospora (Espı́rito Santo Bay, Brazil). Environ. Pollut. 2003, 123, 301–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabeau, S.; Fleurence, J. Seaweed in food products: biochemical and nutritional aspects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1993, 4, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Calvo, J.J.; Mazuelos, C.; Hermosín, B.; Sáiz-Jiménez, C. Chemical composition of Spirulina and eukaryotic algae food products marketed in Spain. J. Appl. Phycol. 1993, 5, 425–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parus, A.; Karbowska, B. Marine Algae as natural indicator of environmental cleanliness. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2020, 231, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, F.G.; Atlas geoquímico do estado do Espírito Santo. CPRM - Serviço Geológico do Brasil: Brasília, Brazil, 2018. Available online: https://rigeo.sgb.gov.br/handle/doc/21727 (accessed on 28 August 2024).

- Rubio, C.; Napoleone, G.; Luis-González, G.; Gutiérrez, A.J.; González-Weller, D.; Hardisson, A.; Revert, C. Metals in Edible Seaweed. Chemosphere. 2017, 173, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, E.F.A.; Janssen, P.J.C.M.; de Wit-Bos, L. Arsenic: bioaccessibility from seaweed and rice, dietary exposure calculations and risk assessment. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess. 2014, 31, 1993–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundhar, S.; Arisekar, U.; Shakila, R.J.; Shalini, R.; Al-Ansari, M.M.; Al-Dahmash, N.D.; Mythili, R.; Kim, W.; Sivaraman, B.; Jenishma, J.S.; et al. Potentially toxic metals in seawater, sediment and seaweeds: bioaccumulation, ecological and human health risk assessment. Environ. Geochem. Health. 2024, 46, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzuco, A.C.D.A.; Stelzer, P.S.; Bernardino, A.F. Substrate rugosity and temperature matters: patterns of benthic diversity at tropical intertidal reefs in the SW Atlantic. PeerJ. 2020, 8, e8289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, I.M.; Paiva, P.C.; Bertocci, I.; Lorini, M.L.; de Széchy, M.T.M. Distribution of a canopy-forming alga along the Western Atlantic Ocean under global warming: The importance of depth range. Mar. Environ. Res. 2023, 188, 106013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, M.M.; Silva, J.E.D.; Passavante, J.Z.D.O.; Pimentel, M.F.; Barros Neto, B.D.; Silva, V.L.D. Macroalgae as lead trapping agents in industrial effluents-a factorial design analysis. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2001, 12, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vila Nova, L.L.M.; Costa, M.M.D.A.S.; Costa, J.G.; Da Amorim, E.C.; Guedes, E.A.C. Utilização de “algas arribadas” como alternativa para adubação orgânica em cultivo de Moringa oleifera. Lam. Rev. Ouricuri. 2014, 4, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calado, S.C.S.; Silva, V.L.; Passavante, J.Z.O.; Abreu, C.A.M.; Lima Filho, E.S.; Duarte, M.M.M.B.; Diniz, E.V.G.S. Cinética e equilíbrio de biossorção de chumbo por macroalgas. Trop. Oceanogr. 2003, 31, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keiji, I.; Kanji, H. Seaweed: chemical composition and potential food uses. Food Rev. Int. 1989, 5, 101–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraghavan, K.; Teo, T.T.; Balasubramanian, R.; Joshi, U.M. Application of Sargassum biomass to remove heavy metal ions from synthetic multi-metal solutions and urban storm water runoff. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 164, 1019–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.A.; Volesky, B.; Mucci, A. A review of the biochemistry of heavy metal biosorption by brown algae. Water Res. 2003, 37, 4311–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Municipality | Beach | Characteristics of the beaches | Geographic coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aracruz (94,765 inhabitants) |

Barra do Sahy |

|

19° 52’ 28.056" S 40° 4’ 44.328" W |

| Imigrantes |

|

19°57’13.9" S 40°08’29.3" W |

|

| Fundão (21,948 inhabitants) |

Enseada das Garças |

|

20° 1’ 49.908" S 40° 9’ 31.860" W |

| Itapemirim (34,656 inhabitants) |

Itaoca |

|

20° 54’ 23.220" S 40° 46’ 49.908" W |

| Source: IBGE, 2022 | |||

| Elements | ppb | |

|---|---|---|

| LOD | LOQ | |

| Ag | 0.030 | 0.090 |

| Al | 0.91 | 2.76 |

| As | 0.048 | 0.147 |

| Ba | 0.045 | 0.136 |

| Cd | 0.002 | 0.007 |

| Co | 0.006 | 0.019 |

| Cr | 0.021 | 0.064 |

| Cu | 0.054 | 0.162 |

| Fe | 2.55 | 7.72 |

| Hg | 0.036 | 0.110 |

| Mn | 0.101 | 0.306 |

| Ni | 0.074 | 0.224 |

| Pb | 0.021 | 0.062 |

| V | 0.007 | 0.020 |

| Zn | 0.089 | 0.269 |

| Samples analyzed | Beach-Cast | Submerged | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Zonaria tournefortii | Sargassum natans | Sargassum natans (as S. vulgare) | ||||

| Sampling sites | Espírito Santo | Espírito Santo | Syrian Sea | Ceará (Dry Season) |

Ceará (Rainy Season) |

Madeira Archipelago | |

| Metal (mg kg⁻¹) | Median ± IQR | Median ± IQR | Mean ± SD1 | Mean ± SD2 | Mean ± SD2 | Mean ± SD3 | |

| Aluminum (Al) | 2255 ± 960 | 1612 ± 1080 | 2898 ± 119 | 174 ± 0.1 | 2199 ± 130 | - | |

| Iron (Fe) | 2184 ± 1208 | 1352 ± 833 | 7382 ± 202 | 99 ± 7 | 1730 ± 117 | - | |

| Manganese (Mn) | 74.9 ± 41.2 | 78.6 ± 64.1 | 129 ± 5 | 8.48 ± 0.51 | 220.8 ± 8.4 | - | |

| Barium (Ba) | 29.4 ± 7.9 | 31.4 ± 9.5 | 23 ± 1 | 1.10 ± 0.05 | 27.9 ± 0.3 | - | |

| Arsenic (As) | 19.2 ± 8.8 | 18.4 ± 10.5 | 93.2 ± 3.1 | 5.0 ± 0.3 | 172 ± 6 | - | |

| Zinc (Zn) | 17 ± 8.2 | 17.1 ± 6.4 | 23.74 ± 1.19 | < LOD | 17.6 ± 1.8 | 25.20 ± 4.97 | |

| Vanadium (V) | 8.80 ± 3.8 | 5.70 ± 4.6 | 11.07 ± 7.38 | < LOD | < LOD | - | |

| Copper (Cu) | 3.70 ± 2.5 | 3.20 ± 1.7 | 4.75 ± 0.18 | < LOD | 2.36 ± 0.17 | 1.37 ± 0.04 | |

| Chromium (Cr) | 3.50 ± 1.4 | 2.30 ± 1.9 | 23.1 ± 1.0 | 0.130 ± 0.007 | 6.77 ± 0.48 | 1.19 ± 0.3 | |

| Nickel (Ni) | 3.20 ± 2.5 | 3.00 ± 2.4 | 0.71 ± 0.1 | < LOD | < LOD | 1.37 ± 0.08 | |

| Lead (Pb) | 1.60 ± 1.1 | 1.10 ± 1.2 | 1.04 ± 0.05 | < LOD | < LOD | 0.40 ± 0.04 | |

| Cobalt (Co) | 0.50 ± 0.3 | 0.60 ± 0.3 | 3.60 ± 0.33 | 0.130 ± 0.01 | 2.16 ± 0.06 | - | |

| Cadmium (Cd) | 0.40 ± 0.2 | 0.40 ± 0.2 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 0.050 ± 0.004 | 1.41 ± 0.01 | 1.75 ± 0.07 | |

| Mercury (Hg) | 0.20 ± 0.1 | 0.10 ± 0.2 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.634 ± 0.058 | 1.479 ± 0.05 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | |

| Silver (Ag) | 0.10 ± 0.1 | 0.10 ± 0.1 | - | - | - | - | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).