Submitted:

21 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Challenge and Strategies in siRNA Delivery

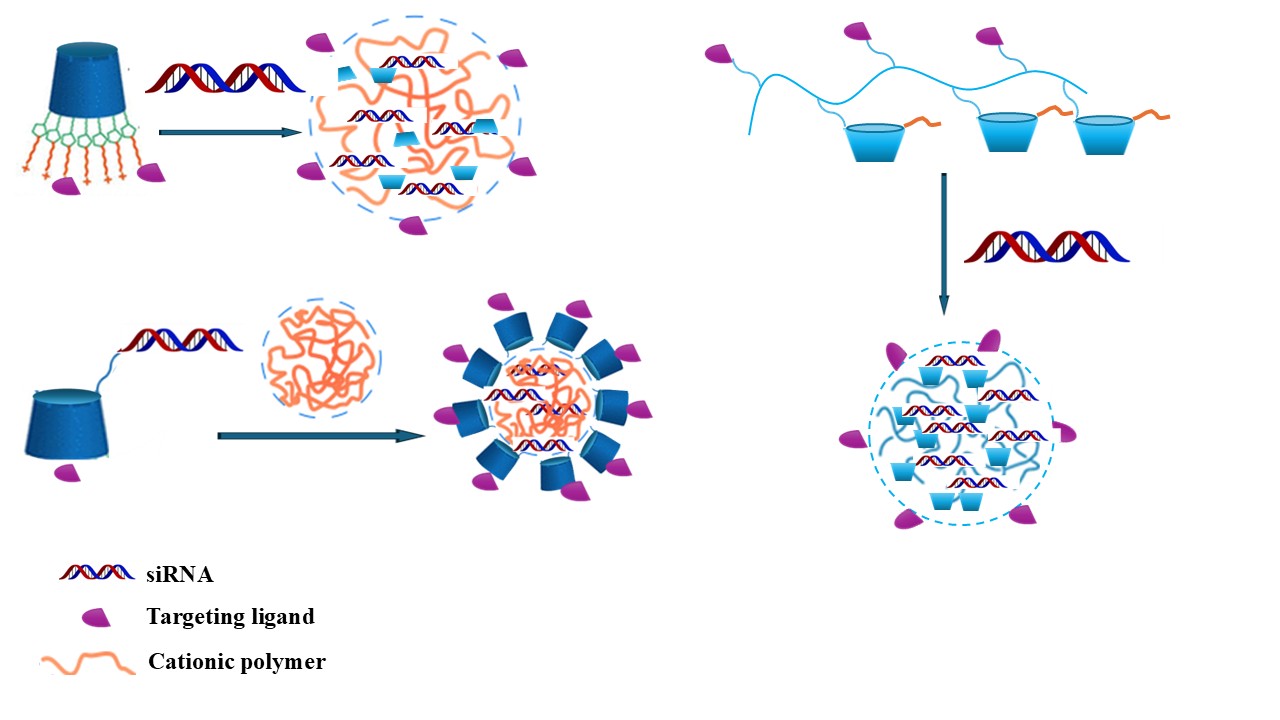

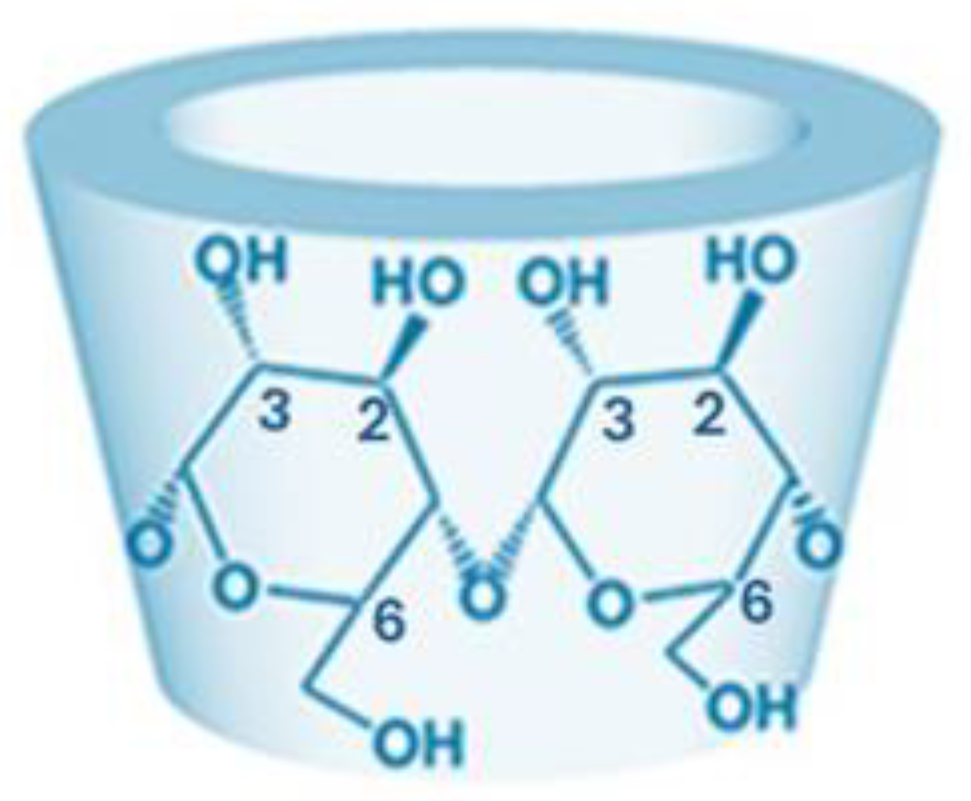

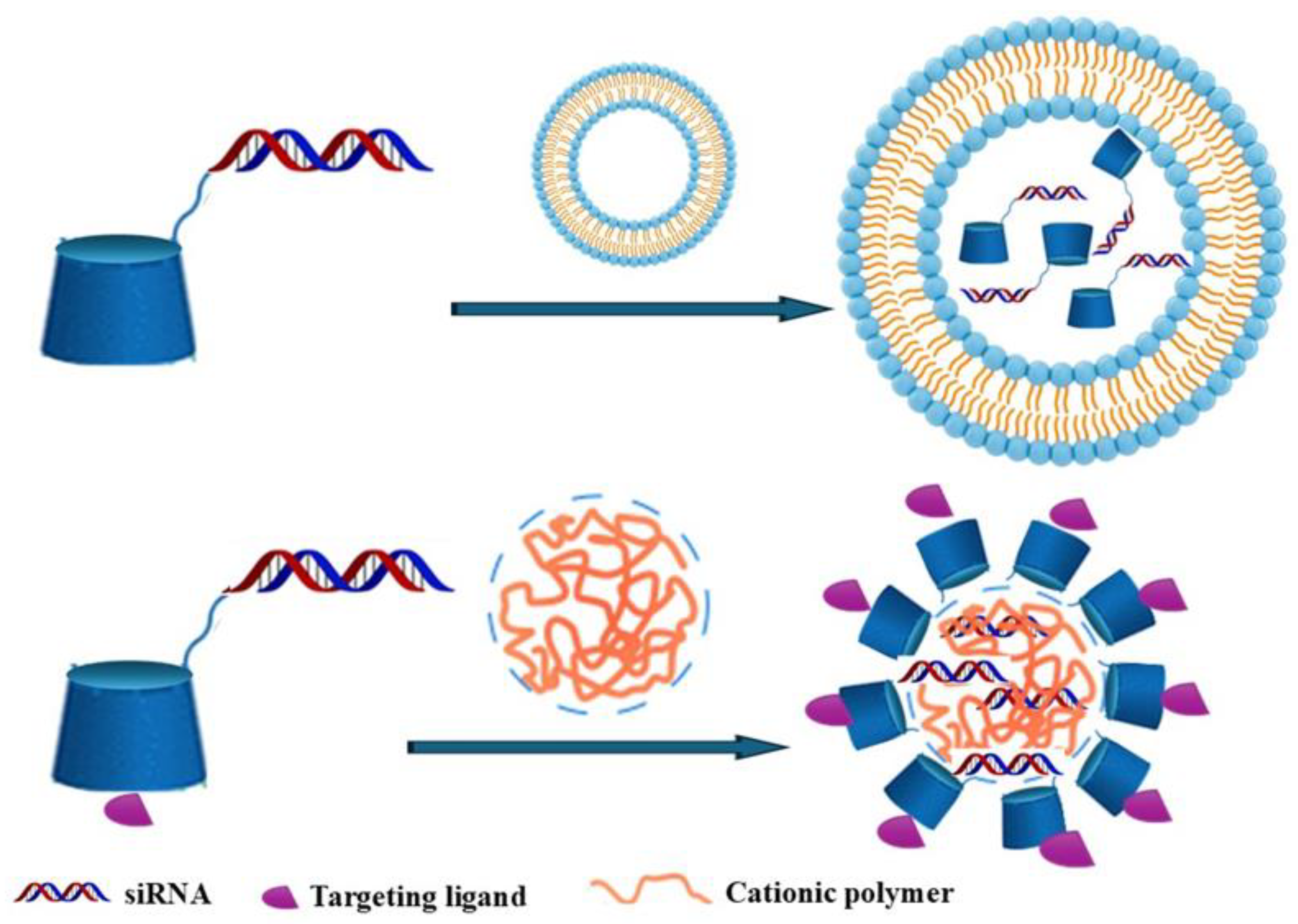

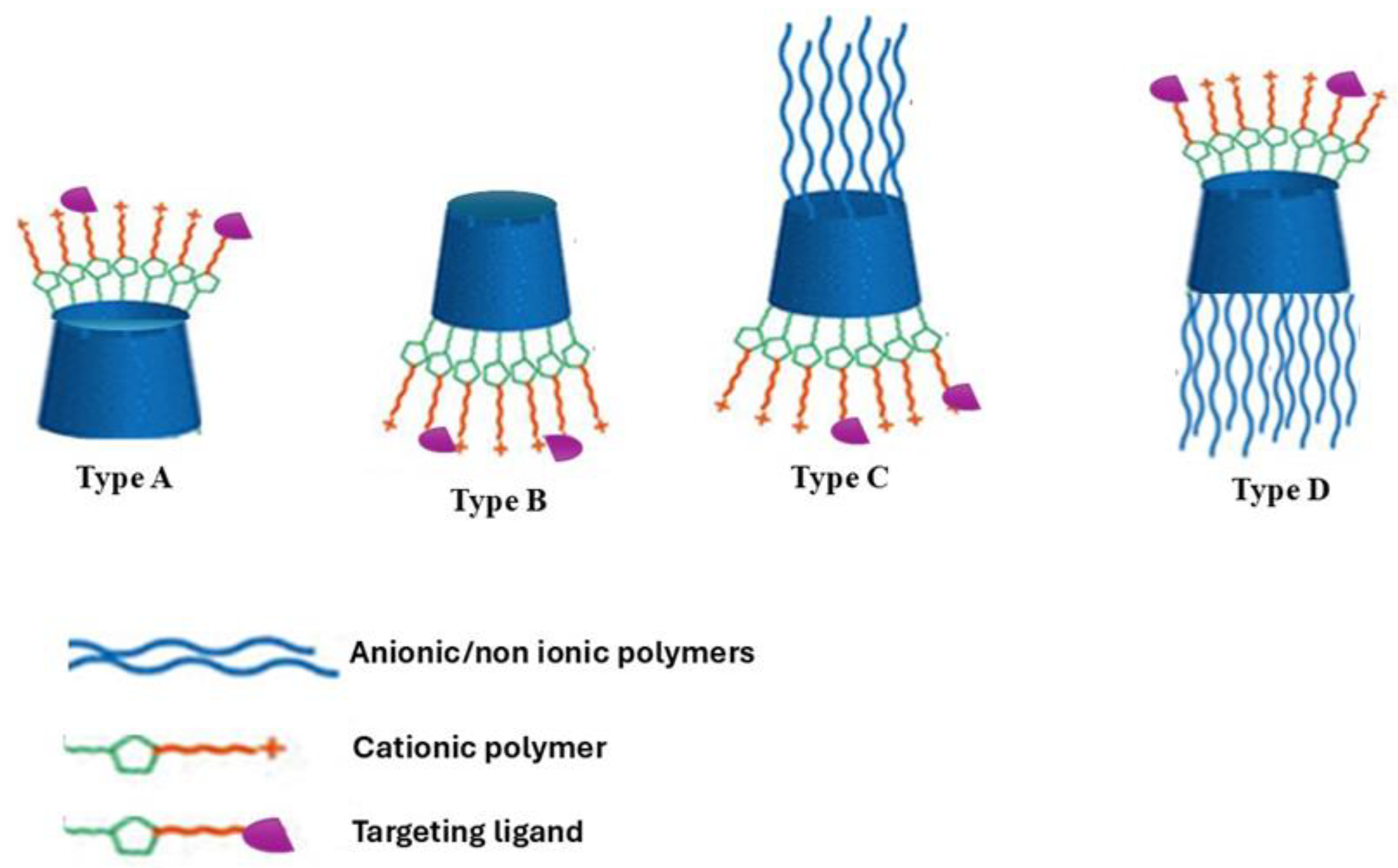

3. NVs Based on Modified CD for siRNA Delivery

3.1. Stimuli Responsive and Thermodynamics in CD-Mediated Gene Delivery

4. Computational-Experimental Design of β-self Assembling CD

5. Targeted Delivery

6. Conclusions and Future Prospectives

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| siRNA | small interfering RNA |

| CD | cyclodextrin |

| NVs | Nanovectors |

| RNAi | RNA interference |

| miRNA | microRNA |

| LNPs | Lipid Nanoparticles |

| hATTR | hereditary transthyretin amyloidos |

| BBB | Blood Brain Barrier |

| cCD | Cationic cyclodextrin |

| AML | acute myeloid leukaemia |

| TAMs | tumor-associated macrophages |

References

- Fire, A.; Xu, S.; Montgomery, M.K.; Kostas, S.A.; Driver, S.E.; Mello, C.C. Potent and Specific Genetic Interference by Double-Stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis Elegans. Nature 1998, 391, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Liao, S.; Bai, H.; Gupta, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, J.; Jiao, L.; Wu, L.; Wang, M.; Chen, X.; et al. Long Noncoding RNA and Predictive Model To Improve Diagnosis of Clinically Diagnosed Pulmonary Tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, e01973–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical Trials siRNA.

- Alabi, C.; Vegas, A.; Anderson, D. Attacking the Genome: Emerging siRNA Nanocarriers from Concept to Clinic. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2012, 12, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebenezer, O.; Oyebamiji, A.K.; Olanlokun, J.O.; Tuszynski, J.A.; Wong, G.K.-S. Recent Update on siRNA Therapeutics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiridon, I.; Anghel, N. Cyclodextrins as Multifunctional Platforms in Drug Delivery and Beyond: Structural Features, Functional Applications, and Future Trends. Molecules 2025, 30, 3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansook, P.; Ogawa, N.; Loftsson, T. Cyclodextrins: Structure, Physicochemical Properties and Pharmaceutical Applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 535, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wu, Y.-L.; Li, Z.; Loh, X.J. Cyclodextrin-Based Sustained Gene Release Systems: A Supramolecular Solution towards Clinical Applications. Mater. Chem. Front. 2019, 3, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challa, R.; Ahuja, A.; Ali, J.; Khar, R.K. Cyclodextrins in Drug Delivery: An Updated Review. AAPS PharmSciTech 2005, 6, E329–E357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, K.; Ganguly, K.; Kulkarni, A.R.; Kulkarni, V.H.; Nadagouda, M.N.; Rudzinski, W.E.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Cyclodextrin-Based siRNA Delivery Nanocarriers: A State-of-the-Art Review. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2011, 8, 1455–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousazadeh, H.; Pilehvar-Soltanahmadi, Y.; Dadashpour, M.; Zarghami, N. Cyclodextrin Based Natural Nanostructured Carbohydrate Polymers as Effective Non-Viral siRNA Delivery Systems for Cancer Gene Therapy. J. Controlled Release 2021, 330, 1046–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, G.; Han, X.; Ma, L.; Feng, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X. Cyclodextrins as Non-Viral Vectors in Cancer Theranostics: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 313, 143697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paunovska, K.; Loughrey, D.; Dahlman, J.E. Drug Delivery Systems for RNA Therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2022, 23, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazzam, M.; Zhang, M.; Hussain, A.; Yu, X.; Huang, J.; Huang, Y. The Landscape of Nanoparticle-Based siRNA Delivery and Therapeutic Development. Mol. Ther. 2024, 32, 284–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoy, S.M. Patisiran: First Global Approval. Drugs 2018, 78, 1625–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qosa, H.; De Oliveira, C.H.M.C.; Cizza, G.; Lawitz, E.J.; Colletti, N.; Wetherington, J.; Charles, E.D.; Tirucherai, G.S. Pharmacokinetics, Safety, and Tolerability of BMS-986263, a Lipid Nanoparticle Containing HSP47 siRNA, in Participants with Hepatic Impairment. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2023, 16, 1791–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falsini, S.; Ristori, S.; Ciani, L.; Di Cola, E.; Supuran, C.T.; Arcangeli, A.; In, M. Time Resolved SAXS to Study the Complexation of siRNA with Cationic Micelles of Divalent Surfactants. Soft Matter 2013, 10, 2226–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Falsini, S.; Di Cola, E.; In, M.; Giordani, M.; Borocci, S.; Ristori, S. Complexation of Short Ds RNA/DNA Oligonucleotides with Gemini Micelles: A Time Resolved SAXS and Computational Study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 3046–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, K.A.; Malhotra, M.; Gooding, M.; Sallas, F.; Evans, J.C.; Darcy, R.; O’Driscoll, C.M. A Novel, Anisamide-Targeted Cyclodextrin Nanoformulation for siRNA Delivery to Prostate Cancer Cells Expressing the Sigma-1 Receptor. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 499, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haley, R.M.; Gottardi, R.; Langer, R.; Mitchell, M.J. Cyclodextrins in Drug Delivery: Applications in Gene and Combination Therapy. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2020, 10, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazli, A.; Malanga, M.; Sohajda, T.; Béni, S. Cationic Cyclodextrin-Based Carriers for Drug and Nucleic Acid Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, M.; Gooding, M.; Evans, J.C.; O’Driscoll, D.; Darcy, R.; O’Driscoll, C.M. Cyclodextrin-siRNA Conjugates as Versatile Gene Silencing Agents. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 114, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, M.C.P.; Cronin, M.F.; Cryan, J.F.; O’Driscoll, C.M. Modified Cyclodextrin-Based Nanoparticles Mediated Delivery of siRNA for Huntingtin Gene Silencing across an in Vitro BBB Model. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2021, 169, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, A.; DeFrees, K.; Schuldt, R.A.; Hyun, S.-H.; Wright, K.J.; Yerneni, C.K.; VerHeul, R.; Thompson, D.H. Cationic α-Cyclodextrin:Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Polyrotaxanes for siRNA Delivery. Mol. Pharm. 2013, 10, 1299–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seripracharat, C.; Sinthuvanich, C.; Karpkird, T. Cationic Cyclodextrin-Adamantane Poly(Vinyl Alcohol)-Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Assembly for siRNA Delivery. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 68, 103052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kont, A.; Mendonça, M.C.P.; Cronin, M.F.; Cahill, M.R.; O’Driscoll, C.M. Co-Formulation of Amphiphilic Cationic and Anionic Cyclodextrins Forming Nanoparticles for siRNA Delivery in the Treatment of Acute Myeloid Leukaemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Cronin, M.F.; Mendonça, M.C.P.; Guo, J.; O’Driscoll, C.M. Sialic Acid-Targeted Cyclodextrin-Based Nanoparticles Deliver CSF-1R siRNA and Reprogram Tumour-Associated Macrophages for Immunotherapy of Prostate Cancer. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 185, 106427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, D.; Zhang, H.; Ou, T.; Xiao, L.; Chen, W. Construction of Aptamer-siRNA Chimera and Glutamine Modified Carboxymethyl-β-Cyclodextrin Nanoparticles for the Combination Therapy against Lung Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 174, 116506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuckerman, J.E.; Gritli, I.; Tolcher, A.; Heidel, J.D.; Lim, D.; Morgan, R.; Chmielowski, B.; Ribas, A.; Davis, M.E.; Yen, Y. Correlating Animal and Human Phase Ia/Ib Clinical Data with CALAA-01, a Targeted, Polymer-Based Nanoparticle Containing siRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2014, 111, 11449–11454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, A.M.; Ang, C.; Dimaio, C.J.; Javle, M.M.; Gutierrez, M.; Yarom, N.; Stemmer, S.M.; Golan, T.; Geva, R.; Semenisty, V.; et al. A Phase II Study of siG12D-LODER in Combination with Chemotherapy in Patients with Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer (PROTACT). J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, TPS4672–TPS4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. Cyclodextrin-Based Multistimuli-Responsive Supramolecular Assemblies and Their Biological Functions. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1806158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, R.P.; Hidalgo, T.; Cazade, P.-A.; Darcy, R.; Cronin, M.F.; Dorin, I.; O’Driscoll, C.M.; Thompson, D. Self-Assembled Cationic β-Cyclodextrin Nanostructures for siRNA Delivery. Mol. Pharm. 2019, 16, 1358–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo Cruz, B.; Flores Colón, M.; Rabelo Fernandez, R.J.; Vivas-Mejia, P.E.; Barletta, G.L. A Fresh Look at the Potential of Cyclodextrins for Improving the Delivery of siRNA Encapsulated in Liposome Nanocarriers. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 3731–3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H.; Shih, P.-Y.; Lin, C.-H.; Chen, Y.-J.; Wu, W.-C.; Wang, C.-C. Tetraethylenepentamine-Coated β Cyclodextrin Nanoparticles for Dual DNA and siRNA Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatiatulin, A.K.; Grishin, I.A.; Buzyurov, A.V.; Mukhametzyanov, T.A.; Ziganshin, M.A.; Gorbatchuk, V.V. Determination of Melting Parameters of Cyclodextrins Using Fast Scanning Calorimetry. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, F.; Li, Y.; Yu, W.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cao, H. Recent Progress of Small Interfering RNA Delivery on the Market and Clinical Stage. Mol. Pharm. 2024, 21, 2081–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Cao, D.; Gu, W.; Cui, L.; Qiu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Li, D.; Guo, X. Delivery of miR-34a-5p by Folic Acid-Modified β-Cyclodextrin-Grafted Polyethylenimine Copolymer Nanocarriers to Resist KSHV. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 10826–10836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Year | Title | References | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chaturvedi, K. | 2011 | Cyclodextrin-Based siRNA Delivery Nanocarriers: A State-of-the-Art Review. | 10 | ||||

| Xu, C. | 2019 | Cyclodextrin-Based Sustained Gene Release Systems: A Supramolecular Solution towards Clinical Applications. | 8 | ||||

| Haley, R.M. | 2020 | Cyclodextrins in Drug Delivery: Applications in Gene and Combination Therapy. | 20 | ||||

| Mousazadeh, H. | 2021 | Cyclodextrin-Based Natural Nanostructured Carbohydrate Polymers as Effective Non-Viral siRNA Delivery Systems for Cancer Gene Therapy. | 11 | ||||

| Castillo Cruz, B. | 2022 | A Fresh Look at the Potential of Cyclodextrins for Improving the Delivery of siRNA Encapsulated in Liposome Nanocarriers | 33 | ||||

| Nazli, A. | 2025 | Cationic Cyclodextrin-Based Carriers for Drug and Nucleic Acid Delivery | [21] | ||||

| NVs Composition | Size (nm) | siRNA | Co-delivery | In vivo/in vitro studies | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEPA-βCD polyplexes | 332-912 | anti-GFP | Plasmid DNA | In vitro | 34 |

| βCD derivatives / βCD-Ad-PEG/ anisamide target ligand /amantadine inclusion |

<300 |

targeting PLK1 |

/ |

In vitro |

19 |

| Surface modified CDs- functionalized with RVG peptide | <200 | targeting HTT mRNA | / | In Vitro | 23 |

| Modified cationic β-cyclodextrins-Ad-PVA-PEG | <300 | anti-GFP | / | In vitro |

25 |

| Modified amphiphilic cationic CD-siRNA /coformulated with anionic CD | <200 | Anti-KAT2a |

/ |

In vitro |

26 |

| Modified CD NPs-sialic acid target ligand | <250 | CSF-1R | / | In vitro | 27 |

| AS1411 aptamer–PD-L1-siRNA combined with Gln/β-CD-DOX | 250-500 | PD-L1 siRNA | Doxorubicin | In vivo | 28 |

| CD-Polymer-PEG/Tf target ligand | <200 | RRM2 | / | Clinical Trial | 29 |

| Modified cationic β-CD | <300 | PLK1 | / | In vitro | 32 |

| Covalent conjugates β-CD-siRNA | <200 | PLK1/ anti GFP | / | In vitro | 22 |

| FA-β-CD-PEI | <250 | miR-34a-5p | / | In vitro | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).